Abstract

Objectives

To compare the loss of working time due to sick leave by treatment strategy for localised prostate cancer.

Design

Nationwide cohort study.

Setting

Sweden.

Participants

A total of 15 902 working-aged men with localised low or intermediate-risk prostate cancer diagnosed during 2007–2016 from the Prostate Cancer Data Base Sweden, together with 63 464 prostate cancer-free men. Men were followed until 2016.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Using multistate Markov models, we calculated the proportion of men on work, sick leave, disability pension and death, together with the amount of time spent in each state. All-cause and cause-specific estimates were calculated.

Results

During the first 5 years after diagnosis, men with active surveillance as their primary treatment strategy spent a mean of 17 days (95% CI 15 to 19) on prostate cancer-specific sick leave, as compared with 46 days (95% CI 44 to 48) after radical prostatectomy and 44 days (95% CI 38 to 50) after radiotherapy. The pattern was similar after adjustment for cancer and sociodemographic characteristics. There were no differences between the treatment strategies in terms of days spent on sick leave due to depression, anxiety or stress. Five years after diagnosis, over 90% of men in all treatment strategies were free from sick leave, disability pension receipt and death from any cause.

Conclusions

Men on active surveillance experienced less impact on working life compared with men who received radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy. From a long-term perspective, there were no major differences between treatment strategies. Our findings can inform men diagnosed with localised prostate cancer on how different treatment strategies may affect their working lives.

Keywords: prostatectomy, prostatic neoplasms, sick leave, watchful waiting, radiotherapy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Population-based cohort study including 98% of all working-aged men diagnosed with prostate cancer in Sweden.

All sick leave periods compensated by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency were included.

Treatment strategies were not randomly assigned.

Introduction

The majority of men diagnosed with prostate cancer have localised low or intermediate-risk disease.1 2 Decisions on their management are multifaceted and difficult since the choice of treatment involves a balance between the potential benefits and potential harms over a long period of time. Radical therapy (radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy) is one treatment option; however, it may result in side effects such as erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence and bowel problems.3 In men with low-risk characteristics, current guidelines recommend active surveillance, a management strategy with few side effects and little or no survival disadvantage.4 However, living with an untreated malignancy can be a psychological burden. Approximately one-third of men who start active surveillance convert to radical therapy within 5 years after diagnosis, of which 20% have no sign of progression.5 6

A period of sick leave is common after treatment for prostate cancer. Previous studies have demonstrated that radical prostatectomy generally requires up to 7 weeks of postoperative sick leave.7–9 Radical prostatectomy can also have a long-term negative impact on employment and work, with fatigue, additional cancer treatment and bother from urinary leakage reported as independent predictors.10 Men undergoing radiotherapy may also require sick leave during the course of treatment: a previous study found that the proportion of men on sick leave was 50% during both the first and last 5 weeks of treatment.11 To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the patterns of sick leave in men on active surveillance, and few studies to date have examined sick leave beyond the first year of diagnosis.

To examine how the choice of treatment influences working life, we calculated the treatment-specific loss of working time due to sick leave in men with localised prostate cancer in a nationwide setting. We included a comparison with men who were prostate cancer free. Both all-cause and prostate cancer-specific sick leave were examined, as well as sick leave due to depression, anxiety and stress. We also quantified the impact of secondary treatments (non-adjuvant radical therapy or androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)) on sick leave, hypothesising that men with secondary treatments account for a significant proportion of reported sick leave during later parts of the follow-up.

Materials and methods

This nationwide, population-based cohort study includes men in the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden (NPCR), which includes 98% of all men diagnosed with prostate cancer in Sweden.12 In the Prostate Cancer Data Base Sweden (PCBaSe), data on cancer characteristics in the NPCR have been linked to other Swedish health and population registers.13 14 In addition to the prostate cancer cases, PCBaSe also includes five prostate cancer-free men per case matched on birth year and place of residence.

Information was extracted from PCBaSe on all men aged <65 years at diagnosis, with low-risk (T1–2, Gleason Grade Group (GGG) 1 and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) <10 ng/mL) or intermediate-risk (T1–2, and GGG 2–3 and/or PSA 10 to <20 ng/mL) prostate cancer diagnosed between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2016 and with active surveillance, surgery or radiotherapy as the primary treatment strategy (n=19 342), together with matched prostate cancer-free men. Exclusion criteria were previous receipt of disability pension, sick leave 1 month prior to diagnosis and not in paid work in the year before diagnosis, resulting in a final study population of 15 902 men with low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer and 63 464 prostate cancer-free men (corresponding to an average of four controls per case).

Information on the primary treatment strategy was extracted from the NPCR, which records treatment initiated within the first 6 months of diagnosis. We also obtained information on subsequent radical therapy using data from the National Patient Register and the Retrospective Collection of Data on Radiotherapy (RETRORAD), as previously described.13 Use of ADT due to disease progression was also recorded, identified by a filled prescription of an antiandrogen or a GnRH agonist in the National Prescribed Drug Register or a surgical orchiectomy in the National Patient Register (disregarding receipt of neoadjuvant or adjuvant ADT).

The primary outcome was part-time or full-time sick leave as registered in the national database kept by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, which had been linked to the NPCR. The Swedish Social Insurance Agency grants sickness benefits to individuals with an income from work in Sweden when those individuals have a reduced work capacity due to disease or injury. Sickness benefits are granted up to age 65 years, although older individuals can claim a restricted number of days. The Social Insurance Agency also grants disability pension to individuals aged 30–64 years in case of permanently reduced work capacity. Since the employer usually pays the first 2–14 days of a sick leave period, sick leave periods shorter than 15 days were not included in the present analysis. Both all-cause and prostate cancer-specific (International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision code C61) sick leave and disability pension receipt were studied, as well as sick leave due to depression (F32–F34, F38–F39), anxiety (F40–F42, F45, F48) and stress-related conditions (F43). All diagnoses were primary diagnoses obtained from the sick leave certificate issued by the physician. Cause-specific death obtained from the Swedish Cause of Death Register was also included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

All men were followed from the date of diagnosis until age 65, death, emigration or end of follow-up (31 December 2016), whichever event came first. In order to take both repeated sick leave periods and competing events (ie, receipt of disability pension and death) into account, we extended the standard survival approach and created a reversible multistate Markov model with the following states: work, sick leave, disability pension receipt and death (similar to the model of Gran et al).15 All men started in the working state and transitions (ie, change of state) were possible from work into all of the other states, from sick leave back to work, disability pension receipt, or death, and from disability pension receipt to death. (See online supplementary figure 1 and online supplementary table 1 for an illustration of the multistate model.) Time since diagnosis was the underlying time scale. In cause-specific analyses, one state was included for each cause and outcome. (See online supplementary figure 2 and online supplementary table 2 for an illustration of the cause-specific multistate model.) Transitions between different diagnoses within a sick leave period were not possible to take into account because only the first diagnosis was recorded. To study the impact of secondary treatment, we extended the multistate model to include separate, time-dependent sick leave states for continued initial treatment strategy or conversion to radical or secondary treatment.

bmjopen-2019-032914supp001.pdf (204.4KB, pdf)

Stratified by initial treatment strategy, transition probabilities and 95% CIs were calculated using the non-parametric Aalen-Johansen estimator.16 Length of stay in each state during the first 5 years (1825 calendar days) of diagnosis was calculated by numerical integration, using the bootstrap to obtain 95% CI. To take covariates into account, we also fitted flexible parametric regression models to each transition in the cause-specific multistate model and predicted differences in length of stay on sick leave for specified covariate patterns.17 (See online supplementary table 3 for full model specification.) The following covariates were adjusted for in the full model: age at diagnosis (<55, 55–59, 60–64), calendar period of diagnosis (2007–2009, 2010–2012, 2013–2016), region of residence (six geographical areas), education (low (0–9 years), middle (10–12 years), high (>12 years)), income (based on the income distribution of prostate cancer-free men (1%–20%, 21%–40%, 41%–60%, 61%–80%, 81%–100%), prior sick leave (no, yes), T stage (T1, T2), PSA (<4, 4–9, 10–19 ng/mL) and GGG (1, 2, 3). Covariates were selected based on previous literature7 8 10 18 and availability of data. For these reversible Markov models, the marginal transition probabilities from study entry are consistently estimated for both Markov and non-Markov data.19–21 Length of stay is a function of the transition probabilities from study entry and is also consistently estimated.

All analyses were performed using R (V.3.4.2) and STATA software (V.15.0/IC; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the design or planning of this study.

Results

Of a total of 15 902 men diagnosed with low or intermediate-risk prostate cancer, 5361 (34%) were initially managed with active surveillance, 8938 (56%) underwent primary radical prostatectomy and 1603 (10%) received primary radiotherapy. Baseline characteristics varied by treatment strategy, with fewer adverse cancer characteristics (in terms of clinical T stage, serum PSA and GGG) among the men managed with active surveillance (table 1). Eighty-five per cent of men managed with active surveillance were in the low-risk category, compared with 42%–43% of men in the two other treatment strategies. Men who received radiotherapy tended to have more adverse cancer characteristics, have less formal education and were more likely to have had prior sick leave.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of men of working age diagnosed with localised low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer stratified by initial treatment strategy, and matched prostate cancer-free men in PCBaSe, 2007–2016

| Active surveillance (%), n=5361 |

Radical prostatectomy (%), n=8938 | Radiotherapy (%), n=1603 |

PCa-free men (%), n=63 464 |

|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 60 (57–63) | 60 (56–62) | 61 (58–63) | 60 (56–62) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||

| 2007–2009 | 1033 (19) | 3008 (34) | 611 (38) | 18 203 (29) |

| 2010–2012 | 1481 (28) | 2748 (31) | 503 (31) | 18 595 (29) |

| 2013–2016 | 2847 (53) | 3182 (36) | 489 (31) | 26 666 (42) |

| Education | ||||

| Low (0–9 years) | 899 (17) | 1633 (18) | 344 (21) | 13 228 (21) |

| Middle (10–12 years) | 2416 (45) | 3844 (43) | 751 (47) | 28 206 (44) |

| High (>12 years) | 2037 (38) | 3448 (39) | 507 (32) | 21 825 (34) |

| Missing | 9 (0) | 13 (0) | 1 (0) | 205 (0) |

| Income* | ||||

| 1%–20% | 759 (14) | 1292 (14) | 312 (19) | 12 701 (20) |

| 21%–40% | 914 (17) | 1584 (18) | 341 (21) | 12 693 (20) |

| 41%–60% | 1112 (21) | 1751 (20) | 374 (23) | 12 697 (20) |

| 61%–80% | 1231 (23) | 1980 (22) | 309 (19) | 12 695 (20) |

| 81%–100% | 1345 (25) | 2331 (26) | 267 (17) | 12 678 (20) |

| Prior sick leave | ||||

| No | 4937 (92) | 8218 (92) | 1425 (89) | 58 155 (92) |

| Yes | 424 (8) | 720 (8) | 178 (11) | 5309 (8) |

| Risk category | ||||

| Low risk | 4569 (85) | 3839 (43) | 678 (42) | |

| Intermediate risk | 792 (15) | 5099 (57) | 925 (58) | |

| Clinical T stage | ||||

| T1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| T1a | 173 (3) | 30 (0) | 3 (0) | |

| T1b | 38 (1) | 29 (0) | 7 (0) | |

| T1c | 4598 (86) | 6321 (71) | 1005 (63) | |

| T2 | 552 (10) | 2558 (29) | 587 (37) | |

| Serum PSA (ng/mL) | ||||

| PSA<4 | 1405 (26) | 1739 (19) | 191 (12) | |

| 4≤PSA<10 | 3507 (65) | 5744 (64) | 1065 (66) | |

| 10≤PSA<20 | 443 (8) | 1443 (16) | 344 (21) | |

| Missing | 6 (0) | 12 (0) | 3 (0) | |

| Gleason Grade Group (biopsy) | ||||

| GGG 1 | 4956 (92) | 4504 (50) | 816 (51) | |

| GGG 2 | 344 (6) | 3460 (39) | 568 (35) | |

| GGG 3 | 49 (1) | 970 (11) | 219 (14) | |

| Missing | 12 (0) | 4 (0) | 0 (0) | |

*Based on the income distribution of prostate cancer-free men.

GGG, Gleason Grade Group; PCa, prostate cancer; PCBaSe, Prostate Cancer Data Base Sweden; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

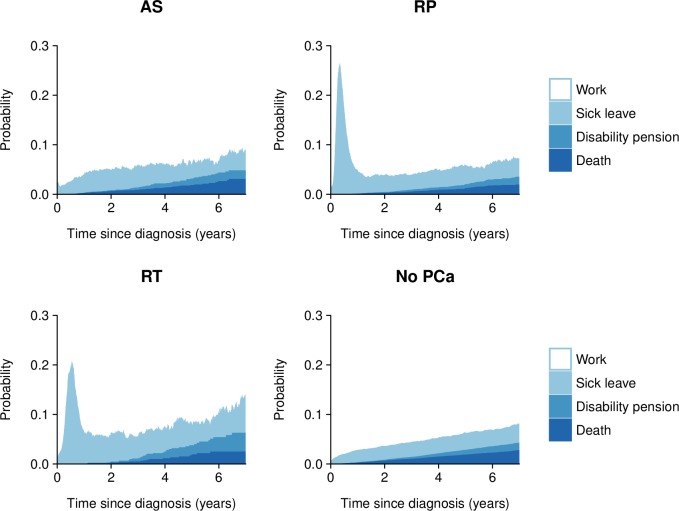

Probabilities of work, sick leave, disability pension receipt and death according to initial treatment strategy and time since diagnosis are presented in figure 1. (See online supplementary tables 1 and 2 and online supplementary table 4 for tabular presentations of number of events, probabilities and median follow-up time.) In men treated with radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy, the proportion of men on sick leave was markedly increased in the first year of diagnosis. Compared with prostate cancer-free men, all treatment strategies had higher proportions of men on sick leave at almost all of the time points examined. Five years after diagnosis, the percentage of men free from sick leave, disability pension receipt and death was 94% in men initially on active surveillance, 94% in men treated with radical prostatectomy and 92% in men who received radiotherapy, as compared with 94% in prostate cancer-free men. Differences between treatment strategies were mainly due to causes other than prostate cancer.

Figure 1.

Probabilities of work, sick leave, disability pension receipt and death by initial treatment strategy and time since diagnosis in men with localised low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer and matched prostate cancer-free men. AS, active surveillance; PCa, prostate cancer; RP, radical prostatectomy; RT, radiotherapy.

During the first 5 years after diagnosis, men on active surveillance spent a mean of 17 days (95% CI 15 to 19) on prostate cancer-specific sick leave, compared with 46 days (95% CI 44 to 48) after radical prostatectomy and 44 days (95% CI 38 to 50) after radiotherapy (table 2). The number of workdays lost due to prostate cancer-specific disability pension receipt or prostate cancer-specific death was low for all treatment strategies. These patterns were similar after stratification by risk category (online supplementary table 5).

Table 2.

Mean length of stay in work, sick leave, disability pension and death within the first 5 years after diagnosis in men with localised low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer and matched prostate cancer-free men

| State | Active surveillance | Radical prostatectomy | Radiotherapy | PCa-free men | |

| Length of stay*, days (95% CI) | Length of stay*, days (95% CI) | Length of stay*, days (95% CI) | Length of stay*, days (95% CI) | ||

| Work | 1734 (1726 to 1743) | 1717 (1711 to 1722) | 1686 (1669 to 1704) | 1754 (1751 to 1756) | |

| Sick leave | All cause | 69 (63 to 75) | 95 (91 to 100) | 117 (103 to 131) | 50 (48 to 52) |

| Prostate cancer | 17 (15 to 19) | 46 (44 to 48) | 44 (38 to 50) | 0 (0 to 0) | |

| Depression, anxiety, stress | 9 (7 to 12) | 10 (8 to 12) | 12 (7 to 17) | 8 (7 to 8) | |

| Other | 43 (38 to 48) | 40 (36 to 43) | 61 (51 to 71) | 42 (41 to 44) | |

| Disability pension | All cause | 8 (5 to 11) | 5 (3 to 7) | 12 (6 to 18) | 6 (6 to 7) |

| Prostate cancer | 0 (0 to 1) | 1 (0 to 2) | 1 (0 to 2) | 0 (0 to 0) | |

| Other | 8 (4 to 11) | 4 (3 to 6) | 11 (5 to 17) | 6 (6 to 7) | |

| Death | All cause | 15 (11 to 19) | 9 (7 to 12) | 11 (5 to 17) | 16 (15 to 18) |

| Prostate cancer | 0 (0 to 1) | 1 (0 to 2) | 1 (0 to 3) | 0 (0 to 0) | |

| Other | 15 (11 to 19) | 8 (6 to 10) | 10 (4 to 15) | 16 (15 to 18) | |

*Number of days may not add up because of rounding.

PCa, prostate cancer.

After adjustment for both cancer and sociodemographic characteristics, men treated with radical prostatectomy spent on average 24 (95% CI 21 to 28) additional days on prostate cancer-specific sick leave compared with men on active surveillance with otherwise similar characteristics (table 3). Correspondingly, men treated with radiotherapy spent 21 (95% CI 16 to 26) additional days on prostate cancer-specific sick leave compared with men on active surveillance. There were no differences between the treatment strategies in terms of days spent on sick leave due to depression, anxiety or stress, but receipt of radiotherapy was associated with additional days on sick leave due to other reasons.

Table 3.

Mean additional days on sick leave within the first 5 years after diagnosis after adjustment for cancer and sociodemographic characteristics

| State | Active surveillance | Radical prostatectomy | Radiotherapy | |

| Additional days* (95% CI) | Additional days* (95% CI) | Additional days* (95% CI) | ||

| Sick leave | Prostate cancer | Ref | 24 (21 to 28) | 21 (16 to 26) |

| Depression, anxiety, stress | Ref | 0 (−2 to 2) | 2 (−2 to 5) | |

| Other | Ref | −4 (−10 to 2) | 11 (3 to 20) | |

*Estimates have been predicted holding all of the other variables constant, using the following covariate pattern: ages 55–59 years at diagnosis, period of diagnosis 2010–2012, middle education, income 41%–60%, no prior sick leave, Stockholm-Gotland region, T stage 1, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) 4–9 ng/mL and Gleason Grade Group 1.

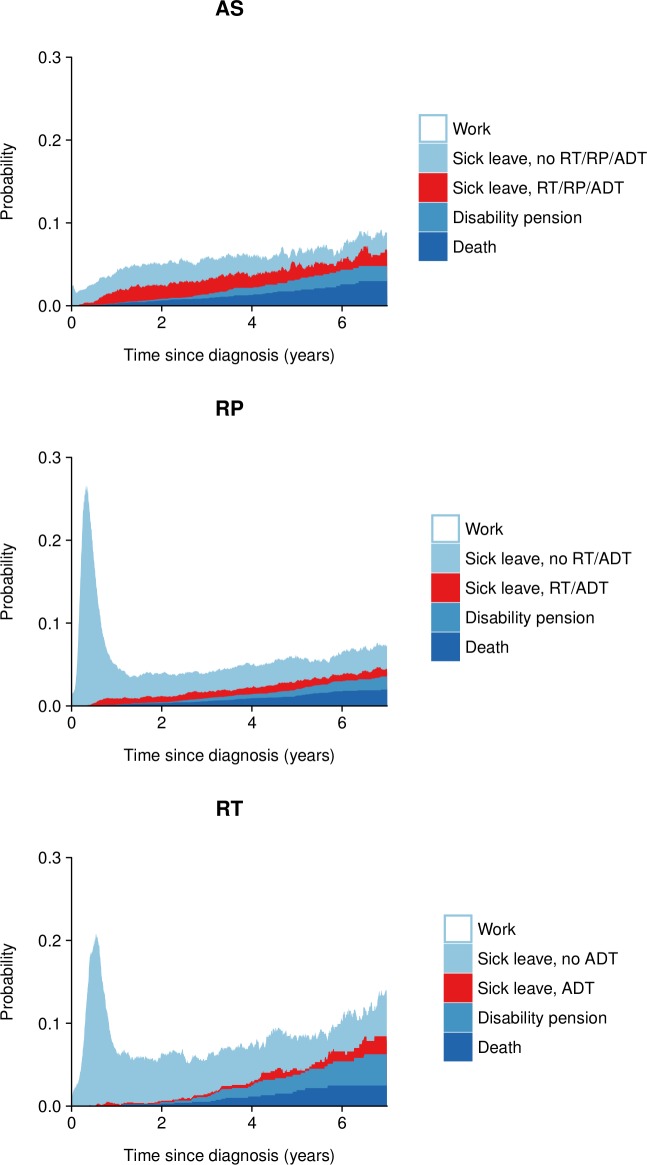

We further calculated the number of sick leave days associated with subsequent radical therapy and receipt of secondary treatment indicating disease progression (figure 2 and table 4). Although only 32% of men initially on active surveillance converted to radical therapy, these men accounted for virtually all prostate cancer-specific sick leave (15 out of 17 days). In contrast, men with disease progression after radical prostatectomy (14% of all men) only accounted for a small amount of prostate cancer-specific sick leave (7 out of 46 days) within the first 5 years after diagnosis. However, this changed with increasing follow-up time: from year 5 onwards, men with disease progression accounted for nearly all prostate cancer-specific sick leave (online supplementary table 6). A similar pattern was observed in men treated with radiotherapy.

Figure 2.

Proportion of sick leave spent by men remaining in initial treatment group and by men with secondary treatment by time since diagnosis. ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; AS, active surveillance; RP, radical prostatectomy; RT, radiotherapy.

Table 4.

Mean number of days on sick leave in men remaining on initial treatment and in men with secondary treatment during the first 5 years after diagnosis

| State | Secondary treatment* | Active surveillance | Radical prostatectomy | Radiotherapy | |

| Length of stay†, days (95% CI) | Length of stay†, days (95% CI) | Length of stay†, days (95% CI) | |||

| Sick leave | All cause |

All men | 69 (63 to 75) | 95 (91 to 100) | 117 (103 to 131) |

| None | 41 (36 to 46) | 83 (79 to 87) | 111 (97 to 125) | ||

| RT | 5 (3 to 6) | 10 (8 to 11) | |||

| RP | 21 (18 to 24) | ||||

| ADT | 2 (0 to 3) | 3 (2 to 4) | 6 (2 to 10) | ||

| Prostate cancer | All men | 17 (15 to 19) | 46 (44 to 48) | 44 (38 to 50) | |

| None | 2 (1 to 2) | 40 (38 to 41) | 41 (35 to 46) | ||

| RT | 2 (1 to 2) | 5 (4 to 5) | |||

| RP | 12 (11 to 14) | ||||

| ADT | 1 (0 to 2) | 2 (1 to 2) | 3 (1 to 6) | ||

| Depression, anxiety, stress | All men | 9 (7 to 12) | 10 (8 to 12) | 12 (7 to 17) | |

| None | 6 (4 to 8) | 9 (7 to 11) | 12 (7 to 17) | ||

| RT | 1 (0 to 1) | 1 (0 to 1) | |||

| RP | 2 (1 to 3) | ||||

| ADT | 0 (0 to 1) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) | ||

| Other |

All men | 43 (38 to 48) | 40 (36 to 43) | 61 (51 to 71) | |

| None | 33 (28 to 38) | 34 (31 to 37) | 58 (49 to 67) | ||

| RT | 2 (1 to 3) | 4 (3 to 5) | |||

| RP | 7 (4 to 9) | ||||

| ADT | 1 (0 to 1) | 1 (1 to 2) | 3 (0 to 5) | ||

*RP includes men treated with RP±RT and ADT includes men treated with ADT±RT/RP.

†Number of days may not add up because of rounding.

ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; RP, radical prostatectomy; RT, radiotherapy.

Discussion

In this nationwide study of men with localised low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer, active surveillance was the management strategy with the least impact on working life. In the first 5 years of diagnosis, men on active surveillance spent on average 17 days on prostate cancer-specific sick leave, which was less than half as many sick leave days associated with primary radical prostatectomy (46 days) or radiotherapy (44 days). The pattern was similar after adjusting for cancer and sociodemographic characteristics. From a long-term perspective, there were no major differences between treatment strategies in terms of influence on work at 5 years.

The use of active surveillance has increased over time and now represents the dominant treatment strategy in men with low-risk prostate cancer.22–24 While other studies have reported on functional outcomes and quality of life,25–27 our study is the first to describe and quantify the impact of active surveillance on sick leave and disability pension receipt. In our study, men who remained on active surveillance had virtually the same amount of sick leave days as prostate cancer-free men. Men who subsequently converted to radical therapy accounted for almost all of the days on prostate cancer-specific sick leave. The remaining excess in days lost from work in men on active surveillance were due to other diseases: men on active surveillance had the highest proportion of death from other causes, which may reflect that some men were on active surveillance due to a high comorbidity burden.28

There is a concern that being on active surveillance is associated with increased risk of psychological distress.29 Although we observed slightly increased levels of sick leave due to depression, anxiety and other stress-related disorders among men in all treatment strategies compared with prostate cancer-free men, our findings also suggest that advanced cancer characteristics, and not initial treatment strategy, is the key driver. Most previous studies have not found evidence of an increased risk of mental health problems among men on active surveillance,26 30 whereas advanced prostate cancer stage has been linked to anxiety-related hospitalisations31 and even suicide.32 This suggests that men with more advanced prostate cancer may benefit from targeted psychosocial interventions.

The consequences of treatment choice on working life seem to be strongest during the first year after diagnosis, during which around 60%–80% of men treated for prostate cancer have at least one period of sick leave.8 11 Depending on the type of surgery, the median time to return to work after radical prostatectomy has been reported to be between 35 and 48 days.8 9 18 In the present study, men treated with radical prostatectomy spent on average 46 days on prostate cancer-specific sick leave in the first 5 years after diagnosis. From both our analysis and previous studies, it is clear that most sick leave days can be attributed to the time immediately after surgery. Although treatment for prostate cancer can have long-term consequences on urinary, sexual and bowel function,33 more than 90% of men in the present study who were treated radically were free from sick leave, disability pension receipt and death 5 years after diagnosis, similar to the corresponding proportion in age and residency-matched prostate cancer-free men. Our estimates are largely in agreement with the few earlier studies with comparable data.10 11 In those studies, 91% of men treated with radiotherapy were back to work 1 year after diagnosis,11 and 88% of men treated with radical prostatectomy remained in the workforce 3 years after diagnosis.10 Although adverse events such as urinary leakage seem to have an impact on work in the first years following diagnosis,10 34 our study indicates that it is mainly men with cancer progression and secondary treatments that are on sick leave from 5 years after their prostate cancer diagnosis.

Limitations of our study included the non-randomised design, lack of data for sick leave periods less than 15 days and no detailed information on unemployment and early old-age retirement. From age 61 years, all men with an income from work can obtain old-age pension from the Swedish Pension Agency, although over 80% chose to retire after age 65.35 In the present study, a proportion of men classified as being in the workforce will thus be retired or unemployed, or be on short-term sick leave. Because of the non-randomised design and possible confounding by indication, the data at hand cannot be used for direct comparisons of treatment groups. While the pattern of sick leave in men on active surveillance was strikingly different from that of men with radical therapy, comparisons between radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy should not be made without taking the uneven distribution of baseline characteristics into account, which may not be possible to fully account for using regression adjustment. We included several important sociodemographic and clinical factors in the analysis, but lacked information on factors not captured by national registers, including factors related to workload and work environment. Furthermore, the present analysis does not distinguish between part-time and full-time sick leave. Future studies should address the influence of choice of treatment strategy on part-time sick leave, and include shorter sick leave periods.

A major strength of our study was the use of a population-based register covering virtually all men with prostate cancer in Sweden, cross-linked to several other national registers. We were able to study all sick leave periods longer than 14 days and all periods with disability pension receipt, with information on the underlying diagnosis for the absence from work. The use of multistate Markov models allowed us to account for the complexity of the data with repeated events and competing risks. We have presented both non-parametric (unadjusted) and parametric (adjusted) estimates, which complement each other in terms of underlying assumptions and covariate control. Although the level of sick leave varies between countries because of legislation and entitlement to benefits, our main findings are generalisable also to several other countries. Since prostate cancer treatment and treatment side effects can be expected to be similar across countries, the relative impact on working life is likely to be in the same direction even when the underlying proportions of sick leave are different.

Conclusions

In conclusion, participation in working life was strongly related to treatment type in men with localised prostate cancer, especially in the first year after diagnosis. Men on active surveillance had the fewest sick leave days, whereas radical therapy was associated with considerably more days away from work. During subsequent follow-up, only a small proportion of men within all treatment strategies were on sick leave or disability pension, with cancer progression as a major underlying reason. Our findings add to the understanding of the consequences of treatment-related side effects, and provide absolute measures of sick leave that are easy to understand. Our findings can inform men diagnosed with localised prostate cancer on how different treatment strategies may affect their working lives.

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by the continuous work of the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden steering group: PS (chairman), Anders Widmark, Camilla Thellenberg, Ove Andrén, Ann-Sofi Fransson, Magnus Törnblom, Stefan Carlsson, Marie Hjälm-Eriksson, David Robinson, Mats Andén, Jonas Hugosson, Ingela Franck Lissbrant, Maria Nyberg, Ola Bratt, René Blom, Lars Egevad, Calle Waller, Olof Akre, Per Fransson, Eva Johansson, Fredrik Sandin and Karin Hellström.

Footnotes

Contributors: Data access: AP had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: AP, MC, MV, LH, PS, ML. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: AP, MC, MV, LH, PS, ML. Statistical analysis: AP and MC. Drafting of the manuscript: AP. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AP, MC, MV, LH, PS, ML. Obtained funding: ML. Study supervision: ML and PS.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (521-2012-3047) and the Swedish Cancer Society (14-0324).

Competing interests: ML owns Pfizer and AstraZeneca shares.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at Uppsala University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The data cannot be made publically available due to ethical and legal reasons. Data may be made available for research purposes after ethical approval and permission from register holders.

References

- 1.Pettersson A, Robinson D, Garmo H, et al. Age at diagnosis and prostate cancer treatment and prognosis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Oncol 2018;29:377 10.1093/annonc/mdx742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pompe RS, Smith A, Bandini M, et al. Tumor characteristics, treatments, and oncological outcomes of prostate cancer in men aged ≤50 years: a population-based study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2018;21:71–7. 10.1038/s41391-017-0006-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlsson S, Drevin L, Loeb S, et al. Population-Based study of long-term functional outcomes after prostate cancer treatment. BJU Int 2016;117:E36–45. 10.1111/bju.13179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen RC, Rumble RB, Loblaw DA, et al. Active surveillance for the management of localized prostate cancer (cancer care Ontario guideline): American Society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2182–90. 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bul M, Zhu X, Rannikko A, et al. Radical prostatectomy for low-risk prostate cancer following initial active surveillance: results from a prospective observational study. Eur Urol 2012;62:195 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loeb S, Folkvaljon Y, Makarov DV, et al. Five-Year nationwide follow-up study of active surveillance for prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2015;67:233–8. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hohwü L, Akre O, Pedersen KV, et al. Open retropubic prostatectomy versus robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: a comparison of length of sick leave. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2009;43:259–64. 10.1080/00365590902834802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plym A, Chiesa F, Voss M, et al. Work disability after robot-assisted or open radical prostatectomy: a nationwide, population-based study. Eur Urol 2016;70:64–71. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.12.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yaxley JW, Coughlin GD, Chambers SK, et al. Robot-Assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus open radical retropubic prostatectomy: early outcomes from a randomised controlled phase 3 study. Lancet 2016;388:1057–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30592-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahl S, Loge JH, Berge V, et al. Influence of radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer on work status and working life 3 years after surgery. J Cancer Surviv 2015;9:172 10.1007/s11764-014-0399-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sveistrup J, Mortensen OS, Rosenschöld PM, et al. Employment and sick leave in patients with prostate cancer before, during and after radiotherapy. Scand J Urol 2016;50:164–9. 10.3109/21681805.2015.1119190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomic K, Berglund A, Robinson D, et al. Capture rate and representativity of the National prostate cancer register of Sweden. Acta Oncol 2015;54:158–63. 10.3109/0284186X.2014.939299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Hemelrijck M, Garmo H, Wigertz A, et al. Cohort Profile Update: The National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden and Prostate Cancer data Base--a refined prostate cancer trajectory. Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:73 10.1093/ije/dyv305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Hemelrijck M, Wigertz A, Sandin F, et al. Cohort profile: the National prostate cancer register of Sweden and prostate cancer data base Sweden 2.0. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:956–67. 10.1093/ije/dys068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gran JM, Lie SA, Øyeflaten I, et al. Causal inference in multi-state models-sickness absence and work for 1145 participants after work rehabilitation. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1082 10.1186/s12889-015-2408-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allignol A, Schumacher M, Beyersmann J. Empirical Transition Matrix of Multi-State Models: The etm Package. J Stat Softw 2011;38:1 10.18637/jss.v038.i04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crowther MJ, Lambert PC. Parametric multistate survival models: flexible modelling allowing transition-specific distributions with application to estimating clinically useful measures of effect differences. Stat Med 2017;36:4719–42. 10.1002/sim.7448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Mechow S, Graefen M, Haese A, et al. Return to work following robot-assisted laparoscopic and open retropubic radical prostatectomy: a single-center cohort study to compare duration of sick leave. Urol Oncol 2018;36:309 e1 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Datta S, Satten GA. Estimation of integrated transition hazards and stage occupation probabilities for non-Markov systems under dependent censoring. Biometrics 2002;58:792–802. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2002.00792.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook RJ, Lawless J. Multistate models for the analysis of life history data. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glidden DV. Robust inference for event probabilities with non-Markov event data. Biometrics 2002;58:361–8. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2002.00361.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loeb S, Folkvaljon Y, Curnyn C, et al. Uptake of active surveillance for Very-Low-Risk prostate cancer in Sweden. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1393 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Womble PR, Montie JE, Ye Z, et al. Contemporary use of initial active surveillance among men in Michigan with low-risk prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2015;67:44–50. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR. Trends in management for patients with localized prostate cancer, 1990-2013. JAMA 2015;314:80 10.1001/jama.2015.6036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barocas DA, Alvarez J, Resnick MJ, et al. Association between radiation therapy, surgery, or observation for localized prostate cancer and patient-reported outcomes after 3 years. JAMA 2017;317:1126 10.1001/jama.2017.1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, et al. Patient-Reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1425–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeldres C, Cullen J, Hurwitz LM, et al. Prospective quality-of-life outcomes for low-risk prostate cancer: active surveillance versus radical prostatectomy. Cancer 2015;121:2465 10.1002/cncr.29370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stattin P, Holmberg E, Johansson J-E, et al. Outcomes in localized prostate cancer: national prostate cancer register of Sweden follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:950–8. 10.1093/jnci/djq154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruane-McAteer E, Porter S, O'Sullivan JM, et al. Active surveillance for favorable-risk prostate cancer: is there a greater psychological impact than previously thought? A systematic, mixed studies literature review. Psychooncology 2017;26:1411–21. 10.1002/pon.4311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellardita L, Valdagni R, van den Bergh R, et al. How does active surveillance for prostate cancer affect quality of life? A systematic review. Eur Urol 2015;67:637–45. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bill-Axelson A, Garmo H, Nyberg U, et al. Psychiatric treatment in men with prostate cancer--results from a Nation-wide, population-based cohort study from PCBaSe Sweden. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2195 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bill-Axelson A, Garmo H, Lambe M, et al. Suicide risk in men with prostate-specific antigen-detected early prostate cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study from PCBaSe Sweden. Eur Urol 2010;57:390–5. 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L, et al. Long-Term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Scandinavian prostate cancer Group-4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:891–9. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70162-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett D, Kearney T, Donnelly DW, et al. Factors influencing job loss and early retirement in working men with prostate cancer-findings from the population-based life after prostate cancer diagnosis (LAPCD) study. J Cancer Surviv 2018;12:669–78. 10.1007/s11764-018-0704-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Swedish Pensions Agency Medelpensioneringsålder och utträdesålder 2013 [Expected effective retirement age in 2013], 2014. Available: https://www.pensionsmyndigheten.se

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032914supp001.pdf (204.4KB, pdf)