Abstract

Objectives

This paper aims to investigate resident, facility and country characteristics associated with length of stay in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) across six European countries.

Setting

Data from a cross-sectional study of deceased residents, conducted in LTCFs in Belgium, England, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands and Poland.

Participants

All residents aged 65 years and older at admission who died in a 3-month period residing in a proportional random sample of LTCFs were included.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was length of stay in days, calculated from date of admission and date of death. Resident, facility and country characteristics were included in a proportional hazards model.

Results

The proportion of deaths within 1 year of admission was 42% (range 32%–63%). Older age at admission (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.06), being married/in a civil partnership at time of death (HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.89), having cancer at time of death (HR 1.60, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.10) and admission from a hospital (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.43 to 2.37) or another LTCF (HR 1.81, 95% CI 1.37 to 2.40) were associated with shorter lengths of stay across all countries. Being female (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.90) was associated with longer lengths of stay.

Conclusions

Length of stay varied significantly between countries. Factors prior to LTCF admission, in particular the availability of resources that allow an older adult to remain living in the community, appear to influence length of stay. Further research is needed to explore the availability of long-term care in the community prior to admission and its influence on the trajectories of LTCF residents in Europe.

Keywords: dementia, epidemiology, geriatric medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study sample included a large, representative sample of residents in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) across six European countries.

The cohort of residents was identified retrospectively after death, meaning that there was no loss to follow-up at the end of the study.

The study collected data on LTCF characteristics, including LTCF type and size.

Health-related characteristics were measured either at death or in the last month/week of life, limiting the generalisability of the findings to resident characteristics at LTCF admission.

The study was limited to data collected from LTCF staff members, increasing the likelihood of recall bias.

Introduction

As the population ages, the need for accessible, appropriate long-term care provision will become a global priority. Despite being reported as the least preferred place of death, older adults with dementia and multiple, complex conditions often die in long-term care facilities (LTCFs), although the proportion of deaths differs significantly between countries.1–5 In England and Wales, LTCFs are projected to become the most common place of death for older adults by 2040.6

Previous reviews of studies containing community-based samples of older adults have identified numerous factors predictive of future LTCF admission, with older adults with dementia more likely to be admitted to an LTCF than those without.7 8 Postadmission, the factors associated with shorter and longer length of stay in an LTCF have also been explored9–14; a systematic review of these factors identified shorter lengths of stay associated with older age, being male, having a cancer diagnosis, shortness of breath, receipt of oxygen therapy and residence in an LTCF providing nursing care.15 In particular, the review found stronger evidence for the association of poor physical functioning and shorter lengths of stay, compared with cognitive functioning. The findings of the review were limited as no international studies using data comparable between countries were identified and few studies included characteristics related to the facility or used data collected at time points postadmission. More recently, length of stay in nursing homes across seven countries has been examined using internationally comparable data from the Services and Health for Elderly in Long TERm care (SHELTER) study.16 The sample was restricted to nursing homes, was neither randomly sampled nor representative of each country, and the findings were not reported between countries.17

In this analysis, we have used data from the Palliative Care for Older People in care and nursing homes in Europe (PACE) study, a retrospective, cross-sectional study of deaths in LTCFs, conducted in six European countries, which aimed to explore quality of dying and end-of-life care.18 The PACE study collected data on nationally representative samples of deaths in multiple types of LTCFs, allowing comparison of length of stay between countries. This paper aims to compare length of stay between countries and to investigate the association of resident, facility and country level factors with length of stay from admission to death in LTCFs. In doing so, it will explore differences in the characteristics of LTCF residents with varying lengths of stay and identify heterogeneity in a relatively under researched population.

Methods

Study design and setting

The PACE study undertook a retrospective, cross-sectional study of deaths in LTCFs in Belgium, England, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands and Poland. LTCFs were defined as a collective institutional setting where care is provided for older adult residents who reside there, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for an undefined period of time.19 The care provided includes onsite provision of personal assistance with activities of daily living, nursing and medical care may be provided onsite or by nursing and medical professionals working from an organisation external to the setting.19

In each country, a proportional random sampling framework of LTCFs was developed using national lists of LTCFs. In Italy, no national list of LTCFs was available, therefore, a cluster of nursing homes interested in research was used.17 In England, LTCFs were also recruited from Enabling Research in Care Homes, a network of LTCFs with an interest in research participation.20 The methods used to recruit the LTCF and ethical approvals are discussed in the study protocol and primary outcomes publication.21 22

Patient and public involvement

In each country, feedback on questionnaires for relatives was provided by three relatives recruited by the researchers. In England, a research partnership group including carers and volunteers provided feedback on questionnaires for relatives. Patient and public involvement is discussed in detail in the study protocol.21

Study population

LTCFs that consented to take part in the study were asked to provide data on the facility and on all resident deaths in a retrospective period between 2015 and 2016. Residents were included in the study if they had died in the facility, or after transfer to hospital, in the past 3 months. For each identified resident, structured questionnaires were sent to the administrative staff (response rate 95.7%), facility manager (94.7%) and a staff member who knew the resident (81.6%). Questionnaires were also sent to the resident’s physician and the resident’s relative, however, data from these questionnaires are not used in this analysis.

Independent variables

Factors identified in a systematic review as having strong, moderate or weak evidence of being related to length of stay were used to identify variables of interest collected in the PACE study.15 The construction of each variable is detailed in table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of variables used in the analysis

| Variable name | Variable definition |

| Age | Resident age at the time of admission. |

| Gender | Resident gender at the time of admission. |

| Marital status | Marital status at the time of death, grouped into married/in civil partnership or in long-term relationship, or other (divorced, widowed, never married). |

| Source of admission | Source of admission to the LTCF, grouped into three categories, community, hospital or another LTCF. |

| Cancer | Diagnosis based on the question ‘which of the following conditions was the resident suffering from at the time of death?’ |

| Severe pulmonary disease | |

| Severe diabetes | |

| Pressure ulcers | Whether the resident had decubitus during the last week of life. |

| Stroke | Whether the resident suffered a stroke in the last month of life. |

| Shortness of breath | Whether the resident experienced shortness of breath during the last week of life, classed as not at all, somewhat or a lot. |

| Oxygen therapy | Whether the resident received oxygen therapy in the last week of life. |

| Assistance with eating or drinking | Whether the resident received assistance with eating or drinking in the last week of life. |

| Enteral, parenteral or artificial administration of nutrition | Whether the resident received enteral, parenteral or artificial administration of nutrition in the last week of life. |

| Severity of dementia | Very severe or advanced dementia was classed as a GDS score of 7 and a CPS score of 5 or 6. Severe dementia was classed as a GDS score less than 7 and a CPS score of 5 or 6, or a GDS score of seven and a CPS score of less than 5. Mild or moderate dementia was classed as a GDS score less than 7 and a CPS score of less than 5. |

| General health | The general health of the resident during the last week of life, documented using a scale of 0 to 100, with 0 representing worst health possible and 100 representing the best health possible. |

| Physical functioning | Scores for each BANS-S item ranged from one to four, with one indicating ability and four indicating dependency, which were grouped into no or mild impairments (scores 1–2) versus moderate to severe impairments (scores 3–4). |

| Scores for each EQ-5D item ranged from 0 to 5, with 0 indicating no problems or independence and 5 indicating severe problems or total dependence. These were grouped into no or mild impairments (scores 1–3) versus moderate to severe impairments (scores 4–5). | |

| Physician visits | The no of visits either received or made by a physician during the last month of life. |

| Hospital visits | The no of visits to a hospital, geriatric ward, intensive care unit or general ward (for more than 24 hours) during the last month of life. |

| Emergency department admissions | The no of admissions to a hospital emergency room (for less than 24 hours) during the last month of life. |

| Place of death | Place of death was determined as the facility, a hospice or palliative care unit, or a hospital; including a general ward, intensive care unit or accident and emergency department. |

| LTCF type | Each LTCF was categorised by the type of care offered. Type 1; a facility where onsite care is provided by physicians, nurses and care assistants (present in Italy, Netherlands, Poland); type 2: a facility where onsite care is provided by nurses and care assistants with medical provision provided by local, external primary care services (present in all countries); type 3: a facility where onsite care is provided by care assistants, and nursing with medical provision provided by local, external primary care services (present in England). |

| LTCF funding status | The funding status of the LTCF was either public (non-profit), private (non-profit) or private (for profit). |

| LTCF size | The size of the facility was classed as either small or large, based on average bed number in each country sample. |

BANS-S, Bedford Alzheimer Nursing-Severity Scale; CPS, Cognitive Performance Scale; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 dimensional; GDS, Global Dementia Scale; LTCF, long-term care facility.

Demographic data were collected on resident age, gender, marital status and source of admission. Data on diagnoses of cancer, severe pulmonary disease or severe diabetes were collected, as was the presence of pressure ulcers or history of a stroke. Shortness of breath, oxygen therapy, assistance with eating or drinking and enteral, parenteral or artificial administration of nutrition during the last week of life were also recorded. Severity of dementia was calculated using a combined score from the Global Dementia Scale (GDS)23 and Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS).24

The general health of the resident during the last week of life was documented using a scale of 0–100, with 0 representing worst health possible and 100 representing the best health possible. Physical functioning was determined using two validated questionnaires, the Bedford Alzheimer Nursing-Severity Scale (BANS-S)25 and the EuroQol 5 dimensional (EQ-5D).26 The BANS-S collected data on seven items; ability to dress oneself, sleep cycle, speech, eating, mobility, muscle flexibility and eye contact in the last month of life. The EQ-5D measured quality of life in the last week of life, including anxiety or depression, mobility, self-care, usual activities and pain in the last week of life.

Contact with health services were measured by the number of visits either received or made by a physician, visits to a hospital and admissions to an emergency department. Place of death was determined as the facility, hospice or palliative care unit, or a hospital.

Using the typology developed by Froggatt et al, LTCFs were categorised by the type of care offered.27 These were: type 1; a facility where onsite care is provided by physicians, nurses and care assistants (present in Italy, Netherlands, Poland); type 2: a facility where onsite care is provided by nurses and care assistants with medical provision provided by local, external primary care services (present in all countries); type 3: a facility where onsite care is provided by care assistants, and nursing with medical provision provided by local, external primary care services (present in England). The funding status of the LTCF was either public (non-profit), private non-profit or private for profit. The size of the facility was classed as either small or large, based on average bed number in each country sample.

Dependent variable

Date of admission and date of death were used to calculate length of stay in days in the facility.

Data analysis

First, analysis was conducted by country on all LTCFs within the country sample, with LTCF type included as a factor if more than one type was present in the country. Second, analysis was restricted to residents in type 2 LTCFs, providing onsite nursing care and external medical provision, which are present in all six countries, allowing for comparison of similar LTCF types between countries.

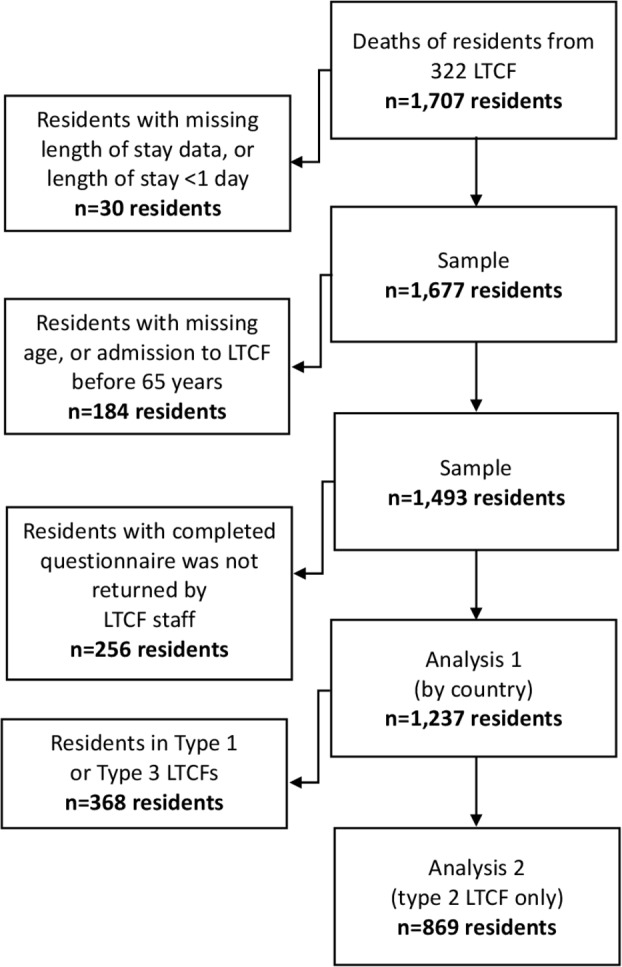

The initial dataset contained data on 1707 participants, as detailed in figure 1. Participants were excluded if length of stay could not be calculated or was less than 1 day, if residents were younger than 65 years on admission, were missing data on age, or no questionnaire was returned by LTCF staff (n=470), resulting in a final sample of 1237 participants. Analysis of LTCFs providing onsite nursing care only was conducted on 869 participants.

Figure 1.

Recruitment to the PACE study and development of the dataset. LTCF, long-term care facility; PACE, Palliative Care for Older People in care and nursing homes in Europe.

Univariate analysis of the variables was performed and significance tested using log rank tests and Kaplan-Meir curves were plotted for each factor. All factors associated with the outcome at a p≤0.2 at univariate analysis were entered into a proportional hazards model, including testing for potential interactions between age, gender and marital status. HRs, 95% CIs and p values that reached a statistical significance of p≤0.05 or p≤0.01 are reported. An HR above 1 indicates a greater risk of death, or a shorter length of stay, and an HR of less than 1 indicates a lower risk of death or a longer length of stay. Multicollinearity was checked using variance inflation factors. Proportionality assumptions were tested by exploring time-dependant covariates and Schoenfeld residuals; and goodness of fit was tested using Cox-Snell residuals. A variable to identify each individual LTCF was added as a random, multilevel effect to account for multiple residents within the same LTCF. The final model used was a parametric proportional hazards model using a Weibull distribution. All analyses were performed using v16 Stata.28

Results

The characteristics of the sample are described in table 2. The non-response analysis did not identify significant differences in the lengths of stay of residents for whom a staff questionnaire was or was not completed and returned (p=0.356). The median length of stay was 73.4 weeks, ranging from 16 weeks in Poland to 103.9 weeks in Belgium. Average length of stay was 126 weeks (SD 157), ranging from 93 (SD 156) weeks in Poland to 163 (SD 182) weeks in Belgium. The number of deaths within 1 year of admission was 521 (42%), ranging from 85 (32%) in Belgium to 165 (63%) in Poland. The mean age of residents at admission was 83.9 years (SD 7.2), ranging from 82.1 (SD 7.8) in Poland to 85.7 (SD 7.4) in England. The percentage of residents who were female was 67%, ranging from 64% in Belgium to 77% in England.

Table 2.

Characteristics of deceased LTCF residents all six countries

| Belgium | England | Finland | Italy | Netherlands | Poland | Overall | P value | |

| n=262 | n=75 | n=252 | n=192 | n=193 | n=263 | n=1237 | ||

| No of LTCFs (average number of residents/range) | 46 (6/1–17) | 37 (2/1–7) | 88 (3/1–11) | 32 (6/1–27) | 42 (5/1–32) | 46 (6/1–24) | 288 (4/1–32) | |

| Average length of stay—mean/SD (weeks) | 163/182 | 147/153 | 119/140 | 102/136 | 146/153 | 93/156 | 126/157 | ≤0.01 |

| Length of stay—median | 103.9 | 101 | 83 | 61.4 | 101.4 | 16 | 73.4 | |

| Deaths within 1 year of admission | 85 (32) | 27 (36) | 93 (37) | 87 (45) | 64 (33) | 165 (63) | 521 (42) | |

| Age at admission | ||||||||

| Mean/SD (years) | 84.6/6.5 | 85.7/7.4 | 83.9/7.2 | 84.2/7.4 | 84.4/6.8 | 82.1/7.8 | 83.9/7.2 | ≤0.01 |

| 65–74 years | 22 (8) | 6 (8) | 26 (10) | 22 (11) | 19 (10) | 51 (19) | 146 (12) | ≤0.01 |

| 75–84 years | 93 (37) | 23 (31) | 107 (42) | 67 (35) | 72 (37) | 107 (41) | 469 (38) | |

| 85–94 years | 136 (52) | 41 (55) | 107 (42) | 90 (47) | 94 (49) | 96 (37) | 564 (46) | |

| 94 years and over | 11 (4) | 5 (7) | 12 (5) | 13 (7) | 8 (4) | 9 (3) | 58 (5) | |

| Gender—female | 168 (64) | 58 (77) | 163 (65) | 131 (68) | 131 (68) | 180 (68) | 831 (67) | 0.43 |

| Marital status—married or in a civil partnership | 61 (23) | 14 (19) | 58 (23) | 47 (24) | 50 (26) | 30 (11) | 260 (21) | ≤0.01 |

| Source of admission | ≤0.01 | |||||||

| Community | 96 (37) | 39 (52) | 75 (30) | 92 (48) | 94 (49) | 136 (52) | 532 (43) | |

| Hospital | 81 (31) | 18 (24) | 86 (34) | 59 (31) | 28 (15) | 93 (35) | 365 (30) | |

| Other LTCF | 30 (12) | 16 (21) | 68 (27) | 31 (16) | 32 (17) | 25 (10) | 202 (16) | |

| Place of death | ≤0.01 | |||||||

| LTCF | 214 (82) | 62 (83) | 213 (85) | 165 (86) | 172 (89) | 214 (81) | 1040 (84) | |

| Hospice/PCU | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 23 (9) | 0 (0) | 11 (5) | 48 (18) | 83 (7) | |

| Hospital | 47 (18) | 12 (16) | 2 (1) | 23 (12) | 6 (3) | 1 (0) | 91 (7) | |

| Cancer | 36 (14) | 14 (19) | 36 (14) | 36 (19) | 34 (18) | 25 (10) | 181 (15) | 0.08 |

| Severe pulmonary disease | 40 (15) | 8 (11) | 20 (8) | 30 (16) | 27 (14) | 35 (13) | 160 (13) | 0.13 |

| Severe diabetes | 20 (8) | 2 (3) | 23 (9) | 27 (14) | 12 (6) | 30 (11) | 114 (9) | 0.02 |

| Stroke | 24 (9) | 6 (8) | 12 (5) | 25 (13) | 9 (5) | 42 (16) | 118 (10) | ≤0.01 |

| Pressure ulcers | 49 (19) | 7 (9) | 44 (17) | 72 (38) | 33 (18) | 91 (35) | 296 (24) | ≤0.01 |

| General health—mean/SD† | 31.7/24.2 | 33.2/22.9 | 24.4/21.8 | 20.1/19.9 | 29.2/21 | 26.9/25.1 | 27.1/23 | ≤0.01 |

| Dementia | ≤0.01 | |||||||

| Resident did not have dementia | 92 (35) | 25 (33) | 40 (16) | 41 (21) | 74 (38) | 66 (25) | 338 (27) | |

| Mild or moderate dementia | 24 (9) | 11 (15) | 43 (17) | 14 (7) | 28 (15) | 14 (5) | 134 (11) | |

| Severe dementia | 45 (17) | 10 (13) | 54 (21) | 39 (20) | 34 (18) | 32 (12) | 214 (17) | |

| Very severe or advanced dementia | 77 (29) | 17 (23) | 71 (28) | 64 (33) | 52 (27) | 93 (35) | 374 (30) | |

| Assistance with eating or drinking | 190 (73) | 49 (65) | 197 (78) | 159 (83) | 140 (73) | 225 (86) | 960 (78) | ≤0.01 |

| Enteral, parenteral or artificial administration of nutrition | 15 (6) | 5 (7) | 19 (8) | 81 (42) | 6 (3) | 142 (54) | 268 (22) | ≤0.01 |

| Shortness of breath | ≤0.01 | |||||||

| Not at all | 120 (46) | 43 (57) | 83 (33) | 86 (45) | 90 (47) | 72 (27) | 494 (40) | |

| Somewhat | 90 (34) | 21 (28) | 111 (44) | 64 (33) | 56 (29) | 131 (50) | 473 (38) | |

| A lot | 39 (15) | 8 (11) | 44 (17) | 30 (16) | 43 (22) | 44 (17) | 208 (17) | |

| Oxygen therapy | 57 (22) | 7 (9) | 57 (23) | 120 (63) | 24 (12) | 94 (36) | 359 (29) | ≤0.01 |

| EQ-5D (moderate or severe problems) | ||||||||

| Anxiety or depression | 103 (39) | 21 (28) | 84 (33) | 103 (54) | 92 (48) | 135 (51) | 538 (43) | ≤0.01 |

| Mobility | 237 (90) | 70 (93) | 237 (94) | 182 (95) | 174 (90) | 250 (95) | 1150 (93) | 0.01 |

| Self-care | 245 (94) | 71 (95) | 241 (96) | 183 (95) | 175 (91) | 250 (95) | 1165 (94) | ≤0.01 |

| Usual activities | 243 (93) | 67 (89) | 241 (96) | 187 (97) | 177 (92) | 253 (96) | 1168 (94) | ≤0.01 |

| Pain | 130 (50) | 31 (41) | 167 (66) | 99 (52) | 124 (64) | 179 (68) | 730 (59) | ≤0.01 |

| BANS-S (moderate or severe impairment) | ||||||||

| Dressing | 231 (88) | 68 (91) | 235 (93) | 185 (96) | 164 (85) | 232 (88) | 1115 (90) | ≤0.01 |

| Sleeping | 94 (36) | 18 (24) | 101 (40) | 91 (47) | 54 (28) | 161 (61) | 519 (42) | ≤0.01 |

| Speech | 129 (49) | 24 (32) | 131 (52) | 130 (68) | 69 (36) | 178 (68) | 661 (53) | ≤0.01 |

| Eating | 144 (55) | 43 (57) | 176 (70) | 163 (85) | 104 (54) | 210 (80) | 840 (68) | ≤0.01 |

| Mobility | 200 (76) | 59 (79) | 207 (82) | 178 (93) | 139 (72) | 229 (87) | 1012 (82) | ≤0.01 |

| Muscle flexibility | 123 (47) | 29 (39) | 189 (75) | 142 (74) | 104 (54) | 197 (75) | 784 (63) | ≤0.01 |

| Eye contact | 71 (27) | 13 (17) | 55 (22) | 79 (41) | 35 (18) | 108 (41) | 361 (29) | ≤0.01 |

| Physician visits | ≤0.01 | |||||||

| None | 4 (2) | 5 (7) | 35 (14) | 44 (23) | 3 (2) | 28 (11) | 119 (10) | |

| One to four visits | 75 (29) | 47 (63) | 116 (46) | 40 (21) | 62 (32) | 56 (21) | 396 (32) | |

| Five or more | 49 (19) | 15 (20) | 54 (21) | 34 (18) | 101 (52) | 97 (37) | 350 (28) | |

| Hospital visits | ≤0.01 | |||||||

| None | 188 (72) | 56 (75) | 192 (76) | 164 (85) | 157 (81) | 170 (65) | 927 (75) | |

| One or more | 62 (24) | 19 (25) | 53 (21) | 19 (10) | 31 (16) | 49 (19) | 233 (19) | |

| Emergency department admissions | 0.02 | |||||||

| None | 218 (83) | 58 (77) | 206 (82) | 149 (78) | 170 (88) | 209 (79) | 1010 (82) | |

| One or more | 31 (12) | 14 (19) | 39 (15) | 29 (15) | 17 (9) | 19 (7) | 149 (12) | |

| LTCF type | ≤0.01 | |||||||

| Type 1—onsite nursing/onsite GP | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 46 (24) | 105 (54) | 165 (63) | 316 (26) | |

| Type 2—onsite nursing/offsite GP | 262 (100) | 39 (52) | 252 (100) | 135 (70) | 83 (43) | 98 (37) | 869 (70) | |

| Type 3—offsite nursing/offsite GP | 0 (0) | 36 (48) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 36 (3) | |

| LTCF funding status | ≤0.01 | |||||||

| Public—non-profit | 128 (49) | 2 (3) | 197 (78) | 65 (34) | 188 (97) | 165 (63) | 745 (60) | |

| Private—non profit | 117 (45) | 9 (12) | 24 (10) | 44 (23) | 0 (0) | 92 (35) | 286 (23) | |

| Private—profit | 17 (6) | 64 (85) | 28 (11) | 72 (38) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 185 (15) | |

| LTCF size | 0.93 | |||||||

| Small | 138 (53) | 40 (53) | 131 (52) | 96 (50) | 107 (55) | 137 (52) | 649 (52) | |

| Large | 124 (47) | 35 (47) | 121 (48) | 85 (44) | 81 (42) | 126 (48) | 572 (46) |

Unless otherwise stated data is reported as frequencies and percentages.

*Higher scores indicate better general health. Missing data: gender n=8, marital status n=90, source of admission n=138, place of death n=23, cancer n=55, severe pulmonary disease n=55, severe diabetes n=55, stroke n=127, pressure ulcers n=32, general health n=32, dementia n=177, assistance with eating or drinking n=43, shortness of breath n=62, oxygen therapy n=44, EQ-5D: anxiety or depression n=43, mobility n=25, self-care n=26, usual activities n=24, pain n=31, BANS-S: dressing n=26, sleeping n=33, speech n=30, eating n=26, mobility n=26, muscle flexibility n=32, eye contact n=27. Physician visits n=372, hospital visits n=77, emergency department admissions n=78, LTCF type n=16, LTCF ownership n=21, LTCF size n=16. P values calculated using Pearson X2 two and one-way ANOVAs.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BANS-S, Bedford Alzheimer Nursing-Severity Scale; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 dimensional; GP, general practitioner; LTCF, long-term care facility; PCU, palliative care unit.

Analysis of all LTCFs by country

Table 3 shows the results of the proportional hazards model for each of the six countries, results that reached a statistical significance of p≤0.05 or p≤0.01 are indicated.

Table 3.

Multilevel proportional hazard model—factors associated with length of stay within each country

| Belgium | England | Finland | Italy | Netherlands | Poland | |||||||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Age at admission | 1.05** | 1.02 to 1.08 | 1.09** | 1.02 to 1.16 | 1 | 0.95 to 1.05 | 1.04** | 1.01 to 1.07 | 1.04* | 1 to 1.08 | 1.07* | 1.03 to 1.12 |

| Gender—female | 0.7 | 0.48 to 1.02 | 0.12** | 0.04 to 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.95 to 1.05 | 0.75 | 0.48 to 1.17 | 0.64 | 0.39 to 1.05 | 0.42* | 0.21 to 0.86 |

| Married/civil partnership#female | 6.45* | 1.21 to 34.23 | ||||||||||

| Marital status—married or in a civil partnership | 2.65** | 1.68 to 4.16 | 1.01 | 0.27 to 3.7 | 1.2 | 0.73 to 1.96 | 1.55 | 0.92 to 2.6 | 1.93 | 0.8 to 4.65 | ||

| Source of admission—community (ref) | ||||||||||||

| Hospital | 2.62** | 1.8 to 3.81 | 2.03 | 0.74 to 5.59 | 1.83 | 0.7 to 4.83 | 2.58** | 1.31 to 5.08 | 7.04** | 3.11 to 15.94 | ||

| Other LTCF | 2.14** | 1.25 to 3.67 | 1.94 | 0.74 to 5.06 | 2.27 | 0.82 to 6.31 | 2.73** | 1.37 to 5.44 | 0.72 | 0.28 to 1.86 | ||

| Place of death—LTCF (ref) | ||||||||||||

| Hospice/PCU | 1.24 | 0.49 to 3.16 | 1.06 | 0.42 to 2.68 | ||||||||

| Hospital | 1.02 | 0.57 to 1.8 | 58.66** | 4.9 to 702.44 | ||||||||

| Cancer | 1.1 | 0.49 to 2.46 | 1.74 | 0.52 to 5.86 | 1.85* | 1.12 to 3.06 | ||||||

| Severe pulmonary disease | 1.05 | 0.62 to 1.76 | 1.79 | 0.51 to 6.29 | 0.94 | 0.57 to 1.54 | 0.84 | 0.36 to 1.94 | ||||

| Severe diabetes | 0.92 | 0.29 to 2.85 | ||||||||||

| Stroke | 1.64 | 0.32 to 8.4 | 1.05 | 0.35 to 3.12 | ||||||||

| Pressure ulcers | 1.25 | 0.48 to 3.22 | 1.21 | 0.59 to 2.47 | ||||||||

| General health | 0.97 | 0.78 to 1.21 | 1.38 | 0.85 to 2.22 | 0.7 | 0.4 to 1.23 | 1.08 | 0.83 to 1.39 | 0.91 | 0.67 to 1.23 | 1.42 | 0.93 to 2.15 |

| Dementia—resident did not have dementia (ref) | ||||||||||||

| Mild or moderate dementia | 0.23** | 0.08 to 0.68 | 1.64 | 0.55 to 4.91 | 0.58 | 0.28 to 1.21 | 2.03 | 0.99 to 4.14 | 0.59 | 0.13 to 2.55 | ||

| Severe dementia | 0.56 | 0.19 to 1.65 | 0.72 | 0.21 to 2.55 | 0.56* | 0.32 to 0.99 | 1.37 | 0.75 to 2.49 | 0.44 | 0.16 to 1.23 | ||

| Very severe or advanced dementia | 0.15** | 0.06 to 0.37 | 1.14 | 0.37 to 3.52 | 0.69 | 0.4 to 1.17 | 1.56 | 0.86 to 2.81 | 0.63 | 0.27 to 1.46 | ||

| EQ-5D (moderate or severe problems) | ||||||||||||

| Anxiety or depression | 1.27 | 0.86 to 1.88 | 0.77 | 0.38 to 1.58 | 1.18 | 0.74 to 1.86 | 1.24 | 0.67 to 2.28 | ||||

| Mobility | 0.34* | 0.14 to 0.86 | 19.95* | 1.62 to 245.72 | 0.37 | 0.04 to 3.72 | 0.06* | 0 to 0.83 | ||||

| Self-care | 0.99 | 0.23 to 4.26 | 0.57 | 0.05 to 6.62 | 2.37 | 0.19 to 29.46 | ||||||

| Usual activities | 1.11 | 0.32 to 3.82 | ||||||||||

| Pain | 1.14 | 0.77 to 1.67 | 1.51 | 0.69 to 3.28 | 0.83 | 0.4 to 1.69 | ||||||

| BANS-S (moderate or severe impairment) | ||||||||||||

| Dressing | 1.43 | 0.67 to 3.04 | 0.12** | 0.02 to 0.74 | 0.32* | 0.12 to 0.9 | ||||||

| Speech | 0.91 | 0.62 to 1.33 | 0.54 | 0.24 to 1.21 | ||||||||

| Eating | to | 1.43 | 0.45 to 4.5 | 0.66 | 0.2 to 2.25 | |||||||

| Mobility | 0.75 | 0.45 to 1.27 | 0.63 | 0.24 to 1.69 | 0.98 | 0.59 to 1.64 | 2.36 | 0.28 to 19.81 | ||||

| Eye contact | 2.17* | 1.19 to 3.96 | ||||||||||

| Artificial feeding | 0.91 | 0.42 to 1.96 | 0.86 | 0.07 to 10.85 | 1.46 | 0.36 to 5.99 | 0.87 | 0.58 to 1.3 | 3.36 | 0.9 to 12.6 | ||

| Assistance with eating or drinking | 0.83 | 0.54 to 1.28 | 1.03 | 0.45 to 2.33 | 0.53* | 0.3 to 0.92 | ||||||

| Shortness of breath—not at all (ref) | ||||||||||||

| Somewhat | 0.15** | 0.05 to 0.46 | 0.72 | 0.32 to 1.61 | ||||||||

| A lot | 0.84 | 0.19 to 3.78 | 0.55 | 0.18 to 1.66 | ||||||||

| Oxygen therapy | 9.69* | 1.55 to 60.61 | 0.76 | 0.28 to 2.08 | 2.06 | 0.89 to 4.79 | ||||||

| Physician visits—none (ref) | ||||||||||||

| One to four visits | 2.14 | 0.88 to 5.17 | 1.48 | 0.44 to 4.98 | ||||||||

| Five or more | 3.15 | 0.92 to 10.84 | 0.99 | 0.4 to 2.46 | ||||||||

| Hospital visits—none (ref) | ||||||||||||

| One or more | 1.25 | 0.8 to 1.94 | 0.89 | 0.3 to 2.67 | 1.63 | 0.76 to 3.52 | 2.18* | 1.01 to 4.72 | ||||

| Emergency department admissions—none (ref) | ||||||||||||

| One or more | 1.45 | 0.55 to 3.82 | ||||||||||

| LTCF type—type 2—onsite nursing/offsiteGP (ref) | ||||||||||||

| Type 1—onsite nursing/onsite GP | NA | NA | NA | 0.87 | 0.46 to 1.65 | 4.05** | 1.43 to 11.44 | |||||

| Type 3—offsite nursing/offsite GP | NA | 0.11** | 0.04 to 0.31 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||||

| LTCF funding status—public—non-profit (ref) | ||||||||||||

| Private—non-profit | 1.22 | 0.85 to 1.77 | 0.22** | 0.1 to 0.49 | ||||||||

| Private—profit | 1.88 | 0.88 to 4.01 | ||||||||||

| LTCF size—small (ref) | ||||||||||||

| Large | 0.81 | 0.39 to 1.68 | ||||||||||

All factors associated with the outcome at a p value of 0.2 at univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate model.

*P<0.05 **P<0.01.

BANS-S, Bedford Alzheimer Nursing-Severity Scale; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 dimensional; GP, general practitioner; LTCF, long-term care facility; NA, not applicable; PCU, palliative care unit.

In Belgium, older age at admission (HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.08), being married/in a civil partnership (HR 2.65, 95% CI 1.68 to 4.16) and admission from hospital (HR 2.62, 95% CI 1.80 to 3.81) or another LTCF (HR 2.14, 95% CI 1.25 to 3.67) were associated with shorter lengths of stay. Moderate or severe mobility problems (HR 0.34, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.86) were associated with longer lengths of stay.

In England, older age at admission (HR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.16), moderate or severe mobility problems (HR 19.95, 95% CI 1.62 to 245.72) and receipt of oxygen therapy (HR 9.69, 95% CI 1.55 to 60.61) were associated with shorter lengths of stay. Being female (HR 0.12, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.37), moderate or mild dementia (HR 0.23, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.68), very severe or advanced dementia (HR 0.15, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.37), being somewhat short of breath (HR 0.15, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.46) and residing in a type 3 LTCF (HR 0.11, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.31) were associated with longer lengths of stay.

In Finland, the interactions between gender and being married/in a civil partnership (HR 6.45, 95% CI 1.21 to 34.23) were associated with shorter lengths of stay. Moderate or severe impairment in ability to dress oneself (HR 0.12, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.74) was associated with longer lengths of stay.

In Italy, older age at admission (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.07) and having a cancer diagnosis (HR 1.85, 95% CI 1.12 to 3.06) were associated with shorter lengths of stay. Severe dementia (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.99), moderate or severe impairment in ability to dress oneself (HR 0.32, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.90) and assistance with eating or drinking (HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.92) were associated with longer lengths of stay.

In Netherlands, older age at admission (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.08), dying in hospital (HR 58.66, 95% CI 4.90 to 702.44) and admission from hospital (HR 2.58, 95% CI 1.31 to 5.08) or another LTCF (HR 2.73, 95% CI 1.37 to 5.44) were associated with shorter lengths of stay.

In Poland, older age at admission (HR 1.07, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.12), admission from hospital (HR 7.04, 95% CI 3.11 to 15.94), one or more hospital visits (HR 2.18, 95% CI 1.01 to 4.72), moderate or severe eye contact impairment (HR 2.17, 95% CI 1.19 to 3.96) and residing in a type 1 facility (HR 4.05, 95% CI 1.43 to 11.44) were associated with shorter lengths of stay. Being female (HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.86), moderate or severe mobility problems (HR 0.06, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.83) and residing in a not for profit facility (HR 0.22, 95%CI 0.10 to 0.49) were associated with longer lengths of stay.

Analysis of type 2 LTCFs across countries

Table 4 shows the results of the proportional hazards model for type 2 LTCFs across the six countries. Older age at admission (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.06), being married/in a civil partnership (HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.89), admission from a hospital (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.43 to 2.37) or another LTCF (HR 1.81, 95% CI 1.37 to 2.40), having a cancer diagnosis (HR 1.60, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.10) and residing in Italy (HR 1.93, 95% CI 1.25 to 3.00), Poland (HR 1.94, 95% CI 1.27 to 2.96), England (HR 2.18, 95% CI 1.21 to 3.95) or Finland (1.42, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.96) compared with Belgium were associated with shorter lengths of stay. Being female (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.90) was associated with longer lengths of stay.

Table 4.

Multilevel proportional hazards model—factors associated with length of stay in type 2 LTCFs across all six countries

| HR | 95% CI | |

| Age at admission | 1.04** | 1.03 to 1.06 |

| Being female | 0.72** | 0.57 to 0.90 |

| Being married/in a civil partnership | 1.47** | 1.13 to 1.89 |

| Source of admission—community (ref) | ||

| Hospital | 1.84** | 1.43 to 2.37 |

| Other LTCF | 1.81** | 1.37 to 2.40 |

| Place of death—LTCF (ref) | ||

| Hospice/PCU | 1.15 | 0.75 to 1.78 |

| Hospital | 1.30 | 0.81 to 2.07 |

| General health | 0.95 | 0.84 to 1.08 |

| Cancer | 1.60** | 1.22 to 2.10 |

| Severe pulmonary disease | 1.19 | 0.89 to 1.61 |

| EQ-5D (moderate or severe problems) | ||

| Anxiety or depression | 1.10 | 0.87 to 1.37 |

| Pain | 0.93 | 0.74 to 1.18 |

| Mobility | 1.03 | 0.77 to 1.37 |

| BANS-S (moderate or severe impairment) | ||

| Speech | 0.97 | 0.76 to 1.25 |

| Dementia—resident did not have dementia (ref) | ||

| Mild or moderate dementia | 0.87 | 0.62 to 1.22 |

| Severe dementia | 0.85 | 0.63 to 1.14 |

| Very severe or advanced dementia | 0.78 | 0.57 to 1.05 |

| Oxygen therapy | 1.09 | 0.85 to 1.40 |

| Hospital visits—none (ref) | ||

| One or more | 1.29 | 0.97 to 1.72 |

| Emergency department admissions—none (ref) | ||

| One or more | 0.94 | 0.66 to 1.33 |

| LTCF funding status—public—non-profit (ref) | ||

| Private—non-profit | 1.28 | 0.95 to 1.74 |

| Private—profit | 1.10 | 0.74 to 1.65 |

| Country—Belgium (ref) | ||

| Finland | 1.42* | 1.02 to 1.96 |

| Italy | 1.93** | 1.25 to 3.00 |

| Netherlands | 1.24 | 0.83 to 1.84 |

| Poland | 1.94** | 1.27 to 2.96 |

| England | 2.18** | 1.21 to 3.93 |

All factors associated with the outcome at a p value of 0.2 at univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate model.

*P<0.05 **P<0.01.

BANS-S, Bedford Alzheimer Nursing-Severity Scale; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 dimensional; LTCF, long-term care facility; PCU, palliative care unit.

Discussion

Summary of findings

In this study, we have examined the association between resident, facility and country-level factors with length of stay in an LTCF. The results show a large variation in length of stay between residents in the same country and between countries. The analysis identified four factors that are consistently statistically significant across all six countries and between countries; older age at admission, being admitted from a hospital or another LTCF, being married/in a civil partnership and being female.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study that the research team are aware of that compared length of stay until death in multiple types of LTCFs internationally. The data were collected across six European countries, using a standardised collection method within a representative, random, relatively large sample of LTCFs. It would be difficult to achieve a similar dataset in scope and size by combining nationally collected routine data, if such data were available. Previous epidemiological studies of different types of LTCFs have been restricted to nursing homes as one particular type of LTCF or facilities from one organisation17 29 30 potentially limiting the wider applicability of findings.

The main limitation of this analysis that the PACE study was developed to compare the outcomes, quality and costs of palliative and end-of-life care between countries.22 Consequently, much of the data collected were related to either the last month or week of life. Although the data were not collected to explore length of stay in LTCFs, they do allow for such an analysis. The majority of previous research in this area were prospective studies collecting data on explanatory variables at baseline and outcome data on death within a prespecified follow-up period.10–14 In both approaches, changes in the resident’s well-being during residence in the LTCF are potentially missed; however, this analysis is novel in its use of data collected at end of life rather than on LTCF admission. Future research would benefit from collecting data at multiple time points from LTCF admission to death to further explore how changes in resident health are associated with length of stay.

The use of retrospective data is a common approach in palliative care research, with the last 3-month of life commonly used.31–35 The data used in this analysis were reported by LTCF staff, rather than retrieved from medical records, increasing the likelihood of measurement error and recall bias.

Interpretation of findings

The findings indicate that length of stay in an LTCF is associated with pre-existing factors prior to admission. All four characteristics indicate that length of stay in an LTCF is influenced by factors prior to admission, in particular the availability of resources that allow an older adult to remain living in the community. Older adults with care needs in the community commonly receive care from spouses, where available.36 As women generally live longer than men, it is possible that partnerless older women are living in LTCFs longer than older, married men, due to lack of a spousal carer. The findings in Finland indicate that being married reduces the length of stay in women, however, this was not replicated in other countries. In addition to being more likely to enter an LTCF,37 this study indicates that partnerless, older women are also likely to live in an LTCF for longer

Admission to an LTCF often follows a period of hospitalisation or other enhanced care, where return to living in the community is no longer possible.38 In areas where integrated services for older people are well developed, emergency admission to a hospital is lower,39 supporting the idea that while older adults are remaining in the community for as long as possible before LTCF admission, their care needs may not necessarily be being met.

The relationship between physical functioning, cognitive functioning and length of stay is less clear. In two countries, mobility problems were associated with longer lengths of stay, however, in England mobility problems were related to shorter lengths of stay. The relationship between poor mobility and longer lengths of stay could reflect a deterioration from admission to death; on admission, a resident may have few problems with mobility, subsequently declining over time, reflecting poor mobility before death in longer stay residents. It is less clear why residents with better mobility before death would have shorter lengths of stays. One diagnosis, cancer, was associated with shorter lengths of stay in the between country analysis, possibly reflecting the relatively fast period of decline experienced in this condition.40

Dementia was related to longer lengths of stay in Italy and England. Although a diagnosis of dementia has been identified as the strongest predictor of care home admission,8 in this study, it has not been associated with shorter lengths of stay. The differences found here could be explained by the availability of other services; in England and Italy, it may be more difficult to live independently in the community with dementia; therefore, older adults may be admitted to an LTCF earlier, leading to a longer length of stay. Neither physical nor cognitive functioning was associated with shorter lengths of stay in the between country analysis, indicating that factors prior to admission have a greater influence on length of stay.

The findings also provide some evidence to indicate that older adults use services which provide the minimum available care to meet their needs. In Poland and England, shorter lengths of stay were significantly associated with the highest level of care available (type 1 and type 2, respectively). A possible explanation for this could be that admission criteria for facilities providing higher levels of care require residents to have greater health needs, resulting in shorter lengths of stay before death. Further research is needed to explore how the availability of different types of LTCF provision is utilised by the older adult population. In future, research conducting international comparisons in this area may benefit from comparing countries with similar long-term care provision.

Conclusion

Older adults residing in LTCFs are a diverse population with multiple, often complex, healthcare needs. This study has highlighted the need for further research on the trajectories of older adults admitted to LTCFs, and their length of stay. In particular, further attention should be given to ensuring groups likely to have longer lengths of stay, namely partnerless older women, receive appropriate long-term care or other options to remain living in the community are available.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all care homes and their staff for participating in this study, as well as all physicians and relatives. For Poland, we also acknowledge the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Poland (decision NR3202/7.PR/2014/2 dated 25 November 2014). Finally, we thank the ENRICH network for their support of the UK research team. PACE consortium members: Yuliana Gatsolaeva (in place of Zeger De Groote), Federica Mammarella, Martina Mercuri, Mariska Oosterveld-Vlug, Ilona Barańska, Paola Rossi, Ivan Segat, Eleanor Sowerby, Agata Stodolska, Hein van Hout, Anne Wichmann, Eddy Adang, Paula Andreasen, Harriet Finne-Soveri, Agnieszka Pac, Bregje Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Maud ten Koppel, Nele Van Den Noortgate, Jenny T. van der Steen, Myrra Vernooij-Dassen, Tinne Smets, Ruth Piers, Yvonne Engels, Katarzyna Szczerbińska, Marika Kylänen, and the European Association for Palliative Care VZW, European Forum For Primary Care, Age Platform Europe and Alzheimer Europe.

Footnotes

Contributors: DCM designed and conducted the analysis, interpreted the results and prepared the manuscript. SP, TK and KF provided supervision. LVdB, LD, GG, RH, VK, HRP and LP were involved in the design of and data collection in the PACE study, and contributed to the data interpretation and preparation of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by funding from EU FP7 PACE (grant agreement 603111).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: All countries obtained ethical approval from the relevant ethics committee, except in the Netherlands and Italy where this is not needed. In England, the study was approved by Haydock National Research Ethics Committee (reference 15/NW/0205).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. Data can be obtained from the authors on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Calanzani N, Moens K, Cohen J, et al. Choosing care homes as the least preferred place to die: a cross-national survey of public preferences in seven European countries. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:48 10.1186/1472-684X-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Houttekier D, Cohen J, Bilsen J, et al. Place of death of older persons with dementia. A study in five European countries. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:751–6. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02771.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reyniers T, Deliens L, Pasman HR, et al. International variation in place of death of older people who died from dementia in 14 European and non-European countries. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:165–71. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohen J, Pivodic L, Miccinesi G, et al. International study of the place of death of people with cancer: a population-level comparison of 14 countries across 4 continents using death certificate data. Br J Cancer 2015;113:1397–404. 10.1038/bjc.2015.312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Broad JB, Gott M, Kim H, et al. Where do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics. Int J Public Health 2013;58:257–67. 10.1007/s00038-012-0394-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bone AE, Gomes B, Etkind SN, et al. What is the impact of population ageing on the future provision of end-of-life care? Population-based projections of place of death. Palliat Med 2018;32:329–36. 10.1177/0269216317734435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, et al. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 2007;7:13 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, et al. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing 2010;39:31–8. 10.1093/ageing/afp202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hedinger D, Hämmig O, Bopp M, et al. Social determinants of duration of last nursing home stay at the end of life in Switzerland: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:114 10.1186/s12877-015-0111-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heppenstall CP, Broad JB, Boyd M, et al. Progress towards predicting 1-year mortality in older people living in residential long-term care. Age Ageing 2015;44:497–501. 10.1093/ageing/afu206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lucchetti G, Lucchetti ALG, Pires SL, et al. Predictors of death among nursing home patients: a 5-year prospective study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15:234–6. 10.1111/ggi.12324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCann M, O'Reilly D, Cardwell C. A Census-based longitudinal study of variations in survival amongst residents of nursing and residential homes in Northern Ireland. Age Ageing 2009;38:711–7. 10.1093/ageing/afp173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shah SM, Carey IM, Harris T, et al. Mortality in older care home residents in England and Wales. Age Ageing 2013;42:209–15. 10.1093/ageing/afs174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sund Levander M, Milberg A, Rodhe N, et al. Differences in predictors of 5-year survival over a 10-year period in two cohorts of elderly nursing home residents in Sweden. Scand J Caring Sci 2016;30:714–20. 10.1111/scs.12284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moore DC, Keegan TJ, Dunleavy L, et al. Factors associated with length of stay in care homes: a systematic review of international literature. Syst Rev 2019;8:56 10.1186/s13643-019-0973-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vetrano DL, Collamati A, Magnavita N, et al. Health determinants and survival in nursing home residents in Europe: results from the shelter study. Maturitas 2018;107:19–25. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Onder G, Carpenter I, Finne-Soveri H, et al. Assessment of nursing home residents in Europe: the services and health for elderly in long term care (shelter) study. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:5 10.1186/1472-6963-12-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. PACE Consortium PACE - Palliative Care for Older People in care and nursing homes in Europe Brussels: PACE Consortium; 2018 [20/02/2018]. Available: http://www.eupace.eu/

- 19. Froggatt K, Reitinger E. Palliative care in term care settings for older people. Report of an EAPC Taskforce 2010-2012. Milan: European Association of Palliative Care, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Institute for Health Research Enabling research in care Home—a toolkit for researchers (enrich). National Institute for health research, 2016. Available: https://enrich.nihr.ac.uk/ [Accessed 1 Sep 2019].

- 21. Van den Block L, Smets T, van Dop N, et al. Comparing palliative care in care homes across Europe (PACE): protocol of a cross-sectional study of deceased residents in 6 EU countries. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:566.e1–566.e7. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pivodic L, Smets T, Van den Noortgate N, et al. Quality of dying and quality of end-of-life care of nursing home residents in six countries: an epidemiological study. Palliat Med 2018;32:1584–95. 10.1177/0269216318800610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, et al. The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1982;139:1136–9. 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. Mds cognitive performance scale. J Gerontol 1994;49:M174–82. 10.1093/geronj/49.4.M174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bellelli G, Frisoni GB, Bianchetti A, et al. The Bedford Alzheimer nursing severity scale for the severely demented: validation study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997;11:71–7. 10.1097/00002093-199706000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. EuroQol Group EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Froggatt K, Edwards M, Morbey H, et al. Mapping palliative care systems in long term care facilties in Europe. Lancaster, United Kingdom: Lancaster University, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28. StataCorp Stata statistical software: release 16, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gordon AL, Franklin M, Bradshaw L, et al. Health status of UK care home residents: a cohort study. Age Ageing 2014;43:97–103. 10.1093/ageing/aft077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rolland Y, Abellan van Kan G, Hermabessiere S, et al. Descriptive study of nursing home residents from the REHPA network. J Nutr Health Aging 2009;13:679–83. 10.1007/s12603-009-0197-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hunt KJ, Shlomo N, Addington-Hall J. End-Of-Life care and preferences for place of death among the oldest old: results of a population-based survey using VOICES-Short form. J Palliat Med 2014;17:176–82. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bainbridge D, Seow H. Palliative care experience in the last 3 months of life: a quantitative comparison of care provided in residential Hospices, hospitals, and the home from the perspectives of bereaved caregivers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018;35:456–63. 10.1177/1049909117713497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Gendt C, Bilsen J, Stichele RV, et al. Advance care planning and dying in nursing homes in Flanders, Belgium: a nationwide survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:223–34. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van den Block L, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Meeussen K, et al. Nationwide continuous monitoring of end-of-life care via representative networks of general practitioners in Europe. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:73 10.1186/1471-2296-14-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Addington-Hall JM, O'Callaghan AC. A comparison of the quality of care provided to cancer patients in the UK in the last three months of life in in-patient hospices compared with hospitals, from the perspective of bereaved relatives: results from a survey using the voices questionnaire. Palliat Med 2009;23:190–7. 10.1177/0269216309102525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rodríguez M, Minguela Recover M. Ángeles, Camacho Ballesta JA. The importance of the size of the social network and residential proximity in the reception of informal care in the European Union. European Journal of Social Work 2018;21:653–64. 10.1080/13691457.2017.1320523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thomeer MB, Mudrazija S, Angel JL, et al. Relationship status and long-term care facility use in later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2016;71:711–23. 10.1093/geronb/gbv106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sorkin DH, Amin A, Weimer DL, et al. Rationale and study protocol for the nursing home compare plus (NHCPlus) randomized controlled trial: a personalized decision aid for patients transitioning from the hospital to a skilled-nursing facility. Contemp Clin Trials 2016;47:139–45. 10.1016/j.cct.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Imison C, Poteliakhoff E, Thompson J. Older people and emergency bed use: exploring variation. London: The Kings Fund, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cohen-Mansfield J, Skornick-Bouchbinder M, Brill S. Trajectories of end of life: a systematic review. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2018;73:564–72. 10.1093/geronb/gbx093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.