Abstract

BACKGROUND

In 2016, the response to a yellow fever outbreak in Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo led to a global shortage of yellow fever vaccine. As a result, a fractional dose of the 17DD yellow fever vaccine (containing one fifth [0.1 ml] of the standard dose) was offered to 7.6 million children 2 years of age or older and nonpregnant adults in a preemptive campaign in Kinshasa. The goal of this study was to assess the immune response to the fractional dose in a large-scale campaign.

METHODS

We recruited participants in four age strata at six vaccination sites. We assessed neutralizing antibody titers against yellow fever virus in blood samples obtained before vaccination and at 1 month and 1 year after vaccination, using a plaque reduction neutralization test with a 50% cutoff (PRNT50). Participants with a PRNT50 titer of 10 or higher were considered to be seropositive. Those with a baseline titer of less than 10 who became seropositive at follow-up were classified as having undergone seroconversion. Participants who were seropositive at baseline and who had an increase in the titer by a factor of 4 or more at follow-up were classified as having an immune response.

RESULTS

Among 716 participants who completed the 1-month follow-up, 705 (98%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 97 to 99) were seropositive after vaccination. Among 493 participants who were seronegative at baseline, 482 (98%; 95% CI, 96 to 99) underwent seroconversion. Among 223 participants who were seropositive at baseline, 148 (66%; 95% CI, 60 to 72) had an immune response. Lower baseline titers were associated with a higher probability of having an immune response (P<0.001). Among 684 participants who completed the 1-year follow-up, 666 (97%; 95% CI, 96 to 98) were seropositive for yellow fever antibody. The distribution of titers among the participants who were seronegative for yellow fever antibody at baseline varied significantly among age groups at 1 month and at 1 year (P<0.001 for both comparisons).

CONCLUSIONS

A fractional dose of the 17DD yellow fever vaccine was effective at inducing seroconversion in participants who were seronegative at baseline. Titers remained above the threshold for seropositivity at 1 year after vaccination in nearly all participants who were seropositive at 1 month after vaccination. These findings support the use of fractional-dose vaccination for outbreak control. (Funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Yellow fever is a mosquito-borne viral disease endemic to tropical and subtropical regions in Africa and the Americas. Infection with yellow fever virus can result in subclinical to severe illness, characterized by fever, jaundice, and hemorrhage. There were an estimated 51,000 to 380,000 severe cases of yellow fever and 19,000 to 180,000 deaths in Africa in 2013.1 Treatment is managed to address patients’ symptoms. However, the administration of a highly effective vaccine is the primary method for prevention and control. All currently used yellow fever vaccines are live attenuated viral vaccines derived from the 17D strain.2,3 Nearly all studies have shown that one dose induces seroconversion in more than 98% of recipients, and protection is believed to be lifelong.2,4,5

In December 2015, a large yellow fever outbreak began in Angola and spread to the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The outbreak resulted in 962 confirmed cases and more than 7000 suspected cases across the two countries.6 Each year, 6 million doses of yellow fever vaccine are maintained by the World Health Organization (WHO) and partners in a global stockpile that can be used for outbreak response at the request of countries with inadequate vaccine supply.7 However, the outbreaks in Angola and DRC used approximately 30 million doses and depleted the stockpile multiple times during 2016.6

Faced with substantial global supply issues, the WHO reviewed available evidence on dose-sparing strategies for yellow fever vaccination, including four studies involving three cohorts of 175 to 749 healthy adult participants.8–12 Two of the three cohorts were limited to male participants. All the studies showed a robust immune response to fractional doses of yellow fever vaccine as small as one fifth to one tenth of the standard dose. On the basis of this evidence, the WHO concluded that a fractional dose of the yellow fever vaccine could be used in adults and in children 2 years of age or older in response to an emergency situation when the current vaccine supply was insufficient.12

To prevent the spread of yellow fever in Kinshasa, the government planned a preemptive campaign targeting approximately 7.6 million persons during a 10-day period.13 However, there was insufficient vaccine supply available to meet campaign needs. Thus, under guidance from the WHO, the government of the DRC implemented the campaign using a fractional dose of 17DD vaccine (Bio-Manguinhos) at one fifth (0.1 ml) of the standard dose in all nonpregnant adults and in children 2 years of age or older in August 2016. We evaluated the immunologic response to this fractional-dose vaccine delivered in a large-scale vaccination campaign.

METHODS

STUDY PARTICIPANTS AND DESIGN

From August 17 through August 26, 2016, the campaign was conducted at 2404 vaccination sites in Kinshasa.13 We selected 6 vaccination sites across the three geographic sectors of Kinshasa on the basis of economically diverse catchment populations and logistic feasibility. Persons who presented for vaccination at one of these sites were approached for potential inclusion in a convenience sample for the study, with an equal number of participants from four age strata: 2 to 5 years, 6 to 12 years, 13 to 49 years, and 50 years or older. The cutoffs for these age strata were selected on the basis of data regarding immunologic response to the yellow fever vaccine and other vaccines.2,14

All the participants who received fractional-dose vaccination during the campaign were eligible for inclusion unless they reported having immunosuppression, egg allergies, a history of problems with venipuncture, plans to relocate from Kinshasa, or previous yellow fever vaccination within the preceding 2 months. Children under the age of 2 years and pregnant women were ineligible because they received full-dose vaccine according to the campaign operating procedures. The criteria for vaccine administration were determined by the public health authorities in the DRC. All the participants provided limited medical information and written informed consent to obtain blood samples. Parents or legal guardians provided written permission for participants who were 17 years of age or younger. Adolescents between the ages of 13 and 17 years also provided written assent.

STUDY OVERSIGHT

The study was sponsored by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The protocol (available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org) was approved by the medical ethics committee at the University of Kinshasa School of Public Health. In accordance with the human-subjects review procedures of the CDC, it was determined that the CDC was not formally engaged in human-subjects research. The study was designed and supervised by the authors, who vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses and for the adherence of the study to the protocol.

BASELINE VISIT AND VACCINATION

From each participant, we collected data regarding basic demographic characteristics, history of yellow fever vaccination, and recent symptoms compatible with yellow fever disease (specifically, fever with jaundice). A phlebotomist obtained a baseline blood sample before vaccination. Campaign staff members then administered a subcutaneous dose of 17DD yellow fever vaccine at one fifth of the standard dose (0.1 ml) to 764 participants from one of six lots: 253 participants received vaccine from lot 164VFC002Z, 104 from lot 164VFC003Z, 138 from lot 164VFC004Z, 127 from lot 164VFC005Z, 38 from lot 164VFC007Z, and 94 from lot 164VFC008Z; no lot number was recorded for doses administered to 10 participants.

The 17DD vaccine was recommended by the WHO for use in the campaign on the basis of availability, clinical trial data indicating seroresponse to fractional doses, and 5 years of batch-release data.8–10,15 According to these data, one fifth of a dose of the average batch potency had 8709 IU of vaccine per dose, and one fifth of a dose of minimum batch potency had 2692 IU per dose. Both of these doses were above the minimum vaccine potency (1000 IU per dose) set by the WHO.16 The vaccine was packaged in standard 10-dose vials, which resulted in the use of each vial for approximately 50 fractional doses.13 Vaccination was observed by study staff members to ensure receipt of the dose. Adverse events after immunization were monitored as part of the campaign procedures rather than as part of this investigation.

FOLLOW-UP AND TESTING PROCEDURES

At 28 to 35 days after vaccination (1-month follow-up) and at 12 to 13 months (1-year follow-up), participants who returned to the health center were asked about yellow fever symptoms and receipt of medications or medical treatment during the interval between visits. A blood sample was obtained. Female participants of reproductive age were also asked about the date of the last menstrual period or whether they had subsequently determined that they were pregnant at the time of vaccination.

Blood samples that were obtained before vaccination and after vaccination were kept in temperature-controlled coolers during the day and transported each afternoon to Institut National de Recherche Biomedicale, where they were centrifuged and serum was aliquoted into cryovials and stored at −20°C. Serum samples were then shipped to the CDC Arbovirus Diseases Laboratory in Fort Collins, Colorado, where paired baseline and follow-up samples were tested for the presence of neutralizing antibodies against yellow fever virus with the use of the plaque reduction neutralization test with a cutoff of 50% (PRNT50) and a cutoff of 90% (PRNT90), as described previously.17 Here, we report PRNT50 titers, since this cutoff is routinely used in vaccination trials of flavivirus vaccines and is recommended by the WHO for establishing sufficient virus-neutralizing antibody in the serum in vaccine immunogenicity studies conducted by vaccine manufacturers.16,18,19

Participants with a PRNT50 titer of 10 or higher in their sample at baseline were considered to be seropositive. Those who had a baseline PRNT50 titer of less than 10 and who were identified as being seropositive at the 1-month follow-up were classified as having undergone seroconversion. Participants who were seropositive at baseline and had an increase in the titer by a factor of 4 or more at the 1-month follow-up were classified as having had an immune response to vaccination.

Participants who were seronegative (PRNT50 titer, <10) at 1 month after vaccination were offered revaccination with the full dose (0.5 ml) at 1 year. A blood sample was obtained from these participants before revaccination and at 28 to 35 days after their revaccination. The titer of the blood sample that was obtained just before revaccination was used to determine the participant’s immune status at the 1-year follow-up.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We determined that a sample of 190 participants in each of four age groups (total, 760) would allow for an estimation of the immune response in each group, based on an estimated rate of immune response of 92% among the participants, with a 95% Wald confidence interval of ±5% and an attrition rate of 40%. All the participants who had baseline and follow-up samples were included in the 1-month analyses. Only the participants who were included in the 1-month analysis were eligible for inclusion in the 1-year follow-up analysis.

Estimated proportions and 95% confidence intervals were calculated with the use of the Wilson method. We compared the proportion of participants who had undergone seroconversion in groups according to age and sex using Fisher’s exact test. For analyses of immune response in participants who were seropositive at baseline, three subgroups of baseline PRNT50 titers were created: from 10 to 40, from 80 to 320, and 640 or higher. We assessed the association between the baseline-titer subgroup and the immune response using the Cochran–Armitage test for trend. Differences in immune response according to age group and sex were adjusted for baseline titer subgroups with the use of the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare the distributions of titers. Bonferroni corrections were used with pairwise comparisons (alpha level, 0.05; adjusted alpha level, 0.008).

RESULTS

PARTICIPANTS

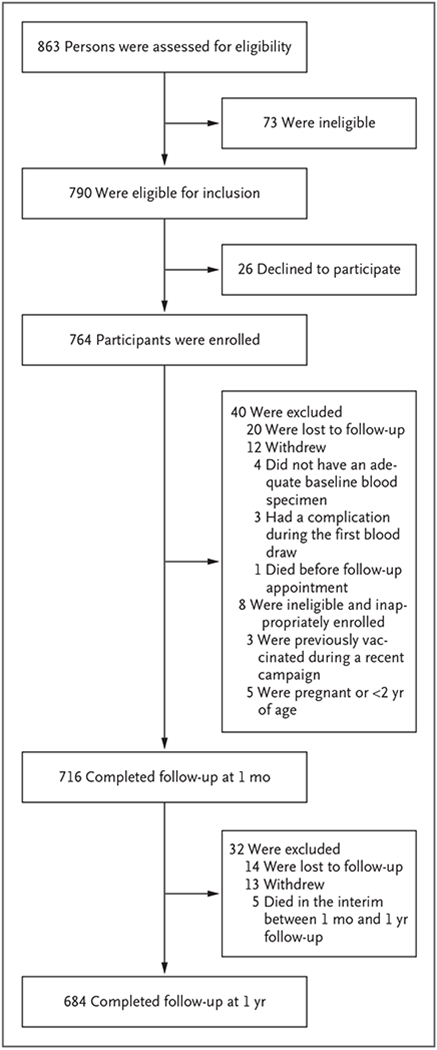

Of the 863 persons who were screened, 790 met the eligibility criteria, and 764 were enrolled; 716 (94%) completed the 1-month follow-up visit, and 684 (90%) completed the 1-year follow-up visit (Fig. 1). Overall, 89 to 98% of the participants in each of the four age groups completed the initial follow-up. Of the participants who attended the 1-month follow-up, 50% were female, and 79 (11%) reported having received previous yellow fever vaccination. All but 5 of those reporting previous vaccination were children 12 years of age or younger (Table 1). A history of previous vaccination was based primarily on oral report. None of the participants who had completed follow-up reported having had symptoms compatible with yellow fever after vaccination. The characteristics of participants with 1-year follow-up data were similar to those of the participants with 1-month follow-up data.

Figure 1. Enrollment and Follow-up.

Of the 40 eligible participants who were excluded from the 1-month analysis, 21 (52%) were female. Of the excluded participants, 20 (50%) were between the ages of 2 and 5 years, 4 (10%) were between the ages of 6 and 12 years, 7 (18%) were between the ages of 13 and 49 years, and 9 (22%) were 50 years of age or older. Investigation by the Ministry of Health determined that the single death that occurred between enrollment and 1-month follow-up was related to a cardiac event and not to vaccination. Of the 32 participants who were excluded from the 1-year analysis, 20 (63%) were female; 11 (34%) were between the ages of 2 and 5 years, 6 (19%) were between the ages of 6 and 12 years, 5 (16%) were between the ages of 13 and 49 years, and 10 (31%) were 50 years of age or older. None of the 5 deaths that occurred between the 1-month and 1-year follow-up were determined to be related to the yellow fever vaccination.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 716 Study Participants at Baseline, According to Age Group.*

| Characteristic | Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–5 Yr (N = 162) | 6–12 Yr (N = 189) | 13–49 Yr (N = 189) | ≥50 Yr (N = 176) | All Ages (N = 716) | |

| number of participants (percent) | |||||

| Female sex | 89 (55) | 87 (46) | 102 (54) | 80 (45) | 358 (50) |

|

| |||||

| Report of previous yellow fever vaccination | 41 (25) | 33 (17) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) | 79 (11) |

|

| |||||

| Oral report only | 37 (23) | 29 (15) | 0 | 3 (2) | 69 (10) |

|

| |||||

| Vaccination card confirmed | 0 | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 4 (1) |

|

| |||||

| Source not recorded | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 6 (1) |

|

| |||||

| Report of symptoms compatible with yellow fever in previous month† | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 7 (1) |

|

| |||||

| Seropositivity at baseline‡ | 85 (52) | 75 (40) | 27 (14) | 36 (20) | 223 (31) |

Percentages in subcategories may not add up to the overall percentage because of rounding.

Symptoms were fever and jaundice.

Seropositivity for neutralizing antibodies against yellow fever virus was defined as a titer on a plaque reduction neutralization test with a cutoff of 50% (PRNT50) of 10 or higher.

VACCINE RESPONSE IN THE OVERALL POPULATION

Of the 716 participants, 705 (98%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 97 to 99) were seropositive after vaccination (Table 2). The proportion who were seropositive did not differ significantly according to age or sex.

Table 2.

Seropositivity at 1 Month and 1 Year, According to Age Group and Sex.*

| Variable | Seropositivity at 1 Month (N = 716) | Seropositivity at 1 Year (N = 684) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P Value | P Value | |||||

| no./total no. | % (95% CI) | no./total no. | % (95% CI) | |||

| All participants | 705/716 | 98 (97–99) | 666/684 | 97 (96–98) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age group | 0.08 | 0.26 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 2–5 yr | 158/162 | 98 (94–99) | 145/151 | 96 (92–98) | ||

|

| ||||||

| 6–12 yr | 189/189 | 100 (98–100) | 180/183 | 98 (95–99) | ||

|

| ||||||

| 13–49 yr | 184/189 | 97 (94–99) | 177/184 | 96 (92–98) | ||

|

| ||||||

| ≥50 yr | 174/176 | 99 (96–100) | 164/166 | 99 (96–100) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Sex | 0.06 | 0.16 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Male | 356/358 | 99 (98–100) | 340/346 | 98 (96–99) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Female | 349/358 | 97 (95–99) | 326/338 | 96 (94–98) | ||

Seropositivity was defined as a result on PRNT50 testing of 10 or higher. P values for the overall comparisons among the subgroups were calculated with the use of Fisher’s exact test at 1 month and 1 year. PRNT90 data are provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Of the 684 participants who completed the 1-year follow-up, 666 (97%; 95% CI, 96 to 98) were seropositive. These participants included 664 who had been seropositive at 1 month and 2 participants who had been seronegative at 1 month but were seropositive at 1 year before subsequent revaccination. All 11 participants who were seronegative at 1 month either underwent seroconversion (9 participants) or had an immune response (2 participants) after receiving the supplementary full dose of yellow fever vaccine. There was no significant association between the proportion who were seropositive at 1 year and either age or sex (Table 2).

VACCINE RESPONSE AMONG PARTICIPANTS WHO WERE SERONEGATIVE AT BASELINE

A total of 493 participants (69%) were seronegative for neutralizing antibodies against yellow fever at baseline (Table 3). Among these participants, seroconversion at 1 month was reported in 482 (98%; 95% CI, 96 to 99). The between-group differences in seroconversion were not significant according to age (P = 0.06). At the 1-month follow-up, participants between the ages of 13 and 49 years had a significantly higher geometric mean titer (2255; 95% CI, 1604 to 3171) than the participants in all other age groups; children between the ages of 2 and 5 years had the lowest geometric mean titer at 487 (95% CI, 293 to 810). The seroconversion rate among male participants (99%; 95% CI, 97 to 100) was significantly higher than that among female participants (96%; 95% CI, 93 to 98) (P = 0.03). However, the geometric mean titers for male participants and female participants did not differ significantly (P = 0.61). Among the 5 female participants of reproductive age who did not undergo seroconversion, none were pregnant on the basis of reports of menstruation in the interval between vaccination and their subsequent follow-up visits.

Table 3.

Geometric Mean Titer (GMT), Seroconversion or Immune Response at 1 Month, and Seropositivity at 1 Year, According to Serostatus at Baseline.*

| Variable | Baseline GMT (95% CI) | Seroconversion or Immune Response at 1 Month (N = 716) | Seropositivity at 1 Year (N = 684) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P Value† | GMT (95% CI) | P Value‡ | P Value† | GMT (95% CI) | P Value ‡ | ||||

| no./total no. (% [95% CI]) | no./total no. (% [95% CI]) | ||||||||

| Seronegative at baseline | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| All participants | NA | 482/493 (98 [96–99]) | NA | 1340 (1117–1607) | NA | 457/475 (96 [94–98]) | NA | 143 (123–166) | NA |

|

| |||||||||

| Age group | 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.11 | <0.001 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| 2–5 yr | NA | 73/77 (95 [87–98]) | 487 (293–810) | 67/73 (92 [83–96]) | 55 (37–80) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| 6–12 yr | NA | 114/114 (100 [97–100]) | 1234 (911–1673) | 108/111 (97 [92–99]) | 100 (74–133) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| 13–49 yr | NA | 157/162 (97 [93–99]) | 2255 (1604–3171)§ | 151/158 (96 [91–98]) | 209 (163–267)¶ | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| ≥50 yr | NA | 138/140 (99 [95–100]) | 1368 (999–1872)‖ | 131/133 (98 [95–100]) | 207 (158–271)¶ | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Sex | 0.03 | 0.61 | 0.15 | 0.46 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Male | 251/253 (99 [97–100]) | 1469 (1155–1870) | 240/246 (98 [95–99]) | 143 (117–175) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Female | 231/240 (96 [93–98]) | 1216 (924–1600) | 217/229 (95 [91–97]) | 143 (114–178) | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Seropositive at baseline | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| All participants | 87 (69–110) | 148/223 (66 [60–72]) | NA | 1292 (1039–1607) | NA | 209/209 (100 [98–100]) | NA | 247 (206–296) | NA |

|

| |||||||||

| Age group | <0.001 | 0.16 | NA | 0.98 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| 2–5 yr | 90 (66–123) | 57/85 (67 [57–76]) | 1114 (788–1576) | 78/78 (100 [95–100]) | 243 (185–320) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| 6–12 yr | 50 (35–72) | 62/75 (83 [73–90]) | 1366 (962–1938) | 72/72 (100 [95–100]) | 242 (177–330) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| 13–49 yr | 160 (65–392) | 17/27 (63 [44–78]) | 2252 (1255–4039) | 26/26 (100 [87–100]) | 273 (158–470) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| ≥50 yr | 160 (79–324) | 12/36 (33 [20–50])** | 1076 (533–2175) | 33/33 (100 [90–100]) | 249 (140–442) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Sex | 0.74 | 0.71 | NA | 0.68 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Male | 71 (51–98) | 73/105 (70 [60–78]) | 1255 (930–1694) | 100/100 (100 [96–100]) | 231 (179–298) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Female | 105 (76–146) | 75/118 (64 [55–72]) | 1326 (964–1823) | 109/109 (100 [97–100]) | 263 (202–341) | ||||

NA denotes not applicable. PRNT90 data are provided in Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix.

P values for the differences in seroconversion (at 1-month follow-up) or percent seropositive (at 1-year follow-up) were calculated according to age group and sex with the use of Fisher’s exact test. P values for the difference in immune response at 1 month were calculated with the use of the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test after adjustment for the baseline titer.

P values for the global test of differences in the GMT at follow-up were calculated with the Kruskal-Wallis test (age group) and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (sex).

At 1-month follow-up, the participants between the ages of 13 and 49 had significantly higher titers than the participants in all other age groups.

At 1-year follow-up, the participants in this category had significantly higher titers than those in the age groups of 2 to 5 years and 6 to 12 years.

At 1-month follow-up, the participants who were 50 years of age or older had significantly higher titers than those in the age group of 2 to 5 years.

At 1-month follow-up, the participants who were 50 years of age or older were significantly less likely to have an immune response than were the participants in all other age groups.

Among the 475 participants who were seronegative at baseline and completed the 1-year follow-up, 457 (96%, 95% CI, 94 to 98) were seropositive (Table 3). Seropositivity at 1 year did not differ significantly according to age group (P = 0.11) or sex (P = 0.15). The distribution of titers at 1 year remained significantly different according to age group (P<0.001), with the highest titers seen in participants between the ages of 13 and 49 years and those who were 50 years of age or older. The difference in the distribution of titers according to sex was not significant (P = 0.46).

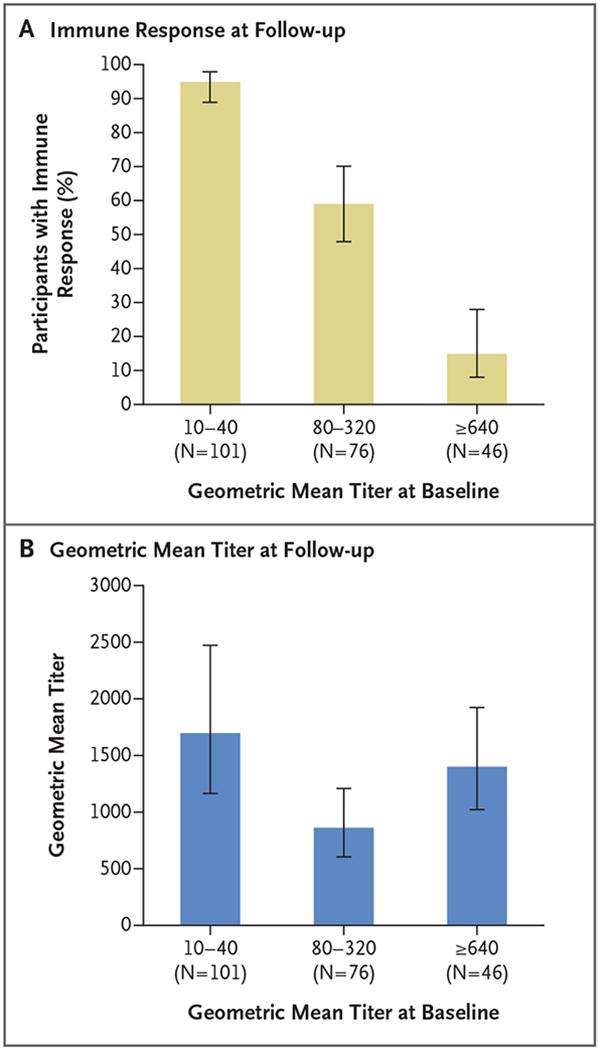

VACCINE RESPONSE AMONG PARTICIPANTS WHO WERE SEROPOSITIVE AT BASELINE

At baseline, 223 participants (31%) were seropositive for neutralizing antibodies against yellow fever virus (Table 3). In this subgroup, an immune response (titer of ≥4 times the baseline value) was elicited in 148 (66%; 95% CI, 60 to 72). There was an inverse relationship between a participant’s baseline titer and the likelihood of having an immune response at 1 month (P<0.001) (Fig. 2A). A total of 95% of the participants with a titer of 10 to 40 had an immune response, as compared with only 15% of the participants who had a titer of 640 or higher at baseline. An anamnestic response was more notable among those with a lower baseline titer (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Immune Response and Geometric Mean Titer at 1-Month Follow-up among 223 Participants Who Were Seropositive at Baseline.

Panel A shows the proportion of participants who had an immune response 1 month after fractional-dose vaccination against yellow fever, according to the geometric mean titer of neutralizing antibodies at baseline. Panel B shows the geometric mean titer at 1-month follow-up according to the titer at baseline. In both panels, I bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Data regarding the geometric mean titer at 1-year follow-up are provided in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Among the participants who were seropositive at baseline, there was no significant between-group difference in the proportion of male participants and female participants who had an immune response at 1 month (P = 0.74). However, there was a significant difference among age groups, even after adjustment for the baseline titer subgroup (P<0.001); only 33% (95% CI, 20 to 50) of the participants who were at least 50 years of age had an immune response (Table 3).

Among the 209 participants who were seropositive at baseline and completed the 1-year follow-up, all (100%; 95% CI, 98 to 100) remained seropositive. There was no significant difference in the distribution of titers at follow-up according to age group at 1 month (P = 0.16) or at 1 year (P = 0.98). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the distribution of titers at follow-up according to sex at 1 month (P = 0.71) or 1 year (P = 0.68) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In our study, which was conducted during a mass vaccination campaign that used one fifth of the standard dose of the 17DD yellow fever vaccine, we found that detectable antibodies against the yellow fever virus had developed in 98% of the participants by 1 month after vaccination. Furthermore, 97% of the participants were seropositive at 1 year after receipt of the fractional dose. These rates suggest that the use of fractional-dose vaccination is a viable approach for providing immunity and thus containing yellow fever outbreaks. These findings are important, given the ongoing risk of outbreaks of yellow fever globally, as shown during the 2017–2018 outbreak in Brazil, in which more than 21 million doses of yellow fever vaccine were administered to control the epidemic near many large population centers.20

The proportion of participants who underwent seroconversion was similar to that seen among full-dose vaccine recipients, in whom more than 98% underwent seroconversion in other studies.2 Our results are also similar to those seen in other studies of fractional-dose vaccination against yellow fever, in which participants have received as little as one fifth to one tenth of the standard dose.8–11 The previously published studies were performed in well-controlled clinical trials involving healthy, mostly male adults. In contrast, our cohort included children (≥2 years of age) and adults of both sexes, and the vaccine was administered in a mass campaign setting. Given the campaign setting, it is notable that our results were similar to those in the controlled studies.

In 2003 in the DRC, yellow fever vaccine was introduced into the childhood vaccination program and is administered to children at the age of 9 months. In the 10 years before the initiation of our study, rates of vaccine coverage ranged from 50 to 70%.21 The routine use of yellow fever vaccine probably accounts for our finding that children 12 years of age or younger had a higher rate of baseline seropositivity than participants in the other age groups. Overall rates of seroconversion and immune response at 1 month did not vary significantly across age groups, except for participants who were 50 years of age or older; participants in this age group were less likely than those in other age groups to have an immune response to the vaccine if they had neutralizing antibodies at baseline.

However, we did see significant differences in follow-up geometric mean titers at 1 month and at 1 year according to age group among participants who were seronegative at baseline. Children who were under 13 years of age and who had been seronegative at baseline had a lower geometric mean titer at follow-up than participants who were 13 years of age or older, particularly at 1 year. This observation is consistent with data from several trials of yellow fever vaccines that indicated a lower immunologic response to vaccination among children than among adults.5 Initially after yellow fever vaccination, the geometric mean titer was lower among adults who were 50 years of age or older than among younger adults, a finding that has been observed for yellow fever vaccines and other vaccines.2,14,22 However, at 1 year after vaccination, the titers in the older age group were similar to those in younger adults, which suggests a different initial profile for antibody response but an overall good response to the fractional-dose vaccine.

Although we found a rate of seroconversion among female participants that was slightly but significantly lower than that among male participants, the geometric mean titers at both follow-up visits were similar. A slightly greater immunologic response to the vaccine among male participants has also been reported in trials in which the full-dose yellow fever vaccine was used,23–25 which suggests that the observed difference was not unique to the fractional dose.

It is unknown whether long-term antibody persistence will differ between fractional and full-dose administration of yellow fever vaccine. We found that almost all the participants who received the fractional dose in our investigation were seropositive for yellow fever neutralizing antibodies at 1 year after vaccination. Furthermore, recent data from de Menezes Martins et al.26 showed high rates of detectable antibodies 8 years after the administration of various fractional doses, and Roukens et al.27 found similarly high rates of detectable antibodies at 10 years after vaccination among participants who had received a one-fifth dose intradermally and among those who had received a full dose subcutaneously. These findings suggest that immunity to fractional doses will probably persist for years.

Our study has several limitations. We did not include a control group of participants who received a full dose of yellow fever vaccine because of technical and ethical issues, so we could not directly compare the immune response after the fractional dose with that after a full dose. Also, the use of PRNT50 titers may have caused incorrect classification of participants with low titers as being seropositive for neutralizing antibodies against the yellow fever virus when in fact the titer was due to cross-reactive antibodies. However, since serum samples were obtained from each participant both before vaccination and after vaccination, the specific response to the vaccine could still be assessed. We did not calibrate the yellow fever antibody titers using an international reference preparation, which makes it difficult to compare our titers with those obtained in other studies of fractional-dose vaccination.17 International standardization of testing results for yellow fever has only recently been recommended, so very few data have been generated. The use of PRNT titers was preferred for this study to allow for comparison with much of the published data. We did not collect safety data during this evaluation. However, the adverse-event monitoring systems that were in place for the campaign did not identify any acute signals of concern associated with fractional-dose vaccination.28 Enhanced surveillance and community-based pharmacovigilance both detected approximately 0.5 serious adverse events per 100,000 doses after the campaign,13,29 a rate that is similar to that after full-dose campaigns conducted in West Africa.30 Finally, we could not formally assess the effectiveness of the fractional dose with regard to preventing viral transmission during the outbreak, since the outbreak was waning at the time of the campaign. However, no new confirmed cases of yellow fever were detected in Kinshasa immediately after the campaign despite ongoing surveillance.

In conclusion, we found that the immunologic response to a fractional dose of the 17DD yellow fever vaccine was appropriate for a response to a yellow fever outbreak among children 2 years of age or older and among nonpregnant adults. Additional studies are needed to determine whether fractional-dose vaccination provides adequate seroprotection in children under the age of 2 years, in pregnant women, and in persons who are infected with the human immunodeficiency virus.12 In addition, future studies need to verify that similar results are obtained with other 17D-derived yellow fever vaccines (17D-204 and 17D-213) and in populations with differing exposures to flaviviruses. Finally, additional studies with longer-term follow-up are needed to understand whether persons who receive fractional doses of yellow fever vaccine need to be revaccinated in order to sustain immunity to yellow fever virus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We thank all the study participants and members of the campaign and study staff; staff members at Institut National de Recherche Biomedicale, the World Health Organization (WHO), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Agency for International Development, and Management Sciences for Health; Joachim Hombach and Sergio Yactayo of the WHO and Alan Barrett of the University of Texas Medical Branch for their technical support; Kathleen A. Wannemuehler of the CDC for statistical support; Jason Velez and Barbara W. Johnson for laboratory assistance at the CDC Arbovirus Diseases Laboratory; and the Ministry of Health of the Democratic Republic of Congo and the CDC Global Disease Detection Operations Center for their collaboration in implementing this study.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garske T, Van Kerkhove MD, Yactayo S, et al. Yellow fever in Africa: estimating the burden of disease and impact of mass vaccination from outbreak and serological data. PLoS Med 2014; 11(5): e1001638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staples JE, Monath TP, Gershman M, Barrett ADT. Yellow fever. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, Edwards KM, eds. Vaccines. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2018: 1181–267. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck AS, Barrett AD. Current status and future prospects of yellow fever vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2015; 14: 1479–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaccines and vaccination against yellow fever: WHO position paper — June 2013. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2013; 88: 269–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staples JE, Bocchini JA Jr, Rubin L, Fischer M. Yellow fever vaccine booster doses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64: 647–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Situation report: yellow fever, 28 October 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250661/1/yellowfeversitrep28Oct16-eng.pdf?ua=1). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Update on progress controlling yellow fever in Africa, 2004-2008. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2008; 83: 450–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martins RM, Maia Mde L, Farias RH, et al. 17DD yellow fever vaccine: a double blind, randomized clinical trial of immunogenicity and safety on a dose-response study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013; 9: 879–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campi-Azevedo AC, de Almeida Estevam P, Coelho-Dos-Reis JG, et al. Subdoses of 17DD yellow fever vaccine elicit equivalent virological/immunological kinetics timeline. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14: 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopes Ode S, Guimarães SS, de Carvalho R. Studies on yellow fever vaccine. III. Dose response in volunteers. J Biol Stand 1988; 16: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roukens AH, Gelinck LB, Visser LG. Intradermal vaccination to protect against yellow fever and influenza. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2012; 351: 159–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fractional dose yellow fever vaccine as a dose-sparing option for outbreak response: WHO Secretariat information paper. Geneva: World Health Organization, July 20, 2016. (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246236/1/WHO-YF-SAGE-16.1-eng.pdf?ua=1). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yellow fever mass vaccination campaign using fractional dose in Kinshasa, DRC. Geneva: World Health Organization, September 26, 2016. (http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2016/october/4_Yellow_fever_mass_vaccination_campaign_using_fractional_dose_in_Kinshasa.pdf?ua=1). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016; 65: 1–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fractional dosing of yellow fever vaccines: review of vaccine potency and stability information, available evidence, and evidence gaps. Presented at the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) meeting, Geneva, October 18–20, 2016 (http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2016/october/presentations_background_docs/en/index1.html). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Recommendations to assure the quality, safety and efficacy of live attenuated yellow fever vaccines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. (http://www.who.int/biologicals/YF_Recommendations_post_ECBS_FINAL_rev_12_Nov_2010.pdf ). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaty BJ, Calisher CH, Shope RE. Arboviruses. In: Lennette EH, Lennette DA, Lennette ET, eds. Diagnostic procedures for viral, rickettsial and chlamydial infections. 7th ed. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 1995: 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hombach J, Solomon T, Kurane I, Jacobson J, Wood D. Report on a WHO consultation on immunological endpoints for evaluation of new Japanese encephalitis vaccines, WHO, Geneva, 2-3 September, 2004. Vaccine 2005; 23: 5205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roehrig JT, Hombach J, Barrett AD. Guidelines for plaque-reduction neutralization testing of human antibodies to Dengue viruses. Viral Immunol 2008; 21: 123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epidemiological Update: Yellow Fever. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization, March 2018. (https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&category_slug=yellow-fever-2194&alias=44111-20-march-2018-yellow-fever-epidemiological-update-111&Itemid=270&lang=en). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Immunization, vaccines and biologicals: data, statistics and graphics — WHO/UNICEF Estimates of National Immunization Coverage (WUENIC). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. (http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/en/ ). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roukens AH, Soonawala D, Joosten SA, et al. Elderly subjects have a delayed antibody response and prolonged viraemia following yellow fever vaccination: a prospective controlled cohort study. PLoS One 2011; 6(12): e27753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niedrig M, Kürsteiner O, Herzog C, Sonnenberg K. Evaluation of an indirect immunofluorescence assay for detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies against yellow fever virus. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2008; 15: 177–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camacho LA, da Silva Freire M, da Luz Fernandes Leal M, et al. Immunogenicity of WHO-17D and Brazilian 17DD yellow fever vaccines: a randomized trial. Rev Saude Publica 2004; 38: 671–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monath TP, Nichols R, Archambault WT, et al. Comparative safety and immunogenicity of two yellow fever 17D vaccines (ARILVAX and YF-VAX) in a phase III multicenter, double-blind clinical trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2002; 66: 533–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Menezes Martins R, Maia MLS, de Lima SMB, et al. Duration of post-vaccination immunity to yellow fever in volunteers eight years after a dose-response study. Vaccine 2018; 36: 4112–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roukens AHE, van Halem K, de Visser AW, Visser LG. Long-term protection after fractional-dose yellow fever vaccination: follow-up study of a randomized, controlled, noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 761–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yellow fever vaccine: WHO position on the use of fractional doses — June 2017. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2017; 92: 345–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nzolo D, Engo Biongo A, Kuemmerle A, et al. Safety profile of fractional dosing of the 17DD yellow fever vaccine among males and females: experience of a community-based pharmacovigilance in Kinshasa, DR Congo. Vaccine 2018; 36: 6170–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breugelmans JG, Lewis RF, Agbenu E, et al. Adverse events following yellow fever preventive vaccination campaigns in eight African countries from 2007 to 2010. Vaccine 2013; 31: 1819–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.