Abstract

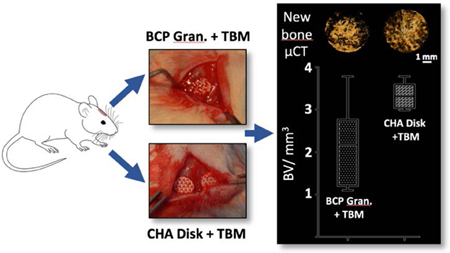

Finding alternative strategies for the regeneration of craniofacial bone defects (CSD), such as combining a synthetic ephemeral calcium phosphate (CaP) implant and/or active substances and cells, would contribute to solving this reconstructive roadblock. However, CaP’s architectural features (i.e., architecture and composition) still need to be tailored, and the use of processed stem cells and synthetic active substances (e.g., recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2) drastically limits the clinical application of such approaches. Focusing on solutions that are directly transposable to the clinical setting, biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP) and carbonated hydroxyapatite (CHA) 3D-printed disks with a triply periodic minimal structure (TPMS) were implanted in calvarial critical-sized defects (rat model) with or without addition of total bone marrow (TBM). Bone regeneration within the defect was evaluated, and the outcomes were compared to a standard-care procedure based on BCP granules soaked with TBM (positive control). After 7 weeks, de novo bone formation was significantly greater in the CHA disks + TBM group than in the positive controls (3.33 mm3 and 2.15 mm3, respectively, P=0.04). These encouraging results indicate that both CHA and TPMS architectures are potentially advantageous in the repair of CSDs and that this one-step procedure warrants further clinical investigation.

Keywords: Bone tissue engineering, Bioceramics, Calcium phosphates, 3D printing, Bone marrow, Calvaria

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The ability to repair large and critical-sized craniofacial bone defects (CSD) in both pediatric and adult populations today remains limited. The number of patients living with craniofacial osseous deficiencies will continue to grow because craniectomy remains the clinical care standard in treating the entire age range of patients with traumatic head injuries, stroke, and resection of tumors. Despite the well-known limitations associated with autologous bone graft (BG) transplantation (e.g., damaging a healthy bone, resorption, morbidity, infection), it remains the most preferred technique in repairing skull defects, especially in growing patients (where synthetic, nonvital implants are contraindicated) and compromised wound beds (poor soft tissue coverage, previous radiotherapy or infection)1–4.

To contribute to solving this reconstructive roadblock, the search for innovative solutions based on synthetic materials, serving as ephemeral scaffold for the growth of new bone, has been extensive. Synthetic calcium phosphate bone substitutes (BS) such as hydroxyapatite (HA), beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) and calcium phosphate cements (CPC) have demonstrated considerable potential for the regeneration of CSD given their biocompatibility and osteoconductive features5 but are often insufficient6. Experimentally, many attempts to enhance the regenerative capacity of BS to induce or augment cranial repair have been made with the addition of expended stem cells7, growth factors6, or cytokines, alone or in combination (i.e., tissue engineering strategies)8,9. While tissue engineering might have a bright future in the reconstructive field, significant drawbacks such as the lack of reliable efficacy, high costs, potential side effects of the synthetic bioactive substances (e.g., ectopic bone formation), potential safety risks (e.g., tumors) and ethical issues hinder its current implementation to clinical cases10,11. Safer alternatives to these processed stem cells and synthetic active substances, based on dispensable tissues that can be harvested from the patient in large quantities without causing significant harm (e.g., bone marrow, bone marrow cell extract) are already routinely clinically used with clear success 12.

Another way of improvement lies in the optimization of synthetic scaffolds to enhance the biological response. Indeed, both scaffold architecture and composition are known to modulate cell behavior directly and indirectly, and thus could significantly affect CSD repair once implanted: the success of the clinical procedure is mainly determined by the ability of the implant to keep endogenous and exogenous cells alive and functional. This requires the scaffold to have micron-scale pores and roughness (< 10 μm, ideally > 1 μm) for osteogenic cell adherence and bone formation, as well as a macroscopic porous network (> 100 μm) for cell colonization, mass transport and blood vessel guidance11. Triply-periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS) are a promising tool for designing the macroscale pore architecture of biomaterials13. These open periodic porous structures, which have zero mean curvature, show higher intrinsic features than conventional semi-random porous architectures (e.g., salt-leached scaffold), such as the surface-to-volume ratio and permeability, both playing a critical role in the conduction of chemical (e.g., nutrients) and biochemical (e.g., cytokines) species, cells and tissues14–16.

Ideally, scaffold biodegradation and bone formation should also occur concurrently at a matching rate. However, clinically used calcium phosphates, as pure phase (e.g., HA) or as biphasic calcium phosphates (BCP), displayed a limited in vivo degradation, i.e., low solubility (chemical property) and resorbability (from cellular activity). Ionic substitutions or insertion within the apatite lattice (e.g., carbonate, silicate) have been shown to modulate the biodegradation of the implant, coupled with a stimulation of bone and vascular ingrowth. Specifically, the interesting potential of carbonated hydroxyapatites (CHA) have been emphasized for years as their in vivo behavior, especially their biodegradation rate, can be tailored by the amount of carbonate ions present in both phosphate (B-type) and hydroxide (A-type) sites of their lattice 17–21.

Designing and producing implants with a controlled composition and architecture, tailored to the craniofacial defect to repair, is now possible with the development of additive manufacturing technologies and associated software14,22–24. Authors proposed a flexible manufacturing process based on the impregnation of wax molds, produced by additive manufacturing, to produce CaP bioceramics of various compositions for such bone applications25,26.

The study reported herein investigates the regeneration of calvarial rat CSDs and compared CSD repair when filled with BCP granules (as the reference material) and custom-made BCP and CHA disks, with or without addition of total bone marrow aspirate (TBM). BCP and CHA disks were designed with a TPMS produced through an indirect, flexible and reliable additive manufacturing process. This will indicate the potential of this architecture and composition for the regeneration of craniofacial CSD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. MBCP granules

MBCP® ceramic granules measuring 0.5–1.0 mm in diameter were provided by Biomatlante SA (Vigneux-de-Bretagne, France). They were defined as micro-macroporous biphasic calcium phosphate composed of 58% hydroxyapatite (HA) and 42% β tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), exhibiting a specific surface area (SSA) of 2.5 m2/g27. The total porosity volume has been evaluated between 70 and 75% and consists mainly of macropores (≈ 30% v/v) and micropores (≈ 70% v/v) ranging from 100 μm to 500 μm and 0.1 μm to 1 μm, respectively27,28. Tubes containing granules (0.015 g each) were double-packed and autoclave-sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min.

2.2. Tailored TPMS CaP disks

2.2.1. Powder preparation

HA, apatitic tricalcium phosphate (TCPap) and B-type carbonated hydroxyapatite (CHA) powders were synthesized by a conventional aqueous precipitation method using a fully automated synthesis station29–31. Briefly, a diammonium hydrogen phosphate solution ((NH4)2HPO4, 99%, Merck, Germany, [P]=1.2 mol/L), mixed, if applicable, with an ammonium hydrogen carbonate solution ((NH4)HCO3, 99%, Merck, Germany, [C]=0.1 mol/L) was added at 100 mL/min to a calcium nitrate solution (Ca(NO3)2, 4H2O, 99%, Merck, Germany, [Ca]=2.1 mol/L), maintained under stirring (500 rpm). Reagent ratios were calculated according to the following theoretical formula: Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, Ca9(HPO4)(PO4)5(OH) and Ca10-x(PO4)6-x(CO3)x(OH)2-x with x=0.8 for HA, TCPap and CHA powders, respectively. The pH of the suspensions was adjusted to 7.0 (TCPap) or 8.0 (HA and CHA) by the addition of 28% ammonia solution (Merck, Germany) by means of a dosing pump (ProMinent, UK) coupled with a pH controller (Mettler Toledo M400, USA) and a pH-electrode (Mettler Toledo Inpro®4800/120/PT100, USA). The temperature was controlled and regulated automatically at 35 °C (TCPap) or 65 °C (HA and CHA) with an external T-probe connected to a cryothermostat (Huber, Germany). An argon flow (Air Products, 0.1 L/min) was maintained in the reactors to prevent any atmospheric uncontrolled carbonation throughout the synthesis process. After complete introduction of the phosphate solution, the suspension was matured for 20 ± 2 h and finally centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min (ThermoFisher Scientific, Sorvall™ Legend XF). The wet powder agglomerates obtained were dried at 80 °C for 24 h, then ground in absolute ethanol (H3CCH2OH,>99.5%, VWR, Germany) by means of a planetary ball mill (PM400, Retsch, Germany) with zirconium oxide jars and balls and finally sieved at 25 μm (Russelfinex, Belgium).

Lastly, HA, TCPap and CHA powders were heat-treated to reduce their surface area as well as to transform TCPap into β-TCP according to the following general reaction:

TCPap and HA powders were thus heat-treated at 900 °C and 1000 °C for 2 h under air (ramps 4 °C/min, Nabertherm, Germany), and CHA powder at 900 °C for 5 h under CO2 (PCO2 = 1 atm, ramps 5 °C/min, Nabertherm, Germany). The SSA of 4.8 ± 0.1 m2/g, 4.3 ± 0.2 m2/g and 4.7 ± 0.1 m2/g, respectively, were finally achieved. These values were determined on powders, outgassed at 200 °C for 8 h, by means of the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) 5-point method using N2 adsorption isotherms (Micromeritics ASAP 2010, Germany).

2.2.2. Manufacturing process

Macroporous disk-shaped bioceramic implants were produced by a method detailed elsewhere based on the impregnation of wax molds26, the latter being built layer by layer with a drop-on-demand 3D-printer (3Z Studio, Solidscape, Multistation, Dinard). The molds were designed as the negative structure of the intended implant and printed with a layer thickness of 25 μm. Once printed and cleaned, molds were impregnated with a ceramic powder suspension (hereafter called slurry). After drying overnight at room temperature, the green bodies were cleaned of all excess dried slurry using a surgical blade (Swann-Morton, UK). Then they were heat-treated in a debinding furnace (Carbolite, UK) up to 500 °C, to eliminate the wax mold and the organic adjuvants, and finally sintered either at 1100 °C for 2 h under air (ramps 4 °C/min) or at 1050 °C for 2 h under CO2 (PCO2 = 1 atm, ramps 5 °C/min) to obtain the biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP: 60% HA and 40% β-TCP (w/w)) or the CHA bioceramics, respectively.

Slurries were prepared by blending 71.7% (w/w) powder (CHA) or powder blend (BCP: 60% HA and 40% β-TCP (w/w)), 27.7% (w/w) pure water, and 0.6% (w/w) dispersing agent (polyacrylate ammonium, Solvay, France) for 10 min at 170 rpm in a zirconia jar with zirconia balls 10 and 5 mm in diameter (PM400, Retsch, Germany). Before mold impregnation, an organic binder (1.9% (w/w), Duramax B-1000, Rohmand Haas, France) was mixed into the slurries at 140 rpm for 15 min using a propeller stirrer.

Macroporous disks were sterilized at 180 °C in a poupinel dry heat sterilizer for 30 min.

2.2.3. Design of the macroporous bioceramic disk implants

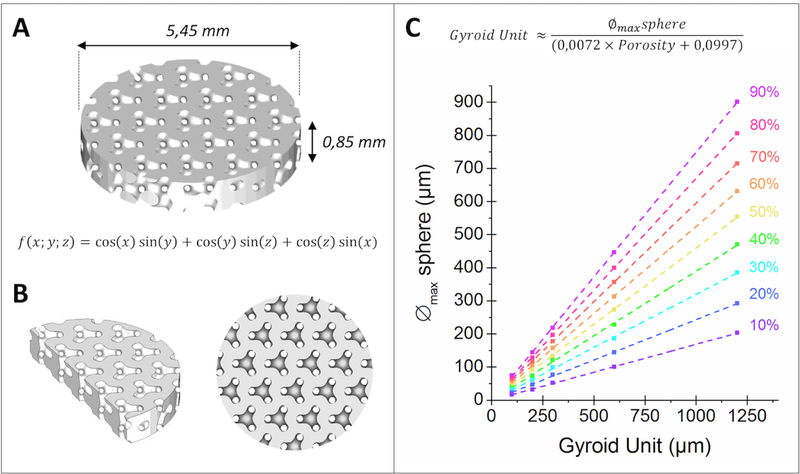

Implants were designed to perfectly match the geometry of a rat calvarial defect 5.5 mm in diameter (Figure 1) using ScanIP software (Simpleware, UK). The thickness of the implant was chosen not to exceed the height of the rat parietal bone ≈ 1 mm (Figure 2A). As regards its computer-aided design (CAD) model, the intended bioceramics should display a gyroid structure wherein a 300 μm sphere could freely move, for a total macroporosity of 40% (Figure 2B). For informative purposes, Figure 2C also illustrates the link between the maximum size of a sphere that can go through a gyroid structure and the dimension of its fundamental unit for different porosity rates. The largest macropores of the gyroid architecture were purposely orientated along the height of the bioceramic, i.e., to face the animals’ brain.

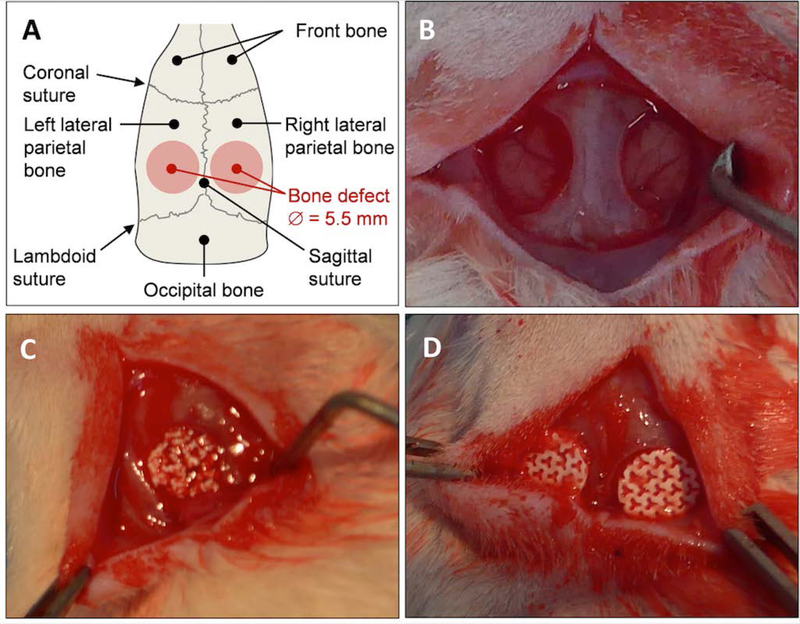

Figure 1. Calvarial bone defect in rat model.

(A) Diagram and (B) picture showing the two critical-size calvarial defects performed on the left and right parietal bone of inbred Lewis rat (5.5 mm in diameter). Pictures showing the defects filled with (C) BCP granules and (D) macroporous disk-shaped bioceramics.

Figure 2. Design of the macroporous bioceramic disk.

3D images derived from Simpleware CAD software of (A) the macroporous disk with a 40% porosity volume, (B) cross section and top views of a 40% gyroid structure wherein a sphere 300 μm in diameter can move freely and (C) the changes in the maximum diameter of a sphere that can go through the entire gyroid structure depending on the size of the gyroid’s fundamental unit and its porosity.

As previously stated, molds were designed as the negative of the intended bioceramics with ScanIP software (Simpleware, UK). To obtain analogous bioceramics after sintering, independently of the ceramic phase, the dimensions of the molds and the parameters of the gyroid structure were adjusted: a shrinkage of 9.7% and 6.0% were considered for the BCP and CHA phases, respectively.

2.2.4. Characterization of the macroporous bioceramic disk implants

The crystalline phases of the samples were identified by means of a Bruker D8 Advance θ/θ X-ray diffractometer (XRD) with a Lynx-Eye XE-T Detector (with a 2.93° aperture angle), using CuKα radiation and operating at 40 kV and 20 mA. XRD patterns were collected over the 2θ range of 10–120° at a step size of 0.01° and counting time of 0.2 s per step. The crystalline phases were identified with Bruker Diffrac.EVA 4.0 software (Bruker AXS, Germany) and the PDF04+ database 32. Rietveld method refinement was achieved with DIFFRAC.TOPAS v.5.0 software (Bruker AXS, Germany) using the Pawley algorithm and the following fundamental parameters for HA and β-TCP structures: PDF_00–009-0432, space group P63/m (176) and PDF_00–009-0169, space group R 3c (167), respectively. The XRD patterns were also used to determine the HA/β-TCP phase ratio of the BCP bioceramics according to a standard procedure33.

Ground bioceramics were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy using a Bruker VERTEX 70 spectrometer (Bruker Optics, France), equipped with a monolithic diamond ATR crystal (Quest ATR diamond, Specac, USA). The spectra, obtained by signal averaging of 64 successive scans, were recorded from 4000 to 400 cm−1 at a resolution of 2 cm−1. A curve-fitting analysis in the ν2 (900–840 cm−1) and ν3 (1600–1300 cm−1) carbonate domains of the FTIR spectra (dedicated in-house method34) was performed by means of OriginPro 2018b software (OriginLab, USA). Carbon content in CHA bioceramics was also determined by an elemental analyzer, using an infrared detector (LECO CS-444, USA).

Morphometric analyses of the bioceramics produced were carried out at various scales. Each bioceramic was first imaged using a Nanotom S X-ray computed tomography system (Phoenix, AZ, USA) with a voltage of 80 kV (tungsten target), an integration time of 750 ms and a 3.5-mm voxel resolution. For reconstruction of the volume data, a proprietary implementation based on the Feldkamps cone beam-reconstruction algorithm was used. VG Studio software (Volume Graphics, Heidelberg, Germany) was used for the 3D visualization of the volume data and the data set export in .DICOM format for image analysis.

Once imported into Simpleware, the .DICOM images allowed for the reconstruction of a 3D model of the bioceramic, which was exported in .stl format. After manual gross superimposition of the bioceramic model with its original CAD design, .stl files were imported in CloudCompare freeware (EDF R&D, France) for further comparison. A dedicated algorithm allowed for the fine superimposition of the two models. The “cloud to mesh” algorithm was used to compare the 3D printed bioceramic to its CAD model, the latter serving as the reference.

The ceramics were also examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM-6500F, USA) by applying a gold coating (about 10 nm) using the sputtering technique (Quorum, Q150R ES, UK). The porosity at the samples’ surface was quantified from SEM images using ImageJ freeware (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Additionally, the minimum (xF,min) and maximum (xF,max) Feret diameter of the micropores, as well as three morphological factors, aspect ratio (A.R.) sphericity (S) and roundness (R.), were evaluated (N = 3 SEM image analyzed per sample _ N = 2 samples per macroporous bioceramic) 26,35.

Finally, the ceramics SSA was determined as described previously using the BET 5-point method (five ceramics/ triplicate measurements).

2.3. Animals

Twenty-four adult inbred Lewis 1A-haploype RT1a rats were obtained from a certified breeding center (Janvier Labs, LeGenest-Saint-Isle, France) and acclimatized for 2 weeks to the conditions of the local vivarium. Animal experiments were conducted according to the European directive 2010/63/EU and were approved by the French Ministry of Research and Education (APAFIS 18616-V1) and by the Pays de la Loire Ethics Committee (France).

2.4. Bone marrow harvesting

Three rats were specifically designated as TBM donors. The animals were anesthetized using inhaled isoflurane (Forene; Abott, Rungis, France) and sacrificed via intracardiac overdose of sodium thiopental (Nesdonal; Rhône-Merieux, Lyon, France). TBM was isolated from femurs, humeri and tibias for extemporaneous grafting. Briefly, the ends of each bone were cut, and 1 mL of TBM mixed with saline was obtained through an intramedullary bone flush procedure performed with a 26-gauge needle. After pooling, the TBM was seeded into the CaP biomaterial, which was immediately implanted in the calvarial defect.

2.5. Implant preparation and study groups

The animals were randomly assigned to one of the following groups: BCP granules; BCP granules +TBM; BCP disk; BCP disk +TBM; CHA disk; CHA disk +TBM and Empty defect. Empty defect and BCP granules + TBM were used as a negative and positive control, respectively. Study was performed on N = 6 animals per group.

2.6. Surgery

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia and lasted 20 min. After local subcutaneous xylocaine injection (0.1 mL, 0.1%), a 2 cm longitudinal incision was made on the head of each rat from the forehead to the neck. Skin and periosteum were lifted. Subsequently, critical-sized parietal defects (5.5 mm) were created bilaterally using a circular trephine (Komet Medical, Lemgo, Germany) under saline solution infusion. Each animal received two randomly assigned implants (N = 6) as detailed in Table S1. The skin was then closed with nonabsorbable sutures (Ethylon 5.0, Ethicon©). Immediate postoperative analgesia was provided through subcutaneous injection of buprenorphine hydrochloride (Buprecare; Animalcare, Dunnington, UK) and maintained for 2 days. Seven weeks after implantation, the animals were sacrificed by sodium thiopental overdose.

2.7. Microcomputed tomography analysis

Qualitative analysis of total mineral and newly formed bone contents was performed at the time of necropsy using the SkyScan-1272 high-resolution 3D X-ray micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) system for small-sample imaging (Brucker, Belgium). The scanner was equipped with a 20- to 100 kV (10 W) X-ray source and an 11-mega-pixel X-ray detector. Each sample was placed on a holder with the sagittal suture oriented parallel to the X-ray detector and scanned using a 0.5-mm aluminum filter, 18-μm isotropic voxels, a 0.71 °rotation step, and frame averaging of 4. For 3D reconstruction (NRecon software, Bruker) without smoothing, a ring artifact correction beam hardening correction wand the absorption coefficient was set to 4, 20%, and from 0.005 to 0.1. Standard 3D morphometric parameters (CTAn software, Bruker) were determined in the region of interest (5.5 mm circle; 100 cuts) and put on the defect. Representative 3D images were created using CTvox software (Bruker) for each implant to assess bone formation in control and treated animals. The overall augmented contour was evaluated in the 3D reconstructed view and calculated in CTan. Boundaries were set to standardize the region of the augmented volume to be analyzed. Bone volume (BV; mm3) was calculated as the volume occupied by bone within the region of interest.

2.8. Histology

To observe the newly formed bone and osteoblastic cells, double staining was performed. In short, specimens were fixed for 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde and then dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol treatments. Nondecalcified bone specimens were infiltrated and embedded in glycol-methyl-methacrylate (GMMA; Technovit 9100, Kulzer, Germany). For each sample, a craniocaudal section was performed at the maximum diameter of each implant using a circular diamond saw (SP1600; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and serial 5-μm sections were cut using a hard tissue microtome (Polycut SM 2500; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The sections were stained with Goldner’s trichrome and hematoxylin-eosin-safran and then examined using a light microscope (Leica-DM 4000 B, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.9. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed to evaluate the vessel formation in biomaterials and the empty defect. Sections measuring 5 μm were cut from GMMA-embedded blocks and then stained. A rabbit polyclonal anti-CD 31 antibody (Abcam 28364, dilution 1:100) was used for endothelial staining and vessel visualization. A negative control was performed without primary antibody CD31. Quantitative analysis of the vessel formation was performed by a pathologist using a light microscope (Leica-DM 4000 B, Wetzlar, Germany): the vessel count was performed for each reconstruction including 10 fields per defect with a ×40 magnification.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Each result was expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of six samples. A one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc test (Fisher’s protected least significant difference) was performed. P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the macroporous disk-shaped bioceramics

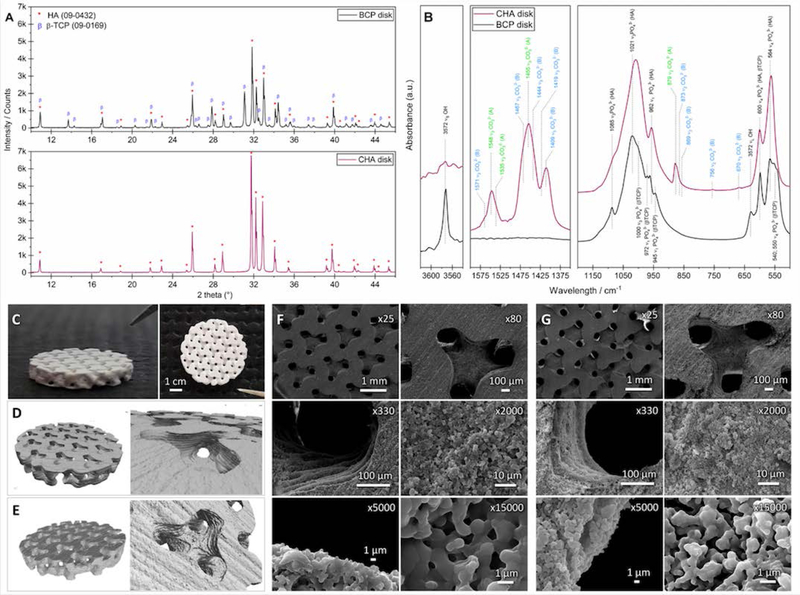

Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns and FTIR spectra of BCP and CHA ground bioceramics, centered on the range 10≥2θ≥46 °, and 3620≥ν≥3540 cm−1, 1600≥ν≥1350 cm−1 and 1200≥ν≥500 cm−1., as well as images of the macroporous disk-shaped bioceramics.

Figure 3. Characteristics of macroporous bioceramics.

(A) XRD patterns and (B) IR spectra of the BCP and CHA ground scaffolds assessing the scaffold composition. “CO32− (B)” and “CO32− (A)” correspond to vibrations of carbonate ions in the positions occupied by phosphate and hydroxide ions in the HA lattice, respectively. (C) Pictures, and 3D images of the (D) BCP and (E) CHA bioceramics obtained by X-ray μ-tomography. SEM micrographs showing the macro- and micro-architecture of (F) BCP and (G) CHA bioceramics including 300 μm macropores and submicron micropores.

Both the diffractogram (Figure 3A) and the FTIR spectrum (Figure 3B) of the BCP sample exhibited the characteristic diffraction lines or bands of HA and β-TCP phases (PDF 00–009-432 and 00–009-169, respectively)36. No other crystalline or amorphous phase was detected. The a and c lattice parameters of the HA (a=9.422 Å and c=6.882 Å) and β-TCP (a=10.437 Å and c=37.426 Å) phases detected in the BCP sample are equivalent to values reported in the ICDD PDF cards 00–009-432 (a=9.418 Å and c=6.884 Å) and 00–009-169 (a=10.429 Å and c=37.380 Å), respectively. Moreover, the percent by mass of crystalline phases HA and β-TCP in BCP implants was assessed at 55.9 ± 0.2% and 44.1 ± 0.2%, respectively.

The XRD pattern of the CHA implant (Figure 3A) is typical of a hydroxyapatite structure (PDF 00–009-432). Lattice parameters a and c are equal to 9.455 Å and 6.890 Å, respectively. Both are significantly higher than those of HA (ICDD PDF cards 00–009-432), as is commonly observed when carbonate ions simultaneously substitute for phosphate (B-sites of the apatite structure) and hydroxide (A-sites of the apatite structure) ions in the HA lattice37,38.

The infrared spectrum exhibits only the characteristic bands of AB-type carbonated hydroxyapatites (Figure 3B)31,39, confirming that the chemical composition of CHA implants can be illustrated with the following general formula:

| Eq. 1 |

with 0 ≤ x (B-type carbonate ions) ≤ 2 and 0 ≤ z (A-type carbonate ions) ≤ 2-x

The carbonate content of the CHA implants was evaluated at 5.48±0.05% w/w. The amounts of A-type and B-type carbonate ions, investigated by a curve-fitting method, were evaluated at 0.78±0.19% w/w and 4.70±0.23% w/w, respectively.

Figures 3C–3E show pictures and X-ray μ-tomography 3D images of the BCP and CHA macroporous disk-shaped bioceramics. Their final dimensions are equivalent and were assessed at ⊘ = 5.44±0.04 mm and h = 827±41 μm (n=24), and at ⊘ = 5.44±0.05 mm and h = 843±38 μm (n=18), respectively. Moreover, the CloudCompare comparison revealed that both BCP and CHA bioceramics were very similar to their initial CAD model with a distribution of the deviation centered on 0 μm, with most of the deviations between −40 and +40 μm (Figure S1).

The SEM images of the BCP and CHA bioceramics macro- to micro-structures (Fig. 3F and 3G) clearly reveal the printing orientation of the mold parallel to the surface of the disks as well as submicropores. As described in Table 1, the concentration of submicropores at the surface of the BCP and CHA bioceramics is about 10% and 14%, respectively. This small difference in concentration generates a difference less than 1 m2/g between the two types of macroporous disks (see Table 1). The size (xF,min ≈ 0.7 μm and xF,max ≈ 1.3 μm) and morphology of the submicropores are similar: the latter can be defined as domino-shaped micropores subrounded with a low sphericity.

Table 1.

Microporosity of macroporous disk-shaped bioceramics.

| Sample | BCP | CHA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | SD | Average | SD | |

| Amount s/s | 9.9% | 2.2% | 13.6% | 2.7% |

| xFmin / μm | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| xFmax / μm | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| AR | 2.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| R | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| S | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| SSA / m2g−1 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 2.3 | 0.2 |

Amount (surface/surface), dimension and morphology of the micropores constituting BCP and CHA macroporous ceramics from SEM image analysis and SSA values; AR (aspect ratio), R (roundness), S (sphericity), xF,min and xF,max corresponding to the shortest and longest Feret diameter, respectively; SD standard deviation.

3.2. Clinical findings

All animals survived the surgical procedure, 36 defects were healed with biomaterials and six were left empty. During the healing period, no reconstruction exposure or loss was observed, and no abnormal findings such as inflammation, infection or separation in the surgical wound were observed.

3.3. Micro-CT findings

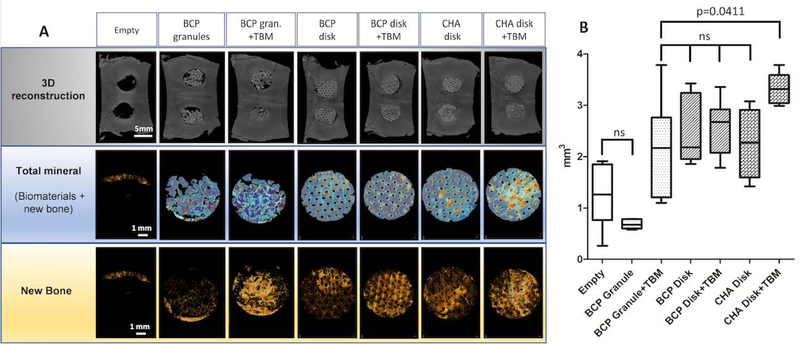

As shown in micro-CT images after sacrifice at 7 weeks (Figure 4A), the groups with the BCP and CHA disk presented homogeneous bone formation distributed over the entire surface of the bone defect, conversely to the groups with granules, which systematically presented a partial filling of the defect. The amount of bone was grown toward the center of the defect from adjacent host tissues in all groups (disks and granules with or without TBM).

Figure 4. Micro-CT analysis of the critical-sized craniofacial bone defect (CSD) reconstruction.

(A) Images of the CSD reconstructions at 7 weeks showing calvarial 3D reconstruction, biomaterials + new bone as well as newly formed bone alone. CSD repair with BCP granules ± TBM systemically had biomaterial loss and calvarial holes. (B) Graph showing the quantitative analysis of bone volume (BV, mm3) in the region of interest. Empty defect (negative control) and BCP Granule groups had the lowest rate of bone formation compared to others (p<0.05). There was no statistical difference between BCP granule+TBM (positive control) and macroporous disks alone while the CHA+TBM group had significantly higher bone formation than BCP granule+TBM (p=0.0441).

The BCP granules and Empty defect groups had the lowest rate of newly formed bone (see Table 2 and Figure 4B), which were significantly lower than for the BCP and CHA disk groups (p=0.03 and p=0.04, respectively). Addition of TBM prior to implantation systemically improved bone formation, independently of the bone substitute (e.g., 103% increase for Granule + TBM). Interestingly, bone content was comparable in the positive control (Granule + TBM) BCP and CHA disk groups without TBM. The greatest bone healing was observed in the CHA+TBM group, with approximately 55% more bone formed than in the positive control (Table 2, p=0.04). While not significant, the CHA disk + TBM group also showed greater bone formation than the BCP disk + TBM group, the latter displaying results comparable to the Granule + TBM group.

Table 2:

Bone volumetric analysis within the region of interest (n = 6; mm3).

| Group | Mean ± SD | Median |

|---|---|---|

| Empty | 1.242 ± 0.610 | 1.263b,d |

| BCP Granule | 1.055 ± 0.906 | 0.726b,d |

| BCP Granule +TBM | 2.146 ± 0.975 | 2.169a,c,d |

| BCP disk | 2.515 ± 0.686 | 2.183a,c |

| BCP disk+TBM | 2.572 ± 0.543 | 2.674a,c |

| CHA disk | 2.258 ± 0.653 | 2.271a,c |

| CHA disk+TBM | 3.331 ± 0.303 | 3.315a,b,c |

Significant difference compared to negative control group (empty defect)*.

Significant difference compared to positive control group (BCP Granule+TBM)*.

Significant difference compared to BCP Granule group*.

Significant difference compared to CHA disk+TBM group*.

p < 0.05

Table showing the mean±SD and the median of the bone volume in CSD. Bone formation was significantly lower in the empty (negative control) and BCP Granule groups. No statistical difference was observed between BCP Granule+TBM (positive control) vs Macroporous disks (BCP and CHA) without TBM. CHA+TBM showed a higher rate of bone formation than BCP Granule+TBM (p<0.0441).

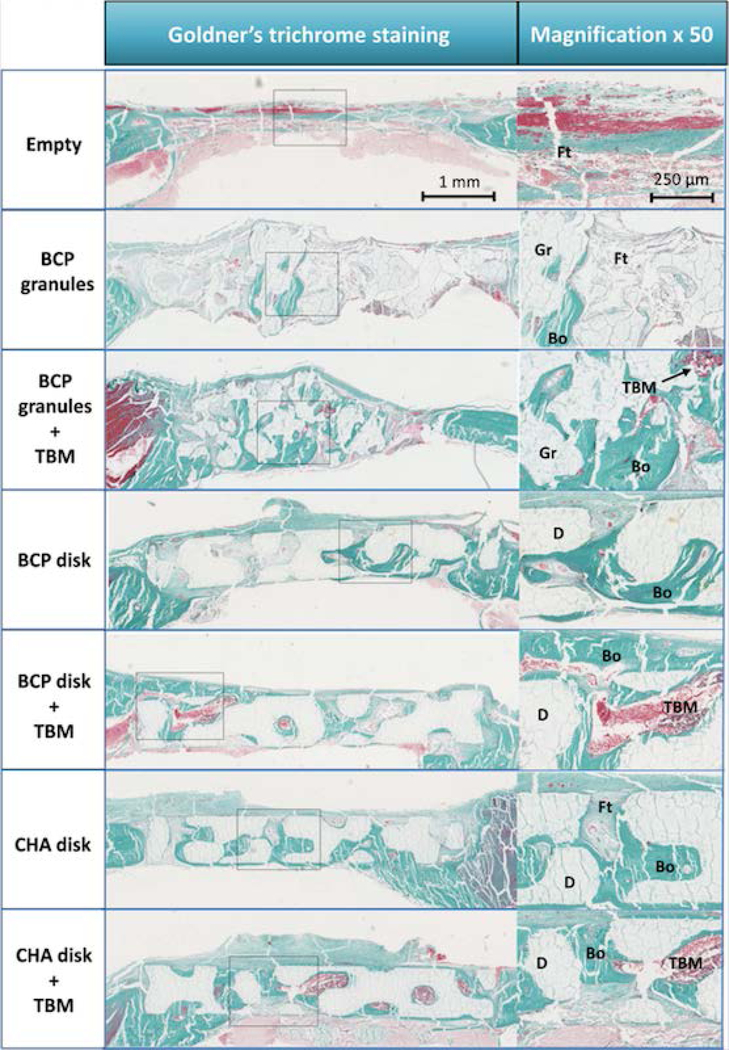

3.4. Histologic findings

Goldner’s Masson trichrome staining is detailed in Figure 5 and confirmed the previous observation on bone regeneration (Figure S2). Notably, abundant bone formation was observed in disk ± TBM groups, regardless of the disk composition, and the BCP granules + TBM groups.

Figure 5. IHC of calvarial reconstruction using Goldner’s Trichome staining.

Images showing the histological assessment at 7 weeks of CSD reconstruction with a magnification (×50) of a corresponding new bone formation area. The calvarial reconstructions using custom-made macroporous disks evenly restored the cranial vault compared to groups reconstructed by BCP granules. In groups using CaP biomaterials without TBM, more newly formed bone was observed in groups reconstructed by macroporous disks than by BCP granules. Live TBM cells were systematically observed in groups reconstructed by CaP biomaterials+TBM. A large amount of new bone was observed when biomaterials were combined with TBM. Abbreviations: new bone, Bo; BCP granule, Gr; macroporous disk, D; total bone marrow, TBM; fibrous tissues, Ft.

The defect was mainly filled by fibrous tissue in both the BCP granules and Empty groups. A small amount of bone was observed, mainly close to the adjacent host bone. Uneven vault reconstruction was observed in the BCP Granule group.

In the BCP granules + TBM group, a large amount of bone was observed around the granules close to the adjacent host bone as well as in the center of the defect (especially in zones in contact with the dura). Although the distribution of granules was more homogeneous with TBM, the calvarial vault was nevertheless poorly and unevenly repaired (e.g., random thickness).

In the BCP and CHA disk groups, bone formation occurred from the defect edges to its center. Spicules penetrating the porous structure of the implant and merging in large bone islands were observed. A homogeneous distribution of a large amount of new bone was detected within the scaffolds in groups combining CaP disks, regardless of their composition, and TBM, with the center of the defect widely colonized by newly mineralized tissue (6/6 of CHA and 4/6 of BCP respectively).

Generally, anatomical calvarial vault reconstruction was carried out successfully in defects filled with macroporous disks, in contrast to the BCP granules groups. Bone marrow niches were created in groups including TBM with larger niches when custom-made disk-shaped CaP bioceramics were used.

Goldner staining was compared to HES staining (Figure S3) to evaluate bone maturity and the osteoid band in the samples. No difference was observed between BCP granules and macroporous disks, which for the most part had mature bone at 7 weeks.

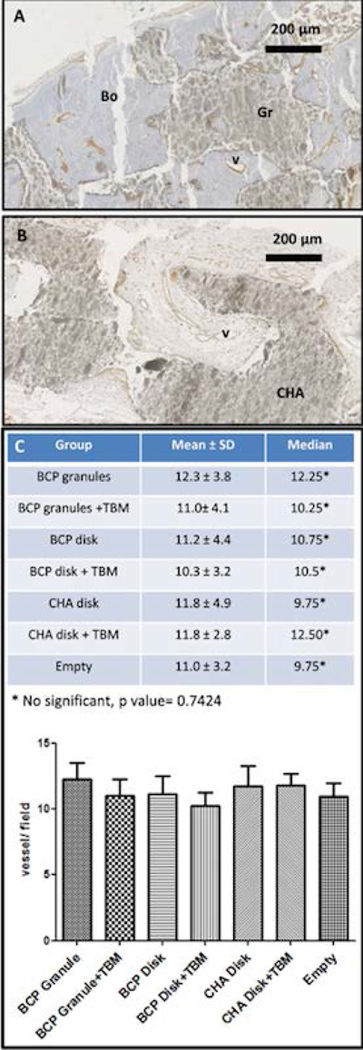

2.5. Immunohistological findings

Vessel formation was observed from the edge of the craniectomy, in surrounding fibrous tissue and into the scaffolds for all groups. The vessel arrangement showed a high fibrovascular network growing into the macroporous network of the disks or around the BCP granules. No difference in the number of vessels (about 10 per field, magnification ×40) or vessel size was observed (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Assessment of angiogenesis in craniofacial bone defect (CSD) reconstruction.

IHC images showing vessel formation in calvarial reconstruction with (A) BCP granules or (B) CHA macroporous bioceramic using endothelial cell immunostaining with anti-CD 31 antibody. (C) Graph and table of the vessel quantification (vessel count of 10 fields per CSD, magnification ×40) showing no significant difference between experimental groups. Abbreviations: Bo, new bone; v, vessel; Gr, granules; CHA, CHA macroporous bioceramic.

4. Discussion

In this study, we aimed to compare one-step and single reconstruction procedures including two types of customized CaP macroporous bioceramics with or without TBM on a rat model.

The design of the macroporous disk-shaped bioceramics was optimized to facilitate handling by the surgeon and to enhance their osteoconduction and osseointegration compared to a pile of granules. For this purpose, the porosity was set at 40% to prevent erosion of ceramics while avoiding sintering at an excessively high temperature, which in turn would reduce concentration in micropores. The size of the disks was proved to fit the bone defect volume closely with less than 60 μm of space between the ceramic, centered in the defect, and the parietal bone. A gyroid macroporous structure was accurately patterned in the bioceramics to improve their permeability compared to a standard random macroscopic porous network14. A 300 μm macropore size was specifically chosen to create sufficient confined areas to positively affect tissue growth and blood vessel guidance11. Controlling the microporosity of the implants at the submicron scale was also intended to improve their overall osseointegration dynamics11,27. _As the microporosity and surface microtopography of the CaP-based implants can be controlled by adjusting the manufacturing parameters26,40 , further studies could be performed to determine the relative effect of both the micro- and macro-architectural features on cell fate41.

The BCP macroporous disk-shaped bioceramics are composed of HA (56% w/w) and β-TCP (44% w/w) phases in equal proportion to that of the MBCP® granules (58%HA, 42% β-TCP w/w). Assuming Eq. 1 and the amounts of A-type and B-type carbonate ions in the HA lattice, CHA bioceramics is a monophasic AB-type carbonated hydroxyapatite that can be described by the following chemical formula:

| Eq.2 |

In our experimental conditions, we considered BCP granules extemporaneously mixed with TBM as a positive control of bone regeneration as previously described 42–45. Indeed, its efficacy in an animal model has been documented in several studies. BCP granules have well-known osteoconductive properties repeatedly described for decades5, and TBM naturally contains a large number of chemotactic and osteogenic factors as well mesenchymal and hematopoietic progenitor cells promoting bone formation. We previously showed that the mixtures of BCP granules and unprocessed TBM had osteogenic potential in vivo and a positive effect on bone ingrowth44,45. In addition, other studies confirmed enhancement of induced bone formation in ectopic and osseous sites 46–48. Thus, we aimed to compare BCP granules + TBM to custom-made disk-shaped bioceramics consisting of a macroporous gyroid structure.

We tested a clinically relevant single-step procedure with no preoperative in vitro procedure such as osteogenic cell isolation. Seven experimental procedures were performed including the negative (defect maintained empty) and positive (BCP granules + TBM) controls.

Comparison of the new bone volume formed in BCP granules and CaP disks demonstrated the importance of the macroscopic shape and porous network of the implant on its osteoconductive properties. Thus, BCP granules had the same rate of new bone as the empty defect while BCP disks without any addition of TBM presented a higher bone volume than BCP granules. In addition, CaP disks without TBM displayed a bone formation equivalent to the positive control (see Figures 4 and 5, and table 2). This indicates that randomly arranged granules impeded spontaneous regeneration of the bone (vault reconstruction) while the gyroid structure guided it.

Osseointegration (i.e., fusion between the defect rim and the scaffold) and bone apposition (i.e., continuum of the mineral between bone and scaffold) were enhanced by the architecture of the 3D-printed bioceramics, whose shape perfectly matched the defect, thus allowing for an intimate bone-scaffold contact and whose internal macroporous gyroid structure provides an ideal environment for cell colonization, survival and physiological metabolism. For instance, the permeability of the gyroid structure is more than 10-fold greater than those with random pore architecture of comparable porosity and pore size14, favoring mass transport (e.g., cells, nutrients, waste removal). Please refer to the review of Kapfer et al.49 for more details on the potential of TPMS structure for biological applications. In addition, the micro-motion of the disks due to the dura pulsation (nonideal conditions for bone recovery) is very limited in contrast to the BCP granules.

Interestingly, the synergistic effects of both scaffold composition and architecture were discovered in this study: although bone formation within BCP and CHA disks was comparable, it became significantly higher in the CHA + TBM group. While further investigations will be required to precisely understand the underlying mechanisms driving this phenomenon, this indicates that a concomitant modulation of the physicochemical and architectural features of the implant may improve the survival and metabolic activity of endogenous and exogenous cells, thus unveiling new opportunities for the regeneration of the craniofacial bone defect.

Although CaP disks alone are as effective as the positive control, the combination of AB-type CHA disk with TBM aspirate, which contribute essential chemotactic and osteogenic factors, was the most efficient procedure in this study. In addition, this combination allowed an even reconstruction of the cranial vault with bridging of the bone defect in contrast to the positive control using BCP granules (see Figure S2), emphasizing the highest potential of tailored TPMS CHA bioceramics than BCP granules, with or without TBM aspirate, for clinical applications.

To completely avoid autologous harvest, we could use other adjuvants promoting bone formation such as rhBMP-2 that have shown promising results when compared to autologous bone graft for the craniofacial area50,51. However, rhBMP2 procedures are expansive and can have potentially severe side effects. rhBMP-2 exposes the patient to the risk of wound complication such as breakdown, infection or significant local swelling with potential acute respiratory failure when it is used too close to the airways52,53. Additionally, bone formation around the bone defect (e.g., ectopic ossification) is commonly described with BTE procedures using BMP10,54. This limits the added value of a custom-made implant except to replace the loading method by soaking BMP-2 in the carrier, leading to the burst-release of a supraphysiological dose of BMP-2 (e.g., several milligrams), by the grafting of BMP-2 molecules at specific sites at the CaP ceramic surface55.

Materials should also enable vascular network formation for bone regeneration56–58. Scaffold porosity is a decisive factor for tissue permeation, angiogenesis and oxygen diffusion into the materials, which is a key factor for cell viability. Both osteogenesis and angiogenesis processes have to demonstrate a coordinated interplay to allow successful bone healing. Therefore, we designed and manufactured macroporous ceramics with a macroarchitecture including a 300 μm pore size and a gyroid structure to ensure blood vessel growth and good penetration of highly vascular connective tissues25,59,60. Contrary to our expectations, and although we observed greater bone formation with macroporous disks with or without TBM, no visible difference in vessel formation was observed in this study between tailored disks and granules. However, the large number of vessels in a bone construct is not always predictive of low or high bone formation. For example, a foreign body reaction can imply inflammation processes leading to angiogenesis and vessel formation without new bone formation. In addition, angiogenesis plays a particular key role at the early step during endochondral or immature bone formation 61,62. When bone formation was observed in this study, histological exams showed mature and well-vascularized bone at 7 weeks. It would be relevant to analyze vessel formation at an earlier stage after material grafting, in order to investigate if greater and faster vessel formation is observed with macroporous ceramics.

This study was based on a small animal model with limited bone defect also limiting the size of the macropores constituting the scaffold. Nevertheless, the syngenic Lewis rat is considered a good model to evaluate the bony potential of materials. Among the different animal models of craniofacial bone defects, the critical-size calvarial defect in rat remains one of the most widely used, because it can be bilaterally, easily and safely performed63–65. Although the rat calvarial defect is only considered as a preliminary model for testing the clinical relevance of BTE strategies, it has allowed us to examine numerous regenerative approaches simultaneously, which would have been impossible in larger animal models due to cost, ethics and logistics. In addition, although allogenic TBM was grafted in our experiments, the syngenic rat model (i.e., clone animals) was chosen to highlight the clinical perspective of our procedure using extemporaneous autologous TBM as it is already applied in clinics45. However, it could be assumed that larger bone reconstruction in larger animals or humans using our reconstruction method could also suffer from inadequate oxygen supply due to the greater bone volume to repair. Consequently, sustainable oxygen supply strategies should be developed to increase the O2 concentration56.

5. Conclusions

The first step towards the regeneration of calvarial CSD, based on 3D-printed CaP disks displaying a TPMS internal architecture, was reported in this study. A one-step surgical approach, making full use of a natural, dispensable and safe bioactive substance (bone marrow) and tailored bioceramics, was successfully implemented and should be seriously considered for further investigation as a relevant alternative to the current gold standards. Safer and cheaper than other promising tissue-engineering strategies based on synthetic active substances (e.g., rhBMP2), the clinical potential of this approach is to be confirmed in large animal models with human-sized relevant craniofacial defects.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: CloudCompare analysis. Comparison of the 3D models of the BCP and CHA bioceramics.

Figure S2: comparison of bone regeneration between micro CT and IHC (Goldner’s trichome staining) images.

Figure S3: Magnification of the IHC images (HES and Goldner’s trichome staining).

Table S1: Animal experiment design for the CSD reconstruction.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Fondation de L’Avenir (grant agreement N°AP-RM-17-017) the Fondation des Gueules Cassées (grant agreement N°66–2017), the National Institutes of Health (grant agreement N° P01-AG007996) to support this study, and English Solutions (Voiron, France) for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

References:

- (1).Sen MK; Miclau T Autologous Iliac Crest Bone Graft: Should It Still Be the Gold Standard for Treating Nonunions? Injury 2007, 38 (1), S75–S80. 10.1016/j.injury.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Grant GA; Jolley M; Ellenbogen RG; Roberts TS; Gruss JR; Loeser JD Failure of Autologous Bone-Assisted Cranioplasty Following Decompressive Craniectomy in Children and Adolescents. J. Neurosurg. 2004, 100 (2 Suppl Pediatrics), 163–168. 10.3171/ped.2004.100.2.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Honeybul S; Morrison DA; Ho KM; Lind CRP; Geelhoed E A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Autologous Cranioplasty with Custom-Made Titanium Cranioplasty. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 126 (1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.317½015.12.JNS152004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Dünisch P; Walter J; Sakr Y; Kalff R; Waschke A; Ewald C Risk Factors of Aseptic Bone Resorption: A Study after Autologous Bone Flap Reinsertion Due to Decompressive Craniotomy. J. Neurosurg. 2013, 118 (5), 1141–1147. https://doi.org/10.317½013.1.JNS12860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Daculsi G; Baroth S; LeGeros R 20 Years of Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Bioceramics Development and Applications In Ceramic Engineering and Science Proceedings; Narayan R, Colombo P, Singh D, Salem J, Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp 45–58. 10.1002/9780470584354.ch5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Herberg S; Kondrikova G; Periyasamy-Thandavan S; Howie RN; Elsalanty ME; Weiss L; Campbell P; Hill WD; Cray JJ Inkjet-Based Biopatterning of SDF-1β Augments BMP-2-Induced Repair of Critical Size Calvarial Bone Defects in Mice. Bone 2014, 67, 95–103. 10.1016/j.bone.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Campana V; Milano G; Pagano E; Barba M; Cicione C; Salonna G; Lattanzi W; Logroscino G Bone Substitutes in Orthopaedic Surgery: From Basic Science to Clinical Practice. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2014, 25 (10), 2445–2461. 10.1007/s10856-014-5240-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kowalczewski CJ; Saul JM Biomaterials for the Delivery of Growth Factors and Other Therapeutic Agents in Tissue Engineering Approaches to Bone Regeneration. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9 10.3389/fphar.2018.00513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Dang M; Saunders L; Niu X; Fan Y; Ma PX Biomimetic Delivery of Signals for Bone Tissue Engineering. Bone Res. 2018, 6 (1). 10.1038/s41413-018-0025-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Leblanc E; Trensz F; Haroun S; Drouin G; Bergeron É; Penton CM; Montanaro F; Roux S; Faucheux N; Grenier G BMP-9-Induced Muscle Heterotopic Ossification Requires Changes to the Skeletal Muscle Microenvironment. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26 (6), 1166–1177. 10.1002/jbmr.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Marchat D; Champion E Ceramic Devices for Bone Regeneration In Advances in Ceramic Biomaterials; Elsevier, 2017; pp 279–311. 10.1016/B978-0-08-100881-2.00008-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Tessier P; Kawamoto H; Posnick J; Raulo Y; Tulasne JF; Wolfe SA Complications of Harvesting Autogenous Bone Grafts: A Group Experience of 20,000 Cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 116 (5 Suppl), 72S–73S; discussion 92S-94S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Rajagopalan S; Robb RA Schwarz Meets Schwann: Design and Fabrication of Biomorphic and Durataxic Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Med. Image Anal. 2006, 10 (5), 693–712. 10.1016/j.media.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Melchels FPW; Barradas AMC; van Blitterswijk CA; de Boer J; Feijen J; Grijpma DW Effects of the Architecture of Tissue Engineering Scaffolds on Cell Seeding and Culturing. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6 (11), 4208–4217. 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Vijayavenkataraman S; Zhang L; Zhang S; Hsi Fuh JY; Lu WF Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces Sheet Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications: An Optimization Approach toward Biomimetic Scaffold Design. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2018, 1 (2), 259–269. 10.1021/acsabm.8b00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Blanquer SBG; Werner M; Hannula M; Sharifi S; Lajoinie GPR; Eglin D; Hyttinen J; Poot AA; Grijpma DW Surface Curvature in Triply-Periodic Minimal Surface Architectures as a Distinct Design Parameter in Preparing Advanced Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Biofabrication 2017, 9 (2), 025001 10.1088/1758-5090/aa6553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Shepherd JH; Shepherd DV; Best SM Substituted Hydroxyapatites for Bone Repair. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2012, 23 (10), 2335–2347. 10.1007/s10856-012-4598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Patel N; Gibson IR; Hing KA; Best SM; Damien E; Revell PA The in Vivo Response of Phase Pure Hydroxyapatite and Carbonate Substituted Hydroxyapaite Granules of Varying Size Ranges. Key Eng. Mater. 2002, 218–220, 383–386. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Spence G; Patel N; Brooks R; Rushton N Carbonate Substituted Hydroxyapatite: Resorption by Osteoclasts Modifies the Osteoblastic Response. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2009, 90 (1), 217–224. 10.1002/jbm.a.32083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Spence G; Patel N; Brooks R; Bonfield W; Rushton N Osteoclastogenesis on Hydroxyapatite Ceramics: The Effect of Carbonate Substitution. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 92 (4), 1292–1300. 10.1002/jbm.a.32373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Barralet J; Akao M; Aoki H; Aoki H Dissolution of Dense Carbonate Apatite Subcutaneously Implanted in Wistar Rats. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 49 (2), 176–182. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yuan L; Ding S; Wen C Additive Manufacturing Technology for Porous Metal Implant Applications and Triple Minimal Surface Structures: A Review. Bioact. Mater. 2019, 4 (1), 56–70. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Coelho PG; Hollister SJ; Flanagan CL; Fernandes PR Bioresorbable Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering: Optimal Design, Fabrication, Mechanical Testing and Scale-Size Effects Analysis. Med. Eng. Phys. 2015, 37 (3), 287–296. 10.1016/j.medengphy.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Halloran JW Ceramic Stereolithography: Additive Manufacturing for Ceramics by Photopolymerization. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2016, 46 (1), 19–40. 10.1146/annurev-matsci-070115-031841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Turnbull G; Clarke J; Picard F; Riches P; Jia L; Han F; Li B; Shu W 3D Bioactive Composite Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2018, 3 (3), 278–314. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Charbonnier B; Laurent C; Blanc G; Valfort O; Marchat D Porous Bioceramics Produced by Impregnation of 3D-Printed Wax Mold: Ceramic Architectural Control and Process Limitations. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2016, 18 (10), 1728–1737. 10.1002/adem.201600308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Miramond T; Corre P; Borget P; Moreau F; Guicheux J; Daculsi G; Weiss P Osteoinduction of Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Scaffolds in a Nude Mouse Model. J. Biomater. Appl. 2014, 29 (4), 595–604. 10.1177/0885328214537859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Seong KC; Cho KS; Daculsi C; Seris E; Guy D Eight-Year Clinical Follow-Up of Sinus Grafts with Micro-Macroporous Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Granules. Key Eng. Mater. 2013, 587, 321–324. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.587.321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Marchat D; Bernache-Assollant D; Champion E Cadmium Fixation by Synthetic Hydroxyapatite in Aqueous Solution—Thermal Behaviour. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 139 (3), 453–460. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Destainville A; Champion E; Bernache-Assollant D; Laborde E Synthesis, Characterization and Thermal Behavior of Apatitic Tricalcium Phosphate. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2003, 80 (1), 269–277. 10.1016/S0254-0584(02)00466-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lafon JP; Champion E; Bernache-Assollant D Processing of AB-Type Carbonated Hydroxyapatite Ca10−x(PO4)6−x(CO3)x(OH)2−x−2y(CO3)y Ceramics with Controlled Composition. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 28 (1), 139–147. 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2007.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (32).International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD). International Centre for Diffraction Data—PDF4+ Relational Powder Diffraction File. Available Online: Http://Www.Icdd.Com/Index.Php/Pdf-4/.

- (33).Raynaud S; Champion E; Bernache-Assollant D; Laval J-P Determination of Calcium/Phosphorus Atomic Ratio of Calcium Phosphate Apatites Using X-Ray Diffractometry. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2004, 84 (2), 359–366. 10.1111/j.1151-2916.2001.tb00663.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Charbonnier B Développement de procédés de mise en forme et de caractérisation pour l’élaboration de biocéramiques en apatites phosphocalciques carbonatées, Lyon, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- (35).ISO 9276–6:2008. Https://Www.Iso.Org/Standard/39389.Html.

- (36).Marchat D; Zymelka M; Coelho C; Gremillard L; Joly-pottuz L; Babonneau F; Esnouf C; Chevalier J; Bernache-assollant D Accurate Characterization of Pure Silicon-Substituted Hydroxyapatite Powders Synthesized by a New Precipitation Route. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9 (6), 6992–7004. 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).LeGeros RZ; Trautz OR; Klein E; LeGeros JP Two Types of Carbonate Substitution in the Apatite Structure. Experientia 1969, 25 (1), 5–7. 10.1007/BF01903856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Elliott JC Structure and Chemistry of the Apatites and Other Calcium Orthophosphates, Elsevier Science.; 1994; Vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Fleet ME Carbonated Hydroxyapatite: Materials, Synthesis, and Applications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Charbonnier B; Laurent C; Marchat D Porous Hydroxyapatite Bioceramics Produced by Impregnation of 3D-Printed Wax Mold: Slurry Feature Optimization. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36 (16), 4269–4279. 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2016.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Juignet L; Charbonnier B; Dumas V; Bouleftour W; Thomas M; Laurent C; Vico L; Douard N; Marchat D; Malaval L Macrotopographic Closure Promotes Tissue Growth and Osteogenesis in Vitro. Acta Biomater. 2017, 53, 536–548. 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Shirasu N; Ueno T; Hirata Y; Hirata A; Kagawa T; Kanou M; Sawaki M; Wakimoto M; Ota A; Imura H; et al. Bone Formation in a Rat Calvarial Defect Model after Transplanting Autogenous Bone Marrow with Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate. Acta Histochem. 2010, 112 (3), 270–277. 10.1016/j.acthis.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Jégoux F; Goyenvalle E; Cognet R; Malard O; Moreau F; Daculsi G; Aguado E Reconstruction of Irradiated Bone Segmental Defects with a Biomaterial Associating MBCP+(R), Microstructured Collagen Membrane and Total Bone Marrow Grafting: An Experimental Study in Rabbits. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2009, 91 (4), 1160–1169. 10.1002/jbm.a.32274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Espitalier F; Vinatier C; Lerouxel E; Guicheux J; Pilet P; Moreau F; Daculsi G; Weiss P; Malard O A Comparison between Bone Reconstruction Following the Use of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Total Bone Marrow in Association with Calcium Phosphate Scaffold in Irradiated Bone. Biomaterials 2009, 30 (5), 763–769. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Corre P; Merceron C; Longis J; Khonsari RH; Pilet P; thi TN; Battaglia S; Sourice S; Masson M; Sohier J; et al. Direct Comparison of Current Cell-Based and Cell-Free Approaches towards the Repair of Craniofacial Bone Defects – A Preclinical Study. Acta Biomater. 2015, 26, 306–317. 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Bansal S; Chauhan V; Sharma S; Maheshwari R; Juyal A; Raghuvanshi S Evaluation of Hydroxyapatite and Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate Mixed with Bone Marrow Aspirate as a Bone Graft Substitute for Posterolateral Spinal Fusion. Indian J. Orthop. 2009, 43 (3), 234–239. 10.4103/0019-5413.49387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Goel A; Sangwan SS; Siwach RC; Ali AM Percutaneous Bone Marrow Grafting for the Treatment of Tibial Non-Union. Injury 2005, 36 (1), 203–206. 10.1016/j.injury.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Moro-Barrero L; Acebal-Cortina G; Suarez-Suarez M; Perez-Redondo J; Murcia-Mazon A; Lopez-Muniz A Radiographic Analysis of Fusion Mass Using Fresh Autologous Bone Marrow With Ceramic Composites as an Alternative to Autologous Bone Graft: J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2007, 20 (6), 409–415. 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318030ca1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Kapfer SC; Hyde ST; Mecke K; Arns CH; Schröder-Turk GE Minimal Surface Scaffold Designs for Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2011, 32 (29), 6875–6882. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Alonso N; Tanikawa DYS; Freitas R da S; Canan Lady; Ozawa TO; Rocha DL Evaluation of Maxillary Alveolar Reconstruction Using a Resorbable Collagen Sponge with Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 in Cleft Lip and Palate Patients. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2010, 16 (5), 1183–1189. 10.1089/ten.tec.2009.0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Balaji SM Use of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein (RhBMP-2) in Reconstruction of Maxillary Alveolar Clefts. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2009, 8 (3), 211–217. 10.1007/s12663-009-0052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Neovius E; Lemberger M; Docherty Skogh Ac.; Hilborn J; Engstrand T Alveolar Bone Healing Accompanied by Severe Swelling in Cleft Children Treated with Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 Delivered by Hydrogel. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2013, 66 (1), 37–42. 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Woo EJ Adverse Events Reported After the Use of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70 (4), 765–767. 10.1016/j.joms.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Cipitria A; Wagermaier W; Zaslansky P; Schell H; Reichert JC; Fratzl P; Hutmacher DW; Duda GN BMP Delivery Complements the Guiding Effect of Scaffold Architecture without Altering Bone Microstructure in Critical-Sized Long Bone Defects: A Multiscale Analysis. Acta Biomater. 2015, 23, 282–294. 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Damia C; Marchat D; Lemoine C; Douard N; Chaleix V; Sol V; Larochette N; Logeart-Avramoglou D; Brie J; Champion E Functionalization of Phosphocalcic Bioceramics for Bone Repair Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 95, 343–354. 10.1016/j.msec.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Tian T; Zhang T; Lin Y; Cai X Vascularization in Craniofacial Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97 (9), 969–976. 10.1177/0022034518767120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Tian T; Liao J; Zhou T; Lin S; Zhang T; Shi S-R; Cai X; Lin Y Fabrication of Calcium Phosphate Microflowers and Their Extended Application in Bone Regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9 (36), 30437–30447 10.1021/acsami.7b09176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Weigand A; Beier JP; Hess A; Gerber T; Arkudas A; Horch RE; Boos AM Acceleration of Vascularized Bone Tissue-Engineered Constructs in a Large Animal Model Combining Intrinsic and Extrinsic Vascularization. Tissue Eng. Part A 2015, 21 (9–10), 1680–1694. 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Konopnicki S; Troulis MJ Mandibular Tissue Engineering: Past, Present, Future. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73 (12 Suppl), S136–146. 10.1016/j.joms.2015.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Walthers CM; Nazemi AK; Patel SL; Wu BM; Dunn JCY The Effect of Scaffold Macroporosity on Angiogenesis and Cell Survival in Tissue-Engineered Smooth Muscle. Biomaterials 2014, 35 (19), 5129–5137. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Schipani E; Wu C; Rankin EB; Giaccia AJ Regulation of Bone Marrow Angiogenesis by Osteoblasts during Bone Development and Homeostasis. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4 10.3389/fendo.2013.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Zigdon-Giladi H; Michaeli-Geller G; Bick T; Lewinson D; Machtei EE Human Blood-Derived Endothelial Progenitor Cells Augment Vasculogenesis and Osteogenesis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42 (1), 89–95. 10.1111/jcpe.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Inoda H; Yamamoto G; Hattori T Rh-BMP2-Induced Ectopic Bone for Grafting Critical Size Defects: A Preliminary Histological Evaluation in Rat Calvariae. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 36 (1), 39–44. 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Develıoğlu H; Saraydin SÜ; Bolayir G; Dupoirieux L Assessment of the Effect of a Biphasic Ceramic on Bone Response in a Rat Calvarial Defect Model. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 77A (3), 627–631. 10.1002/jbm.a.30692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Bosch C; Melsen B; Vargervik K Importance of the Critical-Size Bone Defect in Testing Bone-Regenerating Materials. J. Craniofac. Surg. 1998, 9 (4), 310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: CloudCompare analysis. Comparison of the 3D models of the BCP and CHA bioceramics.

Figure S2: comparison of bone regeneration between micro CT and IHC (Goldner’s trichome staining) images.

Figure S3: Magnification of the IHC images (HES and Goldner’s trichome staining).

Table S1: Animal experiment design for the CSD reconstruction.