Abstract

Background:

There are a growing number of forced migrants worldwide. Early detection of poor adjustment and interventions to facilitate positive adaptation within these communities is a critical global public health priority. A growing literature points to challenges within the postmigration context as key determents of poor mental health.

Aims:

The current meta-analysis evaluated the association between daily stressors and poor mental health among these populations.

Method:

A systematic search in PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science identified relevant studies from inception until the end of 2018. Effect sizes (correlation coefficients) were pooled using Fisher’s Z transformation and reported with 95% confidence intervals. Moderator and mediator analyses were conducted. The protocol is available in PROSPERO [CRD42018081207].

Results:

Analysis of 59 eligible studies (n=17,763) revealed that daily stressors were associated with higher psychiatric symptoms (Zr=0.126-0.199, 95% CI=0.084-0.168, 0.151-0.247, p<0.001) and general distress (Zr=0.542, 95% CI=0.332-0.752, p<0.001). Stronger effect sizes were observed for mixed daily stressors relative to subjective, interpersonal, and material daily stressors, and for general distress relative to posttraumatic stress symptoms and general well-being. Effect sizes were also stronger for children and adolescents relative to adults. Daily stressors fully mediated the associations of prior trauma with post-migration anxiety, depressive, and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Conclusions:

This meta-analysis provides a synthesis of existing research on the role of unfavorable everyday life experiences and their associations with poor mental health among conflict-affected forced migrants. Routine assessment and intervention to reduce daily stressors can prevent and reduce psychiatric morbidity in these populations.

Keywords: Everyday life, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, refugees, forced migrants

The largest forced migration and displacement of people affected by civil conflicts occurred in the past two decades. The traumatic nature of these events gives rise to an enormous need for providing mental health and psychosocial support to conflict-affected forced migrants (Fazel et al., 2012; Tol et al., 2011). These populations demonstrated a high burden of common mental disorders including anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Morina et al., 2018; Siriwardhana et al., 2014).

Large variations in prevalence of these disorders were observed in previous studies. Over 40% of refugees were diagnosed with anxiety and depression relative to 20% among labor migrants (Lindert et al., 2009). An unadjusted PTSD and depression prevalence of about 30% was observed among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement (Steel et al., 2009). The prevalence of PTSD and depression among refugees residing in western countries was 9% and 5%, respectively (Fazel et al., 2005). Among internally displaced adults and refugees fleeing armed conflict, the prevalence of PTSD varied from 2.2% to 88.3%, anxiety from 1% to 90%, and depression from 5.1% to 81% (Bogic et al., 2015; Morina et al., 2018). Sample size and sampling method accounted for the variance in prevalence, with higher rates reported by studies of smaller sample size and mixed nonprobabilistic sampling. Variation in prevalence is smaller among children and adolescents, with PTSD ranging between 19 and 52.7%, anxiety disorders between 8.7 and 31.6%, and depressive disorders between 10.3 and 32.8% (Kien et al., 2018).

Psychological distress among refugees and forced migrants is largely explained by exposures to stressors occurring across the migration continuum (Zimmerman et al., 2011). Pre-migration demographic characteristics such as older age, female sex, higher education level, and higher socioeconomic status are not consistently associated with psychological distress (Bogic et al., 2015; Porter and Haslam, 2005). Post-migration experiences have increasingly been investigated. Everyday life after conflict exposure and migration is often plagued with demands that undermine health as much or more than a trauma exposure itself (Chen et al., 2017; Fazel, 2018; Hou et al., 2018; Hynie, 2018; Morina et al., 2011; Nickerson et al., 2015; Nickerson et al., 2011; Steel et al., 2006). Factors including discrimination, restrictions in living arrangements, settlement in refugee camp, among others, were associated with higher depressive and PTSD symptoms among refugee children (Bronstein and Montgomery, 2011; Fazel et al., 2012; Porter and Haslam, 2005; Tol et al., 2013).

According to the Daily Stressor Model (Miller and Rasmussen, 2010, 2014), one category involves low intensity social and material stressors that are present daily, such as poverty, social isolation, and poor or insecure neighborhoods. Another category is potentially traumatic stressors that occur occasionally and recurrently but not necessarily daily, such as armed conflicts, sexual violence, and death of loved ones. Prior trauma exposure is expected to contribute to more negative experiences in daily living (i.e., higher daily stressors), which, in turn, predict poorer mental health during or after conflicts (Miller and Rasmussen, 2010, 2014). An elaborated social ecological model suggested that refugees’ psychological distress is dependent upon ongoing stressors as well as prior trauma exposure (Miller and Rasmussen, 2017). Displacement-related stressors are a subset of daily stressors that are originated from both armed conflicts and forced migration. The combined stressors, both material (e.g., poverty, loss of possessions) and interpersonal (e.g., family conflict and violence, loss of social support networks), then contribute to poorer mental health and family functioning.

A recent model provided further conceptualization and differentiation on low-intensity stressors that were specified in the Daily Stressor Model. According to the Drive to Thrive (DTT) theory, psychological resilience, denoting absence of psychological distress and/or presence of psychological well-being, is determined by sustaining regularity and structure of daily routines after conflicts (Hou et al., 2018). Trauma contributes to lower regularity of daily routines, which, in turn, predicts poorer mental health. The mechanism underlying this process is a lower sense of predictability, reduced coping flexibility, and less engagement in important life tasks, which leads to lower mental health over time. Two types of daily routines were elaborated on this model, namely primary and secondary daily routines. Primary daily routines refers to behaviors that are necessary for maintaining livelihood, such as hygiene, sleep, eating, and home maintenance, whereas secondary daily routines refers to optional behaviors that are dependent upon motivation and preferences, such as exercising, leisure, social activities, and employment or work involvement (Baltes et al., 1999; Hou et al., 2019). In immediate deprived conditions like post-migration settings or disasters, reduced regularity of primary rather than secondary routines could have stronger associations with poor mental health (Doğan and Kahraman, 2011; Tatsuki, 2007).

The goal of this meta-analysis is to provide a comprehensive, quantitative review of the link between everyday life experiences and poor mental health in order to inform development of mental health screening and cost-effective intervention for at-risk individuals following forced migration (Betancourt et al., 2010). Several aims were addressed in this study. First, we reviewed and identified different types of unfavorable post-migration everyday life experiences and mental health outcomes that have been studied in conflict-affected forced migrants. Second, we quantified the associations between everyday life experiences and common mental health outcomes, namely anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, general distress, and general well-being. Third, we tested potential moderators of the associations between everyday life experiences and mental health. Fourth, we tested the hypothesized, theory-driven mediating effects of different types of post-migration daily experiences in the associations between prior trauma exposure and different mental health outcomes. Based on the Daily Stressor Model, we expected to identify different dimensions of unfavorable everyday experiences, including but not limited to ongoing low-intensity social and material stressors. We also expected that unfavorable everyday experiences would mediate the association between pre-migration/prior trauma exposure and mental health outcomes, such that prior trauma relates to more negative everyday experiences, which then contribute to poorer mental health. Based on the DTT theory, we expected that disruptions to primary daily routines, measured by food insecurity, sleep, and adequate shelter were more strongly associated with mental health outcomes relative to secondary routines including leisure and social activities and interpersonal relationships.

Method

Search Strategy

We searched PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science for primary studies. All studies published on or before December 31st 2018 were included. Keywords pertinent to the population of interest [refugee* or post-conflict or conflict affected or asylum seeker* or migrant*], everyday life experiences [everyday or daily or post migration* or post migration stress*], and mental health [anxiety or anxiety disorder* or anxiety symptom* or anxious feeling* or anxious mood or depression or depressive disorder* or depressive symptom* or depressed feeling* or depressed mood* or post-traumatic stress* or post-traumatic stress disorder* or post-traumatic stress symptom* or post-traumatic stress response* or traumatic stress or traumatic stress disorder* or traumatic symptom* or traumatic response* or psychological distress or psychological symptom* or psychological dysfunction* or emotional distress or psychiatric symptom* or psychiatric condition* or mental health] were used. Duplicate studies were removed prior to assessment for eligibility.

Selection of Studies

Studies were eligible for inclusion in this review if they were empirical studies involving forced migrants or populations affected by conflicts, and with at least one clearly defined quantitative measure for each of everyday life experiences and mental health outcome. Should a study involve the target population of interest but meeting one of the remaining criteria, it was graded as relevant. Studies were excluded if no effect size was reported, predictor (i.e., measurement of everyday life experiences) and/or outcome measures (i.e., mental health) was/were absent, measurement tools were psychometrically validated, and the entire paper was published in language other than English. HK and ES performed the initial search and screening by reviewing titles and abstracts. Eligibility was then checked by HK, ES, and another independent reviewer, WKH. The reference list of all articles graded as relevant was examined by WKH to identify eligible studies that may otherwise be missed. Full texts of eligible studies were then retrieved for qualitative synthesis and meta-analysis.

Data Extraction and Coding

Two independent researchers (NL and LL) extracted the following data from the included studies: study design, sampling method, age, sex, type of population, measurement of trauma exposure, everyday life experiences, and mental health. Reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alphas) of the measurements were also recorded. To ensure reliability of the review process, 10% of the articles in the final data set were reviewed by other reviewers (WKH and JH). Any discrepancies were resolved by the senior author (WKH).

Measurement Scales

Data from self-report instruments were categorized into groups as appropriate. Data on everyday life experiences were categorized according to the nature of measurement, namely (1) subjective daily stressors, (2) interpersonal daily stressors, (3) material daily stressors, and (4) mixed daily stressors. Higher scores indicated higher daily stressors. These experiences were consistent with low intensity social and material stressors that were proposed in the Daily Stressor Model (Miller and Rasmussen, 2010, 2014). Subjective daily stressors were measured with reference to emotional valence or distressed feelings associated with the experience (e.g., DeLongis et al., 1988; Kanner et al., 1981; Morville et al., 2015; Paardekooper et al., 1999; Schwartz et al., 2010; Vinokurov et al., 2002). Interpersonal daily stressors were measured in terms of interpersonal interactions associated with their post-migration experiences (Baptiste, 2017; Kashyap et al., 2019; Schweitzer et al., 2006; Silove et al., 1997; Teodorescu et al., 2012). Material daily stressors referred to difficulties including housing and accommodation, neighborhood, employment-related issues, and access to social and mental health services (Georgiadou et al., 2018; Schweitzer et al., 2011; Thela et al., 2017). Mixed daily stressors were combined measures of more than one type of daily stressors listed above (Birman and Tran, 2008; Idemudia et al., 2013; Toar et al., 2009). Definitions and measurement scales of different types of daily stressors are listed in Supplementary Material 1. Measurement scales of mental health outcomes, namely anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, general distress, and general well-being, are listed in Supplementary Material 1 as well.

Preparation of Effect Sizes

The majority of studies reported correlation coefficients, standardized regression coefficients (Eq. 1), and χ2 tests (Eq. 2), so each was converted to correlation coefficients rusing the following equations prior to pooling of effect sizes:

| (Eq. 1) |

| (Eq. 2) |

Where n denotes sample size; λ = 1 if β is positive and λ = 0 if β is negative. For studies reporting multiple effect sizes for the same sample, we computed an average effect size to preserve statistical independence of effect sizes.

Pooling of Effect Sizes

To adjust for the skewed r distribution, correlation coefficients were transformed into normally distributed Fisher’s Zr:

| (Eq. 3) |

Where Zr is Fisher’s Z transformed correlation, ln represents the natural logarithm and r is the reported Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. The standard error was then computed accordingly (Eq. 4). The effect sizes were weighted by inverse variance (Eq. 5) and back-transformed to correlation coefficient for presentation (Eq. 6). The standard error for the pooled correlation was then computed by Eq. 7.

| (Eq. 4) |

| (Eq. 5) |

| (Eq. 6) |

| (Eq. 7) |

Where e refers to the base of the natural logarithm.

Study Heterogeneity and Moderator Analyses

Heterogeneity of effect estimates between studies was determined using Cochran’s Q test and quantified by Higgins I2 statistics as small, medium, and high degree based on I2 index of <25%, >50%, and >75%, respectively. For I2 more than 50% and p<0.10 by Cochran’s Q test, a random effect model was used to compute pooled effect sizes in 95% confidence interval. For I2 less than 50%, a fixed effect model would be employed. To account for inter-study heterogeneity, meta-regressions with sub-group analysis were performed with continuous and categorical moderators, including study design (cross-sectional or longitudinal), sample type (refugees, asylum seekers, mixed refugees and asylum seekers, or immigrants), time since trauma exposure, time since migration, different types of daily stressors, primary/secondary daily routines, type of outcomes, age, sex, and type of host countries (developing or developed countries; United Nations Development Programme, 2018). Primary and secondary daily routines were distinguished based on previous theoretical frameworks, with primary routines referring to essential behaviors that are linked to survival and biological needs and secondary routines referring to discretionary behaviors based on preference and motivation (Baltes et al., 1999; Hou et al., 2018) (Supplementary Material 1).

Mediator Analyses

Both Daily Stressor Model and Drive to Thrive theory suggested that everyday life experiences mediate the associations between major stressors and mental health (Hou et al., 2018, 2019; Miller and Rasmussen, 2010, 2014). Therefore, mediating effects of different types of unfavorable everyday life experiences in the associations between prior traumatic exposure and mental health outcomes (i.e., anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, general distress, aggregated poor mental health outcomes, and general well-being) were tested using meta-analytic structural equation modeling (metaSEM; Cheung, 2015; Cheung and Chan, 2005) implemented on R platform via the OpenMx package (Boker et al., 2011). Significance of parameter estimates was assessed with 95% likelihood-based confidence intervals (Neale and Miller, 1997; Roorda et al., 2017). If the 95% confidence interval around a parameter estimate did not include zero, the parameter estimate was considered significant at a 5% level. A mediating effect was indicated by the indirect effect between prior trauma and an outcome. The indirect effect was the product of the parameter estimates of the association between prior trauma and daily stressors and the association between daily stressors and the outcome. An indirect effect was considered as full mediation if the association between prior trauma and the outcome became non-significant (i.e., 95% CI of the parameter estimates included zero).

Quality Assessment

Study quality was appraised using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for non-randomized observational studies, a tool with established content validity and inter-rater reliability (Stang, 2010). The method assessed each study based on three domains: representativeness of the participants (selection), proper adjustment for confounders (comparability), and appropriateness of outcome ascertainment (outcome). For each study, a maximum of one point was given to each variable under each assessment domain.

Publication Bias

To minimize the possibility of over-inflation of the pooled effect sizes due to the file-drawer problem, publication bias was visualized by Begg’s funnel plot. The degree of asymmetry was tested by Egger’s test and corrected by Duval-Tweedie trim-and-fill method. In addition, we calculated classic fail-safe number (NR) to determine the number of missing studies that would render the pooled effect size insignificant. If NR≥5k+10, where k is the number of included studies in the meta-analysis, publication bias would be considered minimal. The mediator analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 3.0 (Biostat Inc, Engelwood, NJ, USA) and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 24.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Unless otherwise stated, random effect models were employed. All tests were two-tailed.

Results

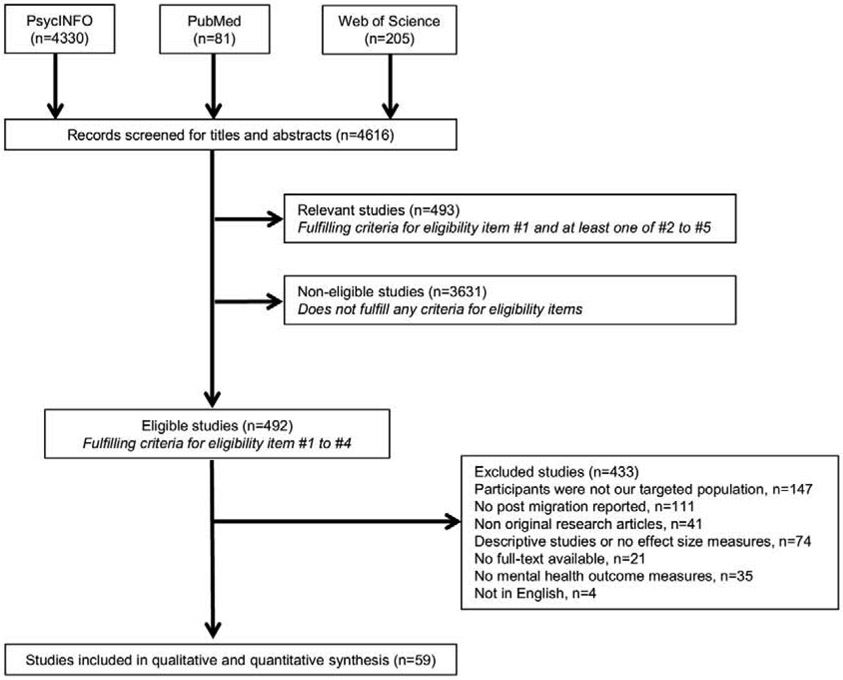

Of 4,616 articles obtained from the initial search, 4,124 were removed due to failure to fulfill pre-defined inclusion criteria, resulting in 492 articles. After exclusion, the meta-analysis included 59 studies with 304 effect sizes (k) involving 10,680 (60%) refugees, 1,755 (10%) asylum seekers, 2,054 (12%) refugees and asylum seekers (mixed sample), and 3,274 (18%) immigrants (Figure 1). The majority of the effect sizes were derived from studies using convenience samples (k=201, 66%). The mean age of the included participants was 35.60 years (SD=13.80) with the proportion of male participants ranging from 0% to 100%. All studies were published between 1997 and 2019 (Table 1). Predictors were measured by numerous standardized instruments or subscales of standardized instruments.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for selection of studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies in the meta-analysis

| First author (Year) |

N | k | Country of origin |

Host country |

Male % | Mean age |

Sample | Everyday life experiences | Mental health | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Category | Measures | Category | ||||||||

| Alemi (2018) | 259 | 8 | Afghan | U.S. | 48.6 | 48.8 | Refugee | PMF: ethnic orientation-assimilation PMF: ethnic orientation-separation PMF: ethnic orientation-integration PMF: ethnic orientation-attenuated integration PMF: civic engagement PMF: social support PMF: perceived discrimination PMF: intra ethnic identity |

DS (S) DS (S) DS (S) DS (S) DS (M) DS (I) DS (I) DS (S) |

TBDI | General distress |

| Baptiste (2017) | 118 | 3 | Bhutan, Nepal, Somali | U.S. | 49.7 | 43.7 | Refugee and asylum seeker | PMLD-stigma | DS (I) | HSCL-a HSCL-d HTQ-R-Part IV |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Bentley (2012) | 74 | 3 | Somali | U.S. | 64.9 | 39.1 | Refugee | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | HSCL-a HSCL-d HTQ |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Birman (2008) | 212 | 15 | Vietnam | U.S. | 51 | 48.8 | Refugee | LIB: language, acculturation subscale LIB: behaviour subscales LIB: identity subscales |

DS (Mixed) DS (Mixed) DS (Mixed) |

HSCL-a HSCL-d FYQoLS |

Anxiety Depression General well-being |

| Bogic (2012) | 854 | 12 | Fomrer Yugoslavia | Germany Italy UK |

48.7 | 41.6 | Refugee | NPMS PMF: unemployment PMF: not living with partner PMF: feeling accepted by the host country PMF: language proficiency PMF: temporary residence status |

DS (Mixed) DS (M) DS (I) DS (S) DS (M) DS (M) |

MINI MINI |

Anxiety PTSD |

| Bruhn (2018) | 116 | 3 | Various | Denmark | 56 | NA | Refugee | PMF: accommodation difficulties PMF: employment difficulties PMF: family difficulties |

DS (M) DS (M) DS (I) |

HTQ | PTSD |

| Cantekin (2017) | 111 | 3 | Syrian | Turkey | 44.1 | 37.6 | Asylum seeker | PMLD: loss of culture and support | DS (S) | HSCL-a HSCL-d HTQ-R-Part IV |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Carlsson (2006) | 63 | 21 | Various | Denmark | 100 | 37.8 | Refugee | PMF: social relation PMF: occupation PMF: pain |

DS (I) DS (M) DS (S) |

HSCL-a HDS HSCL-d WHOQOL-BREF |

Anxiety Depression Depression General well-being |

| Chen (2017) | 2399 | 3 | NA | Australia | 54 | NA | Immigrants | PMF: economic stressors PMF: loneliness and boredom PMF: worry about family and friends |

DS (M) DS (SF) DS (S) |

PTSD-8 | PTSD |

| Chu (2013) | 875 | 2 | NA | U.S. | 64 | 34.4 | Immigrants | PMF: legal immigration status PMF: language proficiency |

DS (M) DS (M) |

HTQ | PTSD |

| Cummings (2011) | 70 | 1 | Kurdi | U.S. | 47.1 | 59.0 | Refugee | MGLQ-disorganization | DS (S) | GDS | Depression |

| Ellis (2010) | 135 | 2 | Somalia | 62.2 | 15.4 | Refugee | EDS | DS (I) | DSRS UCLA PTSD-I |

Depression PTSD |

|

| Ellis (2013) | 30 | 2 | Somalia | U.S. | 63.3 | 13.0 | Refugee | PWAI | DS (Mixed) | DSRS PTSD-RI |

Depression PTSD |

| Finklestein (2012) | 478 | 1 | Jewish Ethiopian | Israel | 53.9 | 39.9 | Refugee | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | HTQ | PTSD |

| Georgiadou (2018) | 200 | 6 | Syrian | Germany | 69.5 | 33.3 | Refugee | PMF: duration of stay in host country PMF: residence permit |

DS (M) | ETI PHQ-9 GAD-7 |

PTSD Depression Anxiety |

| Gerritsen (2006) | 410 | 2 | Afghanistan, Iran, and Somalia | Netherlands | 58.8 | 37.0 | Refugee and asylum seeker | NPMS | DS (Mixed) | HTQ HSCL |

PTSD General distress |

| Hengst (2018) | 294 | 1 | Iraqi | Netherlands | 64.6 | 35.4 | Asylum seeker | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | WHOQOL-BREF | General well-being |

| Hollifield (2005) | 67 | 3 | Kurdish and Vietnam | U.S. | 54 | 45.6 | Refugee | SDI: work SDI: family SDI: social |

DS (M) DS (I) DS (I) |

SF-36 | Depression |

| Hollifield (2018) | 252 | 3 | Kursh and Vietnam | U.S. | 54 | 44.0 | Refugee | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | HSCL-a HSCL-d PSS-SR |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Ichikawa (2006) | 55 | 3 | Afghan | Japan | 96 | 30.2 | Asylum seeker | PMF: detention | DS (I) | HSCL-a HSCL-d HTQ |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Idemudia (2013) | 125 | 2 | Zimbabwe | South Africa | 57.6 | 28.3 | Refugee | PPMD checklist | DS (Mixed) | PCL-C GHQ-28: Depression |

PTSD Depression |

| Jordans (2012) | 269 | 1 | Various | Jordan Nepal |

56.9 | 36.9 | Refugee | HESPER | DS (Mixed) | CIDI | PTSD |

| Kartal (2016) | 119 | 15 | Bosnia | Australia Austria |

53.7 | 40.9 | Refugee | DI: loss DI: language DI: not feeling at home DI: occupation DI: discrimination |

DS (S) DS (M) DS (S) DS (M) DS (I) |

DASS-a DASS-d PDS |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Kashyap (2019) | 323 | 10 | Various | U.S. | 63.8 | 37.9 | Refugee and asylum seeker | PMF: housing status PMF: unemployment PMF: chronic pain PMF: emotional support PMF: organizational support |

DS (M) DS (M) DS (S) DS (I) DS (M) |

PHQ-9 HTQ |

Depression PTSD |

| Keles (2015) | 895 | 3 | Various | Norway | N/A | 18.6 | Refugee | YCCHB | DS (I) DS (M) |

CES-d | Depression |

| Keles (2018) | 864 | 6 | Various | Norway | 82.4 | 19.0 | Asylum seeker | YCCHB Host culture competence Heritage culture competence |

DS (I) DS (S) DS (S) |

CES-d | Depression |

| Kim (2016) | 656 | 1 | Various | U.S. | 54.6 | 47.3 | Refugee | EDS | DS (I) | SRQ | Anxiety |

| Kim (2019) | 291 | 2 | Vietnamese | 45.8 | 45.6 | Refugee | PMF: racial discrimination PMF: everyday discrimination |

DS (I) DS (I) |

KPDS | General distress | |

| Laban (2005) | 294 | 2 | Iraqi | Netherlands | 64.6 | NA | Asylum seeker | PMF: family difficulties PMF: unemployment |

DS (I) DS (M) |

WHO-CIDI | Depression |

| Le (2018) | 108 | 2 | Various | Switzerland | 78.7 | 43.2 | Refugee and asylum seeker | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | PDS HSCL-d |

PTSD Depression |

| LeMaster (2018) | 298 | 4 | Iraq | U.S. | N/A | 33.4 | Refugee | HS AAS |

DS (Mixed) DS (Mixed) |

HADS PCL-C |

Depression PTSD |

| Miller AM (2002) | 200 | 1 | Soviet Union | U.S. | 0 | 56.8 | Refugee | DI | DS (Mixed) | CES-d | Depression |

| Minihan (2018) | 246 | 1 | Various | Australia | 45.1 | 38.3 | Refugee and asylum seeker | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | PDS | PTSD |

| Molsa (2014) | 128 | 3 | Somali | Finland | 41.4 | 57.9 | Refugee | PMF: duration of residency PMF: language proficiency |

DS (M) DS (M) |

BDI HRQoL |

Depression General well-being |

| Morgan (2017) | 97 | 12 | Various | UK | 53 | 33.8 | Asylum seeker | PMF: isolation PMF: poor access to services PMF: ethnic community support PMF: interethnic support |

DS (I) DS (M) DS (M) DS (M) |

HSCL-a HSCL-d HTQ |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Nickerson (2015) | 134 | 2 | Various | Switzerland | 78.4 | 42.4 | Refugee and asylum seeker | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | PDS HSCL-d |

PTSD Depression |

| Rasmussen (2010) | 848 | 5 | Durfur | Chad | 34.9 | 33.9 | Refugee | Displacement stressors: basic stressors Displacement stressors: perceived safety |

DS (M) DS (S) |

PCL-C BSI-D |

PTSD Depression |

| Riley (2017) | 148 | 2 | Various | Bangladesh | 47 | 34.0 | Refugee | HESPER | DS (Mixed) | HTQ BSI-D |

PTSD Depression |

| Sangalang(2018) | 657 | 16 | Various | U.S. | 56.7 | 44.4 | Refugee | PMF: everyday discrimination PMF: acculturative stress PMF: family conflict PMF: neighbourhood context |

DS (I) DS (S) DS (I) DS (M) |

WHO-CIDI WHO-CIDI |

Anxiety Depression |

| Schick (2016) | 104 | 4 | Various | Switzerland | 79 | 43.0 | Refugee | PMLD checklist: integration difficulties | DS (I) | HSCL-a HSCL-d PDS SF-12 |

Anxiety Depression PTSD General well-being |

| Schick (2018) | 71 | 2 | Various | Switzerland | 61 | 44.5 | Refugee and asylum seeker | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | PDS HSCL |

PTSD General distress |

| Schweitzer (2006) | 53 | 18 | Sudan | Australia | 42 | 34.2 | Refugee | PMLD checklist PMF: duration of residency PMF: family separation PMF: ethnic community support PMF: host country community support PMF: employment |

DS (Mixed) DS (M) DS (I) DS (M) DS (M) DS (M) |

HSCL-a HSCL-d HTQ |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Schweitzer (2011) | 70 | 2 | Burma | Australia | 42.9 | 34.1 | Refugee | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | HSCL-a HSCL-d |

Anxiety Depression |

| Schweitzer (2018) | 104 | 2 | Various | Australia | 0 | 32.5 | Refugee | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | HSCL-a HSCL-d |

Anxiety Depression |

| Seglem (2014) | 223 | 1 | Various | Norway | 81 | 20.0 | Refugee | HS | DS (Mixed) | CES-d | Depression |

| Silov (1997) | 40 | 9 | Various | Australia | 52.5 | 35.0 | Asylum seeker | PMLD checklist PMF: being interviewed by immigration officials PMF: being or experiencing conflict with immigration officials PMF: not having working permit PMF: unemployment PMF: racial discrimination PMF: loneliness and boredom PMF: delays in processing refugee application |

DS (Mixed) DS (I) DS (I) DS (M) DS (M) DS (I) DS (S) DS (M) |

HSCL-a HSCL-d CIDI-PTSD |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Song (2015) | 278 | 7 | Various | U.S. | 45.33 | 40.3 | Refugee and asylum seeker | PMF: housing status PMF: present complaint PMF: received social service PMF: mental health service |

DS (M) DS (S) DS (M) DS (M) |

HSCL-a HSCL-d PCL |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Song (2018) | 278 | 15 | Various | U.S. | 45.33 | 40.3 | Refugee and asylum seeker | PMF: basic resources PMF: external risk PMF: family relationship PMF: social relation PMF: language proficiency |

DS (M) DS (Mixed) DS (I) DS (I) DS (M) |

HSCL-a HSCL-d PCL |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Steel (2017) | 420 | 3 | Various | Sweden | 50 | 33.0 | Refugee | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | HSCL-a HSCL-d HTQ |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Tay (2015) | 230 | 8 | Various | Papua New Guinea | 59.5 | 37.0 | Refugee | HESPER | DS (Mixed) | RMHAP | General well-being |

| Teodorescu (2012a) | 55 | 8 | Various | Norway | 59 | 42.0 | Refugee | PMF: weak social network PMF: weak social integration into host country PMF: weak social network into ethnic culture PMF: unemployment |

DS (I) DS (I) DS (I) DS (M) |

IES-R HSCL-d |

PTSD Depression |

| Teodorescu (2012b) | 55 | 3 | Various | Norway | 58 | 42.0 | Refugee | PMF: weak social network PMF: weak social integration into host country PMF: unemployment |

DS (I) DS (I) DS (M) |

WHOQOL-BREF | General well-being |

| Thela (2017) | 335 | 3 | Congo, Zimbabwe | South Africa | 53 | 32.8 | Refugee | PMF: everyday discrimination | DS (I) | HSCL-a HSCL-d HTQ |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Tinghög (2017) | 1215 | 21 | Syria | Sweden | 62.8 | NA | Refugee | PMF: often disrespected due to my national background PMF: often have bad bothering difficulties communicating in Swedish PMF: often been unable to buy necessities PMF: often missing my social life from back home PMF: often felt sad because not reunited with family members PMF: often felt excluded or isolated in Swedish society PMF: often distressing conflicts in family |

DS (I) DS (I) DS (M) DS (I) DS (I) DS (I) DS (I) |

HSCL-a HSCL-d HTQ |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Tingvold (2015) | 61 | 1 | Vietnam | Norway | 88.5 | 47.5 | Refugee | AHQ | DS (I) | SCL | General distress |

| Toar (2009) | 88 | 2 | Various | Ireland | 67 | 42.0 | Refugee and asylum seeker | NPMS | DS (Mixed) | HSCL-25 HTQ |

General distress PTSD |

| Vervliet (2014) | 103 | 3 | Various | Belgium | 84.5 | 16.0 | Refugee | DSSYR | DS (Mixed) | HSCL-a HSCL-d RATS |

Anxiety Depression PTSD |

| Vinokurov (2002) | 146 | 2 | Soviet Union | U.S. | N/A | 16.1 | Refugee | AHI | DS (Mixed) | HSCL-a | Anxiety |

| Wyk (2012) | 62 | 3 | Burma | Australia | 43 | 34.0 | Refugee | PMLD checklist | DS (Mixed) | HSCL-a HSCL-d |

Anxiety Depression |

Note. N, number of participants; k, number of effect sizes; AAS, Arab Acculturation Scale; AHI, Acculturative Hassles Inventory; AHQ, Acculturative Hassles Questionnaire; BDI, Beck's Depression Inventory; BSI-D, Depression subscale of the Brief Symptom Inventory; CES-d, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-depression; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DASS-a, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale subscale anxiety; DASS-d, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale subscale depression; DI, Demands of Immigration Scale; DS (S), Daily stressors (subjective); DS (I), Daily stressors (interpersonal); DS (M), Daily stressors (materials); DS (Mixed), Daily stressors (mixed); DSRS, Depression Self-Rating Scale; DSSYR, Daily Stressors Scale for Young Refugees; EDS, Everyday Discrimination Scale; ETI, Essen Trauma Inventory; FYQoLS, Fazel and Young’s Quality of Life Scale; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 items; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; GHQ-28: Depression, General Health Questionnaire 28: Depression; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HDS, Hamilton Depression Scale; HESPER, The Humanitarian Emergency Settings Perceived Needs Scale; HRQOL, Health-Related Quality of Life; HS, Hassles Scale; HSCL-a, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-anxiety; HSCL-d, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-depression; HTQ, Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; IES-R, Impact of Events Scale-Revised; KPDS, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; LIB, Language, Identity, and Behavior Scale; MGLQ, Migratory Grief and Loss Questionnaire; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NPMS, Number of Post Migration Stressors; PCL, PTSD Checklist; PCL-C, PTSD Checklist (Civilian Version); PDS, Post-Traumatic Diagnostic Scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PMLD checklist, Post Migration Living Difficulties checklist; PMF, Post Migration Factor; PSS-SR, PTSD Symptom Scale-Self Report; PTSD-8, 8-item from the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire Part IV; PTSD-RI, PTSD Reaction Index; PWAI, Post-War Adversity Index; RATS, Reactions of Adolescents to Traumatic Stress; SDI, Sheehan Disability Inventory; RMHAP, Refugee Mental Health Assessment Package; SCL, Symptom Checklist; SF-12, Medical Outcome Study-Short Form 12 items; SRQ, Self-Report Questionnaire; TBDI, Talbieh brief distress inventory; UCLA PTSD-I, The UCLA PTSD Index; WHOQOL-BREF, WHO Quality of Life Brief; YCCHB, Youth Culture and Competence Hassles Battery.

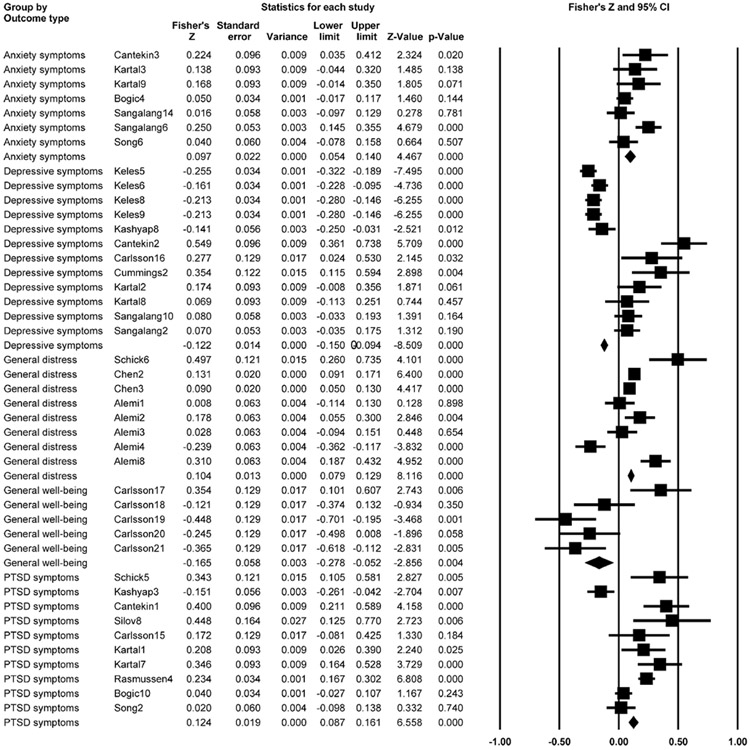

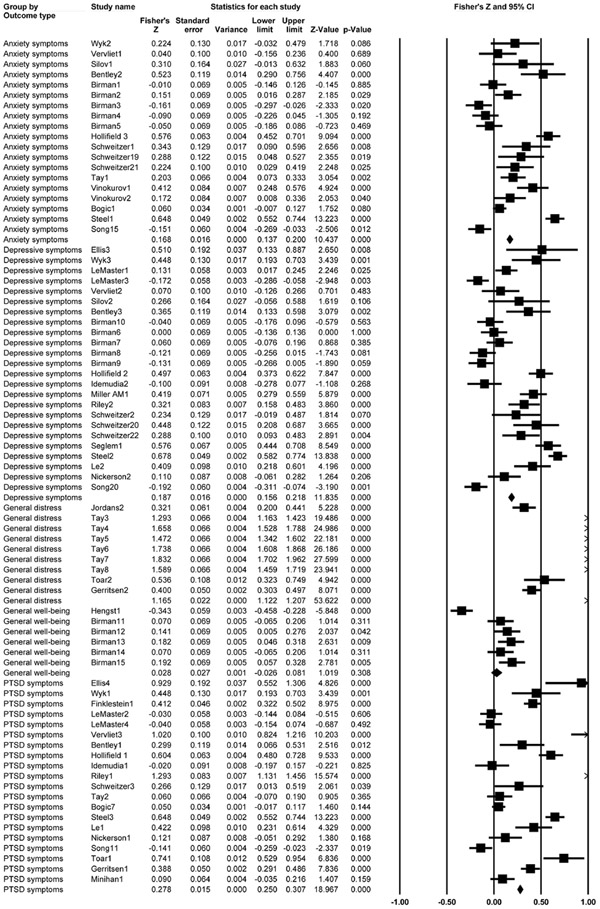

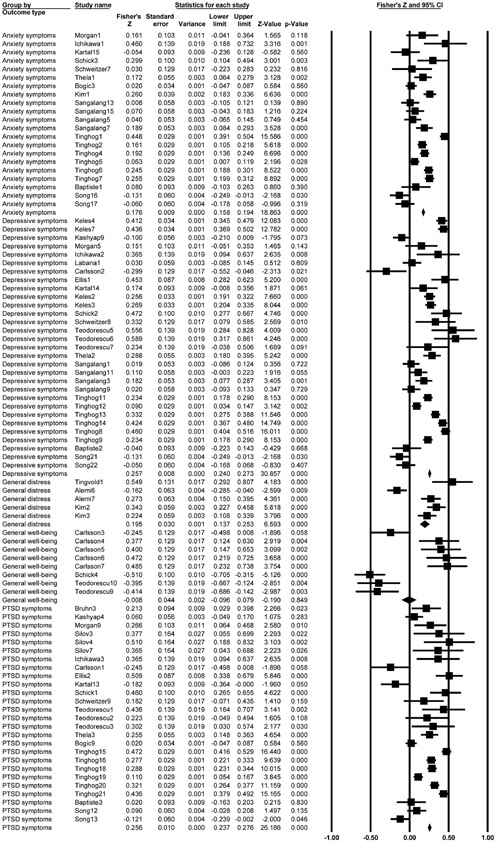

Overall, unfavorable everyday life experiences were associated with mental health outcomes in aggregate (Zr=0.177, 95% CI=0.145, 0.209, Z=10.867, p<0.001). The effect sizes (Zr) ranged from 0.083 between material daily stressors and PTSD symptoms to 1.205 between mixed daily stressors and general distress (Table 2). Grouping of pooled effect sizes revealed that mixed daily stressors had the strongest association with mental health outcomes followed by interpersonal daily stressors (Figure 2a-2d). Of note, subjective daily stressors were positively associated with anxiety symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and general distress (Zr=0.106-0.182, 95% CI=0.019-0.069, 0.190-0.296, p=0.002-0.017); the association with depressive symptoms was not significant (Zr=0.023, p=0.682). Interpersonal daily stressors were positively associated with anxiety, depressive, and PTSD symptoms (Zr=0.158-0.244, 95% CI=0.073-0.150, 0.202-0.298, p<.001) and general distress (Zr=0.233, 95% CI= 0.026, 0.440, p=0.028). Material daily stressors were positively associated with PTSD symptoms (Zr=0.083, 95% CI=0.021, 0.146, p=0.009). Its associations with anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and general distress were not significant (Zr=0.063, 0.059, and −0.002, p=0.084, 0.227, and 0.981). Mixed daily stressors were positively associated with anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and general distress (Zr=0.190-1.205, 95% CI=0.067-0.788, 0.314-1.623, p<0.01). All associations with general well-being were non-significant (Zr=−0.165 to 0.050, p=0.242 to 0.958). The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Meta-analyses of the associations between everyday life experiences and mental health

| Effect sizes | Publication bias (95% CI), p-value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Outcome | k | Zr (95% CI) | p |

I2 (%) |

Classic fail-safe N |

Egger’s regression intercept |

| Unfavorable everyday life experiences (overall) | Anxiety symptoms | 67 | 0.126(0.084, 0.168) | <0.001 | 89.7 | 15410 | −0.161(−1.301, 0.978) |

| Depressive symptoms | 93 | 0.143(0.090, 0.196) | <0.001 | 95.2 | p=0.781 | ||

| Post-traumatic stress symptoms | 89 | 0.199(0.151, 0.247) | <0.001 | 93.4 | |||

| General distress | 24 | 0.542(0.332, 0.752) | <0.001 | 99.2 | |||

| General wellbeing | 26 | −0.010(−0.121,0.100) | 0.853 | 87.4 | |||

| Subjective daily stressors | Anxiety symptoms | 7 | 0.115(0.040,0.190) | 0.003 | 61.2 | 349 | 1.216 (−0.798, 3.231) |

| Depressive symptoms | 12 | 0.023(−0.086,0.132) | 0.682 | 92.4 | p=0.230 | ||

| Post-traumatic stress symptoms | 10 | 0.182(0.069, 0.296) | 0.002 | 86.3 | |||

| General distress | 8 | 0.106(0.019, 0.193) | 0.017 | 88.1 | |||

| General wellbeing | 5 | −0.165(−0.441,0.112) | 0.242 | 83.2 | |||

| Interpersonal daily stressors | Anxiety symptoms | 21 | 0.158(0.073, 0.202) | <0.001 | 90.8 | 16930 | −1.728 (−3.166, −0.289) |

| Depressive symptoms | 30 | 0.213(0.148, 0.277) | <0.001 | 92.6 | p=0.019 | ||

| Post-traumatic stress symptoms | 26 | 0.224(0.150, 0.298) | <0.001 | 91.6 | |||

| General distress | 5 | 0.233(0.026, 0.440) | 0.028 | 91.7 | |||

| General wellbeing | 8 | 0.020(−0.298, 0.339) | 0.901 | 92.4 | |||

| Material daily stressors | Anxiety symptoms | 20 | 0.063(−0.008, 0.135) | 0.084 | 85.9 | 3966 | −1.858(−3.229, −0.487) |

| Depressive symptoms | 27 | 0.059(−0.048, 0167) | 0.277 | 94.9 | p=0.008 | ||

| Post-traumatic stress symptoms | 33 | 0.083(0.021, 0.146) | 0.009 | 88.7 | |||

| General distress | 2 | −0.002(−0.144,0.141) | 0.981 | 80.1 | |||

| General wellbeing | 7 | 0.004(−0.155, 0.164) | 0.958 | 67.4 | |||

| Mixed daily stressors | Anxiety symptoms | 1.864 (−2.978, 6.706) | |||||

| 19 | 0.190(0.067, 0.314) | 0.003 | 92.9 | 13450 | p=0.446 | ||

| Depressive symptoms | 24 | 0.205(0.083, 0.327) | 0.001 | 93.3 | |||

| Post-traumatic stress symptoms | 20 | 0.369(0.214, 0.525) | <0.001 | 96.3 | |||

| General distress | 9 | 1.205(0.788,1.623) | <0.001 | 98.9 | |||

| General wellbeing | 6 | 0.050(−0.126, 0.227) | 0.577 | 90.7 | |||

Note. k, number of effect sizes; Zr, Fisher’s Z transformed correlation coefficient; CI, confidence interval; I2, Higgins I2 statistics.

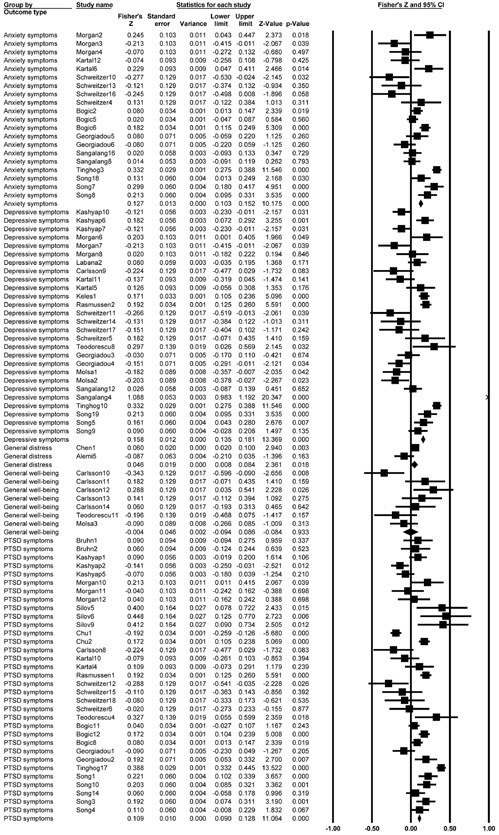

Figure 2a.

Forest plots of the pooled effect sizes between mental health outcomes and subjective daily stressors.

Figure 2d.

Forest plots of the pooled effect sizes between mental health outcomes and mixed daily stressors.

Publication bias between each exposure variable and all outcomes were tested. There was publication bias detected for the association between subjective daily stressors and depressive symptoms (Egger’s regression intercept=7.178, 95% CI=4.430, 9.925, t=5.821, p<0.001), between material daily stressors and anxiety symptoms (Egger’s regression intercept=−2.884, 95% CI=−5.310, −0.460, t=2.499, p=0.022), between material daily stressors and depressive symptoms (Egger’s regression intercept=−4.150, 95% CI=−7.935, −0.365, t=2.258 p=0.033), and between mixed daily stressors and general well-being (Egger’s regression intercept=44.920, 95% CI=30.069, 59.771, t=8.398, p=0.001), suggesting the possibility that only significant findings were reported and published. Otherwise, publication bias was not evident (Egger’s test, p=0.781) (Supplementary Material 2). Classic fail-safe N test revealed that a minimum of 349, 3966, and 13450 studies are needed to render p-value insignificant for subjective daily stressors, material daily stressors and mixed daily stressors respectively. Trimming 84 effect sizes using Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method, the adjusted overall effect size was relatively unaffected (Adjusted Zr=0.301, 95% CI=0.268, 0.334, Q=12078.02).

Moderator Analyses

A high degree of heterogeneity (Q=7209.920, I2=95.867%) was detected across studies, necessitating meta-regression analysis to determine factors contributing to the variation (Table 3). Of the ten meta-regression models we tested, between-study variances were accounted for by sample type (2%), time since trauma exposure (5%), time since migration (9%), type of unfavorable everyday life experiences (13%), type of daily routines (1%), type of mental health outcomes (15%), age group (2%), and type of host countries (18%). Of the four types of everyday life experiences, mixed daily stressors had a greater change in slope relative to other types of daily stressors (β=−0.289 to −0.165, 95% CI=−0.383 to −0.195, −0.258 to −0.071, p<0.001). General distress had a greater change in slope relative to PTSD symptoms (β=0.337, 95% CI=0.201, 0.473, p<0.001). A greater change in slope was found in children and adolescents relative to adults (β=0.283, 95% CI=0.053, 0.515, p<0.016). A greater change in slope was also found in developing host countries relative to developed host countries (β=0.485, 95% CI=0.360, 0.610, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Meta-regression of potential moderators in relation to effect sizes

| Variable | Coefficient (95% CI) | p | R2 analog |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Intercept | 0.183 (0.143, 0.223) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Longitudinal | −0.049 (−0.164, 0.067) | 0.408 | |

| Cross-sectional | Reference | ||

| Model 2 | |||

| Intercept | 0.200 (0.156, 0.244) | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| Asylum seeker | −0.034 (−0.151, 0.084) | 0.573 | |

| Refugee and asylum seeker | −0.102 (−0.204, 0.0005) | 0.051 | |

| Immigrants | −0.148 (−0.427, 0.132) | 0.301 | |

| Refugee | Reference | ||

| Model 3 | |||

| Intercept | −0.087 (−0.394, 0.220) | 0.577 | 0.05 |

| Time since trauma (Continuous) | 0.001 (−0.0008, 0.003) | 0.231 | |

| Model 4 | |||

| Intercept | −0.017 (−0.265, 0.231) | 0.893 | 0.09 |

| Time since migration (Continuous) | 0.0009 (−0.0007, 0.003) | 0.276 | |

| Model 5 | |||

| Intercept | 0.139 (0.104 to 0.174) | <0.001 | 0.18 |

| Host country: Developing country | 0.485 (0.360 to 0.610) | <0.001 | |

| Host country: Developed country | Reference | ||

| Model 6 | |||

| Intercept | 0.3500 (0.282, 0.418) | <0.001 | 0.13 |

| Subjective daily stressors | −0.266 (−0.381, −0.150) | <0.001 | |

| Interpersonal daily stressors | −0.165 (−0.258, −0.071) | <0.001 | |

| Materials daily stressors | −0.289 (−0.383, −0.195) | <0.001 | |

| Mixed daily stressors | Reference | ||

| Model 7 | |||

| Intercept | 0.127 (0.066, 0.189) | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Secondary routines | −0.044 (−0.123, 0.036) | 0.282 | |

| Primary routines | Reference | ||

| Model 8 | |||

| Intercept | 0.202 (0.139, 0.266) | <0.001 | 0.15 |

| Anxiety symptoms | −0.077 (−0.174, 0.020) | 0.118 | |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.059 (−0.147, 0.030) | 0.195 | |

| General distress | 0.337 (0.201, 0.473) | <0.001 | |

| General well-being | −0.213 (−0.350, −0.077) | 0.002 | |

| PTSD symptoms | Reference | ||

| Model 9 | |||

| Intercept | 0.162 (0.121 to 0.203) | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| Children and adolescents | 0.283 (0.053 to 0.514) | 0.016 | |

| Adults (aged > 18 years) | Reference | ||

| Model 10 | |||

| Intercept | 0.075 (−0.072, 0.222) | 0.318 | 0 |

| Male Sex | 0.0004 (−0.002, 0.003) | 0.735 | |

| Female Sex | Reference |

Note. The Fisher’s Zr between study-wise predictor and outcome variables was the dependent variable in the meta-regression models. The moderators were analyzed as categorical or continuous covariates as appropriate.

The moderation analysis found that sample type, type of unfavorable everyday life experiences, type of daily routines, type of mental health outcomes, age group, and type of host countries moderated the effect sizes between everyday life experiences and mental health outcomes. Study design, type of daily routines, time since trauma exposure, time since migration, and sex did not moderate the association between any of category of everyday life experiences and mental health (Table 3).

Mediator Analyses

The results of the mediator analyses are summarized in Table 4. The positive association between prior traumatic exposure and aggregated poor mental health (symptoms and general distress) was fully mediated by subjective, interpersonal, material daily stressors, and primary routines (indirect effects: estimates=0.010-0.038, 95% CI=0.000-0.023, 0.021-0.056). The association was partially mediated by mixed daily stressors (indirect effect: estimates=0.038, 95% CI=0.021, 0.059). The positive association between prior trauma and subsequent PTSD symptoms were fully mediated by subjective daily stressors (indirect effects: estimate=0.035, 95% CI=0.007, 0.080). The positive association between prior traumatic exposure and subsequent anxiety, depressive and PTSD symptoms was fully mediated by interpersonal daily stressors (indirect effects: estimates=0.017-0.050, 95% CI=0.003-0.019, 0.038-0.100). The positive associations between prior trauma and subsequent anxiety and PTSD symptoms were fully mediated by primary routines (anxiety symptoms: estimate=0.009, 95% CI=0.001, 0.021; PTSD symptoms: estimate=0.026, 95% CI=0.010, 0.048). The positive associations between prior traumatic exposure and subsequent depression, PTSD symptoms, and general distress were partially mediated by mixed daily stressors (indirect effects: estimates=0.011-0.081, 95% CI=0.001-0.038, 0.026-0.144). The mediator analyses suggested that unfavorable everyday life experiences in the host countries could have stronger impact on mental health relative to prior trauma exposure among forced migrants.

Table 4.

Meta-analytic structural equation modeling of potential mediating effects

| k | N | IV to DV | Mediator to DV | IV to Mediator | Indirect effect | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Lower | Upper | Estimate | Lower | Upper | Estimate | Lower | Upper | Estimate | Lower | Upper | |||

| Anxiety symptoms (DV) | ||||||||||||||

| Subjective daily stressors | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Interpersonal daily stressors | 14 | 3936 | 0.083 | −0.055 | 0.221 | 0.208 | 0.094 | 0.321 | 0.082 | 0.012 | 0.152 | 0.017 | 0.003 | 0.038 * |

| Materials daily stressors | 19 | 5234 | −0.027 | −0.150 | 0.097 | 0.205 | 0.117 | 0.292 | 0.047 | −0.020 | 0.113 | 0.010 | −0.004 | 0.026 |

| Mixed daily stressors | 18 | 3700 | 0.193 | 0.060 | 0.325 | 0.081 | −0.072 | 0.231 | 0.205 | 0.088 | 0.322 | 0.017 | −0.017 | 0.054 |

| Primary routines | 11 | 3544 | −0.029 | −0.205 | 0.146 | 0.104 | 0.032 | 0.176 | 0.083 | 0.013 | 0.153 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.021 * |

| Secondary routines | 12 | 3249 | 0.092 | −0.037 | 0.221 | 0.227 | 0.122 | 0.333 | −0.022 | −0.091 | 0.047 | −0.005 | −0.024 | 0.011 |

| Depression symptoms (DV) | ||||||||||||||

| Subjective daily stressors | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Interpersonal daily stressors | 21 | 6533 | 0.049 | −0.077 | 0.174 | 0.207 | 0.130 | 0.283 | 0.186 | 0.096 | 0.276 | 0.039 | 0.019 | 0.066 * |

| Materials daily stressors | 22 | 5467 | −0.021 | −0.125 | 0.081 | 0.251 | 0.191 | 0.311 | 0.040 | −0.060 | 0.140 | 0.010 | −0.015 | 0.037 |

| Mixed daily stressors | 22 | 3667 | 0.100 | 0.020 | 0.179 | 0.071 | 0.007 | 0.135 | 0.159 | 0.061 | 0.258 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.026 # |

| Primary routines | 12 | 3166 | −0.039 | −0.213 | 0.135 | 0.211 | 0.155 | 0.267 | 0.055 | −0.039 | 0.149 | 0.012 | −0.008 | 0.034 |

| Secondary routines | 20 | 4482 | −0.013 | −0.053 | 0.024 | 0.193 | 0.138 | 0.249 | 0.101 | −0.028 | 0.229 | 0.019 | −0.005 | 0.049 |

| PTSD symptoms (DV) | ||||||||||||||

| Subjective daily stressors | 8 | 2715 | 0.203 | −0.050 | 0.455 | 0.248 | 0.081 | 0.412 | 0.142 | 0.025 | 0.258 | 0.035 | 0.007 | 0.080 * |

| Interpersonal daily stressors | 15 | 2652 | −0.010 | −0.124 | 0.100 | 0.358 | 0.233 | 0.484 | 0.141 | 0.036 | 0.245 | 0.050 | 0.013 | 0.100 * |

| Materials daily stressors | 27 | 8818 | −0.024 | −0.126 | 0.077 | 0.263 | 0.191 | 0.334 | 0.050 | −0.004 | 0.103 | 0.013 | −0.001 | 0.029 |

| Mixed daily stressors | 19 | 4469 | 0.192 | 0.029 | 0.350 | 0.253 | 0.115 | 0.386 | 0.320 | 0.189 | 0.451 | 0.081 | 0.038 | 0.144 # |

| Primary routines | 15 | 6934 | −0.052 | −0.228 | 0.123 | 0.237 | 0.158 | 0.316 | 0.112 | 0.047 | 0.177 | 0.026 | 0.010 | 0.048 * |

| Secondary routines | 20 | 3937 | 0.020 | −0.083 | 0.123 | 0.297 | 0.210 | 0.384 | 0.043 | −0.049 | 0.135 | 0.013 | −0.015 | 0.043 |

| General distress (DV) | ||||||||||||||

| Subjective daily stressors | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Interpersonal daily stressors | 4 | 1100 | −0.369 | −0.504 | −0.267 | 0.356 | 0.151 | 0.576 | 0.165 | −0.019 | 0.348 | 0.059 | −0.006 | 0.176 |

| Materials daily stressors | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mixed daily stressors | 3 | 767 | 0.468 | 0.352 | 0.589 | 0.177 | 0.046 | 0.304 | 0.368 | 0.310 | 0.426 | 0.065 | 0.018 | 0.111 # |

| Primary routines | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Secondary routines | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| General well-being (DV) | ||||||||||||||

| Subjective daily stressors | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Interpersonal daily stressors | 10 | 663 | −0.021 | −0.216 | 0.178 | −0.269 | −0.557 | 0.020 | 0.016 | −0.253 | 0.286 | −0.004 | −0.109 | 0.096 |

| Materials daily stressors | 8 | 565 | −0.007 | −0.110 | 0.097 | −0.065 | −0.541 | 0.410 | 0.005 | −0.142 | 0.153 | 0.000 | −0.045 | 0.040 |

| Mixed daily stressors | 6 | 1354 | −0.035 | −0.096 | 0.025 | 0.014 | −0.038 | 0.067 | 0.051 | −0.096 | 0.197 | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.009 |

| Primary routines | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Secondary routines | 17 | 1100 | −0.013 | −0.131 | 0.107 | −0.272 | −0.525 | −0.019 | 0.016 | −0.124 | 0.157 | −0.004 | −0.056 | 0.043 |

| Low Intensity Stressors (overall) | 29 | 2897 | 0.023 | −0.056 | 0.102 | −0.094 | −0.246 | 0.058 | −0.008 | −0.107 | 0.091 | 0.001 | −0.013 | 0.016 |

Note. k, number of study; N, total sample size; IV, Trauma exposure; MV, Daily stressors

Full mediation

Partial mediation; Studies of inadequate sample sizes and/or effect sizes could not be analyzed by Meta-SEM and were marked as “-” in the tables.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis is one of the first to investigate the association of postmigration everyday life experiences with psychiatric symptoms and general distress and well-being among studies in forced migrants following mass conflicts. Subjective daily stressors, defined as perceived emotional distress associated with different daily experiences, was positively associated with anxiety, and PTSD symptoms. Interpersonal (e.g., conflict, discrimination, isolation, lack of emotional support) and mixed daily stressors were positively associated with anxiety, depressive, and PTSD symptoms, and general distress. Material daily stressors (e.g., housing/neighborhood contexts, accommodation difficulties, employment-related issues, access to social or mental health services) was positively associated with PTSD symptoms, general distress, and functional impairment. Moderator analyses revealed that effect sizes were stronger for (1) mixed relative to other types of daily stressors, (2) general distress relative to PTSD symptoms and general well-being, (3) children and adolescents relative to adults, and (4) developing host countries relative to developed host countries. Prior traumatic exposure was associated with higher interpersonal and mixed daily stressors (i.e., low intensity daily stressors), and primary routines, which, in turn, contributed to higher psychiatric symptoms and general distress. Specifically, interpersonal daily stressors and primary routines demonstrated consistent full mediation on the associations of past trauma with anxiety and PTSD symptoms.

Previous research consistently shows that early life and traumatic exposures are associated with psychiatric morbidity. However, among forced migrants who are refugees, asylum seekers, or immigrants who have settled in, unfavorable everyday life experiences in the receiving context could have stronger impact on their mental health relative to prior conflicted-related trauma. This has reaching impacts for policy and intervention, since the present findings focus us on environment rather than person-level intervention.

Our findings suggest the need to evaluate the impact of different types of unfavorable everyday life experiences on mental health in post-migration contexts. Previous studies have identified positive, inverse, and null correlations between perceived daily stressors and mental health among conflict-affected forced migrants (e.g., Kartal and Kiropoulos, 2016; LeMaster et al., 2018; Morville et al., 2015; Seglem et al., 2014). The equivocal results could be due to variations in the measurement of daily stressors. Overall, we found consistent positive associations of subjective, interpersonal, and mixed daily stressors with psychiatric symptoms and general distress but a weak association between material daily stressors and PTSD symptoms (0.083). Stronger effect sizes were found between mixed daily stressors and mental health outcomes (0.222 to 0.811). Publication bias was identified in the material-PTSD association, suggesting the possibility that only significant findings were reported and published. Two possible reasons could explain the findings. First, our analysis was conducted with data from different groups of conflict-affected forced migrants, including immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. In addition, the measures of material daily stressors assessed a wide range of material issues, such as housing and poor neighborhoods, unemployment, and access to community services. Therefore, it is possible that material stressors could have strong associations with mental health among subgroup(s) only. Second, material issues have been highlighted as one of the top priorities for humanitarian aid to forced migrants affected by conflicts, and well-defined systems have been developed and implemented successfully by non-profit organizations and host countries (Natsios, 1995; Akhtar et al., 2012). Despite considerable awareness and attention on addressing psychological and interpersonal needs of conflict-affected migrants, the focus on strengthening psychosocial support is new relative to proving material aid (Ventevogel et al., 2015). Therefore, psychological and interpersonal daily stressors instead of material issues could remain to be the key correlates of poor mental health among forced migrants.

The consistent associations of daily stressors with general distress also highlighted the importance of conceptualizing and assessing mental health of forced migrants as a continuum from the absence of poor mental health to the presence of mental health or well-being (Antonovsky, 1987; Bonanno, 2004; Keyes, 2002; Patel et al., 2018). Conceptualizing mental health in this way confers a strength-based approach for assessing and intervening on people affected by conflict. Stressful experiences’ association with general distress, together with specific psychiatric disorders can be better utilized for explaining not only clinically significant psychological distress but also risk of poorer adjustment and psychological resilience. Nevertheless, the effect sizes between general well-being and outcomes were non-significant across seven studies using validated quality of life (QoL) measures. More research is needed to assess specific domains of well-being among forced migrants.

This study is one of the first comprehensive quantitative reviews on everyday adaptation among forced migrants based on existing theoretical frameworks. The current review supports the Daily Stressor Model by showing that daily stressors have higher associations with poor mental health than past trauma, and mediate the association between past trauma and current poor mental health (Miller and Rasmussen, 2010, 2014). This supports previous studies that showed associations between prior traumatic exposure and mental health outcomes were non-significant after considering the effects of daily stressors (Miller et al., 2008; Rasmussen and Annan, 2009; Rasmussen et al., 2010). Trauma is a necessary but not sufficient condition for PTSD. Many forced migrants exposed to traumatic events do not have PTSD or poor mental health, while others do. Exposure to daily stressors may be a salient and proximal cause accounting for this variation in outcomes. By summarizing all relevant studies up to the end of 2018, we suggest that while the adverse impact of prior trauma on mental health remains important, its adverse impact is likely to be indirect through worsening different aspects of daily living, mainly subjective distress and interpersonal interactions.

Daily Stressor Model proposed two categories of daily stressors, namely low intensity stressors and potentially traumatic stressors (Miller and Rasmussen, 2010, 2014). The Drive to Thrive theory added to the Model by providing further conceptualization, differentiation, and elaboration on primary and secondary routines on top of low-intensity stressors (Hou et al., 2018). Daily Stressor Model conceptualized a broad range of daily stressors that could be applicable and generalizable to diverse conflicted affected or post-migration settings, whereas Drive to Thrive theory provided a framework of reference for developing more specific assessment of individual dimensions of everyday adaptation and thus scalable intervention (Hou et al., 2019).

Supportive stepped-care approaches in emergency settings begin with establishing governance and services for addressing basic physical needs, followed by facilitating access to support from family or the wider community for improving psychosocial well-being, before focused psychiatric services are implemented (Hassan et al., 2015). Consistent with the Drive to Thrive theory (Hou et al., 2018, 2019) and previous evidence (Doğan and Kahraman, 2011; Hou et al., 2019), primary routines consistently fully mediated the positive associations of prior traumatic exposure with anxiety, depressive, and PTSD symptoms. The findings suggest the value of differentiating between primary and secondary routines in understanding the everyday adaptation of people affected by conflicts. The literature on daily hassles and uplifts highlighted the associations of subjective daily stressors with psychological distress and well-being (Almeida, 2005; Charles et al., 2013; Harkness and Monroe, 2016; Totenhagen et al., 2012). Daily hassles and uplifts, defined as overall negative (i.e., hassles) and positive (i.e., uplifts) emotions of a variety of daily experiences, and their associations with psychological distress and well-being have been intensively studied across different populations in previous decades. Emotion ratings in terms of different social partners (e.g., family, friends, coworkers), thoughts and feelings (e.g., job security, intimacy), activities (e.g., yardwork), environment (e.g., weather), and objects (e.g., television) are aggregated to reflect hassles or uplifts. There has also been very solid work on assessing practical living difficulties that forced migrants face, such as not being able to find work, little support from host government, and separation from family, and how the difficulties impact mental health following migration (e.g., Schick et al., 2018; Silove et al., 1997). Limited research has categorized the events into meaningful domains such as eating and sleep that are more basic and necessary than leisure and social activities.

Our findings suggest a focus on upholding primary, basic daily routines, including diet, sleep, hygiene, and household maintenance, in aid of psychological adaptation among forced migrants (Hou et al., 2018, 2019). Such alternative dimension is also supported by frameworks and evidence from other populations. Poorer mental health among older adults who faced the stress of physical decline, disability, and bereavement could be attributable to loss of control and consistency over important daily life tasks (Schulberg et al., 2000; Zautra et al., 1990). Lifestyle interventions focusing on healthy diet and sleep have been demonstrated to be effective in preventing or ameliorating depressive symptoms (Olivan-Blázquez et al., 2018; Sarris et al., 2014).

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered in the interpretations of the present findings. First, a small sample size was analyzed for asylum seekers (n=1,755), relative to other populations (n=10,680, 2,054, and 3,274). These studies assessed the associations between mixed daily stressors and depressive symptoms and between mixed daily stressors and generic stress (Betancourt et al., 2010; Ertl et al., 2014; Jordans et al., 2012). Second, mental health was indicated by anxiety, depressive, and PTSD symptoms, general distress, and general well-being. A large body of literature has highlighted the pitfall of privileging psychological distress as the most important mental health outcome without also considering subjective well-being and quality of life (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Weich et al., 2011). We identified just a handful of studies assessing psychological well-being. Our analyses showed that none of the daily stressors were associated with psychological well-being. These findings need to be replicated in different populations. Third, all studies used self-report instruments for assessing everyday life experiences, and only 10 out of the 59 studies reported longitudinal associations. Cross-sectional designs might overestimate the associations under study (Stone and Shiffman, 2002). Fourth, traumatic daily stressors such as intimate partner violence could be highly relevant to the daily adaptation of forced migrants and mediate the effects of other everyday life experiences on mental health. Future studies could investigate how differential unfavorable everyday life experiences are interrelated with each other and jointly impact mental health among forced migrants.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the limitations, this meta-analysis highlights unfavorable everyday life experiences of forced migrants should not be considered as a unitary dimension especially in terms of timing of mental health screening and administration of strength-based psychosocial support. Ratings of poor living conditions could be more strongly associated with psychiatric disorders especially PTSD. Our findings also provide one of the first quantitative meta-analytic evidence supporting existing theoretical frameworks on everyday adaptation among forced migrants after mass conflicts. Based on this review, future strength-based interventions aimed at consolidating and enhancing basic, necessary daily routines, including personal and family hygiene, diet and sleep, and improving living conditions, could have a significant positive impact on their mental health in the receiving countries.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material 1. Definition and measurement scales for predictors and outcomes in the included studies.

Supplementary Material 2. Begg’s funnel plots of the pooled effect sizes between mental health outcomes and (a) Overall, (b) subjective daily stressors, (c) interpersonal daily stressors, (d) material daily stressors, and (e) mixed daily stressors.

Figure 2b.

Forest plots of the pooled effect sizes between mental health outcomes and interpersonal daily stressors.

Figure 2c.

Forest plots of the pooled effect sizes between mental health outcomes and material daily stressors.

Highlights.

This is the first quantitative review on daily adaptation in forced migrants.

Unfavorable daily experiences in the receiving context impact mental health.

Daily experiences of forced migrants are multidimensional in term of mental health.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This research was supported by the Fulbright-RGC Hong Kong Senior Research Scholar Award from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong SAR, China (R9401) awarded to Wai-Kai Hou and an NIH grant R01MH091034 awarded to George A. Bonanno. The Fulbright-RGC Hong Kong Award was in collaboration with the Consulate General of the United States in Hong Kong.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Declarations of interest:

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Wai Kai Hou, Laboratory of Psychology and Ecology of Stress (LoPES), Department of Psychology, Centre for Psychosocial Health, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Huinan Liu, Laboratory of Psychology and Ecology of Stress (LoPES), Department of Psychology, Centre for Psychosocial Health, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Li Liang, Laboratory of Psychology and Ecology of Stress (LoPES), Department of Psychology, Centre for Psychosocial Health, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Jeffery Ho, Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Hyojin Kim, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York NY, USA.

Eunice Seong, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York NY, USA.

George A. Bonanno, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York NY, USA

Stevan E. Hobfoll, STAR Consultants-STress, Anxiety and Resilience, Chicago, IL, USA

Brian J. Hall, Department of Psychology, University of Macau, Macau SAR, China

References

- Akhtar P, Marr NE, Garnevska EV, 2012. Coordination in humanitarian relief chains: chain coordinators. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag 2, 85–103. 10.1108/20426741211226019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alemi Q, Stempel C, 2018. Discrimination and distress among Afghan refugees in northern California: The moderating role of pre- and post-migration factors. PLoS One 13, e0196822 10.1371/journal.pone.0196822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, 2005. Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci 14, 64–68. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A, 1987. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes MM, Maas I, Wilms H-U, Borchelt M, Little TD, 1999. Everyday Competence in Old and Very Old Age: Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Findings, in: Baltes PB, Mayer KU (Eds.), The Berlin Aging Study., New York, pp. 384–402. [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste VM, 2017. The Impact of Stigma on the Mental Health of Resettled African and Asian Refugees. ProQuest Diss. Theses [Google Scholar]

- Bentley JA, Thoburn JW, Stewart DG, Boynton LD, 2012. Post-Migration Stress as a Moderator Between Traumatic Exposure and Self-Reported Mental Health Symptoms in a Sample of Somali Refugees. J. Loss Trauma 17, 452–469. 10.1080/15325024.2012.665008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Agnew-Blais J, Gilman SE, Williams DR, Ellis BH, 2010. Past horrors, present struggles: The role of stigma in the association between war experiences and psychosocial adjustment among former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Soc. Sci. Med 70, 17–26. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Tran N, 2008. Psychological Distress and Adjustment of Vietnamese Refugees in the United States: Association With Pre- and Postmigration Factors. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 78, 109–120. 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogic M, Ajdukovic D, Bremner S, et al. , 2012. Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: Refugees from the former Yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK. Br. J. Psychiatry 200, 216–223. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogic M, Njoku A, Priebe S, 2015. Long-term mental health of war-refugees: a systematic literature review. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 15, 29 10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boker S, Neale M, Maes H, et al. , 2011. OpenMx: An Open Source Extended Structural Equation Modeling Framework. Psychometrika. 76, 306–317. 10.1007/s11336-010-9200-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, 2004. Loss, Trauma, and Human Resilience: Have We Underestimated the Human Capacity to Thrive after Extremely Aversive Events? Am. Psychol 59, 20–28. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein I, Montgomery P, 2011. Psychological Distress in Refugee Children: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev 14, 44–56. 10.1007/s10567-010-0081-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn M, Rees S, Mohsin M, Silove D, Carlsson J, 2018. The range and impact of postmigration stressors during treatment of trauma-affected refugees. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 206, 61–68. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantekin D, Gençöz T, 2017. Mental Health of Syrian Asylum Seekers in Turkey: The Role of Pre-Migration and Post-Migration Risk Factors. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol 36, 835–859. 10.1521/jscp.2017.36.10.835 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson JM, Olsen DR, Mortensen EL, Kastrup M, 2006. Mental health and health-related quality of life: A 10-year follow-up of tortured refugees. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 194, 725–731. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243079.52138.b7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Piazza JR, Mogle J, Sliwinski MJ, Almeida DM, 2013. The Wear and Tear of Daily Stressors on Mental Health. Psychol. Sci 24, 733–741. 10.1177/0956797612462222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Hall BJ, Ling L, Renzaho AM, 2017. Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 4, 218–229. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30032-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung MWL, 2015. metaSEM: An R package for meta-analysis using structural equation modeling. Front. Psychol 5, 1521 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung MWL, Chan W, 2005. Meta-analytic structural equation modeling: A two-stage approach. Psychol. Methods 10, 40–64. 10.1037/1082-989X.10.1.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu T, Keller AS, Rasmussen A, 2013. Effects of post-migration factors on PTSD outcomes among immigrant survivors of political violence. J. Immigr. Minor. Heal 15, 890–897. 10.1007/s10903-012-9696-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings S, Sull L, Davis C, Worley N, 2011. Correlates of depression among older kurdish refugees. Soc. Work. 56, 159–168. 10.1093/sw/56.2.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doğan A, Kahraman R 2011. Emergency and disaster interpreting in Turkey: ten years of a unique endeavour. J. of Faculty of Letters of Hacettepe University, 28, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BH, MacDonald HZ, Klunk-Gillis J, Lincoln A, Strunin L, Cabral HJ, 2010. Discrimination and mental health among somali refugee adolescents: The role of acculturation and gender. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 80, 564–575. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BH, Miller AB, Abdi S, Barrett C, Blood EA, Betancourt TS, 2013. Multi-tier mental health program for refugee youth. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 81, 129–140. 10.1037/a0029844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl V, Pfeiffer A, Schauer-Kaiser E, Elbert T, Neuner F, 2014. The challenge of living on: Psychopathology and its mediating influence on the readjustment of former child soldiers. PLoS One. 9, e102786 10.1371/journal.pone.0102786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel M, 2018. Psychological and psychosocial interventions for refugee children resettled in high-income countries. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci 27, 117–123. 10.1017/S2045796017000695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel M, Reed RV, Panter-Brick C, Stein A, 2012. Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: Risk and protective factors. Lancet. 379, 266–282. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J, 2005. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: A systematic review. Lancet. 365, 1309–1314. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finklestein M, Laufer A, Solomon Z, 2012. Coping strategies of Ethiopian immigrants in Israel: Association with PTSD and dissociation. Scand. J. Psychol 53, 490–498. 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00972.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadou E, Zbidat A, Schmitt GM, Erim Y, 2018. Prevalence of mental distress among Syrian refugees with residence permission in Germany: A registry-based study. Front. Psychiatry 9, 393 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen AAM, Bramsen I, Devillé W, vanWilligen LHM, Hovens JE, van derPloeg HM, 2006. Physical and mental health of Afghan, Iranian and Somali asylum seekers and refugees living in the Netherlands. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol 41, 18–26. 10.1007/s00127-005-0003-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Monroe SM, 2016. The assessment and measurement of adult life stress: Basic premises, operational principles, and design requirements. J. Abnorm. Psychol 125, 727–745. 10.1037/abn0000178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan G, Kirmayer L, Mekki- Berrada A, et al. , 2015. Culture, Context and the Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing of Syrians: A review for mental health and psychosocial support staff working with Syrians affected by armed conflict. UNHCR: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Hengst SMC, Smid GE, Laban CJ, 2018. The effects of traumatic and multiple loss on psychopathology, disability, and quality of life in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 206, 52–60. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield M, Eckert V, Warner TD, et al. , 2005. Development of an inventory for measuring war-related events in refugees. Compr. Psychiatry 46, 67–80. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield M, Warner T, Krakow B, Westermeyer J, 2018. Mental Health Effects of Stress over the Life Span of Refugees. J. Clin. Med 7, 25 10.3390/jcm7020025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou WK, Hall BJ, Hobfoll SE, 2018. Drive to Thrive: A Theory of Resilience Following Loss, in: Morina N, Nickerson A (Eds.), Mental Health of Refugee and Conflict-Affected Populations. Springer, Cham, pp. 111–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hou WK, Lai FTT, Hougen C, Hall BJ, Hobfoll SE, 2019. Measuring everyday processes and mechanisms of stress resilience: Development and initial validation of the sustainability of living inventory (SOLI). Psychol. Assess 31, 715–729. 10.1037/pas0000692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Development Reports, 2018. United Nations Development Programme. http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/137506 (accessed 23 October 2019).

- Hynie M, 2018. The Social Determinants of Refugee Mental Health in the Post-Migration Context: A Critical Review. Can. J. Psychiatry 63, 297–303. 10.1177/0706743717746666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa M, Nakahara S, Wakai S, 2006. Effect of post-migration detention on mental health among Afghan asylum seekers in Japan. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 40, 341–346. 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01800.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idemudia ES, William JK, Boehnke K, Wyatt G, 2013. Gender Differences in Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms among Displaced Zimbabweans in South Africa. J. Trauma. Stress Disord. Treat 2, 1340 10.4172/2324-8947.1000110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordans MJD, Semrau M, Thornicroft G, VanOmmeren M, 2012. Role of current perceived needs in explaining the association between past trauma exposure and distress in humanitarian settings in Jordan and Nepal. Br. J. Psychiatry 201, 276–281. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.102137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartal D, Kiropoulos L, 2016. Effects of acculturative stress on PTSD, depressive, and anxiety symptoms among refugees resettled in Australia and Austria. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol 7, 28711 10.3402/ejpt.v7.28711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap S, Page AC, Joscelyne A, 2019. Post-migration treatment targets associated with reductions in depression and PTSD among survivors of torture seeking asylum in the USA. Psychiatry Res. 271, 565–572. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keles S, Friborg O, Idsøe T, Sirin S, Oppedal B, 2015. Depression among unaccompanied minor refugees: The relative contribution of general and acculturation-specific daily hassles. Ethn. Heal 21, 300–317. 10.1080/13557858.2015.1065310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keles S, Friborg O, Idsøe T, Sirin S, Oppedal B, 2018. Resilience and acculturation among unaccompanied refugee minors. Int. J. Behav. Dev 42, 52–63. 10.1177/0165025416658136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, 2002. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav 43, 207–222. 10.2307/3090197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]