To the Editor,

Currently, a significant driver of Ig-E-mediated cross-reactivity between penicillins/cephalosporins is thought to be the R1 side chain, with contemporary cephalosporin cross-reactivity with penicillin allergy occurring at a rate of < 2% 1. However, the extent to which there is cross-reactivity between drugs within the penicillin class in patients with severe delayed and presumed T-cell mediated reactions is unknown.

A prospective multicentre cohort study was performed at Austin Health and Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne Victoria, between 1st April 2015 and 24th February 2019. Study participants included patients referred for testing with a history of a severe T-cell mediated hypersensitivity associated with a penicillin. A penicillin was defined as any drug within the penicillin class and in our cohort included: penicillin VK, penicillin G, flucloxacillin, dicloxacillin, amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, ampicillin or piperacillin-tazobactam.

A severe T-cell mediated hypersensitivity syndrome was defined as drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) or severe maculopapular exanthem (MPE). Patients experiencing Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) associated with a penicillin were excluded. For phenotypes of DRESS and AGEP, a RegiSCAR score of ≥ 4 (probable or definite) and an AGEP score of ≥ 2 respectively were required2, 3. Severe MPE was defined as an extensive cutaneous exanthem with more than 50% of body surface area and RegiSCAR score of 2-3 (possible)2. All cases had at least one antibiotic that had been administered within 5 drug half-lives of onset of rash, a Naranjo score of ≧ 5, phenotype confirmed by dermatologist or histopathology, and had at least three investigations to exclude common alternative causes such as infections or autoimmune diseases.

Both sites are tertiary referral testing centres with established drug and antibiotic allergy testing programs utilizing previously published in vivo (skin prick testing [SPT] and intradermal testing [IDT]) testing protocols including the highest non-irritating drug concentrations where possible4, 5. As previously described, skin testing (SPT/IDT) and patch testing (PT) was performed no earlier than 6 weeks following the resolution of cutaneous manifestations utilizing the previously published method4, 5. The routine IDT panel included: Normal Saline (0.9% solution), penicillin G (1000 IU/ml, 10,000IU/ml), DAP-major (benzylpenicilloyl poly-L-lysine; final concentration 1.07 X10−2 mol/L), minor-determinate mixture (MDM; sodium benzylpenicillin, benzylpenicilloic acid, sodium benzylpenicilloate; 1.5 mg/mL; final concentration 1.5 mol/L), ampicillin (25mg/ml), flucloxacillin (2mg/ml), cefazolin (1mg/ml) and ceftriaxone (2.5mg/ml). Piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5mg/ml) IDT was performed in patients reporting a primary piperacillin-tazobactam allergy or were immunocompromised with a reported penicillin allergy. All test reagents (no excipients) were diluted in water or Normal Saline. Skin test positive was defined as per previous definitions, in brief a delayed IDT was considered positive when an infiltrated erythema with a diameter of greater than 5mm was present as pre previous definition.5 Skin testing utilizing the aforementioned routine IDT panel was performed in 6 healthy controls and patients with a history of IgE mediated penicillin hypersensitivity (Supplementary Table E1).

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from whole heparinised blood of patients at time of IDT. PBMCs were stored at −80°C in 90% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 10% DMSO until IFN-γ release Enzyme Linked ImmunoSpot (ELISpot) assay and DNA extraction was performed as per previously published methods. 6 (Supplementary materials) Ethics approval was obtained from the Austin Health Research Ethics Committee (Approval 15/Austin/75).

During the study period 724 patients completed SPT/IDT or PT for a suspected antibiotic allergy. Among the 724 patients, 1163 antibiotic allergy labels were reported (905 [77.8%] beta-lactam; 680 [58.5%] penicillin). 602 patients (83%) reported penicillin-associated hypersensitivity, 216 with delayed hypersensitivity and 32 with a severe T-cell mediated hypersensitivity. Of these 32 patients with delayed and presumed T-cell mediated hypersensitivity, 14 (44%) were negative to all reagents, 6 (19%) positive to ≤ 2 tested reagents (Supplementary Table E2) and 12 (38%) had a positive intradermal test documented to > 2 reagents from the routine IDT panel (Figure 1, Table 1).

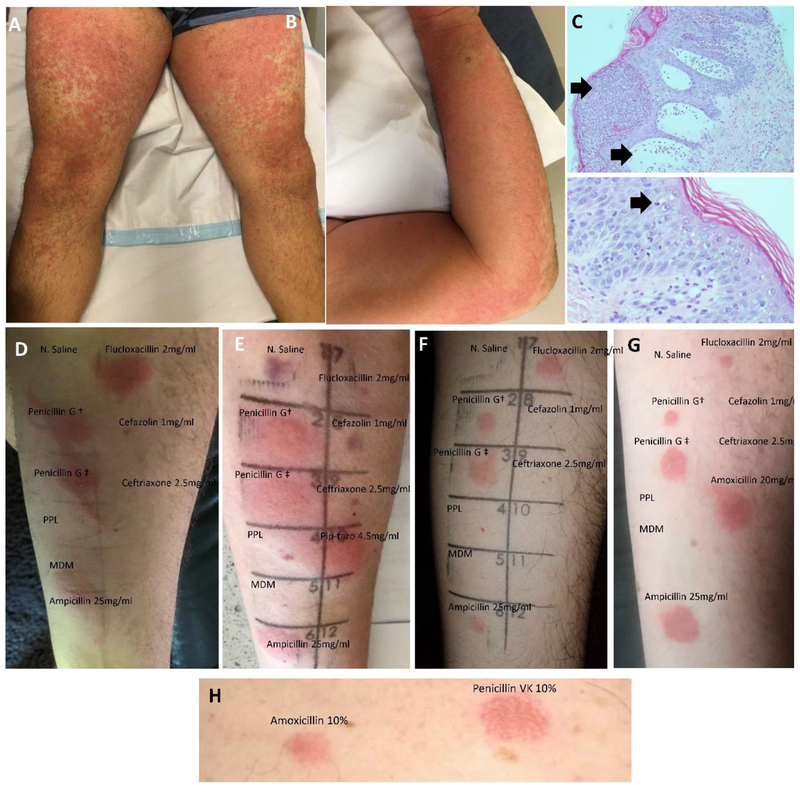

Figure 1.

Pictorial representation of patients reporting penicillin-associated severe T-cell mediated hypersensitivity from tested cohort. Pustular exanthem of a patient with flucloxacillin-associated AGEP [Patient 11] (A-B) with corresponding histopathology demonstrating pustule formation (upper arrow) and upper dermal edema (lower arrow) (low power x10 magnification; upper image) and spongiosis and neutrophil migrating through epidermis [arrow] (high power x100 magnification; lower image) (C). Intradermal testing 24 hours post inoculation showing widespread penicillin cross-reactivity (pustule formation noted on penicillin 1000IU/ml IDT) (D). Further patients with identical pattern of intradermal test cross-reactivity demonstrated in (E [Patient 4], F [Patient 9], G [Patient 1]). Please note that a bruise is noted in Patient E where the Normal Saline was inoculated. Panel H illustrates a Grade 3 positive patch test result from same patient with IDT demonstrated in Panel G (PT performed 6 months following positive IDT) [Patient 1]. Patient 1 IDT was performed with amoxicillin in addition to the standard panel (Panel G) to correlated with patch testing performed to amoxicillin (Panel H).

Abbreviations; PPL, DAP-major (benzylpenicilloyl poly-L-lysine; final concentration 1.07 X10−2 mol/L), MDM, minor-determinate (sodium benzylpenicillin, benzylpenicilloic acid, sodium benzylpenicilloate), Penicillin G†, Penicillin G 1000 IU/mL; PenicillinG ‡, Penicillin G 10000 IU/mL.

Table 1:

Patients with penicillin-associated severe T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity with positive intradermal testing

| No. | Sex/Age | Pre-existing skin disease or medical comorbidities | Phenotype | RegiSCAR score⁞ | Biopsy Compatible* | Primary implicated drug | Time from reaction to testing (days)† | Positive IDT** | Time to positivity | Positive IFN-γ ELISpot | Oral provocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43M | Nil | MPE | 2 | Not performed | Amoxicillin | 6145 | AMP, FLU, PEN, AMX‡^ | ≤ 24 hours | No | Cephalexin |

| 2 | 51F | Nil | DRESS | 4 | Yes | Piperacillin-tazobactam | 473 | AMP, FLU, PEN, PIP-TAZ | ≤ 24 hours | No | Cefuroxime |

| 3 | 38F | Diabetes mellitus | DRESS | 7 | Yes | Piperacillin-tazobactam | 312 | AMP, FLU, PEN, PIP-TAZ | ≤ 24 hours | PIP-TAZ | Cefuroxime |

| 4 | 42F | Hairy cell leukemia | MPE | 2 | No | Piperacillin-tazobactam | 269 | AMP, FLU, PEN, PIP-TAZ | ≤ 24 hours | No# | Cephalexin |

| 5 | 45F | Chronic myelocytic leukemia | MPE | 2 | No | Piperacillin-tazobactam | 318 | AMP, FLU, PEN, PIP-TAZ | ≤ 24 hours | No# | Cefuroxime |

| 6 | 64M | Liver transplant recipient for alcoholic liver disease | MPE | 2 | Not performed | Amoxicillin | 1470 | AMP, FLU, PEN, PIP-TAZ | ≤ 24 hours | AMP | Cephalexin |

| 7 | 38F | Metastatic melanoma^^ | MPE | 3 | Yes | Amoxicillin | 121 | AMP, FLU, PEN, PIP-TAZ | ≤ 24 hours | AMP | Cefuroxime |

| 8 | 34M | Hairy cell leukemia | MPE | 2 | Not performed | Piperacillin-tazobactam | 1146 | AMP, FLU, PEN, PIP-TAZ | ≤ 24 hours | No | Cefuroxime |

| 9 | 25M | Nil | AGEP | - | Yes | Flucloxacillin | 101 | AMP, FLU, PEN^ | ≤ 24 hours | No | Cephalexin |

| 10 | 62M | Follicular lymphoma | DRESS | 4 | Yes | Piperacillin-tazobactam | 1078 | AMP, FLU, PEN, PIP-TAZ | ≤ 24 hours | PIP-TAZ | Cephalexin |

| 11 | 45M | Nil | AGEP | - | Yes | Flucloxacillin | 90 | AMP, FLU, PEN^ | ≤ 24 hours | No | Cephalexin |

| 12 | 31F | Nil | AGEP | - | Yes | Amoxicillin | 3097 | AMP, FLU, PEN^ | ≤ 24 hours | AMP | Not yet performed |

Abbreviations: F; female; M, male; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; MPE, severe maculopapular exanthem; PT, patch testing; IDT, intradermal testing; AMX, amoxicillin; AMP, ampicillin; PEN, Penicillin G, FLU, flucloxacillin; PIP-TAZ, piperacillin-tazobactam; OP, oral provocation; pip-tazo, piperacillin-tazobactam.

RegiSCAR score as per published definitions (<2, no DRESS; 2-3, possible DRESS; 4-5, probable DRESS; ≥ 6 definite DRESS)2

Haemotoxylin and Eosin (H & E) performed as per routine clinical practice

Tested IDT concentrations; Ampicillin 25mg/ml, benzylpenicillin 1000IU/ml, benzylpenicillin 10000IU/ml, flucloxacillin 2mg/ml, piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5mg/ml (amoxicillin 20mg/ml utilized only for Patient 1)

Latency period – time (days) from rash onset to intradermal testing. If year only known, date default 1st of January of implicated year.

Reproduced with patch testing to ampicillin 10%, benzylpenicillin 10%. Performed 6386 days post index reaction - 6 months following positive IDT test.

Piperacillin-tazobactam not tested

melanoma patient on check-point inhibitor

Poor CD3 response reflecting recent cladribine (660) and cytarabine (859) chemotherapy

The patient phenotypes and characteristics of the 12 patients positive to > 2 intradermal test reagents are demonstrated in Table 1. Briefly, the phenotypes were DRESS (3/12; 25%), AGEP (3/12; 25%) and severe MPE (6/12; 50%). The primary implicated penicillins were piperacillin-tazobactam (6, 50%); amoxicillin (4, 33%) and flucloxacillin (2, 17%). The median age was 52.5 years (IQR 36-48), 50% (6/12) female, and 5 (41.6%) immunocompromised (solid organ transplant recipient, cancer, autoimmune/connective tissue disorder requiring immunomodulating therapy). The median time between rash onset and intradermal testing and PBMC sampling was 395.5 days (IQR 195-1308). Positive reactions to IDT occurred as early as 6 hours post inoculation and all patients were positive by 24 hours with persistence of skin redness and induration for greater than 72 hours. No systemic adverse events to skin testing were reported. All patients were positive to tested IDT concentrations of ampicillin, penicillin G and flucloxacillin and negative to 0.9% N. saline, PPL (neat), MDM (neat), cefazolin and ceftriaxone (Figure 1). In patients with piperacillin-tazobactam as the primary implicated drug or immunocompromised, piperacillin-tazobactam IDT was performed and positive in all tested (8/8). A similar delayed pattern was not observed in healthy controls or in 255 patients with immediate IgE mediated hypersensitivity reactions to penicillins (Supplementary Table E1). Eleven of 12 (92%) patients tolerated an oral 1st or 2nd generation cephalosporin provocation after IDT (Table 1). One remaining patient has yet to undergo oral provocation. Five of 12 (41.6%) patients were positive to the primary implicated drug on IFN-γ ELISpot testing (Supplementary Figure E1).

We provide evidence for apparent cross-reactivity within penicillin class drugs by demonstrating penicillin IDT cross-reactivity in patients reporting a penicillin-associated severe T-cell mediated hypersensitivity. The vast majority of these patients subsequently tolerated oral cephalosporins. Prior studies have previously demonstrated cross-reactivity between R1-side chains of aminopenicillins (amoxicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate) and aminocephalosporins (cefalexin, cefaclor, cefadroxil, cefprozil, cefatrizine, cefonicid, cefmandole) in delayed (T-cell-mediated) hypersensitivity, and the absence of cross-reactivity with non-cross reactive cephalosporins, carbapenems and monobactams.7, 8Romano et al. in a cohort of 214 intradermal test positive patients reporting a penicillin T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity (8 with SCAR), 89 (42%) of patients were positive to benzylpenicillin, ampicillin and amoxicillin and only 8 (8.9%) also positive to the MDM or PPL, supporting the cross-reactivity pattern seen in our cohort of all severe T-cell mediated hypersensitivity7. Overall, cross-reactivity patterns in severe T-cell-mediated hypersensitivities have not been well-defined due to caution in performing IDT and patch testing in this population, the incomplete sensitivity and lack of widespread availability and validation of ex vivo and in vitro methods, and the inability to use oral ingestion challenge as the gold standard. Watts et al. previously described a single case of Penicillin G DRESS with IDT and PT positivity to both Penicillin G and amoxicillin,9 and similar to our cohort, the patient tolerated an oral cephalosporin. This finding may be under reported in the literature due to the prior general avoidance of performing IDT in patients reporting a severe T-cell mediated hypersensitivity. The pattern of cross-reactivity demonstrated in our study and tolerance of similar R1 side-chain containing oral cephalosporins points towards the “penicillin ring” (thiazolidine) being an important component in generation of the primary antigen. Further, it highlights the importance of testing alternative penicillins in addition to PPL and MDM which were not useful reagents in documenting cross-reactivity between penicillins in patients with DRESS, AGEP and severe-MPE. We believe these are important lessons for skin testing in severe delayed and presumed T-cell mediated hypersensitivity and predicting beta-lactam tolerability in these patients.

Although a limitation to our findings includes a lack of confirmation of identified penicillin cross-reactivity with ingestion challenge, this would not be considered an ethical approach given the severity of the reported reactions and the presence of alternative therapeutic agents in these patients. Although, false positive reactions are possible, the absence of similar results in controls (Supplementary materials), reproducibility of the positive phenotypes on IDT and confirmatory patch testing with varied drug formulation (patient 1), are all supportive of true T-cell mediated responses. The dose-dependency of responses in the skin is in keeping with T-cell mediated responses where non-covalent binding of the drug or drug-altered peptide occurs in a concentration dependent fashion with an immune receptor. This could explain the positive responses we have seen with benzyl penicillin used at 1000 IU/mL and 10,000 IU/mL whereas MDM with a 0.5 mg/ml benzyl penicillin was consistently negative. The apparent lack of sensitivity of IFN-γ release ELISpot positivity to all penicillins is also noted, however this may reflect the variable sensitivity of the assay or that IFN-γ is not the relevant cytokine output for the phenotypes of delayed reactions tested . Further, the absence of IFN-γ positivity in all skin test positive patients may reflect the known absence of circulating drug-reactive effector memory T-cells despite durable long-lasting tissue-resident memory T cells responses being evident in vivo.10 This work confirms a previously infrequently described pattern of cross-reactivity between penicillins in severe T-cell mediated penicillin hypersensitivity and provides support for cephalosporin tolerability in these populations. Future work needs to be directed at understanding the antigenic structures and genomic predictors in these severe penicillin-associated T-cell mediated hypersensitivities.

Supplementary Material

Clinical implications.

This study demonstrates the utility of intradermal testing to elucidate penicillin class cross-reactivity in patients with a history of severe presumed T-cell mediated hypersensitivity. The study suggests patients should avoid not just the inciting penicillin, yet demonstrates tolerance of oral cephalosporins and utilization of alternative narrow spectrum beta-lactams

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Sandy Darling (Department of Pathology, Austin Health) for preparation of the histopathology slides.

Funding: This work was supported by the Austin Medical Research Foundation (AMRF). J. A. T. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) postgraduate scholarship (GNT 1139902) and post graduate scholarship from the National Centre for Infections in Cancer (NCIC). E. J. P. is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (award numbers 1P50GM115305-01, R21AI139021, R34AI136815 and 1 R01HG01086301.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest declared for all authors

References

- 1.Picard M, Robitaille G, Karam F, Daigle J-M, Bédard F, Biron É, et al. Cross-reactivity to cephalosporins and carbapenems in penicillin-allergic patients: Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Liss Y, Chu CY, Creamer D, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169:1071–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, Vaillant L, Roujeau JC. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)--a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol 2001; 28:113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trubiano JA, Thursky KA, Stewardson AJ, Urbancic K, Worth LJ, Jackson C, et al. Impact of an Integrated Antibiotic Allergy Testing Program on Antimicrobial Stewardship: A Multicenter Evaluation. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:166–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trubiano JA, Douglas AP, Goh M, Slavin MA, Phillips EJ. The safety of antibiotic skin testing in severe T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity of immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7:1341–3 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keane NM, Pavlos RK, McKinnon E, Lucas A, Rive C, Blyth CC, et al. HLA Class I restricted CD8+ and Class II restricted CD4+ T cells are implicated in the pathogenesis of nevirapine hypersensitivity. AIDS 2014; 28:1891–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Maggioletti M, Caruso C, Quaratino D. Cross-reactivity and tolerability of aztreonam and cephalosporins in subjects with a T cell-mediated hypersensitivity to penicillins. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138:179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buonomo A, Nucera E, Pecora V, Rizzi A, Aruanno A, Pascolini L, et al. Cross-reactivity and tolerability of cephalosporins in patients with cell-mediated allergy to penicillins. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2014; 24:331–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watts TJ, Li PH, Haque R. DRESS Syndrome due to benzylpenicillin with cross-reactivity to amoxicillin. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; 6:1766–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iriki H, Adachi T, Mori M, Tanese K, Funakoshi T, Karigane D, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in the absence of circulating T cells: a possible role for resident memory T cells. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71:e214–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.