Abstract

The low engraftment and retention rate of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) at the target site indicates that the potential benefits of MSC-based therapies can be attributed to their paracrine signaling. In this study, the extracellular matrices (ECM) deposited by bone marrow-derived human MSCs in the presence and absence of ascorbic acid was characterized. MSCs were seeded on top of decellularized ECM (dECM) and the concentrations of pro- and anti-angiogenic molecules released in culture (conditioned) media was compared. Effects of ECM derived from MSCs with different passage numbers on MSC secretome was also investigated. Our study revealed that the expression of pro-angiogenesis-related factors were upregulated when MSCs were harvested on dECMs, irrespective of media supplementation, as compared to those cultured on tissue culture plates. In addition, dECM generated in presence of ascorbic acid promoted expression of pro-angiogenic molecules as compared to dECM derived in absence of media supplementation. Further, it was observed that the effectiveness of dECM to stimulate pro-angiogenic signaling of MSCs was reduced as cell passage number was increased from P3 to P5. The proliferation as well as capillary morphogenesis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in the presence of conditioned media were enhanced compared to the normal HUVECs culture media. These data indicate that the secretory signatures of MSCs and consequently, the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs can be regulated by presentation of dECM composition and variation of its composition.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cells, Decellularized extracellular matrices, Growth factors, Angiogenesis

1. Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent adult stem cells with the ability to self-renew and differentiate into diverse cell types. Their presence at injury sites make them prime candidates for clinical therapeutic applications including restoration of tissue and organ integrity (Jackson, Nesti, & Tuan, 2012; Filardo et al., 2013) and treatment of numerous diseases, such as diabetes, ischemic heart disease, osteogenesis imperfecta, and various autoimmune diseases (Graft versus host disease (GvHD), Crohn’s, Multiple Sclerosis, etc.) (Patel, Shah, & Srivastava, 2013). Multiple active clinical trials currently listed in the US National Institutes of Health registry of clinical trials (http://clinicaltrials.gov) can be attributed to the therapeutic versatility of MSCs. Despite the promise of MSC-based therapies in tissue engineering applications, several challenges limit their clinical translation. Death promoting stimuli, such as reactive oxygen species, hypoxia, deficiency of extracellular matrix for MSC attachment, and cytotoxic cytokines contribute to low retention and engraftment of implanted cells at the target sites (Rodrigues, Griffith, & Wells, 2010; Song et al., 2010).

Alternatively, evidence suggests that bioactive factors secreted by MSCs play a critical role in reparative processes (Horie et al., 2011; Liang, Ding, Zhang, Tse, & Lian, 2014; Williams et al., 2013). Biomolecules, such as growth factors, angiogenic factors, cytokines, hormones, chemokines, and extracellular matrix proteases, comprise the MSC “secretome” and are potentially involved in MSC-mediated tissue/organ restoration (Horie et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2013). The potential benefits of MSC-secretome span from vascularization, matrix remodeling to anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects (English, 2013; Klinker & Wei, 2015; Matsui et al., 2017). Thus, harnessing MSC secretome can potentially enhance the efficacy of the cellular therapies.

Current methods for modulation of MSC secretome include pharmacological, physiological (hypoxic or anoxic), or growth factor/cytokine pre-conditioning. Some of these pre-conditioning methods are accompanied with genetic manipulations prior to transplantation (Afzal et al., 2010; Kamota et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2010). While these strategies have shown promise in inducing expression and secretion of pertinent factors, they are limited by transient effects (physiological or pharmacological preconditioning) post-transplantation and by challenges associated with clinical translation due to viral modification of the target gene (genetic manipulation). On the other hand, biomaterial-based approaches have been utilized in regulating MSC secretome (Ozsvar, Mithieux, Wang, & Weiss, 2015; Liu, Pishesha, Poon, Kaushik, & Van Vliet, 2017; Cai et al., 2016). The protein components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), namely collagen I, fibronectin, and laminin, has been reported to regulate secretory activity of MSCs (Abdeen, Weiss, Lee, & Kilian, 2014). While these studies provide some insight into the role of various ECM components in directing the paracrine activity of MSCs, these biomaterials fail to recapitulate the multifactorial aspects of extracellular components of the stem cell environment. The ECM, a complex and dynamic network of macromolecules including collagen, glycoproteins, and enzymes, not only provides a mechanical platform for cell adhesion but also supports and regulates various cellular processes through mechanical stimulation, regulation of the availability and activity of soluble and insoluble factors, and activation of intracellular signaling via the adhesion molecules (Gattazzo et al., 2014). The importance of ECM in regulating the fate of stem cells is well documented (Shakouri-Motlagh, O’Connor, Brennecke, Kalionis, & Heath, 2017; Novoseletskaya, Grigorieva, Efimenko, & Kalinina, 2019; Chermnykh, Kalabusheva, & Vorotelyak, 2018). However, the role of ECM in guiding the paracrine activities of MSCs remains unexplored.

Decellularized tissue matrices are currently being utilized in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. However, these matrices suffer from inherent heterogeneity and limited ability of customization. On the other hand, cell-derived matrices can be engineered de novo. Our long-term goal is to develop decellularized extracellular matrices (dECM) based hydrogels for enhancing the efficacy of MSC-based therapy. In this study, the influence of dECM on pro-angiogenic signaling of MSC was investigated. The ECM deposited by bone marrow-derived human MSCs in the presence and absence of ascorbic acid was characterized. MSCs were seeded on top of dECM, and the concentration of MSC-secreted pro- and anti-angiogenic molecules released in culture media was assessed. The bioactivity of MSC-secreted biomolecules were investigated by assessing the proliferation as well as capillary morphogenesis (via Matrigel culture) of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Effect of passage number on ECM secretion and regulation of MSC secretome was also investigated.

2. Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Bone marrow-derived human MSCs were procured from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 1% Penicillin Streptomycin (Pen Strep, Gibco). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from ATCC and expanded in endothelial cell basal medium-2 (EBM-2) supplemented with 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin and EGM-2 SingleQuots (containing FBS, VEGF, hFGF, R3-IGF-1, hydrocortisone, ascorbic acid, GA-1000, hEGF, and heparin). Cells were maintained in a humidified environment at 37 °C and 5% carbon dioxide. Cells up until passage 5 were used in this study.

2.2. Preparation and decellularization of ECM

150,000 MSCs were seeded in each well of 6 well plates. The passages were varied from 3 to 5. Upon confluency, the cells were cultured in normal culture medium with or without 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich). After 10 days, the wells were treated with 0.5% Triton-X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in 20 mM ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH, Fischer Scientific, USA) for 10 minutes at 37°C. Following which the wells were rinsed with Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS, Gibco, New York) for 5 minutes and treated with 200 μ/mL DNase I, RNase-Free (OPTIZYME, Fisher BioReagents), for 60 minutes at 37 °C. The ECM layers were washed with DPBS and allowed to air dry overnight. Plates were stored at −20°C until further use.

2.3. Confirmation of decellularized ECM layers

To confirm decellularization, MSCs were stained with 1% (v/v) Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Scientific, Germany) nucleic acid dye prior to treatment with Triton X-100. Images were captured before and after decellularization via laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1200). In addition, the DNA content in the samples was determined using Quant-iT™ dsDNA High-Sensitivity Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher) as per manufacturer’s instructions.

2.4. Immunofluorescence

MSCs were cultured on Lab-Tek chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and decellularized as described earlier. dECM was fixed using a 50% methanol (Fisher Scientific, Canada) and 50% acetone (Fisher Scientific, USA) solution for 20 minutes at −20°C. Wells were washed with DPBS and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for 1 h at room temperature on an orbital shaker. Samples were rinsed and incubated overnight at room temperature with COL1A1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), monoclonal anti-fibronectin antibody (Sigma), or with laminin polyclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Wells were rinsed with DPBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were then rinsed, and confocal images were captured.

2.5. Soluble collagen assay

The collagen concentration was determined, in collected dECM samples, using Soluble Collagen Assay Kit (Cell BioLabs, Inc., California). Initially, the dECM samples were treated with 0.5 mg/mL of pepsin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) solution in 0.5 M acetic acid overnight at 4°C. Digested aliquots were transferred from the wells into a 96 well plate. Following which, the samples and the assay’s collagen standards were evaporated to dryness in 37°C overnight. Sirius Red reagent was added to the samples and collagen standardsm to stain collagen’s triple helix structure, for 1 h as per manufacturer’s instructions. The stained wells were washed and incubated with an extraction solution to transfer the eluted dye to a new plate. The amount of collagen was measured using a plate spectrophotometer (Eon, BioTek).

2.6. sGAG assay

Sulfated glycosaminoglycan (sGAG) was quantitatively determined using Glycosaminoglycans Assay Kit (Chondrex, Inc., Washington). sGAG were extracted from the dECM samples using papain extraction reagent. To create the papain extraction solution, 0.1M sodium acetate, 0.01M Na2ETDA (EMD Millipore Corporation, USA), and 0.005M cysteine hydrochloride were added to 0.2M sodium phosphate buffer (sodium phosphate monobasic and sodium phosphate dibasic). Once all the components were completely dissolved, papain suspension (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to the extraction buffer and stored at 4°C for a maximum of 10 days. Papain extraction solution was then added to the dECM samples and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Digested aliquots were collected from the wells and mixed with 1,9 Dimethylmethlyene (DMB) Dye Solution as per manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of GAGs in samples were determined using the Eon plate spectrophotometer and regression analysis.

2.7. Proliferation Assay of MSCs on dECM

3,000 MSCs (passage 4, P4) were seeded on top of the air-dried dECMs (generated in the presence and absence of ascorbic acid) and cultured in normal culture medium for 48 h. Following which the proliferative activity of the MSCs were measured using XTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (ATCC). MSCs seeded on the tissue culture plate (TCP) acted as a control. The proliferation of MSCs on dECMs were expressed as percent growth over the control.

2.8. Angiogenesis Profiling of dECM condition media

150,000 MSCs (P4) were seeded on air-dried dECM (generated with and without ascorbic acid) in normal culture medium. Cells seeded on TCP acted as a control. After 24 h, the media was replaced with serum-free medium. The spent/conditioned media was collected after 48 h and was stored at −20°C until further use. The concentrations of pro- and anti-angiogenic molecules in the conditioned media were determined via Proteome Profiler™ Human Angiogenesis Antibody Array (R&D Systems) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Each assay was conducted twice.

2.9. Assessing Bioactivity of dECM conditioned media

2.9.1. Proliferation of HUVECs

The activity of MSC-secreted biomolecules was investigated by assessing the proliferation of HUVECs. Conditioned media from MSCs (P4) seeded on top of dECMs was collected and concentrated using Vivaspin concentrators (2,000 MWCO, Sartorius). 20,000 HUVECs were seeded in the wells of a 96 well plates in the presence of the conditioned media. HUVECs cultured in presence of normal culture medium acted as control. After 48 h, XTT proliferation assay was utilized to measure proliferative activity of HUVECs.

2.9.2. Capillary morphogenesis of HUVECs

50 μL of Geltrex ™ LDEV-Free Reduced Growth Factor Basement Membrane Matrix (Gibco) was pipetted into the wells of 96 well plates and incubated at room temperature. 50,000 HUVECs were seeded onto the gels and incubated in the presence of MSC conditioned media and normal HUVECs culture medium at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After incubating for 15 h, images of the capillary sprout formations were captured via Zeiss Axio Observer A1 microscope with integrated CCD camera, and the number of sprouts per image was counted. At least 3 images were analyzed per condition.

2.11. Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicates and repeated at least three times. Statistical analyses were carried out using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD test. Differences between two sets of data were considered statistically significant at p-value less than 0.05.

3. Results

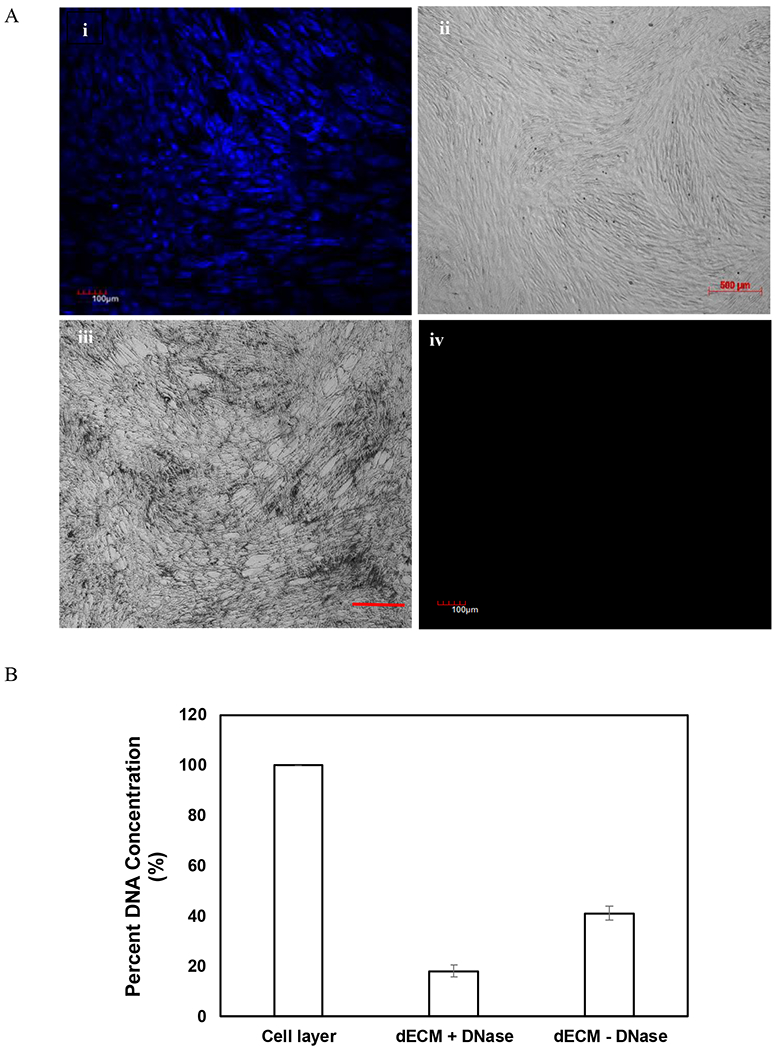

MSC cultures were decellularized 10 days post-confluence. Hoechst staining as well as phase contrast images confirmed confluency with well-defined cell nuclei prior to decellularization (Figure 1A, i and ii). Lack of Hoechst staining following treatment with Triton X-100 in 20 mM NH4OH solution confirmed the disruption of cellular nuclei and removal of genetic material (Figure 1A, iii). Further, phase contrast image confirmed the deposition of ECM by MSCs (Figure 1A, iv). In addition, decellularization efficiency was examined by DNA quantification. As demonstrated in Fig 1B, compared to the cellular layer, the amount DNA retained in ECM scaffolds following decellularization was reduced. This observation suggests that the decellularization protocol efficiently removed DNA from the matrices.

Figure 1.

Confirmation of decellularization and deposition of dECM (A). MSCs were stained with 1% (v/v) Hoechst nucleic acid dye 10 days post-confluence, and images were captured. Hoechst images (scale bar of 100μm) (i) and phase contrast images (scale bar of 500μm) (ii) confirmed confluency prior to decellularization. Lack of Hoechst staining confirmed removal of cellular nuclei and genetic material (iii), and phase contrast image revealed the remaining deposition of ECM after the removal of cells (iv). DNA quantification of cell layer and extracellular matrices following decellularization (B). Treatment with DNase decreased DNA content in the matrices drastically. Error bar Standard deviation (N=2).

3.1. Effect of media supplementation with and without ascorbic acid

3.1.1. dECM composition

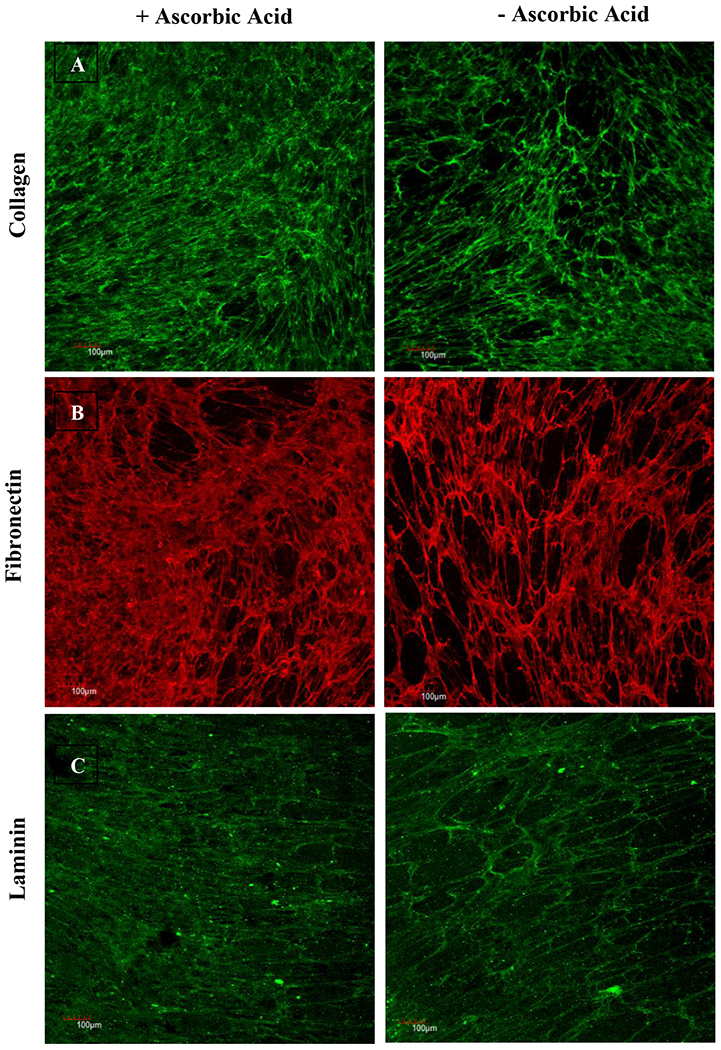

Ascorbic acid, also known as vitamin C, has been demonstrated to influence ECM synthesis and remodeling (Tagler et al., 2014; Kumar, Satyam, Cigognini, Pandit & Zeugolis, 2018; Cigognini et al., 2016). To explore the effect of media supplementation on deposition/synthesis of various ECM components, the decellularized matrices generated by MSCs (P4) were stained for collagen, fibronectin, and laminin. Immunofluorescence staining revealed deposition and preservation of ECM structure post-decellularization. MSCs deposited abundant ECM proteins suggesting generation of biologically complex matrices irrespective of media supplementation (Figure 2). However, the presence of ascorbic acid influenced the relative distribution of ECM protein deposition.

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence staining to compare the effect of ascorbic acid on ECM deposition. MSCs (P4) were decellularized 10 days post-confluence, and cell-free matrices were stained for collagen (A), fibronectin (B), and laminin (C). Scale bar: 100 μm.

Soluble collagen assay was utilized to quantify collagen, the most abundant protein in ECM, deposited by MSCs. As shown in Table 1, no significant difference in the amount of collagen deposition was observed irrespective of media supplementation. Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), another important component of ECM, regulates cell-matrix interaction by modulating the localization and presentation of growth factors and morphogens (Couchman & Pataki, 2012). The impact of ascorbic acid supplementation on concentration of GAGs (chondroitin-6-sulfate) deposited by MSCs was investigated via glycosaminoglycans assay. A subtle increase in GAGs deposition was observed when MSCs were incubated with ascorbic acid (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of the presence (+AA) or absence (−AA) of ascorbic acid supplementation on collagen and GAGs deposition from P4 MSCs. Data represented as (Mean ± Error). Error: S.E.M (N ≥ 4).

| + AA | − AA | |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen (μg/mL) | 24.111 ± 1.026 | 22.855 ± 1.572 |

| Chondroitin-6-sulfate (μg/mL) | 12.115 ± 2.589 | 8.917 ± 1.471 |

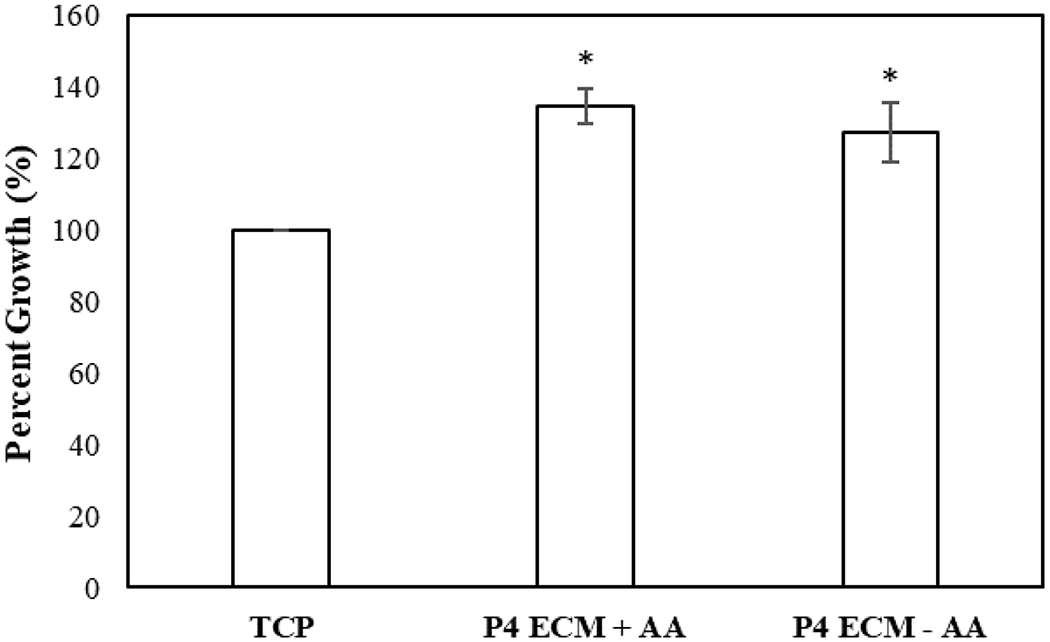

3.1.2. MSC activity

To investigate whether dECM generated as a function of media supplementation impact proliferative activity of MSCs, cells were seeded on dECM (P4), and proliferation was measured. MSCs grown on top of TCP acted as control. As demonstrated in Figure 3, MSCs seeded on dECM resulted in a significantly accelerated proliferation compared to the cells seeded on TCP (p-value < 0.05). However, no significant difference (p-value> 0.05) was observed in the proliferative activity of MSCs when seeded on the dECM generated with or without ascorbic acid supplements.

Figure 3.

Effect of dECM on proliferation of MSCs. MSCs were seeded on P4 dECM with (P4 ECM+AA) or without ascorbic acid (P4 ECM−AA) and cell growth was measured with respect to TCP. Error bars S.E.M (N=3). *p-value<0.05 in respect to TCP.

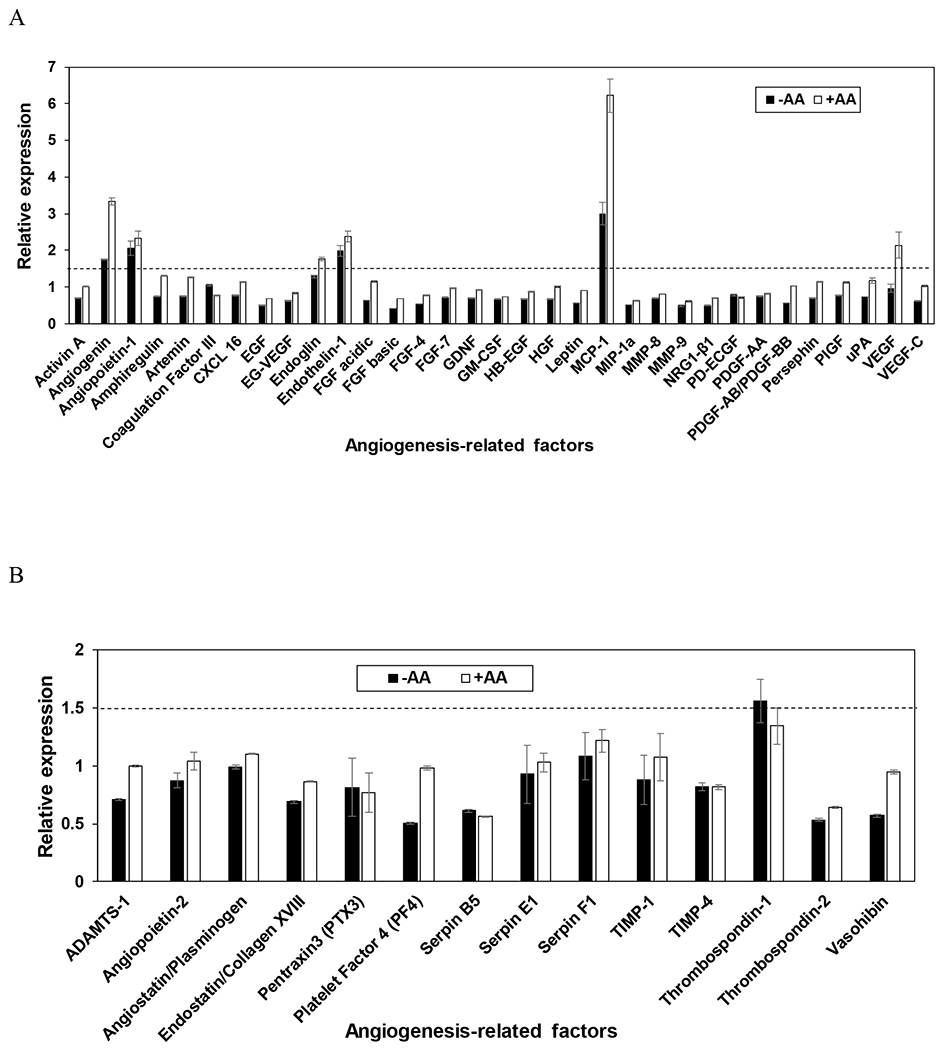

3.1.3. MSC-angiogenic activity

To investigate the effect of dECM on angiogenic activity of MSCs (P4), cells were seeded on dECM (P4) and the concentrations of MSC-secreted angiogenesis-related molecules within the conditioned media were analyzed via Proteome Profiler™ Human Angiogenesis Antibody Array (R&D Systems). To explore the influence of dECM on angiogenic signaling of MSCs, the signal intensities obtained in presence of dECM were normalized with respect to the TCP control. As demonstrated in Figure 4A and B, secretion profile of MSCs altered when dECM, prepared irrespective of media supplementation, acted as culture surface of MSCs. The expression levels of multiple pro-angiogenic molecules were found to be upregulated (relative expression compared to control > 1.5) in the presence of ECM. Interestingly, secretion activity of MSCs cultured on ECM generated with and without ascorbic acid displayed different relative expression. Different pro-angiogenic molecules including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiogenin, endothelin-1, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) were upregulated in the presence of ECM generated with ascorbic acid supplements. On the other hand, no changes were observed in the expression of anti-angiogenesis factors. Taken together, these observations highlight the effectiveness of dECM in improving the angiogenic potential of MSCs when other culture conditions (seeding density and cell passage number) were maintained constant.

Figure 4.

Effect of ECM on pro-angiogenic signaling (A) and anti-angiogenic signaling (B) of MSCs. Comparison of the expression of these factors when MSCs (P4) were seeded on P4 dECM with (+AA) or without (−AA) ascorbic acid supplements relative to TCP (control). All factors resulting in a relative expression greater than 1.5, as indicated by the dotted line, are upregulated. Error bar Standard deviation (N=2).

3.2. Investigating the influence of varying passage number on dECM

In an earlier study, compositional changes had been identified within dECM as a function of MSC age (Sun et al., 2011). Furthermore, studies have also demonstrated dECM derived from low passage cells promotes expansion of primary MSCs; however, dECM generated from aged MSCs loses the potency (Sun et al., 2011 & Ng et al., 2014). Taking into account that subcultured cells at different passages deposit ECM with different expression patterns, the effect of these variations on pro-angiogenic activity of MSCs was investigated. For the purpose, passage number of MSCs was varied from 3 to 5.

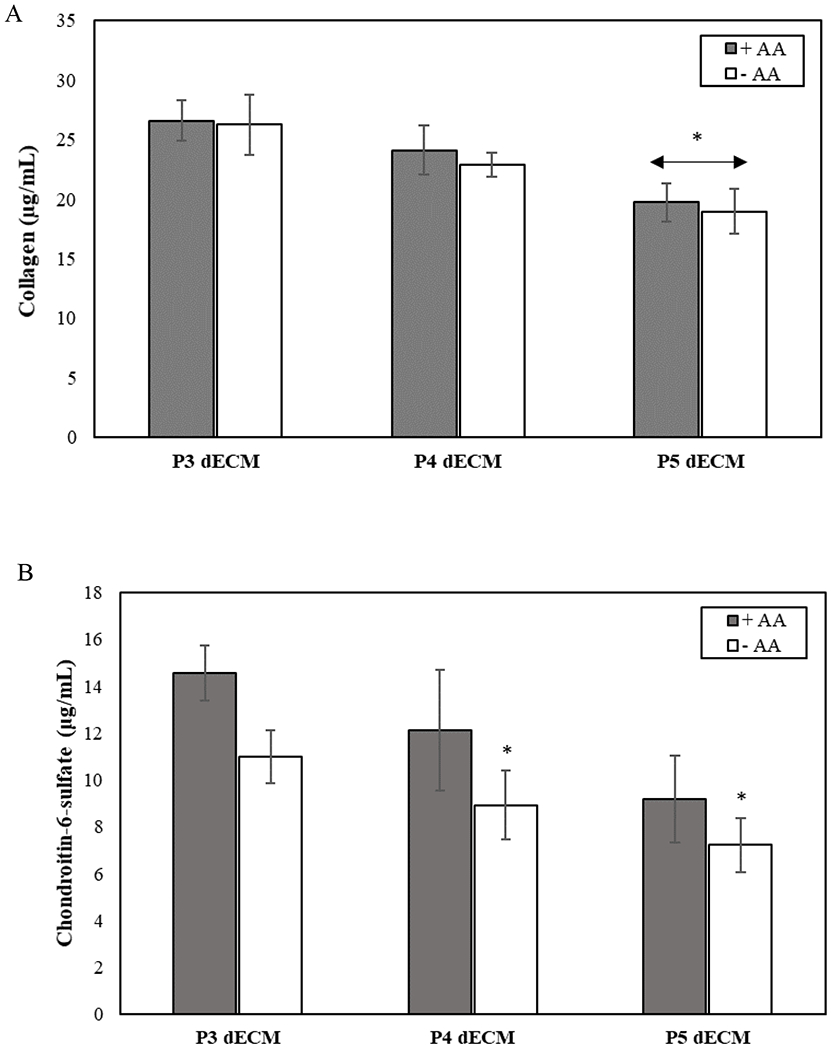

3.2.1. dECM composition

Quantitative analysis of dECM revealed a decreased deposition of collagen and GAGs with increasing passage number irrespective of media supplementation (Figure 5). The concentration of collagen deposited by P5 MSCs was found to be significantly reduced as compared to those deposited by P3 MSCs in presence of ascorbic acid (p-value <0.05). Quantification of GAGs revealed that irrespective of passage number, supplementation with ascorbic acid resulted in an increase in expression of GAGs; however, the enhanced expression was not statistically significant (p-value > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effect of passage number on the composition of MSC-derived dECM generated with (+AA) or without (−AA) ascorbic acid supplements. Comparison of the deposition of collagen (A) and GAGs (chondroitin-6-sulfate) secretion (B) as a function of cell passage number in the presence and absence of media supplementation. Error bar S.E.M (N=3). *p-value<0.05 with respect to P3 dECM, +AA.

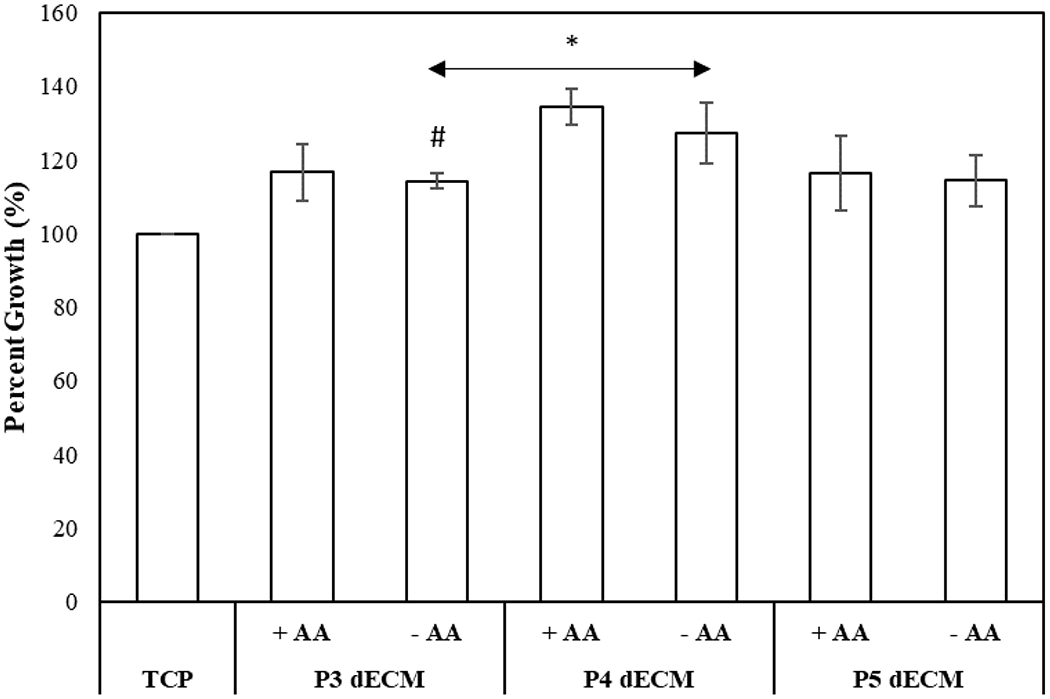

3.2.2. MSC behavior

The influence of dECM generated as a function of passage number on MSC proliferation was assessed. For the purpose, P4 MSCs were seeded on dECM as culture surfaces and TCP (control). As demonstrated in Figure 6, seeding MSCs on top of dECM increased proliferative activity compared to control. Interestingly, MSCs seeded on P4 dECM, both with or without ascorbic acid, had the highest percent growth (p-value < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effect of dECM generated by MSCs (P3-P5) in the presence (+AA) or absence (−AA) of ascorbic acid on proliferation of MSCs (P4). The cell growth was normalized with respect to control (TCP). Error bar S.E.M (N=3). #p-value<0.05 with respect to P4 ECM, +AA; *p-value<0.05 in respect to TCP.

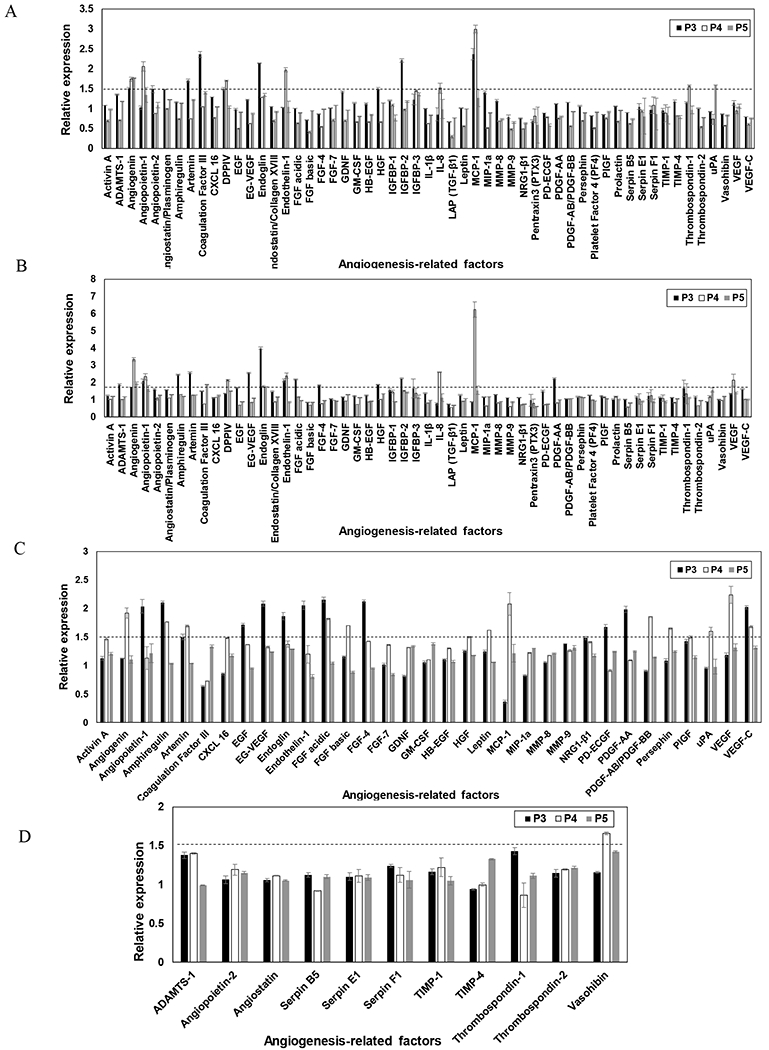

3.2.3. Angiogenic activity of MSCs

The concentration of 55 pro- and anti-angiogenic molecules in the conditioned media was determined using Proteome Profiler™ Human Angiogenesis Antibody Array. As demonstrated in Figure 7A and B, compared to the control (no ECM), expression of pro-angiogenesis-related factors was upregulated (relative expression > 1.5) when MSCs were cultured on dECM irrespective of media supplementation for all the passages of MSCs studied. However, the relative expression of different angiogenic molecules varied as a function of passage number of MSCs. Further analysis revealed, dECM generated in presence of ascorbic acid promoted expression of angiogenic molecules as compared to dECM derived in absence of media supplementation, particularly at lower passages of MSCs (P3 and P4) (Fig 7 C and D). When the effect of dECM-derived from MSCs of different passages on angiogenic signaling was compared, it was observed that at lower passage number (P3 dECM) the expression of majority of pro-angiogenic molecules were upregulated (Fig 7C). The effectiveness of dECM to stimulate angiogenic signaling of MSCs reduced as passage number was increased from P3 to P5.

Figure 7.

Effect of dECM passage number on angiogenic signaling of MSCs. The expression of angiogenic factors when P4 MSCs were seeded on dECM generated by P3-P5 MSCs in the absence (A) and presence (B) of ascorbic acid relative to TCP (control). The concentration of pro-angiogenic (C) and anti-angiogenic (D) factors secreted by MSCs seeded on P3-P5 dECM supplemented with ascorbic acid were also normalized to the molecules secreted by MSCs seeded on dECM without ascorbic acid. The dotted lines correspond to the relative expression of 1.5. Error bar Standard deviation (N=2).

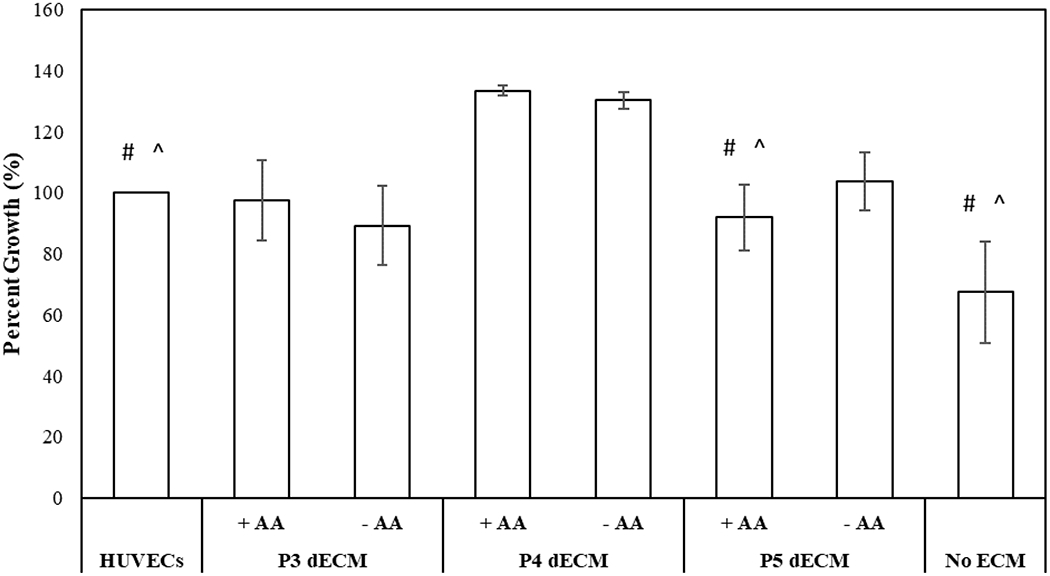

3.2.4. Bioactivity of factors secreted by MSCs seeded on dECM

To assess the bioactivity of factors released by MSCs after being seeded on varying dECM passages (P3-P5), the impact of conditioned media on proliferation and capillary morphogenesis of HUVECs was investigated. As demonstrated in Figure 8, compared to the conditioned media collected from MSCs seeded on TCP (no ECM) (negative control), conditioned media collected from MSCs cultured on dECM enhanced proliferation of HUVECs irrespective of passage number and media supplementation. Upon comparing the impact of passage number, maximal proliferation was observed when HUVECs were incubated in conditioned media collected from MSCs seeded on dECM generated by P4 cells (p-value < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Investigation of activities of factors secreted by P4 MSCs upon seeding on dECM generated by P3-P5 MSCs in the presence (+AA) and absence (−AA) of ascorbic acid. Proliferation of HUVECs in presence of conditioned medium was normalized with respect to HUVECs culture media. Error bar S.E.M (N=3). #p-value<0.05 with respect to P4 dECM, + AA; ^p-value<0.05 with respect to P4 dECM, − AA.

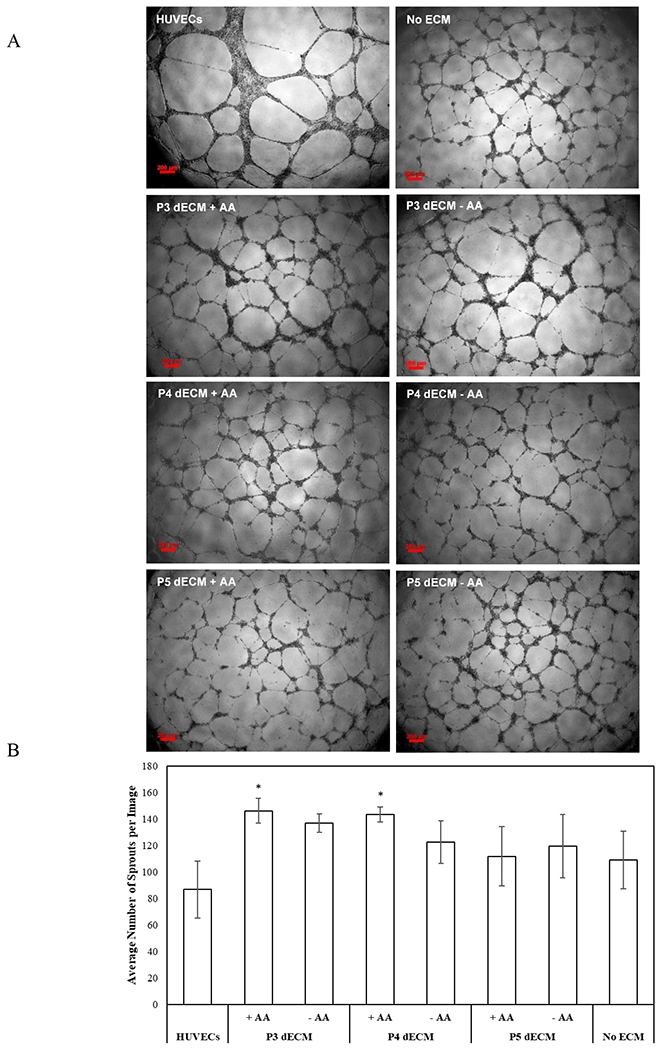

To assess the influence of MSC-secreted molecules on capillary morphogenesis, images were captured (Fig 9A) and the total number of sprouts per image was measured (Fig 9B). The conditioned media collected from MSCs seeded on P3 and P4 dECM generated in presence of ascorbic acid stimulated maximal sprouts formation (p-value < 0.05) in comparison to the positive control (HUVECs).

Figure 9.

Effect of secreted biomolecules on sprouting of HUVECs. Typical images of sprout formation during Matrigel culture of HUVECs in the presence of conditioned medium (scale bar of 200μm) (A). Number of sprouts formed per image was measured to assess capillary morphogenesis of HUVECs in presence of conditioned medium (B). HUVECs culture media was the positive control, and conditioned media collected from MSCs seeded on TCP (no ECM) acted as the negative control. Error bar S.E.M (N=3). *p-value<0.05 with respect to HUVECs (positive control).

4. Discussion

The diffusive molecular factors secreted by stromal cells are critical for intercellular communication and subsequent maintenance of tissue homeostasis (Sinclair, Yerkovich, Hopkins, & Chambers, 2016). Mounting evidence attributes the efficacy of MSC-based therapy to its paracrine effects including the anti-apoptosis, pro-angiogenic, anti-inflammation, and anti-fibrotic effects (English, 2013; Klinker, 2015; Matsui et al., 2017). Thus, harnessing paracrine secretions of MSCs can potentially contribute to successful clinical translation of MSC-based therapy. ECM not only provides a highly organized lattice where cells reside and interact with each other, but also plays an important role in regulating the behavior of cells including migratory, proliferative, and metabolic activities (Lin, Yang, Yan, & Tuan, 2012). Studies have demonstrated that when cells are cultured on ECM in vitro, they display growth characteristics, morphology, as well as biological behaviors which were not observed when grown on artificial plastic, glass substrate, or TCP coated with isolated ECM components (Patel et al., 2013). Studies employing decellularized matrices from epithelial cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts as well as adult bone marrow stem cells for MSC expansion, corroborated that decellularized matrices offer superior substrates for proliferation of cells in contrast to traditional methods (Lin et al., 2012; DeQuach et al., 2010; Decaris & Leach, 2011). Although the cell-instructive characteristics of ECM and subsequent effect in regulation of stem cell fate is well known (Ahmed & Ffrench-Constant, 2016), its role in guiding the paracrine signaling of stem cells is still underappreciated.

In this study, the influence of ECM in stimulating pro-angiogenic activity of MSCs was explored. The compositional heterogeneity in ECM has been attributed to stem cell fate, and thus, 4it seems likely that the secretory signature of MSCs will be altered in presence of ECM with varying biological complexity. Since culture conditions can strongly influence the deposition and organization of ECM (Prewitz et al., 2015), the impact of ascorbic acid on ECM deposition and consequently on proliferation and chondrogenic differentiation has been studied in earlier studies (Pizzute, Zhang, He, & Pei, 2016). It was demonstrated that dECM generated in the absence of ascorbic acid supplementation permitted higher proliferation of cells but chondrogenic differential potential was reduced. In this study, the influence of dECM generated in presence and absence of ascorbic acid on MSC paracrine activity was investigated. Another important parameter that was explored is the effect of cell passage on the deposition/composition of ECM. In accordance with recent studies (Prewitz et al., 2015), our data demonstrated that ascorbic acid supplementation, influenced the secretion and deposition of different ECM components including collagen, fibronectin, and laminin. In addition, consistent with other studies, our data also demonstrated an enhanced amount of sulphated GAGs within the secreted matrices in the presence of ascorbic acid. The overall content of GAGs strongly influences the presentation and functionality of growth factors and thus, plays a critical role in the guiding the behavior of adherent cells. Further, a passage-related reduced expression of ECM proteins and GAGs was also observed. This observation is in line with earlier studies which demonstrated ECM development is dependent on the passage number of the cells (Tan et al., 2015).

Investigation of the influence of dECM on angiogenic signaling of MSCs revealed large variations in secretome profiles as a function of dECM (media supplementation and cell passages). When MSCs were seeded on dECM generated in absence of ascorbic acid, angiogenin is the only factor that was upregulated irrespective cell passages. On the other hand, dECM modulation by ascorbic acid upregulated angiogenin, angiopoientin-1, and endoglin across cell passages albeit with a large variation. Furthermore, high expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) by P4 MSCs was observed irrespective of media supplementation. Earlier studies have also reported MCP-1 to be a major paracrine factor secreted by MSCs that is involved in promotion of angiogenesis and inhibition of apoptosis (Boomsma & Geenen, 2012). Similarly, other studies have identified release of MCP-1 by utilizing cord blood derived (Liu & Hwang, 2005) and embryonic stem cell-derived MSCs (Sze et al., 2007). Interestingly, the presence of dECM did not influence the secretion of anti-angiogenic factors irrespective of media supplementation and cell passages.

To explore whether the modulated secretome profiles would translate to enhanced pro-angiogenic activities of MSCs, proliferation of HUVECs in presence of conditioned media was investigated. Irrespective of cell passages and media supplementation, proliferation of HUVECs was enhanced as compared to conditioned media collected from MSCs seeded on TCP. As a matter of fact, proliferation of HUVECs was found to be comparable (P3 and P5 ECM with and without ascorbic acid) or higher (P4 ECMs) than the normal HUVEC culture media supplemented with cocktail of growth factors (positive control). Enhanced stimulatory activity of MSC-secretome can be attributed to angiogenin, one of the potent angiogenic factors, which was upregulated irrespective of media supplementation across cell passages. Angiogenin, by inducing transient phosphorylation of extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2 (Erk 1/2) in cultured HUVECs, has been shown to stimulate proliferation and tubular structure formation (Liu, Yu, Xu, Riordan, & Hu, 2001). In addition, angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) and endothelin-1(ET-1), which were primarily upregulated in MSC secretome obtained from P4 ECMs may contribute to higher proliferation of HUVECs. Ang-1 has drawn attention in clinical applications by virtue of its ability to promote blood vessel reconstruction. Ang-1 has been shown to promote proliferation of endothelial cells through activator protein −1 (AP-1) dependent autocrine production of IL-8 (Abdel-Malak, Srikant, Kristof, Magder, Di Battista, & Hussain, 2008). Further our study also revealed that the modulation of secretory profiles translated to enhanced sprouting assessed via rECM gel-based angiogenesis assay. Heterogeneous pro-angiogenic properties of MSCs as a function of tissue origins have been previously reported (Du et al., 2016; Amable, Teixeira, Carias, Granjeiro, & Borojevic, 2014; Hsieh et al., 2013). Studies have demonstrated that MSCs derived from bone marrow and placental chorionic villi exhibited significant therapeutic angiogenic activities compared to those harvested from adipose tissue or umbilical cord (Du et al., 2016). On the other hand, studies have also reported that adipose tissue as well as umbilical cord-derived MSCs exhibit better pro-angiogenic profile than bone marrow-derived MSCs (Amable et al., 2014; Hsieh et al., 2013). Although inconsistent reports exist regarding pro-angiogenic efficacies of MSCs from different tissue origins, the importance of MSC secretome in therapeutic angiogenesis is appreciated. In this study, MSC-derived matrices were generated and characterized to harness the pro-angiogenic profile of MSCs. While earlier studies have correlated expansion and differentiation potential of stem cells with dECM composition (Pizzute et al., 2016), to the best our knowledge, this is the first study which reports alteration of MSC secretory signatures via presentation and variation of dECM composition.

5. Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank NIH (1R03EB026526-01) and NSF (1531217) for the financial support.

7. References

- Abdeen AA, Weiss JB, Lee J, & Kilian KA (2014). Matrix composition and mechanics direct proangiogenic signaling from mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue engineering. Part A, 20(19-20), 2737–2745. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2013.0661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Malak NA, Srikant CB, Kristof AS, Magder SA, Di Battista JA, & Hussain SN (2008). Angiopoietin-1 promotes endothelial cell proliferation and migration through AP-1-dependent autocrine production of interleukin-8. Blood, 111(8), 4145–4154. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-110338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afzal MR, Haider H, Idris NM, Jiang S, Ahmed RP, & Ashraf M (2010). Preconditioning promotes survival and angiomyogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in the infarcted heart via NF-kappaB signaling. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 12(6), 693–702. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M, & Ffrench-Constant C (2016). Extracellular Matrix Regulation of Stem Cell Behavior. Current stem cell reports, 2(3), 197–206. doi: 10.1007/s40778-016-0056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amable PR, Teixeira MV, Carias RB, Granjeiro JM, & Borojevic R (2014). Protein synthesis and secretion in human mesenchymal cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue and Wharton’s jelly. Stem cell research & therapy, 5(2), 53. doi: 10.1186/scrt442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma RA, & Geenen DL (2012). Mesenchymal stem cells secrete multiple cytokines that promote angiogenesis and have contrasting effects on chemotaxis and apoptosis. PloS One, 7(4), e35685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Dewi RE, Goldstone AB, Cohen JE, Steele AN, Woo YJ, & Heilshorn SC (2016). Regulating Stem Cell Secretome Using Injectable Hydrogels with In Situ Network Formation. Advanced healthcare materials, 5(21), 2758–2764. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201600497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chermnykh E, Kalabusheva E, & Vorotelyak E (2018). Extracellular Matrix as a Regulator of Epidermal Stem Cell Fate. International journal of molecular sciences, 19(4), 1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigognini D, Gaspar D, Kumar P, Satyam A, Alagesan S, Sanz-Nogués C, … Zeugolis DI (2016). Macromolecular crowding meets oxygen tension in human mesenchymal stem cell culture - A step closer to physiologically relevant in vitro organogenesis. Scientific reports, 6, 30746. doi: 10.1038/srep30746 doi:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couchman JR, & Pataki CA (2012). An introduction to proteoglycans and their localization. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society, 60(12), 885–897. doi: 10.1369/0022155412464638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaris ML, & Leach JK (2011). Design of experiments approach to engineer cell-secreted matrices for directing osteogenic differentiation. Annals of biomedical engineering, 39(4), 1174–1185. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0217-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeQuach JA, Mezzano V, Miglani A, Lange S, Keller GM, Sheikh F, & Christman KL (2010). Simple and high yielding method for preparing tissue specific extracellular matrix coatings for cell culture. PloS one, 5(9), e13039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du WJ, Chi Y, Yang ZX, Li ZJ, Cui JJ, Song BQ, … Han ZC (2016). Heterogeneity of proangiogenic features in mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and placenta. Stem cell research & therapy, 7(1), 163. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0418-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English K (2013). Mechanisms of mesenchymal stromal cell immunomodulation. Immunology and Cell Biology, 1(1), 19–26. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo G, Madry H, Jelic M, Roffi A, Cucchiarini M, & Kon E (2013). Mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of cartilage lesions: from preclinical findings to clinical application in orthopaedics. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 21(8), 1717–1729. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattazzo F, Urciuolo A, & Bonaldo P (2014). Extracellular matrix: a dynamic microenvironment for stem cell niche. Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1840(8), 2506–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie N, Pereira MP, Niizuma K, Sun G, Keren-Gill H, Encarnacion A, … Steinberg GK (2011). Transplanted stem cell-secreted vascular endothelial growth factor effects poststroke recovery, inflammation, and vascular repair. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio), 29(2), 274–285. doi: 10.1002/stem.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JY, Wang HW, Chang SJ, Liao KH, Lee IH, Lin WS, … Cheng SM (2013). Mesenchymal stem cells from human umbilical cord express preferentially secreted factors related to neuroprotection, neurogenesis, and angiogenesis. PloS one, 8(8), e72604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson WM, Nesti LJ, & Tuan RS (2012). Concise review: clinical translation of wound healing therapies based on mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Translational Medicine, 1(1), 44–50. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamota T, Li TS, Morikage N, Murakami M, Ohshima M, Kubo M, … Hamano K (2009). Ischemic pre-conditioning enhances the mobilization and recruitment of bone marrow stem cells to protect against ischemia/reperfusion injury in the late phase. Journal of American College of Cardiology, 53(19), 1814–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinker MW, & Wei CH (2015). Mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases in experimental animal models. World journal of stem cells, 7(3), 556–567. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i3.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Satyam A, Cigognini D, Pandit A, & Zeugolis DI (2018). Low oxygen tension and macromolecular crowding accelerate extracellular matrix deposition in human corneal fibroblast culture. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 12(1), 6–18. doi: 10.1002/term.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Ding Y, Zhang Y, & Tse HF, & Lian Q (2014). Paracrine mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy: current status and perspectives. Cell Transplant 23(9), 1045–1059. doi: 10.3727/096368913X667709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Yang G, Yan J, & Tuan RS (2012). Influence of decellularized matrix derived from human mesenchymal stem cells on their proliferation, migration and multi-lineage differentiation potential. Biomaterials, 33(18), 4480–4489. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, & Hwang SM (2005). Cytokine interactions in mesenchymal stem cells from cord blood. Cytokine, 32(6), 270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu FD, Pishesha N, Poon Z, Kaushik T, & Van Vliet KJ (2017). Material Viscoelastic Properties Modulate the Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome for Applications in Hematopoietic Recovery. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, 3(12), 3292–3306. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Yu D, Xu ZP, Riordan JF, & Hu GF (2001). Angiogenin activates Erk1/2 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 287(1), 305–310. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui F, Babitz SK, Rhee A, Hile KL, Zhang H, & Meldrum KK (2017). Mesenchymal stem cells protect against obstruction-induced renal fibrosis by decreasing STAT3 activation and STAT3-dependent MMP-9 production. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology, 312(1), F25–F32. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00311.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CP, Sharif AR, Heath DE, Chow JW, Zhang CB, Chan-Park MB, … Griffith LG (2014). Enhanced ex vivo expansion of adult mesenchymal stem cells by fetal mesenchymal stem cell ECM. Biomaterials, 35(13), 4046–4057. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoseletskaya ES, Grigorieva OA, Efimenko AY, & Kalinina NI (2019). Extracellular matrix in the regulation of stem cell differentiation. Biochemistry, 84(3), 232–240. doi: 10.1134/S0006297919030052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozsvar J, Mithieux SM, Wang R, & Weiss AS (2015). Elastin-based biomaterials and mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials science, 3(6), 800–809. doi: 10.1039/C5BM00038F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel DM, Shah J, & Srivastava AS (2013). Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine. Stem Cells International, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/496218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M, Griffith LG, & Wells A (2010). Growth factor regulation of proliferation and survival of multipotential stromal cells. Stem cell research & therapy, 1(4), 32. doi: 10.1186/scrt32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prewitz MC, Stißel A, Friedrichs J, Träber N, Vogler S, Bornhäuser M, & Werner C (2015). Extracellular matrix deposition of bone marrow stroma enhanced by macromolecular crowding. Biomaterials, 73, 60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzute T, Zhang Y, He F, & Pei M (2016). Ascorbate-dependent impact on cell-derived matrix in modulation of stiffness and rejuvenation of infrapatellar fat derived stem cells toward chondrogenesis. Biomedical materials (Bristol, England), 11(4), 045009. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/11/4/045009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakouri-Motlagh A, O’Connor AJ, Brennecke SP, Kalionis B, & Heath DE (2017). Acta Biomaterialia, 55, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair KA, Yerkovich ST, Hopkins PM, & Chambers DC (2016). Characterization of intercellular communication and mitochondrial donation by mesenchymal stromal cells derived from the human lung. Stem cell research & therapy, 7(1), 91. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0354-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Cha MJ, Song BW, Kim IK, Chang W, Lim S, … Hwang KC (2010). Reactive oxygen species inhibit adhesion of mesenchymal stem cells implanted into ischemic myocardium via interference of focal adbhesion complex. Stem Cells, 28(3), 555–563. doi: 10.1002/stem.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Li W, Lu Z, Chen R, Ling J, Ran Q, … Chen XD (2011). Rescuing replication and osteogenesis of aged mesenchymal stem cells by exposure to a young extracellular matrix. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 25(5), 1474–1485. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-161497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze SK, de Kleijn DP, Lai RC, Khia Way Tan E, Zhao H, Yeo KS, … Lim SK (2007). Elucidating the secretion proteome of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 6(10), 1680–1689. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600393-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagler D, Makanji Y, Tu T, Bernabé BP, Lee R, Zhu J, … Shea LD (2014). Promoting extracellular matrix remodeling via ascorbic acid enhances the survival of primary ovarian follicles encapsulated in alginate hydrogels. Biotechnology and bioengineering, 111(7), 1417–1429. doi: 10.1002/bit.25181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan AR, Alegre-Aguarón E, O’Connell GD, VandenBerg CD, Aaron RK, Vunjak-Novakovic G, … Hung CT (2015). Passage-dependent relationship between mesenchymal stem cell mobilization and chondrogenic potential. Osteoarthritis and cartilage, 23(2), 319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JM, Wang JN, Guo LY, Kong X, Yang JY, Zheng F, … Huang YZ (2010). Mesenchymal stem cells modified with stromal cell-derived factor 1 alpha improve cardiac remodeling via paracrine activation of hepatocyte growth factor in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Molecules and Cells, 29(1), 9–19. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Hatzistergos KE, Addicott B, McCall F, Carvalho D, Suncion V, … Hare JM (2013). Enhanced effect of combining human cardiac stem cells and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to reduce infarct size and to restore cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Circulation, 127(2), 213–223. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.131110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]