Abstract

Background

Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) is a non-IgE- mediated food allergy. Its relationship to the major atopic manifestations (atopic dermatitis, AD; IgE-mediated food allergy, IgE-FA; allergic rhinitis, AR; asthma) is not understood.

Objective

Determine the clinical characteristics, epidemiologic features, and natural history of FPIES in relation to the major atopic manifestations.

Methods

We examined our primary care birth cohort of 158,510 pediatric patients, of which 214 patients met 2017 FPIES diagnostic criteria. We measured the influence of FPIES on developing subsequent atopic disease.

Results

Pediatric FPIES incidence was between 0.17% and 0.42% depending on birth year. As in prior reports, most patients had an acute presentation (78%) and milk, soy, oat, rice, potato, and egg were common triggers. The mean age of diagnosis was 6.8 months. Atopic comorbidity was higher in FPIES patients compared to healthy children (AD, 20.6% vs. 11.7%; IgE-FA, 23.8% vs. 4.0%; asthma, 26.6% vs. 18.4%; AR, 28.0% vs. 16.7%; p<0.001 Chi-squared). However, longitudinal analyses indicated that prior FPIES did not influence the rate of atopy development.

Conclusions

The incidence of FPIES in our cohort was initially low, but is increasing. Food allergen distribution, presentation, and age of onset are similar to prior reports. FPIES patients have high rates of atopic comorbidity, however, longitudinal analysis does not support direct causation as the etiology of these associations. Rather it suggests a shared predisposition to both types of allergy, or associative bias effects. This work refines our understanding of the natural history of FPIES by elucidating associations between FPIES and atopy.

Keywords: Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome, FPIES, Food Hypersensitivity, IgE-mediated food allergy, Asthma, Dermatitis, Atopic, Rhinitis, Allergic, Epidemiology, Atopic march

INTRODUCTION

Food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) is a non-IgE-mediated food allergy that manifests with gastrointestinal symptoms, and is frequently triggered by cow’s milk, soy, and grains.1–3 The onset of FPIES typically occurs during infancy, though there are limited reports in older children and adults.4,5 The symptoms of FPIES vary with the frequency of allergen exposure, and are classified into acute or chronic forms.6 Acute FPIES occurs when allergen exposure is intermittent, and manifests as delayed (2–4 hours after ingestion) vomiting with or without diarrhea, pallor, or hypotension. Due to the risk of dehydration, acute FPIES can be a medical emergency. In contrast, chronic FPIES typically occurs in young infants ingesting the allergen daily, and manifests as progressive watery diarrhea, emesis, and poor weight gain.7

First described in the 1960s,8,9 it was not until 2015 that an FPIES-specific international classification of diseases code was introduced.3 Perhaps due to its relatively recent definition, the epidemiological features of FPIES are still being determined. In one study, Katz et al. utilized a prospective birth cohort from a single Israeli hospital and observed a 2-year cumulative incidence of cow’s milk FPIES of 0.34%.10 By comparison, Mehr et al. studied an Australian primary care-based cohort using a cross-sectional disease surveillance survey and found a cumulative incidence ranging from 0.013–0.024%.11 Large North American retrospective case series of FPIES patients have estimated the point prevalence at approximately 1%.1,12 Despite these well-designed studies, the true incidence of FPIES remains largely unknown.

In contrast to FPIES, our knowledge surrounding the epidemiologic features of the atopic manifestations (atopic dermatitis, AD; IgE-mediated food allergy, IgE-FA; allergic rhinitis, AR; asthma) are more robust. For example, it is now well established that development of one atopic manifestation increases an individual’s risk of developing subsequent atopic disease in a clinical progression known as the “atopic march”.13 However, as FPIES is a non-IgE mediated food allergy, its pathologic connection with the classic atopic manifestations is less clear. Interestingly, FPIES patients have consistently been reported to have increased rates of AD (6–51%), IgE-FA (4–5%), asthma (3–25%), and AR (13.6–72%) when compared with healthy children.14–19 Though shown across multiple studies, it is not known whether these associations represent a shared predisposition between FPIES and the atopic manifestations, if FPIES predisposes to the development of atopic disease, or if this association is the result of methodologic bias.

In this study, we use electronic medical record review of a large primary care birth cohort to determine the natural history, clinical characteristics, and epidemiologic features of physician-diagnosed FPIES. This unique approach allows us to examine the natural incidence of FPIES over time, and in relationship to patient age. We further define children with FPIES in terms of demographics, clinical characteristics, and most common food allergens. Finally, we measure the prevalence of atopic comorbidities in patients with FPIES, and perform multivariable analyses to determine if prior FPIES diagnosis influences the rate of atopy development. This work refines our view of the natural history of FPIES, and expands our understanding of the relationship between this condition and atopic disease.

METHODS

Birth cohort generation and clinical data extraction

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) network consists of 31 outpatient clinical care sites across the greater Delaware valley that provide both primary and subspecialty pediatric care. Data from this network has previously been validated as a tool to assess regional disease epidemiology. 20,21

To determine the epidemiologic relationships between FPIES and the atopic disorders, we examined the electronic medical records (Epic Systems Inc., Verona, WI) of the 158,510 children who are part of the CHOP primary care birth cohort, as previously defined 21. To be included in this cohort, patients were required to have established care in the CHOP primary care network before their first birthday, and between January 1, 2001 and December 31, 2018. Patients were also required to have received primary care from a CHOP-affiliated practice for at least 2 years. Observation time for children was censored on the date of their last face-to-face outpatient health care encounter in our health system before their 17th birthday, and we assumed that patients were observed continuously until they were censored.

FPIES cohort generation, definition, and validation

Patient records within the birth cohort were selected for additional review if International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes corresponding to FPIES were used (ICD-9: Allergic gastroenteritis and colitis, 558.3 and ICD-10 Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome, K52.2). A manual review of all charts containing FPIES ICD codes was performed by pediatric allergists. Patients were excluded if it was not possible to verify an eliciting allergen and reaction symptoms consistent with 2017 FPIES diagnostic criteria for both acute and chronic FPIES 6 We excluded cases of suspected chronic FPIES without historical, accidental, or physician-supervised challenge confirming the FPIES phenotype. If FPIES diagnosis was not clear from the EMR, three physicians jointly reviewed the patient data to make a determination. Additional features including age of onset and eliciting allergens were recorded. Only allergens documented to elicit FPIES reactions are reported.

Atopic disease cohorts generation

We ascertained presence or absence of atopic conditions of interest (AD, IgE-FA, asthma, and AR) using a combination of diagnosis codes, allergen information, and medication prescriptions as described previously 21,22 All diagnoses were made in accordance with established practice parameters. For inclusion in a disease cohort, patients were required to have diagnosis codes representative of an atopic condition on two separate care visits, occurring at least six months apart.

To maximize the specificity of our IgE-FA cohort, we: (1) required an epinephrine autoinjector prescription and a food allergen entry in the EMR allergy module, (2) excluded diagnosis codes relating to food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome and eosinophilic esophagitis, and (3) recoded patients with diagnosis codes corresponding to lactose intolerance and gluten sensitivity (celiac disease) as non-milk or non-wheat allergic, respectively. Additionally, manual chart review was performed on all FPIES patients cohort to confirm symptoms of IgE-mediated food allergy separate from symptoms of FPIES, and to record allergens which elicited symptoms.

To maximize specificity of our asthma cohort, we: (1) limited our analysis to ICD codes occurring after 1 year of age, (2) required prescriptions for asthma-specific medications (e.g., albuterol, inhaled corticosteroid) on at least two separate dates, and (3) ignored ICD codes related to viral-induced wheeze and reactive airway disease.

Statistics

Chi-squared testing was initially used to examine the frequency of atopic manifestations in FPIES patients compared to those without. We studied longitudinal disease diagnosis in individuals across our birth cohort, and performed case-control comparisons using Cox proportional hazards monitoring with adjustments for demographic covariates (birth year, race, ethnicity, gender, and payer type). Peak age of diagnosis was defined as the mode of the disease incidence curve. Longitudinal comparisons were performed via two approaches. First, we examined the rate of onset of atopic diseases in the FPIES and non-FPIES cohorts irrespective of the timing of FPIES diagnosis. Next, we examined the rate of onset of atopic diseases in patients with, or without, a preceding FPIES diagnosis. In the latter analysis, we treated children who had FPIES after the outcome of interest the same as children who did not have the exposure condition during our observation time. Because of the variable follow-up time, we chose cox proportional hazard ratios (HR) with confidence intervals (CI) to present our results. Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted to display risk over time. After adjustment for the covariates (birth year, race, ethnicity, sex, insurance payer), p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Availability of data

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Zenodo repository (http://10.5281/zenodo.3508812).

Ethical and regulatory oversight

Chart review was performed with approval from the CHOP Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Cohort demographics

Of the 158,510 children in the CHOP primary care birth cohort, 214 patients had a confirmed diagnosis of FPIES after imposing EMR criteria and performing physician chart review (Figure 1). The demographic characteristics of the cohorts (Table I) demonstrate significant predominance of male and white race patients in the FPIES group compared to the overall cohort (64% males in FPIES vs. 51% overall, 77% white in FPIES cohort vs 50% in overall; Chi-Squared p<0.001 for both). Private insurance was also more common in the FPIES cohort (84% in the FPIES cohort vs 67% in overall; Chi-Squared p<0.001).

Figure 1: Study Design.

We performed a retrospective review of 158,510 patients using an EMR-based primary care birth cohort to identify patients with Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) and Non-FPIES patients with atopic diagnoses. To do so, we used a combination of ICD-9/10 codes, allergen and medication information, and manual chart review.

Table I.

Demographic characteristics of the EMR cohorts

| Cohort %, (n) 158,510 total patients |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Primary Care 99.86% (158,296) | FPIES 0.14% (214) |

| Gender, % (n) | ||

| Male | 51% (81,129) | 64% (137) |

| Female | 49% (77,167) | 36% (77) |

| Race, % (n) | ||

| White | 50% (78,526) | 77% (165) |

| Black | 32% (50,828) | 9% (19) |

| Asian / Pacific Islander | 4% (5,816) | 4% (8) |

| Other | 2% (3,153) | 2% (5) |

| Unknown | 12% (19,973) | 8% (17) |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 7% (10,484) | 5% (11) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 93% (147,812) | 95% (203) |

| Birth year, % (n) | ||

| 2000 to 2004 | 9% (13,356) | <1% (1) |

| 2005 to 2009 | 38% (60,562) | 7% (14) |

| 2010 to 2014 | 39% (61,970) | 50% (106) |

| 2015 or Later | 14% (22,408) | 43% (93) |

| Payer type, % (n) | ||

| Medicaid | 33% (52,254) | 16% (35) |

| Non-Medicaid | 67% (106,042) | 84% (179) |

FPIES incidence and age of diagnosis

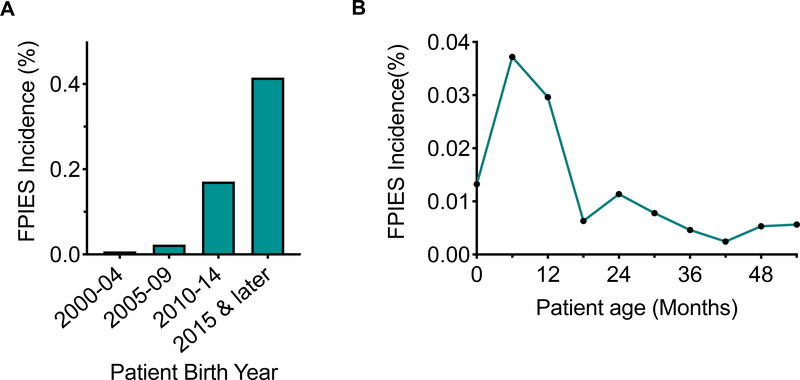

The cumulative incidence of FPIES across all years within our birth cohort was 0.14%. However, the distribution of FPIES diagnoses over time was unequal (Figure 2A), with highest FPIES incidence in the patient sub-cohort born between 2015 and 2018 (maximum of 0.415%). We next examined the age-specific incidence rate for FPIES in our cohort (Figure 2B), in order to determine how patient age affected incidence of FPIES, we examined the FPIES age-specific incidence rate. The peak age-specific FPIES incidence occurs at 6 months of age. Overall, the majority of patients in our cohort presented under one year of age, which is consistent with previous data on FPIES. 1,3,17,23 However, there were a small number of children in this cohort who presented with new symptoms of FPIES beyond the age of three. From 3 years of age to 12 years of age, the incidence remained low (0.0041±0.001, mean ± SD). There was no pattern of consistent eliciting allergens in this older FPIES group.

Figure 2: Incidence of FPIES.

A) Incidence of FPIES by birth year. B) Incidence of FPIES by age. FPIES, Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome.

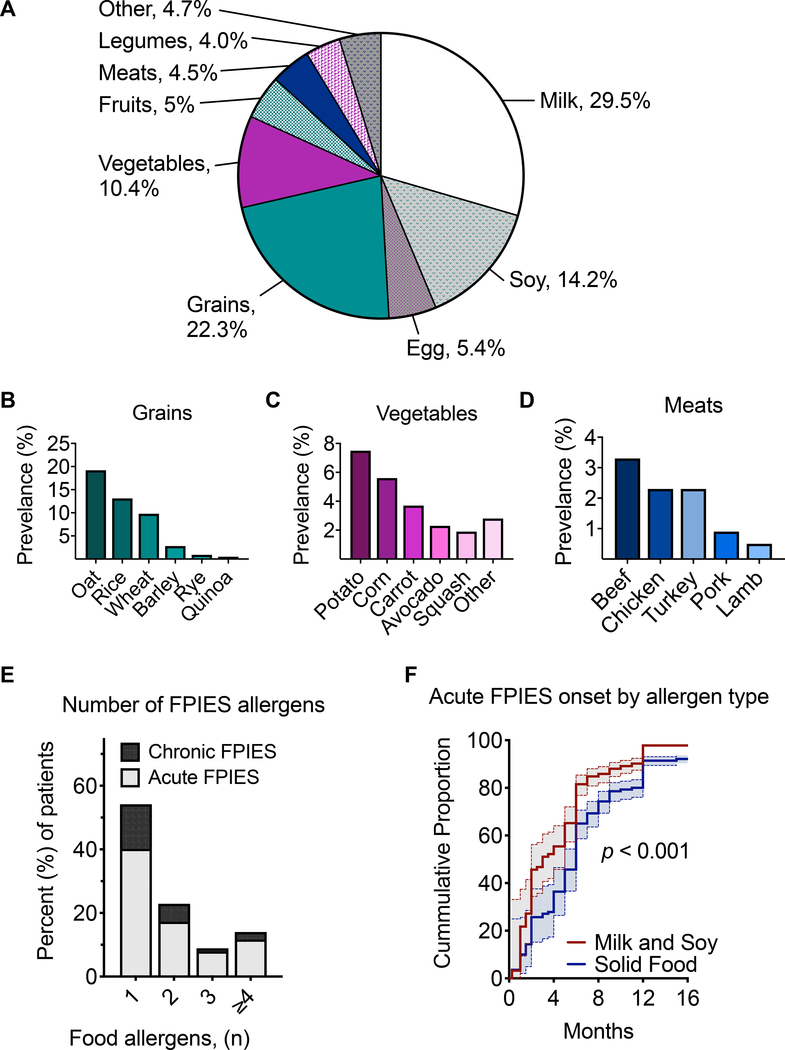

FPIES causal food allergens and acuity

We next examined patient data to characterize the presentation of FPIES within this cohort. Board-certified allergists reviewed the charts of FPIES patients to determine which foods were responsible for symptomatic FPIES reactions. Consistent with previous reports, the most common causal foods were milk, grains, and soy (Figure 3A). Milk and soy represented the most prevalent single food triggers, followed by egg. Among grains, oat, rice, and wheat were the most common eliciting allergens (Figure 3B). White potato and corn accounted for the majority of vegetable triggers (Figure 3C), though we also observed avocado as a prominent trigger consistent with recent reports.18,24 FPIES reactions were observed to a variety of meats including beef, chicken, turkey, pork, and lamb (Figure 3D).

Figure 3: FPIES food allergens and presentation.

A) Frequency of the most common food allergens in patients with FPIES. Frequency of FPIES allergens within categories of B) grains, C) vegetables, and D) meats. E) Percent of patients presenting with acute or chronic FPIES phenotype. F) Onset of acute FPIES to milk and soy as compared with solid foods, in relation to patient age. FPIES, Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome.

FPIES presentations can be classified as either acute or chronic.6 The majority of patients in our cohort (78%) presented with symptoms of acute FPIES, with the remaining patients meeting criteria for chronic FPIES (Figure 3E). Consistent with prior studies, chronic FPIES was diagnosed in infants in our cohort between 1 to 4 months of age.7 Regardless of presentation type, it was most common for patients to have a single FPIES food trigger (Figure 3E). However, some patients with symptoms to multiple food triggers were also observed. In the case of chronic FPIES to multiple foods, 59.2% of patients reacted to milk alone, 8.2% to soy alone, and 32.6 to milk and soy.

We and others have previously reported observed earlier onset of acute FPIES to milk and soy as compared to solid foods.1,17,18 Consistent with this observation, children presenting with acute FPIES triggered by milk or soy in our primary care birth cohort were more likely to present with FPIES at an earlier age (median age 3 months) when compared to those with acute FPIES to solid foods (median age 6 months, p<0.001, Figure 3F). FPIES to milk and soy is commonly seen prior to the onset of solid foods, and it is hypothesized that this relates to the order in which these foods are introduced during weaning.1,17,18 Together, this data highlights the similarities of our FPIES cohort patients’ clinical presentations to that of other cohorts described in North America.

Relationship between FPIES and the atopic conditions

We next examined the degree of atopic comorbidity in FPIES patients using Chi-Squared testing (Table II). When comparing FPIES patients to healthy controls, prevalence of IgE-FA was increased approximately six-fold (23.8% vs. 4.0%;odds ratio, OR 10.5 [5.5–10.4]). The prevalence of AD was the next greatest increase in the FPIES patient cohort, nearly two-fold increased in FPIES patients compared to controls (11.7% in primary care cohort patients without EoE, versus 20.6 in cohort patients with EoE). Lastly, asthma and AR had a relatively smaller increase in cumulative incidence within the FPIES cohort, but were still significantly increased when compared with patients without FPIES (Asthma OR 1.6[1.2–2.2), AR OR 1.9[1.4–2.6]. These findings are consistent with prior reports that have also found a high burden of atopy in FPIES patients.25

Table II.

Cumulative incidence of atopic comorbidity in FPIES

| % of Cohort |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Care (n=158,296) | FPIES(n=214) | p-value | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | |

| Atopic Dermatitis | 11.7% | 20.6% | <0.001 | 2.0 [1.5–2.7] |

| IgE-Food Allergy | 4.0% | 23.8% | <0.001 | 7.6 [5.5–10.4] |

| Asthma | 18.4% | 26.6% | <0.01 | 1.6 [1.2–2.2] |

| Allergic Rhinitis | 16.7% | 28.0% | <0.001 | 1.9 [1.4–2.6] |

Cumulative incidence of atopic comorbidities at 10 years of follow-up in patients with and without FPIES. p-value is shown from Chi-squared test, followed by Woolf-logit method to compute unadjusted odds ratio.

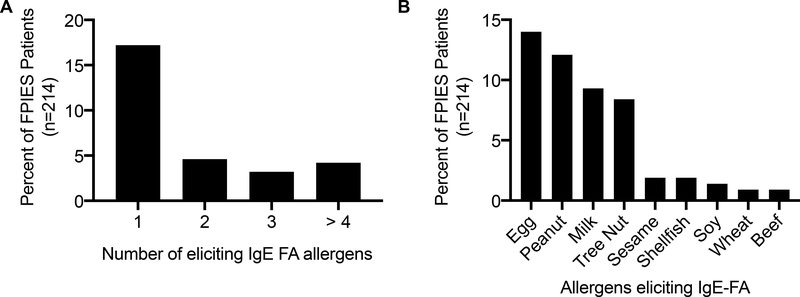

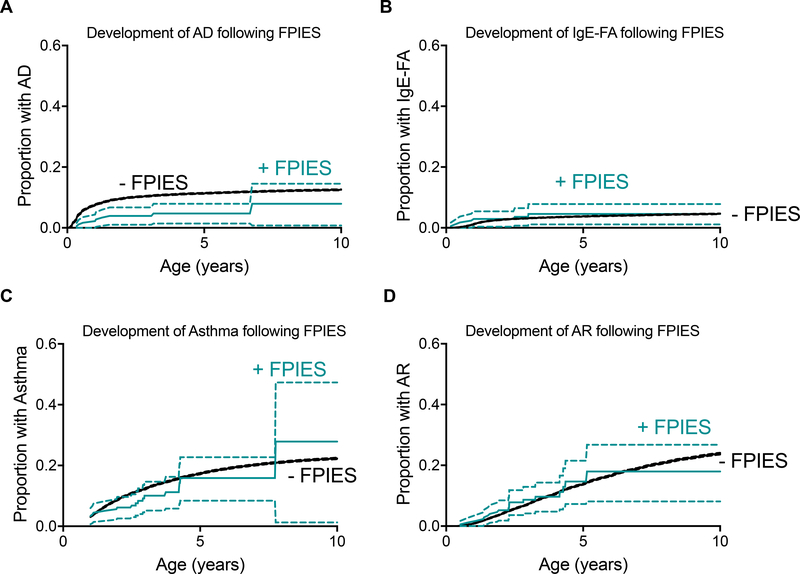

As retrospective analyses of disease cohorts are subject to several forms of bias, we next sought to examine the temporal relationships between FPIES onset and the development of atopy. To do so, we used cox proportional hazard modeling which incorporated patient birth year, race, ethnicity, sex and insurance status as covariates. We first examined the onset of AD, IgE-FA, asthma, and AR in the FPIES and non-FPIES cohorts, irrespective of the timing of FPIES diagnosis (e.g. FPIES onset could precede or follow atopic diagnosis). FPIES cohort patients develop atopy at a higher rate than healthy controls (Figure 4), an observation that is consistent with FPIES patients having a high burden of atopic disease.25 As this data suggests that FPIES accelerates the rate of atopic disease development, we next explored the impact of coexisting FPIES and atopic dermatitis on the rate of IgE-FA development. We observe that FPIES is associated with increased risk of IgE-FA, regardless of if patients had comorbid atopic dermatitis (Figure 5). Further, FPIES confers additional risk for development of IgE-FA than atopic dermatitis alone (hazard ratio 4.3 [2.7, 6.8] in AD-, FPIES+ vs FPIES− patients). The majority of FPIES patients had comorbid IgE-FA to 1 type of eliciting allergen, (Figure 6A), and the most common IgE-FA triggers in FPIES patients were egg, peanut, milk, and tree nuts (Figure 6B).

Figure 4: Development of atopy in FPIES and non-FPIES cohorts, irrespective of timing of FPIES onset.

Kaplan-Meier curves and 95% confidence intervals displaying diagnosis of A) atopic dermatitis (AD), B) IgE-mediated food allergy (IgE-FA), C) asthma, D) allergic rhinitis (AR) in FPIES patients or healthy controls. Hazard ratios (HR), 2.5% to 97.5% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values from logistic regression for each comparison are shown in each panel.

Figure 5: Interaction of FPIES and atopic dermatitis (AD) on development of IgE-mediated food allergy.

Kaplan-Meier curves and 95% confidence intervals from analysis of IgE-FA development in patients with or without FPIES (as a categorical variable) or AD.

Figure 6: IgE food allergy triggers in FPIES patients.

A) Percent of total FPIES cohort patients with IgE-FA to one, two, three, or four or more eliciting allergens. B) Percent of total FPIES cohort patients with IgE-FA to the eliciting allergens shown.

Next, we sought to understand whether a history of FPIES increases one’s risk of developing subsequent atopy. To do so, we examined the rate of atopy development in patients with a preceding FPIES diagnosis. With the requirement that FPIES diagnosis precedes the development of atopy, we observed no significant difference in the rate of onset of the atopic outcome in the FPIES and non-FPIES cohort (Figure 7). Similarly, if FPIES is required to precede the diagnosis of IgE-FA, only AD remains a significant determinant of IgE-FA development (data not shown). Therefore, although there is increased atopic comorbidity in FPIES patients, our analyses demonstrate that in contrast to the relationship observed in the atopic march,22 a prior diagnosis of FPIES does not increase the rate of subsequent atopy development.

Figure 7: Development of atopy in patients with preceding FPIES.

Kaplan-Meier curves and 95% confidence intervals displaying diagnosis of A) atopic dermatitis (AD), B) IgE-mediated food allergy (IgE-FA), C) asthma, D) allergic rhinitis (AR) in FPIES patients or healthy controls.

Conclusions

FPIES is increasingly recognized as a cause of food allergy in young children.26 Here, we provide a large, retrospective study of physician-diagnosed FPIES within a primary care-based pediatric cohort. Several of our findings are consistent with prior observations in subspecialty-based cohorts. In particular, males and whites were diagnosed with FPIES slightly more frequently than females and other races, and the most common foods causing FPIES were milk, soy, oat and rice.1,6,15,17,18 Additionally age of disease presentation was significantly older in patients who reacted to solid foods, as opposed to those who reacted to milk and soy.1 The similarities between our current cohort, and those that have been previously described, suggest that our methods accurately identified patients with FPIES.

Using incidence density analysis across patient age, we find the peak age of FPIES diagnosis to be at 6 months, followed by a period of relatively steady, low incidence. Due to the variable observation times available for children in our cohort, it is possible that our analysis could fail to detect an additional late peak of disease onset. Our data indicates an average yearly incidence of FPIES of 0.008% after age 3, corresponding to a handful of observations of FPIES presentation in children above age 3 years within our cohort. Indeed, there are rare reports of de novo FPIES development in adolescents and adults.4,5,27 However, such cases are rare, and the majority of studies describe the onset of FPIES in infancy, and we also report peak incidence at 6 months of age.

We also observe a variable incidence across the study time period. Specifically, the incidence of FPIES diagnosis increases across the timespans from 2010–2014, and then again from 2015–2018. Several reasons may account for this increase in incidence. While we have previously been able to identify FPIES cases using the nonspecific ICD-9 coding at our institution, implementation of the FPIES-specific diagnostic code in 2015 may have permitted us to better identify cases. This increase may also reflect growing provider awareness of the FPIES diagnosis. Lastly, we cannot exclude the possibility that the incidence of FPIES within our study population is increasing. Consistent with prior studies.14–19 we observe that the overall prevalence of atopic disease is higher in children with FPIES as compared with healthy children. A strength of our analysis compared with prior is that by comparing physician-diagnosed disease rates in a birth cohort, we can control for local medical practice patterns. As such, our estimates likely represent more accurate measures of the epidemiologic features of FPIES, and the degree of disease comorbidity between FPIES and the atopic conditions when compared with prior studies.

However, when interpreting these findings it is important to consider possible mechanisms of disease association: chance, selection bias, and causal association.28 The association between FPIES and atopy have been demonstrated across multiple studies in diverse patient cohorts, making the association unlikely to be a result of chance alone. When considering bias, there are several forms that may contribute to the observed associations. Examinations of sub-specialty cohorts are susceptible to subject selection bias, ascertainment bias, and provider bias, as allergists may be more likely to diagnosis atopic comorbidities in FPIES patients, or may diagnose the complications at a younger age than a general practitioner. The use of a primary care cohort in our study helps to negate some of these biases, with the caveat that many FPIES patients are still referred to allergists. Although clinician choice of diagnosis codes can be a source of potential bias, a strength of our analysis is the use of physician-entered diagnosis codes and manual chart review to identify FPIES patients.

Having considered the effects of chance and bias, one can consider an etiological association between FPIES and atopy. Four broad categories of etiology exist: direct causation, associated risk factors, heterogeneity, and independence.28 These groups are not mutually exclusive; one or more can contribute to a disease association as is likely the case with the atopic march.13,21 While it is not possible to establish causality using a study such as this one, one can determine the temporal features of an association to support or refute a particular etiologic category. This is particularly relevant to direct causation where an initial disease process is a direct cause of a second, subsequent disease (e.g. diabetes mellitus and cataracts).28 In this etiological group, the causative feature(s) of the initial disease must occur before the development of the second, subsequent disease.

To understand the temporal relationship between FPIES and the atopic conditions, we performed two longitudinal examinations. First, we measured the rate of atopy in FPIES patients irrespective of the timing of FPIES diagnosis. In this first approach, we observed that FPIES patients have a higher rate of development of atopic comorbidity as compared with non-FPIES patients. However, when we constrain this analysis to examine if a preceding FPIES diagnosis alters the rate of atopic manifestations, we observe that patients with a preceding FPIES diagnosis develop atopy at the same rate as the birth cohort population. In other words, although the atopic burden is higher among FPIES patients, a preexisting FPIES diagnosis does not increase one’s risk for development of subsequent atopy. This temporal relationship is not consistent with direct causation as a mechanism of etiological association between these conditions. Rather, this pattern of association supports a yet unknown etiology such as shared predisposition to both types of allergy. This association could also be explained by the effect of bias confounding the analysis. Together, these data improve our understanding of the true epidemiologic relationships between FPIES and the atopic manifestations.

HIGHLIGHTS.

What is already known about this topic?

Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome is associated with high atopic comorbidity, however, there is little data examining potential mechanisms that underlie this association.

What does this article add to our knowledge?

We performed longitudinal analysis in a primary care birth cohort. Although we observe high levels of atopic comorbidity, we did not find evidence for a direct causal relationship between prior FPIES and later atopy.

How does this study impact current management guidelines?

Our data suggests a possible shared predisposition to FPIES and atopy, though provider bias toward diagnosing atopic disorders in FPIES patients may contribute to these associations. Clinicians should monitor FPIES patients for symptoms of atopic disorders.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health NCATS award KL2TR001879 (MAR) and NIDDK award K08 DK116668 (DAH), The CHOP Research Institute (DAH), a CHOP Frontier Award (JMS), and the Stuart Starr Endowed Chair (JMS). The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AD

Atopic Dermatitis

- AR

Allergic Rhinitis

- CHOP

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

- EMR

Electronic Medical Record

- FPIES

Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- IgE-FA

IgE-mediated food allergy

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial or personal interests relevant to the work contained in this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ruffner MA, Ruymann K, Barni S, Cianferoni A, Brown-Whitehorn T, Spergel JM. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: Insights from review of a large referral population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarvinen-Seppo K, Sickles L, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Clinical Characteristics of Children with Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis (FPIES). JACI. 2010;125:AB85. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sicherer SH, Eigenmann PA, Sampson HA. Clinical features of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. J Pediatr. 1998;133:214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Delgado P, Caparros E, Moreno MV, Cueva B, Fernández J. Food protein–induced enterocolitis-like syndrome in a population of adolescents and adults caused by seafood. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:670–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandes BN, Boyle RJ, Gore C, Simpson A, Custovic A. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome can occur in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nowak-Wĝrzyn A, Chehade M, Groetch ME, Spergel JM, Wood RA, Allen K, et al. International consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome: Executive summary—Workgroup Report of the Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1111–1126.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberger T, Feuille E, Thompson C, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Chronic food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: Characterization of clinical phenotype and literature review. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 2016. p. 227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gryboski JD. Gastrointestinal Milk Allergy in Infants. Pediatrics. 1967;40:354–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikola RA. Severe Intestinal Reaction Following Ingestion of Rice. Am J Dis Child. 1963;105:281–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz Y, Goldberg MR, Rajuan N, Cohen A, Leshno M. The prevalence and natural course of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome to cow’s milk: a large-scale, prospective population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:647–53.e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehr S, Frith K, Barnes EH, Campbell DE. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in Australia: A population-based study, 2012–2014. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:1323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miceli Sopo S, Monaco S, Badina L, Barni S, Longo G, Novembre E, et al. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome caused by fish and/or shellfish in Italy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26:731–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill DA, Spergel JM. The atopic march: Critical evidence and clinical relevance. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2018;120:131–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludman S, Harmon M, Whiting D, du Toit G. Clinical presentation and referral characteristics of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in the United Kingdom. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehr S, Kakakios A, Frith K, Kemp ASAS. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: 16-year experience. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e459–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson HA, Sicherer SH. Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome Caused by Solid Food Proteins. Pediatrics. 2003; 111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caubet JC, Ford LS, Sickles L, Jarvinen KM, Sicherer SH, Sampson HA, et al. Clinical features and resolution of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: 10-year experience. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:382–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackman AC, Anvari S, Davis CM, Anagnostou A. Emerging Triggers of FPIES: Lessons from a Pediatric Cohort of 74 Children in the US. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2019; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Warren CM, Brown-Whitehorn T, Cianferoni A, Schultz-Matney F, Gupta RS. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in the US-population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feemster KA, Odeniyi FM, Localio R, Grundmeier RW, Coffin SE, Metlay JP. Surveillance for Healthcare-Associated Influenza-Like Illness in Pediatric Clinics: Validity of Diagnosis Codes for Case Identification. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1247–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill DA, Grundmeier RW, Ram G, Spergel JM. The epidemiologic characteristics of healthcare provider-diagnosed eczema, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and food allergy in children: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill DA, Grundmeier RW, Ramos M, Spergel JM. Eosinophilic Esophagitis Is a Late Manifestation of the Allergic March. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1528–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sopo SM, Giorgio V, Dello Iacono I, Novembre E, Mori F, Onesimo R, et al. A multicentre retrospective study of 66 Italian children with food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: different management for different phenotypes. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:1257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cherian S, Neupert K, Varshney P. Avocado as an emerging trigger for food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:369–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehr S, Frith K, Campbell DE. Epidemiology of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Vol. 14, Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014. p. 208–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Spergel JM. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: Not so rare after all! Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2017;140:1275–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan JA, Smith WB. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food hypersensitivity syndrome in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:355–7.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:357–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Zenodo repository (http://10.5281/zenodo.3508812).