Abstract

Two-dimensional transition metal carbides/nitrides, known as MXenes, have been recently receiving attention for gas sensing. However, studies on hybridization of MXenes and 2D transition metal dichalcogenides as gas-sensing materials are relatively rare at this time. Herein, Ti3C2Tx and WSe2 are selected as model materials for hybridization and implemented toward detection of various volatile organic compounds. The Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 hybrid sensor exhibits low noise level, ultrafast response/recovery times, and good flexibility for various volatile organic compounds. The sensitivity of the hybrid sensor to ethanol is improved by over 12-fold in comparison with pristine Ti3C2Tx. Moreover, the hybridization process provides an effective strategy against MXene oxidation by restricting the interaction of water molecules from the edges of Ti3C2Tx. An enhancement mechanism for Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 heterostructured materials is proposed for highly sensitive and selective detection of oxygen-containing volatile organic compounds. The scientific findings of this work could guide future exploration of next-generation field-deployable sensors.

Subject terms: Materials science, Nanoscience and technology

Two-dimensional transition metal carbides and nitrides are promising for gas sensor applications. Here the authors report a nanohybrid-based wireless monitoring system with capabilities for selectivity and sensing for volatile organic compounds that are enhanced by heterojunction interfaces.

Introduction

The significance of wearable and wireless technologies has been increasing rapidly with internet of things (IoTs)1,2, in which sensors are crucial components deemed necessary to collect massive amounts of information from surrounding environments. For example, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are common air pollutants contributing to the formation of ground-level ozone and carcinogens, and are thus harmful to human health3. Therefore, it is important to develop a wireless-operating gas sensor for IoTs with rapid, selective, sensitive, and reversible detection of VOCs at room temperature.

Two-dimensional (2D) MXenes are generally produced by etching the intermediate A layers of a Mn+1AXn phase, where M, A, and X represent an early transition metal, A-group element, and carbon (or nitrogen) element (n = 1, 2, or 3), respectively4. Because of a combination of properties such as stable and easily tunable microstructure, high electrical conductivity, large chemically active surface, and adjustable hydrophilicity, low-dimensional MXenes and MXene-based nanocomposites have recently received considerable attention particularly to catalysis5–7, energy conversion/storage8–10, and biomedical applications11–13. Their application to gas sensor design, however, is rarely studied, and only focuses on pristine MXenes (Ti3C2Tx, V2CTx, and Ti2CO2)14–16. On the other hand, 2D transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have been considered as promising sensing materials owing to their high surface-to-volume ratios, good adsorption properties, large number of active sites for redox reactions, and high surface reactivity17,18. Indeed, a significant number of literature reports have recently emerged regarding their integration into chemical sensors to detect various harmful gases, such as NH3, NO2, and VOCs19. Nevertheless, previous studies reported that gas-sensing devices using simply a 2D TMD material typically have a high electrical resistance and lack of selectivity and/or recovery to target analytes, especially at room temperature19, impeding their practical sensing applications to IoTs. To further improve their room-temperature sensing performance, 2D-TMDs have been fabricated vastly as alloy-based heterostructures (e.g., Mo(Se,S)2, WS2xSe2-2x)20, or incorporated with noble metallic nanoparticles (e.g., Ag, Nb, Pt)21, metal oxides (e.g., SnO2, ZnO, TiO2, Bi2O3)22, conducting polymers23, or graphene (or its derivatives)24.

In summary, both MXenes and TMDs proved to have device-beneficial physical and chemical properties (e.g., tunable band structures and microstructures), and each class of compounds has been individually studied extensively in recent years25,26. Incorporating TMD with MXene thus could be an effective strategy to further improve the room-temperature sensing performance of devices for VOCs. Besides hybrid MXene/TMD composites not being investigated for gas-sensing applications to date, most sensors reported in literature are fabricated by manual procedures, such as drop-casting, that can only be useful for laboratory scale production and suffer from lack of repeatability and precision. The lack of a pathway toward large-scale production is one of the main roadblocks toward bringing more sensors from the laboratory to the market, and one of the challenges we are addressing herein. The main approaches to synthesizing 2D functional materials are micromechanical exfoliation, liquid-phase exfoliation, ion intercalation-exfoliation, chemical vapor deposition, and wet chemical synthesis from molecular precursors27–29. Among these approaches, liquid-phase exfoliation appears to be the leading reliable, mass-production method for the wide-spread applications to gas-sensing devices. Such method avoids the use of dangerous air-sensitive reagents and undesired property changes. Likewise, inkjet deposition of exfoliated materials is also a facile and repeatable process to fabricate devices at large scale.

Herein, we report on the synthesis of MXene (Ti3C2Tx) nanosheets and TMD (WSe2) nanoflakes both through liquid-phase exfoliation, inkjet printing of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 hybrid sensors for selective detection of oxygen-containing VOCs and a sensing mechanism for the enhanced oxygen-based VOCs detection with Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids. Moreover, inkjet printing offers repeatability of electrode fabrication and reproducibility of the sensing measurements, and is one avenue toward large-scale manufacturing of electrochemical sensors. We report on a sensing material design for gas-sensing application based on integrating the merits of two components: Ti3C2Tx nanosheets, with effective charge transfer, and WSe2 nanoflakes, with abundant active sites for gas adsorption. The Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids show a unique morphology with numerous heterojunction interfaces, consequently facilitating a selective detection of oxygen-containing VOCs. The Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 hybrid sensors exhibit an over 12-fold increases in ethanol sensitivity compared to pristine Ti3C2Tx sensors. In addition, ultrafast response (9.7 s) and recovery (6.6 s) properties are achieved. We propose a sensing mechanism that is likely involved in the detection of oxygen-containing VOCs with Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 heterojunctions and explains the observed enhanced sensing performance. A mass-production integration process (liquid-phase exfoliation and inkjet printing) and wireless operation of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors at room temperature is demonstrated, thus opening an effective avenue for the development of high-performance sensing devices for next-generation IoTs.

Results

Sensor design

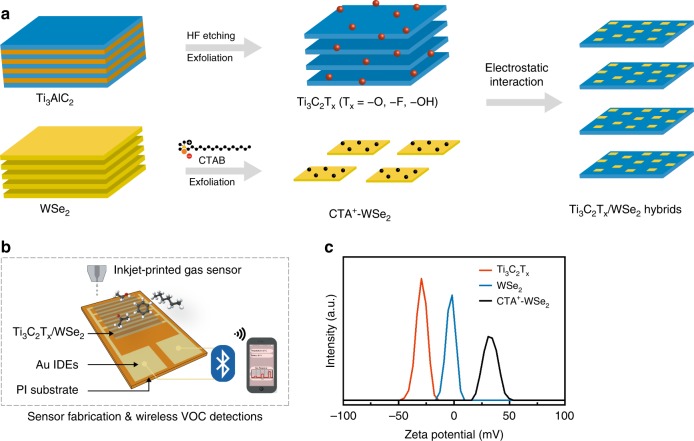

Figure 1a illustrates the process flow of preparing (1) Ti3C2Tx nanosheets from sequential etching and exfoliating of Ti3AlC2 powders and (2) CTA+-WSe2 nanoflakes from CTAB functionalized WSe2 powders, followed by a solution mixing method to form Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids. The Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids were further prepared as ink for the inkjet printing and the fabrication of flexible VOC sensors operating at room temperature using a wireless monitoring system (Fig. 1b). As evidenced from Supplementary Fig. 1, the thickness of the inkjet-printed Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 layers was controllable by the number of printing passes, with a thickness of ~60 nm per print pass.

Fig. 1. Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 hybridization and sensor fabrication.

a Schematic illustration of preparation processes for Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids. b Schematic illustration of inkjet-printed gas sensors in detection of volatile organic compounds with a wireless monitoring system. c Zeta potential distributions of Ti3C2Tx, WSe2, and CTA+-WSe2 dispersions.

The functional block diagram and photographic image of the flexible wireless sensor system (Supplementary Fig. 2), along with a homemade sensor testing system (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1), are detailed in Methods. The feasibility of these processes to form the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids via electrostatic attraction can be evidenced from 80%-potential measurements shown in Fig. 1c. The as-prepared Ti3C2Tx nanosheets are characterized by a negative charged surface with zeta potential of −29.5 mV, which could be attributed to the negatively charged −OH and −O species terminated on Ti3C2Tx surfaces (verified later by XPS). On the other hand, the zeta potential of the pristine WSe2 was only −1.5 mV. After exfoliation in CTAB aqueous solution, its surface charge was reversed, giving a substantial increase of zeta potential to +30 mV. This polarity reversion suggests that CTA+ cations indeed are effectively adsorbed on WSe2 nanoflakes, thereby facilitating the hybridization of Ti3C2Tx with WSe2 through electrostatic interaction.

The formation of as-etched Ti3C2Tx was further verified by XRD shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a. The removal of Al from Ti3AlC2 is revealed by the vanishing of (104) peak at 38.9°, along with the emergence of several peaks characteristics of Ti3C2Tx30. Correspondingly, comparing the SEM micrographs in Supplementary Fig. 4b, c clearly reveals the transition from a bulk to an accordion-like structure upon the transformation of Ti3AlC2 to Ti3C2Tx nanosheets. The theoretical thickness of a Ti3C2Tx single layer is close to 1 nm31, and the MXene nanosheets tend to adsorb water and other molecules, which also add to the total thickness32. Indeed, the AFM height profile measured along the white line in Supplementary Fig. 4c shows that a representative Ti3C2Tx nanosheet has a thickness of ~1.5 nm, which can be regarded as MXene single layer33.

Microstructure analysis of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrid

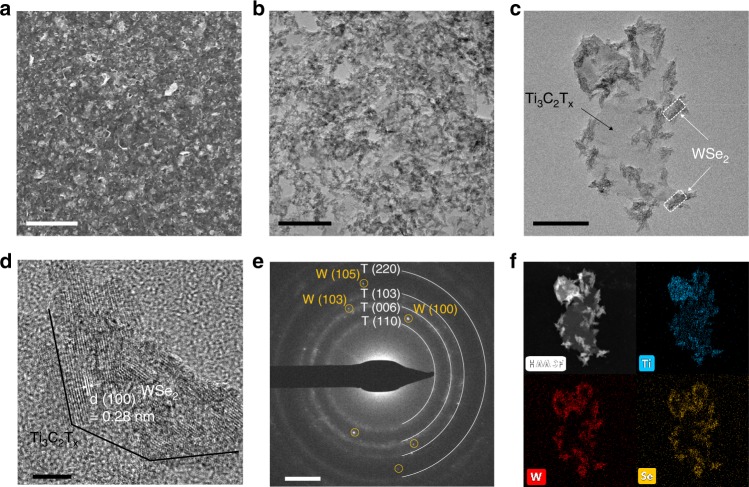

SEM imaging, as demonstrated in Fig. 2a, reveals that the as-printed Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids have a uniform surface morphology over a broad range of the samples area, in spite of the existence of a few pinholes. TEM imaging and diffraction analysis present further insight into the microstructures of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids in Fig. 2b–d. TEM bright-field image (Fig. 2b) shows that WSe2 nanoflakes appear to disperse homogeneously on the Ti3C2Tx matrix. As WSe2 has a large atomic weight, a clear differentiable contrast in this bright-field micrograph is observed, with the darker WSe2 nanoflakes landed on the brighter Ti3C2Tx nanosheets. Such distribution is more obvious in higher magnification TEM image of a single Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrid in Fig. 2c, showing (a) uniform decoration of several even sized (typical < 30 nm) WSe2 nanoflakes on the Ti3C2Tx scaffolds which have a typical size of ~300 nm and (b) the hybridization process forming a numerous heterojunction interfaces that may benefits the gas-sensing performance. The dynamic light scattering measurements (Supplementary Fig. 5) indicate that Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids exhibit an average particle size of 350 ± 100 nm, closely consistent with the TEM imaging analysis.

Fig. 2. Microstructure analysis of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids.

a SEM image of 2D Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrid film (scale bar, 2 μm). b Low magnification TEM image (scale bar, 200 nm), with c showing image of a single Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrid (scale bar, 100 nm). d High-resolution TEM image of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrid (scale bar, 100 nm). e Selected area electron diffraction pattern of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids (scale bar, 2 nm–1). f HAADF-STEM image and corresponding elemental mapping of Ti, W, and Se for the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrid showing a uniform decoration of WSe2 nanoflakes on Ti3C2Tx matrix.

As demonstrated by the high-resolution TEM image in Fig. 2d, WSe2 nanoflakes with a lattice fringe of 0.28 nm were distributed on the edges of the Ti3C2Tx nanosheets, which corresponds to the (100) plane of hexagonal WSe234. Moreover, the associated selected area electron diffraction pattern in Fig. 2e reveals various diffraction rings (denoted as T), indexed as from the matrix of the hexagonal Ti3C2Tx nanosheets. Meanwhile, some diffraction spots (denoted as W) coexist with the continuous rings attributed to the adsorbed WSe2 nanoflakes. To investigate further the elemental distribution of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrid structure, high-angle annular dark-field−scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) imaging and the energy-dispersive X-Ray elemental mapping were carried out, and Fig. 2f presents a representative result, indicating a uniform distribution of Ti, W, and Se within the hybrid.

Chemical composition of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids

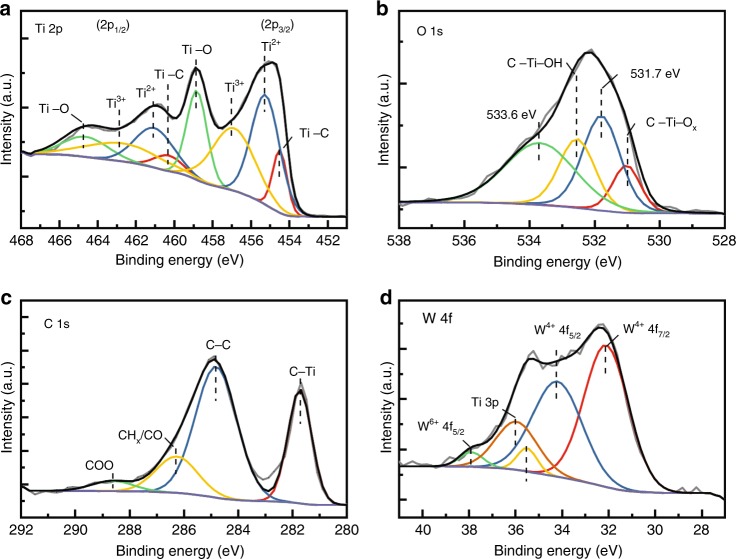

Figure 3a–d shows a set of high-resolution XPS spectra (Ti 2p, O 1s, C 1s, and W 4f) taken from Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids. Interpreting these spectra can identify the chemical structure of WSe2 nanoflakes and Ti3C2Tx nanosheets, as well as the successful fabrication of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids. The Ti 2p spectrum (Fig. 3a) was fitted with a fixed area ratio of 2:1 and a doublet separation of 5.8 eV comprising four doublets (Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2). The binding energies of Ti 2p3/2 for Ti−C, Ti2+, Ti3+, and Ti−O are 454.5, 455.3, 456.9, and 458.9 eV, respectively, in agreement with previous XPS studies35–37. Herein, the fresh Ti3C2Tx scaffold was successfully fabricated and it was significantly different from the oxidized MXene where only Ti−O peaks were observed (Supplementary Fig. 6)37. The O 1s spectrum in Fig. 3b can be deconvoluted into four peaks centered at 530.9, 531.7, 532.6, and 533.6 eV, corresponding to surface species of C−Ti−Ox, C−Ti−OH, adsorbed oxygen and H2O, respectively38,39. This finding confirms that the surface of the Ti3C2Tx nanosheet indeed is terminated by an abundance of functional groups, facilitating its hybridization with WSe2. The C 1s spectrum in Fig. 3c was deconvoluted to four peaks centered at 281.7, 284.8, 286.3, and 288.6 eV, corresponding to C−Ti, C−C, CHx/CO and COO, respectively36. The existence of WSe2 nanosheets is also confirmed by the high-resolution XPS spectrum in Fig. 3d, which shows two main characteristic peaks of W4+ at 32.2 eV (W 4f7/2) and 34.3 eV (W 4f5/2).

Fig. 3. Chemical composition of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids.

High-resolution XPS spectra of a Ti 2p, b O 1s, c C 1s, and d W 4f from Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids, showing chemical components and structures of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids.

Gas-sensing performance of WSe2 decorated MXene sensors

The sensing performance of Ti3C2Tx decorated with various amounts of WSe2 (2 and 4 wt%) toward 40-ppm ethanol was first examined using individual Ti3C2Tx and WSe2 sensors as references. A detailed account of the results is presented in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 7a–d and Supplementary Note 2). The response of both Ti3C2Tx and WSe2 sensors is inferior to that of Ti3C2Tx loaded with a moderate amount of WSe2 nanoflakes (2 wt%), the latter showing the strongest and fastest response toward ethanol. It can be observed that the ethanol response decreases as the WSe2 loading increases from 2 to 4 wt%, which is attributed to the excessive number of WSe2 nanoflakes blocking heterojunctions of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 hybrids (proposed as the major adsorption sites), as also observed from HAADF-STEM images (Supplementary Fig. 7f, g). Their electrical noise was further determined by measuring the response fluctuation during sensor exposure to air. The electrical noise levels of WSe2, Ti3C2Tx, and Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 (2 wt%) sensors were ~1, 0.08, and 0.15%, respectively; the high noise level registered for WSe2 limits its use for high-performance sensors and stems from its high electrical resistance. Moreover, sheet resistance (±1σ; N = 3) of the pristine WSe2 films was 26.3 ± 5.2 MΩ per square, while that of the Ti3C2Tx films loaded with 2 wt% WSe2 dramatically reduced to 3.3 ± 0.5 kΩ per square; this is more than four orders of magnitude decrease in sheet resistance (equivalent increase in the electrical conductivity), owing to the hybridization of WSe2 with Ti3C2Tx with high metallic conductivity. Notably, the sensor based on Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids not only exhibits the highest gas response, but also displays a low-electrical noise, further cementing the finding that the hybridization of MXenes to a TMD material yields superior VOC sensing performance in conductometric devices compared to individual MXene and TMD.

The thickness of sensing films deposited on electrodes in such devices is another key factor affecting performance40,41. Thus, gas-sensing performance of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 films with thicknesses of 60, 120, and 180 nm was examined by comparing their response curves toward the detection of 40-ppm ethanol and acetone (Supplementary Fig. 8). The response of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors to both VOCs decreased dramatically with increasing film thickness; the ethanol response substantially decreased from −9.2% to only −0.7% as film thickness increased from 60 nm to 180 nm. This is most likely because thickness increase of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 films lowers the surface-to-volume ratio of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 channel, impeding gas uptake and transport within the film.

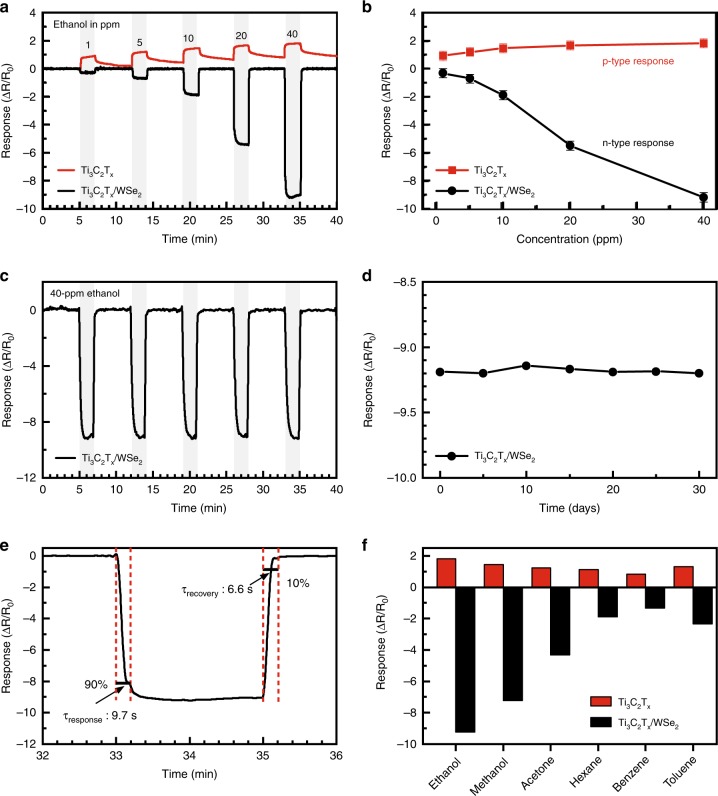

Hereafter, we have fabricated dozens of sensors made of 60-nm-thick Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 electrode; three sensors were subjected to a variety of further sensing tests in parallel each run, using a Ti3C2Tx sensor as reference. The plots presented in Fig. 4 are typical of these measurements. Figure 4a presents sensing properties of pristine Ti3C2Tx and hybrid Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors upon exposure to ethanol vapors over a wide range of concentrations from 1 to 40 ppm. The Ti3C2Tx sensor shows a positive but relatively small increase of resistance to ethanol (p-type sensing behavior), indicating that the charge carrier transport channel is impeded by the adsorption of ethanol molecules. This positive response is ascribed to the metallic conductivity of Ti3C2Tx, where gas adsorption reduces the number of charge carriers (electrons), resulting in an increase of channel resistance42. The unrecoverable response of the Ti3C2Tx sensor is observed by a slight upward drift of the baseline because of the incomplete gas desorption from Ti3C2Tx caused by chemisorption of ethanol43. Interestingly, the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor displays a negative variation of resistance in the presence of ethanol (n-type sensing behavior) in Fig. 4a, implying that the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 heterostructured sensor is dominated by different sensing mechanism compared to pristine Ti3C2Tx. The responses of the Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors with concentration variations of ethanol are shown in Fig. 4b. Notably, standard deviations of the measured response values for the various ethanol concentrations were only 3.7% at most. Such small deviations suggest that the inkjet printing used here indeed offers high repeatability of electrode fabrication, thus giving low device-to-device variations. The response was almost linear and the sensitivity of the sensors here was calculated as the slope (response/ppm), showing a significant increase of sensitivity from 0.02 to 0.24 (12-fold) by the hybridization of Ti3C2Tx and WSe2. The response of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor to ethanol does not reach a saturated state toward 40 ppm of ethanol, indicating that the sensor has a strong ability to detect ethanol molecules over a wide range of concentrations. These enhancements are likely due to the formation of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 heterojunctions, providing not only fast electron transport but also acting as effective catalysts due to its appropriate chemical potential44. Thus, hybridizing WSe2 with Ti3C2Tx significantly enhances the gas-sensing performance and the detailed sensing mechanism will be discussed later in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4. Sensing characteristics of MXene-based VOC sensors.

a Real-time sensing response of Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 gas sensors upon ethanol exposure with concentrations ranging from 1 to 40 ppm. b Comparison of gas response as a function of ethanol gas concentrations for Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors. c Cycling performance of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 gas sensors in response to ethanol at 40 ppm level. d Long-term stability of response over a month under 40 ppm of ethanol for Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor. e Response and recovery times calculated for 40 ppm of ethanol. f Selectivity test of the Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors upon exposure to various VOCs at 40 ppm.

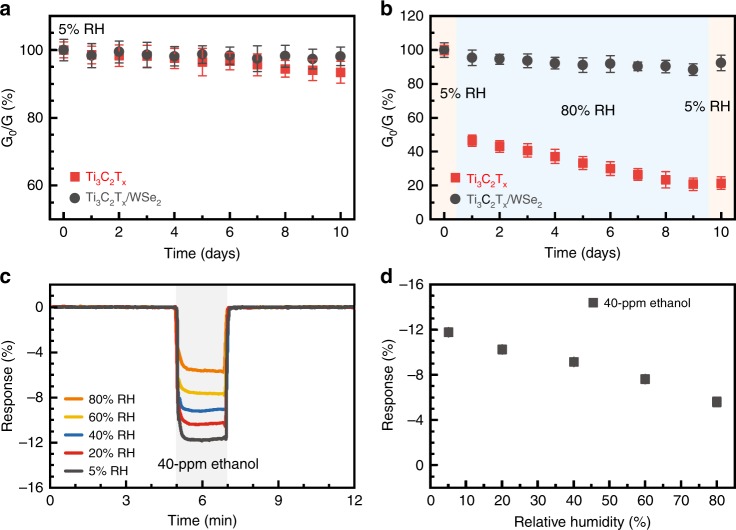

Fig. 5. Environmental stability of Ti3C2Tx and hybrid Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 films.

Changes in electrical conductance of pristine Ti3C2Tx and hybrid Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors under a 5% RH and b alternative RHs of 5 and 80% over 10 days. c Evolution of responses of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors to 40 ppm of ethanol under various RHs and d the sensing responses as a function of RHs from 5 to 80%.

Figure 4c depicts the exposure of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor to 40-ppm ethanol for five consecutive cycles, demonstrating its repeatable, fast gas response and recovery. Moreover, the long-term stability of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor was evaluated upon exposure to 40-ppm ethanol for a month at interval of 5 days (Fig. 4d). The response remained at around −9.2% over a month period, indicating a good long-term stability of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor. This suggests that our hybridization process might also be an effective strategy to overcome the oxidation of MXenes37,45. Fig. 4e shows response/recovery properties of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor toward 40 ppm of ethanol. The response time was defined as the time taken to reach 90% of the maximum gas response after the introduction of a VOC analyte. The recovery time was defined as the time taken to return to 10% of the minimum gas response after the removal of the target analyte. The Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor demonstrated an ultrafast response (9.7 s) and recovery (6.6 s) at room temperature. The enhancement of gas-sensing performance could be attributed to the heterojunction formation that (a) effectively accelerates the transport of electrons and (b) serves as catalyst lowering the activation energy of gas analytes44,46.

To understand further the benefit of hybridizing Ti3C2Tx with WSe2 in the detection of various VOCs, the pristine Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors were exposed to 40 ppm of various oxygen-containing VOCs: ethanol (C2H5OH), methanol (CH3OH), and acetone (CH3COCH3) and carbon-based VOCs: hexane (C6H14), benzene (C6H6), and toluene (C6H5CH3); their response values are presented in Fig. 4f. For each of the individual target analytes, the Ti3C2Tx sensor shows a positive, smaller response value, while the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor shows a negative and much higher response value. In general, the carbon-based molecules’ (benzene, toluene and hexane) interaction with sensing surfaces is minimal, which results in a relatively small resistance variation for both sensors. Both Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors exhibit a slightly higher response to toluene and hexane, as compared to benzene, owing to the presence of their methyl groups, which induces dipole scattering47. On the other hand, the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor exhibits an enhancement in terms of selectivity and sensitivity toward the sensing of oxygen-containing molecules (ethanol, methanol, and acetone). The sensing behavior of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 hybrid sensor to oxygen-containing molecules is rather complicated and has not been well explored.

Environmental and mechanical stability of Ti3C2Tx-based sensors

A serious challenge for Ti3C2Tx nanosheets being used as functional coatings or truly useful device materials is their high susceptibility to environmental degradation under humid atmosphere or in aqueous solution33,48,49. We hypothesize that hybridization with WSe2 could help overcome this challenge. To test this hypothesis, we selected water vapor over a wide range of relative humidity (RH) from 5 to 80% as an interference component and tested the environmental stability of the hybrid Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 film using pristine Ti3C2Tx film as a control. A full account of results is presented in Fig. 5a−d. Figure 5a shows small changes in electrical conductance of Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 films under low humidity (5%) over a period of 10 days, indicating that both films are quite stable in the dry environment. However, after storage in the humid environment with alternative RHs of 5 and 80% over 10 days, electrical conductance of the Ti3C2Tx dramatically decreased to 21% of its original value; by contrast, the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 remained 88% of initial conductance after exposure to 80% of RH, and recovered to 92% in dry environment (Fig. 5b).

To evaluate the effect of humidity levels on gas-sensing performance of the hybrid Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor, we measured its response to 40 ppm of ethanol under various RH levels from 5 to 80%. As revealed by Fig. 5c, d, the response of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor changes from −12 to −6.1% as the humidity level increases from 5 to 80%, indicating that although there is a humidity effect, the hybrid sensor is still functioning well in high humidity environment. The decrease in response is attributed to partial occupancy of water molecules on the sensing sites, causing a decrease in sensing performance50. The results suggest that MXenes indeed tend to oxidize in a humid environment, but adequate loading of TMD nanoflakes to edges of MXene nanosheets provides an effective strategy to block the direct interaction of H2O with MXenes, which thus is an approach to promoting MXene materials for real-life applications.

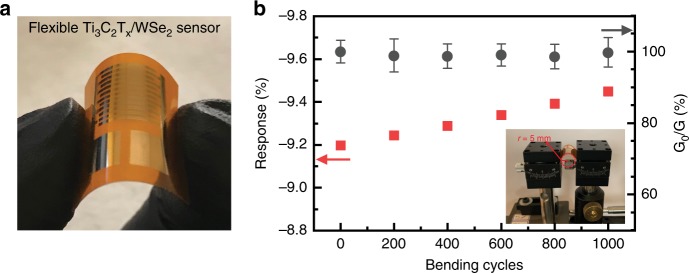

The stability of conductance and sensing response of the fully inkjet-printed flexible Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 (wireless) sensor against mechanical bending was also investigated demonstrating its potential application to IoTs, using ethanol as a target analyte. Figure 6a displays a photograph of the flexible gas sensor. As shown in Fig. 6b, even after 1000 cycles of a bending test with a bending radius of 5 mm, the response of the sensor to 40 ppm of ethanol does not decay; instead, it increased slightly probably due to the creation of bending-induced reactive sensing sites, such as microcracks and wrinkles by the strain force34. Moreover, the electrical conductance of the sensor was rather stable even after 1000 bending cycles (Fig. 6b), indicating good flexibility and high mechanical strength of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor. The retaining of the conductance level on the baseline of the sensor suggests that prolonged bending does not have a negative impact on the sensing properties of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensor.

Fig. 6. Mechanical stability of hybrid Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 films.

a Photograph of a flexible Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrid sensor. b Changes in ethanol sensing response and electrical conductance as a function of bending cycles.

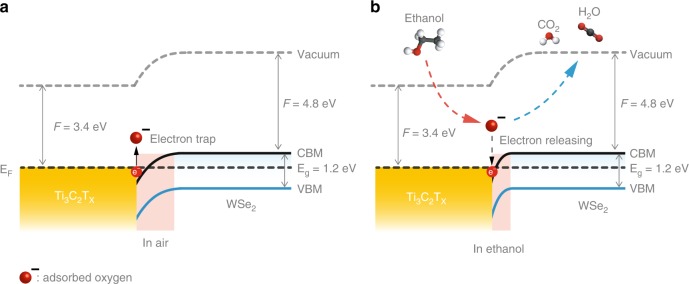

Enhanced sensing mechanism for Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids

Herein, we propose a sensing mechanism for the enhanced oxygen-based VOCs detection with Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids. As shown in Fig. 7a, the band structure of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids, with a partially occupied band crossing the Fermi level, offers a good catalytic effect for enhancements of sensing reactions because the highly conductive Ti3C2Tx nanosheets readily supplies a flow of electrons to WSe244. In fresh air, the electrons were trapped by adsorbed oxygen species (O2− and O−) owing to its electron-deficient nature, thus creating a depletion layer. Upon exposure to oxygen-based VOCs (Fig. 7b), the adsorbed active oxygen species react with ethanol molecules subsequently forming volatile gases (CO2 and H2O) and releasing electrons back to the conduction band, thereby resulting in a reduction in the depletion layer and resistance of the sensor (n-type sensing behavior in Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 channels). Notably, Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids significantly increase adsorbed oxygen species (in turn trap more electrons) because of the numerous heterojunction interfaces formed (as shown from TEM imaging), resulting in a large number of captured electrons released back to the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 channel and thus significantly improving the sensing response and selectivity in detection of oxygen-containing VOCs.

Fig. 7. Enhanced sensing mechanism of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 heterostructure.

Energy-band diagram of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 in a air and b ethanol, showing the variation of the depletion layer with interaction between adsorbed oxygen species and ethanol molecules.

A variety of strategies have been conducted to enhance the gas-sensing performance of 2D TMD, including incorporation of metallic nanoparticles, semiconducting metal oxides, conducting polymers or carbon-based materials20–24. The Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 heterostructured sensors examined here are compared with other representative 2D TMD-based hybrid sensors listed in Supplementary Table 2. Our integration of the solution processing method in the synthesis of a gas-sensing material, namely Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrid, was successful toward the fabrication of flexible VOC sensors using inkjet printing. Importantly, the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors reported herein show either a lower detection limit than most other ethanol sensors, or a higher sensitivity at room temperature. Moreover, we demonstrated ultrafast response/recovery properties, which were not reported in most other publications on the detection of ethanol. In addition, the low-electrical-noise Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrid offers exceptional stability and durability against prolonged mechanical bending and environmental testing, along with the manufacturability of a sensor platform demonstrated, offer a unique opportunity for real-sensing applications to IoTs. For example, the high electrical noise values demonstrated by individual transition metal dichalcogenide materials limit the actual use of such sensors even when laboratory-based performance is adequate. The integration of MXene/TMD hybrid sensors with the features of Bluetooth wireless communication, flexibility and durability shed light on the development of next-generation field-deployable sensor devices suitable for IoT applications.

Discussion

We have reported Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids, fabricated through a facile surface-treating and exfoliation-based process, as sensing materials incorporated in an inkjet-printing and wirelessly-operating sensor for the detection of a variety of VOCs at room temperature. Inkjet printing offers repeatable fabrication of Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors, thus giving low device-to-device variations and reproducibility of the sensing measurements. Compared with the sensors made of pristine Ti3C2Tx and pristine WSe2, the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 hybrid sensor exhibits a 12-fold increase in ethanol sensitivity, low-electrical noise, sound selectivity, and ultrafast response/recovery properties. Moreover, this study sheds light on the hybridization of MXenes with TMDs as sensing materials overcoming the notorious instability and oxidization tendency of individual MXenes, which thus is an approach to promoting MXene materials for real-life applications. The enhancement of the sensing performance to oxygen-containing VOCs is likely due to the numerous heterojunction interfaces formed by Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids and its sensing mechanism is proposed. Thus, the flexible sensors reported here have a high potential for use as practical gas-sensing devices for IoTs. We anticipate that the hybridizing approach of this work would be extended to other 2D MXene materials for sensing applications.

Methods

Preparation of Ti3C2Tx nanosheets, WSe2 nanoflakes, and Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 inks

A total of 5 g of Ti3AlC2 powders (particle size < 40 μm, Carbon-Ukraine Ltd.) were etched in 100 mL of hydrofluoric (30%) aqueous solution and stirred for 24 h at room temperature to remove Al atoms from the Ti3AlC2 powders, Then, the Ti3C2Tx powders were washed via centrifugation several times with deionized water until the pH value of the supernatant reached around 6. The sediment was collected and rewashed with deionized water by vacuum filtration using difluoride membrane with 0.22 μm pore size (Durapore, Millipore), subsequently dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 8 h. The fabrication of Ti3C2Tx nanosheets was performed by sonicating 200 mg of Ti3C2Tx powders in 50 mL of deionized water with ultrasonic bath (Branson, CPX2800H) for 1 h, and centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 1 h to separate the Ti3C2Tx layers. To avoid restacking of the nanosheets caused by the thermal energy released during sonication processing, the bath temperature was controlled at 4 °C. The supernatant containing delaminated Ti3C2Tx nanosheets was collected for further hybridization. The concentration of Ti3C2Tx dispersion was measured by vacuum filtering the colloidal solution (5.1 ± 0.1 mg mL−1). A total of 200 mg of WSe2 powders (99% purity) from Sigma-Aldrich were dispersed in 20 mL of 1% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) aqueous solution followed by sonication at 4 °C for 10 h in an ultrasonic bath. As proven by zeta potential measurements, this treatment results in the adsorption of CTA+ cations onto WSe2 nanoflakes. The functionalized dispersion was sequentially centrifuged at 2000 rpm and 5000 rpm, which narrowed down the size distribution51. The supernatant containing CTA+-WSe2 nanoflakes (1.3 ± 0.1 mg mL−1) was collected for further reaction. A total of 10 mL of Ti3C2Tx (as the hosting matrix of the nanohybrid) aqueous solution were added into CTA+-WSe2 solution at 60 °C and stirred for 2 h to form a Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 hybrid by electrostatic interaction. Ti3C2Tx, WSe2, and Ti3C2Tx nanosheets mixed with 2 and 4 wt% of WSe2 nanoflakes were prepared for sensing performance evaluation. Glycerol was then added to the dispersions with an optimum weight ratio of 1:3, achieving a required viscosity for inkjet printing, which was typically around 10 cP52.

Fabrication of inkjet-printed Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 sensors

Nanogold ink (UTDAu40) from UT Dots, Inc. was printed by a commercial Dimatix DMP-2850 inkjet printer on polyimide substrates containing six pairs of gold interdigitated electrodes (IDEs) with a total active electrode area of 8 mm × 8 mm. Sensing layers of Ti3C2Tx, WSe2 (as references) and Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 were printed, respectively, on the electrode surface of the flexible substrates, which were placed on a vacuum-heated platen and kept at 60 °C to achieve a stable drying rate.

Characterization and gas-sensing measurements

Surface morphology and crystallinity of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; S-4800, Hitachi), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM; Talos 200×, FEI), and X-ray diffractometry (XRD; X’Pert Pro, Panalytical) operated at 45 kV and 40 mA using Cu Kα. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; PHI 5000 Versaprobe, ULVAC-PHI) was used to investigate the chemical components and chemical bonding structures of the Ti3C2Tx/WSe2 nanohybrids. Atomic force microscopy (AFM; Dimension 3100, Veeco) was used in tapping mode to measure film thickness and the profile of the nanosheets. Electrical sheet resistance of the films was measured using a Jandel four-point probe system. The measurements were taken from four different spots on the sample surface and the average values were presented. Dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments) was used to examine the zeta potential and particle size distribution of the materials in aqueous solutions.

Gas-sensing measurements were performed in a homemade sensor testing system (Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Fig. 3, and Supplementary Table 1)53. Briefly, the sensors were placed in a Teflon chamber with gas inlet and outlet pipelines. Mass flow controllers (5850E, Brooks Instruments) were used to control the concentrations of VOC analytes, by adjusting the flow rates of VOC analytes and dilution gas (dry air), with a total flow rate fixed at 500 ml/min. The bubbler containing VOC analytes was set at a controlled temperature to maintain a stable vapor pressure. The gas concentrations were calibrated with a commercial VOC sensor (Honeywell, ToxiRAE Pro PID). Humidity interference tests were performed by introducing a VOC analyte gas into saturated salt solution and the relative humidity (RH) was monitored with a commercially available humidity sensor (HDC 2010, Texas Instruments).

The response of the sensor is defined as:

| 1 |

where Rg and R0 represent electrical resistances of the sensors in the presence of VOC analytes and dry air, respectively.

Wireless gas-sensing system

Electrical signals of the gas sensor were detected by a wireless reading system, and the corresponding functional block diagram and photographic image of the flexible sensor system (connected to the wireless reading system) are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 2. The wireless reading system consists of a wireless transceiver (nRF52832 SoC), a dual readout interface, analog-to-digital converter (ADC; NAU7802), and a highly accurate humidity/temperature sensor (HDC2010) from Texas Instruments. The transceiver features an ultralow-power 32-bit ARM Cortex-M4F microprocessor with a built-in radio that operates in the 2.4 GHz ISM band, and 512 kB flash memory for data logging when the sensor is disconnected from the network. Instant variations of the signals from gas sensors are detected by the analog-to-digital converter and converted to corresponding digital signals by the microprocessor such that they are wirelessly transmitted to a mobile device through the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE). The dual readout interface was implemented by a 2-to-1 analog multiplexer that connects into a Wheatstone bridge with a digital potentiometer controlled by the microprocessor via I2C bus. During operation, the digital potentiometer is adjusted based on the ADC reading to match the resistance of the sensor as close as possible. This readout interface supports dual input with extreme high precision and minimal power consumption. The system is powered by a coin cell battery (cr2032).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Birck Nanotechnology Center, Purdue University, for providing equipment and technical support.

Author contributions

W.Y.C. and L.S. directed the research and experiments; X.J. and D.P. provided the wireless sensing electronics; S.N.L. did the XPS and data analysis; W.Y.C. and L.S. co-wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communication thanks anonymous reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-15092-4.

References

- 1.Swan M. Sensor mania! the Internet of Things, wearable computing, objective metrics, and the quantified self 2.0. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2012;1:217–253. doi: 10.3390/jsan1030217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park J, et al. Wearable, wireless gas sensors using highly stretchable and transparent structures of nanowires and graphene. Nanoscale. 2016;8:10591–10597. doi: 10.1039/C6NR01468B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kampa M, Castanas E. Human health effects of air pollution. Environ. Pollut. 2008;151:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naguib M, et al. Two-dimensional transition metal carbides. ACS Nano. 2012;6:1322–1331. doi: 10.1021/nn204153h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng J, Chen X, Ong WJ, Zhao X, Li N. Surface and heterointerface engineering of 2D MXenes and their nanocomposites: insights into electro- and photocatalysis. Chem. 2019;5:18–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.08.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding X, et al. Defect engineered bioactive transition metals dichalcogenides quantum dots. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:41. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07835-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gogotsi Y, Anasori B. The rise of MXenes. ACS Nano. 2019;13:8491–8494. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b06394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pang J, et al. Applications of 2D MXenes in energy conversion and storage systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:72–133. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00324F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhari NK, et al. MXene: an emerging two-dimensional material for future energy conversion and storage applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017;5:24564–24579. doi: 10.1039/C7TA09094C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anasori B, Lukatskaya MR, Gogotsi Y. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017;2:16098. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin H, Chen Y, Shi J. Insights into 2D MXenes for versatile biomedical applications: current advances and challenges ahead. Adv. Sci. 2018;5:1800518. doi: 10.1002/advs.201800518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinha A, et al. MXene: an emerging material for sensing and biosensing. Trac-Trends Anal. Chem. 2018;105:424–435. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2018.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun W, Wu FG. Two-dimensional materials for antimicrobial applications: graphene materials and beyond. Chem. Asian J. 2018;13:3378–3410. doi: 10.1002/asia.201800851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junkaew A, Arroyave R. Enhancement of the selectivity of MXenes (M2C, M = Ti, V, Nb, Mo) via oxygen-functionalization: promising materials for gas-sensing and -separation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:6073–6082. doi: 10.1039/C7CP08622A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee E, VahidMohammadi A, Yoon YS, Beidaghi M, Kim DJ. Two-dimensional vanadium carbide MXene for gas sensors with ultrahigh sensitivity toward nonpolar gases. ACS Sens. 2019;4:1603–1611. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.9b00303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh HJ, et al. Enhanced selectivity of MXene gas sensors through metal ion intercalation: in situ X-ray diffraction study. ACS Sens. 2019;4:1365–1372. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.9b00310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwivedi P, Das S, Dhanekar S. Wafer-scale synthesized MoS2/porous silicon nanostructures for efficient and selective ethanol sensing at room temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:21017–21024. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b05468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko KY, et al. Improvement of gas-sensing performance of large-area tungsten disulfide nanosheets by surface functionalization. ACS Nano. 2016;10:9287–9296. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b03631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ping J, Fan Z, Sindoro M, Ying Y, Zhang H. Recent advances in sensing applications of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets and their composites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017;27:1605817. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201605817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng S, Lin Z, Gan X, Lv R, Terrones M. Doping two-dimensional materials: ultra-sensitive sensors, band gap tuning and ferromagnetic monolayers. Nanoscale Horiz. 2017;2:72–80. doi: 10.1039/C6NH00192K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joshi N, et al. A review on chemiresistive room temperature gas sensors based on metal oxide nanostructures, graphene and 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Microchim. Acta. 2018;185:213. doi: 10.1007/s00604-018-2750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee E, Yoon YS, Kim DJ. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides and metal oxide hybrids for gas sensing. ACS Sens. 2018;3:2045–2060. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.8b01077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sajedi-Moghaddam A, Saievar-Iranizad E, Pumera M. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide/conducting polymer composites: synthesis and applications. Nanoscale. 2017;9:8052–8065. doi: 10.1039/C7NR02022H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thanh TD, et al. Recent advances in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides-graphene heterostructured materials for electrochemical applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018;96:51–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Ma T, Pinna N, Zhang J. Two-dimensional nanostructured materials for gas sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017;27:1702168. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201702168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong D, Li X, Bai Z, Lu S. Recent advances in layered Ti3C2Tx MXene for electrochemical energy storage. Small. 2018;14:1703419. doi: 10.1002/smll.201703419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan C, Zhang H. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheet-based composites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:2713–2731. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00182F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta A, Sakthivel T, Seal S. Recent development in 2D materials beyond graphene. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015;73:44–126. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2015.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grayfer ED, Kozlova MN, Fedorov VE. Colloidal 2D nanosheets of MoS2 and other transition metal dichalcogenides through liquid-phase exfoliation. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;245:40–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ying Y, et al. Two-dimensional titanium carbide for efficiently reductive removal of highly toxic chromium(VI) from water. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:1795–1803. doi: 10.1021/am5074722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alhabeb M, et al. Guidelines for synthesis and processing of two-dimensional titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene) Chem. Mater. 2017;29:7633–7644. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b02847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding L, et al. MXene molecular sieving membranes for highly efficient gas separation. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:155. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipatov A, et al. Effect of synthesis on quality, electronic properties and environmental stability of individual monolayer Ti3C2 MXene flakes. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2016;2:1600255. doi: 10.1002/aelm.201600255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ko KY, et al. High-performance gas sensor using a large-area WS2xSe2–2x alloy for low-power operation wearable applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10:34163–34171. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b10455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rakhi RB, Ahmed B, Hedhili MN, Anjum DH, Alshareef HN. Effect of postetch annealing gas composition on the structural and electrochemical properties of Ti2CTx MXene electrodes for supercapacitor applications. Chem. Mater. 2015;27:5314–5323. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b01623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah SA, et al. Template-free 3D titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx) MXene particles crumpled by capillary forces. Chem. Commun. 2016;53:400–403. doi: 10.1039/C6CC07733A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu YT, et al. Self-assembly of transition metal oxide nanostructures on MXene nanosheets for fast and stable lithium storage. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1707334. doi: 10.1002/adma.201707334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du CF, et al. Self-assemble and in situ formation of Ni1–xFexPS3 nanomosaic-decorated MXene hybrids for overall water splitting. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018;8:1801127. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201801127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ran J, et al. Ti3C2 MXene co-catalyst on metal sulfide photo-absorbers for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen production. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:13907. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He Q, et al. Fabrication of flexible MoS2 thin-film transistor arrays for practical gas-sensing applications. Small. 2012;8:2994–2999. doi: 10.1002/smll.201201224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim SJ, et al. Metallic Ti3C2Tx MXene gas sensors with ultrahigh signal-to-noise ratio. ACS Nano. 2018;12:986–993. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b07460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dillon AD, et al. Highly conductive optical quality solution-processed films of 2D titanium carbide. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016;26:4162–4168. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201600357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho SY, et al. High-resolution p-type metal oxide semiconductor nanowire array as an ultrasensitive sensor for volatile organic compounds. Nano Lett. 2016;16:4508–4515. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b01713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li B, et al. Asymmetric MXene/monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures for functional applications. Npj Comput. Mater. 2019;5:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41524-018-0138-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao X, et al. Antioxidants unlock shelf-stable Ti3C2T (MXene) nanosheet dispersions. Matter. 2019;1:513–526. doi: 10.1016/j.matt.2019.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cui S, Wen Z, Huang X, Chang J, Chen J. Stabilizing MoS2 nanosheets through SnO2 nanocrystal decoration for high-performance gas sensing in air. Small. 2015;11:2305–2313. doi: 10.1002/smll.201402923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma H, et al. Highly toluene sensing performance based on monodispersed Cr2O3 porous microspheres. Sens. Actuator B-Chem. 2012;174:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2012.08.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang CJ, et al. Oxidation stability of colloidal two-dimensional titanium carbides (MXenes) Chem. Mater. 2017;29:4848–4856. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b00745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Habib T, et al. Oxidation stability of Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets in solvents and composite films. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 2019;3:8. doi: 10.1038/s41699-019-0089-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoppe M, et al. (CuO-Cu 2 O)/ZnO:Al heterojunctions for volatile organic compound detection. Sens. Actuator B-Chem. 2018;255:1362–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.08.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Backes C, et al. Production of highly monolayer enriched dispersions of liquid-exfoliated nanosheets by liquid cascade centrifugation. ACS Nano. 2016;10:1589–1601. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yao Y, et al. High-concentration aqueous dispersions of MoS2. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013;23:3577–3583. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201201843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen WY, Yen CC, Xue S, Wang H, Stanciu LA. Surface functionalization of layered molybdenum disulfide for the selective detection of volatile organic compounds at room temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:34135–34143. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b13827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.