Abstract

Maxillofacial surgery involving part or whole of maxilla involves wide open surgical wounds which need to be protected to prevent disease due to oral contamination and close the communication. The surgical obturator fabricated for the purpose, prior to surgical excision, could be underextended compared to the resected site. The reason for underextension could be attributed to the unintentional extension of the lesion at the surgical table, to prevent metastasis or to avoid recurrences. In such situation, it is essential to fabricate a delayed surgical obturator within a week postsurgically. However, manipulation of surgical site during initial periods of healing would be agonizing to the patient. Management of impression, surgical undercut, support of the graft, and adjacent tissues are of high concern during the initial period of healing. This case series describes the significance of delayed surgical obturator in maxillofacial defect immediate to the postoperative phase.

Keywords: Delayed surgical obturator, Invasive mucormycosis, Maxillofacial defect

Introduction

A maxillofacial defect created due to massive surgical therapy for the removal of cancerous tissue jeopardizes the esthetic and normal function of an individual. The defect created by the surgery makes the oral cavity, maxillary sinus, and nasal cavity as one compartment with the creation of oronasal, oroantral, and oro-orbital communication [1]. These patients suffer from hypernasal speech, nasal regurgitation, and impaired masticatory function postsurgically [2]. Rehabilitation of such defects requires patience and high skill with the primary aim of preserving the remaining structure, comprehensive care so as to decrease the agony to these patients with improved functions [3]. From the day of surgical excision until the removal of surgical pack, it is essential to protect the surgical site, to prevent disease due to oral contamination and close the communication, for which we use surgical obturator.

The surgical obturator reduces the time of patient stay in the hospital which is fabricated prior to surgical excision, but it could be underextended compared to the resected site [4]. The reason could be attributed to the unintentional extension of the lesion at the surgical table, to prevent metastasis or to avoid recurrences. In such situation, it is essential to fabricate a delayed surgical obturator within a week postsurgically [5]. Most of the time delayed surgical obturator is ignored by prosthodontist and managed with immediate surgical obturator lined by temporary soft liner, due to the difficulty faced during the impression procedure. The delayed surgical obturator fulfils the criteria which lacked in the immediate surgical obturator by providing complete seal and support the graft/the flap placed in the defect area. The studies or case report related to delayed surgical obturator is limited, and the knowledge about its fabrication is still in obscure. Hence, this article discusses the five different clinical scenarios and its management with delayed surgical obturators in maxillectomy cases.

Case Report

Case History 1

A 48-year-old male patient was referred from the Department of Otolaryngology for fabrication of immediate surgical obturator prior to maxillectomy. The patient had a diagnosis of invasive mucormycosis in left maxilla and an immediate surgical obturator was planned for left maxilla. In the course of the surgery, the complete left maxilla with the nasal septum was resected and the resection extended slightly into the right maxilla involving the right maxillary incisors also. The floor of the orbit was preserved. The immediate surgical obturator was inserted on the surgical table.

Case History 2

A 52-year-old male patient had diagnosis of fungal osteomyelitis on left side of the maxilla was referred from the Department of Otolaryngology for fabrication of immediate surgical obturator prior to maxillectomy. The treatment planning was to resect left maxilla. On the surgical table, left maxilla was completely resected with slight extension into right maxilla involving right maxillary incisors. The floor of the orbit and part of nasal septum was preserved. Immediate surgical obturator was inserted on the surgical table.

Case History 3

A 51-year-old male patient had diagnosis of fungal sinusitis of anterior maxilla. Since the extension of the surgical site was not sure, the obturator was planned only after completion of surgery. On the surgical table, total maxillectomy of the left maxilla and partial maxillectomy of the right maxilla preserving only the maxillary right second molar was done. Only posterior part of nasal septum, part of hard and soft palate was preserved. A lining was done with mucocutaneous flap.

Case History 4

A 55-year-old male patient with diagnosis of fungal mucormycosis was referred to the Department of Prosthodontics after surgical excision. On examination, bilateral complete maxillectomy up to the level of zygomatic bone involving maxillary alveolus and palatal shelves.

Case History 5

A 39-year-old male patient was diagnosed with fungal sinusitis of left maxilla. Patient was referred for immediate surgical obturator of the left maxilla. On surgical table, left subtotal maxillectomy extending until the floor of the orbit was done with skin graft. The patient was referred back to the Department of Prosthodontics for prosthetic management of the extended defect to prevent regurgitation.

Prosthetic Intervention

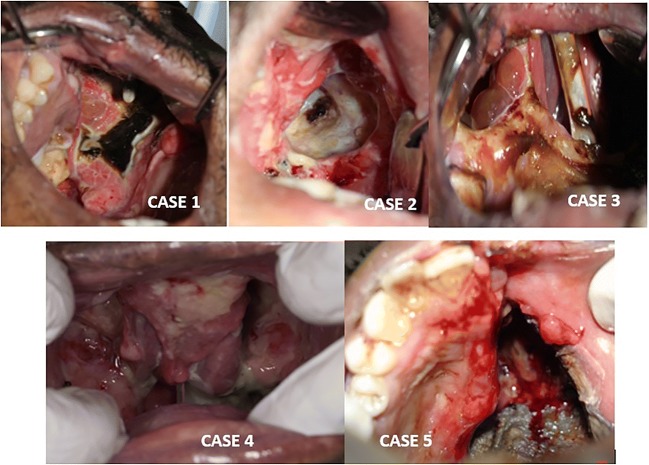

As the surgical site was extensive than planned, the obturator fabricated for cases 1, 2, and 5 was underextended and portion of the resected site was left open to the oral environment, and hence, fabrication of obturator was essential. After the fourth day of surgery, all the patients reported to the Department of Prosthodontics to reevaluate the extension of the surgical site (Fig. 1). Since the resection site was extensive, a delayed surgical obturator was planned.

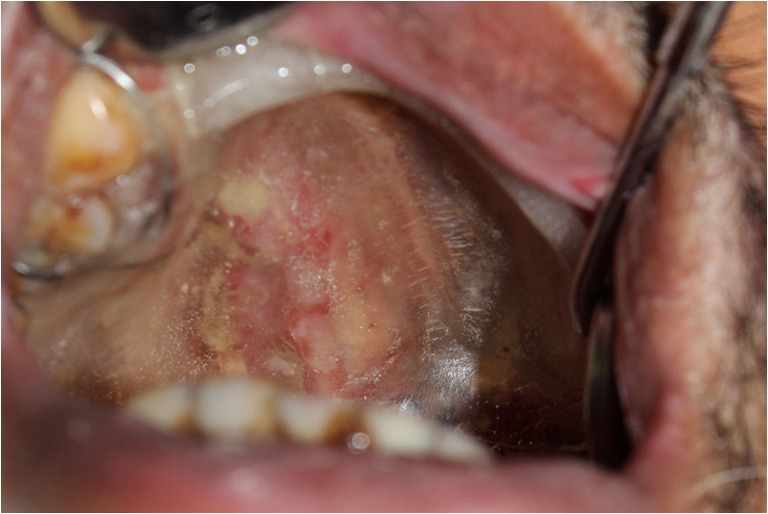

Fig. 1.

Postoperative view of the defect

Impressionless Technique

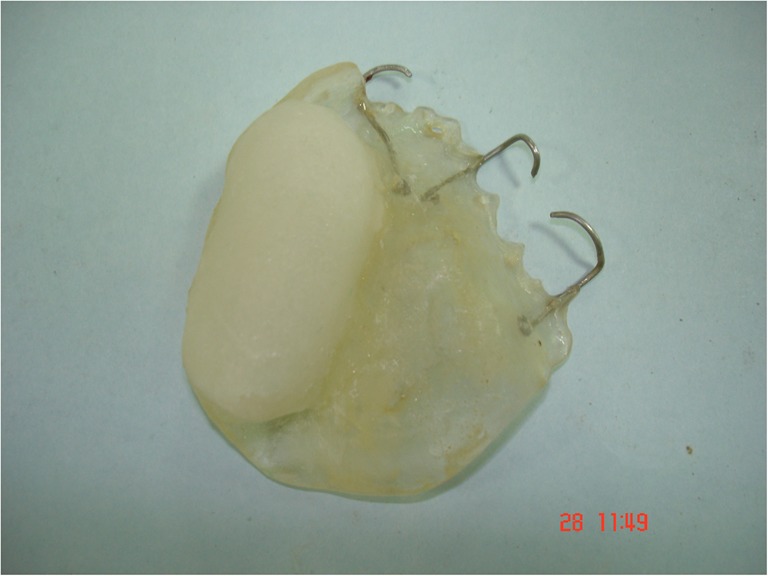

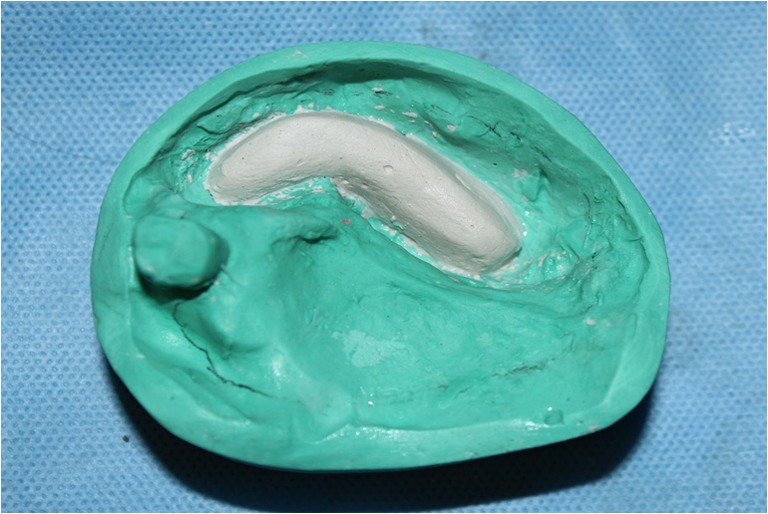

The conventional method of impression making was followed in cases 1–4. Prior to the impression making, care of the freshly wounded resection site was undertaken. The undesirable undercut was blocked with gauze coated with petroleum jelly preserving the defect area, and an impression was made with alginate (Fig. 2). This may not be possible in every clinical situation especially within 7 days of surgery. To avoid the difficulty of taking an impression, impression was avoided in case 5 in which the graft was placed.

Fig. 2.

Impression of the defect area

The length, width, and depth of the defect were measured. Using clear acrylic autopolymerizing resin mixed at dough stage, a bulb was fabricated arbitrarily with the hand dexterity utilizing the dimension measured (Fig. 3) and kept in water bath for curing. The bulb was inserted in the defect area for trial and luted to the surgical obturator using the sticky wax and inserted into the patient mouth for repeat trial. The obturator with the bulb was checked for extension and trimmed to the requirement for proper fit. Later, the plate and bulb was cured together using the autopolymerizing resin (Fig. 4). This is an impressionless technique for fabrication of delayed surgical obturator.

Fig. 3.

Hollow bulb fabrication using arbitrary method

Fig. 4.

Hollow bulb attached to obturator plate

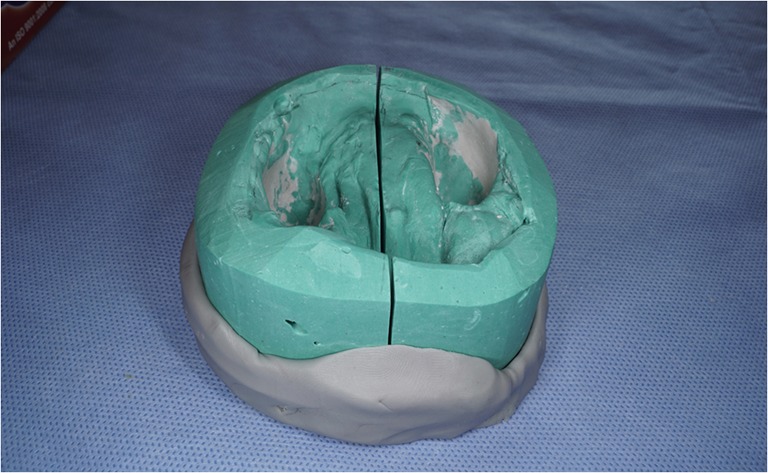

Utilization of Undercut

In an extensive defect, the undercut present would be favorable for retention of the prosthesis, but during fabrication and retrieval, there is probability of fracture of the obturator. Hence, to prevent the breakage of the obturator, die sectioning of cast was planned in case 4. The base for the cast was made by split–cast technique by applying separating medium. Die sectioning of the cast was done at the center of cast, and the two parts of cast was reoriented into the base (Fig. 5). Delayed surgical obturator was fabricated by using clear autopolymerizing acrylic resin extending into the defect area. The method of die sectioning helped in retrieving the obturator form the undercut without any fracture.

Fig. 5.

Die sectioning using split cast method

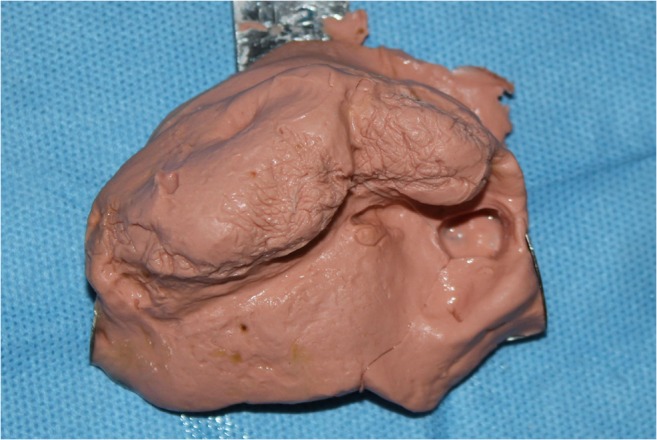

Reduction of Obturator Weight

In all the five clinical scenarios, availability of remaining natural teeth was minimal or not present. For fabrication of the prosthesis, to prevent the leverage effect of prosthesis on remaining natural dentition due to weight of prosthesis, hollow bulb obturator was designed. A plaster pillar (Fig. 6) was built on the defect site leaving 2–3 mm of the borders of the defect [6]. In case of availability of remaining natural dentition, clasps were placed in molar and premolar for the cases 1 and 2 while for case 3, only in left maxillary molar the clasp was fabricated. After the set of plaster pillar, the autopolymerizing resin was flowed between the defect and the plaster pillar to fabricate the hollow bulb for the obturator.

Fig. 6.

Plaster pillar made for hollow bulb

Support to Adjoining Tissues

The obturator provides support in the defect area, but lip and cheek support is essential to maintain the facial contour, esthetics, and prevent scar contraction. The clear acrylic resin was rolled over the ridge mimicking an occlusal rim of approximately 1 cm above the height of the palate (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Bite rims made of acrylic in polished surface for lip support

The obturator was highly polished before insertion (Fig. 8).The delayed surgical obturator was checked for the proper seal, extension, and speech intelligibility. The obturator provided adequate support to the mucocutaneous flap and had perfect extension to the periphery border (Fig. 9). Postinsertion instruction was given, and the patient was reviewed after 24 h. The patient was instructed to remove the obturator and clean after every meal to maintain hygiene of the obturator. The patient was instructed to use the obturator for 2–3 weeks. At the end of third week, the patient acceptance was good. The existing prosthesis was converted into an interim obturator by adding anterior teeth.

Fig. 8.

Tissue surface of delayed surgical obturator with hollow bulb

Fig. 9.

Delayed surgical obturator intraoral view

Discussion

The extensive maxillectomy performed sparing only minimal remaining vital structure challenges both the surgeon and the prosthodontist, especially in cases with fungal infection such as mucormycosis. Predetermining the extension of the lesion preoperatively may not be possible in such cases due to invasive nature of the disease; hence, the obturation provided by the immediate surgical obturator would be ineffectual. In order to cover the inadequate extension of the surgical resected site, soft liner is being used in immediate surgical obturator. The soft liner acts as a carrier of fungal and bacterial growth due to rough surface created by the leaching of the plasticizer and the poor maintenance of the prosthesis hygiene [7]. Whereas, the delayed surgical obturator extends into the defect site without any additional reinforcement and benefits the patient during the swallowing providing comfort reducing hypernasality. The maintenance of the prosthesis is also easy due to well-adapted and highly polished acrylic surface compared to the immediate obturator with soft liner extension.

The impression for delayed surgical obturator is being made within few days of the surgical procedure; hence, the complete extension of the surgical site is obtained. This adequate adaptation provided by the obturator prevents nasal regurgitation and ensures adequate support to the mucocutaneous flap which enables protection to the surgical site during the initial stages of healing [8]. Moreover, the weight of the obturator is less compared to the immediate surgical obturator as there is no addition of soft liner. But the speech intelligibility is poor compared to the immediate surgical obturator, due to the inability to replicate the exact palatal contour. Similarly, there are certain inhibitions in the part of the clinician during the impression procedure due to the apprehension in handling the fresh surgical site, in addition to the patient lack of cooperation [8]. The concept of delayed surgical obturator is overlooked and avoided due to the difficulty associated with the procedure. In this case series, the impression was avoided in case 5 by arbitrary fabrication of bulb mimicking the defect. This methodology can especially be useful in highly apprehensive patient.

During the initial phase of surgical procedure, the maxillofacial patient’s psychological well-being is often collapsed and if the immediate obturator fail to provide adequate seal, this would further deprive their self esteem [9]. The adaptation provided by the delayed surgical obturator obtained could enhance the healing process and provide psychological support to the patient when they are in highly self-deprived state. Since the impression for delayed surgical obturator is done within few days of surgical resection, it is highly recommended to reduce the time duration between an impression and obturator fabrication, as the time lag would result in tissue contraction and edema, making it extremely difficult to insert the obturator [10]. It is also recommended to make new impression in surgical room by which surgeons remove surgical pack when patient is still under sedation [11]. An added advantage with delayed surgical obturator is that it could be easily converted into an interim obturator wherein the extension of the obturator is not compromised until a final prosthesis is fabricated.

Conclusion

Delayed surgical obturator should be a part of treatment modality for the maxillofacial defect patient, so as to ensure adequate esthetic, functional, and psychological outcome with the final definitive obturator. Each clinical scenario needs different treatment planning and care to reduce the discomfort, treatment duration especially when prosthetic management is done within a week of extensive surgery. The present case series also showed that the delayed surgical obturator enabled better uptake of graft by the surgical site and helped in reducing surgical contraction of scar tissue.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Spiro RH, Strong EW, Shah JP. Maxillectomy and its classification. Head Neck. 1997;19:309–314. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199707)19:4<309::AID-HED9>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalian VA, Drane JB, Standish SM (1971) Multidisciplinary practice. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Co; Maxillofacial prosthetics; 133–48

- 3.Mantri S, Khan Z Prosthodontic rehabilitation of acquired maxillofacial defects; In Head and neck cancer. Eds Dr. Mark Agulnik.; 315-336

- 4.Keyf F. Obturator prostheses for hemimaxillectomy patients. J Oral Rehabil. 2001;28:821–829. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2001.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beumer J, Curtis TA, Marunick MT. Maxillofacial rehabilitation: prosthodonticand surgical considerations. St. Louis: Elsevier; 1996. pp. 225–247. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maheshwaran KS, Mohamed K, Subhiksha R, Kumar VA. A simplified novel approach in the fabrication of an interim hollow bulb obturator. Int J Dent Health Sci. 2017;4(5):1227–1232. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munksgaard EC. Plasticizers in denture soft-lining materials: leaching and biodegradation. Eur J Oral Sci. 2005;113:166–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park KT, Kwon HB. The evaluation of the use of a delayed surgical obturator in dentate maxillectomy patients by considering days elapsed prior to commencement of postoperative oral feeding. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;96:449–453. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hickey AJ, Salter M. Prosthodontic and psychological factors in treating patients with congenitaland craniofacial defects. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;95:392–396. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor TD. Clinical maxillofacial prosthetics. Illinois: Quintessence Publishing Co; 1997. p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desjardins RP. Early rehabilitative management of the maxillectomy patient. J Prosthet Dent. 1977;38:311–318. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(77)90308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]