Abstract

Peritoneal surface oncology has emerged as a subspecialty of surgical oncology, with the growing popularity of surgical treatment of peritoneal metastases comprising of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Pathological evaluation plays a key role in multidisciplinary management but there are still many areas where there are no guidelines or consensus on reporting. Some tumors presenting to a peritoneal surface oncology unit are rare and pathologists my not be familiar with diagnosing and classifying those. In this manuscript, we have reviewed the evidence regarding various aspects of histopathological evaluation of peritoneal tumors. It includes establishing a diagnosis, appropriate classification and staging of common and rare tumors and evaluation of pathological response to chemotherapy. In many instances, the information captured is of prognostic value alone with no direct therapeutic implications. But proper capturing of such information is vital for generating evidence that will guide future treatment trends and research. There are no guidelines/data set for reporting cytoreductive surgery specimens. Based on the authors’ experience, a format for handling/grossing and synoptic reporting of these specimens is provided.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13193-019-00897-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cytoreductive surgery, Pathology, Surgical specimens, Data set for reporting, Synoptic reporting

Introduction

Peritoneal metastases (PM) are usually secondary to some common primary tumors like colorectal, ovarian, gastric, breast, and lung. Making a diagnosis of these tumors is not challenging for an oncopathologist. However, when the presentation is of peritoneal carcinomatosis, in the absence of an evident primary tumor, the diagnosis can become challenging. The pathologist must make an accurate assessment of the histological findings, think of the possible primary sites, and perform appropriate diagnostic tests to give a conclusive diagnosis. For some rare tumors that arise from the peritoneum itself or metastasize to it, in addition to making a correct diagnosis, the pathologist must be able to correctly identify the histological subtype/grade of the tumor and test for prognostic markers that will guide treatment decisions. And equally important is coordination with the surgeon who must provide an adequate and appropriate tissue sample/s and relevant clinical information to aid the process.

Cytoreductive surgery has become widely accepted as a potentially curative treatment for selected patients with PM. On an average, every procedure comprises of 2–3 peritonectomies and resection of 2–3 adjacent viscera. For each patient, the number and often the size of the resected specimens is more compared to other common gastrointestinal surgical oncology procedures. Currently, there are no guidelines for handling and reporting peritonectomy specimens which is crucial as the pathological evaluation can provide important prognostic information.

This article provides a synopsis of key elements in diagnosis and reporting of the common peritoneal metastases presenting to a peritoneal surface malignancy unit.

Common Indications for CRS and HIPEC

Looking at the experience of two pioneering centers in the world, at Centre Hospitalier Lyon Sud, the commonest indications for CRS and HIPEC were colorectal (30%), ovarian (24%), and pseudomyxoma peritonei (17%) in 1125 procedures performed over 25 years. [1] In comparison, at the Wake Forest University Hospital, the commonest indications were appendix 472 (47.2%), colorectal 248 (24.8%), and mesothelioma 72 (7.2%) among 1097 procedures performed over 22 years [2]. In 332 patients enrolled in the Indian HIPEC registry till September 2017 and treated between 2013 and 2017, the commonest indications were ovarian cancer in 38.2%, PMP in 27.1%, and colorectal cancer in 18.6% [3]. Rare/uncommon tumors constituted 10% of the patients in each of these series. Further details are provided in Table 1. Thus, across centres, the five commonest tumors remain the same. The procedures at the pioneering centres were performed over a period of more than 15 years and the treatment trends, guidelines, approved indications, and the surgeons’ field of specialization all influence the proportion tumors from each primary site.

Table 1.

Commonest indications for CRS and HIPEC at different centers

| Primary site | Lyon-Sud Hospital (1125 procedures) | Wake Forest University (1097 procedures) | Indian centres (332 procedures) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal | 30% | 24.8% | 18.6% |

| Ovarian | 24% | 6.9% | 38.2% |

| PMP | 17% | 47.2% | 27.1% |

| Gastric | 11% | 7.2% | 5.4% |

| Mesothelioma | 7.5% | 4.6% | 0.6% |

| Uncommon/rare indications | 10% | 9.7% | 9.9% |

Data Set for Reporting Specimens of Cytoreductive Surgery

There are no existing guidelines for reporting of peritonectomy or cytoreductive surgery specimens. In most metastatic cases, the histopathological evaluation comprises only of confirming the diagnosis of metastatic disease and performing biomarker analysis. There are no guidelines regarding how the specimens should be handled, grossed, and what findings should be reported. Peritoneal surface oncology is an evolving field and new prognostic variables continue to be identified. The pathological variables should be incorporated into the reporting guidelines from time to time.

Labelling of Surgical Specimens by the Surgeon

Different regions of the peritoneum are marked by the operating surgeons on the peritonectomy specimens. These recommendations are based on the authors' own experience and not on any guidelines or expert consensus. The peritoneum could be removed as a whole (en-bloc) or different regions separately. The involved viscera resected with the peritoneum are identified and marked as well. The regions are marked according to the five peritonectomies described by Sugarbaker [4]. The list of peritoneal regions included in each of the five peritonectomies is provided in Table 2. Once again, these divisions are not binding and different surgeons may use different sub-divisions. An example of identifying various regions on an en-bloc peritonectomy specimen is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Peritoneal regions included in the five peritonectomies described by Sugarbaker

| Peritonectomy | Peritoneal regions |

|---|---|

| Pelvic peritonectomy | Bladder peritoneum |

| Right and left pelvic peritoneum | |

| Pouch of Douglas | |

| Bilateral anteroparietal peritonectomy | Paracolic peritoneum (right and left) |

| Anteroparietal peritoneum (right and left) | |

| Right upper quadrant peritonectomy | Right subphrenic peritoneum |

| Morrison’s pouch | |

| Right Glisson’s capsule | |

| Left upper quadrant peritonectomy | Falciform ligament and tissue in umbilical fissure |

| Central diaphragmatic peritoneum | |

| Left subphrenic peritoneum | |

| Left Glisson’s capsule | |

| Greater omentum | |

| Omental bursectomy | Lesser omentum |

| Omental bursa | |

| Pancreatic capsule | |

| Hepatoduodenal ligament |

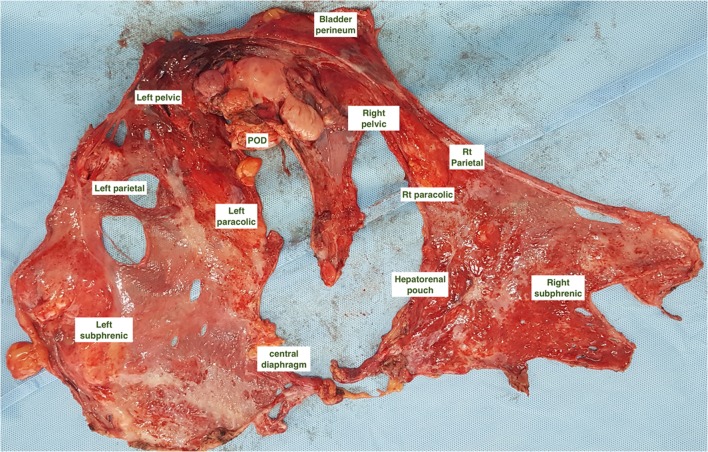

Fig. 1.

Various regions of the peritoneum marked on an en-bloc total parietal peritonectomy specimen performed for serous epithelial ovarian cancer

The Glisson’s capsule is identified separately from the right upper quadrant peritonectomy specimen. Other peritoneal regions like the pancreatic capsule, omental bursa, hepatoduodenal ligament, and areas of mesenteric peritoneum are identified separately.

Ideally, to provide more comprehensive clinical information to the pathologist, a morphological description of the tumor in each region is provided as follows

Discrete tumor nodules

Confluent nodules

Plaques

Omental cake

Adhesions

Scarring

Thickened peritoneum

Normal peritoneum

Handling of Specimens

Fixation is performed as early as possible, ideally within few, to prevent any degradation of proteins and nucleic acids that might occur during cold ischaemia especially when biomarker evaluation is contemplated [5, 6]. Fixation in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (4% formaldehyde solution) is performed for 6–48 h [7]. Longer or shorter fixation times may adversely affect biomarker testing, whereas underfixation can result in poor tissue morphology [8]. Acidic fixatives (e.g., Bouin) can cause rapid degradation of nucleic acids and accelerated fixation with heated formalin can lead to alteration in tissue morphology and should not be performed [9, 10]. After sectioning, the specimens are embedded in paraffin [11].

We have created a format for synoptic reporting which is provided in supplementary material 1.

Gross Description and Sectioning

The pathologist describes the gross findings in each region in detail comprising of the following.

Peritonectomy specimen/s

The size (in millimeters) of the specimen and integrity

The presence or absence of tumor

A description of the tumor deposit- discrete nodules, confluent nodules, plaques

The maximum diameter of the largest tumor nodule (in millimeters)

The presence or absence of other nodules

One to three sections are taken from the largest nodule depending on the size of the nodule. Additional sections may be taken from one of the adjacent nodules and from the normal peritoneal surface. Currently, the therapeutic implications of such information are not known. For plaques and confluent nodules, one or two sections are taken form the whole plaque/region. In the absence of gross tumor, the clinical history is considered. If chemotherapy has been administered before, a minimum of five sections is taken from the region to designate a complete response. This recommendation is extrapolated from the guidelines for documenting a complete response in rectal cancer [11]. If no prior therapy has been given and normal peritoneal has been resected, 1–2 sections from the region could be taken.

Adjacent Lymph Nodes

Many a times, the adjacent fat is removed along with the peritonectomy specimen. This is evaluated for the presence of lymph nodes. The lymph nodes are counted and a gross description provided similar to the reporting of other regional nodes. Standard criteria for sectioning of nodes are followed.

Adjacent Viscera

Adjacent viscera are examined for the presence or absence of tumor deposits.

The size of the largest nodule and the number and distribution of the nodules are provided. The presence or absence of tumor at the margins of resected ends of bowel is mentioned. Sections from the area of deepest infiltration of the organ and two adjacent areas are taken. The evaluation of lymph nodes in the attached mesentery is performed as in case of a primary tumor in the bowel even if the same is absent.

Evaluation of the Omentum

The international collaboration on cancer reporting (ICCR) has laid down guidelines for handling of the omentum in ovarian cancer and the same is described here [12]. Three dimensions of the omentum should be provided. The size of the specimen can be helpful to determine the extent of sampling for histological examination. In the setting of a grossly involved omentum, submitting one block for histological examination is considered sufficient [13, 14]. In patients who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, where histological assessment of tumor response to therapy is needed, examination of 4–6 blocks/sections of omentum is recommended [12].

Microscopic Findings

The microscopic findings should include the following:

The histological tumor type

Histological differentiation

Presence or absence of organ infiltration and its depth

Chemotherapy response grade (following neoadjuvant systemic/regional chemotherapy)

Resection margins (resected ends of bowel)

Lymph node status (region, number present, number involved)

Lymphovascular and venous invasion

Ascitic fluid and peritoneal washings

The requirements specific to each disease are described in the respective sections (below).

Peritoneal Fluid Cytology

The sampling of peritoneal fluid should be performed soon after opening the abdominal cavity. The fluid is obtained by peritoneal lavage or sampling of the ascetic fluid if present. To perform a peritoneal lavage, 200 ml of isotonic saline solution (NaCl 0.9%) is instilled into the abdominal cavity (50 ml for each quadrant: right upper, right lower, left upper, and left lower) [15]. After 2 min, 50 ml of fluid is taken out from the pelvis and is centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. The cell pellet is aspirated, smeared onto a glass slide, and fixed with methanol. Smears are stained with a 5% Giemsa solution. It is preferable to use all three stains- Geimsa, hematoxylin and eosin and papanicolaou. Positive cells are abnormal epithelial cells characterized by large size, abnormal nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio or enlarged nucleus and pleomorphism. A single three-dimensional cluster is considered positive. In doubtful cases, cell block should be prepared and relevant immunohistochemistry performed. [16]

Disease-Specific Concerns and Recommendations

Colorectal Peritoneal Metastases

Colorectal PM can be synchronous and metachronous. There are world health organization guidelines (WHO) guidelines and datasets for reporting of primary colorectal tumors. In case of synchronous PM, a mere histological confirmation of the PM is insufficient. The primary tumor should be reported according to the guidelines with the response to neoadjuvant therapy appropriately described and classified. For PM (both synchronous and metachronous), the additional issues that should be addressed are

-

A.

Histological classification of the peritoneal deposits: All adenocarcinomas are reported according to existing guidelines. There are two histological types that require special mention as the incidence of PM in these patients is higher—mucinous and signet ring cell tumors. The proportion of these tumors in patients with PM undergoing surgery is higher than the usual frequency. Standard diagnostic criteria for classifying a tumor as mucinous or signet ring cell are followed. Mucinous carcinomas are a variant of adenocarcinomas with > 50% composed of extracellular mucin [17]. Signet ring cell carcinomas are a variant of adenocarcinoma with > 50% signet ring cells [17]. Any percentage of signet ring cells should be reported and the exact percentage documented.

-

B.

Evaluation of response to chemotherapy: Neoadjuvant systemic therapy is often used in patients with colorectal PM. The pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) is a known prognostic factor for survival following cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC. Tumor regression results in partial or complete disappearance of malignant cells and replacement of the tumor by fibrous or fibroinflammatory granulation tissue and/or mucinous acellular pools and/or infarct-like necrosis [18]. Residual tumor cells are hyperchromic and usually show nuclear atypia (karyorrhexis, pyknosis, or enlargement of nuclei) and presence of giant cells and apoptotic figures. Tumor cells get replaced by fibrotic scar tissue comprising of fibroblasts and bundles of collagen. The presence of foamy macrophages may help to distinguish chemotherapy-induced fibrosis from fibrous stromal tissue/fibroinflammatory changes that could be confused with a chemotherapy response [19, 20]. Fibroinflammatory changes may be seen around the tumor in absence of any treatment [21]. Necrosis can be seen at the center of the tumor. This type of necrosis which is termed “dirty necrosis,” comprises of nuclear debris in a patchy distribution, with the necrosis admixed and bordered by viable cells. There is a rapid transition from viable cells to dying cells with pyknotic nuclei, to anucleate cytoplasmic outlines. Infarct-like necrosis is a feature more commonly seen in the setting of a in response to chemotherapy [21]. It comprises of large confluent areas of eosinophilic cytoplasmic remnants located centrally within a lesion with absent or minimal admixed nuclear debris. The necrotic tissue is often surrounded by a layer of hyaline-like fibrosis with foamy macrophages. Cholesterol clefts, microcalcifications, and hemosiderin are sometimes present among the outlines of necrotic cells. Another type of response is a “colloid response” or the finding of acellular mucin pools as seen in rectal tumors following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy [22–24]. A complete colloid response may be observed comprising of mucin pools without any tumor cells. Post-treatment mucin pools are less basophilic than untreated colloid carcinomas and may have small areas of fibrosis within them.

There are two scoring systems for classification of the response. In the one from Lyon-Sud hospital proposed by Passot et al., pathological response is based on the determination of the percentage of viable tumor cells with respect to the area of each nodule [25]. The response is classified into three groups; no residual cancer cells in all specimens (complete response), 1 to 49% residual cancer cells (major response), and 50% or more residual cancer cells (minor or no response). For patients with multiple specimens, a mean of values is used to define the pathological response. The classification is based on the classifications used for liver metastases [26, 27]. The other classification from Japan has been extrapolated from the response in gastric cancer and divides the response into four categories [28]. Ef-0 reflects no pathologic response or response in less than one-third of the tumor tissue, Ef-1 means that the cancer is detected in the tumor tissue ranging from one-third to less than two-thirds of the tumor tissue, Ef-2 reflects the degeneration of cancer tissue in more than two-thirds of the tumor tissue, while Ef-3 responds to complete disappearance of the cancer cells.

None of the two classifications has been validated for colorectal PM. The classification by the French group further looks at the type of necrosis extrapolating from the prognostic significance of “infarct-like necrosis” in colorectal liver metastases [29]. The BIG-RENAPE group has devised the following classification for pathological response.

Histological response

No residual tumor cell

< 50% residual tumor cells

> 50% residual tumor cells

Type of regression

Fibrosis

Infarct-like necrosis

Colloid response

It may be reasonable to follow this scheme of reporting until more definitive evidence is available favoring a particular classification. Such information is of prognostic value and may in future be used to guide therapeutic decisions.

Another scoring system has been developed by Solass et al. and is used to evaluate response following pressurized intraperitoneal aerosolized chemotherapy (PIPAC) [18]. The classification is provided in Table 3 and is termed as peritoneal regression grading score (PRGS). Four quadrant peritoneal biopsies are performed and a grade assigned to each region. The recommended minimum size of the biopsy sample is 3–5 mm. The mean score and highest grade are both recorded. This system is used for other peritoneal tumors as well and has not been validated.

Table 3.

The peritoneal regression grading score (PRGS)

| Grade | Peritoneal regression grading score | |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor cells | Regression features | |

| PRGS 1—complete response | No tumor cells | Abundant fibrosis and/or acellular mucin pools and/or infarct-like necrosis |

| PRGS 2—major response | Regressive changes predominant over tumor cells | Fibrosis and/or acellular mucin pools and/or infarct-like necrosis predominant over tumor cells |

| PRGS 3—minor response | Predominance of tumor cells | Tumor cells predominant over fibrosis and/or acellular mucin pools and/or infarct-like necrosis |

| PRGS 4—no response | Solid growth of tumor cells (seen at the lowest magnification) | No regressive changes |

Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

Peritoneal metastases are seen in > 75% of ovarian cancer patients at presentation. In the setting of peritoneal metastases/carcinomatosis, the pathologist plays are role in establishing the right diagnosis and adequate reporting of peritonectomy specimens. The data set for reporting ovarian tumors does not provide guidelines for handling of peritonectomy specimens. The response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (if administered) should be classified and reported in specimens of cytoreductive surgery.

In this section, we discuss two aspects related to ovarian cancer

Distinction between primary and secondary/metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma

Classifying the pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

The distinction between individual subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer and the diagnosis of primary peritoneal carcinoma have been described elsewhere and are beyond the scope of this review.

-

A.

Distinction between primary and secondary/metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma

Most primary ovarian tumors can be distinguished on imaging features and histology. In patients with bilateral ovarian masses with peritoneal metastases, metastases to the ovary should be ruled out. The pathologist is often asked to make a diagnosis on a trucut biopsy performed from an omental cake or the ovarian mass itself and the specimen may not always be adequate. The clinical history, presentation, and imaging findings should be taken into account and immunohistochemistry performed before drawing a conclusive diagnosis. Importantly, the histological features and immunohistochemistry should be considered in conjunction and not separately.

The distinction between a primary ovarian adenocarcinoma and metastatic adenocarcinoma from various sites may be problematic [30]. Metastatic colorectal adenocarcinomas may mimic an endometrioid carcinoma or a mucinous neoplasm of intestinal type, either borderline or malignant.

Distinction between a primary ovarian endometroid carcinoma and colorectal carcinoma is simple as primary ovarian endometrioid carcinomas are usually positive with CK7, estrogen receptor (ER), CA125, and PAX8 and negative with CK20, CEA, and CDX2 while the converse immunophenotype is seen in metastatic colorectal adenocarcinomas [31–33].

This difference is not always clear as the marker profile may vary and ovarian tumors may be CK20 positive and colorectal tumor CK7 positive. Primary mucinous ovarian tumors (Fig. 2) exhibit CK20 positivity, which is usually focal but can be diffuse. Focal and at times diffuse positivity is seen for CEA, CDX2, and CA19.9 as well [9]. This may make distinction from a colorectal tumor difficult. However, the pattern of coordinate expression of CK7/CK20 may be useful [34]. Although either marker can be positive in both tumors, primary ovarian mucinous neoplasms are usually diffusely positive with CK7 while CK20 is variable; conversely, metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma are usually diffusely positive with CK20 and show focal positivity for CK7 [34].

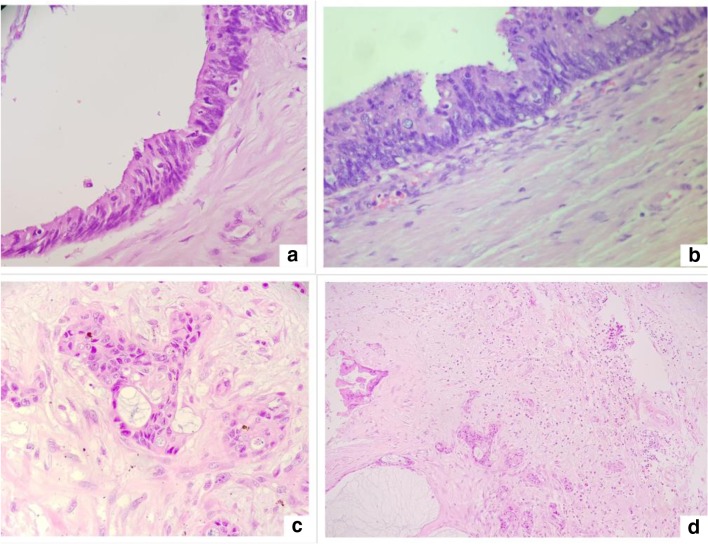

Fig. 2.

Mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colonic variety arising from the ovary

In case of an appendiceal primary tumor with ovarian metastases, the primary may be too small and inconspicuous. In a patient with mucinous ascites and unilateral/bilateral ovarian masses, an appendix primary should be ruled out. Immunohistochemistry can make the distinction in most cases and the marker expression is akin to that in colorectal tumors. In addition to the above panel, SATB2 expression is both sensitive and specific for appendiceal or colorectal origin [35, 36].

There are some histological features that can help in differentiating an ovarian from appendiceal primary. Involvement of both ovaries and surface implants are more likely in metastatic disease [37]. Large size and smooth external surfaces are not always associated with metastatic disease especially in mucinous tumors.

Histologically, features favoring a metastasis to the ovary include retraction artifact separating tumor epithelium from underlying stroma, a scalloped pattern, infiltrative invasion, vascular invasion, hilar involvement, dissecting mucin (pseudomyxoma ovarii), and signet ring cells [38]. In contrast, back-to-back neoplastic glands with no intervening stroma, periglandular cuffing by cellular ovarian-type stroma, histiocyte aggregates, background endometriosis, or associated primary teratomatous elements favor a primary ovarian neoplasm [37–39].

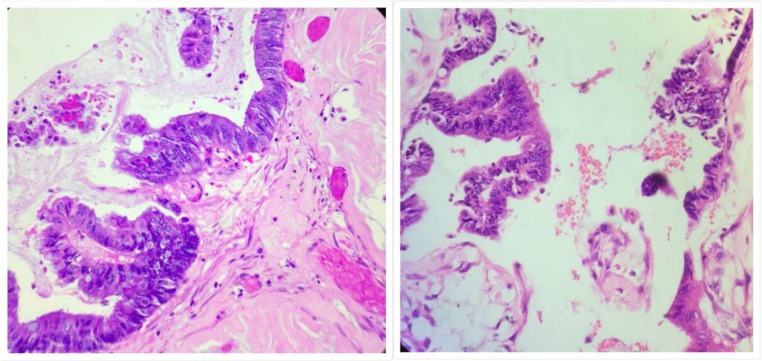

The distinction with pancreatobiliary tumors is also difficult. Most commonly, these tumors are diffusely positive for CK7 while the expression of CK20 is variable (could be negative, focally, or diffusely positive). CEA, CA19.9, and CDX2 may be expressed by these tumors [9]. A correlation with histological findings is essential to establish a diagnosis in these situations. Figure 3 shows histological findings suggestive of a primary tumor arising in the GI or pancreatobiliary tract. The pathologist missed the diagnosis and the patient was subjected to neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by cytoreductive surgery during which a primary tumor was found in the gall bladder. The patient had bilateral ovarian masses and no primary was found in the gastrointestinal tract on preoperative imaging and the gall bladder primary was not detected either.

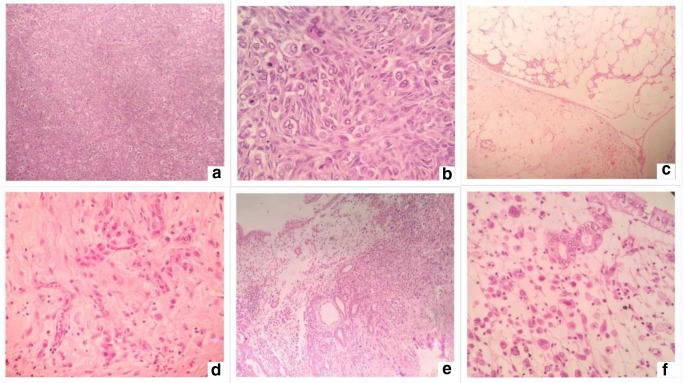

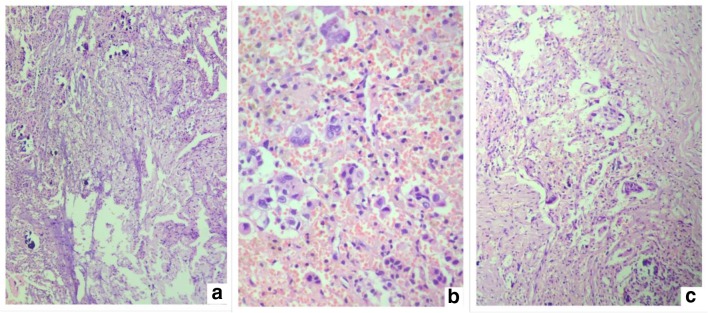

Fig. 3.

Histological findings suggestive of a primary tumor arising in the GI or pancreatobiliary tract. a, b Tumor in the peritoneum. c, d Tumor in the omentum. e, f Primary tumor in the gall bladder

Metastatic breast carcinomas of ductal type can mimic a papillary serous or endometroid ovarian cancer. The finding of a pelvic mass and/or disseminated peritoneal disease is not uncommon in a patient with a history of breast cancer and usually represents a new malignancy of ovarian origin. Yet, the rare possibility of metastatic breast disease needs to be considered and ruled out. PAX-8, CA-125, and WT-1 are positive in serous carcinomas and negative in breast cancer though WT-1 and CA-125 could be positive [40, 41]. Markers useful but not specific for breast cancer are GCDFP15, mammoglobin, and GATA3 (usually negative in serous carcinomas and positive in breast carcinomas) [42, 43]. A similar panel of markers is useful in the distinction between an endometrioid carcinoma and a metastatic breast carcinoma, although WT1 is negative in endometrioid carcinomas and a proportion of these may be mammoglobin positive [43]. The possibility of other primary peritoneal tumors like mesothelioma should also be kept in mind especially when the recurrence is after a long time interval. In an unexpected situation, the histological findings may be overlooked and the diagnosis missed (Fig. 4). Figure 5 shows histological findings in the peritoneal biopsy suggestive of peritoneal mesothelioma 10 years after the initial diagnosis of breast cancer. The cells were immunoreactive for calretenin, WT-1, and CA-125; focally positive for CK-7; and negative for CK-20, CDX-2, ER, mammaglobulin, and PAX-8.

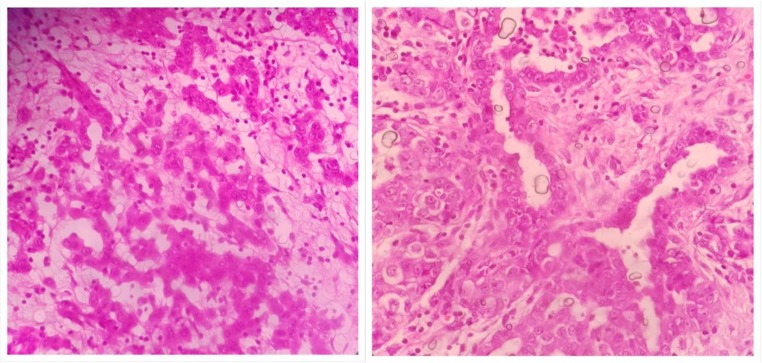

Fig. 4.

Histological findings in the peritoneal biopsy suggestive of peritoneal mesothelioma in a patient with breast cancer

Fig. 5.

CRG 3 in a patient after 3 cycles of NACT. Only site of residual disease is the ovaries. a Residual tumor in the ovary. b Chemotherapy-related changes in the ovary. c, d Chemotherapy-related changes with no residual tumor in different regions of the peritoneum

Rarely, a metastatic cervical adenocarcinoma of usual type (HPV related) in the ovary may mimic a primary ovarian mucinous or endometrioid neoplasm [44]. Diffuse p16 immunoreactivity in such cases may be useful in suggesting a metastatic cervical adenocarcinoma.

-

B.

Classifying the pathological response to NACT

In patients with extensive peritoneal disease, not amenable to CRS upfront, few cycles of NACT are administered before CRS. Some surgeons prefer the NACT approach as it is considered to be less morbid. This gives an opportunity to make an objective assessment of the pathological response to NACT. The 3-tiered score developed by Bohm et al. has been externally validated [9, 45]. This score that was developed from scoring systems for rectal cancer looks at both the residual tumor as well as the architecture and tumor microenvironment in high-grade epithelial serous ovarian cancer. The details of the score are provided in Table 4. In the original score, the term is chemotherapy response score (CRS score). We have used the term “chemotherapy response grade—CRG” to avoid confusion with cytoreductive surgery (CRS).

Table 4.

Chemotherapy response grade based on the score proposed by Bohm et al.

| Criteria for chemotherapy response grade | |

|---|---|

| CRG 1 | No or minimal tumor response. Mainly viable tumor with no or minimal regression-associated fibroinflammatory changes, limited to a few foci; cases in which it is difficult to decide between regression and tumor-associated desmoplasia or inflammatory cell infiltration |

| CRG 2 | Appreciable tumor response amid viable tumor that is readily identifiable. Tumor is regularly distributed, ranging from multifocal or diffuse regression-associated fibroinflammatory changes with viable tumor in sheets, streaks, or nodules to extensive regression-associated fibroinflammatory changes with multifocal residual tumor, which is easily identifiable |

| CRG 3 | Complete or near-complete response with no residual tumor or minimal irregularly scattered tumor foci seen as individual cells, cell groups or nodules, up to 2 mm maximum size. Mainly regression-associated fibroinflammatory changes or, in rare cases, no or very little residual tumor in the complete absence of any inflammatory response. It is advisable to record whether there is no residual tumor or whether there is microscopic residual tumor present |

Regression-associated fibroinflammatory changes consist of fibrosis associated with macrophages, including foam cells, mixed inflammatory cells, and psammoma bodies, as distinguished from tumor-related inflammation or desmoplasia. The following points should be kept in mind while making an inference in the presence of fibrosis [9].

When found in the absence of tumor, fibrosis indicates tumor regression.

If fibrosis occurs in association with tumor, it is tumor-associated desmoplasia rather than regression.

When fibrosis in association with tumor is accompanied by an inflammatory response (so-called fibroinflammatory response—fibrosis with associated macrophages and a mixed population of inflammatory cells), it indicates regression.

Psammoma bodies may mark the site of previous tumor and can sometimes appear more numerous because their density increases in areas where tumor has disappeared (Fig. 5).

This score is based on an evaluation performed at two sites only—the ovaries and the omentum. But it is not specified how many areas are to be evaluated before designating a particular grade to a particular region. The international council for cancer reporting (ICCR) recommends that

A single block of involved omental tissue that shows the least response to chemotherapy should be selected (if there is no residual omental tumor, a CRG score of 3 is given)

The heterogeneity of chemotherapy response is seen in other tumors like breast and rectum and in colorectal PM as well.

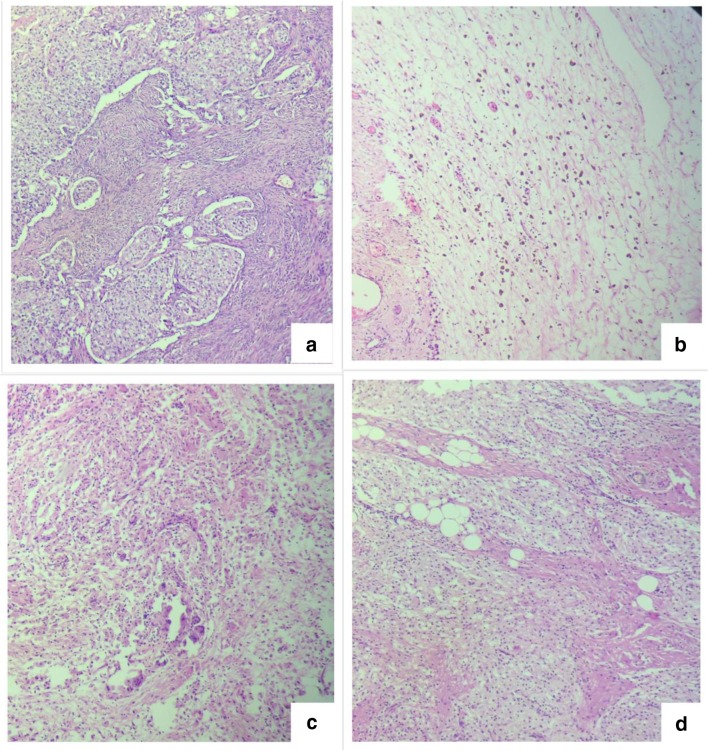

These guidelines do not recommend evaluating the response at the other peritoneal sites. This is an unexplored area. In our preliminary experience, we found a variation in the response at different sites and though the therapeutic implications of such evaluations remain unknown, this is an area that needs further investigation (Fig. 6). Based on the existing evidence and our own experience, we recommend that all resected peritoneal sites are evaluated and scored and the worst score is taken into consideration. There are no therapeutic implications of this score at present—whether a different line of chemotherapy should be used in poor responders has not been addressed. When the impact on survival is evaluated, CRG 1 and 2 are usually clubbed together and compared to CRG 3 [9].

Fig. 6.

Variation in the CRG in different regions of the peritoneum in the same patient. a Minimal response in tumor deposit over the sigmoid colon. b Areas showing no response. c Tumor deposit in the pouch of Douglas showing good response

Other systems of classification of response have been developed but have not been validated. [46, 47]

Pseudomyxoma Peritonei and Appendiceal Tumors

Pseudomyxoma peritonei is defined as a clinical syndrome characterized by the presence of free or organized mucin with or without neoplastic cells in the peritoneal cavity and the typical pattern of redistribution [48]. The most common underlying cause is a mucinous appendiceal tumor which is the source in nearly 95% of the cases. PMP has remained an enigma for surgeons and pathologists due to its varying clinical behavior from a seemingly benign condition to that of an aggressive malignancy. From a pathologist’s perspective, the diagnosis, classification, or grading of the tumor and determining the site of origin are issues that have to be addressed.

The condition has generated more interest over the last 30 years since CRS and HIPEC has been employed as a curative treatment for it and one of the main prognostic factors is the underlying tumor biology. Over this period, several classifications have been developed, used and then gone out of use (Table 5) [49].

Table 5.

A comparison of different classification for appendiceal mucinous tumors and PMP (adapted from reference 49 with permission)

| Comparisons among classification schemes for appendiceal mucinous neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carr and Sobin 2010 [50] | Misdraji et al. 2013 [51] | Pai and Longacre 2009 [52] | Ronnette et al. 1995 [53] | Bradley et al. 2006 [54] | AJCC and WHO 2010 [50, 55] | |

| Tumor confined to the appendix | ||||||

| Limited to the mucosa | ||||||

| Low-grade cytology | Adenoma | LAMN | Adenoma | NA | NA | Adenoma |

| High-grade cytology | Adenoma | Non-invasive mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | Adenoma | NA | NA | Adenoma |

| Positive surgical margin | Adenoma | LAMN | Uncertain malignant potential | NA | NA | Adenoma |

| Neoplastic epithelium in appendiceal wall | Uncertain malignant potential | LAMN | Uncertain malignant potential | NA | NA | Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma |

| Tumor beyond appendix | ||||||

| Low-grade epithelium in peritoneal mucin | Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma | LAMN | High risk for recurrence | Disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis | Low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei | Low-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma |

| High-grade epithelium in peritoneal mucin | Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma | Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma | Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma | Peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis | High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei | High-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma |

Some peculiarities that every surgeon and pathologist treating this condition should be aware of are

Most of the classifications have been developed based on clinical outcomes in PMP arising from appendiceal primary tumors and hence, it is not known whether the prognostic value holds true for other primary sites.

The primary appendiceal tumor and peritoneal disease may have different grades, though in a very small percentage. The grade of the peritoneal disease and not the primary tumor is considered more significant [56, 57].

The PSOGI consensus classification is for PMP arising from appendiceal primary tumors alone [57].

The grade of PMP can vary in different regions in the same patient and hence, the tumor grade based on one biopsy sample and the one that is allotted after CRS may differ [38].

Acelluar mucin in the peritoneal cavity is classified as M1a by the AJCC 8 classification.

The term “mucocoele” is a descriptive term and not a pathological diagnosis.

-

A.

Mucinous appendiceal tumors

Appendiceal tumors constitute 2% of all the colorectal tumors and are broadly classified as epithelial or non-epithelial [58]. Carcinoid tumors are the commonest epithelial tumors followed by mucinous tumors. The mucinous tumors are of particular concern due to their propensity for peritoneal dissemination and PMP. And like PMP, some tumors have very bland epithelium and may be looked upon as benign and the other end of the spectrum comprises of mucinous adenocarcinomas. Despite having bland histopathological features, these tumors can invade through the appendiceal wall, cause rupture of the appendix, and produce peritoneal implants [48].

Mucinous tumors need to be distinguished from benign conditions and appropriately classified. The classification of these tumors has prognostic and treatment implications.

Diagnosis, Classification, Staging, and Grading

An appendiceal tumor is usually an incidental finding in an appendectomy specimen when the surgery has been performed for some other abdominal condition. In patients undergoing CRS for PMP, an assessment of the primary tumor is performed as well.

While evaluating the specimen, the whole appendix with the tumor must be embedded [59].

There are two components to be looked at—epithelium and mucin. The tumor stage depends on both the epithelium and mucin, whichever is present at the farthest site. The tumor grade depends on the characteristics of the epithelium.

The commonly used classification is the WHO classification [50]. In this classification, the presence of mucin/epithelium beyond the muscularis mucosae is considered invasion, and these tumors are classified as appendiceal adenocarcinomas. Tumors (both cells and mucin) which do not breach the muscularis mucosae are classified as low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMN) or adenomas.

In the AJCC-8 classification, LAMNs are considered Tis [60]. T3 constitutes tumor (cells or mucin) breaching the muscularis and into the wall of the appendix but not breaching the serosa. T4a comprises of tumors with mucin and/or cells on the serosal surface. In T4b, the tumor directly involves adjacent organs or structures, including acellular mucin or mucinous epithelium (does not include luminal or mural spread into adjacent cecum). In this classification, adenocarcinomas are grade 2 or 3 depending on the differentiation. What is of concern is that low-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma is used for LAMN interchangeably in this classification.

In the PSOGI classification (Table 6), invasion is defined as the presence of infiltration and only tumors with infiltrative invasion are classified as adenocarcinomas. Features of infiltrative invasion include tumor budding (discohesive single cells or clusters of up to five cells) and/or small, irregular glands, typically within a desmoplastic stroma characterized by a proteoglycan-rich extracellular matrix with activated fibroblasts/myofibroblasts with vesicular nuclei. The presence of mucin and/or cells beyond the muscularis mucosa is not considered infiltrative invasion, and these tumors are classified as low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (if the cytological features are of low grade) (Fig. 7) and high-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (HAMN), for tumor with high-grade cytological features and no infiltrative invasion. The invasion seen in these tumors is termed as “pushing invasion” characterized by tongue-like protrusions, diverticulum-like structures, or broad-front spread of epithelium. Acellular mucin alone also dissects into the appendiceal wall.

Table 6.

PSOGI expert consensus classification of appendiceal epithelial tumors (from ref. 57 with permission)

| Classification of non-carcinoid epithelial neoplasia of the appendix | |

|---|---|

| Lesion | Terminology |

| Adenoma resembling traditional colorectal type, confined to mucosa, muscularis mucosa intact | Tubular, tubulovillous or villous adenoma with low- or high-grade dysplasia |

| Tumor with serrated features, confined to the mucosa, muscularis mucosa intact | Serrated polyp with or without dysplasia (low or high grade) |

| Mucinous neoplasia with low grade cytological features and any of | Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm |

| •Loss of muscularis mucosa | |

| •Fibrosis of submucosa | |

| •Pushing invasion | |

| •Dissection of acellular mucin | |

| •Undulating or flattened epithelial growth | |

| •Rupture of appendix | |

| •Mucin and/or cells outside the appendix | |

| Mucinous neoplasm with architectural features of LAMN and no infiltrative invasion but high-grade cytological atypia | High-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm |

| Mucinous neoplasm with infiltrative invasion | Mucinous adenocarcinoma; well, moderately, or poorly differentiated |

| Neoplasm with signet ring cells (< 50% of cells) | Poorly differentiated (mucinous) adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells |

| Neoplasm with signet ring cells (> 50% of cells) | (Mucinous) signet ring cell carcinoma |

| Non mucinous adenocarcinoma resembling the traditional colorectal type | Adenocarcinoma, well, moderately, or poorly differentiated |

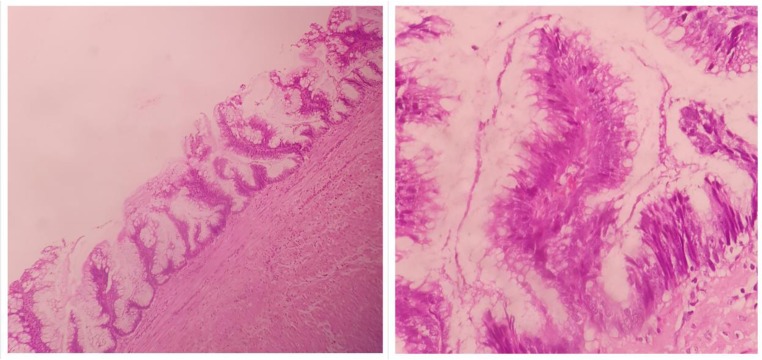

Fig. 7.

Low-grade mucinous appendiceal neoplasm (LAMN) tumor with low grade cytology confined to the mucosa

The term “adenoma” is not used for these tumors and is reserved for tumors resembling colorectal adenomas. Adenomas do not have to the potential to produce PMP. The mucinous adenocarcinomas are further classified as well, moderately, or poorly differentiated. A mucinous adenocarcinoma with < 50% signet ring cells is a mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells and those with > 50% signet ring cells is a signet ring cell carcinoma.

Comparison of the WHO, AJCC, and PSOGI Classifications

From the above description, it is evident that many tumors that would be classified as a mucinous adenocarcinoma by the WHO classification would be a LAMN or HAMN by the PSOGI classification. Similarly, lesions with high-grade cytological features without infiltrative invasion would be classified as adenocarcinomas by the AJCC-8 and HAMN by the PSOGI classification.

Since the management and follow up of these tumors differs, it becomes imperative to use the classification that classifies tumors appropriately. For example, for a LAMN, an appendectomy with free margins is sufficient, whereas for an adenocarcinoma, a hemicolectomy is recommended. Similarly, for a M1a mucinous adenocarcinoma, CRS and HIPEC may be recommended, whereas for a LAMN, just a complete resection may be enough.

Using the AJCC-8, the grade and the stage get combined as one continuum. It is possible that a mucinous adenocarcinoma is confined to the appendiceal wall and is T1 or T2 or T3. There is no clarity how such a tumor should be classified.

Which Classification to Use?

The PSOGI classification is more objective and easy to use as demonstrated by several investigators. However, it does not provide staging information. The purpose of staging is to prognostify the tumor and select the right treatment.

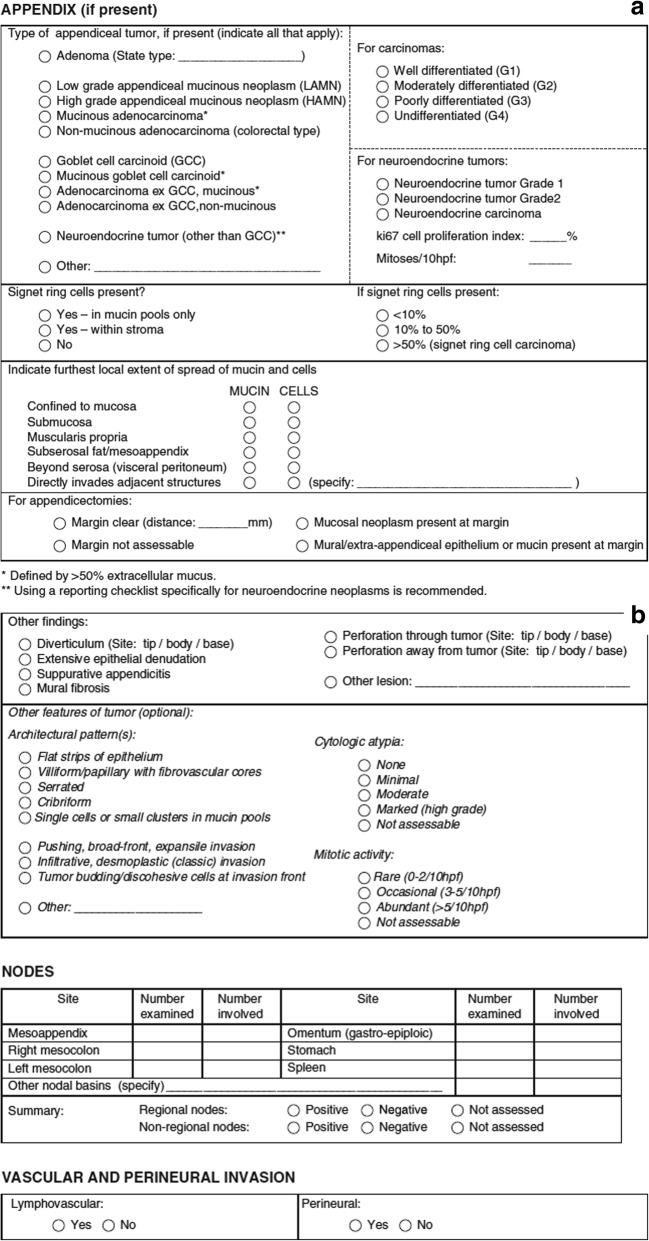

The expert panel that has devised the PSOGI classification has also provided a scheme of reporting (Fig. 8). If this detailed format of reporting is followed, the disease extent will be adequately determined, and there are treatment recommendations for most situations in scientific literature [57].

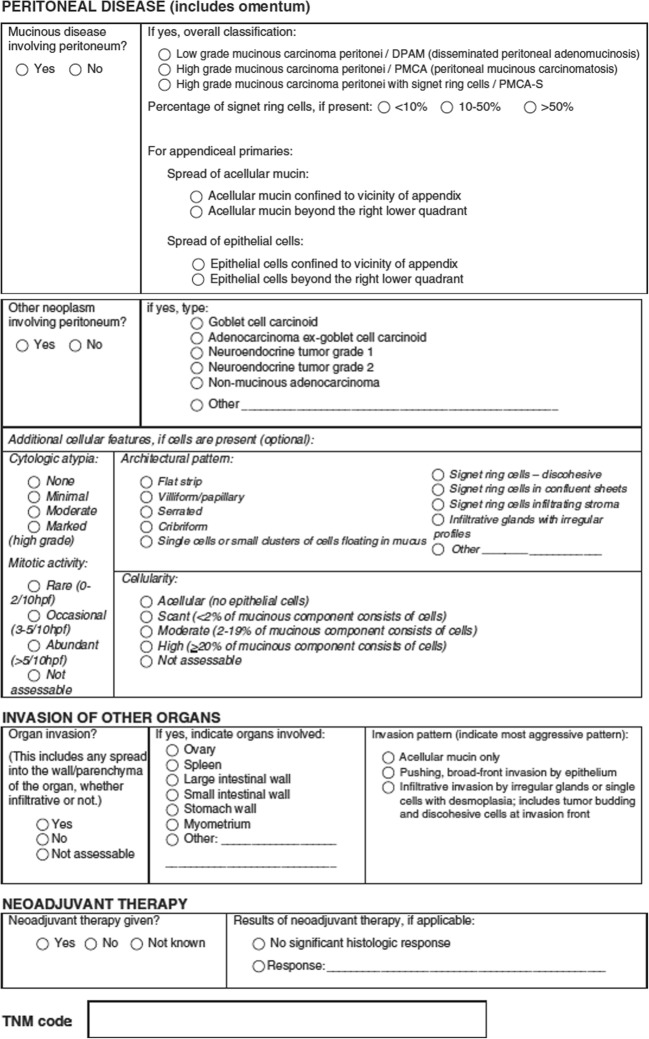

Fig. 8.

a, b Reporting checklist for appendiceal mucinous tumors recommended by the expert panel (adapted from ref 57 with permission)

For example, a LAMN can be perforated or non-perforated [61, 62]. A perforated LAMN is a T4a or T4b tumor if there is no free intraperitoneal dissemination of mucin and/or cells, and these patients can be managed with an appendectomy with free margins and complete resection of the adjacent mesentery and peritoneum [63]. Similarly, a M1a LAMN would undergo CRS and HIPEC [64].

The PSOGI classification also identifies distinct histological entities which would by the WHO classification could fall into either of the groups. The exact incidence and prognostic information about such tumors is not available, but proper identification and classification is the first step toward it. An alternative would be to use the PSOGI classification to classify/grade the tumor and then apply the TMN stage.

Differential Diagnosis

A LAMN must be distinguished from benign conditions like cystic dilatation of the appendix and other inflammatory conditions [65, 66]. Sometimes due to distension of the appendix with mucin, there is extensive ulceration with loss of epithelium [38]. If neoplastic epithelium is not seen on microscopic examination, the diagnosis of a retention cyst or inflammatory mucocele is made. However, these lesions are usually < 2 cm in size [38].

-

B.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei

PMP is a clinical condition and not a pathological diagnosis. However, the term continues to be used in absence of a suitable alternative. The clinical picture of mucinous ascites/peritoneal implants beyond the right lower quadrant should be present for a diagnosis of PMP to be made [38]. The concerns for a pathologist are performing a proper diagnosis and classification. It is not uncommon to receive a sample of mucin aspirated percutaneously from the peritoneal cavity or a trucut biopsy performed from an omental cake. Often, these samples contain only acellular mucin and few or no epithelial cells. Many pathologists continue to report this situation as “adenomucinosis.” The term adenomucinosis is no longer used. Sampling is an important concern in PMP as many of these tumors are paucicellular. Hence, not just the aspirated sample but even a trucut biopsy many contain only mucin and no epithelium. Secondly, different regions may have a different grade and thus the diagnosis made on such samples is always of limited value. The report should mention the gross and microscopic findings in detail, the limitations of a diagnosis made in this manner, and recommend further evaluation.

-

C.

PMP arising from an appendiceal primary tumor

Classification

The term “PMP” is retained in the WHO classification. Tumors with bland epithelium with minimal or no atypical and low cellularity (< 10%) are classified as low-grade PMP and all others as high-grade PMP [50]. Involvement of the surface of organs like the ovaries and the spleen is classified as high-grade PMP.

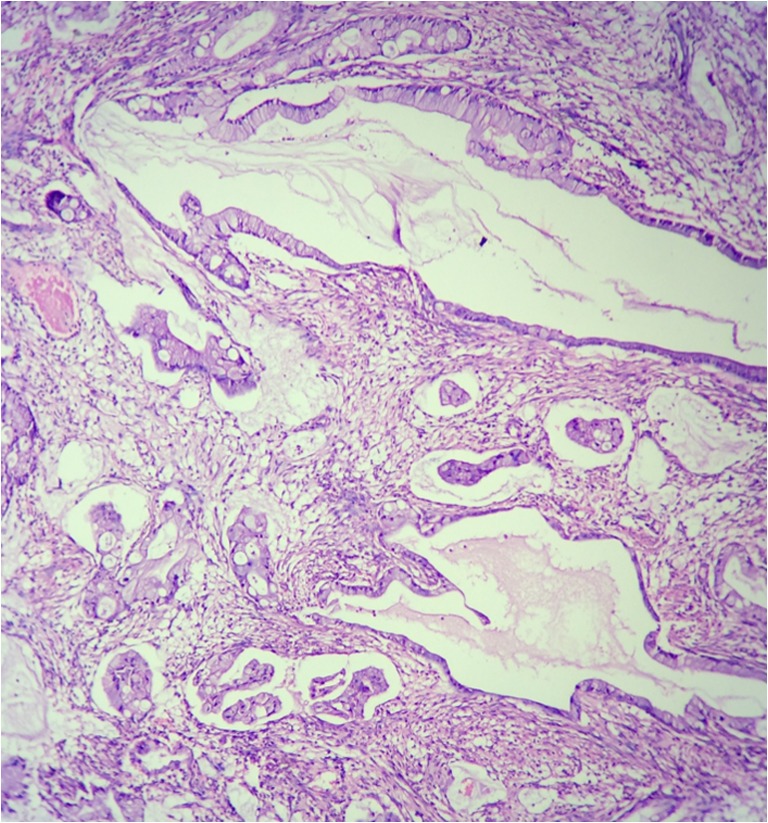

The PSOGI classification divides PMP into four groups namely acellular mucin, low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (LGMCP), high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei (HGMCP), and high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells (HGMCP-S) (Fig. 9) [57]. When mucin shows no epithelial cells in all the areas sampled, the diagnosis of acellular mucin is made (Table 7) (Fig. 10). Classification of other implants is based on the cytological and architectural features of the epithelium—those with predominantly low-grade cytological features and no desmoplasia are classified LGMCP and those with high-grade cytological features with or without desmoplasia are classified as HGMCP. Low-grade cytological features include cuboidal or columnar epithelium with or without pseudostratification, few nucleoli, presence of apical mucin, and few or no mitosis. Papillary pattern with low-grade cytological features is classified as low grade (Fig. 11). High-grade cytological features include architectural complexity, stratification, high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, and mitosis. Lesions with any percentage of signet ring cells are classified as HGMCP-S.

Fig. 9.

High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells (HGMCP-S)

Table 7.

PSOGI expert consensus classification of PMP (from ref. 57 with permission)

| Lesion | Terminology |

|---|---|

| Mucin without epithelial cells | Acellular mucin (a descriptive diagnosis followed by a comment is likely to be appropriate depending on the overall clinical picture. It should be stated whether the mucin is confined to the vicinity of the organ or origin or distant from it, i.e., beyond the right lower quadrant in the case of the appendix. The term PMP should normally be avoided unless the clinical picture is characteristic) |

| PMP with low-grade histologic features* | Low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei or disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM) |

| PMP with high-grade histologic features* | High-grade mucinous carcinoma peirtonei or peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis (PMCA) |

| PMP with signet ring cells | High-grade mucinous carcinoma peirtonei with signet ring cells OR Peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis with signet ring cells (PMCA-S) |

| •Omental cake and ovarian involvement can be consistent with a diagnosis of either low-grade or high-grade disease | |

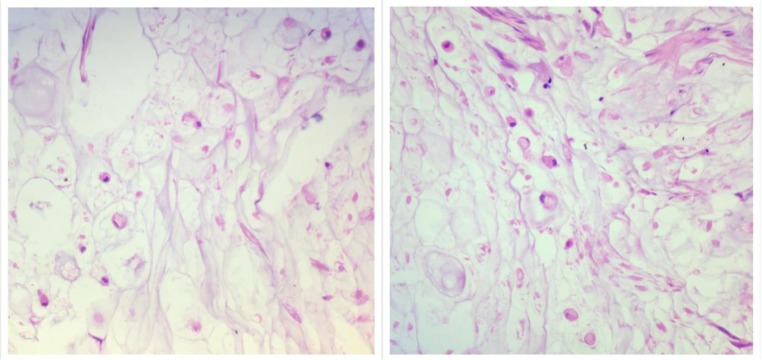

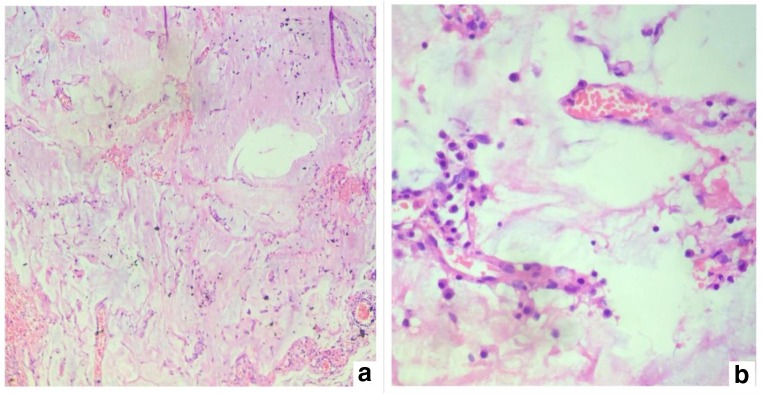

Fig. 10.

Acellular mucin with ingrowth of blood vessels-organizing mucin (a low magnification; b high magnification)

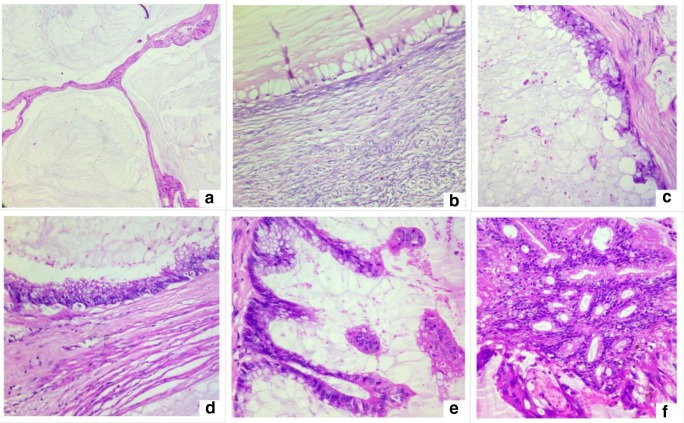

Fig. 11.

Cytological features seen in low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei. a Peritoneal deposit in low magnification. b Tumor deposit on the ovary with pushing invasion. c Single layer of cuboidal epithelium. d Pseudostratified columnar epithelium. e Papillary pattern. f Cribriform architecture with low grade cytological features

Signet ring cells can be present occasionally floating in pools of mucin or there may be numerous cells in mucin or they could be infiltrating the tissue [67]. The occasional cells floating in mucin pools are usually degenerative cells and the expert panel recommends discounting these cells. But numerous signet ring cells and those invading tissues are not disregarded [68, 69]. The exact percentage of these cells should be mentioned. Extensive signet ring cell differentiation in an appendiceal tumor should raise concern for an underlying goblet cell neoplasm [38, 70].

Which Classification to Use

For PMP as well, the PSOGI classification is more objective and easy to follow and we recommend it is followed. With the WHO classification, low-grade tumors would get classified as high grade solely on the basis of organ involvement and this has treatment implications. The terms LAMN and low-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma are used interchangeably; this creates confusion, especially among clinicians who treat PMP occasionally. It would also make it difficult to compare the results from various centres/studies. The expert panel has derived a correlation between the PSOGI classification and the TNM grading system for PMP in which G1 corresponds to low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei, G2 corresponds to high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei, and G3 corresponds to high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells. The PSOGI panel has produced a checklist for histopathological reporting of PMP and its precursor lesions (Fig. 12) [49].

Fig. 12.

Reporting checklist recommended by the PSOGI expert panel

Both classifications have been validated though in one study, the survival did not correlate with the PSOGI grade [71, 72]. The plausible reason may be the small number of patients in the first and last subgroups.

The reporting format for PMP proposed by the expert panel looks at many other features the prognostic significance of which have prognostic value but no therapeutic implications—like cellularity, type of epithelium, and percentage of signet ring cells [73]. We recommend the use of this format of reporting. This will make reporting uniform across centres and lead to capturing of valuable clinical information.

The Spectrum of PMP—the Gray Areas

The division of all tumors into low and high grade is very broad. Though the PSOGI classification has made two groups in addition acellular mucin and HGMCP-S, with the low-grade and high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei, the pathological findings vary.

First is the example of patients with a single layer of cuboidal epithelium which is found in few areas, compared to a situation is which there is florid pseudostratified columnar epithelium [71]. Both these would be classified as LGMCP, but the biological behavior is likely to be different [71]. Several investigators have shown that LGMCP is a heterogeneous group with some tumors following a significantly worse clinical course compared to others [74, 75].

Patients with few foci of high-grade tumor are classified as high grade based on the recommendation of the expert panel (Fig. 13) but not all pathologists prefer to classify them as high grade. Moreover, the biological behavior may be different from those with a high-grade tumor with infiltrative invasion in all regions. With high-grade tumors as well, a disease spectrum may exist. For example, Fig. 14 shows the histological findings in two different areas in the same patient—there are areas of high-grade cytology with pushing invasion and other areas of high-grade cytology with infiltrative invasion.

-

D.

PMP arising from non-appendiceal primary tumors

Fig. 13.

a Low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with small focus of high-grade cytologicy. b On high power

Fig. 14.

The spectrum of high-grade PMP. a, b Tumor deposits in the peritoneum showing high-grade cytology and no desmoplasia. c, d Tumor deposits in the colonic wall showing high grade cytology with infiltrative invasion

Ovarian Primary Tumors

PMP can be secondary to a mucinous tumor arising in a mature ovarian teratoma. These tumors resemble appendiceal mucinous tumors morphologically and on immunohistochemistry [76, 77]. Borderline ovarian mucinous tumors that rupture tend to produce acellular mucinous deposits within the abdomen that do not progress after oophorectomy [38]. Primary ovarian mucinous adenocarcinomas may produce a clinical picture of PMP but the clinical course is usually more aggressive comparable to that of conventional adenocarcinoma rather than low-grade PMP [78]. The PSOGI expert panel recommends submitting the entire appendix for histological examination to exclude the possibility of an appendiceal primary in patients with PMP, even if the appendix is macroscopically unremarkable. A recent evaluation of mucinous ovarian tumors treated with CRS and HIPEC from centers across the world showed a good survival in these patients.

Urachal Primary Tumors

Urachal adenocarcinoma is rare, accounting for less than 1% of all bladder cancers [79]. The urachus is an embryonic remnant resulting from involution of the allantoic duct and the ventral cloaca, which connects the bladder dome to the umbilicus and is found in one-third of adults [80]. It is lined by transitional epithelium that undergoes glandular metaplasia to give rise to mucinous tumors [81]. The urachal tumor either ruptures into the peritoneal cavity or sheds cells into the peritoneal cavity when the intra-tumoral pressure is high without rupture of the tumor resulting in PMP [82]. The spectrum of mucinous tumors that is seen in the appendix is also seen in the urachus though most of the tumors tend to be of a high grade [83, 84]. In some patients, the epithelial cells are described as bland, well-differentiated, and non-invasive and thought to be of borderline malignancy, whereas other may show signet ring cells. Sugarbaker et al. proposed the term “mucinous urachal neoplasms” to be used for the range of mucinous urachal tumors [85].

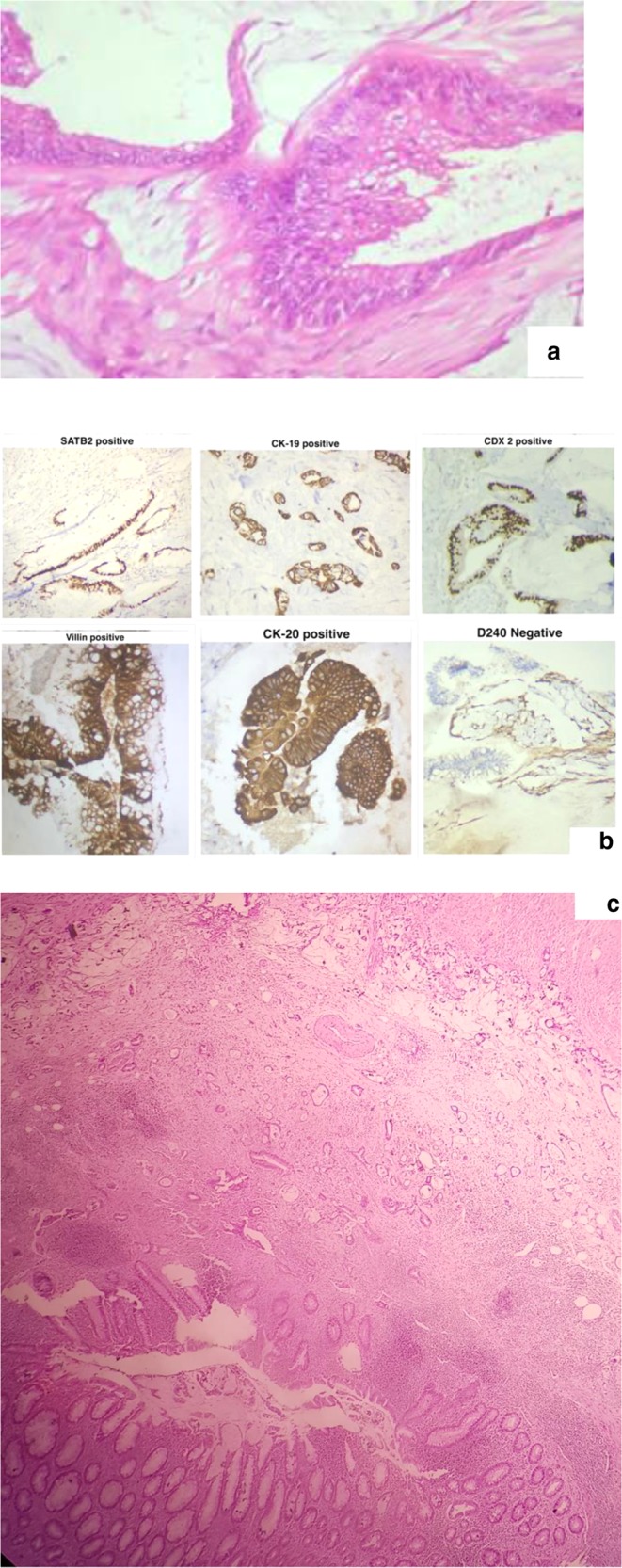

Other Primary Sites

The other common primary sites of origin are colorectal, pancreas, and in some patients the primary site may not be identified though the histology and immunohistochemistry marker profile points to a colorectal/gastrointestinal origin (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15.

Peritoneal deposits from a mucinous adenocarcinoma resembling a colorectal primary tumor but the primary site was not found. a Peritoneal deposits. b Immunohistochemistry profile suggestive of colonic origin. c Appendix showing serosal deposits with a normal mucosa

Peritoneal Mesothelioma

Peritoneal mesothelioma is an uncommon malignancy but not as uncommon for a peritoneal surface malignancy center. It is usually an unexpected finding during investigations performed for another abdominal condition. The pathologist has to diagnose, classify, and prognostify the tumor and be familiar with the common benign and malignant variants.

A history of asbestos exposure should not be taken into consideration by the pathologist when confirming or excluding peritoneal mesothelioma [86]. However, this association is less common than in the pleura. The diagnosis is based on histological features and immunohistochemistry findings. It is recommended that the histological diagnosis of a peritoneal mesothelioma is reviewed by an expert pathologist [86].

Peritoneal mesothelioma can be localized or diffuse. The localized variants are adenomatoid tumors and solitary fibrous tumors and are considered benign in a vast majority of the cases. The diffuse variants comprise of tumors that have borderline malignant potential—multicystic mesothelioma and papillary well-differentiated mesothelioma (WDPM) and the malignant variants that include epitheloid, sarcomatoid, and biphasic peritoneal mesotheliomas. There are histological subtypes of each of these (Table 8).

-

A.

Benign, multicystic mesothelioma

Table 8.

Histological subtypes of malignant mesothelioma

| Histological subtype | |

|---|---|

| Localized | |

| Benign | |

| •Adenomatoid tumor | |

| •Localized fibrous tumor | |

| Diffuse | |

| Borderline | |

| •Multicystic mesothelioma | |

| •Papillary well-differentiated mesothelioma | |

| Malignant mesothelioma | |

| •Epitheloid mesothelioma | |

| •Biphasic (mixed) mesothelioma | |

| •Sarcomatoid mesothelioma |

Benign multicystic mesothelioma is a rare tumor of the peritoneum that has a propensity for recurrence. It is composed of multiple cysts lined with mesothelial cells. The cells are bland and lack significant stratification, papillation, or atypica. For tumors that fulfill these criteria, metastases do not occur [87].

-

B.

Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma

WDPMs have been classified as a separate subtype in the 2015 World Health Organization classification. These are non-invasive papillary neoplasms comprising of bland mesothelial cells and with low-grade nuclear features (small, smooth walled with no nucleoli) [88]. Mitosis are uncommon. WDPMs do not produce high volume disease and this is useful for distinguishing them from tubulopapillary mesotheliomas which they mimic. Invasive foci can occur but are uncommon [89].

-

C.

Epitheloid mesotheliomas

Epithelioid mesotheliomas (MMs) are composed of polygonal, oval, or cuboidal cells that often resemble nonneoplastic, reactive mesothelial cells. This is the most common subtype seen in nearly 80% of the cases. The common secondary growth patterns are tubulopapillary, acinar (glandular), adenomatoid (also termed microglandular), and solid. Some of the distinct pathological findings are psammoma bodies which can be present in any of the subtypes and clusters of tumor cells floating in pools of hyaluronic acid. The less commonly seen histologic sub-types are clear cell, deciduoid, signet ring cell, small cell, rhabdoid, and adenoid cystic [90].

A recently recognized variant is the pleomorphic variant that is characterized by the presence of nuclear pleomorphism in > 10% of the tumor and has the biological behavior of the sarcomatoid and biphasic variants [91, 92]. Similarly, deciduoid MM with pleomorphism is associated with more aggressive behavior [93].

-

D.

Sarcomatoid mesothelioma

Sarcomatoid mesotheliomas usually consist of spindle cells but can be composed of lymphohistiocytoid cells and/or contain heterologous rhabdomyosarcomatous, osteosarcomatous, or chondrosarcomatous elements [94, 95].

Sarcomatoid areas may sometimes be difficult to distinguish from reactive stroma, in which case concordant BAP-1 loss is helpful in reaching a diagnosis.

Secondary patterns of sarcomatoid MM may demonstrate anaplastic and giant cells [96–98].

-

E.

Biphasic mesothelioma

These tumors have both epitheloid and sarcomatoid features. However, unlike the pleural counterparts, there is no minimum cut off for the sarcomatoid features since both varieties have a significantly poorer prognosis [86].

-

F.

Establishing a diagnosis

A definitive diagnosis of MM requires a workup, including IHC and, in some cases, histochemical stains for mucin [99]. The role of IHC varies depending on the histologic type of mesothelioma (epithelioid versus sarcomatoid), the location of the tumor (pleural versus peritoneal), and the type of tumor being considered in the differential diagnosis.

-

G.

Histochemical staining

The cytoplasmic vacuoles in adenocarcinomas frequently contain epithelial mucin which is extremely uncommon in mesotheliomas [86]. This epithelial mucin stains positive with Alcian blue and mucicarmine stains but it is not digested by hyaluronidase. In contrast, mesothelial cells may have vacuoles containing hyaluronic acid that stain positive with Alcian blue and are digestible by hyaluronidase [86]. Mucicarmine may also stain hyaluronic acid in MM; thus, mucicarmine stain is not recommended for distinguishing MM from adenocarcinoma [100]. With widespread application of IHC panels, there is only occasional indication for using histochemical stains, for example, in tumors expressing contradictory immunohistochemical markers.

-

H.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC is both essential for establishing a diagnosis of PM and distinguishing it from other tumors. Immunohistochemical panels should contain both positive and negative markers (Table 9). It is recommended that immunohistochemical markers have either sensitivity or specificity greater than 80% for the lesions in question. Interpretation of positivity generally should take into account the localization of the stain (e.g., nuclear versus cytoplasmic) and the percentage of cells staining.

Table 9.

Commonly used IHC markers for peritoneal mesothelioma

| Immunohistochemistry markers for peritoneal mesothelioma | |

|---|---|

| •Positive markers | |

| Calretenin–tight junction associated protein | |

| Cytokeratins 5/6 intermediate-sized basic keratins | |

| WT-1 tumor suppressor gene | |

| Podoplanin–transmembrane mucoprotein | |

| Thrombomodulin–surface glycoprotein involved in intravascular coagulation | |

| •Negative markers | |

| Claudin-4, TTF-1, PAX-8, CEA | |

| •Prognostic markers | |

| Nuclear grade, mitotic count, MIB-1/Ki-67 |

Peritoneal carcinomatosis can have an ovarian, fallopian tube (previously considered as primary peritoneal carcinomas), gastric, pancreatic, colonic, and more rarely, breast origin [101, 102]. Therefore, IHC panels have to be adjusted accordingly.

The markers that are ordered should be based on the histology findings. The other markers that are expressed by adenocarcinomas but not mesotheliomas are B72.3, MOC31, and BER-EP4 [103–105]. The markers that are expressed by PM are calretenin, D2-40, WT-1, and CK5/6. WT-1 is expressed in primary peritoneal serous carcinomas and ovarian serous carcinomas [106]. Of these, the Mullerian origin tumor show strong and diffuse positivity for PAX-8 which is seldom positive in PM. PPSCs can be positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Two positive and two negative markers are required to establish a diagnosis of mesothelioma.

Synoptic reporting including necrosis, grade, and mitotic count can also help with prognostication. Ki-67 has been shown to be a prognostic marker for outcomes for patients undergoing surgery and may be considered [107, 108].

-

I.

Staging

This staging system for peritoneal mesothelioma has not been formally standardized by the American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Yan et al. combined data on malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) patients from eight institutions in the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) to determine a clinic-pathologic staging system [109]. In this system, peritoneal cancer index (PCI) is grouped into T categories: T1 is PCI 1–10, T2 is PCI 11–20, T3 is PCI 21–30, and T4 is 30–39. If there is nodal disease, it is classified as N1. Systematic sampling of retroperitoneal nodes is often essential for nodal staging. Presence of distant organ metastases is classified as M1. Using these categories, a staging classification was described that correlated with outcomes. Stage I includes T1N0M0 disease and had an 87% 5-year survival rate in this study. Stage II includes T2-3N0M0 tumors and had a 53% 5-year survival. Stage III included patients with T4 tumors or evidence of nodal or distant metastasis, which had a 5-year survival 29%. [109]

-

J.

Rare variants of mesothelioma

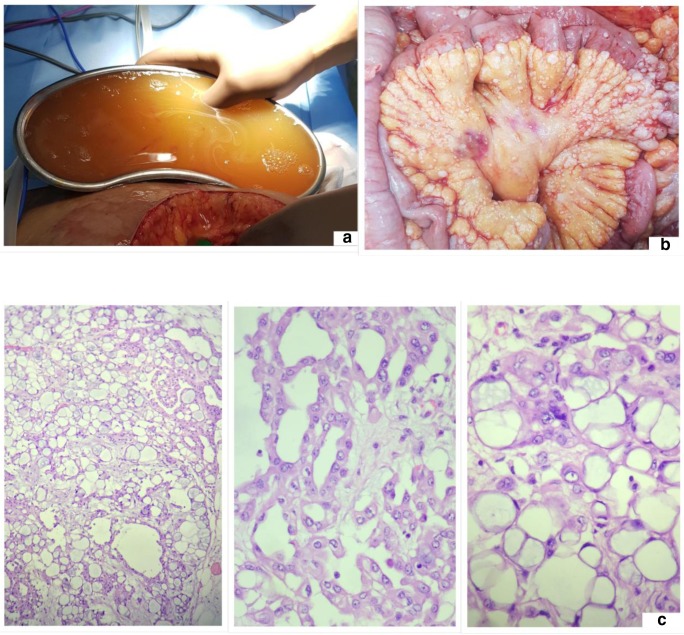

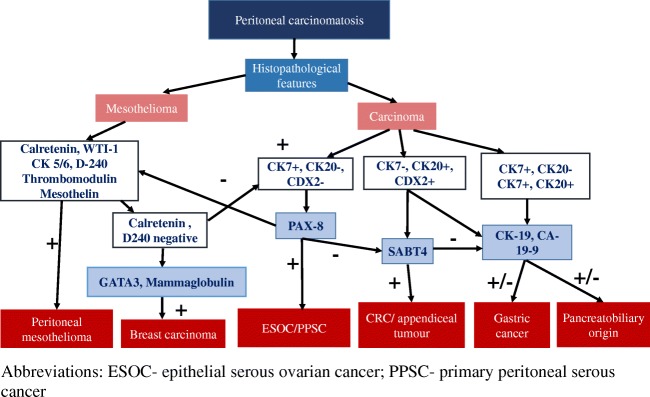

The presence of intracytoplasmic mucin in some of these tumors may be confused with signet ring cells and be misdiagnosed as a signet ring cell carcinoma [110]. Claudin 4 can distinguish between a carcinoma and mesothelioma in which it is not expressed [111]. Figure 16 shows the presentation of mucinous ascites in a patient that was confused with PMP. On histology, mesothelial cells with intracytoplasmic mucin were seen. Immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of a mesothelioma. Figure 17 provides a schema for selecting immunohistochemistry markers to determine the site of origin of the primary. This sequence is not binding and the selection of markers should be done keeping in mind the clinical picture and histological findings. For example, mesothelial markers can be excluded for a patient with a mucinous ovarian tumor with peritoneal metastases.

Fig. 16.

Presentation of a mucinous ascites (a) with peritoneal deposits (b) and histology showing mesothelial cells with apical mucin (c)

Fig. 17.

Immunohistochemistry markers for determining the primary tumor site in a patient with peritoneal metastases. ESOC epithelial serous ovarian cancer, PPSC primary peritoneal serous cancer

Other Peritoneal Tumors

-

A.

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a malignant tumor that arises from the peritoneal surfaces of the abdomen and pelvis and typically affects men aged 5–25 years. The most common presentation is of a pelvic mass with other smaller deposits over the peritoneum and ascites [112]. It has a propensity for lymph nodal and distant metastases to the liver and lungs. It has been linked to a specific translocation, t (11; 22) (p13; q12), that is seen in almost all cases, juxtaposing the Ewing sarcoma (EWS) gene to the Wilms tumor (WT)-WT1 tumor suppressor gene [113–115]. The cytogenetic analysis is essential for diagnosis along with a histopathological assessment. The tumor usually forms a large intra-abdominal mass consisting of nests or strands of small round cells embedded in a dense desmoplastic stroma. The cells show polyphenotypic differentiation, typically a mixture of epithelial, mesenchymal, and neural features. The immune-histochemical profile of DSRCT shows reactivity for epithelial (keratin, epithelial membrane antigen), mesenchymal (vimentin), neural (neuron-specific enolase and CD56), and myogenic (desmin) markers.

This diagnosis should be kept in mind when looking at peritoneal metastases in young male patients.

-

B.

Diffuse peritoneal leiomyomatosis

Diffuse peritoneal leiomyomatosis (DPL) is a benign disease with malignant potential. It is characterized by the proliferation of multiple benign nodules comprising of smooth muscle cells in the peritoneal cavity [116]. It is hypothesized that it arises from the proliferation of smooth muscle cells in the subperitoneum in response to a hormonal stimulus. In most instances, increased exposure to endogenous or exogenous estrogens is the underlying cause. There have been reports of DPL developing after morcellation of a uterine leiomyoma. On histology, the peritoneal nodules are composed of spindle cells that are bland and have few or no mitosis [117]. The mitotic index is less than 3/10 HPF. High-grade features are absent. The nodules may contain fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, decidual cells, and, sporadically, endometrial stromal cells in addition to smooth muscle cells. Evaluation of the ER and PR receptor status should be performed in all patients. Differential diagnoses for multiple peritoneal nodules include peritoneal carcinomatosis, peritoneal leiomyosarcomatosis, mesothelioma, tuberculosis, and lymphoma [116, 117].

This condition needs to be distinguished from a benign metastasizing leiomyoma which is characterized by fewer nodules and often presents with metastases in the lungs [118].

Patients with DPL without exogenous or endogenous estrogen exposure, without uterine leiomyomas, and without ER and PR expression on the tumor nodules are considered to be at high risk of developing malignancy. Often the malignant change develops within months or a year of diagnosis of DPL [118]. In some cases, a low-grade leiomyosarcoma may be misdiagnosed as DPL or is already present in one of the nodules that was not biopsied.

-

C.

Other tumors

Neuroendocrine tumor, gastrointestinal stroma tumors, endometrial adenocarcinomas, serous carcinomas and uterine leimyosarcomas are some of the other tumors that present with peritoneal metastases.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 27 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Frederic Bibeau for his comments and suggestions on this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Passot G, Vaudoyer D, Villeneuve L, et al. What made hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy an effective curative treatment for peritoneal surface malignancy: a 25-year experience with 1,125 procedures. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113:796–803. doi: 10.1002/jso.24248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine EA, Stewart JH, Shen P, Russell GB, Loggie BL, Votanopoulos KI. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy: experience with 1,000 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(4):573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt Aditi, Mehta Sanket S., Zaveri Shabber, Rajan Firoz, Ray Mukurdipi, Sethna Kayomarz, Katdare Ninad, Patel Mahesh D., Kammar Praveen, Prabhu Robin, Sinukumar Snita, Mishra Suniti, Rangarajan Bharath, Rangole Ashvin, Damodaran Dileep, Penumadu Prasanth, Ganesh Mandakulutur, Peedicayil Abraham, Raj Hemant, Seshadri Ramakrishnan. Treading the beaten path with old and new obstacles: a report from the Indian HIPEC registry. International Journal of Hyperthermia. 2018;35(1):361–369. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2018.1503345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugarbaker PH. Peritonectomy procedures. Ann Surg. 1995;221(1):29–42. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199501000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumeister VM, Anagnostou V, Siddiqui S, et al. Quantitative assessment of effect of preanalytic cold ischemic time on protein expression in breast cancer tissues. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1815–1824. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portier BP, Wang Z, Downs-Kelly E, et al. Delay to formalin fixation ‘cold ischemia time’: effect on ERBB2 detection by in-situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engel KB, Moore HM. Effects of pre-analytical variables on the detection of proteins by immunohistochemistry in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:537–543. doi: 10.5858/2010-0702-RAIR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arber DA. Effect of prolonged formalin fixation on the immunohistochemical reactivity of breast markers. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2002;10:183–186. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200206000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babic A, Loftin IR, Stanislaw S, et al. The impact of pre-analytical processing on staining quality for H&E, dual hapten, dual color in situ hybridization and fluorescent in situ hybridization assays. Methods. 2010;52:287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chafin D, Theiss A, Roberts E, et al. Rapid two-temperature formalin fixation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr KM, Bubendorf L, Edelman MJ, et al. Second ESMO consensus conference on lung cancer: pathology and molecular biomarkers for non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1681–1690. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCluggage WG, Judge MJ, Clarke BA, Davidson B, Gilks CB, Hollema H, Ledermann JA, Matias-Guiu X, Mikami Y, Stewart CJ, Vang R, Hirschowitz L. International collaboration on cancer reporting. Data set for reporting of ovary, fallopian tube and primary peritoneal carcinoma: recommendations from the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting (ICCR) Mod Pathol. 2015;28(8):1101–1122. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doig T, Monaghan H. Sampling the omentum in ovarian neoplasia: when one block is enough. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:36–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Usubütün A, Ozseker HS, Himmetoglu C, et al. Omentectomy for gynecologic cancer: how much sampling is adequate for microscopic examination? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1578–1581. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-1578-OFGCHM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotte E, Peyrat P, Piaton E, Chapuis F, Rivoire M, Glehen O, Arvieux C, Mabrut JY, Chipponi J, Gilly FN, EVOCAPE group Lack of prognostic significance of conventional peritoneal cytology in colorectal and gastric cancers: results of EVOCAPE 2 multicentre prospective study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39(7):707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes N, Wayman J, Wadehra V, et al. Peritoneal cytology in the surgical evaluation of gastric carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:520–524. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pande R, Sunga A, Levea C, Wilding GE, Bshara W, Reid M, Fakih MG. Significance of signet-ring cells in patients with colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:50–55. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solass W, Sempoux C, Carr NJ, Detlefsen S, Bibeau F. Peritoneal sampling and histological assessment of therapeutic response in peritoneal metastasis: proposal of the Peritoneal Regression Grading Score (PRGS) Pleura Perit. 2016;1:99–107. doi: 10.1515/pp-2016-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bibeau F, Gil H, Castan F, et al. Comment on “Histopathologic evaluation of liver metastases from colorectal cancer in patients treated with FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab”. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:3127–3129. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang HHL, Leeper WR, Chan G, Quan D, Driman DK. Infarct-like necrosis: a distinct form of necrosis seen in colorectal carcinoma liver metastases treated with perioperative chemotherapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:570–576. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824057e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker K, Mueller JD, Schulmacher C, Ott K, Fink U, Busch R, et al. Histomorphology and grading of regression in gastric carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2003;98:1521–1530. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chirieac LR, Swisher SG, Correa AM, et al. Signet-ring cell or mucinous histology after preoperative chemoradiation and survival in patients with esophageal or esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2229–2236. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shia J, McManus M, Guillem JG, et al. Significance of acellular mucin pools in rectal carcinoma after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:127–134. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318200cf78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim S-B, Hong S-M, Yu CS, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of acellular mucin in locally advanced rectal cancer patients showing pathologic complete response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:47–52. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182657186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Passot G, You B, Boschetti G, Fontaine J, Isaac S, Decullier E, Maurice C, Vaudoyer D, Gilly FN, Cotte E, Glehen O. Pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a new prognosis tool for the curative management of peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(8):2608–2614. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3647-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubbia-Brandt L, et al. Importance of histological tumor response assessment in predicting the outcome in patients with colorectal liver metastases treated with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by liver surgery. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(2):299–304. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blazer DG, 3rd, et al. Pathologic response to preoperative chemotherapy: a new outcome end point after resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5344–5351. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yonemura Y, Canbay E, Ishibashi H. Prognostic factors of peritoneal metastases from colorectal cancer following cytoreductive surgery and perioperative chemotherapy. Sci World J. 2013;2013:978394. doi: 10.1155/2013/978394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]