Abstract

Introduction.

Survival in elderly patients undergoing mastectomy or lumpectomy has not been specifically analyzed.

Methods.

Patients older than 70 years of age with clinical stage I invasive breast cancer, undergoing mastectomy or lumpectomy with or without radiation, and surveyed within 3 years of their diagnosis, were identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results and medicare health outcomes survey-linked dataset. The primary endpoint was breast cancer-specific survival (CSS).

Results.

Of 1784 patients, 596 (33.4 %) underwent mastectomy, 918 (51.4 %) underwent lumpectomy with radiation, and 270 (15.1 %) underwent lumpectomy alone. Significant differences were noted in age, tumor size, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, lymph node status (all p<0.0001) and number of positive lymph nodes between the three groups (p = 0.003). On univariate analysis, CSS for patients undergoing lumpectomy with radiation [hazard ratio (HR) 0.61, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.43–0.85; p = 0.004] was superior to mastectomy. Older age (HR 1.3, 95 % CI 1.09–1.45; p = 0.002), two or more comorbidities (HR 1.57, 95 % CI 1.08–2.26; p = 0.02), inability to perform more than two activities of daily living (HR 1.61, 95 % CI 1.06–2.44; p = 0.03), larger tumor size (HR 2.36, 95 % CI 1.85–3.02; p<0.0001), and positive lymph nodes (HR 2.83, 95 % CI 1.98–4.04; p<0.0001) were associated with worse CSS. On multivariate analysis, larger tumor size (HR 1.89, 95 % CI 1.37–2.57; p<0.0001) and positive lymph node status (HR 1.99, 95 % CI 1.36–2.9; p = 0.0004) independently predicted worse survival.

Conclusions.

Elderly patients with early-stage invasive breast cancer undergoing breast conservation have better CSS than those undergoing mastectomy. After adjusting for comorbidities and functional status, survival is dependent on tumor-specific variables. Determination of lymph node status remains important in staging elderly breast cancer patients.

Breast cancer disproportionately affects older women, with the highest age-specific probability of developing invasive disease in women over 70 years of age.1 Prospective randomized controlled trials (RCT) have demonstrated similar survival rates between patients undergoing breast-conservation treatment (BCT) and those undergoing a mastectomy,2–4 which has led to an increase in the rates of BCT over the last few decades.5–7 More recent studies have shown improved survival of women undergoing BCT versus those undergoing mastectomy;7–9 however, many of these studies largely excluded elderly women. Therefore, the evidence to guide treatment in elderly patients is scarce.10 An increasing incidence of comorbidities, shorter duration of life expectancy, and less aggressive biological behavior of breast cancer in elderly patients have frequently been cited as reasons for undertreatment.11–14 However, others have shown that despite tumor characteristics being similar to that in younger women, age-adjusted breast cancer-specific mortality is higher in elderly patients, potentially indicating a biologically more aggressive behavior.15–17

Using a large contemporary population-based dataset, the primary aim of the current study was to evaluate the outcomes of elderly women undergoing mastectomy and BCT for invasive breast cancer, and the effect of comorbidities and functional impairment on these outcomes. The secondary aim of the study was to assess the role of evaluating nodal status.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective cohort study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare Health Outcomes Survey (SEER–MHOS) linked dataset from 1998 to 2009.18 The SEER program collects information on newly diagnosed cancer cases within SEER geographic regions, including 26 % of the US population, while the MHOS dataset contains patient demographics, socioeconomic data, and self-reported chronic health conditions. The SEER–MHOS includes participants from multiple MHOS cohorts selected every year from a random sample of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries in managed care plans who are administered a baseline survey followed by another survey 2 years later. Since Medicare Advantage plans are not represented in all SEER regions, the SEER– MOHS dataset does not include all registries that participate in the SEER.19 Nevertheless, the overlapping SEER regions account for approximately 1.5 million Medicare health plan enrollees annually and reflect areas that are racially and ethnically diverse.18 Given the advanced age of the patient cohort, and to exclude competing causes of death, breast cancer-specific survival (CSS) was deemed as the primary endpoint. Breast CSS of patients was calculated from the date of death, last date known to be alive, or follow-up cut-off date (30 November 2014). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this study.

Inclusion Criteria

Using the SEER–MHOS dataset from 1998 to 2009, we identified all female breast cancer patients over 70 years of age with clinical stage I (pathological stages I or II) invasive breast cancer, including invasive ductal and invasive lobular carcinoma, who underwent mastectomy or lumpectomy with or without radiation, and who were surveyed within 3 years of their diagnosis. Cancer stage was defined using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 6th edition definition for stages I and II.20 Breast cancer was defined using the World Health Organization (WHO) site code 26000, and International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition (ICD-0–3) histology codes 8500, 8520, and 8522.21,22

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with the following criteria were excluded from the study: prior cancer diagnosis; missing or unknown procedure type or follow-up; disabled or institutionalized patients; cancer reported at autopsy; non-infiltrating ductal or lobular carcinoma pathological subtypes; or death within 6 months of completing the survey. Breast cancer patients with missing or unknown procedure type or who did not undergo surgery were also excluded. Patients who underwent mastectomy with radiation were excluded as these patients tended to have more advanced disease (node positivity and larger tumor size).

Study Variables and Definitions

Patient demographics, socioeconomic data, tumor characteristics, and quality-of-life data collected from the SEER–MHOS dataset included age, education, income, marital status and home ownership; tumor size, lymph node status, stage, receptor status, and type of surgery; number of comorbidities based on totaling the responses to self-reported comorbidity questions in the MHOS, and activities of daily living (ADL). ADLs included eating, bathing, dressing and undressing, grooming, walking, getting in and out of bed, and the ability to control bowel function, as initially defined and standardized by Katz.23

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and tumor characteristics were summarized overall and by treatment type (lumpectomy, lumpectomy with radiation, and mastectomy). Differences in means and frequencies were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and Chisquare and Fisher’s exact tests for nominal variables. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and compared using log-rank tests. To account for potential bias, time from diagnosis to death less than 30 days was recorded as 0.1 months. To assess the effect of global health on survival outcomes in elderly women, and to determine whether other confounders besides breast cancer were responsible for the observed outcomes, we compared overall survival (OS) and CSS of the cohort with expected survival in age-matched controls. Expected survival rates were calculated using the female population from the 2010 United States Life Table.24 Univariate logistic regression was used to predict factors associated with breast cancer-specific death. Clinically meaningful determinants and those with p values<0.10 were included in a multivariate model. The model excluded variables that were missing more than 10 % of the data. Given that multiple non-cancer-related causes account for mortality in the elderly patient population, both OS and CSS were reported.

All analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and a 0.05 significance level was used throughout the analysis.

RESULTS

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

Overall, 1784 patients met the inclusion criteria, of whom 596 (33.4 %) underwent mastectomy, 918 (51.4 %) underwent lumpectomy with radiation, and 270 (15.1 %) underwent lumpectomy alone. Significant differences were noted in age, tumor size, AJCC stage, lymph node status, and number of positive lymph nodes between the three groups (Table 1). In comparison to lumpectomy with and without radiation, women undergoing mastectomy were noted to have a higher proportion of infiltrating lobular cancers (14.9 vs. 9.3 % and 7.0 %), stage II disease (44.3 vs. 24.6 % and 28.1 %), larger tumors (mean size 20.9 vs. 14.0 mm and 16.35 mm), and lymph node positivity (23.4 vs. 15.3 % and 19.5 %). No differences were noted in race, comorbidities, ADLs, or time elapsed from cancer diagnosis to the first survey. Most patients (n = 1369, 76.74 %) were estrogen receptor-positive, however data regarding receptor status were missing in 174 (10 %) patients.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of patients, stratified by treatment type

| Variable | Overall (N = 1784) |

Mastectomy without radiation (n = 596) |

Lumpectomy with radiation (n = 918) |

Lumpectomy without radiation (n = 270) |

p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | ||

| Age, years | 76.88 | 5.51 | 77.76 | 5.63 | 75.69 | 4.87 | 78.99 | 6.29 | <.0001 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 1381 | 77.41 | 452 | 75.84 | 710 | 77.34 | 219 | 81.11 | 0.4378 |

| Black | 129 | 7.23 | 50 | 8.39 | 63 | 6.86 | 16 | 5.93 | |

| Other | 274 | 15.36 | 94 | 15.77 | 145 | 15.8 | 35 | 12.96 | |

| Two or more comorbiditiesa | 344 | 19.28 | 130 | 21.81 | 157 | 17.1 | 57 | 21.11 | 0.0541 |

| Total ADLs >2 | 257 | 14.41 | 85 | 14.26 | 124 | 13.51 | 48 | 17.78 | 0.2122 |

| Type of breast cancer | |||||||||

| Infiltrating ductal carcinoma | 1462 | 81.95 | 460 | 77.18 | 764 | 83.22 | 238 | 88.15 | 0.0004 |

| Infiltrating lobular carcinoma | 193 | 10.82 | 89 | 14.93 | 85 | 9.26 | 19 | 7.04 | |

| Infiltrating ductal and lobular carcinoma | 129 | 7.23 | 47 | 7.89 | 69 | 7.52 | 13 | 4.81 | |

| Adjusted AJCC 6th stage (1988+) | |||||||||

| I | 1218 | 68.27 | 332 | 55.7 | 692 | 75.38 | 194 | 71.85 | <.0001 |

| IIA | 404 | 22.65 | 168 | 28.19 | 180 | 19.61 | 56 | 20.74 | |

| IIB | 162 | 9.08 | 96 | 16.11 | 46 | 5.01 | 20 | 7.41 | |

| SEER stage (missing = 41) | |||||||||

| Localized | 1461 | 81.89 | 446 | 74.83 | 787 | 85.73 | 228 | 84.44 | <.0001 |

| Regional | 323 | 18.11 | 150 | 25.17 | 131 | 14.27 | 42 | 15.56 | |

| Tumor size (mm) (missing = 32) | 16.68 | 12.19 | 20.97 | 15.43 | 14.01 | 8.62 | 16.35 | 11.85 | <.0001 |

| Lymph node positive (missing = 194) | 298 | 18.74 | 134 | 23.43 | 126 | 15.31 | 38 | 19.49 | 0.0006 |

| Number of positive lymph node(s) | 1.42 | 0.70 | 1.54 | 0.74 | 1.37 | 0.69 | 1.13 | 0.41 | 0.0029 |

| # No of months from first cancer to survey in SEER | 0.13 | 19.8 | −0.28 | 19.71 | −0.06 | 19.73 | 1.69 | 20.24 | 0.3673 |

| Alive 12 months from the survey | 1747 | 97.93 | 584 | 97.99 | 904 | 98.47 | 259 | 95.93 | 0.0352 |

Comorbidities included hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmia, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes

ADLs activities of daily living, AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer, SEER Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program

Survival Analyses

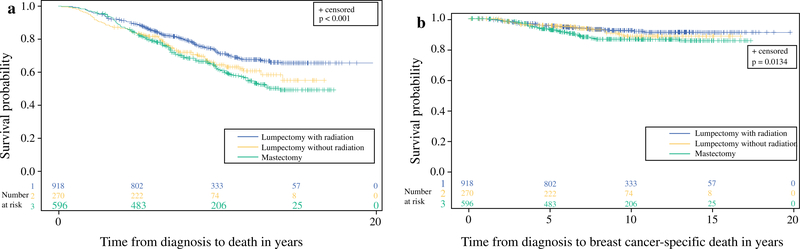

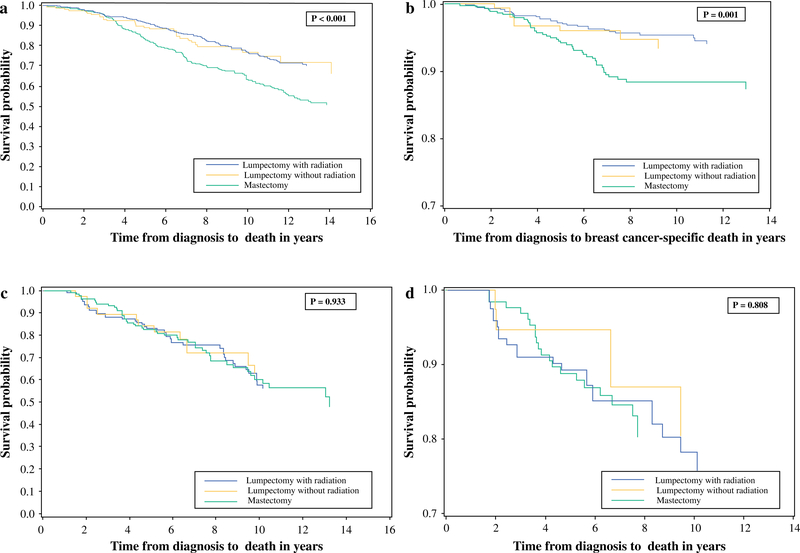

OS and CSS were reduced in women undergoing mastectomy compared with those who had lumpectomy with or without radiation (Fig. 1). This survival difference was also noted in the subgroup of women with node-negative disease (n = 1292; p ≤0.001), but not in node-positive patients (n = 298; p>0.8) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

a Overall and b breast cancer-specific survival based on treatment type

FIG. 2.

a, c Overall and b, d breast cancer-specific survival in node-negative and node-positive patients

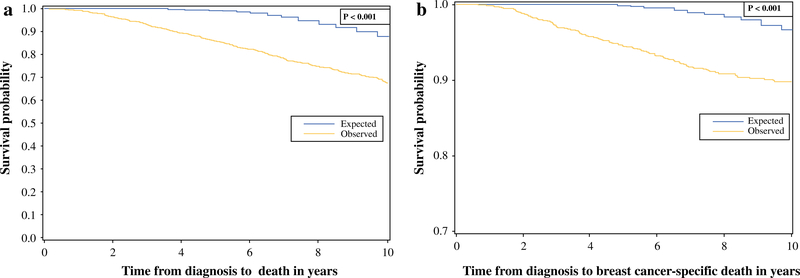

OS and CSS were significantly reduced in breast cancer patients compared with age-matched controls of elderly patients without breast cancer (p<0.001) [Fig. 3].

FIG. 3.

a Overall and b breast cancer-specific survival—observed versus expected (age-matched controls)

On univariate analysis, CSS for patients undergoing lumpectomy with radiation [hazard ratio (HR) 0.61, 95 % CI 0.43–0.85; p = 0.004] was superior to those undergoing mastectomy (Table 2). Older age (HR 1.3, 95 % CI 1.09–1.45; p = 0.002), two or more comorbidities (HR 1.57, 95 % CI 1.08–2.26; p = 0.02), inability to perform more than two ADLs (HR 1.61, 95 % CI 1.06–2.44; p = 0.03), larger tumor size (HR 2.36, 95 % CI 1.85–3.02; p<0.001), and positive lymph nodes (HR 2.83, 95 % CI 1.98–4.04; p<0.001) were associated with worse CSS.

TABLE 2.

Cox model for breast cancer-specific death

| Variable | Univariate model |

Multivariate model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | Lower 95 % CI | Upper 95 % CI | p value | HR | Lower 95 % CI | Upper 95 % CI | p value | |

| Age, per 5-year increase | 1.252 | 1.085 | 1.445 | 0.0021 | 1.151 | 0.975 | 1.359 | 0.0965 |

| Treatment type | ||||||||

| Lumpectomy with radiation | 0.607 | 0.432 | 0.854 | 0.0042 | 0.813 | 0.549 | 1.205 | 0.3036 |

| Lumpectomy without radiation | 0.695 | 0.422 | 1.146 | 0.1541 | 0.707 | 0.386 | 1.296 | 0.2623 |

| Mastectomy | Ref | |||||||

| Race | ||||||||

| Other | 0.608 | 0.355 | 1.04 | 0.0691 | 0.605 | 0.339 | 1.079 | 0.0886 |

| Black | 1.536 | 0.912 | 2.588 | 0.1069 | 0.707 | 0.386 | 1.296 | 0.2806 |

| White | Ref | |||||||

| Two or more comorbidities | 1.505 | 1.031 | 2.198 | 0.0341 | 1.324 | 0.875 | 2.002 | 0.1837 |

| Total ADLs >2 | 1.608 | 1.06 | 2.441 | 0.0255 | 1.345 | 0.841 | 2.15 | 0.2158 |

| Log tumor size, per 1 mm increase | 2.364 | 1.851 | 3.019 | <0.0001 | 1.877 | 1.373 | 2.567 | <0.0001 |

| Lymph node-positive | 2.828 | 1.98 | 4.039 | <0.0001 | 1.989 | 1.364 | 2.902 | 0.0004 |

| No. of months from first cancer to survey in SEER, per 12-month increase | 0.929 | 0.844 | 1.023 | 0.1344 | ||||

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, ADLs activities of daily living, SEER Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program

On multivariate analysis, only larger tumor size (HR 1.89, 95 % CI 1.37–2.57; p<0.001) and positive lymph node status (HR 1.99, 95 % CI 1.36–2.9; p<0.001) were independent predictors of worse survival (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to evaluate outcomes in elderly women with invasive breast cancer. We found that OS and CSS were improved in women undergoing BCT compared with those undergoing mastectomy. However, when adjusting for age, tumor size, lymph node status, race, comorbidities, and functional limitations (ADLs), we noted that the type of surgery was not an independent factor determining survival. Using multivariable analysis, only tumor-related factors (tumor size and lymph node status) were independently associated with OS and CSS.

Hwang et al. studied patients from the California Cancer Registry with a diagnosis of stage I or II breast cancer during the period from 1990 to 2004, and demonstrated a lower HR for death in patients undergoing BCT with radiation.7 These researchers concluded that the presence of comorbidities could have potentially influenced the choice of treatment and indirectly affected survival. Even within different subgroups of cause-specific mortality, BCT was associated with improved survival compared with mastectomy. The authors concluded that a greater proportion of non-fatal comorbidities may have influenced the decision to perform a mastectomy, but comorbidities per se are unlikely to explain improved survival with BCT; however, only one-quarter of patients in the study cohort were over 70 years of age. Additionally, functional disabilities that are known to occur in elderly patients.25 and may have potentially influenced surgical decision making, were not factored in. Our study is unique since it focuses on elderly women from across multiple regions in the US, and accounted for the effect of comorbidities and functional impairments on survival. Although no differences were noted in the comorbidities and functional limitations in the mastectomy and BCT groups, mastectomy patients had larger and more node-positive tumors than those undergoing breast-conserving surgery. Not surprisingly, survival was therefore worse for patients undergoing mastectomy. After adjusting for the type of surgery and other putative determinants of outcomes, including comorbidities and ADLs, we found that only tumor size and lymph node status were independent determinants of survival. This finding has important implications in the selection of surgical treatment for older breast cancer patients.

Agarwal et al. noted that improved breast CSS in patients undergoing BCT (with radiation), compared with those undergoing mastectomy,8 could have resulted from differences in the administration of adjuvant systemic therapies, as well as differences in tumor biology that are not explained by tumor size and lymph node status (lymphovascular invasion and extracapsular extension). Although age was an independent predictor of survival, no age-based subgroup analysis was performed to specifically analyze the effect of treatment type in elderly women. Additionally, comorbidities and performance status were not considered in their analyses.

Prospective studies with a mature follow-up have demonstrated equivalent outcomes with mastectomy or BCT; however, they largely excluded elderly women.2–4 Additionally, the proportion of women with comorbidities or functional impairments was not specifically reported. The CALGB-9343 study of older women undergoing BCT demonstrated that women enrolled in the study were, in general, healthier than those in the general population.26 In both the CALGB-9343 and PRIME II trials, only a small proportion of elderly women with early-stage breast cancer died of their disease.26,27 In contrast, in the present population-based dataset, both OS and CSS were worse for women with breast cancer compared with age-matched elderly women in the general population. Assuming that the incidence of comorbidities and functional impairments is similar in women with breast cancer and age-matched controls, this finding is important for two reasons. First, it indicates that even though comorbidities play an important role, breast cancer in elderly patients has an independent negative effect on survival. Second, it emphasizes that population-based analysis may potentially be more applicable to the general population than RCTs with strict patient selection criteria.

Multiple RCTs have shown that the addition of radiation treatment to lumpectomy, followed by endocrine therapy, in older, clinically node-negative women is not associated with improved OS or disease-free survival (DFS).26–29 Despite this, even for women meeting the criteria, the omission of postoperative radiation in selected older patients is not widely practiced.30,31 In the present study, OS and CSS among node-negative women undergoing lumpectomy with or without postoperative adjuvant radiation, was similar (Fig. 2). Acknowledging that details of adjuvant endocrine treatment were not captured in the study population, our study findings nonetheless affirm evidence-based guidelines from major societies that recommend the selective use of radiation in older women with hormone receptor-positive early breast cancers.32

The issue of nodal assessment in elderly patients with early-stage breast cancer has been debated in the literature. The International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 10–93, which compared women >60 years of age with clinically node-negative operable breast cancer who were randomly assigned to undergo surgery with axillary clearance + tamoxifen versus surgery + tamoxifen only, found no difference in OS or DFS with an improvement in early quality of life in the no-axillary-surgery arm.33 Similarly, data from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative overview of RCTs of adjuvant systemic therapy showed that endocrine therapy (specifically tamoxifen) provides the majority of the advantage associated with adjuvant treatments.34 As nodal status in clinically node-negative, hormone receptor-positive older women is potentially less relevant in determining the need for adjuvant systemic chemotherapy, axillary dissection or sentinel node biopsy could arguably be avoided in these women. In the present study, we noted significant differences in OS and diseasespecific survival in node-negative versus node-positive patients in the mastectomy group as well as the lumpectomy + radiation groups (data not shown), and also noted a significant proportion of hormone receptor-positive patients in both groups (74.2 and 79.6 %, respectively). We did not specifically analyze nodal status in relation to hormone receptor status since details of these data were missing in ≥10 % of patients and information regarding adjuvant anti-estrogen or systemic chemotherapy was not available. However, assuming that the administration of adjuvant hormone therapy was based on receptor status rather than nodal status, the difference in survival between node-positive and node-negative patients indicates that determination of nodal status might still be relevant in the treatment of older women with early-stage breast cancer.

Our study has several strengths. First, because the SEER is a population-based registry, outcomes reported could be extrapolated to patients in the general population, unlike outcomes reported in clinical trials with strictly controlled selection criteria. Second, we analyzed patient-level variables, such as comorbidities and ADLs, which are potentially important determinants of treatment choice and outcome, especially in the elderly population. Third, our study incorporated long-term follow-up of patients, thereby minimizing biases that could result from biologically more aggressive tumor types that could have recurred early and caused early mortality, or from excess burden of comorbidities that might have potentially shortened life expectancy.

Our study is subject to limitations of a retrospective dataset analysis. The SEER–MHOS is a linked dataset combining retrospective registry data from the SEER with a robust prospective patient survey. Detailed clinicopathological data frequently found in prospective RCTs are not readily available. Radiation data are frequently underreported, thereby potentially biasing outcomes.35 It is difficult to distinguish which patients solely underwent sentinel node biopsy versus a complete axillary dissection because the SEER only recently, starting in 2012, instituted newer guidelines, which instructed coders to utilize the operative report instead of the pathology report in determining the nature of axillary surgery performed. The dataset does not capture detailed pathologic information regarding lymphovascular invasion or extranodal extension, or details of adjuvant therapy, including the use of anti-estrogen, anti-HER2/neu, or chemotherapy. However, it is unlikely that these variables significantly biased the outcomes in our study since the decision to administer adjuvant therapy to women with breast cancer is based largely on the pathologic assessment of specific tumor-related characteristics, and not per se on whether these patients undergo BCT or mastectomy. In addition, other factors that may influence the decision to perform mastectomy versus BCT, such as access to healthcare centers, and provider and patient biases in choosing treatments, are not captured by the SEER registry.

CONCLUSIONS

Elderly patients with early-stage invasive breast cancer undergoing breast conservation with or without radiation have better CSS than those undergoing mastectomy. However, after adjusting for age, comorbidities, functional impairment, and type of surgery, survival is dependent on tumor-specific variables. Radiation treatment may be selectively avoided in elderly women with early-stage breast cancer after breast-conservation surgery. Assessment of lymph node status remains important in the staging of elderly breast cancer patients as it is a significant determinant of survival outcomes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by Wake Forest University Biostatistics shared resource NCI CCSG P30CA012197.

This work was presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology 69th Annual Cancer Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 2–5 March 2016.

Footnotes

ETHICS STATEMENT Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this study.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1245/s10434-016-5582-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST Harveshp D. Mogal, Clancy Clark, Rebecca Dodson, Nora F. Fino, and Marissa Howard-McNatt have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse S, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2012, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD, based on November 2014 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2015. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/sections.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese R, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichter AS, Lippman ME, Danforth DN Jr, d’Angelo T, Steinberg SM, deMoss E, et al. Mastectomy versus breast-conserving therapy in the treatment of stage I and II carcinoma of the breast: a randomized trial at the National Cancer Institute. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:976–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith GL, Xu Y, Shih YC, Giordano SH, Smith BD, Hunt KK, et al. Breast-conserving surgery in older patients with invasive breast cancer: current patterns of treatment across the United States. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:425–33.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee MC, Rogers K, Griffith K, Diehl KA, Breslin TM, Cimmino VM, et al. Determinants of breast conservation rates: reasons for mastectomy at a comprehensive cancer center. Breast J. 2009;15:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang ES, Lichtensztajn DY, Gomez SL, Fowble B, Clarke CA. Survival after lumpectomy and mastectomy for early stage invasive breast cancer: the effect of age and hormone receptor status. Cancer. 2013;119:1402–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agarwal S, Pappas L, Neumayer L, Kokeny K, Agarwal J. Effect of breast conservation therapy vs mastectomy on disease-specific survival for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofvind S, Holen Aas T, Roman M, Sebuodegard S, Akslen LA Women treated with breast conserving surgery do better than those with mastectomy independent of detection mode, prognostic and predictive tumor characteristics. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:2061–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Fioretta G, Laissue P, Neyroud-Caspar I, Schafer P, et al. Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3580–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Blagojevic S, Vlastos AT, Vlastos G. Older female cancer patients: importance, causes, and consequences of undertreatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1858–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diab SG, Elledge RM, Clark GM. Tumor characteristics and clinical outcome of elderly women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:550–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierga J-Y, Girre V, Laurence V, Asselain B, Diéras V, Jouve M, et al. Characteristics and outcome of 1755 operable breast cancers in women over 70 years of age. Breast. 2004;13:369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith BD, Jiang J, McLaughlin SS, Hurria A, Smith GL, Giordano SH, et al. Improvement in breast cancer outcomes over time: are older women missing out? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29: 4647–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schonberg MA, Marcantonio ER, Li D, Silliman RA, Ngo L, McCarthy EP. Breast cancer among the oldest old: tumor characteristics, treatment choices, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2038–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montroni I, Rocchi M, Santini D, Ceccarelli C, Ghignone F, Zattoni D, et al. Has breast cancer in the elderly remained the same over recent decades? A comparison of two groups of patients 70 years or older treated for breast cancer twenty years apart. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5:260–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ambs A, Warren JL, Bellizzi KM, Topor M, Haffer SC, Clauser SB. Overview of the SEER–Medicare Health Outcomes Survey linked dataset. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29:5–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent EE, Ambs A, Mitchell SA, Clauser SB, Smith AW, Hays RD. Health-related quality of life in older adult survivors of selected cancers: data from the SEER-MHOS linkage. Cancer. 2015;121:758–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greene FL, American Joint Committee on Cancer, American Cancer Society AJCC cancer staging manual. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fritz AG. International classification of diseases for oncology(ICD-O). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallace M, Shelkey M. Katz index of independence in activities of daily living (ADL). Urol Nurs. 2007;27:93–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arias E. United States life tables, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63:1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klepin H, Mohile S, Hurria A. Geriatric assessment in older patients with breast cancer. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2009;7:226–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Bellon JR, Cirrincione CT, Berry DA, McCormick B, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 years or older with early breast cancer: long-term follow-up of CALGB 9343. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2382–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunkler IH, Williams LJ, Jack WJL, Cameron DA, Dixon JM. Breast-conserving surgery with or without irradiation in women aged 65 years or older with early breast cancer (PRIME II): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:266–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fyles AW, Mccready DR, Manchul LA, Trudeau ME, Merante P,Pintilie M, et al. Tamoxifen with or without breast irradiation in women 50 years of age or older with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:963–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potter R, Gnant M, Kwasny W, Tausch C, Handl-Zeller L,Pakisch B, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen or anastrozole with or without whole breast irradiation in women with favorable early breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soulos PR, Yu JB, Roberts KB, Raldow AC, Herrin J, Long JB, et al. Assessing the impact of a cooperative group trial on breast cancer care in the medicare population. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1601–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCormick B, Ottesen RA, Hughes ME, Javid SH, Khan SA,Mortimer J, et al. Impact of guideline changes on use or omission of radiation in the elderly with early breast cancer: practice patterns at National Comprehensive Cancer Network institutions. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), Breast Cancer. Version 1.2014. www.NCCN.com (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudenstam C-M, Zahrieh D, Forbes JF, Crivellari D, Holmberg SB, Rey P, et al. Randomized trial comparing axillary clearance versus no axillary clearance in older patients with breast cancer: first results of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 10–93. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jagsi R, Abrahamse P, Hawley ST, Graff JJ, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. Under ascertainment of radiotherapy receipt in surveillance, epidemiology, and end results registry data. Cancer. 2012; 118:333–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.