Abstract

Objective

To describe unusual course and unusual phenotypic features in an adult patient with Kearns–Sayre syndrome (KSS). Case Report. The patient is a 49-year-old male with KSS, diagnosed clinically upon the core features, namely, onset before the age 20 of years, pigmentary retinopathy, and ophthalmoparesis, and the complementary features, namely, elevated CSF protein, cardiac conduction defects, and cerebellar ataxia. The patient presented also with other previously described features, such as diabetes, short stature, white matter lesions, hypoacusis, migraine, hepatopathy, steatosis hepatis, hypocorticism (hyponatremia), and cataract. Unusual features the patient presented with were congenital anisocoria, severe caries, liver cysts, pituitary enlargement, desquamation of hands and feet, bone chondroma, aortic ectasia, dermoidal cyst, and sinusoidal polyposis. The course was untypical since most of the core phenotypic features developed not earlier than in adulthood.

Conclusions

KSS is a multisystem disease, but the number of tissues affected is higher than so far anticipated. KSS should be considered even if core features develop not earlier than in adulthood and if unusual features accompany the presentation.

1. Introduction

Kearns–Sayre syndrome (KSS) is a mitochondrial disorder (MID) most frequently due to a single mtDNA deletion and rarely due to mtDNA point mutations [1, 2]. The diagnosis is established clinically if the three core features onset, <20 years of age, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO), and pigmentary retinopathy, and at least one of the following features are present: cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein >100 mg/dl, cardiac conduction defects, or cerebellar dysfunction [1]. Here, we present an adult male with KSS with unusual phenotypic features and disease trajectory.

2. Case Report

The patient is a 49-year-old male, with height 161 cm, weight 85 kg, and a history of preterm birth at gestational week 34 from nonconsanguineous parents, congenital anisocoria, developmental delay, hypoacusis, and tetra-ataxia (Table 1). During childhood general downslowing, chronic fatigue, and sicca syndrome of the eyes occurred. He repeatedly experienced respiratory infections and oral herpetic infections and once painless desquamation of the hands and foot soles (Table 1). He was successfully trained and worked as a hairdresser until the age of 38 years in his parent's hair saloon and retired at the age of 40 years.

Table 1.

Disease trajectory of the presented patient over 49 years of age.

| Onset (age) | Manifestation | Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Intrauterine | Premature birth (7 weeks earlier) | None |

| Birth | Congenital anisocoria | None |

| Infancy | Developmental delay | None |

| Infancy | Hypoacusis | Hearing devices since age 39 |

| Childhood | Downslowing, chronic fatigue | None |

| Childhood | Sicca syndrome + recurrent conjunctivitis | Eye drops |

| Childhood | Recurrent respiratory infections | Antibiotics |

| Childhood | Recurrent herpetic infections, stomatitis | Virostatics |

| 5 y | Painless desquamation of hands and feet | None |

| 6 y | Ophthalmoparesis (first recognised) | None |

| 7 y | Tetra-ataxia | None |

| 18 y | Severe caries | Full prosthesis |

| 27 y | Right-sided inguinal hernia | Bassini surgery |

| 29 y | Sacral dermoidal cyst | Surgery |

| 30 y | Bifascicular block∗ | None |

| 30 y | Erythema nodosa of feet | Steroids |

| 35 y | Hyper-CKemia | None |

| 35 y | Hyperuricemia | Diet |

| 35 y | Hyponatremia, hypokalemia | NaCl, KCl |

| 36 y | Somnolence, infection, suspected BE, SLE | Antibiotics, virostatics, endobolin, steroids |

| 36 y | Suspected SLE | None |

| 36 y | Elevated CSF protein | None |

| 36 y | Dysarthria | None |

| 36 y | Polyposis of nasal sinuses | None |

| 36 y | Gait disturbance, falls | None |

| 36 y | Neuropsychological deficits | Training |

| 37 y | Arterial hypertension | Antihypertensives |

| 37 y | Hepatopathy | None |

| 37 y | Liver cysts | None |

| 37 y | Rhabdomyolysis (CK: 2673 U/L) | None |

| 38 y | Chondroma/fibroma of the right femur | None |

| 38 y | Steatosis hepatis | None |

| 44 y | Suspected SLE, Na↓, K↓, migraine | Analgesics |

| 45 y | Fall, rib fracture, pneumothorax | Drainage |

| 45 y | Diabetes | Antidiabetics |

| 47 y | Cataract bilaterally | Surgery |

| 49 y | Aortic ectasia | None |

∗Left anterior hemiblock plus right bundle branch block, SLE: stroke-like episode, nr: not relevant, CSF: cerebrospinal fluid, BE: Bickerstaff encephalitis.

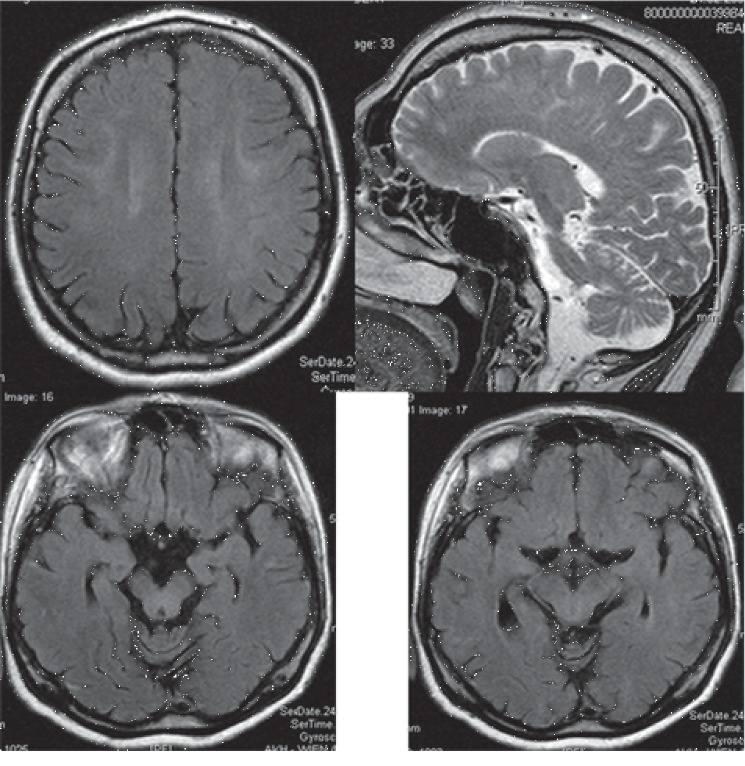

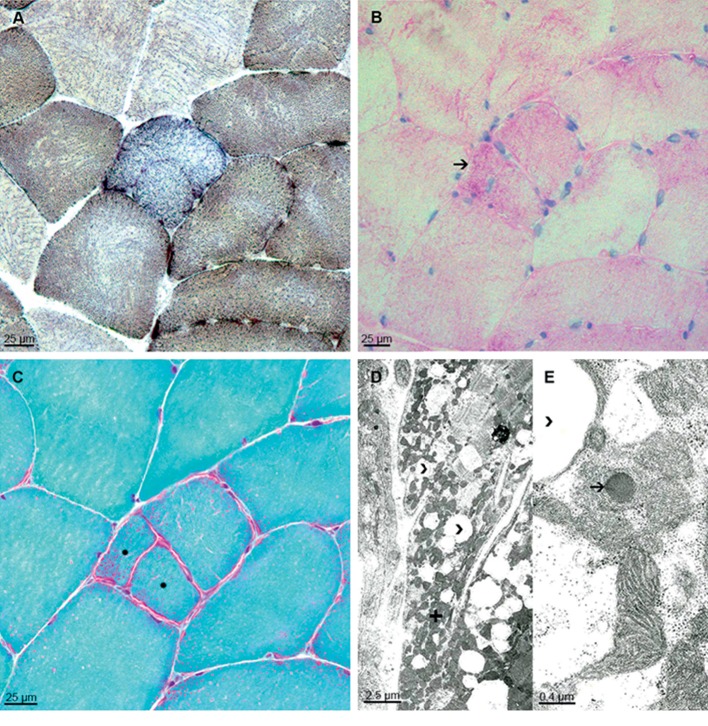

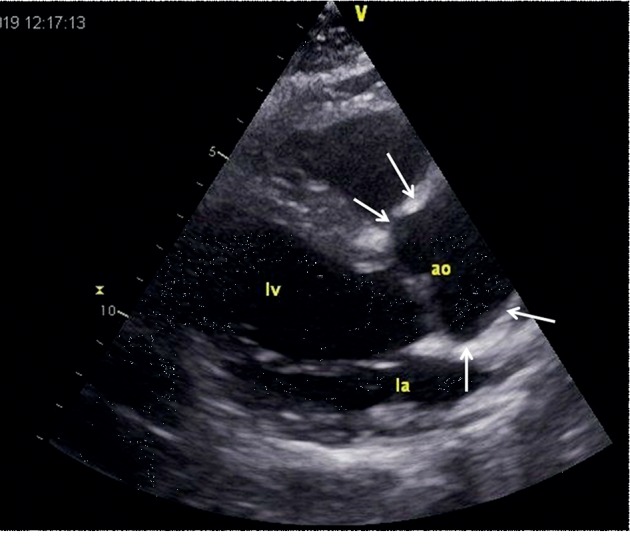

At age of 30 years, left anterior hemiblock and right bundle-branch-block were recorded. Since age 35, recurrent mild elevation of creatine-kinase (CK) was noted. Aldolase and myoglobin were also elevated. Since age 35, recurrent electrolyte disturbances (hypokalemia and hyponatremia) and hyperuricemia developed. At age 36, he experienced a first episode of disorientation, impaired cognition, bradyphrenia, and secessus urinae. Clinical exam revealed bilateral ophthalmoparesis and dysarthria. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed subcortical hyperintensities in a nonvascular distribution, which were hyperintens on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) (Figure 1). Neuropsychological testing revealed attention deficits, disability of encoding visual contents, adjustment disorder, and depression. The patient was diagnosed with suspected Bickerstaff encephalitis and questionable seizures. Following these episodes, his gait became disturbed with occasional falls due to increased ataxia. At age 37, he experienced an untriggered rhabdomyolysis. Muscle biopsy from the deltoid muscle suggested muscular dystrophy as only fat but no muscle tissue was detected (Table 2). At age 38, he underwent a second muscle biopsy from the left lateral vastus muscle which showed cytochrome-C-oxidase (COX)-negative fibers (Figure 2(a)), glycogen depositions (Figure 2(b)), fiber splitting, and ragged-red fibers (Figure 2(c)). Electron microscopy showed abnormally shaped and structured mitochondria, megaconia, abnormal glycogen and lipid depositions, and dark bodies (Figures 2(d) and 2(e)). At age 44, migraine developed. At age 47, he underwent cataract surgery bilaterally (Table 1). At age 49, diabetes was diagnosed. Transthoracic echocardiography was normal except for mild enlargement of the ascending aorta (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Cerebral MRI at age 36 showing mild, band-like T2-hyperintensities in the white matter bilaterally (upper left) and the midbrain (lower panels) and mild cerebellar atrophy (upper right).

Table 2.

Crucial investigations carried out during the disease trajectory.

| Date/age | Investigation | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 2000, 30 years | Echocardiography | “Pulmonary insufficiency” |

| 1.1.06 | Lumbar puncture | Protein 167 mg/dl, otherwise normal |

| 3.1.06 | EEG | Normal |

| 3.1.06 | Lumbar puncture | Protein 107 mg/dl, otherwise normal |

| 5.1.06, 35 years | Nerve conduction studies | Normal |

| 4.1.06, 36 years | Cerebral MRI | T2-hyperintensities, subcortical, mesencephalon, DWI, ADC hyperintense enlarged pituitary gland, sinusoidal polyposis |

| 12.1.06 | Neuropsychological testing | Attention deficit, disability of encoding visual contents, adjustment disorder, and depression |

| 13.1.06 | Cerebral MRI | Unchanged to previously |

| 17.1.06 | Lumbar puncture | Protein 152 mg/dl, otherwise normal |

| 1/2006 | Ophthalmologic investigation | Strabism, fundus tabulates, AM atrophy, papillary excavation |

| 24.2.06 | Cerebral MRI | Band-like T2-, DWI-, ADC-hyperintensities in the ML and mesencephalon bilaterally |

| 2.1.06 | Abdominal ultrasound | Normal |

| 1/06 | Lumbar puncture | Protein 167 mg/dl |

| 16.12.06 | Ophthalmologic investigation | Pigmentary epithelium shifts, retinal dystrophy, rod/cone degeneration (RP suspected) |

| 8/07 | Muscle biopsy (deltoid) | Fat, no muscle |

| 12.9.07 | CK | 2673 U/L (rhabdomyolysis) |

| 10.8.07 | Myoglobin | 152 ng/ml (n, 19–92 ng/ml) |

| 2.8.07 | X-ray of the lungs | Normal width of aorta |

| 6.8.07 | Echocardiography | Normal |

| 8.8.07 | Liver enzymes | Elevated |

| 9.8.07 | Abdominal CT | Multiple liver cysts |

| 13.8.07 | Muscle biopsy | No muscle tissue, only fat |

| 13.2.08 | Muscle MRI | Chondroma right femur |

| 19.2.08, 38 years | Muscle biopsy (left lateral vastus) | Indicates mitochondrial myopathy |

| 15.12.08 | Cerebral MRI | Cerebellar atrophy |

| 19.12.08 | Needle electromyography | Increased polyphasia exclusively |

WMLs: white matter lesions, RP: retinitis pigmentosa.

Figure 2.

(a–c) Neuropathology of muscle biopsy (left vastus lateralis muscle) presents myopathic changes with single COX-negative fibers (a) COX/SDH double-labeling, mildly increased PAS-positivity in few fibers (b) arrow, muscle fiber splitting, and ragged-red fibers (c) Gomori-trichrome stain, asterisk. (d and e) Electron microscopy images illustrate increased numbers of fat vacuoles (d and e, arrow heads) between densly packed subsarcolemmal mitochondria (d) plus. Some mitochondria show single dark bodies in higher magnification (e) arrow.

Figure 3.

Echocardiographic parasternal long axis view showing the ectatic ascending aorta, measuring 37 mm in diameter.

The family history was positive for hypotonia (mother), diabetes (father, brother of father, grandmother from the father's side, grand-grandfather from the father's side), carcinoma (father), and stroke (father). Neurological exam at age 49, revealed short stature, microcephaly, facial dysmorphism, myopathic face, ophthalmoparesis, pupils nonreactive to light, anisocoria (left: 5 mm, right: 3 mm, unrounded), divergence of bulbs, ophthalmoparesis (abduction right bulb 60° abduction left bulb: 15° vertical movements impossible), bilateral ptosis (right > left), reduced corneal reflexes, hypoacusis requiring bilateral hearing devices, dysarthria, dropped head, weakness for right elbow extension and flexion, reduced tendon reflexes on the upper limbs, ataxia and brady-dysdiadochokinesia on the upper limbs, marked wasting of the thighs, ataxia on the lower limbs, truncal ataxia, and ataxic stance, and gait. Gnome calves bilaterally, which were described at age 38 were no longer present. The last medication included indapamide, furosemide/spironolactone, simvastatin, NaCl, KCl, coenzyme-Q (60 mg/d), and vitamin-D.

3. Discussion

The presented patient is interesting in several aspects. Though clinical manifestations of KSS developed already in early infancy and childhood, the majority of the typical phenotypic features (CPEO, pigmentary retinopathy, elevated CSF protein, and cardiac conduction defects) and hepatopathy were recognised not earlier than in adulthood. Possibly, the typical features of KSS required for establishing the diagnosis [1, 2] were present already earlier; however, they were not recognied before age 30. KSS was suspected for the first time at age 39. An argument in favor of the diagnosis of KSS is that the mother was not affected suggesting that there was no transmission of a pathogenic mtDNA variant but rather spontaneous occurrence of a single mtDNA deletion, which is the cause in 96% of cases [3].

Another interesting point is the phenotype. Though the patient fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for KSS, he additionally presented with a plethora of manifestations, of which some have been reported earlier in KSS. In addition to the features required for diagnosing KSS, the patient presented with the known features of diabetes [4], hypocorticism (hyponatremia) [5], short stature [6], white matter lesions [7], hypoacusis [1], migraine [8], hepatopathy [9], steatosis [10], and cataract [11]. Features so far unreported in KSS include congenital anisocoria, severe caries, liver cysts, pituitary enlargement, desquamation of hands and feet, bone chondroma, aortic ectasia, dermoidal cyst, and polyposis of nasal sinuses. Whether all these features are truly attributable to the underlying metabolic defect remains speculative and requires further investigations, but from other MIDs it is well known that such features can be part of the phenotype [12]. The reason for the high number of novel phenotypic features could be that previous cases were not thoroughly investigated or that the genetic cause of the present patient was different from that of the previous cases.

Concerning the recurrent deteriorations of the phenotype during infections or spontaneously, it cannot be excluded that these conditions were in fact seizures or stroke-like episodes (SLEs), which remained unrecognized and recovered spontaneously. At least 4 of these episodes were documented. An argument for SLEs is that MRI at the first episode at age 36 showed subcortical T2-hyperintensities, which were also hyperintense on DWI and ADC and not confined to a vascular territory, suggesting a vasogenic edema. Whether arterial hypertension should be regarded as a manifestation of the MID is questionable but there are indications from Chinese studies that arterial hypertension can be in fact a phenotypic feature of an MID [4].

Limitations of the study were that the diagnosis was not confirmed by genetic investigations, that the mother was not investigated for the presence of a MID, and that no biochemical investigations of the muscle homogenate were carried out.

In conclusion, this case shows that KSS is indeed a multisystem disease affecting all types of tissues and that the phenotypic presentation may be broader than so far anticipated.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Josef Finsterer, Michael Winklehner, Claudia Stöllberger, and Thomas Hummel contributed equally.

References

- 1.Finsterer J. Handbook of Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Taylor and Francis Group; 2019. Kearns-Sayre syndrome. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welzing L., von Kleist-Retzow J. C., Kribs A., Eifinger F., Huenseler C., Sreeram N. Rapid development of life-threatening complete atrioventricular block in Kearns-Sayre syndrome. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;168(6):757–759. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0831-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poulton J., Finsterer J., Yu-Wai-Man P. Genetic counselling for maternally inherited mitochondrial disorders. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 2017;21(4):419–429. doi: 10.1007/s40291-017-0279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin L., Cui P., Qiu Z., et al. The mitochondrial tRNA(Ala) 5587T>C and tRNA(Leu(CUN)) 12280A>G mutations may be associated with hypertension in a Chinese family. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2019;17:1855–1862. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.7143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Southgate H. J., Penney M. D. Severe recurrent renal salt wasting in a boy with a mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation defect. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 2000;37(6):805–808. doi: 10.1258/0004563001900002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berio A., Piazzi A. Multiple endocrinopathies (growth hormone deficiency, autoimmune hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus) in Kearns-Sayre syndrome. La Pediatria Medica e Chirurgica. 2013;35(3):137–140. doi: 10.4081/pmc.2013.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacher M., Fatterpekar G. M., Edelstein S., Sansaricq C., Naidich T. P. MRI findings in an atypical case of Kearns-Sayre syndrome: a case report. Neuroradiology. 2005;47(4):241–244. doi: 10.1007/s00234-004-1314-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magner M., Kolářová H., Honzik T., Švandová I., Zeman J. Clinical manifestation of mitochondrial diseases. Developmental Period Medicine. 2015;19:441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ponzetto C., Bresolin N., Bordoni A., et al. Kearns-Sayre syndrome: different amounts of deleted mitochondrial DNA are present in several autoptic tissues. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1990;96(2-3):207–210. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bresolin N., Moggio M., Bet L., et al. Progressive cytochromec oxidase deficiency in a case of earns-sayre syndrome: morphological, immunological, and biochemical studies in muscle biopsies and autopsy tissues. Annals of Neurology. 1987;21(6):564–572. doi: 10.1002/ana.410210607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fritz T., Wessel K., Weidle E., Lenz G., Peiffer J. Anästhesie für augenoperationen bei mitochondrialer enzephalomyopathie. Klinische Monatsblätter für Augenheilkunde. 1988;193(8):174–178. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1050241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nesti C., Rubegni A., Tolomeo D., et al. Complex multisystem phenotype associated with the mitochondrial DNA m.5522G>A mutation. Neurological Sciences. 2019;40(8):1705–1708. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-03864-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]