Key Points

Question

What is the effect on mortality at 90 days of reducing the exposure to vasopressors through permissive hypotension (mean arterial pressure target of 60-65 mm Hg) in intensive care unit (ICU) patients aged 65 years or older receiving vasopressors for vasodilatory hypotension?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 2600 patients aged 65 years or older with vasodilatory hypotension, treatment with permissive hypotension resulted in death at 90 days among 41.0% of patients compared with 43.8% of those receiving usual care, a difference that was not statistically significant.

Meaning

Reducing the exposure to vasopressors through permissive hypotension did not significantly reduce mortality at 90 days.

Abstract

Importance

Vasopressors are commonly administered to intensive care unit (ICU) patients to raise blood pressure. Balancing risks and benefits of vasopressors is a challenge, particularly in older patients.

Objective

To determine whether reducing exposure to vasopressors through permissive hypotension (mean arterial pressure [MAP] target, 60-65 mm Hg) reduces mortality at 90 days in ICU patients aged 65 years or older with vasodilatory hypotension.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A multicenter, pragmatic, randomized clinical trial was conducted in 65 ICUs in the United Kingdom and included 2600 randomized patients aged 65 years or older with vasodilatory hypotension (assessed by treating clinician). The study was conducted from July 2017 to March 2019, and follow-up was completed in August 2019.

Interventions

Patients were randomized 1:1 to vasopressors guided either by MAP target (60-65 mm Hg, permissive hypotension) (n = 1291) or according to usual care (at the discretion of treating clinicians) (n = 1307).

Main Outcome and Measures

The primary clinical outcome was all-cause mortality at 90 days.

Results

Of 2600 randomized patients, after removal of those who declined or had withdrawn consent, 2463 (95%) were included in the analysis of the primary outcome (mean [SD] age 75 years [7 years]; 1387 [57%] men). Patients randomized to the permissive hypotension group had lower exposure to vasopressors compared with those in the usual care group (median duration 33 hours vs 38 hours; difference in medians, –5.0; 95% CI, –7.8 to –2.2 hours; total dose in norepinephrine equivalents median, 17.7 mg vs 26.4 mg; difference in medians, –8.7 mg; 95% CI, –12.8 to −4.6 mg). At 90 days, 500 of 1221 (41.0%) in the permissive hypotension compared with 544 of 1242 (43.8%) in the usual care group had died (absolute risk difference, −2.85%; 95% CI, −6.75 to 1.05; P = .15) (unadjusted relative risk, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.85-1.03). When adjusted for prespecified baseline variables, the odds ratio for 90-day mortality was 0.82 (95% CI, 0.68 to 0.98). Serious adverse events were reported for 79 patients (6.2%) in the permissive care group and 75 patients (5.8%) in the usual care group. The most common serious adverse events were acute renal failure (41 [3.2%] vs 33 [2.5%]) and supraventricular cardiac arrhythmia (12 [0.9%] vs 13 [1.0%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients 65 years or older receiving vasopressors for vasodilatory hypotension, permissive hypotension compared with usual care did not result in a statistically significant reduction in mortality at 90 days. However, the confidence interval around the point estimate for the primary outcome should be considered when interpreting the clinical importance of the study.

Trial Registration

isrctn.org Identifier: ISRCTN10580502

This randomized clinical trial compares the effect of vasopressors guided by a mean arterial pressure (MAP) target of 60 to 65 mm Hg with a MAP level determined by the treating physician on 90-day mortality among critically ill older patients with vasodilatory hypotension.

Introduction

Vasopressors are commonly administered to patients in intensive care units (ICUs)1,2 to avoid hypotension associated with myocardial injury, kidney injury, and death.3,4 Vasopressors, however, may reduce blood flow in vasoconstricted vascular beds and are associated with effects on cardiac, metabolic, microbiome, and immune function.5 Balancing risks of hypotension with risks from vasopressors is, therefore, a challenge when managing patients in ICUs.

Blood pressure is used to guide administration of vasopressors. The 2012 Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines recommended an initial mean arterial pressure (MAP) target of 65 mm Hg with a higher target for older patients, and for those with chronic hypertension and coronary artery disease.6 Although the 2016 update7,8 acknowledged no evidence for targeting MAP values greater than 65 mm Hg in any patient group, MAP values reported in observational studies are systematically higher than 65 mm Hg,9,10 possibly because clinicians also use other targets.

Results from an individual patient data meta-analysis of 2 trials evaluating MAP targets, the SEPSISPAM (Sepsis and Mean Arterial Pressure) trial,11 and the OVATION (Optimal Vasopressor Titration) pilot trial,12 suggest that increased exposure to vasopressors resulting from higher MAP targets is potentially associated with an increased risk of death in a subgroup of older patients (≥65 years).13 In this subgroup, 28-day mortality was 37.2% compared with 45.8% (odds ratio, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.98-2.04). This led to the biological rationale that greater exposure to vasopressors may harm older patients by overwhelming their more limited physiological reserve.

This randomized clinical trial tested the hypothesis that reducing vasopressor exposure through permissive hypotension (using a MAP target of 60-65 mm Hg) among patients treated in the ICU aged 65 years or older with vasodilatory hypotension and receiving vasopressors compared with usual vasopressor exposure reduces 90-day mortality (Video).

Video. Conference Presentation: Effect of Reduced Vasopressor Exposure on Mortality in Older Critically Ill Patients With Vasodilatory Hypotension.

Francois Lamontagne, MD, of the Universite de Sherbrooke in Quebec, Canada, presented findings from the 65 trial at the Critical Care Reviews 2020 meeting (CCR20), on January 17 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. An oral editorial from Anders Perner, MD, PhD, of Copenhagen University Hospital and a Q&A session follow.

Used with permission.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

The 65 trial14 was a pragmatic, open, multicenter, parallel group, randomized clinical trial. The South Central–Oxford C Research Ethics Committee and the United Kingdom Health Research Authority approved the trial protocol, which is available in Supplement 1. The research ethics committee granted an emergency waiver of consent. The UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) convened an independently chaired (and majority independent) trial steering committee and an independent data monitoring and ethics committee. The Clinical Trials Unit at the UK Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC) managed the trial.

Sites and Patients

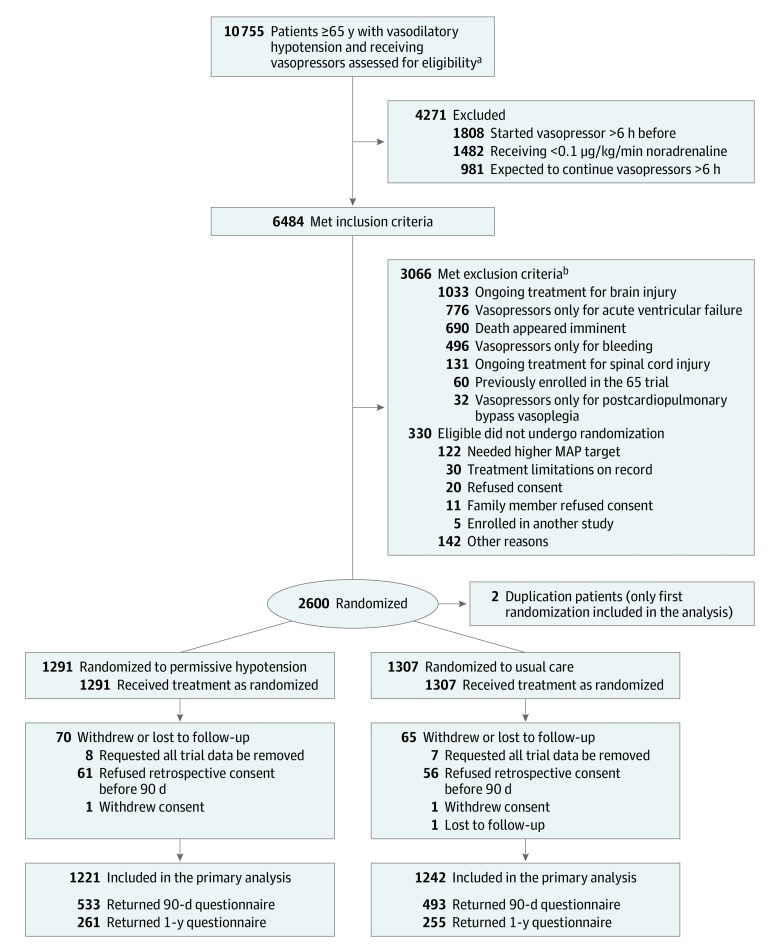

The trial was conducted in 65 UK National Health Service (NHS) adult, general, ICUs that participate in the Case Mix Programme—the national clinical audit for adult ICUs across England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Patients aged 65 years or older admitted to a participating ICU were eligible if they were randomized within 6 hours of commencing a vasopressor infusion (to minimize exposure to vasopressors prior to randomization) for vasodilatory hypotension, with adequate fluid resuscitation (as assessed by the treating clinician) completed or ongoing and vasopressors were expected to continue for 6 hours or more. In an earlier version of the protocol, randomization was permitted from the point of making the decision to commence a vasopressor infusion (Figure 1). Exclusion criteria included contraindications to permissive hypotension (eMethods in Supplement 2).

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, and Follow-Up of Patients in the 65 Trial.

aAs assessed by the treating clinician.

bSome patients met more than 1 criterion.

Screening was conducted by the clinical-research teams at each ICU. Randomization occurred as soon as possible once eligibility was confirmed. Patients were allocated in a 1:1 ratio, via a concealed central 24-hour telephone-web randomization system, to permissive hypotension or usual care. Randomization was stratified by site using permuted blocks with variable block lengths (of 4, 6, and 8).

Trial Interventions

Patients in the permissive hypotension group received vasopressors with administration guided by a MAP target of 60 to 65 mm Hg to reduce or discontinue exposure to vasopressors. The MAP target was reinforced through trial-specific prompts on infusion pumps and in medical notes and setting of upper MAP alarms. Patients in the usual care group received vasopressors at the discretion of treating clinicians allowing a more personalized approach (eg, in function of patient characteristics and markers of perfusion). Choice of vasopressor, as well as all other interventions, were also at the discretion of treating clinicians. Norepinephrine, vasopressin, terlipressin, phenylephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, and metaraminol were considered as vasopressors.

Monitoring of Adherence

Adherence was defined as appropriate reduction in dose (or discontinuation) of vasopressors when the MAP was higher than the upper target limit (65 mm Hg). Deviation was defined by failure to reduce (or discontinue) vasopressors while the MAP remained higher than 65 mm Hg for 3 consecutive hours.

Consent Procedures

For patients who did not have the mental capacity to give verbal consent prior to randomization, a “research without prior consent” approach was used. Agreement was obtained from a personal or nominated consultee as soon as appropriate following randomization. Informed consent was obtained from patients if they regained mental capacity. Data collected up to refusal or withdrawal of consent were retained. All procedures are provided in the eMethods section in Supplement 2.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 90 days after randomization.

Secondary outcomes were mortality at discharge from ICU and from the treating acute care hospital; duration of survival to longest available follow-up; duration of advanced respiratory and renal support during ICU stay; days alive and free of advanced respiratory support and renal support within first 28 days; duration of ICU and treating acute care hospital stay; cognitive decline assessed using the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE, short version)15 in survivors at 90 days and 1 year; and health-related quality of life (QOL), assessed using the EuroQoL 5-dimension 5-level (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire,16 in survivors, at 90 days and 1 year. IQCODE scores are calculated as the mean of the scores from the 16 items that range from 1 (much improved) to 5 (much worse). The EQ-5D-5L utility scale ranges from −0.285 to 1 with lower scores indicating worse health-related QOL, anchored at 0 (death) and 1 (perfect health). No studies have been conducted to establish a minimally clinically important difference (MCID) for critically ill patients aged 65 years or older with vasodilatory hypotension on either the IQCODE or EQ-5D-5L. Adverse events were monitored to ICU discharge. All definitions are in listed in the eMethods section in Supplement 2. The integrated economic evaluation for the trial will be reported separately.

Data Collection

Patients’ trial data were linked to both Case Mix Programme data, including baseline data and ICU outcomes, and NHS death registrations, for survival data. Data not contained in the Case Mix Programme—such as hourly vasopressor dose and MAP—were collected prospectively. Detailed vasopressors and MAP data are based on the first episode of vasopressors, with the end of an episode defined as a 24-hour period without receipt of vasopressors, discharge from the ICU, or death (whichever occurred first). Cognitive decline and health-related QOL were ascertained by mailed questionnaires, with telephone follow-up. Follow-up for patient-reported 1-year outcomes was stopped when the last patient reached 90 days.

Statistical Analysis

Using Case Mix Programme data, the final sample size calculation assumed a 90-day mortality of 35% for usual care with a 2.5% withdrawal or loss to follow-up; a sample size of 2600 patients (1300 per group) had 90% power to detect a 6% absolute risk reduction—approximately two-thirds of the observed absolute risk reduction in the individual patient data meta-analysis13—to 29% for permissive hypotension. An initial sample-size calculation based on the same assumptions but powered to detect an 8% absolute risk reduction was updated following the internal pilot phase on the recommendation of the trial steering committee (eMethods in Supplement 2). A single interim analysis on the primary end point was conducted after recruitment and 90-day follow-up of 500 patients, using a Peto-Haybittle stopping rule (P < .001) for early termination due to either effectiveness or harm.

Patients were analyzed according to their randomized group, following a prespecified statistical analysis plan.17 A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All tests were 2-sided with no adjustment for multiple comparisons. Doses for each vasopressor, except metaraminol, were converted to norepinephrine equivalents.18

The Fisher exact test was used to compare between-group differences in the primary outcome. Absolute risk reduction is reported with 95% CIs without adjustment as the primary effect estimate. Secondary analyses of the primary outcome included unadjusted relative risk reduction; and adjusted analysis (using multilevel logistic regression) for prespecified baseline variables (age, sex, chronic hypertension, chronic heart failure, atherosclerotic disease, dependency on assistance for daily activities, location prior to ICU admission and urgency of surgery, ICNARC physiology score,19 Sepsis-3,20 receipt of vasopressors at randomization, and duration of vasopressors prior to randomization), and site (as a random effect). Sensitivity analyses repeating the primary analysis including only patients deemed eligible in the final version of the protocol; best- and worst-case scenario analysis assuming all patients with missing primary outcome data had survived if randomized to permissive hypotension and died if randomized to usual care, and vice versa; and adherence-adjusted analysis defining adherence as a binary variable, 0 for all patients allocated to permissive hypotension with 1 or more deviation, or 1 if not, and using a structural mean model with an instrumental variable of allocated treatment to estimate the complier average causal effect of treatment.

Secondary outcomes were analyzed using unadjusted t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum test and multilevel linear regression for continuous outcomes (duration of advanced respiratory and renal support, days alive and free of advanced respiratory and renal support at day 28, duration of ICU and treating acute care hospital stay, cognitive decline, and health-related QOL at 90 days and 1 year), Fisher exact test and multilevel logistic regression for binary outcomes (mortality at discharge from ICU and treating acute care hospital), and log-rank test and Cox proportional-hazard models with shared frailty at the site level for duration of survival from randomization to longest available follow-up (proportionality was assessed visually using Kaplan-Meier curves).

Prespecified, subgroup analyses of the primary outcome testing interactions for age, chronic hypertension, chronic heart failure, atherosclerotic disease, ICNARC risk of death,19 Sepsis-3,20 and receipt of vasopressors at randomization were conducted. Likelihood ratio tests were used to compare models, with and without the relevant interaction terms. One subgroup, chronic hypertension, was also tested (prespecified) for interaction with the effect of permissive hypotension across the in-hospital secondary outcomes.

Missing values were imputed using multivariate imputation by chained equation (MICE)21 for all baseline variables included in the adjusted model and for cognitive decline and health-related QOL at 90 days and at 1 year (in patients known to be alive at each relevant time point). Models were fitted across all the imputed data sets and results combined using the Rubin rules.22 Further details of variables considered for imputation are provided in eTable 1 in Supplement 2. Stata/SE version 14.2 was used for all effectiveness analyses, and Stata/SE version 16.0 for multiple imputation (StataCorp LP).

Post hoc analyses included estimation of the absolute risk difference for the primary outcome adjusted for site only, using a generalized estimating equations (GEE) model with a binomial link and robust standard error estimates, estimation of the adjusted relative risk for the primary outcome, adjusted for the same baseline variables as previously specified, and calculation of the adjusted relative risk by prespecified subgroups, which was done using a GEE model with a Poisson link and robust standard error estimates. Mortality at days 28 and 60 was also reported as a binary outcome using only patients with nonmissing primary outcome data.

Results

Sites and Patients

Across 65 sites, a total of 10 755 patients aged 65 years or older with vasodilatory hypotension and receiving vasopressors were screened and 6484 deemed to have met the inclusion criteria. After applying the exclusion criteria, 2930 were potentially eligible and 2600 were enrolled between July 3, 2017, and March 16, 2019. Two patients were randomized twice (in error) leaving 2598 unique patients (1291 permissive hypotension, 1307 usual care) (Figure 1; and eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 2). Randomization occurred 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2). Deferred consent was used, and retrospective consent was obtained for 2461 (95%) of patients (eFigures 4 and 5 in Supplement 2), of whom 2 later withdrew consent, and 1 was lost to follow-up by 90 days, leaving 2458 patients. Five patients declined retrospective consent after 90 days and were included in the analysis until that point. As a result, 2463 patients (1221 permissive hypotension, 1242 usual care) were included in the analysis of the primary outcome. Follow-up was completed in August 2019.

The randomized groups were well matched at baseline (Table 1), except for the proportion of patients dependent on assistance for daily activities (417 [34.4%] in permissive hypotension, 380 [30.9%] in usual care group). Immediately prior to randomization, the mean MAP was 69.9 mm Hg in the permissive hypotension and 71.1 mm Hg in the usual care group.

Table 1. Patient Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No./Total (%) of Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Permissive Hypotension (n = 1283)a | Usual Care (n = 1300)a | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 75.2 (70.4-80.5) | 74.8 (70.1-80.8) |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 520/1216 (42.8) | 547/1239 (44.1) |

| Men | 696/1216 (57.2) | 692/1239 (55.8) |

| Comorbiditiesb | ||

| Chronic hypertension | 590/1283 (46.0) | 597/1299 (46.0) |

| Atherosclerotic disease | 187/1283 (14.6) | 189/1299 (14.5) |

| Chronic heart failure | 143/1283 (11.1) | 143/1298 (11.0) |

| Chronic renal replacement therapy at ICU admission | 16/1204 (1.3) | 18/1224 (1.5) |

| Daily activities status before admission to acute hospital | ||

| No assistance | 794/1211 (65.6) | 850/1230 (69.1) |

| Minor or major assistance | 409/1211 (33.8) | 375/1230 (30.5) |

| Total assistance with all activities | 8/1211 (0.7) | 5/1230 (0.4) |

| Location prior to ICU admission and urgency of surgery | ||

| Emergency department and not in hospital | 432/1219 (35.4) | 420/1239 (33.9) |

| Operating room | ||

| Elective and scheduled surgery | 53/1219 (4.3) | 60/1239 (4.8) |

| Emergency and urgent surgery | 259/1219 (21.2) | 264/1239 (21.3) |

| Other ICU | 14/1219 (1.1) | 22/1239 (1.8) |

| Ward or intermediate care area | 461/1219 (37.8) | 473/1239 (38.2) |

| APACHE II score, mean (SD) [No.]c | 20.9 (6.5) [1218] | 20.6 (6.1) [1239] |

| ICNARC physiology score, mean (SD) [No.]d | 23.9 (8.8) [1213] | 23.5 (8.8) [1239] |

| ICNARCH-2015 predicted risk of death, median (IQR) [No.]e | 0.33 (0.15-0.60) [1213] | 0.32 (0.14-0.61) [1239] |

| Sepsis-3f | ||

| No sepsis | 263/1216 (21.6) | 275/1239 (22.2) |

| Sepsis (not in shock) | 364/1216 (29.9) | 369/1239 (29.8) |

| Septic shock | 589/1216 (48.4) | 595/1239 (48.0) |

| Mean arterial pressure at randomization, mm Hgg | ||

| Mean (SD) | 69.9 (10.1) | 71.1 (11.5) |

| Median (IQR) [No.] | 69 (64-75) [1281] | 70 (64-77) [1300] |

| Vasopressor infusion(s) received at time of randomization | ||

| Norepinephrine only | 761/1265 (60.2) | 766/1280 (59.8) |

| Metaraminol only | 406/1265 (32.1) | 409/1280 (32.0) |

| Phenylephrine only | 37/1265 (2.9) | 38/1280 (3.0) |

| Epinephrine only | 3/1265 (0.2) | 5/1280 (0.4) |

| Vasopressin only | 0/1265 (0.0) | 2/1280 (0.2) |

| Dopamine only | 0/1265 (0.0) | 1/1280 (0.1) |

| Other or combination | 43/1265 (3.4) | 34/1280 (2.7) |

| Noneg | 15/1265 (1.2) | 25/1280 (2.0) |

| Norepinephrine equivalent doseh | ||

| <0.1 μg/kg/mini | 153/1265 (12.1) | 155/1280 (12.1) |

| ≥0.1 μg/kg/min | 676/1265 (53.4) | 677/1280 (52.9) |

| Duration of vasopressor infusion prior to randomization, median (IQR), min [No.] | 186 (102-277) [1247] | 186 (104-284) [1262] |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

Excludes 15 patients who refused permission of data use.

Comorbidities were selected a priori because they may constitute effect modifiers.

The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score (range, 0-71; higher scores indicate greater severity) was calculated using physiology readings in the first 24 hours of ICU admission.23

The Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC) score (range, 0-100; higher scores indicate greater severity) was calculated using physiology readings in the first 24 hours of ICU admission.24

ICNARCH-2015 predicted risk is calculated using physiology reading in the first 24 hours of ICU admission with age, comorbidities, dependency, and location before and reason for admission.

Sepsis-3 criteria requires evidence of infection and 2 or more points on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, which is based on data in the first 24 hours of ICU admission.

Patients starting vasopressors or receiving metaraminol or terlipressin boluses could be recruited for the protocol’s version 2.0, which specified their starting a vasopressor infusion at least 1 hour before randomization.

Norepinephrine equivalent doses were calculated according to the method described in Khanna et al,18 using the conversion factors: epinephrine μg/kg/min (× 1), dopamine μg/kg/min (/150), phenylephrine μg/kg/min (× 0.1) and vasopressin U min –1 ( × 2.5).

Both groups had 118 patients receiving less than 0.1 μg/kg/min of norepinephrine were eligible for recruitment prior to the protocol’s version 2.0, which specified that, for patients receiving norepinephrine, then they must fulfill a minimum dose of 0.1 μg/kg/min at the time of randomization. A minimum dose was not required for other vasopressors.

Clinical Management

Patients in the permissive hypotension group had a lower exposure to vasopressors compared with those in the usual care group—median duration 33 hours compared with 38 hours (difference, –5.0; 95% CI, –7.8 to –2.2), mean duration, 46.0 hours compared with 55.9 hours (mean difference, –9.9 hours; 95% CI, –14.3 to –5.5), and median total dose (norepinephrine equivalent), 17.7 mg compared with 26.4 mg (difference, –8.7 mg; 95% CI, –12.8 to –4.6 mg) (Table 2; eTable 2 and eFigures 6 and 7 in Supplement 2). Clinical management diverged immediately after randomization (eFigure 8 in Supplement 2), and there was a clear difference in management of vasopressors between the groups (eFigure 9 in Supplement 2). Mean and peak MAP values were lower in the permissive hypotension group (Table 2; and eFigure 10 in Supplement 2). The number of episodes of vasopressors were not significantly different between groups, with 86.8% of patients in the permissive hypotension and 86.3% in the usual care group having a single episode.

Table 2. Vasopressor Use After Randomization by Group.

| Permissive Hypotension (n = 1261)a |

Usual Care (n = 1276)a |

Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total duration of vasopressors after randomization, median (IQR), h | 33.0 (15.0 to 56.0) | 38.0 (19.0 to 67.0) | –5.0 (–7.8 to –2.2) |

| Vasopressor usage, No. (%) | |||

| Norepinephrine | 992 (78.7) | 997 (78.1) | 0.9 (−2.3 to 4.1) |

| Metaraminol | 395 (31.3) | 418 (32.8) | −1.3 (−4.9 to 2.4) |

| Vasopressin | 123 (9.8) | 126 (9.9) | −0.1 (−2.4 to 2.3) |

| Epinephrine | 40 (3.2) | 42 (3.3) | −0.1 (−1.5 to 1.3) |

| Phenylephrine | 32 (2.5) | 33 (2.6) | −0.0 (−1.3 to 1.2) |

| Terlipressin | 10 (0.8) | 14 (1.1) | −0.3 (−1.1 to 0.5) |

| Dopamine | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.2) |

| Norepinephrine equivalentsb | |||

| Total dose, mg | |||

| Median (IQR) [No.] | 17.7 (5.8 to 47.2) [1008] | 26.4 (8.9 to 65.6) [1021] | −8.7 (−12.8 to −4.6) |

| Mean dose rate, μg kg−1 min−1 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0.12 (0.06 to 0.23) | 0.15 (0.08 to 0.26) | −0.03 (−0.04 to −0.02) |

| Highest dose rate, μg kg−1 min−1 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0.26 (0.13 to 0.57) | 0.32 (0.16 to 0.63) | −0.06 (−0.09 to −0.02) |

| Metaraminolb | |||

| Total dose, mg | |||

| Median (IQR) [No.] | 22.0 (9.3 to 60.0) [395] | 35.0 (12.7 to 79.8) [420] | −13.0 (−19.5 to −6.5) |

| Mean dose rate, mg h−1 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 2.35 (1.44 to 4.25) | 2.83 (1.95 to 4.88) | −0.48 (−0.78 to −0.18) |

| Highest dose rate, mg h−1 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 4.00 (3.00 to 6.50) | 5.00 (3.50 to 7.00) | −1.00 (−1.48 to −0.52) |

| Terlipressin | |||

| Total dose, U | |||

| Median (IQR) [No.] | 2.5 (1.0 to 10.8) [10] | 3.3 (1.0 to 6.0) [14] | −0.8 (−8.5 to 6.9) |

| Time receiving vasopressor with recorded MAP | |||

| ≤65 mm Hgc | |||

| Median (IQR) h | 12 (5 to 25) | 6 (2 to 13) | |

| >65 mm Hgc | |||

| Median (IQR) h | 12 (5 to 25) | 27 (13 to 49) | |

| Mean MAP while receiving vasopressors, mm Hgd | |||

| Median (IQR) [No.] | 66.7 (64.5 to 69.8) [1247] | 72.6 (69.4 to 76.5) [1267] | −5.9 (−6.4 to −5.5) |

| Peak MAP while receiving vasopressors, mm Hgd | |||

| Median (IQR) | 83.0 (75.0 to 92.0) | 92.0 (85.0 to 100.0) | −9.0 (−10.4 to −7.6) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

Total number of patients with treatment data recorded until completion of the first treatment episode. In the permissive hypotension group, the proportions of the way in which the first episode ended were 72.8% were free of vasopressors for 24 continuous hours, 11.0% were discharged from ICU prior to being free of vasopressors for 24 continuous hours, and 16.2% died while receiving vasopressors. In the usual care group, the same proportions were 69.0%, 12.3%, and 18.7%, respectively.

See eFigure 6 in Supplement 2.

See eFigure 9 in Supplement 2.

See eFigures 8 and 10 in Supplement 2.

Adherence to Protocol

The number of patients with one or more occurrence of nonadherence was 153 (11.3%) (permissive hypotension group). Overall, nonadherence represented 6% of the total time receiving vasopressors. The main reasons for nonadherence were concerns regarding the patient’s clinical condition (renal, 36; cardiac, 4; history of chronic hypertension, 2; gastrointestinal, 2; other, 7); and logistical staff-related issues (trial awareness, 54; other clinical priorities, 42; no reason documented, 6). Targeting a lower MAP in the permissive hypotension group did not significantly increase the number of hours with MAP values lower than 60 mm Hg (eFigure 9 in Supplement 2).

Cointerventions

During the first episode of vasopressors, there was no clinically important difference in fluid balance, urine output, or the use of pure inotropes. Corticosteroids were administered to 31.6% of patients in the permissive hypotension and 33.9% in the usual care group (eFigure 11 and eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 2).

Effectiveness

At 90 days, there was no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality, with 500 deaths (41.0%) among of 1221 patients in the permissive hypotension group compared with 544 (43.8%) among 1242 patients in the usual care group (absolute risk difference, −2.85%, 95% CI, −6.75 to 1.05; P = .15). When adjusted for prespecified baseline variables, the odds ratio for 90-day mortality was 0.82 (95% CI, 0.68 to 0.98) compared with an unadjusted odds ratio of 0.89 (95% CI, 0.76 to 1.04) (Table 3). For each baseline variable that was used in the adjusted analysis, data were missing for fewer than 0.1% of patients (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Best- and worst-case sensitivity analyses yielded unadjusted odds ratios of 0.74 (95% CI, 0.63 to 0.87) and 1.08 (0.93 to 1.27), respectively. Adherence-adjusted analysis did not alter the primary results (eTable 5 in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Primary and Secondary Mortality Outcomes .

| Outcome | No./Total (%) | Unadjusted Absolute Difference | P Value | Unadjusted Relative Difference (95% CI) | Adjusted Difference (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Group | Usual Care Group | |||||

| Primary Outcome | ||||||

| 90-d mortality | 500/1221 (41.0) | 544/1242 (43.8) | −2.85 (−6.75 to 1.05) | .15 | ||

| Relative risk | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.03) | 0.92 (0.83 to 1.01)b | ||||

| Odds ratio | 0.89 (0.76 to 1.04) | 0.82 (0.68 to 0.98) | ||||

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||||

| Discharge mortality | ||||||

| ICU | 362/1212 (29.9) | 380/1237 (30.7) | −0.85 (−4.49 to 2.79) | .66 | ||

| Relative risk | 0.97 (0.86 to 1.10) | 0.95 (0.78 to 1.17)b | ||||

| Odds ratio | 0.96 (0.81 to 1.14) | 0.90 (0.73 to 1.10) | ||||

| Acute hospital | 484/1232 (39.3) | 519/1250 (41.5) | −2.23 (−6.09 to 1.63) | .27 | ||

| Relative risk | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.04) | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.03)b | ||||

| Odds ratio | 0.91 (0.78 to 1.07) | 0.86 (0.71 to 1.03) | ||||

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

Adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities, prior dependency, vasopressor infusions received at randomization, duration of vasopressor infusion prior to randomization, location prior to admission to ICU and urgency of surgery, Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC) physiology score, Sepsis-3, and random effect of site. For comparison, the unadjusted OR for the primary outcome is 0.89 (95% CI, 0.76-1.04).

Post hoc analysis.

Mortality at ICU and treating acute care hospital discharge were not significantly different, and there was no significant difference in time to death between groups (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.84 to 1.05; Figure 2). The mean duration of ICU and treating acute care hospital stay and duration and days alive and free from advanced respiratory and renal support to day 28 were not significantly different between groups. Cognitive decline (IQCODE) and health-related QOL (EQ-5D-5L) scores also were not significantly different between groups at 90 days or at 1 year (Table 4; and eFigure 12 and eTables 6 and 7 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves.

All randomized patients are included when calculating survival, excluding 8 patients in the permissive hypotension group and 7 in the usual care group who did not consent to the trial and refused permission for data use. Other surviving patients were censored at the last known date alive or at date of withdrawal or refusal of consent (from whom trial consent was not obtained). The median follow-up time (using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method) was 14.3 months (interquartile range [IQR], 8.8-19.3) for the permissive hypotension group and 14.2 months (IQR, 8.5-19.4) for the usual care group. HR indicates hazard ratio.

Table 4. Secondary Outcomes .

| Intervention Group | Usual Care | Unadjusted Absolute Difference | P Value | Adjusted Mean Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Respiratory Supporta | |||||

| Receipt, No./total (%) | 708/1218 (58.1) | 691/1239 (55.8) | |||

| Duration among those receiving support, median (IQR), d | 4 (2 to 10) | 4 (2 to 10) | 0.0 (-0.7 to 0.7) | .64 | |

| Duration among all patients, mean (SD), d | 4.5 (8.3) | 4.8 (10.0) | −0.3 (−1.1 to 0.4) | .40 | −0.3 (−1.0 to 0.4) |

| Days alive and free of advanced respiratory support to day 28, mean (SD) | 15.7 (12.8) | 15.1 (13.0) | 0.6 (−0.4 to 1.7) | .26 | 0.9 (0.0 to 1.8) |

| Renal Supportb | |||||

| Receipt, No./total (%) | 302/1218 (24.8) | 306/1239 (24.7) | |||

| Duration among those receiving support, median (IQR), d | 4 (2 to 7) | 4 (2 to 8) | 0.0 (-1.1 to 1.1) | .93 | |

| Duration among all patients, mean (SD), d | 1.4 (3.6) | 1.5 (4.1) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) | .47 | −0.2 (−0.4 to 0.1) |

| Days alive and free of renal support to day 28, mean (SD) | 17.4 (13.2) | 16.7 (13.4) | 0.6 (−0.4 to 1.7) | .25 | 0.9 (0.0 to 1.9) |

| Duration of ICU Stay, Median (IQR) [No. of Patients], d | |||||

| Survivors | 5.2 (2.9 to 10.5) [850] | 5.4 (3.0 to 9.9) [865] | −0.2 (−0.7 to 0.3) | .61 | |

| Nonsurvivors | 3.2 (0.9 to 8.1) [632] | 2.7 (0.9 to 8.7) [380] | 0.5 (−0.4 to 1.4) | .97 | |

| Duration of Acute Hospital Stay, Median (IQR) [No. of Patients], d | |||||

| Survivors | 18 (10 to 34) [732] | 18 (10 to 36) [721] | 0 (−2.1 to 2.1) | .27 | |

| Nonsurvivors | 6 (1 to 15) [484] | 5 (1 to 14.5) [519] | 1 (−0.8 to 2.8) | .92 | |

| Cognitive Decline (IQCODE Score) Among Survivors, Mean (SD) [No. of Patients]c | |||||

| At 90 d | 2.97 (0.72) [497] | 2.99 (0.76) [458] | −0.01 (−0.09 to 0.07) | .80 | −0.01 (−0.09 to 0.07) |

| At 1 y | 2.93 (0.81) [254] | 2.80 (0.96) [247] | 0.13 (−0.00 to 0.25) | .05 | 0.12 (−0.00 to 0.25) |

| Health-Related QOL (EQ-5D-5L Utility Score) Among Survivors, Mean (SD) [No. of Patients]d | |||||

| At 90 d | 0.677 (0.274) [504] | 0.683 (0.272) [464] | −0.006 (−0.038 to 0.026) | .71 | −0.000 (−0.031 to 0.031) |

| At 1 y | 0.706 (0.264) [253] | 0.716 (0.245) [241] | −0.010 (−0.050 to 0.030) | .62 | −0.011 (−0.050 to 0.028) |

| Safety Monitoring, No/Total (%) | |||||

| Any serious adverse evente | 79/1283 (6.2) | 75/1300 (5.8) | |||

Abbreviations: EQ-5D-5L, European quality of life-5 dimensions 5-level questionnaire; ICU, intensive care unit; IQCODE, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly; IQR, interquartile range.

Defined as receiving 1 or more of the following: invasive mechanical ventilatory support applied via a translaryngeal tube or applied via a tracheostomy; BPAP (bilevel positive airway pressure) applied via a translaryngeal tracheal tube or via a tracheostomy; CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) via a translaryngeal tracheal tube; extracorporeal respiratory support. Mask or hood CPAP or BPAP and high–flow nasal canula are not considered advanced respiratory support.

Either receiving acute renal replacement therapy (eg, hemodialysis, hemofiltration etc) or renal replacement therapy for chronic renal failure.

Cognitive decline scores on the IQCODE are calculated as the mean of the scores on the 16 items and range from 1 (much improved) to 5 (much worse). No studies have been conducted to establish a minimum clinical important difference (MCID) for critically ill patients aged 65 years or older with vasodilatory hypotension. Patients without completed IQCODE data had missing data imputed.

Utility scale ranges from −0.285 to 1 with lower scores indicating worse health-related QOL. The scale is anchored at 0 (death) and 1 (perfect health). Health utilities were assigned using the EQ-5D-5L value set for England.25 No studies have been conducted to establish an MCID for critically ill patients aged 65 years or older with vasodilatory hypotension. Patients without completed EQ-5D-5L data had missing data imputed.

See the Methods section for the most serious adverse events.

The number of serious adverse events was not significantly different between groups with 79 patients (6.2%) having a serious adverse event in the permissive hypotension compared to 75 (5.8%) in the usual care group (Table 4 and eTable 8 in Supplement 2). The most commonly reported serious adverse events were severe acute renal failure (permissive hypotension, 41; usual care, 33), supraventricular cardiac arrhythmia (permissive hypotension, 12; usual care, 13), ventricular cardiac arrhythmia (permissive hypotension, 12; usual care, 5), myocardial injury (permissive hypotension, 8; usual care, 12), mesenteric ischemia (permissive hypotension, 8; usual care, 12), and cardiac arrest (permissive hypotension, 11; usual care, 10).

The tests for interaction were not statistically significant for the subgroups defined by age, chronic heart failure, atherosclerotic disease, predicted risk of death, sepsis status, or vasopressor dose (Figure 3). However, for the chronic hypertension subgroup, the difference in 90-day mortality observed between the permissive hypotension (38.2%) and usual care group (44.3%) was more pronounced (adjusted odds ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.49-0.85) than for patients without chronic hypertension (43.3% vs 43.4%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.73-1.21; test of interaction, P = .047, not adjusted for multiple testing). Secondary outcomes for patients with and without chronic hypertension are detailed in eTable 9 in Supplement 2.

Figure 3. Subgroup Analyses of the Primary Outcome.

aAdjusted for age, sex, comorbidities, prior dependency, vasopressor infusions received at randomization, duration of vasopressor infusion prior to randomization, location prior to admission to intensive care unit (ICU) or urgency of surgery, Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre physiology score, Sepsis-3, and random effect of site.

bP value for test of interactions of risk ratio in adjusted generalized estimating equation (GEE) Poisson regression model.

cP value for test of interactions in the odds ratio (OR) in adjusted multilevel logistic regression model.

dThree patients in the usual care group were identified after randomization to be younger than 65 years and are included in this subgroup.

eTest of continuous linear interaction with age: adjusted OR, 0.82 (95% CI, 0.69-0.99) at age 75 years (mean value), interaction OR, 0.90 (95% CI, 0.78-1.02) per 5-year increase in age.

fTest of continuous linear interaction with predicted log odds of acute hospital mortality: adjusted OR, 0.82 (95% CI, 0.68 to 0.99) at predicted log odds of –0.64 (mean value) (predicted risk of 35%), interaction OR, 0.97 (95% CI, 0.84-1.12) per increase of 1 in predicted log odds.

gNorepinephrine equivalent doses were calculated according to the method described in Khanna et al,18 using the following conversion factors: epinephrine μg/kg/min (× 1), dopamine μg/kg/min (/150), phenylephrine μg/kg/min (× 0.1), and vasopressin U min –1 ( × 2.5).

Post Hoc Analyses

Adjustment of the primary outcome model for the effect of site (only) resulted in an absolute risk difference of −2.82% (95% CI, −7.00 to 1.36), consistent with the primary effect estimate. In addition to the prespecified subgroup analyses of the primary outcome (adjusted odds ratios), adjusted relative risks were also calculated. The relative risks for 90-day mortality were consistent with the odds ratios. In patients with chronic hypertension, the adjusted relative risk was 0.84 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.99) and in patients without chronic hypertension, the adjusted Sepsis-3 was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.88 to 1.11); test of interaction, P = .12, not adjusted for multiple testing (Figure 3). Mortality at 28 and 60 days can also be found in eTable 10 in Supplement 2.

Discussion

In this multicenter, pragmatic, randomized clinical trial, among patients aged 65 years or older, receiving vasopressors for vasodilatory hypotension, permissive hypotension compared with usual care did not result in a statistically significantly reduction in mortality at 90 days. The absolute reduction in 90-day mortality associated with permissive hypotension was 2.9% with 95% CI, from a 6.8% reduction to a 1.1% increase.

This trial has several strengths. First, it was set in a representative sample of 65 ICUs in NHS hospitals across the UK. Second, site set-up was rapid, and the trial recruited 2600 patients in 21 months with recruitment being 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Sites embedded the trial within routine clinical care due to a simple intervention delivered by bedside nurses; a use of “research without prior consent” model; nesting of the trial within routinely collected data (reducing burden); and the increasing maturity of the UK Critical Care Clinical Research Network, funding and enabling trained research nurses to deliver such trials. Third, both cognitive decline and quality of life among survivors were assessed—important outcomes valued by patients.26,27 Fourth, the usual care comparator avoided risk of artificially increasing harm in the control group. Fifth, the population was enriched by enrolling older patients considered to have a greater chance of benefiting from the intervention. Sixth, careful sensitivity analyses were conducted, including different approaches to handling missing data.

The confidence intervals for the absolute risk difference, as well as for the adjusted analyses, indicate that minimizing exposure to vasopressors in older patients with vasodilatory hypotension was unlikely to be harmful and might have been beneficial. Usual care, which allowed expert clinicians to adjust vasopressors on many parameters (eg, patient characteristics and markers of tissue perfusion), did not outperform use of a single parameter, MAP, to systematically minimize exposure to vasopressors. While the results of the adjusted analysis might suggest that minimizing exposure to vasopressors in older patients with vasodilatory hypotension may be beneficial, the survival analysis and post hoc analyses using alternative approaches to adjustment support the primary analysis.

The results suggest that there may be no harm associated with permissive hypotension and the corresponding significant reductions in exposure to vasopressors, but the study interpretation must be limited because this was not designed as a noninferiority trial. In contrast to the SEPSISPAM trial,11 the use of renal replacement therapy was not increased in patients with chronic hypertension randomized to a lower MAP target group. The suggestion of a greater benefit associated with permissive hypotension in patients with chronic hypertension, compared with those without, should be interpreted with caution. Significant subgroup comparisons with no adjustment for multiple testing alongside a nonsignificant primary analysis must be deemed exploratory. Although this suggests that it may be safe to tolerate lower MAP, even in patients with chronic hypertension, further research is required to better understand the interaction between this chronic comorbidity and vasopressors. In future studies, consideration should be given to the fact that blood pressure may vary considerably among patients identified as chronically hypertensive and that patients identified as being normotensive may experience unrecognized severe hypertension. In addition, patients who experience chronic hypertension are also at risk of other comorbidities potentially rendering them more vulnerable to vasopressor-induced adverse effects.

Limitations

This trial has several limitations. First, the intervention was not blinded, but the risk of bias was minimized through central randomization, to try to ensure concealment of group assignment, and use of a primary outcome not subject to observer bias. Second, the 90-day mortality in the usual care group was higher than anticipated using data derived from the Case Mix Programme, plausibly because trial eligibility hinged on clinical teams’ assessment that vasopressors would be required for at least 6 hours. Third, nonconsent and withdrawals were slightly higher than anticipated in the sample-size calculation. Fourth, in this pragmatic trial, no mechanistic data were collected, and attributable mortality was not adjudicated. Other trials comparing permissive hypotension with usual care are ongoing and may shed light on the effect of vasopressors on surrogate end points (NCT03431181).

Conclusions

Among patients age 65 years or older receiving vasopressors for vasodilatory hypotension, permissive hypotension compared with usual care did not result in a statistically significant reduction in mortality at 90 days. However, the confidence interval around the point estimate for the primary outcome should be considered when interpreting the clinical importance of the study.

Trial Protocol

eMethods

eFigure 1. Site opening over time - actual vs pre-trial estimate

eFigure 2. Recruitment over time - actual vs pre-trial estimate

eFigure 3. Randomization by Day of Week and Time of Day

eFigure 4. Informed consent for patients randomized to permissive hypotension

eFigure 5. Informed consent for patients randomized to usual care

eFigure 6. Vasopressor dose-rates days 1 to 7 post-randomization

eFigure 7. Time to discontinuation of vasopressors

eFigure 8. Dose-rate of norepinephrine equivalents and MAP change post-randomization

eFigure 9. Treatment hours MAP and vasopressor dose reductions

eFigure 10. MAP values days 1 to 7 post-randomization

eFigure 11. Fluid balance and urine output days 1 to 7 post-randomization

eFigure 12. Sensitivity analysis that reports the HrQoL treatment effect estimate at 90 days post-randomization according to alternative missing not at random assumptions compared to the primary and complete case analyses

eTable 1. Variables considered for multiple imputation and form of imputation model

eTable 2. Vasopressor use after randomization by group (mean values)

eTable 3. Fluid balance and urine output during first episode of vasopressors

eTable 4. Co-interventions during first episode of vasopressors

eTable 5. Secondary and sensitivity analyses of Primary Outcome

eTable 6. Quality-of-Life (EQ-5D) Health State Profiles at 90 days post-randomization

eTable 7. Summary of elicited EQ-5D-5L* scores across all usable experts (n=32)

eTable 8. Serious Adverse Events

eTable 9. Secondary Outcomes by Chronic Hypertension Status

eTable 10. Post-hoc mortality outcomes

Data Sharing Statement

Section Editor: Derek C. Angus, MD, MPH, Associate Editor, JAMA (angusdc@upmc.edu).

References

- 1.Lemasle L, Blet A, Geven C, et al. Bioactive adrenomedullin, organ support therapies, and survival in the critically ill: results from the French and European Outcome Registry in ICU Study. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):49-55. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vail EA, Gershengorn HB, Hua M, Walkey AJ, Wunsch H. Epidemiology of vasopressin use for adults with septic shock. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(10):1760-1767. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201604-259OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varpula M, Tallgren M, Saukkonen K, Voipio-Pulkki L-M, Pettilä V. Hemodynamic variables related to outcome in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(8):1066-1071. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2688-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maheshwari K, Nathanson BH, Munson SH, et al. The relationship between ICU hypotension and in-hospital mortality and morbidity in septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(6):857-867. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5218-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamontagne F, Marshall JC, Adhikari NKJ. Permissive hypotension during shock resuscitation: equipoise in all patients? Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(1):87-90. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4849-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. ; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup . Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580-637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304-377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486-552. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamontagne F, Cook DJ, Meade MO, et al. Vasopressor use for severe hypotension-a multicentre prospective observational study. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0167840-e0167840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.St-Arnaud C, Ethier JF, Hamielec C, et al. Prescribed targets for titration of vasopressors in septic shock: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2013;1(4):E127-E133. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20130006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asfar P, Meziani F, Hamel JF, et al. ; SEPSISPAM Investigators . High versus low blood-pressure target in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(17):1583-1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamontagne F, Meade MO, Hébert PC, et al. ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. . Higher versus lower blood pressure targets for vasopressor therapy in shock: a multicentre pilot randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(4):542-550. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4237-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamontagne F, Day AG, Meade MO, et al. Pooled analysis of higher versus lower blood pressure targets for vasopressor therapy septic and vasodilatory shock. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(1):12-21. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-5016-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards-Belle A, Mouncey PR, Grieve RD, et al. Evaluating the clinical and cost-effectiveness of permissive hypotension in critically ill patients aged 65 years or over with vasodilatory hypotension: protocol for the 65 randomised clinical trial [Published September 9, 2019]. J Intensive Care Soc. doi: 10.1177/1751143719870088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation. Psychol Med. 1994;24(1):145-153. doi: 10.1017/S003329170002691X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727-1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas K, Patel A, Sadique MZ, et al. Evaluating the clinical and cost-effectiveness of permissive hypotension in critically ill patients aged 65 years or over with vasodilatory hypotension: Statistical and Health Economic Analysis Plan for the 65 trial [Published online July 3, 2019]. J Intensive Care Soc. doi: 10.1177/1751143719860387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna A, English SW, Wang XS, et al. ; ATHOS-3 Investigators . Angiotensin II for the treatment of vasodilatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):419-430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrando-Vivas P, Jones A, Rowan KM, Harrison DA. Development and validation of the new ICNARC model for prediction of acute hospital mortality in adult critical care. J Crit Care. 2017;38:335-339. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818-829. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harrison DA, Parry GJ, Carpenter JR, Short A, Rowan K. A new risk prediction model for critical care: the Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC) model. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1091-1098. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259468.24532.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, Mulhern B, van Hout B. Valuing health-related quality of life: An EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):7-22. doi: 10.1002/hec.3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, et al. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors. an international modified delphi consensus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(9):1122-1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamontagne F, Cohen D, Herridge M. Understanding patient-centredness: contrasting expert versus patient perspectives on vasopressor therapy for shock. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(7):1052-1054. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4518-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods

eFigure 1. Site opening over time - actual vs pre-trial estimate

eFigure 2. Recruitment over time - actual vs pre-trial estimate

eFigure 3. Randomization by Day of Week and Time of Day

eFigure 4. Informed consent for patients randomized to permissive hypotension

eFigure 5. Informed consent for patients randomized to usual care

eFigure 6. Vasopressor dose-rates days 1 to 7 post-randomization

eFigure 7. Time to discontinuation of vasopressors

eFigure 8. Dose-rate of norepinephrine equivalents and MAP change post-randomization

eFigure 9. Treatment hours MAP and vasopressor dose reductions

eFigure 10. MAP values days 1 to 7 post-randomization

eFigure 11. Fluid balance and urine output days 1 to 7 post-randomization

eFigure 12. Sensitivity analysis that reports the HrQoL treatment effect estimate at 90 days post-randomization according to alternative missing not at random assumptions compared to the primary and complete case analyses

eTable 1. Variables considered for multiple imputation and form of imputation model

eTable 2. Vasopressor use after randomization by group (mean values)

eTable 3. Fluid balance and urine output during first episode of vasopressors

eTable 4. Co-interventions during first episode of vasopressors

eTable 5. Secondary and sensitivity analyses of Primary Outcome

eTable 6. Quality-of-Life (EQ-5D) Health State Profiles at 90 days post-randomization

eTable 7. Summary of elicited EQ-5D-5L* scores across all usable experts (n=32)

eTable 8. Serious Adverse Events

eTable 9. Secondary Outcomes by Chronic Hypertension Status

eTable 10. Post-hoc mortality outcomes

Data Sharing Statement