Abstract

In metastatic cancer, high expression levels of vitronectin (VN) receptors (integrins), FAK, and ERK5 are reported. We hypothesized that integrin-mediated ERK5 activation via FAK may play a pivotal role in cell adhesion, motility, and metastasis. ERK5 and FAK phosphorylation when metastatic MDA-MB-231 and PC-3 cells were plated on VN was enhanced. Further experiments showed coimmunoprecipitation of integrins β1, αVβ3 or αVβ5 with ERK5 and FAK. To gain better insight into the mechanism of ERK5, FAK, and VN receptors in cell adhesion and motility, we performed loss-of-function experiments using integrin blocking antibodies, and specific mutants of FAK and ERK5. Ectopic expression of dominant negative ERK5/AEF decreased ERK5 and FAK (Y397) phosphorylation, cell adhesion and haptotactic motility (micromotion) on VN. Additionally, DN FAK expression attenuated ERK5 phosphorylation, cell adhesion, and motility. This study documents the novel finding that in breast and prostate cancer cells, ERK5 is a critical target of FAK in cell adhesion signaling. Using different cancer cells, our experiments unveil a novel mechanism by which VN receptors and FAK could promote cancer metastasis via ERK5 activation.

Keywords: Integrin, FAK, ERK5, Micromotion, Adhesion

Introduction

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5, also known as Big MAPK1/ERK5) represents a relatively new mammalian signal transduction pathway. ERK5 is stimulated in response to growth factors as well as by cellular stress agents (Kato et al., 1998). Recently, a role for hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) in ERK5-mediated responses has been shown (Schweppe et al., 2006). ERK5 also regulates cytoskeletal organization, proliferation, and chemotaxis (Castro-Barros and Marshall, 2005). However, the role of ERK5 in integrin-mediated signaling has remained elusive. Previous studies have shown that MAPKK5 (MEK5) specifically acts immediately upstream of ERK5 to activate this kinase (Lee et al., 1995; Zhou et al., 1995; English et al., 1995; Wang and Tournier, 2006). The signaling components upstream of MEK5 have been poorly studied. Unlike ERK1/2, ERK5 has a large C-terminal domain that is activated by autophosphorylation. The unique structure of ERK5 suggests that its biological functions and mechanisms of regulation may be distinct from other members of the MAPK family (Hayashi and Lee, 2004; Nishimoto and Nishida, 2006). Alterations in ERK5 signaling have been observed in clinical situations. For example, ERK5 is critical for muscle cell differentiation, cardiac hypertrophy, and enhanced neuronal survival (Wang and Tournier, 2006). Aberrant regulation of the ERK5 pathway has been implicated in various malignant properties of human cancers including increased bone metastatic potential of prostate cancer cells (Hayashi and Lee, 2004; Mehta et al., 2003). Based on these findings, we have examined the novel mechanism in metastatic PC-3 cells. Overexpression of MEK5 has been reported in breast cancer cells resistant to chemotherapy (Weldon et al., 2002). However, the mechanisms of the role of ERK5 in cancer, leading to survival, proliferation, or metastasis are not known. To understand the signaling mechanisms involved in cancer progression, we set out to determine the mechanisms of ERK5 activation and its involvement in cell adhesion and motility by using metastatic MDA-MB-231 and PC-3 cells.

Both MEK5 and ERK5 have sequences that suggest that these kinases may interact with cytoskeletal elements such as actin (Hii et al., 2004). Altered regulation of the actin cytoskeleton is a common feature of malignancy. These alterations in the cytoskeleton can be directly related to cell motility (Sawhney et al., 2006). We hypothesized that integrin-mediated ERK5 activation may play a pivotal role in cell adhesion and motility. The integrin family of cell adhesion receptors consists of at least 28 heterodimers. The structure and functional diversity of the integrins is based on the non-covalent pairing abilities of the individual α and β subunits. Vitronectin receptors (integrins) play an important role in a number of biological processes like cancer metastasis, angiogenesis, and bone resorption (Pereira et al., 2004, Hood and Cheresh, 2002, Zheng et al., 1999). In metastatic breast cancer patients, higher expression levels of VN receptors are reported as compared to nonmetastatic patients (Pecheur et al., 2002). Key to molecular interactions between VN and its receptors is the recognition of the RGD sequence present in VN. Integrin antagonist peptides, designed to mimic the integrin adhesion recognition sequence GRGDSP (Gly-Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser-Pro) have shown efficacy in the treatment of cancer (Lin et al., 2006). MDA-MB-231 and PC-3 cells express RGD-binding integrins and other competitive antagonists of VN receptors have been synthesized and are in clinical trials (Gomes et al., 2004; Shimaoka and Springer, 2003). Our results demonstrate a novel functional relationship in cell adhesion and motility between VN receptors and ERK5 signaling.

In the current study, we have also examined the functional role of an important kinase belonging to the tyrosine kinase family. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is overexpressed in various tumors and its overexpression has been correlated to invasion and metastasis (Parsons et al., 2008). Recently, it was reported that 45 out of 55 breast tissue pairs (81.8%) showed upregulation of FAK protein in tumors in comparison to normal tissue (Watermann et al., 2005). These results indicate a pivotal role of FAK in neoplastic signal transduction and represent a potential marker for malignant transformation. Our results document the novel finding that in cancer cells, ERK5 is a target of upstream FAK activation. This is the first report demonstrating a role for ERK5 in cancer cell adhesion and motility via FAK signaling. Our experiments document a novel mechanism by which VN receptors and FAK could promote cancer metastasis via ERK5 activation.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines used in this study were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA). Supplemented McCoys medium (SM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from VWR Scientific/Cellgro Inc., NJ. Methylthiazole tetrazolium (MTT), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), bovine serum albumin (BSA), soy bean trypsin inhibitor (SBTI), affinity purified anti phospho ERK5 (E7153) (pThr218/pTyr220), ERK5 (C-terminus residues 789–802 with N-terminally added lysine; E1523), and polyclonal anti-actin and anti-FLAG (M2) antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). ERK5 (C-20) an affinity-purified goat polyclonal antibody raised against a peptide mapping at the C-terminus of human ERK5 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Specific function blocking mouse antihuman integrin αVβ3 monoclonal antibody (clone LM609), anti-αVβ5 (clone P1F6), and β1 (clone 6S6) were purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA) whereas the mouse isotype control IgG1 was from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); antihuman integrin αV subunit (clone P2W7) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Vitronectin was purchased from VWR-BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) and from Haematologic Technologies Inc., Essex Junction, VT. The hexapeptides GRGDSP and GRGESP were purchased from Bachem Fine Chemicals (New Mexico). The polyclonal anti-FAK phosphospecific antibodies were provided by Biosource (Camarillo, CA), whereas the rabbit anti-human C-terminal FAK was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse and rabbit peroxide-conjugated AffiniPure goat IgG (H+L) secondary antibodies were from Jackson Laboratories (West Grove, PA). The reagents for cell transfection, Oligofectamine and Lipofectamine were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbed, CA), while FuGENE 6 was purchased from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). The dominant negative FLAG-ERK5/AEF was generously provided by Dr. J.D. Lee (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA) and has been described (Kato et al., 1997). The mutant FAK Y397F was a gift of Dr. Irwin Gelman (Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY) and Dr. Parsons (University of Virginia). The construct FRNK was provided by Dr. Schlaepfer (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). Human FAK small interfering RNA (FAK siRNA) was purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO) or Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Control siRNA was obtained from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Microarrays of gold film-coated electrodes as well as the Electric Cell-substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) software (model 1600R) used for cell motility (micromotion) experiments were purchased from Applied Biophysics (Troy, NY).

Cell Culture, Cell Adhesion Kinetics and Immunoblotting -

MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at a density of approximately 1× 106 cells per 100-mm dish and were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C for three days with 5% CO2 in a supplemented McCoy’s (SM) medium containing 10% FBS (10F medium). At about 80% confluency, the medium was changed to SM (devoid of serum) for overnight. Similarly, PC-3 cells (ATCC) were cultured in F-12K medium containing 10% FBS. At about 80% confluency, the medium was changed to F-12K (devoid of serum) for overnight. All experiments were performed in the absence of serum. Cells were harvested with trypsin at 37°C and pelleted by gentle centrifugation at 800x g in a clinical centrifuge. The pellet was resuspended in SM or F-12K medium, and trypsin was quenched with soy bean trypsin inhibitor (0.5 mg/ml), further allowing the cells to recover for 1h at 37°C in a shaker incubator. Cells were then kept either in suspension or replated to attach for the indicated time periods to dishes pre-coated with VN (1 μg/ml). The precoating of culture dishes with VN was performed by incubating dishes for 2 h at 37°C. Subsequently, non specific sites were blocked with 3% BSA for three hours at room temperature and finally washed with 10 ml of cold PBS. After cell attachment at 37°C, dishes were placed on ice and washed gently with cold PBS. The cells were lysed either in suspension or after attachment to pre-coated VN dishes. The kinase lysis buffer (A) contained 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1% Nonidet P-40 along with protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM EDTA, 1μg/ml leupeptin, 1μg/ml aprotinin, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM benzamidine). The integrin lysis buffer (B) contained 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1mM MgCl2, 1% NP40, and cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sawhney et al., 2002). The cells attached to VN were harvested with 75–100 μl of lysis buffer per 100 mm dish whereas cells in suspension were lysed with 50 μl of lysis buffer. Cellular debris was removed by centrifuging the lysates in a microcentrifuge at 4°C for 20 minutes at 16,000x g. The supernatants were used for protein determination by the Bio-Rad protocol and equal amounts of protein aliquots were separated by SDS- PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting. In mobility shift assays, gels were over-run for 30 min at 110 V. For ERK5 immunoblots, membranes were blocked with 5% BSA and immunoblotted with specific antibodies in 3% BSA at room temperature for 2 h. FAK (Y397) immunoblots were blocked with 5% BSA at 4°C and incubated overnight with antibody at 4°C. In certain experiments, cells were pretreated with blocking antibodies to integrins for 30 min at 37°C prior to replating on precoated VN dishes. Membrane stripping was performed by incubating the membrane while rotating for 30 min at 50°C in 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.7) containing 2% SDS and 100 mM 2-mercaptoethanol.

Transient Transfection of Cancer Cells -

Cells were seeded at a density of 1×106 and were cultured for up to 24 h in medium containing serum. In subconfluent cultures (~ 60%), medium was changed to SM or F-12K (without serum) and cells were incubated for at least one hour for synchronization prior to transfection. Transfections were carried out using FuGENE 6 according to our previous reports (Sawhney et al., 2006; Sawhney et al., 2004). The ratio of FuGENE 6 to DNA was maintained at 10 μl of FUGENE 6 : 2.5 μg of DNA. The DNAs were mixed with the FuGENE 6 (total volume 100 μl) and set at room temperature for 45 min. The mixture was then added dropwise to each 100 mm dish and mixed gently. The cells were harvested either by trypsinization or directly lysing the cells with lysis buffer, at 48 to 64 h post-transfection. Dominant negative ERK5/AEF contains a threonine to alanine mutation at position 218 and a tyrosine to phenylalanine mutation at position 220 in the MEK5 dual phosphorylation site (Kato et al., 1997). Dominant negative FAK Y397F contains a tyrosine to phenylalanine mutation. FAK-related non kinase (FRNK) is a well-characterized dominant negative construct (Pirone et al., 2006). siRNAs were used following methodology provided by the manufacturers.

Immunoprecipitation of Protein -

Cell lysates (75–100 μg) were suspended in 300 μl of lysis buffer A or B depending on the experimental design, and rotated for 2 h with antibody (1–2 μg). Protein antibody complexes were incubated with 20 μl of protein A/G agarose beads for 30 min at 4°C. The beads were sedimented and after extensive washing with lysis buffer containing PMSF, the precipitated proteins were eluted in 2X Laemmli buffer, boiled for 7 min and separated by SDS-PAGE using 7.5% gel. The proteins were then transferred to Hybond membranes (Amersham) and analyzed by immunoblotting. To detect co-immunoprecipitated proteins, the blots were probed first with one antibody, membrane stripped with SDS/β-mercaptoethanol solution at 50°C for 30 min, and reprobed with another antibody as indicated under “Results Section” and in “Figure Legends”. In certain experiments, co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by directly immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies.

Biotinylation -

To determine cell surface expression of integrins, cancer cells were biotinylated as described previously (Sawhney et al., 2006; Sawhney et al., 2004). Briefly, subconfluent monolayers were treated with Joklik’s EDTA for 8 min at room temperature, and cells were then scraped and pelleted by centrifugation. The pellet was washed twice with cold PBS, and cells were biotinylated with NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce), 0.1 mg/ml in DMSO at room temperature for 1 h. The biotinylated cells were lysed in buffer B, sheared through a 26-gauge needle, and centrifuged at 16,000x g for 20 min at 4° C. Cell lysates were incubated with streptavidin agarose for 90 min at 4°C and beads were washed five times with lysis buffer. The beads were boiled in 2X Laemmli buffer for 7 min and supernatants were filtered through Bio-Rad columns and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. The integrins were analyzed by immunoblotting using specific antibodies against α and β subunits or against heterodimers as indicated.

Cell Adhesion Assays -

For adhesion assays, 96-well tissue culture plates were coated for 2 h at 37°C with VN at indicated concentrations, blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin for 3 h, and then rinsed once with PBS. Subsequently, the methylthiazole tetrazolium (MTT) procedure assessed by the mitochondrial conversion of the tetrazolium salt to its formazan product was followed as described previously (Sawhney et al., 2003). After trypsinization or Joklik’s EDTA treatment, breast cancer cells were preincubated at 37°C with or without blocking antibodies for 30 min to determine cell adhesion. For the inhibition of adhesion by specific monoclonal blocking integrin β1 (clone 6S6), integrin αVβ3 (clone LM609), and integrin αVβ5 (clone P1F6) were used. Equal number of cells by trypan blue exclusion counting (6 × 104 cells/well) were plated at on pre-coated VN plates and incubated for 90 min in the absence or presence of antibodies. Nonadherent cells were removed by washing with SM medium. The relative number of attached cells was determined by the MTT method. The medium containing MTT was removed in each well, 150 μl of DMSO was added to each well, and the plate was kept in agitation for 15 min in the dark to dissolve the MTT-formazan product. The absorbance of the samples was recorded at 570 nm.

Cell Motility (micromotion) Measurements by the Electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) Technique -

Cell micromotion was measured using the ECIS technique previously reported (Sawhney et al., 2006, Sawhney et al., 2002; Sawhney et al., 2004). In the current system (Model 1600R), cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/well on small gold electrodes (dia. 250 μm) at the bottom of tissue culture wells (area 0.5 cm2). The gold electrodes were preincubated with 200 μl of supplemental McCoy’s or F-12K medium without serum for overnight. A constant current source applied a noninvasive 1 μA, 4000 Hz AC signal between the small electrode and a much larger counter electrode (0.15 cm2). Any variation of current due to cell movement was recorded. The ECIS software (Applied BioPhysics, Troy, NY) calculated the resistance and capacitance values of the electrode over period of time. Attachment and movement of the cells on the electrode change the flow of the current, resulting in fluctuations in the electrode resistance and capacitance. These cellular movements are called micromotion and are a measure of the motile ability of the cell being measured (Giaever and Keese 1991). As the cells move on the electrode, the sensitive nature of the lock- in amplifier detects the fluctuations in the resistance and capacitance values (Giaever and Keese 1984). These fluctuations were analyzed statistically using ECIS software to reveal the percentage variation in resistance, which in turn is a reflection of cellular micromotion on the electrode. As the measurements are electrical, they are quantitative and generate data that can be analyzed readily to provide sensitive measurements of changes in cell behavior. ECIS detects both translational (xy plane) and vertical (z direction) movement of cells. Using this technique, cell micromotion may be determined from a single cell to confluent layers. At least three experiments were performed.

Results and Discussion

Cell Attachment to VN Activates the ERK5 Pathway in Cancer Cells -

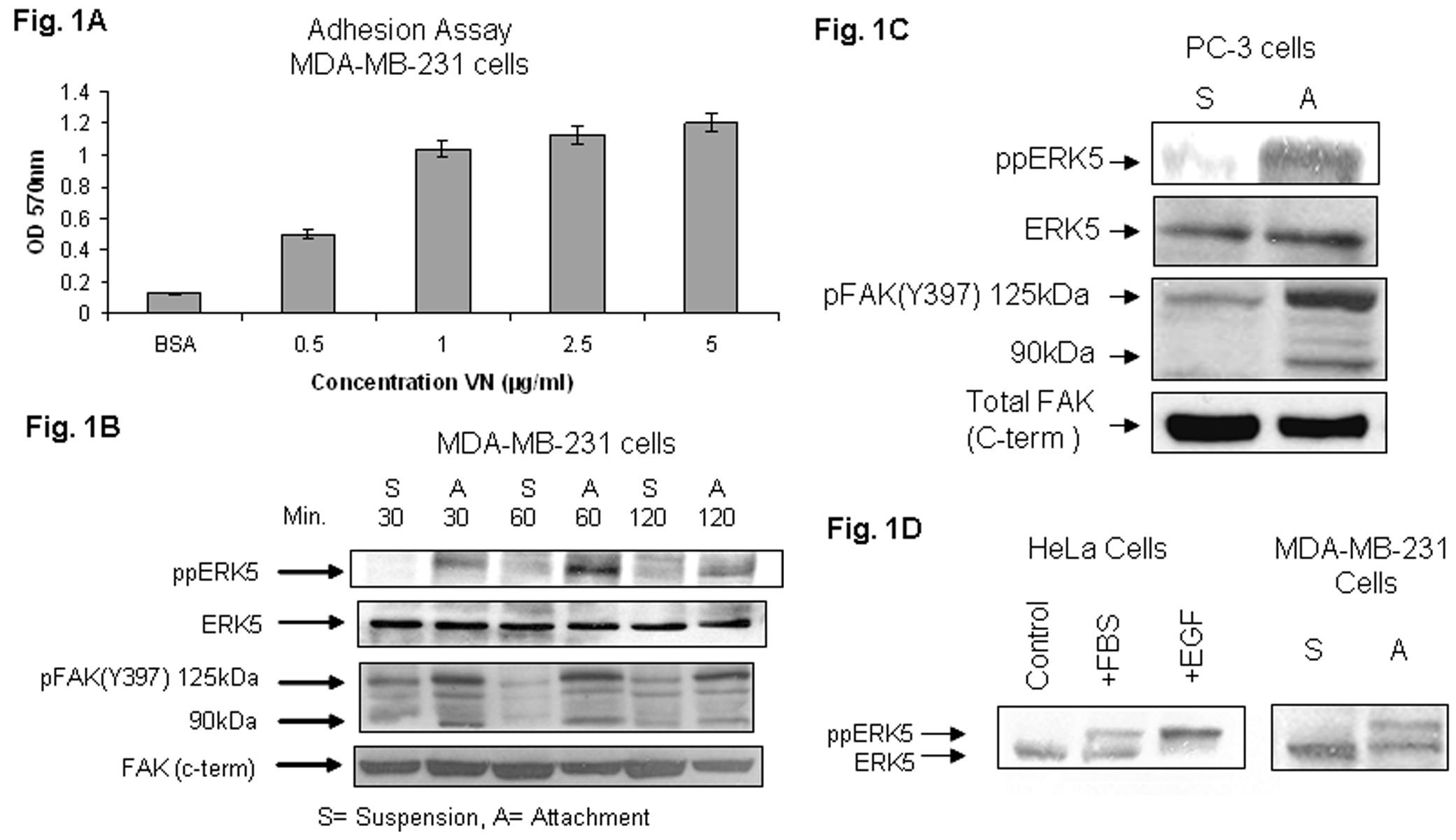

The role of integrin signaling in the activation of the ERK5 pathway in cancer is not understood. We tested whether the ERK5 pathway is involved in integrin signal transduction in breast and prostate cancer cells. Initially, we examined the kinetics for ERK5 activation after cell attachment to VN. Because there was not a significant difference in cell attachment on VN concentrations of 1–5 μg/ml (Fig. 1A), we used 1 μg/ml of VN in precoating plastic dishes. Immunoblot analyses of cell lysates using specific anti-phospho- ppERK5 (pThr 218/p Tyr 220; Sigma E7153) antibody directed to a phosphopeptide that includes the consensus phosphorylation site TEY present in the microdomain of the ERK5 activation loop, revealed a phosphorylated and active form of ERK5. In contrast to cell suspensions (S), cell adhesion (A) to VN resulted in significantly enhanced phosphorylation of approximately 120 kDa protein at all the time points (Fig. 1B; top panel). These results show that ERK5 is phosphorylated and the pathway is activated by integrin (VN receptors) signaling in MDA-MB-231 cells. These results are supported by experiments using human prostate cancer PC-3 cells (Fig. 1C; top panel).

Fig. 1.

Fig.1A. The effect of vitronectin concentration on adhesion of MDA-MB-231 cells. Ninety six-well tissue culture plates were coated with VN at 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0 μg/ml for 2 h at 37oC; nonspecific sites were blocked with BSA (3%) for 3 h and subsequently wells were washed once with PBS. Subconfluent cell cultures were trypsinized and seeded at 6 × 104 cells/well onto VN and BSA-coated plates and incubated for 90 min at 37oC. Adhesion assays were carried out as described under “Experimental Procedures”. The optical density was measured at 570 nm.

Fig. 1B. Adhesion of MDA-MB-231 cells to VN induces dual phosphorylation of ERK5 (Thr 218/Tyr 220), and phosphorylation and cleavage of FAK. MDA-MB-231 cells were trypsinized, incubated with soy bean trypsin inhibitor for at least 45 min at 37°C, and kept either in suspension or replated to dishes coated with VN (1 μg/ml) in SM medium. Cells were allowed to attach to VN for 30, 60, or 120 min at 37°C. Cellular lysates from cells in suspension (S) and cells attached (A) were analyzed for phosphorylation of ERK5 by immunoblotting with antiphospho ERK5 antibody pThr 218/pTyr220 (Top panel). The position of ppERK5 (~120 kDa) is indicated by the arrowhead. The cell lysates were also analyzed by immunoblotting for pFAK (Y397) using specific antibodies (third panel from top). The positions of pFAK (125 kDa) and its major cleaved fragment (90 kDa) are indicated by the arrowheads. ERK5 and FAK (C-terminal) are shown for equal loading.

Fig. 1C. Adhesion of prostate cancer PC-3 cells to vitronectin induces dual phosphorylation of ERK5, and phosphorylation and cleavage of FAK. PC-3 cells were trypsinized, incubated with soy bean trypsin inhibitor for 45 min at 37°C, and kept either in suspension or replated to dishes coated with VN (1 μg/ml) in SM medium. Cells were allowed to attach to VN for 60 min at 37°C. Cellular lysates from cells in suspension (S) and cells attached (A) were analyzed for phosphorylation of ERK5 by immunoblotting with antiphospho ERK5 antibody pThr 218/pTyr220 (top panel). The position of ppERK5 (~120 kDa) is indicated by the arrow. The cell lysates were also analyzed by immunoblotting for pFAK (Y397) using specific antibodies (third panel from top). The positions of pFAK (125 kDa) and its major cleaved fragment (90 kDa) are indicated by the arrowheads. Total ERK5 and FAK (C-terminal) are shown for equal loading.

Fig. 1D. Mobility shift assay. HeLa cells (left panel) were either not treated (control) or treated with fetal bovine serum (FBS; 10%) or with epidermal growth factor (EGF; 1 ng/ml) for 20 min at 370 C. The cell lysates were analyzed by Western blots using anti-ERK5 antibody. To see prominent mobility shift of ppERK5, SDS-PAGE gels were over-run for 30 min at 110 V. Right panel shows mobility shift assay of ppERK5 in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 lysates of cell suspensions (S) and VN-attached (A) cells. Figure shows bands assigned to ERK5 and dually phosphorylated ppERK5 (lower mobility band).

To demonstrate that activation of ERK5 can be detected by a retardation of the ERK5 dually phosphorylated band in Western blots, SDS-PAGE gels were over-run for 30 minutes and immunoblotted with anti-ERK5 (Sigma E1523) antibodies. First we performed experiments using HeLa cells (Fig. 1D; left panel). A gel mobility shift of ERK5 to a slower migrating form corresponds to dually phosphorylated ERK5. These results are consistent with reports in the literature (Kato et al., 1998, Schweppe et al. 2006). Following these experimental conditions, we further show band shift using lysates of MDA-MB-231 cells attached to vitronectin (Fig. 1D; right panel). The slower ERK5 migrating band is immunoreactive with anti-ppERK5 antibody (Sigma E7153) that recognizes the phosphorylated forms of the Thr218 and tyr220 required for ERK5 activation, confirming that the slower migrating band represents the phosphorylated form of ERK 5 (data not shown).

The phosphorylation of ERK5 may contribute to stabilizing ERK5 in an active conformation by the autophosphorylation of its C-terminal (Buschbeck and Ullrich, 2005). Our results showing that ERK5 is phosphorylated by both growth factor- (HeLa cells) and integrin-mediated (breast and prostate cancer cells) signals suggest that these two signaling pathways may converge at ERK5 or upstream points. Further studies will be needed to determine whether the increased phosphorylation of ERK5 by integrin has the same underlying mechanism as the activation of ERK5 following growth factor stimulation. We hypothesize that VN-mediated ERK5 phosphorylation is a critical pathway that regulates cell adhesion, motility, and metastasis.

Cell Attachment to VN Leads to FAK Activation and Cleavage -

To identify other kinases activated by cell attachment to VN, equal amounts of total protein from cell suspension and attachment lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis using specific phospho FAK (Y397) antibodies showed that in contrast to suspended cells, attachment to VN enhances tyrosine (Y) phosphorylation of FAK, and cleaves phosphorylated FAK to a 90 kDa fragment (Fig. 1B; third panel from top). Cells in suspension showed little or no FAK cleavage. MDA-MB-231 cells attached to VN exhibited FAK cleavage at all indicated time points. Experiments using PC-3 cells (Fig. 1C; third panel from top) further support that cancer cell attachment to VN leads to FAK activation and cleavage. Interestingly, we found that phosphorylation for both ERK5 and FAK was enhanced on cell attachment to VN in both cell lines. Notably, we observed that on cell attachment, FAK is cleaved to a 90 kDa fragment which we showed recently to play a critical role in cell motility (Sawhney et al., 2006). It is possible that on attachment to VN, levels of the 90 kDa fragment do not change and only tyr phosphorylation is modified. Previously we showed that, in addition to caspases, μ-calpain is the specific protease responsible for FAK cleavage (Sawhney et al., 2006).

The increase in phosphorylation of both ERK5 and FAK on VN indicated a potential relationship between ERK5 and FAK by cell adhesion signaling. The signaling relationship between FAK and ERK5 is not known in the literature. We believe that ERK5 is a target of FAK in mediating the metastatic process.

Little is known about the upstream signaling events that lead to ERK5 activation. FAK is a non receptor tyrosine kinase that plays a critical role in integrin-mediated signal transduction. FAK is overexpressed in some types of cancers including breast and prostate cancer (Berrier and Yamada, 2007). Autophosphorylation of Y397 may be an initial step in FAK activation and serves to recruit other signaling molecules like C-src, PI3K, Grb2, Grb7, and other binding proteins which then phosphorylate other FAK tyrosine residues, increasing FAK activity.

Our experiments show for the first time that in integrin-mediated signaling, ERK5 is recruited by upstream activated FAK. The 90 kDa fragment in the immunoprecipitation experiments confirmed it to be a FAK fragment (data not shown). Recently, analyses of tissue specimens of breast cancer patients showed that the 90 kDa FAK fragment was seen only in cancer specimens and not in normal control samples from the same patient (Watermann et al., 2005). We believe that FAK cleavage is related to progression of breast cancer. These observations are consistent with our recent findings that FAK cleavage specifically contributes to enhanced cancer cell motility (Sawhney et al., 2006).

FAK Mutant Inhibits ERK5 Activation, Cell Adhesion, and Micromotion -

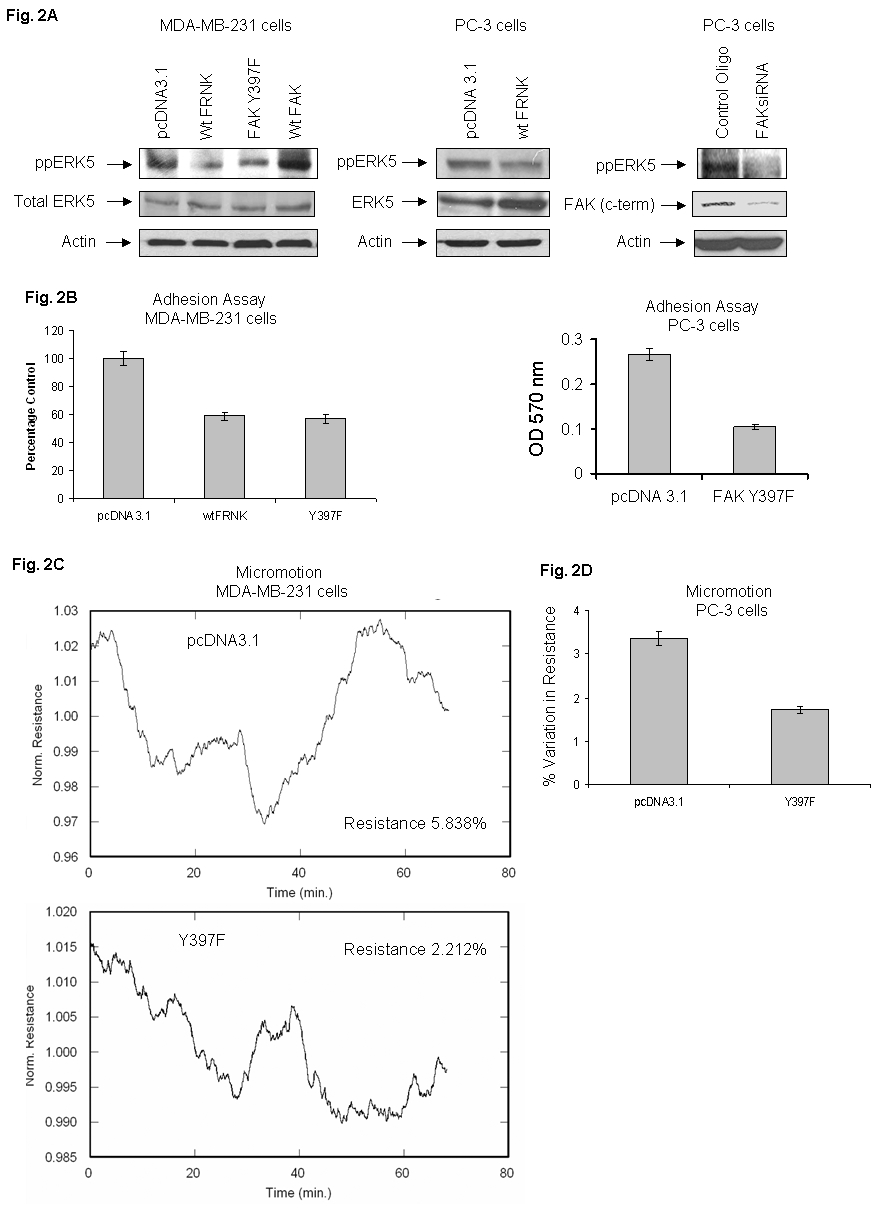

The mechanism(s) of ERK5 activation and its role in cancer cell adhesion and motility is not known. To determine the role of ERK5 via FAK signaling in cell adhesion, MDA-MB-231 cells were transiently transfected with empty vector (pcDNA 3.1), wt FRNK, FAK Y397F or with wt FAK. Wild-type FRNK or FAK Y397F act as dominant negative mutants of FAK and interfere with FAK signaling (Sieg et al., 2000). Figure 2 shows that mutant transfectants inhibit ERK5 phosphorylation (Fig. 2A; left panel), thus showing that ERK5 is downstream of FAK. These results identify for the first time that ERK5 is a target of FAK. Possibility of interaction between ERK5 and FAK mediated by proteins/kinases of the putative FAK/ERK5 complex can not be excluded. The novel concept is supported by experiments using PC-3 cells. Cells were transfected either with the FAK mutant (Fig. 2A; middle panel) or with FAKsiRNA (Fig. 2A; right panel). Blockade of ERK5 phosphorylation and FAK protein expression following siRNA-mediated knockdown was shown by Western blotting.

Fig. 2. Dominant negative FAK mutants inhibit ERK5 phosphorylation (A), cell adhesion (B), and micromotion (C).

MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with appropriate empty vectors, , wt FRNK or FAK Y397F or with wt FAK constructs in SM medium. (A) Cell lysates from empty vector, DN transfectants, or wtFAK were analyzed by Western blot using specific antiphospho ppERK5 antibody (left upper panel) or with ERK5 antibodies (left lower panel). (Middle panel): Transfection of PC-3 cells with empty vector or with wt FRNK was performed as detailed in “Experimental Procedures” and lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using specific antibodies. (Right panel): PC-3 cells were transfected with control oligo or FAK siRNA (112 nM) using Lipofectamine in F-12K medium according to supplier’s guidelines. The lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with specific antibodies for ppERK5 or FAK (c-term). Actin levels are shown for equal loading. (B) Left panel shows a comparison of MDA-MB-231 cell adhesion on VN by empty vector (pcDNA3.1 and DN FAK constructs. Right panel shows dominant negative mutant of FAK inhibit PC-3 cell adhesion. (C) Left panels show a comparison of micromotion between empty vector pcDNA3.1 and Y397F transfectant using MDA-MB-231 cells. Right panel (D) shows a comparison of micromotion between empty vector pcDNA3.1 and Y397F using PC-3 cells. Micromotion experiments were performed using ECIS in precoated VN microarray wells.

Similarly adhesion assays using VN as a substrate showed inhibition (approximately 42 %) by mutant transfectants as compared to controls in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2B; left panel). Similarly, we observed 61% inhibition in adhesion when PC-3 cells were transfected with FAK Y397F (Fig. 2B; right panel). Furthermore, the effect of Y397F transfection on cell micromotion using VN substrate was examined. Figure 2C (left panel) shows that the percentage variation in resistance (5.84%) of empty vector transfected cells was reduced by 62% in Y397F transfected cells (percentage variation in resistance 2.21%). These results are supported by experiments using PC-3 cells. Figure 2D shows that the percentage variation in resistance (3. 35%) of empty vector transfected cells was attenuated by 48% in FAK Y397F transfected cells (percentage variation in resistance 1.73%). Our study shows that FAK functions upstream of ERK5 to regulate its activation, cell adhesion, and motility (micromotion).

These results indicate a potential general novel signaling mechanism that FAK may regulate integrin-mediated cell adhesion and motility via ERK5.

FAK function is dependent on two distinct domains, the tyrosine kinase domain within the amino terminal half of the protein and the FAT domain within the COOH-terminal half of the protein. FAK is negatively regulated by the expression of Tyr kinase mutant Y397F and carboxyl-terminal mutant FAK-related non kinase (FRNK). The mutant Y397F inhibits the cellular responses to adhesion by preventing the localization of FAK to sites of integrin clustering. Cell micromotion may have significance in cancer metastasis. As previously described, ECIS technique was used for quantitative determination of micromotion (Sawhney et al., 2006; Sawhney et al., 2004; Sawhney et al., 2003). The changes in voltage across the electrodes were recorded by the lock-in amplifier once every second for measuring micromotion. The important point is to compare the statistical nature of these fluctuations between control and the dominant negative transfected cells. There should be no correlation between the swings (fluctuations) in impedance. Based on the statistical percentage variation in resistance, we found that the reduction in cell micromotion of MDA-MB-231 cells by the DN mutant as compared with control transfectants. These locomotion fluctuations may be considered as the cell signature of a particular cell phenotype, and is a measurable and reproducible quantity (Giaever and Keese 1993).

These results delineate a novel integrin-activated “inside out” integrin/FAK/ERK5 pathway by which cancer cells regulate cell adhesion and motility. These signals may be potential targets in inhibition of metastatic spread.

Mutant ERK5/AEF Attenuates ERK5 Phosphorylation, Cell Adhesion and Motility Functions -

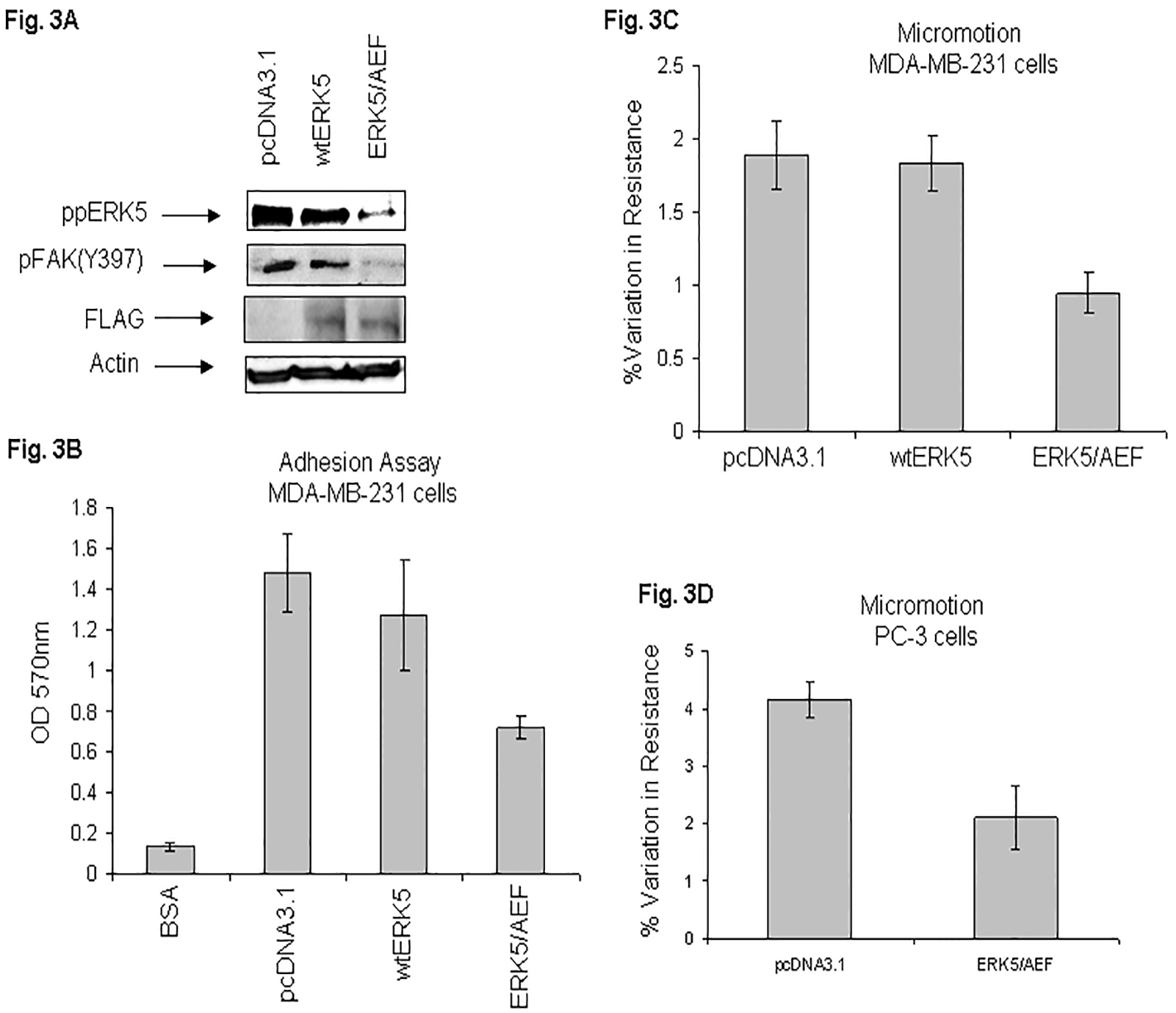

Since MDA-MB-231 cells enhance ERK5 phosphorylation on attachment to VN (Fig. 1), we further examined the mechanism of ERK5 signaling initiated by integrin in cell motility. To definitively show that ERK5 is a target of FAK activation, we transfected MDA-MB-231 cells with FLAG-tagged mutant ERK5/AEF. The lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using phospho specific antibodies against phospho ERK5 and FAK (Y397). Figure 3A shows that the mutant ERK5/AEF blocked ERK5 and FAK (Y397) phosphorylation (Fig. 3A; top two panels). We have demonstrated expression of the wt or dominant negative form of ERK5 by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 3A; third panel from top). These results unequivocally support the novel concept that ERK5 is a target of FAK activation. Further studies will be needed to determine whether it is due to a direct relationship between ERK5 and FAK phosphorylation or mediated by other proteins/kinases.

Fig. 3. Dominant negative ERK5 mutant attenuates ERK5 phosphorylation, FAK (Y397) phosphorylation, and VN-mediated cell adhesion and micromotion.

MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected in SM medium either with empty vector (pcDNA3.1), or transfected with FLAG-tagged wt ERK5 or DN ERK5/AEF mutant as described under “Experimental Procedures”. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot using specific phospho ERK5 antibody (top panel), phospho FAK (Y397) antibody (second from top panel) or actin antibody for equal loading control (bottom panel). Membrane was stripped and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG antibody (third panel from top) (A). The transfectants were seeded in a 96-well plate precoated with VN and analyzed by MTT method as described in “Experimental Procedures” (B). Fig. 3C shows comparison of micromotion between the empty vector, wt ERK5, and mutant transfectant as determined by the ECIS technique. Fig. 3D shows comparison of micromotion between the empty vector and mutant transfectant using PC-3 cells. Results are shown as bar graphs.

Dominant negative mutant ERK5/ AEF is a nonphosphorylatable mutant in which thr218 and tyr220 residues at the activating phosphorylation sites (TEY) are replaced by alanine and phenylalanine, respectively (Kato et al., 1997).

The importance of ERK5 signaling was demonstrated by overexpression of mutant ERK5/AEF which inhibited the phosphorylation of ERK5, cell attachment and motility in MDA-MB-231 cells. Adhesion assays showed that cell attachment to VN was decreased (52%) by the DN mutant as compared with empty vector transfectant (Fig. 3B). These results show that the phosphorylation of ERK5 at thr 218 and tyr 220 sites promote cell adhesion. To further elaborate the role of integrin-mediated activation of ERK5 in haptotactic motility, ECIS micromotion assays were performed with the transfectants. Figure 3C shows that the percentage variation in resistance (1.89%) of empty vector transfected cells was reduced by 50% in ERK5/AEF transfected cells (percentage variation in resistance 0.94%). Importantly, we observed that the DN mutant ablated VN-mediated micromotion. Also, it is noteworthy that inhibition of micromotion was directly linked to inhibition in ERK5 activation (pThr218/pY220) by the mutant as determined by Western blotting (Fig. 3A; top panel). These micromotion results were supported by experiments using PC-3 cells. Figure 3D shows that the percentage variation in resistance (4.16%) of empty vector transfected cells was reduced by 49% in ERK5/AEF transfected cells (percentage variation in resistance 2.11%).

The ability of a nonphosphorylatable DN mutant form of ERK5 to decrease ERK5 phosphorylation, cell adhesion and motility of cancer cells suggest that ERK5 signaling contributes to the enhanced motility and thus the potential metastatic nature of human cancer via integrin-dependent mechanism. Our current experiments provide a novel mechanistic insight about FAK function in the regulation of cell motility. Here, we show for the first time that VN-mediated cell adhesion signaling plays a critical role in the regulation of ERK5 phosphorylation. This is the first study that identifies the non-receptor tyrosine kinase FAK can recruit and phosphorylate ERK5. Our studies identify at least two phosphorylation sites (Thr 218 and Tyr 220) of ERK5 by FAK which are important in functional cell motility. It is believed that cancer cells switch to a more motile state thus increasing the metastatic potential of a tumor cell. The current study reveals that FAK regulates cell motility via multiple MAPK pathways. We identify a novel functional interaction between integrin, FAK, and ERK5.

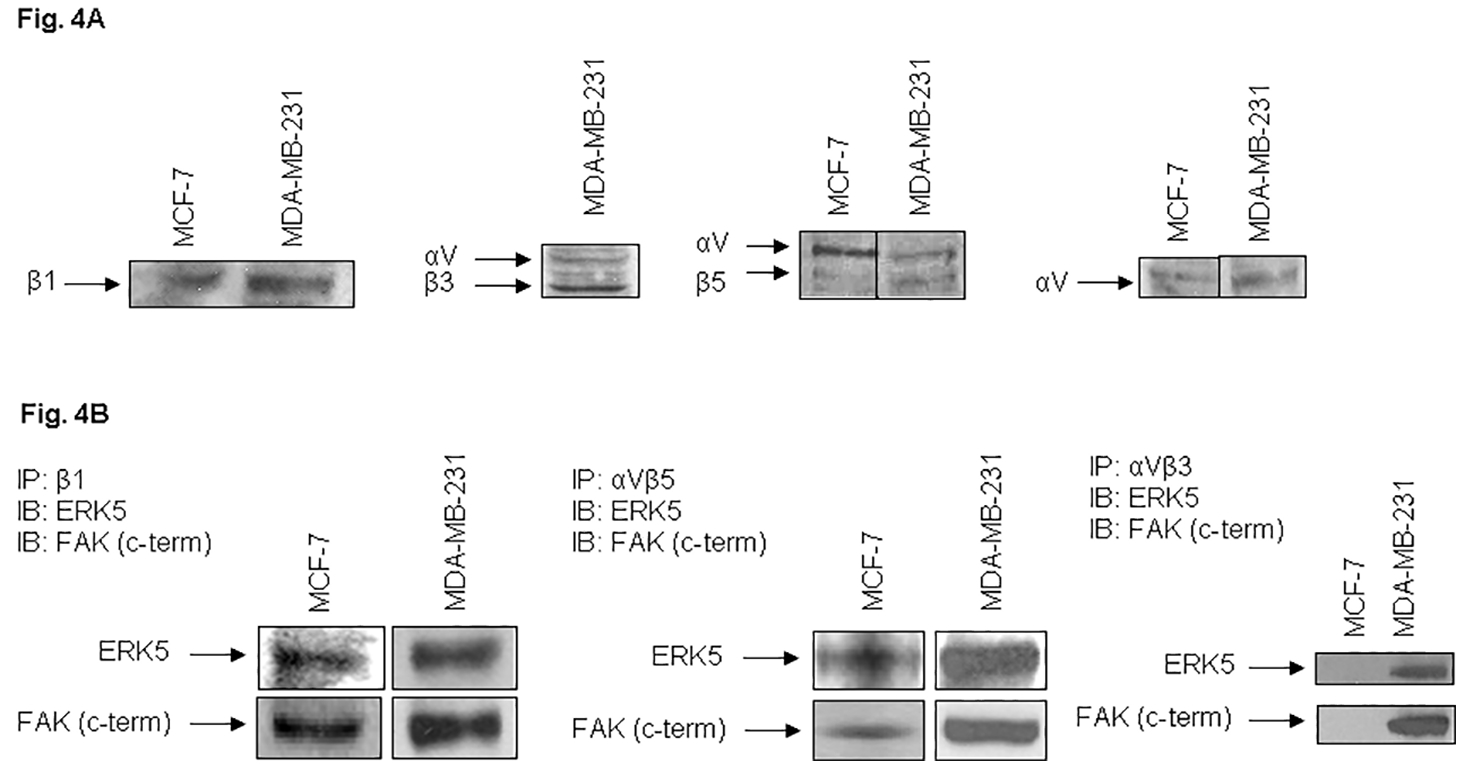

Vitronectin Receptors Co-Immunoprecipitate ERK5 and FAK-

To determine the role of VN receptor(s) in FAK and ERK5 phosphorylation, expression of various VN receptors was examined. Cells were cultured in 10F medium for 3–4 days, medium was changed overnight to SM and cells were harvested by trypsinization or by Joklik’s EDTA. Cells were biotinylated and lysed as described previously (Sawhney et al., 2003). The lysates were analyzed by Western blotting or by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting for protein expression of integrin αV, β1, αVβ3 and αVβ5 using specific antibodies. Figure 4A shows the expression of various subunits or heterodimers in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells. Our results show that lysates of MCF-7 breast cancer cells, used as control, do not express or express undetectable low levels of integrin αVβ3. These results are consistent with recent report (Cao et al; 2006).

Fig. 4. Expression of vitronectin receptors β1, αVβ3, αVβ5, and αV (A) and co-immunoprecipitation of ERK5 and FAK with vitronectin receptors (B).

MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were harvested at near confluency and lysed by integrin lysis buffer. MCF-7 cells served as controls. The lysates were analyzed by 7.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with antibodies against human integrin subunits or heterodimers as detailed in “Experimental Procedures” and “Results” (A). The lysates were immunoprecipitated with integrin antibodies as indicated and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. The membranes were immunoblotted either with ERK5 or with FAK (C-terminal) antibodies (B).

To establish a functional relationship between integrins, ERK5, and FAK, breast cancer cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies against integrin β1, αVβ3 or integrin αVβ5. The immunoprecipitates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to membrane and immunoblotted by the integrin antibodies. The membranes were either stripped and immunoblotted or directly immunoblotted with specific ERK5 or FAK antibodies. MDA-MB-231 cells showed strong signals of ERK5 or FAK (Fig. 4B). Lysates of MCF-7 cells which do not express integrin αVβ3 heterodimer, did not coprecipitate either ERK5 or FAK, demonstrating the specificity of coprecipitation of integrin/ERK5/FAK in MDA-MB-231 cells. These results show that FAK and ERK5 are recruited to VN receptors in breast cancer cells.

Integrin ligation normally induces phosphorylation through “outside-in” signaling and activation of cytoplasmic kinases. Mostly, integrins are expressed on the cell surface in an inactive form (low affinity conformation). It has been demonstrated that intracellular signals can activate integrins into conformations of high affinity and thus integrins bind ligands effectively (Hood and Cheresh, 2002). Thus a complex process of cancer metastasis may be profoundly influenced by the integrin active conformations.

Functional Blocking mAb to Integrins αVβ3, αVβ5, and β1 Attenuate ppERK5 and pFAK Phosphorylation, Cell Adhesion and Haptotactic Micromotion-

Vitronectin receptors respond to cell adherence on the basis of the RGD sequence present in VN. To assess the contribution of RGD receptors in cell adhesion, assays on VN-coated wells were performed in the presence of synthetic antagonist hexapeptides GRGDSP or GRGESP. The latter served as a control peptide. The peptide GRGDSP (1 mM) completely inhibited cell adhesion to VN (data not shown).

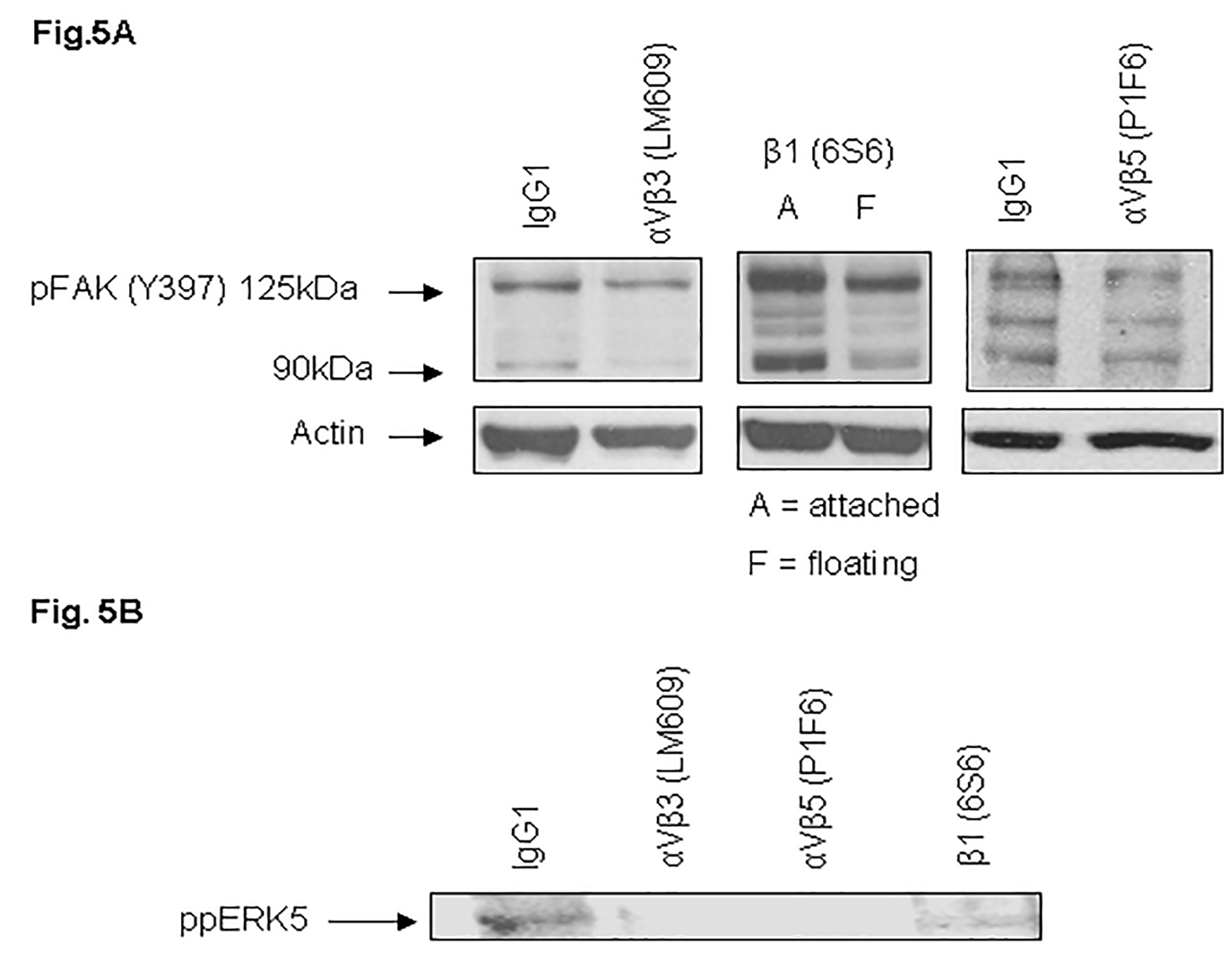

To further determine specific VN receptors that contribute to FAK and ERK5 phosphorylation, MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with specific VN receptor blocking antibodies for 30 min at 37°C prior to replating on pre-coated VN dishes, 96-well plates or microarrays. The phosphorylation of FAK (Y397) (Fig. 5A) and ERK5 (Thr218/tyr220) (Fig. 5B) was significantly blocked by αVβ3 (LM609), αVβ5 (P1F6), and β1 (6S6) antibodies as compared to control MDA-MB-231 cells. These results further support a functional relationship between VN receptors, ERK5, and FAK.

Fig. 5. Blocking antibodies against vitronectin receptors inhibit phosphorylation of FAK (A) and ERK5 (B).

MDA-MB-231 cells after trypsinization in SM medium were preincubated either in the presence of IgG1 (control) or with blocking antibodies against vitronectin receptors (LM609; left panel, 6S6; middle panel, P1F6; right panel) for 30 min. Cells were replated on VN-coated dishes and incubated for 1 h at 37°C in the absence or presence of antibodies. Lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot using an antibody specific to phosphorylated FAK (Y397) (A) or ppERK5 (B). On treatment with antibody 6S6, we observed a significant of number of floating cells, therefore, both attached (A) and floating (F) cells were lysed and immunoblotted with FAK (Y397) antibodies.

We showed expression of integrins αV, β1, αVβ3, and αVβ5 in MDA-MB-231 cells. The adhesion receptor integrin αVβ3 is selectively expressed on a variety of cells. A humanized anti-αVβ3 antibody (Vitaxin/MEDI 522) is in clinical trials for metastatic cancer and angiogenesis (Parsons, 2003; Cai et al., 2006; McNeel et al., 2005; Gasparini et al., 1998). Due to its clinical significance, integrin αVβ3 is one of the most intensely studied of the integrin receptors. Our experiments demonstrate for the first time that VN receptors, including integrin αVβ3, coimmunoprecipitate FAK and ERK5. To confirm a functional relationship between VN receptors, FAK, and ERK5, cells were treated with functional blocking antibodies to integrins. This resulted in decrease in FAK and ERK5 phosphorylation (Fig. 5), cell adhesion and micromotion (Fig. 6).

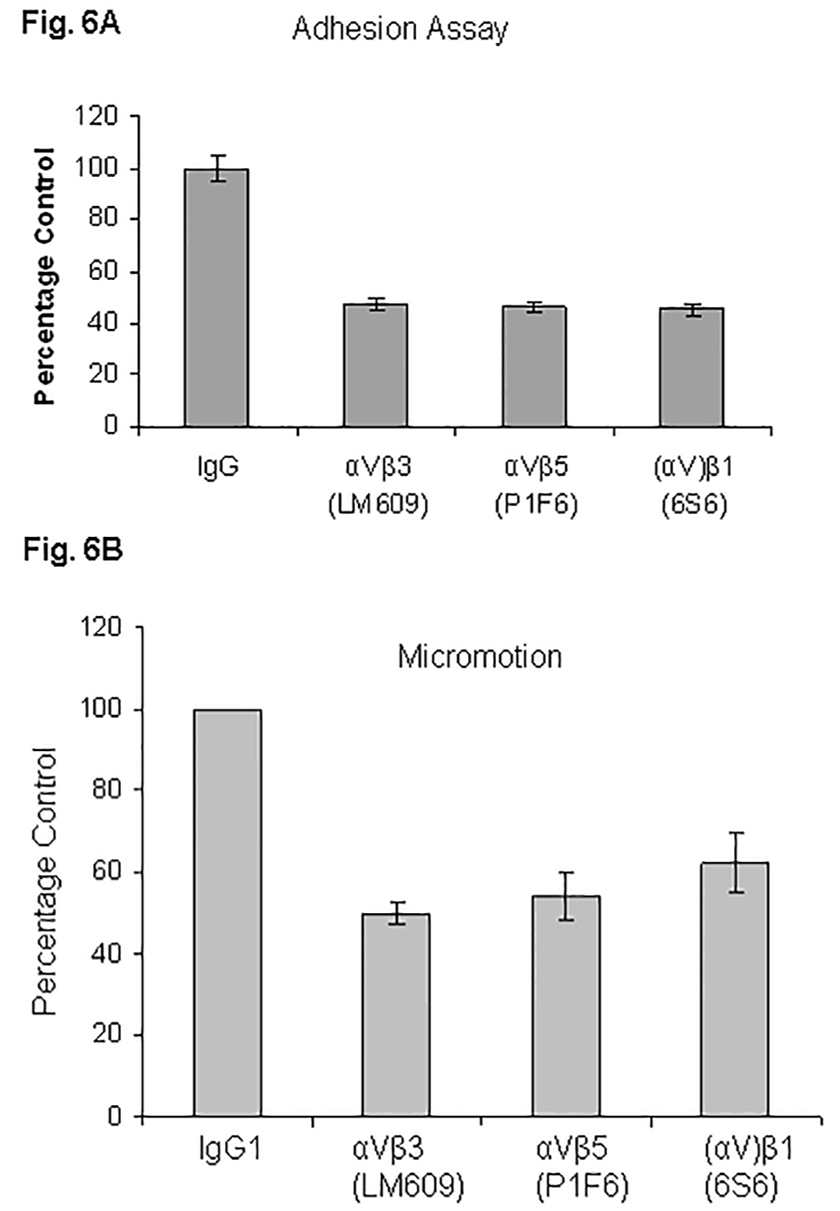

Fig. 6. Blocking antibodies against vitronectin receptors attenuate cell adhesion (A) and micromotion (B).

MDA-MB-231 cells after trypsinization in SM medium were preincubated either in the presence of IgG1 (control) or with blocking antibodies against vitronectin receptors for 30 min. Cells were replated on VN-coated 96-well plates for adhesion assays (A) or on microarrays for micromotion experiments (B). Experiments were performed as detailed in “Experimental Procedures”. At least three experiments were performed.

The role of VN receptors in mediating adhesion of breast cancer cells was determined by treatment with specific functional blocking antibodies to inhibit binding to VN. MDA-MB-231 cells were allowed to attach to VN in the absence or presence of mAbs specific for integrins αVβ3, αVβ5, and β1. As shown in Fig. 6A, cell attachment to VN was significantly inhibited (~52%) with mAb LM609 against integrin αVβ3, about 54% with mAb P1F6 against integrin αVβ5, and about 55% with mAb 6S6 against integrin β1. These results show that VN receptors αVβ3, αVβ5, and (αV)β1 significantly contribute to cell adhesion in MDA-MB-231 cells.

To establish that cell micromotion on VN was specifically integrin -mediated, MDA-MB-231 cells were preincubated for 30 min either with mouse IgG or with function blocking monoclonal antibodies against integrin β1 (clone 6S6), αVβ3 (clone LM609) and αVβ5 (clone P1F6) before seeding on the electrode wells. Micromotion was recorded by the ECIS technique. Micromotion on VN was attenuated by 50% with mAb LM609 against integrin αVβ3, about 46% with mAb P1F6 against integrin αVβ5, and about 38% with mAb 6S6 against integrin β1. The data are presented in Figure 6B.

Cell adhesion signaling has been shown to play pivotal roles in a number of cellular events, including cell motility (Posey et al., 2001). In cell motility function, there is a critical balance between cell attachment and cell detachment. There has to be an optimal concentration of the ligand for cell motility (Mitra et al., 2005; Schwartz and Horwitz 2006). We observed that cells seeded on VN-coated (0.5–1.0 μg/ml) electrodes showed higher fluctuations than cells seeded on uncoated electrodes, indicating that VN enhances cell micromotion (data not shown). Our results demonstrate that homologous integrins ((αV)β1, αVβ3, and αVβ5) contribute significantly to cell adhesion and micromotion in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 6). The ligation of VN receptors leads to the activation of FAK and ERK5, the critical components for cell motility. It has been suggested that the highly conserved NPXY motif of the C-terminal segment of the β3 cytoplasmic domain is involved in tyr phosphorylation of FAK (Liu et al., 2000).

In summary, we show here with several lines of evidence that ERK5 contributes in a novel integrin signaling cascade that involves the interaction of VN receptors and FAK. Our study suggests that continuing research into the signaling pathways that are intrinsic to the motility phenotype hold the promise for the development of new and more effective antimetastatic strategies. Currently, no specific small molecule inhibitors of the ERK5 cascade are known, thus this pathway offers opportunities to develop novel antimetastatic small molecules. Our experiments unveil a novel mechanism by which VN receptors and FAK could promote cancer metastasis via ERK5 activation. Identification of novel signaling pathways that are involved in tumor progression have important clinical implications. Our results with breast and prostate cancer cells signify the importance of this general mechanism in cancer biology. We propose to test in the future that ERK5 pathway contributes to metastasis in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Charles Wenner and Dr. Fengzhi Li for their critical review of the manuscript. We also like to thank Maria Orsino, Majed Aggi, Jennie Hauser, and Michelle Vinci for their technical assistance. We are indebted to the laboratories of Drs. Candace Johnson and Allen Gao for providing prostate cancer cells. This work was performed at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute.

Grant information: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA 16056, 54807, 34432, and 50457, by the Oncologic Foundation of Buffalo and by the Shelby Rae Tengg Foundation.

Literature Cited

- Berrier AL and Yamada KM (2007). Cell-matrix adhesion. J Cell Physiol. 213, 565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschbeck M and Ullrich A (2005). The unique C-terminal tail of the mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK5 regulates its activation and nuclear shuttling. J. Biol. Chem 280, 2659–2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W, Wu Y, Chen K, Cao Q, Tice DA, and Chen X. (2006). Characterization of 64Cu-labeled abegrinTM, a humanized monoclonal antibody against integrin {alpha}v{beta}3. Cancer Res. 66, 9673–9681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q, Cai W, Li T, Yang Y, Chen K, Xing L, and Chen X. (2006). Combination of integrin siRNA and irradiation for breast cancer therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 351, 726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Barros J, and Marshall CJ (2005). Activation of either ERK1/2 or ERK5 MAP kinase pathways can lead to disruption of the actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Sci 118, 1663–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English JM, Vanderbilt CA, Xu S, Marcus S, and Cobb MH (1995). Isolation of MEK5 and differential expression of alternatively spliced forms. J. Biol. Chem 270, 28897–28902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini G, Brooks PC, Biganzoli E, Vermeulen PB, Bonoldi E, Dirix LY, Ranieri G, Miceli R, and Cheresh DA (1998) Vascular integrin alpha(v)beta3: a new prognostic indicator in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 4, 2625–2634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever I and Keese CR (1993). A morphological biosensor for mammalian cells. Nature 366, 591–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever I and Keese CR (1991). Micromotion of mammalian cells measured electrically Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 88, 7896–7900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever I and Keese CR (1984). Monitoring fibroblast behavior in tissue culture with an applied electric field. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 81, 3761–3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes N, Vassy J, Lebos C, Arbeille B, Legrand C, and Fauvel-Lafeve F (2004) Breast adenocarcinoma cell adhesion to the vascular subendothelium in whole blood and under flow conditions: effects of alphav beta3 and alphaIIb beta3 antagonists. Clin.Exp. Metastasis 21, 553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M and Lee JD (2004). Role of the BMK1/ERK5 signaling pathway: lessons from knockout mice J. Mol. Med 82, 800–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hii CS, Anson DS, Costabile M, Mukaro V, Dunning K, and Ferrante A (2004). Characterization of the MEK5-ERK5 module in human neutrophils and its relationship to ERK1/ERK2 in the chemotactic response J. Biol. Chem 279, 49825–49834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood JD and Cheresh DA (2002). Role of integrins in cell invasion and migration. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Kravchenko VV, Tapping RI, Han J, Ulevitch RJ, and Lee JD (1997). BMK1/ERK5 regulates serum-induced early gene expression through transcription factor MEF2C. EMBO J. 16, 7054–7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Tapping RI, Huang S, Watson MH, Ulevitch RJ, and Lee JD (1998). Bmk1/Erk5 is required for cell proliferation induced by epidermal growth factor. Nature 395, 713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Ulevitch RJ, and Han JH (1995). Primary structure of BMK1: a new mammalian map kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 213, 715–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HY, Lansing L, Merillon JM, Davis FB, Tang HY, Shih A, Vitrac X, Krisa S, Keating T, Cao HJ, Bergh J, Quackenbush S, and Davis PJ (2006) Integrin alphaV beta3 contains a receptor site for resveratrol. FASEB J. 20, 1742–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Calderwood DA, and Ginsberg MH (2000). Integrin cytoplasmic domain-binding proteins. J. Cell Sci 113, 3563–3571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeel DG, Eickhoff J, Lee FT, King DM, Alberti D, Thomas JP, Friedl A, Kolesar J, Marnocha R, Volkman J, Zhang J, Hammershaimb L, Zwiebel JA, and Wilding G (2005). Phase I trial of a monoclonal antibody specific for alphav beta3 integrin (MEDI-522) in patients with advanced malignancies, including an assessment of effect on tumor perfusion. Clin. Cancer Res 11, 7851–7860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PB, Jenkins BL, McCarthy L, Thilak L, Robson CN, Neal DE, and Leung HY (2003) MEK5 overexpression is associated with metastatic prostate cancer, and stimulates proliferation, MMP-9 expression and invasion. Oncogene 22, 1381–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra SK, Hanson DA, and Schlaepfer DD (2005) Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nature Rev. 6, 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto S and Nishida E (2006). MAPK signalling: ERK5 versus ERK1/2. EMBO Rep 7, 782–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT (2003). Focal adhesion kinase: the first ten years. J. Cell Sci 116, 1409–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Slack-Davis J, Tilghman R and Roberts WG. (2008). Focal adhesion kinase: targeting adhesion signaling pathways for therapeutic intervention. Clin Cancer Research 14, 627–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecheur I, Peyruchaud O, Serre CM, Guglielmi J, Voland C, Bourre F, Margue C, Cohen-Solal M, Buffet A, Kieffer N, and Clezardin P. (2002) Integrin alpha(v)beta3 expression confers on tumor cells a greater propensity to metastasize to bone. FASEB J. 16, 1266–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira J, Meyer T, Docherty SE, Reid HH, Marshall J, Thompson EW, Rossjohn J, and Price JT. (2004) Bimolecular interaction of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein-2 with alphav beta3 negatively modulates IGF-I-mediated migration and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 64, 977–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirone DM, Liu WF, Ruiz SA, Gao L, Raghavan S, Lemmon CA, Romer LH, and Chen CS. (2006) An inhibitory role for FAK in regulating proliferation: a link between limited adhesion and RhoA-ROCK signaling, J. Cell Bio 174, 277–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posey JA, Khazaeli MB, DelGrosso A, Saleh MN, Lin CY, Huse W, and LoBuglio AF. (2001) A pilot trial of Vitaxin, a humanized anti-vitronectin receptor (anti alpha v beta 3) antibody in patients with metastatic cancer. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm 16, 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney RS, Cookson MM, Omar Y, Hauser J, and Brattain MG (2006) Integrin alpha 2-mediated ERK and calpain activation play a ritical role in cell adhesion and motility via focal adhesion kinase signaling: identification of a novel signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem 281, 8497–8510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney RS, Cookson MM, Sharma B, Hauser J, and Brattain MG. (2004). Autocrine transforming growth factor a regulates cell adhesion by multiple signaling via specific phosphorylation sites of p70S6 kinase in colon cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem 279, 47379 – 47390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney RS, Sharma B, Humphrey LE, and Brattain MG. (2003) Integrin α2 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase are functionally linked in highly malignant autocrine transforming growth factor-α-driven colon cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem 278, 19861 – 19869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney RS, Zhou G-HK, Humphrey LE, Ghosh P, Kreisberg JI, and Brattain MG. (2002) Differences in sensitivity of biological functions mediated by epidermal growth factor receptor activation with respect to endogenous and exogenous ligands. J. Biol. Chem 277, 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MA and Horwitz AR. (2006). Integrating adhesion, protrusion, and contraction during cell migration. Cell 125, 1223–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweppe RE, Cheung TH, and Ahn NG. (2006). Global gene expression analysis of ERK5 and ERK1/2 signaling reveals a role for HIF-1 in ERK5-mediated responses. J. Biol. Chem 281, 20993–21003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimaoka M, Springer TA. (2003). Therapeutic antagonists and conformational regulation of integrin function. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2, 703–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieg DJ, Hauck CR, Ilic D, Klingbeil CK, Schaefer E, Damsky CH, and Schlaepfer DD. (2000) FAK integrates growth-factor and integrin signals to promote cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol 2, 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X and Tournier C. (2006). The activity status of cofilin is directly related to invasion, intravasation, and metastasis of mammary tumors. Cell. Sig 18, 753–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watermann DO, Gabriel B, Jager M, Orlowska-Volk M, Hasenburg A, zur Hausen A, Gitsch G, and Stickeler E. (2005) Specific induction of pp125 focal adhesion kinase in human breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 93, 694–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weldon CB, Scandurro AB, Rolfe KW, Clayton JL, Elliot S, Butler NN, Melnik LI, Alam J, McLachlan JA, Jaffe BM. (2002) Identification of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase as a chemoresistant pathway in MCF-7 cells by using gene expression microarray. Surgery 132, 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D-Q, Woodard AS, Fornaro M, Tallini G, Languino LR. (1999) Prostatic carcinoma cell migration via αvβ3 Integrin is modulated by a focal adhesion kinase pathway. Cancer Res. 59, 1655–1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Bao ZQ, and Dixon JE. (1995). Components of a new human protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J. Biol. Chem 270, 12665–12669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]