Abstract

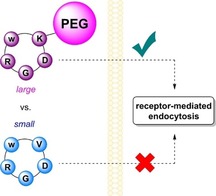

Monomeric RGD peptides show unspecific fluid‐phase uptake in cells, whereas multimeric RGD peptides are thought to be internalized by integrin‐mediated endocytosis. However, a potential correlation between uptake mechanism and molecular mass has been neglected so far. A dual derivatization of peptide c(RGDw(7Br)K) was performed to investigate this. A fluorescent probe was installed by chemoselective Suzuki–Miyaura cross‐coupling of the 7‐bromotryptophan and a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) linker was attached to the lysine residue. Flow cytometry and live cell imaging confirmed unspecific uptake of the small, non‐PEGylated peptide, whereas the PEG5000 peptide conjugate unveiled a selective internalization by M21 cells overexpressing αvβ3 and no uptake in αv‐deficient M21L cells.

Keywords: halogenated tryptophan, internalization, poly(ethylene glycol), RGD peptides, selective uptake

Mass matters: Uptake of RGD peptides depends on the molecular size as investigated with a large PEGylated and a small non‐PEGylated peptide. Only the PEGylated peptide is found in αvβ3‐overexpressing cells, while the small peptide also enters αv‐negative cells.

Integrins play a crucial role in cell adhesion and signaling. In particular, RGD‐binding integrins emerged as targets for selective tumor therapy as they regulate processes like apoptosis, metastasis, or angiogenesis, and are overexpressed on malignant cells, while being downregulated on most healthy cells.1, 2 Since their first discovery in the late 1980s3 a variety of ligands targeting integrins like αvβ3 were developed. However, prominent small‐molecule ligands as cilengitide,4 c(RGDf(NMe)V), failed in clinical trials also due to its ambiguous role in angiogenesis.5 Nevertheless, 18F‐galacto‐RGD and derivatives are currently under clinical investigation and show promising results as a positron emission tomography tracer.6 Especially because much is known about the relationship between structure and activity for RGD ligands, they represent a versatile and easily accessible toolkit for drug targeting. In this context, the internalization pathway into the target cell is an important issue.

As shown previously, monomeric RGD peptides undergo a fluid‐phase rather than a clathrin‐dependent uptake.7 Interestingly, a tetrameric regioselective addressable functionalized template peptide (RAFT‐RGD‐Cy5) does not only provide higher affinity toward αvβ3 but was shown to undergo clathrin‐mediated internalization.8 Thus, multivalent RGD peptides are considered superior for in vivo studies. However, in a contradictory report Ga‐labeled trimeric and monomeric ligands were compared. It was found that improved in vitro properties of multimers were not consistent with better in vivo performance.9 These case studies demonstrate the complex interaction patterns and show that predictions of translation from in vitro to in vivo are not straightforward.

In the last decades, a variety of RGD‐drug conjugates has been synthesized for targeted drug delivery.10 However, the pathway of uptake was only studied sparingly and reports are conflicting. For example, studies by us revealed colocalization of an RGD‐cryptophycin‐52 conjugate with lysosomes in WM‐115 cells11 (overexpressing αvβ3) and in contrast, an RGD‐cryptophycin‐55 conjugate was internalized both by M21 (overexpressing αvβ3) and M21L (αv knockout) cells.12 Likewise, cytotoxic RGD‐α‐amanitin conjugates did not provide specific uptake.13 It was further demonstrated that a monomeric RGD‐doxorubicin conjugate afforded good binding affinities toward αvβ3 in a cell adhesion assay, but was not internalized.14 Additionally, RGD conjugates tend to accumulate on the cell surface as described for c(diketopiperazine‐RGD)‐sCy5 conjugates.15 However, in vivo experiments confirmed that numerous multivalent RGD conjugates are associated with improved uptake at tumor sites.16, 17 These findings indicate that integrin‐mediated endocytosis is favored for peptides with multifold RGD sites.

We wondered whether the route of internalization solely correlates with multivalency or whether it might be affected by merely increasing the size of a monomeric RGD peptide. As this has not yet been investigated to the best of our knowledge, we synthesized monomeric RGD peptides differing in size and investigated a potential correlation with the mode of uptake.

c(RGDw(Br)V)‐derived peptides containing a halogenated d‐Trp residue w(Br) were chosen as an intermediate for late‐stage dual modification. Halotryptophans can selectively be synthesized by biocatalytic halogenation effecting regioselective bromination of the indole ring. They represent versatile handles for chemoselective installation of aryl moieties by cross‐coupling reactions, which can eventually be used to generate fluorescent probes.18, 19, 20 In particular, a large aromatic system as in the pyrene derivative (1) permits an excitation (λ ex: 365 nm) suitable for biological applications (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). Structure–activity relationship studies on c(RGDfV) disclosed that any amino acid can be incorporated instead of valine without significantly compromising bioactivity.21, 22

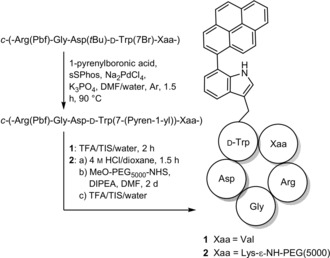

This allows for the use of lysine in this position, enabling a dual, chemoselective late‐stage modification using bromotryptophan for cross‐coupling and lysine for nucleophilic substitution. PEGylation has become a popular method to increase blood circulation times, enhance stability toward enzymatic degradation and bioavailability.24, 25 For our experiments, a 5 kDa PEG linker was attached to increase the size relative to peptide 1. The crude peptide was treated with 4 m HCl/dioxane to selectively cleave the Boc protecting group. The peptide was purified by RP‐HPLC before addition of the NHS‐activated PEG moiety and the PEGylated intermediate was purified prior to Pbf cleavage, as separation of unreacted PEG and PEGylated peptide could only be achieved at this stage. Precipitation by diethyl ether after removal of protecting groups gave peptide 2 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Dual late‐stage functionalization of RGD peptides by cross‐coupling and PEGylation. Cross‐coupling was performed similarly as described previously.23 The tBu protecting group is cleaved under the applied reaction conditions, which does not cause any side reactions during PEGylation. sSPhos=sodium 2′‐dicyclohexylphosphino‐2,6‐dimethoxy‐1,1′‐biphenyl‐3‐sulfonate hydrate; DIPEA=N,N‐diisopropylethylamine; TFA=trifluoroacetic acid; TIS=triisopropylsilane; NHS=N‐hydroxysuccinimide.

Affinities toward isolated integrins αvβ3 and α5β1 were determined in a competitive ELISA (Table 1). Peptide 1 shows somewhat decreased affinity toward αvβ3 relative to the reference cilengitide (3), but an improved selectivity over α5β1. Interestingly, peptide 2 exhibits similar affinities toward αvβ3 in comparison with reference peptide 3. As demonstrated previously, substitution of valine by lysine does not have a major impact on the affinity.22 Previous studies have demonstrated increased as well as decreased affinity for peptides modified at lysine with different spacers,26, 27 chelators,28 or peptides with short PEG linkers.29, 30 Loss in affinity can mostly be ascribed to the steric bulk of conjugates that hinder interactions with the binding pocket. However, larger molecules may have a greater ability to interact unspecifically with the protein surface at more sites and thus, decrease dissociation leading eventually to apparent affinity.31

Table 1.

Affinities determined by an ELISA using purified, isolated integrins.

|

No. |

Sequence |

IC50 [nm] |

Ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

αvβ3 |

α5β1 |

|

|

1 |

c(RGDw(pyren‐1‐yl)V) |

5.11±0.90 |

2079±237 |

1:41 |

|

2 |

c(RGDw(pyren‐1‐yl)K(PEG5000)) |

0.88±0.03 |

73.6±10.7 |

1:84 |

|

3 |

c(RGDf(NMe)K) |

0.54±0.02 |

15.4±4.0 |

1:29 |

Cellular internalization was studied in vitro. M21 cells overexpress αvβ3, whereas the variant M21L lacks αv and thus does not express αv integrins.12 As described previously, uptake of monomeric RGD peptides is fluid‐phase dependent,7, 8 whereas for multimeric peptides internalization is clathrin‐dependent.8 We investigated by flow cytometry (FC) as a quantitative method and live cell imaging as a qualitative method to which extent molecular size can influence cellular uptake.

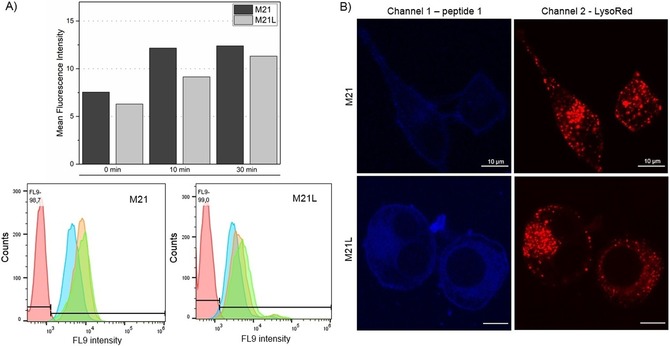

For flow cytometry studies, cells (2×106) were incubated with peptides (30 μm) for 0, 10, or 30 min, washed with buffer and analyzed. Interestingly, the 0 min samples already show strong fluorescence for both cell lines that increases slightly with longer incubation times (Figure 1 A). As M21L cells do not present integrin αvβ3, uptake of peptide 1 proceeds in an integrin‐independent fashion.7 The large shift between the negative control (no peptide) and the 0 min sample is caused by ionic interactions of positively charged Arg side chains with negatively charged phospholipids of the membrane resulting in an accumulation of RGD peptides on the cell surface.15, 32 Therefore, the localization of peptides was further studied by live cell imaging. Cells were grown overnight on glass‐slip chambers and first counterstained with LysoTracker Red DND‐99 before incubation with peptide (5 μm) for 10 min. Careful but thorough washing steps were performed prior to analysis by confocal microscopy. Care was taken not to detach the semi‐adherent M21L cells which lack αv integrins responsible for adherence. As shown in Figure 1 B, peptide 1 is hardly internalized and shows strong interaction with the cell membrane. Moreover, the peptide present inside the cell is not colocalized with lysosomes indicating integrin‐independent uptake like reported previously.10, 23

Figure 1.

Uptake studies with peptide 1. A) Flow cytometry analysis after incubation of cells with peptide 1 (30 μm) for 0 min (blue), 10 min (orange), and 30 min (green). No peptide was added in the negative control (red). B) M21 and M21L cells were stained with LysoTracker Red DND‐99 and incubated for 10 min with peptide 1 (5 μm) prior to fluorescence microscopy. In combination both experiments clearly show an unspecific, fluid‐phase uptake of peptide 1.

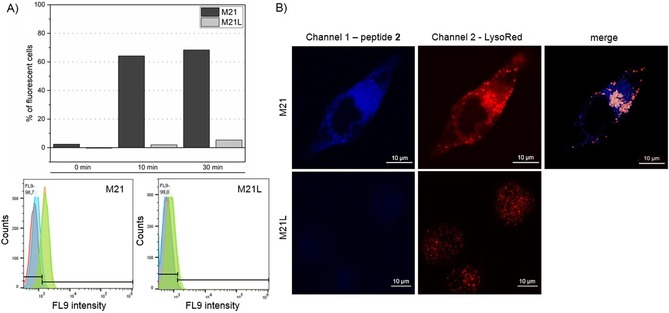

In contrast, flow cytometry reveals significant fluorescence for peptide 2 in M21 cells but not for αv deficient M21L cells (Figure 2 A). Contrary to peptide 1, the negative control (no peptide) largely overlaps with the 0 min samples. Fluorescence imaging confirmed the presence of peptide inside the cells by z‐stacking (Figure S2). Furthermore, peptide 2 colocalizes largely with lysosomes (Figure 2 B). As peptide 2 is barely found inside M21L cells, integrin‐mediated endocytosis can be concluded. Other internalization studies with a 10 kDa PEGylated peptide were unsuccessful: no peptide fluorescence was detected during live cell imaging or flow cytometry (Figure S3). We assume that this conjugate is either highly prone to bind to residual serum proteins still present from cultivation or the larger PEG shields integrin binding.33

Figure 2.

Internalization studies with peptide 2. A) For flow cytometry peptide 2 (30 μm) was incubated with cells for 0 min (blue), 10 min (orange), and 30 min (green). No peptide was added in the negative control (red). Analysis revealed an uptake of peptide 2 only by M21 cells. B) Live cell imaging of peptide 2 confirmed specific uptake only for M21 cells. For a better signal‐to‐noise ratio higher concentrations of peptide 2 (10 μm) were applied. The gain was adjusted in channel 1 to ensure the absence of peptide 2 in M21L cells. White spots in merged channels represent colocalization with lysosome.

An additional negative control experiment was performed to support integrin‐mediated endocytosis for peptide 2. Integrin αvβ3 was incubated with a monoclonal anti‐αvβ3 antibody for 15 min on ice to block but not internalize αvβ3 integrins. Subsequent incubation with peptides 1 and 2 gave significant fluorescence for peptide 1, yet not for 2 (Figure S4). Furthermore, incubation of peptide 1 at 37 and 4 °C, respectively, resulted in significantly decreased uptake at 4 °C (Figure S5), which again supports specific uptake.

These results strongly support that in vitro integrin‐mediated endocytosis for monomeric RGD peptides can be triggered by attaching a PEG linker. We hypothesize that steric and physicochemical effects contribute to this switch in uptake pathway. Similar to findings that particle size influences whether endocytosis is clathrin‐ or caveolae‐mediated,34 the increased size of peptide 2 could favor integrin‐mediated over a fluid‐phase uptake. However, the hydrodynamic radius of a 5 kDa PEG (2.3 nm) is only slightly increased in comparison with a 10 kDa dextran (1.9 nm), which is commonly applied as a fluid‐phase marker.35 Therefore, the PEG linker might also minimize ionic interactions with the membrane preventing an accumulation on the cell membrane or enhances conformational changes of the integrin and thus, promote internalization. It also can be envisaged that upon binding of PEGylated peptide its local concentration increases initiating self‐assembly and thus, creating a multivalent ligand.36 Despite the uncertainties as to why PEGylation induces integrin‐mediated internalization, these results question whether multivalency is the ultimate prerequisite for integrin‐mediated endocytosis.

In summary, dual late‐stage functionalized RGD peptides were synthesized to elucidate the influence of size for integrin‐mediated endocytosis. Bromotryptophan as a non‐canonical amino acid and lysine served as platforms to chemoselectively introduce a fluorescent probe and PEG linker. Interestingly, PEGylation of a monomeric RGD peptide effects integrin‐mediated endocytosis and presents a new approach to obtain monomeric conjugates suitable for specific targeting.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SE609/16‐1) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Prof. Dr. Horst Kessler and his group for support concerning the ELISA‐type affinity assay and Dr. Veronica Dodero for helpful discussions. We appreciate technical support in confocal microscopy by Dr. Thorsten Seidel and by Prof. Dr. Thomas Hellweg and his group on absorption and fluorescence measurements.

I. Kemker, R. C. Feiner, K. M. Müller, N. Sewald, ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 496.

References

- 1. Nieberler M., Reuning U., Reichart F., Notni J., Wester H.-J., Schwaiger M., Weinmüller M., Räder A., Steiger K., Kessler H., Cancers 2017, 9, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu Z., Wang F., Chen X., Drug Dev. Res. 2008, 69, 329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pierschbacher M. D., Ruoslahti E., Nature 1984, 309, 30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dechantsreiter M. A., Planker E., Mathä B., Lohof E., Hölzemann G., Jonczyk A., Goodman S. L., Kessler H., J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 3033–3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reynolds A. R., Hart I. R., Watson A. R., Welti J. C., Silva R. G., Robinson S. D., Da Violante G., Gourlaouen M., Salih M., Jones M. C., Jones D. T., Saunders G., Kostourou V., Perron-Sierra F., Norman J. C., Tucker G. C., Hodivala-Dilke K. M., Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen H., Niu G., Wu H., Chen X., Theranostics 2016, 6, 78–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castel S., Pagan R., Mitjans F., Piulats J., Goodman S., Jonczyk A., Huber F., Vilaró S., Reina M., Lab. Investig. J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 2001, 81, 1615–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sancey L., Garanger E., Foillard S., Schoehn S., Hurbin A., Albiges-Rizo C., Boturyn D., Souchier C., Grichine A., Dumy P., Coll J.-L., Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 837–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maschauer S., Einsiedel J., Reich D., Hübner H., Gmeiner P., Wester H.-J., Prante O., Notni J., Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katsamakas S., Chatzisideri T., Thysiadis S., Sarli V., Future Med. Chem. 2017, 9, 579–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nahrwold M., Weiß C., Bogner T., Mertink F., Conradi J., Sammet B., Palmisano R., Royo Gracia S., Preuße T., Sewald N., J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 1853–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borbély A., Figueras E., Martins A., Esposito S., Auciello G., Monteagudo E., Di Marco A., Summa V., Cordella P., Perego R., Kemker I., Frese M., Gallinari P., Steinkühler C., Sewald N., Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bodero L., López Rivas P., Korsak B., Hechler T., Pahl A., Müller C., Arosio D., Pignataro L., Gennari C., Piarulli U., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 407–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burkhart D. J., Kalet B. T., Coleman M. P., Post G. C., Koch T. H., Mol. Cancer Ther. 2004, 3, 1593–1604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raposo Moreira Dias A., Pina A., Dean A., Lerchen H.-G., Caruso M., Gasparri F., Fraietta I., Troiani S., Arosio D., Belvisi L., Pignataro L., Dal Corso A., Gennari C., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 1696–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fan Z., Chang Y., Cui C., Sun L., Wang D. H., Pan Z., Zhang M., Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhao J., Li S., Jin Y., Wang J., Li W., Wu W., Hong Z., Molecules 2019, 24, 817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schnepel C., Minges H., Frese M., Sewald N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14159–14163; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 14365–14369. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gruß H., Belu C., Bernhard L. M., Merschel A., Sewald N., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 5880–5883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roy A. D., Goss R. J. M., Wagner G. K., Winn M., Chem. Commun. 2008, 4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Müller G., Gurrath M., Kessler H., J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 1994, 8, 709–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haubner R., Gratias R., Diefenbach B., Goodman S. L., Jonczyk A., Kessler H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 7461–7472. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kemker I., Schnepel C., Schröder D. C. C., Marion A., Sewald N., J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 7417–7430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Knop K., Hoogenboom R., Fischer D., Schubert U. S., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6288–6308; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 6430–6452. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parveen S., Sahoo S. K., Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2006, 45, 965–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pallarola D., Bochen A., Boehm H., Rechenmacher F., Sobahi T. R., Spatz J. P., Kessler H., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 943–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bochen A., Marelli U. K., Otto E., Pallarola D., Mas-Moruno C., Di Leva F. S., Boehm H., Spatz J. P., Novellino E., Kessler H., Marinelli L., J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 1509–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Šimeček J., Notni J., Kapp T. G., Kessler H., Wester H.-J., Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 1687–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Indrevoll B., Kindberg G. M., Solbakken M., Bjurgert E., Johansen J. H., Karlsen H., Mendizabal M., Cuthbertson A., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 6190–6193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kapp T. G., Rechenmacher F., Neubauer S., Maltsev O. V., Cavalcanti-Adam E. A., Zarka R., Reuning U., Notni J., Wester H.-J., Mas-Moruno C., Spatz J., Geiger B., Kessler H., Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dee K. C., Puleo D. A., Bizios R., An Introduction to Tissue-Biomaterial Interactions, Wiley, Hoboken, 2002, pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bernhagen D., Jungbluth V., Quilis N. G., Dostalek J., White P. B., Jalink K., Timmerman P., ACS Comb. Sci. 2019, 21, 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Verhoef J. J. F., Anchordoquy T. J., Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2013, 3, 499–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rejman J., Oberle V., Zuhorn I. S., Hoekstra D., Biochem. J. 2004, 377, 159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Armstrong J. K., Wenby R. B., Meiselman H. J., Fisher T. C., Biophys. J. 2004, 87, 4259–4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Azri A., Giamarchi P., Grohens Y., Olier R., Privat M., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 379, 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary