To the editor,

Japanese cedar pollinosis (JCPsis) is a major health problem that has increased over recent decades and impairs daily activities.1 Besides the standard treatments specified in the guidelines,2 some strains of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, have been shown to improve pollinosis symptoms.3, 4 Although LAB are believed to induce regulatory T (Treg) cells, thereby alleviating allergic symptoms,4 whether LAB augment Treg cell abundance, together with clinical symptoms, remains unclear.

Lactobacillus plantarum YIT 0132 (LP0132), derived from fermented food, induces a high level of IL‐10 secretion from murine macrophages.5 Previously, LP0132‐fermented citrus juice, which contained approximately 8.0 × 1010 heat‐killed LP0132 cells/100 mL, showed therapeutic potential to improve JCPsis‐associated symptoms.5 In this trial, we further evaluated the efficacy of this beverage for the treatment of JCPsis, in association with immunological parameters including peripheral Treg cells in the pollen season.

We randomly assigned 100 adults with JCPsis to consume 125 mL of fermented citrus juice containing heat‐killed LP0132 (LP0132, n = 50) or unfermented citrus juice (placebo, n = 50) for 8 weeks from mid‐February to mid‐April 2017, from the beginning to the end of the pollen season (Figure S1). Throughout the trial period, the subjects were asked to avoid taking LAB‐containing food and keep daily records of their consumption of beverages, medications, and medical visits, and to perform a weekly self‐assessment of JCPsis symptoms based on the Japanese Rhino‐conjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire.2 The primary outcome was total symptom score (TSS) in March (predicted peak season). Peripheral blood samples were obtained at enrollment, in late March, and during follow‐up to evaluate the percentage of CD4 + CD25 + Foxp3 + Treg cells. Detailed methods and statistical analyses are described in supporting information. P‐values <.05 were considered statistically significant. The trial protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shimoshizu National Hospital, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN000025924). Written‐informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

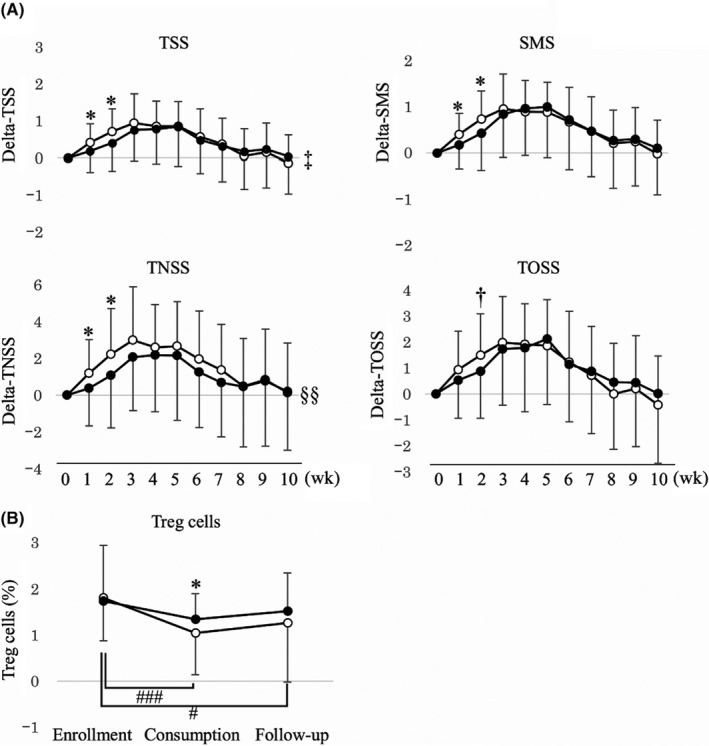

All subjects completed the trial (Figure S2), and no significant adverse events were reported in either group. The baseline characteristics were comparable, except for the higher symptom medication score (SMS) and medication score (MS) in the LP0132 group (Table S1). Average TSS in March (weeks 3‐6) did not differ significantly between both groups; however, the LP0132 group had a significantly lower total nasal symptom score (TNSS) than the placebo group during the entire consumption period (weeks 0‐8), and they had a significantly lower TSS, SMS and TNSS at weeks 1 and 2 compared to the placebo group (Figure 1A). The percentage of Treg cells decreased significantly from enrollment to late March only in the placebo group, and the percentage of Treg cells in late March was significantly higher in the LP0132 group than in the placebo group (Figure 1B). Other immunological parameters did not differ significantly between both groups at each timepoint (Table S2). Although MS in the LP0132 group was significantly higher throughout the consumption period, propensity score matching analysis adjusting for MS from weeks 0 to 10 (36 subjects from each group) was consistent with these results (Figure S3).

Figure 1.

Changes in (A) total symptom score (TSS), symptom medication score (SMS), total nasal symptom score (TNSS), and total ocular symptom score (TOSS), and (B) Treg cells in the trial period. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.  : LP0132,

: LP0132,  : Placebo. *P < .05, †P < .1 compared with the placebo group (Student's t test). ‡P < .1, §§P < .01 compared with the placebo group during the consumption period (weeks 0‐8) (two‐way ANOVA). #P < .025, ###P < .0005 compared with enrollment (paired t test with Bonferroni's correction)

: Placebo. *P < .05, †P < .1 compared with the placebo group (Student's t test). ‡P < .1, §§P < .01 compared with the placebo group during the consumption period (weeks 0‐8) (two‐way ANOVA). #P < .025, ###P < .0005 compared with enrollment (paired t test with Bonferroni's correction)

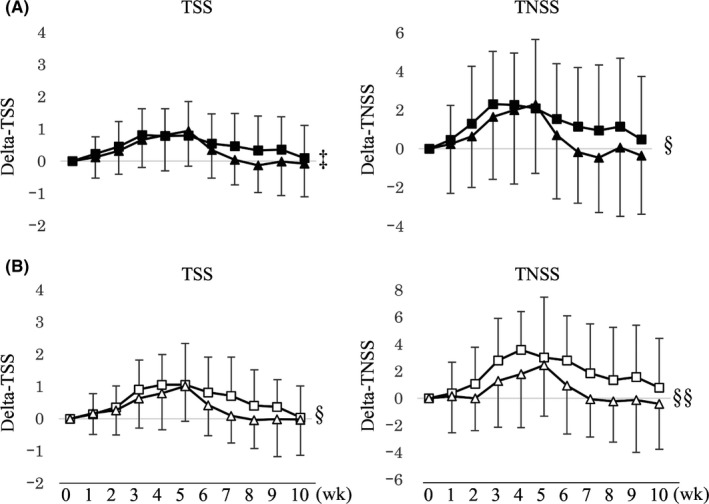

As a predetermined exploratory analysis, based on the changes in the percentage of Treg cells from enrollment to the consumption period, the subjects in the LP0132 group were divided into increased Treg and decreased Treg subgroups to compare the symptom scores. The increased Treg subgroup (n = 17) had a significantly lower TNSS than the decreased Treg subgroup (n = 33) during the consumption period (Figure 2A). Propensity score matching analysis adjusting for MS from weeks 0 to 10 (14 subjects from each subgroup) was consistent with these results (Figure 2B). In contrast, the same analysis in the placebo group did not show a significant difference between the increased Treg (n = 9) and decreased Treg (n = 41) subgroups.

Figure 2.

Changes in total symptom score (TSS) and total nasal symptom score (TNSS) based on increased and decreased Treg abundance between enrollment and the consumption period in the LP0132 group (A)  : increased Treg subgroup (n = 17),

: increased Treg subgroup (n = 17),  : decreased Treg subgroup (n = 33), and after propensity score matching (B)

: decreased Treg subgroup (n = 33), and after propensity score matching (B)  : increased Treg‐matched subgroup (n = 14),

: increased Treg‐matched subgroup (n = 14),  : decreased Treg‐matched subgroup (n = 14). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. ‡P < .1, §P < .05, §§P < .01, compared between subgroups during the consumption period (weeks 0‐8) (two‐way ANOVA)

: decreased Treg‐matched subgroup (n = 14). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. ‡P < .1, §P < .05, §§P < .01, compared between subgroups during the consumption period (weeks 0‐8) (two‐way ANOVA)

Despite the negative result for the primary outcome, this is the first clinical trial to demonstrate the ability of LAB to suppress the reduction in Treg cells in the peak pollen season. In a recent trial, LAB increased the percentage of Treg cells from the baseline, but the changes were not significant compared with placebo.6 Treg cells are reported to be reduced in patients with allergic rhinitis7 and increased by immunotherapy with a clinical response.8 The results of the present study suggest that Treg cells may be reduced with the severity of pollinosis due to exposure to pollen. However, few studies have observed this fluctuation. Thus, further studies are needed to examine whether circulating Treg cells decrease in the pollen season and LAB are capable of inhibiting this seasonal change in Treg cells.

Notably, the increase in Treg cells in the pollen season was associated with milder symptoms in the LP0132 group. LP0132, like other LAB administered for JCPsis,3 alleviated JCPsis symptoms only in the early phase, whereas symptom scores in this phase did not differ between the increased Treg and decreased Treg subgroups in the LP0132 group. From these findings, we speculate that LP0132 may have an immunological effect, other than inducing the expansion of Treg cells, which may contribute to the alleviation of JCPsis symptoms in the early phase.

This study has several limitations. In this trial, the specific subtypes of Treg cells induced by LP0132 to alleviate JCPsis symptoms were not examined. For instance, experiments suggest that CD4 + CD25 + Foxp3 + RORγt + Treg cells induced by intestinal microbiota may suppress Th2 immune responses.9 IL‐10 levels in the blood samples were not measured to validate the LP0132 signature, which we will perform in a future study to further elucidate the mechanism underlying the action of LP0132. Propensity score matching to adjust for MS may have missed unrecognized backgrounds, which could lead to the misinterpretation of our results. However, we did not find any factors that were different between the matched groups.

In summary, citrus juice fermented with LP0132 alleviated JCPsis symptoms in the early season and suppressed reduction in circulating Treg cells in the peak season. The increase in Treg abundance from enrollment was associated with milder JCPsis symptoms.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This trial was conducted based on a collaboration between Yakult Central Institute at Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd. and Shimoshizu National Hospital. NK, SK, KM, and NHM are employees of Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This trial was funded by Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all participants in this trial. We also thank all staff of Shimoshizu National Hospital for clinical support, N. Sahashi of Toho University for providing data on pollen dispersion, T. Uetake and K. Fujiura of CX Wellness Co., Ltd. for support with subject management and data collection, and M. Miyagawa of Takumi Information Technology Corporation, J. Nakayama of LSI Medience Corporation, S. Nakamura of Riken, C. Nonaka, K. Nakamori, and T. Igarashi of Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd., and E. Kotaki of Yakult Central Institute for helpful advice. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors.

Correction added on 04 October 2019, after first online publication on 27 August 2019 : Title and supporting information have been updated in this version

REFERENCES

- 1. Yamada T, Saito H, Fujieda S. Present state of Japanese cedar pollinosis: the national affliction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3): 632–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Okubo K, Kurono Y, Ichimura K, et al. Japanese guidelines for allergic rhinitis 2017. Allergol Int. 2017;66(2):205‐219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Güvenç IA, Muluk NB, Mutlu FŞ, et al. Do probiotics have a role in the treatment of allergic rhinitis? A comprehensive systematic review and meta‐analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2016;30(5):157‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martens K, Pugin B, De Boeck I, et al. Probiotics for the airways: Potential to improve epithelial and immune homeostasis. Allergy. 2018;73(10):1954‐1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harima‐Mizusawa N, Kano M, Nozaki D, Nonaka C, Miyazaki K, Enomoto T. Citrus juice fermented with Lactobacillus plantarum YIT 0132 alleviates symptoms of perennial allergic rhinitis in a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Beneficial Microbes. 2016;7(5):649‐658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dennis‐Wall JC, Culpepper T, Nieves C Jr, et al. Probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri KS‐13, Bifidobacterium bifidum G9–1, and Bifidobacterium longum MM‐2) improve rhinoconjunctivitis‐specific quality of life in individuals with seasonal allergies: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(3):758‐767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Palmer C, Mulligan JK, Smith SE, Atkinson C. The role of regulatory T cells in the regulation of upper airway inflammation. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2017;31(6):345‐351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Varona R, Ramos T, Escribese MM, et al. Persistent regulatory T‐cell response 2 years after 3 years of grass tablet SLIT: Links to reduced eosinophil counts, sIgE levels, and clinical benefit. Allergy. 2019;74(2):349‐360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sefik E, Geva‐Zatorsky N, Oh S, et al. Individual intestinal symbionts induce a distinct population of RORgamma(+) regulatory T cells. Science. 2015;349:993‐997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials