Abstract

This study aimed to explore men’s experiences of social support after non-nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. A qualitative study based on Gadamer’s hermeneutic phenomenology was designed. In-depth interviews were conducted with 16 men who had undergone a non-nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Data analysis was performed using ATLAS.ti software. From this analysis, two main themes emerged: “The partner as a source of support and conflict after a prostatectomy,” which includes empathetic reconnection with the partner and changes in sexual and cohabitation patterns and “The importance of social and professional circles,” which addresses the shortcomings of the healthcare system in terms of sexual information and counseling as well as the role of friends within social support. The study suggests the need to establish interventions that address interpersonal communication and attention to social and informational support and include both the patient and those closest to them.

Keywords: prostate cancer, prostatectomy, sexuality, sexual practice, qualitative research

Prostate cancer is currently the second most prevalent cancer in the world (Ilic et al., 2018) and the most common type of cancer among men in Europe (Ferlay et al., 2013). In Spain, 12% of all cancer cases diagnosed are prostate cancer (Cózar et al., 2013).

The treatment of prostate cancer includes measures to remove or reduce the tumor by ablation (Hatiboglu et al., 2019), radiation (Bolla et al., 2019), or surgical excision (Bill-Axelson et al., 2018). In the case of metastatic prostate cancer, systemic treatment based on chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormonal therapy is prescribed to improve the chances of survival (Gravis, 2019).

Radical prostatectomy (RP) is included among surgical treatments (Bill-Axelson et al., 2018; Morlacco & Karnes, 2016). The surgical technique of choice is nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy (NSRP), which allows for the preservation of the periprostatic nerves (Galfano et al., 2018). This is not always possible due to the size of the tumor, making non-nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy (NNSRP) necessary (Shpot et al., 2018).

NNSRP can have physical consequences for patients, such as male sexual dysfunction (MSD) (Fode et al., 2017; Katz & Dizon, 2016), urinary incontinence (Blomberg et al., 2016), or bowel disorders (Nam et al., 2014). NNSRP has also been linked to erectile dysfunction (Chambers et al., 2017) and orgasmic dysfunction (Fode et al., 2017). In addition, psychological alterations such as inhibited sexual desire (Lehto et al., 2017) and low self-esteem (Li et al., 2014) have been highlighted.

These adverse effects have negative social consequences on patients, which affects cancer survivors and their intimate partners’ quality of life (Ramsey et al., 2013). This lower quality of life and high rate of distress have been associated with decreased male sexual function (Kalmbach et al., 2014). The perception of being looked after, loved, and belonging to a social network is a factor that can alleviate distress (Leahy-Warren, 2014). The distress not only contributes to the patients’ suffering but also to their families, who play a key role in providing care and emotional support to patients (Laidsaar-Powell et al., 2016). The importance of family support in the cancer process has been strongly demonstrated, but often the provision of care is centered only around the patient (Fode et al., 2017). Loss of social support can lead to social isolation and relationship strain, which may have an impact on well-being (Merluzzi et al., 2019).

The framework that guides this study is the social support theory (Leahy-Warren, 2014), a theoretical framework for research on social support. Social support promotes health and well-being and facilitates coping and adaptation strategies when needed (Leahy-Warren, 2014). Social support is conceptualized in terms of structural or functional dimensions. Structural social support is made up of an individual’s social connections. It can be both formal, such as the relationship with healthcare professionals, and informal, in the form of relatives, acquaintances, partners, and friends. From a functional standpoint, social support can be informational, emotional, instrumental, and appraisal (Leahy-Warren, 2014).

Despite sexuality being one of the main unmet demands that concerns patients (Pinks et al., 2018), healthcare professionals (formal structural social support) usually overlook it during treatment (Cousseau et al., 2016; Granero-Molina et al., 2018). Management behaviors for psychological and physical problems (Paterson et al., 2014), as well as decision-making (Laidsaar-Powell et al., 2016) in patients with prostate cancer have been researched. However, there is a lack of research on patients who have undergone a prostatectomy concerning their perceptions of the social support they receive from health care professionals, family, and friends.

Thus, this study aimed to explore men’s experiences regarding social support after non-nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy.

Methods

Design

A qualitative study based on Gadamer’s hermeneutic phenomenology was designed. To Gadamer, human experience can only be understood through language. The understanding of a phenomenon is achieved through a fusion of horizons between the researchers (preunderstanding) and the participants (based on their experiences) (Gadamer, 2013). The development of this study followed the phases of the Gadamerian-based research method (Fleming et al., 2003; Fleming & Rob, 2019) as follows:

Decide if the study question is relevant to the methodological assumptions. The experiences of men who have undergone non-nerve-sparing prostatectomy and perceived social support are phenomena of the life-world, and thus can be understood from the perspective of hermeneutic phenomenology (Fleming & Rob, 2019).

Identify the researchers’ preunderstanding of the topic and how this contributes to the research. Seven researchers participated in the study process, of whom three are clinical researchers (psychologists and nurses) who work in hospital urology units and/or in cooperation with the Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer or AECC (Spanish Association Against Cancer). This facilitated the recruitment of participants and data collection. Four researchers are university professors, specialized in qualitative research methodology, who aided in the analytical process and in the drafting of this article. Three researchers are Spanish natives with clinical, teaching, or research experience in the United Kingdom (bilingual), which aided in the process of revision and translation of the interview transcriptions.

Participants and Setting

This study was carried out at the provincial headquarters of the AECC. The participants were recruited through convenience sampling. The inclusion criteria were: (1) having undergone non-nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy as treatment for prostate cancer, (2) giving consent to participate in the study, and (3) reporting sexual dysfunction after the procedure. The exclusion criteria were: (1) suffering any cognitive impairment that could interfere with understanding and answering questions, and (2) receiving treatment that could interfere with sexual function such as hormonal therapy. The final sample comprised 16 participants from a total of 24 contacted: eight were excluded from the sample as they did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria, two men retained sexual integrity after surgery, one was under hormonal therapy by the time of data collection, and five men reported inadequate sexual function preoperatively. Once the researchers considered data saturation has been reached, data collection ceased. The participants’ average age was 64.2 years old (SD = 4.16), and on average they had had surgery 4.9 years before the study. The participants’ sociodemographic data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Data of the Participants (N = 16).

| Interview | Age | Gender | Sexual orientation | Level of education | Marital status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-01 | 74 | Male | Heterosexual | Basic | Married |

| P-02 | 65 | Male | Heterosexual | No studies | Married |

| P-03 | 60 | Male | Heterosexual | Medium | Married |

| P-04 | 62 | Male | Heterosexual | No studies | In a relationship |

| P-05 | 68 | Male | Heterosexual | Medium | Married |

| P-06 | 60 | Male | Heterosexual | Basic | Married |

| P-07 | 62 | Male | Heterosexual | University graduate | Married |

| P-08 | 64 | Male | Heterosexual | University graduate | In a relationship |

| P-09 | 59 | Male | Heterosexual | University graduate | Married |

| P-10 | 65 | Male | Heterosexual | Medium | In a relationship |

| P-11 | 69 | Male | Heterosexual | Basic | Married |

| P-12 | 63 | Male | Heterosexual | University graduate | In a relationship |

| P-13 | 60 | Male | Heterosexual | Basic | Married |

| P-14 | 71 | Male | Heterosexual | Medium | Married |

| P-15 | 66 | Male | Heterosexual | Basic | In a relationship |

| P-16 | 63 | Male | Heterosexual | University graduate | Married |

Data Collection

Data collection took place between February and December 2017 through 16 in-depth interviews. The psychologist at the AECC headquarters provided information about the users who met the inclusion criteria, and the main researcher contacted the sample via telephone and explained the aim of the study. The patients who met the criteria and gave their written consent to participate were selected to do so. A meeting was then arranged for one of the researchers to perform the individual interviews. The interviewer followed an interview protocol (Table 2), which included the objectives, ethical issues, and a question guide. In order to build trust, the participants were initially asked about the impact of the radical prostatectomy on their quality of life. Questions related to sexuality and social support were only introduced once the researcher perceived that a climate of trust had been achieved. In order to measure this perception, certain factors were taken into account, such as the spontaneity of responses, the length of responses, and nonverbal cues that indicated a relaxed state (smiling and relaxed posture).

Table 2.

Interview Protocol.

| Stages of the interview | Topics | Examples of information or questions |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction and “communicative contract” | My purpose | I form part of a study about the perception of Social Support in patients who have undergone non-nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. I believe this experience could be very useful for other patients and it should become known |

| My intentions | Carry out and publish research that sheds light on this experience | |

| Information and ethical considerations | We will need to record the conversation, which will only be used for the study. There will be total confidentiality. The research team will be the only people who have access to the recordings. Participation is voluntary. We can interrupt or stop the interview at any time. We will not publish any names or other personal data that may reveal your identity | |

| Consent | It is deemed granted if the person agrees verbally and signs the corresponding document | |

| Opening | Introductory questions | Tell me a little bit about yourself: Who are you, when did you have the procedure, how did it go? |

| Development | Social support | In what ways has your daily life changed since you had the procedure? How has the prostatectomy affected the relationships you have with your family and friends? Can you describe your opinion about the support you received from healthcare professionals? (Finish this sentence). Prostatectomy has influenced my life because… What type of advice or support have you received from the people who have treated and taken care of you? Could you tell me what your partner’s role has been in the handling of any sexual problems? |

|

Closing |

Final questions | Do you think we have left out anything important? Would you like to add anything else? |

| Acknowledgments | Thank you for your time. Your statements will be very useful for the research study |

|

| Offer | We are here if you need anything or would like to reach out. When we finish the study, we will send it to you |

The interviews lasted an average of 48 min and were digitally recorded and transcribed. The interviews were then reviewed and integrated with the field notes and interviewer’s comments to make up the hermeneutic unit (or project) to be analyzed using ATLAS.ti software. The interviews were performed in Spanish. To maintain accuracy in data interpretation and avoid losing any richness of expression, the interview transcriptions were translated to English by a bilingual native English speaker, then were translated back into Spanish by a bilingual native Spanish speaker. The retro-translations were compared with the original transcriptions by the two bilingual native Spanish researchers who had clinical experience with these types of patients.

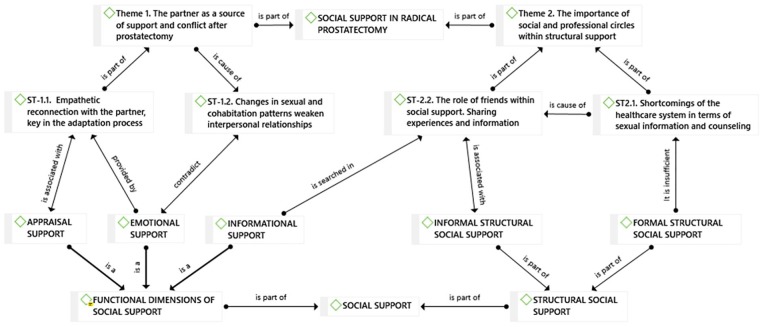

Analysis

Through conversation, a “spontaneous understanding of the phenomenon through dialogue with the participants” comes about (Fleming et al., 2003). The researchers who performed the interviews took notes on ideas that arose and used their preanalytic intuition to adapt the interview protocol to the development of each individual conversation. The next step is to seek understanding through the dialogue with the text. To do so, the researchers analyzed the transcriptions following the stages described by Braun and Clarke (2006): (1) Familiarize yourself with your data: All transcripts were read by all the researchers to gain a general idea of their content. In a second reading, three researchers annotated the initial ideas. (2) Generation of initial codes: Three researchers codified the most interesting characteristics of the data systematically by creating codes and comparing relevant data for each code. The codification was done using the codification tools in ATLAS.ti software (open coding, coding in vivo, and, when a long enough list of codes was created, coding by list). The four remaining researchers analyzed the system of codes and gave their approval or suggested modifications. (3) Search of themes: The codes were grouped into possible themes and all the relevant data were collected for each potential theme, for which the ATLAS.ti “code group” and “working with networks” software tools were used to establish relationships among the codes that composed each subtheme and between subthemes and themes (Figure 1). The seven researchers discussed and approved the grouping of codes into themes. (4) Review of themes: The themes were checked for fit with the codes and data set, generating a conceptual map of the analysis. The conceptual map was created using the tools for working with networks in ATLAS.ti software. The conceptual map shows the relationship between SST concepts and emergent themes. (5) Define and name themes: The analysis continued to refine the details of each theme and the general analytical history. (6) Preparation of the report: Illustrative examples and summaries of the most telling extracts were selected for the research report. The researchers responsible for the analysis selected and proposed the most relevant quotes to be included with each theme and subtheme. The researchers in charge of drafting the results refined the analysis and carried out an additional quote selection. The final analysis of the selected extracts was carried out, once again linking the analysis with the research question and the framework.

Figure 1.

The conceptual map relates social support theory (bottom, in uppercase) to emergent themes of the research (top, in lowercase).

Rigor

Although objectivity is not possible in hermeneutic research, according to Gadamer, one must try to be true to the text and the context (Fleming et al., 2003). In an interpretive paradigm, internal validity refers to the criteria for achieving trustworthiness (Guba & Lincoln, 1989, pp. 301–319).This includes (1) Credibility by choosing interviewers with clinical experience or who know the participants. The researchers who performed the interviews have experience with these types of patients; (2) Transferability by describing the method and sample in detail (see the sections on participants and setting, data collection, and data analysis); and (3) Confirmability or “member checking” (Morse, 2015, p. 1216), for which all the researchers read through the transcriptions to reach agreement about emergent units of meaning, subthemes, and themes. The final list of themes, subthemes, and units of meaning was then shown to the participants for them to confirm that they agreed with the interpretation of their quotes.

Ethical Considerations

All of the participants were informed of the aim of the study and that their participation was voluntary and uncompensated; they all agreed to take part. Participants had the option to leave the interview at any point without having to give a reason or explain why. The authors declare no conflict of interests. The study was approved by the Department of Blinded for review

Findings

From the data analysis, two main themes emerged that illuminate the experiences and expectations of patients with MSD after NNSRP about the social support they receive (Table 3).

Table 3.

Themes, Subthemes and Units of Meaning That Emerged From the Analysis.

| Theme | Subthemes | Units of meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: The partner as a source of support and conflict after prostatectomy | Subtheme 1: Empathetic reconnection with the partner, key in the adaptation process | Support point, partner, partner satisfaction, decision-making, settle debts, complicity, empathy for the other, and intimacy with a partner |

| Subtheme 2: Changes in sexual and cohabitation patterns weaken interpersonal relationships | Lack of communication, deterioration of the relationship, blame the other, fatigue of the role of the caregiver, rejection within the couple, and argument | |

| Theme 2: The importance of the social and professional circle within structural support | Subtheme 1: Shortcomings of the healthcare system in terms of sexual information and counseling | Fear of death, follow-up, information, over-attention, lack of time, demand for information, help, lack of information, doubts. |

| Subtheme 2: The role of friends within social support, sharing experiences, and information | Friendship, poor attendance to group talks, similar cases, age, false beliefs, myths, men in sexological consultation, concerns of the group, and understanding among equals |

Theme 1. The Partner as a Source of Support and Conflict After Prostatectomy

Participants identified their partner (wife or spouse in this study context) as the main provider of care and support during the recovery process after NNSRP. The participants perceived that the support they received had strengthened their relationship with their partner. Perceiving empathy and acceptance (evaluation support) from their partner was fundamental for maintaining a patient’s self-esteem, but at the same time, changes in sexual and cohabitation patterns during the recovery process might have generated feelings of anxiety toward the relationship.

My partner is very important, because if I were under the impression that I was no longer worthy (sexually) or she saw me as useless, my life would lose its meaning. (P.05)

She (my partner) is all I need to feel active again. Everything is the same as before, (although) sometimes its scares me to think things might change. (P.15)

Subtheme 1. Empathetic Reconnection with the Partner: Key to the Adaptation Process

The partner has been identified as the main source of informal social support during recovery, especially in relation to sexuality. When intimate problems regarding such issues as sexuality or sphincter control arose, the partner played a key supporting role when facing physical and emotional distress. It was at those times that the man sensed that his male essence and masculinity were compromised (in danger) and he did not feel capable of responding in the way he thought to be expected of him, that his partner’s understanding was most greatly appreciated. Their partners’ support generated a movement of mutual empathy within the couple, which researchers have called “empathetic reconnection.” This means that the disease and treatment actually give couples an opportunity to strengthen or restore their bond. Achieving approval from others is one of the functions of social support (appraisal support).

The fact that she is always aware of how I feel, how everything is going, is something without which it would be impossible to get up every day. It is my daily objective, that they (my relatives) see me as useful. (P.07)

In practice, we can also observe the other side of this issue, when perceived empathy and support could provoke feelings in some participants of being indebted to their partner. Thus, they tried to “settle that debt” by satisfying their partner in other ways, such as small changes in habits. In a social context where the man traditionally goes out without his wife to do his hobbies (going out with friends …), not going out alone was interpreted as making an “effort” to “give her more attention,” based on the care they have received from her:

I read the newspaper many mornings because my wife brings it to me. When I feel well enough, I go out because my wife pushes me to, but how could I go out for a drink without her like I used to? (P.14)

Some of the participants describe how such support had served as a wake-up call for them in their relationship. Recovery was given the highest priority, ahead of other issues that might have caused friction or arguments, to the point that supports during recovery and having the disease may actually have created a new opportunity in the relationship:

This has gotten us out of our daily routine and has made us forget about other problems. She helps me and I also try to make her feel better. (P.06)

Subtheme 2. Changes in Sexual and Cohabitation Patterns Weaken Interpersonal Relationships

This subtheme represents how, despite the strengthening of relationships described in Subtheme 1, changes in sexual and cohabitation patterns can challenge interpersonal relationships. For example, participants feared that the increased burden and responsibility that fell on their partner would end up causing their interpersonal relationships to deteriorate.

Since I had surgery, she’s been acting strange because I’m sure she’s tired of me doing nothing and her doing everything … […] and me sitting there all day saying, “Bring me this, bring me that.” (P.04)

As the feeling of sexual incapacity that some participants experienced hovered over the entire relationship, becoming an obstacle to open communication, any conversation about sexuality was avoided, which sometimes could lead to conflict, as some participants informed us:

When she asks me questions about “how I feel” … I always avoid them and I say that I don’t feel like talking, that I am not in the mood. (P.16)

In other instances, the men were more susceptible, and normal comments in any typical argument were misinterpreted as insinuations about their ability to perform sexually.

Although we argue about something else, she will end up saying that I’m just more on edge because of my illness and that she can’t do anything about it. Sometimes I think that, deep down, my problems are just “floating” there, that they are always there, and she just reminds me of them. Later, I think that I’m just more susceptible and I shouldn’t have interpreted it that way. (P.08)

A decrease in working time and social relationships outside the family meant more time spent at home as a couple, which sometimes increased tension, arguments, and disagreements.

Before, I was outside the house all day working (…) and when I arrived home I almost always went directly to sleep. But now we spend more time together and we fight and argue more than before. (P.04)

Some participants reported that after surgery, they lost their sexual prowess. They compared themselves with their condition before the disease and became aware of the deterioration in their sexual function, which in turn caused a loss of self-esteem and self-blame. Sometimes their partner might have shown attitudes of rejection or condescension that generated negative feelings.

When we make love I get irritated with myself. I am not like I was before (…) This is very depressing, I am not what I once was. I like to think “it must just be age.” (P.10)

Theme 2. The Importance of Social and Professional Circles Within Structural Support

In dealing with healthcare professionals, participants perceived a lack of individualization in care. They attributed it to the lack of time allotted for consultations and doctors’ poor training in addressing nonclinical issues. Some participants suggested that healthcare professionals should focus more on less clinical subjects, such as intimacy, and provide information in simpler language:

When he (the doctor) finishes talking (. . .), sometimes I haven’t understood a thing” (P.15)

Faced with this deficit in formal structural social support, having a close-knit circle of friends and family (informal social support) gave participants the opportunity to discuss their most intimate concerns. However, this could give rise to false beliefs and generate confusion:

Sometimes I don’t feel like leaving the house. Everybody tells me what I should do, and each one has their own different opinion. (P.12)

Subtheme 1. Shortcomings of the Healthcare System in Terms of Sexual Information and Counseling

From the beginning of the illness process, having a relationship with healthcare professionals was described as essential for the participants. In addition to providing medical treatment, healthcare professionals provide information about potential side effects in areas of daily life. However, participants pointed out that on issues such as sexuality or incontinence, they did not receive all the information they needed. This lack of information might have been due to patients’ attitudes of mistrust; fearful that professionals will misinterpret their interest in sexuality, they avoided asking questions about how the procedure would affect their sexual function. One participant explained it in this way:

What am I going to say to him, at my age, that it’s just stopped working? Then they talk to each other and say, “Look at him, with all he is going through …and he is thinking about sex!” (P.02)

On other occasions, when they dared to raise their sexual concerns, they did not receive an adequate response from the professionals, who tried to minimize the problem or deemed it a “normal” side effect of the intervention.

I asked them if there was any solution to address this in a more or less normal way, but they did nothing but interrupt me and tell me that it was normal. They would not even let me explain. (P.13)

Some participants felt that they did not receive enough information about the consequences a prostatectomy would have on sexual function. This lack of information could have led to hasty decision-making, which might have had different results if the patients had had more extensive knowledge of all its effects.

Maybe if they had explained to me how everything would be, things would have been different, because I was not told that post-surgery was so aggressive. […] Anyway, if I had been told everything, I might not have chosen to undergo surgery. (P.06)

According to the participants, sometimes the healthcare professionals focused on clinical issues, tumor evolution, markers, analyses, etc., and forgot about other issues that affect the quality of life of the patient, such as incontinence or sexuality.

At first I was told about impotence and about the diapers at the same time, but after that, they paid little attention. They see that everything is going well on the computers and little else. (P.03)

Other participants were in favor of organizing informative group sessions from the healthcare system, such as talks or support groups, where they could share experiences, receive information, or get advice on how to improve their quality of life and sexuality.

I think that if talks were held … we would definitely all sign up! People would go because this leads to many problems that change you but nobody brings them up. (P.01)

The participants pointed out that they felt well-treated by urologists. They described the treatment they received as characterized by “tact” and delicacy when addressing any issues related to sexuality. However, at the same time, they also felt that the conditions where the consultation takes place (including the physical conditions) were not suitable for talking about such intimate issues.

The doctor’s office is connected to an examination room, where a nurse and urologist usually are, and someone can come in at any time to deliver the results of an analysis or a medical record. It is not a sexology consultation, and not an appropriate place to calmly discuss sexual issues. (P.09)

Subtheme 2. The Role of Friends Within Social Support: Sharing Experiences and Information

A patient’s circle of friends was another source of social support. In some ways, the lack of information and formal support from healthcare professionals was supplemented by that provided by the people closest to patients. It was among friends and other patients that the participants felt comfortable enough to raise their most intimate concerns, even before seeking help from their partner.

There, we do not hide anything, we tell each other, “This happens to me when I go to the bathroom, to me, this other thing happens in bed…,” things that I am even ashamed to tell my wife or even the doctor. (P.01)

The reason why the participants felt comfortable sharing such intimate topics in this circle was an understanding among equals. The interviewees mentioned that they were more comfortable talking with people who were going through or had gone through the same situation:

Lately, when I go out for a drink with friends, I spend all my time talking to X. (…) Since the same thing is happening to both of us, we are not ashamed to talk about everything. And it’s good for us to talk about it among ourselves. (P.07)

Due to the insufficient information received from the professionals, the participants stated that they sought to satisfy their need for information from their social circle. Although these conversations among peers aimed to supply formal/professional information, myths and false beliefs related to sexuality were sometimes transmitted and perpetuated.

The thing is, I do not want to touch myself (masturbate) or anything like that … I barely touch myself because I’m afraid. I have been told that it is bad for the prostate and that’s what’s important. (P.01)

Not all participants shared their concerns with their circle of friends. Some claimed not to have enough physical strength or energy to leave home. In contrast, others adopted a proactive role to improve their mood and maintain physical activity and social relationships.

[Some patients] told me, “Look at what life has thrown at us! At this age, when we could be relaxing! “ And I say, “Let’s see, we can continue to relax, but if we take things that way… you are not comfortable with yourself anymore, nor those around you.” […] I encourage those who are by my side, because you have to get out and move! (P.13)

In a pragmatic analysis, the emergent themes were related to the concepts of SST (theoretical preunderstanding). The concept map (Figure 1) shows that appraisal and emotional support are functional dimensions of social support provided by the partner, who is the main source of support in sexual issues after a prostatectomy. Informational support is provided insufficiently and inadequately by formal support systems (healthcare providers) and by informal social support systems (friends and other patients), to which participants turned to share their experiences and get information.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore men’s experiences of social support after non-nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Interpersonal relationships were analyzed, considering social support as a fundamental factor in quality of life (Leahy-Warren, 2014). In line with the findings of the literature to date (Fode et al., 2017), participants expressed their dissatisfaction with the deterioration of their health in certain dimensions, emphasizing such aspects as alterations of sexuality (Katz & Dizon, 2016) or urinary incontinence (Blomberg et al., 2016).

It has been shown that patients who maintain a romantic relationship have lower levels of anxiety and depression than single people (Mata et al., 2015). The family is an important source of support in the recovery process (Laidsaar-Powell et al., 2017) and in the decision-making process throughout the disease (Laidsaar-Powell et al., 2016).

NNSRP can cause psychological and emotional alterations that compromise the patient’s adaptation to the new situation (Lehto et al., 2017), which can affect their immediate environment, particularly their partner (Paterson et al., 2015). Other studies suggest that these emotional conflicts after NNSRP can culminate in an inability to maintain satisfactory intimate relationships (Chambers et al., 2013; Pinks et al., 2018). These sexual issues can cause negative feelings in the recovery phase (Lambert et al., 2016) that affect relationship satisfaction (Manne et al., 2011). As possible triggering factors of these problems, some authors have indicated alterations in self-concept and self-image (Wittmann et al., 2015). In contrast, this study suggests that the support received from a partner can improve the relationship and bring about changes in the patient’s behavior, usually based on appreciation for their partner’s help. For example, one participant reported having given up certain hobbies, such as going out with his friends without his partner, as an act of appreciation toward her for the care and treatment she gave him. In this study, the partner emerged as a key element in the appraisal and emotional dimensions of social support. As noted in other studies (Jordan et al., 2015; Wittmann et al., 2015), a couple’s bonds can be strengthened through vulnerability and caring for one of them. Nevertheless, the participants also reported that sometimes their relationship with their partner became conflicted and actually debilitated. This is due to the complexity of relationships, especially those in which both members are subject to tiredness and feelings of frustration. This two-sided movement (strengthening and weakening of the bond) fluctuates, as relationship dynamics are defined by many different factors, such as mood and a patient’s prognosis.

The noninclusion of the partner in sexual function recovery therapy has also been suggested as a possible cause of conflict (McCorkle et al., 2007), which was also the case in our study, since, as previously described, the partner is a key agent in the recovery process (Laidsaar-Powell et al., 2016). As in other studies (Granero-Molina et al., 2018), participants perceive little formal social support from healthcare professionals. This study reports that patients receive limited informational support, especially on topics such as sexuality and other intimate issues such as incontinence. The importance of explaining professional information in lay terms has also been highlighted (McCaughan et al., 2015), but participants in this study reported that they received information inappropriately, sometimes too extensively or in too complex a form. Participants also pointed to health professionals’ lack of knowledge when implementing psychosocial interventions (Parahoo et al., 2017) and the lack of time allotted for consultations (East & Hutchinson, 2013) as causes of poor formal support. This study suggests that the patient’s attitude (feeling embarrassed or afraid to bring up questions about intimate subjects) is also a barrier to the informational dimension of structural social support. Participants also perceive an avoidance of sexuality by the people in charge of formal support, which has been previously described (Arikan et al., 2015). To modify this dynamic and offer holistic care to the patient undergoing NNSRP, psychological and sexual counseling has been suggested as a potential alternative (Chung & Brock, 2013). Although the benefits of sexual counseling for patients with chronic diseases that affect sexuality (formal support) have been shown (Matarín-Jiménez et al., 2017), our study emphasizes the partner as a source of social support (informal support). The use of telephone-based interventions has been suggested to improve access to professionals who can provide help (Liptrott et al., 2018).

To supplement the information deficit provided by formal support systems (healthcare professionals), the participants rely on their close circle of friends and family. This can contribute to the emergence of myths and false beliefs (East Treena, 2014; Gilbert et al., 2013). Regarding the social circle, the results of this study are in line with those of other studies (Hyde et al., 2017; King et al., 2015; Kirkman et al., 2017) that indicate that men value the support of their peers as well as the support of their partners. The establishment of support groups in other countries has been proposed as a model for programs for prostate cancer patients (Roth et al., 2008). This study suggests that it is preferable to address intimacy and relationship issues in an environment of trust among people who have gone through the same process.

Limitations

Talking about sexuality and recognizing one’s own sexual limitations can cause feelings of shame and embarrassment, so some participants might not have been totally honest about the state of their sexual function. To limit this effect, long interviews were held in which the issue of sexuality was addressed only when the interviewer perceived that a “climate of trust” was established with the participant. As this study included a sample of heterosexual patients, this would reduce the generalizability of the results to homosexual patients; thus, interviewing men with a different sexual orientation could have enriched the results.

In this study, only patients who have been affected by NNSRP were interviewed. Interviewing their partners or families and friends (support networks) would have given us a more in-depth understanding of their social support.

Conclusions

The partner constitutes the main source of social support after NNSRP. Feeling cared for and understood helps the patient to empathize with the caregiver and reward them in some way. Changes in sexual patterns and cohabitation after undergoing NNSRP can put intimate relationships at risk, which may generate distress in the patient. This relationship dynamic (strengthening and weakening of the couple’s bond) can fluctuate with time, depending on several factors such as mood and prognosis.

Participants have identified shortcomings in the formal support system (healthcare professionals), which overlooks or underemphasizes the importance of issues related to intimacy and sexuality. Patients demand more personal treatment from health professionals focusing on men’s needs. Patients’ friends and peers (other patients) constitute a solid support system, where patients share experiences and obtain support and information that at times may be erroneous. Incorrect or erroneous information does not help in the sexual recovery process and can increase emotional stress and affect men’s sexual health.

Implications for Clinical Practice and Research

This study suggests a need for establishing holistic therapies that include better interpersonal communication, a focus on postsurgical intimacy, and informational support that involves the patient and their immediate environment. After undergoing prostatectomy, men may feel ashamed or insecure, which acts as a barrier to asking about male intimacy issues. Trained professionals should address these intimate topics in order to help patients overcome their resistance to discuss them. It could also be beneficial to include the partner in all stages of the recovery process, as well as to explore and evaluate the creation of support groups and therapy led by specialized personnel (e.g., sexologists and continence specialist nurses) in order to surmount this communication barrier.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants who took part in this study. The Health Sciences Research Group (CTS-451) and the Centro de Investigación en Salud (CEINSA) (Health Research Center) of the University of Almeria funded this research. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Cayetano Fernandez-Sola  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1721-0947

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1721-0947

José Granero-Molina  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7051-2584

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7051-2584

References

- Arikan F., Meydanlioglu A., Ozcan K., Canli Ozer Z. (2015). Attitudes and beliefs of nurses regarding discussion of sexual concerns of patients during hospitalization. Sexuality and Disability, 33(3), 327–337. [Google Scholar]

- Bill-Axelson A., Holmberg L., Garmo H., Taari K., Busch C., Nordling S., Häggman M., Andersson S. O., Andrén O., Steineck G., Adami H. O., Johansson J.-E. (2018). Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in prostate cancer — 29-year follow-up. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(24), 2319–2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg K., Wengström Y., Sundberg K., Browall M., Isaksson A. K., Nyman M. H., Langius-Eklöf A. (2016). Symptoms and self-care strategies during and six months after radiotherapy for prostate cancer - Scoping the perspectives of patients, professionals and literature. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 21(C), 139–145. 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolla M., Henry A., Mason M., Wiegel T. (2019). The role of radiotherapy in localised and locally advanced prostate cancer. Asian Journal of Urology, 6(2), 153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers S. K., Chung E., Wittert G., Hyde M. K. (2017). Erectile dysfunction, masculinity, and psychosocial outcomes: A review of the experiences of men after prostate cancer treatment. Translational Andrology and Urology, 6(1), 60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers S. K., Schover L., Nielsen L., Halford K., Clutton S., Gardiner R. A., Dunn J., Occhipinti S. (2013). Couple distress after localised prostate cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(11), 2967–2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung E., Brock G. (2013). Sexual rehabilitation and cancer survivorship: A state of art review of current literature and management strategies in male sexual dysfunction among prostate cancer survivors. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(SUPPL.), 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousseau L., Freyens A., Corman A., Escourrou B. (2016). From representation to resistances of general practitioners to approach the sexuality with elderly patients. Sexologies, 25(2), 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cózar J. M., Miñana B., Gómez-Veiga F., Rodríguez-Antolín A., Villavicencio H., Cantalapiedra A., Pedrosa E. (2013). Registro nacional de cáncer de próstata 2010 en España. Actas Urologicas Españolas, 37(1), 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East Treena L. (2014). Somebody else’s job: Experiences of sex education among health professionals, parents and adolescents with physical disabilities in Southwestern Ontario. Sexuality & Disability, 32(3), 335–350. [Google Scholar]

- East L., Hutchinson M. (2013). Moving beyond the therapeutic relationship: A selective review of intimacy in the sexual health encounter in nursing practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(23–24), 3568–3576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J., Steliarova-Foucher E., Lortet-Tieulent J., Rosso S., Coebergh J. W. W., Comber H., Forman D., Bray F. (2013). Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries in 2012. European Journal of Cancer, 49(6), 1374–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming V., Robb Y. (2019). A critical analysis of articles using a Gadamerian based research method. Nursing Inquiry, 26(2), e12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming V., Gaidys U., Robb Y. (2003). Hermeneutic research in nursing: Developing a Gadamerian-based research method. Nursing Inquiry, 10(2), 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fode M., Serefoglu E. C., Albersen M., Sonksen J. (2017). Sexuality following radical prostatectomy: Is restoration of erectile function enough? Sexual Medicine Reviews, 5(1), 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer H. G. (2013) Truth and method. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Galfano A., Secco S., Panarello D., Di Trapani D., Strada E., Petralia G., Bocciardi A. M. (2018). Radical prostatectomy through the posterior technique. In: John H., Wiklund P. (Eds.), Robotic urology (pp. 401–410). Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert E., Ussher J. M., Perz J., Gilbert E., Ussher J. M., Perz J. (2013). Embodying Sexual subjectivity after Cancer: A qualitative study of people with cancer and intimate partners. Psychology & Health, 28(6), 603–619. 10.1080/08870446.2012.737466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granero-Molina J., Matarin Jimenez T. M., Ramos Rodriguez C., Hernandez-Padilla J. M., Castro-Sanchez A. M., Fernandez-Sola C. (2018). Social support for female sexual dysfunction in fibromyalgia. Clinical Nursing Research, 27(3), 296–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravis G. (2019). Systemic treatment for metastatic prostate cancer. Asian Journal of Urology, 6(2), 162–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guba E., Lincoln Y. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hatiboglu G., Popeneciu V., Bonekamp D., Burtnyk M., Staruch R., Pahernik S., Tosev G., Radtke J. P., Motsch J., Schlemmer H. P., Hohenfellner M., Nyarangi-Dix J. N., Nyarangi-Dix J. N. (2020). Magnetic resonance imaging-guided transurethral ultrasound ablation of prostate tissue in patients with localized prostate cancer: Single-center evaluation of 6-month treatment safety and functional outcomes of intensified treatment parameters. World Journal of Urology, 38(2), 343–350. 10.1007/s00345-019-02784-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde M. K., Newton R. U., Galvao D. A., Gardiner R. A., Occhipinti S., Lowe A., Wittert G. A., Chambers S. K. (2017). Men’s help-seeking in the first year after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 26(2), e12497 10.1111/ecc.12497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic D., Djulbegovic M., Jung J. H., Hwang E. C., Zhou Q., Cleves A., Dahm P. (2018). Prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 362, k3519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan T., Ernst R., Hatzichristodoulou G., Dinkel A., Klorek T., Beyrle C., Gschwend J. E., Herkommer K. (2015). Sexuality of couples 5 years after radical prostatectomy. Sexuality of patients and their partners 1 year postoperatively in sexually active couples. Urologe, 54(10), 1407–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmbach D. A., Kingsberg S. A., Ciesla J. A. (2014). How changes in depression and anxiety symptoms correspond to variations in female sexual response in a nonclinical sample of young women: A daily diary study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(12), 2915–2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz A., Dizon D. S. (2016). Sexuality after cancer: A model for male survivors. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(1), 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. J. L., Evans M., Moore T. H. M., Paterson C., Sharp D., Persad R., Huntley A. L. (2015). Prostate cancer and supportive care: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis of men’s experiences and unmet needs. European Journal of Cancer Care, 24(5), 618–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman M., Young K., Evans S., Millar J., Fisher J., Mazza D., Ruseckaite R. (2017). Men’s perceptions of prostate cancer diagnosis and care: Insights from qualitative interviews in Victoria, Australia. BMC Cancer, 17(1), 704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidsaar-Powell R., Butow P., Bu S., Charles C., Gafni A., Fisher A., Juraskova I. (2016). Family involvement in cancer treatment decision-making: A qualitative study of patient, family, and clinician attitudes and experiences. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(7), 1146–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidsaar-Powell R., Butow P., Bu S., Fisher A., Juraskova I. (2017). Oncologists’ and oncology nurses’ attitudes and practices towards family involvement in cancer consultations. European Journal of Cancer Care, 26(1), e12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S. D., McElduff P., Girgis A., Levesque J. V, Regan T. W., Turner J., Candler H., Mihalopoulos C., Shih S. T. F., Kayser K., Chong P. (2016). A pilot, multisite, randomized controlled trial of a self-directed coping skills training intervention for couples facing prostate cancer: Accrual, retention, and data collection issues. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(2), 711–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy-Warren P. (2014). Social support theory. In: Fitzpatrick J. J., McCarthy G. (Eds.), Theories guiding nursing research and practice: Making nursing knowledge development explicit. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lehto U.-S., Tenhola H., Taari K., Aromaa A. (2017). Patients’ perceptions of the negative effects following different prostate cancer treatments and the impact on psychological well-being: A nationwide survey. British Journal of Cancer, 116(7), 864–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. C., Rew L., Chen L. (2014). Factors affecting sexual function: A comparison between women with gynecological or rectal cancer and healthy controls. Nursing & Health Sciences, 17(1), 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptrott S., Bee P., Lovell K. (2018). Acceptability of telephone support as perceived by patients with cancer: A systematic review. European Journal of Cancer Care, 27(1), e12643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata, L. R. F. da, Carvalho, E. C. de, Gomes, C. R. G., Silva, A. C. da, & Pereira, M. da G. (2015). Postoperative self-efficacy and psychological morbidity in radical prostatectomy. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 23(5), 806–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarín Jiménez T. M., Fernández-Sola C., Hernández-Padilla J. M., Correa Casado M., Antequera Raynal L. H., Granero-Molina J. (2017). Perceptions about the sexuality of women with fibromyalgia syndrome: A phenomenological study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(7), 1646–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaughan E., McKenna S., McSorley O., Parahoo K. (2015). The experience and perceptions of men with prostate cancer and their partners of the CONNECT psychosocial intervention: A qualitative exploration. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(8), 1871–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCorkle R., Siefert M. L., Dowd M. F. E., Robinson J. P., Pickett M. (2007). Effects of advanced practice nursing on patient and spouse depressive symptoms, sexual function, and marital interaction after radical prostatectomy. Urologic Nursing, 27(1), 65–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merluzzi T. V., Serpentini S., Philip E. J., Yang M., Salamanca-Balen N., Heitzmann Ruhf C. A., Catarinella A. (2019). Social relationship coping efficacy: A new construct in understanding social support and close personal relationships in persons with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 28(1), 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlacco A., Karnes R. J. (2016). High-risk prostate cancer: The role of surgical management. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 102, 135–143. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. M. (2015) Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam R. K., Cheung P., Herschorn S., Saskin R., Su J., Klotz L. H., Chang M., Kulkarni G. S., Lee Y., Kodama R. T., Narod S. A. (2014). Incidence of complications other than urinary incontinence or erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: A population-based cohort study. The Lancet. Oncology, 15(2), 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parahoo K., McKenna S., Prue G., McSorley O., McCaughan E. (2017). Facilitators’ delivery of a psychosocial intervention in a controlled trial for men with prostate cancer and their partners: A process evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(7), 1620–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson C., Jones M., Rattray J., Lauder W. (2014). Identifying the self-management behaviours performed by prostate cancer survivors: A systematic review of the evidence. Journal of Research in Nursing, 20(2), 96–111. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson C., Robertson A., Smith A., Nabi G. (2015). Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: A systematic review. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19(4), 405–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinks D., Psych B., Davis C., Pinks C. (2018). Experiences of partners of prostate cancer survivors : A qualitative study. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 36(1), 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey S. D., Zeliadt S. B., Blough D. K., Moinpour C. M., Hall I. J., Smith J. L., Ekwueme D. U., Fedorenko C. R., Fairweather M. E., Koepl L. M., Thompson I. M., Keane T. E., Penson D. F. (2013). Impact of prostate cancer on sexual relationships: A longitudinal perspective on intimate partners’ experiences. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(12), 3135–3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A.J., Weinberger M. I., Nelson C. J. (2008). Prostate cancer: Quality of life, psychosocial implications and treatment choices. Future Oncology, 4(4), 561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpot E. V., Chinenov D. V., Amosov A. V., Chernov Y. N., Yurova M. V., Lerner Y. V. (2018). Erectile dysfunction associated with radical prostatectomy: Appropriateness and methods to preserve potency. Urologiia, 2018(2), 75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann D., Carolan M., Given B., Skolarus T. A., Crossley H., An L., Palapattu G., Clark P., Montie J. E. (2015). What couples say about their recovery of sexual intimacy after prostatectomy: Toward the development of a conceptual model of couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate Cancer. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(2), 494–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]