Summary

The present study focuses on the Belgian Milk Sheep in Flanders (Belgium) and compares its genetic diversity and relationship with the Flemish Sheep, the Friesian Milk Sheep, the French Lacaune dairy sheep and other Northern European breeds. For this study, 94 Belgian Milk Sheep, 23 Flemish Sheep and 22 Friesian Milk Sheep were genotyped with the OvineSNP50 array. In addition, 29 unregistered animals phenotypically similar to Belgian Milk Sheep were genotyped using the 15K ISGC chip. Both Belgian and Friesian Milk Sheep as well as the East Friesian Sheep were found to be less diverse than the other seven breeds included in this study. Genomic inbreeding coefficients based on runs of homozygosity (ROH) were estimated at 14.5, 12.4 and 10.2% for Belgian Milk Sheep, Flemish Sheep and Friesian Milk Sheep respectively. Out of 29 unregistered Belgian Milk Sheep, 28 mapped in the registered Belgian Milk Sheep population. Ancestry analysis, PCA and F ST calculations showed that Belgian Milk Sheep are more related to Friesian Milk Sheep than to Flemish Sheep, which was contrary to the breeders' expectations. Consequently, breeders may prefer to crossbreed Belgian Milk Sheep with Friesian sheep populations (Friesian Milk Sheep or East Friesian Sheep) in order to increase diversity. This research underlines the usefulness of SNP chip genotyping and ROH analyses for monitoring genetic diversity and studying genetic links in small livestock populations, profiting from internationally available genotypes. As assessment of genetic diversity is vital for long‐term breed survival, these results will aid flockbooks to preserve genetic diversity.

Keywords: admixture, effective population size, Flemish Sheep, Friesian Milk Sheep, inbreeding, ROH, runs of homozygosity, Sheep HapMap, single nucleotide polymorphism

Introduction

The Belgian national sheep population comprises 14 local breeds. One of the less numerous breeds is the Belgian Milk Sheep (BMS) (Belgisch Melkschaap/ Mouton Laitier Belge) with a population of fewer than 500 registered animals. The BMS belongs together with Dutch Zealand sheep, Dutch Friesian Milk Sheep (FMS) and German East Friesian Sheep to the Marsh group of the north‐western seaboard of Europe. Their most distinctive features are a long hairless thin tail (‘rat tail’) and a high milk production. Registration of BMS in Flanders is performed by the flockbook Kleine Herkauwers Vlaanderen (KHV), having about 20 registered breeders. Breeders assume that the BMS descends from the Flemish Sheep (FLS), although Porter et al. (2016) report that FLS originated in the nineteenth century by crossing English Lincolnshire sheep into marshland sheep, the ancestors of BMS, FMS and East Friesian Sheep.

Dumasy et al. (2012) report some degree of crossbreeding between BMS and Friesian populations (Dutch and German) using microsatellite data. Meadows et al. (2006) studied Y‐chromosomal oY1.1 alleles in different sheep breeds and reported that East Friesian sheep have together with the Dutch, Mediterranean, Asian and African breeds the ancestral A allele, whereas several English breeds have the derived G allele. The oY1.1 status of BMS, FLS and FMS is unknown. BMS was listed as endangered by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2007 (FAO, 2007) and the BMS flockbook has raised interest in monitoring the population's genetic diversity. Although to date no adverse inbreeding effects such as recessive genetic disorders have been observed, breeders are wary of inbreeding depression and are concerned about the limited active population size.

The state‐of‐the‐art methodology of genetic diversity assessment using genotypes is by the identification of runs of homozygosity (ROH) (Peripolli et al., 2017). ROH are defined as long, continuous homozygous stretches and are assumed to originate from the same ancestor. Long ROH are indicators of recent consanguinity, whereas short ROH may reflect an older bottleneck. In livestock genetics, ROH are now frequently used for inbreeding detection (e.g. Purfield et al., 2012; Marras et al., 2015; Mastrangelo et al., 2018) and for characterizing the genomic distribution of inbreeding depression (e.g. Pryce et al., 2014).

The first objective of the present study is to characterize the genetic diversity and inbreeding levels in BMS using pedigree and genomic information and to compare this with FLS and FMS populations. Additionally, the inclusion of unregistered BMS is evaluated. As a second objective, these three populations are compared with other European dairy and/or thin‐tailed breeds (Kijas et al., 2012) to evaluate their relationship. Eventually, the newly acquired knowledge will guide the conservation and breeding management of BMS.

Material and methods

Animal sampling and genotyping

Blood samples from 285 BMS, 112 FLS and three FMS born between 2006 and 2016 were provided by the flockbook organizations KHV and Steunpunt Levend Erfgoed. A total of 19 FMS DNA samples of unrelated animals born between 2007 and 2016 were provided by the GD Animal Health, Deventer, the Netherlands. A representative set of unrelated BMS and FLS was selected for genotyping. This was achieved by excluding full sibs, by selecting only a limited number of half‐sibs and by including animals with uncommon sires. The number of selected samples per breeder was chosen to be proportional to their flock size. Ninety‐four BMS, 23 FLS and all 22 FMS were selected for genotyping on the Illumina OvineSNP50 beadchip. Additionally, 29 unregistered BMS were genotyped on the 15K ISGC chip (Ventura et al., 2015). Pedigree records on 8284 BMS, born between 1980 and 2016, were obtained from the flockbook organization KHV.

For comparison, we included previously published genotypes from East Friesian Sheep (East Friesian White, EFW, n = 9, and East Friesian Brown, EFB, n = 39), which are similar to BMS and FLS, from the French dairy Lacaune population (LAC, n = 103) and from other thin‐tailed breeds: the Finnish sheep (FIN, n = 99) and the Norwegian Spael (Colored Spael, CSP, n = 3, White Spael, WSP, n = 32, and Old Norwegian Spael, ONS, n = 15; Kijas et al., 2012).

Genotype quality control

Quality control was performed using plink version 1.9 (Chang et al., 2015). SNPs on sex chromosomes, lacking genomic location or with a low call rate (<95%) were removed (Table S1). None of the animals had a call rate below 90% or an outlying heterozygosity rate (>3 SD).

Genetic diversity assessment

Pedigree analysis in BMS was performed using r and poprep (Groeneveld et al., 2009). Pedigree‐based inbreeding coefficients (F ped) were calculated using the Pedigree r‐package (Coster, 2011). The equivalent of complete generations was defined as the sum over all generations and was calculated using the OptiSel r‐package (Wellmann, 2018).

Effective population size (N e) in BMS was estimated based on LD, using the method implemented by François et al. (2017), following Weir & Hill (1980) and Waples (1991, 2006).

Average homozygosity per population was calculated using plink (‐‐het flag). ROH were detected using plink, with a sliding window of 50 SNPs and a scanning window hit rate (threshold) of 0.05. Only one missing SNP was permitted and no heterozygous SNPs were allowed. The maximum gap between consecutive homozygous SNPs was set to 200 kb, and the minimal average SNP density in a ROH was above 1 SNP/ 250 kb. The minimum number of SNPs (l) was calculated as (Purfield et al., 2012):

where n s is the number of genotyped SNPs, n i the number of genotyped individuals, α the percentage of false‐positive ROH (0.05) and het the mean heterozygosity across all SNPs. The value of l was 50 for BMS, 43 for FLS and 46 for FMS. The minimal ROH length setting was 1 Mb.

However, due to the stringency of the other settings, the shortest detected ROH had a length of 2 Mb.

The inbreeding coefficient based on ROH (F ROH), was calculated as:

where L ROH is the total length of all ROH (>2 Mb) in the individual's genome and L aut is the length of the genome covered in the ROH analysis (2633 Mb). This genome coverage was calculated by performing an ROH analysis on an artificial, completely homozygous genotype.

F ROH>5Mb and F ROH>16 Mb were calculated similarly to F ROH, but L ROH was equal to the sum of all ROH segments >5 and >16 Mb respectively. Assuming 1 cM per Mb, the length of an ROH follows on average an exponential distribution described by 100/(2g) where g is the number of generations from the common ancestor (Curik et al., 2014). Thus, F ROH>5Mb and F ROH>16 Mb estimate inbreeding that has occurred up to 10 and up to three generations ago respectively.

Comparison of breeds

PCA was performed using plink and ancestry was assessed using admixture (Alexander et al., 2009). admixture results were visualized using Pophelper 2.2.7 (Francis, 2017). Weir and Cockerham's FST values, observed (H o) and expected heterozygosity (H e), and Wright's inbreeding coefficient (FIS) were calculated for all 10 populations using the hierfstat r‐package (Goudet, 2005). The values of FST were visualized in a neighbor‐net graph via splitstree (Huson & Bryant, 2006). A neighbor‐joining tree was constructed based on individual allele‐sharing distances (‐‐distance 1‐ibs in PLINK) and visualized using splitstree.

Results

Pedigree analysis of BMS

Pedigree analysis in BMS revealed an average progeny of 16 animals per sire (SD 34.6, maximum 364). The average progeny per dam equals 4 (SD 4, maximum 28). Since 2000, five rams had sired over 1200 offspring. In 2016, 329 lambs were born from 24 different sires with an average age of 2.0 years and 174 dams with an average age of 3.0 years. Average litter size was 1.82 and the average generation interval 3.3 years (SD 0.36, range 2.8–4.3) in the period 2010–2016. Average pedigree completeness (birth years 2010–2016) was 94.2% for five generations and 40% for 10 generations. The mean equivalent of complete generations was equal to 8.9. The F ped increased from approximately 5% in 2000 to 12.7% in 2016. The mean rate of inbreeding per generation (∆F) was 0.028 (2010–2016) with a maximum of 0.039 for animals born in 2005. For the 2016 cohort, ∆F was estimated at 0.021 corresponding to an N e of 24. Fig. S1 shows the additive genetic relationship coefficient and the average inbreeding coefficient based on pedigree data per birth year from 1980 to 2016. The additive genetic relationship in most recent years was estimated at 0.11.

Genomic analysis

LD‐based N e in BMS was estimated at 22. Because of the limited sample size, no reliable N e could be obtained for FLS and FMS. Of the unregistered animals, one (out of 29) animal showed a mismatch between genomic breed assignment and the breeder's (visual) breed assignment (Fig. S2). The inclusion of the 28 unregistered animals to the active breeding population of BMS would increase the N e to 24.

To investigate genomic inbreeding, ROH were studied. Table 1 gives an overview of the average homozygosity per population, the detected ROH and calculated inbreeding coefficients (F ROH) for BMS, FLS and FMS. The highest F ROH was observed in BMS (14.5%), followed by FLS (12.4 %). Compared with the Northern European breeds, BMS had the second highest inbreeding level, following EFB (17.0%) (Table S2). For BMS, F ped had a Pearson correlation of 0.67 with F ROH and 0.65 between F ped and F ROH>5Mb. Table 2 shows the correlations between F ROH, F ROH>5 Mb and F ROH>16 Mb for the three populations. Correlations were high for BMS and FMS (>0.90), and only for FLS, the correlation between F ROH and F ROH>16 Mb was lower (0.71). Fig. S3 shows the genomic inbreeding coefficient (F ROH, F ROH>5 Mb and F ROH>16 Mb) vs. the estimated F ped for the 94 BMS.

Table 1.

Overview of the average observed homozygosity, the detected ROH and the average inbreeding coefficient in Belgian Milk Sheep (BMS), Flemish Sheep (FLS) and Friesian Milk Sheep (FMS).

| BMS | FLS | FMS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average observed homozygosity | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.067 (0.003) | 0.065 (0.003) | 0.065 (0.002) |

| Range | 0.059–0.075 | 0.060–0.070 | 0.060–0.068 |

| Number of ROH | |||

| Mean (SD) | 46.9 (14.5) | 45.2 (19.8) | 49.6 (9.5) |

| Range | 1–82 | 9–77 | 37–79 |

| Total ROH length per individual (Mb) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 382 (177) | 327 (162) | 270 (121) |

| Range | 5–888 | 30–647 | 155–646 |

| ROH length (Mb) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8 (7) | 7 (6) | 5 (5) |

| Range | 2–89 | 2–55 | 2–54 |

| F ROH (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.5 (6.7) | 12.4 (6.2) | 10.2 (4.6) |

| Range | 0.2–33.7 | 1.2–24.6 | 5.9–24.5 |

| F ROH>5Mb (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11.7 (6.4) | 9.5 (5.3) | 6.0 (4.5) |

| Range | 0–31.5 | 0.2–22.5 | 2.1–19.1 |

| F ROH>16Mb (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.7 (4.7) | 3.1 (3.9) | 1.5 (2.7) |

| Range | 0–20.5 | 0–18.4 | 0–9.6 |

SD, Standard deviation.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations between F ROH, F ROH>5 Mb and F ROH>16 Mb show the consistency of inbreeding estimates using different ROH length categories in Belgian Milk Sheep (BMS), Flemish Sheep (FLS) and Friesian Milk Sheep (FMS).

| BMS | FLS | FMS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F ROH and F ROH>5Mb | 0.992 | 0.978 | 0.992 |

| F ROH and F ROH>16Mb | 0.903 | 0.705 | 0.964 |

| F ROH>5 Mb and F ROH>16 Mb | 0.992 | 0.812 | 0.975 |

Comparison of breeds

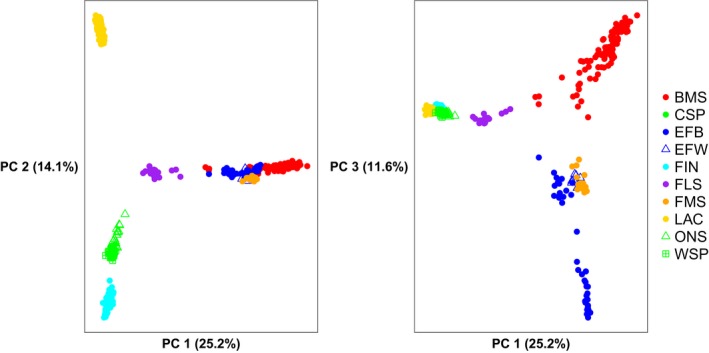

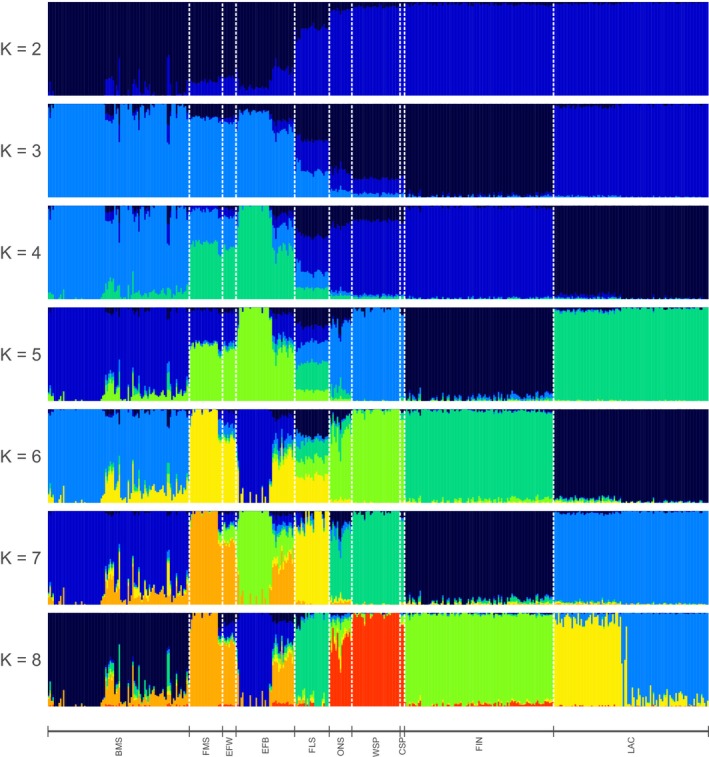

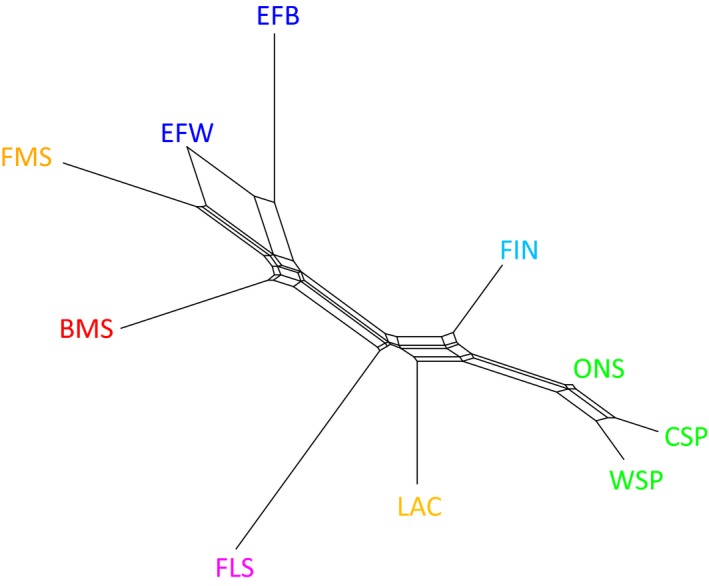

PCA results are shown in Fig. 1. The first three principal components explain 50.9% of the interbreed variation. Within‐breed analysis for BMS and FLS populations did not reveal separate clusters of breeders (results not shown). Fig. 2 shows the model‐based clustering for K = 2 to K = 8 different clusters. K = 8 was found to be the most likely K‐value using 5‐fold cross‐validation (Fig. S4). Weir and Cockerham's F ST values were estimated at 0.121 between BMS and FMS and 0.158 between BMS and FLS and are visualized in a neighbor‐net graph (Fig. 3). The F ST value between BMS and unregistered BMS was 0.009. Fig. S5 shows the neighbor‐joining tree based on allele‐sharing distances between all individuals. Mean H o and H e were 0.310 and 0.316 for BMS and ranged from 0.295 to 0.362 and from 0.293 to 0.365 for all 10 breeds respectively. An overview of all estimated population statistics (H o, H e, F IS and F ROH) is given in Table S2.

Figure 1.

PCA: PC1 and PC2 (left) and PC1 and PC3 (right). BMS, Belgian Milk Sheep; CSP, Colored Spaelsau; EFB, East Friesian Brown; EFW, East Friesian White; FIN, Finn Sheep, FLS, Flemish Sheep; FMS, Friesian Milk Sheep; LAC, Milk Lacaune; ONS, Old Norwegian Spaelsau; WSP, White Spaelsau.

Figure 2.

admixture clustering from K = 2 to 8. Breed abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Figure 3.

Neighbor‐net graph based on Weir and Cockerham's F ST shows the close relation between Belgian Milk Sheep and Friesian sheep populations. Breed abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Discussion

Inbreeding analysis of BMS

Pedigree analysis showed a low number of frequently used sires. Since 2000, five rams (out of 210) sired over 20% of the whole newborn population. This has resulted in unequal family sizes and an increase in ∆F ped from 2000 to 2016 of 0.016 per generation and even more (up to 0.028) in most recent years. One aspect of this increase in F ped could be attributed to obligatory selection for scrapie resistance which started in 2004. Dobly et al. (2013) found that this breeding directive had a large impact on BMS. This increase in F ped was followed by an increase in the additive genetic relationship (leading to 0.11 for animals born between 2010 and 2016). For optimal conservation, all parents should have an equal chance of contributing offspring to the next generation (Falconer & Mackay, 1996). Moreover, FAO guidelines indicate that ∆F should not exceed 0.005 to limit genetic variability loss and limit the spread of genetic defects (FAO, 1998).

The pedigree‐based N e (24) is consistent with the N e of 22 based on genomic information and is far below the guideline of at least 50–100 individuals (FAO, 1998). This indicates that BMS are at risk of inbreeding depression and actions should be undertaken to increase, or at least stabilize, N e.

A balanced use of rams would be the first easy‐to‐follow advice, as this reduces the relative contributions of all rams in the next generation (Lewis & Windig, 2017). Optimal contribution selection could be a more sophisticated approach to balancing the rams' contributions (Lewis & Windig, 2017; Meuwissen & Oldenbroek, 2017). In addition, expansion of the active population can be achieved by raising the number of breeders and/or the number of ewes per breeder and, as advised now to the flockbook, to include unregistered but phenotypically similar animals. Twenty‐eight of 29 unregistered animals showed a close relationship with the registered BMS population (F ST = 0.009) (Fig. S2). If these animals would be included in the flockbook, current N e would increase by 2 (9%). Another option would be to exchange breeding animals between related populations (crossbreeding).

Population‐averaged F ROH in BMS was high (14.5%), with only EFB having a higher F ROH (17.0%), and lower in FLS (12.4%) and FMS (10.2%). This difference could not be confirmed in the average homozygosity of all SNPs (Table 1). Also, the structure of inbreeding differed between BMS and FMS: in FMS a large proportion of short ROH was found (mean ROH length = 5 Mb) compared with BMS (mean ROH length = 8 Mb).

This is also evidenced in F ROH, F ROH>5 Mb and F ROH>16 Mb, where F ROH>5 Mb and F ROH>16 Mb can be interpreted as more recent detectable inbreeding proportions. In BMS, about 80% of all detectable inbreeding originates from approximately the last 10 generations and 32% originates from approximately the last three generations. Similarly, in FLS, this is estimated at 77 and 25% respectively. In FMS, however, only 59% of all detectable inbreeding can be approximately attributed up to the last 10 generations and 15% to the last three generations. For BMS, the large proportion of detected inbreeding up to the past three generations coincides with the results found in the pedigree analysis. High correlations between F ROH, F ROH>5 Mb and F ROH>16 Mb show the consistency between inbreeding estimates based on different ROH length categories. The only moderate correlation between F ROH and F ROH>16 Mb was found in the FLS population (0.705) and indicates that some animals were recently inbred without previous inbreeding marks.

In this study, stringent conditions to ROH identification were applied in order to limit false detections: only one missing call and no heterozygous calls were allowed. Only three of 19 studies using medium‐density SNP data, reviewed by Peripolli et al. (2017), imposed similar or stronger restrictions, whereas other cited studies allowed one heterozygous SNP and between two and five missing SNPs in the same run, combined with a minimum constraint of 20 or 30 SNPs (or even none). Only two of 19 studies reviewed by Peripolli et al. (2017) used the requirement of at least 30 consecutive SNPs to identify an ROH. Although Purfield et al. (2012) and Ferenčaković et al. (2013) indicate that the minimum length of correctly identified ROH on a 50K SNP array should extend for at least 5 or 4 Mb respectively, they do not impose stringent conditions on the minimal number of SNPs in the ROH. In this study, minimal ROH length was 50, 43 and 46 SNPs for BMS, FLS and FMS respectively.

In BMS, F ped estimates were moderately correlated with F ROH (0.67) and F ROH>5Mb estimates (0.65). F ROH>5Mb is the closest approximation of genomic inbreeding to a pedigree depth of 8.9 generations. Similar correlations were reported by Purfield et al. (2012), Zhang et al. (2015) and Marras et al. (2015) in cattle and by Mastrangelo et al. (2018) in sheep. Causes for only moderate correlation between F ped and F ROH have been attributed to pedigree incompleteness and shallow pedigree depth (Purfield et al. (2017)). Although these causes cannot be excluded, they are considered to be negligible for BMS given the fairly high average equivalent complete generations (8.9) and the calculated pedigree completeness. Another possible cause for lower correlations is pedigree or sampling errors, which could be detected using Fig. S3. Moreover, F ped is based on theoretical inbreeding and does not take the stochastic effect of Mendelian sampling into consideration (Curik et al., 2014), and it assumes that founder animals are unrelated, which is unlikely. The strength of F ROH lies in its independency of information on ancestors, nor does it require a base or reference population. Hence, ROH‐based inbreeding estimates are an interesting indicator in local breeds, especially when pedigree data are not available. Notably, the classical F IS metric, which is based on the heterozygote deficit, is similar for BMS, FLS and FMS (Table S2) and thus gives independent information.

Comparison of breeds

The comparison of breeds showed that BMS are more closely related to FMS, EFB and EFW populations than to FLS (Figs 1 and 3) and that these milk sheep are clustered separately from the other northern European breeds. admixture analysis (Fig. 2) shows at low K‐values the close relation between BMS and Friesian populations (FMS, EFB and EFW). At higher K‐values, several BMS sheep appear to have been influenced by EFW, whereas three FMS and almost half of the EFB sheep are similar to EFW, which is in agreement with the neighbor‐joining trees of individuals (Fig. S5). Three BMS individuals have FLS ancestry, one of which is shown in Fig. S5 attached to the FLS cluster. However, at the breed level FLS is not as closely related to the BMS as was expected by the breeders and thus follows the description by Porter et al. (2016).

This is in agreement with the paternal lineages revealed by the Y‐chromosomal oY1.1. FLS share the derived G allele with several English breeds, whereas BMS, EFW and EFB have the ancestral A allele. These results are in accordance with the distinctive phenotypes: the typical recessive rat tail and high milk production shared by BMS, EFW and EFB. Both traits are affected by crossbreeding, and the fact that they are still present suggests the absence of crossbreeding events with other populations. Therefore, the populations that are most suitable for restoring the low N e of BMS are FMS and EFW.

The group of Scandinavian sheep (FIN, ONS, WSP and CSP) cluster together (Figs 1 and 2). LAC can be regarded as an outgroup in this set of breeds and no clear affinity between LAC and BMS (and other related dairy breeds) was found (Fig. 2).

This interbreed analysis using Sheep HapMap genotypes (Kijas et al., 2012) underlines the importance of genotype repositories. These create the opportunity for meta‐analysis of small and/or local breeds in the context of an international panel without a prohibitive investment in genotyping.

Conclusions

This study reveals for the first time the genomic diversity of BMS compared with FLS, FMS and other Northern European breeds. Genomic data confirmed the breed's low effective population size of 22 inferred from pedigree analysis. The limited number of sires used in the past resulted in an average genomic inbreeding coefficient (F ROH) of 14.5% in the current population. This study further reveals that the BMS population is closely related to FMS, EFW and EFB populations and more distantly to FLS. Recommendations to preserve the BMS include: (1) an increase in the number and a more balanced use of rams; (2) the inclusion of phenotypically and genotypically look‐a‐likes in the official registry; and (3) the exchange of breeding animals with the (East) Friesian (Milk) Sheep.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Availability of data

The 50 K SNP datasets of BMS, FMS and FLS are accessible via Figshare (DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11322842).

Supporting information

Figure S1. Average additive genetic relationship and inbreeding coefficients (F ped) by year of birth for Belgian Milk Sheep from 1980 to 2016.

Figure S2. The PCA [PC1 and PC2 (left) and PC1 and PC3 (right)] shows that most of the unregistered Belgian Milk Sheep (BMS_unreg) cluster in the Belgian Milk Sheep group.

Figure S3. Genomic inbreeding coefficients based on ROH (FROH) compared with the estimated inbreeding coefficient based on pedigree data for all 94 genotyped Belgian Milk Sheep.

Figure S4. Five‐fold cross validation errors indicate K = 8 as most likely modeling choice in the admixture analysis.

Figure S5. The neighbor‐joining tree based on allele‐sharing distances. Breed abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Table S1. Summary of SNP quality control in Belgian Milk Sheep (BMS), Flemish Sheep (FLS) and Friesian Milk Sheep (FMS).

Table S2. Summary of inbreeding coefficient analysis based on ROH in the studied breeds, where N is the number of studied individuals, l is the minimal number of SNPs in a ROH, mean H o is the mean observed heterozygosity, mean H e is the mean expected heterozygosity and mean F ROH is the mean inbreeding coefficient based on ROH.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the flockbooks Kleine Herkauwers Vlaanderen and Steunpunt Levend Erfgoed as well as Wouter Merckx (Zootechnical centre, KU Leuven) for the provision of blood samples and pedigree data. This project was funded by the Flemish Government: Department of Agriculture and Fisheries and by an SB PhD grant of the Research Foundation Flanders (1S37119N). The ovine SNP50 Sheep HapMap dataset used in the analyses was obtained via http://www.sheephapmap.org in agreement with the International Sheep Genomics Consortium Terms of Access.

References

- Alexander D.H., Novembre J., Lange K. (2009) Fast model‐based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Research 19, 1655–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.C., Chow C.C., Tellier L.C., Vattikuti S., Purcell S.M, Lee J.J. (2015) Second‐generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience 4, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coster A. (2011). Pedigree: pedigree functions. [Google Scholar]

- Curik I., Ferenčaković M., Sölkner J. (2014) Inbreeding and runs of homozygosity: A possible solution to an old problem. Livestock Science 166, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dumasy J.‐F., Daniaux C., Donnay I., Baret P.V. (2012) Genetic diversity and networks of exchange: a combined approach to assess intra‐breed diversity. Genetics Selection Evolution 44, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer D., Mackay T. (1996) Introduction to Quantitative Genetics, 4th edn Essex: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . (1998). Secondary guidelines for development of national farm animal genetic resources management plans: Management of small populations at risk. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2007) The state of the World's animal genetic resources for food and agriculture. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- Ferenčaković M., Sölkner J., Curik I. (2013) Estimating autozygosity from high‐throughput information: effects of SNP density and genotyping errors. Genetics Selection Evolution 45, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R.M. (2017) POPHELPER: an R package and web app to analyse and visualize population structure. Molecular Ecology Resources 17, 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- François L., Wijnrocx K., Colinet G., Gengler N., Hulsegge B., Windig J.J., Janssens S. (2017). Genomics of a revived breed: Case study of the Belgian campine cattle. PLoS ONE, 12, e0175916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudet J. (2005) HIERFSTAT, a package for R to compute and test hierarchical F‐statistics. Molecular Ecology Notes 5, 184–6. [Google Scholar]

- Groeneveld E., Westhuizen B., Maiwashe A., Voordewind F., Ferraz J. (2009) POPREP: a generic report for population management. Genetics and Molecular Research 8, 1158–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson D.H., Bryant D. (2006) Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Molecular Biology Evolution 23, 254–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kijas J.W., Lenstra J.A., Hayes B., Boitard S., Neto P. (2012) Genome‐wide analysis of the world's sheep breeds reveals high levels of historic mixture and strong recent selection. PLoS Biology 10, 1001258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marras G., Gaspa G., Sorbolini S., Dimauro C., Ajmone‐Marsan P., Valentini A., Williams J.L., Macciotta N.P.P. (2015) Analysis of runs of homozygosity and their relationship with inbreeding in five cattle breeds farmed in Italy. Animal Genetics 46, 110–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrangelo S., Ciani E., Sardina M.T., Sottile G., Pilla F., Portolano B. (2018) Runs of homozygosity reveal genome‐wide autozygosity in Italian sheep breeds. Animal Genetics 49, 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows J.R.S., Hanotte O., Drögemüller C., Calvo J., Godfrey R., Coltman D. , Maddox J.F., Marzanov N., Kantanen J., Kijas J.W. (2006) Globally dispersed Y chromosomal haplotypes in wild and domestic sheep. Animal Genetics 37, 444–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen T., Oldenbroek K. (2017) Chapter 5 Management of genetic diversity including genomic selection in small in vivo populations In: Oldenbroek K, ed. Genomic management of animal genetic diversity. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen. [Google Scholar]

- Peripolli E., Munari D.P., Silva M.V.G.B., Lima A.L.F., Irgang R., Baldi F. (2017) Runs of homozygosity: current knowledge and applications in livestock. Animal Genetics 48, 255–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter V., Alderson L., Hall S.J.G., Sponenberg P. (2016). Mason's World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding. CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Pryce J.E., Haile‐Mariam M., Goddard M.E., Hayes B.J. (2014) Identification of genomic regions associated with inbreeding depression in Holstein and Jersey dairy cattle. Genetics Selection Evolution 46, 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purfield D.C., Berry D.P., Mcparland S., Bradley D.G. (2012) Runs of homozygosity and population history in cattle. BMC Genetics 13, 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purfield D.C., Mcparland S., Wall E., Berry D.P. (2017) The distribution of runs of homozygosity and selection signatures in six commercial meat sheep breeds. PLoS ONE 12, e0176780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura R.V., Lee M., Miller S.P., Clarke S.M., Mcewan J.C. (2015) Assessing imputation accuracy using a 15K low density panel in a multi‐breed New Zealand sheep population. Proceedings of the Association for the Advancement of Animal Breeding and Genetics, 21, 302–5 [Google Scholar]

- Waples R.S. (1991) Genetic Methods for Estimating the Effective Size of Cetacean Populations. Genetic Ecology of Whales and Dolphins 95(2), 279–300. [Google Scholar]

- Waples R.S. (2006) A bias correction for estimates of effective population size based on linkage disequilibrium at unlinked gene loci. Conservation Genetics 7, 167–84. [Google Scholar]

- Weir B.S., Hill W.G. (1980) Effect of mating structure on variation in linkage disequilibrium. Journal Series of the North Carolina Agricultural Research Service 95, 477–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellmann R. (2018) Package ‘optiSel’. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/optiSel/optiSel.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Average additive genetic relationship and inbreeding coefficients (F ped) by year of birth for Belgian Milk Sheep from 1980 to 2016.

Figure S2. The PCA [PC1 and PC2 (left) and PC1 and PC3 (right)] shows that most of the unregistered Belgian Milk Sheep (BMS_unreg) cluster in the Belgian Milk Sheep group.

Figure S3. Genomic inbreeding coefficients based on ROH (FROH) compared with the estimated inbreeding coefficient based on pedigree data for all 94 genotyped Belgian Milk Sheep.

Figure S4. Five‐fold cross validation errors indicate K = 8 as most likely modeling choice in the admixture analysis.

Figure S5. The neighbor‐joining tree based on allele‐sharing distances. Breed abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Table S1. Summary of SNP quality control in Belgian Milk Sheep (BMS), Flemish Sheep (FLS) and Friesian Milk Sheep (FMS).

Table S2. Summary of inbreeding coefficient analysis based on ROH in the studied breeds, where N is the number of studied individuals, l is the minimal number of SNPs in a ROH, mean H o is the mean observed heterozygosity, mean H e is the mean expected heterozygosity and mean F ROH is the mean inbreeding coefficient based on ROH.

Data Availability Statement

The 50 K SNP datasets of BMS, FMS and FLS are accessible via Figshare (DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11322842).