Abstract

Melanoma is among the few cancers that demonstrate an increasing incidence over time. Simultaneously, this trend has been marked by an epidemiologic shift to earlier stage at diagnosis. Before 2011, treatment options were limited for patients with metastatic disease, and the median overall survival was less than 1 year. Since then, the field of melanoma therapeutics has undergone major changes. The use of anti–CTLA‐4 and anti‐PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitors and combination BRAF/MEK inhibitors for patients with BRAF V600 mutations has significantly extended survival and allowed some patients to remain in durable disease remission off therapy. It has now been confirmed that these classes of agents have a benefit for patients with stage III melanoma after surgical resection, and anti‐PD1 and BRAF/MEK inhibitors are standards of care in this setting. Some patients with stage II disease (lymph node‐negative; American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IIB and IIC) have worse melanoma‐specific survival relative to some patients with stage III disease. Given these results, expanding the population of patients who are considered for adjuvant therapy to include those with stage II melanoma has become a priority, and randomized phase 3 clinical trials are underway. Moving into the future, the validation of patient risk‐stratification and treatment‐benefit prediction models will be important to improve the number needed to treat and limit exposure to toxicity in the large population of patients with early stage melanoma.

Keywords: adjuvant therapy, BRAF, immunotherapy, melanoma, PD1, pd‐1, risk stratification, stage II, targeted therapy

Short abstract

Adjuvant therapy has improved outcomes in patients with stage III melanoma and is being explored in those with stage II melanoma. Stage III data as well as risk‐stratification tools and clinical considerations for the lymph node‐negative population are reviewed.

Introduction

Malignant melanoma is 1 of the few cancers currently increasing in incidence. There were approximately 74,000 new cases of melanoma in the United States in 2015, increasing to >90,000 cases in 2018.1, 2 The majority of melanomas are cutaneous, with risk factors that include ionizing ultraviolet radiation and genetic factors.3 By incidence, the most common presentation of cutaneous melanomas is at an early stage (stages I and II), defined within the American Joint Cancer (AJCC) classification by modern surgical staging as lacking lymph node involvement. High‐risk cancers are usually considered those that are ulcerated, involve lymph nodes, demonstrate microsatellitosis, or in‐transit disease (stage III).

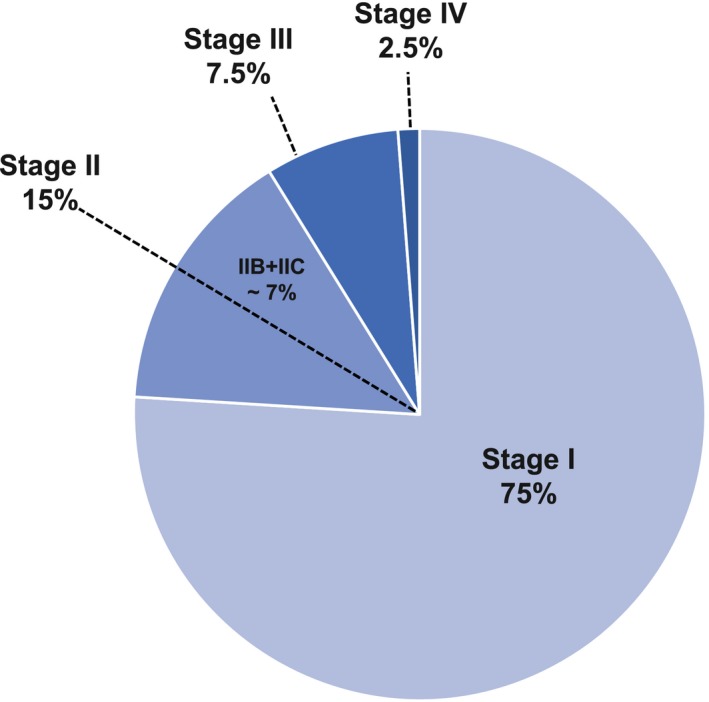

Although sometimes described to be “low‐risk,” patients with stage IIA through IIC melanoma carry a melanoma‐specific mortality rate of 12% to 25% over the course of 10 years.4 Epidemiologic studies of melanoma incidence in the United States and Europe suggest that there is a substantial population of these at‐risk patients. A US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database review of melanoma cases from 2011 through 2015 identified approximately 11% of patients with stage II disease.5 This may be a modest underestimation of the true stage II incidence because SEER data do not contain staging data for approximately 9% of cases. European data sets suggest that a range from 10% to 20% of all new cases present as stage II, smaller fractions present with stage III or IV disease, and the majority of new cases present as stage I,6, 7 similar to US data (Fig. 1).5, 6, 7

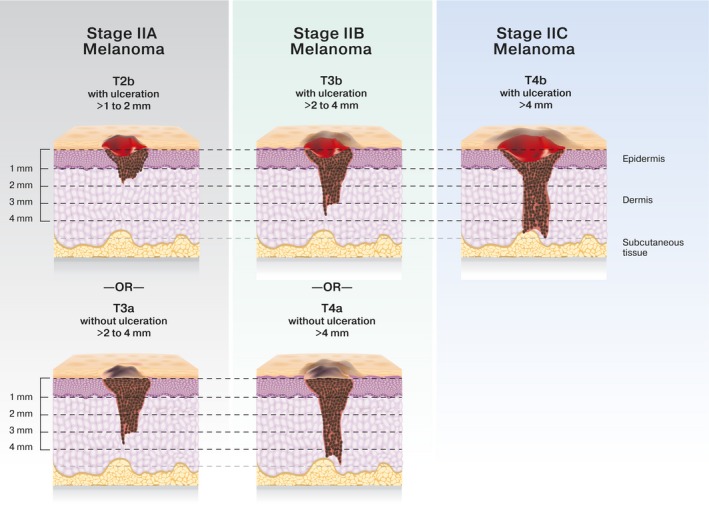

Figure 1.

Schematic of stage II melanoma according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Cancer Classification.

The AJCC has modified the melanoma staging system over time to account for a better understanding of histologic prognostic factors. Many early adjuvant melanoma trials and epidemiologic data incorporate AJCC version 6 (AJCCv6), whereas more modern melanoma adjuvant trials have used AJCC version 7 (AJCCv7). Currently, AJCC version 8 (AJCCv8) is used for staging and prognosis, with refinement of highest risk and lowest risk subgroups. Over the period that these staging systems have changed, however, definitions for stage II melanoma have remained constant (Fig. 1). It is possible to estimate the number of patients with thick and/or ulcerated, lymph node‐negative, melanoma (stages IIB and IIC) who remain at high risk of melanoma relapse and may benefit from adjuvant therapy (Fig. 2). Approximately one‐half of patients with stage II melanoma will have stage IIB or IIC disease and are at the highest risk of recurrence.5 This roughly equates to the number of patients who present with stage III melanoma, for which adjuvant therapy is the standard of care.5

Figure 2.

Melanoma incidence is illustrated. Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program database were estimated using the percentage frequency distribution by stage derived from SEER*Stat software; specifically, patients who had newly diagnosed with melanoma in years 2011 through 2015 were used, and stage group was derived from the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th edition, for all ages combined. Data sources include the National Cancer Institute, 20185; Rockberg et al, 20166; and Schoffer et al, 2016.7

In addition to the well documented increase in melanoma incidence, another emerging pattern surrounds increased understanding of the contribution to overall melanoma mortality coming from earlier stage tumors (stages I‐IIA). In fact, thin melanomas (<2 mm) accounted for over twice as many deaths from melanoma than thick melanomas (>4 mm) in the Queensland Cancer Registry from 1990 through 20098 because of the large incidence of thin melanoma. Similar findings have been reported in the US SEER database.9 Simply stated, although the risk of death for an individual patient with a thin melanoma is substantially less than that for a patient with a thick melanoma, there are many more cases of thin melanomas and thus the absolute number of deaths is substantially higher in the population with thin melanomas. It is apparent then that a significant and ongoing unmet need exists for patients with earlier stage melanoma.

Prior barriers to the development of adjuvant therapies for earlier stage melanoma have been the marginal effectiveness of adjuvant therapy with interferon‐α2b (IFN) and the substantial associated toxicity of that interferon and other treatments, such as the anti‐CTLA4 antibody ipilimumab. In addition, the relatively lower incidence of disease progression in earlier stage disease relative to stage III disease required a level of efficacy historically deemed unreachable for systemic agents.9 This toxicity‐to‐benefit ratio is no longer as significant a barrier with the advent of antiprogrammed death 1 (anti‐PD1) receptor antibodies as well as targeted therapies for patients with tumors harboring BRAF V600E/V600K mutations.

Surgical resection with appropriate margins and consideration of sentinel lymph node biopsy remains the standard of care of treatment for primary melanoma. After surgical removal of melanoma, some patients remain at risk of relapse; then, the goal of adjuvant systemic therapy is to minimize that risk. Interferon has been an approved therapy for high‐risk melanoma since the 1990s, although the benefits of adjuvant IFN therapy even in stage III melanoma were hotly debated, and this therapy was not shown to be useful in patients with earlier stage disease.10 With the development of checkpoint antibodies and BRAF‐targeted therapy, IFN no longer has a clear role in the management of melanoma.

Ipilimumab has been associated with long‐term survival in approximately 21% of treated patients who have advanced melanoma.11 In 2015, with the reporting of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trial 18071 (EORTC‐18071), 3 years of adjuvant high‐dose ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg was shown to reduce the likelihood of relapse by 24% in the adjuvant management of high‐risk stage III melanoma compared with placebo.12 However, this benefit came at somewhat of a cost, in that the Common Terminology for the Characterization of Adverse Events (CTCAE) grade 3 and 4 adverse event (AE) rate was 54.1%, including a treatment‐related mortality rate of 1% for patients who received adjuvant ipilimumab therapy (deaths from colitis, myocarditis, and Guillain‐Barre syndrome). Despite a survival advantage to the therapy, the toxicity of ipilimumab limited its application to high‐risk patients, and it was not deemed reasonable to test its utility for individuals with a lower risk for melanoma relapse. Currently, the use of adjuvant high‐dose ipilimumab has also fallen out of favor, replaced by anti–PD1‐dorected or BRAF‐directed therapies.

Role of Anti‐PD1 Therapy in Melanoma

Anti‐PD1 antibodies have been confirmed to improve survival outcomes in the metastatic setting and are now considered a default standard of care for melanoma. These agents, nivolumab and pembrolizumab, demonstrate response rates consistently in the 30% to 40% range, depending on the line of therapy, with a high‐grade (CTCAE grade 3 and 4) AE rate of 10% to 15% across many studies.13 It has also been confirmed that the durability of benefit from anti‐PD1 therapy persists over the course of years, even after therapy has stopped. In the phase 3 KEYNOTE‐006 study (A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled, 3Three‐Arm, Phase III Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Two Dosing Schedules of Pembrolizumab [MK‐3475] Compared to Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma),14 834 patients with ipilimumab‐naïve, advanced melanoma were randomized at a 1:1:1 ratio to receive either 1 of 2 dosing schedules of pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg) every 2 weeks or every 3 weeks for up to 2 years or 4 doses of ipilimumab (3 mg/kg) every 3 weeks. The 4‐year OS rate was 42% for patients in the pooled pembrolizumab arms (n = 556).15 The objective response rate to pembrolizumab was 42%, and 62% of these responding patients had a response lasting ≥42 months. Of 556 patients, 103 (19%) completed the protocol‐specified 2‐year pembrolizumab therapy. The median follow‐up was 20.3 months after pembrolizumab completion; 89 patients (86%) did not progress, and only 14 patients had progressive disease. These findings confirm the outstanding durability of antitumor activity for most patients who respond to anti‐PD1 therapy, even during extended periods without ongoing therapy after a finite dosing period.

In consideration of moving immunotherapy from the metastatic setting to the adjuvant setting, a relevant observation has been the correlation of baseline tumor burden with response to therapy and long‐term outcomes.16 In general, lower melanoma metastatic tumor burdens are associated with improved responses to therapy. In addition, there are several clinical, molecular, and pathologic markers associated with benefit and resistance to anti‐PD1 that have been described in the literature, including programmed death ligand‐1 (PD‐L1) staining in tumor cells,17 IFN‐γ–related mRNA profile,18 tumor mutational burden, and the T‐cell–inflamed tumor microenvironment gene expression signatures.19 Initially, it was unclear whether larger or macroscopic tumors with an immune‐suppressive microenvironment were required for the PD‐1/PDL‐1 pathway to be engaged and antitumor benefit to be seen with anti‐PD1 therapy. Some preclinical models suggested that neoadjuvant therapy with clinically detectable volumes of disease would be required to induce long‐term disease control.20 These preclinical concerns surrounding an overt tumor microenvironment being a requirement for anti‐PD1 activity have been settled in melanoma, however, with the reporting of multiple international adjuvant therapy clinical trials of completely resected stage IIIB and IIIC (AJCCv7) and stage IV disease (Table 1).21, 22, 23, 24, 25 In the CheckMate 238 study (Efficacy Study of Nivolumab Compared to Ipilimumab in Prevention of Recurrence of Melanoma After Complete Resection of Stage IIIB/IIIC or Stage IV Melanoma) of stage III and IV melanoma (stages IIIB and IIIC, resected stage IV; AJCCv7), nivolumab demonstrated superiority to ipilimumab in terms of both relapse‐free survival (RFS) and toxicity profile. Similarly, in the KEYNOTE‐054 study (Study of Pembrolizumab [MK‐3475] Versus Placebo After Complete Resection of High‐Risk Stage III Melanoma, pembrolizumab demonstrated superiority to placebo in patients with completely resected stage III melanoma (stages IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC; AJCCv7).21 Nivolumab and pembrolizumab are both approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of resected stage III melanoma and are considered standards of care for stage III disease.

Table 1.

Summarized Outcome Data for Adjuvant Therapy Trials

| Study | Pembrolizumab, N = 1019 | Nivolumab, N = 905 | Dabrafenib + Trametinib, N = 870 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial and Reference(s) | KEYNOTE‐054: Eggermont 201821 | CheckMate 238: Weber 2017,22 201823 | COMBI‐AD: Hauschild 2018,24 Long 201725 |

| Disease population: AJCC 7th ed | Resected stage III (IIIA, IIIB, IIIC) melanoma | Resected stage IIIC, IIIC, or IV melanoma | Resected stage III (IIIA, IIIB, IIIC) melanoma with BRAF V600E or V600K mutation |

| Study design | Randomized 1:1, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind | Randomized 1:1 between nivolumab and ipilimumab | Randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind |

| Study treatment arm: Dose (route) and frequency | Pembrolizumab 200 mg (IV) every 3 wk for a total of 18 doses | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg (IV) every 2 wk + placebo (IV) every 3 wk for 4 doses and then every 12 wk | Dabrafenib 150 mg (oral) twice daily + trametinib 2 mg (oral) once daily |

| Comparison | Placebo (IV) every 3 wk for a total of 18 doses | Ipilimumab 10 mg/kg (IV) every 3 wk for 4 doses then every 12 wk + placebo (IV) every 2 wk | Matched placebo (oral) twice daily + matched placebo (oral) once daily |

| Duration of treatment | Up to 1 y | Up to 1 y | Up to 1 y |

| Treatment‐related grade 3 and 4 adverse event rate, % | 14.7 | 14.4 | 41.0 |

| Efficacy measure | |||

| RFS [95% CI], % | Pembrolizumab: 75.4 [71.3‐78.9]a | Nivolumab: 62.6b | Dabrafenib + trametinib: 59.0 [55.0‐64.0]c |

| Placebo: 61.0 [56.5‐65.1]a | Ipilimumab: 50.2b | Placebo: 40.0 [35.0‐45.0]c | |

| Dabrafenib + trametinib: 54.0 [49.0‐59.0]d | |||

| Placebo: 38.0 [34.0 – 44.0]d | |||

| HR [95% CI; P] | 0.57 [0.43‐0.74; <.001]e | 0.65 [0.51‐83; <.001]f | 0.47 [0.39‐0.58; <.001]c |

| 0.49 [0.40‐0.59]d |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CheckMate 238, Efficacy Study of Nivolumab Compared to Ipilimumab in Prevention of Recurrence of Melanoma After Complete Resection of Stage IIIB/IIIC or Stage IV Melanoma; COMBI‐AD, Dabrafenib With Trametinib in the Adjuvant Treatment of High‐Risk BRAF V600 Mutation‐Positive Melanoma; HR, hazard ratio; IV, intravenous; KEYNOTE‐054, Study of Pembrolizumab Versus Placebo After Complete Resection of High‐Risk Stage III Melanoma; RFS, recurrence‐free survival.

This was the 1‐year RFS rate.

This was the 2‐year RFS rate.

This was the 3‐year RFS rate.

This was the 4‐year RFS rate.

The 95% CI was 98.4%.

The 95% CI was 97.56%.

The Role of Targeted Therapy in BRAF‐Mutant Melanoma

Targeted therapy has also been validated as an adjuvant approach for patients with melanoma. Approximately 40% to 50% of patients with cutaneous melanoma will harbor a somatic activating BRAF mutation, usually V600E or V600K. For this subset of patients, there are several US Food and Drug Administration‐approved therapy options in the metastatic setting. Combination therapy with a BRAF inhibitor plus an MEK inhibitor is preferred over BRAF‐inhibitor or MEK‐inhibitor monotherapy because of factors relating to efficacy and toxicity. In patients with advanced disease, combination therapies with dabrafenib plus trametinib, vemurafenib plus cobimetinib, and encorafenib plus binimetinib are all considered standards of care, with response rates ranging from 60% to 70% and a median progression‐free survival ranging from 11 to 15 months.26, 27, 28 To date, none of these combination regimens have been directly compared with one another to evaluate for superiority.

Although resistance and progression develop in the majority of patients who receive BRAF‐MEK therapy, some patients experience long‐term disease control. As is the case with anti‐PD1 therapy, prolonged survival and improved responses to BRAF and MEK inhibitors have been demonstrated in patients with a smaller metastatic disease burden.29, 30, 31 In a landmark analysis of the COMBI‐D trial (Phase III, Randomized, Double‐Blinded Study Comparing the Combination of the BRAF Inhibitor, Dabrafenib, and the MEK Inhibitor, Trametinib, to Dabrafenib and Placebo as First‐Line Therapy in Subjects With Unresectable [Stage IIIC] or Metastatic [Stage IV] BRAF V600E/K Mutation‐Positive Cutaneous Melanoma) of dabrafenib and trametinib compared with dabrafenib and placebo, the number of metastatic organ sites and the level of lactate dehydrogenase were identified as important prognostic factors for combination therapy.30 A pooled analysis of phase 3 trials found that normal lactate dehydrogenase levels, <3 metastatic organ sites, and a sum of lesion dimensions <66 mm identified the best prognostic group of those receiving combination therapy, with a 3‐year progression‐free survival rate of 42%, suggesting durable disease control without immunotherapy for some patients with low tumor burdens.31

The combination of dabrafenib and trametinib has also been evaluated as adjuvant therapy in the COMBI‐AD trial (A Phase III Randomized Double Blind Study of Dabrafenib [GSK2118436] in Combination With Trametinib (GSK1120212) Versus Two Placebos in the Adjuvant Treatment of High‐Risk BRAF V600 Mutation‐Positive Melanoma After Surgical Resection), treating patients with resected stage III disease (Table 1). Long‐term RFS data have now been reported24 and, at a median follow‐up of 44 months (dabrafenib plus trametinib) and 42 months (placebo), the 4‐year RFS rates were 54% (95% CI, 49%‐59%) in the dabrafenib plus trametinib arm and 38% (95% CI, 34%‐44%) in the placebo arm, respectively (hazard ratio [HR], 0.49; 95% CI, 0.40‐0.59). The estimated cure rate was 54% (95% CI, 49%‐59%) in the dabrafenib plus trametinib arm compared with 37% (95% CI, 32%‐42%) in the placebo arm. This confirmation of long‐term benefit from adjuvant, targeted therapy demonstrates a utility for patients with BRAF V600 mutations approximately similar to that of anti‐PD1 therapy.

Choice of Adjuvant Therapy—Safety Considerations

Therapy with PD1 inhibitors, regardless of BRAF mutation status, and with BRAF/MEK inhibitors for BRAF V600‐mutant tumors are both acceptable options for patients who have high‐risk melanoma in surgical remission. These adjuvant therapy regimens have not been directly compared with each other; therefore, it is left to providers to compare the safety, side‐effect profiles, and preferences of individual patients when considering the treatment approach. For instance, BRAF/MEK inhibitors commonly are associated with constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, fatigue, headache, rash, arthralgias, myalgias, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Dose adjustments are common. In the COMBI‐AD trial, 26% of patients had AEs leading to permanent discontinuation of a trial drug, 38% had AEs leading to a dose reduction, and 66% had AEs leading to a dose interruption. Serious AEs occurred in 36% of patients in the combination‐therapy group and in 10% of those in the placebo group. These data suggest that, although it is generally tolerable for many patients, most patients will have some degree of symptomatic toxicity, leading to at least 1 dose interruption, and greater than one‐third will develop serious toxicity. Fortunately, for most patients, once drug therapy is interrupted, toxicities abate in a relatively short time. It is clear, however, that patients should expect to experience side effects during the year of prescribed adjuvant therapy. In addition, these agents are considered to carry some risk of additional malignancies, usually cutaneous, although various noncutaneous malignancies have been reported in isolation as potentially related32 to BRAF/MEK inhibitor therapy. The incidence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is 3% with combination therapy.

The toxicity of anti‐PD1 therapy compares favorably to many agents used within the spectrum of medical oncology, including in the adjuvant setting. Anti‐PD1 antibodies are associated with grade 3 and 4 immune‐related AEs, ranging from 10% to 15%, including from adjuvant therapy trials (Table 1). As part of the KEYNOTE‐054 trial, a health‐related quality‐of‐life substudy investigated 1 year of adjuvant pembrolizumab and found that it maintained health‐related quality of life compared with placebo, as defined by the 30‐item EORTC Quality‐of‐Life Core Questionnaire.33 Despite the general safety, however, serious toxicities will develop for a subset of patients. Some of these toxicities are permanent, and others may be severe and/or life‐threatening. In addition to the more commonly encountered grade 3 and 4 toxicities, such as colitis, rash, pneumonitis, and hepatitis, endocrinopathies resulting from anti‐PD1 therapy are important to consider. In CheckMate‐238, adrenal dysfunction, diabetes, pituitary dysfunction, and thyroid dysfunction were all reported, with 102 of 452 patients (22.5%) developing an endocrine‐related AE.34 Of these events, 1.5% of patients developed grade 3 or 4 endocrine‐related AEs. It is important to note that CTCAE version 5 grading requires medical intervention for grade 2 endocrinopathies and hospitalization for grade 3 endocrinopathies. Most endocrinopathies, permanent or not, can be identified and managed in the outpatient setting, leading to toxicity graded as CTCAE grade 1 or 2. We also note that 43% of the endocrine‐related AEs identified during CheckMate‐238 did not resolve during study follow‐up. Although some endocrinopathies. such as hypothyroidism. are straightforward to manage, lifelong medical therapy may be needed, and other toxicities, such as adrenal insufficiency or hypogonadism, may have significant lifelong clinical impacts. Consideration of the potential permanence of an endocrinopathy moves into a different risk/benefit strata as we consider the treatment of patients with earlier stage disease, many of whom already may have been cured by surgery.

Melanoma is 1 of the most common cancers in young adults, and many patients with early stage melanoma will be diagnosed during their child‐bearing years, with some even diagnosed during adolescence. In general, therapies administered in the field of medical oncology are considered harmful to fetal development, and patients are strongly advised to avoid pregnancy during and for several months after completion of chemotherapy. Anti‐PD1 therapy and BRAF/MEK‐inhibitor therapy are different classes of agents than traditional cytotoxic therapy, and their short‐term and long‐term effects on reproductive fitness are less understood. The relatively uncommon but well described development of pituitary dysfunction from anti‐PD1 may lead to significant difficulties with reproductive fitness in some patients. The pituitary is a source of luteinizing hormone, follicle‐stimulating hormone, growth hormone, and oxytocin, and it undergoes significant physiologic changes as part of fetal support during pregnancy.35 Inability for normal responses to pregnancy may affect a woman's ability to conceive or to successfully carry a pregnancy to term. In addition, men who develop hypogonadism and low testosterone also face challenges with reproductive fitness, as exogenous testosterone inhibits spermatogenesis.36 It is speculated that PD1 plays a role in the maintenance of pregnancy,37, 38 and single‐nucleotide sequence variants of the PD1 gene have been identified in women with recurrent pregnancy loss.39 Long‐term fertility studies after therapy are lacking because of the brief duration of clinical use of these agents. Vemurafenib has been reported to lead to intrauterine growth retardation when administered during pregnancy,40 which may be related to the central role that the mitogen‐activated protein kinase pathway plays in trophoblast proliferation. Long‐term effects from targeted therapy on ovarian and testicular function are not yet known and should be the subject of investigation because these agents continue to advance in their use in the curative intent setting.

Risk Stratification

Estimating risk of melanoma recurrence has long been established by histopathologic findings of the tumor at the time of tumor surgery. These factors include the depth of invasion and lymph node status, the presence or absence of ulceration, the mitotic index, the presence of tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes, tumor regression, perineural or angiolymphatic invasion, and microsatellitosis. Moving beyond histopathologic and clinical criteria for risk stratification, molecular analyses appear to be promising for augmenting and refining individualized risk prediction for patients with melanoma. The DecisionDx‐Melanoma assay (Castle Biosciences, Inc), a gene expression profile (GEP), is 1 such technique that is increasing in clinical use in the United States, with over 10,000 cases analyzed annually. The GEP evaluates expression of 31 genes from formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded tissue and determines the risk of metastatic disease in a patient with cutaneous melanoma. The test classifies patients as having a tumor with a low (class 1) or high (class 2) risk for developing metastasis within 5 years of diagnosis. The test further subclassifies patients into class 1a (low‐risk disease, high confidence), class 1b (low‐risk disease, low confidence), class 2a (high‐risk disease, low confidence), and class 2b (high‐risk disease, high confidence). Multiple cohort studies have evaluated the prognostic capabilities of early stage melanoma. In a recent analysis by Gastman, et al,41 the GEP was evaluated in 690 patients across 18 institutions, of whom 259 were sentinel lymph node (SLN)‐negative. Patients with SLN‐negative/class 2b disease had significantly worse RFS, distant metastasis‐free survival, and melanoma‐specific survival rates than those with SLN‐negative/class 1a disease (P < .01 for all comparisons). A class 2b result identified 71.3%, 70.4%, and 78.6% of recurrences, metastases, and melanoma‐specific mortality events, respectively.

Additional molecular profiles have been described in the literature that may also help inform prognosis once larger data sets are reported. The Melanoma Immune Profile (MIP) uses the NanoString nCounter transcriptomic profiling platform (NanoString Technologies) to measure the expression of 53 target genes.42 In an independent cohort of 78 patients, the MIP significantly distinguished patients with distant metastatic recurrence, along with melanoma‐specific survival and OS, using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (P < .05 for all comparisons). A favorable MIP was correlated with a low risk of death from melanoma, with none of 22 patients in the low‐risk group dying of melanoma and 20 of 56 (36%) patients in the high‐risk group dying of melanoma.

These molecular profiles are not yet performed as part of standard entry or stratification criteria into clinical trials, although, with additional prospective data confirming reported their utility, the field may move to formally include these or other assays as part of stratification or selection in clinical trials. The use of molecular profiling to guide decision making for patients with cancer is not unique to melanoma.43 GEP testing for patients with breast cancer (Oncotype [Genomic Health Inc], MammaPrint [Agendia Inc]) is already well established and validated as an essential component to women with early stage breast cancer and defines treatment strategies,44 including the decision whether to offer adjuvant chemotherapy.

In addition to genetic analysis for molecular risk stratification of melanoma, other techniques in development may help identify patients at greatest risk of relapse. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is emerging as a prognostic marker in stage IV melanoma45 and is now under investigation for patients with stage II and III melanoma.46 As part of the AVAST‐M adjuvant trial (Adjuvant Bevacizumab in Patients with Melanoma at High Risk of Recurrence), which evaluated 1 year of bevacizumab versus observation in patients with stage IIB, IIC, and III (AJCCv6 and AJCCv7) cutaneous melanoma, a subgroup of 161 randomly selected patients from both arms of the study with known BRAF or NRAS mutations had ctDNA analyzed within 12 weeks after surgical clearance of their disease (median, 8.3 weeks; range, 2.4‐12 weeks). There was no difference in OS between the bevacizumab and observation arms. In the substudy, patients who had detectable ctDNA had decreased disease‐free (HR, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.79‐5.47; P < .0001) and distant metastasis‐free (HR, 3.22; 95% CI, 1.80–5.79; P < .0001) intervals compared with those who had undetectable ctDNA. The 5‐year OS rate for patients with detectable ctDNA was 33% (95% CI, 14%‐55%) versus 65% (95% CI, 56%‐72%) for those with undetectable ctDNA. With further clinical validation, the ability to risk stratify patients who have noninvasive blood tests could serve as a useful factor for determining which patients are in the greatest need of adjuvant therapy.

In addition, someday, ultraviolet (UV) radiation gene signatures of melanoma tumors may be able to help inform prognosis for patients. Melanoma genome sequencing has revealed a predominance of C‐to‐T nucleotide transitions at dipyrimidines, and this profile is also observed in UV radiation‐exposed cells.47 Furthermore, a unique mutation pattern prevalent in UV radiation‐associated skin cancers, known as signature 7, has been identified. Investigators exploring The Cancer Genome Atlas evaluated tumors and clustered them according to signature 7 (n = 372) or nonsignature 7 (n = 47).47 Within the signature 7 cohort, there was an increase in the number of single nucleotide variants (vs 57.1; P < .0001) and a higher proportion of C‐to‐T transitions at dipyrimidines (mean, 84.7% vs 29%; P < .0001). There was also a greater likelihood of mutations in 10 genes in signature 7‐mutation tumors (LRP1B, ADGRV1, XIRP2, PKHD1L1, USH2A, DNAH9, PCDH15, DNAH10, TP53, and PCDHAC1). Compared with nonsignature 7 patients, signature 7 patients presented longer DFS (P = .0056) and better OS (P < .0001) independent of disease stage at diagnosis, including patients with stage I and II disease. These early data are promising for further development regarding risk stratification, and further research into these areas is ongoing.

Clinical Trials in Stage II Disease

With the successful completion of adjuvant therapy trials in stage III disease and the regulatory approval of pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and dabrafenib plus trametinib for this patient population, the focus has now shifted to patients with stage II disease. Multiple clinical trials are active or are in development. The largest active trial is KEYNOTE‐716 (Safety and Efficacy of Pembrolizumab Compared to Placebo in Resected High‐Risk Stage II Melanoma), a global, phase 3, randomized trial evaluating 1 year of pembrolizumab compared with placebo in stage IIB and IIC melanoma (AJCCv8). In that trial, approximately 954 patients will be enrolled and randomized at a 1:1 ratio to either 1 year (17 cycles) of pembrolizumab dosed every 3 weeks or 1 year of placebo dosed every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint is RFS. The study also includes a second stage, allowing for crossover from placebo or re‐challenge of pembrolizumab. Many of the prognostic markers described above will be incorporated and analyzed as part of the trial, including pharmacokinetic analysis, pharmacodynamics analysis, RNA and genetic analysis, plasma and serum biomarker analysis, stool biomarker analysis, ctDNA, and tumor tissue analysis and molecular profiling. Additional large trials incorporating targeted therapy or immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy are anticipated to open in 2019.

Conclusion

The clinical landscape of melanoma oncology now includes powerful therapies through both immunotargeted and targeted therapies with advantageous risk/benefit ratios. Simultaneously, a large and growing population of patients with earlier stage disease are facing an unacceptably high risk of recurrence and melanoma‐specific mortality. Adjuvant therapy has been validated as a successful approach for the management of stage III melanoma and, because many more patients are diagnosed with stage I or II melanoma than stage III, the time to evaluate the role of these therapies in earlier stage melanoma has arrived. As the field evaluates these therapeutic options, there are new challenges facing researchers. Important research strategies going forward will be the validation and clinical implementation of risk‐assessment tools; including pathologic, molecular, and genomic data, along with a determination of whether prognostic information is complementary when evaluated together in aggregate. Focusing finite health care resources on patients at the highest risk will enable optimal resource utilization and spare low‐risk patients from the risks of treatment. These data will come from ongoing, large‐scale, phase 3 clinical trials, such as the KEYNOTE‐716 study, along with others in development, all of which will include extensive molecular, immune, and pathologic correlative studies. Careful attention to long‐term effects and potential late effects on fertility will be necessary to fully understand the risk/benefit ratio in young, otherwise healthy patients. Despite these potential risks, however, adjuvant therapy in appropriate patients with stage II melanoma ultimately will save lives. We are finally in an era when we can properly evaluate adjuvant curative‐intent strategies for patients with early stage melanoma.

Funding Support

Jason J. Luke was supported by Department of Defense Career Development Award W81XWH‐17‐1‐0265, National Cancer Institute Cancer Clinical Investigator Team Leadership Award P30CA014599‐43S, a Team Science Award from the Melanoma Research Alliance, the Arthur J Schreiner Family Melanoma Research Fund, the J. Edward Mahoney Foundation Research Fund, the Brush Family Immunotherapy Research Fund, and the Buffet Fund for Cancer Immunotherapy.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Andrew S. Poklepovic reports personal fees from Novartis, Merck, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Castle Biosciences outside the submitted work. Jason J. Luke reports research support from Array, CheckMate, Evelo, and Palleon, all outside the submitted work; institutional research support for clinical trials from AbbVie, Boston Biomedical, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Celldex, Compugen, Corvus, EMD Serono, Delcath, Five Prime, FLX Bio, Genentech, Immunocore, Incyte, Leap, MedImmune, Macrogenics, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, Merck, Tesaro, and Xencor, all outside the submitted work; personal fees from 7 Hills, Actym, Alphamab Oncology, Mavu, Pyxis, Springbank, Tempest; personal fees from 7 Hills, AbbVie, Actym, Akrevia, Alphamab Oncology, Array, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Compugen, EMD Serono, IDEAYA, Immunocore, Incyte, Janssen, Jounce, Leap, Mavu, Merck, Mersana, Novartis, Pyxis, RefleXion, Spring Bank, Tempest, and Vividion, all outside the submitted work; travel expenses from Akrevia, Array, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Castle, CheckMate, EMD Serono, IDEAYA, Immunocore, Incyte, Janssen, Jounce, Merck, Mersana, Novartis, RefleXion, all outside the submitted work; serves on the TTC Oncology Data and Safety Monitoring Board outside the submitted work; and holds provisional patent 15/612,657 (Cancer Immunotherapy) and provisional patent PCT/US18/36052 (Microbiome Biomarkers for Anti‐PD‐1/PD‐L1 Responsiveness: Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Uses Thereof).

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fisher DE, James WD. Indoor tanning—science, behavior, and policy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:901‐903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence‐based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer Eighth Edition Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:472‐492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Science . Research Emphasis. Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; 2018. Accessed November 11, 2018. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/research-emphasis/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rockberg J, Amelio JM, Taylor A, Jorgensen L, Ragnhammar P, Hansson J. Epidemiology of cutaneous melanoma in Sweden—stage‐specific survival and rate of recurrence. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:2722‐2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schoffer O, Schulein S, Arand G, et al. Tumour stage distribution and survival of malignant melanoma in Germany 2002‐2011. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whiteman DC, Baade PD, Olsen CM. More people die from thin melanomas (1 mm) than from thick melanomas (>4 mm) in Queensland, Australia. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1190‐1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Melanoma thickness trends in the United States, 1988‐2006. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:793‐797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Agarwala SS, Lee SJ, Yip W, et al. Phase III randomized study of 4 weeks of high‐dose interferon‐alpha‐2b in stage T2bN0, T3a‐bN0, T4a‐bN0, and T1‐4N1a‐2a (microscopic) melanoma: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group‐American College of Radiology Imaging Network Cancer Research Group (E1697). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:885‐892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C, et al. Pooled analysis of long‐term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1889‐1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eggermont AM, Chiarion‐Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1845‐1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luke JJ, Ott PA. PD‐1 pathway inhibitors: the next generation of immunotherapy for advanced melanoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:3479‐3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521‐2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Long GV, Schachter J, Ribas A, et al. 4‐Year survival and outcomes after cessation of pembrolizumab (pembro) after 2‐years in patients (pts) with ipilimumab (ipi)‐naive advanced melanoma in KEYNOTE‐006 [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(suppl):9503. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Poklepovic AS, Carvajal RD. Prognostic value of low tumor burden in patients with melanoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 2018;32:e90‐e96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Daud AI, Wolchok JD, Robert C, et al. Programmed death‐ligand 1 expression and response to the anti‐programmed death 1 antibody pembrolizumab in melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4102‐4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, et al. IFN‐gamma‐related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD‐1 blockade. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:2930‐2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cristescu R, Mogg R, Ayers M, et al. Pan‐tumor genomic biomarkers for PD‐1 checkpoint blockade‐based immunotherapy. Science. 2018;362:pii: eaar3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu J, Blake SJ, Yong MC, et al. Improved efficacy of neoadjuvant compared to adjuvant immunotherapy to eradicate metastatic disease. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:1382‐1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1789‐1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1824‐1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weber JS, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al. Adjuvant therapy with nivolumab (NIVO) versus ipilimumab (IPI) after complete resection of stage III/IV melanoma: updated results from a phase III trial (CheckMate 238) [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15 suppl):9502. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hauschild A, Dummer R, Schadendorf D, et al. Longer follow‐up confirms relapse‐free survival benefit with adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with resected BRAF V600‐mutant stage III melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3441‐3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M, et al. Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF‐mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1813‐1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF‐mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double‐blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:444‐451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dreno B, et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAF(V600)‐mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double‐blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1248‐1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Gogas HJ, et al. Encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients with BRAF‐mutant melanoma (COLUMBUS): a multicentre, open‐label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:603‐615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Long GV, Weber JS, Infante JR, et al. Overall survival and durable responses in patients with BRAF V600‐mutant metastatic melanoma receiving dabrafenib combined with trametinib. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:871‐878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Long GV, Flaherty KT, Stroyakovskiy D, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib versus dabrafenib monotherapy in patients with metastatic BRAF V600E/K‐mutant melanoma: long‐term survival and safety analysis of a phase 3 study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1631‐1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schadendorf D, Long GV, Stroiakovski D, et al. Three‐year pooled analysis of factors associated with clinical outcomes across dabrafenib and trametinib combination therapy phase 3 randomised trials. Eur J Cancer. 2017;82:45‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gibney GT, Messina JL, Fedorenko IV, Sondak VK, Smalley KS. Paradoxical oncogenesis—the long‐term effects of BRAF inhibition in melanoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:390‐399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coens C, Bottomley A, Blank CU, et al. Health‐related quality‐of‐life results for pembrolizumab versus placebo after complete resection of high‐risk stage III melanoma from the EORTC132‐MG/Keynote 054 trial: an international randomized double‐blind phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2018;26:442‐466. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eggermont AM, Chiarion‐Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high‐risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): a randomised, double‐blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:522‐530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Laway BA, Mir SA. Pregnancy and pituitary disorders: challenges in diagnosis and management. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:996‐1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. El Meliegy A, Motawi A, El Salam MAA. Systematic review of hormone replacement therapy in the infertile man. Arab J Urol. 2018;16:140‐147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Veras E, Kurman RJ, Wang TL, Shih IM. PD‐L1 Expression in human placentas and gestational trophoblastic diseases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2017;36:146‐153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Habicht A, Dada S, Jurewicz M, et al. A link between PDL1 and T regulatory cells in fetomaternal tolerance. J Immunol. 2007;179:5211‐5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hayashi Y, Nishiyama T, Nakatochi M, Suzuki S, Takahashi S, Sugiura‐Ogasawara M. Association of genetic variants of PD1 with recurrent pregnancy loss. Reprod Med Biol. 2018;17:195‐202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maleka A, Enblad G, Sjors G, Lindqvist A, Ullenhag GJ. Treatment of metastatic malignant melanoma with vemurafenib during pregnancy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e192‐e193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gastman BR, Gerami P, Kurley SJ, Cook RW, Leachman S, Vetto JT. Identification of patients at risk of metastasis using a prognostic 31‐gene expression profile in subpopulations of melanoma patients with favorable outcomes by standard criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:149‐157.e144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gartrell RD, Marks DK, Rizk EM, et al. Validation of Melanoma Immune Profile (MIP), a prognostic immune gene prediction score for stage II‐III melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:2494‐2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Leachman S, Covington KR, Cook RW, Monzon FA, Vetto JT. Implications of a 31‐gene expression profile (31‐GEP) test for cutaneous melanoma (CM) on AJCC‐based risk assessment and adjuvant therapy trial design. Paper presented at: the Society for Melanoma Research Fifteenth International Congress; October 24‐17, 2018; Manchester, England. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy guided by a 21‐gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:111‐121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Santiago‐Walker A, Gagnon R, Mazumdar J, et al. Correlation of BRAF mutation status in circulating‐free DNA and tumor and association with clinical outcome across four BRAFi and MEKi clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:567‐574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee RJ, Gremel G, Marshall A, et al. Circulating tumor DNA predicts survival in patients with resected high‐risk stage II/III melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:490‐496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Trucco LD, Mundra PA, Hogan K, et al. Ultraviolet radiation‐induced DNA damage is prognostic for outcome in melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:221‐224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]