Abstract

Despite the identification of several ovarian cancer (OC) predisposition genes, a large proportion of familial OC risk remains unexplained. We adopted a two‐stage design to identify new OC predisposition genes. We first carried out a large germline whole‐exome sequencing study on 158 patients from 140 families with significant OC history, but without evidence of genetic predisposition due to BRCA1/2. We then evaluated the potential candidate genes in a large case–control association study involving 381 OC cases in the Cancer Genome Atlas project and 27,173 population controls from the Exome Aggregation Consortium. Two new putative OC risk genes were identified, namely, ANKRD11, a putative tumor suppressor, and POLE, an enzyme involved in DNA repair and replication. These two genes likely confer moderate OC risk. We performed in vitro experiments and showed an ANKRD11 mutation identified in our patients markedly lowered the protein expression by compromising protein stability. Upon future validation and functional characterization, these genes may shed light on cancer etiology along with improving ascertainment power and preventive care of individuals at high risk of OC.

Keywords: gynecological cancer, hereditary ovarian cancer, cancer predisposition, cancer risk, whole‐exome sequencing

Short abstract

What's new?

Despite the identification of several ovarian cancer (OC) predisposition genes, familial OC risk largely remains unexplained. Here, the authors report the discovery of two new putative OC predisposition genes based on germline whole‐exome sequencing of 140 families with a strong OC family history but without known BRCA1/2 mutations. By comparing another 381 OC cases with more than 27,000 population controls, they show that the putative tumor suppressor ANKRD11 and POLE, an enzyme involved in DNA repair and replication, moderately increase OC risk. These genes may shed light on cancer etiology and improve ascertainment power of individuals at high OC risk.

Abbreviations

- CHX

cycloheximide

- ExAC

Exome Aggregation Consortium

- FOCR

Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry

- GWAS

genome‐wide association studies

- Indels

insertions and deletions

- MMR

mismatch repair

- OC

ovarian cancer

- OCAC

Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium

- OR

odds ratio

- SNVs

single nucleotide variants

- TCGA

the Cancer Genome Atlas project

- WES

whole‐exome sequencing

- WT

wild‐type

Introduction

Epithelial Ovarian cancer (OC) is the leading cause of death from gynecologic malignancies. The American Cancer Society estimated that in 2019 22,530 new OC cases will be diagnosed in the US and 13,980 would die from the disease. OC is known to have strong genetic predisposition with an estimated heritability of approximately 40%.1 A family history of OC is one of the strongest risk factors of the disease. Women with a family history of OC are 3.1‐fold more likely to develop this cancer.2 Studies in the past 15 years have discovered a number of high‐risk OC genes, such as BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, RAD51C, RAD51D and PMS2.3 Lifetime risk of OC is estimated to be 15–40% for women with deleterious mutations in BRCA1/2, compared to 1.4% for women in the general population.4, 5 However, mutations in BRCA1/2 can only explain 43% of excess familial risk6 and 5–10% of the total OC incidence.7 As a result, as much as 60% of OC familial risk remains unexplained,8 necessitating continuous efforts to discover new OC predisposition genes.

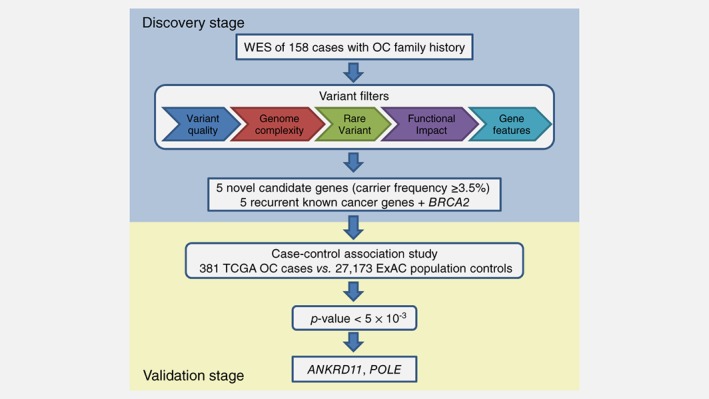

Recent efforts to identify additional OC predisposition genes came from large case–control genome‐wide association studies (GWAS),9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and targeted sequencing of candidate genes in case–control or case‐only cohorts.14, 15, 16 While GWAS offer systematic scan of the common genetic variants across the genome, the variants identified usually confer small increments in OC risks and reside in noncoding genomic regions, leaving the actual genes responsible for the signals undetermined. Targeted sequencing allows testing of rare variants, which are more likely to have larger effect size and direct functional consequence,17 in the genes of interest but leaves out most of the genes in the genome, and would miss genes not specified a priori. To overcome these limitations, we chose the whole‐exome sequencing (WES) approach and focused our studies on a high‐risk familial OC population from a large Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry (FOCR), where we expect an enriched pool of OC predisposition genes. Indeed, in a previous segregation analysis on 1919 pedigrees from FOCR,18 we found evidence supporting a dominant mode of segregation of susceptibility to OC and the existence of OC susceptibility genes beyond BRCA1, BRCA2 and MSH2. To maximize the likelihood of discovering new OC genes, we performed WES on FOCR participants from families that had not been screened for BRCA1/2 mutations or families that tested negative for deleterious mutations in those genes, and followed with a large case–control study to evaluate genes’ contribution to OC risk (Fig. 1). To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest WES study of hereditary OC families to date, and we report ANKRD11 and POLE as novel putative OC predisposition genes.

Figure 1.

The two‐stage study design. One novel candidate, TTC28, was excluded from case–control association study due to extremely low coverage of the gene in the matched normal WES data of TCGA OC cases. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Materials and Methods

Study population

The FOCR housed at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center (formerly known as the Gilda Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry) recruits families with two or more cases of OC, families with three or more cases of cancer on same side of family with at least one being OC, families with at least one female having two or more primary cancers and one of the primaries being OC, and families with two or more cases of cancer with at least one being OC diagnosed at an early age of onset (45 years old or younger).18 Families provide written informed consent under an institutional protocol CIC95‐27. Cases are verified by medical record and/or death certificate when required and a registry pathologist verifies stage and histology. The registry comprises 50,401 individuals including 5,614 OCs from 2,636 unique families. The 155 participants selected in our study had germline DNA samples available and previously tested negative for germline BRCA1/2 mutations (n = 134; 86.5%) or had not been subjected to genetic testing (n = 21; 13.5%). Genetic testing for BRCA1/2 in FOCR has been reported previously,18 except for 11 patients the genetic testing was done by Myriad. In addition, three early‐onset OC patients from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium (OCAC) were included.

Next‐generation sequencing and variant calling

Exome capture was performed using Agilent SureSelect Human All Exome v3 or v5 kit from the genomic DNA isolated from each individual. The captured DNA was sequenced using Illumina HiSeq to generate 100‐bp paired‐end reads. Raw sequence reads were aligned to the Human Reference Genome (NCBI Build 37) using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (BWA). After removing PCR duplicates using Picard, the GATK software was used for local realignment, base quality recalibration and variant calling of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions and deletions (indels). In the variant calling step, variants were first called in each sample separately, and then joint genotyping analysis was performed across all samples to generate analysis‐ready variants.

Variant filtering

Only biallelic variants were included in our analysis. Genotypes with read depth <3 were considered missing and variants with missing genotypes in >10% individuals were excluded. Long insertions and deletions (>10 bp) were also removed. Variants in segmental duplications of greater than 96% similarity were excluded due to high false positive rate of variant calling. To keep only rare variants, we excluded any variants with allele frequency >0.1% in non‐TCGA and non‐Finnish European population from the Exome Aggregation Consortium19 (ExAC) (exac03nontcga) as well as any variant in dbSNP129, the 1000 Genomes Project (2015 August release, EUR population), and the Exome Sequencing Project (ESP6500siv2, European American only). Variants that were not functionally important were filtered out, including nonexonic variants (except splicing variants), nonframeshift variants, synonymous variants and nonsynonymous variants that were predicted to be benign by all prediction methods,20 including SIFT, PolyPhen2, MutationTaster, LRT, MutationAssessor, FATHMM, RadialSVM and logistic regression (LR) score. ANNOVAR21 was used to facilitate these variant filtering steps. We further eliminated any variants in genes not expressed in breast or female reproductive system according to the Human Protein Atlas (http://www.proteinatlas.org; Data from http://v14.proteinatlas.org),22 and any variants in genes with residual variation intolerance score (RVIS) score23 ≥90th percentile unless the gene was a known cancer predisposition gene3 or a gene included in Cancer Gene Census.24 At the end, only the recurrent genes that were mutated in at least two families were kept for further analysis. Variants in the 11 genes selected for validation (including the five novel genes and six known cancer genes, Fig. 1) were manually inspected to ensure reliable variant calls.

Sanger sequencing

For each variant in the five novel candidate genes that was observed in our discovery cohort, we performed Sanger sequencing on all variant carriers and same number of randomly selected noncarriers.

Variant analysis in TCGA OC cohort

We selected 381 normal samples (“Blood Derived Normal” or “Solid Tissue Normal”) from TCGA self‐reported white OC cases that have been whole‐exome sequenced. We extracted their BAM files with restriction to the 11 gene regions from the Genomic Data Commons Data Portal. We performed variant calling and variant filtering as described above for our own WES data. Manual inspection was also employed for the observed variants in the 11 genes selected for validation.

Case–control association test

Variant sites in ExAC non‐TCGA samples (release 1) were obtained from the ExAC website. We included the variants that passed GATK quality filter and were observed in Non‐Finnish European population. These variants were filtered in the same way as described above for our discovery cohort and the TCGA OC cases to retain only rare and putatively functional variants. As individual‐level genotype data in ExAC are not available, we summed up mutant allele counts across all remaining variants in the same gene in the ExAC controls and compared them with values in the TCGA OC cases using two‐sided Fisher's exact test. Bonferroni correction was used to correct for testing multiple genes.

Somatic mutation burden in TCGA OC cohort

Somatic mutations were extracted from the high confidence set of somatic mutations in TCGA PanCanAtlas Ovarian Serous Cystadenocarcinoma data, which was downloaded from cBioPortal and contained only biallelic variants.25 Of the 381 TCGA OC patients, 345 had somatic mutation information available and therefore only these 345 patients were included in the analysis of somatic mutation burden. To identify carriers with somatic mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, ANKRD11 and POLE, we focused on rare and putatively functional somatic mutations. Variant filtering process was the same as described above for our own WES data, except that dbSNP database was not used for filtering here. We also required the somatic mutations to have allele frequency ≥10% in the corresponding tumor sample and were supported by at least three reads. Copy number alterations from GISTIC, which were also downloaded from cBioPortal, were used to locate OC patients with homozygous deletions in the above four genes in their tumors.

Characterization of ANKRD11 genetic variants

Flag‐tagged wild‐type (WT) or mutant cDNA constructs were cloned into pcDNA3.1 + C‐DYK vector (GenScript). The sequences of the constructs were confirmed by sequence analysis. WT or mutant constructs were cotransfected with GFP expressing vector construct into 293T cells with PolyJet™ In Vitro DNA Transfection Reagent (SL100688; SignaGen Laboratories, Rockville, MD) and cell lysates were harvested after 48 hr. The 293T cell line (ATCC® CRL‐3216™, RRID:CVCL_0063) was ordered from ATCC in 2018, which has been authenticated using STR profiling and was confirmed without mycoplasma contamination. The cell lysates were separated on SDS‐PAGE gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Burlington, MA). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk for 1 hr at room temperature, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The next day, the membranes were incubated with HRP conjugated anti‐rabbit or mouse secondary antibody (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA) for 1 hr. The proteins were detected using ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare, Philadelphia, PA). To investigate protein stability of ANKRD11‐K1461R, the WT or K1461R transfected cells were treated without or with 10 μg/ml eukaryote protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) and 10 μg/ml proteasome inhibitor MG‐132 for 1, 2 and 4 hr. Protein lysates were harvested and the immunoblot was further performed. Anti‐β‐Actin (#3700; 1:2000); anti‐GFP (#2950; 1:1000) from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA; anti‐Flag (MA191878; 1:500) from Invitrogen, Waltham, MA. The protein abundances were quantified using Image J software.

Study approval

The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data availability

Data are restricted due to ethical concerns in keeping with the institute's policies on germline variation data and the level of patient consent gained. Data are available from the Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry (ovarianregistry@roswellpark.org) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. The results published here are in part based upon data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas (dbGaP Study Accession: phs000178.v10.p8) managed by the NCI and NHGRI. Information about TCGA can be found at http://cancergenome.nih.gov.

Results

Study population in the discovery stage

We selected a discovery cohort that is likely enriched with unknown OC predisposition genes for WES. This cohort included a total of 158 cancer patients of European descent selected from 140 families with a family history of OC but without known BRCA1/2 mutations (see Materials and Methods), among which 152 were OC cases and six were breast cancer cases with family members diagnosed with OC. The median age onset is 49 and the number of OC cases within these families ranged from 1 to 6. Tumor characteristics were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the discovery cohort

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, years range (median) | 91–83 (49) | |

| Histology | ||

| Serous | 81 | (51.27%) |

| Endometrioid | 22 | (13.92%) |

| Clear cell | 9 | (5.70%) |

| Mucinous | 8 | (5.06%) |

| Other | 7 | (4.43%) |

| Unknown | 31 | (19.62%) |

| Stage | ||

| I | 33 | (20.89%) |

| II | 10 | (6.33%) |

| III | 42 | (26.58%) |

| IV | 3 | (1.90%) |

| Unknown | 70 | (44.30%) |

| Grade | ||

| 1 | 26 | (16.46%) |

| 2 | 26 | (16.46%) |

| 3 | 59 | (37.34%) |

| Unknown | 47 | (29.75%) |

The patient was diagnosed with germ cell ovarian cancer.

Established and novel candidate genes identified by WES of OC families

Variants from WES underwent rigorous filtering and we kept in our analysis the recurrent genes that harbored rare and putatively functional variants in at least two families (Fig. 1, see Materials and Methods). Among these genes, we observed three known OC predisposition genes: BRCA1, BRIP1 and MSH2, which were found mutated in 15 (9.49%), four (2.53%) and two (1.27%) cancer patients respectively. BRCA2 variant was only observed in one patient, which probably resulted from our explicit exclusion of known BRCA‐positive patients from our discovery cohort. Nevertheless, we included BRCA2 in our further analysis due to its importance in OC.

In addition to observing known OC risk genes, we observed two recurrent genes that have been implicated in other cancers, including POLE in colorectal cancer and EP300 in colorectal, breast and blood cancers.24 These two genes were both mutated at a frequency equal to BRIP1. The identification of known colorectal cancer genes in our study is intriguing as colorectal cancer is an established risk factor for OC.26, 27

To further identify novel candidates for OC predisposition gene, we prioritized genes that were more frequently mutated in these high‐risk patients. Candidates were selected using a stringent cutoff where genes were required to be mutated in at least 3.5% patients or families, which translated to six patients or five families. The cutoff was chosen to be aligned with what have been observed cumulatively for BRCA‐Fanconi anemia OC‐associated genes excluding BRCA1/2.15 Of the 13 genes meeting this criterion, five (TTC28, VPS13B, COL6A3, FREM2 and ANKRD11) were of particular interest as they have not been previously known as cancer predisposition genes but were implicated to involve in cancer (Table 2 and Supporting Information Table S1). Mutations in these novel genes occur at a frequency that is higher than many well‐known predisposition genes, such as BRIP1 and MSH2, in previous15, 16 and current study. Sanger sequencing (see Materials and Methods) confirmed observed variants in these five novel candidate genes.

Table 2.

The mutation frequency of known cancer genes, and OC predisposition candidate genes in the discovery cohort and TCGA OC cases

| Gene1 | Discovery cohort | TCGA OC cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of variants | Carriers (n = 158) (n, %) | Carrier families2 (n = 140) (n, %) | Number of variants | Carriers (n, %) | n total3 | ||||

| BRCA1 | 12 | 15 | 9.49% | 13 | 9.29% | 20 | 34 | 8.92% | 381 |

| TTC28 | 6 | 7 | 4.43% | 6 | 4.29% | – | – | – | – |

| FREM2 | 6 | 7 | 4.43% | 6 | 4.29% | 7 | 7 | 1.96% | 357 |

| VPS13B | 5 | 6 | 3.80% | 5 | 3.57% | 12 | 12 | 3.15% | 381 |

| COL6A3 | 6 | 5 | 3.16% | 5 | 3.57% | 12 | 11 | 3.08% | 357 |

| ANKRD11 | 5 | 5 | 3.16% | 5 | 3.57% | 13 | 13 | 3.64% | 357 |

| EP300 | 4 | 4 | 2.53% | 4 | 2.86% | 11 | 11 | 2.89% | 381 |

| POLE | 3 | 4 | 2.53% | 3 | 2.14% | 16 | 16 | 4.34% | 369 |

| BRIP1 | 3 | 4 | 2.53% | 3 | 2.14% | 3 | 3 | 0.79% | 381 |

| MSH2 | 2 | 2 | 1.27% | 2 | 1.43% | 6 | 7 | 1.84% | 381 |

| BRCA2 | 1 | 1 | 0.63% | 1 | 0.71% | 21 | 24 | 6.30% | 381 |

The novel OC predisposition candidate genes were in bold.

The families where the gene was mutated in at least one individual.

The samples with genotypes missed for all the variants of the corresponding gene were excluded.

Validation of candidate genes in case–control association study

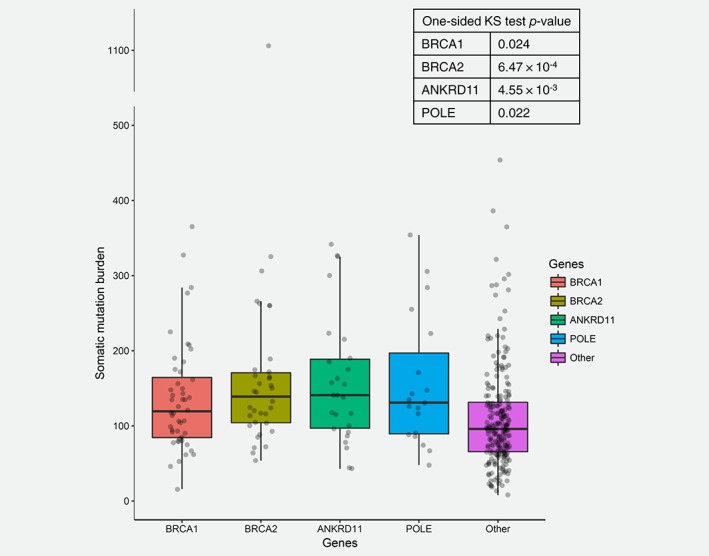

To evaluate the predisposition potential of these new genes, we compared the frequencies of rare and putatively functional germline variants in those genes between an independent OC cohort of 381 patients from the Cancer Genome Atlas project (TCGA) and 27,173 population controls from ExAC (see Materials and Methods). The OC cases used for validation included all self‐reported white OC cases from TCGA that had WES data from matched normal available. We assessed a total of 11 genes in this case–control study including all five novel genes along with the six known cancer genes (Fig. 1, Table 3 and Supporting Information Table S2). Due to extremely low coverage of the TTC28 gene region in TCGA WES data, this gene was excluded from the analysis and only 10 genes entered association testing. Four genes (BRCA1, BRCA2, ANKRD11 and POLE) were found to carry significantly more mutant alleles in TCGA OC cases than in controls (Bonferroni corrected p‐value <0.05). The two new putative OC predisposition genes, ANKRD11 and POLE, conferred moderate risk to OC with odds ratio (OR) 2.95 and 2.69, respectively. Interestingly, in the TCGA OC cohort, we observed that the patients carrying germline mutations in these two genes tend to have higher somatic mutation burden (Supporting Information Fig. S1, one‐sided p‐value based on Kolmogorov–Smirnov test = 0.1 and 0.111 for ANKRD11 and POLE, respectively), a pattern that has been documented for BRCA1 and BRCA2 in OC.28 The trend became statistically significant after we included the carriers with somatic mutations or homozygous deletions in their tumor samples (Fig. 2, one‐sided p‐value based on Kolmogorov–Smirnov test = 4.55 × 10−3 and 0.022 for ANKRD11 and POLE, respectively).

Table 3.

Comparison of mutant allele frequency in case–control association study

| Gene1 | TCGA OC cases | ExAC population controls2 | OR | p‐value3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total chr count4 | Allele frequency | Allele count | Total chr count | Allele frequency | |||

| BRCA1 | 762 | 4.46% | 245 | 54,346 | 0.45% | 10.31 | 7.22E−22 |

| TTC28 | – | – | 47 | 5,400 | 0.87% | – | – |

| FREM2 | 714 | 0.98% | 592 | 54,346 | 1.09% | 0.90 | 1.00 |

| VPS13B | 762 | 1.57% | 600 | 54,346 | 1.10% | 1.43 | 0.22 |

| COL6A3 | 714 | 1.54% | 651 | 54,346 | 1.20% | 1.29 | 0.38 |

| ANKRD11 | 714 | 1.82% | 339 | 54,346 | 0.62% | 2.95 | 7.92E−04 |

| EP300 | 762 | 1.44% | 393 | 54,346 | 0.72% | 2.01 | 2.99E−02 |

| POLE | 738 | 2.17% | 444 | 54,346 | 0.82% | 2.69 | 5.71E−04 |

| BRIP1 | 762 | 0.39% | 135 | 54,346 | 0.25% | 1.59 | 0.44 |

| MSH2 | 762 | 0.92% | 161 | 54,346 | 0.30% | 3.12 | 9.19E−03 |

| BRCA2 | 762 | 3.15% | 349 | 54,346 | 0.64% | 5.03 | 7.26E−10 |

The novel OC predisposition candidate genes were in bold. Genes were in the same order as in Table 2.

Variants were from Non‐Finnish European population of ExAC with samples from TCGA excluded.

Fisher exact test p‐value for comparing allele counts between OC cohort and ExAC. p values that were statistically significant after Bonferroni correction for 10 genes (p‐value <5 × 10−3) are in bold.

The samples with genotypes missed for all the variants of the corresponding gene were excluded.

Figure 2.

Somatic mutation burden in TCGA OC cohort. The number of somatic mutations in patients who either carried germline mutations or carried somatic mutations or homozygous deletions in their tumor samples in each of the four genes was compared to patients that did not carry mutations or homozygous tumor deletions in any of the four genes (Other) using Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Functional evaluation of ANKRD11 variants

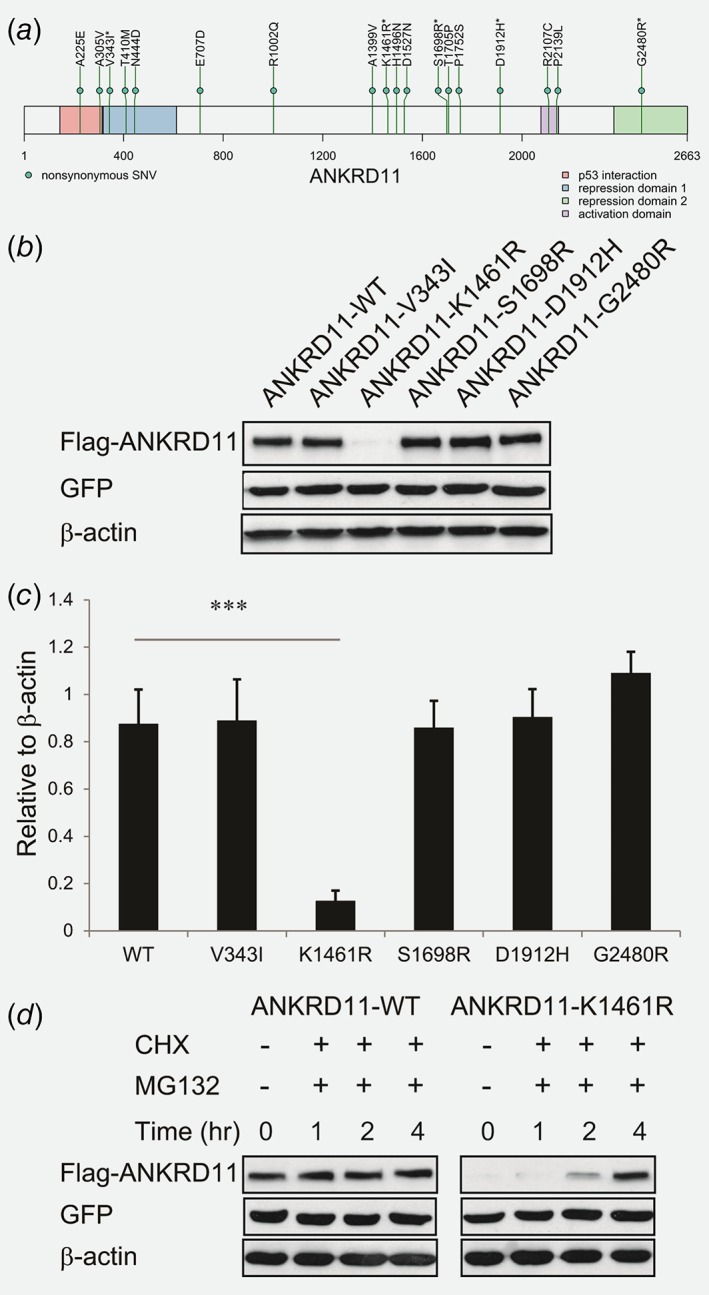

To test whether the rare and putatively functional variants in the new cancer disposition gene ANKRD11 have any effects on protein abundance, we selected the five variants identified in our discovery cohort (Fig. 3 a, Supporting Information Table S2) and evaluated their effects on protein expression by transient transfection of the WT or mutant constructs into 293T cells. All five ANKRD11 variants were predicted by in silico bioinformatics programs to be deleterious to protein stability or function (Supporting Information Table S3). We found that one variant (K1461R) markedly reduced ANKRD11 protein level (Figs. 3 b and 3 c). This is caused by the mutant ANKRD11 protein being unstable and rapidly degraded, as we observed increased protein level after inhibiting protein degradation with proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 3 d).

Figure 3.

Characterization of ANKRD11 variants. (a) The ANKRD11 variants we identified in our discovery cohort (denoted by *) and TCGA OC cohort. (b) Immunoblot analyses were performed with anti‐Flag, anti‐GFP and anti‐β‐Actin antibodies. The samples are lysates from 293T cells co‐transfected with the ANKRD11‐WT or ANKRD11 variant containing constructs and GFP expressing vector. β‐Actin was used as the loading control. (c) Quantification of ANKRD11 immunoblot band intensity relative to loading control using ImageJ. All the experiments were performed in triplicates. Error bars represent SD; ***p < 0.001 by two‐tailed Student's t‐test. (d) Immunoblot analyses were performed with anti‐Flag, anti‐GFP and anti‐β‐Actin antibodies. The samples are lysates from 293T cells co‐transfected with the ANKRD11‐WT or ANKRD1‐K1461R containing construct and GFP expressing vector. The transfected cells were treated with 10 μg/ml CHX and 10 μg/ml MG‐132 for 1, 2 and 4 hr. β‐Actin was used as the loading control. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Discussion

We identified two new genes, ANKRD11 and POLE, that carry significantly increased OC risk when compared to population controls in ExAC. ANKRD11 has previously been found to be a potential tumor suppressor.29, 30 It falls within the loss of heterozygosity region in 16q24.3 in breast cancer, which occurs in at least half of all breast tumors.29 ANKRD11 is a coactivator and a target gene of P53 and it enhances P53 transcriptional activity through increased acetylation of P53.29 ANKRD11 can also suppress the oncogenic potential of P53 Gain‐Of‐Function mutant.30 ANKRD11 expression was found lower in breast tumor tissues and breast cancer cell lines when compared to normal breast tissues or nonmalignant immortalized breast epithelial cells.29, 30, 31 Restoring ANKRD11 expression in breast cancer cell lines can suppress tumor cell growth in the presence of P53 that can bind DNA.29 While previous studies focused on breast cancer, our study found ANKRD11 to increase risk of OC with an OR of 2.56–2.95. We selected the five ANKRD11 variants observed in our patients for functional evaluation and found one abolish ANKRD11 protein abundance, which pointed to the possibility that reduced ANKRD11 protein level contributes to OC onset, consistent with prior observed effect of ANKRD11 level in breast cancer.29, 30, 31 Further functional experiment will be needed to characterize the effect of other deleterious ANKRD11 variants such as G2480R, which sits in the C‐terminal of ANKRD11 responsible for signaling ANKRD11 degradation,32 as well as to investigate their potential functional consequence on cell proliferation, invasion and migration in order to understand the mechanism underneath the observed increased risk of OC.

POLE encodes the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase epsilon. It is involved in DNA repair and chromosomal DNA replication. POLE is considered a colorectal cancer predisposition gene3, 33 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend colonoscopy every 2–3 years to individuals carrying POLE mutations, even though its precise risk in colorectal cancer has not been estimated yet. Our finding is consistent with recent findings that POLE mutations can contribute to susceptibility to a broad cancer spectrum including OC.34, 35 Furthermore, it has also been reported that POLE‐mutant endometrial and colorectal tumors had a high somatic mutation burden, elevated expression of immune checkpoint genes and increased lymphocytic infiltration,36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 and therefore immune checkpoint inhibitors was recommended for treating cancers with POLE‐mutations.41, 44 Similar recommendation was also demonstrated in mismatch repair (MMR) deficient cancers regardless of the cancers’ tissue of origin.45 In this phase II clinical trial, clinical benefit was observed in 53% patients, half of whom also carried germline mutations in MMR genes. Under the hypothesis that patients with germline POLE‐mutations can benefit from immune checkpoint blockade, it might be beneficial to offer OC patients with gene panel testing including POLE, which could help to determine the best treatment options for them.

In support of this, we observed a trend of higher somatic mutation burden in OC patients with germline ANKRD11 and POLE‐mutations. This finding is consistent with what has been observed in endometrial and colorectal tumors with somatic POLE‐mutations.40, 42, 43 In addition, it might also raise the beneficial potential of including POLE in gene panel testing of OC patients and their family members in order to optimize the prevention strategies to decrease their risk of OC and colorectal cancer. We noticed POLE variants were more prevalent in the TCGA OC cohort than in our discovery cohort (4.34% vs. 2.53% in Table 2). As the TCGA cohort included mostly sporadic OC while our cohort is enriched with familial OC, it might imply a likely stronger contribution of POLE to sporadic OC than familial OC.

We attempted to further validate ANKRD11 and POLE using the large GWAS datasets of OC cases and controls of the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium (OCAC).9 However because the very rare variants observed in our WES study were missing in genotyping/imputation data, the OCAC data was not suitable for validating our findings.

There are limitations to our study. When we estimated the OC risk conveyed by each gene, we took advantage of the existing variant data from ExAC population controls. We acknowledge that cancer status in ExAC individuals was not fully characterized and the ExAC data was generated separately from our study. A strict case–control study by targeted sequencing of the genes in both OC patients and cancer‐free controls would be necessary in the future. However, the sample size of such study is likely to be significantly less than ExAC. Despite these limitations, the ExAC data has been commonly used and validated as an effective control dataset for estimating cancer risk for both known15, 46, 47, 48 and newly discovered cancer predisposition genes/loci.49, 50

In summary, we conducted the largest WES study of hereditary OC to date and followed with a validation study to identify ANKRD11 and POLE as two possible OC predisposition genes. Identification of additional OC predisposition genes can potentiate ascertainment power and preventive care of individuals with high OC risk. Future follow‐up studies including additional sequencing and functional experiments are warranted to confirm these findings.

Author contributions

Study concept and manuscript writing: Zhu Q, Zhang J, Odunsi KO. Functional experiment analysis: Zhang J, Chen Y, Shen H, Huang R‐Y. WES data analysis: Zhu Q, Hu Q, Liu Q, Long M, Battaglia S, Liu S. FOCR samples and clinical data: Huang R‐Y, Kaur J, Eng KH, Lele SB, Zsiros E, Villella J, Lugade A, Moysich K. Interpretation of data: Zhu Q, Zhang J, Yao S, Liu S, Moysich K, Odunsi KO. Final review and approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Supporting information

Table S1 The involvement of the five novel candidate genes in cancer from literature.

Table S2 The rare and putatively functional variants of the 11 selected genes that were observed in our study.

Table S3 The bioinformatics predictions on the functional impacts of the five ANKRD11 variants observed in our discovery cohort.

Figure S1 Somatic mutation burden in TCGA OC cohort. The number of somatic mutations in patients who carried germline mutations in each of the four genes was compared to patients that did not carry germline mutations in any of the four genes (Other) using Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry participants, donors and past researchers. This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers U24CA232979, P50CA159981, R01 CA207504, and P30CA016056 as well as the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG‐14‐214‐01‐TBE and the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation. The results published here are in part based upon data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas (dbGaP Study Accession: phs000178.v10.p8) managed by the NCI and NHGRI. Information about TCGA can be found at http://cancergenome.nih.gov.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Contributor Information

Qianqian Zhu, Email: qianqian.zhu@roswellpark.org.

Jianmin Zhang, Email: jianmin.zhang@roswellpark.org.

Kunle O. Odunsi, Email: kunle.odunsi@roswellpark.org.

References

- 1. Schildkraut JM, Risch N, Thompson WD. Evaluating genetic association among ovarian, breast, and endometrial cancer: evidence for a breast/ovarian cancer relationship. Am J Hum Genet 1989;45:521–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stratton JF, Pharoah P, Smith SK, et al. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of family history and risk of ovarian cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:493–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rahman N. Realizing the promise of cancer predisposition genes. Nature 2014;505:302–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. PDQ® Cancer Genetics Editorial Board . Genetics of Breast and Ovarian Cancer (PDQ®)—Health Professional Version. PDQ® Cancer Information Summary. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Cancer Institute . SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gayther SA, Russell P, Harrington P, et al. The contribution of Germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to familial ovarian cancer: no evidence for other ovarian cancer–susceptibility genes. Am J Hum Genet 1999;65:1021–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daly MB, Axilbund JE, Buys S, et al. Genetic/familial high‐risk assessment: breast and ovarian. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 2010;8:562–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bahcall O. Common variation and heritability estimates for breast, ovarian and prostate cancers. Nat Genet 2013. Available from: https://www.nature.com/icogs/primer/commonvariation-and-heritability-estimates-for-breast-ovarian-and-prostate-cancers/ [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pharoah PD, Tsai YY, Ramus SJ, et al. GWAS meta‐analysis and replication identifies three new susceptibility loci for ovarian cancer. Nat Genet 2013;45:362–70. 70e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Phelan CM, Kuchenbaecker KB, Tyrer JP, et al. Identification of 12 new susceptibility loci for different histotypes of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Genet 2017;49:680–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuchenbaecker KB, Ramus SJ, Tyrer J, et al. Identification of six new susceptibility loci for invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Genet 2015;47:164–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen K, Ma H, Li L, et al. Genome‐wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for epithelial ovarian cancer in Han Chinese women. Nat Commun 2014;5:4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Couch FJ, Wang X, McGuffog L, et al. Genome‐wide association study in BRCA1 mutation carriers identifies novel loci associated with breast and ovarian cancer risk. PLoS Genet 2013;9:e1003212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Walsh T, Casadei S, Lee MK, et al. Mutations in 12 genes for inherited ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinoma identified by massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:18032–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Norquist BM, Harrell MI, Brady MF, et al. Inherited mutations in women with ovarian carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:482–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ramus SJ, Song H, Dicks E, et al. Germline mutations in the BRIP1, BARD1, PALB2, and NBN genes in women with ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107:djv214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu Q, Ge D, Maia Jessica M, et al. A genome‐wide comparison of the functional properties of rare and common genetic variants in humans. Am J Hum Genet 2011;88:458–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tayo BO, DiCioccio RA, Liang Y, et al. Complex segregation analysis of pedigrees from the Gilda Radner familial ovarian cancer registry reveals evidence for Mendelian dominant inheritance. PLoS One 2009;4:e5939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein‐coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016;536:285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu X, Jian X, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP: a lightweight database of human nonsynonymous SNPs and their functional predictions. Hum Mutat 2011;32:894–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high‐throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, et al. Proteomics. Tissue‐based map of the human proteome. Science 2015;347:1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Petrovski S, Gussow AB, Wang Q, et al. The intolerance of regulatory sequence to genetic variation predicts gene dosage sensitivity. PLoS Genet 2015;11:e1005492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:177–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2012;2:401–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cramer DW, Hutchison GB, Welch WR, et al. Determinants of ovarian cancer risk. I. Reproductive experiences and family History23. J Natl Cancer Inst 1983;71:703–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tung K‐H, Goodman MT, Wu AH, et al. Aggregation of ovarian cancer with breast, ovarian, colorectal, and prostate cancer in first‐degree relatives. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:750–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu C, Xie M, Wendl MC, et al. Patterns and functional implications of rare germline variants across 12 cancer types. Nat Commun 2015;6:10086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neilsen PM, Cheney KM, Li C‐W, et al. Identification of ANKRD11 as a p53 coactivator. J Cell Sci 2008;121:3541–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noll JE, Jeffery J, Al‐Ejeh F, et al. Mutant p53 drives multinucleation and invasion through a process that is suppressed by ANKRD11. Oncogene 2012;31:2836–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lim SP, Wong NC, Suetani RJ, et al. Specific‐site methylation of tumour suppressor ANKRD11 in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:3300–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walz K, Cohen D, Neilsen PM, et al. Characterization of ANKRD11 mutations in humans and mice related to KBG syndrome. Hum Genet 2015;134:181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Palles C, Cazier J‐B, Howarth KM, et al. Germline mutations affecting the proofreading domains of POLE and POLD1 predispose to colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Nat Genet 2013;45:136–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hansen MF, Johansen J, Bjornevoll I, et al. A novel POLE mutation associated with cancers of colon, pancreas, ovaries and small intestine. Fam Cancer 2015;14:437–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rohlin A, Zagoras T, Nilsson S, et al. A mutation in POLE predisposing to a multi‐tumour phenotype. Int J Oncol 2014;45:77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hussein YR, Weigelt B, Levine DA, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of endometrial carcinomas harboring somatic POLE exonuclease domain mutations. Mod Pathol 2015;28:505–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Gool IC, Eggink FA, Freeman‐Mills L, et al. POLE proofreading mutations elicit an antitumor immune response in endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:3347–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bellone S, Centritto F, Black J, et al. Polymerase epsilon (POLE) ultra‐mutated tumors induce robust tumor‐specific CD4+ T cell responses in endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 2015;138:11–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Howitt BE, Shukla SA, Sholl LM, et al. Association of polymerase e‐mutated and microsatellite‐instable endometrial cancers with Neoantigen load, number of tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes, and expression of PD‐1 and PD‐L1. JAMA Oncol 2015;1:1319–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network , Kandoth C, Schultz N, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013;497:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mehnert JM, Panda A, Zhong H, et al. Immune activation and response to pembrolizumab in POLE‐mutant endometrial cancer. J Clin Invest 2016;126:2334–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Temko D, Van Gool IC, Rayner E, et al. Somatic POLE exonuclease domain mutations are early events in sporadic endometrial and colorectal carcinogenesis, determining driver mutational landscape, clonal neoantigen burden and immune response. J Pathol 2018;245:283–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Castellucci E, He T, Goldstein DY, et al. DNA polymerase ɛ deficiency leading to an ultramutator phenotype: a novel clinically relevant entity. Oncologist 2017;22:497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bhangoo MS, Boasberg P, Mehta P, et al. Tumor mutational burden guides therapy in a treatment refractory POLE‐mutant uterine carcinosarcoma. Oncologist 2018;23:518–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. Mismatch‐repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD‐1 blockade. Science 2017;357:409–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Slavin TP, Maxwell KN, Lilyquist J, et al. The contribution of pathogenic variants in breast cancer susceptibility genes to familial breast cancer risk. NPJ Breast Cancer 2017;3:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, et al. Inherited DNA‐repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:443–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Couch FJ, Shimelis H, Hu C, et al. Associations between cancer predisposition testing panel genes and breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1190–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Neidhardt G, Hauke J, Ramser J, et al. Association between loss‐of‐function mutations within the FANCM gene and early‐onset familial breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1245–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chan CHT, Munusamy P, Loke SY, et al. Identification of novel breast cancer risk loci. Cancer Res 2017;77:5428–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 The involvement of the five novel candidate genes in cancer from literature.

Table S2 The rare and putatively functional variants of the 11 selected genes that were observed in our study.

Table S3 The bioinformatics predictions on the functional impacts of the five ANKRD11 variants observed in our discovery cohort.

Figure S1 Somatic mutation burden in TCGA OC cohort. The number of somatic mutations in patients who carried germline mutations in each of the four genes was compared to patients that did not carry germline mutations in any of the four genes (Other) using Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test.

Data Availability Statement

Data are restricted due to ethical concerns in keeping with the institute's policies on germline variation data and the level of patient consent gained. Data are available from the Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry (ovarianregistry@roswellpark.org) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. The results published here are in part based upon data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas (dbGaP Study Accession: phs000178.v10.p8) managed by the NCI and NHGRI. Information about TCGA can be found at http://cancergenome.nih.gov.