Abstract

Difficulty breathing due to tracheal stenosis (i.e., narrowed airway) diminishes the quality of life and can potentially be life-threatening. Tracheal stenosis can be caused by congenital anomalies, external trauma, infection, intubation-related injury, and tumors. Common treatment methods for tracheal stenosis requiring surgical intervention include end-to-end anastomosis, slide tracheoplasty and/or laryngotracheal reconstruction. Although the current methods have demonstrated promise for treatment of tracheal stenosis, a clear need exists for the development of new biomaterials that can hold the trachea open after the stenosed region has been surgically opened, and that can support healing without the need to harvest autologous tissue from the patient. The current study therefore evaluated the use of electrospun nanofiber scaffolds encapsulating 3D-printed PCL rings to patch induced defects in rabbit tracheas. The nanofibers were a blend of polycaprolactone (PCL) and polylactide-co-caprolactone (PLCL), and encapsulated either the cell adhesion peptide, RGD, or antimicrobial compound, ceragenin-131 (CSA). Blank PCL/PLCL and PCL were employed as control groups. Electrospun patches were evaluated in a rabbit tracheal defect model for 12 weeks, which demonstrated re-epithelialization of the luminal side of the defect. No significant difference in lumen volume was observed for the PCL/PLCL patches compared to the uninjured positive control. Only the RGD group did not lead to a significant decrease in the minimum cross-sectional area compared to the uninjured positive control. CSA reduced bacteria growth in vitro, but did not add clear value in vivo. Adequate tissue in-growth into the patches and minimal tissue overgrowth was observed inside the patch material. Areas of future investigation include tuning the material degradation time to balance cell adhesion and structural integrity.

Keywords: Tracheal Stenosis, Trachea reconstruction, Electrospinning, Nanofibers, RGD, Ceragenin, CSA-131

1. Introduction

Tracheal stenosis is a severe condition characterized by narrowing of the airway that can greatly affect the patient’s quality of life.1, 37 If the issue worsens, the condition may require surgical intervention or become fatal. Tracheal stenosis can be caused by a various number of potential reasons including congenital anomalies, external trauma, infection, intubation-related injury, and tumors. An estimated 1 in 200,000 people will develop tracheal stenosis from post-intubation related issues.29 Other studies have estimated the incidence rate of tracheal stenosis after intubation at approximately 4.6%.31 Treatment of severe tracheal stenosis is commonly accomplished using end-to-end anastomosis, slide tracheoplasty, and/or laryngotracheal reconstruction.9 End-to-end anastomosis is generally used for short segment defects where the section of trachea can be easily resected and the two ends reconnected.17 Slide tracheoplasty is used for long segment defects of the trachea, in which the trachea is divided into two sections, the sections are incised length-wise, and fitted together such that the length is shortened and the circumference increased.11, 40 Another option for long segment defects is laryngotracheal reconstruction, which relies on harvested autologous tissue to augment the airway, where buccal mucosa, fascia, pericardium, and rib cartilage is commonly used.7, 9 Autograft tissue collection can be painful for the patient, cause donor site morbidity, and also difficult for the surgeon to harvest and manipulate to the correct shape to fit the defect.15 Treatment of pediatric tracheal stenosis can be further complicated as the available tissue is less abundant and harder to manipulate.19

An off-the-shelf tracheal patch capable of replacing the need for prior tissue harvest would be highly advantageous for use in the treatment of tracheal stenosis as it would eliminate the secondary surgery and donor site morbidity issues. Various biomaterials have been proposed for tracheal reconstruction including decellularized allogenic tissues, synthetic polymers, natural materials, and combination materials (e.g., collagen-coated polypropylene mesh).2, 8, 10, 12, 18, 27, 35, 45 Different fabrication methods have been employed for the creation of trachea replacements including the use of 3D printing to create an exact patient match and/or the use bioreactors to generate tissue similar to the native trachea.43, 46 The use of methods like 3D printing and/or bioreactor pre-culture have demonstrated promise for the creation of trachea tissue, and may be preferable for certain indications; however, the time and cost required to create these specialty implants may not be feasible for all cases presented in the clinic.13 Electrospinning is a popular method for the fabrication of replacement tracheal tissue capable of creating aligned synthetic nanofibers in the shape of the native structure.3, 34, 35 The electrospun nanofibers can encapsulate or be modified with various molecules or proteins to enhance performance characteristics like antimicrobial activity, cell adhesion, and directed cell differentiation.20-23, 25, 28, 41, 42

In the current study, electrospun patches of polycaprolactone (PCL) and PLCL encapsulating 3D-printed PCL rings were fabricated and implanted into an in vivo rabbit tracheal defect model. Distinct, encapsulated 3D-printed rings provided structural support (i.e., preventing structural collapse) and protection of the trachea defect during healing. In addition, the cell adhesion peptide, RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp), or antimicrobial compound, ceragenin-131,33 was added to the electrospinning solutions for enhanced cell adhesion or antimicrobial activity, respectively. The use of an electrospun matrix represents a next-generation biomaterial from our previous work that used electrospun PCL nanofibers encapsulating 3D-printed PCL rings in an in vivo ovine trachea defect model.39 From the previous study, in which the implanted PCL patches resulted in tracheal stenosis, three main strategies were developed to decrease potential stenosis and lead to better overall tissue integration. A faster material degradation rate, improving cell adhesion, and introducing antimicrobial activity were selected as three potential solutions that could improve outcomes. Therefore, the four groups employed in the current in vivo rabbit animal study were 1) the PCL only group (baseline comparator group), 2) the faster degrading material PCL/PLCL, 3) PCL/PLCL with the embedded antimicrobial compound ceragenin-131 (PCL/PLCL+CSA), and 4) PCL/PLCL with the cell adhesion peptide RGD (PCL/PLCL+RGD).

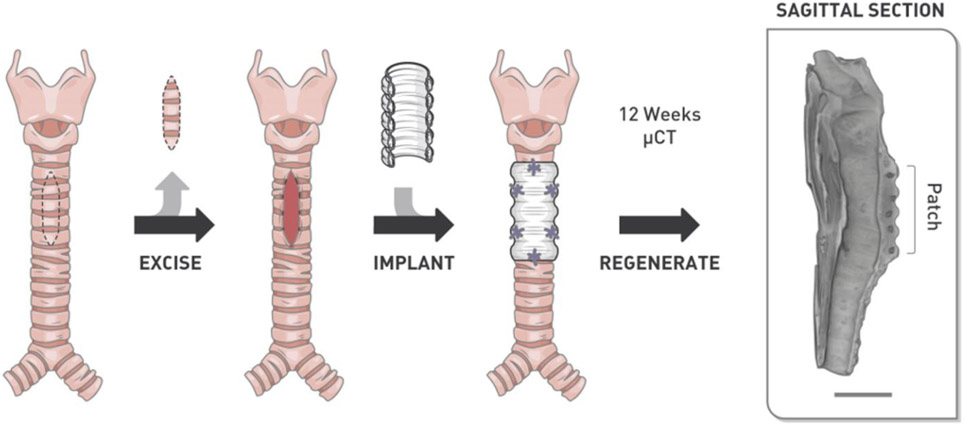

Electrospun nanofibers were first characterized to determine the degradation rate and cell viability. The patch containing CSA was additionally evaluated for antimicrobial activity. Electrospun patches were then implanted into a rabbit tracheal defect model and evaluated after 12 weeks of recovery (Fig. 1). Explanted tracheas were analyzed using microcomputed tomography to determine the patency volume, average/minimum cross-sectional area, and histology to evaluate tissue integration into the patch. The hypothesis was that a faster degrading patch would lead to better overall tissue integration, minimal stenosis, and the addition of antimicrobial compounds or cell adhesion peptides would help to further improve tissue regeneration.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the surgical procedure employed in the current study. A portion of trachea was excised and an electrospun nanofiber patch with impregnated 3D-printed rings was used to patch the defect. Trachea regeneration was evaluated after 12 weeks using micro-computed tomography (μCT) and histology to evaluate regeneration. Scale bar = 10 mm.

2. Materials and Methods

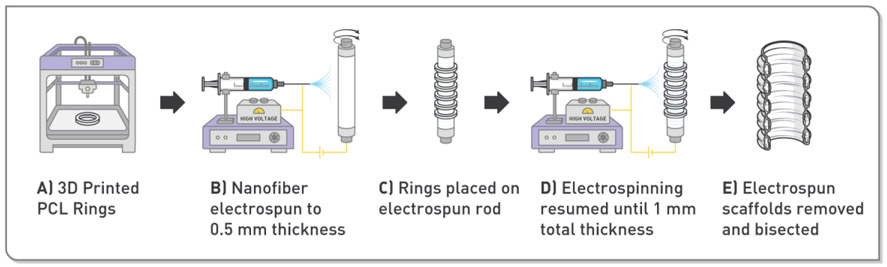

3D-Printed Ring Fabrication

3D-printed ring reinforcements for the electrospun patch were fabricated with polycaprolactone (PCL) filament (Mw = 50,000 g/mol, 3D4MAKERS, Haarlem, The Netherlands) using a LulzBot TAZ 6 (Aleph Objects, Loveland, CO) printer (Fig. 2A). The rings were designed with the 3D computer-aided design software (SolidWorks, Dassault Systémes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France) to have an inner diameter of 8 mm and ring cross-section of 0.75 mm in diameter. The 3D model was then converted into G-code using open-source slicing software (Cura, Dynamism, Inc., Chicago, IL) and printed.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the scaffold fabrication method employed in the current study. A) Polycaprolactone rings were fabricated using a 3D printer. B) A rotating mandrel was pre-coated with electrospun nanofibers to a thickness of 0.5 mm. C) The 3D-printed rings were affixed to the pre-coated mandrel. D) Electrospinning was resumed to embed the rings in the scaffold at a final thickness of 1 mm. E) Finally, the scaffold was removed and bisected lengthwise to create the final patch.

Electrospun Patch Fabrication

Electrospinning was accomplished using a custom-built setup consisting of a Glassman High Voltage power supply (XP Power, Singapore) and New Era syringe pump (New Era Pump Systems, Inc., Farmingdale, NY). Polycaprolactone (PCL, Mw = 80,000, Wuhan Pensieve Technology Limited, Wuhan, China) and Poly(L-lactide-co-Caprolactone) (PLCL, Purasorb® PLC 7015, Corbion, Lenexa, KS) scaffolds were created by simultaneous electrospinning of 6 wt% PCL and 5 wt% PLCL (Fig. 2B). The PCL and PLCL were separately dissolved in hexafluoroisopropanol and stirred with a magnetic stir bar for a minimum of 3 hours at room temperature. For the RGD groups, RGD (GCGYGRGDSPG, GenScript, Nanjing, China) was added to PCL and PLCL polymer solutions in a controlled ratio to achieve final molar concentrations of 1, 3, 5, and 10 mM in the electrospun nanofibers. The RGD concentration range was selected after reviewing work from other groups using RGD in various applications.4, 5, 23, 32, 44 For the CSA groups, Ceragenin-131 (CSA) was added to PLCL and PCL solutions in a controlled ratio to achieve final molar concentrations of 1.2, 3.5, 6, and 12 mM in the electrospun nanofiber. CSA concentrations were experimentally evaluated to determine an appropriate range for evaluation in the current study.

Using separate syringes for the PCL solution and the PLCL solution, both solutions were simultaneously electrospun onto an 8.6 mm diameter rotating mandrel (100 revolutions per minute) positioned 200 mm from the syringe tips with a +25 kV charge applied. The PCL solution was dispensed at 4.17 mL/hour while the PLCL solution was dispensed at 5.0 mL/hour to create electrospun PCL/PLCL scaffolds with a PCL:PLCL polymer weight ratio of 1:1. Three groups were produced in this manner: a polymer only group, one with the RGD additive, and one with the CSA additive. The PCL group was produced using two syringes of the PCL polymer solution without RGD or CSA additives. After electrospun nanofibers were deposited onto the mandrel to approximately 0.5 mm in thickness, the 3D-printed PCL support rings were placed around the fiber-coated mandrel, spaced 3 mm apart from ring center to center (Fig. 2C). 3D-printed PCL rings were adhered to the scaffold by coating the rings with the PLCL solution prior to placement. Electrospinning was then resumed until a final wall thickness of 1 mm was achieved (Fig. 2D). The scaffold was then removed from the mandrel, cut into approximately 20 mm sections, then bisected lengthwise (Fig. 2E). The patches were then placed into Tyvek pouches and sterilized using ethylene oxide gas (AN74i, Anderson Anprolene, Haw River, NC).

Degradation Study

PCL or PCL/PLCL nanofibers were electrospun onto a rotating mandrel to an approximate thickness of 180 μm. The nanofibers were punched into a dogbone shape using an ASTM D638-5 punch with a gauge region of 9.53 x 3.175 mm. Electrospun nanofiber strips were submerged in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated at 37°C over the course of 12 weeks. At time points of 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks, samples were mechanically tested to failure in tension (n=5 per timepoint) using a MultiTest 5-i mechanical tester equipped with a 250 N load cell (Mecmesin, United Kingdom). Samples were positioned for tensile testing using screw side-action grips and pulled at a constant rate of 50 mm per minute (0.83% strain per second) at room temperature. The ultimate tensile strength (UTS) was recorded as the maximum stress, and the strain was recorded at the UTS. The Young’s modulus was calculated as the slope of the linear region of the stress-strain profile. Stress values were calculated using the initial cross-sectional area according to ASTM D638-5. Over the 12-week study, PCL and PCL/PLCL maintained their general shape and did not completely degrade over the course of the 12-week study.

Cell Adhesion

Rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (rMSCs, Sprague Dawley, ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA) were cultured in minimum essential medium-α (MEMα) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Culture medium was exchanged every 48 hours and cells were cultured until a passage of 2 before used in the cell adhesion study. Electrospun nanofibers were produced as previously described in the “Electrospun Patch Fabrication” section with or without RGD or CSA then punched into 6 mm diameter discs. The electrospun discs were affixed to the bottom of a black 96 well plate using medical silicone adhesive (A-100, Factor II, Inc., Lakeside, AZ) and allowed to dry for 24 hours. The 96 well plates containing the affixed nanofiber discs were then sterilized using ethylene oxide gas prior to cell seeding. Under sterile conditions, rMSCs were suspended in supplemented MEMα to a concentration of 66,666 cells/mL and 150 μL of this suspension was added to the wells containing the nanofiber discs (10,000 cells per well). Cells were then incubated for 24 hours to allow the cells to adhere to the nanofibers. After the 24 hour time point, the medium was aspirated and the nanofiber discs were gently washed twice with phosphate buffered saline. Cells were then stained with Live/Dead reagent (2 mM Calcein AM, 4 mM ethidium homo-dimer-1, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 20 minutes and then analyzed according to the manufacturer’s protocol with a Biotek Cytation 5 (Winooski, VT) plate reader.

Antimicrobial Activity

Escherichia Coli (E. coli, Dh5α strain) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (strain 262, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were grown in lysogeny broth (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L NaCl, Sigma-Aldrich) and brain heart infusion (37 g/L BD Bacto™ Brain Heart Infusion, Thermo Fisher Scientific) media, respectively. The choice of Streptococcus pneumoniae was promoted by previous studies that observed an increased prevalence of the bacteria in patients with idiopathic subglottic stenosis and intubation-related tracheal stenosis.14 In addition, retrieved airway stents have previously tested positive for Streptococcus pneumoniae, as well as other bacteria.30 E. Coli and Streptococcus pneumoniae were prepared in shaker flasks at 37°C and grown to an optical density of approximately 1.0 before use. Cell viability was monitored using diluted (10% v/v) alamarBlue® Cell Viability reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in phosphate buffered saline. Prior to beginning the study, 6 mm diameter PCL/PLCL nanofiber discs containing 0, 1.2, 3.5, 6, and 12 mM CSA were affixed to the bottom of black 96 well plates and sterilized as described in the previous section. E. coli and Streptococcus pneumoniae were diluted in the alamarBlue® working solution to corresponding optical densities of 0.01 and 0.08, respectively. 200 μL of the alamarBlue®-bacterial cell solution (either E. coli or Streptococcus pneumoniae) was added to each well of the 96 well plate containing the affixed nanofiber patches (n = 5 per group). Microbial activity was monitored every 30 minutes using a Biotek Cytation 5 plate reader maintained at 37°C for 3 hours. Bacterial growth was considered to be inhibited based on a non-significant difference between the intensity values at 60 and 180 minutes.

Animal Model and Surgical Method

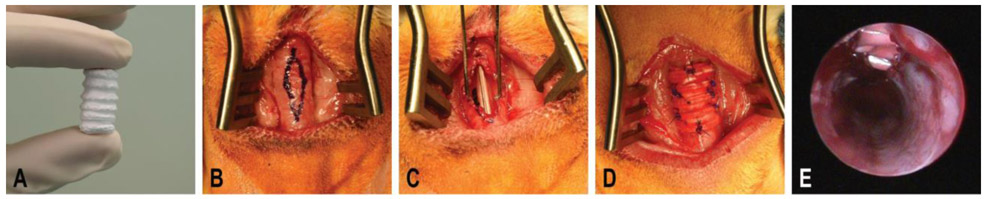

Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (protocol # 18-008-SS-A-U). 24 skeletally mature female New Zealand White rabbits (~4.5 kg) were purchased from Robinson Services Incorporated (Mocksville, NC). The fur was shaved around the ventral cervical region and at the suprasternal area prior to surgery. Rabbits were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine (30-50 mg/kg) and xylazine (3-5 mg/kg) and then intubated and maintained in a surgical plane of anesthesia with isoflurane. Rabbits were placed in the dorsal recumbent position and the surgical site was scrubbed with povidone-iodine and 70% alcohol before being draped in sterile blue surgical towels. The trachea was exposed by creating a ventral midline cervical incision over the trachea. The strap muscles were then identified and divided to access the cervical trachea. A diamond-shaped defect (Fig. 3B) was marked on the outer wall of the trachea with a sterile 3D-printed guide with an approximate size of 15 x 5 mm before excising the marked area (Fig. 3C). The long axis of the defect was oriented along the length of the trachea approximately centered between the cricoid cartilage and the carina cartilage. The scaffolds were cut to an approximate length of ~18 mm in the operating room immediately before placement. These full circumferential scaffolds were then bisected in the sagittal plane to obtain two hemi-cylindrical sections and small 3 mm cuts were made between the PCL rings to guide the sutures. These hemi-cylindrical patches were then sutured into place.

Figure 3.

Surgical overview for the creation of the tracheal defect and implantation of the electrospun patch. A) The electrospun tracheal patch after fabrication and prior to cutting in the operating room with an inner diameter of 8 mm and a length of 15 mm. B) Outline of the diamond shaped tracheal defect measuring 15 by 5 mm. The approximate outer diameter of the trachea measured 8 mm. C) The tracheal defect after removal of the predefined tracheal wall. D) The tracheal patch was sutured into place over the tracheal defect. Note the sutures placed around each of the polycaprolactone (PCL) rings securing the patch and reinforcing the trachea. E) Representative endoscopy image of the inner tracheal wall after implantation of the tracheal patch.

The groups employed in the in vivo study were PCL, PCL/PLCL, PCL/PLCL+CSA (6 mM CSA), and PCL/PLCL+RGD (1 mM RGD), with the CSA and RGD concentrations decided based on the results of aforementioned in vitro studies. Absorbable polydioxanone sutures (PDS, size 4-0) were used to suture the scaffold to the trachea in all rabbits (Fig. 3D). Sutures were placed around the PCL rings to hold the patches in place during healing. The cervical incision was then closed in 3 layers using running PDS sutures for the muscular and subcutaneous layers and nylon sutures (size 4-0) for the skin layer. After each procedure was finished, the inner wall of the trachea was imaged to ensure patency using a Karl Storz (Tuttlingen, Germany) Hopkins endoscope (Fig. 3E). The rabbits then recovered from anesthesia and were monitored for signs of breathing difficulties. After 6 and 12 weeks post-surgery, animals were anesthetized and the inner wall of the trachea was imaged using an endoscope. At the conclusion of the study, the rabbits were humanely euthanized with an overdose of Euthasol (200 mg/kg) in accordance with AVMA guidelines. Euthanasia took place 12 weeks after implantation. Directly following euthanasia, the rabbit tracheas were explanted and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for analysis.

Microcomputed Tomography (μCT)

Tracheal patency was quantified using microcomputed tomography (μCT) on explanted tracheas after 12 weeks post-implantation (n = 6) as we previously described.39 Prior to imaging, explanted tracheas were fixed in 10% phosphate buffered formalin for 48 hours and then incubated in a diluted contrast agent composed of 60% phosphate buffered saline and 40% Optiray 320 (Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Staines-upon-Thames, UK) for 24 hours. After fixation and incubation in contrast agent, a Quantum FX imaging system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) with a 50 kV X-ray source at 160 μA was used to image the tracheas. Samples were positioned such that the center of μCT scan was aligned to the defect site. A 60 mm field of view was chosen that provided a voxel resolution of 118 μm. Avizo computational software (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR) was used to quantify tracheal patency. Patency was quantified within a square volume of interest (VOI) of 15 mm centered over the implanted tracheal patch. The VOI was chosen as it matched the original size of the implanted tracheal patch. An uninjured portion of randomly chosen tracheas was used for comparison. The lumen space was colored blue to demonstrate the space quantified. Quantified patency was presented as the total volume (mm3) and the average cross-sectional area (mm2) was determined by dividing by the length of the original defect (i.e., 15 mm). The total volume and average cross-sectional area represent the same information as the size of defect was the same in all samples. In addition, the minimum cross-sectional area (mm2) within the 15 mm VOI was reported.

Histology

After formalin fixation and μCT imaging, explanted tracheas were embedded, sectioned, and stained. Briefly, tracheas were sectioned in the transverse plane through the middle of the defect. Sections were embedded in paraffin wax following a standard protocol. Paraffin blocks were sectioned to a thickness of 4 μm and affixed to glass microscope slides. The SelecTech hematoxylin and eosin staining system (H&E, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and Masson’s Trichrome (MT) stain (Sigma-Aldrich) were performed following the manufacturer’s protocol. All staining was performed using a Leica ST5020 multistainer (Leica Biosystems).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). The degradation study was analyzed using linear regression to determine if the slope of the property versus time was significantly non-zero. In addition, the degradation study was analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) to compare between PCL and PCL/PLCL at each time point. A one-way ANOVA with groups of factors was used for analyzing cell adhesion, antimicrobial activity, and μCT results. Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was used to compare between groups, in which p < 0.05 was considered significant. The degradation, cell adhesion, and antimicrobial activity studies had n = 5, and μCT and histology had n = 6 samples per group; data are reported as the mean ± the standard deviation.

3. Results

Degradation Study

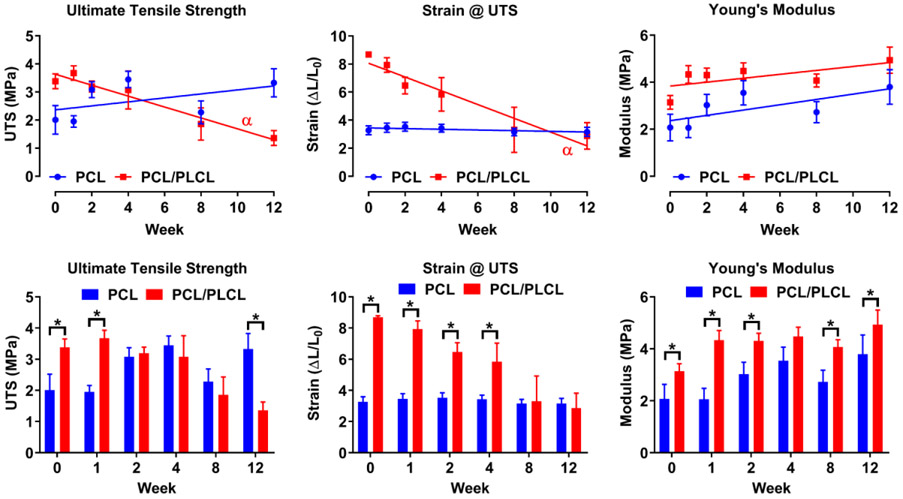

Over the course of the 12-week degradation study, the PCL group did not significantly change in terms of the ultimate tensile strength, strain at the ultimate tensile strength, and Young’s modulus (Fig. 4). The PCL/PLCL group had a significant declining slope for the ultimate tensile strength and strain at the ultimate tensile strength; however, the Young’s modulus remained unchanged. More specifically, the PCL/PLCL ultimate tensile strength had decreased to 35% (1.2 MPa) of the starting value (3.4 MPa) over the 12-week period. The strain at the ultimate tensile strength for the PCL/PLCL group decreased to 33% (2.9) of the starting value (8.7) over the 12-week period.

Figure 4.

Degradation of PCL and PCL/PLCL electrospun nanofiber scaffolds over 12 weeks using tensile testing. Graphs show the ultimate tensile strength (UTS), strain at the UTS, and Young’s modulus. α = Significantly non-zero slope (p < 0.05). For the top row, note the non-decreasing Young’s modulus for either material over the 12-week period. For the bottom row, note significant differences between the PCL and PCL/PLCL at various time point denoted by an asterisk (p < 0.05). Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). PCL = polycaprolactone, PLCL = polylactide-co-caprolactone.

Comparing between the PCL and PCL/PLCL nanofibers at each time-point, the ultimate tensile strength for the PCL/PLCL group at week 0 (3.4 MPa) and week 1 (3.7 MPa) was 1.7 and 1.9 times greater compared to the PCL group, respectively (p < 0.05). At week 12 the ultimate tensile strength of the PCL group (3.3 MPa) was 1.4 times greater compared to the PCL group (p < 0.05). No other significant differences were detected between weeks 2-8 for the ultimate tensile strength. For the strain at the ultimate tensile strength, the PCL/PLCL group at week 0 (8.7), week 1 (7.9), week 2 (6.5), and week 4 (5.8) had 2.7, 2.3, 1.8, and 1.7 times greater strains compared to the PCL group, respectively (p < 0.05). No other differences for weeks 8 and 12 were significant for the strain at the ultimate tensile strength. The Young’s modulus for the PCL/PLCL group for week 0 (3.1 MPa), week 1 (4.3 MPa), week 2 (4.3 MPa), week 8 (4.1 MPa), and week 12 (4.9 MPa) had 1.5, 2.1, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.3 times greater modulus value compared to the PCL group, respectively (p < 0.05). No significant difference in modulus was detected at week 4.

Cell Adhesion

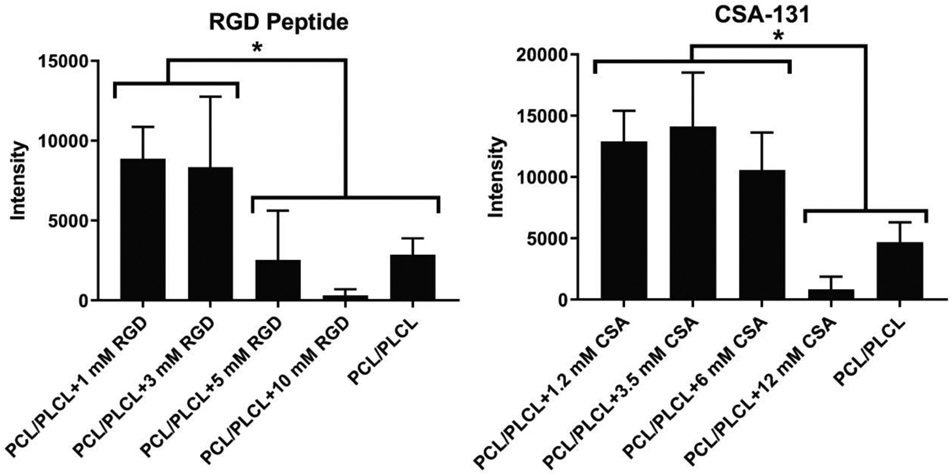

The average rBMSC adhesion for RGD nanofibers after 24 hours was the highest for the PCL/PLCL group containing an RGD peptide concentration of 1 mM (Fig. 5). A decreasing trend for cell adhesion was observed for increasing RGD peptide concentration above 3 mM. The PCL/PLCL+1 mM RGD group had 3.1, 3.5, and 27.8 times greater intensity (i.e., cell adhesion) value compared to the PCL/PLCL control, PCL/PLCL+5 mM, and PCL/PLCL+10 mM group, respectively (p < 0.05). Similarly, the PCL/PLCL+3 mM RGD group had 2.9, 3.3, and 26.2 times greater intensity value compared to the PCL/PLCL, PCL/PLCL+5 mM, and PCL/PLCL+10 mM group, respectively (p < 0.05). No other significant differences were observed among groups containing RGD. Cell adhesion to electrospun PCL/PLCL nanofibers containing CSA was highest on average for the 3.5 mM CSA group. The PCL/PLCL+1.2 mM CSA, PCL/PLCL+3.5 mM CSA, and PCL/PLCL+6 mM CSA groups had 2.7, 3, and 2.2 times greater intensity value compared to the PCL/PLCL group, and 15.8, 17.2, and 12.9 times greater intensity value compared to PCL/PLCL+12 mM CSA group, respectively (p < 0.05). No other significant differences were observed among groups containing CSA.

Figure 5.

Cell adhesion study conducted after 24 hours of seeding the tracheal patch containing either the cell adhesion peptide RGD or the antimicrobial compound CSA-131 with rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. For the RGD electrospun patch, Asterisk (*) = significantly larger intensity value compared to PCL/PLCL, PCL/PLCL+5 mM RGD, and PCL/PLCL+10 mM RGD (p < 0.05). For the CSA-131 electrospun patch, Asterisk (*) = significantly larger intensity value compared to PCL/PLCL and PCL/PLCL+12 mM CSA (p < 0.05). Note a decreasing average intensity value for the RGD-peptide group. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). PCL = polycaprolactone, PLCL = polylactide-co-caprolactone, CSA = ceragenin-131.

Antimicrobial Activity

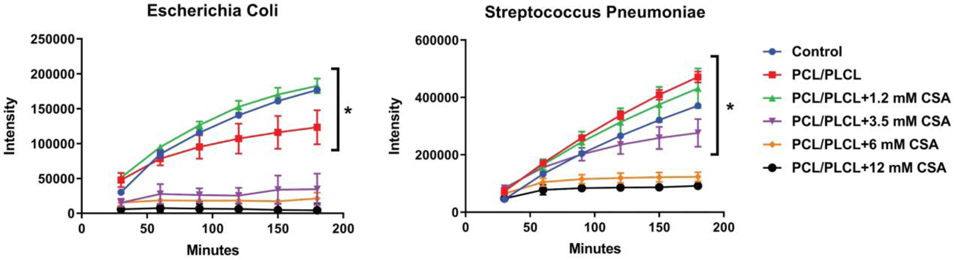

Growth inhibition of E. Coli was achieved for the PCL/PLCL+3.5 mM CSA, PCL/PLCL+6 mM CSA, and PCL/PLCL+12 mM CSA groups as determined by a non-significant change in intensity value (Fig. 6). A significant increase in intensity value was observed for the Control (i.e., E. Coli alone), PCL/PLCL, and PCL/PLCL+1.2 mM CSA groups (p < 0.05). Growth inhibition of Streptococcus was achieved for the PCL/PLCL+6 mM CSA and PCL/PLCL+12 mM CSA groups as determined by a non-significant change in intensity value. A significant increase in intensity value was observed for the Control (i.e., Streptococcus), PCL/PLCL, PCL/PLCL+1.2 mM CSA, and PCL/PLCL+3.5 mM CSA groups (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Antimicrobial activity of electrospun patches containing varying concentrations of CSA-131 for Escherichia Coli and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Asterisk (*) = significantly larger intensity value at 180 min compared to 60 min (p < 0.05). Note the 6 mM CSA-131 concentration was adequate to inhibit the growth of both Escherichia Coli and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). PCL = polycaprolactone, PLCL = polylactide-co-caprolactone, CSA = ceragenin-131.

Animal Survival

All animals survived the creation of the tracheal defect and returned to normalcy after closure with the electrospun patch. Over the course of the 12-week animal study, three of the 24 rabbits (12.5%) either died unexpectedly or were prematurely euthanized. A single rabbit died unexpectedly from the PCL group at 8 weeks. One rabbit from the PCL group at 11 weeks and one rabbit from the PCL/PLCL+CSA group at 10 weeks were prematurely euthanized due to respiratory complications. Therefore, the PCL and PCL/PLCL+CSA groups had 33% and 17% fatality rates, respectively. No respiratory complications or premature deaths occurred in the PCL/PLCL or PCL/PLCL+RGD groups.

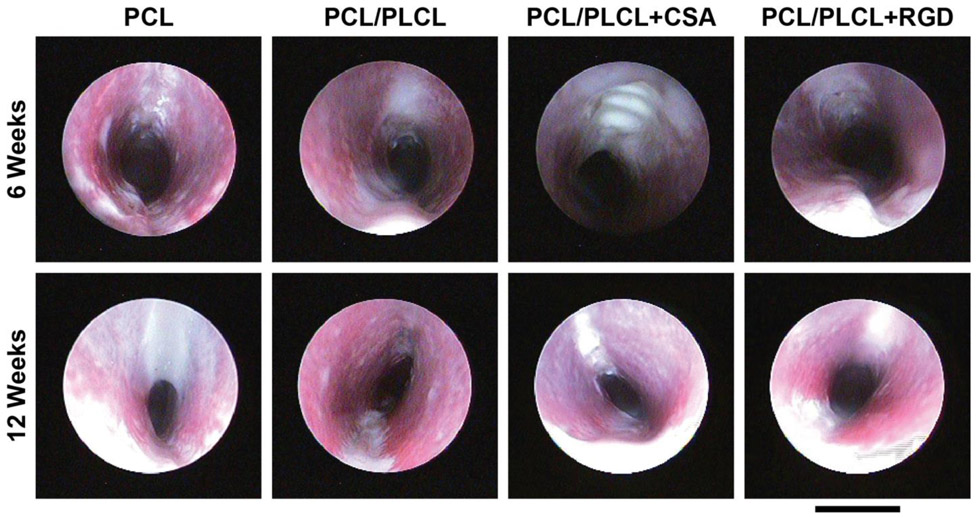

Endoscopy

Endoscopy at 6 weeks post-surgery demonstrated new tissue formation covering the trachea patch in all groups except the CSA group, which had exposed patch after six weeks of healing (Fig. 7). At the 12-week time point all groups had full tissue coverage of the patch. Airway narrowing was observed in all groups at 12 weeks, with the most significant stenosis occurring in the PCL group. In general, there was no observable differences between the PCL/PLCL, PCL/PLCL+CSA, and PCL/PLCL+RGD groups at 12 weeks.

Figure 7.

Representative endoscopy images of each group at 6 and 12 weeks post-surgery. Images were oriented such that the tracheal patch would be at the top of the image in each panel. Note the general trend in decreasing tracheal patency between 6 and 12 weeks post-tracheal patch implantation, particularly for the PCL group. Scale bar = 10 mm. PCL = polycaprolactone, PLCL = polylactide-co-caprolactone, CSA = ceragenin-131.

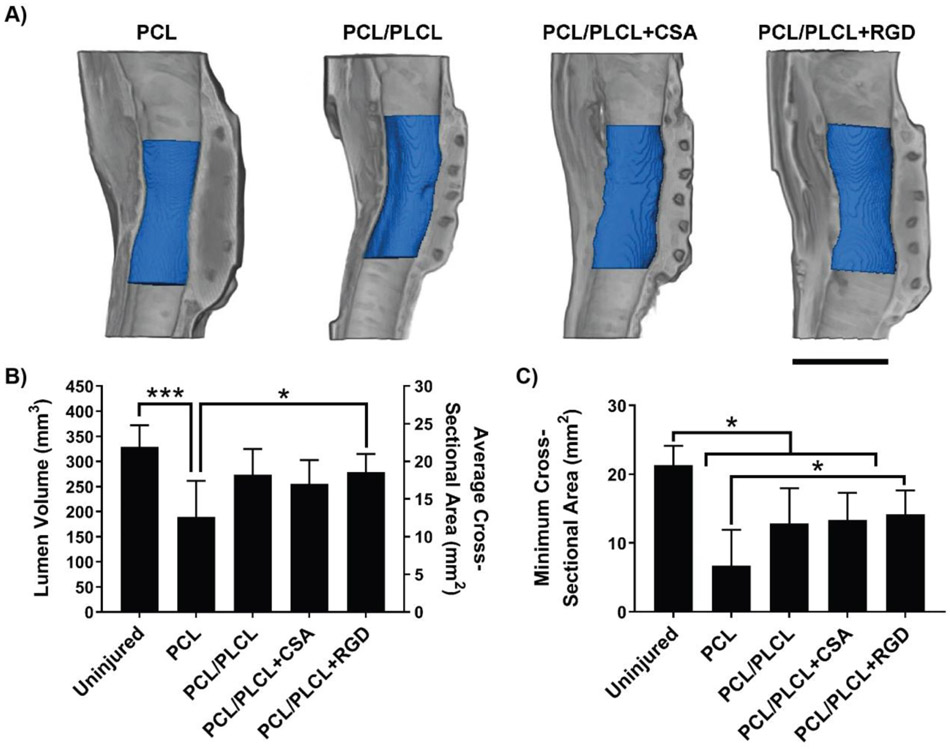

Microcomputed Tomography (μCT)

Gross examination and μCT of the explanted tracheas revealed that all samples had a noticeable tissue formation surrounding the implanted tracheal patches. New tissue formation toward the luminal side of the trachea was observed in all groups, leading to airway narrowing, especially in the PCL negative control group. The minimum cross-sectional area was observed near the center of the patch in all samples (Fig. 8A). The uninjured trachea control group (329 mm3) had 1.7 times greater average lumen volume compared to the PCL group (190 mm3) (Fig. 8B, p < 0.001). The PCL/PLCL+RGD group (279 mm3) had 1.5 times greater average lumen volume compared to the PCL group (Fig. 8B, p < 0.05). No other significant differences in lumen volume were observed among groups. In terms of minimum cross-sectional area, the uninjured group (21.3 mm2) had 3.2, 1.7, and 1.6 times greater minimum cross-sectional area compared to the PCL (6.7 mm2), PCL/PLCL (12.8 mm2), and PCL/PLCL+CSA group (13.3 mm2), respectively (Fig. 8C, p < 0.05). The PCL/PLCL+RGD group (14.2 mm2) had 2.1 times greater minimum cross-sectional area compared to the PCL group (Fig. 8C, p < 0.05). No other significant differences in minimum cross-sectional area were observed among groups.

Figure 8.

Microcomputed tomography (μCT) reconstruction and analysis using Avizo software. A) Representative μCT reconstructions for each experimental group in which the gray coloring indicates the trachea tissue and blue coloring indicates the quantified lumen space across the trachea patch. Scale bar = 10 mm. B) Quantified lumen volume (mm3) and average cross-sectional area (mm2) calculated from the reconstructed μCT scans. Note that the only treatment group with a significantly greater volume than the PCL control was the RGD group. C) Minimum cross-sectional area (mm2) calculated from the reconstructed μCT scans. Note that the RGD group again was the only treatment to be significantly greater in minimum cross-sectional area than the PCL control and furthermore to not be significantly smaller in minimum cross-sectional area than the uninjured positive control. Single asterisk (*) = p < 0.05 and multiple asterisks (***) = p < 0.001. Values represent the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). PCL = polycaprolactone, PLCL = polylactide-co-caprolactone, CSA = ceragenin-131.

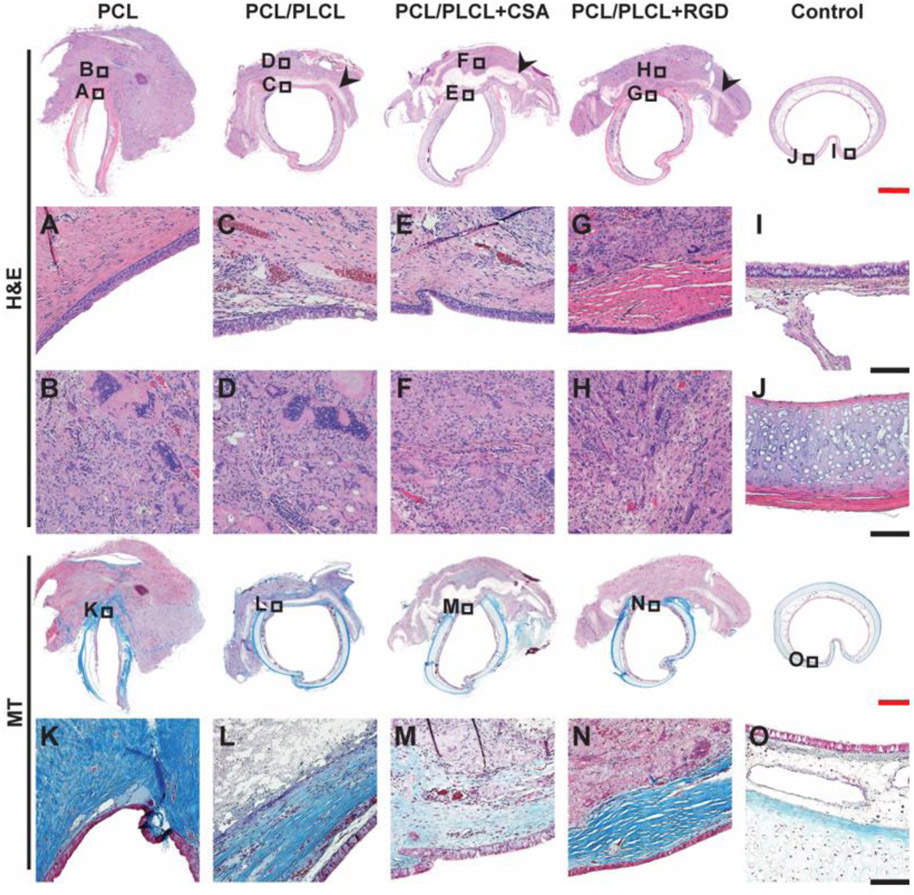

Histology

Residual electrospun fibers were observed in all groups. The PCL group had near complete infiltration of cells into the electrospun patch; however, the PCL group had the largest peritracheal reactive mass around the reconstruction site. In contrast, the PCL/PLCL groups had portions of residual electrospun patch remaining with minimal cell infiltration (Fig. 9 black arrows) and considerably less overall peritracheal reactive mass. Complete re-epithelialization of the luminal side of the electrospun patches was observed in all groups (Fig. 9A-G). The peritracheal reactive changes (Fig. 9B-H) were composed of a mixture of fibroblastic proliferation, chronic inflammatory cell infiltration, and multinuclear foreign body type giant cells. The pathology was similar in all groups; however, the extent of involvement was different. The epithelium in the PCL group was well separated from the underlying inflammatory changes by a layer of inflammation free collagen, but this was more variable in the groups containing PCL/PLCL. No clear regeneration of tracheal cartilage was observed in any group.

Figure 9.

Representative histological samples of rabbit tracheas after 12 weeks post-surgery (n = 6). Transverse sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s Trichrome (MT) stains. Small boxes with letter identifier correspond to the expanded images below with the same letter identifier. Black arrows indicate residual patch. Re-epithelialization was observed in all 4 treatment groups (A to G) and the intensity of inflammation was comparable (B to H). A layer of collagenous fiber was observed in all groups except the PCL/PLCL+CSA group (K to N). Uninjured control trachea is shown for comparison (I, J, and O). PCL = polycaprolactone, PLCL = polylactide-co-caprolactone, CSA = ceragenin-131. Scale bar for top row and for fourth row (red) = 2 mm, scale bar for 2nd, 3rd, and 5th rows (black) = 0.25 mm.

The amount of collagenous fibers induced by the electrospun patches was effectively demonstrated by the MT stain (Fig. 9K-O). The PCL group had the highest intensity of collagenous deposition that connected the edges of the defect. The collagenous layer in the PCL group was further noted to have superficial extension into the reactive inflammatory tissue. The bulk of the collagenous deposition was observed in the superficial area immediately under the regenerated epithelium (Fig. 9K). A similar layer of collagenous fibers was noted in both the PCL/PLCL and PCL/PLCL+RGD group, although the tissue was thinner and not always continuous. In addition, the PCL/PLCL and PCL/PLCL+RGD groups did not show the superficial extension into the reactive inflammatory area as in the PCL group. Although the regenerated epithelium in the PCL/PLCL+CSA group was separated from the underlying inflammatory reactive changes by a thin layer of inflammation free collagenous tissue, the amount of collagenous deposition was far less in comparison to the other groups as demonstrated by the MT stain.

4. Discussion

The electrospun patches employed in the current study were designed with translation in mind, creating an off-the-shelf, acellular, airtight, and biodegradable patch for the treatment of tracheal stenosis. The current study proposed an innovative strategy to evaluate multiple material paradigms, utilizing faster degrading electrospun materials imbuing anti-microbial or cell adhesion properties. The 3D-printed rings were designed to reinforce the trachea after creation of the tracheal defect to hold the trachea open and to provide protection during the healing process.36 The current study represents the next-generation material design by our group following our previously published study using an electrospun PCL patch in an ovine tracheal defect model.39 Implementation of a pure PCL patch in the current study allowed for a relevant comparison to our previous study in the ovine model. The degradation of the PCL/PLCL patches compared to the PCL only nanofibers appeared to be faster overall with observable differences in the ultimate tensile strength, strain at the ultimate tensile strength, and amount of peritracheal tissue after 12 weeks in the rabbit animal model. An interesting outcome of the degradation study was the unchanging Young’s modulus of both the PCL and PCL/PLCL fibers over the 12-week study potentially due to the slower degrading PCL nanofibers present in both materials. A limitation of the degradation study was that only functional mechanical performance was evaluated and not mass loss, which would have added value in the current study. The difference in cell infiltration and subsequent amount of peritracheal reactive mass between the PCL and PCL/PLCL nanofibers may potentially be attributed to different inflammatory responses to the materials.16 The faster-degrading PLCL material may potentially have less inflammatory tissue due to a faster degradation time compared to PCL.

Cellular adhesion of rMSCs on the RGD peptide nanofibers was greatest at the lowest concentration of RGD peptide with a decreasing average intensity value with increasing RGD molar concentration, an unexpected outcome as the initial assumption was that the increasing RGD peptide concentration would increase cellular adhesion. A precious few studies have evaluated RGD molar concentrations above 3 mM; however, in a previous study that used TiO2 nanotubes modified with RGD-peptide at concentrations of 1 and 10 mM, no significant differences in live to dead cell ratios were observed.5 In other studies that reported RGD concentrations up to 2.8 mM, cell adhesion increased with increasing RGD concentration, the opposite of what was observed in the current study; however, these studies used PEG-based hydrogels and not electrospun fibers.24, 32 A potential reason for the decreased cell adhesion with increased RGD concentration may be a changing surface hydrophobicity with an increasing RGD molar concentration, causing cells not to adhere to the electrospun fibers. CSA nanofibers performed well in vitro in terms of the cell adhesion and antimicrobial performance; however, the material was observed to have a delayed tissue regeneration as evident by exposed tracheal patch at the six-week endoscopy. Although CSA performed well in vitro, the in vivo performance suggested that it should not replace RGD for cell adhesion.

The faster-degrading PCL/PLCL electrospun fibers improved airway opening on average compared to the pure PCL material design. In comparison to our previously published study using electrospun PCL nanofibers in sheep,39 similar outcomes between the two animal models were observed. The normalized lumen volumes after regeneration were comparable in both the previous sheep and current rabbit models; however, it should be noted that the sheep study used a larger defect size and shorter regeneration period of 10 weeks. The degree of tissue infiltration was different between the animal models as there was complete infiltration of the PCL patch in the rabbit model; however, the sheep model had less overall cell infiltration, potentially due to different sizes and regeneration rates between rabbit and sheep.26 Although the rabbit regeneration rate does not directly mirror larger animals, the information is still valuable for refining groups before moving toward a larger animal model.

Recently, other groups have investigated synthetic materials for tracheal reconstruction. Chen et al.6 evaluated the use of a synthetic copolymer material developed by Depuy Synthes to patch the tracheal wall in a 68 year-old woman. Although the synthetic copolymer patch was capable of maintaining tracheal patency, the regenerated tissue did not appear to re-epithelialize as observed by the gross morphology, contrary to the current study. In another study, Scierski et al.38 evaluated layered woven carbon fibers impregnated with polysulfone rings in an ovine model. Re-epithelialization of the luminal side of the trachea defect was observed after 24 weeks of recovery as demonstrated by histology. Longer term end-points are advantageous as there is a potential for restenosis due to the degrading leftover scaffold, a potential limitation of the current study. Alternatively, shorter time-points are advantageous to study multiple design iterations. Although the aforementioned approaches have demonstrated promise for the use of synthetic materials in trachea regenerative medicine, future work is needed to identify new materials for regenerative medicine approaches.

Overall, the leading material in the current study was the PCL/PLCL+RGD group as it was the only group to have a significant increase in lumen volume and minimum cross-sectional area compared to the PCL negative control. In addition, the PCL/PLCL+RGD group was the only experimental material that did not result in a significant decrease in the minimum cross-sectional area compared to the uninjured group. However, it should be noted that the differences among the groups containing PCL/PLCL were minimal overall, and the average increase in lumen volume compared to the control PCL group may be attributed to the faster-degrading PCL/PLCL electrospun material as demonstrated by the μCT results. In addition, the regulatory and economic costs of incorporating RGD into the electrospun fibers may outweigh the potential benefits. Alternatively, the inclusion of RGD could potentially accelerate healing times sufficiently to allow for an even faster-degrading polymer formulation. Balancing the material degradation rate is a crucial design factor for maintaining structural integrity long enough for sufficient regeneration to occur while resorbing soon enough to minimize (re)stenosis long-term.

5. Conclusion

The current study evaluated the use of a PCL/PLCL electrospun nanofiber patch with embedded 3D printed PCL rings for the treatment of tracheal stenosis. In addition, the cell adhesion peptide, RGD, or the antimicrobial compound, ceragenin-131, were added to the electrospinning solutions for enhanced cell adhesion or antimicrobial activity, respectively. The electrospun patches were designed as an off-the-shelf (e.g., acellular, airtight, biodegradable) option to treat tracheal stenosis. Overall, the PCL/PLCL patches were capable of maintaining tracheal patency after creation of the defect, demonstrated desirable re-epithelialization of the luminal side of the tracheal defect, and minimally reduced the lumen volume after 12 weeks of recovery. The addition of RGD may add value for patency if improved efficacy (e.g., RGD concentration and tuned degradation) can justify regulatory and economic costs. The addition of CSA into the PCL/PLCL nanofibers demonstrated in vitro efficacy, and while antimicrobial activity did not add value in the current in vivo study, antimicrobials may add value in select cases where infection is a concern. Implementation of the faster degrading PCL/PLCL polymer improved tracheal patency compared to the PCL control material. The polymer degradation rate may therefore perform an important role for maintaining tracheal patency and minimizing tissue over-growth at the defect site. Future studies are needed to fine-tune the polymer degradation time for the treatment of various defect sizes (e.g., human vs. rabbit vs. sheep) and to minimize tissue overgrowth and prevent (re)stenosis. In addition, future studies will focus on expanded experimental testing, such as immunohistochemistry, to further evaluate tissue regeneration.

6. Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Hong Liu and Dr. Yuhua Li for assistance with μCT imaging. The authors would like to thank Alysa Phan for designing the graphical abstract. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R43 HL140890 (to JKJ). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial Disclosure: Research reported in the publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R43 HL140890 (to JKJ).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

7. References

- 1.Axtell AL and Mathisen DJ Idiopathic subglottic stenosis: techniques and results. Ann Cardiothorac Surg, 7, 299–305, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beall AC Jr., Harrington OB, Greenberg SD, Morris GC Jr. and Usher FC Tracheal replacement with heavy Marlex mesh. Circumferential replacement of the cervical trachea. Arch Surg, 84, 390–396, 1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Best CA, Pepper VK, Ohst D, Bodnyk K, Heuer E, Onwuka EA, King N, Strouse R, Grischkan J, Breuer CK, Johnson J and Chiang T Designing a tissue-engineered tracheal scaffold for preclinical evaluation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 104, 155–160, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burdick JA and Anseth KS Photoencapsulation of osteoblasts in injectable RGD-modified PEG hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials, 23, 4315–4323, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao X, Yu WQ, Qiu J, Zhao YF, Zhang YL and Zhang FQ RGD peptide immobilized on TiO2 nanotubes for increased bone marrow stromal cells adhesion and osteogenic gene expression. J Mater Sci Mater Med, 23, 527–536, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen D, Britt CJ, Mydlarz W and Desai SC A novel technique for tracheal reconstruction using a resorbable synthetic mesh. Laryngoscope, 128, 1567–1570, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Trey LA and Morrison GA Buccal mucosa graft for laryngotracheal reconstruction in severe laryngeal stenosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 77, 1643–1646, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delaere P, Vranckx J, Verleden G, De Leyn P, Van Raemdonck D and Leuven Tracheal Transplant G Tracheal allotransplantation after withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy. N Engl J Med, 362, 138–145, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Den Hondt M and Vranckx JJ Reconstruction of defects of the trachea. J Mater Sci Mater Med, 28, 24, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dikina AD, Strobel HA, Lai BP, Rolle MW and Alsberg E Engineered cartilaginous tubes for tracheal tissue replacement via self-assembly and fusion of human mesenchymal stem cell constructs. Biomaterials, 52, 452–462, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott M, Hartley BE, Wallis C and Roebuck D Slide tracheoplasty. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 16, 75–82, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galvez Alegria C, Gundogdu G, Yang X, Costa K and Mauney JR Evaluation of Acellular Bilayer Silk Fibroin Grafts for Onlay Tracheoplasty in a Rat Defect Model. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 194599818802267, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao M, Zhang H, Dong W, Bai J, Gao B, Xia D, Feng B, Chen M, He X, Yin M, Xu Z, Witman N, Fu W and Zheng J Tissue-engineered trachea from a 3D-printed scaffold enhances whole-segment tracheal repair. Sci Rep, 7, 5246, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelbard A, Katsantonis NG, Mizuta M, Newcomb D, Rotsinger J, Rousseau B, Daniero JJ, Edell ES, Ekbom DC, Kasperbauer JL, Hillel AT, Yang L, Garrett CG, Netterville JL, Wootten CT, Francis DO, Stratton C, Jenkins K, McGregor TL, Gaddy JA, Blackwell TS and Drake WP Molecular analysis of idiopathic subglottic stenosis for Mycobacterium species. Laryngoscope, 127, 179–185, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilpin DA, Weidenbecher MS and Dennis JE Scaffold-free tissue-engineered cartilage implants for laryngotracheal reconstruction. Laryngoscope, 120, 612–617, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goonoo N Modulating Immunological Responses of Electrospun Fibers for Tissue Engineering. Advanced Biosystems, 1, 1700093, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gozen ED, Yener M, Erdur ZB and Karaman E End-to-end anastomosis in the management of laryngotracheal defects. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, 131, 447–454, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimmer JF, Gunnlaugsson CB, Alsberg E, Murphy HS, Kong HJ, Mooney DJ and Weatherly RA Tracheal reconstruction using tissue-engineered cartilage. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 130, 1191–1196, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofferberth SC, Watters K, Rahbar R and Fynn-Thompson F Management of Congenital Tracheal Stenosis. Pediatrics, 136, e660–669, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ignatova M, Manolova N and Rashkov I Novel antibacterial fibers of quaternized chitosan and poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) prepared by electrospinning. European Polymer Journal, 43, 1112–1122, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang Y, Wang C, Qiao Y, Gu J, Zhang H, Peijs T, Kong J, Zhang G and Shi X Tissue-Engineered Trachea Consisting of Electrospun Patterned sc-PLA/GO- g-IL Fibrous Membranes with Antibacterial Property and 3D-Printed Skeletons with Elasticity. Biomacromolecules, 20, 1765–1776, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khadka DB and Haynie DT Protein- and peptide-based electrospun nanofibers in medical biomaterials. Nanomedicine, 8, 1242–1262, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim TG and Park TG Biomimicking extracellular matrix: cell adhesive RGD peptide modified electrospun poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanofiber mesh. Tissue Eng, 12, 221–233, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosinski AM, Sivasankar MP and Panitch A Varying RGD concentration and cell phenotype alters the expression of extracellular matrix genes in vocal fold fibroblasts. J Biomed Mater Res A, 103, 3094–3100, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Yu Y, Myungwoong K, Li K, Mikhail J, Zhang L, Chang C-C, Gersappe D, Simon M, Ober C and Rafailovich M Manipulation of cell adhesion and dynamics using RGD functionalized polymers. J. Mater. Chem. B, 5, 6307–6316, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Chen SK, Li L, Qin L, Wang XL and Lai YX Bone defect animal models for testing efficacy of bone substitute biomaterials. J Orthop Translat, 3, 95–104, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinod E, Chouahnia K, Radu DM and et al. Feasibility of bioengineered tracheal and bronchial reconstruction using stented aortic matrices. JAMA, 319, 2212–2222, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mobasseri R, Tian L, Soleimani M, Ramakrishna S and Naderi-Manesh H Bio-active molecules modified surfaces enhanced mesenchymal stem cell adhesion and proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 483, 312–317, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nouraei SA, Ma E, Patel A, Howard DJ and Sandhu GS Estimating the population incidence of adult post-intubation laryngotracheal stenosis. Clin Otolaryngol, 32, 411–412, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nouraei SA, Petrou MA, Randhawa PS, Singh A, Howard DJ and Sandhu GS Bacterial colonization of airway stents: a promoter of granulation tissue formation following laryngotracheal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 132, 1086–1090, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nouraei SAR, Battson RM, Koury EF, Sandhu GS and Patel A Adult Post-Intubation Laryngotracheal Stenosis: An Underestimated Complication of Intensive Care? Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 10, 229–229, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nuttelman CR, Tripodi MC and Anseth KS Synthetic hydrogel niches that promote hMSC viability. Matrix Biol, 24, 208–218, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olekson MA, You T, Savage PB and Leung KP Antimicrobial ceragenins inhibit biofilms and affect mammalian cell viability and migration in vitro. FEBS Open Bio, 7, 953–967, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ott LM, Vu CH, Farris AL, Fox KD, Galbraith RA, Weiss ML, Weatherly RA and Detamore MS Functional Reconstruction of Tracheal Defects by Protein-Loaded, Cell-Seeded, Fibrous Constructs in Rabbits. Tissue Eng Part A, 21, 2390–2403, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ott LM, Weatherly RA and Detamore MS Overview of tracheal tissue engineering: clinical need drives the laboratory approach. Ann Biomed Eng, 39, 2091–2113, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ott LM, Zabel TA, Walker NK, Farris AL, Chakroff JT, Ohst DG, Johnson JK, Gehrke SH, Weatherly RA and Detamore MS Mechanical evaluation of gradient electrospun scaffolds with 3D printed ring reinforcements for tracheal defect repair. Biomed Mater, 11, 025020, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossi ME, Moreddu E, Mace L, Triglia JM and Nicollas R Surgical management of children presenting with surgical-needed tracheal stenosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 108, 219–223, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scierski W, Lisowska G, Namyslowski G, Misiolek M, Pilch J, Menaszek E, Gawlik R and Blazewicz M Reconstruction of Ovine Trachea with a Biomimetic Composite Biomaterial. Biomed Res Int, 2018, 2610637, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Townsend JM, Ott LM, Salash JR, Fung KM, Easley JT, Seim HB 3rd, Johnson JK, Weatherly RA and Detamore MS Reinforced Electrospun Polycaprolactone Nanofibers for Tracheal Repair in an In Vivo Ovine Model. Tissue Eng Part A, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsang V, Murday A, Gillbe C and Goldstraw P Slide tracheoplasty for congenital funnel-shaped tracheal stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg, 48, 632–635, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Unnithan AR, Barakat NA, Pichiah PB, Gnanasekaran G, Nirmala R, Cha YS, Jung CH, El-Newehy M and Kim HY Wound-dressing materials with antibacterial activity from electrospun polyurethane-dextran nanofiber mats containing ciprofloxacin HCl. Carbohydr Polym, 90, 1786–1793, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unnithan AR, Gnanasekaran G, Sathishkumar Y, Lee YS and Kim CS Electrospun antibacterial polyurethane-cellulose acetate-zein composite mats for wound dressing. Carbohydr Polym, 102, 884–892, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weidenbecher M, Tucker HM, Gilpin DA and Dennis JE Tissue-engineered trachea for airway reconstruction. Laryngoscope, 119, 2118–2123, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang F, Williams CG, Wang DA, Lee H, Manson PN and Elisseeff J The effect of incorporating RGD adhesive peptide in polyethylene glycol diacrylate hydrogel on osteogenesis of bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials, 26, 5991–5998, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeo A, Rai B, Sju E, Cheong JJ and Teoh SH The degradation profile of novel, bioresorbable PCL-TCP scaffolds: an in vitro and in vivo study. J Biomed Mater Res A, 84, 208–218, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zopf DA, Hollister SJ, Nelson ME, Ohye RG and Green GE Bioresorbable airway splint created with a three-dimensional printer. N Engl J Med, 368, 2043–2045, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]