Abstract

Atrial arrhythmias are common during episodes of acute respiratory failure in patients with chronic lung disease-associated pulmonary hypertension. Expert opinion suggests that management of atrial arrhythmias in patients with pulmonary hypertension should aim to restore sinus rhythm. This is clinically challenging in pulmonary hypertension patients with coexisting chronic lung disease, as there is controversy on the use of rhythm control agents; generally, in regard to either their pulmonary toxicity profile or the lack of evidence supporting their use. Rate control methods are largely focused on the use of beta blockers and calcium channel blockers. Concerns regarding their use involve their negative inotropic properties in cor pulmonale, the risk of bronchospasm associated with beta blockers, and the potential for ventilation/perfusion mismatching associated with calcium channel blockers. While digoxin has been associated with promising outcomes during acute right ventricular failure, there is limited evidence to suggest its routine use. Electrical cardioversion is associated with a high failure rate and it frequently requires multiple attempts. Radiofrequency catheter ablation is a more definitive approach, but concerns surrounding mechanical ventilation and sedation limit its applicability in decompensated pulmonary hypertension. Individual approaches are needed to address atrial arrhythmia management during acute episodes of respiratory failure.

Keywords: Antiarrhythmic agents, arrhythmia, COPD, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension

Introduction

Chronic lung diseases (CLD), such as the chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) and the interstitial lung diseases (ILD), are frequently complicated by atrial arrhythmias (AAs) during acute respiratory failure (ARF). Inflammation, bronchospasm, and destruction of lung parenchyma result in acute and chronic hypoxia. The development of pulmonary hypertension (PH) results from pulmonary vascular vasoconstriction, remodeling, and other hemodynamic alterations.1 This subtype of PH is categorized as Group III PH, which is defined by right heart catheterization demonstrating: a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) 21–24 mmHg at rest with a pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of ≥ 3 Wood Units, or ≥25 mmHg at rest (irrespective of PVR), in the setting of known pulmonary disease.2,3 The presence of PH is associated with increased risk of AAs, which predominantly include atrial fibrillation (AF) and atrial flutter (AFl).

AAs in patients with CLD-PH are common causes of acute clinical decompensation related to progressive right heart failure. In acute respiratory failure (ARF) it is difficult to differentiate if AAs are a complication of an underlying etiology or if they are the cause of the clinical decompensation. Treatment is fundamentally based on addressing the precipitating cause of the ARF (i.e. hypoxia, inflammation, volume overload etc.) and the use of respiratory medications (primarily bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory agents). Inhaled beta agonist agents, inhaled anti-cholinergic agents, and inhaled/oral/intravenous corticosteroids have been shown to increase arrhythmogenicity by enhancing AV nodal conduction, promoting parasympathetic suppression, and altering potassium efflux.4–6 Thus, balancing the alleviation of respiratory distress and avoiding arrhythmia triggers is challenging. Once any atrial arrhythmia occurs, the hemodynamic stability is affected by the impairment of atrial contraction and loss of atrioventricular synchrony. Often the presence of rapid heart rates further impairs diastolic filling and cardiac output (CO),5,6 exacerbating ARF through pulmonary congestion and worsening hypoxemia. When severe PH is present, new onset supraventricular tachycardias (SVTs) can impact hemodynamic stability and are associated with increased mortality.6,7

The evidence that guides atrial arrhythmia management within CLD has been best described for AF in COPD. However, the evidence guiding AA management during ARF in CLD patients with PH is limited. Treatment recommendations for AAs during ARF in PH patients are in favor of restoring sinus rhythm over rate control, but the options are limited when considering the potential effects of the various agents on CLD. When attempting to restore sinus rhythm, failure rates are high with both pharmacological and interventional management.6 While limited management options are an issue in relatively stable CLD-PH, the paucity of interventions available for AA associated with decompensated CLD-PH is daunting.

Pathophysiology in the development of atrial arrythmias

Changes in pulmonary vascular structure and hemodynamics result from chronic hypoxia seen in patients with CLD. These changes perpetuate or serve as triggers that initiate the development of AAs.1 Chronic hypoxia and chronic right atrial pressure overload, as seen in CLD-associated PH (CLD-PH), have been linked with distention and fibrotic remodeling of the right atrium and increased risk for development of AF.8 While AF is generally associated with ectopic excitation of the atrium, AFl is associated with a reentrant circuit around the tricuspid annulus.9

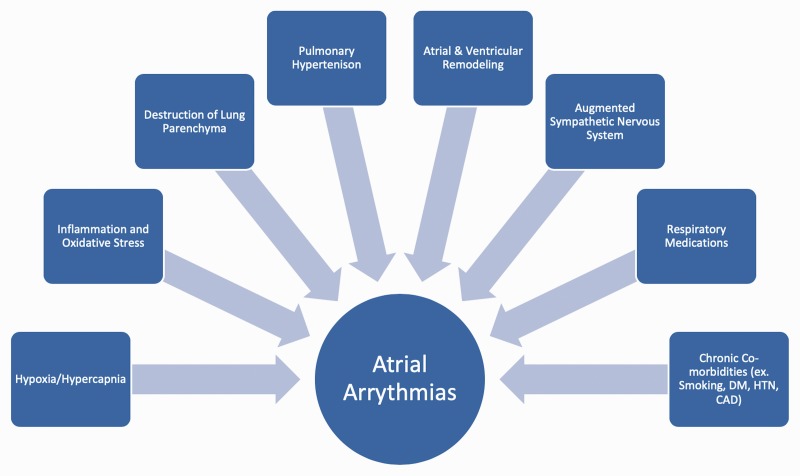

Fig. 1 highlights risk factors for the development of AAs in patients with CLD-PH.

Fig. 1.

Risk factors contributing to the development of atrial arrhythmias in patients with chronic lung disease associated pulmonary hypertension. CAD: coronary artery disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension.

Non-pulmonary vein foci

Non-pulmonary vein foci (NPVF) are important sites for the initiation and maintenance of AF in ∼20% of patients.10 As a result of right atrial remodeling, NPVF promotes AF development and is more frequent in CLD patients in comparison to AF patients without CLD.1 In CLD-PH, the enlargement of the right atrium is a consequence of progressive pulmonary vascular disease, elevated pulmonary arterial pressure, and elevated right ventricular pressure.8 This correlates with increases in NPVF which originate from sustained volume overload or stretching of the right atrium. Hypoxia, as a complication of ARF, may also cause and contribute to development of NPVF.11 Hypoxia has been shown to significantly change cardiac electrophysiological properties and to decrease the rate of spontaneous impulse initiation within the sinoatrial nodal fibers and spontaneous pulmonary vein activity.11 This effect is due to a hypoxia induced shortening of the action potential duration and reduced conduction velocity. This was discovered in an animal study using rabbits, where conventional microelectrode measurements were taken within the pulmonary veins, left atrium and right atrium. Additionally, this animal study demonstrated that hypoxic injury increased both pulmonary vein and non-pulmonary vein arrhythmogenesis which contributed to the development of AAs.11 Therefore, AAs in CLD-PH patients can result in a self-perpetuating cycle of arrhythmogenic substrate formation through both disease progression and episodes of ARF.

The effect of atrial stretch and fibrosis

Atrial stretch and fibrosis form an arrhythmogenic substrate. Changes of myocardial ion channel distribution and activation cause electrical remodeling of the right atrium, which further increase arrhythmogenic vulnerability.12 Atrial remodeling potentiates ectopic or reentrant activity and can precipitate AAs.13 Remodeling further increases the arrhythmogenic substrate and ectopic activity, which in itself can function as a trigger for reentrant activity that leads to atrial arrythmias. Investigations in Group 1 and 4 PH subtypes have demonstrated that increased right atrial pressure and chamber size are risk factors for the development of AAs.5,8,14 Electrophysiological studies in the right atrium of idiopathic PH patients have demonstrated slower conduction velocities with regional abnormalities, reduced tissue voltage, and regions of electrical silence.15 Slowing of both atrial conduction and atrial activation time are essential for AF activation and maintenance.12 Changes in sarcolemmal sodium cannels, gap junction channels, or tissue structure cause slowing of atrial conduction. Fibrotic areas contribute to areas of reduced tissue voltage and regionals of electrical silence which promote areas of ectopic activity. Atrial dilation and fibrosis increase the quantity of atrial tissue that is predisposed to reentry circuits, which allow for the development and maintenance of AAs.13

Neurohormonal activation

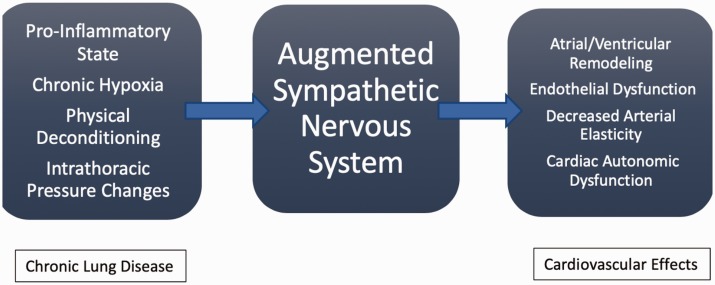

Chronic sympathetic activation progresses heart failure, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance.16,17 Fig. 2 summarizes potential mediators and their effects on sympathetic tone within the cardiovascular system. Chronic hypoxia may result in sympathetic augmentation, but its mechanism is poorly understood. One small study demonstrated increased sympathetic activity in patients with both COPD and pulmonary fibrosis compared to matched healthy controls.17 This study suggested that the changes in sympathetic tone in patients with CLD was partially related to chronic hypoxia induced arterial chemoreflex activation of sympathetic outflow. Oxygen therapy did have benefit in CLD patients by reducing sympathetic tone, but not to a level of healthy subjects. This implied that chronic hypoxia lead to chronic alterations in chemoreceptor stimulation and/or that there are other mechanisms that contribute to sympathetic overactivity. Other suggested mechanisms for increased sympathetic activation in CLD patients include: increased ischemic metabolites during muscular contraction in patients with increased work of breathing (local metaboreceptor stimulation), changes in arterial and cardiopulmonary baroreflexes, lung inflation reflexes mediated by pulmonary vagal afferents (pulmonary stretch receptors), elevated heart rates, reduced heart rate variation, abnormal heart rate recovery following exercise, and sympathomimetic medications used in their treatment.16,18,19 It is unclear on the correlation between hypercapnia and sympathetic activity, as there are conflicting studies demonstrating both increase sympathetic and parasympathetic tone.19

Fig. 2.

Sympathetic mediators on the intrathoracic cardiovascular system. Proposed effects in CLD patients on the autonomic nervous system and its influence on cardiovascular system.

Heart failure progression from chronic sympathetic activation is due to structural changes of the myocardium related to down regulation of B-receptors, increased myocardial remodeling, and apoptosis.17,20–22 The pulmonary arteries are heavily concentrated with sympathetic innervation pathways and are stimulated by pulmonary smooth muscle a1-adrenergic receptors, endothelial a2-adrenergic receptors, and both B1- and B2-adrenergic receptors.17,23 Pulmonary vasoconstriction is triggered by B-receptor blockade which is amplified by sympathetic stimulation.24 This increased sympathetic tone in the pulmonary vasculature contributes to the development and progression of right heart failure. Higher sympathetic activation has been demonstrated to have increased susceptibility to life threatening arrhythmias and increased mortality in PH patients.17

Consideration of multifocal atrial tachycardia

The pathophysiology of multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT) is not fully understood but is currently believed to be associated with increased right atrial pressures and distention.25,26 MAT is commonly described during acute exacerbations of COPD and is associated with an increased mortality rate.27 In fact, MAT has been described more frequently than AF or AFl in ARF associated with COPD28,29 and yet little is known of its presence within CLD-PH. This is in part due to the fact that MAT is frequently mistaken for AF on EKG, which potentially leads to management errors.29 MAT has been described as a poor prognostic indicator in COPD patients requiring mechanical ventilation.30 In that study, the presence of cor pulmonale and ECG findings suggestive of right-sided enlargement/strain were notable findings distinguishing patients with and without MAT.

The presence of other atrial tachycardias in CLD-PH

Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) and atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) are less commonly reported in patients with either or both CLD and PH, in comparison to AF and AFl. Thus, the evidence for management in CLD-PH patients with AVNRT and AVRT are lacking. Adenosine is a short acting agent that is reserved for atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) and atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT). It is clinically acceptable to use adenosine in hemodynamically stable COPD patients with AVNRT or AVRT, provided that there is no active wheezing. One small study reviewed the role of adenosine in patients with obstructive lung disease in patients undergoing adenosine stress myocardial perfusion scintigraphy.31 While these patients tolerated adenosine well, there was evidence of significant airflow limitation. For this reason, it is reasonable to advise against the use of adenosine in COPD patients with SVTs in ARF, especially during active wheezing. Adenosine's role in ILD or CLD-PH not well characterized and further investigation is needed. Other arrythmia control interventions (discussed below), medical or interventional, should be considered in CLD-PH that are in ARF with AVNRT and AVRT.

Available epidemiology

The prevalence of AF in patients hospitalized with COPD has nearly doubled between the years of 2003 to 2014 (from 12.9% to 21.3%, respectively) in a recent study using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.32 Risk factors for the development of AF were: age 75 years, male sex, and white race. Possible explanations for the increase in prevalence were an increased aging population, improvement in AF diagnosis, and reduced AF-related mortality. Additionally, they reported that COPD patients with AF had higher mortality, increased rate of strokes, greater use of mechanical ventilation, higher costs, and longer hospital admissions. While this study was well powered, it was limited to patients with end stage COPD requiring home oxygen which is not representative of the entire COPD population. This is also difficult to extend to patients with COPD-associated PH due to the fact they are not representative of the entire COPD population. In another retrospective study of hospitalized COPD patients, at any stage of the disease, male gender and age were not risk factors for AF.33 Their study concluded that COPD patients with AF had higher mortality, increased risk of end organ dysfunction, and higher rates of ARF. COPD severity has been associated with a significantly increased risk for the development of AF and AFl (21.8% in mild/moderate COPD, 26% in severe COPD, and 31.8% in very severe COPD) in comparison to those patients without COPD (11.0%).34

The annual incidence of AAs in PAH has been estimated to be 3%.35 One small retrospective study in-all-cause PH patients described an atrial arrhythmia incidence of 22% within 35 months of PH diagnosis.6 This suggests a temporal association between duration and progression of PH and risk for atrial arrhythmia development, which has been described in Group 1 Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH).36 Another retrospective study demonstrated that COPD with and without evidence of PH had no difference in the prevalence of atrial tachycardias.37

There is limited data on the epidemiology of AAs in ILD. In low powered studies, AF occurred in up to 9 to 19% of patients with IPF.38,39 The epidemiology of AAs in other ILDs have not been described. Thus, the epidemiology of AAs in CLDPH needs further investigation.

Common causes of atrial arrhythmias

AAs can be a primary cause or a secondary consequence of ARF in CLD-PH.

They are either acute in onset or an exacerbation of a known chronic arrhythmia. Chronic hypoxia, increased right atrial pressure, and volume overload contribute to right atrial chamber dilation and fibrosis in PH, which predispose to AAs. There are multiple secondary etiologies that can trigger right heart strain and AAs. Processes to consider in the differential include hypoxia ± hypercarbia, CLD exacerbation, electrolyte derangements, acid/base disturbance, volume overload, anemia, infection, pulmonary embolism, and myocardial infarction. When identified, these processes should be promptly addressed to alleviate secondary causes of AAs.

Pharmacological management

The debate between rate control versus rhythm control in AF is particularly challenging in PH patients. Prior studies on AF management have not included patients with CLD and/or PH.40–42 There are no randomized control studies comparing the two management strategies within PH or CLD cohorts. Factoring CLD during ARF on top of PH further complicates this challenge in management. General expert opinion on PH, the guidance from the European Society of Cardiology, and from the European Respiratory Society currently recommend atrial rhythm control as the preferred strategy for AAs in PH patients.2,43 Table 1 describes the antiarrhythmic properties of pharmacological options described below.

Table 1.

Vaughn-Williams classification of antiarrhythmics.

| Class | Mechanism | Class effects | Examples | Selected relevant references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1c | Na + channel blockade | Marked decrease in phase 0 depolarization; prolongation of QRS interval | Flecainide, Propafenone | Olsson et al.14 Mercurio et al.44 Malacznska-Rajpold et al.36 Durheim et al.45 Schwarzkopf et al.46 |

| II | Beta-1 receptor antagonist | Decrease in heart rate, decrease AV nodal conduction, and ventricular automaticity; increased PR interval | Metoprolol, Carvedilol | Mercurio et al.44 You et al.47 Durheim et al.45 |

| III | K + channel blockade | Prolongation of ventricular repolarization (phases 1–3), prolongation of QT interval | Amiodarone,a Dronedarone, Sotalolb | Olsson et al.14 Wen et al.5 Durheim et al.45 Mercurio et al.44 Malacznska-Rajpold et al.36 Cannillo et al.6 |

| IV | Calcium channel antagonist | Decrease in heart rate, decrease AV nodal conduction, increased PR interval | Diltiazem, Verapamil | Mercurio et al.44 You et al.47 Durheim et al.45 |

Amiodarone has additional properties that act within the I, II, and IV classification.

Sotalol has additional properties that act within the type II classification.

Rate control

Beta blockers

Beta-blockers (BBs) function as class II antiarrhythmic agents that slow depolarization in slow action potential cells. BBs are categorized based on receptor specificity (ie. beta-1 and/or beta-2 affinity) which can have different influences on CLD-PH patients.

Use in hemodynamically stable patients with chronic lung disease

BBs have been demonstrated to be safe when used in COPD patients in outpatient management of chronic disease(s), despite their known association with bronchoconstriction.48,49 Low dose beta-1 selective BBs may protect against chronotropic, inotropic, and electrocardiographic effects of inhaled beta agonists that are mediated by beta-2 receptors.50 COPD patients treated with BBs have been shown to be at reduced risk of COPD hospitalization and mortality.51,52 In terms of AF control in COPD, BBs (selective or nonselective) have been associated with improved mortality in comparison to calcium channel blockers (CCB) or digoxin.47

BBs are the agents most commonly used for rate control in COPD patients with AF.45

BBs are also commonly used in the outpatient setting for rate control in ILD patients with AAs. One study found that up to 30% of patients with ILD are on BBs for the treatment of co-existing cardiovascular disease and 88.6% of ILD patients with cardiac arrhythmias were on BBs.46 No study has reported on their efficacy. BBs have occasionally been associated with ILD development53 but this is an extremely rare complication and should not impact acute AAs management.

Beta blockers in patients with pulmonary hypertension

BBs may inhibit endothelin-1 release and reduce circulation proinflammatory cytokines, which are direct or indirect biomarkers implicated in the development of PH.54 In a mouse model, nonselective BBs have been demonstrated to prevent RHF and reverse RHF through decreasing fibrosis, apoptosis, and capillary rarefaction in the pressure overloaded right ventricle.55,56 Specific BBs, such as nebivolol and carvedilol, have theoretical benefits that include reduced right ventricular afterload, increased nitric oxide bioactivity (nebivolol), and alpha blocking activity (carvedilol).55

Table 2 summarizes recent studies evaluating the tolerability of BBs in hemodynamically stable PH patients. Currently, there are no studies addressing the use of BBs in PH patients with ARF. While left ventricular oxygen supply occurs predominantly through blood flow during diastole, right ventricular oxygen delivery occurs during both systole and diastole. Increasing diastolic filling times in right ventricular failure (RVF), as in the use of BBs, may impair right ventricular oxygen delivery and be particularly detrimental in decompensated states. Increased diastolic filling times raise the end-diastolic pressure of the right ventricle. This can worsen right ventricular systolic function through cardiac myofibril overdistention. As the right ventricular systolic pressure rises, there is a decrease in systolic coronary blood flow. Downstream this causes reduced left ventricular preload due to septal displacement, decreased cardiac output, and insufficient aortic pressures required to adequately perfuse the coronary arteries.64 The summative effect results in impaired right ventricular oxygenation and increased myocardial oxygen demand; inducing right ventricular ischemia and hemodynamic collapse. The use of BBs in Group 1 PH has been discouraged unless required by co-existing comorbidities (i.e. hypertension, coronary artery disease, and left-sided heart failure).55

Table 2.

Evidence for beta blocker tolerance in PH patients.

| Clinical evidence (type of study) | Rate control agent | PH population (number of patients) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thenappan et al.57 (retrospective study) | Nonspecific BB therapy | Group 1 (n = 564) | No significant difference in long-term mortality with use of BBs in PAH patients |

| Bandyopadhyay et al.58 (retrospective study) | Nonspecific BB therapy | Group 1 PAH IPAH and CTD-PAH (n = 568) | Long-term BB use had similar survival and time to clinical worsening compared to patients not receiving BBs |

| So et al.59 (prospective study) | Nonspecific BB therapy | Group 1 PAH (n = 94) | BB use is common in Group 1 PH with no significant difference in hospitalization, pulmonary hemodynamics, RV function, and mortality. No difference in NYHA functional class, but 6MWD was reduced in patients who received BBs |

| van Campen et al.60 (randomized control trial) | Bisoprolol | Group 1 Idiopathic PAH (n = 18) | Bisoprolol demonstrated no positive effects on RV function. Additionally, there was reduced cardiac index and reduction of 6MWD that was suggestive of impaired cardiac function. |

| Farha et al.61 (randomized control trial) | Carvedilol | Groups 1, 3, and 4 PH (n = 30) | Carvedilol was well tolerated over six months in stable PH patients and demonstrated improvement in exercise induced heart rate recovery. |

| Grinnan et al.62 (prospective cohort study) | Carvedilol | Group 1 (n = 6) | Improvement in RVEF and stroke volume without changes in LVEF. |

| Provencher et al.63 (prospective cohort study) | Atenolol and propranolol | Group 1 Portopulmonary hypertension (n = 10) | BBs were associated with worsening exercise tolerance and hemodynamics. |

BB: beta blocker; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; PH: pulmonary hypertension; RV: right ventricle; RVEF: right ventricular ejection fraction; 6MWD: six minute walk distance.

Beta blocker use during ARF in CLD-PH with atrial arrythmias

BBs are likely safe to trial during AAs in hemodynamically stable CLD-PH patients with mild ARF. Albeit, there is no clinical evidence evaluating the safety or efficacy of BBs in ARF associated with CLD-PH and administration should be done with caution. The use of BBs in CLD during ARF have been evaluated only in patients with COPD. These studies have demonstrated primarily the safety profile of cardioselective BBs – with metoprolol being the most commonly used agent and with AF being the most common reason to initiate rate control therapy.65,66 Neither of these studies investigated the presence of PH within their study sample, nor effects of BBs during ARF in CLD-PH specifically. If BB therapy was to be trialed during a hemodynamically stable CLD-PH patient during an episode of ARF, a cardioselective BB would be cautiously recommended (i.e. metoprolol). BBs should be avoided in severe ARF and decompensated PH due to their negative inotropic affect and possible contribution to bronchoconstriction which may induce or potentiate hemodynamic collapse.

Calcium channel blockers

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) function as class IV antiarrhythmics that slow depolarization in slow action potential cells. The reported use of CCBs in CLD patients with AAs is generally limited to AF in COPD. Verapamil and diltiazem are commonly used as AF rate control agents, but because of negative ionotropic effects they are contra-indicated in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.4,67 Verapamil is generally avoided in PH patients due to its higher negative inotropic effects in comparison to other CCBs.68 There is no evidence on the short or long-term efficacy and safety profile in CCBs in ILD. CCBs (amlodipine, diltiazem, and nifedipine) may have benefit within a select sub-population of Group 1 PH patients; those with confirmed acute vasoreactivity on right heart catheterization, and are otherwise avoided in non-responders.69,70 One study has reported the use of CCBs during AAs in patients with idiopathic and scleroderma-associated PAH but tolerance and efficacy were not described.44 Even if CCBs were well tolerated in other forms of PH, there would be theoretical concern of worsened V/Q mismatch in CLD-PH patients due to their vasoreactive properties inhibiting local hypoxic vasoconstriction.71,72

CCB use during ARF in CLD-PH with atrial arrythmias

Currently there is not enough evidence to support routine use of CCBs in patients with CLD-PH and ARF. There may be an exception with the use of diltiazem during episodes of MAT in CLD-PH patients, but concerns related to its hemodynamic effects persist. The negative inotropic effects and the contraindication in severe left and right ventricular heart failure would make CCBs contraindicated in decompensated CLD-PH.

Digoxin

Digoxin directly inhibits myocardial Na+/K + ATPase transporters to increase intracellular calcium concentrations to improve myocardial cell contractility. Digoxin also lengthens phase 0 and 4 of the cardiac action potential, which slows heart rate, and increases vagal tone.73 Digoxin is potentially underutilized as a rate control option in AAs despite the limited data in CLD and PH. Digoxin and other cardiac glycosides may be beneficial in patients with IPF through cyclooxygenase-2 expression induction and protein kinase A activation, as well as suppression of transforming growth factor-B induced fibrotic signaling and myofibroblast differentiation.74 These benefits have primarily been suggested in vitro, which limits their current clinical application.

Digoxin use during ARF in CLD-PH with atrial arrythmias

Several studies have demonstrated that digoxin use in PH may be beneficial during acute right ventricular decompensation through its positive inotropic support and improved CO.75,76 Rich et al (1998) demonstrated that following the acute administration of digoxin in RVF from Group 1 PAH: a 10% increase in CO, a 5 mmHg increase in mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP), an increase in atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), and a decrease in plasma norepinephrine were observed.75 The increased mPAP reflects an improved right ventricular CO rather than worsening pulmonary congestion, as the pulmonary vascular resistance was unchanged. The reason for ANP elevation was unclear and needs further investigation. Another study reported that digoxin was used frequently in AF patients with COPD and had no increased risk of 1 year mortality.77 This implies that in the acute setting, digoxin appears to be safe in acute AF management in CLD patients. However, benefits from long-term use within PH remains less convincing with respect to improvement in right ventricular ejection fraction, exercise capacity, and New York Heart Association functional class.76 Digoxin should be avoided in patients with MAT.73 Digoxin benefit in atrial arrhythmia in combination with RVF and CLD needs further investigation.

Rhythm control

Amiodarone

Amiodarone functions primarily as a class III antiarrhythmic that prolongs the action potential through potassium channel blockade. It also has properties that allows it to act as a class I, II, and IV antiarrhythmic.

Amiodarone in chronic lung disease

The drug toxicity within the lungs relates to iodine accumulation that may cause acute and/or chronic inflammation. The toxicity of amiodarone can occur any time after initiation of treatment, but it has most often been found to correlate with total cumulative dose as opposed to daily dosing.78 Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity most commonly presents as acute or subacute pneumonitis with diffuse infiltrates on chest radiography or computed tomography.78 It can present in several forms including: organizing pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, alveolar hemorrhage, and chronic interstitial pneumonitis. Mechanisms for amiodarone induced pulmonary toxicity include direct cytotoxicity and hypersensitivity reaction.79 When acute pulmonary toxicity is suspected, withdrawal and consideration of corticosteroid therapy is indicated; corticosteroid therapy is less useful for chronic amiodarone toxicity.

Amiodarone use is common among patients with AF and COPD, despite its known pulmonary toxicity profile.45 Its prolonged use in ILD has not been studied and is more concerning because its association with pulmonary fibrosis has been well described. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity have a reported an incidence between 5 and 13% and a mortality rate of 10–23%. Risk factors for the development of amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity were found to be patients >60 years and on amiodarone for 6–12 months.80 Amiodarone use has been reported in PH,5–7,14 but not in CLD-PH.

Amiodarone use during ARF in CLD-PH with atrial arrythmias

There are no studies evaluating its safety with short-term use in CLD as a bridge to alternate therapy. Despite concerns regarding pulmonary toxicity, amiodarone use may be the best option when confronted by a life-threatening atrial arrhythmia in decompensated CLD-PH, especially if hypoxemia or hypotension is present.

Dronedarone

Dronedarone is derived from amiodarone with the addition of a methylsulfonyl group that is reported to result in the molecule causing less systemic toxicity. Nonetheless, there are case reports which implicate dronedarone as causing pulmonary toxicity with its use.81–83 Dronedarone-related pulmonary toxicity has also been described in patients with prior amiodarone use, which raises concerns of cross-reactivity.84 The use of dronedarone is contraindicated in patients with advanced heart failure.8 Olsson et al. have demonstrated its tolerability in PH patients during the management of AF and AFl; this study did not include CLD-PH. Theoretically dronedarone may be a safer alternative to amiodarone use.

Sotalol

Sotalol is a BB that also has class III antiarrhythmic properties. There have been reported associations between sotalol and the development of bronchiolitis obliterans.85 The negative inotropic effects of sotalol would limit its use in decompensated PH. However, this agent may be potential option for mild ARF in otherwise stable CLD-PH patients.

Class 1c agents

One small retrospective study of AAs in 77 PH patients demonstrated no adverse events with the use of class 1c agents, such as propafenone and flecainide.6 This study only had 12 patients with Group 3 PH and it was unclear how many of these patients actually received class 1c agents. Propafenone and flecainide are contraindicated in patients with structural heart disease but it is not clear if this concern applies to patients with PH. Flecainide has a rare association with diffuse infiltrative lung disease.53,86,87 There is theoretical potential for use of these agents in ARF patients with CLD-PH and further investigation is warranted.

Cardioversion

Patients who are hemodynamically unstable due to AAs should promptly undergo synchronized direct current cardioversion (DCCV).88 Two studies have reported success with electrical cardioversion of AAs in PH patients, however patients frequently need repeated attempts to achieve success.7,14 Both these studies were low powered and did not include CLD-PH. Olsson et al (2013) also reported success with elective cardioversion used in combination with pharmacological rhythm control therapy.14 An exception to the use of DCCV is in the setting of MAT, where it has not been described to be effective.89

Cardiac catheter ablation

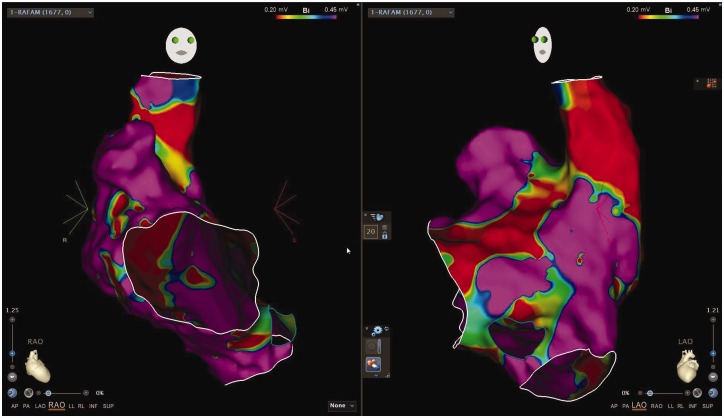

Cardiac catheter ablation (CCA) is a definitive approach to managing AAs. CCA include two techniques: radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) and cryoballoon ablation. Typically, the cryoballoon ablation is used in pulmonary vein isolation and is not commonly used in patients with CLD or PH. CLD-PH patients have more NPVF as their source of arrhythmogenic substrate and there is less need of pulmonary vein isolation. Unlike RFCA, no studies have investigated outcomes with cryoballoon ablation specifically in PH patients. Fig. 3 demonstrates an example of an electrophysiology study used to guide RFCA in a patient with CLD-PH complicated by an AA.

Fig. 3.

Voltage map of a patient with atrial arrhythmias and COPD associated pulmonary hypertension. Voltage map demonstrating right anterior oblique (RAO) and left anterior oblique (LAO) views of the right atrium, superior vena cava, and inferior vena cava. Purple reflects areas of normal voltage and red demonstrates extensive scarring and fibrosis. Mild to moderate scarring and fibrosis are delineated by areas of green and yellow. This patient's extensive fibrosis and scarring resulted in multiple NPVF that lead to multiple atrial arrhythmias including focal atrial tachycardia, atrial flutter, and atrial fibrillation. This mapping was from a second attempt at radiofrequency catheter ablation which was extensive but ultimately successful in suppressing further atrial arrhythmias with two years from procedure, confirmed by implanted loop recorder.

In the acute setting, CCA is often used during AAs that are refractory to medical management or when there are contraindications to medical therapy. RFCA can be performed as safely in CLD patients as in patients with normal lungs.1

Although no study has evaluated the safety and efficacy of CCA in CLD-PH patients, there is data in other subtypes of PH to suggest that RFCA is a safe and effective intervention. While RFCA in PH patients has been demonstrated to be safe,35,90 it is frequently technically challenging due to right atrial and tricuspid annular dilation.8 Two small retrospective studies have demonstrated that PAH patients have longer RFCA procedure times, required higher numbers of lesions ablated, and had longer total ablation times.35,91 Other risks associated with CCA in PH patients include increased risks of in-hospital death, pneumonia, cardiac arrest, and type III AV block.92

Cardiac tamponade is the most common life threatening complication from CCA.93 Additional serious procedural risks include pulmonary vein stenosis, cardiac perforation, esophageal fistulas, and major bleeding.94 Severely elevated right heart pressures and dilated right heart chambers increase the risk for transeptal or free wall puncture during CCA. Downstream complications from this procedure include right-to-left shunting with worsening hypoxemia and increased risk of paradoxical embolism.8 Cryoballoon ablation could, theoretically, put more patients at increased risk for right-to-left shunting in comparison to RFCA due to its requirement of a larger sheath that is used during septal puncturing. Two case reports, one patient with PH, have described complications of a right-to-left shunt post ablation that responded well to atrial septal defect closure closure.95,96 It is sensible to assume patients with PH would be at greater theoretical risk for the development of right-to-left shunting due to their increased right atrial pressures. The use of transesophageal echocardiography or intracardiac echocardiography have been shown to reduce major complications from CCA.97 Another consideration for the proceduralist and anesthesiologist is that general anesthesia or deep sedation is worrisome in decompensated PH patients.

Anesthetic risks include worsening hemodynamics that may be compounded by the application of mechanical ventilation.

Often repeat RFCAs are required to control AAs and atrioventricular node ablation with need for permanent pacemaker insertion is common.37 Patients with severe PH requiring CCA should have the procedure performed under specialist cardiac anesthesia, and general expert opinion recommends that mechanical ventilation in combination with deep sedation and/or general anesthesia during severe ARF should be avoided, if possible.98

Anticoagulation

Currently there is no evidence on the anticoagulation risks and benefits within CLD-PH patients. Additionally, there is no evidence to guide whether direct oral anticoagulation agents (DOACs) or vitamin K antagonist should be used as first line. The applicability of the CHA2DS2VASc scoring system for stroke risk assessment or the HAS-BLED scoring system for bleeding risk assessment is uncertain in PH patients with AF. However, the utilization of these scoring systems in CLD-PH patients with AF is pragmatic. AFl follows the same anticoagulation management guidelines as AF.99 There is no evidence to recommend anticoagulation in MAT.

The ARISTOTLE trial was a randomized control trial that compared the efficacy of apixaban and warfarin in patients with AF and AFl.100 Within this trial COPD patients were independently associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality, but they were not associated with increased risk of stroke or systemic embolism.101 There was also no difference in the efficacy or bleeding events between the use of apixaban or warfarin. COPD patients have been demonstrated to have increased warfarin sensitivity, when therapy is started during an exacerbation.102

A double blinded randomized control trial of 145 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) reported higher mortality in patients treated with warfarin in comparison to those without.103 The most common cause of death was found to be respiratory related. This study was predicated on animal studies that inferred a correlation between IPF and hypercoagulability, and IPF patients with atrial arrhythmias were excluded. A small case series has described two patients with fatal IPF exacerbations secondary to warfarin use.104 The indications for warfarin in these two cases were AF and DVT. Thus, the use of warfarin in IPF patients should be with caution and close monitoring. It is unclear how warfarin affects other ILD subtypes.

While PH patients were not specifically excluded from trials investigating the rationale of DOACs as a first line anticoagulant agents, there is not enough data to suggest that DOACs should be used first line in all patients with PH and atrial fibrillation.8 In the ARISTOTLE trial, PH was not associated with higher mortality in AF/AFl patients with COPD or in all-cause mortality.101 PH is a heterogeneous disease with variability in the perceived benefits of anticoagulation within its various subtypes. This indicates need of further investigation of anticoagulation management within the various PH subtypes. Current recommendations would advise anticoagulation in CLD-PH patients with AF or AFl and agent for anticoagulation should be determined on an individualized basis.

Conclusion

CLD-PH is often complicated by AAs and there is little evidence to guide arrythmia management during ARF. Current recommendation would reinforce guidelines that focus primarily on attempting to restore sinus rhythm and considering RFCA if possible. Rate control methods should be avoided in decompensated PH patients due to risks of further hemodynamic collapse and potential for side effects of treatment agents. Anticoagulation should be considered in any patient with atrial fibrillation or flutter and choice of specific therapy should be determined on an individual basis. These issues highlight an ongoing need for further investigation on AAs management in CLD-PH.

Authors’ contribution

All authors contributed substantially in the drafting and editing of this manuscript to insure its accuracy.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD

Cyrus A. Vahdatpour https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8917-2807

References

- 1.Roh S-Y, Choi J-I, Lee JY, et al. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with chronic lung disease. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011; 4: 815–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery J-L, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nathan SD, Barbera JA, Gaine SP, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic lung disease and hypoxia. Eur Respir J 2018, pp. 1801914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goudis CA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atrial fibrillation: an unknown relationship. J Cardiol 2017; 69: 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen L, Sun M-L, An P, et al. Frequency of supraventricular arrhythmias in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2014; 114: 1420–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannillo M, Grosso Marra W, Gili S, et al. Supraventricular arrhythmias in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2015; 116: 1883–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tongers J, Schwerdtfeger B, Klein G, et al. Incidence and clinical relevance of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias in pulmonary hypertension. Am Heart J 2007; 153: 127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wanamaker B, Cascino T, McLaughlin V, et al. Atrial arrhythmias in pulmonary hypertension: pathogenesis, prognosis and management. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2018; 7: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S, Je NK. Antithrombotic therapy underutilization in patients with atrial flutter. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2018; 23: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamaguchi T, Tsuchiya T, Miyamoto K, et al. Characterization of non-pulmonary vein foci with an EnSite array in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Europace 2010; 12: 1698–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Y-K, Lai M-S, Chen Y-C, et al. Hypoxia and reoxygenation modulate the arrhythmogenic activity of the pulmonary vein and atrium. Clin Sci 2012; 122: 121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cirulis MM, Ryan JJ, Archer SL. Pathophysiology, incidence, management, and consequences of cardiac arrhythmia in pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ 2019; 9: 204589401983489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nattel S, Burstein B, Dobrev D. Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation: mechanisms and implications. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2008; 1: 62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsson KM, Nickel NP, Tongers J, et al. Atrial flutter and fibrillation in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2013; 167: 2300–2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medi C, Kalman JM, Ling L-H, et al. Atrial electrical and structural remodeling associated with longstanding pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy in humans. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2012; 23: 614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heindl S, Lehnert M, Criée CP, et al. Marked sympathetic activation in patients with chronic respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciarka A, Doan V, Velez-Roa S, et al. Prognostic significance of sympathetic nervous system activation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181: 1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan W, Nie S, Wang H, et al. Anticholinergics aggravate the imbalance of the autonomic nervous system in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med 2019; 19: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Gestel AJR, Steier J. Autonomic dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J Thorac Dis 2010; 2: 215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bristow MR, Anderson FL, Port JD, et al. Differences in beta-adrenergic neuroeffector mechanisms in ischemic versus idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1991; 84: 1024–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francis GS, McDonald KM, Cohn JN. Neurohumoral activation in preclinical heart failure. Remodeling and the potential for intervention. Circulation 1993; 87: IV9096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann DL, Kent RL, Parsons B, et al. Adrenergic effects on the biology of the adult mammalian cardiocyte. Circulation 1992; 85: 790–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merkus D, de Beer VJ, Houweling B, et al. Control of pulmonary vascular tone during exercise in health and pulmonary hypertension. Pharmacol Ther 2008; 119: 242–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyman AL, Lippton HL, Kadowitz PJ. Analysis of pulmonary vascular responses in cats to sympathetic nerve stimulation under elevated tone conditions. Evidence that neuronally released norepinephrine acts on alpha 1-, alpha 2-, and beta 2adrenoceptors. Circ Res 1990; 67: 862–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engel TR, Radhagopalan S. Treatment of multifocal atrial tachycardia by treatment of pulmonary insufficiency. Chest 2000; 117: 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santillo E. Multifocal atrial tachycardia: looking for new solutions to an old problem. Int J Heart Rhythm 2017; 2: 58. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falk JA, Kadiev S, Criner GJ, et al. Cardiac disease in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008; 5: 543–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudson LD, Kurt TL, Petty TL, et al. Arrhythmias associated with acute respiratory failure in patients with chronic airway obstruction. Chest 1973; 63: 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCord J, Borzak S. Multifocal atrial tachycardia. Chest 1998; 113: 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai YH, Lee CJ, Lan RS, et al. Multifocal atrial tachycardia as a prognostic indicator in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring mechanical ventilation. Chang Yi Xue Za Zhi 1991; 14: 163–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Gaal WJ, Couthino B, Chan M, et al. The safety and tolerability of adenosine in patients with obstructive airways disease. Int J Cardiol 2008; 128: 436–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao X, Han H, Wu C, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in hospital encounters with end-stage COPD on home oxygen. Chest 2019; 155: 918–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C-Y, Liao K-M. The impact of atrial fibrillation in patients with COPD during hospitalization. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018; 13: 2105–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konecny T, Park JY, Somers KR, et al. Relation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol 2014; 114: 272–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luesebrink U, Fischer D, Gezgin F, et al. Ablation of typical right atrial flutter in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Heart Lung Circ 2012; 21: 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Małaczyńska-Rajpold K, Komosa A, Błaszyk K, et al. The management of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Heart Lung Circ 2016; 25: 442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanmanthareddy A, Reddy YM, Boolani H, et al. Incidence, predictors, and clinical course of atrial tachyarrhythmias in patients with pulmonary hypertension. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2014; 41: 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernández Pérez ER, Daniels CE, St. Sauver J, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and clinical course of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2010; 137: 129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hyldgaard C, Hilberg O, Bendstrup E. How does comorbidity influence survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis?. Respir Med 2014; 108: 647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy D, Talajic M, Nattel S, et al. Rhythm control versus rate control for atrial fibrillation and heart failure. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2667–2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noheria A, Shrader P, Piccini JP, et al. Rhythm control versus rate control and clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2016; 2: 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caldeira D, David C, Sampaio C. Rate versus rhythm control in atrial fibrillation and clinical outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2012; 105: 226–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savale L, Weatherald J, Jaïs X, et al. Acute decompensated pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2017; 26: 170092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mercurio V, Peloquin G, Bourji KI, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and atrial arrhythmias: incidence, risk factors, and clinical impact. Pulm Circ 2018; 8: 204589401876987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durheim MT, Holmes DN, Blanco RG, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atrial fibrillation. Heart 2018; 104: 1850–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwarzkopf L, Witt S, Waelscher J, et al. Associations between comorbidities, their treatment and survival in patients with interstitial lung diseases – a claims data analysis. Respir Res 2018; 19: 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.You SC, An MH, Yoon D, et al. Rate control and clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and obstructive lung disease. Heart Rhythm 2018; 15: 1825–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maltais F, Buhl R, Koch A, et al. β-Blockers in COPD. Chest 2018; 153: 1315–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duffy S, Marron R, et al. Effect of beta-blockers on exacerbation rate and lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Respir Res 2017; 18: 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newnham DM, Wheeldon NM, Lipworth BJ, et al. Single dosing comparison of the relative cardiac beta 1/beta 2 activity of inhaled fenoterol and salbutamol in normal subjects. Thorax 1993; 48: 656–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nielsen AO, Pedersen L, Sode BF, et al. β-Blocker therapy and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a Danish Nationwide Study of 1·3 Million Individuals. EClinicalMedicine 2019; 7: 21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhatt SP, Wells JM, Kinney GL, et al. β-Blockers are associated with a reduction in COPD exacerbations. Thorax 2016; 71: 8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwaiblmair M. Drug induced interstitial lung disease. Open Respir Med J 2012; 6: 63–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lipworth B, Wedzicha J, Devereux G, et al. Beta-blockers in COPD: time for reappraisal. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 880–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perros F, de Man FS, Bogaard HJ, et al. Use of β-blockers in pulmonary hypertension. Circ Heart Fail 2017; 10: e003703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bogaard HJ, Natarajan R, Mizuno S, et al. Adrenergic receptor blockade reverses right heart remodeling and dysfunction in pulmonary hypertensive rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182: 652–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thenappan T, Roy SS, Duval S, et al. β-Blocker therapy is not associated with adverse outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a propensity score analysis. Circ Heart Fail 2014; 7: 903–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bandyopadhyay D, Bajaj NS, Zein J, et al. Outcomes of β-blocker use in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a propensity-matched analysis. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 750–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.So PP-S, Davies RA, Chandy G, et al. Usefulness of beta-blocker therapy and outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2012; 109: 1504–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Campen JSJA, de Boer K, van de Veerdonk MC, et al. Bisoprolol in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: an explorative study. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farha S, Saygin D, Park MM, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension treatment with carvedilol for heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. JCI Insight 2017; 2: e95240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grinnan D, Bogaard H-J, Grizzard J, et al. Treatment of group I pulmonary arterial hypertension with carvedilol is safe. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 1562–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Provencher S, Herve P, Jais X, et al. Deleterious effects of beta-blockers on exercise capacity and hemodynamics in patients with portopulmonary hypertension. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crystal GJ, Pagel PS. Right ventricular perfusion: physiology and clinical implications. Anesthesiology 2018; 128: 202–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Neef PA, Burrell LM, McDonald CF, et al. Commencement of cardioselective betablockers during hospitalisation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: β-blockers in acute exacerbation of COPD. Intern Med J 2017; 47: 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kargin F, Takir HB, Salturk C, et al. The safety of beta-blocker use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with respiratory failure in the intensive care unit. Multidiscip Respir Med 2014; 9: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 2893–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Medarov BI, Judson MA. The role of calcium channel blockers for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: how much do we actually know and how could they be positioned today?. Respir Med 2015; 109: 557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zierer A, Voeller RK, Melby SJ, et al. Impact of calcium-channel blockers on right heart function in a controlled model of chronic pulmonary hypertension. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2009; 26: 253–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sitbon O, Humbert M, Jaïs X, et al. Long-term response to calcium channel blockers in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2005; 111: 3105–3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schilz R, Rich S. Calcium channel blocker therapy: when a drug works, it works. when it doesn't, it doesn't. Adv Pulm Hypertens 2017; 15: 184–189. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saadjian AY, Philip-Joet FF, Vestri R, et al. Long-term treatment of chronic obstructive lung disease by Nifedipine: an 18-month haemodynamic study. Eur Respir J 1988; 1: 716–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gheorghiade M, Adams KF, Colucci WS. Digoxin in the management of cardiovascular disorders. Circulation 2004; 109: 2959–2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.La J, Reed EB, Koltsova S, et al. Regulation of myofibroblast differentiation by cardiac glycosides. Am J Physiol-Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2016; 310: L815–L823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rich S, Seidlitz M, Dodin E, et al. The short-term effects of digoxin in patients with right ventricular dysfunction from pulmonary hypertension. Chest 1998; 114: 787–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alajaji W, Baydoun A, Al-Kindi SG, et al. Digoxin therapy for cor pulmonale: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol 2016; 223: 320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu S, Yang Y, Zhu J, et al. Predictors of digoxin use and risk of mortality in ED patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Emerg Med 2017; 35: 1589–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wolkove N, Baltzan M. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Can Respir J 2009; 16: 43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schwaiblmair M, Berghaus T, Haeckel T, et al. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity: an under-recognized and severe adverse effect?. Clin Res Cardiol 2010; 99: 693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ernawati DK, Stafford L, Hughes JD. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 66: 82–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hernández Voth AR, Catalán JS, Benavides Mañas PD, et al. A 73-year-old man with interstitial lung disease due to dronedarone. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186: 201–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stack S, Nguyen D-V, Casto A, et al. Diffuse alveolar damage in a patient receiving dronedarone. Chest 2015; 147: e131–e133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Siu C-W. Fatal lung toxic effects related to dronedarone use. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172: 516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Naccarelli G, Kowey P. The role of dronedarone in the treatment of atrial fibrillation/flutter in the aftermath of PALLAS. Curr Cardiol Rev 2014; 10: 303–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Faller M, Quoix E, Popin E, et al. Migratory pulmonary infiltrates in a patient treated with sotalol. Eur Respir J 1997; 10: 2159–2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pesenti S, Lauque D, Daste G, et al. Diffuse infiltrative lung disease associated with flecainide. Report of two cases. Respir Int Rev Thorac Dis 2002; 69: 182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Huang HD, Pietrasik GM, Serafini NJ, et al. Drug-induced acute pneumonitis following initiation of flecainide therapy after pulmonary vein isolation ablation in a patient with mitral stenosis and previous chronic amiodarone use. Hear Case Rep 2019; 5: 53–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Matthews J, McLaughlin V. Acute right ventricular failure in the setting of acute pulmonary embolism or chronic pulmonary hypertension: a detailed review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Curr Cardiol Rev 2008; 4: 49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Page RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2016; 133: e506–e574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Showkathali R, Tayebjee MH, Grapsa J, et al. Right atrial flutter isthmus ablation is feasible and results in acute clinical improvement in patients with persistent atrial flutter and severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2011; 149: 279– 280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bradfield J, Shapiro S, Finch W, et al. Catheter ablation of typical atrial flutter in severe pulmonary hypertension. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2012; 23: 1185–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Steinbeck G, Sinner MF, Lutz M, et al. Incidence of complications related to catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter: a nationwide in-hospital analysis of administrative data for Germany in 2014. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 4020–4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chun KRJ, Perrotta L, Bordignon S, et al. Complications in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in 3,000 consecutive procedures. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2017; 3: 154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen Y-H, Lu Z-Y, Xiang Y, et al. Cryoablation vs. radiofrequency ablation for treatment of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EP Eur 2017; 19: 784–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aznaouridis K, Hobson N, Rigg C, et al. Emergency percutaneous closure of an iatrogenic atrial septal defect causing right-to-left shunt and severe refractory hypoxemia after pulmonary vein isolation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015; 8: e179–e181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee A, Mahadevan VS, Gerstenfeld EP. Iatrogenic atrial septal defect with right-toleft shunt following atrial fibrillation ablation in a patient with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Hear Case Rep 2018; 4: 159–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bhat T, Baydoun H, Asti D, et al. Major complications of cryoballoon catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation and their management. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2014; 12: 1111–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hoeper MM, Benza RL, Corris P, et al. Intensive care, right ventricular support and lung transplantation in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2018; 53: 1801906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Herzog E, Argulian E, Levy SB, et al. Pathway for the management of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2017; 16: 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lopes RD, Alexander JH, Al-Khatib SM, et al. Apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial: design and rationale. Am Heart J 2010; 159: 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Durheim MT, Cyr DD, Lopes RD, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with atrial fibrillation: Insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. Int J Cardiol 2016; 202: 589–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.del Campo M, Roberts G. Changes in warfarin sensitivity during decompensated heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Pharmacother 2015; 49: 962–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Noth I, Anstrom KJ, Calvert SB, et al. A placebo-controlled randomized trial of warfarin in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186: 88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Alagha K, Secq V, Pahus L, et al. We should prohibit warfarin in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191: 958–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]