Abstract

Background and Aims:

It has been proposed that many smokers switch to vaping because their nicotine addiction makes this their only viable route out of smoking. We compared indicators of prior and current cigarette smoking dependence and of relapse in former smokers who were daily users of nicotine vaping products (‘vapers’) or who were not vaping at the time of survey (‘non-vapers’).

Design:

Cross sectional survey-based comparison between vaping and non-vaping former smokers, including a weighted logistic regression of vaping status onto predictor variables, adjusting for covariates specified below.

Setting:

US, Canada, Australia, England

Participants:

1070 people aged 18+ years from the 2016 ITC 4 Country Smoking and Vaping Wave 1 Survey who reported having ever been daily smokers but who stopped less than two years ago and who were currently vapers or non-vapers.

Measurements:

Dependent variable was current vaping status. Predictor variables were self-reported: 1) smoking within five minutes of waking and usual daily cigarette consumption, both assessed retrospectively; 2) current perceived addiction to smoking, urges to smoke and confidence in staying quit. Covariates: country, sample sources, sex, age group, ethnicity, income, education, current nicotine replacement therapy use, and time since quitting.

Findings:

Vapers were more likely than non-vapers to report: 1) having smoked within five minutes of waking (34.3%vs.15.9%, AOR=3.74(95%CI:1.99,7.03), chi-square=16.92, p<0.001); having smoked >10 cigarettes/day (74.4%vs.47.2%, AOR=4.39(95%CI:2.22,8,68), chi-square=18.18,p<0.001); 2) perceiving themselves to be still very addicted to smoking (41.3%vs.26.2%, AOR=2.89(95% CI:1.58,5.30), chi-square=11.87, p<0.001) and feeling extremely confident about staying quit (62.1%vs.36.6%, AOR=3.22(95% CI:1.86,5.59), chi-square=17.36,p<0.001). Vapers were not more likely to report any urges to smoke than non-vapers (27.7%vs.38.8%, AOR=0.86(95% CI:0.44,1.65), chi-square=0.21,p=0.643).

Conclusions:

While former smokers who currently vape nicotine daily report higher levels of cigarette smoking dependence pre- and post-cessation, compared with former smokers who are current non-vapers, they report greater confidence in staying quit and similar strength of urges to smoke.

Introduction

Given the enormous health risks posed by cigarette smoking, it seems clear that switching completely to non-combustible nicotine products will reduce health risks compared with continued smoking(1–3). In many countries, nicotine vaping has become a popular method used by smokers to stop smoking cigarettes(4, 5). In other words, vaping has meant that some smokers are stopping smoking by switching completely to nicotine vaping products (NVP), similar to how some smokers stop by switching to nicotine replacement therapies (NRT), such as gum or lozenge(6, 7).

It has been proposed that many smokers switch to vaping because their addiction to nicotine makes this their only viable route out of smoking. Former smokers who vape report retrospectively that they had smoked for a longer duration and had higher consumption and dependence compared with a similar sample of smokers(8). Vaping appears to address both nicotine withdrawal and some of the learned behavioural aspects of smoking that make giving up cigarettes difficult for smokers. For example, studies have found that satisfaction or enjoyment from vaping were associated with not smoking and continued vaping or intentions to continue vaping (9–11). In addition, qualitative research studies report that NVPs provide a substitute for many of the physical, behavioural, and social aspects previously enjoyed from smoking(12, 13), and that vaping might interrupt the known pathway between lapse and relapse(14).

In a recent trial involving smokers attending specialist behavioural support cessation services(15), smokers were randomized to use either NVP or NRT. Those using NVP were about twice more likely to remain cigarette-abstinent than NRT. It was also found that the percentage of participants who continued their NVP use was greater than the rate of continued NRT use. This pattern of findings points to the importance of continued NVP use in ameliorating withdrawal symptoms, and possibly in maintaining positive effects previously obtained from smoking. These findings are consistent with other studies that have examined the relation between cigarette smoking craving/dependence and vaping. For example, greater reductions in craving to smoke have been found among vapers than NRT users((16, 17) despite, in the latter study, roughly similar nicotine intake to cigarette smoking among both groups(18). The psychoactive effects of some NVPs (19) may also sustain NVP use after switching. Several studies have examined dependence on vaping versus prior dependence on smoking(9, 20–23), or dependence in vapers compared with similar samples of smokers((24, 25), consistently finding lower vaping dependence.

To our knowledge, no studies have compared indicators of prior or current dependence on smoking, or likelihood of relapse, among former smokers who vape versus those who do not vape. Data for this study come from the 2016 ITC 4 Country Smoking and Vaping Wave 1 Survey (4CV1). We used indicators of cigarette smoking dependence shown to be predictive of smoking cessation (time to first cigarette, usual daily cigarette consumption and perceived addiction to smoking)(26–28), or relapse (self-efficacy in remaining quit and urges to smoke)(29, 30). The sample was limited to former smokers (i.e., ever daily smokers) who quit in the previous two years. The research questions addressed: 1) Do recent former smokers who currently vape nicotine daily (vapers) differ from former smokers who do not currently vape (non-vapers) in time to first cigarette and usual cigarette consumption when they were smoking reported retrospectively? 2) Do vapers differ from non-vapers, when surveyed, on perceived addiction to smoking, urges to smoke and confidence in their ability to stay quit?

Methods

Sample

Data are from the ITC 4CV1 survey collected in 2016 from four countries: Australia (AU), Canada (CA), England (EN), and the United States (US). Methodological details are available via the ITC website (http://www.itcproject.org/methods) and in Thompson et al (31). In brief, the 4CV1 sample retained participants from the original ITC 4C survey (conducted 2002–2015) who met eligibility criteria and recruited new participants who were current smokers or vapers or who had quit smoking within the last two years from country-specific panels. In CA, EN, and US there was over-sampling of those aged 18–24 years old and/or those with experience of vaping, but this was done in a way that allowed us to weight the samples back to reference representative surveys. In addition, a supplementary dedicated vaper sample was recruited in AU from online vaper forums and vape stores (AU CCV sample). We included this sample in our analyses in order to have a large enough sample of former smokers overall and particularly from AU where NVPs are effectively banned from retail sale. The data were weighted to be representative of former smokers in CA, US, and EN irrespective of whether they vaped or not; for AU, non-vapers had an initial weight to make them representative of AU former smokers, but vapers were given a weight to make them representative of current vapers in AU (irrespective of whether respondents were from the CCV sample or not).

Measures

Former smokers were those responding ‘not at all, I’ve quit smoking completely’ to the following question: ‘How often, if at all, do you CURRENTLY smoke ordinary cigarettes (either factory-made or roll-your-own’. To be eligible, they also responded positively to a question whether they were ever daily smokers.

In this study, we were interested in examining whether former smokers who were substituting their nicotine from combustible cigarettes through regular daily vaping differed from those who were not vaping. As a result, we excluded from our analyses current vapers who did not vape daily or who vaped a non-nicotine containing product. Current daily vapers were identified according to whether those that responded ‘daily’ to the following question: ‘How often, if at all, do you CURRENTLY use e-cigarettes/vaping devices (i.e. vape)? Current non-vapers were identified as those who responded ‘not at all’, and they were also asked if they had ever vaped and if so, how frequently.

Vaping nicotine was assessed using the question: ‘What is the strength of the e-liquid you currently use most? No nicotine- 0mg/ml; 1–4 mg/ml (0.1–0.4%); 5–8 mg/ml (0.5–0.8%); 9–14 mg/ml (0.9–1.4%); 15–20 mg/ml (1.5–2.0%); 21–24 mg/ml (2.1–2.4%); 25 mg/ml (2.5%) or more); refused; don’t know. For those responding ‘refused’ or ‘don’t know’, they were asked ‘Can you tell us the rated strength of the e-liquid you [use most]/[last used] (often written on the package or cartridges)? No nicotine; low/light; medium/regular. All those responding ‘no nicotine’, or ‘refused/don’t know’ followed by ‘no nicotine’ were excluded. Thus, the two analytical samples were former smokers who were ever daily smokers, who currently vaped nicotine daily (vapers), or who currently did not vape (non-vapers).

Predictor measures

Four measures of cigarette smoking dependence were assessed in the ITC 4CV1 survey, two retrospectively and two at the time of the survey, as well as one measure of self-efficacy at the time of the survey.

Time to first cigarette (TTFC) when smoking:

This measure is taken from the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD,(32)) and Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI,((33)), and it has been shown to have the greatest validity of the FTCD and HSI measures for smoking cessation and relapse(26). All former smokers were asked ‘Thinking about when you used to smoke, how soon after waking did you usually smoke your first cigarette? with the response completed in minutes or hours as appropriate. The distribution of time to first cigarette data were skewed and for the analysis, these were classified as a binary outcome, and we modelled odds of first cigarette within 5 minutes vs more than 5 minutes.

Usual cigarette consumption when smoking:

This measure is taken from the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence(32) and together with TTFC forms the HSI, which accounts for much of the predictive validity of the FTCD(33). All former smokers were asked ‘Now thinking about the months before you quit smoking [and were not vaping regularly], on average, how many cigarettes did you smoke?’ Respondents could answer with cigarettes/day or cigarettes/week and cigarettes/day was derived for all, which was then classified into two categories, ≤ 10 cigarettes/day, more than 10 cigarettes/day (given usual daily cigarette consumption among smokers in 2016 in England averaged 11 cigarettes)..

Perceived addiction at the time of the survey:

This measure is from the Cigarette Dependence Scale 5 and 12(27), and the only one from that Scale in a recent study to predict smoking cessation in addition to HSI((34). The measure used here was adapted to be in line with other ITC questions and asked of all former smokers: ‘Do you consider yourself addicted to cigarettes: Not at all, yes- somewhat addicted, yes-very addicted, refused, don’t know’). We modelled the odds of being ‘very addicted’ vs. otherwise with don’t know/refused coded as missing and excluded.

Urges to smoke at the time of the survey:

The measure used was based on the Strength of Urges to Smoke Scale found by Fidler and colleagues(35) to be the strongest predictor from a number of dependence measures included at baseline, of success of subsequent quit attempts. We combined their two questions into one, with six possible responses. Thus for all former smokers, urges to smoke were assessed: ‘In general, how strong have urges to smoke been in the last 24 hours: I have not felt the urge to smoke in the last 24 hours, slight, moderate, strong, very strong, extremely strong, refused, don’t know’. We modelled the odds of having any urges (slight/moderate/strong/very/extremely strong to smoke) vs. no urges, given the preponderance of reporting no urges to smoke in the last 24 hours, with don’t know/refused excluded.

Confidence in quitting at the time of the survey:

This measure has found to be predictive of relapse(29), (as have other similar measures eg(36, 37). All former smokers were asked ‘How confident are you that you will remain a non-smoker? Not at all confident, slightly, moderately, very, extremely, refused, don’t know’. We modelled the odds of feeling ‘extremely confident’ vs. other options, with don’t know/refused excluded.

Covariates

Other measures were: country (AU, CA, EN, US); sample source (ITC continuing cohort, commercial firm, AU CCV sample); sex (male, female); age group (18–24, 25–39, 40–54, 55+); ethnicity (white/English, minority group); income (low, moderate, high, not stated); education (low, moderate, high); current NRT use (not at all, < weekly, at least once/week); time since quitting (in last 3 months, 4–12 months ago, 1–2 years ago). Don’t know/refused responses were coded as missing and excluded, except for income, where don’t know/refused responses were categorized as ‘not stated’.

Modelling Approach

We estimated weighted logistic regression models using SUDAAN Version 11.0.1 to examine the association between vaping status, and each of the predictors controlling for all covariates listed above. We carried out a sensitivity analysis by removing the AU CCV sample. Don’t know/refused responses were coded as missing. All cases with missing data were excluded from the analysis, using casewise deletion. There were 36 missing cases for analysis 1), 5 for analysis 2), 44 for analysis 3), two for analysis 4) and one for analysis 5). There were nine missing cases for ethnicity, 11 for education and no missing data on the other covariates.

In relation to objective 1) based on prior literature, we would expect that vapers would be more likely to have been more dependent smokers prior to quitting, i.e. smoked within five minutes of waking and had higher cigarette consumption when smoking. In relation to objective 2) based on prior literature, we would expect vapers to have fewer urges to smoke. Given the lack of prior literature we were unsure whether vapers and non-vapers would differ in relation to perceived addiction to smoking and confidence in ability to stay quit at the time of the survey. In relation to covariates, we predicted that former smokers who had been quit for a longer time would have reported lower retrospective measures of smoking dependence, lower perceived addiction to smoking and urges to smoke and higher confidence in ability to stay quit.

Results

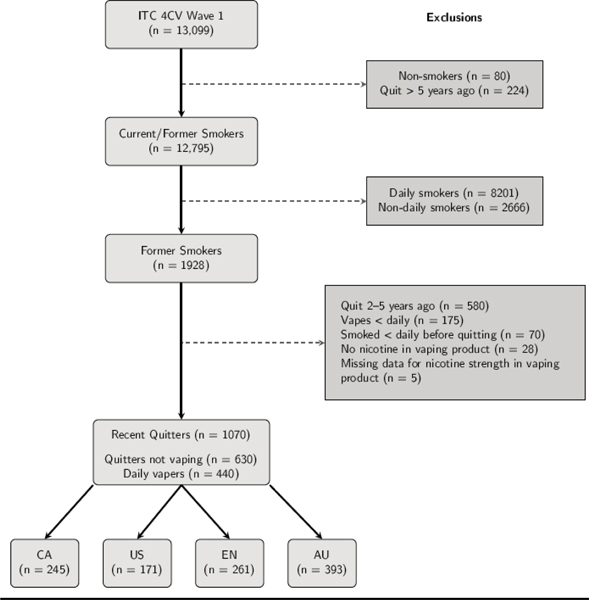

Figure 1 gives an overview of the analytic sample. We began with the core sample of 13,099 participants and excluded 8,201 daily and 2,666 non-daily smokers, 80 non-smokers, 804 former smokers who stopped smoking more than two years ago (because they were not assessed on cigarette smoking dependence measures), 175 who smoked less than daily before quitting, 175 former smokers who vaped less than daily and 5 who responded don’t know/refused to the nicotine strength questions. This resulted in an analytical sample of 1,070 former smokers who had ever smoked daily.

Figure 1.

Configuration of analytic sample

Of the 1,070 former ever daily smokers, 245 were from Canada (CA), 171 United States (US), 261 England (EN) and 393 Australia (AU) (Table S1). Overall, 440 (41.1%) were classified as daily nicotine vapers (vapers) and 630 (58.9%) were current non-vapers. Of the 1,070 former smokers, 54% male, 90% white ethnicity, 49% high income and a fifth (20%) had quit in the last 3 months, 39% 4–12 months ago and 40% 1–2 years ago. There were significant differences between vapers and non-vapers on country and sample source, but not socio-demographics (Table 1). Whilst just under half vapers (44.5%) quit 4–12 months ago, compared with 34.1% non-vapers, the differences in time since quit across the two groups were not statistically significant. Among the non-vapers, 24.8% (n=166) had previously been at least weekly vapers, 17.9% (107) had vaped only occasionally, 8.3% (51) vaped only once and 49.0% (306) had never vaped. The regression models were based on 1009 to 1051 respondents when taking into account missing data.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by vaping status (Weighted, n=1070)

| Vaper | Non-vaper | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristic | n | % | (95% | CI) | n | % | (95% | CI) | Wald F* | DF | p |

| Country | |||||||||||

| Canada | 34 | 11.1 | (7.7, | 15.6) | 211 | 23.3 | (20.8, | 26.1) | 17.16 | 3 | <.001 |

| United States | 36 | 25.5 | (17.0, | 36.5) | 135 | 17.6 | (15.1, | 20.4) | |||

| United Kingdom | 87 | 53.5 | (44.4, | 62.3) | 174 | 21.1 | (18.4, | 24.1) | |||

| Australia | 283 | 10 | (8.2, | 12.1) | 110 | 38.0 | (32.9, | 43.3) | |||

| Samplesource | |||||||||||

| ITC cohort | 24 | 10 | (5.9, | 16.3) | 101 | 13.8 | (10.7, | 17.8) | 216.53 | 2 | <.001 |

| Commercial firm | 154 | 80.8 | (74.6, | 85.8) | 529 | 86.2 | (82.2, | 89.3) | |||

| CCV vaper | 262 | 9.2 | (7.5, | 11.2) | 0 | 0.0 | |||||

| Female | |||||||||||

| Male | 275 | 50.9 | (41.1, | 60.7) | 305 | 55.6 | (50.1, | 60.9) | 0.64 | 1 | 0.422 |

| Female | 165 | 49.1 | (39.3, | 58.9) | 325 | 44.4 | (39.1, | 49.9) | |||

| Agegroup | |||||||||||

| 18–24 | 37 | 16.9 | (9.3, | 28.6) | 58 | 9.3 | (6.3, | 13.7) | 1.59 | 3 | 0.19 |

| 25–39 | 156 | 27.8 | (19.4, | 38.1) | 155 | 39.0 | (33.5, | 44.8) | |||

| 40–54 | 144 | 28.4 | (20.9, | 37.3) | 182 | 28.2 | (24.0, | 32.7) | |||

| 55 and up | 103 | 27 | (20.4, | 34.8) | 235 | 23.5 | (20.0, | 27.4) | |||

| Minoritygroup | |||||||||||

| White/English | 404 | 94.1 | (87.9, | 97.2) | 555 | 89.3 | (85.2, | 92.4) | 2.74 | 1 | 0.098 |

| Minority | 32 | 5.9 | (2.8, | 12.1) | 70 | 10.7 | (7.6, | 14.8) | |||

| Income | |||||||||||

| Not stated | 33 | 7.6 | (4.2, | 13.3) | 41 | 7.8 | (5.2, | 11.6) | 0.55 | 3 | 0.646 |

| Low | 56 | 20.7 | (12.7, | 31.8) | 144 | 20.7 | (16.8, | 25.2) | |||

| Moderate | 102 | 30.6 | (22.6, | 40.1) | 172 | 24.7 | (20.4, | 29.5) | |||

| High | 249 | 41.1 | (31.9, | 50.9) | 273 | 46.9 | (41.5, | 52.3) | |||

| Education | |||||||||||

| Low | 144 | 34.2 | (25.3, | 44.5) | 191 | 30.6 | (25.7, | 35.9) | 0.22 | 2 | 0.801 |

| Moderate | 196 | 42.6 | (33.1, | 52.6) | 267 | 45.6 | (40.3, | 51.1) | |||

| High | 92 | 23.2 | (15.8, | 32.6) | 169 | 23.8 | (19.4, | 28.8) | |||

| Timesincequit | |||||||||||

| In the last 3 months | 78 | 23.7 | (15.4, | 34.5) | 139 | 25.4 | (20.5, | 31.0) | 2.1 | 2 | 0.123 |

| 4–12 months ago | 185 | 44.5 | (35.1, | 54.2) | 237 | 34.1 | (29.2, | 39.4) | |||

| 1–2 years ago | 177 | 31.9 | (23.9, | 41.0) | 254 | 40.5 | (35.6, | 45.7) | |||

| Urges to quit | |||||||||||

| Very/extremely strong | 1 | 0.4 | (0.0, | 2.5) | 10 | 2.7 | (1.2, | 5.8) | 2.97 | 4 | 0.019 |

| Strong | 6 | 0.7 | (0.2, | 2.8) | 21 | 4.1 | (2.1, | 8.1) | |||

| Moderate | 15 | 5.9 | (2.8, | 12.1) | 65 | 9.4 | (7.0, | 12.7) | |||

| Slight | 46 | 20.8 | (12.6, | 32.3) | 148 | 22.6 | (18.4, | 27.4) | |||

| No urges | 371 | 72.3 | (61.3, | 81.1) | 385 | 61.2 | (55.7, | 66.3) | |||

Wald F denominator degrees of freedom = 1034

Difference in time to first cigarette reported retrospectively between vapers and non-vapers

Among vapers, 34.3% (95%CI:25.6,44.3, n=138) reported that they used to smoke within five minutes of waking compared to 15.9% (95%CI:12.2,20.6, n=84) of non-vapers (Wald F =11.26,p<0.001) (Table S2). This difference remained after adjusting for covariates (AOR 3.74(95%CI:1.99,7.03), chi-square=16.92,p<0.001) (Table 2). Additionally, among all former smokers, those who quit 4–12 months ago were less likely to report that they used to smoke within five minutes of waking compared to those who quit 1–2 years ago, and 40–54 year olds were more likely to report having smoked within five minutes of waking compared to those aged 55+ (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses: Weighted logistic regression models examining the association between dependence measures, confidence and vaping status controlling for all covariates

| First cig within 5 min (N= 1018) | Smoked > 10 c.p.d (n=1047) | Very addicted (N = 1009) | Any urges to smoke (N = 1050) | Extremely confident in quitting (N=1051) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | x2 | DF | p | OR | (95% CI) | x2 | DF | p | OR | (95% CI) | x2 | DF | p | OR | (95% CI) | x2 | DF | p | OR | (96% CI) | x2 | DF | P | |

| Sample source | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ITC cohort | 2.52 | (0.73, 8.68) | 2.7 | 2 | 0.26 | 0.47 | (0.15, 1.48) | 5.65 | 2 | 0.059 | 1.67 | (0.54, 5.21) | 0.84 | 2 | 0.657 | 8.51 | (2.81, 25.75) | 7.870 | 2 | <.001 | 0.31 | (0.11, 0.85) | 6.92 | 2 | 0.031 |

| Commercial | 1.3 | (0.55, 3.10) | 0.34 | (0.13, 0.88) | 1.43 | (0.61, 3.39) | 6.19 | (2.40, 15.96) | 0.32 | 0.14, 0.75) | |||||||||||||||

| AU CCV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Country | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CA | 0.56 | (0.26, 1.17) | 2.51 | 3 | 0.474 | 0.77 | (0.44, 1.35) | 0.9 | 3 | 0.826 | 0.75 | (0.40, 1.40) | 4.82 | 3 | 0.185 | 0.78 | (0.44, 1.40) | 3.320 | 3 | 0.019 | 1.09 | (0.61, 1.96) | 1.44 | 3 | 0.696 |

| US | 0.66 | (0.29, 1.54) | 0.86 | (0.46, 1.60) | 0.63 | (0.30, 1.32) | 0.51 | (0.26, 0.97) | 1.41 | (0.73, 2.73) | |||||||||||||||

| EN | 0.65 | (0.32, 1.33) | 0.8 | (0.45, 1.43) | 0.49 | (0.26, 0.95) | 0.43 | (0.23, 0.79) | 1.04 | (0.56, 1.92) | |||||||||||||||

| AU | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 0.84 | (0.50, 1.42) | 0.44 | 1 | 0.509 | 1.57 | (1.03, 2.39) | 4.33 | 1 | 0.037 | 0.82 | (0.52, 1.31) | 0.67 | 1 | 0.414 | 0.74 | (0.47, 1.16) | 1.760 | 1 | 0.185 | 1.28 | (0.85m 1.92) | 1.4 | 1 | 0.236 |

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Age group | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 1.48 | (0.44, 4.96) | 12.3 | 3 | 0.006 | 0.3 | (0.13, 0.72) | 26.89 | 3 | <0.001 | 0.18 | (0.06, 0.52) | 19.99 | 3 | <.001 | 0.62 | (0.26 1.50) | 3.140 | 3 | 0.025 | 0.98 | (0.45, 2.13) | 1.69 | 3 | 0.639 |

| 25–39 | 0.98 | (0.44, 2.20) | 0.27 | (0.16, 0.46) | 0.31 | (0.16, 0.59) | 0.41 | (0.23, 0.74) | 1.35 | (0.80, 2.28) | |||||||||||||||

| 40–54 | 2.46 | (1.32, 4.56) | 0.72 | (0.44, 1.17) | 0.54 | (0.32, 0.90) | 0.64 | (0.39, 1.04) | 1.24 | (0.78, 1.97) | |||||||||||||||

| 55+ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| white | 1.17 | (0.52, 2.63) | 0.14 | 1 | 0.704 | 2.45 | (1.23, 4.89) | 6.46 | 1 | 0.011 | 4.23 | (1.67, 10.68) | 9.33 | 1 | 0.002 | 2.56 | (1.03, 6.38) | 4.080 | 1 | 0.044 | 0.044 | (0,32, 1.39) | 1.17 | 1 | 0.279 |

| Non-white | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Income | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not stated | 1.44 | (0.45, 4.63) | 1.66 | 3 | 0.645 | 1.15 | (0.45, 2.98) | 6.23 | 3 | 0.101 | 0.54 | (0.21, 1.37) | 4.8 | 3 | 0.187 | 1.35 | (0.54, 3.35) | 0.260 | 3 | 0.855 | 1.05 | (0.41, 2.73) | 0.8 | 3 | 0.850 |

| Low | 1.48 | (0.71, 3.07) | 1.34 | (0.75, 2.38) | 0.96 | (0.47, 1.94) | 1.22 | (0.65, 2.28) | 0.8 | (0.46, 1.39) | |||||||||||||||

| Moderate | 1 | (0.53, 1.91) | 0.67 | (0.41, 1.09) | 0.61 | (0.36, 1.02) | 1.21 | (0.71, 2.07) | 0.99 | (0.60, 1.64) | |||||||||||||||

| High | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Low | 2.21 | (1.11, 4.41) | 5.13 | 2 | 0.077 | 1.62 | (0.92, 2.84) | 7.33 | 2 | 0.026 | 0.8 | (0.42, 1.54) | 0.65 | 2 | 0.724 | 0.97 | (0.52, 1.84) | 0.100 | 2 | 0.902 | 1.51 | (0.85, 2.67) | 14.32 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 1.54 | (0.81, 2.93) | 2.03 | (1.21, 3.39) | 0.99 | (0.57, 1.73) | 1.09 | (0.61, 1.95) | 2.66 | (1.58, 4.48) | |||||||||||||||

| High | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Time since quit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In last 3 mths | 0.57 | (0.28, 1.18) | 9.42 | 2 | 0.009 | 0.56 | (0.32, 0.98) | 6.77 | 2 | 0.034 | 2.43 | (1.32, 4.49) | 8.36 | 2 | 0.015 | 5.36 | (2.99, 9,68) | 15.950 | 2< | 0.001 | 0.33 | (0.18, 0.58) | 14.85 | 2 | <0.001 |

| 4–12 mths ago | 0.41 | (0.23, 0.73) | 0.57 | (0.36, 0.92) | 1.26 | (0.74, 2.15) | 1.85 | (1.10, 3.09) | 0.63 | (0.40, 1.00) | |||||||||||||||

| 1–2 years ago | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Vaping status | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vaper | 3.74 | (1.99, 7.03) | 16.92 | 1 | <.001 | 4.39 | (2.22, 8.68) | 18.18 | 1 | <0.001 | 2.89 | (1.58, 5.30) | 11.87 | 1 | <.001 | 0.86 | (0.44, 1.65) | 0.210 | 1 | 0.643 | 3.22 | (1.86, 5.59) | 17.36 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Non-vaper | 1 | a | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

Difference in usual daily cigarette consumption reported retrospectively between vapers and non-vapers

Among vapers, 74.4% (95%CI:64.5,82.5,n=368) reported that they used to smoke more than 10 cigarettes/day compared to 47.2% (95%CI:41.9,52.6,n=318) of non-vapers (Wald F=22.37 p<0.001) (Table S2). This difference remained after adjusting for covariates (AOR 4.39,95%CI:2.22, 8.68), chi-square=18.18, p<0.001) (Table 2). Additionally, among all former smokers, those who quit less than one year ago were less likely to report that they smoked more than 10 cigarettes/day compared to those who quit 1–2 years ago; similarly those aged less than 40 vs those aged 55+, those with high vs moderate education, males vs females and those of non-white ethnicity vs white ethnicity, were less likely to report smoking more than 10 cigarettes/day (Table 2).

Difference in perceived addiction to smoking, urges to smoke and confidence in remaining a non-smoker, between vapers and non-vapers at the time of the survey

Among vapers 41.3% (95%CI:31.4%,52.0%, n=174) perceived themselves to be still very addicted to smoking at the time of the survey compared with 26.2% (95%CI:21.6%,31.4%, n=157) of non-vapers (Wald F =5.95, p=0.015 (Table S2). This relationship remained after adjusting for covariates (AOR=2.89 (95%CI:1.58,5.30), chi-square=11.87, p<0.001) (Table 2). Additionally, among all former smokers, those who quit in the last three months were more likely to report feeling very addicted compared to those who quit 1–2 years ago, as were older (55+) compared to younger age groups, and white former smokers compared to non-white former smokers.

By contrast, 27.7% (95%CI:18.9%,38.7%, n=68) of vapers reported experiencing any urges to smoke in the last 24 hours, at the time of the survey, compared with 38.8% (95%CI:37.7%,44.3%, n=244) of non-vapers (Wald F=3.87, p=0.049) (Table S2). This relationship was no longer significant in the multivariable analysis (AOR 0.86 (95%CI:0.44,1.65), chi-square=0.21, p=0.643) (Table 2). Additionally, among all former smokers, time since quit was a significant predictor, with those quitting in the last 12 months being significantly more likely than those quitting 1–2 years ago to report experiencing any urges to smoke, as were white former smokers compared to non-white former smokers, and those aged 55+ years compared to 25–39 year olds. Similarly those in AU versus those in the US and EN, and those from other sources compared with the AU CCV, were significantly more likely to report experiencing any urges to quit in the last 24 hours.

Vapers were significantly more likely to report feeling extremely confident in their ability to stay quit (62.1% (95%CI:52.5%,70.9%), n=317) compared with non-vapers (36.6% (95%CI:1.6%,41.9%), n=240) (Wald F =17.43, p<0.001) (Table S2). This relationship remained significant after controlling for other measures (AOR 3.22(95%CI:1.86,5.59), chi-square=17.36, p<0.001) (Table 2). Additionally, among all former smokers, those who quit less than one year ago were significantly less likely to feel extremely confident than those quitting 1–2 years ago; and those of moderate education were more likely to feel extremely confident than those of high education; those in the Australian vaper sample were more likely to feel confident in staying quit than respondents from the other sample sources.

The sensitivity analysis excluding the AU CCV sample did not alter the results, although the sample with the Australian vapers removed was too small for the analysis of urges to smoke [Tables S3 and S4].

Discussion

When comparing retrospective reports of time to first cigarette and usual daily cigarette consumption between former smokers who vape daily and non-vapers, significantly more vapers reported that they used to smoke within five minutes and smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day, compared with non-vapers. Vapers were also significantly more likely to perceive that they were still very addicted to smoking (at the time of the survey) compared with non-vapers, although there was no difference in reporting any urges to smoke. Furthermore, vapers were more likely to report feeling extremely confident in their ability to remain a non-smoker than non-vapers. There were few country differences in these measures. As might be expected, the longer respondents were quit the less likely they were to report any urges to smoke in the last 24 hours, the less addicted they saw themselves as being and the more confident they were in staying quit. However, curiously, those quit for less than one year were less likely to have smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day, and those quit from 4–12 months, less likely to report previously having smoked within five minutes of waking, compared with those who had quit for 1–2 years.

Our finding of retrospective reports of higher dependence among former smokers who vape, compared with those not currently vaping, is novel, but consistent with studies that reported higher retrospective smoking dependence among vapers than dependence in continuing smokers(8). Similarly, in convenience samples of former smokers(17), vapers had a higher smoker identity (agreement with the statement ‘Smoking is a part of me’) than NRT users. However, we were surprised at the relatively high proportion of our sample who perceived still being very addicted to smoking across both vapers (41%) and non-vapers (26%), especially since around 80% of the sample reported quitting smoking more than four months ago. There is little literature on this, but just over 50% of smokers who had maintained abstinence for over four years reported some occasional craving for cigarettes(38), and dreaming about smoking was apparent one year after quitting in another study(39).

There are two possible explanations for these findings which cannot be distinguished given the cross-sectional nature of the study. First, in line with our finding of higher reported prior dependence on smoking among vapers than non-vapers, it could be that those former smokers who were daily nicotine vaping at the time of our survey had been a more highly dependent group of smokers. Secondly, that vaping was providing more potent cues for smoking than among the non-vapers, or vapers were exposed to more friends/family that smoked or vaped, and this maintained their desire for cigarettes. Indeed, qualitative research has found that some people were turned off by the similarity of smoking to vaping, as by replicating the hand-to-mouth action of a cigarette too closely, vaping was therefore not breaking the psychological habit of smoking(12). In our study, however, despite higher perceived current dependence on smoking among vapers, there was no difference in the likelihood of reporting any current urges to smoke, suggesting that rather than cueing smoking, vaping might be helping to ameliorate urges, which are known to predict relapse after one month of cessation((29). Additionally, vapers were significantly more likely to feel extremely confident in remaining quit than non-vapers, even after controlling for duration of abstinence, and this self-efficacy measure has been shown to be protective of relapse(29). In totality therefore, our findings favour the first explanation that in our sample the daily vapers had been a more highly dependent group than the non-vapers, which would support the suggestion that vaping might be offering a novel route out of smoking for this group of smokers, albeit maintaining their nicotine addiction. Our findings should be used to inform longitudinal studies to investigate these relationships prospectively.

One other implication of our findings is that if those who vape after quitting were more dependent before quitting, then we should not be comparing quit rates as a function of use of vaping in population studies, as this study provides evidence suggesting that vapers are distinctly different on factors known to influence cessation success.

The mechanisms behind any effect of NVP for supporting more addicted smokers require elucidation. Vaping may be playing a role in ways other than simply nicotine substitution, across the complex relapse trajectory(40). Whilst dependence has been shown to be a predictor of relapse back to smoking, recent studies have demonstrated that it is only predictive in the first few weeks of quitting(29) (41, 42) whereas other factors such as urges to smoke, self-efficacy and friends’ smoking have greater predictive value in later stages of quitting(29, 42). Our findings support other research suggesting that NVP help combat urges to prevent relapse to smoking(15), but also suggest that NVP may increase smokers’ confidence that they can remain quit. This is possibly because vaping is mimicking aspects of smoking, including positive aspects, in a way that NRT does not (12, 13). There is little research on self-efficacy and NRT use post quitting, although one study found no significant increase in self-efficacy with NRT use after the quit attempt(43). The most recent Cochrane review for relapse prevention(44) found some evidence for extended use of varenicline but not for NRT, although NRT appeared to be useful for those who had quit without support. A prior review (45) also found NRT use can be effective in preventing relapse following a period of abstinence. Given NVP use is increasing among long-term ex-smokers over time compared with NRT use, at least in England(46), relapse prevention studies comparing vaping and NRT are warranted. Furthermore, studies of NVP over long-term abstinence are required, building on the recent randomized controlled trial evidence in which more quitters continued to vape than continued to use NRT longer term(15).

This study has important limitations. The methodology for the 4CV1 data((31) relied on commercial databases only some of which were sourced from probability samples and we also included an Australian supplementary dedicated vaper sample from which the majority of the vapers in the current study were sourced. We tested whether sample source significantly affected the results and found it did not, although confidence in quitting was significantly greater among the Australian supplementary sample after controlling for other variables. In addition, we included only daily vapers who vape with nicotine, so our findings might not apply to occasional vapers or those who do not vape with nicotine. Because the data analysed in this paper are cross-sectional, with two measures being retrospective, we cannot separate cause and effect nor can we be confident of the accuracy of the retrospective reported measure since current vaping status might influence respondents’ recall of their prior dependence, and these findings were not as expected in relation to time since quit. Finally, sample sizes were insufficient to explore whether any former smokers had used NVP on their last quit attempt and compare this across the two groups. However, this is the first study to compare different groups of former smokers, using the same retrospective and current measures of smoking dependence, as well as confidence in remaining quit.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study, we observed that former smokers who vaped daily were more likely to perceive that they were still very addicted to smoking, compared with former smokers who were not vaping, reported confidence in remaining a non-smoker was higher for vapers and there was no difference in reporting any current urges to smoke. We cannot discern cause and effect so these findings should be seen as exploratory and longitudinal research is needed to explore these issues further.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interests

Conflict of interest declaration: KMC has been a consultant and received grant funding from the Pfizer, Inc. in the past five years. KMC has also been a paid expert witness in litigation against the cigarette industry. GTF has served as an expert witness on behalf of governments in litigation involving the tobacco industry. All other co-authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians. Nicotine without smoke. A report of the Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians; London, UK; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes Washington DC; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, Bauld L, Robson D. Evidence review of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products 2018. A report commissioned by Public Health England; London; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beard E, West R, Michie S, Brown J. Association between electronic cigarette use and changes in quit attempts, success of quit attempts, use of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, and use of stop smoking services in England: time series analysis of population trends British Medical Journal. 2016;354:i4645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caraballo RS, Shafer P, Patel D, Davis K, McAfee T. Quit methods used by US adult cigarette smokers, 2014–2016. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajek P, Jackson P, Belcher M. Long-term use of nicotine chewing gum. Occurrence, determinants, and effect on weight gain. JAMA. 1988;260:1593–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahab LS, Dobbie F, Hiscock R, McNeill A, Bauld L. Prevalence and impact of long-term use of nicotine replacement therapy in UK Stop-Smoking Services: findings from the ELONS study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2017;20:81–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farsalinos KE, Romagna G, Tsiapras D, Kyrzopoulos S, Voudris V. Characteristics, perceived side effects and benefits of electronic cigarette use: A worldwide survey of more than 19,000 consumers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014(11):4356–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etter J-F, Eissenberg T. Dependence levels in users of electronic cigarettes, nicotine gums and tobacco cigarettes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;147:68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma BH, Yong H, Borland R, McNeill A, Hitchman S. Factors associated with future intentions to use personal vaporisers among those with some experience of vaping. Drug Alcohol Review. 2017;37:216–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etter J-F. Electronic Cigarette: A longitudinal study of regular vapers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2018:912–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadsworth E, Neale J, McNeill A, Hitchman S. How and Why Do Smokers Start Using E-Cigarettes? Qualitative Study of Vapers in London, UK. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:pii:E661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Notley C, Ward E, Dawkins L, Holland R. The unique contribution of e-cigarettes for tobacco harm reduction in supporting smoking relapse prevention Harm Reduction Journal. 2018;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Notley C, Ward E, Dawkins L, Holland R, Jakes S. Vaping as an alternative to smoking. Drug Alcohol Review. 2019;38:68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajek P, Phillips-Walker A, Przulj D, Pesola F, Myers Smith K, Bisal N, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine replacement therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380:629–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, McRobbie H, Parag V, Williman J, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1629–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson VA, Goniewicz M, Beard E, Brown J, Sheals K, West R, et al. Comparison of the characteristics of long-term users of electronic cigarettes versus nicotine replacement therapy: A cross-sectional survey of English ex-smokers and current smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;153:300–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shahab LS, Goniewicz M, Blount B, Brown J, McNeill A, Alwis K, et al. Nicotine, carcinogen, and toxin exposure in long-term e-cigarette and nicotine replacement therapy users: a cross-sectional study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2017;166:390–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farsalinos KE, Spyrou A, Tsimopoulou K, Stefopoulos C, Romagna G, Voudris V. Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: comparison between first and new-generation devices. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawkins L, Turner J, Roberts A, Soar K. ‘Vaping’ profiles and preferences: an online survey of electronic cigarette users. Addiction. 2013;108:1115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farsalinos KE, Romagna G, Tsiapras D, Kyrzopoulos S, Voudris V. Evaluating nicotine levels selection and patterns of electronic cigarette use in a group of “Vapers” who had achieved complete substitution of smoking. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 2013;7:139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goniewicz MJ, Lingas E, Hajek P. Patterns of electronic cigarette use and user beliefs about their safety and benefits: An Internet survey. Drug Alcohol Review. 2013;32(2):133–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foulds J, Veldheer S, Yingst J, Hrabovsky S, Wilson S, Nichols T, et al. Development of a questionnaire for assessing dependence on electronic cigarettes among a large sample of ex-smoking e-cigarette users. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17(2):186–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rostron BL, Schroeder J, Ambrose B. Dependence symptoms and cessation intentions among US adult daily cigarette, cigar, and e-cigarette users, 2012–2013. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu G, Wasserman E, Kong L, Foulds J. A comparison of nicotine dependence among exclusive E-cigarette and cigarette uers in the PATH study. Preventive Medicine. 2017;104:86–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (TTURC) Tobacco Dependence,Baker T, Piper M, et al. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:S555–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Etter J-F, Le Houezec J, Perneger T. A self-administered questionnaire to measure dependence on cigarettes: the cigarette dependence scale. Psychopharmacology. 2003;28:549–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit E, Borland R, West R. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: a systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106:2110–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herd N, Borland R, Hyland A. Predictors of smoking relapse by duration of abstinence: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2009;104:2088–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blevins CE, Farris S, Brown R, Strong D, Abrantes A. The role of self-efficacy, adaptive coping, and smoking urges in long-term cessation outcomes. Addict Disord Their Treat. 2016;15:183–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson ME, Fong G, Boudreau C, Driezen P, Li G, Gravely S, et al. Methods of the ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey, wave 1 (2016) 2018;December 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fagerstrom K Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14:75–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski L, Frecker R, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: Using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84:791–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zawertailo L, Voic S, Selby P. The Cigarette Dependence Scale and Heaviness of Smoking Index as predictors of smoking cessation after 10 weeks of nicotine replacement therapy and at 6-month follow-up. Addictive Behaviours. 2018;78:223–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fidler JA, Shahab L, West R. Strength of urges to smoke as a measure of severity of cigarette dependence: comparison with the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and its components. Addiction. 2010;106:631–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gwaltney CJ, Metrik J, Kahler C, Shiffman S. Self-efficacy and smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Psychol Addict Behav 2009;23:56–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wetter DW, Cofta-Gunn L, Fouladi R, Cinciripini P, Sui D, Gritz E. Late relapse/sustatined abstinence among former smokers: a longitudinal study. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:1156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daughton DM, Fortmann S, Glover E, Hatsukami D, Healey S, Lichtenstein E, et al. The smoking cessation efficacy of varying doses of nicotine patch delivery systems 4 to 5 years post-quit day. Preventive Medicine. 1999;28:113–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hajek P, Belcher M. Dream of absent-minded transgression: An empirical study of a cognitive withdrawal symptom. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991:487–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piasecki TM, Fiore M, McCarthy D, Baker T. Have we lost our way? The need for dynamic formulations of smoking relapse proneness. Addiction. 2002;97:1093–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou X, Nonnemaker J, Sherrill B, Gilsenan A, Coste F, West R. Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: Factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addictive Behaviours. 2009;34:365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yong HH, Borland R, Balmford J, Hyland A, O’Connor R, Thompson M, et al. Heaviness of smoking predicts smoking relapse only in the first weeks of a quit attempt: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four-Country Survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16:423–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piper ME, Cook J, Schlam T, Smith S, Bolt D, Collins L, et al. Towards precision smoking cessation treatment II: Proximal effects of smoking cessation intervention components on putative mechanisms of action. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2018;171:50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Livingstone-Banks J, Norris E, Hartmann-Boyce J, West R, Jarvis M, Hajek P. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019(2):Art.No.:CD003999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agboola S, McNeill A, Coleman T, Leonardi-Bee J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of smoking relapse prevention interventions for abstinent smokers Addiction. 2010;105:1362–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.West R, Brown J. Smoking in England: Smoking toolkit study 2019. [Available from: www.smokinginengland.info.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.