Abstract

Rationale

Exercise pulmonary hypertension (PH) may represent an early, but clinically relevant phase in the spectrum of pulmonary vascular disease. Limited data exist regarding the prevalence of exercise PH by right heart catheterization (RHC) in scleroderma spectrum disorders (SSc-spectrum).

Objectives

To describe the hemodynamic response to exercise in a homogeneous population of SSc-spectrum at risk for developing pulmonary vascular disease.

Methods

Patients with normal resting hemodynamics underwent supine lower extremity exercise testing. A classification and regression tree (CART) analysis was assessed for combinations of variables collected during resting right catheterization that best predicted abnormal exercise physiology, applicable to each individual subject.

Results

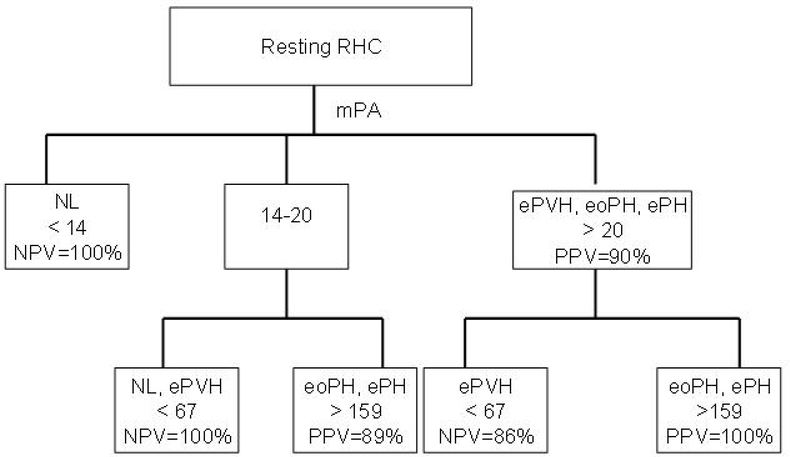

57 patients who had normal resting hemodynamics underwent subsequent exercise RHC. Four distinct hemodynamic groups were identified during exercise: normal (NL), pulmonary venous hypertension (ePVH), out of proportion PH (eoPH), and exercise PH (ePH). Both eoPH and ePVH had higher PCW vs. ePH (p<0.05). NL and ePH had exercise PCW ≤ 18mmHg which was lower compared to ePVH and eoPH (p<0.01). During submaximal exercise, the transpulmonary gradient and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) were elevated in ePH and eoPH compared to NL and ePVH (p<0.05). CART analysis suggested resting mPA ≥ 14 and PVR ≥ 160 to be associated with eoPH and ePH (PPV 89%−100%).

Conclusions

The exercise hemodynamic response in at-risk patients with SSc-spectrum without resting PH was found to be variable. Four distinct hemodynamic groups were identified during exercise: NL, ePVH, eoPH, and ePH. These groups may have potentially different prognoses and treatment options.

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a connective tissue disease (CTD) of unknown etiology characterized by microvascular injury, immunological activation, skin fibrosis, and visceral involvement 1, 2. Importantly, pulmonary complications including pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and interstitial lung disease (ILD) are the leading causes of SSc related death 3. PAH is a progressive disease leading to increased pulmonary vascular resistance and eventual right heart failure and death 4.

The prevalence of resting CTD-PAH is approximately 2.3–10 cases per million 5, typically mostly SSc patients (5–50%) 6–12, mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) (21–29%) 13, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (5–43%) 14–16. Based on RHC, the prevalence of resting PAH in SSc is likely 7.9% to 20%7, 17. However, histopathologic evidence of pulmonary arteriopathy has been documented in up to 72% of limited scleroderma patients, suggesting discordance between clinical findings and pathologic diagnosis 18.

SSc-PAH tends to have a poorer prognosis compared to other WHO Group I diagnoses. Recently, isolated SSc-PAH survival, while receiving pulmonary vasodilator therapy, was reported at 78% (1-year), 68% (2-year), and 47% (3-year) 7, 19, 20. Importantly, Tolle and coworkers have suggested exercise PH may represent an intermediate phenotype “between” normal and resting PH 21. In addition, Condliffe and coworkers found 19% of SSc-PAH patients with exercise PH developed resting PAH after approximately 2.3 years 19. However, others have argued that a certain degree of exercise PH may be explained by increasing age, persistent hypoxia, and/or systemic hypertension 22, 23. Nonetheless, an exercise evaluation of SSc-PAH patients may allow for earlier diagnosis, initiation of therapy, and perhaps, a more favorable outcome 24. Currently, the presumed progression of exercise SSc-PAH requires further study.

We retrospectively assessed clinical and hemodynamic data collected on consecutive SSc-spectrum patients referred for RHC at a University hospital. Our objectives were to delineate patterns of these patients undergoing exercise RHC.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective, descriptive analysis where 80 consecutive patients with SSc-spectrum underwent exercise RHC at a single University Hospital. This data collection was approved by the local institutional review board. Based on prior published literature, patients underwent RHC if they had dyspnea and at least one of the following: resting Doppler echocardiogram (DE)-estimated right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) ≥ 30 mmHg 25, 15% decline in DLCO (% predicted) over the preceding 2 years, DLCO (% predicted) ≤ 60%, or FVC/DLCO (% predicted) ratio > 1.4 6, 10. Importantly, a DE-derived RVSP threshold of 30 mmHg was chosen to capture “early” SSc-PH given a reported positive predictive value of 73% in this population 25.

On DE, patients were excluded with evidence of significant resting systolic (EF < 50%) and/or diastolic (> mild) left heart dysfunction. We identified patients with the SSc-spectrum, either limited/diffuse cutaneous SSc or overlap syndrome, based on the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification 26.. Disease duration was defined as the first non-Raynaud’s sign or symptom attributable to SSc. Furthermore, we also explored the impact of older age (> 50 years) 22 and significant interstitial lung disease (ILD) (% predicted FVC < 60%) 19 on exercise RHC hemodynamics.

Definition of Pulmonary Hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is defined as a resting mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPA) ≥ 25mmHg at RHC; PAH is defined as PH in addition to PCW ≤ 15mmHg 26. A hemodynamic evaluation was performed during maximal exercise for patients without resting PH. Four distinct groups were identified based on exercise hemodynamics: normal (NL), pulmonary venous hypertension (ePVH), out of proportion PH (eoPH), and exercise PH (ePH). We defined normal (NL) as mPA < 30mmHg; exercise PH (ePH) as mPA > 30mmHg, PCW ≤ 18mmHg 27, and transpulmonary gradient (TPG) ≥ 15mmHg 28, 29, 30 (TPG = mPA – PCW)31; exercise pulmonary venous hypertension (ePVH) as mPA > 30mmHg, PCW > 18mmHg, and TPG < 15mmHg; exercise out of proportion PH (eoPH) as mPA > 30mmHg, PCW > 18mmHg, and TPG ≥ 15mmHg.

TPG is the pressure gradient across the pulmonary vascular bed (mPA-PCW) and increases linearly with cardiac output in healthy volunteers. Importantly, TPG accounts for the normal increase in left sided filling pressures during exercise and allows differentiation between precapillary and postcapillary (pulmonary venous) pulmonary vascular disease 32. As such, we hypothesized that TPG will be better able to distinguish pulmonary vascular disease from pulmonary venous disease.

Resting and Exercise Right Heart Catheterization Protocol

A PA catheter (Edwards Scientific, Irvine, California) was floated by internal jugular approach under ultrasound guidance. End-expiratory values were transduced for right atrial (RA), pulmonary artery systolic (sPA), PA diastolic (dPA), and pulmonary capillary wedge (PCW) pressures. Thermodilution cardiac output (CO) was analyzed after averaging the sum of triplicate measurements at rest, and single measurements during each exercise interval.

All exercise RHC were conducted on six liters nasal cannula oxygen to prevent significant hypoxemia. A supine, lower extremity cycle ergometer (Medical Positioning Inc, Kansas City, Missouri) test was performed using a 3 minute interval ramp protocol with increments of 10–15 watts (W), starting at 25 or 30W until exhaustion or 75% maximum predicted heart rate. In normal subjects, there is a linear relation between heart rate and cardiac output vs. oxygen consumption (VO2) during exercise. Since we did not directly measure VO2, heart rate response was used as a surrogate for maximizing cardiac output during exercise21, 31. End-expiratory mPA was measured continuously and end-expiratory PCW was obtained during the final minute of exercise.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics of baseline characteristics and resting hemodynamic variables were computed for each group and are reported in Table 1 (mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to detect between-group differences for continuous variables, with the log-transformation being employed for data not normally distributed. In the case of categorical variables, the Chi-square and Fisher’s Exact tests were used. Where significant between-group differences were detected by ANOVA, pairwise comparisons were made for each possible pair of groups using the Tukey-Kramer method adjusting for multiple comparisons. These analyses were repeated for the hemodynamic values during peak exercise.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Total | NL | ePVH | eoPH | ePH | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N, % | 57 | 15 (26%) | 12 (21%) | 9 (16%) | 21 (37%) | |

| Female N, % | 45 (78.95) | 10 (66.7) | 11 (91.7) | 8 (88.9) | 16 (76.2) | 0.452 |

| Type of SSc | 0.212 | |||||

| Diffuse (%) | 25 (45.5) | 9 (64.3) | 7 (58.3) | 3 (37.5) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Limited (%) | 22 (40.0) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (33.3) | 4 (50.0) | 9 (42.9) | |

| MCTD / Overlap | 8 (14.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (12.5) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Disease duration (years) | 5.6 (5.8) | 3.2 (3.5) | 5.0 (4.4) | 7.9 (7.2) | 6.8 (7.0) | 0.35 |

| Age | 50.9 (12.8) | 42 (10.2)† | 53.3 (11.5) | 60.1 (13.2) | 52.1 (11.9) | 0.007 |

| Ethnicity (N) | 0.024 | |||||

| Caucasian | 8 | 12 | 6 | 8 | ||

| Hispanic | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||

| African American | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

Values represent mean (standard deviation)

Accounted for multiple comparisons using Tukey-Kramer method

(*1 vs 2; § 2 vs 3; † 1 vs 3;∥ 2 vs 4; ‡ 1 vs 4; ** 3 vs 4), p<0.05

To systematically determine the presence or absence of exercise abnormality in a given patient, a classification and regression tree (CART) analysis was performed, using the statistical software package R, (v2.9.1). All analyses were done using STATA 10.1 (College Station, TX) and a p < 0.05 was indicative of statistical significance.

These decision tree models are technically known as binary recursive partitioning. A parent node is always split into two child nodes (binary); the process is repeated for each child node (recursive) and each split results in portioning into mutually exclusive subsets. The model aims to recursively partition input variables in order to maximize the purity in a terminal node. The decision to make a partitioning split is done after searching each possible threshold for each variable included in order to find the split that leads to the greatest improvement in the purity score of the resultant node; cut-off points are sought for continuous variables (rather than deciding on an arbitrary dichotomous point). Each node is split on just one variable. All analyses were done using STATA 10.1 (College Station, TX) and a p < 0.05 was indicative of statistical significance.

Results

Patient Demographics

Eighty consecutive patients with SSc-spectrum underwent resting and exercise RHC between 7/01/2007 until 7/15/2009. Of those, 23 had evidence of resting PH and were excluded from further analysis. The remaining 57 patients had evidence of normal resting pulmonary hemodynamics with either New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class I or II, and subsequently underwent exercise testing. The clinical and hemodynamic characteristics of these 57 patients at baseline are outlined in Table 1 and Table 2. The majority of the patients were female (79%) and Caucasian (59%), and the average (SD) age was 51.0 (12.8) years. Twenty-five (45.5%) had diffuse SSc, 22 (40%) had limited SSc, and 10 (14.6%) had overlap syndrome. For the cohort, the mean FVC (% predicted) was 77%, mean DLCO (% predicted) was 59%, and the mean FVC/DLCO ratio (% predicted) was 1.4; 9 (16%) had FVC (% predicted) < 60%.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics

| Total | NL | ePVH | eoPH | ePH | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N, % | 57 | 15 (26%) | 12 (21%) | 9 (16%) | 21 (37%) | |

| FVC, % | 76.6 (21.2) | 78.6 (19.8) | 83.3 (17) | 65.6 (26.9) | 76.1 (21.3) | 0.4798 |

| FVC category | 0.373 | |||||

| <60, N (%) | 9 (16.1) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (8.3) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (19.1) | |

| ≥60, N (%) | 47 (83.9) | 13 (92.9) | 11 (91.7) | 6 (66.7) | 17 (80.9) | |

| DLCO, % | 59.4 (20.4) | 63 (16.4) | 72.2 (20)§ | 44 (15.7) | 56.4 (20.7) | 0.018 |

| FVC/DLCO | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.6 (1.1) | 0.4084 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 48.1 (46.7) | 33.2 (36.4) | 50.9 (41.3) | 65 (59.3) | 50.3 (51.2) | 0.09 |

| 6-MW (N=39) | 387.7 (101.5) | 405.4 (111.2) | 427.6 (59.4) | 270.4 (94.8) | 392.7 (98.3) | 0.0796 |

Definitions of abbreviations: FVC= forced vital capacity; DLCO= diffusion capacity; BNP= brain natriuretic peptide

Values represent mean (standard deviation)

Accounted for multiple comparisons using Tukey-Kramer method

(*1 vs 2; § 2 vs 3; † 1 vs 3;∥ 2 vs 4; ‡ 1 vs 4; ** 3 vs 4), p<0.05

Resting DE data was available for all patients. The estimated tricuspid regurgitant (TR) jet was detectable for 36 (63%) patients with an average estimated RVSP (SD) of 36 mmHg (11.3). Five of the 57 patients had evidence of mild diastolic dysfunction on DE; however, none had elevated PCW (> 18mmHg) at rest and only one patient developed elevated PCW during exercise.

Eight-seven percent of the cohort had a positive antinucleolar antibody (ANA). Of those, 20% had a positive centromere antibody; however, no correlation was present in relation to hemodynamic parameters at rest or exercise.

Resting Hemodynamics

Four distinct hemodynamic groups were identified on exercise: normal (NL) (n=15), pulmonary venous hypertension (ePVH) (n=12), eoPH(n=9), and exercise PH (ePH) (n=21) (Table 3). In addition, eoPH and ePH groups had higher PVR and TPG compared to NL and ePVH groups. NL were younger in age (42 years), had lower mPA (14.4) compared to eoPH, and lower mean PCW (8 mmHg) compared to other groups (Table 3). A male predominance, diffuse SSc and shortest disease duration was more characteristic in NL compared to the other 3 groups. Finally, eoPH had the lowest DLCO (44% predicted) and highest resting mPA (20.7 mmHg), compared to the other 3 groups.

Table 3.

Resting Hemodynamics

| Total | NL | ePVH | eoPH | ePH | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA mean | 6.3 (3.1) | 4.9 (3.3)* | 8.1 (2.6) | 6 (2.6) | 6.4 (3) | 0.0347 |

| PAsys mmHg | 28.9 (6.1) | 24.3 (6.7) †,‡ | 29.4 (3.7) | 31.6 (6) | 30.6 (5.3) | 0.0173 |

| PAdia mmHg | 12.3 (4.1) | 8.3 (2.6)*,†,‡ | 13.7 (4.1) | 15.8 (2.6) | 12.8 (3.4) | 0.0001 |

| mPA mmHg | 18.2 (4.1) | 14.4 (3.9)*,†,‡ | 19.2 (3.3) | 20.7 (3.4) | 19.3 (3.1) | 0.0007 |

| PCW mmHg | 10.7 (4.1) | 8 (3.6)*,† | 14.6 (2.7)∥ | 11.9 (4.3) | 9.9 (3.2) | 0.0003 |

| CO I/min | 5.2 (1.4) | 5.7 (1.6) | 5.8 (1.6) | 4.7 (1.6) | 4.7 (0.8) | 0.0491 |

| CI I/min/m2 | 3 (0.8) | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.3 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.6) | 0.0517 |

| PVR dyn*sec*cm−5 | 127 (73.5) | 95.9 (50.4)*,‡ | 67.7 (40.4) §, ∥ | 168.3 (86.7) | 165.5 (65.6) | 0.0002 |

| TPG mmHg | 7.5 (3.5) | 6.4 (3.1) ‡ | 4.6 (2.3) §, ∥ | 8.8 (3.4) | 9.4 (3.1) | 0.0005 |

| HR | 75.6 (13.9) | 72.7 (10.8) | 71.8 (13.8) | 79.2 (17.1) | 78.8 (15.3) | 0.5892 |

Definitions of abbreviations: RA = right atrial pressure; PAsys = pulmonary artery systolic

PAdia = pulmonary artery diastolic; mPA = mean pulmonary artery; PCW = pulmonary capillary wedge; CO = cardiac output; CI = cardiac index; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; TPG = transpulmonary gradient; HR = heart rate

Values represent mean (standard deviation)

Accounted for multiple comparisons using Tukey-Kramer method

(*1 vs 2; § 2 vs 3; † 1 vs 3;∥ 2 vs 4; ‡ 1 vs 4; ** 3 vs 4), p<0.05

There were no other significant differences between groups in resting brain natriuretic peptide [BNP] levels or DE parameters.

Exercise Hemodynamics

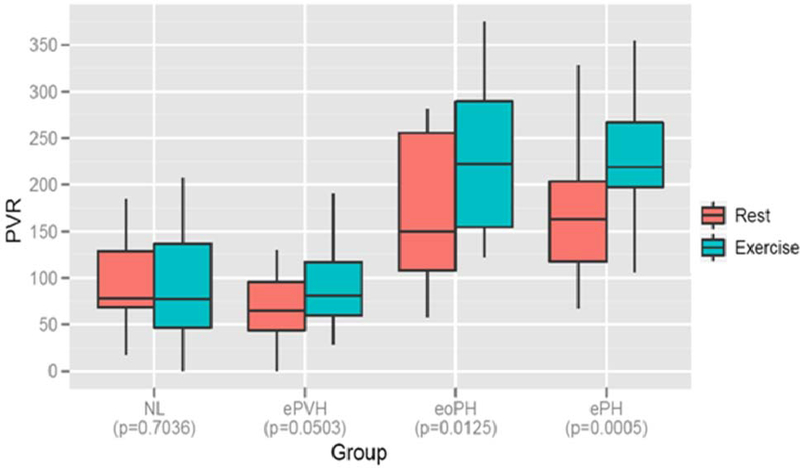

The majority of patients in all groups demonstrated acceptable effort, defined by peak heart rate ≥ 75% of predicted maximum; the mean (SD) peak heart rate was 128.4 (18.4) beats/min. The ePVH, eoPH, and ePH groups had higher mPA compared to NL (p< 0.05; Table 4), while ePVH (25.2 mmHg) and eoPH (22.8 mmHg) had higher PCW compared to NL (12.7 mmHg) and ePH groups (14.6 mmHg) (p< 0.05). Conversely, PVR and TPG were higher in eoPH and ePH compared to NL and ePVH (p< 0.05); there were no differences in PVR and TPG between ePH and eoPH. In addition, CO (L/min) was significantly higher in NL versus ePH, but only trended higher in ePVH compared to ePH. PVR significantly increased between rest and submaximal exercise only in patients with eoPH and ePH (p< 0.01) (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Exercise Hemodynamics

| Total | NL | ePVH | eoPH | ePH | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAsys mmHg | 52.9 (12.27) | 40.1 (8.3)*,†,‡ | 53.3 (8.9) | 61.9 (8.4) | 58.1 (10.6) | <.0001 |

| PAdia mmHg | 24.0 (7.0) | 15.9 (3.9)*,†,‡ | 25.8 (3.9) | 29.1 (7.2) | 26.57 (5.2) | <.0001 |

| mPA mmHg | 34.53 (7.9) | 24.2 (3.4)*,†,‡,§ | 35.9 (3.9) | 41.8 (4.8) | 37.9 (5.7) | <.0001 |

| PCW mmHg | 17.7 (6.7) | 12.7 (6.2)*,† | 25.3 (4.0)∥ | 22.8 (3.0)** | 14.6 (3.6) | <.0001 |

| CO I/min | 9.4 (3.1) | 11.6 (3.0)†,‡ | 10.3 (4.0)§ | 7.3 (1.89) | 8.2 (1.8) | 0.0007 |

| CI I/min/m2 | 5.4 (1.6) | 6.6 (1.4)†,‡ | 5.8 (1.8) | 4.4 (1.0) | 4.7 (1.1) | 0.0006 |

| PVR dyn*sec*cm−5 | 165.1 (94.0) | 91.1 (61.6)†,‡ | 90.2 (49.8) §, ∥ | 223.6 (91) | 232.1 (61.0) | <.0001 |

| TPG mmHg | 16.96 (7.84) | 11.5 (6.3)†,‡ | 10.6 (4.7)§, ∥ | 19.0 (5.3) | 23.3 (5.4) | <.0001 |

| HR | 128.4 (18.4) | 133.0 (20.6) | 124.1 (11.0) | 120.1 (12.8) | 129.5 (20.8) | 0.3634 |

Definitions of abbreviations: RA = right atrial pressure; PAsys = pulmonary artery systolic

PAdia = pulmonary artery diastolic; mPA = mean pulmonary artery; PCW = pulmonary capillary wedge; CO = cardiac output; CI = cardiac index; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; TPG = transpulmonary gradient; HR = heart rate

Values represent mean (standard deviation)

Accounted for multiple comparisons using Tukey-Kramer method

(*1 vs 2; § 2 vs 3; † 1 vs 3;∥ 2 vs 4; ‡ 1 vs 4; ** 3 vs 4), p<0.05

Figure 1:

Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) at rest and during submaximal exercise, by 4 groups. Data are presented as box plots, where the boxes represent the 25th to 75th percentiles, the lines within the boxes represent the median. p-value < 0.05

Hemodynamics in patients with FVC ≥ 60% vs. < 60% (% predicted)

Of the 9 patients with FVC < 60% predicted, 3 belonged to eoPH, 4 belonged to ePH, and 1 each belonged to NL and ePVH groups. These 9 patients had significantly higher baseline mPA (mmHg) [SD] (22.1 [2.1]) compared those with FVC ≥ 60% (% predicted) (17.6 [3.7]); (p< 0.001). Otherwise, there were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between these groups (data not shown). During exercise, patients with FVC < 60% predicted had higher mPAP (mmHg) [SD] (40.6 [7.4] vs. 33.5 [7.5]; p= 0.02) and PVR (dyn*sec*cm−5) [SD] (238.3 [93.5] versus 150.4 [89.2]; p= 0.02) compared to patients with FVC ≥ 60% (% predicted), respectively. When patients with FVC < 60% were excluded from the analysis, the four distinct clinical entities remained discernable (data not shown).

Hemodynamics in patients with age ≤ 50 years versus > 50 years

Patients in the NL group were younger compared to other 3 groups (p< 0.05, Table 1). We analyzed all patients who achieved mPA > 30 mm Hg during exercise (ePVH, eoPH and ePH). 15 (36%) patients were ≤ 50 years while 27 (64%) were > 50 years. There were no differences between age ≤ 50 years and > 50 years groups in the mean exercise mPA (mmHg) (38.0 vs. 38.3), PVR (dyn*sec*cm−5) (168.0 vs. 201.8), PCW (mmHg) (19.0 vs. 19.7), respectively. Similarly, both groups (age ≤ 50 years and > 50 years) achieved at least 75% of their predicted maximum heart rate (134.8 vs. 120.8 beats/minute).

Decision Tree

Figure 2 demonstrates the decision tree that is applicable to an individual patient with available resting RHC hemodynamics. In this analysis, baseline mPA is the parent or primary mode. A baseline mPA < 14 mmHg excludes ePH and eoPH (NPV 100%), and mPA > 20 mmHg had a PPV of 90% for confirming ePH and eoPH. Specifically for ePH and eoPH, PVR < 67 dyn*sec*cm−5 had a NPV of 86%, while PVR ≥ 160 dyn*sec*cm−5 had a PPV of 100%. Similarly, for patients with mPA 14–20 mmHg (inclusive), PVR < 67 dyn*sec*cm−5 had a NPV of 100%, and PVR ≥ 160 dyn*sec*cm−5 had a PPV of 89% for predicting ePH and eoPH.

Figure 2:

Decision tree is applicable to an individual patient with available resting RHC hemodynamics. The baseline mPA is the primary mode. Definitions of abbreviations: RHC = right heart catheterization; mPA = mean pulmonary artery pressure (mmHg); NL = normal; ePVH = exercise pulmonary venous hypertension; eoPH: exercise out of proportion pulmonary hypertension; ePH = exercise pulmonary hypertension; mPA = mean pulmonary artery; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance (dyn*s*cm−5); NPV= negative predictive value; PPV= positive predictive value

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate a variable exercise response in a “real life” cohort of SSc-spectrum patients with normal resting hemodynamics. There are four distinct groups characterized by the hemodynamic response to exercise: normal (NL), pulmonary venous hypertension (ePVH), out of proportion PH (eoPH), and exercise PH (ePH). The mPA and PVR are hemodynamic variables at rest that best distinguished ePH and eoPH from ePVH and NL. In addition, we provide a preliminary algorithm based on resting hemodynamics that may help researchers specifically predict eoPH and ePH for an individual SSc-spectrum patient.

Abnormal exercise physiology has been recognized in SSc, idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (iPAH), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 33, 21, 27, 34–39. Studies have described exercise PH in 46–59% of SSc-spectrum patients, characterized by DE sPA > 40 mmHg during exercise 23, 40, 41. Collectively, these studies suggest an abnormal phenotype in “at-risk” populations after assessing the response of the pulmonary vasculature to exercise.

A paucity of data exists regarding longitudinal follow up in patients with exercise PH. The UK group prospectively reported survival in 42 SSc patients with exercise PH of whom 8 (19%) progressed to resting PAH within a mean time of 838 + 477 days, and 4 (9.5%) died secondary to complications of pulmonary vascular disease within 3 years of diagnosis 19. PH in SSc may be an abnormal hemodynamic response and part of a continuum from normal to resting PH. We postulate ePH and eoPH may be at risk for developing progressive pulmonary vascular disease given the otherwise indistinguishable response to exercise, although with likely different frequencies and response to existing therapies.

Few studies exist using RHC to address whether an mPA > 30 mmHg during exercise represents an aberrant pulmonary vascular system in “at-risk” populations 19, 21, 27, 33, 37, 38, 42. Recently, Tolle and coworkers evaluated a large cohort of non-SSc, symptomatic patients, who underwent simultaneous cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) and RHC 21. At maximal exercise, mPA and PVR were highest in patients with resting PAH, lowest in normals, and intermediate in exercise PH 21. Exercise PH was defined as mPA > 30 mmHg, PCW < 20 mmHg, and a PVR ≥ 80 dyn*sec*cm−5 21. Importantly, after repeat analysis of our ePH group using Tolle’s definition, there was no reclassification of patients. In our study, both resting mPA > 20 mmHg and PVR ≥ 160 dyn*sec*cm−5 predicted the development of either eoPH or ePH. In contrast, Tolle’s study did not find an association between baseline hemodynamic parameters (including mPA 21–24 mmHg) and the development of exercise PH. This difference, in part, may be due to our study of a more homogenous, “at risk” population.

More recently, Kovacs and coworkers described the association of resting and exercise mPA to exercise capacity (6MW and peak VO2) in a well characterized SSc cohort 37. Patients with baseline FVC ≤ 60% and PCW > 15 mmHg were excluded, representing an important difference from our study. A median mPA > 17 mmHg at rest, and mPA > 23 mmHg during slight exercise was associated with both a significant decrease in 6MW and VO2max 37. The PVR from baseline to slight exercise was relatively unchanged, however, similar to our experience, suggested a PVR ≥ 160 dyn*sec*cm−5 at rest was potentially abnormal.

In our study, NL were significantly younger than eoPH, and trended to be younger than ePVH and ePH; however, whether abnormal exercise PH is an age related phenomenon specifically in SSc remains unclear. A recent systematic analysis suggested that during submaximal exercise, mPA exceeds 30mmHg in 47% of all cases in normal, healthy adults > 50 years age 22. However, measurements of PVR were not comprehensively reported. In our study, for individuals with mPA > 30 mmHg during exercise (n=42), mPA, PVR and PCW were independent of age. Moreover, after accounting for exercise PCW and CO, the PVR in both NL and ePVH were not significantly different between rest and exercise. In contrast, the PVR, significantly increased from rest to exercise in ePH and eoPH, compared to ePVH and NL, suggesting a blunted cardiac output response and vascular stiffness in ePH and eoPH. Importantly, another study showed both exercise capacity (6MW) and effective PVR during exercise were significantly improved after 8 weeks of epoprostenol in an iPAH cohort, even prior to appreciable changes in resting hemodynamics, further supporting the strength of this variable 43, 44.

Similar to a recent study 27, we explored patients with FVC < 60% related to significant ILD. This subgroup had significantly higher resting and exercise mPA versus the group with FVC ≥ 60%. Importantly, re-analysis after exclusion of these ILD patients (n=9) did not change the hemodynamic response to exercise in each of the 4 categories. Interestingly, IPF is a particularly well studied ILD with a similar spectrum of pulmonary complications to SSc and in fact, PAH complicates IPF in approximately 40% of patients at rest 39, 45, 46, and 80% during exercise 39. We hypothesize that a similar pathophysiology to IPF exists within the SSc-spectrum of disease, especially provided the high prevalence of ILD in the latter; as such, earlier diagnosis and potential intervention may modify the natural history of this disease.

A common goal of clinical research studies is to develop reliable clinical decision rule that can be used to classify patients into clinically-important categories. Our central hypothesis is that patients with normal exercise physiology and ePVH have a different pathophysiology compared to ePH and eoPH. We also postulate that exercise PH in SSc is an abnormal hemodynamic response and part of a continuum from normal to resting PH. Since exercise RHC testing is not standardized, we developed preliminary decision rule using the resting hemodynamics that can be utilized by researchers to differentiate NL, ePVH and ePH and eoPH We utilized mPAP and PVR to differentiate these groups. Our decision model shows that a resting mPAP < 14 mmHg has a 100% chance of ruling out exercise abnormal group (ePVH, e PH, and eoPH) whereas resting mPAP > 20 mmHg has a 90% chance of predicting mPA > 30mmHg during exercise. Our decision rule supports the recent Dana Point classification that defined resting mPA between 21–24 mmHg as borderline PAH, and a population “at risk”. In addition, a PVR > 160 dyn*sec*cm-5 predicted eoPH and ePH. Since ePH and eoPH are otherwise hemodynamically indistinguishable during exercise, they may be at risk for developing progressive pulmonary vascular disease. Importantly, this algorithm consistently separates ePVH, a condition with potentially a different therapeutic paradigm and natural history.

The pathologic mechanism of exercise PH has not been well elucidated. Alveolar hypoxia can cause pulmonary vasoconstriction and is believed to play an important role in the increase of mPA during exercise 47. Others have shown increased levels of catecholamines, vasopressin, and endothelin-1 levels during exercise 47–49. With regard to SSc, the vascular abnormality is dominated by the presence of both arteriolar and venular involvement, a pattern distinct from idiopathic PAH (iPAH) 50. These distinctive abnormalities may account for the different response to exercise as well as to therapy seen in SSc-PAH compared to iPAH.

Systematic longitudinal follow up on all of our patients will be important in determining the clinical significance of these 4 groups and the potential risk factors for progression to resting PAH. To date, one patient each with baseline FVC ≤ 60% and FVC > 60% have died of acute respiratory failure. Two additional patients who had ePH progressed to resting PAH in less than 1 year.

Our study has several strengths. First, we comprehensively assessed exercise hemodynamics in a “real-life” cohort of consecutive patients with SSc spectrum diseases and included ILD, a frequent finding in this population. To our knowledge, this report marks the largest experience of invasive exercise assessment in a SSc spectrum population. Secondly, we developed a preliminary decision tree based on resting RHC hemodynamics that may predict eoPH or ePH.

Our study has some limitations, apart from being a single center experience. First, we did not assess exercise DE and CPET in our cohort, as recently done by other investigators. Second, although we developed a decision tree, it must be validated in an independent external cohort before it can be accepted in clinical practice. Third, some might argue that elevated mPA > 30mmHg during exercise may be a consequence of increasing age. However, we did not find any difference in younger versus older age groups regarding exercise hemodynamics, providing some confidence in our results. Finally, we acknowledge the small sample size that was utilized to model the decision tree. Our decision tree should be considered preliminary until validated in another independent sample.

In conclusion, we have characterized 4 potential hemodynamic phenotypes of SSc spectrum that emerge during exercise RHC. Further studies including SSc patients with borderline mPA 21–24 and/or exercise physiology consistent with ePH and eoPH are warranted. To this end, we are actively enrolling SSc patients with isolated exercise PH to receive open-label therapy with ambrisentan as part of a single center clinical pilot study. Finally, our decision tree algorithm will require external validation incorporating a larger number of subjects and longitudinal followup before it can be used in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: Dr. Rajeev Saggar has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. D. Khanna was supported by a National Institutes of Health Award (NIAMS K23 AR053858-03) and the Scleroderma Foundation (New Investigator Award).

Footnotes

Dr. Furst has no conflicts to disclose. Dr. Shapiro has no conflicts to disclose. Mr. Maranian has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Belperio has no conflicts of interests to disclose. Mr. Chauhan has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Clements has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Gorn has no conflicts of interests to disclose. Dr. Weigt has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Ross has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Lynch has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Rajan Saggar has no conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Charles C, Clements P, Furst DE. Systemic sclerosis: hypothesis-driven treatment strategies. Lancet 2006;367:1683–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol 1988;15:202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schachna L, Medsger TA,, Dauber JH, et al. Lung transplantation in scleroderma compared with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3954–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badesch DB, Abman SH, Simonneau G, Rubin LJ, McLaughlin VV. Medical therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: updated ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2007;131:1917–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France: results from a national registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1023–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steen V, Medsger TA, Jr. Predictors of isolated pulmonary hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis and limited cutaneous involvement. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukerjee D, St George D, Coleiro B, et al. Prevalence and outcome in systemic sclerosis associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: application of a registry approach. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1088–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badesch DB, Tapson VF, McGoon MD, et al. Continuous intravenous epoprostenol for pulmonary hypertension due to the scleroderma spectrum of disease. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:425–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh ET, Lee P, Gladman DD, Abu-Shakra M. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis: an analysis of 17 patients. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:989–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steen VD, Graham G, Conte C, Owens G, Medsger TA, Jr. Isolated diffusing capacity reduction in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 1992;35:765–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacGregor AJ, Canavan R, Knight C, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis: risk factors for progression and consequences for survival. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:453–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murata I, Kihara H, Shinohara S, Ito K. Echocardiographic evaluation of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with progressive systemic sclerosis and related syndromes. Jpn Circ J 1992;56:983–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jais X, Launay D, Yaici A, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus- and mixed connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a retrospective analysis of twenty-three cases. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:521–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertoli AM, Vila LM, Apte M, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US Cohort LUMINA XLVIII: factors predictive of pulmonary damage. Lupus 2007;16:410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson SR, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Ibanez D, Granton JT. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic lupus. Lupus 2004;13:506–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pope J An update in pulmonary hypertension in systemic lupus erythematosus - do we need to know about it? Lupus 2008;17:274–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hachulla E, Gressin V, Guillevin L, et al. Early detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: a French nationwide prospective multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Angelo WA, Fries JF, Masi AT, Shulman LE. Pathologic observations in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). A study of fifty-eight autopsy cases and fifty-eight matched controls. Am J Med 1969;46:428–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Condliffe R, Kiely DG, Peacock AJ, et al. Connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern treatment era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:151–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathai SC, Hummers LK, Champion HC, et al. Survival in pulmonary hypertension associated with the scleroderma spectrum of diseases: impact of interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:569–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolle JJ, Waxman AB, Van Horn TL, Pappagianopoulos PP, Systrom DM. Exercise-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2008;118:2183–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovacs G, Berghold A, Scheidl S, Olschewski H. Pulmonary arterial pressure during rest and exercise in healthy subjects A systematic review. Eur Respir J 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reichenberger F, Voswinckel R, Schulz R, et al. Noninvasive detection of early pulmonary vascular dysfunction in scleroderma. Respir Med 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Proudman SM, Stevens WM, Sahhar J, Celermajer D. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: the need for early detection and treatment. Intern Med J 2007;37:485–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukerjee D, St George D, Knight C, et al. Echocardiography and pulmonary function as screening tests for pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:461–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badesch DB, Champion HC, Sanchez MA, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:S55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steen V, Chou M, Shanmugam V, Mathias M, Kuru T, Morrissey R. Exercise-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with systemic sclerosis. Chest 2008;134:146–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erickson KW, Costanzo-Nordin MR, O’Sullivan EJ, et al. Influence of preoperative transpulmonary gradient on late mortality after orthotopic heart transplantation. J Heart Transplant 1990;9:526–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murali S, Kormos RL, Uretsky BF, et al. Preoperative pulmonary hemodynamics and early mortality after orthotopic cardiac transplantation: the Pittsburgh experience. Am Heart J 1993;126:896–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc.; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1573–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekelund LG, Hofmagren, A. Central Hemodynamics During Exercise. Circulation Research 1967;XX and XXI:33–43.6028852 [Google Scholar]

- 32.West JB. Left ventricular filling pressures during exercise: a cardiological blind spot? Chest 1998;113:1695–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler R, Faller M, Weitzenblum E, et al. “Natural history” of pulmonary hypertension in a series of 131 patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaouat A, Naeije R, Weitzenblum E. Pulmonary hypertension in COPD. Eur Respir J 2008;32:1371–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grunig E, Janssen B, Mereles D, et al. Abnormal pulmonary artery pressure response in asymptomatic carriers of primary pulmonary hypertension gene. Circulation 2000;102:1145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grunig E, Koehler R, Miltenberger-Miltenyi G, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension in children may have a different genetic background than in adults. Pediatr Res 2004;56:571–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovacs G, Maier R, Aberer E, et al. Borderline Pulmonary Arterial Pressure is Associated with Decreased Exercise Capacity in Scleroderma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weitzenblum E, Chaouat A. Severe pulmonary hypertension in COPD: is it a distinct disease? Chest 2005;127:1480–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weitzenblum E, Ehrhart M, Rasaholinjanahary J, Hirth C. Pulmonary hemodynamics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and other interstitial pulmonary diseases. Respiration 1983;44:118–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alkotob ML, Soltani P, Sheatt MA, et al. Reduced exercise capacity and stress-induced pulmonary hypertension in patients with scleroderma. Chest 2006;130:176–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins N, Bastian B, Quiqueree L, Jones C, Morgan R, Reeves G. Abnormal pulmonary vascular responses in patients registered with a systemic autoimmunity database: Pulmonary Hypertension Assessment and Screening Evaluation using stress echocardiography (PHASE-I). Eur J Echocardiogr 2006;7:439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raeside DA, Smith A, Brown A, et al. Pulmonary artery pressure measurement during exercise testing in patients with suspected pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2000;16:282–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castelain V, Chemla D, Humbert M, et al. Pulmonary artery pressure-flow relations after prostacyclin in primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:338–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Provencher S, Herve P, Sitbon O, Humbert M, Simonneau G, Chemla D. Changes in exercise haemodynamics during treatment in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2008;32:393–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamada K, Nagai S, Tanaka S, et al. Significance of pulmonary arterial pressure and diffusion capacity of the lung as prognosticator in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2007;131:650–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nathan SD, Shlobin OA, Ahmad S, et al. Serial development of pulmonary hypertension in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiration 2008;76:288–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fishman AP. Hypoxia on the pulmonary circulation. How and where it acts. Circ Res 1976;38:221–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahlborg G, Weitzberg E, Lundberg J. Metabolic and vascular effects of circulating endothelin-1 during moderately heavy prolonged exercise. J Appl Physiol 1995;78:2294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stebbins CL, Symons JD, McKirnan MD, Hwang FF. Factors associated with vasopressin release in exercising swine. Am J Physiol 1994;266:R118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dorfmuller P, Humbert M, Perros F, et al. Fibrous remodeling of the pulmonary venous system in pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue diseases. Hum Pathol 2007;38:893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]