Abstract

There is a growing literature on the potential contributions the global forest sector could make toward long-term climate action goals through increased carbon sequestration and the provision of biomass for energy generation. However, little work to date has explored possible interactions between carbon sequestration incentives and bioenergy expansion policies in forestry. This study develops a simple conceptual model for evaluating whether carbon sequestration and biomass energy policies are carbon complements or substitutes. Then, we apply a dynamic structural model of the global forest sector to assess terrestrial carbon changes under different combinations of carbon sequestration price incentives and forest bioenergy expansion. Our results show that forest bioenergy expansion can complement carbon sequestration policies in the near- and medium-term, reducing marginal abatement costs and increasing mitigation potential. By the end of the century these policies become substitutes, with forest bioenergy expansion increasing the costs of carbon sequestration. This switch is driven by relatively high demand and price growth for pulpwood under scenarios with forest bioenergy expansion, which incentivizes management changes in the near- and medium-term that are carbon beneficial (e.g., afforestation and intensive margin shifts), but requires sustained increases in pulpwood harvest levels over the long-term.

Keywords: Bioenergy expansion, Forestry, Carbon sequestration

1. Introduction

The global land use sectors could play an important role in future efforts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and stabilize projected climate changes, both as a continued terrestrial carbon sink and as a source of agriculture- and forest-derived biomass for energy generation. Several recent studies have applied integrated assessment models (IAMs) to project global GHG mitigation potential from different sectors of the economy under assumed representative CO2 emissions concentration pathways (RCPs), including contributions from the land use sectors (e.g., Van Vuuren et al., 2017). Under assumptions of decreased or stabilized GHG emissions trajectories (e.g., RCP 2.6), different integrated assessment models vary significantly in their projections of how the energy, transportation, industrial, and land use sector activities might evolve over time to reach these assumed emissions reduction targets. However, the IAMs show consistency in one aspect—the global forest and land use sectors are expected to play an important role in sustaining or enhancing terrestrial carbon stocks and supplying requisite biomass under the most aggressive emissions reduction pathways. In fact, some estimates indicate that forestry and land use activities could supply 20% or more of the anthropogenic emissions reductions needed to hit climate stabilization targets (Riahi et al., 2017).

However, IAMs and other economy-wide modeling efforts typically to do not represent forest resource systems and product markets in significant detail, ignoring important regional differences in the forest resource base, potential market feedback of policy or environmental changes, and the role of investment in response to (or in anticipation of) policy or market shifts. This limited depiction of the forest resource base can lead to over- or understated emissions reduction contributions from forestry in integrated modeling studies. For example, most IAMs do not allow for endogenous intensification of forests in response to policy stimuli, which could understate the sector’s role in reducing emissions as management intensification can directly increase terrestrial carbon (Tian et al., 2018). Alternatively, economy-wide models may over-project emissions reduction contributions from forestry through land use change due to less detailed representations of biological growth rates, land use change costs, and forest product markets and trade flows. Recent IAM studies have projected large shifts between alternative land uses, which assumes that land is fungible and that moving land from one use to another under a modest policy change is a relatively low-cost mitigation strategy (e.g., recent IAMs have projected afforestation of marginal lands for increased carbon sequestration). Finally, economy-wide models are sometimes limited in their ability to isolate the implications of a single policy or combinations of policies for an individual sector (e.g., forestry) with spatial heterogeneity and sector-specific detail, and thus may not be always be well served to examine issues related to policy design.

Given the importance integrated assessment models place on the forest sector activities to contribute to future energy policy and GHG emissions reduction efforts globally, additional analysis exploring potential trade-offs and synergies of policy mechanisms incentivizing bioenergy expansion and/or increased terrestrial carbon storage is essential to further inform policy decisions. This analysis offers a detailed, sector-specific perspective on the implications of alternative policy futures on forest markets and land management. Specifically, this analysis builds upon scenarios and assumptions presented in recent economy-wide analysis of long-term climate stabilization pathways with a more targeted analysis on the potential role of forests in contributing to a hypothetical low-carbon policy future (White House, 2016a). The analysis applies an updated model of the global forestry sector to evaluate several combinations of policies, including forest biomass energy expansion and forest carbon sequestration payment programs.

This paper makes several unique contributions to the literature. First, most studies consider incentives only for biomass energy or carbon sinks independently (e.g., Kinderman et al., 2008; Daigneault et al., 2012; Favero and Mendelsohn, 2014; Latta et al., 2013; Galik and Abt, 2016). One recent study by Favero et al. (2017) does examine the path of forests as a source of biomass energy and terrestrial carbon storage using an earlier version of the forestry model used here, finding that forests would best serve as a carbon sink initially, and later as a large supply of biomass energy for a carbon capture and storage program. Favero et al. (2017) found that forests were an expensive source of biomass initially, a result that could be driven by assumed carbon price paths, availability of lower cost agricultural sources of biomass, relatively high costs of bioenergy with CCS technologies, or perhaps because they assumed forests were homogeneous, and thus did not explicitly include a lower cost source of pulpwood-based forest biomass. Our study updates this earlier model and allows forest biomass to be used as an input for biomass energy with or without carbon capture and storage, and we include heterogeneous demand in forest products with a pulpwood and sawtimber demand function. Since pulpwood has a lower price than sawtimber, our costs for producing biomass energy from forests are approximately a third less than the earlier study by Favero et al. (2017).

Second, this study attempts to more formally define carbon complementarity and substitution between policy efforts. In the literature, forest biomass expansion policies are most often discussed as efforts that inherently remove carbon from the landscape (potentially reducing net sequestration) while displacing emissions in the energy system. Carbon sequestration payment programs are assumed to increase net sequestration on the landscape or in wood product markets. While previous research has acknowledged possible complementarity between forest bioenergy and carbon sequestration policies (e.g., Favero et al., 2017), this study attempts to explicitly quantify the level of complementarity between these policies by region and over time using dynamic economic modeling methods. We define these policies as either being strong complements (the net carbon benefits of policies implemented together is greater than the sum of the two implemented in isolation), weak complements (when the combined effect exceeds the mitigation potential from the carbon sequestration policy implemented without the bioenergy policy), and substitutes (the combined effect is less than the mitigation potential from the carbon sequestration policy implemented without the bioenergy policy). We simulate forest management and market outcomes under different incentive structures for the carbon sequestration policy and the bioenergy expansion policy, and then vary the mitigation price while holding the forest biomass demand constant. This allows us to assess whether a given bioenergy policy adds to the forest carbon stock or subtracts from it and how this policy interacts with varying carbon sequestration payment incentives. We also deploy a dynamic global model of forest resource management and markets to explore whether the relationship between the two programs changes over time and to assess potential complementarity by region. Finally, we explore interactions between pulpwood and sawtimber prices and terrestrial carbon to offer insight into key interactions between energy and GHG policies, markets, and environmental outcomes.

Results show that bioenergy expansion and forest carbon sequestration incentives have the potential to be complementary in the nearand medium term as combining policies creates a favorable policy environment for forest resource investment and management changes. Hence, net GHG abatement is lower cost when these policies are combined relative to a case in which forest carbon sequestration incentives are pursued in isolation. Results also show strong interactions between pulpwood and sawtimber markets and exogenous policy drivers that influence carbon outcomes. Over the long term (2090 and beyond) these policies become substitutes due to the opposing forces of sustained pulpwood demand for bioenergy and the competition that this demand has with activities that directly sequester carbon on the landscape (such as extended rotation lengths and reduced deforestation). The paper closes with a brief discussion of the potential policy implications of this key result.

2. Literature review

There is a substantial literature focused on climate mitigation activities in the forest sector that could result in greater levels of terrestrial carbon storage, including improved forest management (IFM; i.e., longer rotations), reduced emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD+), and afforestation (Van Winkle et al., 2017; Baker et al., 2017; McGlynn et al., 2016; Haim et al., 2014; Jackson and Baker, 2010; Lubowski et al., 2006; Sohngen, 2008; Murray et al., 2004; U.S. EPA, 2005; Sohngen and Mendelsohn, 2003). Methodologies have varied from reduced form econometric simulation approaches focused on a single activity such as afforestation (e.g., Lubowski et al., 2006) to partial equilibrium structural economic models at different spatial and temporal scales (e.g., Jackson and Baker, 2010). The structural modeling approaches typically evaluate multiple mitigation activities simultaneously for a given sector to project optimal mitigation portfolios under different price and quantity policy mechanisms, and could include market based solutions aimed at limiting emissions from land-use change (e.g., Baker et al., 2010).

Storage of carbon in wood product pools can also boost net carbon storage and sequestration, not only in product markets but in terrestrial systems as well (Tian et al., 2018), as anticipated increased future demand for wood products can encourage near-term investments in the forest resource base, including extensive and intensive margin shifts that boost terrestrial carbon uptake (Tian et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018). Forest-based climate change mitigation action is already happening in different regions under a variety of conservation policies and programs than offer payments for carbon sequestration. Several countries have dedicated significant climate financial resources to reduce deforestation and enhance forest carbon stocks globally, including an effort led by Germany, Norway, and the UK that will support up to $5 billion in new forestry projects to reduce emissions annually out to 2020. Furthermore, in the U.S., California’s regional GHG cap and trade program (AB32) allows capped entities to purchase GHG allowance offsets from non-capped sectors such as forestry, and this has created an emerging market for forest offsets from IFM and afforestation projects.

Forests are could also play an expanded role in supplying requisite biomass to meet renewable energy targets globally. Expansion of wood pellet trade between North America and the E.U. grew more than 80% between 2010 and 2015, and this trend is expected to continue in the coming years, which could have a significant impact on biomass trade flows. The surge in pellet demand has been driven predominately by renewable energy policies in the United Kingdom and European Union, creating a new market for biomass resources as a fuel source for electricity generation to displace more emissions intensive sources of electricity (e.g., coal-fired electricity). There are other policies or market projections documented in the literature that could further increase the demand for forest-derived bioenergy for electricity, industrial, and transportation sector use (Kim et al., 2018).

While the GHG displacement potential of forest-derived bioenergy relative to fossil fuel equivalents is debated in the literature, there is increasing recognition that the land use sectors could play an important role in global energy futures by providing requisite biomass to meet future bioenergy demand. Among the possible drivers of future bioenergy demand could be negative emissions technology deployment to meet climate stabilization targets over the long term (2050 and beyond (Riahi et al., 2017)). Biomass energy with carbon capture and sequestration (BECCS) is one such negative emission technology pathway that has been summarized in integrated assessment modeling studies as a key energy sector strategy needed to meet long climate and energy policy targets (e.g., Van Vuuren et al., 2013; Riahi et al., 2017). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Annual Report suggests that by the second half of the 21st century, negative emissions from BECCS could offset as much as 50% of current annual emissions (IPCC, 2014). Integrated assessment models have been used to determine the optimal scale and location of BECCS (Kraxner et al., 2014a, 2014b(2)); the optimal allocation of forests to sequester carbon and supply biomass (Eriksson, 2015); to determine the spatial distribution of CCS systems on different types of power plants; and to look at how different mitigation and adaptation technologies can affect society’s ability to meet climate goals (Muratori et al., 2016). Much of this literature has focused on the use of dedicated energy feedstocks such as switchgrass or miscanthus to support potential BECCS demand but given the substantial stock of forest resources available for use, it is important to also consider forests.

Other studies have focused more explicitly on the role of forests in reaching long-term BECCS targets and, more broadly, in evaluating a suite of mitigation strategies from forestry and bioenergy-related activities. Forests are unique in their ability to generate emissions reduction through primary production pathways (carbon stored in terrestrial systems and wood products), as well as the ability to generate raw material for the production of wood chips and wood pellets for bioenergy (Kraxner et al., 2014a, 2014b), so forest-related action is often favored in integrated assessment modeling studies. Kraxner et al. (2014a, 2014b) combine a biophysical global forestry model (G4M) to an engineering model (BeWhere) to estimate forest biomass availability in Japan and to optimize the scale and location of Combined Heat and Power Carbon Capture and Storage plants, finding that 10% of current energy production in Japan could be replaced by forest-derived bioenergy, and that 3–4% of fossil fuels emissions could be substituted and additionally accounted for as negative through the use of BECCS (Kraxner et al., 2014a, 2014b). Favero and Mendelsohn (2014) use a previous version of the Global Timber Model (GTM) coupled with the World Induced Technical Change Hybrid model (WITCH) to investigate the effects of bioenergy markets to encourage the growth of forests. The two models were integrated by combining the demand for bioenergy from the WITCH model with the supply of wood for fuel from GTM. This effort shows that not only is there sufficient global forest-derived biomass to support large-scale BECCS programs, but through the implementation of BECCS forest sequestration increases due to non-forested land being converted to forest because of higher timber prices. Favero et al. (2017) builds on this analysis to compare scenarios in which forests are only allowed to store additional carbon to scenarios where forests are used for carbon sequestration and for inputs into BECCS. Favero et al. (2017) concludes that forest bioenergy and carbon sequestration policies can be complementary, and results highlight the importance of temporal considerations and portfolio approach for efficiently utilizing forests to reduce GHG emissions globally.

Our analysis provides additional insight into potential policy complementarity and between forest bioenergy and carbon sequestration efforts and additional temporal considerations through a dynamic analysis of exogenous policy incentives that drive forest management and terrestrial carbon outcomes. By interacting consistent near-term policy scenarios in our modeling framework, we can directly test for the level of complementarity between policies and asses how this effect may change over time and by region.

3. Methods and model description

This section provides more information on the modeling framework applied in this analysis, a conceptual framework for evaluating carbon complementarity between biomass energy and carbon sequestration policies and describes our scenario design.

3.1. Model description

This paper uses the Global Timber Model (Tian et al., 2018) to assess the interaction between biomass energy incentives and carbon sequestration incentives. The version of the model used here differs from the model used in Favero et al. (2017) in that we assume heterogeneous products in wood demand, with separate demand functions for pulpwood and sawtimber. Pulpwood and sawtimber are chosen as the two representative wood products as these aggregates encompass the vast majority of forest biomass removals for timber products. Thus, our model reflects the supply and demand of most marketable biomass removals as well as forest management operates for enhancing carbon sequestration. Biomass energy is an undifferentiated commodity (i.e., it is not graded like sawtimber) that can compete strongly with pulpwood. By differentiating demand for the two, the model allows biomass energy to be supplied from a lower cost option and thus potentially increases the supply of available biomass energy relative to the Favero et al. (2017) study.

Biomass energy demand is modeled as a shift in the demand functions for wood products (both pulpwood and sawtimber demands increase). Carbon demand is modeled by giving payments for (i.e., renting) the standing stock of forest biomass carbon and paying for the carbon permanently stored in wood products. For this analysis, we assume that the emissions of biomass energy production are emitted to the atmosphere. We have not attempted to account for the potential displacement of traditional energy resource use and related emissions by biomass energy, which should reduce the net emissions contribution to the atmosphere. Those assumptions would differ by region, over time, and possibly by specific woody feedstock type, and thus are outside the scope of this analysis. These assumptions, plus the exclusion of less commonly targeted mitigation strategies in our framework (e.g., use of wood products as a substitute for energy intensive building materials), implies a potential underestimate of emissions reductions under the influence of exogenous policy incentives.

The Global Timber Model (GTM) was developed to conduct long-term analysis of important natural resource issues facing the forest sector (Sedjo and Lyon, 1990; Sohngen et al., 1999). It has been used for a wide range of climate change related policy analyses, including climate change impacts (Sohngen et al., 2001; Tian et al., 2016, 2018), forest carbon sequestration (Sohngen and Mendelsohn, 2003; Kinderman et al., 2008; Baker et al., 2017), and bioenergy (Daigneault et al., 2012; Favero and Mendelsohn, 2014). The code and data for the baseline model used for this analysis was recently made publicly available through Tian et al. (2018).

The model maximizes the net present value of consumers’ surplus minus the costs of timber production, including the opportunity costs of holding land in forests. The model includes two types of wood products, sawtimber and pulpwood, and these products are represented by different demand functions. Timber that is harvested in the model is allocated to each use depending on the price, and the costs of harvesting and transporting each type of wood to a sawmill. Other costs of management in the model include intensification costs, replanting, and residual collection costs.

The model determines global prices endogenously with harvests, land area, and management for each of the land classes in the model. In the current version used for this paper, there are more than 150 forest and management types in the US, and over 200 forest and management types in 18 regions of the world. The model chooses the area of land to harvest in each age class and time period, how much land to regenerate, the amount to spend on regeneration (management intensity). The model is forward looking, and thus solves all time periods simultaneously, meaning that foresters account for future prices when making current decisions.

The forward-looking nature of the model has two important implications. First, timber harvesting occurs at the economically optimal rotation age, which balances the marginal benefits of waiting an additional period to harvest the trees with the marginal costs. These marginal benefits and costs are heavily influenced by carbon and energy policies. Second, investments made in newly regenerated forests are based on expected returns decades from now. Thus, the planting and management expenditures at planting time are made in a way that is consistent with future expectations about timber demand and prices.

The dynamic perspective in GTM is useful for assessing the relationship between long run shifts in demand for biomass and carbons sequestration. In particular, we are able to evaluate the effects of changes in policy assumptions on changes in forest sector investment and management. This is particularly important for achieving policy goals towards the middle of this century. If forests are to be used as a source of climate mitigation, efforts will have to be made to influence forests in the near term as well. As a global model, GTM is also suited to account for the market linkages across regions. Thus, policies that adjust demand for biomass or carbon in any particular region of the world could affect carbon fluxes and storage in the US. It is important to consider these interactions as projected changes in the U.S. forest resource base (including harvest levels) will be driven by forest markets and resource utilization pathways in the rest of the world.

Additional detail on the version of the model used for this analysis, including the general algebraic structure of the model and a list of key parameters and variables, are found in a supplemental appendix to the U.S. Mid-Century Strategy for Deep Decarbonization (White House, 2016b).

3.2. Defining carbon complementarity

For the purposes of our analysis, we define two types of complementarity: strong and weak, with two potential boundaries for the analysis: forest carbon (including product pools) and total atmospheric carbon (including potential displaced fossil fuel emissions from the bioenergy activity). Cumulative forest carbon stock changes resulting from model projections are summarized by Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where Ft represents annual flux changes for forest carbon pools (e.g., aboveground and belowground biomass carbon sequestration, harvest emissions, soil carbon, and carbon and decay emissions associated with litter and understory biomass) and Pt represents carbon stored in forest product pools. ForestC0 is the initial carbon stock in t = 0 across all carbon pools, and T represents the temporal scope (relevant future time period) for the analysis. For some policies or programs, it may be important to consider total atmospheric carbon changes resulting from increased biomass consumption for energy generation. The total atmospheric change would include the sum of forest carbon sequestration changes under a new policy future relative to a baseline (or base period), plus the net change in atmospheric carbon once displaced fossil fuel emissions have been accounted for, as expressed by Eq. (2):

| (2) |

Here, Biot represents the amount of forest biomass allocated to bioenergy uses, αj is the proportion of forest biomass allocated to bioenergy pathway j, and Øj is an energy equivalent emissions displacement factor for some fossil energy resource. AtmosphericC0 represents the initial atmospheric stock in the atmosphere and Et represents the change in emissions over time from non-forestry activities. Evaluating carbon complementarity requires comparison of ForestCT and/or AtmosphericCT across different scenarios, including a baseline with no bioenergy or carbon sequestration incentive (the No Policy case in this analysis). Strong complementarity occurs if the net change in carbon when both policies are in effect is greater than the sum of the net changes under the two policies individually. Weak complementarity, in contrast, holds only when net mitigation under both policies is greater than mitigation under the carbon policy alone.

It may be important to consider carbon complementarity for forest carbon in isolation, or for net atmospheric carbon, depending on the scope of the policies or programs under consideration. Note that if the net change in forest carbon stocks (ForestCT) when moving from a no policy baseline to a bioenergy expansion scenario is positive, then the policy results in a net increase in terrestrial carbon storage with the bioenergy policy incentive (negative emissions), and hence a net decrease in atmospheric carbon. If this sequestration change is negative (positive emissions), then the increased use of biomass for energy results in an increase in GHG emissions over that time frame, but the overall GHG profile can still be desirable relative to fossil fuel equivaT lents (that is if the policy can still be carbon beneficial). For this analysis, Et and are constant for scenarios with the bioenergy incentive, so whenever forest carbon complementarity holds, so will atmospheric carbon complementarity. Thus, we do not directly consider energy emissions displacement and focus exclusively on terrestrial carbon changes as this is more consistent with the global demand shift applied to pulpwood and sawtimber for the bioenergy scenarios.

Formally, if we compare forest carbon outcomes between the no policy baseline and the bioenergy expansion policy baseline, the bioenergy effect on total forest carbon is:

| (3) |

The effect of a forest-based carbon sequestration policy via carbon pricing relative to a no policy baseline is defined as:

| (4) |

Mitigation potential for scenarios that combine forest-based mitigation and bioenergy expansion efforts are described by , which compares carbon outcomes over time under a combined policy relative to a baseline with the bioenergy policy in place.

| (5) |

Finally, the combined (net) effect, shown in Eq. (6), compares mitigation outcomes under a combined policy case to the no policy baseline.

| (6) |

Strong complementarity occurs if the net forest carbon change resulting from the combined policy framework is greater than both the mitigation policy change and the bioenergy policy change , or:

| (7) |

Weak complementarity is:

| (8) |

Weak complementarity in this context simply requires that net forest carbon changes resulting from a mitigation policy combined with bioenergy expansion relative to a no policy baseline be greater than the combined policy effect relative to a baseline with the bioenergy expansion incentive. This condition focuses directly on the interaction between the policies and whether the net change in emissions for a combined policy case exceed carbon changes for a mitigation policy in isolation. Note that weak complementarity will only hold when is positive. When is negative, we assume that any case in which offers strong complementarity. In this case, the combined effect of the policies outweighs the individual effects of reduced forest carbon stocks from bioenergy and increased sequestration from the mitigation policy. Bioenergy and carbon sequestration policies are substitutes whenever . Our results show examples of all three (strong and weak complementarity as well as substitution).

3.3. Scenario design

For this study, we developed alternative future scenarios of macroeconomic drivers and various policy variables focused on biomass energy demand and carbon sequestration policies. The baseline market and policy drivers were chosen to align to the U.S. Mid-Century Strategy (MCS) Benchmark Scenario developed with the Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM) (White House, 2016a). We do not formally link GTM and GCAM, but we use elements from a specific GCAM analysis as inputs to this dynamic GTM modeling effort. This scenario was chosen as a plausible macroeconomic future in which GHG mitigation through forest bioenergy expansion and carbon sequestration is likely to be incentivized, along with other mitigation strategies, through various price and quantity mechanisms. Three separate scenario sets (in addition to a “no policy” baseline) are applied in this paper to reflect different forest-derived biomass and carbon sequestration incentives. These scenarios are:

No Policy Baseline: Also referred to in the results and discussion section as the “No Bioenergy Baseline.” The GCAM regional GDP and population projections from the GCAM baseline from the U.S. MCS Benchmark scenario are aggregated for the world and used as inputs in GTM. The resulting baseline GDP growth rate is 1.8% per year on average for 50 years, falling to 1.6% per year for the subsequent 50 years, and 1.0% per year thereafter. Demand growth falls to 0.0% per year in the final two decades before terminal conditions are imposed. Income elasticity for both sawtimber and pulpwood of 0.9, implying that most of the income growth is translated into demand growth.

Baseline with Bioenergy Expansion: For this scenario, the same GDP and population growth rates are used, but we add demand growth for woody biomass used for energy generation purposes. These demands are consistent with the MCS Benchmark scenario. Specifically, we made a conservative assumption about the amount of total biomass energy demand that will be fulfilled by the forestry sector (all of the forest residue production reported in the MCS Benchmark Scenario plus 25% of the reported category "purpose grown biomass all other"). Total forest biomass for energy consumption grows from 12.4 Million tonnes (Mt) initially in 2015 to approximately 220 Mt in 2030, and then to a peak of approximately 480 Mt in 2060. This volume represents 0.8% of the reported biomass consumption for energy generation in the MCS Benchmark Scenario in the 2015 reported year, 7% in 2030, and approximately 8.5% in 2050 onward. By mid-century, this additional biomass demand equates to approximately 10–12% growth in total pulpwood and sawtimber demand. Consumption levels are converted from Gigajoules to million m3 of forest biomass, and demand for both pulpwood and sawtimber accordingly, using constant conversion factors of 105.82 m3/EJ and 0.6 metric tons per m3. We assume that 70% of the increased wood is derived from pulp and 30% from sawtimber. This split recognizes that while pulpwood and residual biomass will likely provide the dominant share of energy biomass from forests, sawtimber could also be used to meet this increased demand, especially if regional prices are high enough. The aggregate change in demand for pulpwood and sawtimber to reach bioenergy target plateaus in 2060. Finally, in our framework residual biomass is fungible in the pulpwood market and can be used for bioenergy purposes. As pulpwood or bioenergy demand increases, and prices grow, more residue biomass is allocated to meet this increased demand (see Kim et al., 2018 for more discussion).

- Carbon Sequestration Payment Scenarios—No Bioenergy: Exogenous carbon rental payments are included in the model to incentivize increased carbon sequestration in aboveground forest biomass and payments for permanent storage in wood products, as described in Sohngen and Mendelsohn (2003). We consider exogenous carbon sequestration price paths that do not specifically relate to the size of the biomass energy expansion policy. We kept these policies separate but interacted accordingly for a direct test of complementarity between two policies that seek to reduce GHG emissions through often opposing mechanisms (increased biomass removals for energy generation purposes and increased carbon update on the landscape). One rationale for this approach is to more closely model a policy reality, which is that we observe that carbon sequestration policy and biomass policy development and implementation in practice run on separate tracks, with sequestration policy focusing largely on enrolling land in afforestation, forest management (e.g., FSC or reduced impact logging), or avoided deforestation schemes in exchange for annual rent payments for the carbon saved, and the biomass policies focusing largely on quantity constraints imposed on fuel blenders or energy producers. This ‘dual track’ approach is how we have implemented the bioenergy and carbon sequestration policies in our framework (consistent with other modeling applications). Furthermore, there are other reasons that the land use sectors might face a different set of mitigation incentives than the energy and industrial sectors, as discussed in the Shared Climate Policy Assumptions developed Kriegler et al. (2013), thus the use of distinct and exogenous carbon sequestration and biomass energy expansion policy incentives is justified. The following forest carbon sequestration payment scenario price paths were evaluated, assuming growth rates of 1% and 5% annually (with growth in mitigation prices halted after the 2120 simulation period for the higher price scenarios).

-

○$5/tCO2e, $20/tCO2e, $35/tCO2e, and $50/tCO2e

-

○

Carbon Sequestration Payment Scenarios—With Bioenergy: This set of scenarios uses the same set of mitigation price paths described above forest carbon sequestration while also adjusting pulpwood and sawtimber demand to reflect forest bioenergy expansion consistent with the Baseline with Bioenergy Expansion scenario, thus combining bioenergy and carbon sequestration incentives.

For this analysis, GTM was run for 200 years at 10-year time steps using the GAMS software. More information on the modeling approach plus forest inventory and yield information used in this study can be found in the supplement to the MCS (White House, 2016b). The scenario design is developed to provide long-term projections of U.S. and global forest carbon stocks across a wide range of scenarios that reflect different climate and bioenergy policy assumptions.

4. Results and discussion

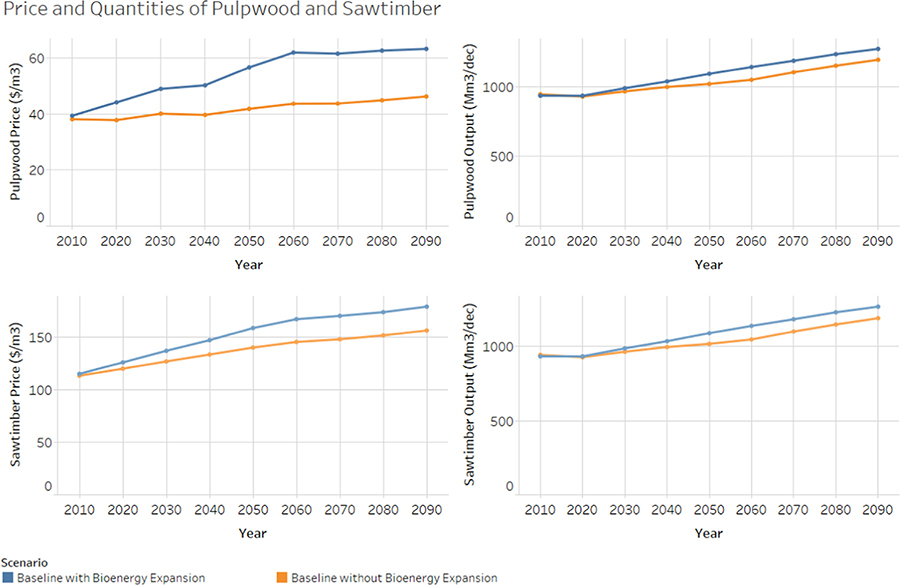

Fig. 1 shows baseline projections for pulpwood and sawtimber production and prices. Two different baseline projections are provided—with and without the bioenergy expansion policy (Bioenergy Expansion Baseline and No Policy Baseline, respectively). Under the no policy baseline, prices and production both rise globally for pulpwood and sawtimber. Pulpwood and sawtimber prices rise by approximately 0.2% and 0.3% per year, respectively, by the end of the century for the baseline without bioenergy. Under the same scenario, pulpwood and sawtimber production rise by 0.4% and 0.3% per year, respectively. When additional bioenergy expansion is included, the demand for pulpwood and sawtimber grows, causing pulpwood and sawtimber prices to rise relative to the no bioenergy expansion baseline. The difference in projected prices and production with and without bioenergy expansion is consistent after 2050 as the bioenergy expansion policy culminates mid-century and the related increase in forest biomass demand is held constant through the remainder of the simulation horizon. However, before this convergence pulpwood prices are approximately 50% higher with bioenergy beginning around 2050. Prices for sawtimber in the bioenergy scenario diverge from the no bioenergy scenario by approximately 12% in 2050.

Fig. 1.

Baseline pulpwood and sawtimber price and quantity projections (with and without bioenergy expansion).

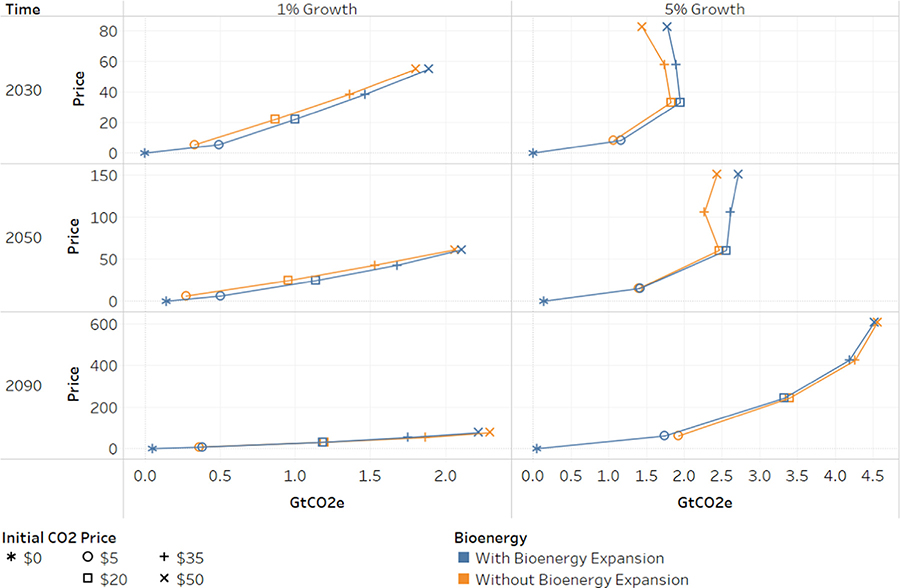

Comparing projected carbon fluxes from the forest carbon scenarios relative to the no policy baseline allows for an appropriate comparison between the policy implications of carbon sequestration payment incentives in isolation and when coupled with bioenergy expansion efforts. Eight carbon sequestration prices scenarios are included for the with and without biomass expansion. This includes four different prices for carbon ($5, $20, $35, and $50 per ton CO2) each of these growing at 1% and 5% annually. So, in all, there are 16 different carbon sequestration scenarios. An increase in mitigation potential from carbon sequestration policies that include bioenergy expansion compared to those without bioenergy under the same mitigation price incentives suggests that there is complementarity between carbon and bioenergy policies. This result means that when implemented together, the presence of increased forest biomass demand driven by bioenergy expansion efforts will lower the costs of emissions mitigation via forest-based carbon sequestration (hence, decreasing abatement costs) relative to a system that just incentivizes carbon sequestration in the global forest sector. Fig. 2 shows global marginal abatement cost curves for three different points in time (annualized), across all four carbon sequestration price scenarios, and both with and without bioenergy expansion.1 Net global carbon stock changes for the baseline with bioenergy expansion relative to the no bioenergy baseline are small, with a small decrease in total carbon storage by 2030 (− 0.002 GtCO2e annual change). Annual sequestration increases slightly with bioenergy expansion by mid- and late-century (0.14 and 0.05 GtCO2e for 2050 and 2090, respectively). When forest carbon sequestration policies are combined with bioenergy expansion efforts, there is a distinct upward shift in mitigation potential, ranging 0.49–1.95 GtCO2e by the 2030 simulation period. Across carbon sequestration policies with bioenergy expansion, net mitigation increases by about 0.15 GtCO2e per year, which is a 10% increase in annual mitigation potential over the near term, averaged across all carbon sequestration policy scenarios. As the net change in carbon storage when including bioenergy expansion relative to the no bioenergy baseline is close to zero by 2030 (and slightly negative) this increase in mitigation output represents strong complementarity between forest bioenergy expansion and carbon sequestration payment policies globally. When evaluated in isolation, all mitigation price scenarios exhibit strong global complementarity between bioenergy and carbon sequestration payment policies over the near term.

Fig. 2.

Average annual mitigation potential across carbon sequestration payment scenarios over three time-frames, with and without bioenergy expansion. Figures on the left represent marginal abatement cost curves with 1% mitigation price growth scenarios while figures on the right represent the 5% growth scenarios.

By 2050, annual sequestration increases by 0.14 GtCO2e with the bioenergy expansion policy . Over the same time frame, annual mitigation potential (from 2010 to 2050) across the mitigation price scenarios (without bioenergy expansion) ranges 0.27–2.46 GtCO2e. When biomass expansion is combined with carbon sequestration incentives, annual mitigation expands for most carbon sequestration policy scenario. This shift represents a mix of strong and weak complementarity across carbon sequestration policy scenarios. For most cases, we find weak complementarity between carbon sequestration and bioenergy policies, as the gain in carbon sequestration for mitigation scenarios with bioenergy expansion relative to mitigation scenarios without bioenergy expansion is less than the net gain in carbon from bioenergy expansion in isolation (0.14 GtCO2e). However, the two highest mitigation price scenarios, $35 at 5% and $50 at 50%, show strong complementarity effects of 0.28 and 0.34 GtCO2e, respectively. Thus, while bioenergy expansion and carbon sequestration policies appear to complement one another in both the near and medium term (mid-century), the degree of average complementarity begins to subside over time, shifting from strong to weak complementarity for most scenarios.

By 2090, bioenergy and carbon sequestration policies become substitutes in our simulations. By 2090, annual mitigation potential for carbon sequestration scenarios with no bioenergy expansion ranges 0.36–4.6 GtCO2e, which is a substantial increase relative to annual mitigation potential for the near- and medium-term time frames. However, when bioenergy expansion is included annual mitigation potential declines approximately 0.07 GtCO2e (averaged across all mitigation price scenarios), which represents a 3.7% decline in mitigation potential relative to carbon sequestration scenarios with no bioenergy expansion. This decline in policy complementarity is driven by the rise in carbon prices. Biomass policy complements carbon policy at low carbon prices because at lower carbon prices, carbon sequestration and biomass policy use different land. Sequestration focuses on low cost, low value forests precisely because they are low cost, whereas biomass focuses on productive timberlands, which actually are high cost carbon storage units. So at low carbon prices, adding biomass energy policy is complementary. However, when carbon prices are high, marginal costs are high and sequestration and biomass compete for the same forests. Thus, biomass steals away some sequestration opportunities.

Fig. 2 suggests that policies that are complementary in net carbon impacts can also provide benefits through reduced abatement costs. In the near- and medium-term, marginal abatement costs are lower for mitigation scenarios with bioenergy expansion than for scenarios with no bioenergy expansion. This effect is more visually apparent in the 2030 time step, as marginal abatement cost curves start to converge in 2050 with weak complementarity. By 2090, as the policies become carbon substitutes, marginal abatement costs for carbon sequestration increase for combined mitigation and bioenergy expansion scenarios.

In addition to temporal considerations and policy design, the complementarity effect varies substantially across regions and scenarios. Over the near and medium term, not all regions experience strong or weak complementarity from biomass expansion. Table 1 shows the average annual complementarity effect of biomass expansion by region (averaged over all mitigation scenarios) for the three time periods of interest. In addition to the average effect, the minimum and maximum complementarity effect is synthesized in parentheses. All positive values in Table 1 demonstrate strong complementarity, where the combined effect of mitigation policies and biomass expansion outweigh the additional benefits from each of these scenarios separately. However, the negative values in Table 1 do not necessarily represent the absence of complementarity, because there are still situations where the net reduction in CO2 emissions are greater than the emissions in the mitigation policy runs. This is due to some regions seeing increased emissions when bioenergy expansion increases.

Table 1.

Average annual complementarity effect of bioenergy expansion policy on net mitigation over time and by region (MtCO2e).

| Region | 2030 | 2050 | 2090 |

|---|---|---|---|

| US | 30.10 (22.99, 44.21) | 32.22 (26.05, 41.55) | 22.99 (9.83, 33) |

| CHINA | 25.47 (13.3, 49.09) | 34.07 (17.99, 55.49) | 8.59 (− 5.81, 21.81) |

| BRAZIL | 33.09 (9.7, 83.21) | 11.72 (− 2.22, 45.8) | 1.10 (− 10.08, 14.69) |

| CANADA | 1.08 (− 2.34, 7.05) | 3.77 (2.45, 6.03) | 1.94 (− 2.14, 5.26) |

| RUSSIA | − 0.03 (− 6.99, 22.5) | 0.32 (− 1.88, 3.26) | − 5.91 (− 8.96, − 3.36) |

| EU ANNEX I | 21.92 (− 17.27, 66.68) | 35.39 (− 48.45, 152.64) | − 26.83 (− 88.86, 27.43) |

| EU NON ANNEX I | − 2.43 (− 4.76, −0.17) | − 6.87 (− 15.6, − 1.76) | − 12.57 (− 24.93, − 4.14) |

| SOUTH ASIA | 2.24 (0.41, 4.3) | 2.37 (− 1.06, 9.34) | − 0.81 (− 3.16, 1.98) |

| CENT AMER. | 0.55 (− 0.04, 1.26) | 0.36 (− 1.26, 2.27) | − 0.87 (− 3.1, 0.06) |

| RSAM | − 6.16 (− 30.31, 17.77) | − 12.99 (− 56.13, 5.51) | − 19.18 (− 106.67, 14.1) |

| SSAF | 3.07 (− 1.11, 16.06) | 1.15 (− 14.44, 16.14) | − 5.33 (− 14.38, 8.12) |

| SE ASIA | 26.38 (4.18, 111.9) | 66.28 (2.23, 259.67) | − 25.46 (− 51.19, −11.13) |

| OCEANIA | 5.16 (− 1.92, 19.95) | 1.53 (− 26.12, 14.55) | − 0.33 (− 9.52, 8.02) |

| JAPAN | 3.93 (− 0.61, 18.03) | − 2.97 (− 37.13, 5.79) | − 5.84 (− 33.7, 0.33) |

| AFME | 0.11 (− 0.48, 1.97) | 0.18 (− 1.28, 1.17) | − 0.40 (− 1.48, 0.1) |

| E ASIA | 4.31 (0.45, 7.6) | 1.54 (− 0.44, 6.92) | − 0.07 (− 0.3, 0.17) |

Values in parentheses represent the minimum and maximum complementarity effect across mitigation price scenarios; Complementarity effect is calculated as: .

Also, for some regions, bioenergy expansion reduces projected mitigation potential for all time frames (EU non-Annex 1 and the Rest of South America). For other regions, complementarity declines over time (Brazil), and in some cases, this decrease results in bioenergy and traditional mitigation becoming regional substitutes toward the end of the century (e.g., Asia, Europe, and Russia). In the United States, strong complementarity is seen for all time frames and CO2 price scenarios, but the relative strength of the complementarity does decline slightly to weak complementarity by 2090. Finally, some regions (such as the EU Annex 1 and Rest of South America) see large variations in projected mitigation potential and complementarity between biomass expansion and mitigation outcomes. This result is driven in part by global pulpwood price changes. Mitigation action tends to decrease sawtimber prices and increase pulpwood prices, while bioenergy policy similarly increases pulpwood process. Thus, for particular regions that have a relatively large share the global pulpwood market, higher pulpwood prices imply less net sequestration, especially when bioenergy demand is high.

Regional differences and the relative sensitivity of regional forest management responses to policy are driven by a number of key factors, including current age class distributions, marginal costs of intensive and extensive margin expansion, and relative advantages in supplying carbon mitigation and woody biomass. In the U.S., for instance, the no policy baseline sees intensive and extensive margin forest expansion over time. with total forest area increasing by approximately 9 million hectares (Mha) by 2050. When the bioenergy policy is included, this extensive margin shift increases to 12 Mha by 2050. For the $50 at 5% carbon sequestration payment scenario with bioenergy, U.S. forestland increases by approximately 16 Mha by 2050. Management intensification also occurs as a result of both bioenergy expansion and carbon policies. By 2050, planted pine area in the U.S. Southeast region increases from 10 Mha to 11.5 Mha for the bioenergy policy baseline. For the $35 at 5% carbon sequestration payment scenario with bioenergy, pine plantation area expands to more than 14 Mha by 2050.

Table 2 shows how global extensive margin expansion is influenced by the carbon sequestration payment scenarios. Global forest area increases across all scenarios, with an increase of approximately 10 Mha, averaged across all carbon sequestration payment scenarios with the bioenergy policy by 2030. Results show similar levels of forestland expansion by 2050 for combined GHG payment and bioenergy expansion scenarios. By 2090, however, the change in forestland is lower for combined carbon sequestration and bioenergy policy scenarios relative to the no bioenergy scenarios. This change is consistent with the GHG results highlighted in Fig. 2. Intensive margin forest expansion also occurs globally, as some regions see a shift to a larger proportion of accessible forests under both bioenergy and carbon sequestration scenarios, driven by higher pulpwood prices and forestry rents.

Table 2.

Extensive margin expansion in global forest area under alternative policy scenarios relative to the "no policy" baseline in million hectares.

| 1% Growth |

5% Growth |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Bioenergy scenario | $0 | $5 | $20 | $35 | $50 | $0 | $5 | $20 | $35 | $50 |

| 2030 | With Bioenergy Expansion | 11.2 | 36 | 95.9 | 141.9 | 180 | 11.2 | 37.9 | 67.7 | 10 | − 68.5 |

| Without Bioenergy Expansion | 28.6 | 93 | 136.4 | 176.1 | 31.3 | 60.4 | − 9.4 | − 97.7 | |||

| 2050 | With Bioenergy Expansion | 10.2 | 45.9 | 120.8 | 173.7 | 220.8 | 10.2 | 35.2 | − 12.8 | − 28.3 | − 41.5 |

| Without Bioenergy Expansion | 37.3 | 120.2 | 169.9 | 217.1 | 34.3 | − 45.2 | − 60 | − 70.3 | |||

| 2090 | With Bioenergy Expansion | − 20 | 43.9 | 161 | 212.2 | 287.6 | − 20 | − 119.7 | 54.5 | 124.6 | 129.8 |

| Without Bioenergy Expansion | 51.9 | 156.5 | 227.2 | 286.3 | − 113.4 | 40.2 | 121.7 | 158.2 | |||

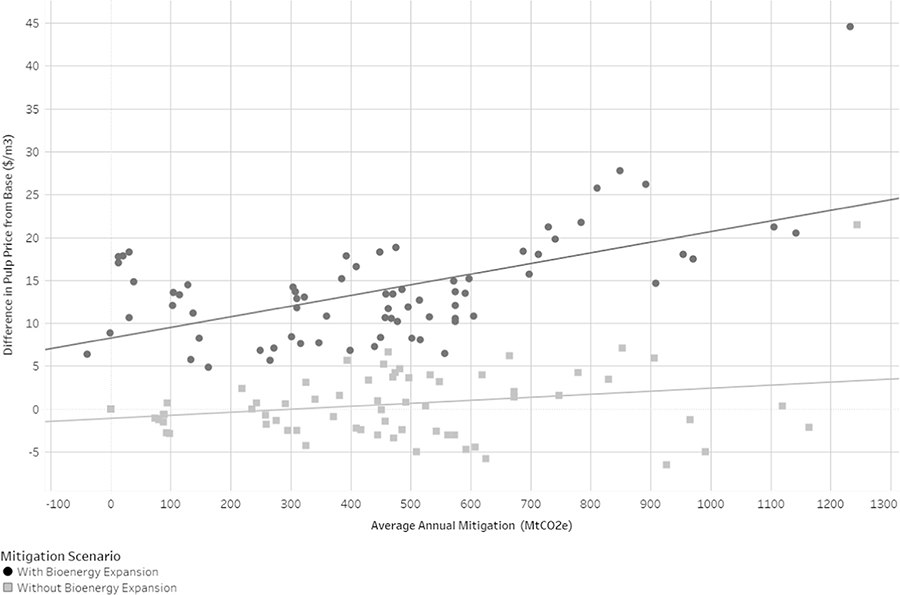

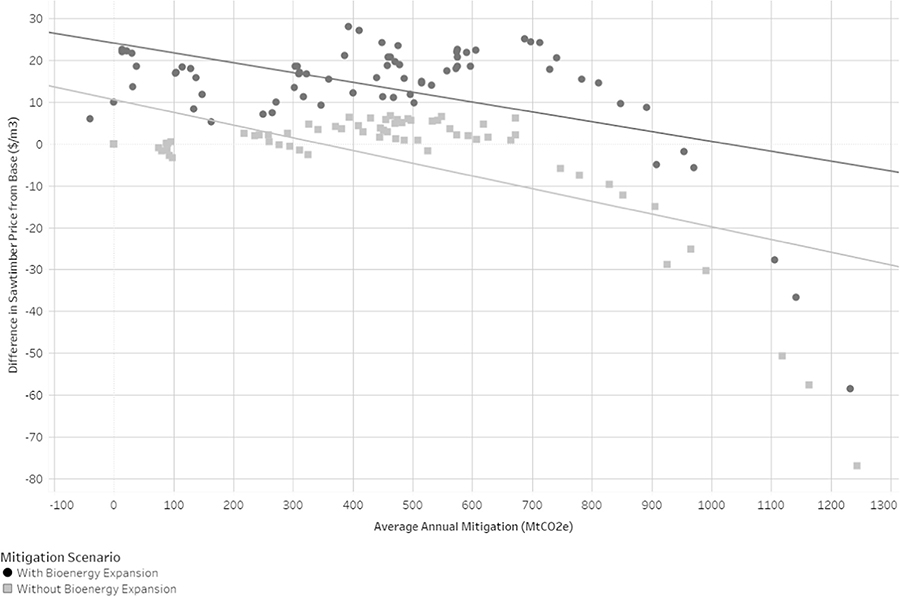

Differences in forest land use and GHG projections can be mostly explained by changes in market conditions and relative prices over time, which are influenced by the exogenous policy incentives. Figs. 3 and 4 provide scatter plots of pulpwood and sawtimber price changes, respectively, relative to the no policy baseline, plotted against annual mitigation totals. To produce these scatter plots, we took annual mitigation levels and price changes, both relative to the no policy baseline, for all carbon sequestration payment scenarios and all simulation periods out to 2100. Scatter plots and trend lines distinguish between scenario output with and without bioenergy.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between pulpwood price changes and average annual mitigation (relative to the "no policy" baseline).

Fig. 4.

Relationship between sawtimber price changes and average annual mitigation potential (relative to the "no policy" baseline).

There are several takeaways from these figures. First, for pulpwood, price changes for carbon policy scenarios with bioenergy are significantly larger than price changes for carbon policy scenarios without bioenergy (also seen in Fig. 1). Furthermore, when bioenergy is included, price changes are positively correlated with net mitigation potential, signaling that an increase in mitigation is costlier in terms of pulp production. When pulpwood demand is lower over time, i.e., for the mitigation scenarios without bioenergy that have lower demand growth for pulpwood, one can generate additional sequestration without increasing the cost of pulpwood.

For sawtimber, bioenergy policies clearly increase prices by 11% across the range of sequestration policy options due to increased forest biomass demand globally. However, increased incentives to sequester carbon increase supply of sawtimber and lower the price. This makes sense given that increased sawtimber rotations will boost both timber supply and carbon supply. Thus, carbon policies are complementary with sawtimber production. At lower levels of mitigation, sawtimber price changes appear to be positively correlated with mitigation outcomes, but at higher mitigation levels (> 0.3 GtCO2e) there is a discernible downward shift, with lower prices corresponding to the highest mitigation outputs and typically for the simulation periods beyond 2050. This is directly related to the structure of the carbon price mechanism, which incentivizes carbon storage in both forest and wood product carbon. At higher mitigation prices (which rise to the end of the century in all scenarios), forest and sawtimber inventories increase, leading to a decline in sawtimber prices relative to the no policy baseline.

While scatter plot figures can be useful in showing general relationships between carbon outcomes and price changes, they ignore the influence of carbon price incentives and temporal dynamics. Therefore, we also construct a regression of projected carbon stocks on key price variables and time to explore how these market forces interact and to establish more meaningful price elasticities on the supply of carbon. While it is uncommon to use regression analysis to synthesize results from modeled projections, we feel that it is appropriate for this analysis given the number of policy scenarios and simulation periods available from this scenario design. Furthermore, regression analysis allows us to explore interactions between different input parameters (carbon prices) and endogenous simulation outputs (pulpwood and sawtimber prices) and how these influence carbon outcomes. Specifically, scenario output data for all scenarios and periods prior to 2100 were used to estimate the following carbon supply function:

This function allows us to examine the relative influence of endogenous market prices, exogenous carbon sequestration price incentives, and time (which captures natural aging of inaccessible forest stands that are not actively harvested) on total carbon stocks. The coefficients on pulpwood, sawtimber, and carbon prices can be interpreted as price elasticities on the supply of total carbon from the global forest sector. All coefficient values are significant at the 5% level or higher with the exception of the pulpwood price coefficient.

Regression results show positive effects for sawtimber and carbon prices, which is intuitive; carbon prices directly incentivize increased carbon sequestration relative to the baseline, so one expects a positive elasticity. Similar logic follows for sawtimber prices. Since mitigation incentives target both terrestrial and wood product carbon storage, this incentive structure increases economic rents from forest stands and the supply sawtimber, hence resulting in a positive relationship between sawtimber prices and carbon stocks. Thus, even though the scatter plot in Fig. 4 shows a slight negative correlation at high mitigation levels, sawtimber price elasticities are positive when controlling for all prices and a general time trend.

However, the full regression equation also shows that when controlling for sawtimber prices, carbon prices, and time, the net effect of pulpwood prices is not statistically distinguishable from zero for all scenarios and simulation periods out to 2100. However, when the regression focuses on later simulation periods (beyond 2050), the sign of the elasticity is negative and significant at the 5% level. Over the long term, an increase in pulpwood prices could reduce total carbon storage without commensurate increases in carbon and sawtimber prices to offset this effect. This result helps explain the switch over time from strong complementarity to weak complementarity and finally to substitutability between bioenergy and carbon sequestration programs. Over time, the demand for pulpwood driven by general demand growth for forest products and the bioenergy policy keeps pulpwood prices more than 50% higher than under the no policy baseline. Higher prices increase competition between pulpwood consumption for products, bioenergy and standing carbon in forests toward the end of the century. Thus, while carbon prices and sawtimber prices jointly improve carbon outcomes on the forest resource base in our simulations, the effect of an increase in pulpwood prices is ambiguous. While an increase in pulpwood prices can lead to near-term investments in the forest resource base and carbon gains, sustained demand growth and higher prices can reduce carbon gains over the long term.

5. Conclusions

This analysis uses a dynamic economic model of the global forest sector to assess potential trade-offs and synergies between forest biomass energy and carbon sequestration programs. Results illustrate how climate and land use policy actions could affect forest management trends, markets, and CO2fluxes, both domestically and internationally. Bioenergy expansion scenarios has a minimal impact on carbon stocks in the near-term and leads to an increase in medium- and long-term carbon storage due to intensive and extensive margin forest expansion in anticipation of increased demand for woody biomass. Mitigation scenarios show significant abatement potential in key forestry regions such as the U.S., parts of South America, and Southeast Asia.

When bioenergy and carbon sequestration payments interact, regional changes in CO2 fluxes indicate potential complementarity between these policy goals for most regions of the world. The near- and medium-term carbon benefits of the combined policies are greater than the mitigation potential implied by the carbon sequestration programs evaluated in isolation. The key policy implication is that designing combined forest biomass and carbon sequestration policies can potentially reduce the overall marginal abatement costs relative to a carbon sequestration program in isolation over the near- and medium-terms (out to mid-century). Bioenergy demand growth increases forest sector investment and economic rents in the near-term to ensure adequate long-term feedstock supply. This shift decreases the relative opportunity costs of additional intensive and extensive market expansion to specifically store additional carbon, so the sector is more responsive to the mitigation price signal.

However, this complementarity dissipates over time, and the policies become substitutes over the long-term, with increased marginal abatement costs of carbon sequestration policies when bioenergy expansion is factored in. Long-term mitigation is thus impacted because the opposing forces of sustained pulpwood demand for bioenergy more directly competes with activities that sequester carbon on the landscape (such as extended rotation lengths and reduced deforestation). With less incentive to invest in new timber resources to meet future demand growth as additional biomass demand tapers off, net mitigation potential begins to decline relative to the carbon sequestration payment scenarios with no bioenergy expansion. This is an important temporal consideration worthy of future policy design analysis. If future anticipated biomass demand expansion increases investment in forest resources and can improve near-term carbon outcomes of sequestration payment incentives but this boost is impermanent, then policy-makers can adjust key policy attributes to account for this lack of sustained benefits. One option could be to discount future mitigation streams using a permanence discount factor to reflect the assumption that near-term benefits of coupled bioenergy and mitigation policies will not be sustained long term. Another option is to design bioenergy policies that result in continued demand growth for woody biomass over the long term. This option could result in sustained investment in timber resources and continued complementarity between these policy efforts.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (Contract EP-BPA-16-H-002, Call Order #EP-B16H-00176). The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily state or reflect those of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

Footnotes

The backward bending supply curves seen in 2030 and 2050 for the 5% price growth scenarios are a function of intertemporal optimization. In this context, mitigation prices are rising a higher growth rate than the internal discount rate assumption used in our modeling framework. When mitigation prices start at a high level in the initial policy period and rise at a rate that exceeds the discount rate, this creates an incentive to delay mitigation action. Hence, marginal abatement cost curves are backward-bending in initial time frames.

References

- Baker JS, McCarl BA, Murray BC, Rose SK, Alig RJ, Adams DM, Latta G, Beach RH, Daigneault A, 2010. Net-farm income and land use under a US greenhouse gas cap and trade. Policy Issues 17. [Google Scholar]

- Baker J, Sohngen B, Ohrel S, Fawcett A, 2017. Economic Analysis of Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Potential in the US Forest Sector. RTI Press, Research Triangle Park, NC: 10.3768/rtipress.2017.pb.0011.1708. (RTI Press Publication No. PB-0011–1708). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigneault A, Sohngen B, Sedjo R, 2012. Economic approach to assess the forest carbon implications of biomass energy. Environ. Sci. Technol 46 (11), 5664–5671. 10.1021/es2030142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M, 2015. The role of the forest in an integrated assessment model of the climate and the economy. Clim. Change Econ 6 (3), 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Favero A, Mendelsohn R, 2014. Using markets for woody biomass energy to sequester carbon in forests. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ 1 (1/2), 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Favero A, Mendelsohn R, Sohngen B, 2017. Using forests for climate mitigation: sequester carbon or produce woody biomass? Clim. Change 10.1007/s10584-017-2034-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galik C, Abt RC, 2016. Sustainability guidelines and forest market response: an assessment of European Union pellet demand in the southeastern United States. Glob. Change Biol.: Bioenergy 8 (3), 658–669. 10.1111/gcbb.12273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haim D, Plantinga AJ, Thomann E, 2014. The optimal time path for carbon abatement and carbon sequestration under uncertainty: the case of stochastic targeted stock. Resour. Energy Econ 36 (2014), 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC, 2014. Climate change 2014: synthesis report In: Team, Pahauri RK, Meyer LA (Eds.), Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on climate Change [Core Writing]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RS, Baker JS, 2010. Opportunities and constraints for forest climate mitigation. Bioscience 60 (9), 698–707. 10.1525/bio.2010.60.9.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Baker JS, Sohngen BL, Shell M, 2018. Cumulative global forest carbon implications of regional bioenergy expansion policies. Resour. Energy Econ 53, 198–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinderman G, Obersteiner M, Sohngen B, Sathaye J, Andrasko K, Rametsteiner E, Schlamadinger B, Wunder S, Beach R, 2008. Global cost estimates of reducing carbon emissions through avoided deforestation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 (30), 10302–10307. 10.1073/pnas.0710616105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraxner F, Aoki K, Leduc S, Kindermann G, Fuss S, Yang J, Yamagata Y, Tak K, Obersteiner M, 2014b. BECCS in South Korea – analyzing the negative emissions potential of bioenergy as a mitigation tool. Renew. Energy 61, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kraxner F, Leduc S, Fuss S, Aoki K, Kindermann G, Yamagata Y, 2014a. Energy resilient solutions for Japan – a BECCS case study. Energy Procedia 61 (2014), 2791–2796. [Google Scholar]

- Kriegler E, Edenhofer O, Reuster L, et al. , 2013. Clim. Change 118, 45 10.1007/s10584-012-0681-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latta GS, Baker JS, Beach RH, McCarl BA, Rose SK, 2013. A multisector intertemporal optimization approach to assess the GHG implications of U.S. forest and agricultural biomass electricity expansion. J. For. Econ 19 (4), 361–383. 10.1016/j.jfe.2013.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lubowski RN, Plantinga AJ, Stavins RN, 2006. Land-use change and carbon sinks: econometric estimation of the carbon sequestration supply function. J. Environ. Econ. Manag 51 (2006), 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn E, Galik C, Tepper D, Myers J, DeMeester J, 2016. Building carbon in America’s farms, forests, and grasslands: foundations for a policy roadmap. For. Trends 67. [Google Scholar]

- Muratori M, Calvin K, Wise M, Kyle P, Edmonds J, 2016. Global economic consequences of deploying bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Environ. Res. Lett 11 (9), 10. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, McCarl, Lee, 2004. Estimating leakage from forest carbon sequestration programs. Land Econ. 80 (1), 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Riahi K, van Vuuren DP, Kriegler E, Edmonds J, O’Neill B, Fujimori S, Bauer N, Calvin K, Dellink R, Fricko O, Lutz W, Popp A, Crespo Cuaresma J, K.C, S.,Leimback M, Jiang L, Kram T, Rao S, Emmerling J, Ebi K, Hasegawa T, Havlik P, Humpenöder F, Da Silva LA, Smith S, Stehfest E, Bosetti V, Eom J, Gernaat D, Masui T, Rogelj J, Strefler J, Drouet L, Krey V, Luderer G, Harmsen M, Takahashi K, Baumstark L, Doelman J, Kainuma M, Klimont Z, Marangoni G, Lotze-Campen H, Obersteiner M, Tabeau A, Tavoni M, 2017. The shared socioeconomic pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153–168. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedjo R, Lyon KS, 1990. The Long Term Adequacy of the World Timber Supply. Resources for the Future, Washington, pp. 230. [Google Scholar]

- Sohngen B, 2008. Paying for avoided deforestation – should we do it? Choices 23 (1). [Google Scholar]

- Sohngen B, Mendelsohn R, 2003. An optimal control model of forest carbon sequestration. Am. J. Agric. Econ 85 (2), 448–457. [Google Scholar]

- Sohngen B, Mendelsohn R, Sedjo R, 1999. Forest management, conservation, and global timber markets. Am. J. Agric. Econ 81 (1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sohngen B, Mendelsogn R, Sedjo R, 2001. A global model of climate change impacts on timber markets. West. Agric. Econ. Assoc 26 (2), 326–343. [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Sohngen B, Baker JS, Ohrel SB, Fawcett A, 2018. Will U.S. forests continue to be a carbon sink? Land Econ. 94 (1), 97–113. 10.3368/le.94.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Sohngen B, Kim JB, Ohrel S, Cole J, 2016. Global climate change impacts on forests and markets. Environ. Res. Lett 11 (3), 035011. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA, 2005. Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Potential in US Forestry and Agriculture (EPA 430-R-05–006). U.S.Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vuuren DP, Deetman S, van Vliet J, van den Berg M, van Ruijven BJ, Koelbl B, 2013. The role of negative CO2 emissions for reaching 2 °C – insights from integrated assessment modeling. Clim. Change 118 (1), 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vuuren DP, Stehfest E, Gernaat DEHJ, Doelman JC, ven den Berg M, Harmsen M, de Boer HS, Bouwman LF, Daioglou V, Edelenbosch OY, Girod B, Kram T, Lassaletta L, Lucas PL, van Meijl H, Müller C, van Ruijven BJ, ven der Sluis S, Tabeau A, 2017. Energy, land-use and greenhouse gas emissions trajectories under a green growth paradigm. Glob. Environ. Change 42 (2017), 237–250. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Winkle C, Baker JS, Lapidus D, Ohrel S, Steller J, Latta G, Birur D, 2017. US Forest Sector Greenhouse Mitigation Potential and Implication for Nationally Determined Contributions. RTI Press, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina: (Occasional Paper No. OP-0033–1705, 24p). [Google Scholar]

- White House, 2016a. United States Mid-Century Strategy for Deep Decarbonization. Washington, DC: Retrieved from: 〈https://unfccc.int/files/focus/long-term_strategies/application/pdf/us_mid_century_strategy.pdf〉. [Google Scholar]

- White House, 2016b. Appendix D: Model Documentation for the Global Timber Model as Applied for the U.S. Mid-Century Strategy for Deep Decarbonization. Washington, DC: Retrieved from: 〈http://unfccc.int/files/focus/long-term_strategies/application/pdf/us_mcs_documentation_and_output.pdf〉. [Google Scholar]