Abstract

Grant-writing and -getting are key to success in many academic disciplines, but research points to gender gaps in both, especially as careers progress. Using a sample of National Institutes of Health (NIH) K-Awardees—Principal Investigators of Mentored Career Development Awards—we examined gender and race effects in responses to imagined negative grant reviews that emphasized either promise or inadequacy. Women translated both forms of feedback into worse NIH priority scores than did men, and showed reduced motivation to reapply for funding following the review highlighting inadequacy. Translation of feedback mediated the effects of gender on motivation, changing one’s research focus, and advice-seeking. Race effects were less consistent, and race did not moderate effects of gender. We suggest that gender bias in grant reviews (i.e., greater likelihood of highlighting inadequacy in reviews of women’s grants), along with gender differences in responsiveness to feedback, may contribute to women’s underrepresentation in academic medicine.

Keywords: gender stereotyping, feedback, motivation, race

The under-representation of women in STEMM fields (science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine) has been a topic of major academic, government, and public concern (see Catalyst, 2018; Kahn & Ginther, 2017; Noonan, 2017). The present research focuses particularly on women’s underrepresentation and outcomes in academic medicine. Although women outnumber men in the biological and biomedical sciences (earning 58.5% of Bachelor’s degrees and 53.2% of Ph.D.s; see National Center for Education Statistics, 2015) and comprise approximately half of medical students in the U.S. (Association of American Medical Colleges, 2015), they remain underrepresented in academic medicine careers. For example, only 44% of Assistant Professors are women, and this percentage decreases as one moves up the academic ranks (women represent 35% of Associate Professors, 22% of Full Professors, and 16% of Department chairs; Association of American Medical Colleges, 2016a; see also Nonnemaker, 2000).

An important criterion for advancement in academic medicine is the ability to secure research support in the form of federal grants, typically from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; see Committee on Bridges to Independence, 2005; Gold, 2017; Hall, Mills, & Lund, 2017). For scientists and physicians launching academic careers, an NIH K award is prized – this is a Mentored Career Development award, designed to pave the way to research independence (see NIH, 2018d). After a K award, the “gold standard” that signals research independence is the NIH R01 grant (NIH, 2018c; see also Gerin & Kapelewski Kinkade, 2018).

Women and men in the biomedical sciences apply for and receive NIH K-Awards at similar rates (Ley & Hamilton, 2008; Poulhaus, Jiang, Wagner, Schaffer, & Pinn, 2011; Rastogi Kalyani, Yeh, Clark, Weisfeldt, Choi, & MacDonald, 2015). However, female applicants are less likely than their male counterparts to receive R01 awards (Eblen, Wagner, RoyChoudhury, Patel, & Pearson, 2016), even if they have previously held a K award. A study of K award recipients from 1997–2003, for example, found that female K awardees were less likely than their male counterparts to have secured R01 funding ten years after their K awards were funded (Jagsi, Motomura, Griffith, Rangarajan, & Ubel, 2009). In another study, women who received K awards in 1999–2000 were less likely than male K awardees to apply for and receive R01 funding in the following 8-year window (Pohlhaus et al., 2011). Pohlhaus et al. (2011) also found that female R01 recipients were less likely to apply for and less likely to obtain renewals of those grants (see also Kaatz, Lee, Potvien, Magua, Filut, Bhattacharya, Leatherberry, Zhu, & Carnes, 2016; Kolehmainen & Carnes, 2018; NIH, 2018e). Women also had fewer concurrent R01 grants than men (Pohlhaus et al., 2011).

The reasons for these gender gaps after the early award period (K award) are unclear. Differential interest in research is unlikely, as K awardees are a select group with an established interest in research careers. But women may still be diverted from interest during or after the K Award period. K awards tend to be smaller for women than men: In 2007, the average K award for women was $145,795, but for men, it was $165,081 (Jagsi et al., 2009), and in a sample of K Awardees during the 2006–2009 window, women were more likely than men to report they had inadequate access to grant administrators and statistical support (Holliday, Griffith, DeCastro, Stewart, Ubel, & Jagsi, 2015). Perhaps this lower support harms research productivity and leaves women less well-placed for an R01 award. Interestingly, Pohlhaus et al. (2011) found that women’s initial R01 awards were larger than men’s ($394,750 versus $384,482), but women re-applied for funding at lower rates. Between 2003 and 2007, 34% of first-time R01 applicants were female (Ley & Hamilton, 2008), and in an analysis of the NIH biomedical database from 2000–2006, women submitted fewer applications overall, and Blacks and women who were new investigators were less likely to resubmit a grant application (Ginther, Kahn, & Schaffer, 2016).

Gender and race differences in grant submission rates have directed attention to two issues: Mentorship (i.e., encouragement and support for resubmission,) and bias in grant reviews (i.e., gender or race-based differences in feedback). Both are highlighted in a report from the NIH’s Advisory Committee to the Director Working Group on Diversity in the Biomedical Research Workforce (NIH WGDBRW, 2012), which was created in response to a highly-cited report of race differences in NIH funding rates (Ginther, Schaffer, Schnell, Masimore, Liu, Haak, & Kington, 2011). Among a number of recommendations, the Advisory Committee called on NIH for, “increased monitoring of the review process to expose disparities in applicant scoring and funding success” as well as “post-review support for minority and underrepresented applicants … [as] researchers from underrepresented groups are more likely to internalize negative comments from reviewers as personal shortcomings, which could deter resubmissions” (NIH WGDBRW, 2012, p. 66). In the present research, we consider both of these points: The possibility of differences in the kinds of feedback female and male biomedical researchers receive on their grant proposals, and the ways in which they interpret and respond to this feedback.

Gender Differences in Grant Reviews

In the present research, we focus on grant reviews and the ways in which these reviews are interpreted by women and men from different racial/ethnic groups. Gender stereotypes suggest that women are less suitable than men for science careers (Miller, Eagly, & Linn, 2015; Moss-Racusin, Dovidio, Brescoll, Graham, & Handelsman, 2012). Is there evidence that such stereotypes may lead to gender bias in grant reviews? Because PI demographic and other information is readily available to reviewers, it is feasible that PI gender may influence judgment of grant quality.

We know of no studies that have found differences in the priority scores assigned to male versus female R01 (Type 1) applicants, but race differences were noted in the 1999–2009 funding window: Applications from Black investigators were less likely to be discussed than those from White investigators (non-discussion indicates the reviewers did not see enough merit to warrant scoring and discussion), and impact scores were worse for Black than White investigators (NIH WGDBRW, 2012; see also Eblen et al., 2016). Gender differences in priority scores were found in a study of R01 renewal grants at the University of Wisconsin; female R01 grantees received worse priority scores on their renewal applications than male grantees (Kaatz, Lee et al., 2016).

Applicant gender effects have been noted with regard to the narrative portions of grant reviews. One study examined the narrative reviews of 67 funded R01 grants at the University of Wisconsin (Kaatz, Magua, Zimmerman, & Carnes, 2015). Perhaps surprisingly, women’s reviews contained more positive words and praise than did men’s while men’s contained more negative evaluation words. However, the fact that these grants received similar scores led the authors to posit that, “gender stereotypes lead reviewers to require more proof of ability from a woman than a man prior to confirming her competence, and greater proof to confirm men’s incompetence in male-typed domains. This may explain why men’s vs. women’s proposals were funded despite more negative critiques” (p. 7).

In the study of renewal applications noted above, women received lower priority scores than men, but more praise in their narrative reviews (positive ability words and “standout” adjectives, such as “outstanding” and “exceptional;” Kaatz, Lee, et al., 2016). This pattern echoes findings in a study of performance evaluations received by female versus male junior attorneys in a Wall Street law firm (Biernat, Tocci, & Williams, 2012). Narrative reviews of female attorneys used more positive performance words than those of male attorneys, but women received lower numerical ratings that mattered for promotion in the firm.

The shifting standards model provides one account of these gender effects on evaluation (Biernat, 2012; Biernat, Manis, & Nelson, 1991). Gender stereotypes about expected competence in academic and work domains may favor men over women, with the result that bottom line judgments—including priority scores and hiring or promotion decisions—are consistent with these stereotyped expectations. At the same time, subjective judgments (adjectival descriptions) are made with reference to group-specific standards of judgment. When a stereotype suggests that women have less of an attribute than men, individual women are judged on that attribute relative to (lower) expectations for women, and men relative to (higher) expectations for men. Thus, a woman may be subjectively described as “better” than a man, but “good” for a woman may mean something objectively less good than “good” for a man. For example, in one study, women were described as more “financially successful” than men, despite the fact that they were also perceived to earn objectively less money than men (Biernat et al., 1991). Furthermore, because of lower competence expectations, women may be held to higher standards than men to prove their competence in a masculine-stereotyped domain (Biernat & Kobyrnowicz, 1997). In domains in which men are stereotyped negatively (e.g., parenting skill), the opposite pattern occurs (Kobrynowicz & Biernat, 1997).

Gender stereotypes may also lead to qualitative differences in narrative commentary offered to women and men. Kaatz, Dattalo, et al., (2016) qualitatively analyzed 34 reviews of 9 unfunded NIH K award proposals solicited from investigators (all of whom eventually received NIH funding) at the University of Wisconsin. The authors conducted a line-by-line analysis of these (de-identified) critiques within the 5 criteria used to evaluate K award applications (quality of the candidate, mentor, research plan, career development plan, and environment and institutional commitment). Codes were iteratively developed and deployed with good inter-rater agreement. Several themes differentiated the reviews received by female and male investigators: 1) in describing the candidate, low productivity was mentioned in a way that “generated doubt about female but not male applicants’ potential for future independence” (Kaatz, Dattalo, et al., 2016, Table 2, p. 81), 2) career development plans were described as “overambitious” for female, but not male, applicants, and 3) criticisms of the research plan focused on perceived deficiencies of female, but not male applicants (e.g., expressed concern about the “abilities” of women versus critiques of the proposed research itself for men).1 These qualitative differences provided the basis for our feedback manipulations, as described below.

Gender Differences in the Interpretation of and Reaction to Feedback

These studies suggest that women and men may receive qualitatively and quantitatively different forms of feedback on their grant proposal submissions. A next question is whether women and men interpret and respond to this feedback differently. In interviews with K Awardees about rejection and resilience, DeCastro and colleagues (2013) found few systematic differences between women and men, but some respondents suggested that “women in particular are more likely to be affected emotionally by rejection or criticism and, thus, are more vulnerable to attributing these types of setbacks to their own failures” (p. 3).

In the broader literature on reactions to feedback, a number of studies have documented gender differences. Roberts and Nolen-Hoeksema (1989) found that women’s self-evaluations were more responsive to feedback (both negative and positive) than men’s, in both hypothetical and actual feedback scenarios. Follow-up research replicated this pattern, and documented that men and women perceived positive and negative feedback on their speech performance similarly, but women viewed the feedback as a more accurate assessment of their abilities than did men (Roberts & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1994). Dweck and colleagues suggest that this greater informational value of feedback for women may be based in developmental experiences in which teachers’ criticisms of girls tend to be ability-based, whereas criticisms of boys often focus on non-intellectual qualities (e.g., poor instruction-following; Dweck, Davidson, Nelson, & Enna, 1978). In a sample of junior high school students, Parsons (Eccles), Adler, and Meece (1984) found that girls were more likely than boys to lower their expectancies for future success following failure feedback on anagrams and math tasks, but performance was not affected and expectations “recovered” after later successes.

Others suggest that women may be more likely than men to perceive praise as “controlling” rather than informative (Deci, 1975); in a masculine domain, however, praise from a male authority may overcome women’s concerns about being judged on the basis of their gender, resulting in positive motivational consequences (Park, Kondrak, Ward, & Streamer, 2018). When feedback is negative, women high in gender-based rejection-sensitivity interpret the feedback more negatively and are less motivated to follow-up by seeking out the evaluator (London, Downey, Romero-Canyas, Rattan, & Tyson, 2012, Study 4; note that this study included only women).

The shifting standards model suggests that when feedback follows performance in a masculine-stereotyped domain, women and men might interpret that feedback differently, with reference to within-group standards (Biernat, 2012). The same subjective feedback—“great job” or “terrible work!”—might be interpreted as objectively less good by women than men because of the assumption that expectations are lower for women’s than men’s performance in the domain. Biernat and Danaher (2012) asked male and female undergraduate participants to role play being the leader of an on-campus leadership organization, and to compose an email to members demonstrating their leadership skills. After receiving mediocre subjective feedback from a peer (“I think your leadership skills are not good [but not super bad either]”), women “translated” that feedback to indicate an objectively worse performance (e.g., that their email would receive a lower letter grade). Confirming gender-typing of the leadership task, women also assumed they were being evaluated relative to lower standards than did men. Furthermore, the importance women, but not men, placed on leadership fell from pre- to post-feedback, and translation of the feedback mediated the gender effect on reductions in leadership importance (Biernat & Danaher, 2012).

Interpreting Grant Proposal Feedback

In the present study, we integrate research pointing to qualitative differences in the kinds of negative narrative grant reviews that women and men receive (Kaatz, Dattalo, et al. 2016) with the shifting standards prediction that feedback may be interpreted with respect to gender-specific standards (Biernat & Danaher, 2012). We asked biomedical researchers with grant-getting experience—NIH K Awardees—to imagine receiving negative narrative feedback on a grant proposal, to “translate” that feedback into NIH priority scoring, and to report their likely responses (interest in grant-writing; motivation to re-apply, seek help, and change research focus).

We created two forms of feedback, mirroring the two patterns identified by Kaatz, Dattalo, et al. (2016) in their qualitative review of grant feedback: 1) feedback highlighting inadequacy, which was more typical of the reviews women received, and 2) feedback highlight the grant writer’s promise, which was more typical of the reviews men received. This allowed us to experimentally examine the consequences for women and men of each type of rejection. Persistence in grant writing is important; one analysis documented that researchers who received NIH R01 grants in 2015 had submitted an average of 5.1 R01 applications in the previous five years (NIH, 2018a). Understanding the extent to which feedback motivates resubmission may be essential for reducing gender and race disparities in funding (see NIH WGDBRW, 2012).

We expected the “promising” version of the negative feedback to be perceived more favorably than the “inadequate” version, but we did not expect a gender difference in these subjective valence perceptions, consistent with the shifting standards model (see Biernat & Danaher, 2012; see also Roberts and Nolan-Hoeksema, 1994). However, we did expect that women would translate each version of the feedback more negatively—tying it to a worse NIH priority score—than men. Although NIH priority scores are not “objective” in the sense of other metrics such as dollars, they are highly meaningful, high impact units: Priority scores indicate likelihood of obtaining funding, a limited zero-sum resource, and the shifting standards model predicts gender effects on such outcomes (Biernat, 2012).

Given the high importance we assumed that K awardees place on grant writing, we did not anticipate that imagined feedback—even of the most negative sort—would reduce the importance women placed on grant writing. However, we anticipated that women, more than men, would show negative downstream consequences of the grant review highlighting inadequacy, including reduced motivation to revise a grant that received such a review. We also predicted that translation of feedback would mediate such gender effects (Biernat & Danaher, 2012).

Given NIH’s recent focus on race differences in funding rates (Ginther et al., 2011, NIH WGDBRW, 2012), we also considered K awardees’ ethnic/racial identity as a factor in our analyses. Ginther et al. (2011) found a Black – White investigator R01 success rate difference that remained after numerous controls. We examine the joint impact of gender and race/ethnicity on interpretations of and reactions to (negative) grant feedback. Are racial/ethnic minorities in general, and women from underrepresented minority groups in particular, likely to interpret feedback negatively? Past research on race and reactions to feedback has pointed to the attributional ambiguity African Americans face when receiving both positive and negative feedback from White majority group members – is the feedback based on the merits/flaws of one’s work or on one’s race? (e.g., Crocker, Voelkl, Testa, & Major, 1991; Hoyt, Aguilar, Kaiser, Blascovich, & Lee, 2007; Major & O’Brien 2005). Biernat and Danaher (2012) also found that African American students interpreted negative feedback about their writing more negatively than did White students. Less is known about how feedback is perceived and experienced by members of other racial/ethnic groups, or by women as compared to men within racial categories. Our primary focus is on gender in this research, but we examine main effects of race/ethnicity as well as interactions between gender and race/ethnicity to test possible intersectional effects (Purdie-Vaughns & Eibach, 2008; Reid & Comas-Diaz, 1990).

Method

Participants

In late 2015, we emailed all then-current biomedical Principal Investigators of NIH K (Mentored Research Career Development) Awards (N=2730). Awardees from three K programs were targeted: K01 - Mentored Research Scientist, K08 - Mentored Clinical Scientist, and K23 - Mentored Patient-Oriented Research. Names and emails were obtained from the NIH access database RePORTER; email addresses not available in RePORTER were identified through web searches by research assistants. The email linked to an online survey that included all manipulations and measures. We were not guided by an a priori power analyses but rather aimed to recruit as many population members as possible. Nonetheless, using an estimated effect size of .20, G*power indicated a total sample size of 390 would be sufficient for power = .95.

Responses were received from 1176 investigators (response rate = 43.1%). Of these, 1067 provided gender and race/ethnicity information, and all analyses reported below focus on this sub-sample. Based on self-identification in the demographic portion of the survey, we separated race/ethnicity into three categories: White non-Hispanic (WNH, n = 415 women and 322 men), Asian/Pacific Islander (Asian, n = 91 women and 80 men), and Other Underrepresented Minority groups (OURM, n = 103 women and 56 men). The OURM group included 80 Hispanic, 54 Black/African American, and 5 Native American respondents, along with 8 who indicated “other”, and 12 who indicated “more than one race.”2

Because we knew the gender of all K-Awardees in our recruitment list, we were able to directly compare the gender distribution in our sample (57.08% women) to the gender distribution in that population (50.03% women): Women are slightly overrepresented and men underrepresented in our sample. We did not have access to race/ethnicity information in our population, but referred instead to NIH statistics about race/ethnicity of K-Award recipients (NIH, 2014). Our sample was 69.08% White/non-Hispanic (very comparable to NIH’s data, 70.64%), 16.03% Asian (18.75% in the NIH data), and 14.90% OURM (10.61% in the NIH data).

Procedure and measures

After consenting, participants first answered three questions assessing pre-feedback importance placed on research and grant writing: “To what extent … is having a successful research career important to you?, … is being able to succeed in obtaining research funds important to you?, and … are your grant writing skills for obtaining research funds important to you?” All answers were made on −1 to 7 (not at all important to very important) rating scales (α=.85). An additional single item assessed self-perceived grant writing ability: “How would you rate your ability for grant writing?” (1–7, very low to very high).

Next, participants were told:

“As a K-Awardee, you are familiar with the experience of writing a grant proposal and receiving feedback from NIH reviewers. We would like you to put yourself back into that situation. Imagine that you have just applied to the NIH for a Mentored Career Development (K) Award. Your proposal has been reviewed and the primary reviewer assigned to your application wrote the following critique of the overall impact of your proposal. As vividly as possible, please imagine receiving this critique of your own proposal, and answer the questions that follow as if you had received this feedback.”

We created two versions of feedback, based on the qualitative analysis by Kaatz, Dattalo, et al. (2016). Both were intended to convey a negative impression of the grant, raising questions about low productivity of the PI, lack of sufficient detail about methods, etc. But in the version we will refer to as “Promising,” we implemented the 3 features identified by Kaatz, Dattalo, et al. (2016) as more typical of reviews received by men: The PI was described as likely to “become an independent researcher,” there was no mention that the proposal was overly ambitious, and criticisms were not focused on deficiencies of the PI (instead, there was concern raised that “the applicant may not have enough protected time for research, or adequate … support”). The feedback version we will refer to as “Inadequate” contained the 3 features found to be more typical of reviews received by women: Questions were raised about the PI’s “ability for independence,” the plan was described as “weak, diffuse, and overly ambitious,” and criticisms focused on deficiencies of the PI (“productivity appears minimal;” there is “concern about the applicant’s abilities to accomplish the proposed research”). The full text of each review version is included in the Appendix. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two feedback conditions.

The two versions of the feedback intentionally differ in a number of ways, including valence, as we aimed to reproduce the features that distinguished reviews of unfunded male and female investigators in Kaatz, Dattalo, et al. (2016). Therefore, any effects of the manipulation cannot be traced to a particular feature of the feedback—i.e., we will be unable to untangle the impact of questioning the PI’s independence, describing the project as overly ambitious, characterizing the PI as deficient, or degree of negativity. Our goal in this study is to examine whether the two overall patterns of feedback are interpreted and experienced differently by women and men.

After reading the feedback and imagining having received it, participants responded to the following set of dependent measures, in the order indicated:

Manipulation check on valence of review.

To check on the perceived valence of the review, participants were asked to what extent they agreed the feedback they received was positive and negative (1 to 7, strongly disagree to strongly agree). Perceived negativity was reverse-scored and the two responses averaged (α = .91).

Translation of review into NIH priority score.

Participants were reminded of NIH scoring and were asked, “what NIH Impact/Priority Score do you think this reviewer would have given your proposal?” Participants were prompted to respond using the 1–9 rating system used by NIH (high values = worse priority score).3

Motivation to re-apply.

Using 1–7 rating scales (not at all to very much), participants responded to six questions: “After receiving this review, I would feel … encouraged to reapply to NIH in the future, … encouraged and immediately begin to revise, … discouraged (reverse scored), … energized, …empowered, … inspired.” Responses were averaged across the 6 items to create a motivation index (α=.87).

Changing research focus.

On the same rating scales, participants also indicated the extent to which, after receiving the grant review, they would “change the focus of my research” and “re-direct my academic career efforts to focus less on research (e.g., clinical work, teaching),” α=.75.

Professional help-seeking.

Participants also indicated the extent to which they would seek the following after receipt of the grant review: “support from peers in my professional working environment,” “advice from senior faculty or mentors,” “advice from my NIH program officer,” “support from friends/family or others outside of my professional working environment,” and “a grant writing course or workshop.” These items were correlated but did not form a reliable scale (α=.59); therefore, these individual help-seeking sources were analyzed in a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA; see below).

Post-feedback importance of grant writing.

To be able to assess any impact of feedback on the importance placed on research and grant-writing, participants re-answered the 3 importance questions described earlier, α=.84, as well as the single item tapping perceived grant writing ability.4

Demographics.

Race and ethnicity were measured at the end of the survey. Participants also indicated whether or not they intended to apply for an NIH R01 grant. All participants said “yes” to this question; therefore we could not include this as an outcome variable.

Results

Overview

For each dependent variable, we conducted Feedback type (promising/inadequate) X Investigator Gender (female, male) X Investigator race (WNH, Asian, OURM) Analyses of Variance (using GLM in SAS). We report all statistically significant effects in the text below (i.e., non-discussed effects were not significant). When interactions were significant, all relevant simple effects were tested using CONTRAST statements in SAS. Correlations among all measures are reported next, followed by analyses examining the role of feedback translation as a mediator of gender effects on other outcomes. Slight variations in degrees of freedom are due to missing data on some variables.

The manipulation check was successful: The Feedback Type X Gender X Race ANOVA on subjective valence indicated a significant main effect of Feedback Type, F(1,1053) = 293.90, p < .0001, partial η2=.16. The promising feedback was perceived more positively (M = 3.77, SD = 1.24) than the inadequate feedback (M = 2.25, SD = 1.21), but still below the midpoint of the rating scale. Thus, the feedback was perceived as intended, and women and men did not differ on this subjective rating.5

Main Analyses

Interpretation of feedback.

Our key dependent variable was the “translation” of the imagined feedback into an NIH score (1–9, with high numbers indicating more negative translations). A Feedback Type (promising, inadequate) X Participant Gender (female, male) X Participant Race (White non-Hispanic [WNH], Asian, other minority [OURM]) ANOVA indicated the expected main effect of feedback type, F(1,1040) = 151.44, p < .0001, partial η2=.13, with promising feedback prompting a better (lower) NIH score (M = 4.93, SD = 1.32) than inadequate feedback (M = 6.33, SD = 1.29). Additionally, consistent with predictions, women (M = 5.72, SD = 1.50) translated the feedback into worse NIH scores than did men (M = 5.48, SD = 1.45), F(1,1040) = 9.82, p = .0018, partial η2=.01. The Feedback X Participant Gender interaction was not significant, F < 1; the tendency for women to translate the feedback more negatively than men held in both the inadequate and promising feedback conditions (ps = .0423 and .0161, respectively).

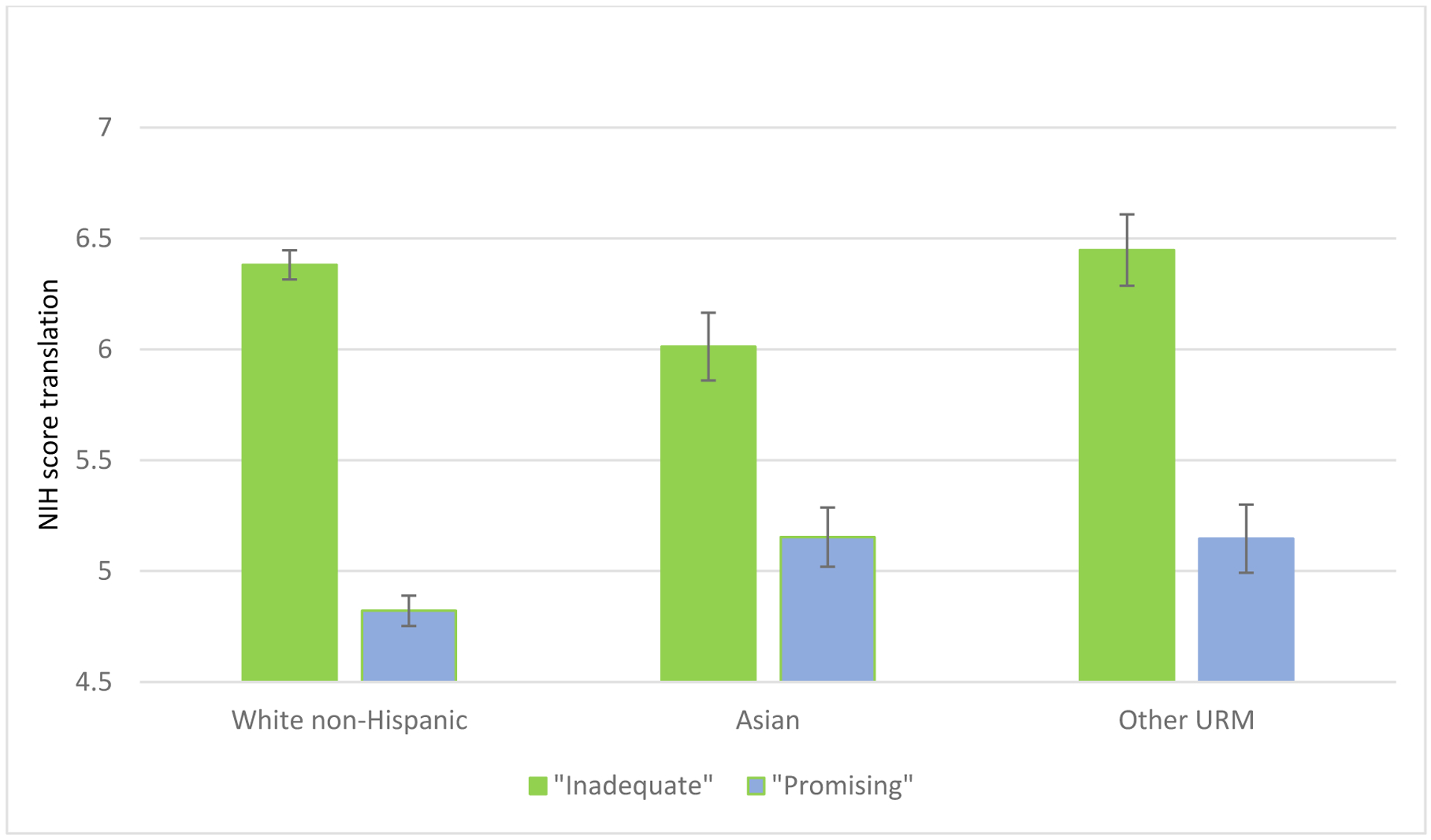

Feedback type did interact with participant race, F(2,1040) = 4.76, p = .0087, partial η2=.01. Promising feedback was translated into a significantly better NIH priority score than inadequate feedback within each racial group (ps < .0001), but as can be seen in Figure 1, Asian participants translated the “inadequate” feedback into a better NIH score than did WNH participants (p = .0249) and other minority participants (p = .0492), who did not differ from each other. WNH participants translated the “promising” feedback most favorably, and significantly more favorably than did Asian participants (p = .0352).6

Figure 1.

Feedback Type X Participant Race effect on NIH score translations

Importance of research/grant writing skill and perceived ability.

Both before and after exposure to the grant feedback, participants indicated the extent to which they viewed grant-writing and -getting as important. The importance indexes were submitted to a Feedback Type X Participant Gender X Participant Race X Timing (pre, post) ANOVA (GLM), with repeated measures on the last factor. There was a significant main effect of timing: Perceived importance dropped from pre-feedback (M = 6.72, SD = .49) to post-feedback (M = 6.66, SD = .56), F(1,1051) = 42.17, p < .0001. The only other effect was a main effect of Participant race, F(2,1051) = 7.38, p = .0007, which held at both pre- and post-measurement (ps < .0012). At each time point, WNH participants rated grant-writing/getting as significantly less important (MT1 = 6.69, SD = .51, MT2 = 6.62, SD = .5) than did Other Underrepresented Minorities (MT1 = 6.83, SD = .40, MT2 = 6.78, SD = .45), and Asian participants (MT1 = 6.78, SD = .47, MT2 = 6.73, SD = .49), ps < .02. Importance was clearly high overall but fell following either kind of feedback (presumably because the feedback was generally negative in both cases; all ps involving feedback type > .20).

A comparable analysis of perceived grant-writing ability produced no significant effects, all ps > .12. In sum, post-feedback importance was lower overall, but unlike Biernat and Danaher (2012), we found no evidence that feedback differentially affected women’s identification with the grant writing domain, and no impact of our experimental procedure at all on perceived ability. This group of K awardees had high confidence in their grant writing ability (M = 5.21 at both time points), and placed great importance on this skill.

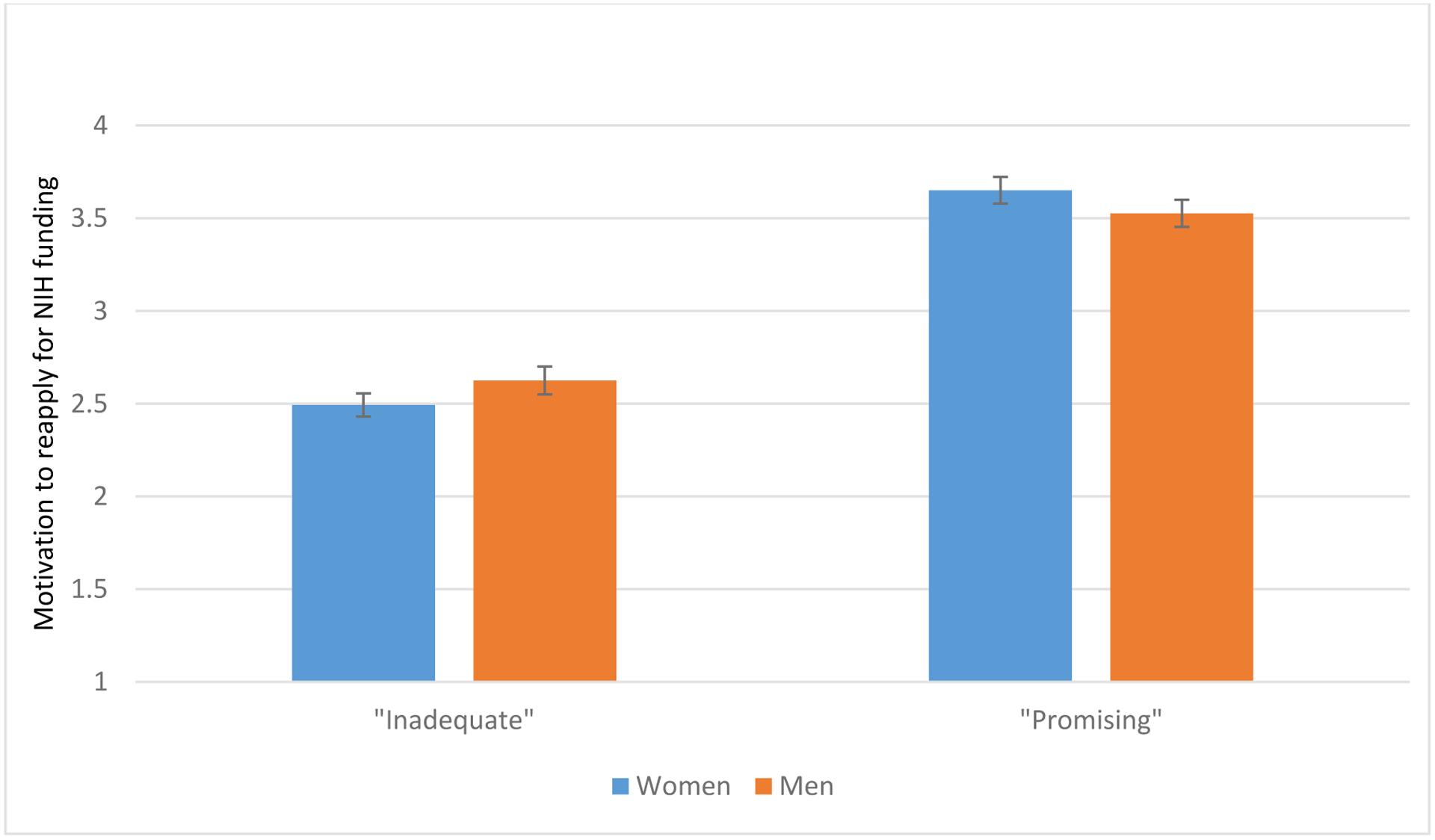

Motivation to reapply for funding.

The main effect of feedback type on motivation to reapply was significant, F(1,1049) = 98.88, p < .0001, partial η2=.09, with higher motivation to reapply following the promising feedback (M = 3.60, SD = 1.20) than the inadequate feedback (M = 2.55, SD = 1.10). This feedback effect was moderated by participant gender, interaction F(1,1049) = 4.33 p = .0376, partial η2=.004. As presented in Figure 2, women generally had more extreme responses to the feedback than men, expressing nonsignifcantly greater motivation to reapply following the “promising” feedback (simple effect p = .3393) and significantly lesser motivation following the “inadequate” feedback (p = .0491). Additionally, the main effect of participant race, F(2,1049) = 4.51, p = .0112, partial η2=.009, indicated that minority respondents (M = 3.39, SD = 1.29) were more motivated to reapply than either Asian (M = 3.05, SD = 1.13) or WNH respondents (M = 3.02, SD = 1.27), ps = .0288 and .0028, respectively, who did not differ from each other (p = .7710).

Figure 2.

Feedback Type X Participant Gender effect on motivation to reapply

Changing research focus.

A different response to grant proposal feedback is to change the focus of or emphasis on one’s research. The change focus index produced two significant main effects: Type of feedback mattered, F(1,1046) = 41.26, p < .0001, partial η2=.04, with more likelihood of changing focus following feedback implying inadequacy (M = 2.95, SD = 1.40) than feedback indicating promise (M = 2.19, SD = 1.23). Additionally, participant race/ethnicity mattered, F(2,1046) = 3.83, p = .0220, partial η2=.007: Asian respondents were more likely to consider changing focus (M = 2.83, SD = 1.32) than other minority (M = 2.38, SD = 1.47) or WNH respondents (M = 2.54, SD = 1.35), ps = .0105, .0170.

Help-seeking.

Participants also indicated the extent to which they would seek help/support following the grant review from professional peers, senior colleagues, NIH program officers, workshops, and friends. These five items were submitted to a Feedback type X Participant Gender X Investigator race MANOVA. The only significant omnibus effect was the main effect of Participant Gender, F(5,1035) = 5.84, p < .0001. Women were more likely to seek help from each source (Ms = 6.02, 6.46, 5.62, 4.93, 4.58, SDs = 1.13, 0.90, 1.58, 1.60, 1.94, respectively) than men (Ms = 5.91, 6.31, 5.44, 4.59, 4.19, SDs = 1.12, 0.95, 1.61, 1.64, 1.85). This gender difference was statistically significant for 3 of the individual items: senior colleagues, workshops, and friends, ps < .02. None of the other omnibus effects were significant, though the Feedback X Participant Gender interaction was suggestive (omnibus p = .1194), and was significant in the case of seeking advice from one’s NIH program officer, F(1,1039) = 4.56, p = .0329. Women (M= 5.46, SD = 1.65) and men (M= 5.40, SD = 1.59) were equally likely to reach out to an NIH officer after receiving the “inadequate” feedback, p = .7956, but women (M= 5.77, SD = 1.49) were more likely than men (M= 5.47, SD = 1.64) to seek NIH officer advice after receiving the “promising” feedback, p = .0050. Women were also more likely to seek NIH advice following “promising” than “inadequate” feedback, p = .0157, but the feedback effects was not significant for men, p = .4529.

Correlational and Mediational Analyses

Table 1 presents the bivariate correlations among key measured variables. Poor translation of the feedback (higher NIH score) predicted less motivation to reapply for funding, increased likelihood of changing one’s research focus, and lower likelihood of seeking advice from one’s NIH program officer. Motivation to reapply also predicted lower likelihood of changing one’s research and greater likelihood of seeking advice; seeking NIH advice predicted less likelihood of changing research focus. To the extent participants viewed grant-writing as important (both at pre-test and post-test), they were more likely to seek advice, and more motivated to reapply for NIH funding.7

Table 1.

Correlations among key outcome variables

| Variable/outcome | Importance-Pre | NIH score | Motivated to reapply | Change focus | Help-seeking: NIH~ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIH score | .03 | ||||

| Motivated to reapply | .07* | −.46** | |||

| Change focus | −.05 | .26** | −.48** | ||

| Help-seeking: NIH~ | .13** | −.10** | .21** | −.22** | |

| Importance-Post | .91** | .04 | .06* | −.06 | .14** |

Notes:

Ns = 1052–1067

This is the individual item regarding seeking advice from one’s NIH program officer.

p < .03

p < .0001

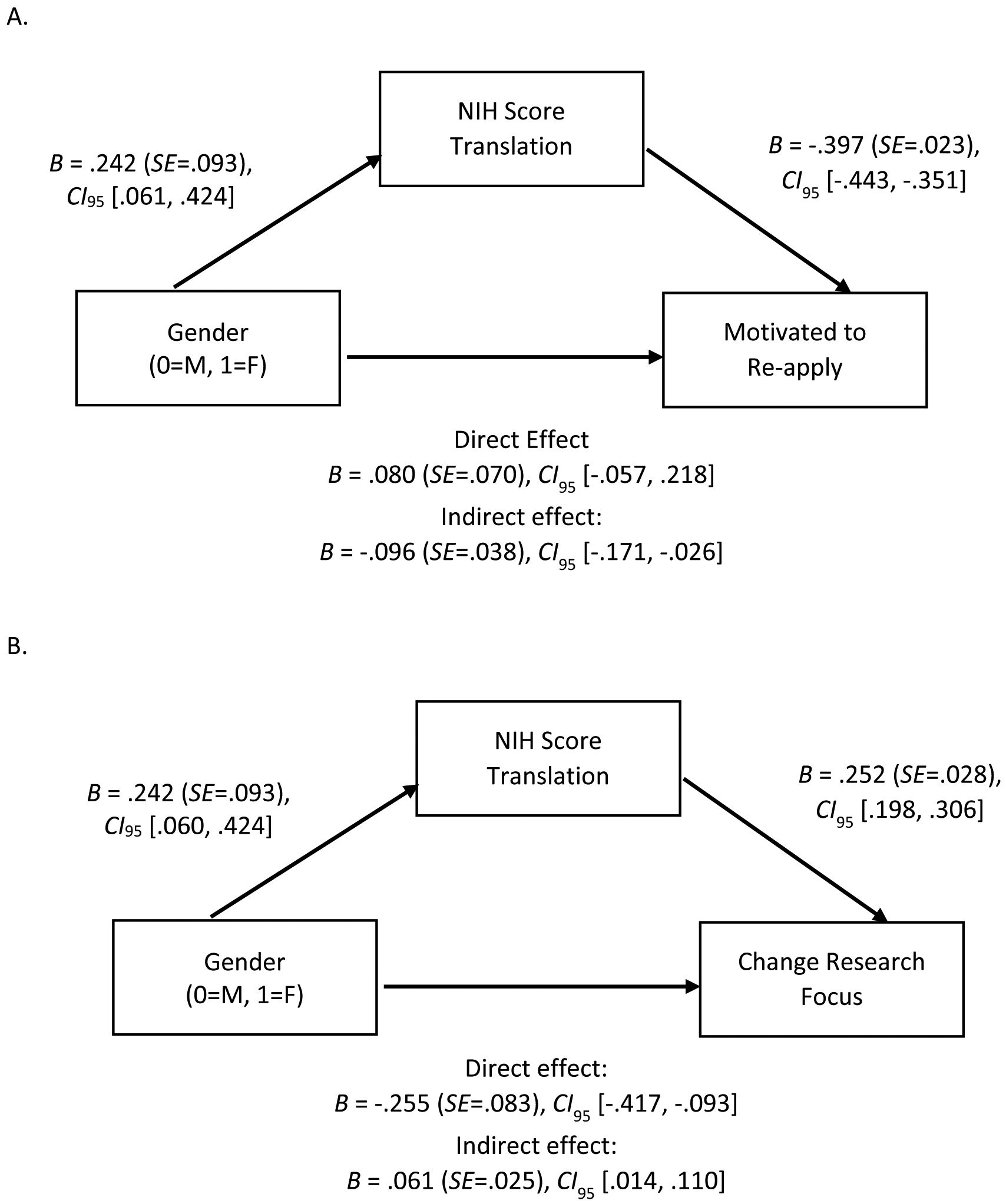

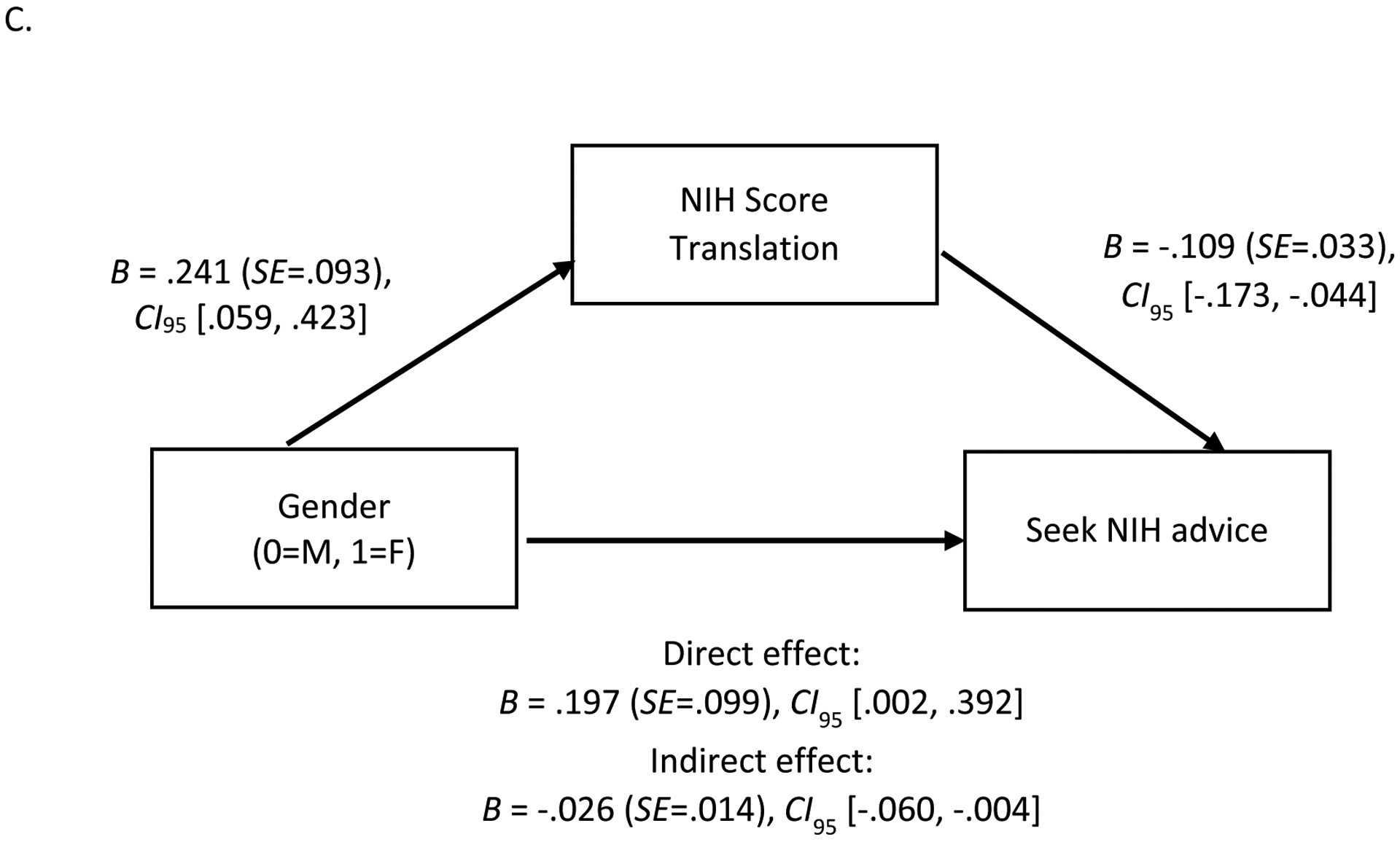

We next examined whether NIH score translation mediated the effect of gender on motivation to re-apply for NIH funding, intent to change research focus, and intent to seek advice from one’s NIH Program Officer. Using PROCESS macros developed by Preacher and Hayes (2008) and Hayes (2013), we examined the simple mediational model depicted in Figure 3 (Model 4 in Hayes, 2013), controlling for race/ethnicity. With regard to motivation to re-apply for funding (Figure 3A), the direct effect of gender was nonsignificant, but the indirect effect of gender, mediated by NIH score, was significant. Women translated grant feedback to indicate a higher (worse) NIH score than men, which in turn predicted lower motivation to re-apply for funding. We also tested whether type of feedback moderated this mediational effect (using Models 7 and 8 in Hayes, 2013), and found no evidence for a moderated mediation pattern. However, the basic mediational model depicted in Figure 3A was significant when we considered only participants exposed to the “inadequate” feedback, indirect effect = −.111, SE = .039, CI95 [−.194, −.039], but not when we considered the “promising” feedback condition, indirect effect = −.042, SE = .033, CI95 [−.113, .021].

Figure 3.

Mediational models: NIH score translation mediates the effect of gender on motivation to re-apply for funding (A), intent to change research focus (B), and intent to seek advice from an NIH Program Officer (C), controlling for race/ethnicity

The mediational analysis predicting intent to change research focus is depicted in Figure 3B. In this case, there was a significant direct effect of gender on intent to change, such that women overall reported less likelihood of changing their research focus than men following feedback. However, the indirect effect of gender on change was significant and positive. Women had greater intent to change their research focus than men to the extent that they translated the grant feedback into a higher (worse) NIH score. Once again, there was no support for moderated mediation, but the indirect effect of gender on intent to change was significant in the “inadequate” feedback condition, indirect effect = .079, SE = .030, CI95 [.027, .144], but not in the “promising” feedback condition, indirect effect = .018, SE = .016, CI95 [−.010, .053].

Finally, the comparable mediational analysis predicting intent to seek advice from an NIH program officer is reported in Figure 3C. The significant direct effect of gender indicates that women were more likely to seek advice than men, but the indirect effect was significant and negative: To the extent that women translated the feedback to indicate a higher (worse) priority score, their help-seeking intent was reduced. Again, the moderated mediation models were nonsignificant, but the indirect effect of gender on intent to seek NIH advice was significant in the “inadequate” feedback condition, indirect effect = −.058, SE = .029, CI95 [−.124, −.010], but not in the “promising” feedback condition, indirect effect = −.006, SE = .011, CI95 [−.033, .010].

Discussion

This research was motivated by concerns about women’s underrepresentation in academic medicine and lower likelihood of applying for and receiving NIH funding after the early (K Award) period (Pohlhaus et al., 2011; Ginther et al., 2016). To speak to these concerns, we drew on two literatures: One documenting differences in the kinds of reviews women versus men receive on their unfunded grants (women’s reviews highlight inadequacy, men’s highlight promise; Kaatz, Dattalo, et al., 2016), and another documenting gender differences in reactions to feedback (e.g., Biernat & Danaher, 2012; Roberts & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1989, 1994). Do women “translate” reviews more negatively than men, and does this negative translation predict reduced motivation to reapply for funding? In a sample of experienced grant-getters—K Awardees—we examined how women and men from different racial/ethnic groups interpreted and reacted to a negative narrative grant review that emphasized “promise” versus “inadequacy.”

Based on the shifting standards model (Biernat, 2012; Biernat & Danaher, 2012), we predicted that women would translate each form of narrative feedback to indicate a worse NIH priority score than men. Gender stereotypes that devalue women’s performance may lead both women and men to interpret the subjective language of reviews relative to within-gender standards. For a woman in this context, any given narrative review may therefore mean something objectively less good than it would for a man. We found strong support for this prediction—women perceived that the grant review they imagined translated into a higher (worse) NIH priority score than did men. Women and men agreed that the review emphasizing inadequacy was subjectively less good than the review emphasizing promise, but in each case, women translated the review into a worse “objective” score. We did not indicate the gender of the imagined reviewer, but given that study sections are generally comprised of NIH R01-funded investigators, and this group includes only 29% women (NIH, 2018f), it is possible that participants assumed the reviewer was a man. Further research is needed to determine whether the gender of the reviewer may moderate the gender-based translation effect.

We made no clear predictions regarding race/ethnicity, but we found that Asian respondents made the most favorable translation of the inadequate feedback, compared to White non-Hispanic and other underrepresented minority respondents, but translated the promising feedback less favorably than did Whites. Another interpretation of this pattern is that Asian respondents distinguished less between the promising and inadequate feedback than did the other groups (Whites distinguished most). We have no clear explanation for these patterns. Stereotypes about competence in research may favor Asians to some extent (e.g., smart and hardworking), but this group may also be seen as less capable in leadership roles (Zhang et al., 2017) and is underrepresented in academic medicine more generally (Association of American Medical Colleges [AAMC], 2016b; Jeffe, Yan, & Andriole, 2012). Further research will be needed to replicate and better understand racial/ethnic differences in translation of feedback.

We also examined other potential consequences of exposure to negative grant reviews, including reduced importance placed on grant-writing, reduced motivation to reapply, increased likelihood of changing one’s research focus, and reduced help-seeking. In their study of gender differences in responsiveness to negative leadership feedback, Biernat and Danaher (2012) found that women, but not men, reduced the importance placed on leadership. We did not expect to conceptually replicate this effect in the present study, given our sample’s demonstrated commitment to and success at grant writing. Pre-feedback, women and men reported importance of grant writing at a level near the scale ceiling (6.72 on a 7-point scale), and while this fell slightly post-feedback (to 6.66), gender did not moderate this pattern. Perceived ability to write grants did not differ by gender, or by feedback, or across the two time points of measurement. In this sense, the sample showed strong resilience in the face of the imagined feedback.

However, gender differences did emerge in motivation to reapply to NIH for funding; resubmission is a point at which gender differences in NIH funding have been noted (see Ginther et al., 2016; Pohlhaus et al., 2011). Women were significantly less motivated to reapply for funding than men following exposure to the grant review highlighting inadequacy of the researcher (the feedback pattern more typical of women in Kaatz, Dattalo, et al.’s, 2016, analysis). Following “promising” feedback, women showed nonsignificantly more motivation to reapply. This pattern is consistent with past research suggesting that women are more responsive to feedback than men (Roberts & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1994; see also Dweck et al., 1978). In this case, however, the feedback was always negative, but its qualitative framing varied and mattered for motivation. Similarly, the type of feedback mattered for whether women responded by seeking advice from an NIH officer: When the grant review mentioned “promise,” women were more likely than men to turn for advice to their NIH Program Officer. Seeking such advice is a highly recommended course of action (see NIH, 2018b; Steinberg, 2004).

Highlighting “promise” rather than inadequacy may be an example of “wise” feedback that reduces group-based discrepancies (Cohen, Steele, & Ross, 1999, Steele 2010, Yeager et al. 2014). The “wise feedback” approach, first described by Cohen et al. (1999) as a means of bridging racial divides, involves delivering negative feedback in a way that a) emphasizes the use of high standards and b) assures the target that s/he is capable of meeting those standards. In their research, “wise” feedback reduced differences between Black and White students in perceptions of bias, motivation, and domain importance relative to “unbuffered” criticism, criticism buffered by praise, and criticism along with mention of high standards only (Cohen et al., 1999). A negative grant review that nonetheless describes the PI as promising may prove a “wise” mechanism for reducing gender differences in grant resubmission rates.

Consistent with the shifting standards model, this research also points to the importance of the translation of narrative feedback for motivation and resilience. The interpretation of narrative feedback as indicative of a higher (worse) priority score predicted reduced motivation to reapply for funding, increased likelihood of changing one’s research focus, and reduced intent to seek advice from an NIH program officer. Furthermore, this translation mediated gender effects on these outcomes: To the extent that women translated grant reviews negatively—particularly when the review suggested inadequacy—their motivation to reapply and help-seeking was reduced, and their intent to change their research focus increased.

Of course, narrative reviews of NIH grants generally include priority scores, and in this sense there is no need for recipients to “translate” the feedback in the manner we asked our participants to do. But roughly half of all submissions at NIH are “not discussed” and receive no priority score (NIH Center for Scientific Review, 2018), and in these cases, some “translation” of narrative comments is needed. Women are generally stereotyped as less suitable for science careers than men (Miller et al., 2015; Moss-Racusin et al., 2012) and women in academic medicine report high vulnerability to stereotype threat (e.g., “I feel that people in academic medicine judge me negatively because of what they think of (my gender) as a group;” Fassiotto et al., 2016, p. 294). These stereotypes facilitate gender differences in the interpretation of feedback; “low quality” means something objectively less good to a woman than a man (Biernat & Danaher, 2012). Though our moderated mediation analyses were not significant, it was the case that the mediational effects described in Figure 3 were particularly striking in the inadequate feedback condition. The extent to which reviewers offer qualitatively different feedback to women than men may exacerbate the tendency for women to interpret the reviews they receive more negatively than do men.

We found no evidence that race/ethnicity moderated the gender effects we observed: None of the outcome variables we measured showed statistical interactions between gender and race. Instead, a number of main effects of race provided evidence of resilience in the respondents we classified as other underrepresented minorities (Black, Hispanic, Native American and others). These OURM K-Awardees (along with Asians) placed greater importance on grant-writing than did White non-Hispanic K-Awardees; they also subjectively viewed the feedback most positively and reported higher motivation to reapply for funding after than either Asian or non-Hispanic White K-Awardees. Additionally, they were as unlikely to change their research focus after the negative feedback as White non-Hispanic respondents; Asian respondents were most inclined to do so. These findings are encouraging, especially in light of concern about Black researchers’ application and funding rates (Ginther et al., 2011, NIH WGDBRW, 2012). But K-Awardees, like our research sample, are predominantly White. This limits our power to detect interaction effects involving race and our ability to offer a more nuanced analysis of race effects; more research is clearly needed.

K-Awardees in general—and ethnic/racial minority K-Awardees in particular—are an elite group. They are successful grant-getters, highly committed to research and grant-getting. It is therefore especially concerning that women in this group interpreted feedback more negatively and showed reduced motivation to reapply following reviews that highlighted inadequacy. We suspect our findings underestimate the effects of feedback and the role of gender that might be found in a less experienced group of researchers, earlier in the process of considering careers in academic medicine. Grant reviewers, study section members, and scientific review officers should be made aware of possible subtle bias in the tone of reviews, and should incorporate the “wise” feedback approach (Cohen et al., 1999).

Of course our study is limited by the use of a hypothetical scenario, in which participants imagined receiving feedback on a grant application. The two types of feedback also differed in a number of ways, making it difficult to know which precise phrasing or emphasis in the reviews was responsible for our effects. The promising feedback was more positive overall than the inadequate feedback, and it was lengthier; additional studies will be needed to pinpoint whether negativity per se, or particular criticisms (e.g., lack of independence), or shorter length, are most problematic. We also did not include a truly positive feedback condition, in which one’s grant is funded, or a more ambiguous review. These were of less interest in the present study as we aimed to model a typical case of feedback on an unfunded proposal. But such conditions could provide additional points of comparison against which to examine how gender and race affect interpretations of and reactions to feedback.

Our study was also limited by the response rate of 43.1%, as well as the overrepresentation of women and underrepresentation of men relative to their rates in our population of K-Awardees. Still, this response rate is higher than is typical of on-line/email-delivered surveys (around 30%; see Lindemann, 2018), and women are generally more likely to respond to survey requests than men (e.g., Smith, 2008). Our analyses were based on a fairly large sample of K award recipients, and men remained well-represented in the sample. Nonetheless, additional research is clearly warranted, using new samples of K- and other awardees.

Grant writers receive many different kinds of reviews, and cognitive and motivational responses to each may differ in myriad ways. This variability makes it difficult to pinpoint the effects of feedback in real world settings. The experimental approach we used here is valuable in its ability to equate feedback and examine gender differences in responses, and we encourage additional research in this vein. But what is also needed are studies that track researchers through the process of actually receiving and responding to reviews of their own grant proposals and other academic work. Such research could shed more light on the processes by which feedback is translated, and the consequences of this translation for motivation and persistence.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Text of the two feedback versions:

Promising

This application for a Mentored Career Development Award has a few strengths but some weaknesses limit the proposal’s potential impact. Notably, productivity is not overwhelming for someone seeking this level of support, though it does show some publication skills. Productivity also should improve over the K award period. The Career Development Plan proposes important activities but is somewhat unclear. A timeline, and additional details about training activities and the role of mentors should be included. The proposed research is in an important area and has potential to yield significant scientific contributions. However, techniques, that the applicant has likely mastered, are not described in sufficient detail and need to be elaborated. Although the environment is adequate, there is concern that the applicant may not have enough protected time for research, or adequate technical, statistical, and administrative support. Description of these issues needs to be expanded, and the commitment to the applicant beyond the K award period needs to be clarified. The primary mentor is an accomplished investigator and appears committed to the success of the applicant, but it is unclear how mentoring will be carried out. While the application is well written and reasonably innovative, it is limited in several ways that may undermine the preparation of this appealing applicant to become an independent investigator.

Inadequate

This application for a Mentored Career Development Award has a few strengths but multiple major weaknesses significantly limit the proposal’s potential impact. Notably, productivity appears minimal for someone seeking this level of support and raises concern about ability for independence. The Career Development Plan includes important activities but is relatively weak, diffuse, and overly ambitious. The proposed research is in an important area. However, there is considerable concern about the approach, which is vague and lacks compelling preliminary data. There is concern about the applicant’s abilities to accomplish the proposed research. Although the environment is adequate, insufficient detail is provided about what resources will be specifically committed to the applicant. The primary mentor is an accomplished investigator and appears committed to the success of the applicant, but it is unclear how mentoring will be carried out. While the application is well written and reasonably innovative, it is limited in several ways that raise doubt about the candidate’s ability for an independent research career.

Footnotes

1 There were no differences in the narrative comments male and female investigators received about the mentor or environment/institutional support.

2We recognize that the OURM grouping collapses over important distinctions among racial/ethnic groups. However, low N restricts our ability to conduct more nuanced analyses.

3 We also asked participants to indicate what letter grade, from A – F, the reviewer would have given their proposal. Only a main effect of feedback emerged on this variable, with the “promising” feedback M = 2.85 (on a 1–5 scale, about a B-), and the “inadequate” feedback M = 3.55 (about a C). In our main analyses, we focus on the NIH priority score translation as this is the most meaningful metric in this context.

4 After these questions, several additional measures designed to tap K Awardees’ perceptions of their own (actual) grant-writing experience were included. These included recommendations for what would be useful to receive from grant panels, the extent to which participants understood various sections of the grant proposal, and perceptions of their mentors. These questions were included for other purposes, and were unaffected by the manipulation of imagined feedback; they will not be discussed further. In the main part of the survey, we included a few additional items tapping negative mood following the feedback (e.g., anger, anxiety, sadness). Because these were less theoretically relevant, and because they do not shed additional light on the research questions beyond what is reported in the text, they will not be discussed in detail. In general, inadequate feedback led to less positive mood than promising feedback, but this did not interact with gender or race. The authors can be contacted for full details.

5 Independent of the feedback effect was a significant main effect of participant race, F(2,1053) = 8.05, p = .0003, partial η2=.015. Collapsed across feedback type, minority participants viewed the feedback more positively (M = 3.35, SD = 1.51) than did Asian (M = 2.97, SD = 1.40) or WNH participants (M = 2.95, SD = 1.42).

6 The 3-way interaction was marginally significant, p < .07. The gender difference in translation generally held in each race/feedback condition but was largest among OURM participants who received promising feedback.

7 We also examined correlations with the other four help-seeking items. NIH score translation was uncorrelated with seeking help from senior colleagues (r = .003, p =.9191) or peers (r = .04, p = .1791), but was correlated with seeking friends (r = .11, p = .0006) and taking a grant workshop (r = .12, p = .0001). Each help-seeking item was also positively correlated with motivation to re-apply (rs from .07 - .14, ps < .04), with the exception of seeking friends; high motivation was associated with less help-seeking from friends, r = −.14, p < .0001. We found no evidence, however, that NIH score translation mediated the effects of gender on these other help-seeking items, in either feedback condition.

Contributor Information

Monica Biernat, University of Kansas.

Molly Carnes, University of Wisconsin.

Amarette Filut, University of Wisconsin.

Anna Kaatz, University of Wisconsin.

References

- Association of American Medical Colleges (2016a). The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2015–2016. Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/

- Association of American Medical Colleges. (2016b). Table A-9. Matriculants to U.S. medical schools by race, selected combinations of race/ethnicity and sex, 2013–2014 through 2016–2017. Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/download/321474/data/factstablea9.pdf

- Association of American Medical Colleges (2015). Table 1: Medical students, selected years, 1965–2015. Retrieved from: https://www.aamc.org/download/481178/data/2015table1.pdf

- Biernat M (2012). Stereotypes and shifting standards: Forming, communicating, and translating person impressions In Devine P, & Plant A (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology, vol 45; advances in experimental social psychology, vol 45 (pp. 1–59, Chapter vii, 350 Pages) Academic Press, San Diego, CA. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394286-9.00001-9 Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394286-9.00001-9https://search.proquest.com/docview/1033448075?accountid=14556 Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1033448075?accountid=14556 [Google Scholar]

- Biernat M, & Danaher K (2012). Interpreting and reacting to feedback in stereotype-relevant performance domains. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biernat M, & Kobrynowicz D (1997). Gender- and race-based standards of competence: Lower minimum standards but higher ability standards for devalued groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(3), 544–557. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.3.544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernat M, Manis M, & Nelson TE (1991). Stereotypes and standards of judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 485–499. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biernat M, Tocci MJ, & Williams JC (2012). The language of performance evaluations: Gender-based shifts in content and consistency of judgment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(2), 186–192. doi: 10.1177/1948550611415693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catalyst (2018). Quick take: Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM). Retrieved from http://www.catalyst.org/knowledge/women-science-technology-engineering-and-mathematics-stem.

- Cohen GL, Steele CM, & Ross LD (1999). The mentor’s dilemma: Providing critical feedback across the racial divide. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(10), 1302–1318. doi: 10.1177/0146167299258011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Bridges to Independence, Board on Life Sciences, National Research Council of the National Academies (2005). Bridges to independence: Fostering the independence of new investigators in biomedical research. Washington, DC: The National Research Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Voelkl K, Testa M, & Major B (1991). Social stigma: The affective consequences of attributional ambiguity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 218–228. doi:http://dx.doi.org.www2.lib.ku.edu/10.1037/0022-3514.60.2.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCastro R, Sambuco D, Ubel PA, Stewart A, & Jagsiand R (2013). Batting 300 is good: Perspectives of faculty researchers and their mentors on rejection, resilience, and persistence in academic medical careers. Academic Medicine, 88, 1–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318285f3c0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL (1975). Intrinsic motivation Plenum Press, New York, NY. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-4446-9 Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-4446-9https://search.proquest.com/docview/616056796?accountid=14556 Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/616056796?accountid=14556 [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS, Davidson W, Nelson S, & Enna B (1978). Sex differences in learned helplessness: II. the contingencies of evaluative feedback in the classroom and III. an experimental analysis. Developmental Psychology, 14(3), 268–276. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.14.3.268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eblen MK, Wagner RW, RoyChoudhury D, Patel KC, & Pearson K (2016). How criterion scores predict the overall impact score and funding outcomes for National Institutes of Health peer-reviewed applications. PLoS One, 11(6), e0155060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassiotto M, Hamel EO, Ku M, Correll S, Grewal D, Lavori P, Periyakoil VJ, Reiss A, Sandborg C, Walton G, Winkleby M, & Valantine H (2016). Women in academic medicine: Measuring stereotype threat among junior faculty. Journal of Women’s Health, 25(3), 292–298. 10.1089/jwh.2015.5380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerin W, & Kapelewski Kinkade C (2018). Writing the NIH grant proposal: A step-by-step guide. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ginther DK, Kahn S, & Schaffer WT (2016). Gender, race/ethnicity, and National Institutes of Health R01 Research Awards: Is there evidence of a double bind for women of color? Academic Medicine, 9, 1098–1107. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, Masimore B, Liu F, Haak LL, & Kington R (2011). Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science, 333, 1015–1019. doi: 10.1126/science.1196783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold KJ (2017). The allure of tenure. Academic Medicine, 92, 1371–1372. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall AK, Mills SL, & Lund PK (2017). Clinician-investigator training and the need to pilot new approaches to recruiting and retaining this workforce. Academic Medicine, 92, 1382–1389. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday E, Griffith KA, De Castro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, & Jagsi R (2015). Gender differences in resources and negotiation among highly motivated physician-scientists. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30, 401–407. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2988-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt CL, Aguilar L, Kaiser CR, Blascovich J, & Lee K (2007). The self-protective and undermining effects of attributional ambiguity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(6), 884–893. doi:http://dx.doi.org.www2.lib.ku.edu/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.10.013 [Google Scholar]

- Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, & Ubel PA (2009).Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151, 804–811. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffe DB, Yan Y, & Andriole DA (2012). Do research activities during college, medical school, and residency mediate racial/ethnic disparities in full-time faculty appointments at U.S. Medical schools? Academic Medicine, 87, 1582–1593. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0148-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaatz A, Dattalo M, Regner C, Filut A, & Carnes M (2016). Patterns of feedback on the bridge to independence: A qualitative thematic analysis of NIH Mentored Career Development Award application critiques. Journal of Women’s Health, 25, 78–90. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaatz A, Lee Y-G, Potvien A, Magua W, Filut A, Bhattacharya A, Leatherberry R, Zhu X, & Carnes M (2016). Analysis of NIH R01 Application Critiques, Impact and Criteria Scores: Does the Sex of the Principal Investigator Make a Difference? Academic Medicine, 91, 1080–1088. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaatz A, Magua W, Zimmerman DR, & Carnes M (2015). A quantitative linguistic analysis of National Institutes of Health R01 application critiques from investigators at one institution. Academic Medicine, 90, 69–75. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn S, & Ginther D (2017, June). Women and STEM. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 23525. doi: 10.3386/w23525 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobrynowicz D, & Biernat M (1997). Decoding subjective evaluations: How stereotypes provide shifting standards. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 579–601. doi:http://dx.doi.org.www2.lib.ku.edu/10.1006/jesp.1997.1338 [Google Scholar]

- Kolehmainen C, & Carnes C (2018). Who resembles a scientific leader—Jack or Jill? How implicit bias could influence research grant funding. Circulation, 137, 769–770. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley TJ, & Hamilton BH (2008). The gender gap in NIH grant applications. Science, 322, 1472–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.1165878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann N (2018). What’s the average survey response rate? (2018 benchmark). Retrieved from: https://surveyanyplace.com/average-survey-response-rate

- London B, Downey G, Romero-Canyas R, Rattan A, & Tyson D (2012). Gender-based rejection sensitivity and academic self-silencing in women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(5), 961–979. doi: 10.1037/a0026615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, & O’Brien LT (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393–421. doi:http://dx.doi.org.www2.lib.ku.edu/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DI, Eagly AH, & Linn MC (2015). Women’s representation in science predicts national gender-science stereotypes: Evidence from 66 nations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3), 631–644. doi: 10.1037/edu0000005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moss-Racusin C, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, & Handelsman J (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(41), 16474–16479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211286109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics (2015). Table 318.30: Bachelor’s, Master’s, and Doctor’s Degrees conferred by postsecondary Institutions, by sex of student and discipline division: 2013–14. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_318.30.asp [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health (2018a). Applicant guidance: Next steps “Your application was reviewed; what to do next…” Retrieved from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/next_steps.htm

- National Institutes of Health (2018b). Contacting staff at the NIH institutes and centers. Retrieved from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/how-to-apply-application-guide/resources/contacting-nih-staff.htm

- National Institutes of Health (2018c). NIH research project grant program (R01). Retrieved from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/r01.htm

- National Institutes of Health (2014). Physician-Scientist workforce (PSW) report 2014. Retrieved form https://report.nih.gov/Workforce/PSW/appendix_iv_a1_3.aspx

- National Institutes of Health (2018d). Research career development awards. Retrieved from https://researchtraining.nih.gov/programs/career-development

- National Institutes of Health (2018e). R01-equivalent grants: Success rates, by gender and type of application. Retrieved from http://report.nih.gov/NIHDatabook/Charts/Default.aspx?showm=Y&chartId=178&catId=15 [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health (2018f). R01-equivalent grants: Awards, by gender. Retrieved from https://report.nih.gov/nihdatabook/index.aspx

- NIH Center for Scientific Review (2018). What happens to your application during and after review? Retreived from https://public.csr.nih.gov/ApplicantResources/InitialReviewResultsAppeals/Pages/What-happens-to-your-application-during-and-after-review.aspx

- NIH Working Group on Diversity in the Biomedical Research Workforce (NIH WGDBRW) (2012). Draft Report of the Advisory Committee to the Director Working Group on Diversity in the Biomedical Research Workforce. Retrieved from http://acd.od.nih.gov/Diversity%20in%20the%20Biomedical%20Research%20Workforce%20Report.pdf

- Nonnemaker L (2000). Women physicians in academic medicine: New insights from cohort studies. New England Journal of Medicine, 342, 399–405. doi: 10.1056/DNEJM200002103420606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan R (2017, November 13). Women in STEM: 2017 update (Economics and Statistics Administration Issue Brief #06–17). Retrieved from https://www.esa.gov/reports/women-stem-2017-update. [Google Scholar]

- Park LE, Kondrak CL, Ward DE, & Streamer L (2018). Positive feedback from male authority figures boosts women’s math outcomes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44, 359–383. doi: 10.1177/0146167217741312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons (Eccles) JE, Adler T, & Meece JL (1984). Sex differences in achievement: A test of alternate theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(1), 26–43. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.1.26 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlhaus JR, Jiang H, Wagner RM, Schaffer WT, & Pinn VW (2011). Sex differences in application, success, and funding rates for NIH extramural programs. Academic Medicine, 86, 759–767. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821836ff [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdie-Vaughns V, & Eibach RP (2008). Intersectional invisibility: The distinctive advantages and disadvantages of multiple subordinate-group identities. Sex Roles, 59, 377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi Kalyani R, Yeh H-C, Clark JM, Weisfeldt ML, Choi T, & MacDonald SM (2015). Sex differences among Career Development Awardees in the attainment of independent research funding in a department of medicine. Journal of Women’s Health, 24, 933–941. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid PT, & Comas-Diaz L (1990). Gender and ethnicity: Perspectives on dual status, Sex Roles, 22, 397–408. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts T, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (1994). Gender comparisons in responsiveness to others’ evaluations in achievement settings. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18(2), 221–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00452.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts T, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (1989). Sex differences in reactions to evaluative feedback. Sex Roles, 21(11–12), 725–747. doi: 10.1007/BF00289805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G (2008). Does gender influence only survey participation? A record-linkage analysis of university faculty online survey response behavior.” ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 501717.

- Steele CM (2010). Whistling vivaldi: How stereotypes affect us and what we can do W W Norton & Co, New York, NY: Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/867315643?accountid=14556 [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg J (2004). Obtaining a research grant: The granting agency’s view In Darley JM, Zanna MP, & Roediger HL III (Eds.), The compleat academic: A career guide (2nd ed, pp. 153–168). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Purdie-Vaughns V, Garcia J, Apfel N, Brzustoski P, Master A, Hessert WT, Williams ME, & Cohen GL (2014). Breaking the cycle of mistrust: Wise interventions to provide critical feedback across the racial divide. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(2), 804–824. doi: 10.1037/a00339062014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lee ES, Kenworthy CA, Chiang S, Holaday L, Spencer DJ, Poll-Hunter NI, & Sánchez JP (2017/in press). Southeast and East Asian American medical students’ perceptions of careers in academic medicine. Journal of Career Development. doi: 10.1177/0894845317740225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.