Abstract

Background

Long‐term drug treatment of schizophrenia with typical antipsychotic drugs has limitations: 25 to 33% of sufferers have illnesses that are treatment resistant. Clozapine is an antipsychotic drug, which is claimed to have superior efficacy and to cause fewer motor adverse effects than typical drugs for people with treatment‐resistant illnesses. Clozapine carries a significant risk of serious blood disorders, which necessitates mandatory weekly blood monitoring at least during the first months of treatment.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of clozapine compared with typical antipsychotic drugs in people with schizophrenia.

Search methods

For the current update of this review (November 2008) we searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register.

Selection criteria

All relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data independently. For dichotomous data we calculated relative risks (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) on an intention‐to‐treat basis, based on a fixed‐effect model. We calculated numbers needed to treat/harm (NNT/NNH) where appropriate. For continuous data, we calculated weighted mean differences (WMD) again based on a fixed‐effect model.

Main results

We have included 52 trials (4746 participants) in this review. Forty‐four of the included studies are less than 13 weeks in duration, and, overall, trials were at a significant risk of bias. We found no significant difference in the effects of clozapine and typical neuroleptic drugs for broad outcomes such as mortality, ability to work or suitability for discharge at the end of the study. Clinical improvements were seen more frequently in those taking clozapine (n=1119, 14 RCTs, RR 0.72 CI 0.7 to 0.8, NNT 6 CI 5 to 8). Also, participants given clozapine had fewer relapses than those on typical antipsychotic drugs (n=1303, RR 0.62 CI 0.5 to 0.8, NNT 21 CI 15 to 49). BPRS scores showed a greater reduction of symptoms in clozapine‐treated participants, (n=1205, 17 RCTs, WMD ‐3.79 CI ‐4.9 to ‐2.7), although the data were heterogeneous ( I2=69%). Short‐term data from the SANS negative symptom scores favoured clozapine (n=196, 6 RCTs, WMD ‐7.21 CI ‐8.9 to ‐5.6). We found clozapine to be more acceptable in long‐term treatment than conventional antipsychotic drugs (n=982, 6 RCTs, RR 0.60 CI 0.5 to 0.7, NNT 15 CI 12 to 20). Blood problems occurred more frequently in participants receiving clozapine (3.2%) compared with those given typical antipsychotic drugs (0%) (n=1031, 13 RCTs, RR 7.09 CI 2.0 to 25.6). Clozapine participants experienced more drowsiness, hypersalivation or temperature increase, than those given conventional neuroleptics. However, those receiving clozapine experienced fewer motor adverse effects (n=1495, 19 RCTs, RR 0.57 CI 0.5 to 0.7, NNT 5 CI 4 to 6).

The clinical effects of clozapine were more pronounced in participants resistant to typical neuroleptics in terms of clinical improvement (n=370, 4 RCTs, RR 0.71 CI 0.6 to 0.8, NNT 4 CI 3 to 6) and symptom reduction. Thirty‐four per cent of treatment‐resistant participants had a clinical improvement with clozapine treatment.

Authors' conclusions

Clozapine may be more effective in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia, producing clinically meaningful improvements and postponing relapse, than typical antipsychotic drugs ‐ but data are weak and prone to bias. Participants were more satisfied with clozapine treatment than with typical neuroleptic treatment. The clinical effect of clozapine, however, is, at least in the short‐term, not reflected in measures of global functioning such as ability to leave the hospital and maintain an occupation. The short‐term benefits of clozapine have to be weighed against the risk of adverse effects. Within the context of trials, the potentially dangerous white blood cell decline seems to be more frequent in children and adolescents and in the elderly than in young adults or people of middle age.

The existing trials have largely neglected to assess the views of participants and their families on clozapine. More community‐based long‐term randomised trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of clozapine on global and social functioning as trials in special groups such as people with learning disabilities.

Plain language summary

Clozapine versus typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a serious, chronic and relapsing mental illness with a worldwide lifetime prevalence of about one per cent. Schizophrenia is characterised by 'positive' symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions and 'negative' symptoms such as emotional numbness and withdrawal. One quarter of those who have experienced an episode of schizophrenia recover and the illness does not recur. Another 25% experience an unremitting illness. Half do have a recurrent illness but with long episodes of considerable recovery from the positive symptoms. The overall cost of the illness to the individual, their carers and the community is considerable.

Antipsychotic medications are classified into typical and atypical drugs. First generation or 'typical' antipsychotic drugs such as chlorpromazine and haloperidol have been the mainstay of treatment, and are effective in reducing the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, but negative symptoms are fairly resistant to treatment. In addition, drug treatments are associated with adverse effects which can often compromise compliance with medication and therefore increase the incidences of relapse.

People who do not respond adequately to antipsychotic medication are sometimes given the 'atypical' antipsychotic drug clozapine, which has been found to be effective for some people with treatment‐resistant schizophrenia. Clozapine is also associated with having fewer movement disorders than chlorpromazine, but may induce life‐threatening decreases in white blood cells (agranulocytosis). We reviewed the affects of clozapine in people with schizophrenia compared with typical antipsychotic drugs drugs.

This review supports the notion that clozapine is more effective than typical antipsychotic drugs for people with schizophrenia in general, and for those who do not improve on typical antipsychotic drugs in particular. Clozapine is associated with less movement adverse effects than typical antipsychotic drugs, but it may cause serious blood‐related adverse effects. White blood cell count monitoring is mandatory for all people taking clozapine. There is a worry, however, that studies are ‐ at the very least ‐ moderately prone to bias favouring clozapine. Better conduct and reporting of trials could greatly have increased our confidence in the results.

Summary of findings

Background

Arguably, the psychopharmacology of schizophrenia has witnessed two major discoveries, the discovery of chlorpromazine and of clozapine. The discovery of chlorpromazine was followed by the introduction of a large family of drugs that are now known as 'typical neuroleptics' or 'first generation antipsychotic drugs'. The putative finding that clozapine is effective in people who have treatment‐resistant schizophrenia (Kane 1988 (CPZ)) stimulated a frantic search for a newer group of drugs known collectively as the 'atypical neuroleptics' or 'second generation antipsychotic drugs'.

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is a chronic, relapsing mental illness and has a worldwide lifetime prevalence of about 1% irrespective of culture, social class and race. Schizophrenia is characterised by positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions and negative symptoms such as emotional numbness and withdrawal. One quarter of those who have experienced an episode of schizophrenia recover and the illness does not recur. Another 25% experience an unremitting illness. Half do have a recurrent illness but with long episodes of considerable recovery from the positive symptoms. Current medication is effective in reducing positive symptoms, but negative symptoms are fairly resistant to treatment. In addition, drug treatments are associated with adverse effects and the overall cost of the illness to the individual, their carers and the community is considerable.

Description of the intervention

Clozapine has been in use for the treatment of schizophrenia since the early 1960s (Hippius 1989). Although its availability has not been interrupted in parts of the world including China and some countries in South America, it was withdrawn from Western markets in 1975 after reports of agranulocytosis (a substantial decline in the white blood cells which made the individuals dangerously susceptible to infection) leading to death in some clozapine‐treated patients (Idänpään‐Heikkilä 1975). More recent studies suggested that clozapine was more effective than other antipsychotic drugs against treatment‐resistant schizophrenia (Kane 1988 (CPZ), Meltzer 1989). Treatment‐resistant schizophrenia is a term generally used for the failure of signs or symptoms to respond satisfactorily to at least two different antipsychotic drugs (Meltzer 1997, Crilly 2007). Health authorities in many countries have approved the use of clozapine only for people with schizophrenia who were (i) resistant to typical neuroleptics and (ii) compliant with blood monitoring. People taking clozapine are required to have their blood sampled at least once a week for the first 18 weeks of treatment and at least once a month thereafter. Another potentially fatal adverse effect of clozapine that has been recently identified is that of myocarditis which usually develops within the first month of commencement and presents with signs of cardiac failure and cardiac arrhythmias (Haas 2007). Echocardiograms are recommended every six months to exclude cardiac damage. People receiving clozapine should also have their fasting blood glucose monitored; in addition to type II diabetes, significant weight gain is frequently experienced by people treated with clozapine (Wirshing 1999). Other adverse effects of clozapine include lowered seizure threshold, hepatic dysfunction and adverse effects associated with its interaction with different neurotransmitters' receptors.

How the intervention might work

Clozapine is a strong antagonist at different subtypes of adrenergic, cholinergic, histaminergic and serotonergic receptors. It may also have a different pattern of adhesion to receptors than other drugs. Clozapine’s common adverse effects are predominantly anticholinergic in nature, with dry mouth, sedation and constipation, drooling, and orthostasis.

Why it is important to do this review

This review represents an important and considerable update of the previous version of this work (Wahlbeck 1999 b).

Objectives

To review the effects of clozapine compared with typical antipsychotic drugs for people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Where trials are described as 'double‐blind' but are only implied as being randomised, we included these trials in a sensitivity analysis. If there were no substantive differences within primary outcomes (see Types of outcome measures) when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then we included these in the final analysis. If there were substantive differences, we only used clearly randomised trials and described the results of the sensitivity analysis in the text. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

We included people with schizophrenia and other types of schizophrenia‐like psychosis (e.g. schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders), irrespective of the diagnostic criteria used. There is no clear evidence that the schizophrenia‐like psychoses are caused by fundamentally different disease processes or require different treatment approaches (Carpenter 1994). The group of studies dealing with people with illness that had been labelled as 'resistant' were also analysed separately.

Types of interventions

1. Clozapine (trade names Clozaril, Froidir, Leponex, Fazaclo, Klozapol): any dose. 2. Typical antipsychotic drugs: any dose. Another Cochrane systematic review has focused on comparing clozapine to atypical antipsychotic drugs (Lobos 2007).

Types of outcome measures

We grouped outcomes by time ‐ short‐term (up to 12 weeks), medium‐term (13 to 26 weeks) and long‐term (over 26 weeks).

Primary outcomes

Global state, no clinically important change (as defined by individual studies) ‐ medium‐term

Secondary outcomes

1. Death ‐ suicide and natural causes

2. Global state 2.1 Relapse (defined by deterioration in mental state requiring further treatment or hospitalisation) 2.2 Average endpoint global state score 2.3 Average change in global state scores

3. Service outcomes 3.1 Hospitalisation 3.2 Inability to be discharged from hospital

4. Mental state (with particular reference to the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia) 4.1 No clinically important change in general mental state 4.2 Average endpoint general mental state score 4.3 Average change in general mental state scores 4.4 No clinically important change in specific symptoms (positive symptoms of schizophrenia, negative symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, mania) 4.5 Average endpoint specific symptom score 4.6 Average change in specific symptom scores

5. General functioning 5.1 No clinically important change in general functioning including working ability 5.2 Average endpoint general functioning score 5.3 Average change in general functioning scores 5.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills 5.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills 5.6 Average change in specific aspects of functioning, such as social or life skills

6. Behaviour 6.1 No clinically important change in general behaviour 6.2 Average endpoint general behaviour score 6.3 Average change in general behaviour scores 6.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of behaviour 6.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of behaviour 6.6 Average change in specific aspects of behaviour

7. Adverse effects ‐ general and specific (Important adverse effects included movement disorders, weight gain, fits and blood reactions leading to therapy discontinuation) 7.1 Clinically important general adverse effects 7.2 Average endpoint general adverse effect score 7.3 Average change in general adverse effect scores 7.4 Clinically important specific adverse effects 7.5 Average endpoint specific adverse effects 7.6 Average change in specific adverse effects

8. Engagement with services

9. Satisfaction with treatment (including subjective well‐being and family burden) 9.1 Leaving the studies early 9.2 Recipient of care not satisfied with treatment 9.3 Recipient of care average satisfaction score 9.4 Recipient of care average change in satisfaction scores 9.5 Carer not satisfied with treatment 9.6 Carer average satisfaction score 9.7 Carer average change in satisfaction scores

10. Quality of life 10.1 No clinically important change in quality of life 10.2 Average endpoint quality of life score 10.3 Average change in quality of life scores 10.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of quality of life 10.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of quality of life 10.6 Average change in specific aspects of quality of life

11. Economic outcomes 11.1 Direct costs 11.2 Indirect costs

12. Cognitive functioning 12.1 No clinically important change in cognitive functioning 12.2 Average endpoint cognitive functioning score 12.3 Average change in cognitive functioning scores 12.4 No clinically important change in specific aspects of cognitive functioning 12.5 Average endpoint specific aspects of cognitive functioning 12.6 Average change in specific aspects of cognitive functioning

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. Update of 2009 We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (November 2008) using the phrase:

{[ clozapin* or clozaril* or leponex * in title, abstract, index terms of REFERENCE] or [clozapin* or clozaril* or leponex* in interventions of STUDY]}

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

2. Previous searches for earlier versions of this review Please see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

Please see Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two reviewers independently inspected all study citations identified by the searches and obtained full reports of the studies of agreed relevance. Where disputes arose, we acquired the full report for more detailed scrutiny. The two reviewers inspected these articles independently to assess their relevance to this review. Again, where disagreement occurred we attempted to resolve this through discussion; if doubt still remained we added these trials to the list of those awaiting assessment pending acquisition of further information.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction We independently extracted data from included studies. Again, any disagreement was discussed, decisions documented and, if necessary, authors of studies contacted for clarification. When this was not possible and further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, we did not enter data and added the trial to the list of those awaiting assessment.

2. Management We extracted the data onto standard, simple forms. Where possible, we entered data into RevMan in such a way that the area to the left of the 'line of no effect' indicates a 'favourable' outcome for clozapine. Where this was not possible, (e.g. scales that calculate higher scores = improvement) we labelled the graphs in RevMan analyses accordingly so that the direction of effects were clear.

3. Scale‐derived data A wide range of instruments are available to measure outcomes in mental health studies. These instruments vary in quality and many are not validated, or are even ad hoc. It is accepted generally that measuring instruments should have the properties of reliability (the extent to which a test effectively measures anything at all) and validity (the extent to which a test measures that which it is supposed to measure) (Rust 1989). Unpublished scales are known to be subject to bias in trials of treatments for schizophrenia (Marshall 2000). Therefore we only included continuous data from rating scales if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal. In addition, we set the following minimum standards for instruments: the instrument should either be (a) a self‐report or (b) completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist) and (c) the instrument should be a global assessment of an area of functioning.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Again working independently, we assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. We would not have included studies where sequence generation was at high risk of bias or where allocation was clearly not concealed.

The categories are defined below: YES ‐ low risk of bias NO ‐ high risk of bias UNCLEAR ‐ uncertain risk of bias

If disputes arose as to which category a trial has to be allocated, again, resolution was made by discussion, after working with a third reviewer.

Earlier versions of this review used a different, less well‐developed, means of categorising risk of bias (see Appendix 2).

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the fixed‐effect risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). For statistically significant results we calculated the number needed to treat/harm statistic (NNT/H), and its 95% confidence interval (CI) using Visual Rx taking account of the event rate in the control group. It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation then leads to an overestimate of the impression of the effect. Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to binary data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into "clinically improved" or "not clinically improved". It was generally assumed that if there had been a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a, Leucht 2005b). It was recognised that for many people, especially those with chronic or severe illness, a less rigorous definition of important improvement (e.g. 25% on the BPRS) would be equally valid. If individual patient data were available, the 50% cut‐off was used for the definition in the case of non‐chronically ill people and 25% for those with chronic illness. If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2. Continuous data Continuous data on outcomes in mental health trials are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data we applied the following standards to all endpoint data derived from continuous measures. We applied these criteria before inclusion: (a) standard deviations and means had to be obtainable; and, for finite scores, such as endpoint measures on rating scales, (b) the standard deviation (SD), when multiplied by 2 had to be less than the mean (as otherwise the mean was unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution) (Altman 1996). If a scale starts from a positive value (such as PANSS, which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above in (b) should be modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score.

We did not graphically show skewed endpoint data from studies with less the 200 participants, but added to 'Other data' tables and briefly commented on in the text. However, skewed endpoint data from larger studies (=/>200 participants) pose less of a problem and we entered the data for analysis.

For continuous mean change data (endpoint minus baseline) the situation is even more problematic. In the absence of individual patient data it is impossible to know if change data are skewed. The RevMan meta‐analyses of continuous data are based on the assumption that the data are, at least to a reasonable degree, normally distributed. Therefore we included such data, unless endpoint data were also reported from the same scale.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials Studies increasingly employ cluster randomisation (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intraclass correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This can cause Type I errors (Bland 1997, Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intraclass correlation coefficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a design effect. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) [Design effect=1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999). If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account intraclass correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report, we synthesised these with other studies using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over design A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in schizophrenia, we will only use data of the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not reproduce these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility At some degree of loss to follow‐up data must lose credibility (Xia 2007). We are forced to make a judgment where this is for the trials likely to be included in this review. Should more than 40% of data be unaccounted for by 8 weeks we did not reproduce these data or use them within analyses.

We attempted to include all people who had been randomised to clozapine or typical treatments. Where possible, we gave cases lost to follow up at the end of the study the worst outcome. For example, we treated those lost to follow up for the outcome of relapse in the analysis as having relapsed. Suicide was also treated as relapse. We agreed these rules before knowing the studies included. We tested the effects of inclusion of this assumption with sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity We considered all included studies without any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity.

2. Statistical 2.1 Visual inspection We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

2.2 Employing the I‐squared statistic This provided an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance. I‐squared estimate greater than or equal to 50% was interpreted as evidence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2008). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects (Egger 1997). We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were ten or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots were possible, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

Where possible we employed a fixed‐effect model for analyses. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us, however, random‐effects does put added weight onto the smaller of the studies ‐ those trials that are most vulnerable to bias. For this reason we favour using the fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When heterogeneous results were found, we investigated the reasons for this. Where heterogeneous data substantially altered the results and the reasons for the heterogeneity were identified, we did not summate these studies in the meta‐analysis, but presented separately and discussed in the text.

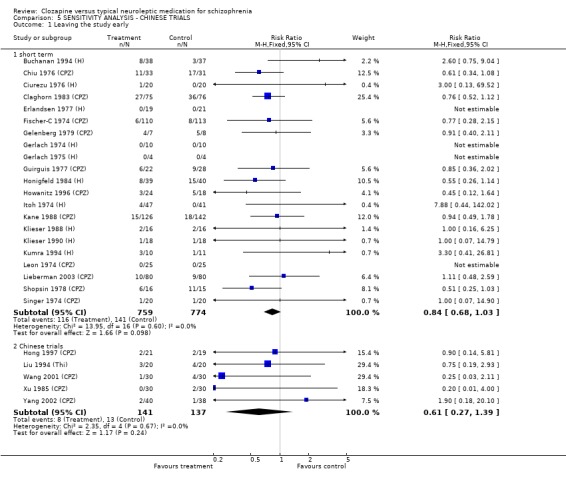

Sensitivity analysis

The 2008 update included many studies from China. As there is concern regarding quality of trials from China (Wu 2006) we conducted a sensitivity analysis to investigate whether the findings of these trials substantially differed from other trials.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

1. 1997 search During the original 1997 search in Biological Abstracts, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsycLIT, we found 139 full reports. We contacted the senior author of each trial published since 1980 and the manufacturer of clozapine (Novartis AG, Switzerland) for additional references, data, and unpublished trials. We also searched the ISI citation index for each selected trial in order to identify further studies, and the reference sections of selected studies were searched for additional trials. We identified 34 additional citations of studies possibly relevant to this review. Novartis AG had agreed to provide additional data on early clozapine studies sponsored by the company, but to date, we have not received any additional data.

Out of these 173 articles 111 were excluded, mostly because they used a non‐controlled design. On inspecting the full papers, relevant references found in these papers, references given by principal authors of recent studies and references provided by the manufacturer of clozapine, 37 separate randomised controlled trials comparing clozapine with typical neuroleptic treatment were found. Two papers were then excluded due to diagnostically mixed study populations (Angst 1971, Van Praag 1976) and three papers due to lack of satisfactory random allocation (Category C) (Bao 1988, Ruiz 1974, Yang 1988). Two papers were excluded due to lack of extractable data (Li 1987, Nahunek 1975).

2. 1999 search For the first update (October 1999) we included one additional trial (Howanitz 1996 (CPZ)) raising the number of included trials to 30 with 80 references. A search of citations listed in SCISEARCH yielded 1094 references, none of which fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

3. 2008 Update (2006 search) The 2008 update of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register of trials yielded 350 references of which 150 were Chinese. Most Chinese reports included an English abstract. We selected 12 trials for further inspection. We added one Chinese trial (Yang 2004 b) to awaiting assessment and sought further information and excluded (Cui 2002) because it contained no usable data. Ten Chinese trials met the inclusion criteria. Two trials which had been awaiting assessment previously were also included (Lieberman 2003 (CPZ), Volavka 2002 (H)).

4. 2009 Update (2008 search) The 2009 update of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register of trials yielded 843 references. Fourteen were selected for further inspection and 11 Chinese trials were added to the review as included studies.

Included studies

The current update of this review includes 52 studies. All were described as being randomised.

1. Study length Seven studies were longer than 26 weeks (long‐term) (Tamminga 1994 (H), Kane 1995 (H), Lee 1994 (mainly H), Essock 1996 (H/CPZ/Flu), Rosenheck 1993 (H), Lieberman 2003 (CPZ), Yang 2004 a (CPZ) ); Volavka 2002 (H) reported both short and medium‐term data; the remainder all fall into the 'short‐term' category with a maximum length of 12 weeks.

2. Design There are two cross‐over trials (Gerlach 1974 (H), Gerlach 1975 (H)). We were only able to extract data for mortality and relapse from the first phase of these studies.

3. Participants A total of 4746 participants are included from 52 trials conducted from 1974 and 2007. In the current revision, 11 trials were added and all were conducted in China. Thirty‐six studies involved participants with schizophrenia that had been diagnosed using operationalised criteria (DSM, ICD, CCMD‐2) whilst 16 studies did not report using any diagnostic tool, but only stated the type of illness.

Eight trials include only participants with treatment‐resistant schizophrenia (Klieser 1988 (H), Hong 1997 (CPZ), Kane 1988 (CPZ), Essock 1996 (H/CPZ/Flu), Kumra 1994 (H), Rosenheck 1993 (H), Buchanan 1994 (H), Volavka 2002 (H)). Most studies included participants with mean ages around the late thirties when reported. One trial focused on children or adolescents suffering from schizophrenia (Kumra 1994 (H)), and another trial studied the efficacy of clozapine in elderly people with schizophrenia (Howanitz 1996 (CPZ)).

4. Settings The vast majority of the trials were in‐hospital studies. To our knowledge, only two trials were performed in the community (Kane 1995 (H), Buchanan 1994 (H)). Two long‐term trials were hospital‐based with follow up of discharged participants (Essock 1996 (H/CPZ/Flu), Rosenheck 1993 (H)). One Chinese study (Wang 2001 (CPZ)) used participants who were outpatients, all other Chinese trials when reported were hospital‐based.

5. Interventions The following control treatments were used in different trials: chlorpromazine (29 trials), haloperidol (14 trials), various neuroleptics (two trials), clopenthixol (two trials), loxapine (two trials), perphenazine (one trial) thioridazine (two trials). For clarity we have incorporated these in the study tags: H denotes haloperidol, CPZ chlorpromazine, Clopen clopenthixol, and Thi thioridazine. Five trials used low doses of typical neuroleptic treatment, which may have benefited clozapine results in these studies (Chiu 1976 (CPZ), Leon 1974 (CPZ), Ciurezu 1976 (H), Erlandsen 1977 (H), Honigfeld 1984 (H)). Two of these studies used equal mg doses of clozapine and chlorpromazine (Chiu 1976 (CPZ), Leon 1974 (CPZ)) and the other three used comparatively low doses of haloperidol.

6. Outcomes Many trialists used symptom scales in assessing treatment effects mainly the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and its derivative The Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) scale. Some studies measured changes in negative symptoms using the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), and PANSS negative symptom sub‐score. The use of scoring data were in several cases precluded by the lack of standard deviation figures. Behavioural changes were measured by changes in the Nurse's Observation Scale for In‐patient Evaluation (NOSIE). Assessments of subjective well‐being were determined by authors' own global scales or Heinrichs‐Carpenter Quality of Life Scale.

Definitions of improvement differed across studies. This warranted some caution in drawing conclusions, as it was difficult to decide whether the results concerning clinical improvement were comparable. However, as with a pragmatic approach to diagnosis, it seemed unlikely that those judging improvement would have such dramatically differing criteria as to make summation inappropriate.

6.1 Outcome scales: only details of the scales that provided usable data are shown below. Reasons for exclusions of data are given under 'Outcomes' in the Characteristics of included studies table.

6.1.1 Global state 6.1.1.1 Clinical Global Impression ‐ CGI (Guy 1970) The CGI is a three‐item scale commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement. The items are: severity of illness; global improvement and efficacy index. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity and/or greater recovery. Nine studies reported data from this scale.

6.1.2 Mental state 6.1.2.1 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) The BPRS is an 18‐item scale measuring positive symptoms, general psychopathology and affective symptoms. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18‐item scale is commonly used. Scores can range from 0 to 126. Each item is rated on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', with high scores indicating more severe symptoms. Twenty studies reported data from this scale.

6.1.2.2 Mini Mental State Examination ‐ MMSE (Folstein 1975) This clinician‐administered clinical evaluation assesses cognition in five areas: orientation, immediate recall, attention and calculation, delayed recall, and language. The test takes 15 minutes to administer and the score ranges from 0 (severe impairment) to 30 (normal). Volavka 2002 (H) reported data from this scale.

6.1.2.3 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ‐ PANSS (Kay 1986) This schizophrenia scale has 30 items, each of which can be defined on a seven‐point scoring system varying from one (absent) to seven (extreme). This scale can be divided into three sub‐scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS‐P), and negative symptoms (PANSS‐N). A low score indicates lesser severity. Nine studies reported data from this scale.

6.1.2.4 Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms ‐ SANS (Andreasen 1983) This scale allows a global rating of the following negative symptoms: alogia (impoverished thinking), affective blunting, avolition‐apathy, anhedonia‐asociality, and attention impairment. Assessments are made on a six‐point scale from zero (not at all) to five (severe). Higher scores indicate more symptoms. Five studies reported data from this scale.

6.1.2.5 Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms ‐ SAPS (Andreasen 1983) This six‐point scale gives a global rating of positive symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations and disordered thinking. Higher scores indicate more symptoms. Wang 2001 (CPZ) reported data from this scale.

6.1.3 Behaviour. 6.1.3.1 Nurses Observational Scale of Inpatients Evaluation ‐ NOSIE (Honigfeld 1965) An 80‐item scale with items rated on a five‐point scale from zero (not present) to four (always present). Ratings are based on behaviour over the previous three days. The seven headings are social competence, social interest, personal neatness, cooperation, irritability, manifest psychosis and psychotic depression. The total score ranges from 0 to 320 with high scores indicating a poor outcome. Two studies reported data from this scale.

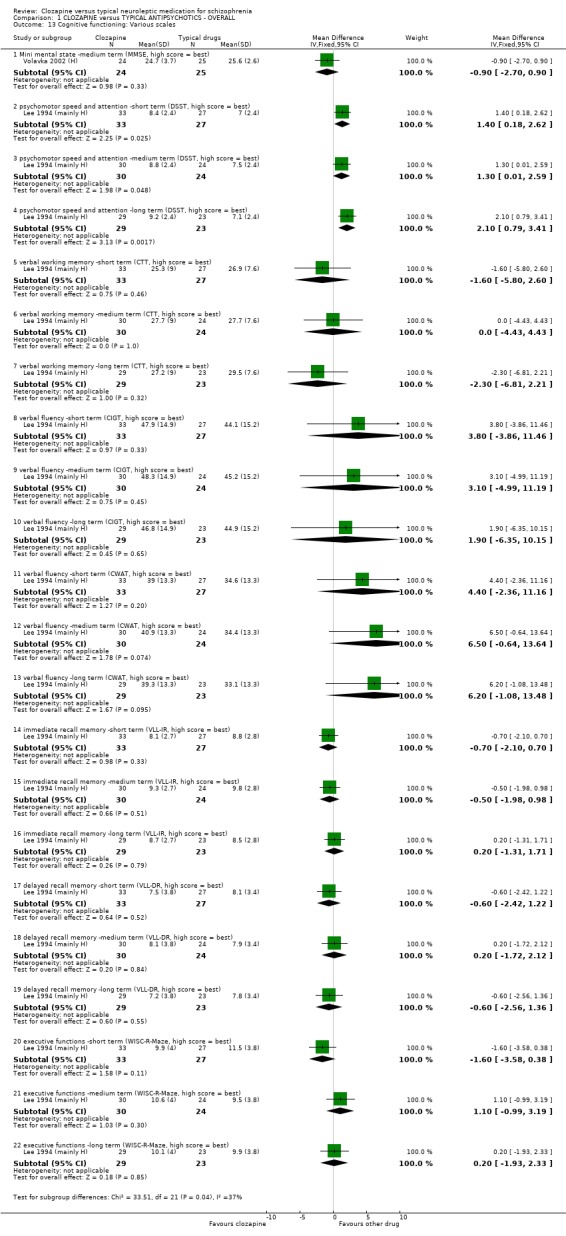

6.1.4 Cognitive functioning. 6.1.4.1 Category Instance Generation Test ‐ CIGT (Talland 1965) Higher score indicates a better outcome. Lee 1994 (mainly H) reported data from this scale.

6.1.4.2 Consonant Trigram Test ‐ CTT (Peterson 1959) Higher score indicates a better outcome. Lee 1994 (mainly H) reported data from this scale.

6.1.4.3 Controlled Word Association Test ‐ CWAT (Benton 1983). Higher scores indicate a better outcome. Lee 1994 (mainly H) reported data from this scale.

6.1.4.4 Digit Symbol Substitution Test ‐ DSST (Wechsler 1981) Higher score indicates a better outcome. Lee 1994 (mainly H) reported data from this scale.

6.1.4.5 The Short Cognitive Performance Test ‐ SKT (Lehfeld 1997) This is a psychometric instrument evaluating memory and attention deficits that has been developed and standardised in Germany. The test is useful for staging the severity of cognitive deficits and for assessing the benefits of therapy, especially with people suffering from dementia. Klieser 1990 (H) reported data from this scale.

6.1.4.6 Verbal List Learning Test ‐ VLLT (Buschke 1974) Higher score indicates a better outcome. Lee 1994 (mainly H) reported data from this scale.

6.1.4.7 Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children Revised ‐ WISC‐R (Wechsler 1974) Higher score indicates a better outcome. Lee 1994 (mainly H) reported data from this scale.

Excluded studies

We excluded over 400 studies from the review ‐ over 180 studies because they were not randomised trials. Many studies were excluded because clozapine had been compared with an atypical antipsychotic or because clozapine had been compared with placebo or with different dosages of clozapine. Forty‐four studies were excluded because no usable data could be extracted from the study report.

Awaiting assessment

Yang 2004 b is awaiting assessment until further information in obtained.

Ongoing studies

We are not aware of any relevant studies that are currently ongoing.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

All 52 studies were stated to be randomised but none provided descriptions of the methods used to generate the sequence or conceal it from those administering the treatment. All studies, therefore, are classified as of unclear quality with a moderate risk of selection bias and of overestimate of positive effect.

Blinding

Thirty‐two trials were stated to have used blinding, although most did not describe the methods used, and none tested the success of blinding for participants or evaluators. The remaining studies did not report whether blinding had been used. Again, this leaves little choice but to rate the risk of observer bias as at best unclear. This gathers further potential for overestimate of positive effects and underestimate of negative ones.

Incomplete outcome data

Many studies did not report the number of people leaving early; bias could be introduced to the final analysis if conducted on those completing the study only. Eleven studies undertook an 'intention‐to‐treat' (ITT) analysis in terms of both efficacy and adverse effects (Leon 1974 (CPZ), Gerlach 1974 (H), Gerlach 1975 (H), Honigfeld 1984 (H), Erlandsen 1977 (H), Ciurezu 1976 (H), Shopsin 1978 (CPZ), Kumra 1994 (H), Rosenheck 1993 (H), Buchanan 1994 (H)). Three studies performed an ITT analysis for adverse effects only (Itoh 1974 (H), Claghorn 1983 (CPZ), Hong 1997 (CPZ)). The two cross‐over trials provided very limited data for the first arm of the study (Gerlach 1974 (H), Gerlach 1975 (H)).

Selective reporting

Rates of attrition in the clozapine group (12%) and typical antipsychotic drugs comparison group (15%) were not excessively high compared with other compounds (Duggan 2005, Hunter 2003, Srisurapanont 2004), nor were they excessively divergent between groups. Attrition from studies involving participants who were treatment‐resistant were also low. Descriptions citing the reasons for leaving the study were not reported in the studies, and we were unable to report whether study attrition were due to protocol violations, withdrawals or drop outs, and therefore it remains unclear whether these trials were affected by attrition bias.

We identified no overt under reporting of outcomes that had been collected by the trialists.

Other potential sources of bias

Many of the trials were supported by the industry which stood to profit from positive results. Overall our judgement regarding the overall risk of bias in the individual studies is illustrated in Figure 1. Not one study had clear descriptions of sequence generation as well as concealment. Blinding was often undertaken but unconvincing and reporting biases common. Studies were often funded by industry with a pecuniary interest in the results. This, along with the other sources of bias outlined above gave us reason to judge, the risk of bias in the studies to be high, and therefore our estimates are likely to be over estimating any true positive effect, and underestimating negative effects.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS ‐ OVERALL for schizophrenia.

| CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS ‐ OVERALL for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Settings: mostly in hospital Intervention: CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS ‐ OVERALL | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS ‐ OVERALL | |||||

| Relapse ‐ short term | Study population | RR 0.62 (0.45 to 0.84) | 1303 (19 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 130 per 1000 | 81 per 1000 (58 to 109) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 63 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (28 to 53) | |||||

| Relapse ‐ long term | Study population | RR 0.22 (0.14 to 0.34) | 578 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 354 per 1000 | 78 per 1000 (50 to 120) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 270 per 1000 | 59 per 1000 (38 to 92) | |||||

| Global impression: 1. Not clinically improved ‐ short term | Study population | RR 0.72 (0.66 to 0.79) | 1119 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 661 per 1000 | 476 per 1000 (436 to 522) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 556 per 1000 | 400 per 1000 (367 to 439) | |||||

| Unable to work | Study population | RR 0.87 (0.75 to 1) | 416 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 622 per 1000 | 541 per 1000 (467 to 622) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 687 per 1000 | 598 per 1000 (515 to 687) | |||||

| Adverse effects: 1. Blood problems ‐ decreased white cell count | Study population | RR 7.09 (1.96 to 25.62) | 1031 (13 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Adverse effects: 4. Salivation ‐ too much | Study population | RR 2.25 (1.96 to 2.58) | 1479 (17 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 216 per 1000 | 486 per 1000 (423 to 557) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 105 per 1000 | 236 per 1000 (206 to 271) | |||||

| Adverse effects: 5a. Weight gain | Study population | RR 1.28 (1.07 to 1.53) | 590 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 394 per 1000 | 504 per 1000 (422 to 603) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 364 per 1000 | 466 per 1000 (389 to 557) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Randomisation not well described; blinding not likely, nor tested

Summary of findings 2. CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS for people with schizophrenia whose illness has proved resistant to treatment.

| CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS for people with schizophrenia whose illness has proved resistant to treatment | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with schizophrenia Settings: mostly in hospital Intervention: CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS ‐ TREATMENT RESISTANT SCHIZOPHRENIA | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS ‐ TREATMENT RESISTANT SCHIZOPHRENIA | |||||

| Relapse ‐ short term | Study population | RR 1.04 (0.61 to 1.78) | 396 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 117 per 1000 | 122 per 1000 (71 to 208) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 103 per 1000 | 107 per 1000 (63 to 183) | |||||

| Relapse ‐ long term | Study population | RR 0.17 (0.1 to 0.3) | 423 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 367 per 1000 | 62 per 1000 (37 to 110) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 367 per 1000 | 62 per 1000 (37 to 110) | |||||

| Global impression: 1. Not clinically improved ‐ short term | Study population | RR 0.71 (0.64 to 0.79) | 370 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 932 per 1000 | 662 per 1000 (596 to 736) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 957 per 1000 | 679 per 1000 (612 to 756) | |||||

| Global impression: 1. Not clinically improved ‐ long term | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.76 to 0.91) | 648 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 837 per 1000 | 695 per 1000 (636 to 762) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 836 per 1000 | 694 per 1000 (635 to 761) | |||||

| Adverse effects 1. Blood problems | Study population | RR 1.9 (0.97 to 3.71) | 827 (5 studies) | |||

| 26 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (25 to 96) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

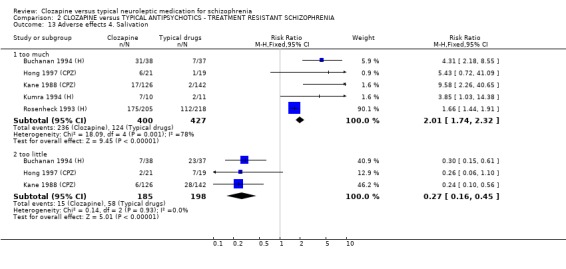

| Adverse effects 4. Salivation ‐ too much | Study population | RR 2.01 (1.74 to 2.32) | 827 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 290 per 1000 | 583 per 1000 (505 to 673) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 182 per 1000 | 366 per 1000 (317 to 422) | |||||

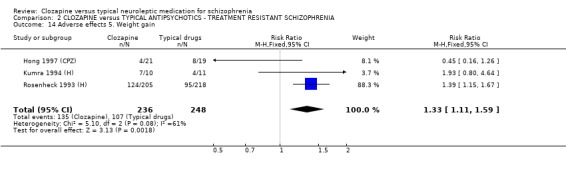

| Adverse effects 5. Weight gain | Study population | RR 1.33 (1.11 to 1.59) | 484 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 431 per 1000 | 573 per 1000 (478 to 685) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 421 per 1000 | 560 per 1000 (467 to 669) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Randomisation not well described; blinding not likely nor tested

1. COMPARISON 1. CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS ‐ OVERALL

All data are derived from 50 studies.

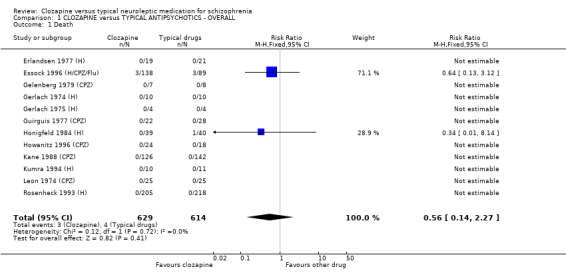

1.1 Death Four deaths occurred in 614 people treated with typical neuroleptics compared with three deaths in 629 people treated with clozapine. There were no significant differences in mortality between groups (n=1243, 12 RCTs, RR 0.56 CI 0.1 to 2.3).

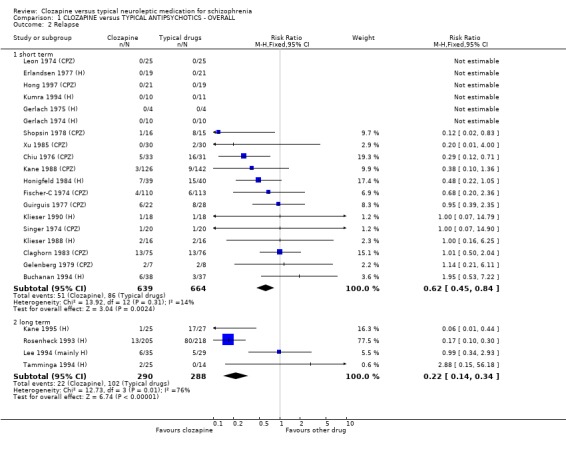

1.2 Relapse rate We included 19 short‐term studies, and found incidences of relapse were lower in the clozapine group (n=1303, RR 0.62 CI 0.5 to 0.8, NNT 21 CI 15 to 49) compared with typical antipsychotic drugs. Long‐term data (4 RCTs, n=578) also favoured clozapine but data were heterogeneous (I‐squared =76%) (RR 0.22 CI 0.1 to 0.3).

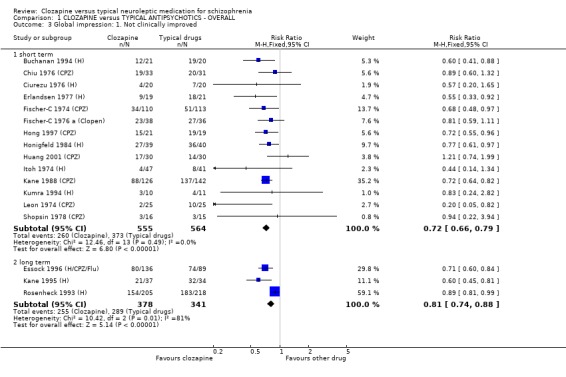

1.3 Global impression 1.3.1 Clinical improvement as defined by study authors We found that the number of participants who had not improved were lower in the clozapine group (n=1119, 14 RCTs, RR 0.72 CI 0.7 to 0.8, NNT 6 CI 5 to 8). Three long‐term studies also favoured clozapine (n=719, RR 0.81 CI 0.7 to 0.9) but the data are heterogeneous (I‐squared statistic 81%).

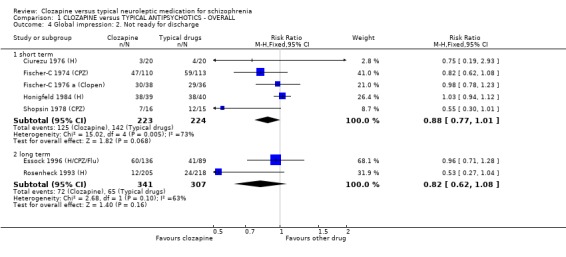

1.3.2 Readiness for hospital discharge There were no significant differences between treatment groups for the number of participants who were judged to be not ready for discharge (short‐term, n=447, 5 RCTs, RR 0.88 CI 0.8 to 1.0). Long‐term data also failed to show a significant difference (n=648, 2 RCTs, RR 0.82 CI 0.6 to 1.1).

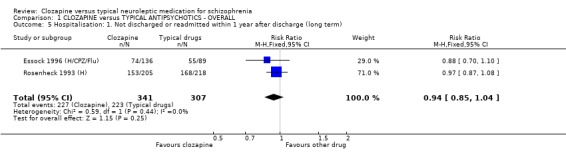

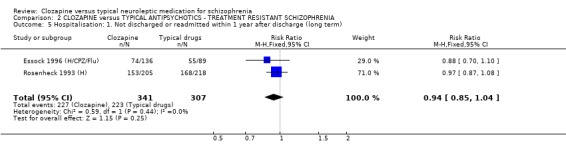

1.4 Hospitalisation ‐ Not discharged or readmitted within one year after discharge Data were available from two long‐term studies (Essock 1996 (H/CPZ/Flu), Rosenheck 1993 (H)), and we found no significant advantage for clozapine (n=648, RR 0.94 CI 0.9 to 1.0) compared with typical antipsychotic drugs.

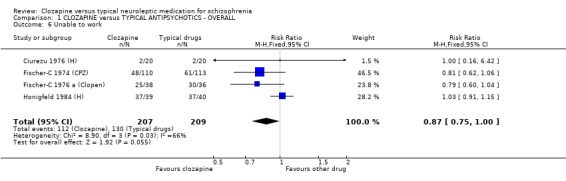

1.5 Unable to work We found no significant difference in the number of participants who were assessed as being unable to work (n=416, 4 RCTs, RR 0.87 CI 0.8 to 1.0), although the data suggested a trend favouring clozapine (p=0.06).

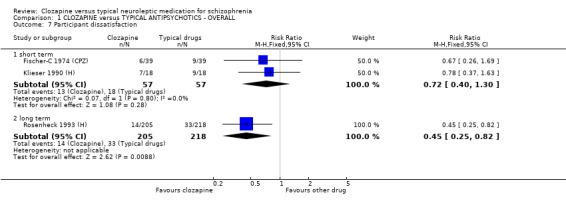

1.6 Participant dissatisfaction No significant differences were found for dissatisfaction with treatment in two short‐term studies (n=114, RR 0.72 CI 0.4 to 1.3). We found longer‐term data in (Rosenheck 1993 (H)). These favoured the clozapine group who were less dissatisfied with their treatment compared with conventional antipsychotic drugs (n=423, RR 0.45 CI 0.3 to 0.8, NNT 13 CI 9 to 37).

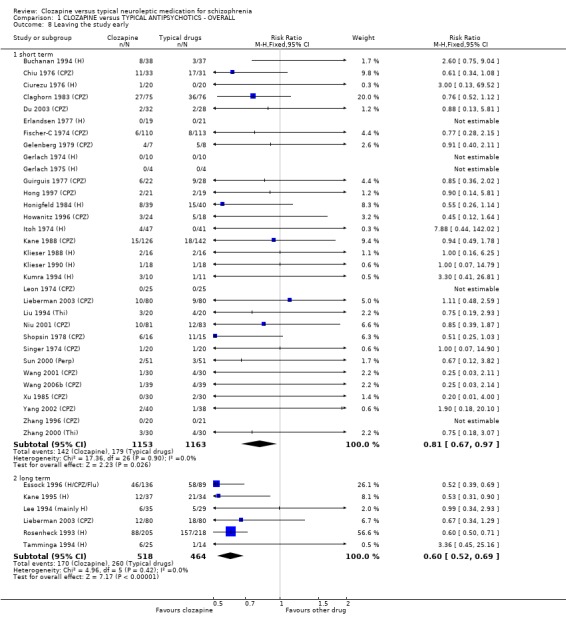

1.7 Leaving the study early ‐ acceptability of treatment We used leaving the study early data as a proxy measure for the acceptability of treatment. Short‐term data from 32 studies involving 2316 participants indicated that significantly more participants given clozapine found treatment acceptable (RR 0.81 CI 0.7 to 1.0, NNT 35 CI 20 to 217). Longer‐term data from six studies showed a significant benefit in the clozapine group (n=982, RR 0.60 CI 0.5 to 0.7, NNT15 CI 12 to 20). The long‐term attrition rate from clozapine treatment is approximately 33% and 56% when treated with typical antipsychotic drugs.

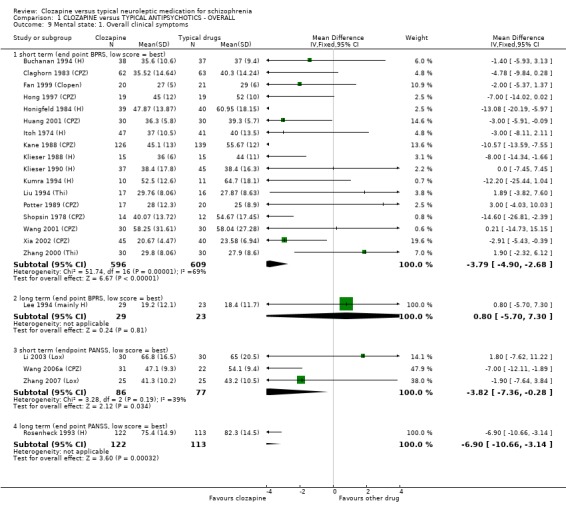

1.8 Mental state 1.8.1 BPRS and PANSS We found BPRS mental state scores favoured clozapine during short‐term assessment in 16 studies (n=1205, WMD ‐3.79 CI ‐4.9 to ‐2.7), although the data were heterogeneous (I squared=69%). Longer‐term BPRS data (Lee 1994 (mainly H)) were equivocal (n=52, WMD 0.80 CI ‐5.7 to 7.3). PANSS scores from three Chinese trials favoured the clozapine groups (n=163, WMD ‐3.82 CI ‐7.4 to ‐0.3) during short‐term analysis. Also, PANSS scores assessed over the long‐term favoured clozapine (Rosenheck 1993 (H), n=235, WMD ‐6.90 CI ‐10.7 to ‐3.1).

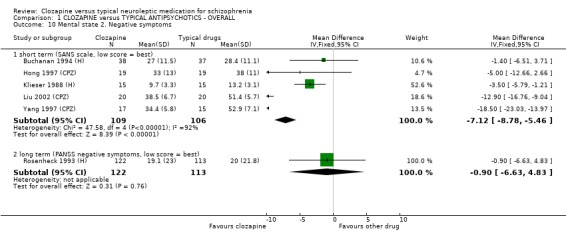

1.8.2 Negative symptoms Short‐term continuous data on negative symptom scores from six short‐term trials with 236 participants favoured clozapine (SANS, WMD ‐7.12 CI ‐8.8 to ‐5.5) but these are heterogeneous data (I squared=92%). Longer‐term negative symptoms scores assessed with the PANSS negative sub score were not significantly different (Rosenheck 1993 (H), n=235, WMD ‐0.90 CI ‐6.6 to 4.8).

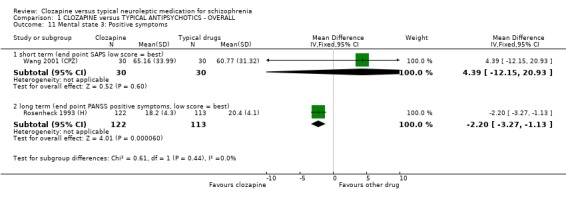

1.8.3 Positive symptoms We found short‐term SAPS scores were equivocal (Wang 2001 (CPZ), n=60, WMD 4.39 CI ‐12.2 to 20.9). Longer‐term data from the PANSS positive scores favoured clozapine (Rosenheck 1993 (H), n=235, WMD ‐2.20 CI ‐3.3 to ‐1.1).

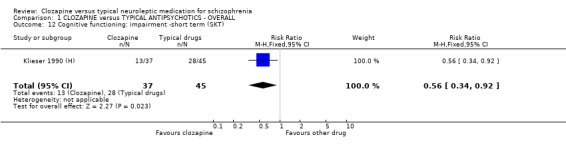

1.9 Cognitive function Cognitive impairment from one small study (n=82) favoured the clozapine group who experienced less impairment (Klieser 1990 (H), RR 0.56 CI 0.3 to 0.9, NNT 4 CI 3 to 21) when assessed with the SKT scale compared with those given typical antipsychotic drugs. One small study (Lee 1994 (mainly H), n=54) reported data on a series of cognitive functioning tests (verbal, memory or executive functions etc.) and we found outcomes to be equivocal, except for 'psychomotor speed and attention' scores which favoured the clozapine‐treated participants over the three pre‐stated cut‐off points (short‐term, WMD 1.40 CI 0.2 to 2.6, medium‐term, WMD 1.30 CI 0.01 to 3.0, long‐term, WMD 2.10 CI 0.8 to 3.4).

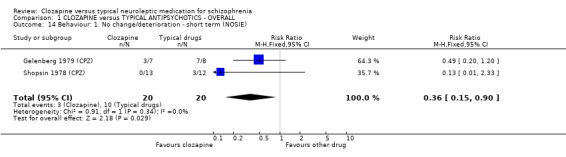

1.10 Behaviour We found behavioural scores from the NOSIE scale favoured clozapine (n=40, 2 RCTs, RR 0.36 CI 0.2 to 0.9, NNT 4 CI 3 to 20) compared with typical antipsychotic drugs, during short‐term analysis.

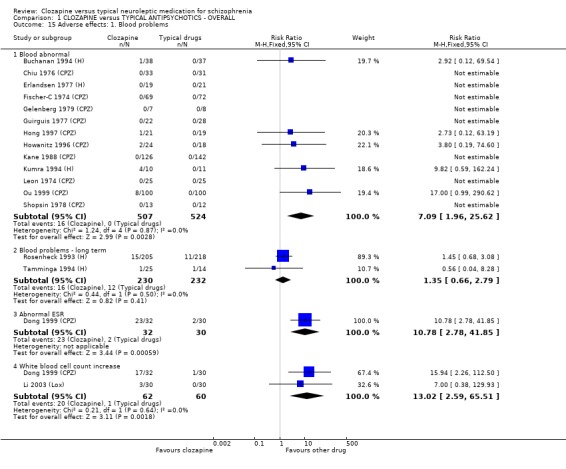

1.11 Adverse effects 1.11.1 Blood problems We defined blood problems as (a) any blood problem requiring withdrawal of participants from trials, or (b) leukopenia, defined as a white cell count <3000 per cubic mm, or (c) neutropenia, defined as granulocyte count <1500 per cubic mm. Blood problems occurred more frequently in participants receiving clozapine (3.2%) compared with those given typical antipsychotic drugs (0%) in short‐term studies (n=1031, 13 RCTs, RR 7.09 CI 2.0 to 25.6). We found two long‐term studies had a much higher incidence of blood problems in both clozapine (7%) and control group (haloperidol) (5.2%), but no significant differences were found (n=462, RR 1.35 CI 0.7 to 2.8) (Rosenheck 1993 (H), Tamminga 1994 (H)). We found incidences of abnormal ESR were higher in the clozapine group (Dong 1999 (CPZ), n=62, RR 10.78 CI 2.8 to 41.9, NNH 2 CI 2 to 9). Also, Dong 1999 (CPZ) and Li 2003 (Lox) reported changes in white blood cell count, and we found that the clozapine group had a significant increase in white cells (n=122, RR 13.02 CI 2.6 to 65.5, NNH 5 CI 2 to 38) compared with the typical antipsychotic group.

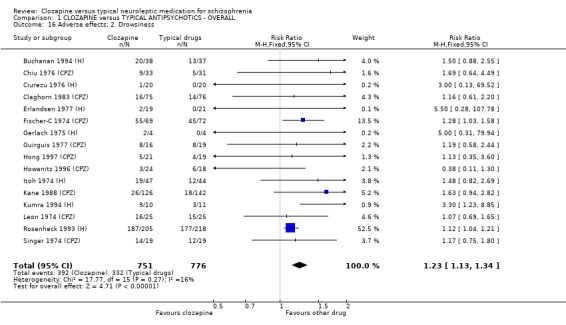

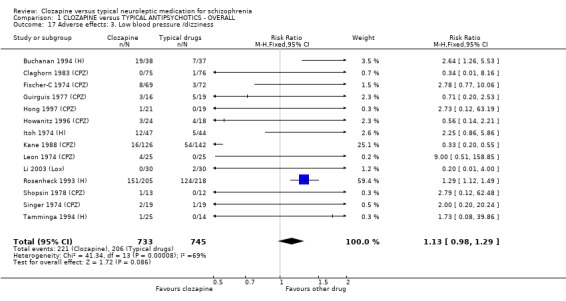

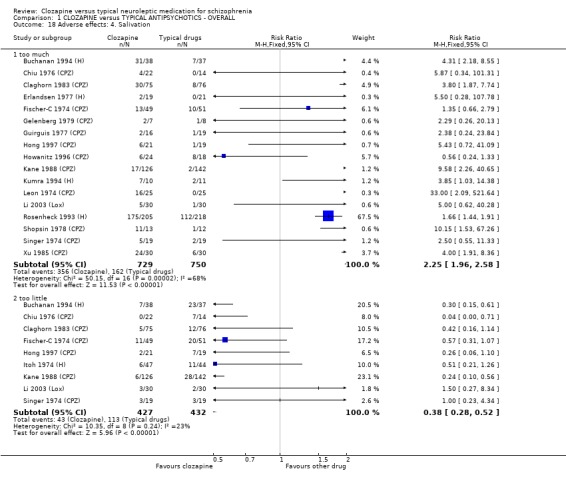

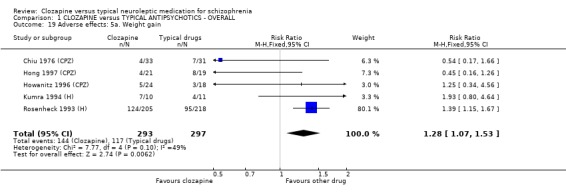

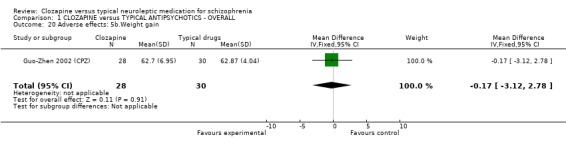

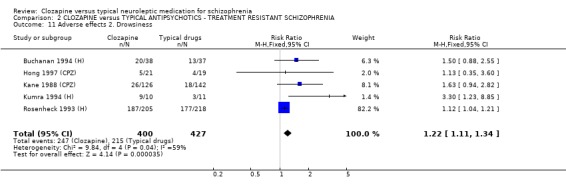

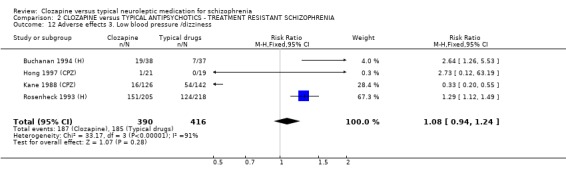

1.11.2 Other adverse effects Clozapine commonly caused drowsiness (n=1527, 16 RCTs, RR 1.23 CI 1.1 to 1.3, NNH 11 CI 7 to 18). No significant differences were found in the incidences of low blood pressure/dizziness (n=1478, 14 RCTs, RR 1.13 CI 1.0 to 1.3) between clozapine and the typical neuroleptic drugs. Salivation occurred more frequently in the clozapine group (n=1479, 17 RCTs, RR 2.25 CI 2.0 to 2.6), but data were heterogeneous (I squared=68%). Dry mouth occurred more frequently in the typical antipsychotic group (n=859, 9 RCTs, RR 0.38 CI 0.3 to 0.5, NNH 7 CI 6 to 8), compared with clozapine. We found participants given clozapine gained weight significantly more than those given typical antipsychotic drugs (n=590, 5 RCTs, RR 1.28 CI 1.1 to 1.5, NNH 10 CI 5 to 37). We found continuous data for weight gain (n=58, MD ‐0.17 CI ‐3.1 to 2.8) to be equivocal.

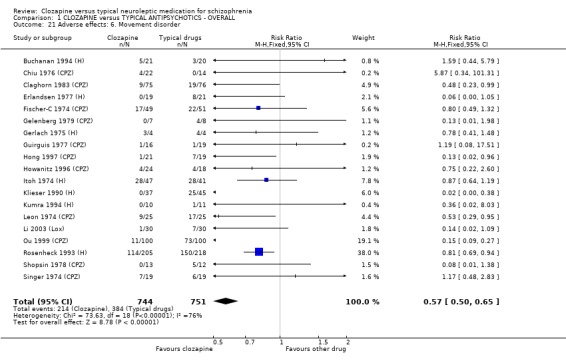

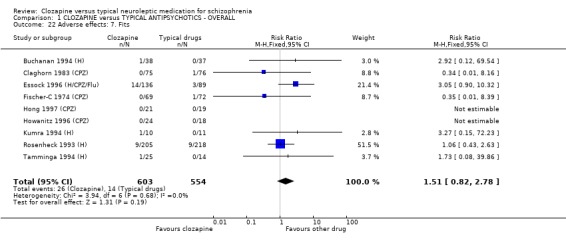

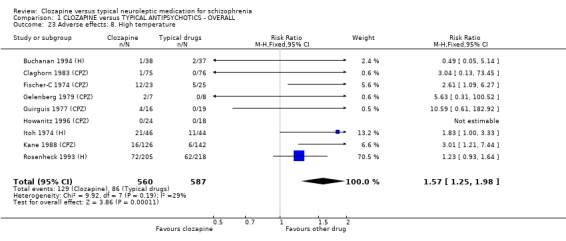

Extrapyramidal movement disorders were more frequent in those who were treated with conventional neuroleptics (n=1495, 19 RCTs, RR 0.57 CI 0.5 to 0.7, NNT 5 CI 4 to 6). No significant differences were found between clozapine and the typical neuroleptic drugs for fits (n=1157, 9 RCTs, RR 1.51 CI 0.8 to 2.8). Increases in body temperature were more frequent in the clozapine group (n=1147, 9 RCTs, RR 1.57 CI 1.3 to 2.0, NNH 12 CI 7 to 23).

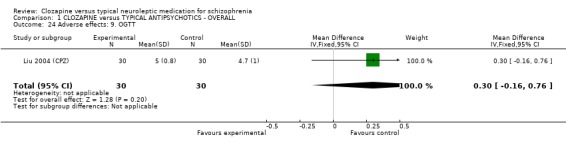

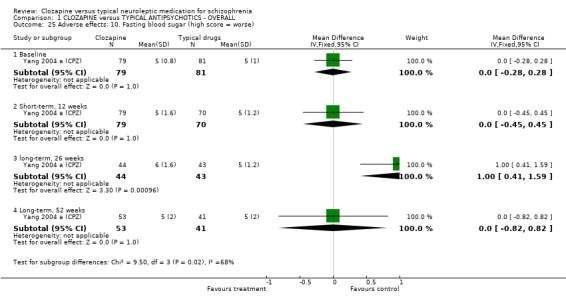

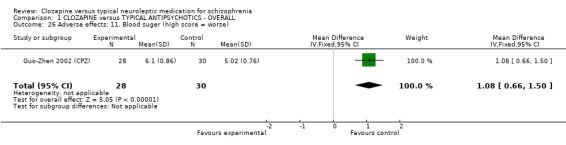

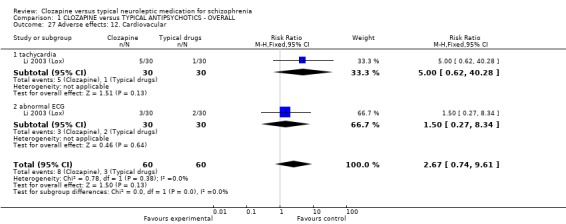

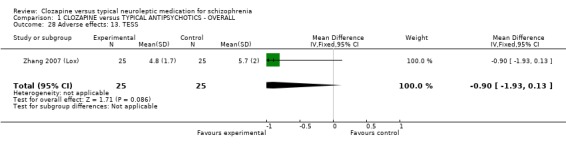

We found oral glucose tolerance tests data (Liu 2004 (CPZ)) were equivocal (WMD 0.30 CI ‐0.16, 0.76). One study from China reported continuous data for fasting blood glucose over different time cut‐off points, with most data being equivocal (Yang 2004 a (CPZ)). Long‐term data, however, revealed more participants in the clozapine group had abnormal blood glucose (n=87, WMD 1.00 CI 0.4 to 1.6). One study (Li 2003 (Lox)) reported data for tachycardia and electro‐cardiogram tests and we found no significant differences between clozapine and loxapine. We found no significant difference in TESS scores (n=50, 1 RCT, WMD ‐0.90 CI ‐1.93 to 0.13).

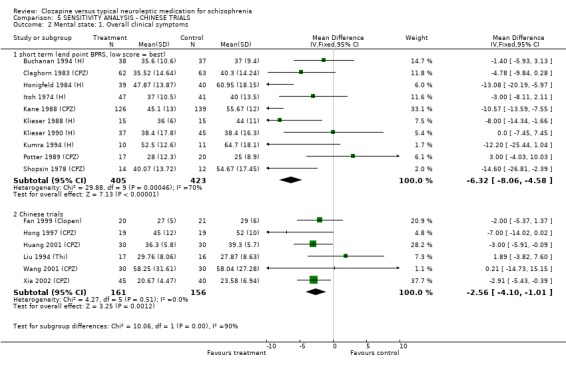

1.12 Sensitivity Analysis In the 2008 update we included ten trials that were conducted in China. Some differences in effect size were observed, but sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the results of Chinese trials followed the same general affect as trials conducted in western countries. The most meaningful comparisons were those related to short‐term studies. The overall reduction in clinical symptoms, for instance, in ten short‐term non‐Chinese studies were (n=828, BPRS, WMD ‐6.32 CI ‐8.1 to ‐4.6). Whilst, the overall reduction in clinical symptoms in six short‐term Chinese studies were (n=317, BPRS, WMD ‐2.56 CI ‐4.1 to ‐1.0). Similarly, the relative risk for leaving the study early in 21 short‐term non‐Chinese studies were (n=1553, RR 0.84 CI 0.7 to 1.0) compared with five short‐term Chinese studies (n=278, RR 0.61 CI 0.3 to 1.4).

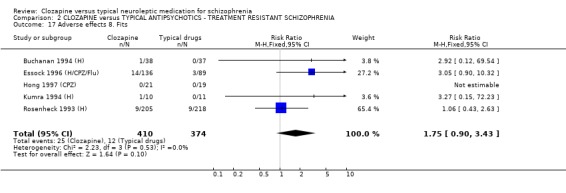

2. COMPARISON 2. CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS ‐ TREATMENT‐RESISTANT SCHIZOPHRENIA

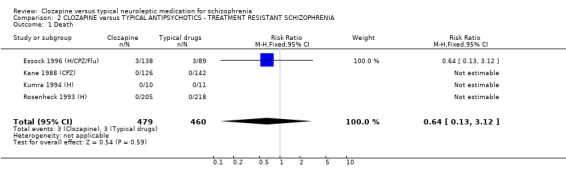

All data were derived from eight studies (Buchanan 1994 (H)), Essock 1996 (H/CPZ/Flu), Hong 1997 (CPZ), Kane 1988 (CPZ), Klieser 1988 (H), Kumra 1994 (H), Rosenheck 1993 (H), Volavka 2002 (H)) 2.1 Death We found no significant difference in mortality rates in four studies that included 939 participants with treatment‐resistant schizophrenia (RR 0.64 CI 0.1 to 3.1).

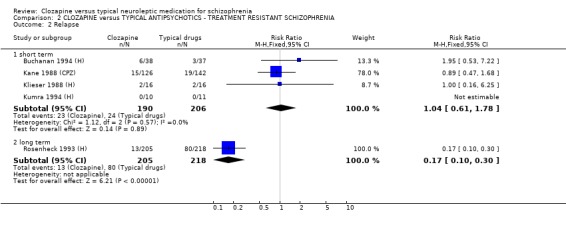

2.2 Relapse rate Analysis of four short‐term studies (396 people) did not reveal any significant difference in relapse rates between treatment groups (RR 1.04 CI 0.6 to 1.8), but we found data from one longer‐term study did favour clozapine (n=423, RR 0.17 CI 0.1 to 0.3, NNT 4 CI 4 to 4).

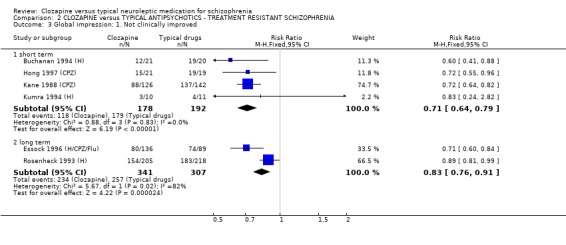

2.3 Global impression 2.3.1 Clinical improvement as defined by study authors We found that participants allocated to clozapine had greater clinical improvement than the typical antipsychotic group (n=370, 4 RCTs, RR 0.71 CI 0.6 to 0.8, NNT 4 CI 4 to 4). Similarly, longer‐term data also favoured clozapine (n=648, 2 RCTs, RR 0.83 CI 0.8 to 0.9, NNT 8 CI 5 to 14).

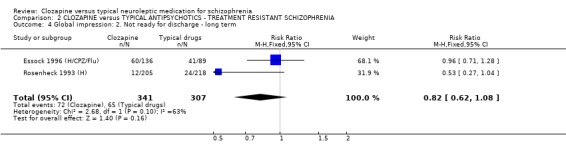

2.3.2 Readiness for hospital discharge No significant differences were found between clozapine and typical antipsychotic drugs when assessed on dischargeability in two longer‐term studies (n=648, RR 0.82 CI 0.6 to 1.1).

2.4 Hospitalisation The numbers of participants who were either not discharged from hospital or were readmitted revealed no significant differences (n=648, RR 0.94 CI 0.9 to 1.0) between intervention groups over one year's treatment.

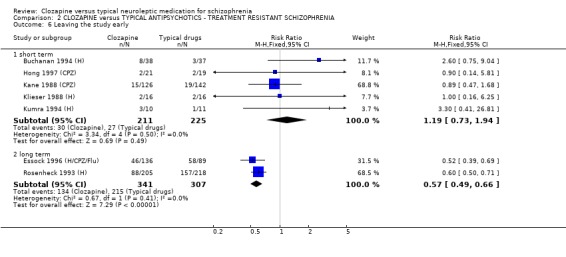

2.5 Leaving the study early ‐ acceptability of treatment The acceptability of treatment as measured by the number of people leaving the study revealed no significant difference between treatment groups (n=436, 5 RCTs, RR 1.19 CI 0.7 to 1.9) during short‐term analyses with 14% attrition in clozapine group and 12% in the typical antipsychotic drugs group. Longer‐term data, however, significantly favoured clozapine (n=648, RR 0.57 CI 0.5 to 0.7, NNT 4 CI 3 to 5) compared with typical antipsychotic drugs, with 39% attrition in the clozapine group compared with 70% leaving from the typical antipsychotic drugs group.

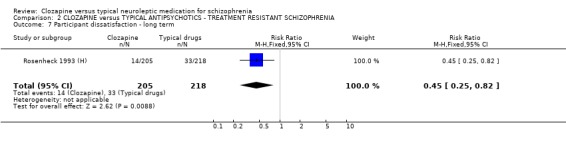

2.6 Participant satisfaction Only one long‐term study provided data on patient satisfaction and we found that more participants given clozapine were satisfied with their treatment (n=423, RR 0.45 CI 0.3 to 0.8, NNT 13 CI 9 to 37) than those allocated to typical antipsychotic drugs (Rosenheck 1993 (H)).

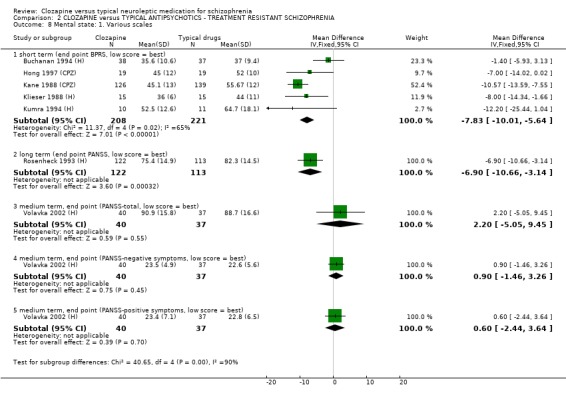

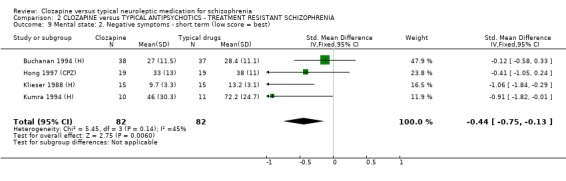

2.7 Mental state We found BPRS endpoint scores favoured clozapine (n=429, 5 RCTs, WMD ‐7.83 CI ‐10.0 to ‐5.6) compared with the typical antipsychotic group during short‐term analyses. Longer‐term data were equivocal (Rosenheck 1993 (H), n=235, WMD ‐6.90 CI ‐10.7 to ‐3.1). We found medium‐term data by Volavka 2002 (H) (n=77) were not significantly different for PANSS total, negative or positive symptom scores. We found negative symptoms score data from four short‐term studies favoured the clozapine group (n=164, SMD ‐0.44 CI ‐0.8 to ‐0.1) but these data contain the skewed Kumra 1994 (H) figures.

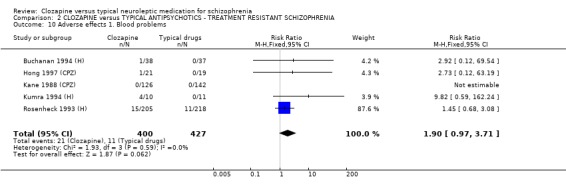

2.8. Adverse effects 2.8.1 Blood problems The differences in the number of participants with blood problems failed to reach statistical significance (p=0.06) although a trend could be seen which suggests blood problems were less frequent in the typical antipsychotic group (n=827, 5 RCTs, RR 1.90 CI 1.0 to 3.7).

2.8.2 Drowsiness Participants given clozapine experienced significantly more incidences of drowsiness (n=827, 5 RCTs, RR 1.22 CI 1.1 to 1.3, NNH 10 CI 7 to 20) compared with participants given typical antipsychotic drugs.

2.8.3 Low blood pressure/dizziness We found no significant difference in incidences of dizziness between groups (n=806, 4 RCTs, RR 1.08 CI 0.9 to 1.2).

2.8.4 Salivation Short‐term data indicated that participants given clozapine experience more hypersalivation (n=827, 5 RCTs, RR 2.01 CI 1.7 to 2.3) than those receiving typical antipsychotic drugs, but data were heterogeneous (I‐squared 78%). We found incidences of dry mouth were significantly lower in the clozapine group (n=383, 4 RCTs, RR 0.27 CI 0.2 to 0.5, NNT 5 CI 5 to 7) compared with typical drugs.

2.8.5 Weight gain The number of participants who gained weight were found to be higher in the clozapine group (n=484, 3 RCTs, RR 1.33 CI 1.1 to 1.6, NNH 8 CI 4 to 24) compared with those given typical antipsychotic drugs.

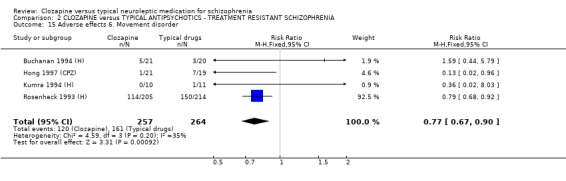

2.8.6 Movement disorder Incidences of movement disorder were significantly less frequent in the clozapine group (n=521, 4 RCTs, 0.77 CI 0.7 to 0.9, NNT 8 CI 6 to 17).

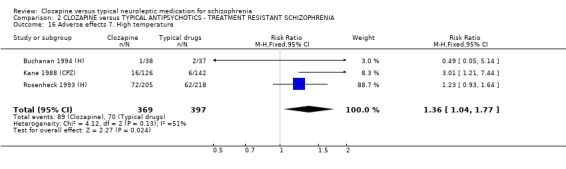

2.8.7 High temperature We found that the participants allocated to clozapine had more incidences of raised temperatures than the typical antipsychotic group (n=766, 3 RCTs, RR 1.36 CI 1.0 to 1.8), but data were heterogeneous (I‐squared 51%).

2.8.8 Fits No significant differences were found in the incidences of fits between groups (n=784, 5 RCTs, RR 1.75 CI 0.9 to 3.4).

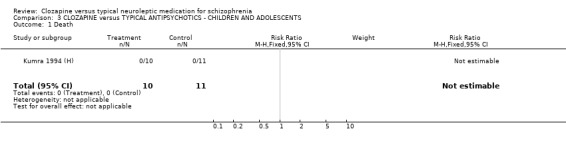

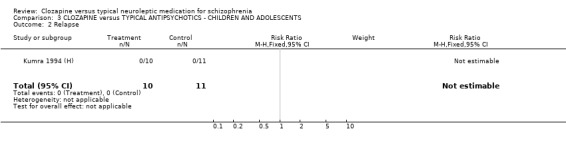

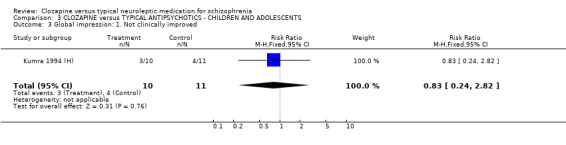

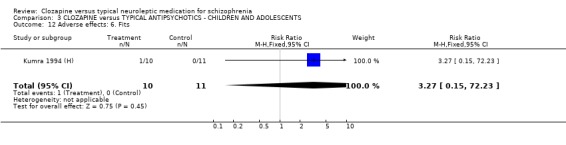

3. COMPARISON 3. CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS ‐ CHILDREN OR ADOLESCENTS

All data derived from one study (Kumra 1994 (H). 3.1 Death No deaths occurred in the (Kumra 1994 (H)) study (n=21).

3.2 Relapse No relapses occurred during the six weeks.

3.3 Global impression Data for 'not clinically improved' were equivocal (Kumra 1994 (H), n=21, RR 0.82 CI 0.2 to 2.8).

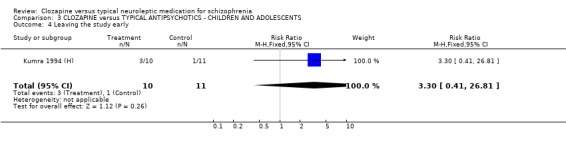

3.4 Leaving the study early We found no significant difference in the number of participants leaving the study early (n=11, RR 3.30 CI 0.4 to 26.8).

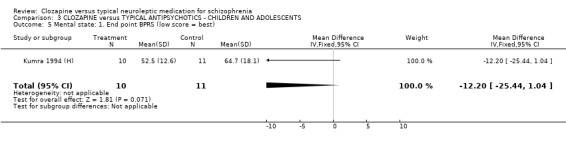

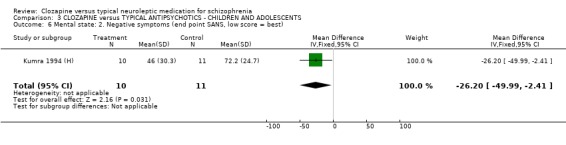

3.5 Mental state We found no significant difference in BPRS scores or SANS scores in the small study by (Kumra 1994 (H), n=21).

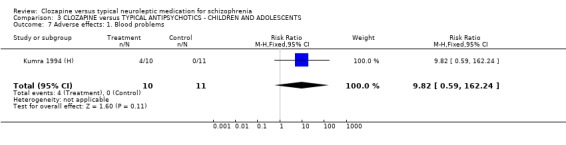

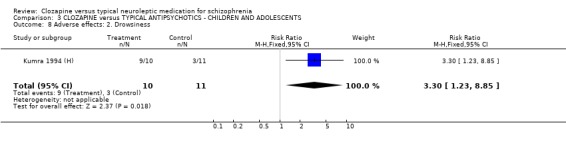

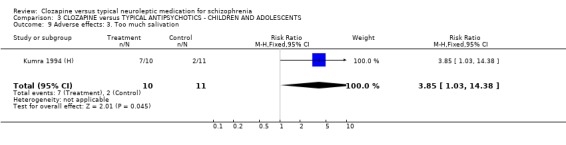

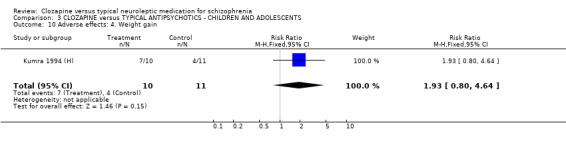

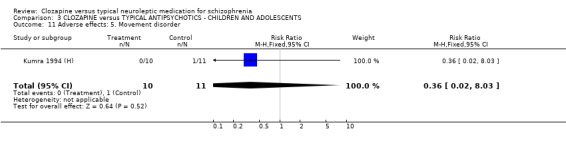

3.6 Adverse effects In the single study (Kumra 1994 (H)) dealing with adolescents or children, 40% (4/10) of the clozapine‐treated group developed blood problems (RR 9.82 CI 0.6 to 162.2) but the differences were not statistically significant. Drowsiness occurred more frequently in the clozapine group (n=21, RR 3.30 CI 1.2 to 8.9, NNH 2 CI 2 to 16). Hypersalivation also occurred more frequently in the clozapine group (n=21, RR 3.85 CI 1.0 to 14.4, NNH 2 CI 2 to 185), compared with typical antipsychotic drugs. No statistically significant differences were found for weight gain, movement disorders or fits.

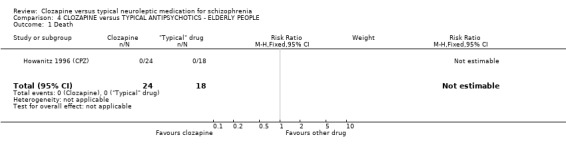

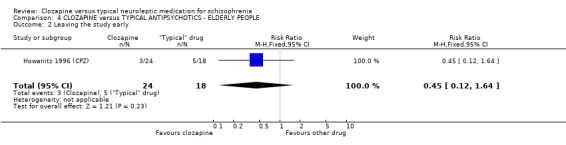

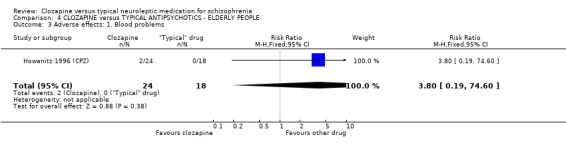

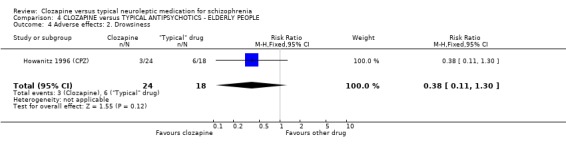

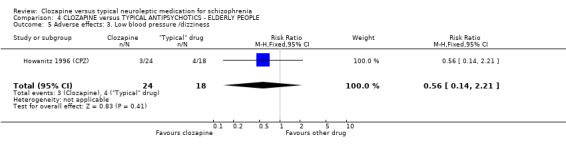

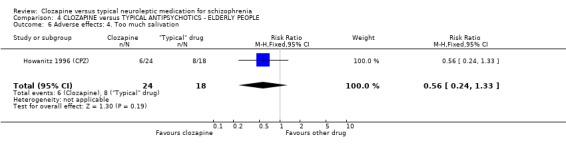

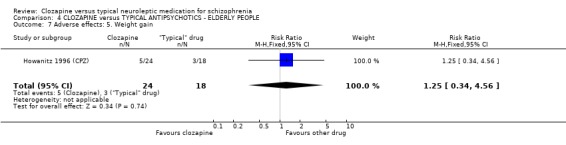

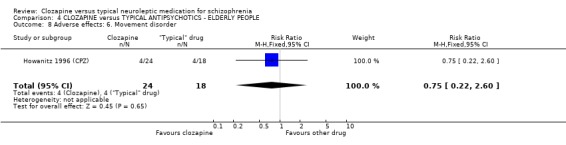

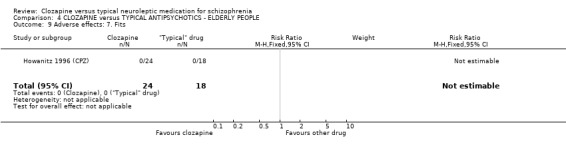

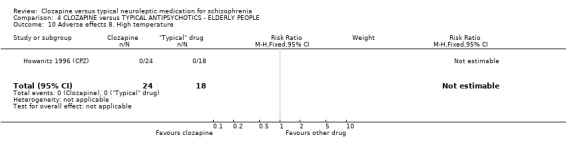

4. COMPARISON 4. CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS ‐ ELDERLY PEOPLE

All data derived from one study (Howanitz 1996 (CPZ). 4.1 Death No deaths occurred in the Howanitz 1996 (CPZ) study (n=42).

4.2 Leaving the study early We found no significant differences in rates of attrition (n=42).

4.3 Blood problems We found that elderly people were also at risk of developing blood problems with 8% affected in the clozapine group, but the differences were not statistically significant (n=42, RR 3.8 CI 0.2 to 74.6).

4.4 Other adverse effects The occurrence of drowsiness, dizziness, hypersalivation, weight gain, movement disorders or fits revealed no significant difference between groups.

5. Publication bias To look for a possible publication bias (that is, the possibility that studies with negative findings have not reached full publication) funnel graphs for clinical improvement, relapse frequency and number of people leaving early (acceptability) were constructed by plotting number of study participants (on the 'y' axis) against the log odds ratios (on the 'x' axis). No 'gap' in the funnel indicating a publication bias affecting the results were found.

Discussion

Summary of main results

1. COMPARISON 1. CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS ‐ OVERALL (Table 1) 1.1 Death This review did not reveal any difference in mortality between clozapine and the typical neuroleptic treatment groups. This would be a rare adverse event and the short duration of the included studies means that these trials would be unlikely to highlight any differences there may be.

1.2 Global impression 1.2.1 Relapse We found clozapine to be more advantageous than conventional neuroleptics in avoiding, or postponing, psychotic relapses at least in the short term. The relapse‐preventing effect of clozapine were heterogeneous in the long‐term studies, but favoured clozapine. However, the relapse‐preventing effect of clozapine were not seen in treatment‐resistant participants during short‐term analyses, but were effective in one longer‐term study (Rosenheck 1993 (H), n=423, RR 0.17 CI 0.1 to 0.3, NNT 4 CI 4 to 4).

1.2.2 Global impression ‐ clinical improvement Treating six people with schizophrenia with clozapine instead of typical neuroleptics resulted in one additional person showing a clinical improvement. This may be a real finding and, if so, important. However, as has been said many times above, there are reasons to consider that bias may also influence the research and therefore even this modest result my over estimate clozapine's effects.

Global impression was chosen as the primary outcome of this review. There is some suggestion of a real effect of clozapine over and above that of haloperidol, chlorpromazine and a few other typical drugs ‐ but the data are not strong and may include important biases in favour of clozapine.

1.3 Discharge ‐ not ready We found both short and long‐term studies failed to show any advantage for participants given clozapine compared with typical antipsychotic drugs or for hospital readmission in long‐term studies.

1.4 Unable to work About half of all participants in the four included studies were judged as being unable to work. The outcome data between groups were not significantly different but the graph revealed a trend favouring clozapine (p=0.06). More studies may have produced a significant outcome.

1.5 Participant dissatisfaction Clozapine participants were more satisfied with their treatment in one long‐term study (Rosenheck 1993 (H)). This was an important finding as participant satisfaction may enhance compliance. Two short‐term studies were equivocal, and more studies measuring satisfaction with treatment are needed to substantiate the long‐term benefit.

1.6 Leaving the study early Using study attrition as a proxy measure of acceptability, the results favoured clozapine in short‐term studies. Longer‐term studies revealed a larger advantage for clozapine over typical antipsychotic drugs (n=982, RR 0.60 CI 0.5 to 0.7, NNT 15 CI 12 to 20), and as with participant dissatisfaction the benefits are more apparent during the longer durations of treatment.

1.7 Mental state 1.7.1 BPRS/PANSS We found short‐term studies indicated a greater improvement for participants on clozapine compared with typical antipsychotic drugs, but the data were heterogeneous, the differences in overall reduction were small, and the clinical significance of a difference of this magnitude may be questioned. We found long‐term BPRS data (Lee 1994 (mainly H)) from a single small study (n=52) to be equivocal and without much larger data sets it is impossible to interpret such findings. PANSS scores which are based upon the BPRS scale were found to favour clozapine in a single long‐term study, and three short‐term Chinese trials, which included two studies (Li 2003 (Lox), Zhang 2007 (Lox)) that used loxapine as the comparator drug, and is thought to have drug profile similar to atypical antipsychotic drugs.

1.7.2 Negative symptoms Negative symptom score from the SANS scale favoured clozapine group with about a seven point advantage. Again, the clinical significance of such a shift of this magnitude is questionable. We were able to include data from one long‐term study (Rosenheck 1993 (H)) and found that negative symptoms were not significantly different when assessed using the PANSS negative symptoms sub‐score.

1.7.3 Positive symptoms SAPS scores in a single short‐term study (Wang 2001 (CPZ)) failed to reveal any significant differences, although small participant numbers (n=60) limited the possibility of detecting a real treatment effect. Longer‐term PANSS positive data from a larger study (n=235) did favour clozapine in a group of participants who were treatment‐resistant, although the points difference was only about two and the clinical relevance of this is unclear.

1.8 Cognitive functioning Few studies measured cognitive functioning and outcome data were complicated by the use of different scales by single studies making meta‐analyses impossible. We found participants given clozapine had less cognitive impairment (n=82, RR 0.56 CI 0.3 to 0.9, NNT 4 CI 3 to 21). Most other cognitive outcomes were equivocal and were based on small numbers of participants.

1.9 Behaviour Few studies reported usable data for behavioural changes. We were only able to report two studies that measured behaviour using the NOSIE scale and data favoured clozapine. However, only 40 participants were included and more robust data are needed.

1.10 Adverse effects 1.10.1 Blood problems The reason for clozapine being taken off the international market in 1978 had been due to a fatal or potentially fatal drop in white cells in the blood of 16 people in Finland (Idänpään‐Heikkilä 1975). The rate of white blood cell problems (leukopenia) seems to be agreed to be 1.5 to 2% with an increased risk in females and the elderly (Alvir 1993). In the short‐term studies included in this review 16 cases of blood problems from 507 clozapine‐treated individuals were reported, which indicates a blood problem frequency of 3.2%. A relatively high effect size is observed in one Chinese study contributing data to the meta‐analysis on blood problems (Ou 1999 (CPZ)). If this study is excluded, the frequency of blood problems is reduced to 1.9%. Also, twelve of the cases of blood problems occurred in adults (frequency 2.4%) and four occurred in children or adolescents (frequency 40%). Two of the adult cases were in a study of elderly people (frequency 8%). Based on these small but important numbers, clozapine‐induced leukopenia seemed to be more frequent in children and adolescents, and in elderly people. Furthermore, incidences of blood problems were even higher in long‐term clozapine treatment (7%) but were not significantly more frequent than the control group receiving haloperidol (5%). Limited data also suggests that clozapine produces more problems with erythrosedimentation rate and initial increases in white cells.

1.10.2 Other adverse effects People on clozapine experienced significantly more hypersalivation, temperature increase, and drowsiness than those given conventional neuroleptics, but less uncomfortable dry mouth. Over half of those allocated clozapine experienced hypersalivation compared with about one fifth of participants in the control groups. Hypersalivation is a real problem with use of clozapine. It is remarkable in its quantity and very socially disabling. The management of this problem is the focus of another review (Syed 2008).

In assessing the frequency of extrapyramidal adverse effects one has to remember that some trialists (Kane 1988 (CPZ), Lee 1994 (mainly H), Tamminga 1994 (H), Kumra 1994 (H), Rosenheck 1993 (H), Buchanan 1994 (H)) used anticholinergic add‐on medication in the control group to alleviate neurological adverse effects. To this extent the comparisons were biased in favour of the typical neuroleptics. Even with this the clozapine group displayed fewer movement disorders than those treated with the typical neuroleptic drugs.

1.11 Sensitivity analysis The 2008 update of this review included ten trials conducted in China. Chinese trials were not different from other trials in terms of efficacy and adverse effects, despite observed differences in effect size.

2. COMPARISON 2. CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS ‐ TREATMENT‐RESISTANT SCHIZOPHRENIA (Table 2) 2.1 Overall Most findings are based on trials with a total number of participants of 400 to 600. These studies are most difficult to undertake. Nevertheless, that millions of people are now, or have been, treated with this potent drug on the back of data from a few industry‐funded trials reporting limited data for use in everyday life is not ideal and more replication is indicated.

In neuroleptic‐resistant patients, clozapine shows a somewhat greater advantage in controlling symptoms. Participants classified as treatment‐resistant evidenced a significantly better improvement rate with clozapine than with typical pharmacological treatment. The weighted mean difference between short‐term treatments in BPRS total score is about eight points, which probably is a clinically meaningful difference. Treatment‐resistant people did not show any beneficial effect of clozapine on relapse frequency or attrition rates in the short‐term, but the outcomes of long‐term clozapine treatment were more beneficial. The newly included Chinese trials provided no data regarding treatment‐resistant schizophrenia.

3. COMPARISON 3. CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS ‐ CHILDREN OR ADOLESCENTS 3.1 Overall From the limited data we found no differences between clozapine and typical antipsychotic drugs in children for the outcomes of death, relapse, global impression, leaving the study early and mental state. The adverse effects, drowsiness, hypersalivation occurred more frequently in the clozapine group. No significant differences were found for weight gain, movement disorders or fits. All data came from a single study (Kumra 1994 (H)) involving just 21 people. Issues with the frequency of blood dyscrasias in this subgroup are discussed above (1.10.1).

4. COMPARISON 4. CLOZAPINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS ‐ ELDERLY PEOPLE 4.1 Overall We found no significant differences in the outcomes of death, leaving the study early or adverse effects in elderly people. All data came from a single study, Howanitz 1996 (CPZ), which randomised just 42 participants. Issues with the frequency of blood dyscrasias in this subgroup are discussed above (1.10.1).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Randomised clozapine studies have been published since 1974, but the majority have a duration of only four to eight weeks. The severe adverse effect of loss of white blood cells (agranulocytosis) may occur later than during the first four to eight weeks of treatment and may therefore be under‐reported in short‐term studies. Also, deficiencies of global and social functioning caused by schizophrenia may take much longer to improve and any beneficial effect of clozapine may thus be underestimated in short‐term studies.