Abstract

The last 15 years have seen a boom in the use and integration of “-omic” approaches (limited here to genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic techniques) to study neurodegenerative disease in an unprecedented way. We first highlight advances and limitations of using such approaches in the neurodegenerative disease literature, with a focus on Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. We next discuss how these studies can advance human health in the form of generating leads for downstream mechanistic investigation or yielding polygenic risk scores for prognostication. However, we argue that these approaches constitute a new form of molecular description, analogous to clinical or pathological description, that alone does not hold the key to solving these complex diseases.

Keywords: genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, neurodegeneration

The advent of the “-omics” era in neurodegenerative disease research

Advances in technology in the past 15 years have led to a boom in the use of “- omics” (see Glossary) – the large-scale and at times global assessment of a set of biological molecules (genomics for DNA, transcriptomics for RNA, epigenomics for histone or DNA modifications, etc.) with high-throughput technologies – to understand human health and disease. Increasingly, researchers have been relating variation in the genome as well as other “-omes” of growing numbers of individuals to disease state through statistical association, with the goal of better understanding the biological basis for disease. Indeed, the most widespread example of this approach, the genome-wide association study (GWAS) in which common genetic variants are ascertained in individuals with vs. without a given trait, has been employed in hundreds of diseases, resulting in thousands of publications since 2005 [1, 2]. To date, GWAS studies have succeeded in generating leads for downstream mechanistic investigation and therapeutic development, and they have informed the creation of models for predicting disease development among unaffected or high-risk individuals.

The adult-onset neurodegenerative diseases are a subset of diseases with increasing prevalence as our population ages. Although the canonical age-related neurodegenerative diseases – Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Parkinson’s Disease (PD), frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) – differ in their clinical characteristics, they share the underlying feature of progressive degeneration of neurons, causing increasing disability in domains of cognition, motor function, and emotional control. Common to all these diseases is the sad reality that close to no therapies exist to modify disease progression and limited tools exist for early diagnosis and prognosis. In efforts to make headway in this challenging area, high-throughput technologies are increasingly applied to define the “-omic” signatures of these diseases in materials as diverse as single cells of model organisms to human brain tissue obtained from patients at autopsy.

In this review, we discuss advances in the application of “-omics,” specifically genomics, epigenomics, and transcriptomics, to further our understanding of AD, PD, FTLD, and ALS. Specifically, we will review the role of GWAS – the most extensively used genomics study design, albeit not the only form of genomics – in delineating how genetic variation contributes to disease risk, and we will summarize the complementary use of epigenomic and transcriptomic characterization of patient tissues to understand the impact of changes in the DNA regulatory landscape on disease. We highlight common trends and key advances from the application of such technologies to the field while pointing out issues that remain to be addressed. We argue, however, that “-omic” description should be considered a first step in the development of testable hypotheses regarding disease pathogenesis, rather than an “answer” to these devastating diseases. Indeed, genomic, epigenomic, and transcriptomic signatures constitute a form of molecular description, not unlike clinical descriptions that were developed ~200 years ago, or pathological definitions that were developed ~100 years ago for the neurodegenerative diseases. We suggest that, as a field, we need to balance these exploratory descriptive studies with in-depth functional analyses in systems amenable to manipulation, if we are to find meaningful therapeutic avenues for the benefit of neurodegenerative disease patients.

“-Omics” in Neurodegeneration: Where we are now

Since the first successful GWAS, reported in macular degeneration in 2005, over a hundred GWAS for a wide range of diseases have been catalogued by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) [1]. The first GWAS performed in neurodegenerative disease patients – reported in 2005 for PD [3] and 2007 for AD [4] and ALS [5] – had mostly disappointing results, identifying no novel variants that associated with disease groups (vs. neurologically normal control groups) at a genome-wide significant level. These studies failed to find genetic risk factors primarily because they lacked statistical power (employing sample sizes of 550–1550 participants) and assessed fewer genetic variants (200K-550K loci genome-wide) [3–5]. Over time, GWAS in the neurodegenerative diseases have, for the most part, continued to compare genotype frequencies in patients vs. neurologically normal controls. However, they have increased in size: both in the number of genetic variants, usually single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), assessed, and in the sample sizes used – to the point that the most recent GWAS in PD compared ~7.8 million SNPs in >37,000 cases vs. >1.4 million controls [6]. Other strategies – aimed primarily at increasing sample size – have involved grouping diseases known to share a pathologic signature (such as ALS and the form of FTLD known to share inclusions of TDP-43 with ALS) [7] and incorporating “case-by-proxies”(i.e. individuals with a first-degree relative with the neurodegenerative disease in question) [6, 8, 9], although some might question the validity of this “by proxy” approach in diseases with low heritability of liability (h2). One important caveat here is that most samples used for GWAS have come from participants of European ancestry, which might limit the discovery of novel variants or decrease the generalizability of GWAS findings to populations of diverse ancestries.

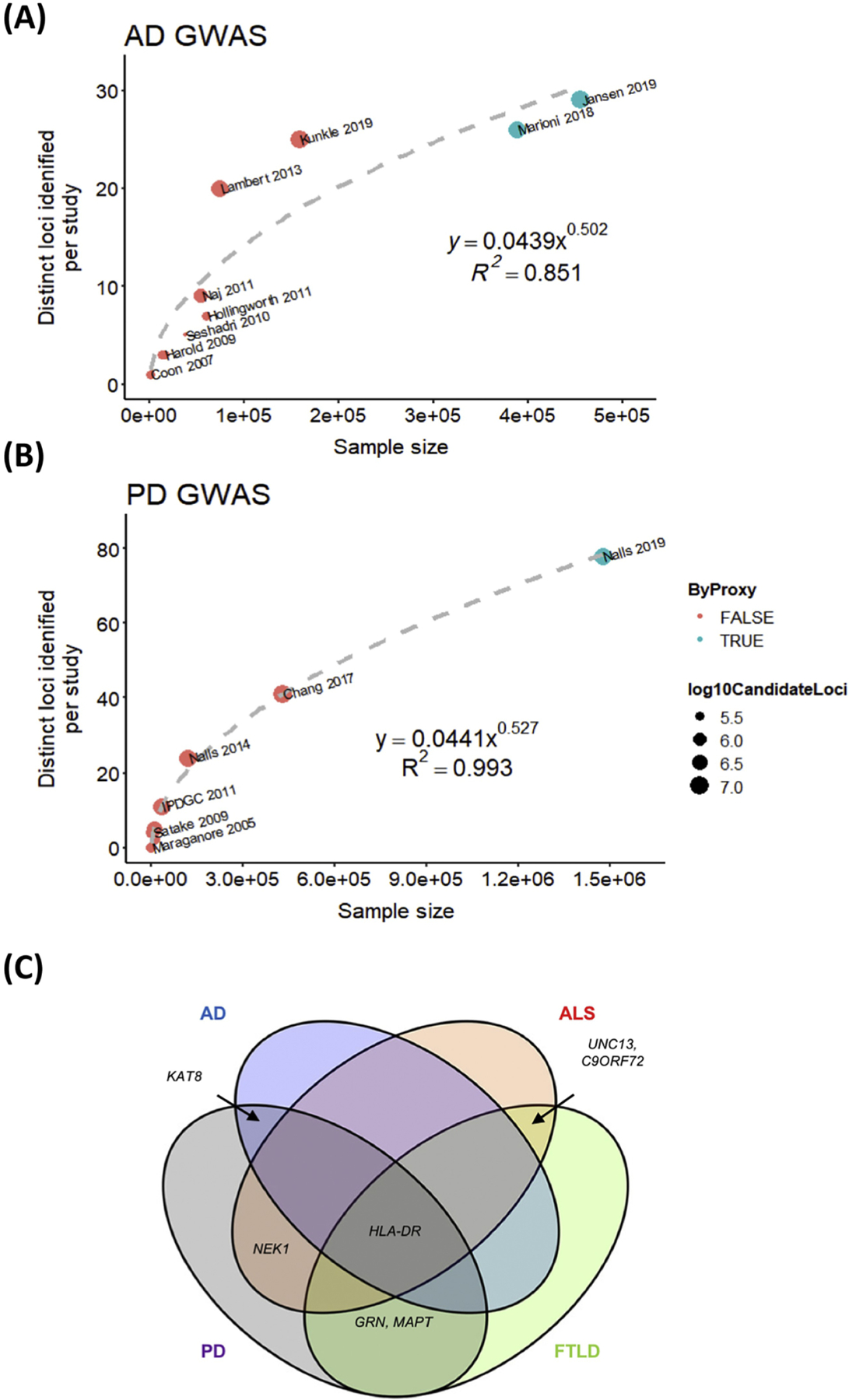

That said, what have we gained from these increasingly large GWAS? As shown in Table 1, as of June 12, 2019, over 1.6 million individuals have been studied, and over 100 variants associated with risk for developing AD, PD, FTLD, or ALS. One thing we have learned in the process is that although increasing sample sizes does lead to an increase in the number of disease-associated variants (DaV) found, this does not appear to translate into a proportional increase in novel insight. For example, a recent AD GWAS reported 94 SNPs reaching genome-wide significance, but 60 of these mapped on to the APOE locus (a risk factor for AD discovered before the advent of GWAS) and only 29 constituted distinct signals [9]. This is in line with the observation that over time increased proportions of GWAS loci correspond to previously-reported rather than novel findings [10]. Furthermore, as can be appreciated in the Key Figure (Figure 1 A–B), the relationship between sample size of the study and number of distinct loci discovered by AD and PD GWAS is at best a power relationship (DistinctLoci~N0.5), suggesting that, although we have not saturated the discovery space, we have reached a point of diminishing returns where larger and larger sample sizes yield fewer novel variants. It is difficult to comment on whether significant gains in the proportion of h2 explained have been achieved over the last 15 years, as earlier GWAS have failed to report this measure consistently. However, from repeated observation that a small number of loci (e.g. APOE in AD) contribute disproportionately to disease risk regardless of the measure, it is likely that major gains in the proportion of h2 explained would also require exponentially increased sample sizes.

Table 1.

Summary of most recent GWAS to date

| Disease | Study | Case (n) | Control (n) | SNPs assessed | Distinct loci discovered | Genetic heritability (h2) of disease | Proportion of h2 attributable to identified loci |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | Kunkle et al (2019) | 57,256 | 101,107 | 9,546,058 (CV)a 2,024,574 (RV)b | 25 (5 novel) | 0.071 (0.0637 without ApoE) | Not reported |

| PD | Nalls et al (2019) | 37,688 case + 18,618 by-proxy | 1,417,791 | 7,784,415 | 78 (37 novel) | 0.22 | 0.16 |

| FTD | Pottier et al (2018) | 592 (GRN+)c 143 (GRN-)c | 2,944 | 7,033,776 | 2 (1 novel) | Not reported | Not reported |

| ALS | Nicolas et al (2018) | 20,806 (GWAS) 1,138 (RVBA)d | 59,804 (GWAS) 19,494 (RVBA)d | 10,031,630 | 6 (1 novel) | Not reported | Not reported |

(CV) = Common variants

(RV) = Rare variants

(GRN+/−) = Granulin mutation positive/negative

(RVBA) = Rare variant burden analysis

Figure 1. Summary of knowledge gained from increasingly large GWAS in neurodegenerative disease research.

A-B) Scatterplots summarizing number of distinct loci discovered for a given sample size for A) AD GWAS [4, 8, 13, 17, 25, 50–55] or B) PD GWAS [3, 15, 18, 21, 56–61]. Each data point corresponds to a study, point color corresponds to whether “by proxy” cases were used, and circle size corresponds to number of candidate loci assessed. Plots were generated in R [62]. C) Venn diagram showing genes implicated across neurodegenerative diseases in part due to GWAS [7, 8, 13, 18, 21, 53, 58, 61, 63].

Besides uncovering genetic risk loci for the various neurodegenerative diseases, GWAS have also led to (sometimes unexpected) insights into the genetic architecture of these diseases. For example, we have learned that the vast majority of neurodegenerative DaV are in non-coding regions [11], suggesting that they influence disease by mechanisms other than a change in protein function based on amino acid change. In some cases, increased understanding of this genetic architecture may suggest alternative strategies for exploration. For example, in ALS, where we now understand that variants with minor allele frequencies (MAF) of 0.01 to 0.1 account for 50% of genetic heritability [12], rare allele burden tests might be considered alongside more conventional GWAS designs. In our opinion, one other important insight gained from the many GWAS performed to date in neurodegeneration concerns the possible shared mechanisms among seemingly unrelated pathologies. This is best exemplified by the implication of common loci like the HLA-DR locus [13–16] across AD, PD, FTLD and ALS (Figure 1 C), as well as the implication of common pathways (such as immune system involvement [14, 17, 18] and lysosomal biology [14, 18]) among GWAS-identified risk loci in multiple neurodegenerative diseases.

Although epigenomic and transcriptomic characterization of patient samples has been less extensive than GWAS, these increasingly popular studies have provided supporting evidence for the role of DaV in regulating gene expression. Two epigenetic marks often studied in this context include histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27Ac) – recognized as a marker of active enhancer regions [19] – and DNA methylation – believed to be involved in repressing transcription of nearby genes [20]. Analyses integrating GWAS and H3K27Ac data have shown enrichment of overlap between genomic regions containing H3K27Ac peaks in the brain and loci that contribute the most to disease heritability in PD [21], AD [9], and ALS [22]. Another study compared H3K27Ac peaks in AD and control brain samples, finding that differentially acetylated peaks were enriched in AD GWAS loci [23]. Similarly, altered DNA methylation patterns near PD DaV have been reported in post-mortem brain tissue from PD individuals compared to controls [15]. Taken together, these epigenomic studies suggest that DaV found by GWAS often affect the genetic regulation of specific target genes. This inference is concordant with studies integrating GWAS data with transcriptomic data, largely generated from tissue samples obtained in healthy controls. Specifically, multiple studies of this type demonstrate that DaV in non-coding regions significantly associate with RNA expression of nearby genes in disease-relevant tissue (i.e. they are expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs)) [18, 21, 24, 25]. Lastly, various studies have used microarray-based [26] and RNAseq [27–32] profiling of postmortem samples from disease patients vs. controls, but these studies, along with similar epigenomic profiling studies, are limited by the fact that the earliest phases and dynamic changes that occur during disease might not be captured in postmortem samples. We also note that, while genetic loci identified through GWAS are more likely to contribute causally to the development of disease, transcriptomic signatures may reflect causal changes driving disease, the biological state resulting from the causal insult, or changes unrelated to causal influences.

Potential applications towards human health

Although GWAS can be useful in various ways, one frequently-promised use lies in the leads these studies may generate for greater mechanistic understanding of disease, and the potential for this greater understanding to translate into new targets for therapeutic intervention. Indeed, follow-up studies of GWAS-generated leads have been undertaken by various groups. One notable example is the functional investigation of the TMEM106B locus, first reported in 2010 to associate by GWAS with risk for FTLD with TDP-43 inclusions (FTLD-TDP) [33]. Since then, FTLD-TDP risk genotypes at the TMEM106B locus have been linked to various outcomes across the various neurodegenerative diseases, including faster rate of cognitive decline in patients already diagnosed with FTLD [34], as well as increased risk for cognitive impairment in ALS [35] and PD [34]. FTLD-TDP risk genotypes at this locus also appear to act as genetic modifiers in important Mendelian subgroups of FTLD, such as carriers of C9orf72 repeat expansions [36] and GRN mutations [37, 38]. DaV at this FTLD-TDP risk locus act as eQTLs for TMEM106B, with risk variants associated with higher expression, through preferential recruitment of the chromatin-regulating protein CTCF and increased CTCF-mediated long-range interactions [39]. TMEM106B encodes a Type II transmembrane protein localized to lysosomes [40], whose increased expression, in turn, results in dose-dependent cellular vacuolarization and lysosomal dysfunction in multiple cell types, including neurons [39, 41]. Thus, a reasonable narrative for the function of this GWAS-nominated FTLD risk locus is that (1) DaV increase expression of the target gene TMEM106B, (2) increased expression of TMEM106B compromises lysosomal function, and (3) lysosomal abnormalities lead to cellular dysfunction and downstream neurodegeneration. Moreover, the genetic modifier effects described at a statistical level among C9orf72 expansion or GRN mutation carriers with FTLD have molecular support in cellular and in vivo studies that demonstrate interactions between TMEM106B and C9orf72 [41], and TMEM106B and GRN [42].

While all these findings are certainly encouraging, we note that after nearly a decade of investigation, the discovery and functional investigation of the TMEM106B locus has yet to result in targeted therapies for FTLD or any other neurodegenerative disease. Thus, even after a successful GWAS followed by active functional investigation, the latter of which occurs with a disappointingly small minority of GWAS-identified risk loci [2], the road to potential translation is a long one.

Another use case for studies based on “-omic” data lies in their potential for predicting disease outcomes, including early prediction of disease development as well as prediction of future disease trajectory. The polygenic risk score (PRS), for example, can be constructed from multiple genetic risk loci, often identified by GWAS, in a study population, in order to predict risk of disease in an independent population. Although PRSs accounting for increasing numbers of DaV have resulted in improved prediction [10], current GWAS-based PRSs still fall short of the predictive accuracy really needed for clinical implementation. In PD, for example, a PRS consisting of 1805 variants had an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.692 [18].

Concluding remarks: Moving past molecular description

In charting a path forward, it may be helpful to consider for a moment the history of our current understanding of the neurodegenerative diseases. We argue that the 1800s represented an era of clinical characterization, resulting, for example, in the description ~200 years ago of a “shaking palsy” by James Parkinson [43]. The early 1900s saw the linking of clinical syndromes to histopathological characterization, with Alois Alzheimer describing the senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that still form the heart of our neuropathological definitions of AD [44], and Frederick Lewy describing the “Lewy bodies” that now characterize PD [45]. While these initial clinical and histopathological characterizations were no doubt important, they did not “solve” their respective diseases. Rather, they were initial observations that were corroborated by many others and extended through subsequent investigations.

We are now in an era of molecular characterization, begun at the single-gene level in the 1990s (when, for example, mutations in SNCA, the gene encoding alpha-synuclein, the main component of Lewy bodies, were shown to cause autosomal dominant forms of PD [46]), and continuing now at the multi-gene/transcript level with the “omics” approaches reviewed here.

As was the case for clinical and pathological characterization of disease, characterization of neurodegenerative diseases with “-omic” techniques can provide useful information. However, as with previous forms of disease characterization, molecular description is more likely to be a first step than an answer.

We have described a detailed framework for moving past GWAS and other forms of molecular disease description previously [2]; here, we highlight “bigger picture” aspects. Specifically, initial molecular description will need replication and confirmation. For well-replicated genetic risk loci, or epigenomic or transcriptomic signatures, integration of different types of data, as well as statistical methods for causal inference such as mendelian randomization, can lead to hypotheses about specific biological pathways and targets to investigate in each disease. For example, one might integrate existing “omic” datasets like GTEx [24], transcription factor binding maps [47], or 3D-genome folding maps [47] to explore whether a DaV impacts disease via modifying target gene expression, transcription factor binding, or long-range chromatin interactions. We believe that to date, most “functional investigations” based on “-omic” datasets tend to end here. We do not believe, however, that they should end here. Rather, functional screens (small molecule, RNAi, or CRISPR-based) in simple model systems should follow these “-omics” and analysis-driven studies, in order to prioritize leads for follow-up in more complex systems (e.g. mammalian models) where specific elements (variant, gene, metabolite, pathway, etc.) should be manipulated, in order to understand ensuing effects. Outside of a screening context, CRISPR-based technologies can also aid in dissecting the function of GWAS-implicated loci by allowing researchers to quickly modify the expression of a potential target gene [48] or edit the specific DaV believed to be causal. Claussnitzer et. al. provide an elegant, early example of the latter approach, using CRISPR-based editing to demonstrate the effect of variation at the non-coding SNP rs1421085 on expression of target IRX3 and IRX5 genes, in turn affecting adipocyte differentiation, with implications for the development of obesity [49].

While nothing in the above paragraph is particularly controversial, we believe that the relative weighting we recommend to efforts along each of these steps may be. Specifically, we argue that GWAS efforts in neurodegeneration have reached a point of diminishing returns, and we suspect that other “-omics” based approaches will reach that point relatively quickly, despite the understandable “wow” factor of the technology that underpins them. Thus, we advocate strongly for a greater emphasis on true functional studies, in systems amenable to manipulation, with the potential to not just generate hypotheses, but rather to prove or disprove them. These types of studies will require collaboration between experts in statistical and computational methods and experts in cell and organismal biology, as well as flexibility and some degree of patience. We believe that only then will we be able to translate the potential afforded by an unprecedented degree of molecular insight into meaningful gains for the many patients suffering from neurodegenerative disease.

Supplementary Material

Outstanding questions box:

How many more disease associated variants remain to be discovered by GWAS in AD, PD, FTLD, and ALS? Is it time to stop performing GWAS altogether? If not, how will we know when it is time?

How do we prioritize >100 candidate GWAS risk loci for the in-depth functional investigation most likely to lead to successful therapeutic development? Can Mendelian randomization or functional screen approaches play a role in this?

How are “omic”-scale approaches to studying RNA and epigenetic signatures likely to contribute to our understanding of neurodegeneration beyond the realization that disease associated variants often affect genetic regulation and gene expression?

What are the best cellular/animal models for studying the involvement of nominated targets and pathways in AD, PD, FTLD, or ALS pathogenesis?

How can we incentivize studying a specific disease-associated variant, gene, or pathway over performing yet another “-omics” based characterization study?

Highlights:

The last 15 years have seen a “boom” in the use of “-omic” technologies to characterize Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD).

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in neurodegeneration have resulted in the characterization of >1 million individuals and the discovery of >100 disease-associated genetic risk loci. However, no targeted therapies (or late-phase clinical trials testing targeted therapies) have emerged from these studies, and we expect diminishing returns from increasingly large GWAS.

Functional investigation of TMEM106B, a genetic risk locus implicated by GWAS in FTLD, exemplifies a path from risk locus to target gene to biological pathway.

Emphasis on the integration of knowledge into specific hypotheses that are then tested in cell biological and animal-based model systems is needed.

Glossary:

- Area under the Receiver Operating Curve (AUC)

Summarizes a model’s accuracy at predicting a given outcome (sensitivity and specificity) across all threshold values

- DNA methylation

Epigenetic marker on DNA associated generally with transcriptional repression

- Epigenome

The full set of epigenetic marks, or reversible modifications (e.g. acetylation and methylation) to DNA or its associated proteins (e.g. histones), involved in regulating the expression of the genome

- Epigenomics

The study of the epigenome (or full set of epigenetic marks) and how modifications lead to normal and abnormal biological function

- Expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL)

A locus at which genetic variation is significantly associated with levels of an RNA transcript in a tissue of interest

- Genome

The full set of DNA of an organism

- Genomics

The study of the sequence and function of the genome or full genetic content of an organism. In medical research, a frequent area of focus is the relationship between disease traits and genetic variation.

- Genome-wide association study (GWAS)

A study analyzing the statistical association between genetic variants, most often single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), across the entire genome and a phenotype of interest (e.g. disease state, endophenotype, non-disease trait such as height)

- Histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27Ac)

Epigenomic histone modification often associated with activation of transcription

- Mendelian randomization

Statistical technique that employs an instrumental variable (such as a SNP) which is assumed to be randomized by nature to establish a causal association between an intermediary (such as RNA or protein levels) and an outcome (such as disease)

- “-Omics”

The study of a group of molecules (DNA, RNA, proteins, metabolites, etc.) in a global or comprehensive way

- Polygenic risk score (PRS)

Statistical model that combines information from multiple genetic loci to predict risk of a specific outcome (most often disease development) in a population

- Transcriptome

The sum of all RNA transcripts in a biosample (can refer to a single cell, a tissue, etc.)

- Transcriptomics

The study of the transcriptome (or the sum of all RNA transcripts)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References Cited:

- 1.MacArthur J, et al. (2017) The new NHGRI-EBI Catalog of published genome-wide association studies (GWAS Catalog). Nucleic Acids Res 45, D896–D901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallagher MD and Chen-Plotkin AS (2018) The Post-GWAS Era: From Association to Function. Am J Hum Genet 102, 717–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maraganore DM, et al. (2005) High-Resolution Whole-Genome Association Study of Parkinson Disease. The American Journal of Human Genetics 77, 685–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coon KD, et al. (2007) A high-density whole-genome association study reveals that APOE is the major susceptibility gene for sporadic late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 68, 613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schymick JC, et al. (2007) Genome-wide genotyping in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and neurologically normal controls: first stage analysis and public release of data. The Lancet Neurology 6, 322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nalls MA, et al. (2019) Expanding Parkinson’s disease genetics: novel risk loci, genomic context, causal insights and heritable risk. bioRxiv, 388165 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diekstra FP, et al. (2014) C9orf72 and UNC13A are shared risk loci for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: A genome-wide meta-analysis. Annals of Neurology 76, 120–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marioni RE, et al. (2018) GWAS on family history of Alzheimer’s disease. Translational Psychiatry 8, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen IE, et al. (2019) Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nature Genetics 51, 404–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marigorta UM, et al. (2018) Replicability and Prediction: Lessons and Challenges from GWAS. Trends in Genetics 34, 504–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuyvers E and Sleegers K (2016) Genetic variations underlying Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from genome-wide association studies and beyond. The Lancet Neurology 15, 857–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Rheenen W, et al. (2016) Genome-wide association analyses identify new risk variants and the genetic architecture of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature Genetics 48, 1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert J-C, et al. (2013) Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Genetics 45, 1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrari R, et al. (2014) Frontotemporal dementia and its subtypes: a genome-wide association study. The Lancet Neurology 13, 686–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nalls MA, et al. (2014) Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nature Genetics 46, 989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M, et al. (2018) A C6orf10/LOC101929163 locus is associated with age of onset in C9orf72 carriers. Brain 141, 2895–2907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen IE, et al. (2019) Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat Genet 51, 404–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nalls MA, et al. (2019) Expanding Parkinson’s disease genetics: novel risk loci, genomic context, causal insights and heritable risk. bioRxiv, 388165 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creyghton MP, et al. (2010) Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 21931–21936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deaton AM and Bird A (2011) CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes & Development 25, 1010–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang D, et al. (2017) A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci. Nature Genetics 49, 1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannon E, et al. (2019) Genetic risk variants for brain disorders are enriched in cortical H3K27ac domains. Molecular Brain 12, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marzi SJ, et al. (2018) A histone acetylome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s disease identifies disease-associated H3K27ac differences in the entorhinal cortex. Nature Neuroscience 21, 1618–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Consortium G, et al. (2017) Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature 550, 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunkle BW, et al. (2019) Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Abeta, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet 51, 414–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooper-Knock J, et al. (2012) Gene expression profiling in human neurodegenerative disease. Nature Reviews Neurology 8, 518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brohawn DG, et al. (2016) RNAseq Analyses Identify Tumor Necrosis Factor-Mediated Inflammation as a Major Abnormality in ALS Spinal Cord. PLoS One 11, e0160520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ladd AC, et al. (2017) RNA-seq analyses reveal that cervical spinal cords and anterior motor neurons from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis subjects show reduced expression of mitochondrial DNA-encoded respiratory genes, and rhTFAM may correct this respiratory deficiency. Brain research 1667, 74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Annese A, et al. (2018) Whole transcriptome profiling of Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease patients provides insights into the molecular changes involved in the disease. Scientific Reports 8, 4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borrageiro G, et al. (2018) A review of genome-wide transcriptomics studies in Parkinson’s disease. European Journal of Neuroscience 47, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett JP Jr., et al. (2019) RNA Sequencing Reveals Small and Variable Contributions of Infectious Agents to Transcriptomes of Postmortem Nervous Tissues From Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Subjects, and Increased Expression of Genes From Disease-Activated Microglia. Frontiers in neuroscience 13, 235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel H, et al. (2019) A Meta-Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Transcriptomic Data. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 68, 1635–1656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Deerlin VM, et al. (2010) Common variants at 7p21 are associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 inclusions. Nature Genetics 42, 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tropea TF, et al. (2019) TMEM106B Effect on cognition in Parkinson disease and frontotemporal dementia. Annals of Neurology 85, 801–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vass R, et al. (2011) Risk genotypes at TMEM106B are associated with cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathologica 121, 373–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallagher MD, et al. (2014) TMEM106B is a genetic modifier of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions. Acta Neuropathologica 127, 407–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cruchaga C, et al. (2011) Association of TMEM106B gene polymorphism with age at onset in granulin mutation carriers and plasma granulin protein levels. Archives of neurology 68, 581–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finch N, et al. (2011) TMEM106B regulates progranulin levels and the penetrance of FTLD in GRN mutation carriers. Neurology 76, 467–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallagher MD, et al. (2017) A Dementia-Associated Risk Variant near TMEM106B Alters Chromatin Architecture and Gene Expression. The American Journal of Human Genetics 101, 643–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen-Plotkin AS, et al. (2012) TMEM106B, the Risk Gene for Frontotemporal Dementia, Is Regulated by the microRNA-132/212 Cluster and Affects Progranulin Pathways. The Journal of Neuroscience 32, 11213–11227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Busch JI, et al. (2016) Increased expression of the frontotemporal dementia risk factor TMEM106B causes C9orf72-dependent alterations in lysosomes. Human Molecular Genetics 25, 2681–2697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klein ZA, et al. (2017) Loss of TMEM106B Ameliorates Lysosomal and Frontotemporal Dementia-Related Phenotypes in Progranulin-Deficient Mice. Neuron 95, 281–296.e286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parkinson J (1817) An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Alzheimer A (1907) Über eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde [article in German]. Allg Z Psych Psych-gerich Med 64, 146–148 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Forster E and Lewy F (1912) Paralysis agitans. Pathologische Anatomie. Handbuch der Neurologie 20, 920–933 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polymeropoulos MH, et al. (1997) Mutation in the α-Synuclein Gene Identified in Families with Parkinson’s Disease. Science 276, 2045–2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis CA, et al. (2018) The Encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE): data portal update. Nucleic Acids Res 46, D794–D801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doudna JA and Charpentier E (2014) The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346, 1258096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Claussnitzer M, et al. (2015) FTO Obesity Variant Circuitry and Adipocyte Browning in Humans. New England Journal of Medicine 373, 895–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harold D, et al. (2009) Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 41, 1088–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hollingworth P, et al. (2011) Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Genetics 43, 429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lambert JC, et al. (2009) Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 41, 1094–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marioni RE, et al. (2019) Correction: GWAS on family history of Alzheimer’s disease. Translational Psychiatry 9, 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naj AC, et al. (2011) Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Genetics 43, 436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seshadri S, et al. (2010) Genome-wide Analysis of Genetic Loci Associated With Alzheimer Disease. Jama 303, 1832–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Consortium I.P.s.D.G. (2011) Imputation of sequence variants for identification of genetic risks for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. The Lancet 377, 641–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fung H-C, et al. (2006) Genome-wide genotyping in Parkinson’s disease and neurologically normal controls: first stage analysis and public release of data. The Lancet Neurology 5, 911–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hamza TH, et al. (2010) Common genetic variation in the HLA region is associated with late-onset sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet 42, 781–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pankratz N, et al. (2012) Meta-analysis of Parkinson’s Disease: Identification of a novel locus, RIT2. Annals of Neurology 71, 370–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Satake W, et al. (2009) Genome-wide association study identifies common variants at four loci as genetic risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Nature Genetics 41, 1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simón-Sánchez J, et al. (2009) Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson’s disease. Nature Genetics 41, 1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Team RC (2016) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gratten J, et al. (2017) Whole-exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis suggests NEK1 is a risk gene in Chinese. Genome medicine 9, 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.