Abstract

Purpose:

Laparoscopic fundoplication is now a cornerstone in the treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) with sliding hernia. The best outcomes are achieved in those patients who have some response to medical treatment compared to those who do not. Robotic fundoplication is considered a novel approach in treating GERD with large paraesophageal hiatal hernias. Our goal was to examine the feasibility of this technique.

Methods:

Seventy patients (23 males and 47 females) with mean age 64 y old (22–92), preoperatively diagnosed with a large paraesophageal hiatal hernia, were treated with a robotic approach. Biosynthetic tissue absorbable mesh was applied for hiatal closure reinforcement. Fifty-eight patients underwent total fundoplication, 11 patients had partial fundoplication, and one patient had a Collis-Nissen fundoplication for acquired short esophagus.

Results:

All procedures were completed robotically, without laparoscopic or open conversion. Mean operative time was 223 min (180–360). Mean length of stay was 38 h (24–96). Median follow-up was 29 mo (7–51). Moderate postoperative dysphagia was noted in eight patients, all of which resolved after 3 mo without esophageal dilation. No mesh-related complications were detected. There were six hernia recurrences. Four patients were treated with redo-robotic fundoplication, and two were treated medically.

Conclusions:

The success of robotic fundoplication depends on adhering to a few important technical principles. In our experience, the robotic surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease with large paraesophageal hernias may afford the surgeon increased dexterity and is feasible with comparable outcomes compared with traditional laparoscopic approaches.

Keywords: gastroesophageal reflux disease, robotic total fundoplication, robotic partial fundoplication, paraesophageal hiatal hernia, biological absorbable mesh

INTRODUCTION

There has been significant improvements in laparoscopic surgery since its inception in the early 1990s.1 Today almost any traditionally open surgery in the abdomen or chest can be performed using minimally invasive principles with equivalent or better outcomes. Laparoscopic total fundoplication has been proven to be efficacious, providing sustainable relief in treating severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and reducing small and large hiatal hernias.2 The indication for surgical treatment of GERD is accepted for patients who respond to medical treatment, rather than treating those who are unresponsive.3 In our practice, we prefer to select clinical responders with sliding hiatal hernia to perform a total versus partial fundoplication based on the results of esophageal function tests.4 The presence of a large paraesophageal hiatal hernia, classified as a herniation of 30% of the stomach into the chest, represents most patients in our practice. This anatomical and physiologic abnormality is an indication for intervention alone, independent of a patient's response to medications. A recent meta-analysis showed that partial compared with total fundoplication is more successful in the treatment of GERD with less postoperative dysphagia.5 Conversely, total fundoplication is more efficacious in controlling GERD symptomatology, compared with partial fundoplication, regardless of the impairment of esophageal motility detected by the preoperative esophageal function tests.2 We align with the latter theory, focusing our efforts in creating a more durable result with a total fundoplication. We limited partial wraps to patients with primary motility disorders like scleroderma or esophageal achalasia, and, more recently, elderly patients with large paraesophageal hiatal hernia in whom preoperative esophageal function tests are not performed. To avoid postoperative dysphagia, the total fundoplication is performed over a bougie dilator of different sizes, tailoring the surgical treatment for each patient, individually.

Whereas there has been significant improvements in laparoscopic instruments over the years, they are still limited in their ability to perform surgery in tight spaces or challenging angles. Those limitations make traditional minimally invasive antireflux surgery challenging, particularly in the treatment of large paraesophageal hiatal hernias. The recent introduction of robotic surgery reduces those limitations by granting the user increased dexterity of movements with the advent of wristed instruments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective study was authorized by the Research Oversight Committee at Riverside Community Hospital under Hospital Corporation of America with file number RCH-42.

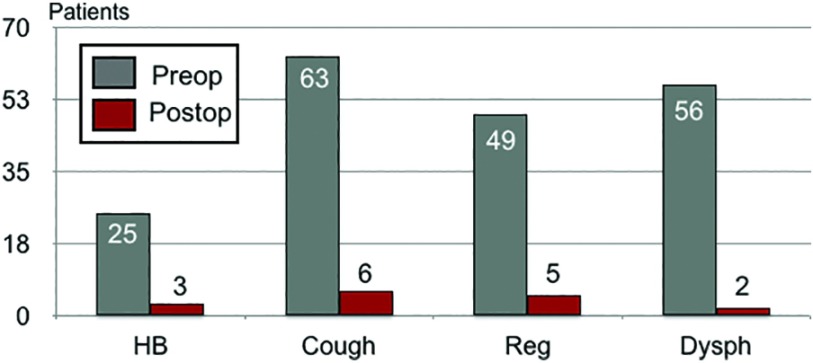

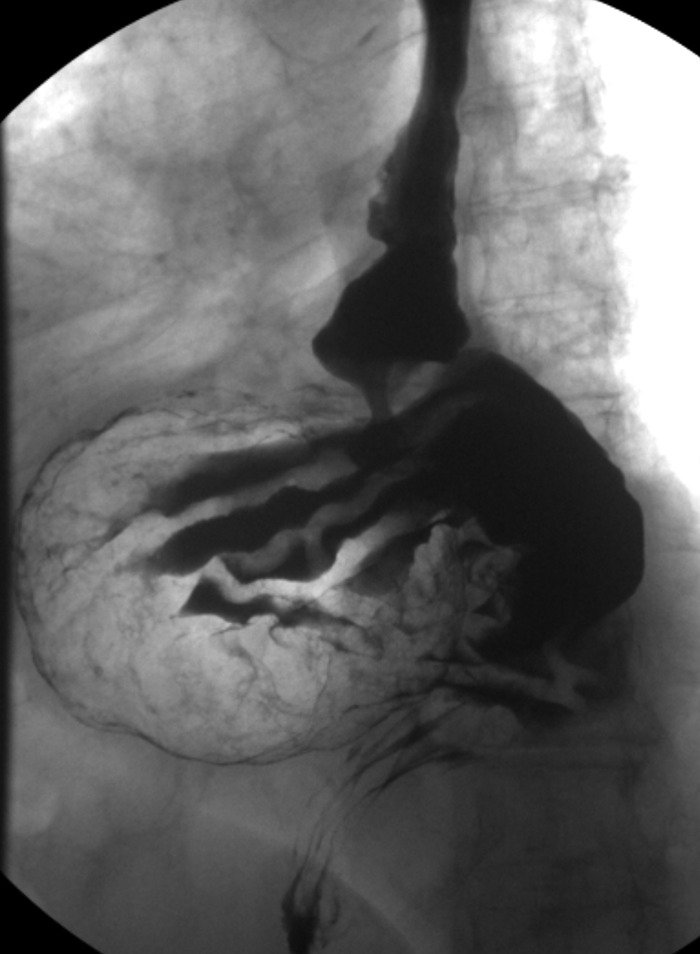

Between March 2014 and June 2018, 110 patients (37 males and 73 females), mean age of 63 y old, (22–92) with diagnoses of GERD and hiatal hernia, were treated with robotic fundoplication. Of those, 25 patients were classified as GERD and type I sliding hiatal hernia, while 15 patients underwent robotic REDO fundoplication for failure of previous laparoscopic antireflux surgery. The remaining 70 patient (23 males and 47 females), mean age 64 y old, (22–92) were diagnosed with large paraesophageal hiatal hernia with more than 30% of stomach herniated into the chest.6 Twelve patients with noncardiac chest pain were referred to us. Preoperatively, heartburn was present in 25 patients, cough in 49 patients, regurgitation in 63 patients, and dysphagia for both solids and liquids in 56 patients. In addition, seven patients were referred with atrial fibrillation that the cardiologists who believed the symptomatology was secondary to their large paraesophageal hiatal hernia. All patients were scheduled to undergo robotic fundoplication. All patients underwent preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy and upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) (Figure 1). Thirty-six patients underwent esophageal manometry and 24-h pH monitoring studies. Computerized tomography scan of chest was obtained in 20 patients (Figure 2). Eleven patients presented at emergency department with obstructive symptoms secondary to an axial rotation and gastric volvulus in eight patients and Cameron ulcer in three patients. We routinely used biosynthetic mesh for reinforcement of the diaphragmatic crura (GORE BIO-A, Flagstaff, AZ). Biosynthetic mesh reinforcement was utilized in 63 patients. Early in the experience, seven patients (10%) did not have mesh placement after closing the hiatus. We describe the operative technique in detail, emphasizing all the important technical elements.

Figure 1.

Upper GI series showing a large type III paraesophageal hiatal hernia.

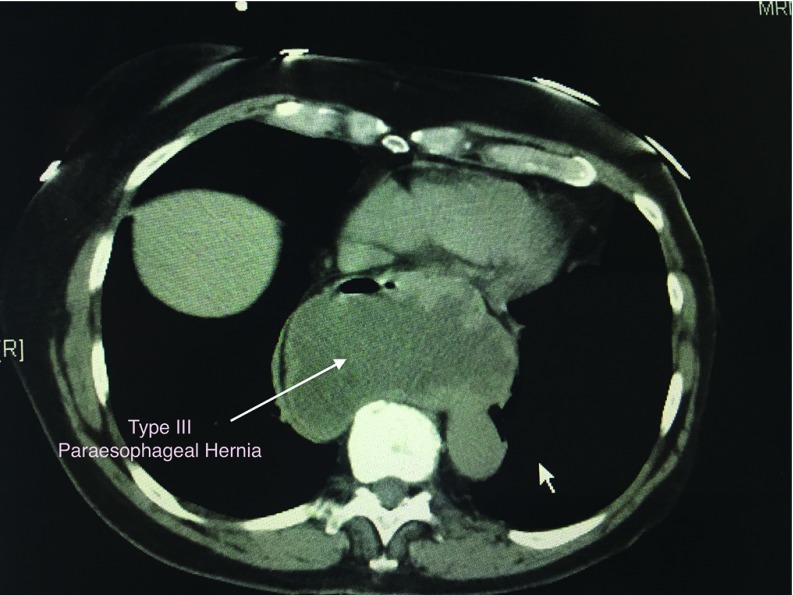

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan of the chest showing a large type III paraesophageal hiatal hernia.

Operative technique

Patient preparation.

After induction of general endotracheal anesthesia, the patient is placed in steep reverse Trendelenburg. A foley is utilized. The Da Vinci Robot (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) is docked above the head (Si model) or at left hip area (Xi model). A nasogastric tube is placed to help to decompress the stomach during surgery. A bougie dilator (50 to 54 French) is placed in the middle third of the esophagus, awaiting advancement into the stomach at the time of the fundoplication technique. The nasogastric tube is removed postoperatively.

Laparoscopic access

Initially, with the patient in supine position, a 5-mm Optiview trocar (Applied Medical Inc., Rancho Santa Margarita, CA) is placed in the right upper quadrant with a 0-degree scope. Pneumoperitoneum is set at 14 mm Hg. A 150-mm-long, 12-mm balloon trocar (Si model) or the new 8-mm trocar (Xi model) is placed 13 cm inferior from the xiphoid process for the robotic camera (30 degrees), an 8-mm robotic trocar in the left upper quadrant, and a 12-mm balloon trocar in the left lower quadrant for laparoscopic assistance. The initial 5-mm port is then upsized to an 8-mm robotic trocar. A laparoscopic Nathanson retractor (Mediflex Surgical Products, Islandia, NY) is introduced in the epigastrium to lift the left lateral segment of the liver to provide excellent exposure to the hiatus. The Nathanson is anchored to a flexible laparoscopic holder (Thompson Surgical Instruments, Traverse, MI) and a post along the patient's right side. An additional 5-mm assist port is placed in the right lower quadrant. Figure 3 shows our ideal port placement. Of note, it is important to maintain at least 12 cm distance between the robotic trocars and the robotic camera port to avoid robotic arm collisions during the surgery.

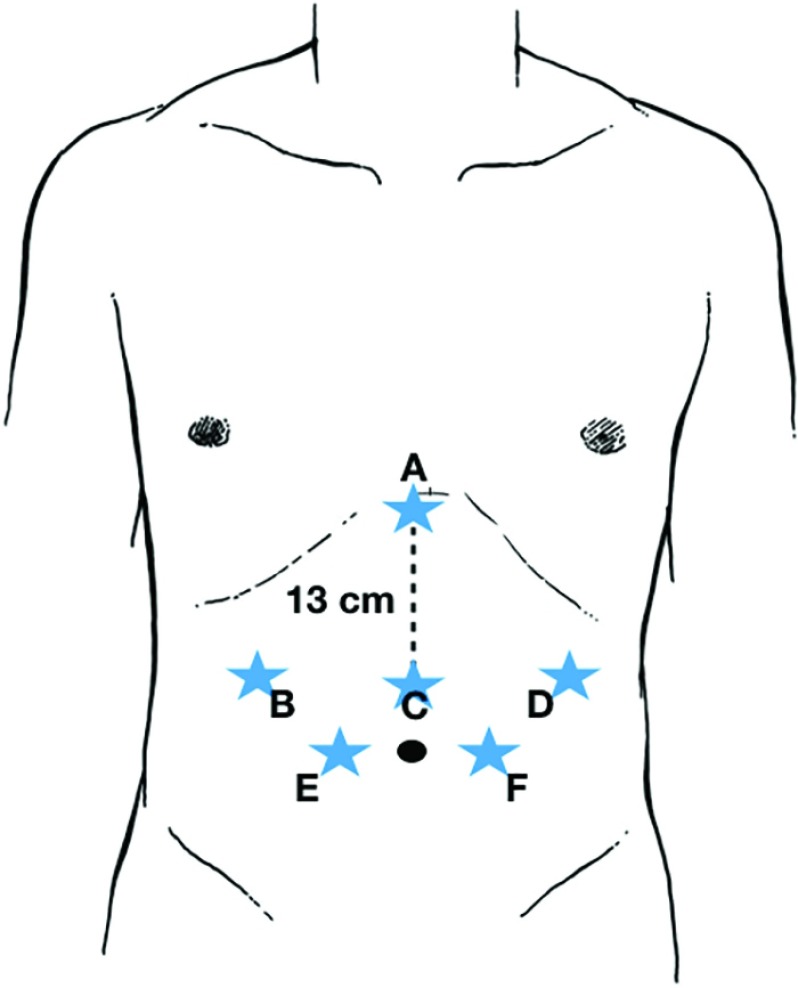

Figure 3.

Robotic accesses for the robotic fundoplication. A: Liver retractor. B and D: Robotic arms. C: Robotic camera. E and F: Assistant ports (the pentagon scheme).

Robotic equipment

Our preferred robotic equipment for the procedure includes an Ultrasonic device, a bipolar grasper, a Cadiere grasper, a Suture Cut needle driver and, intermittently, the monopolar hook device for fine dissection. The operation is continued robotically after docking the robot to the patient.

Steps of the operation

Step 1: division of the gastrohepatic ligament, isolation of the right crus, and identification of the posterior vagus nerve.

Figure 4 shows a typical robotic view of a large hiatal hernia. The operation is started by dividing the gastro-hepatic ligament while preserving the replaced left hepatic artery, when present. The two initial robotic instruments are the bipolar grasper for arm 2 and an ultrasonic device for arm 1. The camera is placed in 30-degrees-down configuration. The ultrasonic device provides for safe division of the tissue avoiding any collateral damage to the surrounding tissues based on its minimal lateral thermal spread of the ultrasonic waves. The ultrasonic device is utilized throughout the entire procedure. When present, the accessory left hepatic artery can be sacrificed if there is a need for further exposure. It is mandatory to recognize the posterior vagus nerve, once the large paraesophageal hiatal hernia is reduced into the abdomen, to avoid permanent damage and severe postoperative gastroparesis.8 In the presence of large hiatal hernias, it is preferable to divide the hernia sac at the level of the right crus level once the crus is identified (Figure 5). This maneuver allows successful dissection of the hernia sac and mobilization of the right portion of the hernia down to the abdomen without undue tension on the reduced stomach.

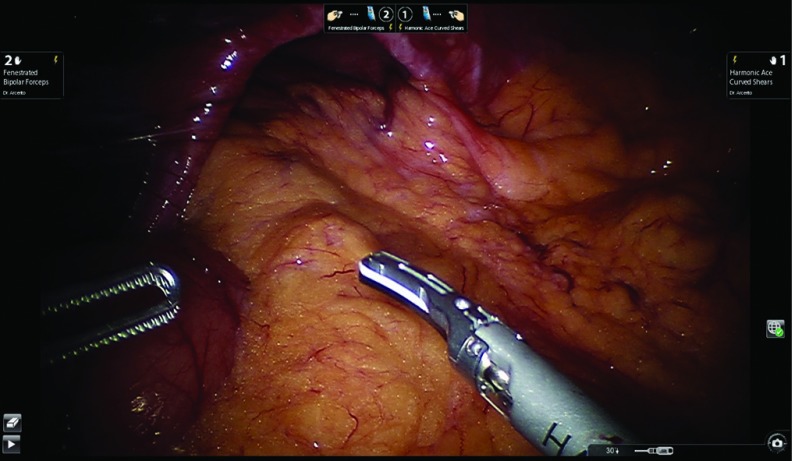

Figure 4.

Robotic view of a large hiatal hernia.

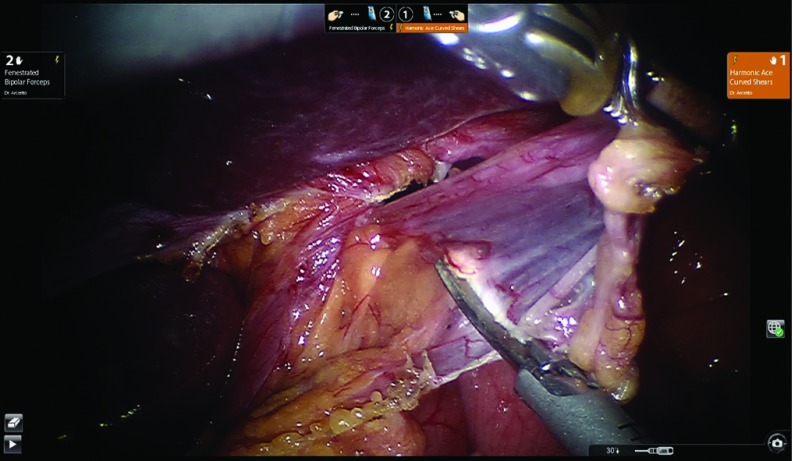

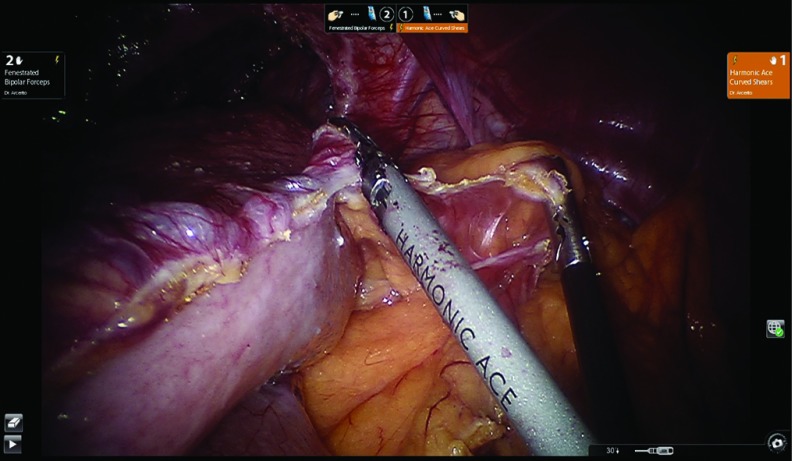

Figure 5.

The hernia sac is divided at the right crus level once the crus is identified.

Step 2: mobilization of the phrenoesophageal membrane with mobilization of the left crus and recognition of the anterior vagus.

The phrenoesophageal membrane is divided. The dissection of the hernia sac at this level is continued toward the upper portion of the left crus. Again, this maneuver allows a successful dissection of the intrathoracic hernia sac at the stomach level, reducing the stomach into the abdomen. The upper portion of the left crus is then exposed. The anterior vagus nerve needs to be identified once the entire stomach is reduced into the abdomen to avoid its damage. The dissection follows the length of the left crus, mobilizing the hernia sac away and further reducing the stomach down to the abdomen. At this point of the operation, traction on the stomach wall sometimes causes serosal tears or gastric perforation, which can be easily repaired using intracorporeal stitches. In our experience, this event occurred twice with successful robotic repair, without a need for open conversion.

Step 3: division of the short-long gastric vessels in giant hiatal hernias.

We believe this step is of paramount benefit in mobilizing the stomach with great exposure of its posterior wall.9 This maneuver can be easily accomplished using the robotic ultrasonic device. The division of short gastric vessels provides the reduction of the greater curvature and the posterior wall of the stomach, exposing the pancreas. Figure 6 shows the division of the short gastric vessels. There is almost always a posterior fatty hernia sac behind the stomach that needs additional resection to avoid possible postoperative recurrences of hiatal hernias. Going behind the posterior wall of the stomach, we isolate the left crus of the diaphragm, which joins the right crus and, indirectly, creates the retroesophageal window, once the entire stomach is reduced into the abdomen. One of the possible complications is tearing the short gastric vessels during their mobilization. Careful use of the ultrasonic device dramatically reduces this event. The robot technique provides excellent exposure of the left upper quadrant during this step of the surgery.

Figure 6.

Division of the short gastric vessels.

Step 4: creation of the retroesophageal window and completion of the resection of the hernia sac.

The reduction of the posterior gastric wall from the chest to the abdomen allows us to create a wide retroesophageal window. A Penrose drain is placed to retract the distal esophagus. The anterior and posterior vagus nerves are always identified and protected. It is advisable, after retracting the distal esophagus, to remove the fat pad at the gastroesophageal junction. In addition, this maneuver helps to resect the final adhesions at the distal third of the esophagus, lengthening it enough to build the fundoplication in the abdomen without tension. The final attachments between the esophagus and the right and left crus are divided. Figure 7 shows the completion of the retroesophageal window and the open diaphragmatic crus.

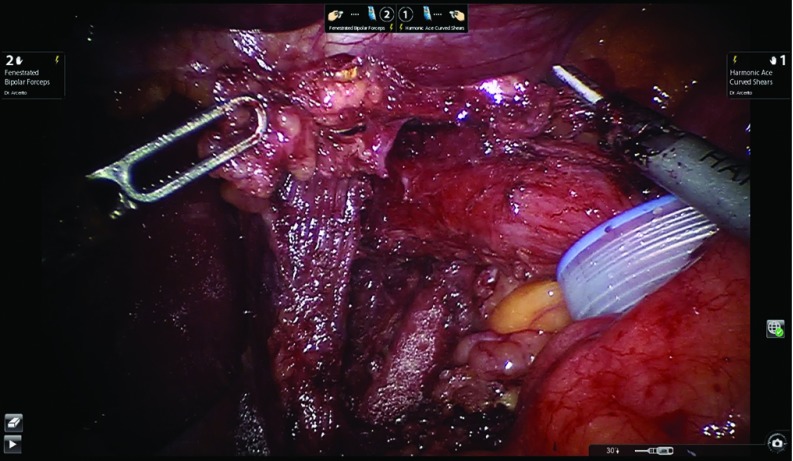

Figure 7.

Completion of the retroesophageal window and the open diaphragmatic crus.

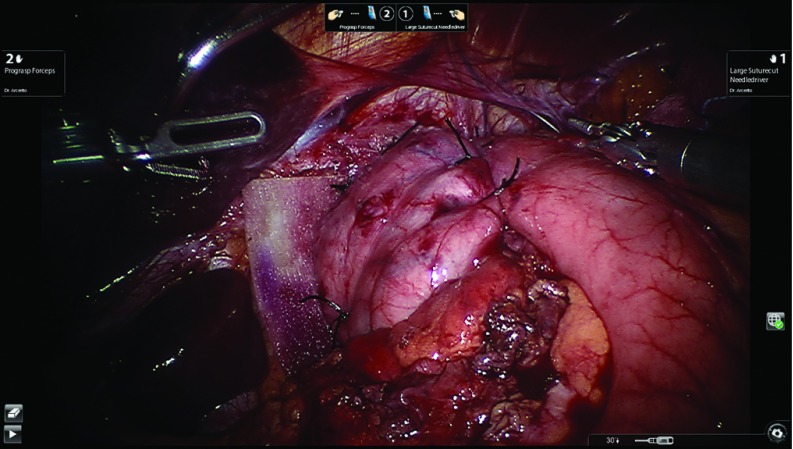

Step 5: closure of the diaphragmatic crura and placement of absorbable mesh.

Usually in large hiatal hernias, it might be difficult to close the right and left crus based on the chronicity of the disease and the distance between the diaphragmatic pilasters. In our experience, with only one exception, the diaphragm was closed successfully. This tension free closure might be due to the thorough dissection of the hernia sac, laterally and posteriorly. The ultrasonic device is then substituted by the Da Vinci Mega Suture Cut Needle Driver. Three stitches of 2–0 silk are placed. The first stitch is placed at the junction of the right and left crus. The distance between the remaining stitches is 1 cm and the final distance between the most superior stitch and the posterior wall of the esophagus needs to be at least 1 cm. Figure 8 shows the completed closure of the diaphragmatic crura. A released cut to the left diaphragm was performed in one patient with subsequent successful closure of the crus. In all but seven patients with large hiatal hernias, a GORE Bio-A Tissue reinforcement is placed (Gore, Flagstaff, AZ). Made with absorbable material, this mesh degrades in vivo through hydrolysis and is fully absorbed within 3–6 mo. The U-shaped mesh allows a tissue reinforcement over the closed crura without compromising the passage of the distal esophagus into the abdomen. Several stitches of 2–0 silk are placed to anchor the mesh around the right and left crus and behind the esophagus to avoid potential posterior gastric hernia recurrence. Figure 9 shows the final position of the Bio-A mesh over the closed crura before performing the fundoplication.

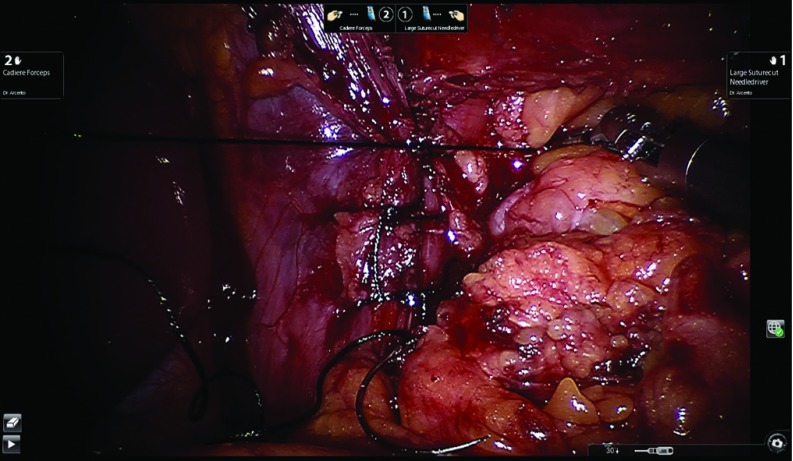

Figure 8.

Completed closure of the diaphragmatic crura.

Figure 9.

Position of the BIo-A mesh over the closed crura before performing the fundoplication.

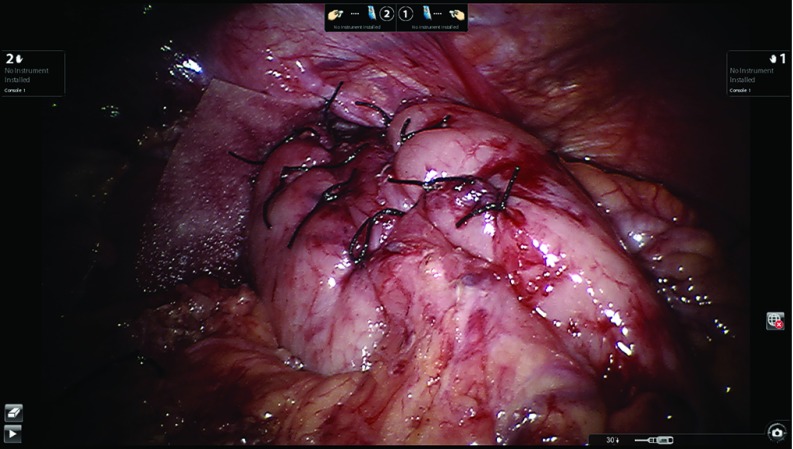

Step 6: creation of fundoplication after insertion of a Bougie dilator.

Using the retroesophageal window, the posterior wall of the gastric fundus is pulled over to create the fundoplication. The two edges of the stomach are maneuvered back and forth to detect tension and to ensure the right side of the fundus to stays in place. The complete dissection of the short gastric vessels and the posterior wall of the stomach determines the success of this step. Furthermore, the presence of the short gastric vessels in the right portion of the fundoplication shows its absence of tension, minimizing the chance for postoperative dysphagia and gas bloating in our patients.9 We then ask our anesthesiologist to advance the bougie, previously placed in the middle third of the esophagus, into the gastric lumen, stopping with any sign of resistance. One of the most serious complications is bougie penetration of the esophageal wall. If this is the case, it is mandatory to convert the procedure and to assess the damage at mucosa and muscle level and repair it. To avoid any resistance, we always cut the suture holding the Penrose to allow a straight passage of the bougie from the distal esophagus to the stomach. Once the bougie is positioned, the fundoplication is created. We always favor the total fundoplication versus the partial one, limiting the latter to patients with preoperative diagnosis of severe esophageal motility disorders, like scleroderma or primary esophageal achalasia.2 The fundoplication is about 3 cm in length. The first 2–0 silk stitch closes the two flaps of the fundus without incorporating the esophageal wall. This maneuver allows us to move the fundoplication proximally above the gastroesophageal junction and then two more stitches are place about 1 cm apart including both fundus flaps and the anterior wall of the esophagus. The bougie is then removed by the anesthesiologist. Three more stitches are placed to anchor the fundoplication into the abdomen. Specifically, two coronal stitches including the diaphragm, the esophagus, and the fundus at right and left upper corners are placed to counteract the cephalic forces that might draw the fundoplication into the chest. An additional stitch is placed between the right fundus flap and the mesh/closed crura to counteract the twisting motion of the fundoplication back to the left upper quadrant. Figure 10 shows the completed total fundoplication. After completing the fundoplication, intraoperative upper endoscopy is performed to confirm the integrity of the fundoplication and absence of stricture at the gastroesophageal junction level.

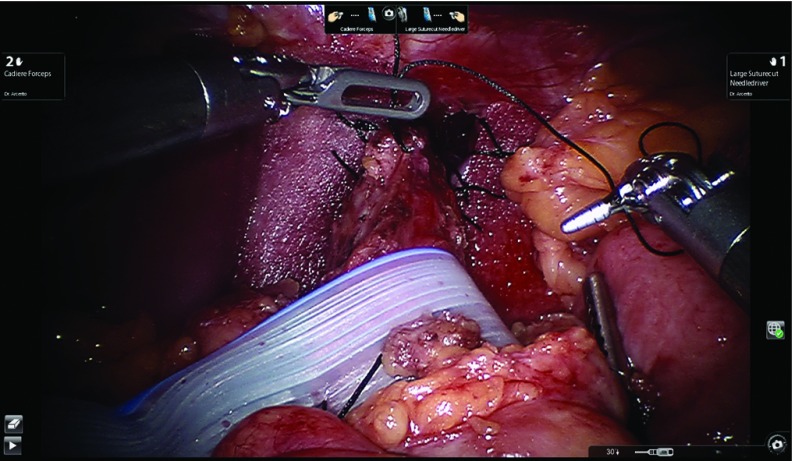

Figure 10.

Completed total fundoplication.

Step 6 bis—partial fundoplication.

In the presence of severe impairment of esophageal peristalsis, we prefer the posterior partial fundoplication (240 to 270 degrees).10 The right fundic flap is aligned to the right side of the intraabdominal esophagus. We still request the anesthesiologist to advance the bougie (48 or 52 french) into the stomach before completing this step. Once the bougie is successfully advanced, the posterior fundoplication is built. Three stitches are placed along the right fundic flap and the esophagus without involving the anterior vagus nerve. The upper stitch includes the diaphragm and the esophagus as a coronal technique. The same sequence is used to build the left fundic flap to the esophagus. As in the total, the partial fundoplication is completed with an additional stitch, which is placed between the right fundic flap and the mesh/closed crura to counteract the twisting motion of the fundoplication back to the left upper quadrant. Figure 11 shows the completed partial fundoplication.

Figure 11.

Completed partial fundoplication.

Table 1 shows all the technical elements we always apply during our robotic technique in the setting of large giant hiatal hernias.

Table 1.

Technical Elements of Robotic Fundoplication for Large Paraesophageal Hiatal Hernia

| Elements |

| Reduce the hernia sac from the hiatus, not from the mediastinum |

| Take down the short gastric vessels |

| Mobilize the entire stomach, including the posterior gastric wall |

| Bougie size |

| Close of the diaphragmatic crura |

| Placement of biosynthetic absorbable mesh |

| Type of fundoplication (total versus partial) |

| Length of fundoplication |

| Space between the fundoplication and the esophagus |

| Anchoring the fundoplication to the esophagus |

| Anchoring the fundoplication to the diaphragm |

RESULTS

All patients were completed robotically. Fifty-eight patients underwent total fundoplication, 11 patients underwent partial fundoplication and one patient required Collis-Nissen fundoplication for an acquired short esophagus. We were able to achieve a sufficient abdominal length of the distal esophagus in almost all cohort of patients. We believe the complete removal of the hernia sac and taking down all the fibrotic adhesions between the distal third of the esophagus and the surrounding hiatal hernia structures helped us to achieve this result. Biosynthetic absorbable mesh was applied to reinforce the crura closure in all patients but the first seven patients in our earlier experience. In the first few patients, we noticed absence of tension at the diaphragmatic level after completing the crura closure. Additional concurrent robotic procedures included two Morgagni hernias repaired with mesh, one cholecystectomy, one excision of gastric leiomyoma, two ventral hernias repaired with mesh, one umbilical hernia repair with mesh, two unilateral inguinal hernias repaired with mesh, and one bilateral inguinal hernia repaired with mesh. Mean operative time was 223 min (180–360), considering docking time to undocking time. Intraoperatively, we experienced two gastric perforations while mobilizing the large hiatal hernias. Both perforations were repaired in double-layer suture using the robotic platform. One patient experienced intraoperative right pneumothorax, which was initially controlled by our anesthesiologists and subsequently required a placement of chest tube at the end of the procedure. No intraoperative blood transfusions were required and no anesthesia complications were experienced. In addition, no intraoperative or perioperative mortality were recorded. After a brief stay in the recovery unit, all patients were admitted for an overnight stay. A clear liquid diet was resumed the evening of the operation and the patient was kept on full liquid diet for the following 2 weeks before advancing to regular diet. Among our 70 patients with large giant hiatal hernias, 90% were discharged after 24 h from surgery, whereas the remaining 10% went home after 48–96 h. Patients were asked to be followed-up clinically at 14 d, 30 d, 3 mo, 6 mo, and yearly after surgery. UGI series were ordered at 6 mo and 1 y postoperatively, regardless of their symptomatology. Only 43 patients were studied with this methodology based on their agreement and their insurance authorization. Three patients experienced bilateral pulmonary emboli, presenting as chest pain and acute shortness of breath, while in the hospital. Pulmonary emboli were confirmed by computed tomography angiography of the chest and treated without further sequelae. One patient required an emergent exploratory laparotomy for postoperative bleeding at 72 h. Two patients were diagnosed with postoperative rapid atrial fibrillation at 2 and 3 d after surgery, and they converted to sinus rhythm after medical intervention. Figure 12 shows the clinical outcome of our patient population at the median follow-up of 29 mo (7–51). Eight patients experienced mild dysphagia for solid foods for an average of 12 wk after surgery. Eventually, all patients resolved it without the need for esophageal dilation. No patients experienced persistent de novo dysphagia at the 6-mo follow-up. Eighty per cent of patients experienced severe dysphagia preoperatively, which resolved postoperatively in 94% of them at follow-up. These results are comparable with an earlier series examining laparoscopic antireflux surgery.11 Six patients (8.5%) recurred. Four were symptomatic and they were treated with redo-robotic fundoplication with additional mesh placement. Three of the four patients were converted to open approach because of severe scar tissue around the hiatus, probably secondary to the fibrotic reaction created by the absorbable mesh. Based on the difficult anatomy, one patient underwent wedge resection at the fundus level with an anterior fundoplication and gastropexy as final approach. The remaining three patients had a concurrent gastropexy in addition to the fundoplication. The other two asymptomatic patients were found to have a small hiatal hernia by UGI series, and they are currently being followed up clinically, with only medical intervention.

Figure 12.

Clinical outcome at 29 mo median follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Robotic surgery is gaining major popularity in treating more complicated cases in the gastrointestinal surgical arena, including cholecystectomy, colectomy, splenectomy, gastrectom,y and pancreatectomy. The benefit of minimally invasive surgery to treat gastroesophageal reflux and sliding hiatal hernia has been established.2 We recently published our robotic experience in treating gastroesophageal reflux disease associated with sliding hiatal hernia or paraesophageal hernias, obtaining excellent clinical outcomes.13 We focused on the strict application of surgical steps that, if followed, they should help the surgeon to obtain excellent outcome, minimizing intraoperative and postoperative complications. We also underlying the role of the robotic platform to treat successfully more complicated foregut surgeries, like large paraesophageal hernias. This prospective review focuses on robotic surgical repair of large paraesophageal hernia providing the role of those surgical principles and proving their importance in obtaining excellent clinical outcome in a longer follow up (median 29 mo). There have only been a few reports examining robotic fundoplication and paraesophageal hernia repair in the last decade.14–16 Our prospective experience compares well with those robotic reported series focusing on safety and feasibility of large paraesophageal hernia repair. To the best of our knowledge, antireflux surgery is the only general surgery application of robotic technique for which class I evidence is available. There are a few studies comparing robotic versus laparoscopic fundoplication for GERD and hiatal hernia repair.17–25 We advocate of the use of total versus partial fundoplication. Regardless of the type of fundoplication, a thorough preoperative assessment is critical to delineate a patient's anatomy and subsequently, ideal treatment.9 This evaluation includes preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy, UGI series, esophageal manometry, and 24–48 h pH monitoring study to select what kind of fundoplication should be performed. Large paraesophageal hiatal hernias represent most our patients with or without GERD in our clinical practice, and several patients have also presented acutely with severe chest pain and dysphagia secondary to gastric volvulus and organo-axial rotation of the stomach in the chest. In those patients, preoperative workup included esophagogastroduodenoscopy and computed tomography scan of the chest. This predominance, in our community practice, suggests the possible evolution of small sliding hiatal hernias when treated with only proton pump inhibitors becoming giant hiatal hernias over several years. The use of the biosynthetic absorbable mesh was decided intraoperatively. In our prospective series, seven patients did not require the utilization of the mesh because of the absence of tension in closing the diaphragmatic pilasters after reducing the stomach into the abdomen. The remaining 63 patients required a U-shape mesh placement for reinforcement, and now it became our standard of practice. We did not experience any mesh related complications at 29 mo median follow-up. Stadlhuber et al. described mesh related complications in laparoscopic antireflux surgery, but the utilized mesh was synthetic.26 Our mesh is absorbable over a relatively short period (3–6 mo). We believe the absence of mesh related complications is due to its absorbable property. Similar results were recently published by Dr. DeMeester's group using NoneCross-linked human dermal mesh27 or Phasix Sepra-Technology (Phasix-ST mesh).28 Oelschlager et al. reported the longest follow up after using biological mesh for large paraesophageal hiatal hernia.29 Unfortunately, their results proved that the benefit in reducing large hiatal hernia recurrence diminishes at long-term follow-up. We plan on long-term follow-up for our patients to detect remote recurrence. One limit of our prospective experience is the relative short follow-up with the mesh reinforcement. We need longer follow-up to identify any potential long-term effect of mesh use and the clinical outcome of our robotic experience.

We did not experience any mortality in our group. One patient experienced a right pneumothorax, which was successfully treated with chest tube placement. Our postoperative complications (10%) included three bilateral pulmonary emboli, two new onset of atrial fibrillation and severe urinary retention, a delayed hemoperitoneum detected 3 days after surgery. All complications were treated successfully. These rates are comparable with a large reported series examining standard laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair.30 Most our patients were elderly (above 65 y old), We reviewed their intraoperative experience, postoperative course, and clinical outcome, and we proved that age should not be a limiting factor in treating large paraesophageal hernia.31 In the recent past, patients with acutely symptomatic paraesophageal hernia were treated with open surgery. In our practice, we have been able to offer to these acutely ill patients robotic surgery in an expedited fashion, usually within 24 h of admission. We believe an established robotic program in the hospital is behind this prompt intervention. This expedited surgical intervention might explain the absence of intraoperative or perioperative mortality in our patient population. This strategy was confirmed by other groups in recent reports.32,33

We experienced six recurrences in our series (8.5%). Four patients underwent attempted robotic approach with REDO fundoplication, closure of the hiatus, new mesh placement and concurrent gastropexy. Three patients were converted to open procedure due to severe scar tissue between the hiatus and the disrupted fundoplication. We believe the previous presence of the mesh made the REDO operation very challenging and lengthening, leading to our higher conversion rate.34 These data were not reported previously in REDO fundoplication literature. The other two patients were found with recurrent hiatal hernia by routine upper gastrointestinal series ordered at 1 y and 18 mo in follow-up. They were both asymptomatic and followed up clinically and pharmacologically. These rates are lower than other published series in laparoscopic surgery in which recurrence has been nearly 23–43%.35,36 Recently, Fei et al. hypothesized that ultrastructural illness of diaphragmatic pillars might be implicated in this high recurrence.37 The authors proved that 94% of muscular samples coming from the crura were altered on microscopic view. Those findings suggest that the outcome of antireflux surgery could depend not only on the adopted surgical technique but also on the underlying status of the diaphragmatic crura.

We believe the robotic approach helps to achieve excellent long-term results in treating those large hiatal hernias. Our two and half years median follow-up does not help us to conclude the very long-term success of robotic surgery in this very challenging disease. We need higher number of patients and longer follow-up with prospective randomized studies to achieve those data. In our experience, we apply all the technical elements previously described in the laparoscopic era in performing the fundoplication.9,12,13 The dexterity of robotic surgery helps the surgeon add precision in every task related to this very difficult functional gastrointestinal disorder, compared with the laparoscopic approach.

CONCLUSION

We described in detail the robotic operative technique for total and partial fundoplication in treating large paraesophageal hiatal hernias, many of those with almost the entire stomach in the chest. We almost always add a biological absorbable mesh in those patients. The robotic REDO fundoplications are very challenging with high conversion rate, probably because of the use of biological absorbable mesh. We believe the long-term successful outcome is linked to all the technical elements related to the total and partial fundoplication techniques. The high dexterity of robotic surgery helps us to achieve the durable clinical outcome in this very difficult and common subgroup of patients in our clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge Mrs Lindsey Marie Vasquez's contribution in helping to review the manuscript in its grammar rules and language, making it more elegant for the journal.

Contributor Information

Massimo Arcerito, Riverside Medical Clinic Inc., University of California Riverside School of Medicine, Riverside, California.; Division of General and Vascular Surgery, Riverside Community Hospital, Riverside, California. Riverside Community Hospital, Riverside, California and Division of General and Vascular Surgery, Rancho Spring Medical Center, Murrieta Temescal Valley California.

Martin G. Perez, Riverside Medical Clinic Inc., University of California Riverside School of Medicine, Riverside, California.; Division of General and Vascular Surgery, Riverside Community Hospital, Riverside, California.

Harpreet Kaur, Division of General and Vascular Surgery, Riverside Community Hospital, Riverside, California..

Kenneth M. Annoreno, Division of General and Vascular Surgery, Riverside Community Hospital, Riverside, California..

John T. Moon, Shawnee Mission Medical Center, Shawnee Mission, Kansas..

References:

- 1. Soper NJ, Stockmann PT, Dunnegan DL, Ashley SW. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The new ‘gold standard’? Arch Surg. 1992;127:917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patti MG, Robinson T, Galvani C, Gorodner MV, Fisichella PM, Way LW. Total fundoplication is superior to partial fundoplication even when esophageal peristalsis is weak. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:863– 869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campos GM, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, et al. Multivariate analysis of factors predicting outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patti MG, Diener U, Tamburini A, Molena D, Way LW. Role of esophageal function tests in diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Broeders JAJL, Mauritz FA, Ahmed Ali U, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic Nissen (posterior total) versus Toupet (posterior partial) fundoplication for gastrooesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1318–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Asti E, Lovece A, Bonavina L, et al. Laparoscopic management of large hiatus hernia: five-year cohort study and comparison of mesh augmented versus standard crura repair. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5404–5409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oleynikov D, Eubanks TR, Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA. Total fundoplication is the operation of choice for patients with gastroesophageal reflux and defective peristalsis. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:909–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Musunuru S, Gould JC. Perioperative outcomes of surgical procedures for symptomatic fundoplication failure: a retrospective case-control study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:838–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patti MG, Arcerito M, Feo CV, et al. An analysis of operations for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Identifying the important technical elements. Arch Surg. 1998;133:600–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patti MG, De Bellis M, De Pinto M, et al. Partial fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:445–448, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patti MG, Feo CV, De Pinto M, Arcerito M, Tong J, Gantert W, Tyrrell D, Way LW. Results of laparoscopic antireflux surgery for dysphagia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Surg. 1998;176:564–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gantert WA, Patti MG, Arcerito M, et al. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernias. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:428–432, Apr; discussion 432–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arcerito M, Changchien E, Falcon M, Parga MA, Bernal O, Moon JT. Robotic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease and hiatal hernia: initial experience and outcome. Am Surg. 2018;84:1945–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gehrig T, Mehrabi A, Fischer L, et al. Robotic-assisted paraesophageal hernia repair: a case–control study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:691–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Draaisma WA, Gooszen HG, Consten EC, Broeders IA. Mid-term results of robot assisted laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia: a symptomatic and radiological prospective cohort study. Surg Technol Int. 2008;17:165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Galvani CA, Loebl H, Osuchukwu O, Samame J, Apel ME, Ghaderi I. Robotic assisted paraesophageal hernia repair: initial experience at a single institution. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2016;26:290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muller-Stich BP, Reiter MA, Wente MN, et al. Robot-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic fundoplication: short-term outcome of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1800–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Draaisma WA, Ruurda JP, Scheffer RC, et al. Randomized clinical trial of standard laparoscopic versus robot-assisted laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1351–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morino M, Pellegrino L, Giaccone C, Garrone C, Rebecchi F. Randomized clinical trial of robot-assisted versus laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg. 2006;93:553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakadi IE, Melot C, Closset J, et al. Evaluation of da Vinci Nissen fundoplication clinical results and cost minimization. World J Surg. 2006;30:1050–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hartmann J, Menenakos C, Ordemann J, Nocon M, Raue W, Braumann C. Long-term results of quality of life after standard laparoscopic vs robot-assisted laparoscopic fundoplications for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a comparative clinical trial. Int J Med Robot. 2009;5:32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heemskerk J, van Gemert WG, Greve JW, Bouvy ND. Robot-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: a comparative retrospective study on costs and time consumption. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ayav A, Bresler L, Brunaud L, Boissel P. Early results of one-year robotic surgery using the Da Vinci system to perform advanced laparoscopic procedures. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:720–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giulianotti PC, Coratti A, Angelini M, et al. Robotics in general surgery: personal experience in a large community hospital. Arch Surg. 2003;138:777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Melvin WS, Needleman BJ, Krause KR, Schneider C, Ellison EC. Computer-enhanced vs. standard laparoscopic antireflux surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stadlhuber RJ, Sherif AE, Mittal SK, et al. Mesh complications after prosthetic reinforcement of hiatal closure: a 28-case series. Surg Endosc. 2009. ;23:1219–12326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alicuben ET, Worrell SG, DeMeester SR. Impact of crural relaxing incisions, collis gastroplasty, and NoneCross-linked human dermal mesh crural reinforcement on early hiatal hernia recurrence rates. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:988– 992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abdelmoaty WF, Dunst CM1, Filicori F, et al. Combination of surgical technique and bioresorbable mesh reinforcement of the crural repair leads to low early hernia recurrence rates with laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter JG, et al. Biologic prosthesis to prevent recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: long-term follow up from a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gangopadhyay N, Perrone JM, Soper NJ, et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair in elderly and high risk patients. Surgery 2006;140:491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arcerito M, Moon JT. Robotic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease and hiatal hernia in elderly. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:S-1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bhayani NH, Kurian AA, Sharata AM, Reavis KM, Dunst CM, Swanstrom LL. Wait only to resuscitate: early surgery for acutely presenting paraesophageal hernias yields better outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parker DM, Rambhajan A, Johanson K, Ibele A, Gabrielsen JD, Petrick AT. Urgent laparoscopic repair of acutely symptomatic PEH is safe and effective. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4081–4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arcerito M, Kaur H, Mood JT. Robotic fundoplications for giant paraesophageal hernia: role of biosynthetic tissue reinforcement after cruroplasty. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:S-1485–S-1486. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Altorki NK, Yankelevitz D, Skinner DB. Massive hiatal hernias: the anatomic basis of repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:828–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hogan S, Pohi D, Bogetti D, Eubanks T, Pellegrini C. Failed antireflux surgery. Arch Surg. 1999;134:809–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fei L, Del Genio SM, Rossetti GL, et al. Hiatal hernia recurrence: surgical complication or disease? Electron Microscope Findings of the Diaphragmatic Pillars J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]