Neuroimaging suggests that human consciousness relies on frequent access to default mode and dorsal attention brain networks.

Abstract

The ongoing stream of human consciousness relies on two distinct cortical systems, the default mode network and the dorsal attention network, which alternate their activity in an anticorrelated manner. We examined how the two systems are regulated in the conscious brain and how they are disrupted when consciousness is diminished. We provide evidence for a “temporal circuit” characterized by a set of trajectories along which dynamic brain activity occurs. We demonstrate that the transitions between default mode and dorsal attention networks are embedded in this temporal circuit, in which a balanced reciprocal accessibility of brain states is characteristic of consciousness. Conversely, isolation of the default mode and dorsal attention networks from the temporal circuit is associated with unresponsiveness of diverse etiologies. These findings advance the foundational understanding of the functional role of anticorrelated systems in consciousness.

INTRODUCTION

Evidence from noninvasive functional neuroimaging studies has pointed to two distinct cortical systems that support consciousness. The default mode network (DMN) is an internally directed system that correlates with consciousness of self, and the dorsal attention network (DAT) is an externally directed system that correlates with consciousness of the environment (1–7). The DMN engages in a variety of internally directed processes such as autobiographical memory, imagination, and self-referencing (6–8). The DAT, on the other hand, mediates externally directed cognitive processes such as goal-driven attention, inhibition, and top-down guided voluntary control (2, 6, 9). Moreover, the DMN and DAT appear to be in a reciprocal relationship with each other such that they are not simultaneously active, i.e., they are “anticorrelated.” This anticorrelation is presumed to be vital for maintaining an ongoing interaction between self and environment that contributes to consciousness (5). Conversely, diminished anticorrelation between DMN and DAT activity has been reported in humans when consciousness was suppressed by general anesthesia (10, 11) and in neuropathological patients with disorders of consciousness (4, 12), supporting the hypothesis that a balance of the internally and externally directed systems is important for waking consciousness.

Despite some evidence for this temporal relationship, the anticorrelation of DMN and DAT over time has not been conclusively demonstrated. First, the anticorrelation of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) signals is generally inferred from temporally averaged functional connectivity, which does not allow a direct assessment of the temporal dynamics of networks. Second, the criticism has been raised that the anticorrelation of fMRI signals may be a by-product of global signal regression (GSR)—a necessary preprocessing step that most such studies have used (13–15). Therefore, the controversy about GSR characteristic of conventional static connectivity analysis prevents the unequivocal conclusion that the disruption of anticorrelation between DMN and DAT is a cause of disrupted consciousness. Furthermore, even assuming anticorrelation, the dynamic relationship of DMN and DAT to other networks of critical relevance to consciousness has not been elucidated.

To fill this gap of knowledge, an analysis of dynamic brain activity is necessary. Although the brain appears to engage in an ongoing exploration of its repertoire of distinct states (16–20), i.e., dynamic shaping and reshaping of functional brain configurations, it remains largely unknown if there is a structured exploration of its repertoire that is specific to the conscious versus unconscious brain. Accordingly, we hypothesized that the alternation of DMN and DAT over time is embedded in the ongoing exploration of all functional brain networks and that a disruption of this exploration may account for the diminished DMN-DAT anticorrelation when consciousness is suppressed. We also hypothesized that, in the conscious brain, the dynamic switching of networks including the DMN and DAT occurs along a set of structured transition trajectories, what might be conceived of as a “temporal circuit,” and that this temporal circuit is disrupted during diminished consciousness.

We tested our hypotheses by analyzing resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) signals from a cohort of 98 participants and patients in conditions that included conscious resting state and various unresponsive states induced by pharmacological (propofol and ketamine anesthesia, with distinct molecular targets) and neuropathological [unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (UWS)] etiologies. Although these conditions involve different molecular mechanisms, neural circuits, and brain functions, they share a common behavioral end point, i.e., a general unresponsiveness to external voice commands. Here, we conservatively use the term “unresponsiveness” instead of “unconsciousness” to allow for the possibility that covert or disconnected consciousness could occur in the absence of behavioral response. Combining data from different conditions allowed us to examine both the common and specific (anesthetic agent– and neuropathology-dependent) alterations of macroscale brain dynamics. We adopted an unsupervised machine learning approach to capturing transient, momentary coactivation patterns (CAPs) (21–24). The temporal dynamics of CAP transition trajectories were then analyzed as a Markov process, and the transition probability, persistence, and accessibility of CAPs were quantified. Last, we explored the stimulus modulations of CAPs during different conditions in a subset (n = 37) of the main cohort and evaluated the specificity of our results in an independent cohort of 248 participants consisting of healthy control participants and patients with psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and attention deficit/hyperactive disorder), who might have altered brain networks but who were nonetheless conscious.

RESULTS

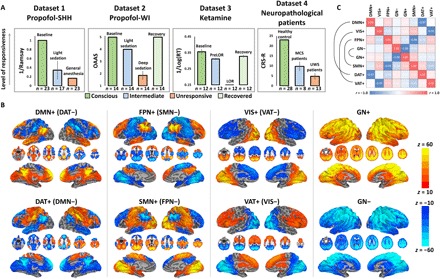

We recorded fMRI data at two independent research sites in Shanghai (SHH) and Wisconsin (WI), which generated four datasets (i.e., propofol-SHH, propofol-WI, ketamine, and neuropathological patients) containing both control and test results (Fig. 1A). CAPs of brain activity, i.e., sets of voxels simultaneously activated, were extracted from the entire dataset by k-means clustering algorithm (see more details in Materials and Methods). We determined an optimized number of CAPs (k = 8; from a search between 2 and 30) based on the non-GSR data for our main analysis scheme, and other selections of k (both with and without GSR) served as control analysis. This was achieved by evaluating the clustering performance, trading off the interdataset similarity (fig. S1) and visually inspecting the spatial patterns corresponding to major known functional networks (fig. S2). The eight CAPs were classified as DMN+, DAT+, frontoparietal network (FPN+), sensory and motor network (SMN+), visual network (VIS+), ventral attention network (VAT+), and global network of activation and deactivation (GN+ and GN−) (Fig. 1B). The eight CAPs could be divided into four pairs of “mirror” motifs, with a strong negative spatial similarity (Pearson correlation coefficient: r = −0.97 to −1.00; Fig. 1C). For instance, the DMN+ was accompanied by codeactivation of DAT (DAT−) and vice versa for DAT+ (DMN−). The “antiphasic” relationship between those mirror motifs is to be expected. Assuming that fMRI signals exhibit block correlation structure and that voxels fluctuate in their amplitude over time, then voxels will be “active” or “inactive” at different times with respect to the correlation structure and moving in blocks. In addition, the DMN+ and DAT+ were more spatially segregated (consisting of 18 and 14 clusters), distributed across widespread cortical and subcortical regions, compared to other CAPs (fig. S3). As expected, the CAPs could capture the instantaneous phase synchronizations at single-volume temporal resolution of fMRI (fig. S3).

Fig. 1. Level of behavioral responsiveness across datasets and CAPs.

(A) Dataset 1 (propofol-SHH) adopted Ramsay scale. Dataset 2 (propofol-WI) adopted observer’s assessment of alertness/sedation (OAAS). Dataset 3 (ketamine) adopted a button press task for every 30 s. Reaction time (RT) in milliseconds with respect to each instruction was recoded. By comparing the timing of verbal instruction and actual responsiveness during and after ketamine infusion, the periods during which a participant retained responsiveness (PreLOR), loss of responsiveness (LOR), and recovery of responsiveness were determined. Dataset 4 (neuropathological patients) adopted Coma Recovery Scale–Revised (CRS-R). Level of responsiveness is shown by the total score of six subscales (auditory, visual, motor, verbal, communication, and arousal). MCS, minimally conscious state. Error bars indicate ±SD. (B) Spatial maps of eight CAPs. The CAPs consist of DMN+, DAT+, FPN+, SMN+, VIS+, VAT+, GN+, and GN−. (C) The eight CAPs are composed of four pairs of mirror motifs with a strong negative spatial similarity, including DMN+ versus DAT+, VIS+ versus VAT+, FPN+ versus SMN+, and GN− versus GN+.

Suppression of DMN+ and DAT+ in various forms of behavioral unresponsiveness

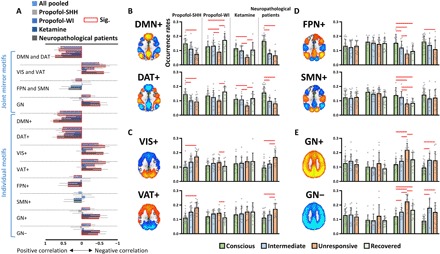

We first tested whether there are common associations between the occurrence rates of CAPs (i.e., dividing the number of fMRI volumes belonging to a given CAP by the total number of volumes per scan) and level of responsiveness across various conditions. We found significant positive correlations between the occurrence rates of DMN and DAT (joint DMN+ and DAT+) and level of responsiveness for all datasets together (all pooled, rho = 0.58, P < 0.0001), and individual datasets [propofol-SHH, rho = 0.64, P < 0.0001; propofol-WI, rho = 0.43, P = 0.0017; ketamine, rho = 0.55, P = 0.0002; neuropathological patients, rho = 0.73, P < 0.0001; false discovery rate (FDR)–corrected at α < 0.05] (Fig. 2A). The correlations for DMN+ and DAT+ alone yielded similar results. In contrast, for instance, the occurrence rates of VIS+ and VAT+ (for propofol-SHH, propofol-WI, and neuropathological patients) and GN+ and GN− (for ketamine and neuropathological patients) showed negative correlations with the level of responsiveness (see fig. S4 for scatterplots and statistics).

Fig. 2. Occurrence rates of CAPs.

(A) Spearman rank correlations between the occurrence rates of joint mirror motifs or individual CAPs and the level of responsiveness. (B to E) The CAP occurrence rates in different conditions (conscious, intermediate, unresponsive, and recovered) and in different datasets. Intermediate conditions refer to propofol light sedation, PreLOR of ketamine induction, and patients with MCS; unresponsive conditions refer to propofol general anesthesia and deep sedation, LOR due to ketamine, and patients with UWS. Red squares in (A) and lines in (B) to (E) indicate significance at FDR-corrected α < 0.05. See fig. S4 and table S1 for full statistics. Error bars in (A) indicate 95% confidence interval, and error bars in (B) to (E) indicate ±SD.

We next examined the differences of CAP occurrence rates between conditions. During unresponsive conditions, the occurrence rates of DMN+ and DAT+ were significantly reduced (a summary of statistics in table S1). As anticipated by the above correlation analysis, this phenomenon was reproducible in two independent datasets of propofol-induced unresponsiveness (propofol-SHH and propofol-WI) and generalizable from propofol-induced unresponsiveness to ketamine-induced unresponsiveness and to patients with minimally conscious state (MCS) and UWS (Fig. 2B). In addition, the results were robust with respect to the choice of k in the k-means clustering method and to the option of GSR or not during data preprocessing (fig. S5).

We also found specific changes of CAP occurrence rates during various unresponsive conditions. Comparing to the conscious condition, an increased prevalence of VIS+ and VAT+ was seen during propofol-induced unresponsiveness (Fig. 2C). An increased prevalence of GN+ and GN−, as well as a decreased prevalence of FPN+ and SMN+, respectively, was observed during ketamine-induced unresponsiveness (Fig. 2, D and E). The patients with UWS shared those effects with propofol and ketamine anesthesia. Last, we measured the state entropy characterizing the uniformity of the occurrence rates of different CAPs. We found that the state entropy was significantly reduced in all unresponsive conditions (P = 0.048 for conscious condition versus propofol-induced unresponsiveness; P = 0.005 for conscious condition versus ketamine-induced unresponsiveness; P = 0.022 for conscious condition versus patients with UWS). This suggests that the distribution of CAP occurrence rates tends to be less uniform (or imbalanced), and therefore more stereotypic, during unresponsive conditions.

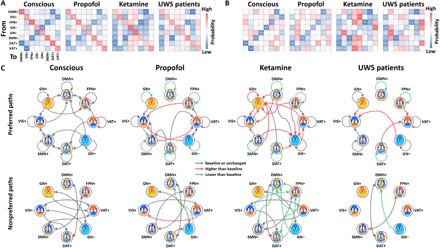

Persistence and transitions between CAPs distinguish conscious from behaviorally unresponsive conditions

To advance the field beyond the typical approach of describing static patterns, we sought to delineate the temporal dynamics of these CAPs and compare fully unresponsive conditions to baseline consciousness (Fig. 3, A and B, and see movie S1 for an illustration of CAP temporal dynamics). First, we observed distinct characteristics across different conditions in terms of preferred transitions (i.e., the probability of transitioning between two distinct CAPs is higher than a null model; see more details in Materials and Methods) and nonpreferred transitions (i.e., lower than null). During the conscious condition, the CAPs seemed to follow structured transition trajectories with relatively balanced preferred and nonpreferred paths. Second, in contrast, there were fewer trajectories reaching DMN+ and DAT+, and the trajectories were monopolized by a few specific “hosts” such as VIS+ and VAT+ during propofol-induced unresponsiveness and patients with UWS and VIS+, VAT+, GN+, and GN− during ketamine-induced unresponsiveness (Fig. 3C). Last, the CAP persistence probabilities, i.e., the probability of remaining in a given CAP, for all conditions occurred significantly above the level of chance (higher than a null model). However, compared to the conscious condition, the persistence probabilities of the CAPs were overall weaker during the unresponsive conditions (Fig. 3C). Ketamine-induced unresponsiveness was associated with an increased persistence of globally activated and deactivated brain states (GN+ and GN−).

Fig. 3. Transition probabilities among CAPs.

(A) Full transition probability matrix for conscious condition (conscious), propofol-induced unresponsiveness (propofol), ketamine-induced unresponsiveness (ketamine), and patients with UWS. The on-diagonal entries are referred to as the persistence probabilities. (B) Diagonal-free transition probability matrix, where the off-diagonal entries are referred to as transition probabilities by controlling for autocorrelation due to the CAP’s persistence. (C) Schematic illustration of the significant preferred paths (>null) and nonpreferred paths (<null) for conscious versus null, propofol versus null, ketamine versus null, and patients with UWS versus null (all gray arrows). Red (higher than conscious condition) and green (lower than conscious condition) arrows indicate significant differences of persistence probabilities and transition probabilities comparing to baseline consciousness. The null model for each condition and the differences between conditions were generated by 1000 permutations across the entire dataset (see more details in Materials and Methods). Significance level was determined at P < 0.001 by considering multiple comparison corrections (99.9th and 0.1th percentile of the null distributions; two-sided).

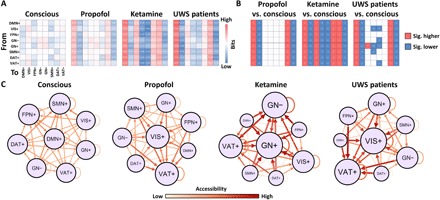

These observations were supported by examining the entropy of Markov trajectories (25, 26). This approach measured the descriptive complexity of trajectories (in bits) between each pair of CAPs (Fig. 4A). A lower descriptive complexity from a starting point (initial CAP) to its destination (final CAP) indicates a higher accessibility for the destination. For example, if the transition probability from CAP i to CAP j equals 1, then the entropy of trajectory from CAP i to CAP j is 0 bits, reflecting the conditional determinism (i.e., high accessibility) of that path. In contrast, if the transition probability from CAP i to CAP j equals to 0, then CAP i must first transition to other CAPs to end at CAP j. In this scenario, the entropy of trajectory from CAP i to CAP j is higher (needs more bits), thus reflecting a higher uncertainty or lower accessibility of that path. The key finding across these various conditions is that unresponsiveness was associated with an isolation (i.e., less accessibility) of DMN+ and DAT+ from the trajectory space, which is monopolized by a few giant attractors. More specifically, compared to the conscious condition, propofol-induced unresponsiveness and patients with UWS were characterized by increased accessibility of VIS+ and VAT+ and decreased accessibility of DMN+ and DAT+. Ketamine-induced unresponsiveness was characterized by increased accessibility of GN+, GN−, VIS+, and VAT+ and decreased accessibility of DMN+, DAT+, FPN+, and SMN+ (Fig. 4, B and C). The main finding regarding the decreased accessibility of DMN+ and DAT+ during unresponsive states was robust with respect to the choice of k and to the option of GSR or not during data preprocessing (fig. S6).

Fig. 4. Descriptive complexity of trajectories among CAPs and their in-degree accessibility.

(A) Descriptive complexity of trajectories (in bits) between each pair of CAPs in the conscious condition (conscious), propofol-induced unresponsiveness (propofol), ketamine-induced unresponsiveness (ketamine), and in patients with UWS. (B) Significant differences of the descriptive complexity of trajectories for propofol versus conscious, ketamine versus conscious, and patients with UWS versus conscious. The null models were generated by 1000 permutations across the entire dataset. Significance level was determined at P < 0.001. (C) Schematic illustration for (A). The accessibility of each CAP is defined as the inverse of descriptive complexity. The node size is proportional to in-degree accessibility. The Gephi Force Atlas layout algorithm (https://gephi.org) was used.

Furthermore, the transition probability and entropy of Markov trajectory matrices estimated from individual participants showed predictive value in distinguishing conscious versus unresponsive states. We did so by constructing a feature space based on these matrices and subsequently training a classifier of support vector machine (SVM; using sklearn.svm with default settings) by the leave-one-participant-out cross-validation procedure. We found that the SVM classifier achieved reliable performance. The mean classification accuracies for propofol versus conscious, ketamine versus conscious, and patients with UWS versus conscious were, respectively, 0.81 (P < 0.001, permutation test), 0.83 (P < 0.001), and 0.93 (P < 0.001) based on the transition probability matrices and 0.77 (P < 0.001), 0.75 (P = 0.028), and 0.88 (P < 0.001) based on the entropy of Markov trajectory matrices (fig. S7). We considered the above machine learning analyses as exploratory in supporting our major conclusions. Future investigations may be needed such as comparing different machine learning models, parameter optimization, or multiclass classification, which are beyond the scope of the current study.

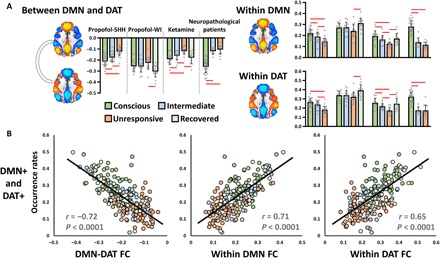

Antiphasic coactivation accounts for anticorrelation

The reduced occurrence rates of antiphasic coactivation of DMN+ and DAT+ are consistent with the previously reported decreased DMN-DAT anticorrelation in various unresponsive conditions (4, 10–12). First, in line with those studies, we observed significantly weakened DMN-DAT anticorrelation (GSR procedure was applied), as well as weakened within-network functional connectivity for both DMN and DAT, during propofol-induced unresponsiveness, ketamine-induced unresponsiveness, and in both MCS and UWS (Fig. 5A and see fig. S8 for results of other CAPs). We observed a strong negative correlation between the joint occurrence rates of DMN+ and DAT+ and the strength of DMN-DAT functional connectivity (r = −0.72, P < 0.0001) across all participants, suggesting that the lower the CAP prevalence in DMN+ and DAT+, the weaker the anticorrelation of DMN-DAT (Fig. 5B). As expected, positive correlations were seen between the joint occurrence rates of DMN+ and DAT+ and the within-network functional connectivity for both DMN (r = 0.71, P < 0.0001) and DAT (r = 0.65, P < 0.0001).

Fig. 5. Antiphasic coactivation accounts for anticorrelation.

(A) Conventional static functional connectivity between DMN and DAT and within-network connectivity of DMN and DAT in different conditions (conscious, intermediate, unresponsive, and recovered) and in different datasets. Red lines indicate significance at FDR-corrected α < 0.05. Error bars indicate ±SD. (B) Pearson correlations between the joint occurrence rates of DMN+ and DAT+ and the strength of DMN-DAT functional connectivity (FC) (left), as well as within-network functional connectivity of DMN (middle) and DAT (right) across all participants.

Note that the anticorrelation relationship between DMN and DAT, as measured by conventional static functional connectivity, was only seen when GSR was applied (fig. S8). Given that neither the identification of antiphasic CAPs of DMN+ and DAT+ (Fig. S2) nor the strong association between the occurrence rates of the two CAPs and their anticorrelations relies on the GSR procedure (fig. S9), it is plausible to assume that the anticorrelation structure underlying fMRI signals is not an artifact due to GSR; instead, it is inherent in the data and likely derives from the transient antiphasic CAPs. Therefore, our results may provide a more dynamic (i.e., reflecting transient neural events) and unbiased (i.e., avoiding the controversial methodology of GSR) account for the anticorrelation phenomenon commonly seen in fMRI signals and their associations with levels of consciousness.

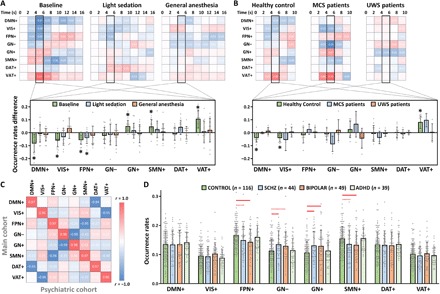

Stimulus modulations of CAPs and control analysis in psychiatric patients

Next, we sought to provide additional support for the functional and cognitive relevance of DMN+ and DAT+. Prior work suggests that the DMN is associated with internally focused awareness and can be suppressed when attention is shifted to external stimuli. The suppression of DMN’s activation may be triggered by the activation of other functional networks such as DAT and VAT during top-down allocation of attention and/or detection of unexpected stimuli (9). We thus hypothesized that, upon receiving external stimuli, the CAP occurrence rates of DMN+ would be attenuated, while the occurrence rates of other CAPs involved in stimulus processing would be elevated during conscious wakefulness. We also hypothesized that this modulation would be disrupted during reduced levels of responsiveness, which are presumably accompanied by reduced internal and/or external awareness. Accordingly, we investigated the effect of stimulus modulations on the CAP occurrence rates during different levels of responsiveness. We examined a subset of participants in dataset 1 (propofol-SHH) and dataset 4 (neuropathological patients) that received auditory stimuli (e.g., verbal names in propofol-SHH and verbal sentences in neuropathological patients) without any requirement of motor response (27, 28). We assigned each time point of the task dataset to a particular CAP based on its maximal similarity to the CAP centroids derived from the main cohort resting-state data. The purpose of doing this was to make the results comparable and generalizable across datasets. As predicted, auditory stimuli were associated with an attenuation of CAP occurrence rates of DMN+ (as well as VIS+), with an elevated CAP occurrence rate of VAT+ in both datasets only during conscious conditions (Fig. 6, A and B). The results support that the DMN+ identified in our main cohort could be suppressed when the brain attends to external stimuli, whereas this stimulus modulation was corrupted during unresponsiveness (propofol-induced and patients with UWS).

Fig. 6. Stimulus modulations of CAPs and control analysis in psychiatric patients.

(A) Stimulus-induced CAP occurrence rate changes (against stimulus onset, t = 0) in baseline conscious condition, light sedation, and general anesthesia (n = 15). Student’s t tests (against zero) for the CAP occurrence rate changes were performed during the peak period of stimulus-evoked fMRI signal activity (4 to 6 s). Asterisks indicate significance at α < 0.05 after FDR correction. (B) Stimulus-induced CAP occurrence rate changes in healthy controls (n = 12), patients with MCS (n = 4), and patients with UWS (n = 6). (C) Spatial similarity of the eight CAPs between the main cohort and psychiatric cohort data. (D) Comparisons of the CAP occurrence rates for healthy control participants (CONTROL) versus schizophrenic (SCHZ), bipolar disorder (BIPOLAR), and attention deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) patients by Student’s t tests. Red solid lines indicate significant group differences at α < 0.05 after FDR correction, and red dash lines indicate uncorrected significance at P < 0.05. Error bars indicate ±SD.

Last, we extended our observations from pharmacological and neuropathological data to an open access dataset from a cohort of patients with psychiatric disease (29). We assessed whether the suppression of DMN+ and DAT+ is specific to the reduced level of responsiveness as opposed to disorders of cognitive function in general. Another motivation was to further understand the ketamine-specific alterations in the CAP occurrence rates, as altered states of consciousness induced by ketamine are often associated with psychoactive effects and unique brain dynamics (30–32). Using the same method applied in the task dataset (i.e., maximal similarity to the predefined CAP centroids from the main cohort), we identified eight comparable CAPs in the psychiatric cohort (Fig. 6C). There were two main observations. First, we did not find any significant difference between healthy control participants and patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or attention deficit/hyperactive disorder in the occurrence rates of DMN+ and DAT+. Second, we found that the occurrence rates of GN+ and GN− were both significantly increased in schizophrenic patients, while the occurrence rates of FPN+ and SMN+ were both significantly decreased in patients with bipolar disorder (Fig. 6D). Patients with attention deficit/hyperactive disorder did not show any significant difference compared to healthy control participants. Therefore, altered occurrence rates of DMN+ and DAT+ are specific to unresponsiveness (likely reflecting unconsciousness in these experimental groups) and do not simply occur as a result of any brain disorder. Furthermore, the results suggest that alterations of the occurrence rates of FPN+, SMN+, GN+, and GN− induced by ketamine are similar to those found in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to determine the spatiotemporal dynamics of prevalent functional brain networks in the conscious state and their potential modification during unresponsiveness. Our results revealed both common and distinct characteristics of brain activity in anesthetized participants and neuropathological patients as compared to conscious conditions. The temporal prevalence of two CAPs, DMN+ and DAT+, was suppressed in both propofol- and ketamine-induced unresponsiveness as well as in patients with UWS. The changes specific to various unresponsive conditions included an increased prevalence of antiphasic activation of VIS+ and VAT+ with propofol and an increased prevalence of global network activity with ketamine. Patients with UWS shared the latter two effects. We demonstrate that conscious brain activity is characterized by a set of structured dynamic transition trajectories in which the accessibility of distinct brain states is relatively balanced. In contrast, during unresponsiveness, the trajectories are substantially altered such that the DMN and DAT become isolated, and the trajectories become monopolized by the visual, ventral attention, and global networks.

Common spatiotemporal characteristics during behavioral unresponsiveness

A key finding of our study is the suppression of antiphasic activation of DMN+ and DAT+ that occurred in various conditions of behavioral unresponsiveness. Given that this result was obtained with different anesthetic agents with distinct molecular targets and in nonanesthetized neuropathological patients, we are inclined to tentatively conclude that DMN+ and DAT+ are two fundamental signatures of consciousness. Our results provide a dynamic account of the suppression of DMN+ and DAT+ prevalence during unresponsiveness. First, the sequential maintenance of the CAPs (measured by their persistence probabilities) was overall weaker in the unresponsive conditions compared to the conscious condition. This suggests that, during unresponsiveness, the brain states of DMN+ and DAT+ were less stable. Second, during unresponsiveness, the DMN+ and DAT+ were dissociated from the reciprocal relationship of CAPs that were instead monopolized by VIS+, VAT+, GN+, and GN− (e.g., Fig. 3C). That is, it became difficult, along with the increased complexity of trajectories (less accessible), for the other CAPs to transition to DMN+ or DAT+ (e.g., Fig. 4C). This finding provides new understanding, in terms of spatiotemporal brain dynamics, of how the previously known anticorrelation of DMN and DAT is diminished in unconsciousness (4, 10–12).

According to prior evidence from functional neuroimaging of disorders of consciousness (4, 12) and anesthesia (10, 11), an anticorrelated activity of the DMN and DAT is associated with internal versus external awareness (sometimes also referred to as disconnected and connected consciousness, respectively). In addition, a behavioral and neuroimaging experiment in healthy volunteers reported a periodic shift from internal to external awareness associated with the periodic neural activity in the DMN and DAT (8). Consequently, in our results, the suppression of both DMN+ and DAT+ may indicate a lack of both forms of awareness (internal and external) during unresponsiveness. The observation that the degree of suppression of the DMN+ and DAT+ was similar across the pharmacological and neuropathological unresponsive conditions suggests that internal and external awareness may be tightly interacting and the give-and-take relationship of the two systems may be particularly important for normal levels of consciousness.

This interpretation is further supported by the results of stimulus modulation at different levels of responsiveness. Upon receiving auditory stimuli, the CAP occurrence rate of DMN+ was attenuated, while the occurrence rate of VAT+ (involved in auditory stimulus processing) was elevated only during conscious conditions. This is consistent with our expectation that the DMN+, associated with internal awareness, is suppressed when attention is shifted to external stimuli. The occurrence rate of stimulus-related attenuation of the DMN+ was not found in the unresponsive conditions (propofol-induced and patients with UWS). Although the DAT+ occurrence rate was not increased by the auditory stimulus, this may be expected. The DAT mediates top-down guided voluntary allocation of attention, whereas the VAT is involved in detecting unattended or unexpected stimuli and triggering shifts of attention (9). As the stimulus applied in our study did not require voluntary execution, it did not, as would be predicted, activate the DAT+ system.

Distinct spatiotemporal characteristics during behavioral unresponsiveness

In addition to the common effects across unresponsive conditions, we observed some specific changes of CAP prevalence and transition dynamics. During propofol-induced unresponsiveness, VIS+ and VAT+ played a dominant role, where the prevalence of both CAPs was increased compared to the conscious condition. They served as attractors into which other CAPs transformed (e.g., Figs. 3C and 4C). As the VIS+ and VAT+ are at a relatively low or intermediate level of hierarchical cortical functional organization (33), we speculate that propofol may shift the hierarchical cortical functional organization to a lower order. However, the validity of this speculation will require more detailed investigations such as measuring the functional gradient of networks under propofol anesthesia.

During ketamine-induced unresponsiveness, GN+ and GN− increased their prevalence and persistence probabilities compared to the conscious condition and served as attractors. The changes were analogous to those of schizophrenic patients (e.g., Fig. 6D). Prior studies have reported global hyperconnectivity of fMRI signals in schizophrenic patients (34), as well as shared phenomenology between schizophrenic symptoms and ketamine’s dissociative/psychoactive effects (30, 32). All participants receiving ketamine reported having dreams, and 8 of 12 participants in our study could recall their hallucinations (e.g., flying on a cloud, weird smells, taking an elevator, and thick mist) after recovery from anesthesia. Therefore, we speculate that the dominance of GN+ and GN− in the dynamic brain states may be associated with psychoactive effects.

In patients with UWS, the alterations of brain state dynamics seemed to be situated in between propofol and ketamine anesthesia. If we assume that the arousal of patients with UWS was relatively preserved, unlike the suppression of arousal in propofol-induced unresponsive participants, then the GN+ and GN− in UWS may reflect, to some extent, arousal fluctuations (35, 36).

Spatial characteristics of CAPs

We identified six CAPs encompassing the DMN+, DAT+, FPN+, SMN+, VIS+, and VAT+ that resembled canonical resting-state networks in agreement with previous studies (24, 37, 38). We also identified two other CAPs with globally activated and deactivated patterns (GN+ and GN−), which have been related to arousal or vigilance fluctuations in the context of the global brain signal (35, 36). GN+ and GN− were present without applying GSR (e.g., fig. S2). Note that, compared to other CAPs, the DMN+ and DAT+ showed the highest within-network anatomical segregation as they consisted of 18 and 14 clusters, respectively, distributed across widespread cortical and subcortical regions (e.g., fig. S3). We speculate that spatial segregation is relevant for the higher-order abstract representations necessary for conscious processing. This is supported by evidence that the DMN and DAT are at a high position of a representational hierarchy, with a widespread backbone, relatively far from the sensory and motor systems in terms of both functional connectivity and anatomical distance (33). This hierarchical disposition is thought to allow the two systems to process transmodal information in a way that is unconstrained by immediate sensory input.

Methodologic strengths and limitations

Our approach has unique strengths. First, the k-means clustering method can capture transient, temporally localized coactivations, which reflect the underlying brain activity in a rather direct way when compared to conventional time-averaged analysis. The clustering procedure itself does not perform any transformation of the data, holds a minimal set of assumptions and constraints, and is free from the controversial aspects of GSR (21). The method thus allowed us to reframe the known neural phenomenon—i.e., diminished, temporally averaged DMN-DAT anticorrelation in unresponsiveness—into a dynamic picture of brain activity where the DMN and DAT are embedded in a chain of transient explorations among distinct brain states. Second, the temporal dynamics of brain states were analyzed as a Markov process. This method allowed us to quantify temporal dependencies of brain states and their trajectories, leading us to form the concept of a temporal circuit. Third, we combined an unsupervised machine learning approach (k-means clustering) with a supervised machine learning approach (i.e., maximal similarity to predefined cluster centroids), when comparing our results from the main cohort with another cohort. This method, with relatively low computational cost, may have the potential for “big data” analysis rendering the observations comparable and generalizable across multiple datasets or research sites. This idea may be analogous to the seed-based (supervised) functional connectivity analysis with a priori knowledge of seed regions.

A few limitations of our study are recognized. First, coactivation at the temporal resolution of 2 s is, at best, an indirect measure of large-scale brain connectivity. Second, the neural origin of transient CAPs remains unclear. Third, the richness of mental content and cognitive process seems far beyond the repertoire of CAPs we can detect. The functional association and the causal relationship between CAPs and cognitive functions remain unclear. Fourth, the relationship of CAP transitions to the fast transient topographical patterns of electroencephalography (EEG) (39) and magnetoencephalography (40), such as “microstates” on the order of 100 ms, remains to be determined. However, recent studies of EEG during anesthetic-induced unresponsiveness have used k-means clustering and Markov analysis, suggesting that addressing the neurophysiologic time scale with these techniques is tractable (41, 42). Fifth, the choice of k (the number of CAPs) for clustering analysis was somewhat challenging. Arguably, any reasonable choice would far underestimate the actual diversity of meaningful brain states. The choice of k, in general, is limited by the experimental approach and fMRI methodology. Sixth, we found that the reduced occurrence rates of DMN+ and DAT+ were accompanied by the decreased trajectory accessibility of the two CAPs during unresponsiveness. This coincidence may be expected. For instance, if other CAPs do not prefer to transition to DMN+ or DAT+, then the occurrence rates of the two CAPs (regardless of its own repetitions or persistence) will be likely lower than that of others. In this sense, the occurrence rates and transition probabilities may offer two views of the same temporal dynamics, whereas the information gained from the two quantities is partially overlapped. Furthermore, if we assume that the transition probabilities between CAPs are caused by certain neural mechanisms, then the occurrence rates are just statistical descriptions resulting from the transition probabilities. The precise neural mechanisms and the regulation of state transitions may be an important question for future investigations. Last, although our observations yield predictions that can guide future work, an important caveat is that the specific characteristics of CAPs in different states of consciousness were derived from rs-fMRI signals without subjective report of mental content. Therefore, the exact associations between those CAPs and conscious contents remain to be systematically studied.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that human consciousness relies on a specific temporal circuit of dynamic brain activity characterized by balanced reciprocal accessibility of functional brain states. The disruption of this temporal circuit, exhibiting limited access to the DMN and DAT, appears to be a common signature of unresponsiveness of diverse etiologies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The fMRI data were recorded at two independent research sites (Shanghai and Wisconsin), which generated four datasets containing both control and test results. Dataset 1 included 23 participants during baseline conscious condition, propofol light sedation, and propofol general anesthesia collected in Shanghai, hereafter referred to as propofol-SHH. Dataset 2 included 14 participants during baseline conscious condition, propofol light sedation, propofol deep sedation, and recovery, which was collected in Wisconsin, hereafter referred to as propofol-WI. Dataset 3 included 12 participants during baseline conscious condition, ketamine induction period before loss of responsiveness (PreLOR), loss of responsiveness (LOR) period, and recovery of responsiveness period, hereafter referred to as ketamine. Dataset 4 includes 28 healthy controls (conscious condition), 8 patients diagnosed in an MCS, and 13 patients diagnosed in an UWS/vegetative state. This dataset, with patients of disorders of consciousness, was referred to as neuropathological patients. To minimize misdiagnosis, these states were defined by validated, objective scales as opposed to clinical interpretation alone.

Dataset 1: Propofol-SHH

The dataset has been previously published using analyses different from those applied here (28, 43). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants (n = 26; right-handed; male/female, 12/14; age, 27 to 64 years), who were undergoing an elective transsphenoidal approach for pituitary microadenoma resection. The pituitary microadenomas were diagnosed by their size (<10 mm in diameter without growing out of the sella) based on radiological examinations and plasma endocrinal parameters. The participants were American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I or II, with no history of brain dysfunction, vital organ dysfunction, or administration of neuropsychiatric drugs. They had no contraindication to an MRI examination, such as vascular clips or metallic implants. Among them, 3 participants had to be excluded from the study and further data analysis because of excessive movements, resulting in 23 participants for the following analysis.

Participants fasted for at least 8 hours from solid foods and 2 hours from liquids before the study. Vital signs including blood pressure, electrocardiography, pulse oximetry (SpO2), and partial pressure of carbon dioxide were continuously monitored during the fMRI study. The participants received propofol light sedation (17 of 23) and general anesthesia (n = 23), during which intravenous anesthetic propofol was infused through an intravenous catheter placed into a vein of the right hand or forearm. Propofol was administered using a target-controlled infusion (TCI) pump to obtain constant effect-site concentration, as estimated by the pharmacokinetic model of propofol (Marsh model). Remifentanil (1.0 μg/kg) and succinylcholine (1.5 mg/kg) were administered to facilitate endotracheal intubation under general anesthesia. TCI concentrations were increased in 0.1 μg/ml steps beginning at 1.0 μg/ml until reaching the appropriate effect-site concentration. A 5-min equilibration period was allowed to ensure equilibration of propofol distribution between compartments.

The TCI propofol was maintained at a stable effect-site concentration for light sedation (1.3 μg/ml) and for general anesthesia (4.0 μg/ml). Behavioral responsiveness was assessed by the Ramsay scale. The participants were asked to strongly squeeze the hand of the investigator. The participant was considered fully conscious if the response to verbal command (“strongly squeeze my hand!”) was clear and strong (Ramsay 1 and 2), in mild sedation if the response to verbal command was clear but slow (Ramsay 3 and 4), and in deep sedation or general anesthesia if there was no response to verbal command (Ramsay 5 and 6). For each assessment, the Ramsay scale verbal commands were repeated twice. The participants continued to breathe spontaneously, with supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula, during conscious resting state and light sedation. During general anesthesia, the participants were ventilated with intermittent positive pressure ventilation, setting a tidal volume at 8 to 10 ml/kg, a respiratory rate of 10 to 12 beats/min, and maintaining partial pressure of end tidal CO2 at 35 to 45 mmHg. Two certified anesthesiologists were present throughout the study and assured that resuscitation equipment was always available. Participants wore earplugs and headphones during the fMRI scanning.

rs-fMRI data acquisition consisted of three 8-min scans in baseline conscious condition, light sedation, and general anesthesia. The participant’s head was fixed in the scan frame and padded with spongy cushions to minimize head movement. The participants were asked to relax and assume a comfortable supine position with their eyes closed during scanning (an eye patch was applied). They were instructed not to concentrate on anything in particular during the resting-state scan. A Siemens 3T scanner (Siemens MAGNETOM, Germany) with a standard eight-channel head coil was used to acquire gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) images of the whole brain [33 slices; repetition time/echo time (TR/TE), 2000/30 ms; slice thickness, 5 mm; field of view, 210 mm; flip angle, 90°; image matrix, 64 × 64]. High-resolution anatomical images were also acquired for rs-fMRI coregistration.

Dataset 2: Propofol-WI

The dataset has been previously published using analyses different from those applied here (44). The IRB of Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) approved the experimental protocol. Fifteen healthy participants (male/female, 9/6; age, 19 to 35 years) received propofol sedation. The OAAS (observer’s assessment of alertness/sedation) was applied to measure the levels of behavioral responsiveness. During baseline conscious and recovery conditions, participants responded readily to verbal commands (OAAS score, 5). During light sedation, participants showed lethargic response to verbal commands (OAAS score, 4). During deep sedation, participants showed no response to verbal commands (OAAS score, 2 and 1). The corresponding target plasma concentrations vary across participants (light sedation, 0.98 ± 0.18 μg/ml; deep sedation, 1.88 ± 0.24 μg/ml) because of the variability in individual sensitivity to anesthetics. At each level of sedation, the plasma concentration of propofol was maintained at equilibrium by continuously adjusting the infusion rate to maintain the balance between accumulation and elimination of the drug. The infusion rate was manually controlled and guided by the output of a computer simulation developed for target-controlled drug infusion (STANPUMP) based on the pharmacokinetic model of propofol. Standard ASA monitoring was conducted during the experiment, including electrocardiogram, noninvasive blood pressure cuff, pulse oximetry, and end-tidal carbon dioxide gas monitoring. Supplemental oxygen was administered prophylactically via nasal cannula. One participant had to be excluded from the study and further data analysis because of excessive movements, resulting in 14 participants for the following analysis.

rs-fMRI data acquisition consisted of four 15-min scans in baseline conscious condition, light and deep sedation, and recovery. A 3T Signa GE 750 scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) with a standard 32-channel transmit/receive head coil was used to acquire gradient-echo EPI images of the whole brain (41 slices; TR/TE, 2000/25 ms; slice thickness, 3.5 mm; field of view, 224 mm; flip angle, 77°; image matrix, 64 × 64). High-resolution anatomical images were also acquired for rs-fMRI coregistration.

Dataset 3: Ketamine

The study was approved by the IRB of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Twelve right-handed participants were recruited (male/female, 7/5; age, 32 to 66 years), who were undergoing an elective transsphenoidal approach for resection of a pituitary microadenoma. The patient inclusion, anesthesia procedure, fMRI setting-up and scanning parameters, and vital sign monitoring were the same as those of propofol-SHH.

Ketamine was infused through an intravenous catheter placed into a vein of the left forearm. Continues fMRI scanning was conducted throughout the whole experiment for about 1 hour, ranging from 44 to 62 min (means ± SD, 54.6 ± 5.9 min). A 10-min baseline conscious condition was first acquired (except for two participants in which baseline condition was for 6 and 11 min). Then, 0.05 mg/kg per min of ketamine was infused for 10 min (0.5 mg/kg in total), and 0.1 mg/kg per min was infused for another 10 min (1.0 mg/kg in total), except for two participants who only received 0.1 mg/kg per min infusion for 10 min. After that, the ketamine infusion was discontinued, and participants regained their responsiveness spontaneously.

Behavioral responsiveness (button press) was assessed throughout the entire fMRI scan. Specifically, participants were asked to press a button using their right index finger after hearing a verbal instruction “press the button.” The instruction was programmed to play every 30 s using E-Prime 2.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA) and was delivered via earphones designed for an MRI environment. The volume of the headphones was adjusted for participant comfort. By comparing the timing of verbal instruction and actual responsiveness during and after ketamine infusion, the periods during which a participant retained responsiveness (PreLOR), LOR, and recovery of responsiveness were determined. The duration (means ± SD in minutes) for each period across participants was 9.8 ± 1.0 for baseline conscious condition, 12.5 ± 4.5 for PreLOR, 18.2 ± 7.6 for LOR, and 14.1 ± 6.0 for recovery. In addition, reaction time with respect to each instruction was recoded for quantitative analysis of behavioral responsiveness.

Dataset 4: Neuropathological patients

The dataset has been previously published using analyses different from those applied here (27, 43). The study was approved by the IRB of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University. Informed consent was obtained from the patients’ legal representatives and from the healthy participants. The dataset included 21 patients (male/female, 18/3) with disorders of consciousness and 28 healthy control participants (male/female, 14/14). The patients were assessed using the Coma Recovery Scale–Revised (45) on the day of fMRI scanning. Of those assessed, 13 patients were diagnosed as having UWS, and 8 patients were diagnosed as being in MCS. None of the healthy controls had a history of neurological or psychiatric disorders nor were they taking any kind of medication.

rs-fMRI data were acquired on a Siemens 3T scanner (Siemens MAGNETOM, Germany). A standard eight-channel head coil was used to acquire gradient-echo EPI images of the whole brain (33 slices; TR/TE, 2000/35 ms; slice thickness, 4 mm; field of view, 256 mm; flip angle, 90°; image matrix, 64 × 64). Two hundred EPI volumes (6 min and 40 s) and high-resolution anatomical images were acquired.

Data preprocessing

Preprocessing steps were implemented in AFNI (Analysis of Functional NeuroImages; http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/). (i) The first two frames of each fMRI run were discarded; (ii) slice timing correction; (iii) rigid head motion correction/realignment within and across runs; frame-wise displacement (FD) of head motion was calculated using frame-wise Euclidean norm (square root of the sum squares) of the six-dimensional motion derivatives (46). A frame and its each previous frame were tagged as zeros (ones, otherwise) if the given frame’s derivative value has a Euclidean norm above 0.4 mm of FD (44); (iv) coregistration with high-resolution anatomical images; (v) spatial normalization into Talairach stereotactic space; (vi) using AFNI’s function 3dTproject, the time-censored data were high-pass filtered above 0.008 Hz. At the same time, various undesired components (e.g., physiological estimates and motion parameters) were removed via linear regression. The undesired components included linear and nonlinear drift, time series of head motion and its temporal derivative, binarized FD time series (output data included zero values at censored time points), and mean time series from the white matter and cerebrospinal fluid; (vii) spatial smoothing with 6-mm full width at half maximum isotropic Gaussian kernel; (viii) the time course per voxel of each run was normalized to zero mean and unit variance, accounting for differences in variance of non-neural origin (e.g., distance from head coil). GSR was not applied for our main analysis, as we were motivated to provide a dynamic and unbiased account for the anticorrelation phenomenon commonly seen in conventional static functional connectivity with GSR procedure. However, to evaluate the robustness of our results against different processing schemes, we also performed control analyses both with and without the GSR procedure.

CAP analysis

We adopted an unsupervised machine learning approach using k-means clustering algorithm. It is a procedure for classifying a set of objects (e.g., fMRI volumes) into different categories (e.g., patterns) such that within category differences are smaller than across category differences. Accordingly, we classified fMRI volumes into k clusters based on their spatial similarity and thus produced a set of CAPs or brain states (22, 24). Hence, the original fMRI (three-dimensional + time) data were translated into a one-dimensional time series of discrete CAP labels.

The above analysis was performed on the concatenated data of 69,010 fMRI volumes acquired from all 98 participants. There were 7.1% of the total volumes tagged as zeros based on the above motion censoring procedure, which were not included in the following analysis. Then, k-means clustering was performed to partition the all fMRI volumes of the matrix (64,118 volumes × 6088 voxels) into k clusters, which returned a 64,118 × 1 vector containing cluster indices (i.e., CAP labels) for each fMRI volume. The distance between two fMRI volumes was defined as one minus their Pearson’s correlation coefficient of the intensity values across voxels (22, 24). The computational load of the k-means clustering increases quickly with the number of fMRI volumes. As a trade-off between computational cost and spatial resolution, the preprocessed fMRI data were down-sampled to the spatial resolution of 6 mm by 6 mm by 6 mm while preserving the original temporal resolution (2 s) before k-means clustering.

After clustering, the fMRI volumes assigned to the same cluster were simply averaged, resulting in k maps that we defined as CAPs. These CAPs were then normalized by the SE (within cluster and across fMRI volumes) to generate z-statistic maps, which quantify the degree of significance to which the CAP map values (for each voxel) deviate from zero (22). The spatial characteristics of those CAPs were examined by counting the number of spatial clusters as a function of threshold (z values; ranging from 1 to 100). A single spatial cluster was defined as the nearest-neighbor clustering (faces touching) encompassing at least six voxels, where positive and negative voxels in each CAP were calculated separately. In addition, we calculated the instantaneous phase synchrony for each CAP. For each voxel’s time series, the instantaneous phase traces were calculated using Hilbert transform. The phase synchrony across voxels as a function of time was quantified by the Kuramoto order parameter. Then, the phase synchrony values were sorted into k bins according to the time series of CAP labels. The phase synchrony values within each bin were averaged yielding the mean phase synchrony for each CAP.

For each participant or each condition, the occurrence rate of each CAP was quantified by the ratio of the number of volumes that appeared versus the total number of volumes per scan. A challenge for clustering analysis is the choice of k, i.e., the number of CAPs to be extracted from the data. We evaluated the clustering performance using a few indices including Silhouette, Calinski-Harabasz, Davies-Bouldin, and Dunn for the data with and without GSR (fig. S1). Broadly speaking, higher values of the Silhouette, Calinski-Harabasz, and Dunn and a lower value of the Davies-Bouldin indicate a better separation of clusters and more tightness inside the clusters. In line with a previous study by Liu et al. (22), who used the dataset from the 1000 Functional Connectomes Project, we also observed that different clustering evaluation criteria yielded inconsistent recommendations. We next sought to adopt an alternative strategy by identifying a k with the best reliability of consistently identifying conscious conditions across datasets and the best distinction of conscious versus unresponsive conditions. Specifically, we determined an optimized k (from a search between 2 and 30) by trading off the interdataset similarity (measured by Euclidean distance) of the averaged CAP occurrence rate distributions in each dataset. We derived an index, (CC + UU)/(2 × CU), as the ratio of interdataset similarity among conscious conditions (CC) and among unresponsive conditions (UU) versus the interdataset similarity among conscious and unresponsive conditions (CU) across the four datasets. We found that k = 8 (non-GSR) yielded a high interdataset similarity among conscious conditions and among unresponsive conditions, with a low interdataset similarity among conscious and unresponsive conditions. In addition, to further evaluate the choice of k, we inspected the spatial patterns in terms of consistency and redundancy from k = 2 to k = 16 with a step of two (fig. S2).

Transition matrix

For each condition, we concatenated all participants’ CAP time series and computed the transition probability between each pair of CAPs. These transition probability matrices can be described by a Markov process, where the probability of CAP j (at time t + 1) is determined by the CAP i (at time t). That is, we defined transition probability between two CAPs to be the probability of transitioning from state CAP i to CAP j, given that the current state is CAP i. Those probabilities was encoded in a transition matrix with row sums equal to 1 and the ijth elements of the matrix equal to the number of transitions from CAP i to CAP j divided by the number of occurrences of CAP i. We referred to the diagonal entries in the full transition probability matrix as the persistence probabilities, i.e., the probability of remaining in a given CAP. We referred to the off-diagonal transition probability matrix as the transition probabilities, i.e., the probability of transitioning between two distinct CAPs. The off-diagonal transition probability matrix was calculated by removing repeating CAPs in the time series to control for autocorrelation due to the CAP’s persistence (24). Note that the censored time point of head motion and the joint point between participants were tagged with zeros, such that the transition from a CAP to zero or from zero to a CAP was discarded in the above calculation. This may minimize the head motion effect and avoid the contamination of noncontinued data derived from concatenation.

Entropy of Markov trajectories

On the basis of the above off-diagonal transition probability matrices, we quantified the entropy of Markov trajectories (25, 26). This approach measured the descriptive complexity of trajectories (in bits) between each pair of CAPs, e.g., routes starting from a particular CAP and ending to another. A lower descriptive complexity from a starting point (initial CAP) to its destination (final CAP) indicates a higher accessibility for the destination. More specifically, the entropy of Markovian trajectories is considered as a finite irreducible Markovian chain with transition matrix P and associated entropy rate H(X) = −∑i,j μi Pij log Pij, where μ is the stationary distribution given by the solution of μ = μP. A trajectory Tij of the Markov chain is a path with initial state i, final state j, and no intervening states equal to j. The entropy H(Tii) of the random trajectory originating and terminating in state i is given by H(Tii) = H(X)/μi. Therefore, the entropy of the random trajectory Tii is the product of the expected number of steps 1/μi to return to state i and the entropy rate H(X) per step for the stationary Markov chain. The entropies H(Tij) is given by H = K − K′ + HΔ, where H is the matrix of trajectory entropies Hij = H(Tij); K = (I − P + A)−1 (H* − HΔ); K′ is a matrix in which the ijth element Kij′ equals the diagonal element Kij of K; A is the matrix of stationary probabilities with entries Aij = μj; H* is the matrix of single-step entropies with entries Hij* = H(Pi) = −∑k Pik log Pik; and HΔ is a diagonal matrix with entries (HΔ)ii = H(X)/μi. For further details, see the seminar work by Ekroot and Cover (25), and the MATLAB code is available at https://github.com/stdimitr/Entropy_of_Markov_Trajectories.

Conventional static functional connectivity analysis

We defined functional networks based on the identified CAPs. As a CAP may include antiphasic coactivations (e.g., voxels with positive or negative values), presumably representing two anticorrelation networks, we thus only extracted the positive voxels within each CAP and binarized them to form a mask of a given network. Within-network connectivity was defined as the averaged Pearson correlation coefficients (Fisher’s z-transformed) between all pairs of voxels within the network, and between-network connectivity was calculated by averaging the Pearson correlation coefficient between all pairs of voxels from different networks (i.e., excluding within-network voxel pairs). Both measurements were calculated for data with and without GSR procedure.

Stimulus modulation

A subset of participants in propofol-SHH (n = 15) and neuropathological patients (n = 22; 12 healthy controls, 4 MCS, and 6 UWS) received auditory stimuli. For propofol-SHH, an event-related design was adopted with 60 names delivered in a pseudorandom order [see more details in (28)]. Each audio clip (0.5 s) was followed by intertrial intervals (ITIs) ranging unpredictably from 15.5 to 25.5 s (2-s step). The participants were required to pay attention and passively listen to the names without behavioral response or judgment. Three 18-min fMRI scans were acquired for each level of responsiveness (baseline conscious condition, light sedation, and general anesthesia). For neuropathological patients, an event-related design was applied with 160 sentences delivered in a pseudorandom order [see more details in (27)]. Each audio clip (2 s) was followed by ITIs ranging unpredictably from 8.0 to 12.0 s (2-s step). All participants were instructed to silently answer the questions. Four 18-min fMRI scans were acquired for each participant.

After applying the same fMRI data preprocessing pipeline, we assigned each time point of the task dataset to a particular CAP based on its maximal similarity to the predefined CAP centroids from the main cohort data. The purpose of doing this was to make the results comparable and generalizable across datasets. This also avoided the potential stimulus-evoked contamination in the definition of CAPs, if otherwise resting state and task state were combined during k-means clustering. The CAP occurrence rate was calculated across trials for each time point following stimulus onset (t = 0) within the time window of 0 to 16 s for propofol-SHH and 0 to 10 s for neuropathological patients. The CAP occurrence rates for each time point (per condition and per participant) was corrected by subtracting the CAP occurrence rate at t = 0, yielding a relative change against the stimulus onset.

Psychiatric dataset

The data were obtained from the OpenfMRI database. It is a shared neuroimaging dataset from the University of California, Los Angeles Consortium from Neuropsychiatric Phenomics (29). The original dataset included 272 participants encompassing healthy individuals (n = 130) and individuals with psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia (n = 50), bipolar disorder (n = 49), and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (n = 43). Participants were excluded if they had no T1 images or resting-state data, the overall head motion range was above 3 mm, or the data had insufficient degree of freedom after band-pass filtering and motion scrubbing. This resulted in 116, 44, 49, and 39 participants for healthy individuals, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, respectively, in our analysis (248 in total).

As mentioned above, using maximal similarity to the predefined CAP centroids, we classified individual fMRI volumes into eight CAPs informed by the k-means clustering approach from main cohort data. Accordingly, this produced a time series of discrete CAP labels per participant. The occurrence rates of each CAP per participant were calculated.

Statistical analysis

We performed Spearman rank correlations between the occurrence rates of joint mirror motifs and individual CAPs, with the level of responsiveness. Conscious and recovery conditions were ranked at 3, intermediate conditions (propofol light sedation, PreLOR of ketamine induction, and patients with MCS) were ranked at 2, and unresponsive conditions (propofol general anesthesia and deep sedation, LOR due to ketamine, and patients with UWS) were ranked as 1. In addition, Student’s t tests (paired sample for propofol-SHH, propofol-WI, and ketamine; unpaired sample for neuropathological patients; two-sided) on the CAP occurrence rates were performed between conditions in each dataset. FDR correction (α < 0.05) was applied to correct for multiple comparisons.

To examine whether the persistence probabilities significantly deviated from uniformly random sequences, we generated null CAP time series by 1000 permutations, randomly and uniformly exchanging CAP positions in time, across the entire dataset. This null model was only used for assessing the statistical significance of CAP persistence for each condition alone (e.g., conscious state) but not for between conditions (see below). Because of the strong autocorrelation of fMRI signals, the CAP persistence probability shall be expected to be significantly higher than the null distribution. Therefore, this permutation test served as a proof of principle, which is not of interest in this study. To examine whether the transition probabilities and entropies of Markov trajectories significantly deviated from uniformly random sequences for a given condition (e.g., conscious state) and to examine the differences between conditions (e.g., conscious versus propofol) for transition probabilities, entropies of Markov trajectories, and persistence probability, we generated another null CAP time series by controlling the autocorrelation of fMRI signals (24). That is, we preserved dwell times (approximately preserved autocorrelative properties) but otherwise permutated CAP cluster labels 1000 times across the entire dataset. Accordingly, the transition probabilities, entropies of Markov trajectories, and persistence probabilities for each surrogate condition (corresponding to the null time series) were calculated 1000 times to form null distributions for each condition. The deviation of each condition from null (except for the persistence probability that was tested by the first null model) and the deviation of differences between conditions from the null differences were determined at the significance level of P < 0.001 by considering multiple comparison corrections (99.9th and 0.1th percentile of the null distributions; two-sided). Considering that our focus was the common and specific alterations between conscious and various unresponsive conditions, we did not assess the intermediate conditions (e.g., propofol light sedation, PreLOR during ketamine induction, and patients with MCS) and recovery conditions. We also collapsed the conscious conditions across the four datasets, and collapsed propofol-induced unresponsiveness of propofol-SHH and propofol-WI, to reduce the complexity of comparisons. These yielded four conditions with one conscious and three unresponsive conditions: propofol, ketamine, and patients with UWS.

For conventional static functional connectivity analysis, group-level t tests (two-sided) on the functional connectivity values were performed, and significance was determined at FDR-corrected α < 0.05. For stimulus modulation analysis, Student’s t tests (against zero; α < 0.05, FDR corrected; two-sided) for the CAP occurrence rate changes were performed during the peak period of stimulus-evoked fMRI signal activity (4 to 6 s) at the group level. For psychiatric dataset, comparisons of the CAP occurrence rates for healthy individuals versus schizophrenia, healthy individuals versus bipolar disorder, and healthy individuals versus attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder were performed at the group level by independent sample t tests (two-sided; α < 0.05, FDR corrected).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Northoff, X. Wu, and P. Qin who shared the neuropathological data. We also appreciate assistance of X. Liu, K. Lauer, C. Roberts, S. Liu, S. Gollapudy, and W. Gross in performing the anesthetic procedures at the MCW and of Y. Chen, J. Xu, X. Li, Z. Yang, and J. Zhang in performing the anesthetic procedures at the Huashan Hospital. Funding: This study was supported by Medical Guidance Supporting Project from Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission No. 17411961400 (to J.Z.), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project No. 2018SHZDZX01 (to J.Z.), and ZJLab. This study was also supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH under award R01-GM103894 (to A.G.H.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Author contributions: Z.H., J.Z., and A.G.H. designed the study. J.Z. and J.W. conducted the experiment, performed the anesthetic procedures, and collected the data of propofol-SHH and ketamine. A.G.H. collected the data of propofol-WI. Z.H. conducted the experiment and collected the task fMRI data in neuropathological patients. Z.H. and A.G.H. conceptualized the data analyses. Z.H. analyzed the entire dataset and prepared the figures. Z.H., G.A.M., and A.G.H. interpreted the data and edited the manuscript. Z.H., J.Z., G.A.M., and A.G.H. wrote the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors. The psychiatric dataset is available at OpenfMRI (https://openfmri.org/dataset/ds000030/).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/11/eaaz0087/DC1

Fig. S1. k-means clustering approach and evaluations of k.

Fig. S2. CAPs identified from k = 2 to k = 16 with and without GSR.

Fig. S3. Spatial characteristics of the CAPs.

Fig. S4. Scatterplots and statistics for the Spearman rank correlations between the occurrence rate of joint mirror motifs or individual CAPs and the level of responsiveness.

Fig. S5. CAP occurrence rates of different conditions from k = 4 to k = 12 with and without GSR.

Fig. S6. In-degree CAP accessibility of different conditions from k = 4 to k = 12 with and without GSR.

Fig. S7. Classifying conscious versus unresponsive states using SVM.

Fig. S8. Conventional static functional connectivity.

Fig. S9. The association between CAP occurrence rates and anticorrelations from k = 4 to k = 12 with and without GSR.

Table S1. A summary of statistics for Fig. 2 (B to E).

Movie S1. CAP temporal dynamics.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Fox M. D., Snyder A. Z., Vincent J. L., Corbetta M., Van Essen D. C., Raichle M. E., The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 9673–9678 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbetta M., Shulman G. L., Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 201–215 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fornito A., Harrison B. J., Zalesky A., Simons J. S., Competitive and cooperative dynamics of large-scale brain functional networks supporting recollection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12788–12793 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Perri C., Bahri M. A., Amico E., Thibaut A., Heine L., Antonopoulos G., Charland-Verville V., Wannez S., Gomez F., Hustinx R., Tshibanda L., Demertzi A., Soddu A., Laureys S., Neural correlates of consciousness in patients who have emerged from a minimally conscious state: A cross-sectional multimodal imaging study. Lancet Neurol. 15, 830–842 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carhart-Harris R. L., Friston K. J., The default-mode, ego-functions and free-energy: A neurobiological account of Freudian ideas. Brain 133, 1265–1283 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raichle M. E., The brain’s default mode network. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 38, 433–447 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demertzi A., Soddu A., Laureys S., Consciousness supporting networks. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 23, 239–244 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanhaudenhuyse A., Demertzi A., Schabus M., Noirhomme Q., Bredart S., Boly M., Phillips C., Soddu A., Luxen A., Moonen G., Laureys S., Two distinct neuronal networks mediate the awareness of environment and of self. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23, 570–578 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vossel S., Geng J. J., Fink G. R., Dorsal and ventral attention systems: Distinct neural circuits but collaborative roles. Neuroscientist 20, 150–159 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boveroux P., Vanhaudenhuyse A., Bruno M.-A., Noirhomme Q., Lauwick S., Luxen A., Degueldre C., Plenevaux A., Schnakers C., Phillips C., Brichant J.F., Bonhomme V., Maquet P., Greicius M. D., Laureys S., Boly M., Breakdown of within- and between-network resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging connectivity during propofol-induced loss of consciousness. Anesthesiology 113, 1038–1053 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonhomme V., Vanhaudenhuyse A., Demertzi A., Bruno M.A., Jaquet O., Bahri M. A., Plenevaux A., Boly M., Boveroux P., Soddu A., Brichant J. F., Maquet P., Laureys S., Resting-state network-specific breakdown of functional connectivity during ketamine alteration of consciousness in volunteers. Anesthesiology 125, 873–888 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Threlkeld Z. D., Bodien Y. G., Rosenthal E. S., Giacino J. T., Nieto-Castanon A., Wu O., Whitfield-Gabrieli S., Edlow B. L., Functional networks reemerge during recovery of consciousness after acute severe traumatic brain injury. Cortex 106, 299–308 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy K., Birn R. M., Handwerker D. A., Jones T. B., Bandettini P. A., The impact of global signal regression on resting state correlations: Are anti-correlated networks introduced? Neuroimage 44, 893–905 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson J. S., Druzgal T. J., Lopez-Larson M., Jeong E.K., Desai K., Yurgelun-Todd D., Network anticorrelations, global regression, and phase-shifted soft tissue correction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 32, 919–934 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy K., Fox M. D., Towards a consensus regarding global signal regression for resting state functional connectivity MRI. Neuroimage 154, 169–173 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barttfeld P., Uhrig L., Sitt J. D., Sigman M., Jarraya B., Dehaene S., Signature of consciousness in the dynamics of resting-state brain activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 887–892 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demertzi A., Tagliazucchi E., Dehaene S., Deco G., Barttfeld P., Raimondo F., Martial C., Fernández-Espejo D., Rohaut B., Voss H. U., Schiff N. D., Owen A. M., Laureys S., Naccache L., Sitt J. D., Human consciousness is supported by dynamic complex patterns of brain signal coordination. Sci. Adv. 5, eaat7603 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golkowski D., Larroque S. K., Vanhaudenhuyse A., Plenevaux A., Boly M., Di Perri C., Ranft A., Schneider G., Laureys S., Jordan D., Bonhomme V., Ilg R., Changes in whole brain dynamics and connectivity patterns during sevoflurane- and propofol-induced unconsciousness identified by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Anesthesiology 130, 898–911 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudetz A. G., Liu X., Pillay S., Dynamic repertoire of intrinsic brain states is reduced in propofol-induced unconsciousness. Brain Connect. 5, 10–22 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tagliazucchi E., Chialvo D. R., Siniatchkin M., Amico E., Brichant J.F., Bonhomme V., Noirhomme Q., Laufs H., Laureys S., Large-scale signatures of unconsciousness are consistent with a departure from critical dynamics. J. R. Soc. Interface 13, 20151027 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X., Zhang N., Chang C., Duyn J. H., Co-activation patterns in resting-state fMRI signals. Neuroimage 180, 485–494 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X., Chang C., Duyn J. H., Decomposition of spontaneous brain activity into distinct fMRI co-activation patterns. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 7, 101 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X., Duyn J. H., Time-varying functional network information extracted from brief instances of spontaneous brain activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 4392–4397 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornblath E. J., Ashourvan A., Kim J. Z., Betzel R. F., Ciric R., Baum G. L., He X., Ruparel K., Moore T. M., Gur R. C., Gur R. E., Shinohara R. T., Roalf D. R., Satterthwaite T. D., Bassett D. S., Context-dependent architecture of brain state dynamics is explained by white matter connectivity and theories of network control. bioRxiv, 412429 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekroot L., Cover T. M., The entropy of Markov trajectories. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 39, 1418–1421 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dimitriadis S. I., Salis C. I., Mining time-resolved functional brain graphs to an EEG-based chronnectomic brain aged index (CBAI). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 423 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]