Abstract

The presence of active neurogenic niches in adult humans remains controversial. We focused attention to human olfactory neuroepithelium (OE), an extracranial site supplying input to the olfactory bulbs of the brain. Using single-cell RNA-sequencing analyzing 28,726 cells, we identified neural stem/progenitor cell pools and neurons. Additionally, we detailed expression of 140 olfactory receptors. These data from the OE niche provide evidence that neuron production may continue for decades in humans.

Mitotic tracing, fate mapping, and single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) analyses have shown that rodent OE supports ongoing neurogenesis through adulthood, i.e. up to 2 years of age1–6, but there has been little direct evidence to evaluate how well human olfactory neurogenesis may persist for the longer lifespan of many decades. Extrapolating from rodent studies, descriptive immunohistochemistry using human OE suggested progenitors may be present, but also identified species-related differences7,8. In addition, light microscopy examination of adult non-human primate OE described basal cell pools, although ages were not specified9. To investigate for the presence of true neurogenic progenitors and nascent neurons, we obtained fresh tissue samples from adult patients undergoing endoscopic nasal surgery involving resection of the anterior skull base or wide dissection for neurosurgical access (n=7 subjects). These cases provided access to normal olfactory cleft or turbinate tissue, uninvolved with any pathology but requiring removal (Supplementary Table 1). Samples were processed for scRNA-seq (4 cases) and/or immunohistochemistry.

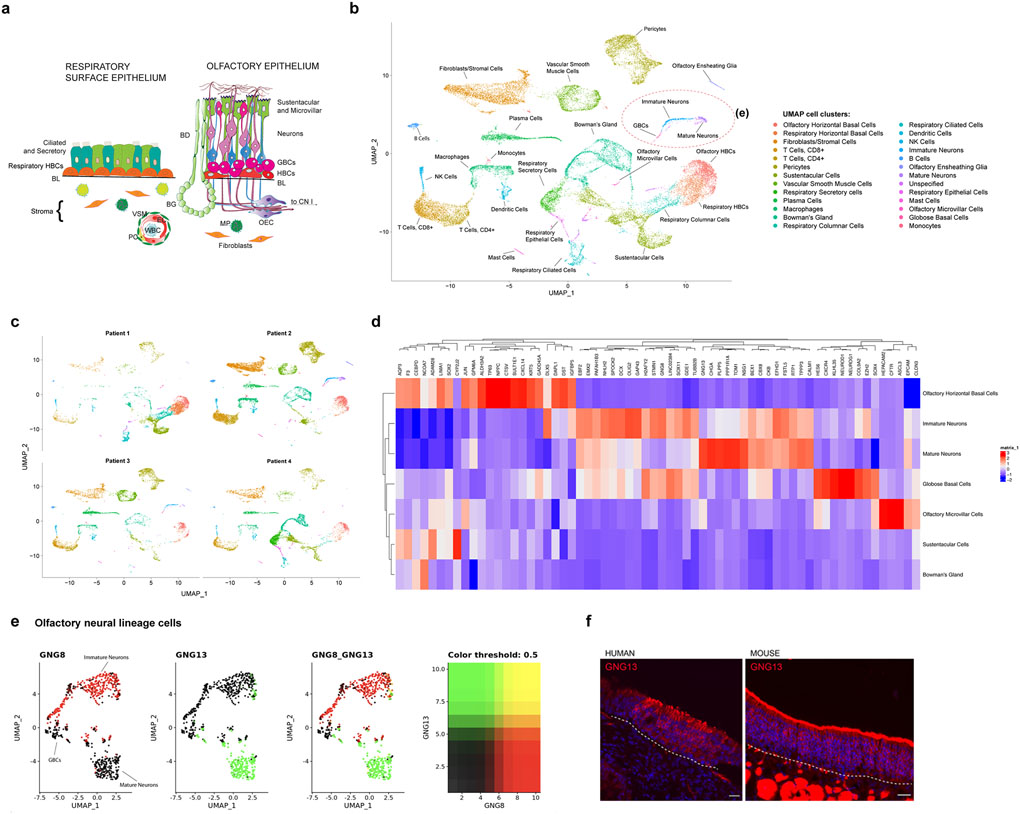

After filtering, analysis of 28,726 single cells was performed (5,538–11,184 cells per case; Fig. 1; Extended Data Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 2). Data were projected onto two dimensions via uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) to analyze cellular heterogeneity10,11. Cell type assignments for each cluster were generated using Gene Ontology and pathway analysis, and using multiple known murine marker genes for horizontal basal cells (HBCs), globose basal cells (GBCs), immature olfactory neurons, mature olfactory neurons, as well as Bowman’s glands, OE sustentacular cells5, endothelial/perivascular cells12, or immune cells (Fig. 1b–d and Extended Data Fig. 1). While our samples were comprised of olfactory and respiratory-containing mucosa, the olfactory neuroepithelial cells clustered distinctly from other cell types (Fig. 1a–c), and aggregated together in batch-corrected samples pooled from separate subjects (Fig. 1b, c). We hypothesized that, if ongoing neurogenesis is prominent in adult human OE, a small subset of cells should express the GBC proneural genes, as in rodent, and that immature neurons should be identifiable. Our results indicated that cell populations present in olfactory mucosa from adult subjects (age 41–52 years) contained several stages of neurogenic pools and immature neurons (Fig. 1d, e; Fig. 2; Extended Data Fig. 2, 3).

Fig. 1 |. Aggregate analysis of 28,726 single cells from human olfactory cleft mucosa.

a, Schematic diagram of the respiratory epithelium versus olfactory epithelium. Abbreviations: globose basal cells (GBCs), Horizontal basal cells (HBCs), Bowman’s ducts (BD), Bowman’s glands (BG), Vascular smooth muscle (VSM), Endothelial cell (EC), Pericyte (PC) White blood cell (WBC), Macrophage (MP), Olfactory ensheathing cell (OEC), Cranial Nerve I (CN1), basal lamina (BL) . b, UMAP dimensionality reduction plot of 28,726 combined olfactory and respiratory mucosal cells, n=4 patients. Cell cluster phenotype is noted on color key legend/labels. c, Plots of individual patient samples, n=4 patients. Patient 1: 5,683 cells; Patient 2: 11,184 cells; Patient 3: 5,538 cells; Patient 4: 6,321 cells; see also Extended Data Fig. 1c. d, Heatmap depicting selected gene expression among olfactory cell clusters. e, UMAP depicting GNG8 and GNG13 expression in 694 GBCs, immature olfactory neurons, and mature olfactory neurons, n=4 patients. f, GNG13 immunostaining (red) in adult human and mouse OE; dashed line marks basal lamina; nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Immunostaining was conducted in triplicate with similar results. Scale bar, 25 μm.

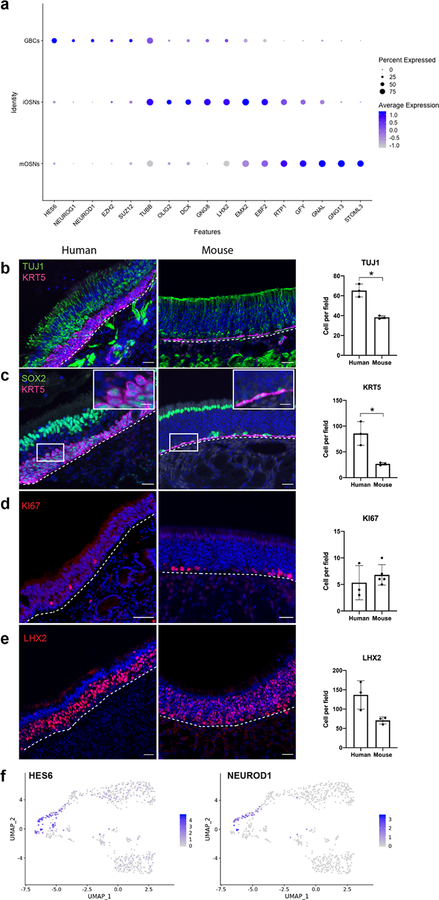

Fig. 2 |. Gene expression analysis of human OE.

a, DotPlot visualization of neuron lineage cell populations from adult human OE, n=4 patients; iOSN, immature olfactory sensory neuron; mOSN, mature olfactory sensory neuron. b-e, Cell type-specific marker validation in human versus mouse olfactory mucosal sections. TUJ1 labels somata of iOSNs, which are more abundant in our adult human samples (n=3, two-sided Welch’s t-test, p=0.015). SOX2 marks basal and sustentacular cells; KRT5 labels HBCs, which in many areas in human samples have a reactive rather than flat morphology (boxed region, enlarged) and are abundant (n=3, two-sided Welch’s t-test, p=0.04). Measure of center and error bars for b-e are mean ± standard deviation. KI67 marks proliferative GBCs. LHX2 was highly expressed in iOSNs (DotPlot in a); IHC confirms widespread expression in human and variable expression in mouse; nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue); dashed line marks basal lamina. Scale bar, 50μm; 10 μm in inset in c. f, Focused UMAP plots visualizing gene expression of HES6 and NEUROD1 in GBCs, n=4 patients.

In the scRNA-seq data, immature neurons represented a surprisingly large proportion (55%) of all human olfactory neurons. In contrast, in adult unlesioned rodent OE, markers for immature neurons, such as TUJ1 or GAP43, label only about 5–15% of all olfactory neurons, based on widely published staining patterns2; while published high-quality murine scRNA-seq data sets analyzed cells from postnatal mice, limiting the ability for direct comparison5. We found here that in human OE the G-protein subunit GNG8 is highly enriched in immature neurons, while GNG13 marks mature neurons, as described in mouse5 (Fig. 1e, f). A subset analysis of olfactory neural lineage cell clusters, re-projected via UMAP, demonstrated the largely distinct expression patterns for GNG8 and GNG13 (Fig. 1e). In agreement, by immunohistochemistry (IHC) GNG13 protein expression localizes to the mature olfactory neuron regions in both human and mouse OE (Fig. 1f), and a panel of IHC cell type-specific markers identified abundant immature cells in human OE, indicating that a selective loss of mature cells during sample processing is unlikely to account for the scRNA-seq findings (Fig. 2). In addition, populations of resident or activated leukocytes were prominent in samples from all patients (Extended Data Fig. 4), suggesting the potential for immune responses to influence tissue homeostasis in the OE, as shown in murine models of cytokine overexpression13.

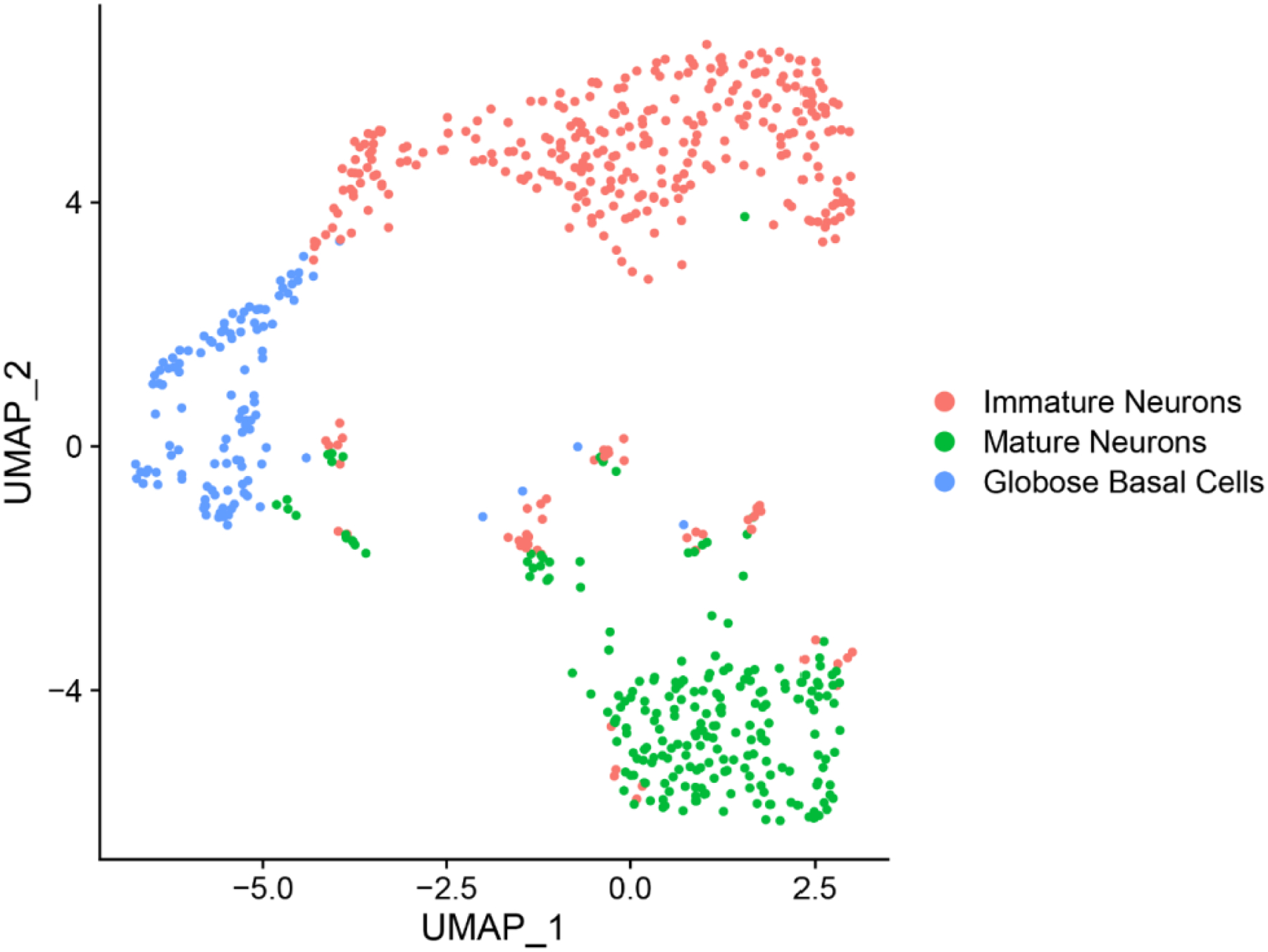

Focusing attention to the olfactory populations, neurogenic GBCs, defined by expression of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors HES6, NEUROG1 or NEUROD1, were a distinct cluster in the UMAP plots (see Fig. 1b, d, e, 2f;), representing approximately 2% of all OE cells (see also Extended Data Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 2). Differences in gene expression among the GBCs, immature and mature neuron clusters are apparent in DotPlot visualization (Fig. 2a), which also depicts the transition in marker expression from GBC to immature neuron to mature neuron, when focusing on transcription factors and olfactory transduction components. Additional data tables provide a resource of human OE population gene expression lists (Supplementary Tables 3–6). Selected pathway analyses from differential expression data infer chemosensory or progenitor cell phenotypes (Extended Data Fig. 6). To further verify the scRNA-seq findings, we compared human and mouse IHC using available validated antibodies for cell type-specific markers (Fig. 2). IHC supported the conclusion that immature neurons, labeled by antibody TUJ1 against the TUBB gene indicated on DotPlot, are more numerous in our human OE samples compared to adult mouse (Fig. 2b). Also, human samples often contained KRT5+/SOX2+ HBCs with a rounded or layered “reactive” morphology, rather than the flat monolayer typical of quiescent mouse OE (Fig. 2b, c). Reactive morphology HBCs are well described in rodent OE during injury-induced epithelial reconstitution3,14. The proliferative GBC layer was visualized with anti-Ki67, and appears similar in human and mouse samples (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 2). Antibody to LHX2, a transcription factor critically important in regulation of OR gene expression in differentiating olfactory neurons15,16, brightly labels nuclei of immature neurons and weakly labels the mature neurons, consistent with DotPlot expression patterns (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 3).

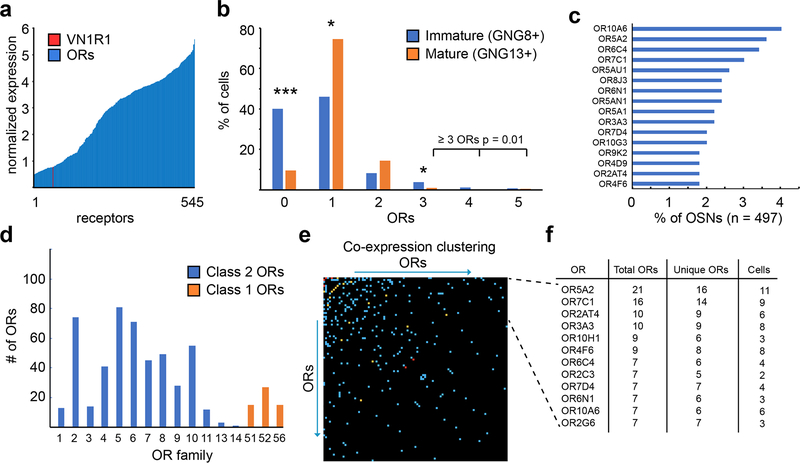

We focused further attention to OR expression, and detected the expression of 545 ORs across all neurons, from 140 different OR genes (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Tables 7–10). Excluding from analysis transcripts with low relative expression (Extended Data Fig. 7a), our data included one mature neuron expressing the vomeronasal type 1 receptor VN1R1, whose ligand hedione has been shown to elicit sex-specific human brain activity17 (Fig. 3a). Olfactory neuron identity was distinguished by co-expression of known olfactory transduction genes (see Fig. 2a); in the UMAP cell cluster labeled as “mature neurons”, 96% of cells express RTP1, 94% express GFY, 99% express GNAL, and 96% express GNG13 (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Tables 3, 5). In a sub-analysis of the neuron cluster cells (n = 668) expressing GNG8 (i.e. immature) and/or GNG13 (mature), fifty percent of GNG8+ cells expressed at least one olfactory receptor (OR) (Fig. 3b). In contrast, >85% of GNG13+/GNG8+ cells or GNG13+ cells expressed ORs. Significantly more immature olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) (40%) did not express any ORs, compared to mature OSNs (9.6%, Fig. 3b, p < 0.05). However, consistent with previous findings reporting that immature neurons are more likely to transiently express multiple ORs, as singular OR choice is not yet stabilized18, we found here that co-expression of >3 ORs was more often identifiable in immature OSNs compared to mature OSNs (p = 0.01). The “one-neuron/one-receptor” rule19,20 appeared to generally hold true, as most mature OSNs express only one OR (75%), with 14% expressing two and <1% expressing three (Fig. 3b). Cells with two ORs did not express more unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), suggesting that these were not the result of doublets (Extended Data Fig. 7b). While we have carefully considered numbers of genes and UMIs, it is important to consider other potential technical issues with this approach. For instance, one cannot completely exclude the possibility of a doublet from two low-quality libraries having a similar number of genes as a true single cell. Nonetheless, our data are consistent with singular OR expression in a majority of cells captured here. We found 8 ORs expressed in more cells than statistically expected, with OR10A6 being the most frequent OR, expressed in 5% of the OR-expressing neurons (Fig. 3c). Both, Class I and Class II OR receptors were identified (Fig. 3d). Six ORs were statistically more co-expressed than others (Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Table 9). We found similarities to murine olfactory neurons in terms of the high expression of non-OR GPCRs, including ADIPOR1, DRD2, TMEM181, ADGRL3, and GPRC5C, the latter encoding a retinoic acid inducible GPCR (Supplementary Table 10). DRD2 was noted to be highly neuron-specific, whereas the other non-OR GPCRs were also expressed in non-neuronal clusters. While we did not find other V1R receptors or trace amino acid receptors (TAARs), we cannot exclude their expression by cells not captured in our biopsies.

Fig. 3 |. Analysis of OR expression in human olfactory epithelium.

a, Expression level of all ORs (n = 545 total receptors) in immature (GNG8+) and mature (GNG13+) OSNs. Expression levels of a VN1R1 receptor in 1 cell is indicated in red. Y-axis represents normalized expression values, x axis individually expressed receptors. b, ORs expressed in individual immature and mature neurons. * p<0.05; *** p<0.001, two-sided χ2 test without Yates’ correction, n=3 patients. Y-axis represents percentage of cell population, x-axis the number of unique ORs per cell. c, Most commonly identified ORs in OSNs. The top 8 ORs in this list were detected statistically more than expected. d, Expression of OR families in immature and mature neurons; blue=Class II, orange=Class I ORs. e, Co-expression matrix of ORs; X- and Y- axis contain every OR found to be co-expressed with at least one other OR (n = 141, including VN1R1). Blue squares show expression of intersecting ORs co expressed in 1 cell, orange indicates 2 cells, and red 3 cells. f, List of most co-expressed ORs from Fig. 3e. “Total ORs” indicates sum of all ORs found co-expressed with indicated member, and “Unique ORs” the sum of unique OR genes co-expressed, in the indicated number of neuronal cells. The top six ORs in this list are statistically more co-expressed than expected.

Our findings provide direct evidence for ongoing robust neurogenesis in adult OE in humans. The presence and quantification of individual cell populations expressing features defining various stages from stem cell, progenitor cell, immature to mature neuron are clearly defined at single cell resolution. We identify here a high ratio of immature to mature neurons in the OE of middle-aged humans, which contrasts the typical populations present in adult rodents. In addition, we define a large set of ORs that appear to be expressed in human OE, and provide support for singular OR expression in mature olfactory neurons. Together, these results provide detailed novel insights into olfactory neurogenesis in the adult human.

Methods

Patients and sample collection.

Human tissue samples were obtained with patient informed consent and approval of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes. Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. Samples for scRNA-seq were randomly selected as they presented for routine clinical care. Tissue was obtained from patients undergoing transnasal endoscopic surgery to access the pituitary or anterior skull base (Supplementary Table 1). Mucosa was carefully excised from portions of the olfactory cleft along the superior nasal septum or adjacent superior medial vertical lamella of the superior turbinate, uninvolved with any pathology. Immediately following removal, samples were held on ice in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) and transported to the lab. Under a dissecting microscope, any bone or deep stroma was trimmed away from the epithelium and underlying lamina propria. A small portion of the specimen was sharply trimmed and snap frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) medium, to be cryosectioned for histology use. The remaining specimen was then enzymatically dissociated using collagenase I, dispase and DNase for approximately 30 min. Next, papain was added for 10 minutes, followed by trypsin 0.125% for 3 minutes. Cells were filtered through a 100 μm strainer, pelleted and washed and then treated with an erythrocyte lysis buffer and washed again. The cells were then resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% bovine serum albumin and immediately processed for scRNA-seq using the Chromium (10X Genomics) platform. Fresh human tissue samples used to generate scRNA-seq data were exhausted in the experimental process.

Single-cell RNA sequencing.

Single-cell RNA sequencing was performed using the Chromium (10X Genomics) instrument. Single cell suspensions were counted using both the Cellometer K2 Fluorescent Viability Cell Counter (Nexcelom) and a hemocytometer, ensuring viability >80%, and adjusted to 1,000 cells/μl. Samples 1 and 3 were run using the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Library & Gel Bead Kit v2 and Sample 2 and 4 was run using the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Library & Gel Bead Kit v3 (10X Genomics). The manufacturer’s protocol was used with a target capture of 10,000 cells for the 3’ gene expression samples. Each sample was processed on an independent Chromium Single Cell A Chip (10X Genomics) and subsequently run on a thermocycler (Eppendorf). 3’ gene expression libraries were sequenced using the NextSeq 500 high output flow cells.

Single-cell RNA-Seq analysis.

Raw base call (BCL) files were analyzed using CellRanger (version 3.0.2). The “mkfastq” command was used to generate FASTQ files and the “count” command was used to generate raw gene-barcode matrices aligned to the GRCh38 Ensembl build 87 genome. The data from all 4 samples was combined in R (3.5.2) using the Seurat package (3.0.0) and an aggregate Seurat object was generated21,22. To ensure our analysis was on high-quality cells, filtering was conducted by retaining cells that had unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) greater than 400, expressed 100 to 8000 genes inclusive, and had mitochondrial content less than 10 percent. This resulted in a total of 28,726 cells. Data for all 4 samples were combined using the Standard Integration Workflow (https://satijalab.org/seurat/v3.0/integration.html). Data from each sample were normalized using the NormalizeData() function and variable features were identified using FindVariableFeatures() with 5000 genes and the selection method set to “vst”, a variance stabilizing transformation. To identify integration anchor genes among the 4 samples the FindIntegrationAnchors() function was used with 30 principal components and 5000 genes. Using Seurat’s IntegrateData() the samples were combined into one object. The data was scaled using the ScaleData() function To reduce dimensionality of this dataset, principal component analysis (PCA) was used and the first 30 principal components further summarized using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) dimensionality reduction23. We chose to use 30 PCs based on results from analysis using JackStraw and elbow plots (Extended Data Fig. 8a, b). The DimPlot() function was used to generate the UMAP plots displayed. Clustering was conducted using the FindNeighbors() and FindClusters() functions using 30 PCA components and a resolution parameter set to 1.8. The original Louvain algorithm was utilized for modularity optimization24. The resulting 26 louvain clusters were visualized in a two-dimensional UMAP representation and were annotated to known biological cell types using canonical marker genes, as well as gene set enrichment analysis (EnrichR v2.1)25. QC plots depict UMI and gene distributions per cluster (Extended Data Fig. 9).The list of top significant genes for each cluster were input into EnrichR tool and the Gene Ontology, Cellular pathway and Tissue output terms were used to help verify that cell phenotype assignments were consistent with these outputs. The following cell types were annotated; selected markers are listed: CD8+ T Cells (CD3D, CD3E, CD8A), CD4+ T Cells (CD3D, CD3E, CD4, IL7R), NK Cells (FGFBP2, FCG3RA, CX3CR1), B cells (CD19, CD79A, MS4A1), Plasma cells (IGHG1, MZB1, SDC1, CD79A), Monocytes (CD14, S100A12, CLEC10A), Macrophages (C1QA, C1QB, C1QC), Dendritic cells (CD1C and lack of expression of C1QA, C1QB, and C1QC), Mast Cells (TPSB2, TPSAB1), Fibroblasts/Stromal Cells (LUM, DCN, CLEC11A), Respiratory Ciliated Cells (FOXJ1, CFAP126, STOMl3), Respiratory Horizontal Basal Cells (KRT5, TP63, SOX2), Respiratory Gland Progenitor Cells (SOX9, SCGB1A1), Respiratory Secretory Cells (MUC5, CYP4B1, TFF3), Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (TAGLN, MYH11), Pericytes (SOX17, ENG), Bowman’s Gland (SOX9, SOX10, MUC5, GPX3), Olfactory Horizontal Basal Cells (TP63, KRT5, CXCL14, SOX2, MEG3), Olfactory Ensheathing Glia (S100B, PLP1, PMP2, MPZ, ALX3), Olfactory Microvillar Cells (ASCL3, CFTR, HEPACAM2, FOXL1), Immature Neurons (GNG8, OLIG2, EBF2, LHX2, CBX8), Mature Neurons (GNG13, EBF2, CBX8, RTP1), Globose Basal Cells (HES6, ASCL1, CXCR4, SOX2, EZH2, NEUROD1, NEUROG1), and Sustentacular Cells (CYP2A13, CYP2J2, GPX6, ERMN, SOX2). To generate a heatmap (Fig. 1) of the cell types of interest (Bowman’s Gland, Olfactory Horizontal Basal Cells, Olfactory Microvillar Cells, Immature Neurons, Mature Neurons, Globose Basal Cells, and Sustentacular Cells) the Seurat subset() function was used followed by the AverageExpression() function to generate average RNA expression data for each cell type. Hierarchical clustering was conducted on the RNA averaged clusters with genes aggregated from the literature and visualized using ComplexHeatmap (1.20.0)26. Sub-analysis to count cells expressing GPCRs and other genes (Fig. 3) was done by extracting cells from the olfactory neuronal lineage clusters expressing GNG8 or GNG13, which includes some GBCs/nascent neurons, immature neurons, and mature neurons, see details below. For samples from subjects 2 and 3, the proportion of GBCs in OE was calculated based on total numbers of OE phenotypes per sample (HBCs, GBCs, iOSNs, mOSNs, microvillar cells, and sustentacular cells).

Single-cell neuron subpopulation analysis.

For the analysis we utilized the normalized expression data from the “Globose Basal Cells”, “Immature Neurons”, and “Mature Neurons” subsets to infer the relationship between these cell types. The subset() command was used with the option “do.clean” set to “TRUE”. A new analysis on this subset was performed on the neuronal subset using the FindVariableFeatures(), ScaleData(), RunPCA(), and RunUMAP() commands. New UMAP plots were generated for this subpopulation (Fig. 1e), along with feature plots for specific gene expression visualization (Fig. 2f). In addition DotPlots, in which the size of the circle indicates the percent of cells in a cluster expressing the marker and color indicates expression level, were generated to further visualize gene expression data, using the DotPlot function in Seurat (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 1,4,5). Sub-analysis to count cells expressing GPCRs and other genes (Fig. 3) was done by extracting cells from the olfactory neuronal lineage clusters. A cutoff of 0.5 normalized expression counts as determined by Seurat (log(reads*10000/total reads)) was applied (Extended Data Fig. 7a), which excluded approximately 15% of all data (considered low expression). Further, 0.5 is around 10% of the maximum expression detected; there are few observations >5 normalized expression values. Of note, >75% of ORs we report have an expression value >1, and over 50% have an expression value >2. While there is no clear guidance on what cutoffs are standard for scRNA-seq data, we regard our choice for reporting OR expression as stringent.

Statistical significance was calculated with the two-sided χ2 test without Yates’ correction, using RStudio version 1.0.143 and R version 3.4.0 with the chisq.test() function. Other analysis was performed using custom-coded python scripts (Supplementary Software, https://github.com/harbourlab/OR_SC_analysis). For OR co-expression, outlier test was performed assuming that data range should fall within Q3 + 1.5*IQR, with Q3 being the 75th percentile of the data, and IQR = Q3–Q1, Q1 being the 25th percentile (Fig. 3). Neurons expressing > 1 OR do not express significantly more genes, nor were significantly more UMIs detected (Extended Data Fig. 7b). UMIs are the number of unique molecular identifiers sequenced (number of unique transcripts). The UMI count is expected to double in bona fide doublets of similar cells due to the stochastic sequencing nature of the mixed library. While our findings generally support singular OR expression by olfactory neurons along with occasional cells expressing >1 OR, it is important to note that there are still other technical issues making it difficult to definitively exclude the possibility of multiple cells erroneously being considered as a single cell.

Gene set enrichment analysis.

The FindMarkers() command was used to conduct differential gene expression analysis between annotated clusters of interest. The “fgsea” package was utilized27 with default settings from the Reactome pathways vignette with the “reactome.db” package28 providing curated pathways from Reactome29. The top 50 pathways ranked by adjusted p-value were plotted in the visualization (Extended Data Fig. 6).

Immunohistochemistry.

Cryosections were prepared from nasal epithelium biopsies. Tissue was embedded in OCT compound and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, or was first fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 hours, rinsed in PBS, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS, then embedded and frozen. Sections 10μm thick were prepared using a Leica CM1850 cryostat and mounted onto Superfrost Plus Slides (VWR) and stored at −20°C. Sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (if not previously fixed), rinsed in PBS and processed for immunochemistry. After treatment with an ethanol gradient from 70-95-100-95-70%, PBS rinse, and any required pre-treatments, tissue sections were incubated in blocking solution with 10% donkey serum, 5% bovine serum albumin, 4% nonfat dry milk, 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 11) were diluted in this same solution and incubated overnight in a humidified chamber at 4°C.

Detection by species-specific fluorescent conjugated secondary antibodies, validated for multi-labeling, was performed at room temperature for 45 minutes. Sections were counterstained with 4’,6-daimidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and coverslips were mounted using Prolong Gold (Invitrogen) for imaging, using a Leica DMi8 microscope system. Images were processed using Fiji ImageJ software (NIH, vesion 2.0.0-rc-69/1.52p). Scale bars were applied directly from the Leica acquisition software metadata in ImageJ Tools. Adult C57BL6 (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) mouse cryosections were prepared as described previously30 and immunostained in parallel with human sections. Animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), University of Miami. Immunostaining for mouse tissue was performed on 3 independent mouse replicates for TUJ1, KRT5, LHX2 and 5 independent mouse replicates for KI67. For quantification (Fig. 2), we used human samples containing intact OE, rather than respiratory epithelium, with enough sections meeting criteria available from 3 subjects (case# 5,6,7), and quantified labeling from 20x fields in ≥2 sections per subject, using ImageJ. Data distribution was formally tested and found to normal. For IHC quantification comparisons the two-sided Welch’s t-test was utilized. Blinding was not feasible, as human and mouse histology contains obvious differences. No animals or data points were excluded from the analysis.

Statistics.

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. For each experiment, tissue samples from a single patient were processed individually. Single cell suspensions for each sample were processed for scRNA-seq (10x Genomics) in an independent Chromium chip. For IHC quantification comparisons the two-sided Welch’s t-test was utilized. For olfactory receptor analysis statistical significance was calculated with the two-sided χ2 test without Yates’ correction. For differential expression analysis in Seurat, the default two-sided non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was utilized with Bonferroni correction using all genes in the dataset.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Extended Data

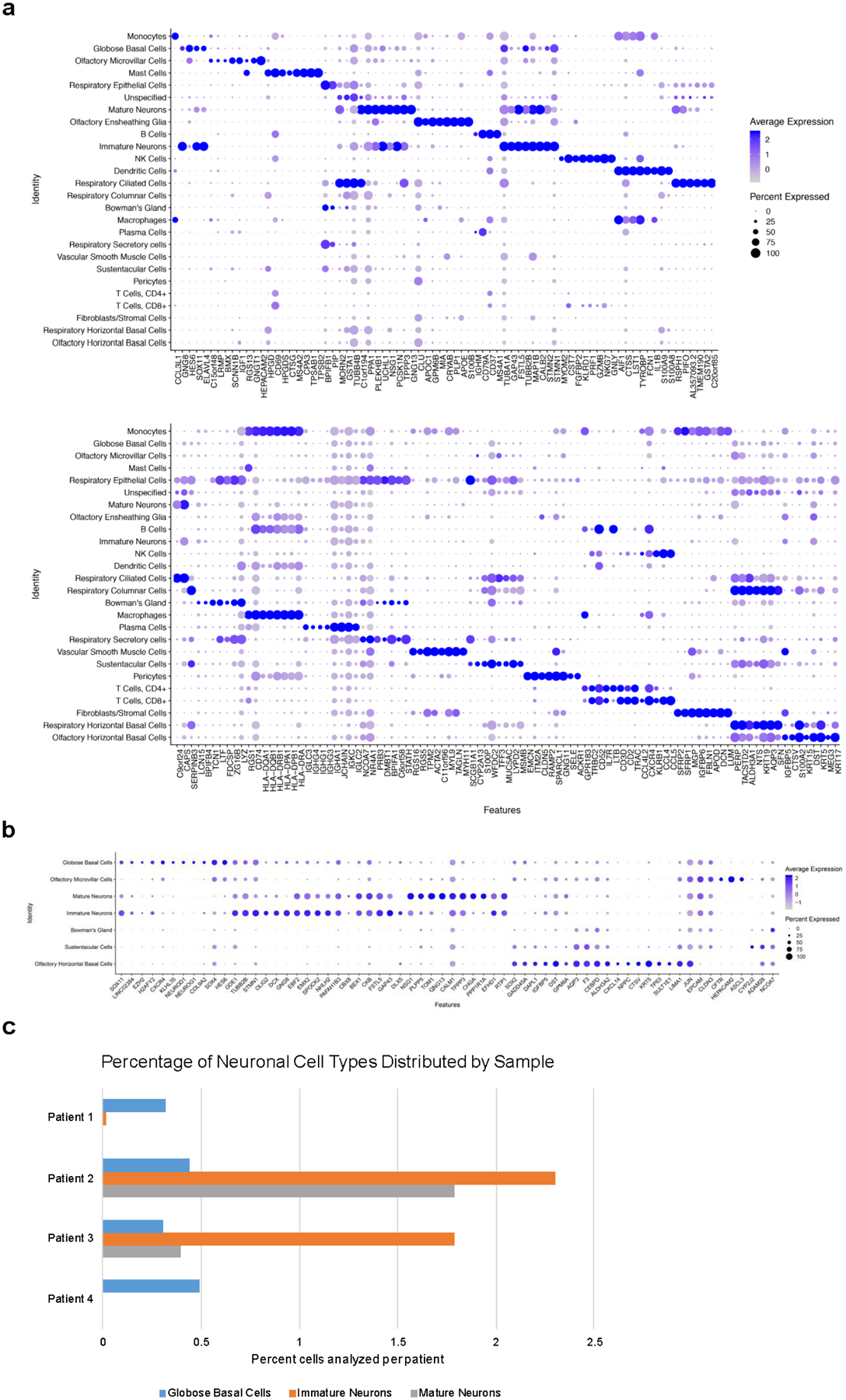

Extended Data Fig. 1. DotPlot visualization listing scRNA-seq clusters.

a, Cell phenotypes listed on y-axis, showing unbiased gene expression for the top 8 genes per cluster identified by log Fold Change; genes (features) are listed along the x-axis. Dot size reflects percentage of cells in a cluster expressing each gene; dot color reflects expression level (as indicated on legend). The plot depicts clusters from 28,726 combined olfactory and respiratory mucosal cells, n=4 patients. b, DotPlot visualization of the Heatmap shown in Fig. 1d. The plot depicts clusters from 28,726 combined olfactory and respiratory mucosal cells, n=4 patients. c, Histogram showing the neuronal lineage cell types captured by scRNA-seq, as a percentage of the total cells analyzed per patient; see Fig. 1c.

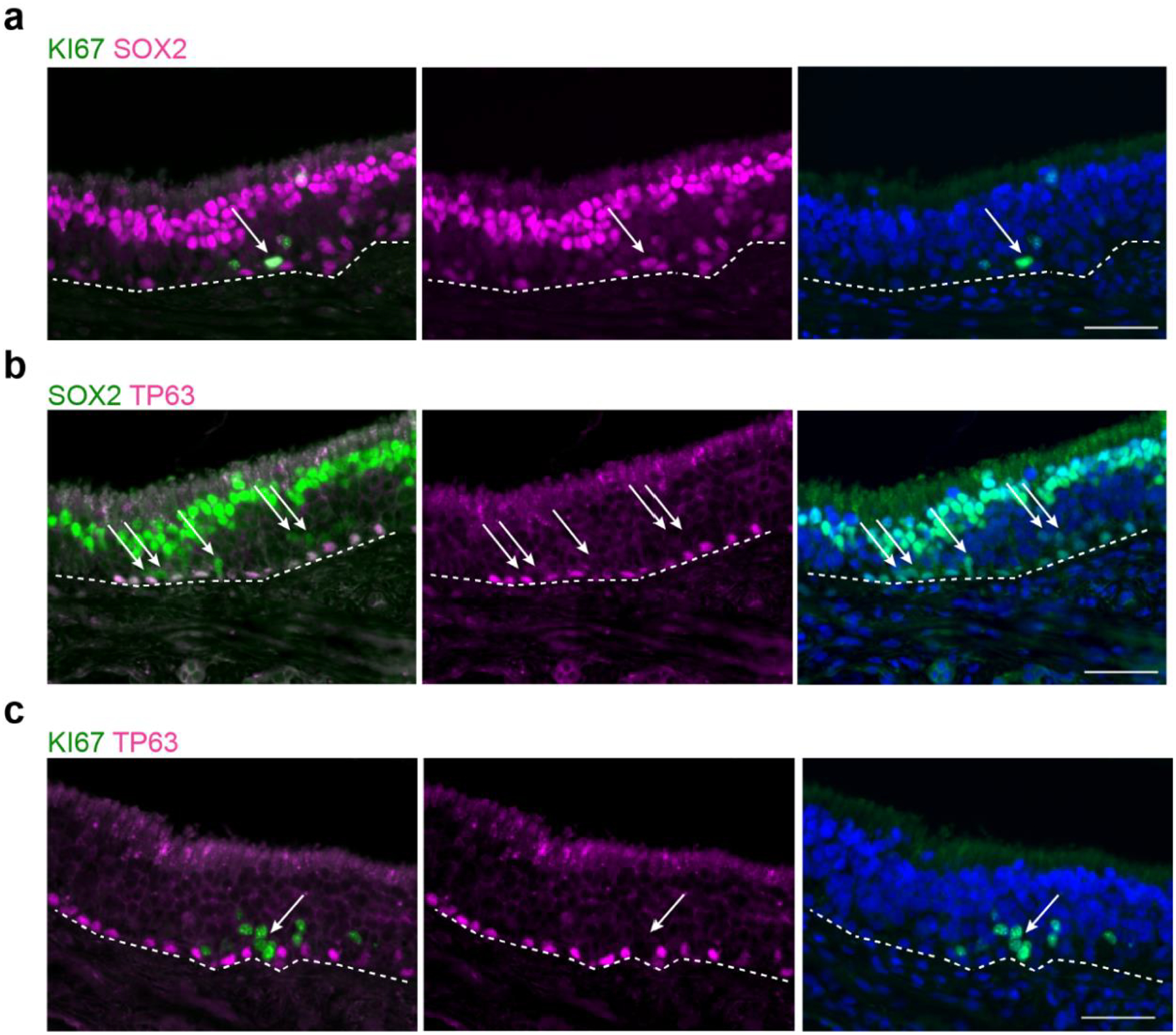

Extended Data Fig. 2. Additional human immunohistochemistry of basal cell populations.

Co-staining for SOX2, Ki67 or the HBC marker TP63. Proliferative activity has been used as a hallmark of the globose basal cell (GBC) phenotype. We reasoned that, although some proliferating cells in the olfactory epithelium (OE) might be immune or inflammatory cells, proliferative cells within the GBC layers of the OE that are SOX2+/Ki67+/TP63− would be categorized as GBCs. a, Sustentacular cell nuclei at the top of the OE are SOX2-bright; and horizontal basal cells (HBCs) and a subset of GBCs are SOX2+, although less intensely. Arrow marks a SOX2+/KI67+ cell among the proliferative KI67+ basal region, consistent with the GBC phenotype. b, SOX2 co-localizes with TP63 in HBCs; arrows mark Sox2+/TP63− GBCs. c, TP63+ HBCs are mitotically quiescent, while many GBCs are actively proliferating, often in scattered cell clusters. Arrow marks a cluster of KI67+/TP63− basal cells. Dashed line indicates basal lamina. Immunostaining for a-c was conducted in triplicate with similar results. Bar, 50 μm.

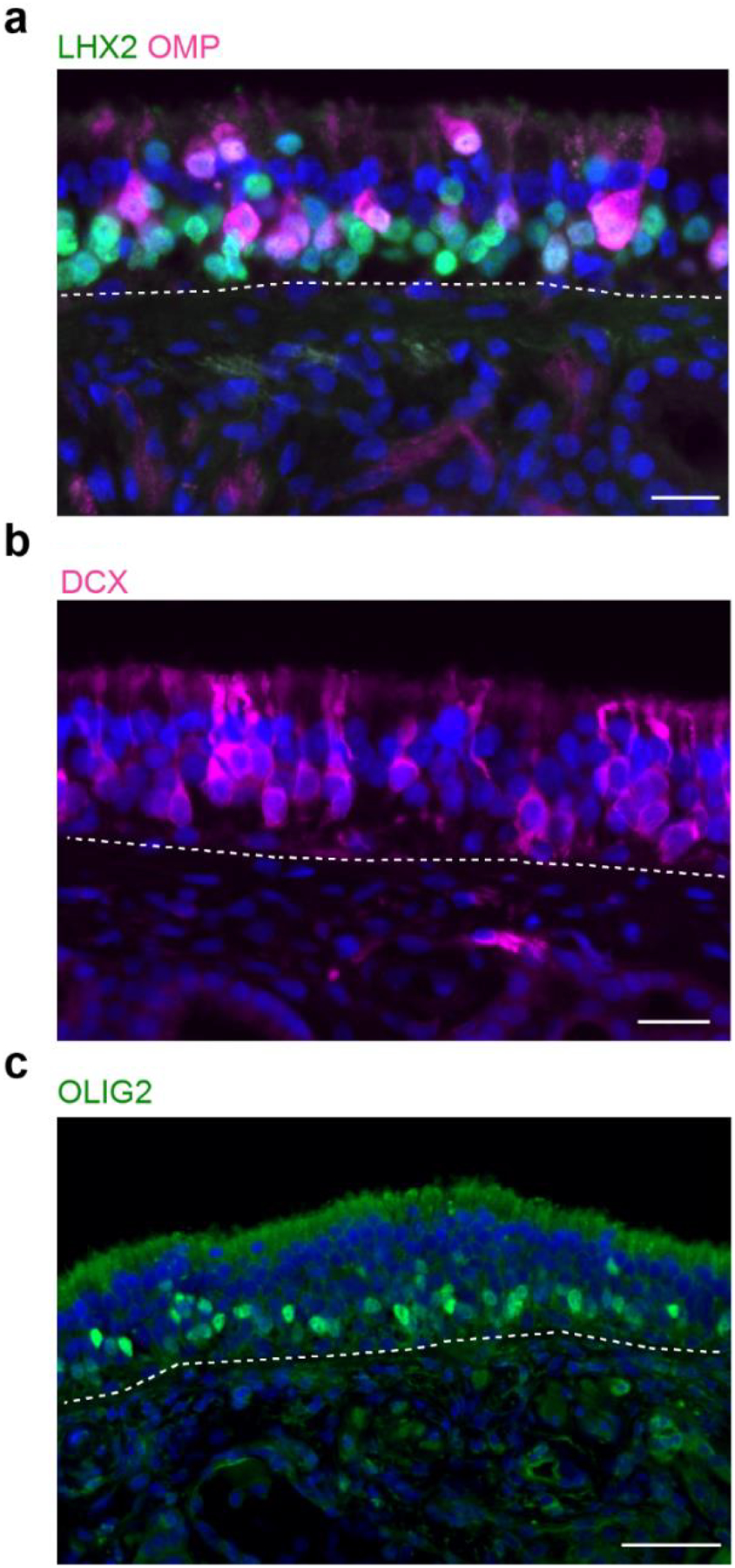

Extended Data Fig. 3. Additional human immunohistochemistry (IHC) of immature and mature olfactory sensory neurons (OSN) populations.

a, Co-staining for LHX2 and OMP demonstrates many LHX2+/OMP− neurons, distributed in deeper layers of the OE, which are immature OSNs; OMP is a marker for fully differentiated OSNs, while LHX2 expression in differentiating OSNs orchestrates OR receptor expression. b, DCX was identified by scRNA-seq here as enriched in immature OSNs (see Fig. 2a). IHC confirms scattered DCX+ neuronal somata and dendrites in the OE. c, Similarly, the bHLH transcription factor OLIG2 was identified to be enriched in immature OSNs; IHC confirms nuclear expression in the deeper OSN layers of OE tissue. Dashed line indicates basal lamina. Immunostaining for a-c was conducted in triplicate with similar results. Bar, 25 μm.

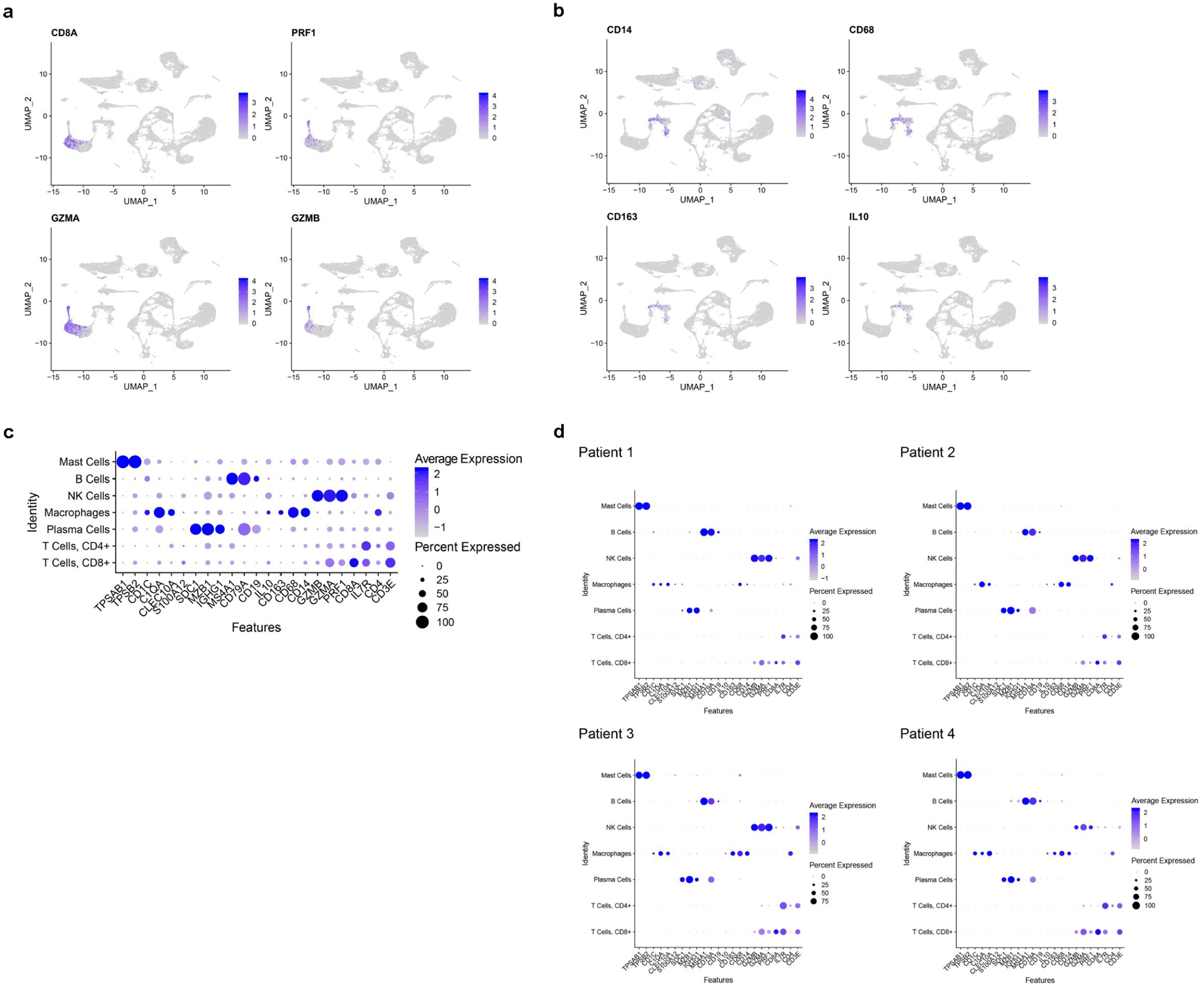

Extended Data Fig. 4. Analysis of immune cell populations.

Feature plots indicate expression of inflammatory cell markers in human nasal biopsy samples. UMAP clustering identifies lymphocyte populations; a, cytotoxic T cell markers co-localize including CD8A, PRF1, GZMA and GZMB. The plot depicts clusters from 28,726 combined olfactory and respiratory mucosal cells, n=4 patients. b, Within the monocyte/macrophage populations (CD14+, CD68+ cells), markers for activated M2 macrophages, such as CD163 and IL10, are indicated. The plot depicts clusters from 28,726 combined olfactory and respiratory mucosal cells, n=4 patients. c, DotPlot visualization of additional immune cell gene expression from combined aggregate samples. Cell cluster identity is listed on the y-axis, genes (Features) are listed on x-axis. The plot depicts clusters from 28,726 combined olfactory and respiratory mucosal cells, n=4 patients. d, Immune cell DotPlots showing the contribution of cell types and gene expression patterns by individual patient sample. The plot depicts clusters from 28,726 combined olfactory and respiratory mucosal cells, n=4 patients.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Focused UMAP plot of OE neuronal lineage populations, with cell phenotype assignments indicated.

Compare with gene expression feature plots in Fig. 1e and 2f. The plot depicts clusters from 694 GBCs, immature olfactory neurons and mature olfactory neurons, n=4 patients.

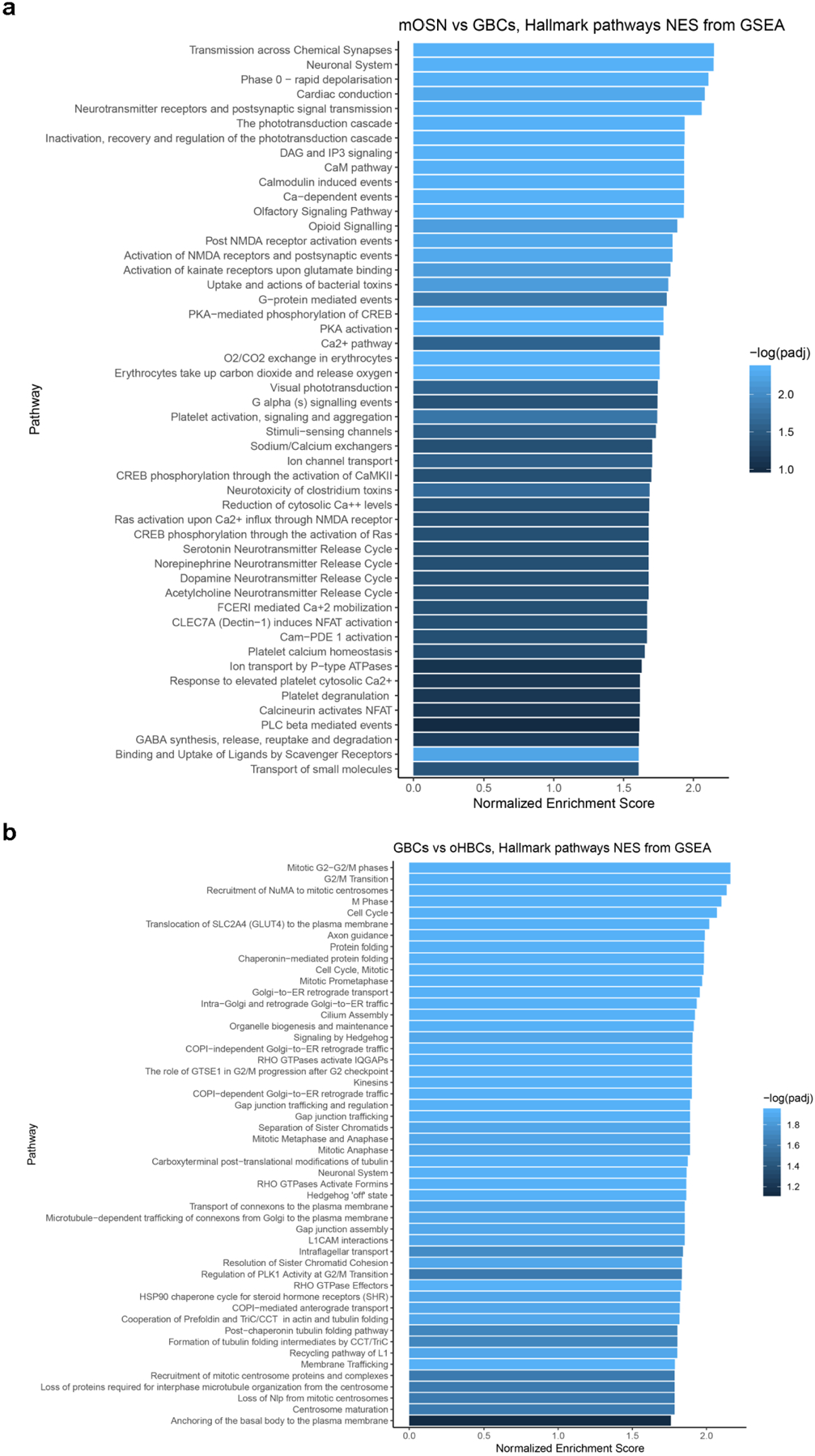

Extended Data Fig. 6. Gene set enrichment analysis on differential expression data from selected cell clusters.

The top 50 Reactome pathways ranked by adjusted p-value were plotted in the visualization. a, mOSNs versus GBCs; many top terms involve neuronal, transduction and synapse function. The differential expression was calculated from 222 mOSNs and 115 GBCs, n=4 patients. The default two-sided non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was utilized with bonferroni correction using all genes in the dataset. b, GBCs versus olfactory HBCs; top terms include cell cycle or neurogenesis functions. The differential expression was calculated from 115 GBCs and 2,182 olfactory HBCs, n=4 patients. The default Seurat two-sided non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was utilized with bonferroni correction using all genes in the dataset.

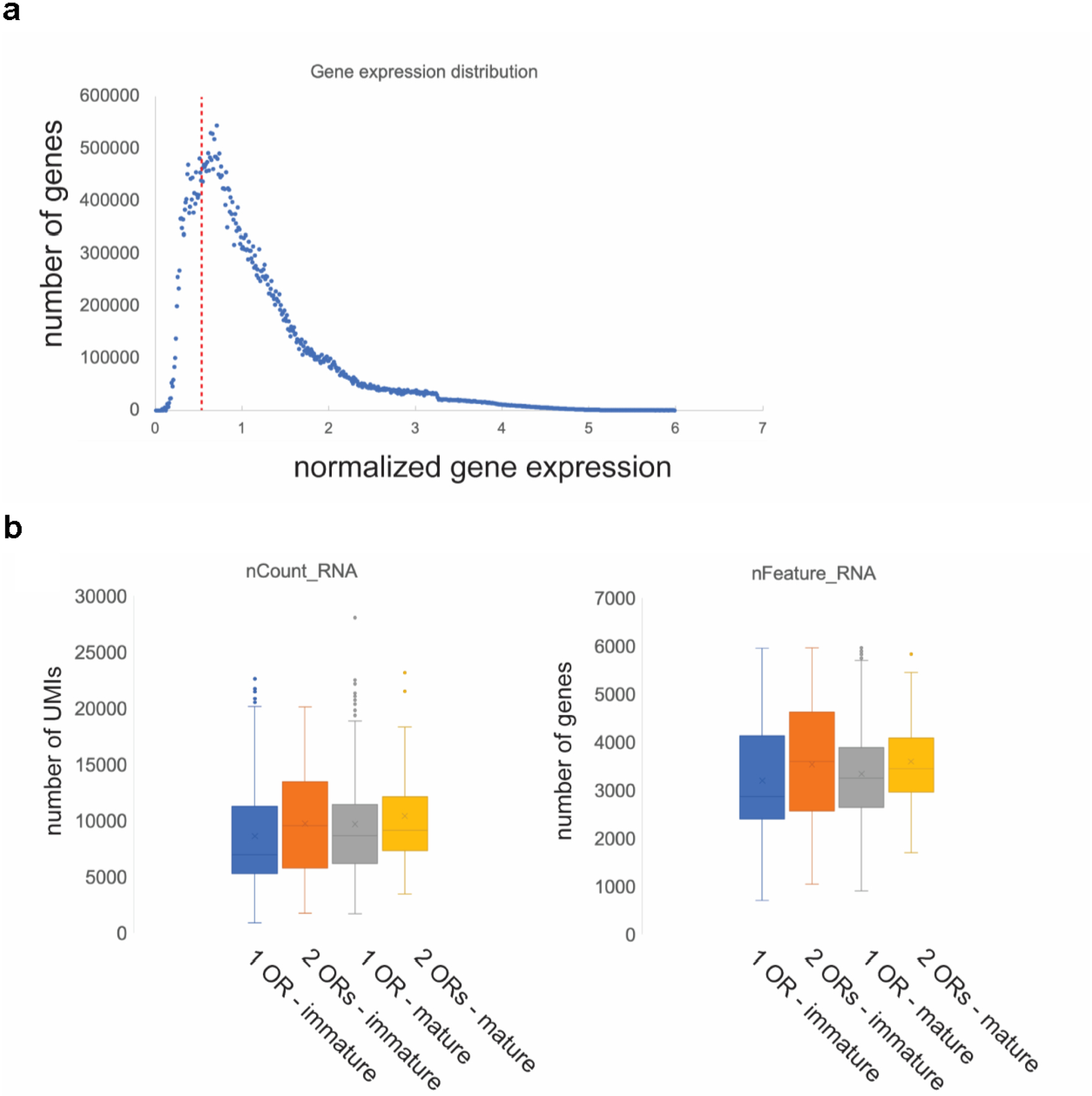

Extended Data Fig. 7. OR gene expression in human olfactory neurons.

a, Range of gene expression in our datasets (binned to 0.01). We identified 4.80E+07 observations (gene expression measurements) expressing >0. Genes with no expression (=0, n=532063621) were excluded in this plot. The distribution plot shows that choosing a cutoff of 0.5 (red vertical dotted line). b, Doublet analysis. Box plots depicting the number of UMIs (“nCount_RNA”, left plot), and genes (“nFeature_RNA”, right plot) in immature and mature neurons expressing 1 or 2 ORs.

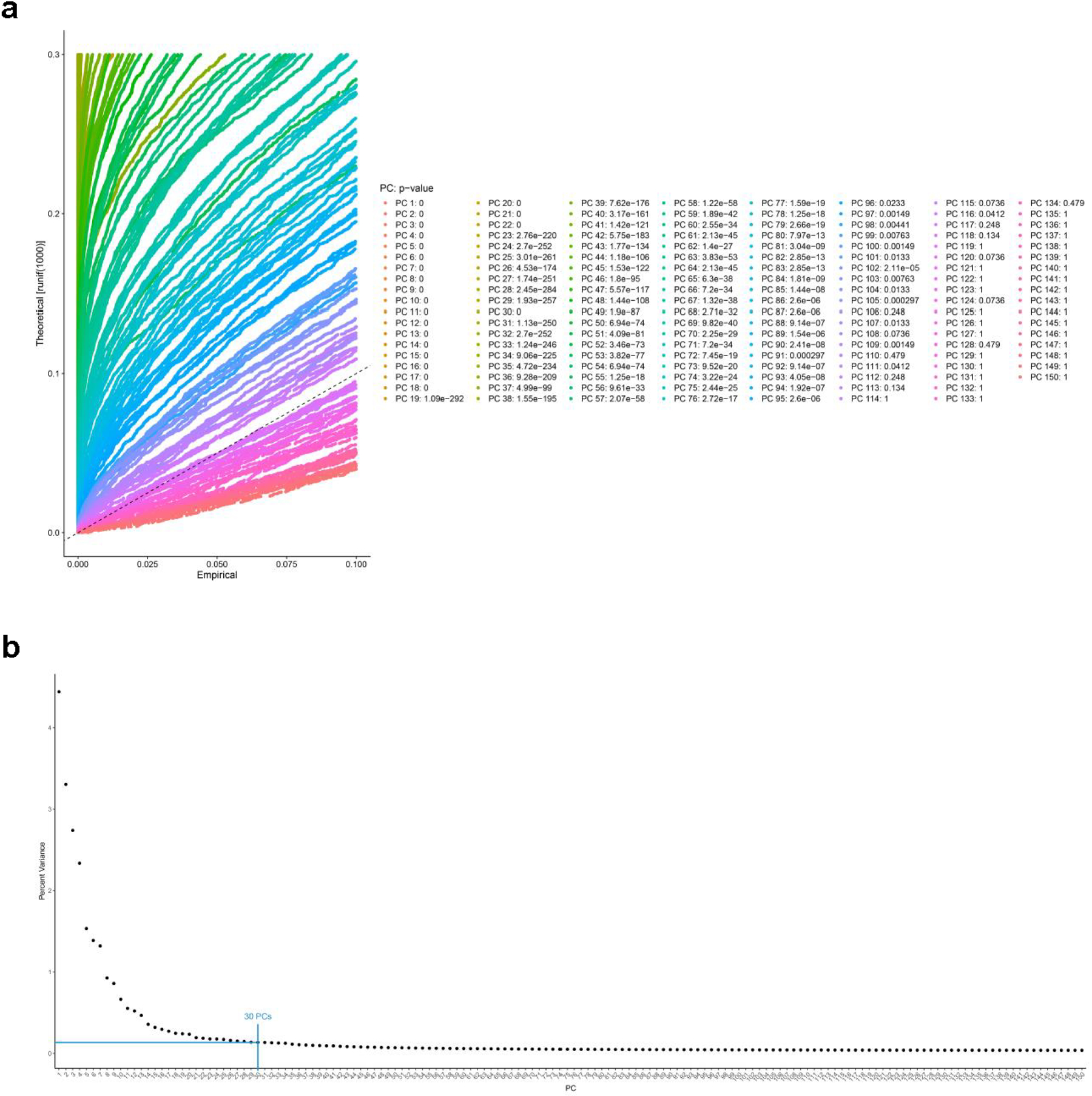

Extended Data Fig. 8. Principal component determination analysis.

The 4-patient combined data set was analyzed in Seurat to explore p principal components (PCs) contributing to heterogeneity, and to determine an appropriate PC selection. a, Using the JackStraw approach, approximately 100 PCs had low a p-value. The plot depicts PC calculated from from 28,726 combined olfactory and respiratory mucosal cells, n=4 patients. The jackstraw test implemented in Seurat was used to calculate p-values of PCs. b, To select a suitable number of PCs for downstream analysis, we used the elbow plot heuristic approach, indicating that beyond 20–30 PCs, very little additional variation is explained. Therefore, for downstream analysis we chose to include 30 PCs.

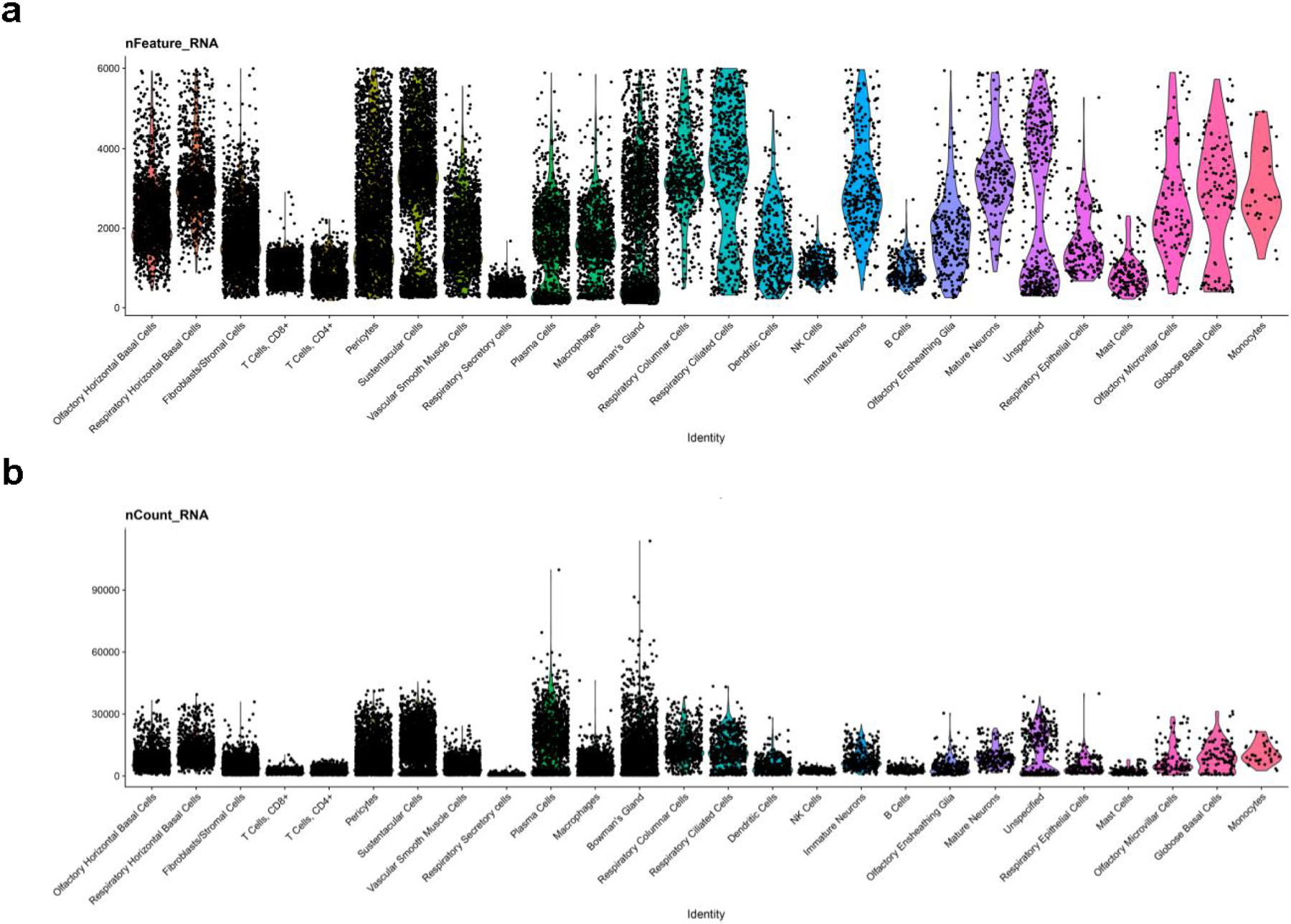

Extended Data Fig. 9. scRNA-seq quality control plots.

a, number of genes (features) per cluster. The plot depicts clusters from 28,726 combined olfactory and respiratory mucosal cells, n=4 patients. b, number of UMIs (nCount) per cluster. Cluster cell type identities are listed along the x-axis. Violin plot widths are proportional to the density of the distribution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients who generously contributed samples for this research. We acknowledge the assistance of the Oncogenomics Shared Resource at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the University of Miami Center for Computational Science. This work was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health grants DC013556 (B.J.G), DC016859 (B.J.G), CA125970 (J.W.H.), the Triological Society - American College of Surgeons (B.J.G.), the University of Miami Sheila and David Fuente Graduate Program in Cancer Biology (M.A.D.) the Center for Computational Science Fellowship (M.A.D.). The Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center also received funding from the National Cancer Institute Core Support grant P30 CA240139.

Footnotes

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, statements of code and data availability and accession codes are available at https://doi.org/.

Data availability

All sequencing data generated have been deposited in GEO under accession code GSE139522. Source data is provided for Fig. 2,3 and Extended Data Fig. 1,7.

Code availability

Code used for olfactory receptor analysis is available at https://github.com/harbourlab/OR_SC_analysis.

Accession codes

Gene expression omnibus: GSE139522.

Competing Interests

J.W.H. is the inventor of intellectual property related to prognostic testing for uveal melanoma. He is a paid consultant for Castle Biosciences, licensee of this intellectual property, and he receives royalties from its commercialization. No other authors declare a potential competing interest.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/.

References

- 1.Hinds JW, Hinds PL & McNelly NA Anat Rec 210, 375–383, doi: 10.1002/ar.1092100213 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwob JE, Szumowski KE & Stasky AA J Neurosci 12, 3896–3919 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung CT, Coulombe PA & Reed RR Nat Neurosci 10, 720–726, doi: 10.1038/nn1882 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein BJ et al. J Comp Neurol 523, 15–31, doi: 10.1002/cne.23653 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher RB et al. Cell Stem Cell 20, 817–830 e818, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.04.003 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brann JH & Firestein SJ Front Neurosci 8, 182, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00182 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn CG et al. J Comp Neurol 483, 154–163, doi: 10.1002/cne.20424 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holbrook EH, Wu E, Curry WT, Lin DT & Schwob JE Laryngoscope 121, 1687–1701, doi: 10.1002/lary.21856 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graziadei PP, Karlan MS, Graziadei GA & Bernstein JJ Brain Res 186, 289–300 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becht E et al. Nat Biotechnol, doi: 10.1038/nbt.4314 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Der Maaten LH, Mach GJ. Learn. Res 9 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corada M et al. Nat Commun 4, 2609, doi: 10.1038/ncomms3609 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen M, Reed RR & Lane AP Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 8089–8094, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620664114 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwob JE, Youngentob SL & Mezza RC J Comp Neurol 359, 15–37, doi: 10.1002/cne.903590103 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monahan K, Horta A & Lomvardas S Nature 565, 448–453, doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0845-0 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirota J & Mombaerts P Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 8751–8755, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400940101 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallrabenstein I et al. Neuroimage 113, 365–373, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.03.029 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyons DB et al. Cell 154, 325–336, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.039 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buck L & Axel R Cell 65, 175–187 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chess A, Simon I, Cedar H & Axel R Cell 78, 823–834 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuart T et al. Comprehensive integration of single cell data. bioRxiv (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E & Satija R Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat Biotechnol 36, 411–420, doi: 10.1038/nbt.4096 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McInnes L, Healy J, Saul N & Grossberger L UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection. The Journal of Open Source Software 3, 861 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blondel VD, Guillaume J-L, Lambiotte R & Lefebvre E Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2008, P10008, doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/p10008 (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuleshov MV et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res 44, W90–97, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu Z, Eils R & Schlesner M Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32, 2847–2849, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw313 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sergushichev A An algorithm for fast preranked gene set enrichment analysis using cumulative statistic calculation. bioRxiv, doi: 10.1101/060012 (2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ligtenberg W reactome.db: A set of annotation maps for reactome. R package version 1.68.0. (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fabregat A et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res 46, D649–D655, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1132 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein BJ et al. Contribution of Polycomb group proteins to olfactory basal stem cell self-renewal in a novel c-KIT+ culture model and in vivo. Development 143, 4394–4404, doi: 10.1242/dev.142653 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.