Abstract

In patients presenting for an evaluation of pregnancy in the first trimester, transvaginal ultrasound is the modality of choice for establishing the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy; evaluating pregnancy viability, gestational age, and multiplicity; detecting pregnancy-related complications; and diagnosing ectopic pregnancy. In this pictorial review article, the sonographic appearance of a normal intrauterine gestation and the most common complications of pregnancy in the first trimester in the acute setting are discussed.

Keywords: Transvaginal ultrasound, Viability, Ectopic pregnancy, Abortion, Abnormal gestation

Introduction

The first trimester of pregnancy consists of the first 12-13 weeks, calculated as beginning on the first date of the last menstrual period (LMP). During the first trimester, transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is the imaging modality of choice for both diagnosis and imaging follow-up. The advantages of ultrasound imaging include its widespread availability, relatively low cost, and the acquisition of real-time, high-resolution images. The initial diagnosis of pregnancy is usually made by identifying the presence of serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG). Ultrasound is then utilized during the first and second trimesters to establish the gestational age of the pregnancy and eventually to evaluate fetal anatomy. In the first trimester, pelvic ultrasound is employed to establish the presence or absence of an intrauterine gestational sac and to evaluate the viability of the pregnancy. In addition, it can be used to evaluate ectopic pregnancy and other pregnancy-related complications. Practice parameters for the performance and recording of obstetric ultrasound images have been described by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine [1].

Timeline of First-Trimester Sonographic Findings

Gestational Sac

Conventionally, gestational age is initially calculated from the first day of the LMP. Ovulation typically occurs mid-cycle, at about day 14 of the menstrual cycle, at which point fertilization (conception) is most likely to occur. Thus, by the time of the first missed menstrual period, fertilization and implantation of the fertilized ovum have occurred. During the first 3 weeks following conception, the developing gestational sac is below the limit of detection by TVUS [2]. The growth rate of the gestational sac is approximately 1.1 mm/day and the gestational sac first becomes apparent on TVUS at approximately 4.5-5 weeks of gestational age, appearing as a round anechoic structure located eccentrically within the echogenic decidua (Table 1, Fig. 1A, B) [3].

Table 1.

Timeline of normal fetal development

| Time (wk) | Development milestone |

|---|---|

| 4.5-5 | Appearance of gestational sac |

| 5-5.5 | Yolk sac becomes apparent |

| 6 | Embryo is seen, cardiac pulsation |

| 6.7-7 | Amniotic membrane appears |

| 7-8 | Appearance of fetal spine |

| 8 | Head and limbs begin to appear as distinct from torso |

| 8-8.5 | Fetal motion is appreciable |

| 8-10 | Rhombencephalon appears |

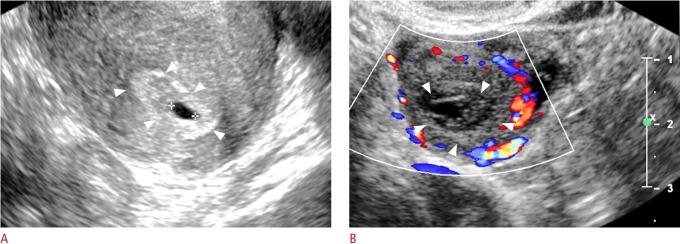

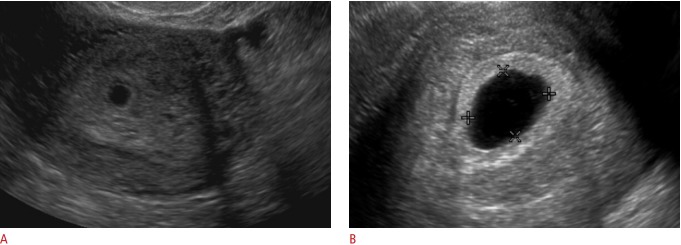

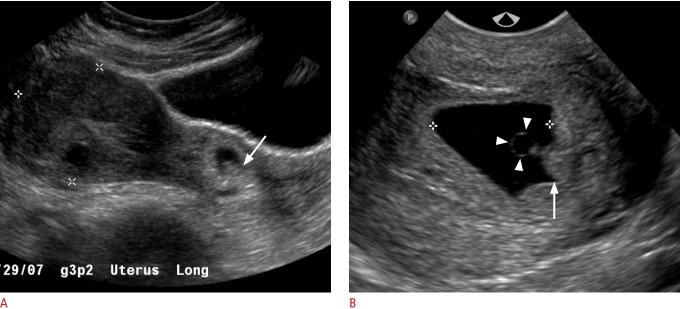

Fig. 1. Normal early gestational sac and corpus luteum.

A. Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) demonstrates an anechoic structure with peripheral echogenic tissue (arrowheads) representing a gestational sac in the uterine cavity of a woman with a positive urine pregnancy test. B. TVUS shows a circumscribed heterogenous structure with peripheral vascularity in the right ovary compatible with a corpus luteum (arrowheads).

Double Decidual Sac Sign

Subsequent to the appearance of the gestation sac, two concentric echogenic rings encircling the central anechoic collection develop: the outer ring represents the decidua parietalis, while the inner ring represents the decidua capsularis and chorion (Fig. 2A, B). This is known as the double decidual sac sign (DDS), which is a definitive sign of an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP). While the presence of the DDS sign confirms an IUP, its absence does not exclude an IUP [4]. Furthermore, the DDS sign can be difficult to demonstrate sonographically. For this reason, the possibility of a gestational sac should be considered for any round or ovoid fluid collection within the endometrium (Fig. 3A, B) [4]. Gestational sac size is measured in 3 dimensions and the mean sac diameter (MSD) is used to help estimate the early gestational age.

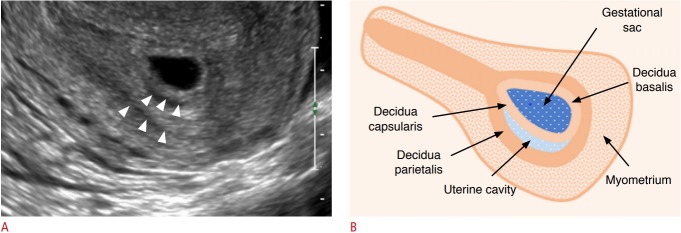

Fig. 2. The double decidual sac sign.

A. Transvaginal ultrasonography demonstrates two concentric echogenic rings (arrowheads) with intervening trace hypoechoic material, known as the double decidual sac sign. B. Graphical representation of the double decidual sign is shown.

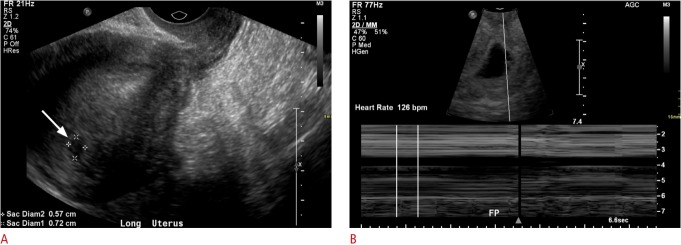

Fig. 3. A 19-year-old woman with vaginal bleeding and a positive beta-human chorionic gonadotropin test.

A. Initial transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) shows a vague hypoechoic collection measuring 7 mm in the uterine fundus (arrow). The morphology was not typical for an intrauterine pregnancy. B. Subsequent TVUS 2 weeks later demonstrates an intrauterine gestational sac with an embryo with heart rate of 126 bpm.

Yolk Sac

At around 5.5 weeks of gestation, the developing yolk sac becomes visible. Initially appearing as two echogenic parallel lines at the periphery of the gestational sac, the yolk sac eventually acquires its typical round appearance by the end of 5.5 weeks [2].

Embryo

The embryo (sometimes referred to as the fetal pole early on) becomes apparent at 6 weeks of gestation as a relatively featureless echogenic linear or oval structure adjacent to the yolk sac, initially measuring 1-2 mm in length. At this point, the MSD is approximately 10 mm. The crown-rump length (CRL) is the measurement between the cranial and caudal ends of the embryo and is the most accurate measure of the gestational age in the first trimester. The CRL gradually increases, measuring 10 mm at 7.0 weeks. The lack of a visible embryo on TVUS once the MSD reaches at least 25 mm is diagnostic of pregnancy failure (Fig. 4) [2,5]. While the fetal pole begins as a featureless structure, some fetal anatomic structures become visible as the first-trimester progresses. The spine appears at 7-8 weeks, and the hindbrain (rhombencephalon) is evident at 8-10 weeks [6].

Fig. 4. Transvaginal ultrasonography in a pregnant woman presenting with abdominal pain and cramping.

A. Initial ultrasonography shows a gestational sac without a yolk sac or embryo. B. Follow-up ultrasonography 2 weeks later shows a gestational sac measuring greater than 25 mm in diameter without evidence of a yolk sac or embryo. These findings are diagnostic of early pregnancy loss.

Amniotic Membrane

The amniotic membrane becomes visible around 7 weeks, and the CRL closely corresponds to the amniotic sac diameter between 6.5 and 10 weeks of gestation (Fig. 5) [7]. After fetal urine production commences at about 10 weeks, there is a disproportionate enlargement of the amniotic sac relative to the chorionic cavity. The amnion and chorion fuse after the first trimester at 14-16 weeks [8].

Fig. 5. Transvaginal ultrasonography in a patient with a previously confirmed intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) and vaginal bleeding, showing an IUP with a fetal pole (arrowheads).

A curvilinear echogenic membrane is noted around the embryo, corresponding to the amniotic membrane (arrow).

Cardiac Activity

Cardiac activity is seen as early as the sixth week of gestation, when the embryo is 1-2 mm in size. The current guidelines of the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound (SRU) establish a CRL cutoff of 7 mm, above which one should definitively visualize fetal cardiac activity. The absence of a detectable heartbeat once the embryo measures greater than 7 mm in length is diagnostic of pregnancy failure (Fig. 6A, B) [7]. The fetal heart rate gradually increases with gestational age from approximately 110 beats per minute (bpm) at 6.2 weeks to approximately 159 bpm at 7.6-8.0 weeks (Fig. 7A-E) [9]. Slow embryonic heart rates are associated with a worse shortterm prognosis, with fetal heart rates less than 100 bpm before 6.3 weeks or below 120 bpm at 6.3-7.0 weeks linked to an increased rate of embryonic demise [9,10]. The overall prognosis improves with increasing heart rate [10].

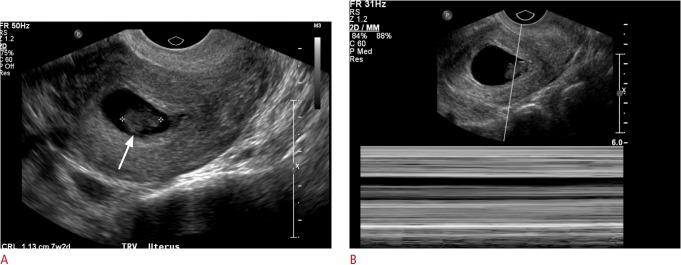

Fig. 6. Early pregnancy failure.

A. Transvaginal ultrasonography shows an intrauterine pregnancy with an embryo (arrow) with a crown-rump length of 1.1 cm, corresponding to a gestational age of 7 weeks, 2 days. B. No fetal heart rate was identified, compatible with intrauterine embryonic demise.

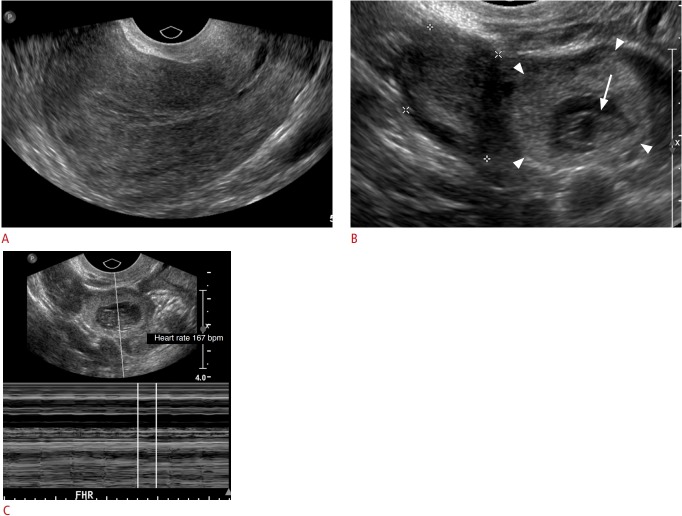

Fig. 7. Transvaginal ultrasonography in a pregnant woman presenting with abdominal pain, cramping, and vaginal bleeding.

A-E. M-mode images show progressive increase in heart rate with advancing gestational age. A. Intrauterine gestation with an embryo and yolk sac (crown-rump length of 7 mm --> gestational age [GA] of 6 weeks and 5 days) is shown. B. Fetal heart rate is 127 bpm. C. The cervix is closed. D. Two days later, pelvic ultrasonography demonstrates interval growth of the embryo, with a crown-rump length of 1 cm, corresponding to a GA of 7 weeks. E. The heart rate increases progressively with advancing gestational age.

First-Trimester Abnormalities

First-trimester TVUS is routinely performed in patients presenting with pelvic/abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding. Once pregnancy is established with urine or serum β-hCG tests, the utility of TVUS for evaluation of these patients is multifactorial: (1) to determine the presence and multiplicity of an IUP, (2) to determine the viability of an IUP, (3) to determine the stage of spontaneous abortion in the case of a nonviable pregnancy, and (4) to identify probable reasons why an IUP is not identified on TVUS.

Confirming an IUP

The detection of an eccentrically-located, anechoic collection in the endometrium of a patient with elevated serum β-hCG levels represents an IUP in 99.5% of cases [4]. The presence of two or more gestational sacs surrounded by thick echogenic chorion, or sonographic features of the inter-twin membrane and "twin-peak" sign, confirm a multiple-gestation pregnancy [11].

Evaluating Viability

Once an IUP is identified, the viability and presence or absence of abnormal features must be evaluated. The timeline of visualization of the gestational sac, yolk sac, and embryo at 5, 5.5, and 6 weeks, respectively, are accurate and consistent [5]. Deviations from the normal chronological appearance of these structures are highly suspicious for pregnancy failure. The SRU has presented specific guidelines for diagnosing pregnancy failure based on certain characteristics: namely, (1) the CRL measurement by which an embryonic heart rate must be identified (7 mm), (2) the MSD by which an embryo should be identified (25 mm), and (3) the absence of an embryo in two consecutive ultrasound exams separated by a fixed time interval. In addition, other findings including the empty amnion sign, a yolk sac greater than 7 mm, and a disproportionately small gestational sac are highly suspicious for pregnancy failure (Fig. 8). Through these guidelines, the SRU aims to achieve 100% specificity for defining pregnancy failure and to sustain a primum non nocere approach given the calamitous outcome of a potentially normal pregnancy following treatment for an incorrectly diagnosed pregnancy failure (Table 2) [4,5].

Fig. 8. Early pregnancy with findings suspicious for pregnancy failure.

Transabdominal ultrasonography in a 34-year-old woman with a positive beta-human chorionic gonadotropin test and vaginal bleeding demonstrates an intrauterine gestation with a mean sac diameter of 23 mm and a yolk sac diameter of 19 mm. No definite fetal pole was identified. Instead, an amorphous embryonic structure (arrowheads) was identified. These findings are suspicious for, but not diagnostic of pregnancy failure.

Table 2.

Findings diagnostic of and suspicious for pregnancy failure

| Finding | Diagnostic of pregnancy failure | Suspicious for pregnancy failure |

|---|---|---|

| Absent fetal cardiac activity by the time CRL is a certain size | CRL ≥7 mm | CRL <7 mm |

| Absent embryo by the time the gestational sac is a certain size | MSD ≥25 mm | MSD 16-24 mm |

| Absent embryo in two consecutive exams separated by time | Nonvisualization of an embryo with fetal heart rate 2 wk after identification of gestational sac without yolk sac | Nonvisualization of an embryo with fetal heart rate 7-10 days after US showed gestational sac with yolk sac |

| Nonvisualization of an embryo with fetal heart rate 11 or more days after identification of a gestational sac with yolk sac | Nonvisualization of embryo 6 wk after LMP | |

| Abnormal morphology of the gestational sac, amnion, and yolk sac | - | Amnion seen adjacent to yolk sac with no visible embryo (empty amnion) |

| - | Yolk sac >7 mm | |

| - | Disproportionately small gestational sac (in relation to size of embryo, <5 mm difference in size between MSD and CRL) |

CRL, crown-rump length; MSD, mean sac diameter; US, ultrasonography; LMP, last menstrual period.

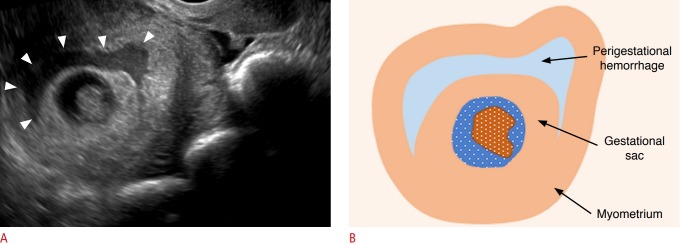

Subchorionic Hematoma

Subchorionic hematoma (SCH) is a relatively common finding in the first trimester and has been reported to occur in 18%-22% of IUPs in patients presenting with vaginal bleeding [12,13]. On TVUS, SCH appears as a crescent-shaped, heterogeneous avascular collection between the gestational sac and decidua basalis (Fig. 9A, B). Larger subchorionic hematomas are associated with an increased risk of pregnancy loss, especially if the hematoma is greater than twothirds of the chorionic circumference [13,14].

Fig. 9. Subchorionic hemorrhage.

A. Transvaginal ultrasonography in a pregnant woman shows a gestational sac with an embryo and a heterogeneous subchorionic collection (arrowheads) encircling approximately 180° of the gestational sac. B. Graphic depiction of the findings in A is shown.

Spontaneous Abortion

Spontaneous abortion or miscarriage is clinically defined as the loss of a pregnancy before the 20th week of gestation or the expulsion of a fetus weighing less than 500 g [15,16]. There are various stages of spontaneous abortion. A threatened abortion refers to a clinical scenario in which a patient presents with vaginal spotting/bleeding and cramping/contractions with a closed cervical os. The pregnancy itself may appear normal or may demonstrate abnormal features. Poor prognostic indicators include abnormal morphology (e.g., a small or irregular gestational sac), fetal bradycardia, or a large SCH [9,12]. An inevitable abortion involves a similar clinical situation with vaginal bleeding and abdominal cramping, but with an open cervical os on TVUS (Fig. 10A-C). The products of conception may be normally or abnormally positioned within the uterus or may protrude into the cervix. An incomplete abortion is the term used when the retained products of conception remain within the uterus after passage of the pregnancy. This often appears as a heterogeneous collection or mass within the uterus. While it may be avascular, the presence of blood flow enables the diagnosis of retained products. A completed abortion is the cessation of vaginal bleeding following the passage of the pregnancy without retained products of conception (Fig. 11A-D). Lastly, a missed abortion is a nonviable pregnancy with a closed cervix and no clinical symptoms of miscarriage [17].

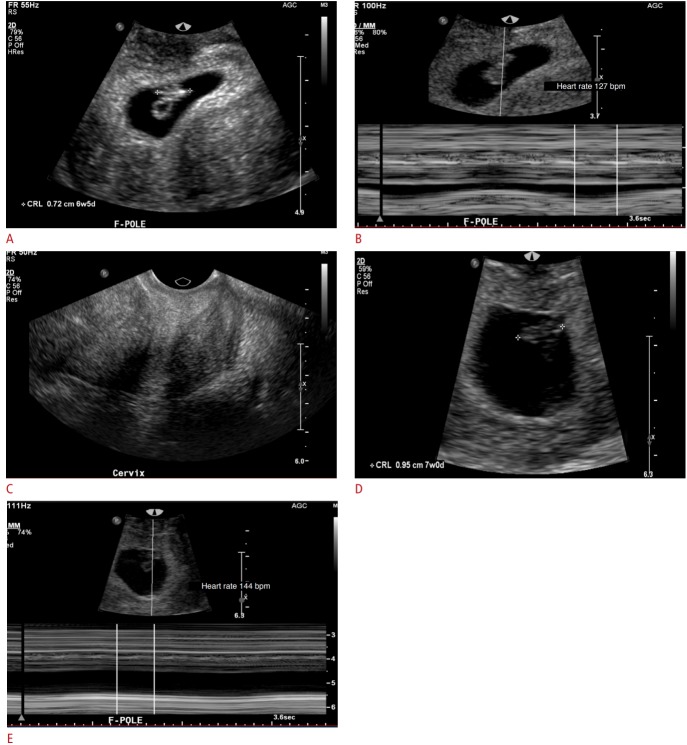

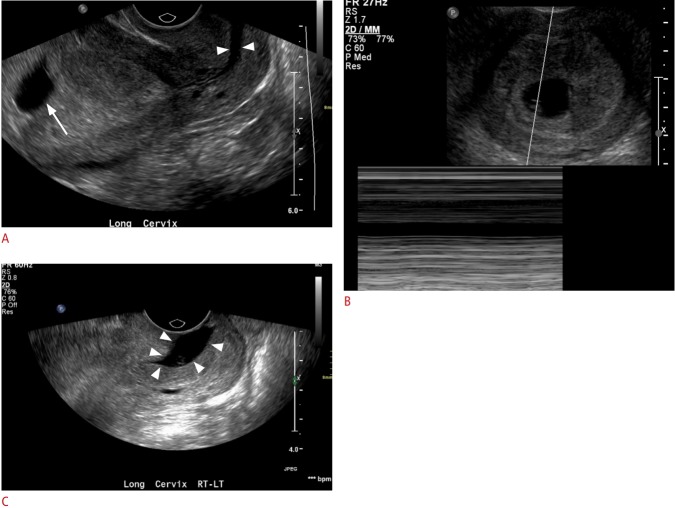

Fig. 10. Inevitable abortion: transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) in a 41-year-old woman with a known intrauterine pregnancy presenting with abdominal pain and vaginal spotting.

A. Initial TVUS shows an intrauterine gestation (arrow), with an open cervix (arrowheads). B. No heart rate was identified. C. Followup ultrasonography obtained the next day shows the gestational sac in the cervical canal (arrowheads), compatible with inevitable abortion.

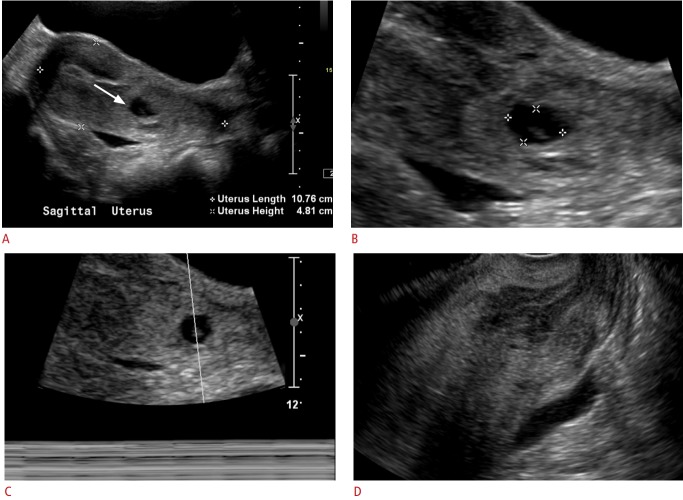

Fig. 11. Completed abortion: transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasonography obtained in a patient with a confirmed intrauterine gestation.

A, B. Gestational sac containing a fetal pole was identified in the cervix (arrow); the abortion was in progress. C. No fetal heart rate was identified. D. The patient passed a few clots and transvaginal images were obtained. The previously seen gestational sac in the cervix was no longer seen, compatible with a completed abortion.

Pregnancy of Unknown Location and Ectopic Pregnancy

In a substantial number of patients evaluated in the emergency department during very early pregnancy, the location of the gestational sac is inconclusive. The significance of a nonvisualized gestational sac on TVUS in a patient with a positive pregnancy test could reflect one of three scenarios: (1) less than 5 weeks of gestation, (2) ectopic pregnancy, or (3) a completed abortion [18].

It is incumbent for the technologist/radiologist to carefully scrutinize the adnexa and other spaces in the pelvis for any masses, collections, or obvious products of conception in order to rule out an ectopic pregnancy. As the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy is 1.4% and it accounts for 25% of all maternal deaths, practitioners should have a high degree of suspicion for this diagnosis. Although the vast majority of ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tubes, implantation of pregnancies at other sites can also take place, including the cervix, cesarean scars, uterine cornua, and other nongynecological sites in the abdomen and pelvis (Figs. 12-14) [2]. In cases in which no IUP is identified and there is no sonographic evidence of an ectopic pregnancy, serial monitoring of β-hCG levels and short-term repeat TVUS are generally recommended for follow-up.

Fig. 12. Adnexal ectopic pregnancy: transvaginal ultrasonography in a woman with a positive beta-human chorionic gonadotropin test.

A. No intrauterine gestational sac was identified. The right ovary and adnexa were normal. B. A left adnexal heterogenous vascular mass (arrowheads), was suspicious for an adnexal ectopic pregnancy, which was confirmed intraoperatively.

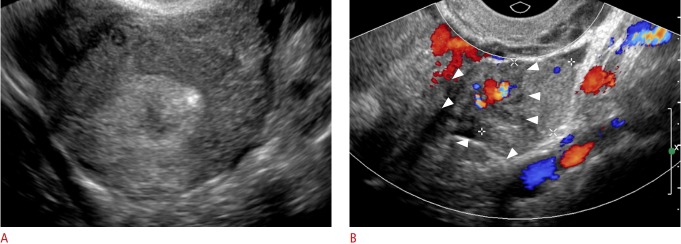

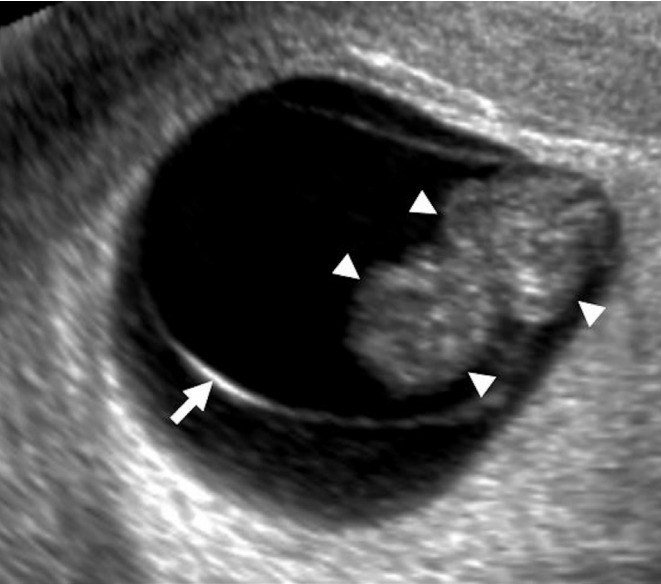

Fig. 13. Adnexal ectopic pregnancy: transvaginal images in a woman with vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, and a positive beta-human chorionic gonadotropin test.

A. No intrauterine gestational sac was identified. The left ovary and adnexa were normal. B, C. Sonograms demonstrate a right adnexal mass containing a gestational sac (arrowheads) and a fetal pole (arrow), with a heart rate of 167 bpm, compatible with a right adnexal ectopic gestation.

Fig. 14. Cervical ectopic pregnancy.

A. Transabdominal ultrasonography in a woman with a positive beta-human chorionic gonadotropin test, shows a gestational sac containing a fetal pole in the cervix (arrow). B. Transvaginal ultrasonography shows a gestational sac containing a yolk sac (arrowheads) and fetal pole (arrow).

Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

Gestational trophoblastic disease is a broad term which encompasses both benign entities, such as partial and complete mole, gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN), and malignant diagnoses, such as invasive mole, choriocarcinoma, and epithelioid and placental site trophoblastic tumors. As a result of dispermic fertilization of an ovum, pregnant patients will often present with vaginal bleeding. On TVUS in the first trimester, the endometrial cavity will contain an echogenic solid mass, usually with numerous cystic spaces, which are the hydropic villi and trophoblastic hyperplasia (Fig. 15). Careful scrutiny of the mass is important to distinguish between complete mole (no fetal parts), partial mole (some fetal parts), and GTN (myometrial invasion) [19].

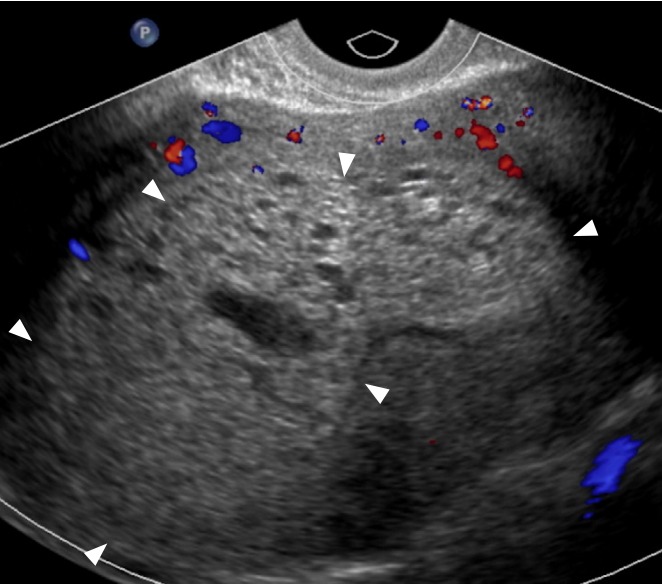

Fig. 15. Gestational trophoblastic disease: complete mole.

Transvaginal ultrasonography in a 35-year-old woman presenting with an elevated serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β -hCG) level (>383,000 mIU/mL) and vaginal bleeding, shows an echogenic, heterogenous mass with minimal peripheral vascularity (arrowheads) and numerous cystic spaces. No fetal parts or myometrial invasion was identified. These findings, given the significantly elevated β-hCG value, were diagnostic of complete mole.

Conclusion

The diagnostic possibilities for pregnant patients presenting with pain and bleeding are broad. TVUS is paramount in its utility as a diagnostic tool for these patients. When used in combination with clinical information and serum β-hCG levels, it can provide diagnostic and prognostic information to clinicians regarding pregnancy confirmation and viability, as well as rapid information regarding life-threatening conditions such as ectopic pregnancy.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Kim YH. Data acquisition: Murugan VA, Murphy BO. Data analysis or interpretation: Murugan VA, Murphy BO. Drafting of manuscript: Murugan VA, Murphy BO. Critical revision of manuscript: Dupuis C, Goldstein A, Kim YH. Approval of the final version of the manuscript: all authors.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.AIUM-ACR-ACOG-SMFM-SRU practice parameter for the performance of standard diagnostic obstetric ultrasound examinations. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37:E13–E24. doi: 10.1002/jum.14831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doubilet PM. Ultrasound evaluation of the first trimester. Radiol Clin North Am. 2014;52:1191–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyberg DA, Mack LA, Laing FC, Patten RM. Distinguishing normal from abnormal gestational sac growth in early pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 1987;6:23–27. doi: 10.7863/jum.1987.6.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doubilet PM, Benson CB. First, do no harm... To early pregnancies. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:685–689. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, Blaivas M, Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Multispecialty Panel on Early First Trimester Diagnosis of Miscarriage and Exclusion of a Viable Intrauterine Pregnancy. Barnhart KT, et al. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1443–1451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1302417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cyr DR, Mack LA, Nyberg DA, Shepard TH, Shuman WP. Fetal rhombencephalon: normal US findings. Radiology. 1988;166:691–692. doi: 10.1148/radiology.166.3.3277241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horrow MM. Enlarged amniotic cavity: a new sonographic sign of early embryonic death. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:359–362. doi: 10.2214/ajr.158.2.1729798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeh HC, Rabinowitz JG. Amniotic sac development: ultrasound features of early pregnancy: the double bleb sign. Radiology. 1988;166(1 Pt 1):97–103. doi: 10.1148/radiology.166.1.3275972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doubilet PM, Benson CB. Embryonic heart rate in the early first trimester: what rate is normal? J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14:431–434. doi: 10.7863/jum.1995.14.6.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Chow JS. Outcome of pregnancies with rapid embryonic heart rates in the early first trimester. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:67–69. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.1.1750067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trop I. The twin peak sign. Radiology. 2001;220:68–69. doi: 10.1148/radiology.220.1.r01jl1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuuli MG, Norman SM, Odibo AO, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Perinatal outcomes in women with subchorionic hematoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1205–1212. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821568de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodgers SK, Chang C, DeBardeleben JT, Horrow MM. Normal and abnormal US findings in early first-trimester pregnancy: review of the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2012 Consensus Panel recommendations. Radiographics. 2015;35:2135–2148. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015150092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett GL, Bromley B, Lieberman E, Benacerraf BR. Subchorionic hemorrhage in first-trimester pregnancies: prediction of pregnancy outcome with sonography. Radiology. 1996;200:803–806. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.3.8756935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tulandi T, Al-Fozan HM. Spontaneous abortion: risk factors, etiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnostic evaluation. In: Rose B, editor. UpToDate. Wellesley, MA: UpToDate; 2017. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendriks E, MacNaughton H, MacKenzie MC. First trimester bleeding: evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:166–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeqiri F, Pacarada M, Kongjeli N, Zeqiri V, Kongjeli G. Missed abortion and application of misoprostol. Med Arh. 2010;64:151–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Condous G, Timmerman D, Goldstein S, Valentin L, Jurkovic D, Bourne T. Pregnancies of unknown location: consensus statement. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;28:121–122. doi: 10.1002/uog.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaaban AM, Rezvani M, Haroun RR, Kennedy AM, Elsayes KM, Olpin JD, et al. Gestational trophoblastic disease: clinical and imaging features. Radiographics. 2017;37:681–700. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]