Abstract

Antibiotics have been described to modulate bacterial virulence gene expression. This study aimed to assess the changes caused by anti-Staphylococcus agents in the transcription of leucocidin ED (lukED) gene of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman in vitro and in vivo and to determine whether the altered expression is agr dependent. The bacteria were exposed to subinhibitory concentrations [1/2, 1/4, or 1/8 minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC)] of 11 antibiotics, and the expression of lukE and agr-effector RNAIII was determined using qRT-PCR. In vivo experiments were performed to evaluate the impact exerted by six representative antibiotics on the transcription of both genes. Molecular analysis showed that in vitro lukE transcription was dramatically promoted in the Newman strain exposed to sub-MICs of vancomycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, gentamicin, daptomycin, and ciprofloxacin and considerably reduced when stimulated by cefazolin, erythromycin, rifampicin, tigecycline, and linezolid. In the murine abscess model, tigecycline significantly decreased the transcription of lukE and the bacterial numbers, whereas vancomycin increased them; although cefazolin increased the lukE expression (contrary to the in vitro effect), it had a remarkable role in reducing bacterial load. The correspondence analysis shows that RNAIII expression varied under seven of 11 antibiotics in vitro, and six drugs in vivo were consistent with lukE transcripts. In conclusion, our data show that anti-Staphylococcus antibiotics exert modulatory effects on lukE expression in vitro and/or in vivo, and the changed expression caused by some drugs may be involved with agr activity, thus providing a guide to choose appropriate agents to avoid promoting bacterial virulence in lukED-positive S. aureus infections.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, leucocidin ED, RNAIII, antibiotic exposure, transcription

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a pathogen notorious for its ability to cause many infection-related illnesses ranging from cutaneous infections and food poisoning to toxic shock syndrome, septicemia, and necrotizing pneumonia (Tong et al., 2015). The success of S. aureus infection stems from a repertoire of virulence factors that enable the bacteria to escape from the host immune system (Otto, 2014). Among these factors, leucocidin ED (LukED), a bicomponent pore-forming toxin, plays an important role in S. aureus pathogenicity (Alonzo and Torres, 2014; Balasubramanian et al., 2016).

LukED targets the membrane of various cells such as neutrophils, T cells, myeloid cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and erythrocytes and elicits β-barrel pores that span the lipid bilayer and lead to osmotic lysis of the host cell (Alonzo et al., 2012, 2013; Reyes-Robles et al., 2013; Spaan et al., 2015). Epidemiological data and animal infection models show that lukED can be commonly detected in clinical S. aureus strains (approximately 2/3 to 4/5 of isolates) and is closely associated with impetigo, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, and bloodstream infection, among others (Gravet et al., 1998; Arciola et al., 2007; Alonzo et al., 2012; Alonzo and Torres, 2014; He et al., 2018). The accessory gene regulator (Agr)-repressor of toxin (Rot) pathway is an important modulatory network of LukED production (Alonzo et al., 2012). The agr operon encodes the regulatory RNA RNAIII, which promotes the transcription of leucocidin genes by negatively controlling the yield of Rot (Benson et al., 2014; Killikelly et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2018).

During treatment, bacteria may be exposed to subinhibitory levels [sub-minimal inhibitory concentrations (sub-MICs)] of antibiotics owing to drug-resistant organisms or the pharmacokinetics of antimicrobial agents (such as short half-life, poor drug distribution and adherence, or interactions between antibiotics) (Cars, 1990; Hodille et al., 2017). Early investigations have shown that sub-MICs of antibiotics may initiate differential expression of virulence genes in S. aureus, which may affect the pathogenesis of infection and result in worse outcomes (Dumitrescu et al., 2007, 2008, 2011; Stevens et al., 2007; Pichereau et al., 2012; Diep et al., 2013; Otto et al., 2013; Yamaki et al., 2013; Rudkin et al., 2014; Turner and Sriskandan, 2015; Hodille et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018). Therefore, the therapeutic efficacy of antibiotics might also rely on their capacity to prevent the production of virulence factors (Otto et al., 2013). The use of antibiotics that reduce the Panton–Valentine leucocidin (PVL) toxin production is recommended for the treatment of severe infections caused by pvl-positive S. aureus (HPA, 2008; Nathwani et al., 2008). Nevertheless, little is known about the influence of antibiotics on lukED expression.

In this study, we selected common anti-Staphylococcus drugs to evaluate their impact on the expression of lukED in the S. aureus strain Newman in vitro and in vivo. We also analyzed whether the production of RNAIII is associated with variations in the levels of lukED transcripts affected by antimicrobial compounds.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strain and Culture Conditions

Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman was cultured at 37°C in yeast extract-Casamino Acids-pyruvate (YCP) medium [3% (w/v) yeast extract (Oxoid), 2% (w/v) casamino acids (Amresco, Washington, DC, United States), 2% (w/v) sodium pyruvate (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), 0.25% (w/v) Na2HPO4, and 0.042% (w/v) KH2PO4, pH 7.0)], which is able to promote the highest expression of LukED (Alonzo and Torres, 2014).

Antibiotics

The antimicrobials utilized in this work were cefazolin, gentamicin, erythromycin, tigecycline, rifampicin, daptomycin (purchased from Dalian Meilun Biotech, Dalin, China), ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, vancomycin (from the National Institutes for Food and Drug Control, Beijing, China), linezolid (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, United States), and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO, United States).

Determination of Minimal Inhibitory Concentration

Minimal inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics against the S. aureus strain Newman were determined in triplicate by the standard microdilution broth method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations (Wayne, 2017).

Growth Kinetics

Overnight liquid cultures of strain Newman were diluted 1:100 into 25 ml of fresh YCP medium, followed by addition of 1/8 MIC, 1/4 MIC, or 1/2 MIC antibiotics. Cultures without antibiotic served as control. Cultures were grown at 37°C with shaking at 150 r/min. Cell growth was detected by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm every hour using a UV-2102C ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Unico Instruments, Shanghai, China).

In vitro Exposure to Antibacterial Agents

Bacterial culture aliquots for RNA extraction were collected after the early (3 h) and late (5 h) logarithmic growth phases, when transcription of lukED was rising and reached the highest level, respectively (Yang et al., 2019).

Extraction of Bacterial RNA

Bacterial culture samples were centrifuged at 13,000 × g and 4°C for 10 min; resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM of Tris HCl and 1 mM of EDTA, pH 8.0) with lysostaphin (1 mg/ml, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) and proteinase K (20 mg/ml, TaKaRa, Dalian, China); and incubated at 56°C for 1 h for cell wall lysis. Total RNA was extracted using the MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Subcutaneous Abscess in Mice

Female Balb/c nude (nu/nu) mice between 4 and 6 weeks old were prepared for the abscess model. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and then injected subcutaneously with 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 3 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml of fresh Newman strain to form the abscess (Turner and Sriskandan, 2015).

In vivo Exposure to Antimicrobials

After 48 h of infection, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 150 μl of 10 mg/kg of clindamycin, 10 mg/kg of linezolid, 25 mg/kg of cefazolin, 30 mg/kg of vancomycin, 4 mg/kg of daptomycin, 1.6 mg/kg of tigecycline, or PBS as a control according to the human therapeutic doses recommended by the Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy (Gilbert, 2014).

Enumeration and RNA Extraction of Bacteria From Abscess

Following a previously described method (Turner and Sriskandan, 2015), mice were sacrificed after 8 h of treatment, and the abscess tissue was cut. Samples were diluted in PBS and plated for bacteria counting. The remaining abscesses were placed into liquid nitrogen quickly, followed by grinding for extraction of RNA as described above.

Relative Quantitative RT-PCR

Bacterial RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), followed by purification and reverse transcription (1 μg of RNA) using the PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Gene transcript levels were determined by quantitative real-time amplification (qRT-PCR, SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM, TaKaRa, Dalian, China) in a 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA, United States). Primers for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 1 (Balasubramanian et al., 2016; Gaupp et al., 2016). The mRNA levels of target genes were standardized against those of the housekeeping gene 16S rRNA. The fold change was determined using the 2–ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | References |

| lukE-F | GAAATGGGGCGTTACTCAAA | Balasubramanian et al., 2016 |

| lukE-R | GAATGGCCAAATCATTCGTT | Balasubramanian et al., 2016 |

| RNAIII-F | AGGAGTGATTTCAATGGCACAAG | Gaupp et al., 2016 |

| RNAIII-R | TGTGTCGATAATCCATTTTACTAAGTCA | Gaupp et al., 2016 |

| 16S rRNA-F | CGTGCTACAATGGACAATACAAA | Gaupp et al., 2016 |

| 16S rRNA-R | ATCTACGATTACTAGCGATTCCA | Gaupp et al., 2016 |

Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a posteriori Dunnett’s test was used to analyze the results (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). Results were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Antibiotics

The MIC values of 11 antibiotics, summarized in Table 2, showed that the S. aureus strain Newman was susceptible to all the drugs tested.

TABLE 2.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 11 antibiotics for Staphylococcus aureus Newman.

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) |

| Cefazolin (CFZ) | 0.25 |

| Gentamicin (GEN) | 0.5 |

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | 0.5 |

| Erythromycin (ERY) | 0.5 |

| Tigecycline (TGC) | 0.25 |

| Clindamycin (CLI) | 0.125 |

| Vancomycin (VAN) | 2 |

| Linezolid (LZD) | 2 |

| Rifampicin (RIF) | 0.03 |

| Daptomycin (DAP) | 0.5 |

| Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (SXT) | 1 |

Impacts of Sub-Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Antibiotics on Staphylococcus aureus Growth

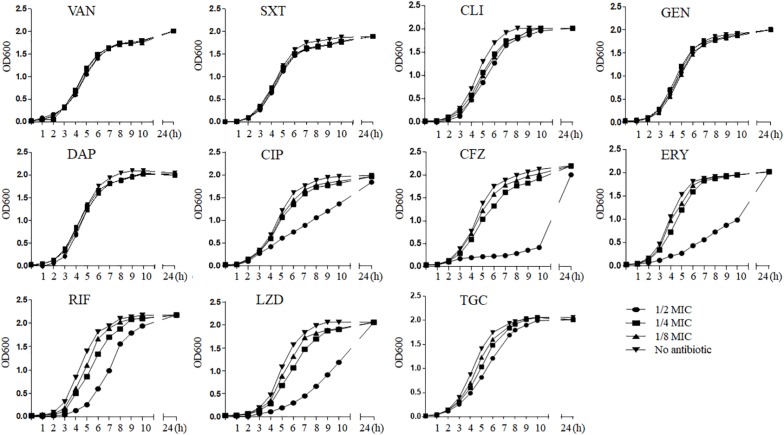

We generalized the impact of 11 antibiotics at sub-MICs on strain Newman growth (Figure 1). As can be seen, graded concentrations of vancomycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, gentamicin, daptomycin, and tigecycline triggered no significant growth defects over the entire growth curves compared with those of the control without drugs; in contrast, ciprofloxacin, cefazolin, erythromycin, rifampicin, and linezolid caused growth inhibition (p < 0.05) at 1/2 MIC. Because of this inhibition, we excluded these five antibiotics at 1/2 MIC from subsequent experiments of in vitro measurement of transcription to eliminate possible effects from antibiotic-induced growth impairment.

FIGURE 1.

The influence of sub-MICs antibiotics on Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman kinetic growth. VAN, vancomycin; SXT, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole; CLI, clindamycin; GEN, gentamicin; DAP, daptomycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CFZ, cefazolin; ERY, erythromycin; RIF, rifampicin; LZD, linezolid; TGC, tigecycline; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Impact of Antibiotics on lukE Expression

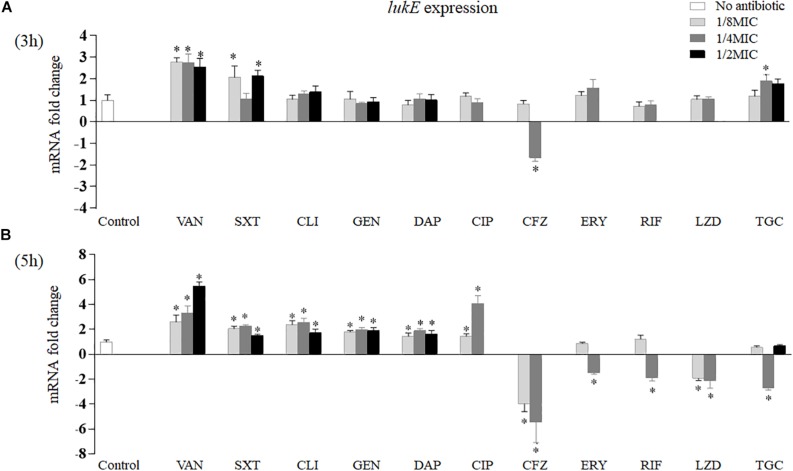

As exhibited in Figure 2, after 3 h of in vitro incubation, only four of 11 antibiotics had effects on lukE expression (Figure 2A). Vancomycin at three sub-MICs detected significantly increased lukE transcription from 2.54- to 2.77-fold, respectively (p = 0.002 at 1/8 MIC, p = 0.004 at 1/4 MIC, and p = 0.006 at 1/2 MIC). Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole induced lukE mRNA production at 1/8 MIC (2.07-fold, p = 0.026) and 1/2 MIC (2.12-fold, p = 0.031). Tigecycline at 1/4 MIC enhanced lukE transcription level 1.89-fold (p = 0.019). In contrast, cefazolin also dramatically reduced the expression of lukE (1.65-fold, p = 0.037) at 1/4 MIC.

FIGURE 2.

Impact of antibiotics at graded subinhibitory concentrations on the in vitro expression of lukE of Staphylococcus aureus Newman after 3 (A) and 5 h (B) of stimulation. Values are means ± SD (three technical replicates). ∗p < 0.05 compared with the no-antibiotic control. VAN, vancomycin; SXT, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole; CLI, clindamycin; GEN, gentamicin; DAP, daptomycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CFZ, cefazolin; ERY, erythromycin; RIF, rifampicin; LZD, linezolid; TGC, tigecycline.

However, after 5 h of in vitro exposure, the 11 antibiotics examined all affected lukE mRNA transcription (Figure 2B). Treatment with vancomycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, gentamicin, or daptomycin at all sub-MICs tested significantly increased lukE expression levels than did the no-drug control. Ciprofloxacin affected lukE mRNA levels particularly at 1/8 MIC and 1/4 MIC, ranging from 1.46- (p = 0.037) to 4.09-fold (p = 0.001), respectively. The transcript levels of lukE were considerably reduced in a concentration-dependent manner when exposed to 1/8 to 1/4 MICs of cefazolin (3.92-fold, p = 0.009 and 5.10-fold, p = 0.001, respectively). Strain Newman showed reduced lukE expression in the presence of 1/4 MIC of erythromycin (1.47-fold, p = 0.030) and rifampicin (1.88-fold, p = 0.010). Addition of 1/8 MIC (1.91-fold, p = 0.031) and 1/4 MIC (two-fold, p = 0.017) of linezolid and 1/4 MIC (2.71-fold, p = 0.003) of tigecycline led to reduced lukE transcript levels.

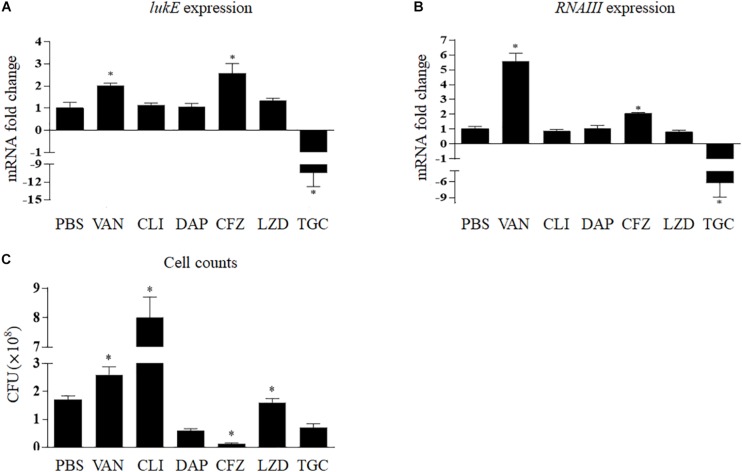

Figure 3A shows that clindamycin, linezolid, and daptomycin had no relevant effects on lukE mRNA transcription in vivo; however, the expression of lukE was strikingly inhibited by tigecycline (10.10-fold, p < 0.001) and increased by vancomycin (2.03-fold, p = 0.009) and cefazolin (2.57-fold, p = 0.006). In addition, bacterial count results show that the total abscess bacterial load was significantly reduced by tigecycline, daptomycin, and cefazolin but considerably increased by clindamycin and vancomycin (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Impact of antibiotics on the expression of lukE (A) and RNAIII (B) and cell counts (C) of Staphylococcus aureus Newman within the abscess. Values are means ± SD (three technical replicates). n = 5 mice per group. ∗p < 0.05, compared with the group treated with PBS. TGC, tigecycline; CLI, clindamycin; DAP, daptomycin; LZD, linezolid; VAN, vancomycin; CFZ, cefazolin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Impact of Antibiotics on RNAIII Expression

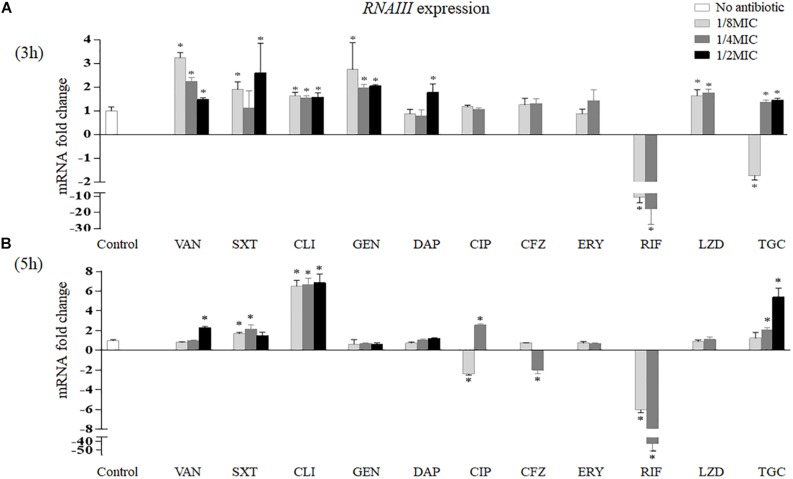

The effects of sub-MICs of antibiotics on RNAIII expression in vitro are shown in Figure 4. After 3 h of treatment, vancomycin induced RNAIII transcription at all sub-MICs tested (3.24-fold at 1/8 MIC, p < 0.001; 2.24-fold at 1/4 MIC, p = 0.001; and 1.47-fold at 1/2 MIC, p = 0.016). Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole increased RNAIII mRNA levels at 1/8 MIC (1.90-fold, p = 0.008) and 1/2 MIC (2.59-fold, p = 0.034). In addition, clindamycin and gentamicin all enhanced the expression of RNAIII at 1/8 MIC (1.65-fold, p = 0.008; 2.74-fold, p = 0.017), 1/4 MIC (1.55-fold, p = 0.010; 1.95-fold, p = 0.003), and 1/2 MIC (1.58-fold, p = 0.014; 2.04-fold, p = 0.002). Linezolid induced RNAIII expression by 1.63-fold at 1/8 MIC (p = 0.020) and 1.75-fold at 1/4 MIC (p = 0.006). RNAIII expression levels had a statistically significant increase at 1/2 MIC of daptomycin (1.77-fold, p = 0.018). Rifampicin reduced RNAIII expression by 9.90-fold at 1/8 MIC (p < 0.001) and 12.20-fold at 1/4 MIC (p = 0.004). Tigecycline reduced RNAIII expression by 1.72-fold at 1/8 MIC (p = 0.009) but enhanced its expression at 1/4 MIC (1.37-fold, p = 0.033) and 1/2 MIC (1.46-fold, p = 0.015) (Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Impact of antibiotics at sub-MICs on the in vitro expression of RNAIII of Staphylococcus aureus Newman after 3 (A) and 5 h (B) of treatment. Values are means ± SD (three technical replicates). ∗p < 0.05 compared with the no-antibiotic control. VAN, vancomycin; SXT, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole; CLI, clindamycin; GEN, gentamicin; DAP, daptomycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CFZ, cefazolin; ERY, erythromycin; RIF, rifampicin; LZD, linezolid; TGC, tigecycline; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

After 5 h of treatment, RNAIII expression levels increased at 1/2 MIC of vancomycin (2.32-fold, p < 0.001), 1/8 MIC and 1/4 MIC of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (1.68-fold, p = 0.002, and 2.14-fold, p = 0.004, respectively), and three sub-MICs of clindamycin (6.50-fold at 1/8 MIC, 6.67-fold at 1/4 MIC, and 6.86-fold at 1/2 MIC, p < 0.001). In contrast, RNAIII transcription decreased at 1/4 MIC of cefazolin (1.95-fold, p = 0.005) and sub-MICs of rifampicin (6.06-fold at 1/8 MIC and 41.67-fold at 1/4 MIC, p < 0.001). In addition, ciprofloxacin reduced the transcript levels of RNAIII at 1/8 MIC (2.40-fold, p < 0.001) but increased the expression of RNAIII at 1/4 MIC (2.56-fold, p < 0.001). Tigecycline increased RNAIII expression at 1/4 MIC (2.07-fold, p = 0.001) and 1/2 MIC (5.40-fold, p < 0.001) (Figure 4B).

In vivo, RNAIII transcript levels were remarkedly reduced by tigecycline by 5.37-fold (p = 0.004) and increased by vancomycin and cefazolin by 5.58-fold (p < 0.001) and 2.05-fold (p = 0.002), respectively (Figure 3B).

Correspondence Analysis Between the Expression of lukE and RNAIII

Table 3 shows the correspondence between the transcription levels of lukE and RNAIII in vitro and in vivo. Our data demonstrate that the expressional variations of RNAIII had a consistent trend with those of lukE when exposed to clindamycin at 1/8 to 1/2 MICs for 5 h; tigecycline at 1/4 MIC for 3 h; vancomycin at 1/8 to 1/2 MICs for 3 h and 1/2 MIC for 5 h; trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole at 1/8 MIC and 1/2 MIC for 3 h and at 1/8 MIC and 1/4 MIC for 5 h; and ciprofloxacin, cefazolin, and rifampicin at 1/4 MIC for 5 h. In the animal abscess model, the expression levels of RNAIII were strongly consistent with those of lukE after exposure to tigecycline, clindamycin, daptomycin, linezolid, vancomycin, and cefazolin.

TABLE 3.

The correspondence of RNAIII and lukE expression in Staphylococcus aureus Newman after antibiotics exposure in vivo and in vitro.

| Antibiotic |

Fold change in expression of RNAIII and lukE in vivo |

Subinhibitory concentration | Fold change in expression of | ||||

|

RNAIII and lukE in vitro |

|||||||

|

3 h of treatment |

5 h of treatment |

||||||

| RNAIII | lukE | RNAIII | lukE | RNAIII | lukE | ||

| Vancomycin | 5.58 | 2.03 | 1/8 MIC | 3.24 | 2.77 | NC | 2.61 |

| 1/4 MIC | 2.24 | 2.73 | NC | 3.31 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | 1.47 | 2.54 | 2.32 | 5.48 | |||

| Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole | / | / | 1/8 MIC | 1.90 | 2.07 | 1.68 | 2.05 |

| 1/4 MIC | NC | NC | 2.14 | 2.29 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | 2.59 | 2.12 | NC | 1.52 | |||

| Clindamycin | NC | NC | 1/8 MIC | 1.65 | NC | 6.50 | 2.40 |

| 1/4 MIC | 1.55 | NC | 6.67 | 2.58 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | 1.58 | NC | 6.86 | 1.73 | |||

| Gentamicin | / | / | 1/8 MIC | 2.74 | NC | NC | 1.80 |

| 1/4 MIC | 1.95 | NC | NC | 1.98 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | 2.04 | NC | NC | 1.91 | |||

| Daptomycin | NC | NC | 1/8 MIC | NC | NC | NC | 1.46 |

| 1/4 MIC | NC | NC | NC | 1.88 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | 1.77 | NC | NC | 1.64 | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | / | / | 1/8 MIC | NC | NC | −2.40 | 1.46 |

| 1/4 MIC | NC | NC | 2.56 | 4.09 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | / | / | / | / | |||

| Cefazolin | 2.05 | 2.57 | 1/8 MIC | NC | NC | NC | −3.92 |

| 1/4 MIC | NC | −1.65 | −1.95 | −5.10 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | / | / | / | / | |||

| Erythromycin | / | / | 1/8 MIC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| 1/4 MIC | NC | NC | NC | −1.47 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | / | / | / | / | |||

| Rifampicin | / | / | 1/8 MIC | −9.90 | NC | −6.06 | NC |

| 1/4 MIC | −12.20 | NC | −41.67 | −1.88 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | / | / | / | / | |||

| Linezolid | NC | NC | 1/8 MIC | 1.63 | NC | NC | −1.91 |

| 1/4 MIC | 1.75 | NC | NC | −2.00 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | / | / | / | / | |||

| Tigecycline | −5.37 | −10.10 | 1/8 MIC | −1.72 | NC | NC | NC |

| 1/4 MIC | 1.37 | 1.89 | 2.07 | −2.71 | |||

| 1/2 MIC | 1.46 | NC | 5.40 | NC | |||

Data indicate increased or reduced fold variation (p < 0.05) in gene transcription compared with control without antibiotic. NC, no change; /, not detected; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Discussion

The S. aureus LukED toxin is able to trigger the damage of host cells and plays a vital role in controlling infection progress (Alonzo et al., 2013; Reyes-Robles et al., 2013; Spaan et al., 2015). Therefore, this toxin may be established as a novel potential target of antitoxin therapy for S. aureus diseases (Nocadello et al., 2016). Antimicrobial treatment for most infections can promote rapid bacterial damage. However, sometimes, elimination of the pathogen does not occur quickly enough to prevent the harmful impact of virulence factors (Hodille et al., 2017). Thus, antibiotics-mediated reduction of virulence factor production was suggested for the treatment of toxin-mediated diseases (Nathwani et al., 2008). Here, we explored the effects of anti-Staphylococcus antibiotics commonly used in the clinic on lukED expression in vitro and in vivo using the S. aureus strain Newman, a good producer of LukED.

Clindamycin, linezolid, erythromycin, gentamicin, and tigecycline, protein synthesis inhibitor compounds, block mRNA translation at the level of the ribosome to suppress the production of staphylococcal exotoxin protein (Hodille et al., 2017). Therefore, these drugs can exhibit broad anti-virulence traits. In this study, we discovered that these drugs at sub-MICs also modulated the mRNA levels (increase or decrease) of lukE (Figure 2). Possible interpretations for this observation are that protein synthesis inhibitors specifically disturb the expression of regulator(s) or two-component signal transduction system(s) that regulate transcription or translation of virulence determinants or that the activities of proteases and RNases affect the formation of the in-process product of the translational complex (Otto et al., 2013; Hodille et al., 2017). Previous reports showed that vancomycin has a minor effect on pvl, hla, and protein A (spa) mRNA levels (Dumitrescu et al., 2007, 2008; Otto et al., 2013; Hodille et al., 2017). Nevertheless, our findings exhibited a significant impact of vancomycin on lukE expression in vitro. This suggests that a cell wall-disrupting agent has the ability to induce some virulence gene expression at subinhibitory levels. It is believed that SOS response, leading to upregulation of an ensemble of DNA repair and recombination genes, can be activated by subinhibitory concentrations of trimethoprim and fluoroquinolones (Bisognano et al., 2004; Goerke et al., 2006; Hodille et al., 2017). In this investigation, the reason for the patently increased lukE expression regulated by trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin may be related to the SOS response. A previous study reported that transcription of lukE is remarkedly stimulated by low concentrations of penicillin and cefalotin (Subrt et al., 2011). However, sub-MICs of cefazolin strongly inhibited this gene transcription in this work. Cefalotin and cefazolin both belong to the first-generation cephalosporins binding to penicillin-binding protein 1 (PBP-1). The PBP-1-specific blockage by β-lactams can also initiate the SOS response (Hodille et al., 2017). However, this SOS-based mechanism of gene activation does not seem suitable to explain our observations. Here, we demonstrate an increased effect and a reduced effect on lukE transcription when S. aureus was exposed to sub-MICs of daptomycin and rifampicin, respectively. A published study showed that daptomycin also induces pvl mRNA, but the effect on hla mRNA level is varied and strain dependent (Otto et al., 2013). Rifampicin inhibits bacteria by suppressing the synthesis of mRNA; therefore, it is not surprising that this drug had an anti-LukED effect at sub-MIC.

It is well known that in vitro treatment with antimicrobials does not sufficiently correlate to clinical exposure to drugs during disease. In contrast to the in vitro data, we measured a pronouncedly increased level of lukE transcript in mice exposed to cefazolin but a significant reduction in the S. aureus burden (Figures 2, 3). Exposure to the protein synthesis inhibitors clindamycin and linezolid or the lipopeptide antibiotic daptomycin in vivo (no effect) was also in contrast to the effects of antibiotics on the transcription of lukE in vitro (Figures 2, 3). However, tigecycline, also a protein synthesis inhibitor, not only inhibited lukE expression in vitro and in vivo but also reduced the bacterial load (Figures 2, 3). The same observation for tigecycline was also reported in a rat burn model (Nosanov et al., 2017). The superior ability of tigecycline in vivo may be correlated with tigecycline-induced differential modification of matrix metalloproteinase-9, which can recruit leukocytes to the site of infection for the elimination of the bacteria (Simonetti et al., 2012).

Previous data from animal model showed that vancomycin was inferior to linezolid (Yanagihara et al., 2009; Martinez-Olondris et al., 2012). In the present investigation, we found that vancomycin had a poorer ability in reducing bacterial level and a stronger role in elevating lukE expression in vivo than had linezolid (Figures 2, 3). The increase or decrease in bacterial counts when using antibiotics may have a significant effect on the production of total virulence factors, which may affect the progress of disease. Therefore, simple in vitro experiments cannot accurately represent the final results, and thus more in vivo experiments are needed to evaluate the effect of antibiotics.

The expression of S. aureus virulence genes is controlled by complicated mechanisms (Pichereau et al., 2012). Many global modulators fine-tune virulence factor expression in response to outside signals such as host defenses and antibacterial agents. A regulator of this kind is the agr quorum-sensing system (Alonzo et al., 2012; Hodille et al., 2017). So far, there have been plenty of studies on the response of agr operon to antibiotics (Joo et al., 2010; Otto et al., 2013; Cazares-Dominguez et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2018). In those studies, the tested antibiotics, such as cephalosporins, penicillin, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, clindamycin, and tigecycline, induced RNAIII transcription, but aminoglycosides and mupirocin had an inhibitory role. Here, we also detected the levels of RNAIII transcript. Table 3 shows that agr activity (RNAIII expression) was modified by 10 of the antibiotics tested (except erythromycin) in a concentration- and/or time-dependent manner in vitro, and lukE transcript levels varied under seven of them (except gentamicin, daptomycin, and linezolid) with a consistent trend. This suggests that most antibiotics tested at sub-MICs may modify lukE expression by affecting agr activity. Moreover, the in vivo experiments of six representative antibiotics also suggested the same conclusion (Figure 3B). Nevertheless, the mechanism by which antibiotics affect agr activity is unclear, and further investigation is needed. It is worth mentioning here that in our study, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, cefazolin, and tigecycline did not show a completely consistent effect on RNA III expression, compared with those drugs mentioned by the above references. We speculate that the reason may be associated with the difference of antibiotic concentration, testing time point, and experimental strain.

The variations in lukE transcript levels may not necessarily translate to a difference in toxin production. Regrettably, we were not able to measure LukED toxin in the present study owing to the lack of a corresponding antibody. In addition, whether the in vitro and in vivo impacts on the Newman strain are applicable to other strains remains to be determined. Despite these shortcomings, our findings may still provide a clue to select suitable antibiotics for the treatment of lukED-positive S. aureus infections.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Shanghai General Hospital ethical committee on animal experiments: 2018DW003.

Author Contributions

HY, SX, and KH carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript. XX and FH provided the laboratory for making experiments. CH, WS, and ZW analyzed the data and interpreted the results. FG and CZ revised the manuscript critically. QL designed the experiments and corrected the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shu Jin (Shanghai People’s Hospital of Putuo District) for providing the methods for the lysis of S. aureus (patent number: ZL201310124795.2).

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81772247 and No. 81371872), Shanghai Jiao Tong University Medical-Engineering Cross Research Youth Fund (YG2016QN31), and Medical Science and Technology Plan (Young Talents) of Zhejiang Province (2019RC256).

References

- Alonzo F., III, Benson M. A., Chen J., Novick R. P., Shopsin B., Torres V. J. (2012). Staphylococcus aureus leucocidin ED contributes to systemic infection by targeting neutrophils and promoting bacterial growth in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 83 423–435. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07942.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo F., III, Kozhaya L., Rawlings S. A., Reyes-Robles T., DuMont A. L., Myszka D. G., et al. (2013). CCR5 is a receptor for Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxin ED. Nature 493 51–55. 10.1038/nature11724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo F., III, Torres V. J. (2014). The bicomponent pore-forming leucocidins of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 78 199–230. 10.1128/MMBR.00055-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciola C. R., Baldassarri L., Von Eiff C., Campoccia D., Ravaioli S., Pirini V., et al. (2007). Prevalence of genes encoding for staphylococcal leukocidal toxins among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus from implant orthopedic infections. Int. J. Artif. Organs 30 792–797. 10.1177/039139880703000908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian D., Ohneck E. A., Chapman J., Weiss A., Kim M. K., Reyes-Robles T., et al. (2016). Staphylococcus aureus coordinates leukocidin expression and pathogenesis by sensing metabolic fluxes via RpiRc. mBio 7:816. 10.1128/mBio.00818-816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson M. A., Ohneck E. A., Ryan C., Alonzo F., III, Smith H., Narechania A., et al. (2014). Evolution of hypervirulence by a MRSA clone through acquisition of a transposable element. Mol. Microbiol. 93 664–681. 10.1111/mmi.12682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisognano C., Kelley W. L., Estoppey T., Francois P., Schrenzel J., Li D., et al. (2004). A recA-LexA-dependent pathway mediates ciprofloxacin-induced fibronectin binding in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 279 9064–9071. 10.1074/jbc.M309836200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cars O. (1990). Pharmacokinetics of antibiotics in tissues and tissue fluids: a review. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 74 23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazares-Dominguez V., Ochoa S. A., Cruz-Cordova A., Rodea G. E., Escalona G., Olivares A. L., et al. (2015). Vancomycin modifies the expression of the agr system in multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Front. Microbiol. 6:369. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep B. A., Afasizheva A., Le H. N., Kajikawa O., Matute-Bello G., Tkaczyk C., et al. (2013). Effects of linezolid on suppressing in vivo production of staphylococcal toxins and improving survival outcomes in a rabbit model of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus necrotizing pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 208 75–82. 10.1093/infdis/jit129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu O., Badiou C., Bes M., Reverdy M. E., Vandenesch F., Etienne J., et al. (2008). Effect of antibiotics, alone and in combination, on panton-valentine leukocidin production by a Staphylococcus aureus reference strain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14 384–388. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01947.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu O., Boisset S., Badiou C., Bes M., Benito Y., Reverdy M. E., et al. (2007). Effect of antibiotics on Staphylococcus aureus producing panton-valentine leukocidin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51 1515–1519. 10.1128/AAC.01201-1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu O., Choudhury P., Boisset S., Badiou C., Bes M., Benito Y., et al. (2011). Beta-lactams interfering with PBP1 induce panton-valentine leukocidin expression by triggering sarA and rot global regulators of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55 3261–3271. 10.1128/AAC.01401-1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaupp R., Wirf J., Wonnenberg B., Biegel T., Eisenbeis J., Graham J., et al. (2016). RpiRc Is a pleiotropic effector of virulence determinant synthesis and attenuates pathogenicity in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 84 2031–2041. 10.1128/iai.00285-216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D. N. (2014). Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy 2016 (Spiral Edition). Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Goerke C., Koller J., Wolz C. (2006). Ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim cause phage induction and virulence modulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50 171–177. 10.1128/AAC.50.1.171-177.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravet A., Colin D. A., Keller D., Girardot R., Monteil H., Prevost G. (1998). Characterization of a novel structural member, LukE-LukD, of the bi-component staphylococcal leucotoxins family. FEBS Lett. 436 202–208. 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01130-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C., Xu S., Zhao H., Hu F., Xu X., Jin S., et al. (2018). Leukotoxin and pyrogenic toxin superantigen gene backgrounds in bloodstream and wound Staphylococcus aureus isolates from eastern region of China. BMC Infect. Dis. 18:395. 10.1186/s12879-018-3297-3290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodille E., Rose W., Diep B. A., Goutelle S., Lina G., Dumitrescu O. (2017). The Role of Antibiotics in Modulating Virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 30 887–917. 10.1128/cmr.00120-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HPA, (2008). Guidance on the Diagnosis and Management of PVL-Associated Staphylococcus aureus Infections (PVL-SA) in England, 2nd Edn, Hpa-An: HPA. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Li M., Shang Y., Liu L., Shen X., Lv Z., et al. (2018). Sub-inhibitory concentrations of mupirocin strongly inhibit alpha-toxin production in high-level mupirocin-resistant MRSA by down-regulating agr, saeRS, and sarA. Front. Microbiol. 9:993. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo H. S., Chan J. L., Cheung G. Y., Otto M. (2010). Subinhibitory concentrations of protein synthesis-inhibiting antibiotics promote increased expression of the agr virulence regulator and production of phenol-soluble modulin cytolysins in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 4942–4944. 10.1128/AAC.00064-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killikelly A., Benson M. A., Ohneck E. A., Sampson J. M., Jakoncic J., Spurrier B., et al. (2015). Structure-based functional characterization of repressor of toxin (Rot), a central regulator of Staphylococcus aureus virulence. J. Bacteriol. 197 188–200. 10.1128/JB.02317-2314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Zheng Z., Kim W., Burgwyn Fuchs B., Mylonakis E. (2018). Influence of subinhibitory concentrations of NH125 on biofilm formation & virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus. Future Med. Chem. 10 1319–1331. 10.4155/fmc-2017-2286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Olondris P., Rigol M., Soy D., Guerrero L., Agusti C., Quera M. A., et al. (2012). Efficacy of linezolid compared to vancomycin in an experimental model of pneumonia induced by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in ventilated pigs. Crit. Care Med. 40 162–168. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822d74a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathwani D., Morgan M., Masterton R. G., Dryden M., Cookson B. D., French G., et al. (2008). Guidelines for UK practice for the diagnosis and management of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections presenting in the community. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61 976–994. 10.1093/jac/dkn096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocadello S., Minasov G., Shuvalova L., Dubrovska I., Sabini E., Bagnoli F., et al. (2016). Crystal structures of the components of the Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxin ED. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 72(Pt 1), 113–120. 10.1107/S2059798315023207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosanov L. B., Jo D. Y., Randad P. R., Moffatt L. T., Carney B. C., Ortiz R. T., et al. (2017). Effectiveness of a glycylcycline antibiotic for reducing the pathogenicity of superantigen-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in burn wounds. Eplasty 17:e27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto M. (2014). Staphylococcus aureus toxins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 17 32–37. 10.1016/j.mib.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto M. P., Martin E., Badiou C., Lebrun S., Bes M., Vandenesch F., et al. (2013). Effects of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on virulence factor expression by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68 1524–1532. 10.1093/jac/dkt073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichereau S., Pantrangi M., Couet W., Badiou C., Lina G., Shukla S. K., et al. (2012). Simulated antibiotic exposures in an in vitro hollow-fiber infection model influence toxin gene expression and production in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain MW2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 140–147. 10.1128/AAC.05113-5111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Robles T., Alonzo F., III, Kozhaya L., Lacy D. B., Unutmaz D., Torres V. J. (2013). Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxin ED targets the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 to kill leukocytes and promote infection. Cell Host Microb. 14 453–459. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudkin J. K., Laabei M., Edwards A. M., Joo H. S., Otto M., Lennon K. L., et al. (2014). Oxacillin alters the toxin expression profile of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 1100–1107. 10.1128/aac.01618-1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti O., Cirioni O., Lucarini G., Orlando F., Ghiselli R., Silvestri C., et al. (2012). Tigecycline accelerates staphylococcal-infected burn wound healing through matrix metalloproteinase-9 modulation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 191–201. 10.1093/jac/dkr440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaan A. N., Reyes-Robles T., Badiou C., Cochet S., Boguslawski K. M., Yoong P., et al. (2015). Staphylococcus aureus targets the duffy antigen receptor for chemokines (DARC) to lyse erythrocytes. Cell Host Microb. 18 363–370. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens D. L., Ma Y., Salmi D. B., McIndoo E., Wallace R. J., Bryant A. E. (2007). Impact of antibiotics on expression of virulence-associated exotoxin genes in methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 195 202–211. 10.1086/510396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subrt N., Mesak L. R., Davies J. (2011). Modulation of virulence gene expression by cell wall active antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 979–984. 10.1093/jac/dkr043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L., Li S. R., Jiang B., Hu X. M., Li S. (2018). Therapeutic targeting of the Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator (agr) system. Front. Microbiol. 9:55. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong S. Y., Davis J. S., Eichenberger E., Holland T. L., Fowler V. G., Jr. (2015). Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28 603–661. 10.1128/CMR.00134-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C. E., Sriskandan S. (2015). Panton-valentine leucocidin expression by Staphylococcus aureus exposed to common antibiotics. J. Infect. 71 338–346. 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne P. A. (2017). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaki J., Synold T., Wong-Beringer A. (2013). Tigecycline induction of phenol-soluble modulins by invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 4562–4565. 10.1128/AAC.00470-413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagihara K., Kihara R., Araki N., Morinaga Y., Seki M., Izumikawa K., et al. (2009). Efficacy of linezolid against panton-valentine leukocidin (PVL)-positive meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a mouse model of haematogenous pulmonary infection. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34 477–481. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Huang K., Xu S., Zhao H., Xu X., Hu F., et al. (2019). The effects of culture conditions on the transcriptional expression of leucocidin ED of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Microb. Infect. 14 23–29. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.