Abstract

Respiratory viral infections are the most important triggers of asthma exacerbations. Rhinovirus (RV), the common cold virus, is clearly the most prevalent pathogen constantly circulating in the community. This virus also stands out from other viral factors due to its large diversity (about 170 genotypes), very effective replication, a tendency to create Th2-biased inflammatory environment and association with specific risk genes in people predisposed to asthma development (CDHR3). Decreased interferon responses, disrupted airway epithelial barrier, environmental exposures (including biased airway microbiome), and nutritional deficiencies (low in vitamin D and fish oil) increase risk to RV and other virus infections. It is intensively debated whether viral illnesses actually cause asthma. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading causative agent of bronchiolitis, whereas RV starts to dominate after 1 year of age. Breathing difficulty induced by either of these viruses is associated with later asthma, but the risk is higher for those who suffer from severe RV-induced wheezing. The asthma development associated with these viruses has unique mechanisms, but in general, RV is a risk factor for later atopic asthma, whereas RSV is more likely associated with later non-atopic asthma. Treatments that inhibit inflammation (corticosteroids, omalizumab) effectively decrease RV-induced wheezing and asthma exacerbations. The anti-RSV monoclonal antibody, palivizumab, decreases the risk of severe RSV illness and subsequent recurrent wheeze. A better understanding of personal and environmental risk factors and inflammatory mechanisms leading to asthma is crucial in developing new strategies for the prevention and treatment of asthma.

Keywords: Asthma, Bronchiolitis, Child, Exacerbation, Genetics, Pathogenesis, Respiratory syncytial virus, Rhinovirus, Risk, Virus, Wheeze, Wheezing

Introduction

Approximately 8–9% of children and adults suffer from asthma in Europe, and it is estimated that an equal number of individuals have asthma-like symptoms [1]. Fortunately, in the majority of patients, asthma is mild, but severe asthma occurs in 5–10% of them [2]. The early stages of asthma, bronchiolitis, or early wheezing affect 10–30% of children depending on definition and 15–25% of children experience recurrent wheezing before school age [3]. Thus, wheezing illnesses and asthma pose a significant health and socioeconomic burden in the world.

Although substantial progress has been made in understanding pathogenetic mechanisms of asthma, its risk-/protective factors, phenotypes, triggers, and differences between children and adults, we still do not truly understand nor can prevent it. Respiratory virus infections appear to be mutual and common triggers; the detection rate has reached 100% among young wheezing children decreasing to 80% in adults [4–6]. Especially, rhinovirus (RV), the common cold virus, is clearly the most common single trigger of exacerbations. It covers up to 76% of exacerbations of wheezing children and up to 83% of adults with asthma [4, 5]. Moreover, it is currently the most potent objective risk factor of school-age asthma among young wheezing children, odds rations (OR) reaching 45 depending on cofactors such as aeroallergen sensitization [7]. Most importantly, RV etiology in first-time wheezing children has served as an effective selection criterion for corticosteroid responders. In two trials, these children have responded to short-course of oral corticosteroid not only by effectively decreasing recurrent wheezing within the subsequent 12 months [3, 8] but also decreasing the incidence of asthma by 30% in a 4–7 years follow-up [9, 10]. These are the only trials that have shown that we can influence the natural course of asthma. Similar but not so marked treatment responses have also been shown in infants suffering from the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)–induced bronchiolitis. In these patients, anti-RSV monoclonal antibody, palivizumab, has decreased the risk of severe RSV illness but also subsequent recurrent wheezing in long-term follow-up [11].

Whether respiratory viruses are causative agents of asthma or just secondary to a certain underlying condition, they are at least clinically relevant revealing factors of biased inflammatory mechanisms. By understanding the factors that increase susceptibility to virus infections and virus-induced inflammatory mechanisms in asthma, we are likely to better understand the pathogenesis of asthma and to identify novel targets for preventive strategies. The aim of this article is to review the role of virus infections in the pathogenesis of asthma inception and exacerbations, as well as to discuss interrelated protective and risk factors of asthma and treatment options.

Virus etiology from bronchiolitis to asthma

Respiratory virus infections play a significant role in all wheezing (defined as a bilateral whistling sound during expiration accompanied by dyspnea) illnesses from bronchiolitis to asthma. Virus detection rates using PCR have reached 100% in bronchiolitis, 85–95% in children with recurrent wheezing or asthma exacerbation, and 80% in adults with asthma exacerbation [3]. The virus coinfection rate is typically 10–40% being more common in young children [12]. However, only a few studies support their association with a more severe clinical course [13]. It should be noted that virus detection rates using PCR may be over 35% level in asymptomatic subjects, especially in young children which sometimes question the significance of virus detection [3].

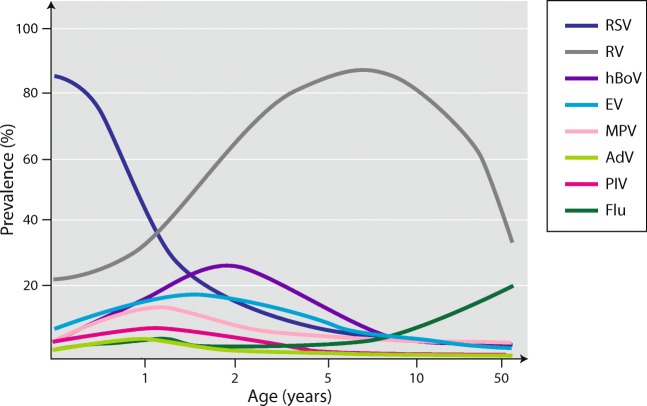

According to the majority of guidelines, bronchiolitis is generally defined as virus infection of the lower respiratory tract (bronchioles and their surrounding tissues) in children less than 2 years of age [14]. RSV is the most important causative agent during infancy, and its detection rates range 50–80% in hospitalized cases (Fig. 1) [12, 13]. RV is the second most common etiologic agent during infancy (and the most common outside RSV epidemics), but it starts to dominate virus detection approximately after 12 months (Fig. 1) [12–14]. The next most common etiologic viruses are human bocavirus and human metapneumovirus (detection rates may reach 10–25%) followed by the parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, coronavirus, and influenza virus each of which typically make less than 10% (Fig. 1). In children with recurrent wheezing and asthma exacerbation, as well as adults with asthma exacerbation, RV clearly dominates as a trigger [4, 12]. Its detection rate has reached 76–83% in adults.

Fig. 1.

Virus etiology from bronchiolitis and childhood wheezing to asthma. RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus; hBoV, human bocavirus; Flu, influenza virus; EV, enteroviruses; MPV, metapneumovirus; PIV, parainfluenza virus; AdV, adenovirus

Rhinovirus

Rhinovirus is a non-enveloped positive-strand RNA virus in the family Picornaviridae, genus Enterovirus, and is classified into three species (RV-A, B, and C) [3]. There are over 170 distinct RV genotypes, including 80 RV-A, 32 RV-B, and 65 RV-C genotypes. The RV-C group was not found until 2006 (approximately 50 years after the first discovery of other RVs) since it does not grow in conventional cell cultures. Currently, PCR is the method of choice in identifying RVs from nasal secretions. We are moving towards RV species specific diagnosis since RV-A and RV-C appear to cause the more severe course of illness than RV-B [15]. Nevertheless, the common cold is the main type of illness. Up to 35% of asymptomatic subjects may be positive for RV [3]. RV does not cause chronic infection or “colonization” in healthy individuals [3]. RV circulates year-round with multiple coexisting genotypes that potentiate its asthmagenic activity [3]. Peak prevalence in temperate climates occurs in the early autumn and late spring. In exacerbations of asthma, RV-A and RV-C are clearly more common etiologic RV species than RV-B—similar to wheezing illnesses in early childhood [16, 17].

RV-C has also been the most common RV species among hospitalized and intensive care unit asthma patients [18]. Patients with CDHR3 (cadherin-related family member 3) asthma risk allele and atopic individuals have been more susceptible to RV-C infections (see below) [19, 20]. At the cellular level, RV-C has caused faster replication rate and induction of more robust cellular responses than RV-B, as demonstrated in cultures of differentiated airway epithelial cells [3]. Overall, the clinical impact of RV-A is close to RV-C among asthmatic subjects, whereas the impact of RV-B is much weaker. Cohort studies have, however, shown that RV-B infections may slightly increase the risk of exacerbation in children whose asthma is of greater severity [3, 21].

Respiratory syncytial virus and other viruses

As mentioned above, other species than RV do not appear to be of major significance as triggers of asthma. Typically, the first infection with RSV or with its close relative, metapneumovirus, may be severe and cause bronchiolitis [14]. However, reinfections, which typically occur annually, are mild. Human bocavirus seconds to RV in the age group of 2–5-year-olds cause severe lower airway illnesses and by the age of 5 years, practically all children have acquired protective antibodies [6]. Influenza virus infection may contribute to asthma attacks in adults, but due to effective vaccination programs, they have become rare [4, 22]. Coronaviruses (excluding SARS and MERS), parainfluenza viruses, adenoviruses, and respiratory polyomaviruses (KI and WU) typically cause just upper airway infections.

Genetics and epigenetics of asthma and virus susceptibility

Asthma is a highly heritable disease with heritability estimates from twin studies of more than 50%, and even higher for childhood asthma [23]. Genetics is, therefore, one important tool for understanding the disease mechanisms of asthma. Our knowledge of the genetic background of asthma has increased rapidly during recent years through methodological advances allowing so-called genome-wide association studies (GWAS) where millions of genetic variants covering the entire genome can be tested without a prior hypothesis about underlying mechanisms. Large GWAS have now identified more than 100 genes/loci associated with asthma and related traits, with the strongest signal seen for the childhood-onset disease [24]. Of these, the majority of susceptibility genes are related to the immune system.

The first asthma locus discovered in GWAS, approximately 10 years ago, was the chromosome 17q21 locus [25]. It is still the strongest known asthma locus, and it is particularly associated with childhood-onset asthma and asthma with severe exacerbations [26]. Interestingly, the 17q21 asthma locus is strongly associated with increased risk of early wheezing episodes triggered by viruses, including rhinoviruses, and children with early viral wheezing have a much higher risk of later asthma if they carry 17q21 risk variants [27]. Also, 17q21 risk variants seem to interact with several environmental factors so that children with risk variants are more susceptible to having older siblings in terms of increased risk of early wheeze, but also more protected against asthma when exposed to a farming environment or pets in the household in early life [28]. The biological mechanisms associated with the 17q21 locus are still incompletely understood and might involve several genes in the region, including ORMDL3, GSDMB, GSDMA, PGAP3, ERBB2, and IKZF3 and several cell types, including immune and airway epithelial cells [26]. Most follow-up studies have focused on ORMDL3 as the causal gene with proposed mechanisms related to sphingolipid synthesis [29], regulation of eosinophils [30], and regulation of the ICAM1 receptor, which might explain the susceptibility for rhinovirus infections [31]. Further understanding of the biological pathways related to this locus might provide important novel clues to the mechanisms of viral infections and asthma.

Another asthma risk gene, CDHR3, was discovered in a GWAS of childhood asthma with recurrent acute hospitalizations before 6 years of age [32]. Experimental studies have later demonstrated that CDHR3 functions as a rhinovirus-C receptor and is highly expressed in differentiated bronchial epithelial cells [33]. The association between CDHR3 risk variants and rhinovirus-C respiratory illness was subsequently confirmed clinically in birth cohorts [19]. These findings suggest that the mechanism associated with CDHR3 variants is at least partly explained by an increased risk of rhinovirus-C respiratory illnesses and that targeting CDHR3 might be a strategy for preventing rhinovirus-C triggered asthma exacerbations.

Genetic discoveries in GWAS require a very large number of participants, and large well-powered GWAS of respiratory viral infections per se have not yet been performed. One smaller GWAS of bronchiolitis was performed without genome-wide significant findings [34]. Candidate gene studies, most focusing on RSV bronchiolitis, have suggested several susceptibility genes related to immune regulation and surfactant proteins [35]. Several of these genes have also been associated with asthma, indicating that the association between RSV bronchiolitis and later asthma development might partly be explained by shared genetics.

Epigenetics, defined as heritable changes in gene expression without changes in the underlying DNA sequence, is one mechanism by which environmental factors can affect gene regulation and may explain long-term programming of disease from early life exposures and changes in disease status time. The most commonly studied epigenetic mechanism is DNA methylation. A large genome-wide study on methylation indicated the role of methylation in eosinophils in the pathogenesis of asthma [36]. Since methylation is tissue-specific, it might be crucial to study the relevant “target-organ,” and two genome-wide studies of methylation in nasal epithelium have found several differentially methylated sites associated with allergic sensitization and asthma [37, 38].

In order to understand the genomics of asthma and virus infections, we need more studies that combine information on gene variants, gene expression, and epigenetics in relevant cells and also assessed during acute symptoms with information on specific infectious triggers. Such studies are challenging, but also have the potential to reveal unknown disease mechanisms and functional subtypes of the disease, which is essential in order to personalize and improve treatment and prevention of disease.

Risk factors of asthma

Severe acute bronchiolitis or early wheezing is associated with an increased risk of subsequent asthma [3]. This disease may persist until early adulthood, and the strongest association with worse long-term prognosis was observed in children infected with RV-C and RV-A virus (Fig. 2) [39]. These observations come from cohort (population) studies, where the most striking relationship was recorded in children at high risk, i.e., in patients hospitalized due to severe disease, in children from atopic families, and children with atopy (Fig. 2) [3]. Coexpression of aeroallergen sensitization or 17q21 asthma risk alleles increased the odds ratios to the level of 20–45 (Fig. 2) [7, 27]. Collectively, these findings suggest that RV is most likely a revealing factor for those with early airway inflammation (i.e., broken epithelial barrier, T helper2 cell polarized immune events), genetic variation children (i.e., may markedly increase the risk of asthma), and/or low interferon responses (i.e., impaired viral defense) and therefore serves as a clinically useful risk marker [7, 19, 27, 40, 41].

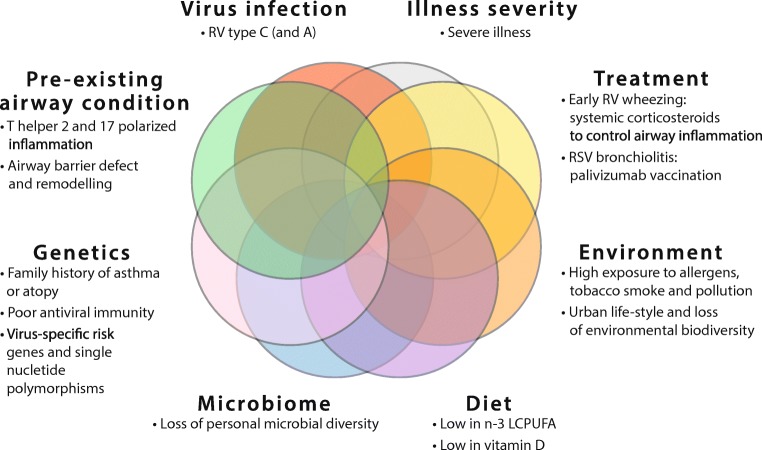

Fig. 2.

Major factors influencing asthma risk in young children suffering from bronchiolitis. RV, rhinovirus; virus; n-3 LCPUFA, n-3 (omega-3) long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids

Before the discovery of the link between RV-induced bronchiolitis and later asthma, it was long thought that RSV is the key “asthma-inducing” pathogen (Fig. 2). Several studies have reported an association between RSV bronchiolitis and school-age asthma but not with atopy, excluding one relatively small cohort study [3]. However, odds ratios have been at a relatively low level (OR 2.5–4.5), and these studies were limited in not investigating RV etiology. Similar risk numbers have also been found in pre-term infants, which are also more susceptible to severe RSV infections [14]. Other risk factors include young age, parental smoking, and common asthma risk genes [3, 14]. Unlike with RV, RSV causes more direct damage to the airway epithelium, but still, the common perception is that RSV infection is not causal to asthma or atopy development. Children with RSV infection are likely to share common genetic vulnerability and/or environmental exposures that predispose them to both diseases (Fig. 2) [3, 14].

We have recently reviewed the main non-viral risk and protective factors of asthma and summarized in Fig. 2 [3, 14]. Rapid urbanization, pollution, and climate change, all leading to the loss of biodiversity, promote chronic non-communicable illnesses such as asthma and allergies [42]. Exposure to pollutants such as NO2 and high exposure to allergens in children with allergic asthma increase the severity of virus-induced exacerbations of asthma. Maternal stress and depression have been associated with acute wheezing illnesses. Of dietary ingredients, low maternal omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (n-3 LCPUFA) has increased the risk of persistent wheeze/asthma in offspring [43]. Low vitamin D levels increase susceptibility to virus-induced wheezing and severity of asthma. However, recommended supplementation has mainly abolished its effect [44]. Common protective factors of allergy and asthma include a healthy lifestyle (healthy nutrition, exercise, outdoor activities), diverse personal microbiome, non-polluted air, and environmental biodiversity, as well as contact with animal and farm dust.

Viruses and microbiome

As described above, there is evidence of a viral trigger in most acute asthma episodes. However, also, bacteria might play an important role in the pathology of acute asthma symptoms. As an example, young children with acute wheezy episodes had increased detection rates of the bacterial pathogens Moraxella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae in hypopharyngeal aspirates [45]. Indirect evidence of a potential causal role of bacteria for such acute symptoms comes from findings that treatment with the antibiotic azithromycin reduced the symptom burden of such episodes [46, 47], although this can also be due to anti-viral or anti-inflammatory effects of macrolides.

Similar to viruses, airway bacteria have also been suggested as early life risk factors for later development of asthma, as indicated by an association between the detection of pathogenic bacteria in the airways of asymptomatic infants and later development of asthma [48]. Also, the gut microbiome, a putative risk factor for asthma, might influence the susceptibility to viral infections in the airway as indicated by a mouse model where supplementing with Lactobacillus johnsonii protected against RSV infection [49].

In addition, there is substantial evidence of the interaction between airway bacteria and viruses. In a study of acute respiratory symptoms in healthy and asthmatic children, rhinovirus was associated with increased detection of bacterial pathogens, and Moraxella catarrhalis and Streptococcus pneumoniae seemed to contribute to the severity of respiratory tract illnesses and asthma exacerbations [50]. At the epidemiological level, the seasonal peaks of several viral infections are associated with increased hospital admission for invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae disease [51]. There are several mechanisms by which viral infections can increase the risk of bacterial infections, including immune suppression, epithelial damage, and changes in the local lung environment altering the growth conditions for pathogenic bacteria. But also the other way around, bacterial infection and/or colonization of the airways might increase the risk of later viral infection. Vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae in a randomized trial resulted in subsequent reduced risk of virus-associated pneumonia [52]. There is also evidence of interaction between viruses and the microbiome in studies using a broader sequencing-based characterization, whereby both culturable and non-culturable bacteria can be detected. One study found an association between a nasopharyngeal microbiome characterized by Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus and RSV hospitalization [53], and another study found that a nasopharyngeal microbiome dominated by Streptococcus in asymptomatic infants was associated with later wheezing [54]. These findings emphasize the importance of assessing both bacteria and viruses in studies of asthma etiology in order to address their individual roles and the impact of their interaction.

Pathogenesis of asthma

Asthma is a syndrome characterized by intermittent attacks of breathlessness, wheezing, and cough accompanied by variable airflow obstruction. Asthma is now considered an umbrella diagnosis for several diseases with distinct mechanistic pathways (endotypes) with variable clinical phenotypes (childhood atopic, non-atopic, middle-aged obese, and elderly late-onset). An important molecular mechanism of asthma is the chronic inflammation of conducting airways, even during asymptomatic periods. This inflammation is different in various asthma endotypes and may broadly be divided into Th2 high (atopic, eosinophilic) and Th2 low (non-atopic, non-eosinophilic) endotypes [55].

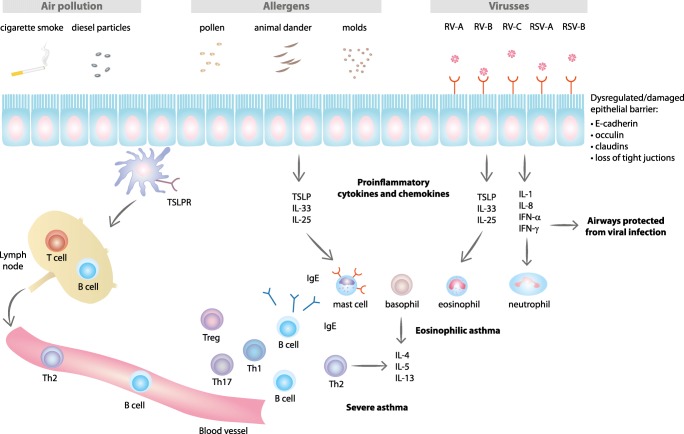

Type 1 and type 2 immune responses are regulated by T helper 1 (Th1) and 2 (Th2) cells, respectively. Th1 cells secrete IL-2 and IFN-γ and stimulate type 1 immunity characterized by phagocytic and anti-viral activity [56]. Th2 cells mainly secrete inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 that stimulate Th2 type immunity characterized by eosinophilia and high antibody titers (Fig. 3) [57]. Th2 type immune response is induced by parasites, but it is also associated with the atopic disease; allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma [58]. Th2 type responses are mediated by eosinophils, basophils, mast, Th2, and IgE-producing B cells (Fig. 3). Increased production of type 2 cytokines leads to allergen-triggered IgE hypersensitivity and activation of mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, airways epithelial cells, and remodeling of airways (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Airway epithelial pathways impacted by environmental exposures and type 2 immune responses in asthma pathogenesis. Exposure to air pollutants (cigarette smoke, diesel particle, etc.) cause oxidative stress. Mold and other allergens stimulate epithelial cells and induce activation of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Respiratory viruses (RV and RSV) interact with specific receptors on epithelial cells. Damaged or dysregulated epithelial barrier in asthmatic patients also affects type 2 inflammation. Release of cytokines and chemokines promotes activation and mobilization of type 2 immune responses. CDHR3, cadherin-related family member 3; CX3CR1, CX3C chemokine receptor 1; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IFN, interferon; IgE, immunoglobulin E; IL, interleukin; LDLR, low-density lipoprotein receptor; RV-A, RV-B, RV-C, rhinovirus-A, rhinovirus-B, rhinovirus-C; RSV-A, RSV-B, respiratory syncytial virus-A, virus-B

Childhood asthma is often associated with other allergic diseases, such as atopic eczema and allergic rhinitis. Th2 type inflammation in the airways often starts in childhood, when environmental stimuli such as viral respiratory tract infection, exposure to parental smoking, and NO2 and other airborne pollutants or allergens activate airway epithelial cells to produce type 2 inflammatory cytokines including IL-25, IL-33, or TSLP (thymic stromal lymphopoietin) (Fig. 4) [56]. This initiates a cascade that leads to the development of childhood asthma (Figs. 3 and 4). The reason why this Th2 type response persists in some patients is not well known.

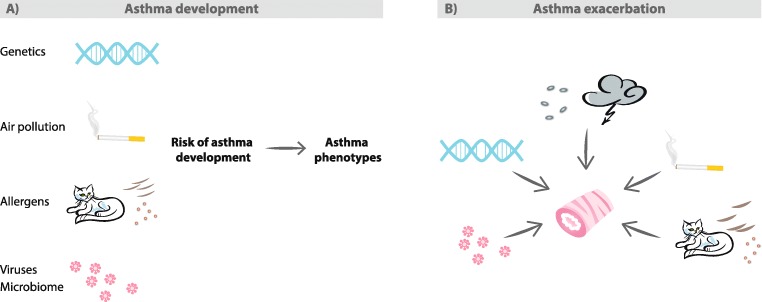

Fig. 4.

Summary of environmental factors affecting developmentaand exacerbationsbof asthma. A) Interplay of environmental (air pollution, allergens, viruses) and host (genetic, microbiome) factors shape the risk of asthma development and predispose to different asthma phenotypes. B) Environmental exposures to allergens (animal, pollen, mold), viruses, cigarette smoke, and air pollution are known triggers for asthma exacerbations. Thunderstorms are associated with asthma exacerbations. Thunderstorms produce ozone and release allergen-bearing small particles that irritate airways. Avoidance of environmental exposures can improve asthma control and reduce exacerbations

Having allergic sensitization and eczema at the time of wheezing with rhinovirus are all risk factors of having atopic asthma at the age of 7 years [59]. On the contrary, having RSV as the cause of the first wheeze before the age of 1 year or exposure to parental smoking are both associated with non-atopic asthma at age 7 years [59].

A recent study showed that the risk of developing asthma was highest in infants having IgE sensitization and wheeze due to rhinovirus-C infection [39]. These results suggest that mechanisms of virus-induced illnesses differ. The mechanisms underlying the observed associations between rhinoviruses, allergic sensitization, and the development of asthma are not fully understood. It is possible that there is a causal relationship where acute rhinovirus infection induces various cellular factors regulating host response, airway inflammation, repair, and remodeling, as well as increase proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production (Fig. 4) [60, 61]. Also, rhinovirus infection and allergen exposure increase epithelial cells to produce IL-25 and IL-33, thus promoting Th2 type inflammation (Fig. 3) [62–64]. Alternatively, virus infection can simply be an early marker of impaired anti-viral response; diminished type I and III interferon production and/or abnormal host response; induced expression of IgE receptors [65] or genetic susceptibility to rhinovirus infection due to enhanced expression of rhinovirus-C receptor CDHR3 in the airway epithelium [32]. Most likely, all of these mechanisms play a role in the development of either atopic or non-atopic asthma.

Treatment of viral wheeze to prevent asthma

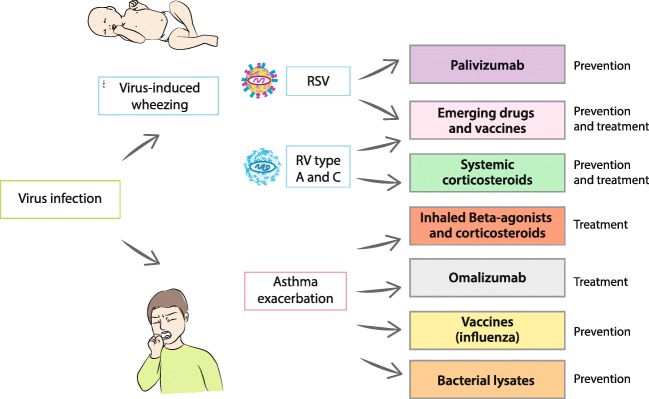

Several therapeutic strategies have been shown to alter the natural history of virus-induced asthma exacerbations (Fig. 5). In general, such treatment would need to be applied as early as possible during infection to increase the chances of success, safety, and be easy to administer.

Fig. 5.

Current strategies for asthma prevention and treatment. Details in text. RV, rhinovirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus

Prevention

Currently, there exist no safe and effective human vaccines for RSV nor RV. The major obstacle is an antigenic diversity of the more than 100 serotypes of rhinovirus, meaning that creating a successful vaccine is an extremely challenging task [66]. In the development of the RV vaccine, promising results have been seen with a cross-reactive recombinant capsid protein in a mouse model [67]. Recently, attention has been caught to live attenuated vaccines and subunit vaccines against RSV combined with Th1-enhancing adjuvant, although neither of them seems likely to be introduced to routine clinical practice soon [68].

Prevention and treatment of RSV

Palivizumab

A humanized monoclonal antibody against the RSV fusion (F) protein, currently used for immunoprophylaxis was proved to decrease the risk of hospitalization due to severe RSV illness among pre-term infants (72% reduction), those with chronic lung disease (65% reduction), and hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease (53% reduction) [68]. The application of palivizumab resulted in a remarkably reduced risk of recurrent wheezing episodes following hospitalization due to RSV, but not asthma [11]. Interestingly, a new, second-generation high-affinity derivative of palivizumab (motavizumab) did not prevent long-term recurrent wheezing despite reducing the rate of severe acute RSV disease [69].

Ribavirin

There is no convincing data supporting ribavirin treatment for severe RSV infection, while there are concerns about its toxicity. Therefore, ribavirin is neither recommended in the USA nor any European guidelines [70].

New approaches

At this time, there are 17 new RSV vaccines and biologicals in a pipeline of clinical trials while another 28 are in pre-clinical development [68]. Numerous new molecules have already been characterized as capable of inhibiting RSV dissemination within the airways and are investigated as potential candidates for pre-clinical and clinical development [66].

Prevention and treatment of rhinovirus

Drugs (pleconaril, amantadine, rimantadine)

Although it is hypothetically possible nowadays to interfere with every step of the infectious cycle of respiratory tract viruses (from viral attachment, viral entry and uncoating, translation, replication, and onward to virus release), only a few approaches have met with success with RV thus far. There is only a limited number of agents that interact with the RV attachment to the cell or uncoating of the viral RNA that have been tested in clinical trials (pleconaril, amantadine, rimantadine) [71]. Regrettably, their clinical applicability is continuously questioned due to adverse events (pleconaril, vapendavir) or drug resistance (amantadine, rimantadine) [66].

Prednisolone

According to current evidence, early systemic anti-inflammatory management may drastically affect the natural course of asthma development, probably via targeting pre-existing Th2-skewed immunity and/or virus-induced airway inflammatory response.

Two separate randomized trials exist, in which oral corticosteroid, prednisolone, has been applied to wheezing children with RV etiology. Intriguingly, prednisolone application was shown to decrease the time to the physician-confirmed relapse within the following year (by 20–30%) and time to the initiation of asthma controller medication within the following 5 years (by 30–40%) in these children [8, 9, 72, 73]. Noteworthy, high RV genome load in the placebo-treated wheezing children was associated not only with the development of a new wheezing episode within 100 days in every case but also with the initiation of asthma medication within the next 14 months in every case [72, 73]. These results indicate that systemic anti-inflammatory treatment of the first RV-induced severe wheezing episode may markedly decrease the subsequent risk for asthma.

Long-term sequela

Whether RV bronchiolitis is the cause of severe lung injury, resulting in subsequent wheezing episodes and development of asthma or if there is an inborn susceptibility to both acute bronchiolitis and subsequent asthma remains still a matter of debate. Nevertheless, the major viral causes of acute bronchiolitis/first wheeze are RSV and RV, which seem to have a different course in post-bronchiolitis asthma sequela, apart from underlying lung morbidity (for review, see Jartti et al. [14]).

Subsequently, two prospective studies with RSV immunoprophylaxis have been performed to address the potential causality between RSV infection and subsequent asthma. In these recent randomized controlled trials, pre-term infants who received palivizumab demonstrated a decreased number of recurrent wheezing episodes, but the incidence of physician-diagnosed asthma at age 6 remained intact [74, 75]. These effects, however, were less noticeable in infants with atopic family history, indicating that RSV infection is not causal to asthma or atopy development.

On the contrary, atopy is associated with childhood asthma inception after RV-induced bronchiolitis. A study in high-risk birth cohort (parental atopy or asthma) from WI, USA, has demonstrated that in young children who experienced RV-induced bronchiolitis, there is a high risk of school-age asthma (OR 9.8 vs. 2.6; RV vs. RSV), and the risk becomes even higher in children sensitized at an age younger than 2 [7, 76]. Another study from Turku, Finland, shows strikingly similar results. In infants at the age of less than 2 years, who developed RV-induced bronchiolitis, the odds ratio for atopic asthma at school age was 5.0, which increase up to 12 when combined with early sensitization [59].

RSV-induced bronchiolitis was neither associated with atopic nor non-atopic asthma [59]. Altogether, the above-presented data suggest that airways in “high-risk” individuals display an increased susceptibility for asthma inception after RV-induced bronchiolitis [77]. Protection of these high-risk children against the effects of severe respiratory infections during infancy may represent an effective strategy for primary asthma prevention.

Mechanisms of asthma exacerbation

Asthma exacerbation is defined as an acute or subacute worsening of asthma symptoms and lung function as compared to the patients’ usual health status. Exacerbations usually occur in response to a variety of external agents, including respiratory viruses, bacteria, allergens, air pollutants, smoke, and cold or dry air (Fig. 4). However, it is estimated that up to 85–95% of asthma exacerbations in children and 75–80% in adults are linked to viral infections. However, most viral infections are not associated with acute exacerbations, and cofactors, including bacterial and allergic inflammation, have been described to increase the severity of exacerbation (Fig. 4). The most common viral triggers for asthma exacerbation are rhinoviruses, particularly subtypes A and C [15]. Hospital admissions for asthma exacerbations correlate with a seasonal increase of RV infections in autumn from September to December and again in spring [15, 78].

Other respiratory viruses may also cause exacerbations. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which frequently causes wheeze in infants and young children, can also trigger acute asthma exacerbation in adults [79]. Human metapneumovirus, influenza, parainfluenza, adenovirus, coronavirus, and bocavirus have all been detected in asthma exacerbations but in lower frequencies [3].

Several mechanisms why asthmatics are predisposed to viral infections have been proposed. One of the proposed reasons is damaged epithelium, which may increase susceptibility to infection and ultimately lead to airway obstruction (Fig. 3) [80]. Cellular mechanisms involved in viral response include disruption of the epithelial barrier and tight junctions, impaired apoptosis, increased cell lyses, deficient Th1 response and reduced IFN-γ production, and enhanced expression of viral receptors (Fig. 3) [80]. Viral infection also induces proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukins as well as mediators or remodeling (VEGF, FGF) (Fig. 3) [71].

Viruses attach to their unique cellular receptors: intercellular adhesion protein 1 (ICAM-1) is used by the majority of RV-A and all RV-B types, low-density lipoprotein receptor family members (LDLR) are used by RV-A, cadherin-related family member 3 (CDHR3) is used by RV-C, and CX3CR1 is used by RSV (Fig. 4) [33, 81, 82]. Interestingly, the corresponding gene for CDHR3 has been linked to childhood asthma with severe asthma exacerbations [32].

Airway epithelial cells form a barrier to the outside world and are the front line of mucosal immunity (Fig. 4). Cytokines and inflammatory mediators associated with allergic inflammation induce epithelial barrier disruption. Additional factors that influence the severity of the viral infection and the risk of asthma exacerbation are allergic sensitization and the airway microbiome. For example, RV infection and allergic sensitization synergistically increase the risk of exacerbation [3]. Atopic asthma with allergic sensitization can be associated with reduced virus-induced IFN responses, increased viral shedding, and decreased viral clearance [3].

Moreover, bronchial epithelial cells of atopic asthmatics have shown to have increased RV replication, deficient IFN-γ release, and enhanced cell lysis [83]. Studies with omalizumab, anti-IgE, have shown that neutralizing IgE-mediated inflammation can enhance IFN responses and reduce virus-induced asthma exacerbations in children [84]. This finding suggests that neutralizing IgE indirectly improve anti-viral responses.

Several studies have shown that viral infections precede bacterial infections in airways. This phenomenon may occur due to several reasons; viruses may induce expression of airways receptors used by bacteria, viruses may disrupt epithelial barrier, and they increase the release of inflammatory cytokines and mediators causing increased inflammation and risk of asthma exacerbations (Fig. 4) [85]. In addition, patients with asthma are frequently colonized with bacteria in lower and upper airways [48], and acute wheezing in infants has been associated with both viral infections and airway microbiota dominated by bacterial pathogens [50]. Bacterial infections may impair mucociliary clearance and increase mucus production. However, evidence linking bacterial infections to acute asthma exacerbation is limited.

Treatment of asthma in regard to viral infections

Exacerbations of asthma are characterized by a progressive increase in symptoms of shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, and progressive decrease in lung function. Viral respiratory infections remain a leading cause of asthma exacerbations, both in children and adults. The presence of any pathogen is usually associated with a higher risk of treatment failure [86]. Typically management of all asthma exacerbations includes a symptomatic treatment increasing doses of beta 2-agonists, enhancing the use of inhaled or oral glucocorticosteroids [87].

Glucocorticosteroids

Glucocorticosteroids are by far the most widely used drugs in children with asthma and have potent anti-inflammatory activity. In recent years, an increasing body of pre-clinical evidence supports their use in combination with long-acting beta-agonists, such as salmeterol and formoterol, and highlights the superiority of combination therapy in asthma exacerbations over either drug alone. Combination of either salmeterol and fluticasone or budesonide and formoterol treatment in vitro has been shown to synergistically suppress induction of several chemokines (CXCL8, CCL5, and CXCL10) and remodeling-associated growth factors (including FGF and VEGF) upon RV infection (for review see Jackson and Johnston [71]). The effective suppression of growth factors highlighted above certainly represents a plausible mechanism through which these drugs might inhibit virus-driven inflammation and remodeling.

Omalizumab

Surprisingly, systemic anti-IgE treatment was also shown to markedly reduce infection-induced severe asthma exacerbations. A year-round treatment with omalizumab has been shown to abolish the seasonal peaks in asthma exacerbations, most of which are associated with RV infection [84]. Parallel to the IgE neutralization by the drug, clinical benefit was associated with enhanced IFN-γ responses, suggesting that omalizumab may improve the anti-viral responses [88].

Influenza vaccine

Influenza contributes to some acute asthma exacerbations. Children with asthma should remain a priority group for influenza immunization because of the newly established association between influenza and ED management failure combined with well-recognized influenza-related complications [88]. This recommendation has been ultimately confirmed by a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, showing that influenza vaccination reduced the risk of asthma exacerbations [22].

Immunomodulators and bacterial lysates

Among several non-specific anti-viral approaches to reduce asthma include strategies aiming at enhancing the patient’s resistance to multiple respiratory viruses through the administration of immunostimulatory preparations [66, 89]. Pidotimod is a synthetic thymic dipeptide that appears to share several mechanistic similarities with bacterial immunomodulators, and it is thought to stimulate toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4, which are expressed on DCs, this displaying anti-infective effects. To date, there is only one prospective multicenter trial, showing that pidotimod reduced the number of respiratory infections in a mixed group of children over half of whom had atopic conditions, including asthma [90].

Bacterial lysates have recently been proved to reduce the number of the recurrent wheezing episodes and asthma episodes, in patients treated with BL compared with placebo (5 trials) [91]. However, higher-quality trials are required before firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the prophylactic efficacy of bacterial lysates in asthma. A new large scale trial, currently carried out in the USA (ORal Bacterial EXtracts for the prevention of wheezing lower respiratory tract illness, ORBEX, NCT02148796; N = 1000) will address these concerns, but its results are expected in 2022.

Anti-virals

There are several novel approaches, being tested in laboratories and clinical research for their ability to target RV-induced infection. These include soluble ICAM-1 receptor interfering with RV attachment (tremacamra), and two anti-viral drugs (pleconaril and ruprintrivir) as well as the application of inhaled IFN-β after the onset of a respiratory tract viral infection in asthmatic subjects. All of them, however, show only marginal benefit in symptoms, viral replication, and development of clinical symptoms of colds, while exhibiting substantial side effects [71].

Conclusions

There is an abundance of data showing that RV-C and RV-A contribute to asthma development and/or is a marker of asthma susceptibility.

Using viral markers in relation to treatment might be a good strategy to prevent asthma.

Oral application of corticosteroids may change the natural history of asthma.

Treatment of virus-induced wheezing/asthma exacerbations with high-dose corticosteroids prevents destructive cytokine release in the airways.

Here we suggest that prevention and treatment of recurrent wheezing may in the foreseeable future be based on virological tests at the first episode of wheezing. Thereby, existing treatment methods (beta2-agonists and corticosteroids) may be more effective when given to a distinct (RV-affected) high-risk group of patients making treatment more personalized.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mrs. Agnieszka Sierakowska for her graphical assistance.

Funding information

This study was supported by the Paulo Foundation, Helsinki, Finland (TJ), and the Finnish Allergology and Immunology Foundation, Tampere Tubeculosis Foundation (VE), Fundacja Respira (WF).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

WF has received speaker honoraria from Vifor Pharma. VE and KB declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Selroos O, Kupczyk M, Kuna P, Lacwik P, Bousquet J, Brennan D, Palkonen S, Contreras J, FitzGerald M, Hedlin G, Johnston SL, Louis R, Metcalf L, Walker S, Moreno-Galdo A, Papadopoulos NG, Rosado-Pinto J, Powell P, Haahtela T. National and regional asthma programmes in Europe. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24(137):474–483. doi: 10.1183/16000617.00008114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lang DM. Severe asthma: epidemiology, burden of illness, and heterogeneity. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015;36(6):418–424. doi: 10.2500/aap.2015.36.3908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jartti T, Gern JE. Role of viral infections in the development and exacerbation of asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(4):895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papadopoulos NG, Christodoulou I, Rohde G, Agache I, Almqvist C, Bruno A, Bonini S, Bont L, Bossios A, Bousquet J, Braido F, Brusselle G, Canonica GW, Carlsen KH, Chanez P, Fokkens WJ, Garcia-Garcia M, Gjomarkaj M, Haahtela T, Holgate ST, Johnston SL, Konstantinou G, Kowalski M, Lewandowska-Polak A, Lodrup-Carlsen K, Makela M, Malkusova I, Mullol J, Nieto A, Eller E, Ozdemir C, Panzner P, Popov T, Psarras S, Roumpedaki E, Rukhadze M, Stipic-Markovic A, Todo Bom A, Toskala E, van Cauwenberge P, van Drunen C, Watelet JB, Xatzipsalti M, Xepapadaki P, Zuberbier T (2011) Viruses and bacteria in acute asthma exacerbations--a GA2LEN-DARE systematic review. Allergy 66(4):458–468. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02505.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Turunen R, Koistinen A, Vuorinen T, Arku B, Soderlund-Venermo M, Ruuskanen O, Jartti T. The first wheezing episode: respiratory virus etiology, atopic characteristics, and illness severity. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25(8):796–803. doi: 10.1111/pai.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen A, Kesti O, Elenius V, Eskola AL, Dollner H, Altunbulakli C, Akdis CA, Soderlund-Venermo M, Jartti T. Human bocaviruses and paediatric infections. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(6):418–426. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubner FJ, Jackson DJ, Evans MD, Gangnon RE, Tisler CJ, Pappas TE, Gern JE, Lemanske RF., Jr Early life rhinovirus wheezing, allergic sensitization, and asthma risk at adolescence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(2):501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehtinen P, Ruohola A, Vanto T, Vuorinen T, Ruuskanen O, Jartti T. Prednisolone reduces recurrent wheezing after a first wheezing episode associated with rhinovirus infection or eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(3):570–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lukkarinen M, Lukkarinen H, Lehtinen P, Vuorinen T, Ruuskanen O, Jartti T. Prednisolone reduces recurrent wheezing after first rhinovirus wheeze: a 7-year follow-up. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24(3):237–243. doi: 10.1111/pai.12046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leino A, Lukkarinen M, Turunen R, Vuorinen T, Soderlund-Venermo M, Vahlberg T, Camargo CA, Jr, Bochkov YA, Gern JE, Jartti T. Pulmonary function and bronchial reactivity 4 years after the first virus-induced wheezing. Allergy. 2019;74(3):518–526. doi: 10.1111/all.13593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simoes EA, Carbonell-Estrany X, Rieger CH, Mitchell I, Fredrick L, Groothuis JR, Palivizumab Long-Term Respiratory Outcomes Study G The effect of respiratory syncytial virus on subsequent recurrent wheezing in atopic and nonatopic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(2):256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jartti T, Lehtinen P, Vuorinen T, Ruuskanen O. Bronchiolitis: age and previous wheezing episodes are linked to viral etiology and atopic characteristics. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(4):311–317. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818ee0c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Teach SJ, Sullivan AF, Forgey T, Clark S, Espinola JA, Camargo CA, Jr, Investigators M Prospective multicenter study of viral etiology and hospital length of stay in children with severe bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(8):700–706. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jartti T, Smits HH, Bonnelykke K, Bircan O, Elenius V, Konradsen JR, Maggina P, Makrinioti H, Stokholm J, Hedlin G, Papadopoulos N, Ruszczynski M, Ryczaj K, Schaub B, Schwarze J, Skevaki C, Stenberg-Hammar K, Feleszko WEAACI Task Force on Preschool Wheeze (2019) Bronchiolitis needs a revisit: distinguishing between virus entities and their treatments. Allergy 74(1):40–52. 10.1111/all.13624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Lee WM, Lemanske RF, Jr, Evans MD, Vang F, Pappas T, Gangnon R, Jackson DJ, Gern JE. Human rhinovirus species and season of infection determine illness severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(9):886–891. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0330OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turunen R, Jartti T, Bochkov YA, Gern JE, Vuorinen T. Rhinovirus species and clinical characteristics in the first wheezing episode in children. J Med Virol. 2016;88(12):2059–2068. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bizzintino J, Lee WM, Laing IA, Vang F, Pappas T, Zhang G, Martin AC, Khoo SK, Cox DW, Geelhoed GC, McMinn PC, Goldblatt J, Gern JE, Le Souef PN. Association between human rhinovirus C and severity of acute asthma in children. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(5):1037–1042. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00092410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jartti T, Gern JE. Rhinovirus-associated wheeze during infancy and asthma development. Curr Respir Med Rev. 2011;7(3):160–166. doi: 10.2174/157339811795589423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonnelykke K, Coleman AT, Evans MD, Thorsen J, Waage J, Vissing NH, Carlsson CJ, Stokholm J, Chawes BL, Jessen LE, Fischer TK, Bochkov YA, Ober C, Lemanske RF, Jr, Jackson DJ, Gern JE, Bisgaard H. Cadherin-related family member 3 genetics and rhinovirus C respiratory illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(5):589–594. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201705-1021OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa K, Jartti T, Bochkov YA, Gern JE, Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Toivonen L, Camargo CA., Jr Rhinovirus species in children with severe bronchiolitis: multicenter cohort studies in the United States and Finland. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(3):e59–e62. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esquivel A, Busse WW, Calatroni A, Togias AG, Grindle KG, Bochkov YA, Gruchalla RS, Kattan M, Kercsmar CM, Khurana Hershey G, Kim H, Lebeau P, Liu AH, Szefler SJ, Teach SJ, West JB, Wildfire J, Pongracic JA, Gern JE. Effects of omalizumab on rhinovirus infections, illnesses, and exacerbations of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(8):985–992. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0120OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasileiou E, Sheikh A, Butler C, El Ferkh K, von Wissmann B, McMenamin J, Ritchie L, Schwarze J, Papadopoulos NG, Johnston SL, Tian L, Simpson CR. Effectiveness of influenza vaccines in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(8):1388–1395. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomsen SF, van der Sluis S, Kyvik KO, Skytthe A, Skadhauge LR, Backer V. Increase in the heritability of asthma from 1994 to 2003 among adolescent twins. Respir Med. 2011;105(8):1147–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pividori M, Schoettler N, Nicolae DL, Ober C, Im HK. Shared and distinct genetic risk factors for childhood-onset and adult-onset asthma: genome-wide and transcriptome-wide studies. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(6):509–522. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30055-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moffatt MF, Kabesch M, Liang L, Dixon AL, Strachan D, Heath S, Depner M, von Berg A, Bufe A, Rietschel E, Heinzmann A, Simma B, Frischer T, Willis-Owen SA, Wong KC, Illig T, Vogelberg C, Weiland SK, von Mutius E, Abecasis GR, Farrall M, Gut IG, Lathrop GM, Cookson WO. Genetic variants regulating ORMDL3 expression contribute to the risk of childhood asthma. Nature. 2007;448(7152):470–473. doi: 10.1038/nature06014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein MM, Thompson EE, Schoettler N, Helling BA, Magnaye KM, Stanhope C, Igartua C, Morin A, Washington C, 3rd, Nicolae D, Bonnelykke K, Ober C. A decade of research on the 17q12-21 asthma locus: piecing together the puzzle. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(3):749–764. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caliskan M, Bochkov YA, Kreiner-Moller E, Bonnelykke K, Stein MM, Du G, Bisgaard H, Jackson DJ, Gern JE, Lemanske RF, Jr, Nicolae DL, Ober C. Rhinovirus wheezing illness and genetic risk of childhood-onset asthma. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(15):1398–1407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loss GJ, Depner M, Hose AJ, Genuneit J, Karvonen AM, Hyvarinen A, Roduit C, Kabesch M, Lauener R, Pfefferle PI, Pekkanen J, Dalphin JC, Riedler J, Braun-Fahrlander C, von Mutius E, Ege MJ, Group PS The early development of wheeze. Environmental determinants and genetic susceptibility at 17q21. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(8):889–897. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1493OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Worgall TS, Veerappan A, Sung B, Kim BI, Weiner E, Bholah R, Silver RB, Jiang XC, Worgall S. Impaired sphingolipid synthesis in the respiratory tract induces airway hyperreactivity. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(186):186ra167. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ha SG, Ge XN, Bahaie NS, Kang BN, Rao A, Rao SP, Sriramarao P. ORMDL3 promotes eosinophil trafficking and activation via regulation of integrins and CD48. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2479. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Willis-Owen SAG, Spiegel S, Lloyd CM, Moffatt MF, Cookson W. The ORMDL3 asthma gene regulates ICAM1 and has multiple effects on cellular inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(4):478–488. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0438OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bønnelykke K, Sleiman P, Nielsen K, Kreiner-Møller E, Mercader JM, Belgrave D, den Dekker HT, Husby A, Sevelsted A, Faura-Tellez G, Mortensen LJ, Paternoster L, Flaaten R, Mølgaard A, Smart DE, Thomsen PF, Rasmussen MA, Bonàs-Guarch S, Holst C, Nohr EA, Yadav R, March ME, Blicher T, Lackie PM, Jaddoe VW, Simpson A, Holloway JW, Duijts L, Custovic A, Davies DE, Torrents D, Gupta R, Hollegaard MV, Hougaard DM, Hakonarson H, Bisgaard H. A genome-wide association study identifies CDHR3 as a susceptibility locus for early childhood asthma with severe exacerbations. Nat Genet. 2014;46(1):51–55. doi: 10.1038/ng.2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bochkov YA, Watters K, Ashraf S, Griggs TF, Devries MK, Jackson DJ, Palmenberg AC, Gern JE. Cadherin-related family member 3, a childhood asthma susceptibility gene product, mediates rhinovirus C binding and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(17):5485–5490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421178112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasanen A, Karjalainen MK, Bont L, Piippo-Savolainen E, Ruotsalainen M, Goksor E, Kumawat K, Hodemaekers H, Nuolivirta K, Jartti T, Wennergren G, Hallman M, Ramet M, Korppi M. Genome-wide association study of polymorphisms predisposing to bronchiolitis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41653. doi: 10.1038/srep41653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu P, Hartert TV. Evidence for a causal relationship between respiratory syncytial virus infection and asthma. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2011;9(9):731–745. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu CJ, Soderhall C, Bustamante M, Baiz N, Gruzieva O, Gehring U, Mason D, Chatzi L, Basterrechea M, Llop S, Torrent M, Forastiere F, Fantini MP, Carlsen KCL, Haahtela T, Morin A, Kerkhof M, Merid SK, van Rijkom B, Jankipersadsing SA, Bonder MJ, Ballereau S, Vermeulen CJ, Aguirre-Gamboa R, de Jongste JC, Smit HA, Kumar A, Pershagen G, Guerra S, Garcia-Aymerich J, Greco D, Reinius L, McEachan RRC, Azad R, Hovland V, Mowinckel P, Alenius H, Fyhrquist N, Lemonnier N, Pellet J, Auffray C, Consortium B, van der Vlies P, van Diemen CC, Li Y, Wijmenga C, Netea MG, Moffatt MF, Cookson W, Anto JM, Bousquet J, Laatikainen T, Laprise C, Carlsen KH, Gori D, Porta D, Iniguez C, Bilbao JR, Kogevinas M, Wright J, Brunekreef B, Kere J, Nawijn MC, Annesi-Maesano I, Sunyer J, Melen E, Koppelman GH. DNA methylation in childhood asthma: an epigenome-wide meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(5):379–388. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forno E, Wang T, Qi C, Yan Q, Xu CJ, Boutaoui N, Han YY, Weeks DE, Jiang Y, Rosser F, Vonk JM, Brouwer S, Acosta-Perez E, Colon-Semidey A, Alvarez M, Canino G, Koppelman GH, Chen W, Celedon JC. DNA methylation in nasal epithelium, atopy, and atopic asthma in children: a genome-wide study. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(4):336–346. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cardenas A, Sordillo JE, Rifas-Shiman SL, Chung W, Liang L, Coull BA, Hivert MF, Lai PS, Forno E, Celedon JC, Litonjua AA, Brennan KJ, DeMeo DL, Baccarelli AA, Oken E, Gold DR. The nasal methylome as a biomarker of asthma and airway inflammation in children. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3095. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11058-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergroth E, Aakula M, Elenius V, Remes S, Piippo-Savolainen E, Korppi M, Piedra PA, Bochkov YA, Gern JE, Camargo CA Jr, Jartti T (2019) Rhinovirus type in severe bronchiolitis and the development of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Jartti T, Kuusipalo H, Vuorinen T, Soderlund-Venermo M, Allander T, Waris M, Hartiala J, Ruuskanen O. Allergic sensitization is associated with rhinovirus-, but not other virus-, induced wheezing in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(7):1008–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baraldo S, Contoli M, Bonato M, Snijders D, Biondini D, Bazzan E, Cosio MG, Barbato A, Papi A, Saetta M. Deficient immune response to viral infections in children predicts later asthma persistence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(5):673–675. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1249LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haahtela T. A biodiversity hypothesis. Allergy. 2019;74(8):1445–1456. doi: 10.1111/all.13763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bisgaard H, Stokholm J, Chawes BL, Vissing NH, Bjarnadottir E, Schoos AM, Wolsk HM, Pedersen TM, Vinding RK, Thorsteinsdottir S, Folsgaard NV, Fink NR, Thorsen J, Pedersen AG, Waage J, Rasmussen MA, Stark KD, Olsen SF, Bonnelykke K. Fish oil-derived fatty acids in pregnancy and wheeze and asthma in offspring. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26):2530–2539. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosendahl J, Valkama S, Holmlund-Suila E, Enlund-Cerullo M, Hauta-Alus H, Helve O, Hytinantti T, Levalahti E, Kajantie E, Viljakainen H, Makitie O, Andersson S. Effect of higher vs standard dosage of vitamin D3 supplementation on bone strength and infection in healthy infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(7):646–654. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bisgaard H, Hermansen MN, Bonnelykke K, Stokholm J, Baty F, Skytt NL, Aniscenko J, Kebadze T, Johnston SL. Association of bacteria and viruses with wheezy episodes in young children: prospective birth cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c4978. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stokholm J, Chawes BL, Vissing NH, Bjarnadottir E, Pedersen TM, Vinding RK, Schoos AM, Wolsk HM, Thorsteinsdottir S, Hallas HW, Arianto L, Schjorring S, Krogfelt KA, Fischer TK, Pipper CB, Bonnelykke K, Bisgaard H. Azithromycin for episodes with asthma-like symptoms in young children aged 1-3 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00500-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bacharier LB, Guilbert TW, Mauger DT, Boehmer S, Beigelman A, Fitzpatrick AM, Jackson DJ, Baxi SN, Benson M, Burnham CD, Cabana M, Castro M, Chmiel JF, Covar R, Daines M, Gaffin JM, Gentile DA, Holguin F, Israel E, Kelly HW, Lazarus SC, Lemanske RF, Jr, Ly N, Meade K, Morgan W, Moy J, Olin T, Peters SP, Phipatanakul W, Pongracic JA, Raissy HH, Ross K, Sheehan WJ, Sorkness C, Szefler SJ, Teague WG, Thyne S, Martinez FD. Early administration of azithromycin and prevention of severe lower respiratory tract illnesses in preschool children with a history of such illnesses: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(19):2034–2044. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bisgaard H, Hermansen MN, Buchvald F, Loland L, Halkjaer LB, Bonnelykke K, Brasholt M, Heltberg A, Vissing NH, Thorsen SV, Stage M, Pipper CB. Childhood asthma after bacterial colonization of the airway in neonates. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(15):1487–1495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujimura KE, Demoor T, Rauch M, Faruqi AA, Jang S, Johnson CC, Boushey HA, Zoratti E, Ownby D, Lukacs NW, Lynch SV. House dust exposure mediates gut microbiome Lactobacillus enrichment and airway immune defense against allergens and virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(2):805–810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310750111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kloepfer KM, Lee WM, Pappas TE, Kang TJ, Vrtis RF, Evans MD, Gangnon RE, Bochkov YA, Jackson DJ, Lemanske RF, Jr, Gern JE. Detection of pathogenic bacteria during rhinovirus infection is associated with increased respiratory symptoms and asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1301–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ampofo K, Bender J, Sheng X, Korgenski K, Daly J, Pavia AT, Byington CL. Seasonal invasive pneumococcal disease in children: role of preceding respiratory viral infection. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):229–237. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Madhi SA, Klugman KP, Vaccine Trialist G. A role for Streptococcus pneumoniae in virus-associated pneumonia. Nat Med. 2004;10(8):811–813. doi: 10.1038/nm1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Steenhuijsen Piters WA, Heinonen S, Hasrat R, Bunsow E, Smith B, Suarez-Arrabal MC, Chaussabel D, Cohen DM, Sanders EA, Ramilo O, Bogaert D, Mejias A. Nasopharyngeal microbiota, host transcriptome, and disease severity in children with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(9):1104–1115. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0220OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teo SM, Mok D, Pham K, Kusel M, Serralha M, Troy N, Holt BJ, Hales BJ, Walker ML, Hollams E, Bochkov YA, Grindle K, Johnston SL, Gern JE, Sly PD, Holt PG, Holt KE, Inouye M. The infant nasopharyngeal microbiome impacts severity of lower respiratory infection and risk of asthma development. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(5):704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuruvilla ME, Lee FE, Lee GB. Understanding asthma phenotypes, endotypes, and mechanisms of disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56(2):219–233. doi: 10.1007/s12016-018-8712-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fahy JV. Type 2 inflammation in asthma--present in most, absent in many. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(1):57–65. doi: 10.1038/nri3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voehringer D, Reese TA, Huang X, Shinkai K, Locksley RM. Type 2 immunity is controlled by IL-4/IL-13 expression in hematopoietic non-eosinophil cells of the innate immune system. J Exp Med. 2006;203(6):1435–1446. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Locksley RM. Asthma and allergic inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lukkarinen M, Koistinen A, Turunen R, Lehtinen P, Vuorinen T, Jartti T. Rhinovirus-induced first wheezing episode predicts atopic but not nonatopic asthma at school age. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(4):988–995. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.12.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bochkov YA, Gern JE. Rhinoviruses and their receptors: implications for allergic disease. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16(4):30. doi: 10.1007/s11882-016-0608-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakagome K, Bochkov YA, Ashraf S, Brockman-Schneider RA, Evans MD, Pasic TR, Gern JE. Effects of rhinovirus species on viral replication and cytokine production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(2):332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jackson DJ, Makrinioti H, Rana BM, Shamji BW, Trujillo-Torralbo MB, Footitt J, Del-Rosario J, Telcian AG, Nikonova A, Zhu J, Aniscenko J, Gogsadze L, Bakhsoliani E, Traub S, Dhariwal J, Porter J, Hunt D, Hunt T, Stanciu LA, Khaitov M, Bartlett NW, Edwards MR, Kon OM, Mallia P, Papadopoulos NG, Akdis CA, Westwick J, Edwards MJ, Cousins DJ, Walton RP, Johnston SL. IL-33-dependent type 2 inflammation during rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(12):1373–1382. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beale J, Jayaraman A, Jackson DJ, Macintyre JDR, Edwards MR, Walton RP, Zhu J, Man Ching Y, Shamji B, Edwards M, Westwick J, Cousins DJ, Yi Hwang Y, McKenzie A, Johnston SL, Bartlett NW. Rhinovirus-induced IL-25 in asthma exacerbation drives type 2 immunity and allergic pulmonary inflammation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(256):256ra134. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saglani S, Lui S, Ullmann N, Campbell GA, Sherburn RT, Mathie SA, Denney L, Bossley CJ, Oates T, Walker SA, Bush A, Lloyd CM. IL-33 promotes airway remodeling in pediatric patients with severe steroid-resistant asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(3):676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Durrani SR, Montville DJ, Pratt AS, Sahu S, DeVries MK, Rajamanickam V, Gangnon RE, Gill MA, Gern JE, Lemanske RF, Jackson DJ. Innate immune responses to rhinovirus are reduced by the high-affinity IgE receptor in allergic asthmatic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(2):489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Edwards MR, Walton RP, Jackson DJ, Feleszko W, Skevaki C, Jartti T, Makrinoti H, Nikonova A, Shilovskiy IP, Schwarze J, Johnston SL, Khaitov MR, Asthma EA-ii. Asthma Exacerbations Task F The potential of anti-infectives and immunomodulators as therapies for asthma and asthma exacerbations. Allergy. 2018;73(1):50–63. doi: 10.1111/all.13257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stepanova E, Isakova-Sivak I, Rudenko L (2019) Overview of human rhinovirus immunogenic epitopes for rational vaccine design. Expert Rev Vaccines. 10.1080/14760584.2019.1657014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Simoes EAF, Bont L, Manzoni P, Fauroux B, Paes B, Figueras-Aloy J, Checchia PA, Carbonell-Estrany X. Past, present and future approaches to the prevention and treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. Infect Dis Ther. 2018;7(1):87–120. doi: 10.1007/s40121-018-0188-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Brien KL, Chandran A, Weatherholtz R, Jafri HS, Griffin MP, Bellamy T, Millar EV, Jensen KM, Harris BS, Reid R, Moulton LH, Losonsky GA, Karron RA, Santosham M, Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prevention study g Efficacy of motavizumab for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease in healthy Native American infants: a phase 3 randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(12):1398–1408. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bakel LA, Hamid J, Ewusie J, Liu K, Mussa J, Straus S, Parkin P, Cohen E (2017) International variation in asthma and bronchiolitis guidelines. Pediatrics 140(5). 10.1542/peds.2017-0092 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Jackson DJ, Johnston SL. The role of viruses in acute exacerbations of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1178–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jartti T, Nieminen R, Vuorinen T, Lehtinen P, Vahlberg T, Gern J, Camargo CA, Jr, Ruuskanen O. Short- and long-term efficacy of prednisolone for first acute rhinovirus-induced wheezing episode. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(3):691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koistinen A, Lukkarinen M, Turunen R, Vuorinen T, Vahlberg T, Camargo CA, Jr, Gern J, Ruuskanen O, Jartti T. Prednisolone for the first rhinovirus-induced wheezing and 4-year asthma risk: a randomized trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28(6):557–563. doi: 10.1111/pai.12749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mochizuki H, Kusuda S, Okada K, Yoshihara S, Furuya H, Simoes EAF, Scientific Committee for Elucidation of Infantile A Palivizumab prophylaxis in preterm infants and subsequent recurrent wheezing. Six-year follow-up study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(1):29–38. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201609-1812OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scheltema NM, Nibbelke EE, Pouw J, Blanken MO, Rovers MM, Naaktgeboren CA, Mazur NI, Wildenbeest JG, van der Ent CK, Bont LJ. Respiratory syncytial virus prevention and asthma in healthy preterm infants: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(4):257–264. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(18)30055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, Evans MD, Roberg KA, Anderson EL, Pappas TE, Printz MC, Lee WM, Shult PA, Reisdorf E, Carlson-Dakes KT, Salazar LP, DaSilva DF, Tisler CJ, Gern JE, Lemanske RF., Jr Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in early life predict asthma development in high-risk children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(7):667–672. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mansbach JM, Clark S, Teach SJ, Gern JE, Piedra PA, Sullivan AF, Espinola JA, Camargo CA., Jr Children hospitalized with rhinovirus bronchiolitis have asthma-like characteristics. J Pediatr. 2016;172:202–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johnston NW, Johnston SL, Duncan JM, Greene JM, Kebadze T, Keith PK, Roy M, Waserman S, Sears MR. The September epidemic of asthma exacerbations in children: a search for etiology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(1):132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Falsey AR. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. Exp Lung Res. 2005;31(Suppl 1):77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Georas SN, Rezaee F. Epithelial barrier function: at the front line of asthma immunology and allergic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(3):509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Basnet S, Palmenberg AC, Gern JE. Rhinoviruses and their receptors. Chest. 2019;155(5):1018–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Johnson SM, McNally BA, Ioannidis I, Flano E, Teng MN, Oomens AG, Walsh EE, Peeples ME. Respiratory syncytial virus uses CX3CR1 as a receptor on primary human airway epithelial cultures. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(12):e1005318. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wark PA, Johnston SL, Bucchieri F, Powell R, Puddicombe S, Laza-Stanca V, Holgate ST, Davies DE. Asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells have a deficient innate immune response to infection with rhinovirus. J Exp Med. 2005;201(6):937–947. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Busse WW, Morgan WJ, Gergen PJ, Mitchell HE, Gern JE, Liu AH, Gruchalla RS, Kattan M, Teach SJ, Pongracic JA, Chmiel JF, Steinbach SF, Calatroni A, Togias A, Thompson KM, Szefler SJ, Sorkness CA. Randomized trial of omalizumab (anti-IgE) for asthma in inner-city children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11):1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim CK, Callaway Z, Gern JE. Viral infections and associated factors that promote acute exacerbations of asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2018;10(1):12–17. doi: 10.4168/aair.2018.10.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Merckx J, Ducharme FM, Martineau C, Zemek R, Gravel J, Chalut D, Poonai N, Quach CJP. Respiratory viruses and treatment failure in children with asthma exacerbation. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20174105. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, Bousquet J, Drazen JM, Fitzgerald JM, Gibson P, Ohta K, O'Byrne P, Pedersen SE, Pizzichini E, Sullivan SD, Wenzel SE, Zar HJ. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:143–178. doi: 10.1183/13993003.51387-2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Teach SJ, Gergen PJ, Szefler SJ, Mitchell HE, Calatroni A, Wildfire J, Bloomberg GR, Kercsmar CM, Liu AH, Makhija MM, Matsui E, Morgan W, O'Connor G, Busse WW. Seasonal risk factors for asthma exacerbations among inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(6):1465–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Colin AA, Rossi GA, Feleszko W. Immunomodulation in children with recurrent wheeze: present knowledge and future perspective. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54(Suppl 1):S149–S151. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Namazova-Baranova LS, Alekseeva AA, Kharit SM, Kozhevnikova TN, Taranushenko TE, Tuzankina IA, Scarci F. Efficacy and safety of pidotimod in the prevention of recurrent respiratory infections in children: a multicentre study. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2014;27(3):413–419. doi: 10.1177/039463201402700311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zolkiewicz J, Strzelec K, Ruszczynski M, Feleszko W (2019) Orally administered immunostimulant as a prevention of asthma exacerbation and wheezing in children-a systematic review. (Abstract EAACI Congress). In: ALLERGY, 2019., pp 786–787