Abstract

The tripartite-motif protein, TRIM5α, is an innate immune sensor that potently restricts retrovirus infection by binding to human immunodeficiency virus capsids. Higher-ordered oligomerization of this protein forms hexagonally patterned structures that wrap around the viral capsid, despite an anomalously low affinity for the capsid protein (CA). Several studies suggest TRIM5α oligomerizes into a lattice with a symmetry and spacing that matches the underlying capsid, to compensate for the weak affinity, yet little is known about how these lattices form. Using a combination of computational simulations and electron cryo-tomography imaging, we reveal the dynamical mechanisms by which these lattices self-assemble. Constrained diffusion allows the lattice to reorganize, whereas defects form on highly curved capsid surfaces to alleviate strain and lattice symmetry mismatches. Statistical analysis localizes the TRIM5α binding interface at or near the CypA binding loop of CA. These simulations elucidate the molecular-scale mechanisms of viral capsid cellular compartmentalization by TRIM5α.

Subject terms: Computational biophysics, Computational chemistry, Molecular dynamics, Statistical mechanics

Tripartite-motif containing (TRIM) proteins modulate cellular responses to viral infection. Here the authors use molecular dynamics simulations to demonstrate that TRIM5α uses a two-dimensional lattice hopping mechanism to aggregate on the HIV capsid surface and initiate lattice growth.

Introduction

Tripartite motif containing proteins (TRIMs) are a large family of proteins that play central roles in host cellular responses to viral infection1–4. TRIMs have been implicated in diverse biological processes, including autophagy, cell differentiation, apoptosis, and intracellular signaling5–8. Several TRIM proteins directly restrict viral activity by interfering with distinct steps in the viral life cycle, while others regulate signal transduction pathways induced by innate immune sensors. TRIM5α and TRIMCyp, in particular, have been found to be responsible for the species-specific resistance to infection by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in rhesus macaques9 and owl monkeys10, respectively.

TRIM5α proteins are cytoplasmic proteins that bind to the retroviral capsid of HIV-1 and promote signaling pathways that alert the innate immune system to invasion11,12, causing the premature dissociation of the capsid and inhibiting reverse transcription13–15. Higher-ordered oligomers of TRIM5α spontaneously assemble into hexagonally patterned structures on the surface of the capsid, which are detectable under negative-stained electron microscopy16,17. Like all tripartite motif containing proteins, TRIM5α consists of three distinct domains – a RING domain, B-box domain, and coiled-coil domain (i.e., RBCC or tripartite motif). At low concentrations in solution, TRIM5α proteins primarily form dimeric complexes, mediated by interactions between two antiparallel α-helices that comprise the coiled-coil domain. The B-box domain caps the N-terminal end of each α-helix and mediates interactions between TRIM5α dimers. B-box domains interact with the B-box domains of other TRIM5α dimers in a layered fashion with electrostatic interactions sandwiching a hydrophobic core to produce a three-fold symmetric trimer-of-dimers structure18. In addition, TRIM5α contains a C-terminal SPRY domain, connected to the center of the coiled-coil domain by the L1 helix and a flexible linker region, that has a very weak affinity for the capsid protein (CA) (estimated KD > 1 mM)13,19–21.

Given the low affinity of individual TRIM5α monomers for the capsid, how does TRIM5α effectively encage the viral capsid? Dimerization enhances TRIM5α binding in vitro, and several studies, including ours, have suggested that the weak interactions are amplified by avidity effects resulting from higher-ordered oligomerization, which positions the SPRY domains to interact with repeating structural elements on the capsid surface22,23; although none have explored the dynamics of how this might occur. In this work, we investigate the self-assembly mechanisms of TRIM5α on the HIV-1 retroviral capsid, using a combined coarse-grained (CG) molecular simulation, cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) imaging, and computational analysis approach.

Results

CG model development for TRIM5α and CA

Mature HIV-1 capsid structures are large protein assemblies consisting of ~1500 individual CA domains arranged in a fullerene cone around the viral RNA, reverse transcriptase, and other enzymes that facilitate the replication of the virus. At least two hundred TRIM5α monomers are required to form an encaging hexagonal lattice around the core of the virus that blocks HIV infection in a slow dynamical process that takes place on the order of minutes24 and is currently not amenable to analysis by all-atom molecular dynamics simulations.

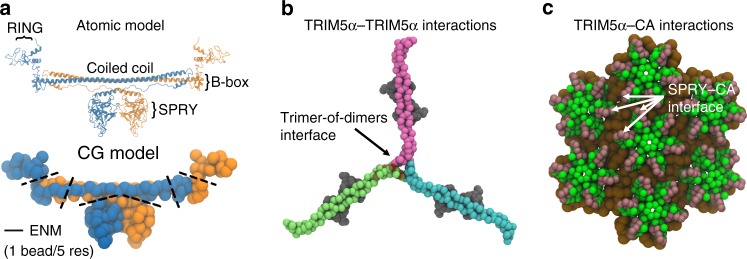

To surmount the computational cost associated with simulations at an atomic level of detail, we developed a CG model for TRIM5α self-assembly on viral capsids, using methods established in prior studies25–28. An atomic model for TRIM5α was first constructed from crystallographic fragments available in the Protein Data Bank, and subsequently coarse-grained at a resolution of 1 CG particle per 5 amino acid residues (Fig. 1a). Elastic network models (ENM) were used at the interfaces of specific domains – SPRY–coiled coil, B-box–coiled-coil, and RING–B-box domains – to confer protein flexibility (Supplementary Fig. 1). At a minimum, two intermolecular driving forces are necessary for TRIM5α assembly on capsids: interactions between the dimers that mediate the higher-ordered assembly of the lattice (Fig. 1b), and interactions between dimers and CA that regulate the binding to the capsid surface (Fig. 1c). Attractive interactions between B-box domain residues were added to promote the formation of the crystallographically resolved trimer-of-dimer structures. Attractive interactions were added between SPRY and CA domain residues that demonstrated decreased or abolished TRIM5α binding in experimental mutagenesis studies21,29. (For a complete description on the models, see also Materials & Methods).

Fig. 1. Minimal interactions for capsid-induced TRIM5α self-assembly.

a Atomic and CG representations of the TRIM5α dimer. Each monomer subunit is colored in orange and blue, respectively. Labels indicate distinct structural domains (Top). Dashed lines highlight locations of elastic network models used to confer flexibility to the dimer in the CG model (Bottom). b A snapshot of a higher-ordered TRIM5α trimer-of-dimers structure assembled during our simulations. Dark red spheres depict the locations of virtual sites for the central TRIM5α dimer (pink), which act as tethering sites for the adjacent TRIM5α dimer (lime). c CG representation of the capsid surface. The N-terminal domain is colored in green, whereas the C-terminal region is colored in brown. Dark pink spheres reflect sites of attractive interactions with the SPRY domain.

Molecular mechanisms of TRIM5α self-assembly

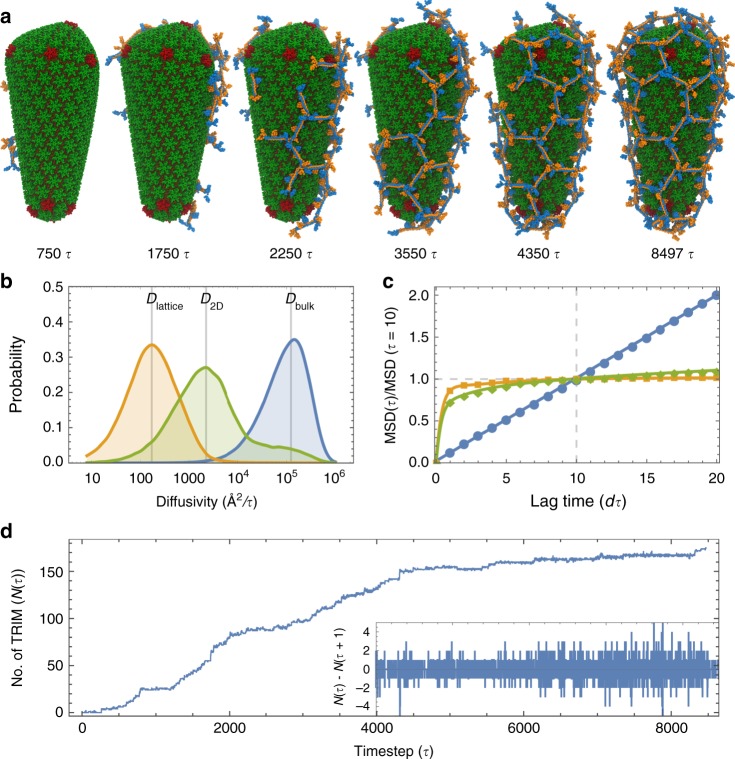

TRIM5α has an intrinsic propensity to form hexagonal protein assemblies at high concentrations. Negative-stain electron microscopy experiments have demonstrated that purified TRIM5α spontaneously assembles into two-dimensional arrays composed primarily of hexagonal rings16. To gain insight into the self-assembly mechanisms of TRIM5α, we performed CG molecular dynamics simulations of TRIM5α in the presence of conical capsids derived from cryo-ET data on intact virions30. Snapshots of the assembly process taken at various stages of lattice formation are shown in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Movie 1.

Fig. 2. Coupled TRIM5α self-assembly and capsid binding.

a The assembly process of TRIM5α shows how TRIM5α encages the viral capsid. Time points (τ) are given relative to the start of the simulation. b Normalized distribution of diffusivity values for TRIM5α dimers in bulk solvent (blue; Dbulk = 123,315 Å2/τ), TRIM5α dimers bound to the capsid surface (green; D2D = 2224 Å2/τ), and TRIM5α lattices bound to the capsid (orange; Dlattice = 174 Å2/τ). c Mean-squared displacements (MSD) of the TRIM5α subunits as a function of the lag time in units of τ. The MSD(t) values were normalized by the MSD (t = 10τ). Line colors correspond to the populations denoted in b. d Growth in the number of TRIM5α subunits that form lattice contacts with other TRIM5α, on the capsid surface, N(τ), as a function of time, τ. Inset shows the finite difference of N(τ) for t = 4000–8000τ. Positive values indicate that lattice contacts form, whereas negative values indicate that lattice contacts break. Note that all units of time are given in τ = 250,000 CG simulation time steps.

In the simulations, TRIM5α dimers rapidly bind to and dissociate from the capsid. While the dimers are bound, they diffuse two-dimensionally across the capsid surface and contact other bound dimers at the B-box interface to form a central trimer-of-dimers structure. Formation of the trimer-of-dimer structure nucleates the growth of an initially hexameric lattice (t = 0–1483τ). Surprisingly, non-hexagonal defects also form in the TRIM5α lattice at regions of high CA curvature. Pentameric defects form primarily along the broad end of the conical capsid (t = 1699τ); a tetrameric defect forms at the narrow end of the capsid (t = 4297τ); and a heptameric defect forms at the base of the broad end, adjacent to three pentameric defects (t = 4501τ). Alternating pentamer–heptamer defect motifs lower the energetic strain of defect incorporation in the lattice.

Large-scale reorganization of the lattice occurs as the entire lattice shifts to accommodate the addition of TRIM5α onto the growing lattice (t = 1219τ, 4171τ, 5125τ). Intermediate defect structures that are less stable at particular positions on the lattice, break and reform into more stable oligomers. A metastable pentamer later converts into a hexamer (t = 1219τ), and an initially tetrameric oligomer in the lattice converts into a pentamer (t = 5125τ). The resulting lattice consists of 16 hexamers, 12 pentamers, 2 heptamers, and 1 tetramer, and has an Euler’s characteristic that is the same as that of enclosed fullerene structures (χTRIM = 2).

Closer inspection of the association and dissociation of TRIM5α with the capsid surface (Supplementary Movie 2) revealed that the dimers diffuse across the surface by “hopping” across metastable SPRY–CA domain interaction hotspots. There are two SPRY domains per dimer, and as contact between one of the SPRY domains and the capsid breaks, the dimer can rotate about the anchoring SPRY domain before binding at another SPRY–CA interaction hotspot, allowing for diffusive movement that resembles non-directional step-by-step “walking”. To quantify this 2D diffusive behavior, we measured the diffusivities for three distinct subpopulations of TRIM5α throughout the assembly process: (1) dimers in bulk solvent (Dbulk), (2) dimers that bound and did not contact any other dimers (D2D) and (3) dimers that bound and made lattice contacts with other TRIM5α associated to the capsid (Dlattice). The peaks of the diffusivity distributions yield the diffusion coefficients, which follow the expected trend: Dlattice < D2D < Dbulk (Fig. 2b).

The mean-squared displacements (MSDs) calculated for dimers in bulk solvent correlated linearly with the lag time, consistent with the mobility of freely diffusing particles (Fig. 2c). Dimers bound to the capsid however, had MSDs that plateaued to a constant value, characteristic of constrained diffusion, with dimers that formed TRIM5α lattice network contacts plateauing faster than dimers that did not (decay rate: λlattice = 2.23; λ2D = 1.16). The converged MSDs, indicative of the size of the constraining region (s), also suggested that lattice oligomers diffusing on the capsid surface were more highly constrained than individual dimers (slattice = 203 Å2; s2D = 3,297 Å2).

Growth of the encaging TRIM5α lattice can be characterized as a stochastic process in which the continual formation and breakage of contacts between dimers in the lattice is necessary to drive the process towards hexagonal assembly. We tracked how the number of lattice-forming monomers, N(τ), varied with respect to the simulation time (Fig. 2d). The concentration of free TRIM5α in solution provides the chemical driving force for the assembly process, and was at the start of the simulation initially set to 3.2 μM, consistent with the TRIM5α concentration used in in vitro cryo-EM experiments17. As assembly proceeds, the rate of lattice growth slows, most apparently from t = 5000–8471τ, in part as a result of the drop in the concentration of free TRIM5α in the simulation system, and the decrease in available capsid surface area that is unoccupied by TRIM5α. Intriguingly, the growth of the lattice is interspersed with periods of rapid growth and stalled intermediates, most notably at t = 913–1219τ, 1699τ, and 4171τ. As discussed earlier in this section, the time points t = 1219τ and 4171τ involve lattice reorganization events that precede continued growth, and t = 1699τ involves the formation of pentameric defects at the broad end of the capsid that stabilizes the curved end of the TRIM5α lattice. The finite difference of N(τ), in which negative values correspond to the number of TRIM5α contacts formed and positive values correspond to the number of TRIM5α contacts broken at each timestep, τ, indicates that on average two TRIM5α contacts in the lattice are formed or broken at each timestep. These results suggest that the coexistence of assembly and disassembly of the lattice as it grows and wraps around the capsid, or dynamic instability, is essential to the encaging process.

Competing protein interactions determine assembly behavior

The strength of the molecular interactions between TRIM5α dimers (TRIM5α–TRIM5α; εP) and between TRIM5α dimers and the capsid (TRIM5α–CA; εC) compete to determine the overall assembly behavior. We performed multiple CG simulations, in which the attractive interactions at the B–box domain interface were varied from εP = 0.5–1.2 kcal/mol and attractive interactions between the SPRY and CA domains were varied from εC = 0.3–1.0 kcal/mol. Endpoints of the simulations (Fig. 3) show markedly different assembly behavior as a consequence of the relative strengths of the TRIM5α–TRIM5α and TRIM5α–CA interactions.

Fig. 3. A thermodynamic cycle depicts the phase behavior of TRIM5α lattice assembly.

εP and εC are parameters that tune the strengths of interactions between the protein–protein (TRIM5α–TRIM5α) contacts of TRIM5α and the protein–capsid (TRIM5α–CA) contacts, respectively, in the potential energy. Panels are CG assembly simulations that proceeded to completion (~10,000 τ) for: εP = 0.5, εC = 0.3 kcal/mol (Bottom Left); εP = 1.2, εC = 0.3 kcal/mol (Top Left); εP = 1.2, εC = 1.0 kcal/mol (Top Right); εP = 1.2, εC = 0.3 kcal/mol (Bottom Right) and εP = 0.7, εC = 0.35 kcal/mol (Center). Hexagonal assembly of TRIM5α is critically balanced between εP and εC.

When both interaction strengths are below a critical value (εP = 0.5 kcal/mol; εC = 0.3 kcal/mol), TRIM5α dimers are diffusive in solution and neither self-assemble nor bind to the capsid. At low TRIM5α–TRIM5α and high TRIM5α–CA interaction strengths, the dimers bind to the capsid, but do not interact with one another on the capsid surface, and global hexagonal lattice formation is not present. When both interactions are too strong (εP = 1.2 kcal/mol; εC = 1.0 kcal/mol), the dimers bind and form assemblies that grow and protrude from the capsid. At high TRIM5α–TRIM5α and low TRIM5α–CA interaction strengths, the dimers aggregate into large assemblies in solution that grow until the free dimer concentration in solution is exhausted, and do not encase the capsid.

Hexagonal assembly of the TRIM5α lattice on the capsid is only present over a narrow range of interaction strengths (εP = 0.6–0.7; εC = 0.35–0.4 kcal/mol) and sensitive to small perturbations in the interaction energetics. Relatively weak interactions between the SPRY domain and capsid are required for the growing lattice to reorganize and for TRIM5α dimers to diffuse on the capsid; otherwise lattice configurations become kinetically trapped in states where bound dimers do not interact with other neighboring dimers (Fig. 3; Top Left panel). Weak interactions between dimers are also required to prevent the rapid growth of TRIM5α aggregates in solution and allow defects to adopt more stable hexagonal configurations (Fig. 3; Bottom Right panel). Interaction ranges that facilitated hexagonal assembly on the lattice had stronger interactions between the dimers than between the SPRY and CA domains. Notably, TRIM5α dimers do not self-assemble in bulk solution for these interaction strengths (e.g. see Supplementary Fig. 2, εP = 0.7; εC = 0 kcal/mol), indicating that nucleation on the capsid surface, mediated by SPRY–CA domain interactions, is required to trigger lattice assembly at these concentrations. Hexagonal assembly of the lattice thus appears to be tuned between these two competing factors.

Non-hexagonal defects form in TRIM5α lattices

The simulations show that non-hexagonal defects can form in TRIM5α lattices to alleviate strain induced by curvature of the capsid. For viral HIV-1 CA protein, exactly 12 pentameric defects are required to form enclosed capsid cores, consistent with those seen in ideal fullerene structures31,32. In vitro experiments have also demonstrated that CA can form helical tubes without defects33–35, since hexagonal lattices have an Euler’s characteristic (χHex = 0), which matches the topological structure of cylindrical tubes.

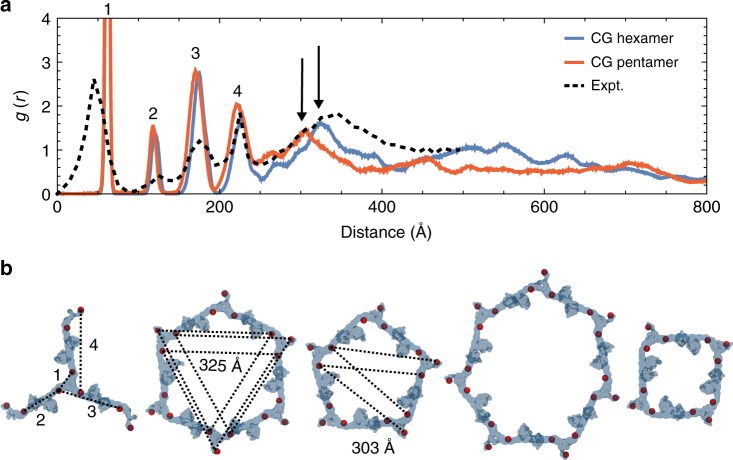

We initially hypothesized that TRIM5α lattices would also form purely hexagonal lattices on CA tubes. We expressed and purified TRIM5α and HIV-1 CA proteins and then co-incubated them at low ionic strength conditions to produce CA tubes that were extensively bound with TRIM5α17,18, which were subsequently imaged by electron cryotomography. We then performed sub-tomogram analysis on a single tube, focusing on each of the repeating units (HIV-1 CA hexamer, TRIM5a dimer, and TRIM5a trimer), which yielded 20–30 Å reconstructions. Mapping back these averages to the original tomogram, using Euler angles and positions derived from sub-tomogram averaging36, allowed us to visualize the relative arrangements of the repeating units37. This analysis showed that the tube was composed of an inner array of CA hexamers surrounded by ring-like decorations formed by TRIM5α (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4. TRIM5α assembles into hexagonal lattices on capsid tubes.

a Simulation endpoint for the TRIM5α assembly process on a cylindrical surface. b Electron cryotomography (cryo-ET) reveals that TRIM5α forms hexagonal lattices on the surface of CA tubes.

To our surprise, the experimental TRIM5α lattice map contained multiple defects including pentameric and heptameric TRIM5α rings. The defects formed seam-like regions, or grain boundaries, along the tube, and clustered to form alternating pentamer and heptameric defect motifs (see Supplementary Fig. 3). A segment of the helical CA tube was extracted from the lattice map, which was then simulated with TRIM5α added in bulk solvent. The CG simulations resulted in both defect-free TRIM5α lattices (Fig. 4a), and lattices that contained pentameric and heptameric defects. Defect formation depended highly on the growth of the TRIM5α lattice. Symmetry mismatches between the TRIM5α lattice and the underlying CA lattice also cause defect incorporation. Defects are inherently less stable compared to regular hexagonal states, and the presence of these defects indicate that they were kinetically trapped during lattice growth. Qualitatively, the hexagonal regions of the TRIM5α lattices directly imaged by cryo-ET and predicted from our CG simulations were in good agreement (Fig. 4).

To quantitatively compare the hexagonal lattice structure and defect structures predicted from our CG simulations (Fig. 5b) to that derived from cryo-ET, we computed pair correlation functions, g(r), (Fig. 5a) with respect to the center-of-geometry of B-box domain residues. The g(r) measures how the density of particles varies as a function of distance, and peaks at regular spacings in structures with symmetry. Peak 1 corresponds to the trimer-of-dimers interface, which is smaller in the cryo-ET lattice (~43 Å) than that of the simulated lattices (~63 Å), indicating that the interface may be more compact than predicted by our simulations. The positions of peaks 2–4 agree between the experimental and simulated lattices; there are slight differences between the hexameric and pentameric lattices, which may reflect distortions in the trimer-of-dimers, as they adopt angular distributions of 120° and 108°, respectively. Hexameric lattices contain a peak at 325 Å that is downshifted to 303 Å in pentameric lattices, which corresponds to the smaller size of the pentamers. The experimental cryo-ET lattice is peaked at both 303 Å and 325 Å, since it contains both hexamers and pentamers. The pair correlation functions were not calculated for heptameric nor tetrameric defects, since only one or two of each formed in each CG trajectory, which did not allow for enough statistics to converge the g(r). Tetrameric structures occupied regions of high CA curvature like that of the narrow end of the capsid, and were the most energetically unstable during simulation. Tetrameric defects were not detected in cryo-ET images of TRIM5α associated CA tubules, which are less curved than capsids. In a prior study, cryo-ET imaging of TRIM5α associated with capsids stabilized by disulfide-crosslinks reveals the presence of defects that resemble tetramers; although the resolution is too poor for conclusive validation17. We speculate that the tetrameric defects observed in the simulations are transient metastable states. The computationally predicted pentameric and heptameric structures, are in good agreement with the cryo-ET experiments. Importantly, our CG simulations independently predicted the existence of pentameric and heptameric defects prior to experimental validation.

Fig. 5. Non-hexagonal defect structures of TRIM5α lattices.

a Pair correlation functions, g(r), between the virtual sites’ center-of-geometry as a function of the radial distance (Å), calculated for TRIM5α subunits that form hexagonal ordered lattices (blue) and pentagonal ordered lattices (red) on the capsid. The black dashed lines indicate the g(r) calculated from models derived from experimental cryo-ET densities (see Fig. 4). Peaks 1–4 are labeled. Arrows indicate close-range differences in the lattice spacing peaks between hexagonal and pentagonal lattices. b Higher-ordered TRIM5α structures that spontaneously assemble on the capsid during simulation. TRIM5α subunits are colored in transparent blue, and the center-of-geometry for the virtual sites is depicted as red spheres. Dotted lines indicate intermolecular distances that form peaks in the pair correlation function, g(r). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

SPRY–CA binding interface

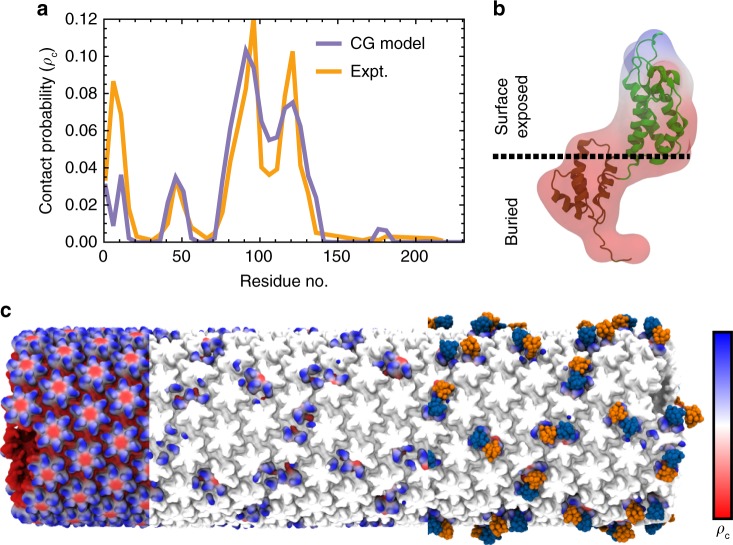

The SPRY domain affinity to CA is so weak that it is difficult to measure experimentally (estimated KD > 1 mM)13,19–21, and thus far has proven refractory to crystallization. TRIMCyp is a related RBCC protein found in owl monkeys that contains Cyclophilin A (CypA) in place of the SPRY domain and also blocks HIV-1 infection. CypA has a much higher affinity for the CA protein (KD ~ 10 μM)38–40, and the high-resolution crystallographic structure of CypA in complex with CA reveals that it binds to a flexible loop region that connects helices 4 and 5 (resid 80–100)41. Given the weak affinity between the SPRY and CA domains and the lack of available structural data, several studies have attempted to model the SPRY binding interface either using computational methods42,43 or experimental mutagenesis29,44. Our CG simulations provide an alternative approach.

To locate the SPRY–CA binding interface, we calculated a residue-specific contact probability map for the CA domain. During the assembly simulations, CA residues within 20 Å of the SPRY domains were tabulated and used to compute a 1D probability distribution for contact. The same calculation was also performed using a TRIM5α and CA model fit to the experimental cryo-ET densities (Fig. 6a). The simulated and experimental contact probabilities agree well; although the experimental probability distribution has sharper peaks, in part because it was calculated from a single cryo-ET structure. Both probability distributions indicate the highest occupancy for SPRY in the CypA binding region and the adjacent loop region between helices 6 and 7 (resid 115–130). Lower contact probabilities were found for the β-hairpin region at the entrance to the central pore of the helix (resid 1–15), recently hypothesized to change conformation in response to protonation45, and a more buried loop region between helices 2 and 3 (resid 40–50). The elevated contact probabilities in these regions may be attributed to steric contact, once the variable loops of the SPRY domain contact the CypA binding region; note that the cryo–ET structure has a higher occupancy for the β-hairpin region than that of the computational results, indicating the SPRY domain may have a slight attractive interaction in that region, which was not captured in our CG simulations. Interestingly, the contact probabilities for CA residues matches well with those derived from the experimental densities for both residues that had attractive interactions with the SPRY domain (resid 83–132) and residues that did not, likely as a combination of sterics, excluded volume, sites that facilitated TRIM5α lattice contacts, and the attractive TRIM5α–CA potential. Overall, however, the agreement between the simulated and experimental contact probabilities further validates our CG simulations.

Fig. 6. The SPRY domain binding interface.

a Probability for residues on the CA domain to form contacts with TRIM5α calculated from both simulation (CG) and experimental cryo-ET density maps (Expt). b The simulated contact probability is shown in a 3D map overlaid with the atomic structure of the CA domain and colored by regions from highest contact probability (blue) to lowest contact probability (red). c The CG structure of the CA tubule with highest contact probability (pc = 0.10) in blue and regions of lowest probability colored in red (pc = 0.0) sub-divided in three sections. The leftmost section shows the contact probability across the tubule; the middle section shows the probability at positions for which the SPRY domain bound during a CG assembly simulation; the rightmost section shows the binding positions of the SPRY domains. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The contact probabilities were mapped back onto volumetric surfaces for CA (Fig. 6b, c). Highlighting the surfaces on the CA tube in which the SPRY domain appeared bound during assembly (Fig. 6c) reveals that TRIM5α binds to substantially varied interfaces on the capsid surface, including along two-fold, three-fold symmetry axes between hexamers29, and above the NTD of the CA domain. Our results suggest TRIM5α binds primarily at or near the CypA binding loop of HIV-1 CA, which is consistent with recent nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy results that demonstrate differences in the chemical shifts of residues in this region upon SPRY binding46.

TRIM5α binds to multiple capsid morphologies

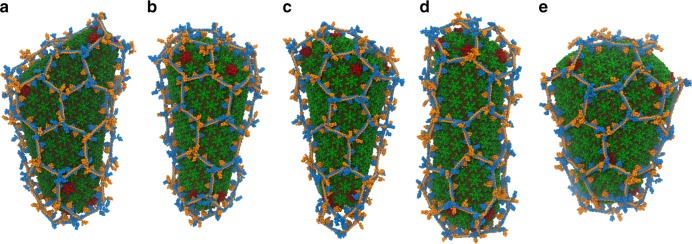

HIV capsids are pleomorphic structures that adopt several distinct morphologies to package viral RNA30,47. It is possible that TRIM5α forms either incomplete lattices or lattices that contain differing structures and defects in response to the variable curvatures found in these capsids. To address this, we constructed CG models for five other morphologies of viral capsids, based off the prior experimental models developed by imaging the capsid structure within intact virions using cryo-ET30. Assembly simulations were performed until the capsids were completely encased by the TRIM5α lattice (Fig. 7). The overall lattice structures and defects formed were not significantly different among the capsid morphologies. Hexameric, pentameric, and heptameric structures were present in all cases. Two of the capsid structures had very narrow ends, which caused a tetrameric defect and a puckered hexamer to form (Fig. 7b, c). Assembly on two other capsid morphologies resulted in slightly incomplete lattices on the broad ends of the capsid (Fig. 7d, e).

Fig. 7. TRIM5α binds to multiple capsid morphologies.

a–e Note the presence of pentameric and heptameric defects. CG capsid morphologies were derived from directly fitting cryo-ET data of the core structure collected from intact virions30.

Discussion

Taken together, our simulation results suggest a surprisingly rich and complex dynamical picture of how TRIM5α encages the viral capsid core to block HIV-1 infectivity. Presently, simulation is indispensible for studying such dynamical effects since experimental techniques cannot yet provide this information. Diffusive motion of individual dimers on the capsid surface leads to a dynamical growth of the lattice, in which continual assembly and disassembly of the lattice is necessary to drive the encaging process. We predicted and experimentally validated the existence of pentameric and heptameric defects, and suggest that metastable tetrameric defects may also form in regions of high CA curvature. These defects are required to enclose the capsid and may allow the TRIM5α lattice to adapt to the varied capsid structures found in pleomorphic viruses like HIV. Since retroviruses apply strong selective pressures on their host elements, we speculate that the high sensitivity in the competing interactions that determine assembly (between dimers and between individual dimers and CA) indicates they are finely tuned by evolution for encaging the viral capsid.

Do other TRIM proteins self-assemble in this fashion? The answer so far, is unclear. Given the high conservation of the B-box motif compared to the SPRY domain, host cells seem to have adapted a modular response in the TRIM system, whereby distinct SPRY domains can be swapped to provide specific affinity for targets. These targets bind to the variable loops of the SPRY domain. TRIM21 is an autoantigen, for example, whose SPRY domain binds the IgG antibody with high affinity48, and can reportedly neutralize IgG-coated viral capsids49,50. Mutations in the variable loops of the SPRY domain of TRIM20 cause genetic disorders such as Familial Mediterranean Fever51. TRIM28 mediates transcriptional silencing of murine leukemia virus52,53. Furthermore, TRIM43 is an antiviral protein that has been recently reported to specifically block herpesvirus infection54.

The diversity of biological roles these TRIM proteins play, from autophagy to cell differentiation, implicates a general function for these proteins in cellular compartmentalization and scaffolding. Investigations into the mechanisms of these proteins may inform general principles towards the design of self-assembling, encaging nanostructures.

Methods

CG protein models

The initial atomic model for the TRIM5α monomer was constructed by assembling crystallographic fragments of the RING (PDB ID: 4TKP), SPRY (PDB ID: 2LM3), B-box and coiled-coil domains (PDB ID: 4TN3), available in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org). Missing amino acid backbone were built using the Modloop server55 and missing side chains were built using SCWRL456 to generate an atomic model of full-length TRIM5α. Two-fold symmetry was imposed on the monomer and aligned with a partially resolved structure of the dimer (PDB ID: 4TN3).

The coarse-grained (CG) model was constructed by mapping five amino acid residues into one CG particle using methods similar to ones we have previously published25–27. Secondary structure elements within each distinct protein domain (RING: resid 1–81; SPRY: resid 286–497) were constrained as rigid bodies, and regions within the coiled coil domain dimer were also held as rigid bodies (Coiled-coil: resid 91–161, 166–216, and 221–281). TRIM5α proteins were modeled as dimers, since the dimer is significantly more stable than the monomer. TRIM5α are primarily dimeric in solution57 in part due to the extensive network of coiled-coil interactions across the length of the protein and has not been found to crystallize nor bind to CA as a monomer. Flexibility in the linker regions between the RING and B–box domains was added using harmonic bonds between neighboring CG particles (resid 81–91, Kbond = 10 kcal mol−1 Å−2). Similarly, flexibility in the SPRY and coiled-coil regions, and within the coiled-coil domain were maintained using a primitive elastic network model (ENM) that connected two adjacent groups of CG particles within a cutoff distance, rcut, with flexible harmonic bonds; the potential energy of the each bond is:

| 1 |

where r is the separation distance, and r0 is the equilibrium bond length, set to the distance found in the crystal structure (SPRY–CC resid 286–291, resid 176–202; rcut = 17.8 Å; Kbond = 2.5 kcal mol−1 Å−2, and CC resid 156–161, 226, 266, resid 166–171, 216–221, 271; rcut = 30 Å; Kbond = 0.5 kcal mol−1 Å−2). The spring constants for the bonded interactions at the interface of the RING domain and coiled-coil region were chosen to mimic an unstructured polymer chain, and the spring constants for the ENM at the interface between the coiled-coil region and SPRY domain were chosen to maintain non-bonded hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between the L2 linker region and the SPRY domain58. Varying the spring constants for both interactions by a factor of ten did not significantly change the assembly behavior. Flexibility in the coiled-coil region however was necessary for the lattice to adapt to the varying curvatures in the capsid. Initial models that contained rigid coiled-coil domains formed flat 2D hexagonal arrays. The spring constants for the ENM in the coiled-coil region were lowered from 1.5 kcal/mol to 0.5 kcal/mol in increments of 0.25 kcal/mol until the lattice was observed to wrap around the capsid core. To maintain the overall CG protein shape, each CG particle included excluded volume interactions, using a soft cosine potential UVol given by:

| 2 |

when r < rc. The cutoff (rc), the onset of excluded volume repulsion, between CG particles was set to the separation distances found in the crystallographic fragments of TRIM5α or the trimer-of-dimers interface if the distances were less than 10 Å, or otherwise 10 Å, since CG particles at this resolution have an average radii of 5 Å. A = 100 kcal/mol. The mass of the protein (57.31 kDa) was evenly distributed among the CG beads.

Non-bonded protein–protein interactions between TRIM5α dimers were added on the basis of X-ray structures of truncated TRIM5α RING, B-box, Coiled-coil and SPRY domains (mini RBCCs, PDB ID: 5IEA) that crystallized in the trimer-of-dimers configurations to mimic the alternating electrostatic, hydrophobic, and electrostatic contacts at the B-box interface. Full-length CG TRIM5α models were fit into the electron density to construct the trimer-of-dimers structure, and virtual CG particles for each monomer were added to the relative positions of the following residues on an adjacent TRIM5α monomer (resid 91–106, 121–151, 231–241, and 256–261). Each of the virtual particles was allowed to tether to any CG particle that represented the same residue used to generate its position, using an attractive Gaussian potential given below:

| 3 |

where εP = 0.7 kcal/mol is the well-depth, B = 0.01 Å−2 is the inverse interaction length, r0 = 0 Å, and r is the distance between the virtual particle and a CG particle that represented the same residue.

Non-bonded protein–protein interactions between the SPRY domain and CA were added on the basis of experimental mutagenesis studies21,29. Attractive interactions were assigned between CA residues (resid 83–132) that when mutated demonstrated impaired binding of TRIM5α and the variable loops of the SPRY domain (resid 326–351, 381–396, and 421–426) using the same Gaussian potential as the TRIM5α–TRIM5α dimer interaction with εC = 0.28 kcal/mol, and B = 2 Å−1, r0 = 20 Å. Contributions from non-specific interactions (e.g. dispersion forces) were assumed to be small enough to be negligible in this CG model.

CG capsid models

Regular polygons were fit into electron cryo-tomography densities derived from intact virions30. Atomic models for the CA protein were then constructed from x-ray structures of the hexameric and pentameric capsomere structures (PDB ID: 3MGE, PDB ID: 3P05). Missing backbone and sidechain residues were built using Modloop and SCWRL4, and the model was subsequently coarse-grained at a resolution of 1 CG bead per 5 amino acid residues. To generate initial models of the capsid, the CG model was fit to the Cartesian coordinates and relative orientations of the polygons. The initial model was relaxed using a primitive elastic network model between C-terminal dimer contacts (resid 178–194, resid 178–194; rcut = 20 Å; Kbond = 0.1 kcal mol−1 Å−2), and a brief 20 ps CG molecular dynamics simulation.

MD simulations

All CG molecular dynamics simulations used the large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS)59. In all cases, a temperature of 300 K was maintained with a Langevin thermostat. Solvent was treated implicity during Langevin dynamics, with a damping constant (tdamp = 200 ps) and included a frictional coefficient of (m/tdamp) in the equations of motions to dampen sensitivity to protein–protein interactions, where m is the mass of a CG particle. A CG MD timestep of 200 fs was chosen, as the largest possible timestep without noticeable energy drift in the microcanonical (constant NVE) ensemble. The energy drift during test and production simulations is shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. Time integration was performed with the velocity Verlet algorithm. Simulation systems were initialized by placing TRIM5α subunits, uniformly distributed along the (x, y, z) dimensions and 150 Å from any capsid protein domain residues, in random orientations. Periodic boundary conditions were imposed on a simulation box centered on the center-of-mass of a CG HIV-1 capsid. The simulation box size was chosen as 0.064 μm3 to mimic a concentration of 3.2 μM, similar to that used in in vitro assembly experiments (0.25–5 μM)16–18. In total, each simulation consisted of ~1500 proteins. Similar to prior studies25–27, we report “CG time” in units of τ = 250,000 CG timesteps for all trajectories because of the well-known separation between CG and real-time dynamics60,61. Each system was run until lattice growth plateaued (~2.1 × 109 CG timesteps).

Diffusivity calculations

The diffusivities and mean-square displacements were computed for the center-of-geometry for residues in the B–box domain (resid 259–263). Statistics were collected across all assembly simulations for the six capsid morphologies and CA tube (~59,500 τ), and displacements were measured for each lag time in increments of τ. The MSD profiles for dimer populations in bulk solvent were fit to: MSD(t) = dt; whereas the MSD profiles for dimers on the capsid, or lattices on the capsid were fit to: , which approaches dt for t << 1 and s − e−λt for t >> 1 with s = MSD(t = ∞), and subsequently normalized by the MSD(t = 10τ). Monomers/dimers were assigned as bound to the capsid if any CG bead was within 40 Å of any CA particle. Monomers/dimers were assigned to form lattice contacts if any B–box domain residue was within 30 Å of a B-box domain residue belonging to another monomer/dimer. Monomers/dimers were considered to be free if they were not bound and did not form lattice contacts.

Pair correlation function calculations

Pair correlation functions, g(r), were computed for the center-of-geometry of residues in the B–box domain (resid 259–263). Statistics were collected for frames in the assembly simulations for the 6 capsid morphologies and CA tube that contained hexameric or pentameric structures (~55,000 τ). Our CG models for TRIM5α and CA were flexibly fit into the experimental cryo-ET densities (Fig. 4b) to generate a snapshot for which the g(r) was also calculated. All calculations used a 0.5 Å bin width and 200 nm cutoff.

SPRY–CA binding interface

CA residues within 20 Å of the SPRY domain were tabulated for all frames in the assembly simulations for the 6 capsid morphologies and CA tube (~59,500 τ) in increments of τ, and subsequently normalized to produce a contact probability distribution. The same calculation was performed for the CG model derived from the experimental cryo-ET density of TRIM5α associated with the helical CA tube, containing 2620 TRIM5α monomers. 3D volumetric densities were computed for the CG model of CA and then colored according to the contact probability values of each CG bead.

Electron cryotomography and lattice mapping

TRIM5α coated HIV-1 CA tubes were prepared by co-incubation of the purified proteins17,18. The sample was mixed with equal volume of 10 nm BSA Gold Tracer (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and then applied on glow-discharged C-flat grids (Protochips) and plunge-frozen into liquid ethane. Cryo-tomograms were acquired using an FEI Titan Krios electron microscope operating at 300 kV and equipped with a Falcon II camera. Tilt series were collected using the data collection software Tomography 3.0 (FEI) with an angular range of −60° to +60°, angular increment of 1°, and pixel (px) size of 2.92 Å. Tomogram reconstruction was performed using the weighted back-projection approach in IMOD62. Weighted back-projection was used to reconstruct tomograms, and the contrast transfer function (CTF) was applied in IMOD. Lattice mapping was performed using the sub-tomogram averaging algorithms in the Dynamo software package63.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Simone Mattei and John Briggs for preparing and sharing data for the HIV-1 viral capsids, and we thank John Briggs for helpful discussions and a careful read of the manuscript. This work was supported by the NIH Grant P50 AI150464, and for computing resources used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) Stampede2 at the Texas Advanced Computing Center under allocation TG-MCA94P017, which is supported by the National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1548562, and the Blue Waters sustained-petascale computing resources, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (awards OCI-0725070 and ACI-1238993). A.Y. gratefully acknowledges partial support from the Yen Fellowship from the Institute of Biophysical Dynamics at the University of Chicago.

Source Data

Author contributions

A.Y., B.K.G.-P., O.P., and G.A.V. designed research. A.Y. and K.A.S. performed research; A.Y., B.K.G.-P., and O.P. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; A.Y., K.A.S., B.K.G.-P., O.P., and G.A.V. analyzed data; and A.Y., K.A.S., A.J.P., B.K.G.-P., O.P., and G.A.V. wrote the paper

Data availability

All data generated and used in this study, including the coarse grained-models, are available at https://github.com/alvinyu33/trim5-public/ or upon request to the corresponding author. The source data underlying Figs. 5a and 6a are provided as a Source Data file.

Code availability

All code generated and used in this study are available upon request to the corresponding author, Gregory A. Voth.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Arthur Olson, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-15106-1.

References

- 1.Ozato K, Shin D-M, Chang T-H, Morse Iii HC. TRIM family proteins and their emerging roles in innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:849–860. doi: 10.1038/nri2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNab FW, Rajsbaum R, Stoye JP, O’Garra A. Tripartite-motif proteins and innate immune regulation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011;23:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatakeyama S. TRIM family proteins: roles in autophagy, immunity, and carcinogenesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017;42:297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Gent M, Sparrer KMJ, Gack MU. TRIM proteins and their roles in antiviral host defenses. Annu Rev. Virol. 2018;5:385–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-092917-043323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandell MA, Kimura T, Jain A, Johansen T, Deretic V. TRIM proteins regulate autophagy: TRIM5 is a selective autophagy receptor mediating HIV-1 restriction. Autophagy. 2014;10:2387–2388. doi: 10.4161/15548627.2014.984278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada Y, et al. A novel prognostic factor TRIM44 promotes cell proliferation and migration, and inhibits apoptosis in testicular germ cell tumor. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:32–41. doi: 10.1111/cas.13105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sparrer KMJ, Gack MU. TRIM proteins: new players in virus-induced autophagy. PLOS Pathog. 2018;14:e1006787. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng H, et al. Knockdown of MAML1 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells through SP1-dependent inactivation of TRIM59. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234:5186–5195. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stremlau M, et al. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5α restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature. 2004;427:848–853. doi: 10.1038/nature02343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sayah DM, Sokolskaja E, Berthoux L, Luban J. Cyclophilin A retrotransposition into TRIM5 explains owl monkey resistance to HIV-1. Nature. 2004;430:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature02777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pertel T, et al. TRIM5 is an innate immune sensor for the retrovirus capsid lattice. Nature. 2011;472:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nature09976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher AJ, et al. Trivalent RING assembly on retroviral capsids activates TRIM5 ubiquitination and innate immune signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24:761–775.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stremlau M, et al. Specific recognition and accelerated uncoating of retroviral capsids by the TRIM5alpha restriction factor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:5514–5519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509996103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grütter MG, Luban J. TRIM5 structure, HIV-1 capsid recognition, and innate immune signaling. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanz-Ramos M, Stoye JP. Capsid-binding retrovirus restriction factors: discovery, restriction specificity and implications for the development of novel therapeutics. J. Gen. Virol. 2013;94:2587–2598. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.058180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganser-Pornillos BK, et al. Hexagonal assembly of a restricting TRIM5α protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:534–539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013426108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y-L, et al. Primate TRIM5 proteins form hexagonal nets on HIV-1 capsids. eLife. 2016;5:e16269. doi: 10.7554/eLife.16269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner, J. M. et al. Mechanism of B-box 2 domain-mediated higher-order assembly of the retroviral restriction factor TRIM5α. Elife5, 16309 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Sebastian S, Luban J. TRIM5alpha selectively binds a restriction-sensitive retroviral capsid. Retrovirology. 2005;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biris N, et al. Structure of the rhesus monkey TRIM5α PRYSPRY domain, the HIV capsid recognition module. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13278–13283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203536109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang H, et al. Structural insight into HIV-1 capsid recognition by rhesus TRIM5α. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:18372–18377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210903109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Sodroski J. The TRIM5α B-Box 2 domain promotes cooperative binding to the retroviral capsid by mediating higher-order self-association. J. Virol. 2008;82:11495–11502. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01548-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner, J. M. et al. General model for retroviral capsid pattern recognition by TRIM5 proteins. J. Virol. 92, 1563–1517 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Campbell EM, Perez O, Anderson JL, Hope TJ. Visualization of a proteasome-independent intermediate during restriction of HIV-1 by rhesus TRIM5α. J. Cell Biol. 2008;180:549–561. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grime JMA, et al. Coarse-grained simulation reveals key features of HIV-1 capsid self-assembly. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11568. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pak AJ, et al. Immature HIV-1 lattice assembly dynamics are regulated by scaffolding from nucleic acid and the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E10056–E10065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706600114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madsen JJ, Grime JMA, Rossman JS, Voth GA. Entropic forces drive clustering and spatial localization of influenza A M2 during viral budding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E8595–E8603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805443115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pak AJ, Grime JMA, Yu A, Voth GA. Off-Pathway assembly: a broad-spectrum mechanism of action for drugs that undermine controlled HIV-1 viral capsid formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:10214–10224. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b01413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morger D, et al. The three-fold axis of the HIV-1 capsid lattice is the species-specific binding interface for TRIM5α. J. Virol. 2018;92:e01541–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01541-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattei S, Glass B, Hagen WJH, Kräusslich H-G, Briggs JAG. The structure and flexibility of conical HIV-1 capsids determined within intact virions. Science. 2016;354:1434–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.aah4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganser BK, Li S, Klishko VY, Finch JT, Sundquist WI. Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science. 1999;283:80–83. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pornillos O, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Yeager M. Atomic-level modelling of the HIV capsid. Nature. 2011;469:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature09640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell S, Vogt VM. Self-assembly in vitro of purified CA-NC proteins from Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 1995;69:6487–6497. doi: 10.1128/JVI.69.10.6487-6497.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li S, Hill CP, Sundquist WI, Finch JT. Image reconstructions of helical assemblies of the HIV-1 CA protein. Nature. 2000;407:409–413. doi: 10.1038/35030177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gross I, Hohenberg H, Huckhagel C, Kräusslich H-G. N-terminal extension of human immunodeficiency virus capsid protein converts the in vitro assembly phenotype from tubular to spherical particles. J. Virol. 1998;72:4798–4810. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.6.4798-4810.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan W, Briggs JaG. Cryo-electron tomography and subtomogram averaging. Methods Enzymol. 2016;579:329–367. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skorupka KA, et al. Hierarchical assembly governs TRIM5α recognition of HIV-1 and retroviral capsids. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaaw3631. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gamble TR, et al. Crystal structure of human cyclophilin a bound to the amino-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid. Cell. 1996;87:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price AJ, et al. Active site remodeling switches HIV specificity of antiretroviral TRIMCyp. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1036–1042. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caines ME, et al. Diverse HIV viruses are targeted by a conformationally dynamic antiviral. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:411–416. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard BR, Vajdos FF, Li S, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. Structural insights into the catalytic mechanism of cyclophilin A. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2003;10:475–481. doi: 10.1038/nsb927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kovalskyy DB, Ivanov DN. Recognition of the HIV capsid by the TRIM5α restriction factor is mediated by a subset of pre-existing conformations of the TRIM5α SPRY domain. Biochemistry. 2014;53:1466–1476. doi: 10.1021/bi4014962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu C, et al. Cyclophilin A stabilizes the HIV-1 capsid through a novel non-canonical binding site. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10714. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao Gongpu, Ke Danxia, Vu Thomas, Ahn Jinwoo, Shah Vaibhav B., Yang Ruifeng, Aiken Christopher, Charlton Lisa M., Gronenborn Angela M., Zhang Peijun. Rhesus TRIM5α Disrupts the HIV-1 Capsid at the InterHexamer Interfaces. PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7(3):e1002009. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacques DA, et al. HIV-1 uses dynamic capsid pores to import nucleotides and fuel encapsidated DNA synthesis. Nature. 2016;536:349–353. doi: 10.1038/nature19098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinn CM, et al. Dynamic regulation of HIV-1 capsid interaction with the restriction factor TRIM5α identified by magic-angle spinning NMR and molecular dynamics simulations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:11519–11524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800796115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ganser-Pornillos BK, Yeager M, Pornillos O. Assembly and architecture of HIV. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012;726:441–465. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0980-9_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.James LC, Keeble AH, Khan Z, Rhodes DA, Trowsdale J. Structural basis for PRYSPRY-mediated tripartite motif (TRIM) protein function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6200–6205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609174104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mallery DL, et al. Antibodies mediate intracellular immunity through tripartite motif-containing 21 (TRIM21) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:19985–19990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014074107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luban J. More than one way to TRIM a capsid. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:19517–19518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217596109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hesker PR, Nguyen M, Kovarova M, Ting JP-Y, Koller BH. Genetic loss of murine pyrin, the familial mediterranean fever protein, increases interleukin-1β levels. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolf D, Hug K, Goff SP. TRIM28 mediates primer binding site-targeted silencing of Lys1,2 tRNA-utilizing retroviruses in embryonic cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:12521–12526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805540105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee A, CingÖz O, Sabo Y, Goff SP. Characterization of interaction between Trim28 and YY1 in silencing proviral DNA of Moloney murine leukemia virus. Virology. 2018;516:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Full F, et al. Centrosomal protein TRIM43 restricts herpesvirus infection by regulating nuclear lamina integrity. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:164. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0285-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fiser A, Sali A. ModLoop: automated modeling of loops in protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2500–2501. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krivov GG, Shapovalov MV, Dunbrack RL. Improved prediction of protein side-chain conformations with SCWRL4. Proteins. 2009;77:778–795. doi: 10.1002/prot.22488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Langelier CR, et al. Biochemical characterization of a recombinant TRIM5α protein that restricts human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J. Virol. 2008;82:11682–11694. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01562-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roganowicz MD, et al. TRIM5α SPRY/coiled-coil interactions optimize avid retroviral capsid recognition. PLOS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006686. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Plimpton S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995;117:1–19. doi: 10.1006/jcph.1995.1039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Izvekov S, Voth GA. Modeling real dynamics in the coarse-grained representation of condensed phase systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125:151101. doi: 10.1063/1.2360580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davtyan A, Dama JF, Voth GA, Andersen HC. Dynamic force matching: a method for constructing dynamical coarse-grained models with realistic time dependence. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;142:154104. doi: 10.1063/1.4917454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Castaño-Díez D, Kudryashev M, Arheit M, Stahlberg H. Dynamo: a flexible, user-friendly development tool for subtomogram averaging of cryo-EM data in high-performance computing environments. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;178:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and used in this study, including the coarse grained-models, are available at https://github.com/alvinyu33/trim5-public/ or upon request to the corresponding author. The source data underlying Figs. 5a and 6a are provided as a Source Data file.

All code generated and used in this study are available upon request to the corresponding author, Gregory A. Voth.