Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi is a spirochete that can cause Lyme disease from an infected tick bite causing a myriad of syndromes ranging from erythema migrans to oligoarticular arthritis and/or atrioventricular conduction block in the heart. It can also infect the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) causing cranial neuropathy, radiculoneuropathy as well as myelopathy. It has rarely been reported to involve the phrenic nerve presenting as dyspnea from diaphragmatic paralysis. Here, we present a case of a patient presenting with orthopnea and dyspnea on exertion who was diagnosed with Lyme disease causing unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis with resolution after treatment.

Introduction

Lyme disease is a bacterial disease caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, transmitted by an infected tick bite. It can affect the nervous system at any stage of its infectivity. It can affect the central and peripheral nervous systems with presentations such as meningitis, meningoencephalitis, myelitis, cranial neuropathy and radiculopathy. Diaphragmatic paralysis caused by phrenic nerve palsy should prompt Lyme disease being included in the differential diagnosis as a cause in endemic areas. Here, we report a case of a patient presenting with unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis caused by Lyme disease.

Case report

A 65-year-old male was admitted to the hospital in early summer for one week of ongoing progressive dyspnea exacerbated by laying supine and exertion. He lived in a heavily wooded area in western Massachusetts in the United States and had noted several tick bites over the last several weeks to months. He had a remote history of Lyme disease. The presenting symptoms were preceded two weeks before by a non-painful, non-pruritic, large, erythematous, flat rash around the belt line that resolved spontaneously. He denied fever, chills, headaches, neck stiffness, nausea, vomiting, facial weakness, syncopal episodes, chest pain, abdominal pain, diarrhea/constipation and urinary issues. He had no significant past medical history or surgical history and he had known allergies to sulfonamides. Social history included being a never smoker, with social consumption of alcohol, no illicit drug use and reported having a cat at home for several years.

On presentation, he had a temperature of 98.2 degrees Fahrenheit, pulse 91 beats per minute (bpm), respiratory rate 21/min, blood pressure 144/85 mm Hg, and saturating 93 % on room air. Lab results included a white blood cell count of 7200/mm³ with normal differential count, hemoglobin 12.8 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen 21 mg/dL, creatinine 0.8 mg/dL, C-reactive protein 0.7 mg/dL, negative troponin, creatinine kinase 47 units/L, thyroid-stimulating hormone level 5.27 mIU/L, and negative Northeast tick panel PCR which included the DNA PCR testing for Babesia, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia. He tested positive for Lyme C6 antibody on ELISA and confirmed on Western Blot with IgM positivity (p23, p39 and p41 bands).

Chest x-ray demonstrated elevated left hemidiaphragm. Chest fluoroscopy demonstrated hypodynamic left hemidiaphragm confirming the diagnosis of left-sided diaphragmatic paralysis. Computed tomography (CT) chest without contrast was unremarkable except for 2 small lung nodules. Arterial blood gas testing showed a pH 7.48, pCO2 35 mmHg, pO2 78 mmHg, and bicarbonate 25 mmol/L on room air. Echocardiogram showed no evidence of systolic dysfunction and a normal global left ventricular ejection fraction.

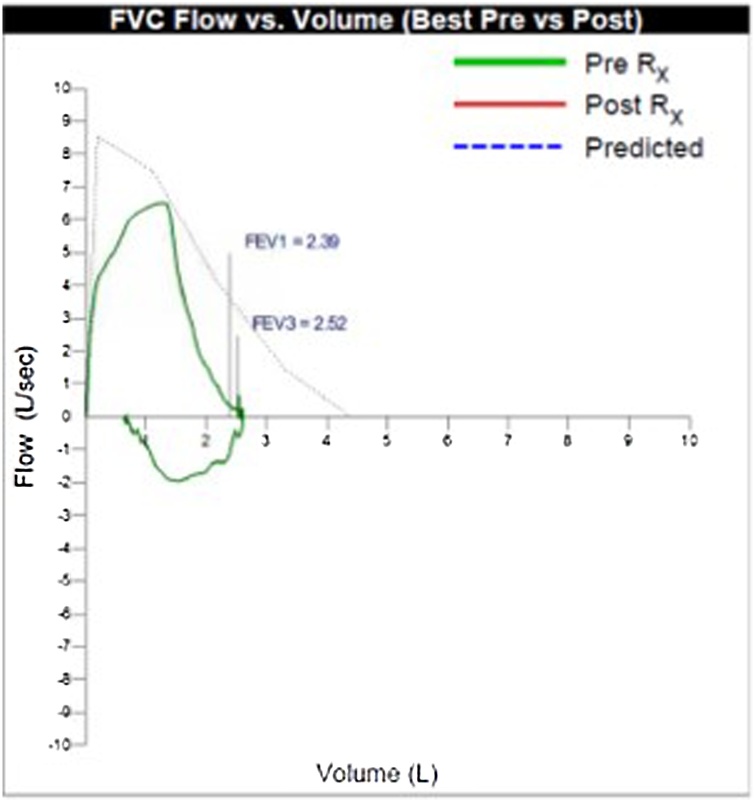

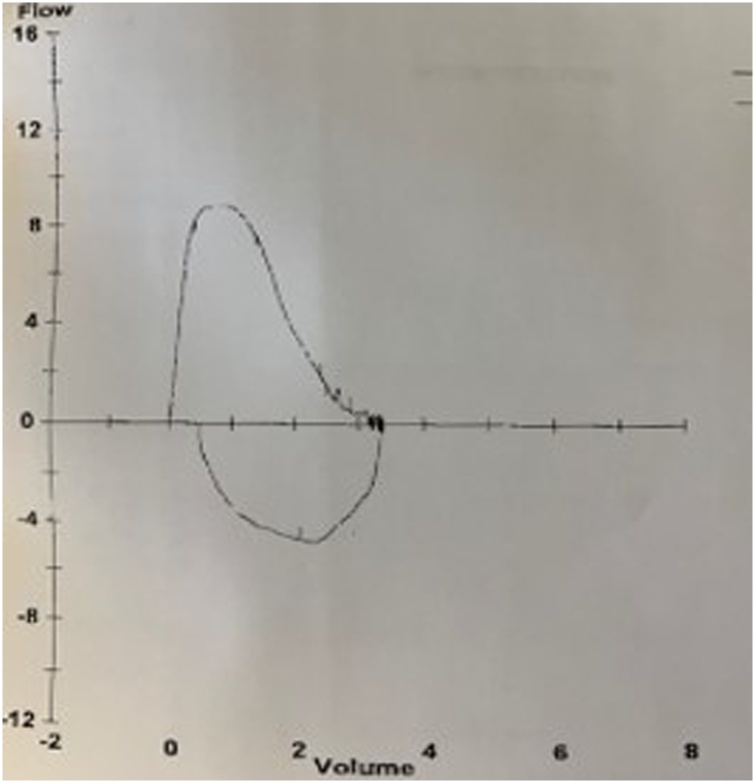

The patient was started on intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g daily. He was discharged on day 4 to complete a total of 3 weeks of antimicrobial therapy. He was evaluated 1 month later with pulmonary function testing (PFTs) showing moderate ventilation defect without obstruction and decreased vital capacity of 59 % of predicted, probably restrictive process. This was repeated a month later and there was improvement in the vital capacity to 69 % of predicted with moderate resolution of symptoms but still persisting dyspnea on supine position (Figs. 1,2). At 12 months post discharge, PFT demonstrated complete resolution with vital capacity now up to 81 % of predicted (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Flow volume loop one month after discharge.

Fig. 2.

Flow volume loop two months after discharge.

Fig. 3.

Flow volume loop 12 months after discharge.

Based on our review of literature, there are only 15 reported cases including three by van Egmond et al., citing Lyme disease as the etiology for phrenic nerve palsy and we have summarized all of them in the table below chronologically. Ours would be the 16th reported case.

| Case report | Sequence of symptoms | CSF studies | Diagnosis of lyme disease | Time of diagnosis of phrenic nerve palsy | Antimicrobial administered | Follow up evaluation of dyspnea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Melet et al. – 1987) [1] | Fever, left facial paralysis | Lymphocytic pleocytosis 225 cells | Serum Borrelia burgdorferi antibody rising titer | With the presentation | Ampicillin and netilmicin | Expired 3 months later from pulmonary embolism |

| 2 (Faul et al. - 1998) [2] | Skin rash 6 weeks prior, presenting with left facial weakness, right shoulder and bilateral knee pain, mild dyspnea | Not done | Serum Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and IgG antibodies positive | With the presentation | Doxycycline 3 weeks | Symptom-free 1 year later |

| 3 (Winterholler et al. - 2001) [3] | Dyspnea and cervical pain | 44 cells per cubic millimeter, 70 % lymphocytes, several plasma cells, 20 % monocytes and 10 % granulocytes, protein 1130 g/L, positive oligoclonal bands | Serum Borrelia burgdorferi IgG titer 1:160, CSF Borrelia burgdorferi IgG titer 1:64 | With the presentation | Ceftriaxone 2 courses, doxycycline 1 course | Chronic tracheostomy required |

| 4 (Ishaq et al.- 2002) [4] | Skin rash 3 months prior, facial palsy 1 week ago later, presenting with neck/back pain and dyspnea | White blood cell count 541/mm³ with 99 % lymphocytes, glucose 40 mg/dL, protein 271 mg/dL | CSF Borrelia burgdorferi PCR was negative, serum Borrelia burgdorferi IgG was positive and IgM was equivocal | With the presentation | Ceftriaxone 3 weeks | Significant improvement 3 weeks later |

| 5 (Gomez et al. - 2003) [5] | Known tick bite, lower extremity pain, dyspnea | Not done | Serum Borrelia burgdorferi IgM antibody positive | With the presentation | Doxycycline 1 month | No improvement 6 months later |

| 6 (Abbott et al. - 2004) [6] | Right leg weakness, abdominal distention, constipation followed by dyspnea on day 3 of hospitalization; tick mouthparts recovered from upper abdomen | White blood cell count 181/mm³ (100 % mononuclear), red blood cell count 22/mm³, glucose 2.3 mmol/L, protein 0.96 g/L | Serum Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and IgG antibodies positive | With the presentation | Ceftriaxone 4 weeks | Persistence with moderate improvement 1 year later |

| 7 (van Egmond et al. – 2010) [7] | Headache, dyspnea, diplopia | Lymphocytic pleocytosis 186 × 106/L mononuclear cells, glucose 3.6 mmol/L, protein 0.62 g/L | Serum and CSF Borrelia burgdorferi IgM antibody positive, CSF Borrelia burgdorferi PCR negative | With the presentation | Ceftriaxone 3 weeks | Complete resolution 2 years later |

| 8 (van Egmond et al. – 2010) [7] | Dyspnea, followed by radiculopathic pain in arms and right leg 3 months later, and then hospitalization with severe dyspnea | Lymphocytic pleocytosis | Serum and CSF Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and IgG antibodies positive | With the hospitalization | Doxycycline 2 weeks as outpatient, followed by ceftriaxone 4 weeks | Persistence with mild improvement 2 years later |

| 9 (van Egmond et al. – 2010) [7] | Bilateral thoracic shooting pain, dyspnea | Patient refused lumbar puncture | Serum Borrelia burgdorferi IgG antibody positive | With the presentation | Ceftriaxone 2 weeks | No improvement 2 years later |

| 10 (Torgovnick et al. - 2010) [8] | Noted paralysis of right hemidiaphragm on preoperative evaluation | Not done | Serum Borrelia burgdorferi IgG positive | With the presentation | Doxycycline, duration unknown | Lost to follow-up |

| 11 (Petrun et al. - 2013) [9] | Left lumboischialgia, obstipation, followed by dyspnea 2 weeks into hospitalization, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction 35 % | Leukocyte count 228/mL with lymphocyte predominance 205/mL | CSF Borrelia PCR was negative, CSF and serum IgG antibody for Borrelia burgdorferi 1:1.024 and 1:1.024, respectively and negative IgM antibodies | 2 weeks into hospitalization | Ceftriaxone 3 weeks | Persistence with moderate improvement 3 months later. |

| 12 (Djukic et al. - 2013) [10] | Headache, shooting left-sided thoracic pain, fatigue followed by dyspnea after discharge | Lymphocytic pleocytosis 129 cells per microliter, protein 1324 mg/L | CSF Borrelia burgdorferi-specific antibody index for IgG 5.0 and for IgM 0.8, negative CSF PCR | 2 days after 2 weeks of ceftriaxone | 2 weeks of ceftriaxone, followed by 2 weeks of oral doxycycline | Persistence with moderate improvement 6 months later |

| 13 (Basunaid et al. - 2014) [11] | Skin rash followed by low-grade fever, arthralgia and nocturnal hypoventilation | Not done | Serum Borrelia burgdorferi IgG antibody positive | With the presentation | Doxycycline 4 weeks | Resolution, duration of follow-up not reported |

| 14 (Reddy et al. - 2015) [12] | Headache, arthralgia, followed by right facial palsy and dyspnea on exertion | Total nucleated cells 2/mm³ (52 % lymphocytes), glucose 64 mg/dL, total protein 47 mg/dL | Serum Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and IgG antibodies positive | 14 weeks after antimicrobial therapy | Ceftriaxone 4 weeks | Persistence with moderate improvement 9 months later |

| 15 (Bon et al. – 2019) [13] | Tick bite, skin rash, treated with doxycycline, then dyspnea requiring hospitalization | 0 elements, 11 red cells, protein level 0.42 g/L (normal less than 0.40 g/L), glucose 4.37 mmol/L (normal between 2-4 mmol/L) | Serum and CSF Borrelia burgdorferi IgM and IgG antibodies positive | With the hospitalization | Ceftriaxone 3 weeks | Complete resolution 1 year later |

| 16 (our case) | Skin rash followed by dyspnea | Not done | Serum Borrelia burgdorferi IgM antibody positive | With the presentation | Ceftriaxone 3 weeks | Complete resolution 12 months later |

Discussion

Borrelia burgdorferi is a gram-positive spirochete that causes Lyme disease in United States. Other species of Borrelia that cause Lyme disease are found in Europe and some parts of the Middle East and Asia. Transmission is by an infected deer tick bite. Based on the area, the species of tick varies with Ixodes scapularis being the most common in northeast United States. It has been reported that the tick needs at least 48 h of bite time to effectively transmit the bacteria [14] and only a very small fraction of people with actual disease recall a tick bite. Lyme disease has 3 stages -early localized disease, early disseminated disease and late stage disease. Early localized disease is characterized by erythema migrans rash. It may be single or multiple and does not always have the classic “bull’s eye” appearance. They are often found in or near the axilla, inguinal region, popliteal fossa, or at the belt line. It does not usually require any diagnostic testing and should be treated. Early disseminated stage could be characterized by 2 or more lesions of erythema migrans and/or atrio-ventricular nodal block and/or neurological involvement. Late stage disease is typically associated with intermittent or persistent arthritis involving one or a few large joints, especially the knee, with or without neurologic problems like encephalopathy or polyneuropathy. The latter 2 stages when tested with serology studies are usually positive in the appropriate clinical setting.

Neurological involvement in Lyme disease in some parts of the world is called Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB). LNB may present as isolated cranial neuropathy, most commonly as lower motor neuron facial palsy, but has been known to cause a myriad of neurological presentations ranging from CNS to PNS involvement. It can cause meningitis, meningoencephalitis, myelitis, radiculopathy and peripheral neuropathy at any level of the nervous system. Only 16 cases so far (tabulated above), including ours, have been reported for Lyme disease as the etiology of phrenic nerve palsy (C3-C5 nerve supply).

Unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis has its own wide differential diagnoses including traumatic lesion from coronary artery bypass grafting being the most common cause [15]. Patients usually present with dyspnea, which is classically exacerbated in supine position with severity depending on extent of involvement of the diaphragm and the condition causing it. Suspicion for unilateral paralysis is raised when one hemidiaphragm is noted to be higher than the level of its counterpart (if right sided, then right higher than left by 2 cm, and if left sided, then left equal or higher than the right) on chest x-ray. In most cases, fluoroscopy with a sniff maneuver helps confirm the diagnosis where a paradoxical upward motion of the abnormal hemidiaphragm is observed. Further diagnostic methods to support the diagnosis that can be used include lung function testing, ultrasonography and sleep studies. LNB can affect the phrenic nerves causing unilateral or bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis and manifest without a well-defined incubation period.

Lyme disease is diagnosed via serological tests, although testing is not required in the early stages with the erythema migrans rash unless neurological involvement is also suspected. With serology, based on the current testing methods practiced in most of the facilities of United States, testing starts with a qualitative detection of antibodies against Lyme C6 antigen via Enzyme Linked Immunosorption Assay (ELISA) test and if positive, then gets reflexively directed to Western Blot testing. The presence of at least 2 out of 3 IgM bands and/or at least 5 out of 10 IgG bands establishes the diagnosis in an appropriately symptomatic patient with epidemiologic exposure. Only Ishaq et al. [4]) reported Western blot breakdown of their case, the rest were reported as positive based on detection of serum IgG and/or IgM antibodies. Melet et al. [1] used acute and convalescent antibody titers to establish their diagnosis. For CNS involvement, PCR testing for Borrelia burgdorferi has a very low sensitivity [16], as reflected by a negative result in the above tabulated cases whenever it was done. Inflammation of the meninges elicits the innate responses which are reflected in the CSF chemistry and breakdown in blood-brain barrier permits translocation of antibodies from serum into CSF, hence, the characteristic positive antibody tests on CSF specimens.

As noted in our patient's case as well as review of literature, the presentation of Lyme disease-associated phrenic nerve palsy can be variable with some of the patients recalling a skin rash and even sometimes a tick bite preceding the evaluation. It is usually the symptoms that develop afterwards that prompt the patients to seek medical attention. A chest x-ray ordered for patients with dyspnea will reveal an elevated diaphragm. In the appropriate geographical context, this should raise the suspicion for Lyme disease as an etiology for causing phrenic nerve palsy. Sometimes the abnormal chest x-ray findings can be incidental in an asymptomatic patient as reported by Torgovnick et al. [8]. Most of the reported cases were diagnosed with diaphragmatic paralysis based on an abnormal fluoroscopic sniff testing except for three. Winterholler et al. [3] and Petrun et al. [9] reported their respective cases being diagnosed with diaphragmatic paralysis based on electromyogram studies and Abbott et al. [6] reported their case being diagnosed with abnormal diaphragm movement noted on chest ultrasound. If diagnosed early, then early initiation of antimicrobials may assist in sooner resolution of symptoms. In fact, in the case described by Bon et al. [13], complete resolution could be reflected in the fact that CSF findings showed zero elements and the neural invasion was caught in its early stages and the patient was started on treatment immediately. We would like to make a special mention of the case report by Sigler et al. [17] who described a case of a 59-year-old woman presenting with weakness of upper extremities whose hospitalization was complicated by respiratory failure requiring intubation followed by tracheostomy. She tested positive for Lyme disease and later on confirmed abnormal activity in C5-C6 myotomes. Even though it was not specifically described, we believe involvement of C5 myotome may have possibly affected the diaphragm and thus, led to the respiratory failure. She improved significantly following antimicrobial therapy.

Antimicrobials that are effective against Lyme disease classically include cephalosporins, especially ceftriaxone and tetracyclines. European and American guidelines differ regarding the dosage and duration of treatment of each stage of the disease [18]. Unlike the European guidelines, the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) in 2006, recommended in their final report of 2010 [19], a single dose of 200 mg doxycycline may be offered to patients above 8 years of age, provided that tick has been attached for >36 h and is not given beyond 72 h of removal of the tick in areas where local infection rate of ticks is >20 %. Regardless of the choice of antimicrobial for established Lyme disease, outcomes are not well defined while treating Lyme disease associated phrenic nerve palsy. It is quite variable and perhaps influenced by the patient’s pre-existing comorbidities and how early the diagnosis is made and antimicrobials started along with supportive therapy. Only 3/16 (18.75 %) reported cases showed complete resolution of symptoms and one was lost to follow up. It becomes difficult to differentiate the persistence of symptoms due to diaphragmatic paralysis from post-treatment Lyme syndrome since the latter may have exhaustion and dyspnea as an ongoing presentation too.

In summary, Lyme disease should be considered on the list of differential diagnoses for patients presenting with diaphragmatic paralysis in Lyme-endemic area. It may manifest as unilateral or bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. Diagnosis can be made by the combination of demonstration of abnormal diaphragm movement plus confirmatory Western Blot testing for Lyme disease. Once the diagnosis is established, antimicrobial therapy must be given promptly and the treatment outcome is variable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abhimanyu Aggarwal: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Denzil Reid: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Durane Walker: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Abhimanyu Aggarwal, Email: Abhi.aggarwal@outlook.com.

Denzil Reid, Email: Denzil.ReidMD@baystatehealth.org.

Durane Walker, Email: Durane.Walker@baystatehealth.org.

References

- 1.Melet M., Gerard A., Voiriot P., Gayet S., May T., Hermann J. Me´ningoradiculone´vrite mortelle au cours d’une maladie de Lyme. Presse Med. 1986;15(41):2075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faul J.L., Ruoss S., Doyle R.L., Kao P.N. Diaphragmatic paralysis due to Lyme disease. Eur Respir J. 1999;13(March (3)):700–702. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13370099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winterholler M., Erbguth F.J. Tick bite induced respiratory failure. Diaphragm palsy in Lyme disease. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(June (6)):1095. doi: 10.1007/s001340100968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishaq S., Quinet R., Saba J. Phrenic nerve paralysis secondary to Lyme neuroborreliosis. Neurology. 2002;59(December (11)):1810–1811. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000035534.70975.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez de la Torre R., Suarez del Villar R., Alvarez Carreno F., Rubio Barbon S. Diaphragmatic paralysis and arthromyalgia caused by Lyme disease. Med Interna (Bucur) 2003;20(January (1)):47–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott R.A., Hammans S., Margarson M., Aji B.M. Diaphragmatic paralysis and respiratory failure as a complication of Lyme disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(September (9)):1306–1307. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.046284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Egmond M.E., Luijckx G.J., Kramer H., Benne C.A., Slebos D.J., van Assen S. Diaphragmatic weakness caused by neuroborreliosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;113(February (2)):153–155. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josh Torgovnick E.A., Sethi N.K., Sethi P.K. Phrenic nerve palsy as the sole manifestation of Lyme disease. East J Med. 2011;16(4) 272-3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrun A.M., Sinkovic A. Borreliosis presenting as autonomic nervous dysfunction, phrenic nerve palsy with respiratory failure and myocardial dysfunction - A case report. Cent Eur J Med. 2013;8(4):463–467. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Djukic M., Larsen J., Lingor P., Nau R. Unilateral phrenic nerve lesion in Lyme neuroborreliosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13(January (1)):4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basunaid S., van der Grinten C., Cobben N., Otte A., Sprooten R., Case Report Gernot R. Bilateral diaphragmatic dysfunction due to Borrelia burgdorferi. F1000Res. 2014;3:235. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.5375.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy K.P., McCannon J.B., Venna N. Diaphragm paralysis in lyme disease: late occurrence in the course of treatment and long-term recovery. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(April (4)):618–620. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201501-070LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bon C., Krim E., Colin G., Picard W., Gaborieau V., Gourcerol D. Bilateral diaphragmatic palsy due to Lyme neuroborreliosis. Rev Mal Respir. 2019;36(February (2)):197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro E.D. Clinical practice. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(May (18)):1724–1731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1314325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dube B.P. Dres M. Diaphragm dysfunction: diagnostic approaches and management strategies. J Clin Med. 2016;5(December (12)):113. doi: 10.3390/jcm5120113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marques A.R. Laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease: advances and challenges. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(June (2)):295–307. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sigler S., Kersaw P., Scheuch R., Sklarek H., Halperin J. Respiratory failure due to Lyme meningoradiculitis. Am J Med. 1997;103(December (6)):544–547. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)82271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borchers A.T., Keen C.L., Huntley A.C., Gershwin M.E. Lyme disease: a rigorous review of diagnostic criteria and treatment. J Autoimmun. 2015;57(February):82–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.09.004. (1095-9157 (Electronic)) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson L., Stricker R.B. The Infectious Diseases Society of America Lyme guidelines: a cautionary tale about the development of clinical practice guidelines. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2010;(June (5)):9. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]