Abstract

Stable matching problems with lower quotas are fundamental in academic hiring and ensuring operability of rural hospitals. Only few tractable (polynomial-time solvable) cases of stable matching with lower quotas have been identified; most such problems are -hard and also hard to approximate (Hamada et al. in Algorithmica 74(1):440–465, 2016). We therefore consider stable matching problems with lower quotas under a relaxed notion of tractability, namely fixed-parameter tractability. By cloning hospitals we focus on the case when all hospitals have upper quota equal to 1, which generalizes the setting of “arranged marriages” first considered by Knuth (Mariages stables et leurs relations avec d’autres problèmes combinatoires, Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, Montreal, 1976). We investigate how a set of natural parameters, namely the maximum length of preference lists for men and women, the number of distinguished men and women, and the number of blocking pairs allowed determine the computational tractability of this problem. Our main result is a complete complexity trichotomy: for each choice of parameters we either provide a polynomial-time algorithm, or an -hardness proof and fixed-parameter algorithm, or -hardness proof and -hardness proof. As corollary, we negatively answer a question by Hamada et al. (Algorithmica 74(1):440–465, 2016) by showing fixed-parameter intractability parameterized by optimal solution size. We also classify all cases of one-sided constraints where only women may be distinguished.

Keywords: Stable marriage, Lower quotas, Fixed-parameter algorithms

Introduction

The Stable Marriage (SM) problem is a fundamental problem first studied by Gale and Shapley [19]. An instance of SM consists of a set of men, a set of women, and a preference list for each person ordering members of the opposite sex. We aim to find a stable matching, i.e., a matching for which there exists no pair of a man and a woman who prefer each other to their partners given by the matching; such a pair is called a blocking pair. Gale and Shapley proved [19] that any instance of SM admits at least one stable matching, and gave a polynomial-time algorithm, known as the Gale–Shapley algorithm, to find one. Gale and Shapley also considered the many-to-one extension of SM, known as the Hospitals/Residents (HR) problem. In HR, the two sets and that correspond to men and women in the SM problem are residents and hospitals, respectively. Each hospital has an upper quota on the number of residents in that it can accept. For HR it still holds true that a stable matching always exists, and can be found efficiently.

An extension of HR that is motivated by several real-world applications is the Hospitals/Residents with Lower Quota (HRLQ) problem, where hospitals declare both lower and upper quotas which bound the number of residents they can accept; as before, residents rank hospitals and vice versa. Now it is no longer true that a stable assignment always exists. The possible non-existence of stable assignments motivates the design of algorithms that find an assignment with a minimum number of blocking pairs; this is the task of the HRLQ problem. Indeed, the HRLQ problem and its variants have recently gained quite some interest from the algorithmic community [4, 8, 16, 22, 24, 26, 30, 40, 44, 45]. In his book, Manlove [36, Chapter 5.2] devotes an entire chapter to the algorithmics of different versions of the HRLQ problem.

The reason for this high interest in HRLQ is explained by its importance in several real-world matching markets [17, 18, 42] such as school admission systems, centralized assignment of residents to hospitals, or of cadets to military branches. Lower quotas are a common feature of such admission systems. Their purpose is often to remedy the effects of under-staffing that are explained by the well-known Rural Hospitals Theorem [20]: as an example, governments usually want to assign at least a small number of medical residents to each rural hospital to guarantee a minimum service level. Minimum quotas are also discussed in controlled school choice programs [13, 33, 43] where students are divided into a small number of types, and schools set lower bounds for each type. Such models can represent various forms of affirmative actions taken by schools to, e.g., admit a certain number of minority students [13]. Another example is the German university admission system for admitting students to highly oversubscribed subjects, where a certain percentage of study places is assigned according to high school grades or waiting time [43]. But lower quotas may also arise due to financial considerations: for instance, a business course with too few (tuition-paying) attendees may not be profitable. Certain aspects of airline preferences for seat upgrade allocations can be also modelled by lower quotas [33].

Much of the algorithmic research found that the HRLQ problem (in its different variants) is -hard, and thus considered intractable. A common approach then to identify tractable (polynomial-time solvable) cases of HRLQ; this avenue has lead to several beautiful algorithms [16, 26, 45]. However, restricting to polynomial-time solvability necessarily means (if ) that some original features of HRLQ must be restricted more or less, which may be undesirable in the application. Another approach aimed at addressing the intractability of HRLQ was the design of approximation algorithms. Unfortunately, it turns out that non-trivial approximation algorithms for HRLQ are highly unlikely to exist: Hamada et al. [24] showed that, unless , no algorithm with approximation guarantee can exist for any (which they complement by an algorithm with approximation guarantee ). In light of their strong inapproximability bounds, Hamada et al. explicitly suggested to consider a more relaxed notion of tractability for HRLQ, namely, fixed-parameter tractability. They particularly asked whether HRLQ is fixed-parameter tractable parameterized by the minimum number b of blocking pairs over all matchings meeting all lower and upper quota requirements.

In this paper we follow this avenue, and study the fixed-parameter tractability of HRLQ. It allows us to provide a fine-grained analysis of HRLQ, and the design of efficient algorithms for -hard variants of HRLQ for small parameter values. Our main focus will be the case of HRLQ when each hospital has unit upper quota. The reason is that by the frequently applied method of “cloning” hospitals, stable instances of HRLQ reduce to the case where each hospital has unit upper quota—and thus we can reduce stable instances of HRLQ to the SM setting with lower quotas. In fact, this is equivalent to the special case of SM where only a subset of women (or, equivalently, men) are distinguished by having also a unit lower quota. From now on, we refer to HRLQ with unit upper quotas as SMC (where C means that we have to cover the women/men who have a unit lower quota), to the special case of SMC with one-sided covering constraints, linking SMC and HRLQ, as SMC-1. So formally, in SMC a set of women and a set of men are distinguished, and a feasible matching is one where each person in gets matched. By the Rural Hospitals Theorem [20] we know that the set of unmatched men and women is the same in all stable matchings, so clearly, feasible stable matchings may not exist. Thus, we define the task in SMC as finding a feasible matching with a minimum number of blocking pairs.

Apart from the recent interest in HRLQ, its reduction SMC also serves as a “modern version” of a classical problem first introduced by Donald Knuth. Knuth [31] considered SM with “arranged marriages”, which are a set of man-woman pairs that must be matched with each other. He showed that the Gale–Shapley algorithm can be extended to decide the existence of a stable matching still in time for n-person instances, but in case of absence of a stable matching, minimizing the number of blocking pairs is -hard. Now in SMC, one does not prescribe any more which woman has to marry which man, but only requires certain women and men to marry without dictating their partner. There is a natural Turing reduction from SMC to the variant considered by Knuth. Coarse analysis into polynomial-time solvable and -hard cases has been studied by several researchers [1].

Another motivation for studying the SMC problem comes from the following scenario that we dub Control for Stable Marriage. Consider a two-sided market where each participant of the market expresses its preferences over members of the other party, and some central agent (e.g., a government) performs the task of finding a stable matching in the market. It might happen that this central agency wishes to apply a certain control on the stable matching produced: it may favour some participants by trying to assign them a partner in the resulting matching. Such a behaviour might be either malicious (e.g., the central agency may accept bribes and thus favour certain participants) or beneficial (e.g., it may favour those who are at disadvantage, like handicapped or minority participants). However, there might not be a stable matching that covers all participants the agency wants to favour; thus arises the need to produce a matching that is as stable as possible among those that fulfil our constraints—the most natural aim in such a case is to minimize the number of blocking pairs in the produced matching, which yields exactly the SMC problem. Similar control problems have been extensively studied in the area of social choice for voting systems [7, Chapter 7] and recently also for fair division scenarios [2], but have not yet been considered in connection to stable matchings.

Our Results

We provide an extensive algorithmic analysis of the SMC problem and its special case SMC-1. In our analysis, we examine how different aspects of the input influence the tractability of these problems. To this end, we apply the framework of parameterized complexity, which deals with computationally hard problems and focuses on how certain parameters of a problem instance influence its tractability; for background, we refer to the book by Cygan et al. [11]. We aim to design so-called fixed-parameter algorithms, which perform well in practice if the value of the parameter on hand is small (for the precise definitions, see Sect. 2).

The parameters we consider are

the number b of blocking pairs allowed,

the number of women with covering constraint,

the number of men with covering constraint,

the maximum length of women’s preference lists, and

the maximum length of men’s preference lists.

The choice of each of these parameters is motivated by the aforementioned applications. For instance, we seek matchings where ideally no blocking pairs at all or at least only few of them appear, to ensure stability of the matching and happiness of those getting matched. The number of women/men with covering constraints corresponds, for instance, to the number of rural hospitals for which a minimum quota specifically must be enforced, which we can expect to be small among the set of all hospitals accepting medical residents. Finally, preference lists of hospitals and residents can be expected to be small, as each hospital might not rank many more candidates than the number of positions it has to fill, whereas residents might rank only their top choices of hospitals.

We investigate in detail how these parameters influence the complexity of the SMC problem. A parameterized restriction of SMC with respect to the set means a (possibly parameterized) special case of SMC where each element of S is either restricted to be some constant integer, or regarded as a parameter, or left unbounded. Intuitively, these different choices for the elements of S correspond to their expected “range” in applications, from very small to mid-range to large (compared to the size of the entire system). By considering all combinations, we can flexibly model the whole range of applications mentioned above. We can even cover some cases of master lists, where all men’s preference lists are restrictions of the exact same total order over the women, and likewise all women’s preference lists are restrictions of the exact same total order over the men.

Theorem 1

Any parameterized restriction of SMC with respect to is in , or -hard and fixed-parameter tractable, or -hard and -hard with the given parameterization,1 and is covered by one of the results shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of our results for Stable Marriage with Covering Constraints

| Constants | Parameters | Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| , | in (Gale–Shapley algorithm) | |

| in (Theorem 7) | ||

| in (Theorem 7) | ||

| in (Theorem 8) | ||

| in (Observation 2) | ||

| b | in (Observation 1) | |

| -hard (Theorem 9) | ||

| -hard (Theorem 10) | ||

| -hard (Theorem 2) | ||

| -hard (Theorem 5) | ||

| (Theorem 11) | ||

| b | (Corollary 3) | |

| (Theorem 12) |

Here, denotes the maximum length of the preference list of any distinguished person

In particular, SMC is -hard parameterized by , even if there are no distinguished men (i.e., ), there is a master list over men as well as one over women, , and each distinguished woman finds only a single man acceptable.

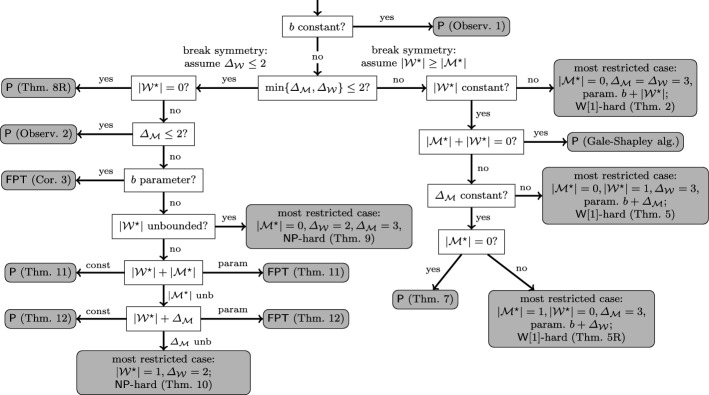

We give a decision diagram in Sect. 7 to show that the presented results indeed cover all restrictions of SMC with respect to . Table 1 summarizes our results on the complexity of SMC. Note that some results are implied directly by the symmetrical roles of men and women in SMC, and thus are not stated explicitly. Here and later, we assume for simplicity that and .

As a special case, we answer a question by Hamada et al. [24] who gave an exponential-time algorithm that in time decides for a given instance I of HRLQ whether it admits a feasible matching with at most b blocking pairs;2 the authors asked whether HRLQ is fixed-parameter tractable parameterized by b. As shown by Theorem 1, SMC-1 and therefore also HRLQ is -hard when parameterized by b, already in a very restricted setting. Thus, the answer to the question by Hamada et al. [24] is negative: SMC-1, and hence HRLQ, admits no fixed-parameter algorithm with parameter b unless .

Related Work

There is a dynamically growing literature on matching markets with lower quotas [4, 8, 16–18, 22, 24, 26, 30, 40, 44, 45]. These papers study several variants of HRLQ, adapting the general model to the various particularities of practical problems. However, there are only a few papers which consider the problem of minimizing the number of blocking pairs [17, 24]. The most closely related work to ours is the paper by Hamada et al. [24]: they prove that the HRLQ problem is -hard and give strong inapproximability results; they also consider the SMC-1 problem directly and propose an time algorithm for it.

A different line of research connected to SMC is the problem of arranged marriages, an early extension of SM suggested by Knuth [31]. Here, a set of man-woman pairs is distinguished, and we seek a stable matching that contains as a subset. Thus, as opposed to SMC, we not only require that each distinguished person is assigned some partner, but instead prescribe its partner exactly. Initial work on arranged marriages [23, 31] was extended by Dias et al. [12] to consider also forbidden marriages, and was further generalized by Fleiner et al. [15] and Cseh and Manlove [10]. Despite the similar flavour of the studied problems, none of these papers have a direct consequence on the complexity of SMC.

Our work also fits into the line of research that addresses computationally hard problems in the area of stable matchings by focusing on instances with bounded preference lists [6, 27, 29, 32, 41] or by applying the more flexible approach of parameterized complexity [1, 3, 5, 37, 38].

Organization After the preliminaries in Sect. 2, we start with the main intractability result in Sect. 3, which answers Hamada et al.’s question. This result shows -hardness of SMC parameterized by even when and . Thus, we explore three directions to achieve tractability: (i) to lower b to be a constant, (ii) to lower to be a constant, or (iii) to lower either or to 2. We cover the cases (i) and (ii) in Sect. 5, and case (iii) in Sect. 6. In addition, Sect. 4 provides polynomial-time approximation results for HRLQ and SMC, used also in the polynomial-time algorithms of Sect. 5.

Preliminaries

An instance I of the Stable Marriage (SM) problem consists of a set of men and a set of women. Each person has a preference list L(x) that strictly orders the members of the other party acceptable for x. We thus write L(x) as a vector , denoting that is (strictly) preferred by x over for each i and j with . A matching M for I is a set of man-woman pairs appearing in each other’s preference lists such that each person is contained in at most one pair of M; some persons may be left unmatched by M. For each person x we denote by M(x) the person assigned by M to x. For a matching M, a man m and a woman w included in each other’s preference lists form a blocking pair if (i) m is either unmatched or prefers w to M(m), and (ii) w is either unmatched or prefers m to M(w). In the Stable Marriage with Covering Constraints (SMC) problem, we are given additional subsets and of distinguished people that must be matched; a matching M is feasible if it matches everybody in . The objective of SMC is to find a feasible matching for I with minimum number of blocking pairs. If only people from one gender are distinguished, then without loss of generality, we assume these to be women; this special case will be denoted by SMC-1.

The many-to-one extension of SMC-1 is the Hospitals/Residents with Lower Quotas (HRLQ) problem whose input consists of a set of residents and a set of hospitals that have ordered preferences over the acceptable members of the other party. Each hospital has a quota lower bound and a quota upper bound , which bound the number of residents that can be assigned to h from below and above. One seeks an assignment M that maps a subset of the residents to hospitals that respects acceptability and is feasible, that is, for each hospital h. Here, M(h) is the set of residents assigned to some by M. We say that a hospital h is under-subscribed if . For an assignment M of an instance of HRLQ, a pair of a resident r and a hospital h is blocking if (i) r is unassigned or prefers h to the hospital assigned to r by M, and (ii) h is under-subscribed or prefers r to one of the residents in M(h). The task in HRLQ is to find a feasible assignment with minimum number of blocking pairs.

Some instances of SMC may admit a master list over women, which is a total ordering of all women, such that for each man , the preference list L(m) is the restriction of to those women that m finds acceptable. Similarly, we consider master lists over men.

With each instance I of SMC (or HRLQ) we can naturally associate a bipartite graph whose vertex partitions correspond to and (or and , respectively), and there is an edge between a man and a woman (or between a resident and a hospital , respectively) if they appear in each other’s preference lists. We may refer to entities of I as vertices, or a pair of entities as edges, without mentioning explicitly. For a graph G, we denote its vertex set by V(G) and its edge set by E(G); furthermore, let denote the degree of vertex in G. A pathP in G is a series of vertices that contains each vertex at most once, with an edge of G connecting any two consecutive vertices of P. With a slight abuse of the notation, we will often identify paths with their edge sets; we will write to express that is a subpath of P. A matching in G is a set of edges such that no vertex in G is adjacent to more than one edges of M; note that a matching in an instance I of SMC indeed corresponds to a matching in the graph . For a matching M in G, a path P is called M-alternating, if among any two consecutive edges along P exactly one belongs to M. We will use a few other notions from the theory of matchings about the symmetric difference of matchings, see e.g., the book by Lovász and Plummer [35] for an introduction to this topic.

Parameterized complexity The framework of parameterized complexity deals with computationally hard problems, examining their complexity in a more detailed way than classical complexity theory. In a parameterized problem problem , each input instance I is associated with an integer k called the parameter. An algorithm which decides instances I of in time for some computable function f is called a fixed-parameter algorithm. Note that the dependence of the polynomial in the run time is constant, but the dependence on the parameter k can be arbitrary (and is typically exponential). However, if the parameter of a given instance is small, then such an algorithm can be useful in practice even if the overall size of the instance is large.

The class of problems admitting fixed-parameter algorithms is denoted by . To argue that a problem is not in , parameterized complexity provides a hardness theory. For two parameterized problems and , a parameterized reduction from to is a function f, computable by a fixed-parameter algorithm, that maps each instance of to an instance of such that (i) is a “yes”-instance of if and only if is a “yes”-instance of , and (ii) for some function g. The basic class of parameterized intractability is : proving a problem to be -hard is strong evidence that . Given some problem that is known to be -hard, a parameterized reduction from to some parameterized problem implies -hardness of as well.

For more on parameterized complexity, we refer the reader to the book by Cygan et al. [11].

Strong Parameterized Intractability of SMC

This section provides parameterized intractability and inapproximability results for SMC showing the hardness of finding feasible matchings with minimum number of blocking pairs. Namely, we prove SMC-1 to be -hard parameterized by the number b of blocking pairs we aim for plus the number of distinguished women, even in a very restricted setting.

Theorem 2

SMC-1 is -hard parameterized by , even if there is a master list over men as well as one over women, all preference lists are of length at most 3, and for each woman .

Before proving Theorem 2, let us quickly state a simple but useful claim.

Proposition 1

Let and be two matchings in an instance of SMC. Let (with ) be a maximal path in the symmetric differenc of and , denoted by . Then

P contains an edge that blocks either or , and

if is such that prefers to , then contains an edge that blocks either or .

Proof

We call a person a leftist if either , or and prefers to . Similarly, we call a rightist if either , or and prefers to . Observe that any person on P is either a leftist or a rightist. Moreover, the path P, and under the conditions of (b) also the path , must contain an edge such that x is a leftist and y is a rightist. Let be the matching that does not contain (where ). Then both x and y prefer being matched to each other as opposed to their situation in (where they may or may not be matched), proving both (a) and (b).

Proof of Theorem 2

We give a reduction from the -hard Multicolored Clique parameterized by the size of the solution [14]. Let G be the input graph, with its vertex set partitioned into k sets ; the task is to find a clique of size k in G containing exactly one vertex from each of the sets . We let denote those edges that run between and for some . We fix an ordering on the vertices and edges of G that places vertices of before vertices of whenever (the ordering on the edges of G can be chosen arbitrarily). We will write to denote the vertex following x in this ordering, and we let and denote the first and last vertices in , respectively. Similarly, we write for the edge following , and we let and denote the first and last edges in , respectively. We will also write and for the predecessor of x or , respectively. Also, we denote the h-th neighbor of some vertex x as n(x, h). For simplicity, we assume that G has no isolated vertices.

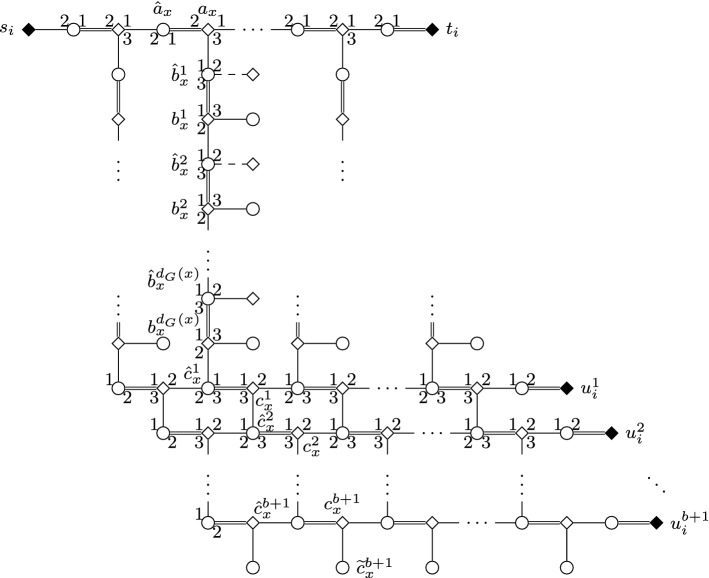

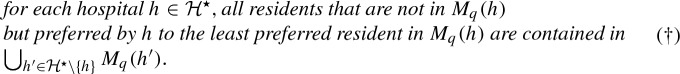

We construct an instance I of SMC as follows; see Figs. 1 and 2 for an illustration.

Fig. 1.

Node selecting gadget in the proof of Theorem 2. Throughout the paper, we use squares for women, circles for men; distinguished persons are denoted by filled squares/circles. The numbering of edges incident to some vertex (or, sometimes, arrows between edges) indicate preferences. Double edges denote edges of the stable matching , and dashed edges are those leaving some gadget

Fig. 2.

Edge selecting gadget in the reduction of Theorem 2

We set the number of blocking pairs allowed for I to be . Together with the instance I, we will define a stable (but not feasible) matching for I as well. If a woman w of I is matched by , we will denote the man by . Some women will need “dummy” partners in their preference lists: we denote the dummy of w by . The dummy will always appear as the last item on w’s preference list, and its preference list will always be .

For each i and j with , we construct an edge selecting gadget that involves women and , together with women , , and for each edge . All women in are matched by except for , and contains the man for each of these women w, together with additional dummies for each with x preceding y.

For each , we also construct a node selecting gadget involving women , and , together with women , , and for each . The men in include for each woman w of except for , and additional dummies and for each .

We define the following sets of women:

To define the set of women in I with covering constraint we let ; note . To finish the definition of I, we define the precise structure of these gadgets as well as the connections between them by the preference lists shown in Tables 2 and 3; when not stated otherwise, indices take all possible values. For simplicity, we write , , and for any vertex .

Table 2.

Preference lists of women and men in node selecting gadgets

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where , , | |

| where and , | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where , , and | |

| where , , and | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| for any dummy woman . |

Table 3.

Preference lists of women and men in edge selecting gadgets

| where and x precedes y, | |

| where and x precedes y, | |

| where and x precedes y in V(G), | |

| where and x precedes y in V(G), | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where x precedes y in V(G), | |

| where x precedes y in V(G), | |

| where , | |

| for any dummy woman . |

Let us define a master list over all women as follows. The first women in are those in T, in any ordering. They are followed by women in A, ordered according to the reversed ordering over V(G), that is, precedes exactly if y precedes x. Next follow women of , ordered according to the reversed ordering over E(G). Next come women in . To order them, we first order those in B by putting before in if and only if x precedes y or and , then for each edge with x preceding y, and we insert just before , and we insert just before , thus determining the ordering of . After women in come women of C, with preceding exactly if or and x precedes y. We finish the definition of the master list by putting all women in at the end of in an arbitrary order.

The master list over men is derived from by letting precede whenever precedes in , and adding all dummies at the end in an arbitrary order. It is easy to check that the preference lists given in Tables 2 and 3 are indeed compatible with these master lists. This completes the construction of the instance.

We are going to prove that the constructed instance I admits a feasible assignment with at most b blocking pairs if and only if there is a clique of size k in the graph G.

“”: Suppose there is a feasible matching M of men to women with at most b blocking pairs. Let be the symmetric difference . Notice that for each woman , the difference must contain exactly one maximal path containing s as its endpoint, since the women in S must be matched in M, but are unmatched in . Similarly, no path of can contain a woman in , because these women are matched by to their only possible partners, and they must be matched by M as well, since is contained in . We call a maximal path P in with an endpoint s in S an improving path. We say that Pstarts at s and ends at its other endpoint, and we refer to the path starting at (or ) as (or , respectively).

We define the cost of some path P of as the number of blocking pairs for M involving a woman w that appears on P. By Proposition 1, each improving path contains at least one edge that is blocking for M, because no edge can block . Therefore, each path in has cost at least 1.

As there are exactly improving paths (as all women in S must be matched by M), we get a minimum cost of . Note also that the total cost of all paths in cannot exceed . Claim 1 is therefore crucial.

Claim 1

The following holds for any improving path P of :

P cannot end at a dummy for some .

P contains an edge for some that blocks M.

If P is not disjoint from for some i, then P has cost at least 2.

Proof of Claim 1

To prove (a), suppose for contradiction that P ends at , where . Clearly, P must contain at least one woman from each of the sets , . Fix h, and let us consider the last for which is incident to an edge of . Let if , or otherwise let . Then the edge yields a blocking pair in M, as , and thus prefers to w. This reasoning gives us different blocking pairs for M, one for each index h, contradicting our assumption on M.

To prove (b), let us consider the case when for some i; the argument goes the same way for the case where for some i and j. If P ends at for some , then forms a blocking pair with in M. If P does not end at a woman in A, then it must contain the edge for some x, in which case is again blocking in M, showing (b).

To see (c), first observe that if P is not disjoint from , then P ends in , simply because of its property that it contains edges from M and in an alternating fashion. Therefore, the last woman w on P must be in . If for some , then the edge is blocking M, as cannot get its first choice in M (and cannot be on P, as that would imply that is on P, contradicting the choice of w). If, by contrast, for some , then P must end at w by (a), and then c forms a blocking pair with the third man in its preference list (for whom c is the first choice). In either case, w is involved in a blocking pair, which together with the blocking pair guaranteed by (b) implies that P has cost at least 2.

This completes the proof of Claim 1.

Claim 1 proves that for each the improving path has cost at least 2. Since all the remaining improving paths have cost at least 1, and the total cost of these paths must be at most , we get that any path (or ) must have cost exactly 2 (or 1, respectively). Furthermore, it also follows that no other path of can enter or start in , for any i, as that would imply that the number of blocking pairs for M is more than b. In addition, it is not hard to see that does not contain any cycle, because all cycles in the graph underlying I contain two consecutive edges not in . Hence, it follows that the only connected component in that is not disjoint from is .

To deal with the possible courses the path may take in the graph for some , let denote the vertex in for which is the blocking edge guaranteed by statement (b) of Claim 1. Observe that either ends at or contains the edge . In either case, we say that selects from ; clearly, there can be only one vertex in selected by .

Consider now for some . Recall that has cost 1. Therefore, statement (b) of Claim 1 proves that the only blocking edge incident to some woman on must be for some . We say that selects the edge ; without loss of generality, let us assume that x precedes y. By statement (c) of Claim 1, we also know that cannot leave , which means that it can only have cost 1 if it ends at . In particular, it contains the edges and . Observe that the edge where h is such that cannot be blocking in M (as this would indicate a cost of 2 for ), yielding that must be matched to in M. By the arguments of the previous paragraph, this means that must contain the subpath . Hence, we obtain that x must be selected by . Similarly, from the fact that the edge where is not blocking in M we get that y must be selected by .

Thus, we obtain that if an edge is selected by for some i and j, then its endpoints must be selected by and . As this must hold for each pair of indices with , we obtain that there must be edges in G whose endpoints are among the k selected vertices. This can only happen if these edges are the edges of a clique of size k.

“”: Suppose now that G has a clique of size k formed by the vertices , with for each . Instead of directly defining the required matching M that is feasible and admits at most b blocking pairs, we give as the union of paths for , and paths for , defined as follows.

We set as the path

Similarly, we define

It is straightforward to verify that the blocking pairs for M are then the k edges , , the k edges , and the edges , . The feasibility of M is trivial; this completes the proof of Theorem 2.

A fundamental hypothesis about the complexity of -hard problems is the Exponential Time Hypothesis (ETH), which stipulates that algorithms solving all Satisfiability instances in subexponential time cannot exist [28]. Assuming ETH, the fundamental Clique problem parameterized by solution size k was shown not to admit any algorithm giving the correct answer in time for all n-vertex instances and any computable function f [9, Thm. 5.4]. The known reduction from Clique to Multicolored Clique does not change the parameter [14]. Finally, in the proof of Theorem 2, an instance of Multicolored Clique with solution size k is reduced to an instance of SMC-1 with parameter .

Corollary 1

Assuming ETH, SMC-1 cannot be solved in time for any computable function , even if there is a master list over men and over women, all preference lists have length at most 3, and each woman in finds only a single man acceptable.

Polynomial-Time Approximation

Here we first provide a polynomial-time algorithm that yields an approximation for HRLQ with factor , where is the maximum length of residents’ preference lists and is the total sum of all lower quotas. Then we use this result to propose an exact polynomial-time algorithm for HRLQ for the case where both and are constant. Recall that in HRLQ, our objective is to find an assignment that satisfies all quota lower and upper bounds and minimizes the number of blocking pairs.

Theorem 3

Let I be an instance of HRLQ. Let denote the maximum length of residents’ preference lists, and let denote the sum of lower quota bounds taken over all hospitals in I. There is an algorithm that in polynomial time either outputs a feasible assignment for I with at most blocking pairs, involving only residents, or concludes that no feasible assignment exists.

Proof

Let denote the set of hospitals with positive lower quotas. We start by finding an assignment that assigns residents to each hospital , and has the following property:  Such an assignment can be obtained as follows. We start from an arbitrary assignment M that assigns residents to each (if no such assignment exists, then we can stop and reject); such an assignment, if existent, can be found in polynomial time by an algorithm of Hopcroft and Karp [25]. Then we greedily re-assign residents to hospitals of , one-by-one: at each step, we take a hospital , and if there exists a resident r not assigned to any other hospital in that h prefers to the least preferred resident in M(h), then we replace with r in M(h). If this step cannot be applied anymore, then we arrive at an assignment with the desired property ().

Such an assignment can be obtained as follows. We start from an arbitrary assignment M that assigns residents to each (if no such assignment exists, then we can stop and reject); such an assignment, if existent, can be found in polynomial time by an algorithm of Hopcroft and Karp [25]. Then we greedily re-assign residents to hospitals of , one-by-one: at each step, we take a hospital , and if there exists a resident r not assigned to any other hospital in that h prefers to the least preferred resident in M(h), then we replace with r in M(h). If this step cannot be applied anymore, then we arrive at an assignment with the desired property ().

Given , we reduce the upper quotas of each hospital by , set all lower quotas to 0, and delete all residents in . We then find a stable assignment in the resulting instance ; note that is an instance of HR, so we can find in polynomial time [19]. Finally, we output . Clearly, is feasible. Also, any blocking pair that admits must involve either a hospital from or a resident from by the stability of with respect to . Observe that if some is involved in some blocking pair of , then we must have . To see this, recall that each resident that is preferred by h to its least preferred resident in must be in because of property (), and furthermore, h is under-subscribed in (within I) if and only if h is under-subscribed in (within ). Therefore, we can conclude that each blocking pair for must involve some resident in ; observe that . Since each resident in is incident to at most edges not in , we also have that admits at most blocking pairs.

If both and are constant, then Theorem 3 implies that HRLQ becomes polynomial-time solvable. Indeed, we can use the following simple strategy, depending on the number b of blocking pairs allowed: if , then we apply Theorem 3 directly; if , then we use the algorithm by Hamada et al. [24] running in time which is polynomial, since b is upper-bounded by a constant.

Corollary 2

If both the maximum length of residents’ preference lists and the total sum of all lower quotas is constant, then HRLQ is polynomial-time solvable.

Another application of Theorem 3 is an approximation algorithm that works regardless of whether or is a constant. In fact, the algorithm of Theorem 3 can be turned into a -factor approximation algorithm as follows. First, we find a stable assignment for I in polynomial time using the extension of the Gale–Shapley algorithm for the Hospitals/Residents problem. If is not feasible, then by the Rural Hospitals Theorem [20], we know that any feasible assignment for I must admit at least one blocking pair; hence, the algorithm presented in Theorem 3 clearly yields an approximation with (multiplicative and also additive) factor .

To close this section, we also state an analogue of Theorem 3 that deals with SMC: it can handle covering constraints on both sides, but assumes that all quota upper bounds are 1.

Theorem 4

There is an algorithm that in polynomial time either outputs a feasible matching for an instance I of SMC with at most blocking pairs, or concludes that I admits no feasible matching.

Proof

The proof uses the same ideas as those used in our proof for Theorem 3, so the reader may skip the proof below, which we only include for completeness.

We start by finding an arbitrary matching M that covers each distinguished person (if no such matching exists, then we can stop and reject); such a matching, if existent, can be found in polynomial time by standard flow techniques. We assume, without loss of generality, that each edge in M is incident to some distinguished person. Let us define , and let be the set of those persons whose partner M(x) is also in .

We proceed by modifying M into a matching that covers and has the following property: ![]() Such an assignment can be obtained as follows. We greedily assign partners to the men and women in , one-by-one: at each step, we take a person , and if x forms a blocking pair (with respect to the current matching) with some y that is not the partner of a distinguished person, then we replace the partner of x with y: we add the edge to the matching, and delete all the other edges incident to x or y. Observe that the obtained matching is still feasible. If this step cannot be applied anymore, then we arrive at a matching with the desired property (); note also that each edge in is incident to some distinguished person.

Such an assignment can be obtained as follows. We greedily assign partners to the men and women in , one-by-one: at each step, we take a person , and if x forms a blocking pair (with respect to the current matching) with some y that is not the partner of a distinguished person, then we replace the partner of x with y: we add the edge to the matching, and delete all the other edges incident to x or y. Observe that the obtained matching is still feasible. If this step cannot be applied anymore, then we arrive at a matching with the desired property (); note also that each edge in is incident to some distinguished person.

Given , we delete all men and women covered by . We then find a stable matching in the resulting instance ; note that is an instance of Stable Marriage, so we can find in polynomial time [19]. Finally, we output . Clearly, is feasible. Also, any blocking pair that admits must involve a person covered by due to the stability of with respect to .

We claim that any blocking pair involves a person whose partner by is distinguished, so either or . We can assume that x is covered by (because this holds for at least one of x and y). To see the claim, first note that if x is not distinguished, then must be distinguished, because each edge of contains a distinguished person. Second, if , then either (in which case ) or because of property (). Therefore, we can conclude that each blocking pair for must involve the partner of some distinguished resident. The partners of distinguished women can be incident to at most blocking pairs, and similarly, the partners of distinguished men can be incident to at most blocking pairs, proving the theorem.

SMC with Bounded Number of Distinguished Persons or Blocking Pairs

In Theorem 2 we proved -hardness of SMC-1 for the case where , with parameter . Here we investigate those instances of SMC and SMC-1 where the length of preference lists may be unbounded, but either b, or the number of distinguished persons is constant.

First, if the number b of blocking pairs allowed is constant, then SMC can be solved by simply running the extended Gale–Shapley algorithm after guessing and deleting all blocking pairs. This complements the result by Hamada et al. [24].

Observation 1

SMC can be solved in time , where b denotes the number of blocking pairs allowed in the input instance I.

In Theorem 5 we prove hardness of SMC-1 even if only one woman must be covered. If we require preferences to follow master lists, then a slightly weaker version of Theorem 5, where , still holds.

Theorem 5

SMC-1 is -hard parameterized by , even if , , and .

Proof

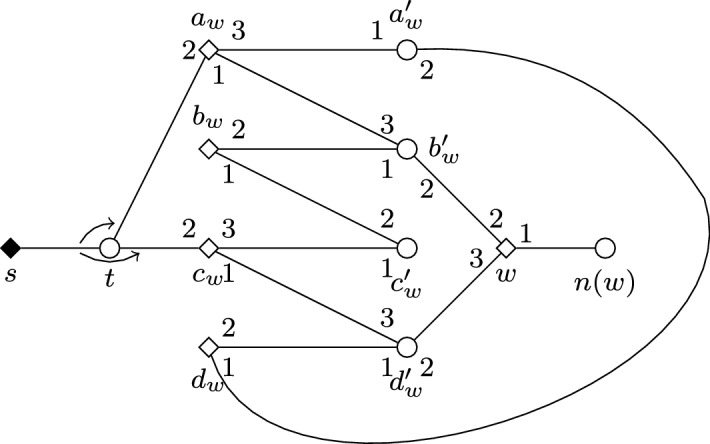

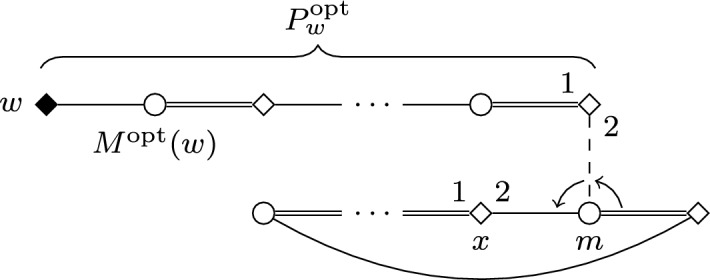

We present a reduction based on the one from Multicolored Clique given in the proof of Theorem 2. Given some graph G and an integer k as inputs, we are going to re-use the instance I constructed in the proof of Theorem 2. Recall that I has a feasible matching with at most blocking pairs if and only if G has a clique of size k. Recall also that the set of women that must be covered in I is ; here we denote this set by . We define a modified instance of SMC as follows. For each , we create a forcing gadget which apart from w contains the newly introduced women and men . We also add the distinguished woman s, who must be covered in , and the unique man t in L(s). See Fig. 3 for an illustration.

Fig. 3.

Illustration depicting the forcing gadget in the proof of Theorem 5

Let n(w) denote the unique man acceptable for some in I. Additionally, we let , and we write [Y] for an arbitrarily fixed ordering of the elements of Y. The preferences of the newly introduced men and women, as well as the modified preferences of those agents that find them acceptable, is given below. Here, again, indices take all possible values, and w can be any woman in . We let contain all other women and men defined in I, having the same preferences as in I.

We will show that has a feasible matching with at most b blocking pairs if and only if I has such a matching; this clearly proves the theorem.

First observe that any feasible matching for contains the edge . Thus, if some woman y in Y is not matched by to her first choice, then is blocking in . Consider now for some . It is straightforward to check that if , then there are at least two blocking pairs incident to a woman in . Indeed, assume first that is the only blocking pair in ; this quickly implies and , which in turn leads to blocking , a contradiction. Second, assume that does not block ; from this follows and we have that is a blocking pair for . Now either is blocking (in which case our claim holds), or we get , which implies that blocks , again a contradiction.

Now, let be the women in that must be covered in I, i.e., . Consider the number of blocking pairs for that involve a woman either in the gadget or in a gadget for some . On the one hand, if some is not matched by to n(w), then because of the blocking pairs in . On the other hand, if each is matched by to n(w), then using the arguments of the proof for Theorem 2, we again know because of the blocking pairs in . Also, can only be achieved if (i) , as otherwise would be blocking for , in addition to the two blocking pairs in , and (ii) for each , as otherwise we would have (so as to avoid having four blocking pairs due to women in and ), implying at least one blocking pair in in addition to those in .

Analogously, let denote the number of blocking pairs for that involve a woman either in the gadget or in a gadget for some . Then either , or we know that for both women ; in this case, from the proof of Theorem 2 we get . However, supposing that has at most blocking pairs, it follows that and must hold for each and each i, j with , respectively.

Along the same lines as in the proof of Theorem 2, it can also be verified that for each pair of indices i, j can only be achieved if contains a path in each gadget . From for each we get that such a path contains at least one blocking pair. This implies , as otherwise we would end up with because of the blocking pairs incident to women of .

Altogether, we have proved that for each . Hence, the restriction of to I yields a feasible matching for I that admits at most b blocking pairs.

For the other direction, suppose that I has a feasible matching M. Then it is easy to see that adding the edges , , , and for each together with the edge to M yields a feasible matching for that contains exactly the same number of blocking pairs in as M does in I.

Theorem 6

SMC-1 is -hard parameterized by , even if there is a master list over men as well as one over women, , , and for each .

Proof

The proof is very similar to the one for Theorem 5, so we will only sketch it. Again, we are going to re-use the instance I constructed in the proof of Theorem 2, and construct a modified instance of SMC, adding only two new women and and two men and to I. We append and , in this order, to the master list over women, and similarly, we append and to the master list over men. We define the women to be covered in as and .

Again, we denote the set of women to be covered in I by , and we denote by n(w) the unique man acceptable for some in I. The preferences of the newly introduced men and women, as well as the modified preferences of those agents that find them acceptable, is given below (here, denotes the ordering of given by the master list). We let contain all other women and men defined in I, having the same preferences as in I.

Arguing analogously as before in the proof of Theorem 5, one can show that has a feasible matching with at most b blocking pairs if and only if I has such a matching; this suffices to prove the theorem.

To contrast our intractability results, we show next that if each of the four parameters , , , and is constant, then SMC becomes polynomial-time solvable. Our algorithm relies on the observation that in this case, the number of blocking pairs in an optimal solution is at most by Theorem 4. Note that for instances of SMC-1, Theorem 7 yields a polynomial-time algorithm already if both and are constant.

Theorem 7

SMC can be solved in time .

Proof

By Theorem 4, there is a matching with at most blocking pairs. Hence, if the number b of blocking pairs allowed is at least , then we can simply run the algorithm of Theorem 4. Otherwise, we can use Observation 1, which gives us the required run time.

Importantly, restricting only three of the values , , , and to be constant does not yield tractability for SMC, showing that Theorem 7 is tight in this sense. Indeed, Theorem 5 implies immediately that restricting the maximum length of the preference lists on only one side still results in a hard problem: SMC remains -hard with parameter , even if , , and . On the other hand, Theorem 2 shows that the problem remains hard even if and .

SMC with Preference Lists of Length at Most Two

In this section we investigate the computational complexity of SMC where the maximum length of preference lists is bounded by 2 on one side. This restriction leads to important tractable special cases: we obtain both polynomial-time algorithms and fixed-parameter tractability results for various parameterizations.

Let I be an instance of SMC with underlying graph G. Let be a stable matching in I, and let and denote the set of distinguished men and women, respectively, unmatched by . Furthermore, let and denote the set of all men and women, respectively, unmatched by . A path P in G is called an augmenting path, if is a matching, and either both endpoints of P are in , or one endpoint of P is in , and its other endpoint is not distinguished. This definition ensures that for an augmenting path P, the set of distinguished men and women that are matched in strictly contains the set of distinguished men and women matched in .3 We will call an augmenting path Pmasculine or feminine if it contains a man in or a woman in , respectively; if P is both masculine and feminine, then we call it neutral. If P is not neutral, then we say that it starts at the (unique) person from it contains, and ends at its other endpoint.

Covering Constraints on One Side

Here we deal with the SMC-1 problem where only women need to be covered. We first give a polynomial-time algorithm for SMC-1 when each man finds at most two women acceptable, and then show -hardness of SMC-1 for instances where each woman finds at most two men acceptable. We start by considering the special case of SMC-1 where .

Theorem 8

There is a polynomial-time algorithm for the special case ofSMC-1 where each man finds at most two women acceptable.

High-Level Description The main observation behind Theorem 8 is that if , then any two augmenting paths starting from different women in are almost disjoint, namely they can only intersect at their endpoints. Thus, we can modify the stable matching by selecting augmenting paths starting from each woman in in an almost independent fashion: intuitively, we simply need to take care not to choose paths sharing an endpoint—a task which can be managed by finding a bipartite matching in an appropriately defined auxiliary graph. To ensure that the number of blocking pairs in the output is minimized, we will assign costs to the augmenting paths. Roughly speaking, the cost of an augmenting path P determines the number of blocking pairs introduced when modifying along P (though certain special edges need not be counted); hence, our problem reduces to finding a bipartite matching with minimum weight in the auxiliary graph.

To present the algorithm of Theorem 8 in detail, we start with the following properties of augmenting paths which are easy to prove using that :

Proposition 2

Suppose . Let and be augmenting paths starting at women and , respectively.

If , then and are either vertex-disjoint, or they both end at some , with .

If there is an edge of G (with and ) connecting and , then and or must end at m.

If and P is the maximal common subpath of and starting at , then either , or and both end at some and .

With a set P of edges (typically a set of augmenting paths) where is a matching, we associate a cost, which is the number of blocking pairs that admits. A pair for some and is special, if and w is the second (less preferred) woman in L(m). As it turns out, such edges can be ignored during certain steps of the algorithm; thus, we define the special cost of P as the number of non-special blocking pairs in .

Lemma 1

For vertex-disjoint augmenting paths and with cost and , respectively, the cost of is at most . Further, if the cost of is less than , then the following holds for : there is a special edge with ending at m and w appearing on ; moreover, is blocking in , but not in .

Proof

First observe that if some edge has a common vertex with only one of the paths and , say , then is blocking in if and only if it is blocking in .

Consider now the case when connects and . By Proposition 2, this implies that one of the paths, say , ends at (and w lies on ). Clearly, is not blocking in , by the stability of . If, on the one hand, w is the first choice of m, then is blocking in exactly if it is blocking in . If, on the other hand, is special, then it cannot be blocking in , but it might be blocking in . Putting all these facts together, the lemma follows immediately.

We are ready to provide the algorithm, in a sequence of four steps.

Step 1: Computing all augmenting paths By Proposition 2, if we delete from the union of all augmenting paths starting at some , then we obtain a tree. Furthermore, these trees are mutually vertex-disjoint for different starting vertices of . This allows us to compute all augmenting paths in linear time, e.g., by an appropriately modified version of a depth-first search algorithm (so that only augmenting paths are considered). During this process, we can also compute the special cost of each augmenting path in a straightforward way.

Step 2: Constructing an auxiliary graph Using the results of the computation of Step 1, we construct an edge-weighted single bipartite graph as follows. To define the vertices of we set and , so for each woman we create a corresponding new vertex . The edge set E contains an edge for each , as well as an edge whenever , and there exists an augmenting path with endpoints w and m. We define the weight of an edge as the minimum special cost of any augmenting path starting at w and not ending in , and we define the weight of an edge with and as the minimum special cost of any augmenting path with endpoints w and m.

Step 3: Computing a minimum weight matching We compute a matching in covering U and having minimum weight; this can be done in polynomial time by, e.g., the Hungarian method [34]. Observe that the matching corresponds to a set of augmenting paths that are mutually vertex-disjoint by Proposition 2. Recall that the special cost of is the weight of the edge in incident to w.

Step 4: Eliminating blocking special edges In this step, we modify iteratively. We start by setting . At each iteration we modify as follows. We check whether there exists a special edge that is blocking in . If yes, then notice that is not matched in , because is special and thus . Let P be the path of containing . We modify by truncating P to its subpath between its starting vertex and , and appending to it the edge . This way, becomes an edge of the matching . The iteration stops when there is no special edge blocking . Note that once a special edge ceases to be blocking in , it cannot become blocking again during this process, so the algorithm performs at most iterations. For each , let denote the augmenting path in covering w at the end of Step 4; we define and output the matching .

This completes the description of the algorithm; we now provide its analysis.

Lemma 2

is a feasible matching for I, and the number of blocking pairs for is at most the weight of .

Proof

Consider the situation when the iteration in Step 4 deals with a special edge blocking in . Notice that since is the second woman in (by the definition of a special edge), and since is blocking in , we know that is unmatched in , that is, does not lie on any of the augmenting paths in . From this follows that the augmenting paths in , and hence in , remain mutually vertex-disjoint. Therefore, is indeed a matching. As it covers , and no augmenting path ends at a woman in , matching is feasible.

Clearly, Step 4 ensures that there are no blocking special edges in . Note that when the algorithm modifies for some , at most one new blocking pair may arise with respect to , and from the stability of M and Proposition 2 it follows that such an edge must be a special edge (incident to the man at which ends before its modification). This means that Step 4 gets rid of all blocking special edges without introducing any non-special blocking edges. Hence, we obtain that the cost of is at most the special cost of , for each . By Lemma 1, the number of blocking pairs that admits is at most the sum of the costs of all augmenting paths in ; this finishes the proof.

To show that our algorithm is correct and is optimal, by Lemma 2 it suffices to prove that the weight of is at most the number of blocking pairs in , where denotes an optimal solution in I. To this end, we are going to define a matching covering in whose weight is at most the number of blocking pairs in .

Clearly, contains an augmenting path covering w for each . If some ends at a man , then clearly no other path in can end at m. So let us take the matching in that includes all pairs where ends at for some . Also, we put into if does not end at a man of . Note that is indeed a matching.

It remains to show that the weight of is at most the number of blocking pairs in . By definition, the weight of is at most the sum of the special costs of the paths for every . By Lemma 1, any non-special blocking pair in remains a blocking pair in , and hence in as well. Hence, there is a matching in with weight at most the number of blocking pairs in an optimal solution, implying the correctness of our algorithm. As the algorithm runs in polynomial time, Theorem 8 follows.

By contrast to Theorem 8, if men may have preference lists of length 3, then SMC-1 (and hence SMC) is -hard even if each woman finds at most two men acceptable.

Theorem 9

SMC-1 is -hard even if and .

Proof

We give a reduction from the -hard Vertex Cover problem, asking whether the input graph G has a vertex cover of size at most k. We order the vertices of G arbitrarily, and denote the h-th neighbor of some vertex x by n(x, h) for any .

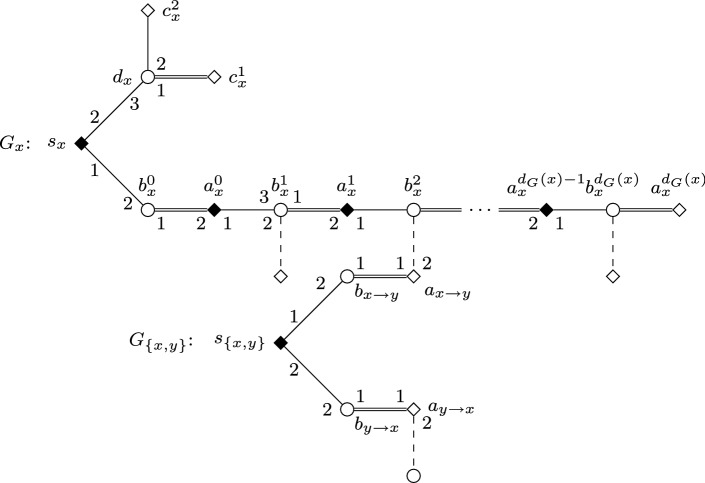

Let us construct an instance I of SMC as follows; see Fig. 4 for an illustration. For each vertex we construct a node gadget which contains women , , and , and men , and . For each edge we also construct an edge gadget involving women , and , and men and . Furthermore, there are two edges in the underlying graph connecting to and , namely and where and .

Fig. 4.

Illustration of a node gadget and an edge gadget constructed in the proof of Theorem 9. Double edges denote edges of a stable matching for I, and dashed edges are those leaving some gadget. The example depicted assumes

The preference lists of I are given in Table 4. Let the set of women with covering constraints be

and set the number of blocking pairs allowed to be . We are going to prove that I admits a feasible matching with at most blocking pairs if and only if there is a vertex cover of size k in the graph G.

Table 4.

Preference lists of women and men in the proof of Theorem 9

| where and , | |

| where , | |

| where , | |

| where x precedes y, | |

| where . |

When not stated otherwise, indices take all possible values

“”: Let M be a feasible matching with at most blocking pairs. We say that the cost of some gadget (or ) is the number of edges blocking M which are incident to some man of (or , respectively.) We will prove that the set S of vertices x for which has cost at least 2 is a vertex cover of G.

First, let us consider some x for which . In this case, both and form a blocking pair for M with , implying . Second, let us consider some x with . Since each with must be matched by M (because it is contained in ), we obtain for each such h. Hence, and form a blocking pair for M. Moreover, if the woman is unmatched in M for some y, then is also a blocking pair in M (where ), and implies a cost of at least 2 for . Therefore, we can observe that if , then must be matched by M to for each neighbor y of x in G.

However, for any , M must match either to or to (because is contained in ), which means that or . This proves that S is indeed a vertex cover for G. Moreover, the number of vertices in S can be at most k, since each with has cost at least 2, each with has cost at least 1, and the total cost of all gadgets cannot exceed our budget .

“”: Given a vertex cover S of size at most k for G, we define a matching M with the desired properties. Namely, for each we set and for each . In this case, are unmatched by M, both forming a blocking pair with . By contrast, all of the men get their first choices.

Next, for each we set , , and for each . Note that is unmatched by M, and thus forms a blocking pair with . Observe also that is not contained in any blocking pair.

Finally, for some , let us assume (since S is a vertex cover, it contains x or y). We set and . Note that gets her first choice, so it cannot be involved in a blocking pair. Although is unmatched by M, we know that it cannot form a blocking pair with where , because and hence is assigned her first choice by M. Thus, no man or woman of some edge gadget participates in a blocking pair, and therefore we obtain that the total number of blocking pairs for M is exactly .

Since M is feasible, the theorem follows.

Covering Constraints on Both Sides

Let us now investigate the complexity of SMC with covering constraints both for men and women. If we restrict the maximum length of preference lists on both sides to be at most 2, SMC becomes linear-time solvable. To see this, observe that by , the underlying graph G must be a collection of paths and cycles. Thus, we can process the connected components of G one by one. Applying dynamic programming on each component K, we can determine the minimum number of blocking pairs for any matching that is feasible for K, together with a matching for K that admits blocking pairs. If K is a path, then this can be done in a straightforward manner, traversing the edges of K one by one in linear time. If K is a cycle, then we can pick any edge e of K, guess whether it is contained in , or blocks , or neither of the two; we can then process the remainder of K (which is a path) taking into account our guess for e. To compute the minimum number of blocking pairs that a feasible matching admits in our instance, we can simply sum up the values over each connected component K of G. Hence, we arrive at the following.

Observation 2

Instances of SMC with are linear-time solvable.

Recall that the case where and is -hard by Theorem 9, even if there are no distinguished men to be covered. However, switching the roles of men and women in Theorem 8, we obtain that if there are no women to be covered, then guarantees polynomial-time solvability for SMC. This raises the natural question whether SMC with can be solved efficiently if the number of distinguished women is bounded. Next we show that this is unlikely, as the problem turns out to be -hard for .

Theorem 10

SMC is -hard, even if , and there is only one man m with .

Proof

We present a reduction from the following special case of Exact-3-Cover. We are given a set , a family of subsets of U, each having size 3, such that each element of U occurs in at most three sets of . The task is to decide whether there exists a collection of n/3 sets in whose union covers U; such a collection of subsets is called an exact cover for U. This problem is -complete [21, GT2]. We construct an equivalent instance I of SMC as follows.

The set of women in I contains the women , , , , and for each , women x and y, as well as two women for each element contained in for each . The men defined in I are , , , , and for each , a man for each , a man for each element contained in for each , plus one additional man . (The pairs form a stable matching in I.) The only distinguished woman in I is x, and the set of distinguished men is . The preferences of each person are as shown in Table 5. Note that since each subset contains three elements, and each element is contained in at most three subsets from , we get that all men except for have a preference list of length at most 3, as promised. To finish the construction, we set the number of allowed blocking pairs to be .

Table 5.

Preference lists of women and men in the proof of Theorem 10

| for , | |

| for the unique that satisfies , | |

| for and , | |

| where , | |

| where and is some fixed ordering of |

We denote by the index i for which is the h-th element in . When not stated otherwise, indices take all possible values

We claim that I admits a feasible matching with at most b blocking pairs if and only if is a “yes”-instance of Exact-3-Cover.

“”: Suppose that M is a feasible matching for I with at most b blocking pairs. Clearly, as x is distinguished, M must contain the edge . Thus, is blocking in M. Second, since is distinguished for each , we get that M matches either to or to , which in turn implies that either or blocks M, leading to m additional blocking pairs for M. Third, consider now any man , : as is distinguished, we know for some j such that contains . In this case, is also a blocking pair for M, yielding n blocking pairs of such form. Thus, if denotes the number of blocking pairs among the edges for indices i and j with , then we get . This adds up to blocking pairs so far.

Let us define the set of those edges that are incident to , , , or , but not to for some ; note that these sets are pairwise disjoint, and none of them contains any of the (possibly) blocking edges mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Let k be the number of indices j for which contains no blocking pairs for M; we call such indices (and the subsets corresponding to them) selected. The non-selected indices clearly correspond to at least blocking pairs for M (each contained in for some j).

Suppose now that j is selected. Then, since is not blocking, we get , since prefers to its partner x. This implies that , as otherwise would be blocking in M. Similarly, from this we obtain . Moreover, for each , to ensure that does not block M where is the h-th element of , we must have . Hence, must be blocking in M. Since this holds for each and each selected j, we get .

Summing up the blocking pairs identified so far, we know that M admits at least blocking pairs. Using that this must be upper-bounded by , it is easy to show that only is possible. This yields that there exist exactly n/3 selected indices, and for all such indices j all the edges for which are blocking with respect to M. Moreover, we also must have , as otherwise the number of blocking pairs would exceed b.

However, observe that for each , there must exist some j with for which the pair is blocking in M (because is distinguished), implying that for each there must exist some selected that contains . Since there are exactly n/3 selected sets in , we get that they form an exact covering of U.

“”: Suppose that is a “yes”-instance of Exact-3-Cover. Let J be the set of indices describing a solution, meaning that the subsets with form an exact covering of U; clearly, . We define as the unique index j in J for which . We define a feasible matching M for I with exactly b blocking pairs as follows (indices take all possible values, if not stated otherwise).

It is easy to check that M indeed is feasible, and the blocking pairs it admits are exactly the pairs , for each , for each , for each , and for each . This proves the lemma.

Contrasting Theorem 10, we establish fixed-parameter tractability of the case with three different parameterizations. Considering our five parameters, the relevant cases (whose tractability or intractability does not follow from our results obtained so far) are as follows, assuming throughout. Since letting the number b of blocking pairs and the number of distinguished women to be unbounded (while assuming ) results in -hardness by Theorem 9, in order to obtain fixed-parameter tractability, we need to take either b or as a parameter. However, taking only as a parameter is not likely to result in tractability, as the case is still -hard by Theorem 10. Thus we need to take either or as an additional parameter. Altogether, this results in the following parameterizations of the SMC problem, each case subject to the assumption :

taking b as the parameter,

taking as the parameter, and

taking as the parameter.

We show fixed-parameter tractability for each three of these parameterizations. The first two parameterizations can be dealt with an algorithm whose properties are stated in Theorem 11 (see also Corollary 3), while the third parameterization will be considered by Theorem 12.

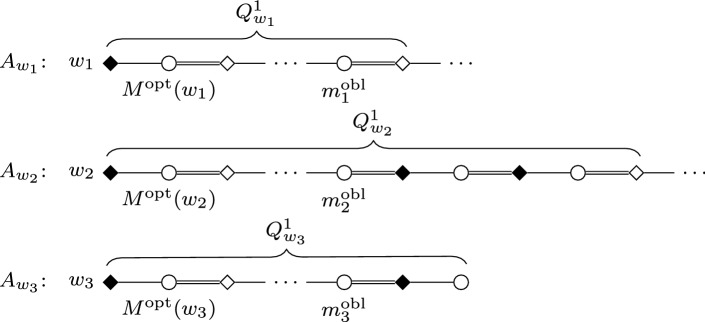

Theorem 11

There is a fixed-parameter algorithm for the special case of SMC where each woman finds at most two men acceptable (i.e., ), parameterized by the number of distinguished men and women left unmatched by some stable matching.

Let denote an optimal solution for our instance I such that contains the minimum number of edges; recall that is a fixed stable matching for I. Without loss of generality, we can further assume that there does not exist another optimal solution such that (i) has the same number of common edges with as , and (ii) for each man m, either or m prefers to .4 Indeed, as long as such a “superior” matching exists, we can simply pick that instead of , until this is no longer possible. This way, we eventually end up with an optimal matching that satisfies our requirement.

We denote by b the number of blocking pairs in .

High-Level Description Let us remark first that simply guessing the optimal partners for each woman in and then using the polynomial-time algorithm presented in Sect. 6.1 (after exchanging the roles of men and women) does not work, since that algorithm heavily relies on the assumption that we start with a stable matching. In fact, the main difficulty to overcome is that feminine and masculine augmenting paths may “interact” in the sense that certain blocking pairs introduced by a feminine augmenting path can be “eliminated” (i.e., made non-blocking again) by an appropriately chosen masculine path. Therefore, we apply the following strategy. In Phase I, we find all feminine paths (as well as all cycles) in , and in Phase II we proceed with choosing the masculine paths carefully. Note that in Phase I it does not suffice to find a cheapest set of feminine augmenting paths, since we may not be able to eliminate as many blocking pairs afterwards as it is possible after an optimal choice of feminine paths. Instead, we need to find the exact feminine augmenting paths (and cycles) present in ; this can be accomplished by guessing certain properties of .

In Phase II, the main obstacle is that we do not know which blocking edges should be eliminated in an optimal solution, nor can we guess these edges efficiently. We deal with this problem by guessing the sets of those men in whose augmenting paths in contribute to the elimination of a blocking pair; this information allows us to find these masculine paths. Finally, we apply the algorithm of Theorem 8.

For the detailed description of our algorithm, we need a couple of simple observations and some additional notation. We begin with the following implications of the fact that each woman finds at most two men acceptable.

Proposition 3

Suppose . Let and be two augmenting paths.

If and start at some through the same edge, then one of them is a subpath of the other.

If and start at different women and , respectively, and and are not disjoint, then the set of their common vertices induces a suffix of either or (or both); their first common vertex is a man.

If and are disjoint and e is an edge incident to both, then one of the paths starts or ends at a women w, and e connects w with a man on the other path.

Observations (a) and (b) of Proposition 3 immediately suggest that feminine paths are easy to find, since once we decide which edge to start with, all possible augmenting paths lead in the same direction; the only difficulty arises in deciding when to stop. Observation (c) describes the limited ways in which two augmenting path can interact; we next look closer at such interactions.

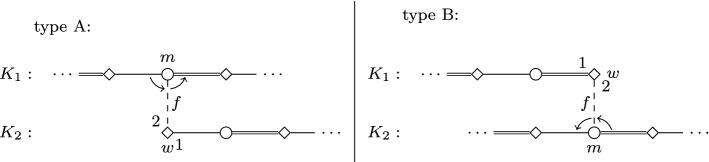

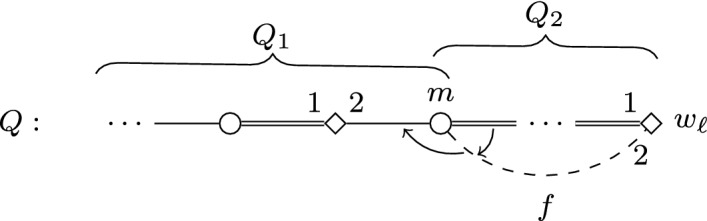

We say that an edge of G (with and ) is dependent if it connects two different connected components and of and, in addition, it holds that admits more blocking pairs than . We will say that f, and with a slight abuse of the notation, also relies on . We say that

f has type A, if w is the endpoint of (which is a path), f connects w with a man m on that prefers to w, and w to , and w is unmatched by and prefers to m;

f has type B, if w is the endpoint of (which is a path), unmatched by , and f connects w with a man m on that prefers to w, and w to .

See Fig. 5 for an illustration of the above definitions.

Fig. 5.

Illustration of a dependent edge f, running between two connected components and of where relies on . Double lines here denote edges of , single lines denote edges of , and f is drawn with a dashed line

Lemma 3

Let be the set of connected components of , and let and . Then any edge f that is blocking in but is not blocking in connects K with a connected component of H, is a dependent edge relying on K, and has either type A or type B.

Proof

Let f be an edge that blocks but does not block . Since is stable, f must have an endpoint in a connected component of H, because it blocks . However, as it ceases to be blocking in , it also must have an endpoint in K. Let w and m be the woman and the man connected by f, respectively. We distinguish now between two cases.

First, let us assume that w is contained in K. Since m is not contained in K, and w can only be connected to two men, it follows that the degree of w in K is at most (and hence exactly) 1. Since each connected component of is either a cycle or a path, this implies that K is a path with w being one of its endpoints.

Since f blocks and the partner of m under is , we know that m prefers w to . But as is stable, m must prefer to w.

Notice now that w is unmatched either in or in . However, as f blocks (where w is matched as in ) but does not block (where w is matched as in ), it must be the case that w is matched by but is unmatched in . Further, as f is not blocking in even though m prefers w to , we get that w prefers to m. This proves that f has type A.

Second, let us assume that w is contained in a connected component of H. As in the previous case, we quickly get that must be a path, with w being an endpoint of . Since f blocks , we know that w is matched by but is unmatched by . The stability of implies also that w prefers to m.

Regarding m, the fact that f blocks implies that m prefers w to . However, since f ceases to be blocking in , we get that m prefers to w. This proves that f has type B.

We are now ready to present our algorithm, which is a branching algorithm: throughout its course, we make several “guesses” for which all possibilities have to be explored. When certain guesses turn out to be trivially wrong, such guesses are discarded, and we might not explicitly mention this in the algorithm. (In Step 1, we describe such issues in detail for illustration, but later we omit them.) Phases I and II consist of Steps 1-5 and Steps 6-8, respectively.

Step 1: Guessing the first edges of feminine augmenting paths First, for each with , we guess the edge of incident to w. This results in at most possibilities, all of which must be explored. Naturally, we discard those guesses where the edges , , do not form a matching. From now on we assume that we know for each .

Additionally, we delete those edges for which and w prefers to m. Such edges are neither needed in , nor can they block any matching that contains all the edges , , guessed in this step.

Before proceeding to Step 2, we state an important lemma about augmenting paths.

Lemma 4

Each connected component of that is not a cycle is an augmenting path. Further, assume that Step 1 has already been performed, and and are connected components of such that relies on via a dependent edge f. Then

if f has type A, then is a masculine path and not a feminine path;

if f has type B, then is a feminine path and not a masculine path, and is either a cycle or a feminine path.

Proof

We begin by proving the first sentence of the lemma. Let us first suppose that Q is a connected component of that is not a cycle (thus is a path) but is not an augmenting path. The feasibility of implies that if Q has a distinguished person p as its endpoint, then p must be unmatched by . This means that Q can only be non-augmenting if neither of its endpoints is distinguished. This implies that is a feasible matching. Recall that b is the number of blocking pairs admits. If admits at most b blocking pairs as well, then this contradicts the choice of , because there are strictly less edges in than in .