Key Points

Questions

Is narrowband UV-B phototherapy associated with increased risk of skin cancer in patients with vitiligo?

Findings

In this nationwide population-based cohort study, narrowband UV-B phototherapy was not associated with an increased risk of Bowen disease, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or melanoma; however, the risk of actinic keratosis increased significantly for those who had undergone 200 sessions or more of narrowband UV-B phototherapy. For patients who had undergone extremely long-term narrowband UV-B phototherapy (≥500 sessions), the risk of skin cancer did not change.

Meaning

Narrowband UV-B phototherapy was not associated with an increase in the risk of skin cancer in patients with vitiligo and appears to be safe for patients with vitiligo.

Abstract

Importance

Narrowband UV-B (NBUVB) phototherapy has been the mainstay in the treatment of vitiligo, but its long-term safety in terms of photocarcinogenesis has not been established.

Objectives

To investigate the risks of skin cancer and precancerous lesions among patients with vitiligo undergoing NBUVB phototherapy, based on the number of NBUVB phototherapy sessions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study enrolled 60 321 patients with vitiligo 20 years or older between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2017. Patients and outcomes were identified through nationwide cohort data from the Korean national health insurance claims database, and frequency matching by age and sex was performed.

Exposures

The number of phototherapy sessions each patient received between 2008 and 2017. Patients were classified into 5 groups according to the number of phototherapy sessions (0 sessions, 20 105 patients; 1-49 sessions, 20 106 patients; 50-99 sessions, 9702 patients; 100-199 sessions, 6226 patients; and ≥200 sessions, 4182 patients). We also identifed patients who underwent at least 500 phototherapy sessions (717 patients).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes were the development of actinic keratosis, Bowen disease, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or melanoma after enrollment.

Results

Among the 60 321 patients with vitiligo in this study (33 617 women; mean [SD] age, 50.2 [14.9] years), the risks of Bowen disease (<50 sessions of phototherapy: hazard ratio [HR], 0.289 [95% CI, 0.060-1.392]; 50-99 sessions: HR, 0.603 [95% CI, 0.125-2.904]; 100-199 sessions: HR, 1.273 [95% CI, 0.329-4.924]; ≥200 sessions: HR, 1.021 [95% CI, 0.212-4.919]), nonmelanoma skin cancer (<50 sessions: HR, 0.914 [95% CI, 0.533-1.567]; 50-99 sessions: HR, 0.765 [95% CI, 0.372-1.576]; 100-199 sessions: HR, 0.960 [95% CI, 0.453-2.034]; ≥200 sessions: HR, 0.905 [95% CI, 0.395-2.073]), and melanoma (<50 sessions: HR, 0.660 [95% CI, 0.286-1.526]; 50-99 sessions: HR, 0.907 [95% CI, 0.348-2.362]; 100-199 sessions: HR, 0.648 [95% CI, 0.186-2.255]; ≥200 sessions: HR, 0.539 [95% CI, 0.122-2.374]) did not increase after phototherapy. The risk of actinic keratosis increased significantly for those who had undergone 200 or more NBUVB phototherapy sessions (HR, 2.269 [95% CI, 1.530-3.365]). A total of 717 patients with vitiligo underwent at least 500 sessions of NBUVB phototherapy; their risks of nonmelanoma skin cancer and melanoma were no greater than those of the patients who did not undergo NBUVB phototherapy (nonmelanoma skin cancer: HR, 0.563 [95% CI, 0.076-4.142]; melanoma: HR, not applicable).

Conclusions and Relevance

Our results suggest that long-term NBUVB phototherapy is not associated with an increased risk of skin cancer in patients with vitiligo and that NBUVB phototherapy may be considered a safe treatment.

This cohort study investigates the risks of skin cancer and premalignant skin lesions among patients with vitiligo undergoing narrowband UV-B phototherapy, based on the number of narrowband UV-B phototherapy sessions.

Introduction

Phototherapy has played a major role in the treatment of various skin diseases, including psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and vitiligo.1,2 Given the chronic and relapsing nature of such skin diseases, patients often receive multiple courses of phototherapy during their lives. There have been concerns about whether repetitive exposure to UV light during long-term phototherapy would increase the risk of photocarcinogenesis3 because UV is well known to cause nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) and melanoma.3,4 Among the various types of phototherapy, psoralen plus UV-A (PUVA) phototherapy has been found to be associated with an increased risk of skin cancers,5,6,7 but it is not currently widely used. The widespread use of indoor tanning has raised concerns about an increased risk of skin cancer and many dermatologists are strongly opposed to indoor tanning.8 However, to our knowledge, the risk of skin cancer after long-term narrowband UV-B (NBUVB) phototherapy, which is now widely used for therapeutic purposes in dermatology, has not been fully investigated.5,9,10

Vitiligo is a common chronic depigmenting skin disorder caused by loss of melanocytes that affects 1% of the population worldwide.11 In the absence of approved medication, phototherapy has been the mainstay of treatment for patients with vitiligo.12 Narrowband UV-B phototherapy has now replaced PUVA phototherapy because it is more effective, does not require ingestion of a photosensitizing agent, and shows fewer adverse events than PUVA.13 Because NBUVB phototherapy is usually performed 2 or 3 times weekly for at least 6 to 12 months to achieve sufficient repigmentation in patients with vitiligo,1,2 the cumulative exposure to phototherapy could be large.

We performed a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study to investigate the risks of skin cancer and precancerous lesions according to the number of NBUVB phototherapy sessions undergone by patients with vitiligo. We also assessed the risks of skin cancer and precancerous lesions in patients undergoing extremely long-term NBUVB phototherapy (≥500 sessions).

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

In this nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study, we used information entered into the Korean national health insurance claims database between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2017. Korea has one of the largest national health insurance systems worldwide, covering 98% of Korea’s 50 million people and paying for all services provided by the Korean national health insurance and medical aid programs.14 The study was approved by the St Vincent’s Hospital Institutional Review Board, which waived patient consent because the data were deidentified.

Study Population

We first identified all patients 20 years of age or older who saw a physician at least 4 times and received a principal diagnosis of vitiligo according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (code L80) between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2017. To eliminate any potential effect of previous sessions of NBUVB phototherapy, we excluded patients who received phototherapy during 2007 (a 1-year washout period). We also excluded those with a diagnosis of actinic keratosis (AK), Bowen disease (BD), NMSC, or melanoma prior to receiving a diagnosis of vitiligo or undergoing their first phototherapy session.

Number of Phototherapy Sessions

We counted the number of phototherapy sessions received by each patient between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2017, by retrieving billing claims for phototherapy during the entire study period. Given that psoralen was not available in Korea during this time, NBUVB was the only type of phototherapy administered. We categorized patients with vitiligo into those who had not received phototherapy (no NBUVB group), those who had received less than 50 sessions (NBUVB <50 group), and those who had undergone 50 or more sessions (NBUVB ≥50 group). Based on the NBUVB ≥50 group, we reestablished the other groups using 1:1 frequency matching according to age and sex. Finally, we further stratified the NBUVB ≥50 group into the following 3 small groups: patients who received 50 to 99 treatment sessions (NBUVB 50-99 group), patients who received 100 to 199 treatment sessions (NBUVB 100-199 group), and patients who received 200 or more treatment sessions (NBUVB ≥200 group).

Outcomes of Interest

The outcomes of interest were the development of AK, BD, NMSC, or melanoma after enrollment until the end of study period. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and melanoma were defined when a patient with vitiligo consulted a physician, and the principal diagnosis was coded C44 (NMSC) or C43 or D03 (melanoma). The Korean government provides financial support based on the principal diagnosis code to those with a diagnosis of malignant neoplasms; diagnoses of BD, NMSC, and melanoma are highly reliable.15 Actinic keratosis and BD were defined when a patient with vitiligo visited a physician at least twice during the study period and was assigned diagnostic codes of L570 (AK) or D04 (BD); this minimized the likelihood of misclassification.

Subgroup Analyses

We performed subgroup analysis by sex and age (20-49 or ≥50 years). We also analyzed patients with vitiligo who underwent 500 or more NBUVB sessions to investigate the risk of skin cancer and premalignant skin lesions after extremely long-term NBUVB treatment.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated the incidences of AK, BD, NMSC, and melanoma per 10 000 person-years in each group and subgroup. We used univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models to explore the association of NBUVB phototherapy with the risks of skin cancer and precancerous lesions after adjusting for confounding variables (age and sex). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc). All P values were from 2-sided tests and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

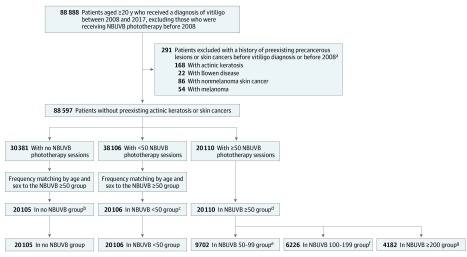

After excluding those who had received NBUVB phototherapy before 2008, we first identified a total of 88 888 patients with vitiligo who were 20 years of age or older who were treated between 2008 and 2017 (Figure). After further excluding those with a diagnosis of precancerous skin lesions or skin cancers prior to the diagnosis of vitiligo, 88 597 patients remained, of whom 30 381 received no phototherapy, 38 106 received less than 50 sessions, and 20 110 received 50 or more sessions. After 1:1 frequency matching by age and sex of those who received 50 or more sessions, we formed a no NBUVB group (n = 20 105), an NBUVB <50 group (n = 20 106), and an NBUVB ≥50 group (n = 20 110) (Table 1). We further stratified the NBUVB ≥50 group into 3 groups: patients who received 50 to 99 sessions (n = 9702), patients who received 100 to 199 sessions (n = 6226), and patients who received 200 or more sessions (n = 4182), as already described.

Figure. Schematic Diagram Showing the Enrollment and Categorization of Patients With Vitiligo According to the Number of Narrowband UV-B (NBUVB) Sessions of Phototherapy.

aThere were patients who had more than 1 case of precancerous skin lesions or skin cancer.

bPatients who had not received phototherapy.

cPatients who had received less than 50 sessions.

dPatients who had received 50 or more sessions.

ePatients who had received 50 to 99 sessions.

fPatients who had received 100 to 199 sessions.

gPatients who had received 200 or more sessions.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of Patients in Group | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 60 321) | No NBUVB (n = 20 105)a | NBUVB <50 (n = 20 106)b | NBUVB 50-99 (n = 9702)c | NBUVB 100-199 (n = 6226)d | NBUVB ≥200 (n = 4182)e | ||

| Age group, y | |||||||

| 20-29 | 6357 (10.5) | 2119 (10.5) | 2119 (10.5) | 1138 (11.7) | 644 (10.3) | 337 (8.1) | <.001 |

| 30-39 | 9069 (15.0) | 3021 (15.0) | 3024 (15.0) | 1511 (15.6) | 966 (15.5) | 547 (13.1) | |

| 40-49 | 12 351 (20.5) | 4117 (20.5) | 4117 (20.5) | 1945 (20.0) | 1251 (20.1) | 921 (22.0) | |

| 50-59 | 15 215 (25.2) | 5071 (25.2) | 5072 (25.2) | 2418 (24.9) | 1559 (25.0) | 1095 (26.2) | |

| 60-69 | 11 112 (18.4) | 3704 (18.4) | 3704 (18.4) | 1729 (17.8) | 1150 (18.5) | 825 (19.7) | |

| 70-79 | 5337 (8.8) | 1779 (8.8) | 1779 (8.8) | 835 (8.6) | 558 (9.0) | 386 (9.2) | |

| ≥80 | 880 (1.5) | 294 (1.5) | 291 (1.4) | 126 (1.3) | 98 (1.6) | 71 (1.7) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 26 704 (44.3) | 8899 (44.3) | 8901 (44.3) | 4237 (43.7) | 2768 (44.5) | 1899 (45.4) | .45 |

| Female | 33 617 (55.7) | 11 206 (55.7) | 11 205 (55.7) | 5465 (56.3) | 3458 (55.5) | 2283 (54.6) | |

Abbreviation: NBUVB, narrowband UV-B.

Patients who had not received phototherapy.

Patients who had received less than 50 sessions.

Patients who had received 50 to 99 sessions.

Patients who had received 100 to 199 sessions.

Patients who had received 200 or more sessions.

AK After Long-term NBUVB Phototherapy

The AK incidence rate was 14.2 per 10 000 person-years (95% CI, 10.2-19.4 per 10 000 person-years) in the NBUVB ≥200 group, whereas it was 6.1 per 10 000 person-years (95% CI, 4.7-7.7 per 10 000 person-years) in the no NBUVB group (Table 2). The risk of AK was significantly increased in the NBUVB ≥200 group (hazard ratio [HR], 2.269 [95% CI, 1.530-3.365]) compared with the no NBUVB group but was not significantly increased in the NBUVB <50 group (HR, 0.940 [95% CI, 0.662-1.336]), the NBUVB 50-99 group (HR, 0.751 [95% CI, 0.467-1.209]), or the NBUVB 100-199 group (HR, 1.413 [95% CI, 0.921-2.168]). For young patients (aged 20-49 years), the AK risk was increased significantly in both the NBUVB 100-199 group (HR, 5.759 [95% CI, 1.054-31.451]) and the NBUVB ≥200 group (HR, 20.529 [95% CI, 4.488-93.915) (Table 3), but this increased risk was not seen in older patients (aged ≥50 years). No between-sex difference was apparent.

Table 2. Risk of Skin Cancer in Patients With Vitiligo After Long-term NBUVB Phototherapy.

| Group | Incidence Rate (95% CI)a | Events, No. | Population, No. | No. of Person-Years | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b | P Value | |||||

| Actinic keratosis | ||||||||

| No NBUVBc | 6.1 (4.7-7.7) | 65 | 20 105 | 106 910 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| NBUVB <50d | 5.6 (4.3-7.2) | 60 | 20 106 | 106 578 | 0.920 (0.648-1.307) | .64 | 0.940 (0.662-1.336) | .73 |

| NBUVB 50-99e | 4.3 (2.7-6.4) | 23 | 9702 | 53 732 | 0.701 (0.435-1.127) | .14 | 0.751 (0.467-1.209) | .24 |

| NBUVB 100-199f | 8.4 (5.7-11.9) | 31 | 6226 | 36 888 | 1.379 (0.899-2.115) | .14 | 1.413 (0.921-2.168) | .11 |

| NBUVB ≥200g | 14.2 (10.2-19.4) | 40 | 4182 | 28 106 | 2.359 (1.590-3.499) | <.001 | 2.269 (1.530-3.365) | <.001 |

| Bowen disease | ||||||||

| No NBUVBc | 0.7 (0.3-1.3) | 7 | 20 105 | 107 110 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| NBUVB <50d | 0.2 (0-0.7) | 2 | 20 106 | 106 748 | 0.283 (0.059-1.360) | .12 | 0.289 (0.060-1.392) | .12 |

| NBUVB 50-99e | 0.4 (0-1.3) | 2 | 9702 | 53 795 | 0.560 (0.116-2.694) | .47 | 0.603 (0.125-2.904) | .53 |

| NBUVB 100-199f | 0.8 (0.2-2.4) | 3 | 6226 | 36 992 | 1.219 (0.315-4.714) | .78 | 1.273 (0.329-4.924) | .73 |

| NBUVB ≥200g | 0.7 (0.1-2.6) | 2 | 4182 | 28 260 | 1.068 (0.221-5.146) | .94 | 1.021 (0.212-4.919) | .98 |

| Nonmelanoma skin cancer | ||||||||

| No NBUVBc | 2.6 (1.7-3.8) | 28 | 20 105 | 107 025 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| NBUVB <50d | 2.3 (1.5-3.5) | 25 | 20 106 | 106 674 | 0.889 (0.518-1.525) | .67 | 0.914 (0.533-1.567) | .74 |

| NBUVB 50-99e | 1.9 (0.9-3.4) | 10 | 9702 | 53 781 | 0.705 (0.343-1.452) | .34 | 0.765 (0.372-1.576) | .47 |

| NBUVB 100-199f | 2.4 (1.1-4.6) | 9 | 6226 | 36 960 | 0.924 (0.436-1.959) | .84 | 0.960 (0.453-2.034) | .91 |

| NBUVB ≥200g | 2.5 (1.0-5.1) | 7 | 4182 | 28 233 | 0.940 (0.410-2.153) | .88 | 0.905 (0.395-2.073) | .81 |

| Melanoma | ||||||||

| No NBUVBc | 1.3 (0.7-2.2) | 14 | 20 105 | 107 090 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| NBUVB <50d | 0.8 (0.4-1.6) | 9 | 20 106 | 106 736 | 0.649 (0.281-1.500) | .31 | 0.660 (0.286-1.526) | .33 |

| NBUVB 50-99e | 1.1 (0.4-2.4) | 6 | 9702 | 53 772 | 0.862 (0.331-2.243) | .76 | 0.907 (0.348-2.362) | .84 |

| NBUVB 100-199f | 0.8 (0.2-2.4) | 3 | 6226 | 36 991 | 0.632 (0.182-2.200) | .47 | 0.648 (0.186-2.255) | .50 |

| NBUVB ≥200g | 0.7 (0.1-2.6) | 2 | 4182 | 28 254 | 0.559 (0.127-2.460) | .44 | 0.539 (0.122-2.374) | .41 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NBUVB, narrowband UV-B.

Incidence rate per 10 000 person-years.

Adjusted by age and sex.

Patients who had not received phototherapy.

Patients who had received less than 50 sessions.

Patients who had received 50 to 99 sessions.

Patients who had received 100 to 199 sessions.

Patients who had received 200 or more sessions.

Table 3. Subgroup Analyses of the Association of Risk of Skin Cancer With Long-term NBUVB Phototherapy by Sex and Age.

| Group | Male | Female | Aged 20-49 y | Aged ≥50 y | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P Value | |

| Actinic keratosis | ||||||||

| No NBUVBb | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| NBUVB <50c | 1.353 (0.768-2.383) | .30 | 0.744 (0.472-1.174) | .20 | 1.953 (0.358-10.665) | .44 | 0.910 (0.635-1.305) | .61 |

| NBUVB 50-99d | 0.940 (0.414-1.974) | .80 | 0.678 (0.372-1.238) | .21 | 1.911 (0.269-13.573) | .52 | 0.717 (0.437-1.175) | .19 |

| NBUVB 100-199e | 1.937 (0.970-3.871) | .06 | 1.158 (0.669-2.004) | .60 | 5.759 (1.054-31.451) | .04 | 1.276 (0.813-2.004) | .29 |

| NBUVB ≥200f | 2.638 (1.360-5.120) | .004 | 2.099 (1.284-3.431) | .003 | 20.529 (4.488-93.915) | <.001 | 1.747 (1.131-2.699) | .01 |

| Bowen disease | ||||||||

| No NBUVBb | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| NBUVB <50c | 0.335 (0.035-3.221) | .34 | 0.255 (0.028-2.281) | .22 | 0 (NA) | .99 | 0.339 (0.068-1.680) | .19 |

| NBUVB 50-99d | 0.701 (0.073-6.741) | .76 | 0.531 (0.059-4.753) | .57 | 0 (NA) | .99 | 0.710 (0.143-3.517) | .68 |

| NBUVB 100-199e | 2.039 (0.340-12.211) | .44 | 0.708 (0.079-6.340) | .76 | 0 (NA) | .99 | 1.492 (0.373-5.967) | .57 |

| NBUVB ≥200f | 2.302 (0.384-13.803) | .36 | 0 (NA) | >.99 | 0 (NA) | .99 | 1.184 (0.239-5.872) | .84 |

| Nonmelanoma skin cancer | ||||||||

| No NBUVBb | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| NBUVB <50c | 0.744 (0.299-1.849) | .52 | 1.025 (0.523-2.007) | .94 | 0.973 (0.137-6.910) | .98 | 0.907 (0.518-1.590) | .73 |

| NBUVB 50-99d | 0.972 (0.338-2.797) | .96 | 0.630 (0.233-1.709) | .37 | 1.899 (0.267-13.492) | .52 | 0.664 (0.301-1.468) | .31 |

| NBUVB 100-199e | 1.733 (0.640-4.688) | .28 | 0.498 (0.146-1.700) | .27 | 1.377 (0.125-15.199) | .79 | 0.924 (0.418-2.042) | .85 |

| NBUVB ≥200f | 1.639 (0.569-4.722) | .36 | 0.430 (0.099-1.863) | .26 | 0 (NA) | .99 | 0.976 (0.424-2.250) | .96 |

| Melanoma | ||||||||

| No NBUVBb | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| NBUVB <50c | 0.635 (0.208-1.941) | .43 | 0.695 (0.196-2.467) | .57 | 0.976 (0.197-4.835) | .98 | 0.572 (0.211-1.547) | .27 |

| NBUVB 50-99d | 0.784 (0.208-2.954) | .72 | 1.076 (0.269-4.313) | .92 | 0.670 (0.070-6.444) | .73 | 0.993 (0.345-2.860) | .99 |

| NBUVB 100-199e | 0.382 (0.048-3.055) | .36 | 0.995 (0.201-4.937) | >.99 | 0 (NA) | .99 | 0.840 (0.234-3.015) | .79 |

| NBUVB ≥200f | 0.468 (0.059-3.748) | .51 | 0.631 (0.076-5.248) | .67 | 1.283 (0.133-12.371) | .83 | 0.336 (0.043-2.605) | .30 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; NBUVB, narrowband UV-B.

Adjusted by age and sex.

Patients who had not received phototherapy.

Patients who had received less than 50 sessions.

Patients who had received 50 to 99 sessions.

Patients who had received 100 to 199 sessions.

Patients who had received 200 or more sessions.

NMSC After Long-term NBUVB Phototherapy

Of the 60 321 patients with vitiligo enrolled in this study, we observed 16 cases of BD and 79 cases of NMSC during the study period (Table 2). The incidence rates did not differ among the groups, and the HR did not increase with the number of NBUVB sessions for NMSC (<50 sessions of phototherapy: HR, 0.914 [95% CI, 0.533-1.567]; 50-99 sessions: HR, 0.765 [95% CI, 0.372-1.576]; 100-199 sessions: HR, 0.960 [95% CI, 0.453-2.034]; ≥200 sessions: HR, 0.905 [95% CI, 0.395-2.073]) or for BD (<50 sessions: HR, 0.289 [95% CI, 0.060-1.392]; 50-99 sessions: HR, 0.603 [95% CI, 0.125-2.904]; 100-199 sessions: HR, 1.273 [95% CI, 0.329-4.924]; ≥200 sessions: HR, 1.021 [95% CI, 0.212-4.919]). Subgroup analyses by age and sex revealed no differences in either BD or NMSC incidence (Table 3).

Melanoma After Long-term NBUVB Phototherapy

During the study period, 34 cases of melanoma were identified among the enrolled patients, but the risk of melanoma did not increase with the number of NBUVB sessions (<50 sessions of phototherapy: HR, 0.660 [95% CI, 0.286-1.526]; 50-99 sessions: HR, 0.907 [95% CI, 0.348-2.362]; 100-199 sessions: HR, 0.648 [95% CI, 0.186-2.255]; ≥200 sessions: HR, 0.539 [95% CI, 0.122-2.374]) (Table 2). Subgroup analyses by age and sex also revealed no increase in melanoma after NBUVB phototherapy (Table 3).

Skin Cancer Risk After Extremely Long-term NBUVB Phototherapy

We identified 717 patients with vitiligo who underwent 500 or more sessions of NBUVB treatment. Among those 717 patients, we observed 7 cases of AK (incidence, 12.6 per 10 000 person-years [95% CI, 5.1-25.9 per 10 000 person-years]), 1 case of BD (1.8 per 10 000 person-years [95% CI, 0-10.0 per 10 000 person-years]), and 1 case of NMSC (1.8 per 10 000 person-years [95% CI, 0-10.0 per 10 000 person-years]) (Table 4). Multivariable analysis revealed that extremely long-term NBUVB treatment (≥500 sessions) was not associated with a significant increase in the risk of AK, BD, NMSC, or melanoma compared with the no NBUVB group.

Table 4. Association of Risk of Skin Cancer With Extremely Long-term NBUVB Phototherapy in Patients With Vitiligo.

| Group | Incidence Rate (95% CI)a | Events, No. | Population, No. | No. of Person-Years | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b | P Value | |||||

| Actinic keratosis | ||||||||

| No NBUVBc | 6.1 (4.7-7.7) | 65 | 20 105 | 106 910 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| NBUVB ≥500d | 12.6 (5.1-25.9) | 7 | 717 | 5565 | 2.104 (0.963-4.595) | .06 | 1.739 (0.796-3.799) | .17 |

| Bowen disease | ||||||||

| No NBUVBc | 0.7 (0.3-1.3) | 7 | 20 105 | 107 110 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| NBUVB ≥500d | 1.8 (0-10.0) | 1 | 717 | 5587 | 2.961 (0.362-24.217) | .31 | 2.520 (0.308-20.592) | .39 |

| Nonmelanoma skin cancer | ||||||||

| No NBUVBc | 2.6 (1.7-3.8) | 28 | 20 105 | 107 025 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| NBUVB ≥500d | 1.8 (0-10.0) | 1 | 717 | 5585 | 0.668 (0.091-4.921) | .69 | 0.563 (0.076-4.142) | .57 |

| Melanoma | ||||||||

| No NBUVBc | 1.3 (0.7-2.2) | 14 | 20 105 | 107 090 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| NBUVB ≥500d | 0.0 (0-3.7) | 0 | 717 | 5588 | 0 (NA) | .99 | 0 (NA) | .99 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; NBUVB, narrowband UV-B.

Incidence rate per 10 000 person-years.

Adjusted by age and sex.

Patients who had not received phototherapy.

Patients who had received 500 or more sessions.

Discussion

In this 10-year nationwide retrospective cohort study, we found that long-term NBUVB phototherapy was not associated with an increased risk of NMSC or melanoma for patients with vitiligo, but a significant increased risk of AK was associated with patients who underwent 200 or more sessions of NBUVB phototherapy. To our knowledge, few studies have explored the risk of skin cancer after NBUVB phototherapy in patients with vitiligo.16 A Dutch cohort study that enrolled 1307 patients with vitiligo found that the risks of NMSC and melanoma did not increase among patients with vitiligo who underwent PUVA or NBUVB phototherapy and that the risks were not associated with the number of sessions.17 On the other hand, an Italian cohort study of 10 040 patients with vitiligo found the increased risks of NMSC and melanoma among those who received phototherapy.18 However, both studies included patients undergoing either PUVA or NBUVB phototherapy; the risks posed by NBUVB alone were not presented. A UK cohort study found no significant association between NBUVB phototherapy and the risk of melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma in 3867 patients who received NBUVB phototherapy.10 However, most of the enrolled patients had psoriasis; any risk specific for patients with vitiligo was not assessed. A recent population-based cohort study of 16 575 Taiwanese patients with psoriasis found no difference in the overall cumulative incidences of skin cancers between those receiving short-term (<90 sessions) and those receiving long-term (≥90 sessions) NBUVB phototherapy, although a no-phototherapy group was not included.19 In our study, we enrolled 60 321 patients with vitiligo and found no association between increased risk of BD, NMSC, or melanoma and long-term NBUVB phototherapy (≥200 sessions). In addition, we observed no association between increased risk of skin cancer and extremely long-term NBUVB phototherapy (≥500 sessions). Our data suggest that NBUVB phototherapy is safe for patients with vitiligo in terms of photocarcinogenesis.

The risk of skin cancer associated with indoor tanning has become a concern.8 One meta-analysis found that indoor tanning was associated with an increased risk of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma.20 However, NBUVB phototherapy differs from indoor tanning in many ways. First, NBUVB phototherapy uses an NBUVB ray with a wavelength of approximately 311 nm, whereas indoor tanning uses the UV-A ray that is used in PUVA phototherapy.21 UV-A radiation induces genetic damage and creates reactive oxygen species that damage the cell membrane and negatively affect intracellular signaling, ultimately promoting tumor development.22 Furthermore, UV-A penetrates more deeply into the skin than does UV-B, thus potentially triggering malignant changes in stem cells of the basal epidermal layer.23 Second, the level of UV-A radiation delivered by a tanning bed may be much greater than that of NBUVB phototherapy; the minimal erythemal dose of UV-A is almost 1000-fold higher than that of UV-B. Thus, the skin cancer risks associated with NBUVB phototherapy and indoor tanning may differ.

Patients with vitiligo may also benefit from enhanced immune surveillance of latent skin cancers.16,24 Cohort studies have shown that the risk of skin cancer is lower in those with vitiligo than in those without vitiligo.17,18 Moreover, a previous cohort study found that the overall risk of internal malignant neoplasms was lower in patients with vitiligo compared with matched healthy controls.25 A recent study found that the genetic loci associated with vitiligo have an inverse association with the risk of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma.26 It was suggested that genetic variations in patients with vitiligo increased resistance to malignant neoplasms or immune activity in general.26 Thus, we postulate that the autoimmune nature of vitiligo may provide some protection against possible photocarcinogenesis as a result of long-term NBUVB phototherapy.

A significant increase in the overall risk of AK was associated with 200 or more NBUVB sessions (HR, 2.269 [95% CI, 1.530-3.365]) as well as 100 to 199 sessions in the younger subgroup (20-49 years) (HR, 5.759 [95% CI, 1.054-31.451]). However, the risks of NMSC and melanoma were not increased in parallel in any subgroup, although AK is a precancerous lesion and can be a marker of development of NMSCs.27,28 Multiple factors, such as long-term UV radiation or heat exposure, environmental carcinogens, viral infection, and immunosuppression, have been reported to predispose individuals to the development of squamous cell carcinoma29; many predisposing factors work together for carcinogenesis. In contrast, the increased immune response of patients with vitiligo may hinder the progression of AK to squamous cell carcinoma.26,30 Moreover, based on the results of our study and other epidemiologic studies,10,19 we speculate that the carcinogenicity of NBUVB phototherapy may be less than that of sunlight or indoor tanning. Also, regular skin examinations by a dermatologist during phototherapy may prevent the progression of AK to skin cancer by detecting AK early. This surveillance is not usually the case in indoor tanning facilities operated by nonmedical personnel. However, considering the long latency period for the development of skin cancer even after stopping phototherapy, the 10-year follow-up may not be enough to make conclusions. Longer observational studies will be needed to confirm our findings.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study had several strengths. First, we enrolled a large number of patients from the nationwide national health insurance claims database and assessed the risk of skin cancer over 10 years. Second, we retrieved detailed unbiased information on NBUVB phototherapy and the development of skin cancer; the Korean national health insurance system includes health care data on all Korean residents. Finally, we enrolled patients with vitiligo only, thereby minimizing study heterogeneity.

Our study also had certain limitations. First, we lacked detailed information on vitiligo (activity, severity, and subtype), the characteristics of phototherapy (dose of each treatment), and the confounding factors that might have been associated with development of skin cancer (such as sun exposure and use of sunblock, smoking status, and use of systemic or topical immunosuppressive drugs). Second, we lacked data on phototherapy prior to 2007, although we established a 1-year washout period. Third, the exclusion of the patients with a prior history of skin cancer and precancerous lesion could bias the results. However, dermatologists tend not to prescribe phototherapy to patients at a high risk of skin cancer, and our findings would not be applicable to such individuals. Fourth, it could be difficult to generalize the results directly to individuals of other races/ethnicities. However, we found the relative risks according to the number of phototherapy sessions among individuals of the same race/ethnicity; these findings could be applicable to individuals of other races/ethnicities. More research on the use of phototherapy for individuals of other races/ethnicities with vitiligo is required to confirm our findings. Fifth, the demonstration of an increased risk of AK in patients undergoing 200 or more sessions of NBUVB phototherapy will require long-term study to determine the significance of this finding.

Conclusions

We found that long-term NBUVB phototherapy was not associated with an increased risk of NMSC or melanoma in patients with vitiligo, whereas an increased risk of AK was associated with undergoing 200 or more sessions of NBUVB phototherapy. The risk of skin cancer was also not associated with extremely long-term NBUVB phototherapy (≥500 sessions). Our data suggested that NBUVB phototherapy appears to be safe for patients with vitiligo in terms of the development of skin cancer. Further studies are needed for individuals of different races/ethnicities and patients with other skin diseases.

References

- 1.Mohammad TF, Al-Jamal M, Hamzavi IH, et al. . The Vitiligo Working Group recommendations for narrowband ultraviolet B light phototherapy treatment of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(5):879-888. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae JM, Jung HM, Hong BY, et al. . Phototherapy for vitiligo: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(7):666-674. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kozma B, Eide MJ. Photocarcinogenesis: an epidemiologic perspective on ultraviolet light and skin cancer. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32(3):301-313, viii. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valejo Coelho MM, Matos TR, Apetato M. The dark side of the light: mechanisms of photocarcinogenesis. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(5):563-570. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. . Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 3):22-31. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nijsten TE, Stern RS. The increased risk of skin cancer is persistent after discontinuation of psoralen+ultraviolet A: a cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121(2):252-258. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12350.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valejo Coelho MM, Apetato M. The dark side of the light: phototherapy adverse effects. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(5):556-562. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrucci LM, Vogel RI, Cartmel B, Lazovich D, Mayne ST. Indoor tanning in businesses and homes and risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer in 2 US case-control studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(5):882-887. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee E, Koo J, Berger T. UVB phototherapy and skin cancer risk: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(5):355-360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hearn RM, Kerr AC, Rahim KF, Ferguson J, Dawe RS. Incidence of skin cancers in 3867 patients treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(4):931-935. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08776.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, van Geel N. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386(9988):74-84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60763-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodrigues M, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, Pandya AG, Harris JE; Vitiligo Working Group . Current and emerging treatments for vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(1):17-29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westerhof W, Nieuweboer-Krobotova L. Treatment of vitiligo with UV-B radiation vs topical psoralen plus UV-A. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(12):1525-1528. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1997.03890480045006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park KY, Kwon HJ, Wie JH, et al. . Pregnancy outcomes in patients with vitiligo: a nationwide population-based cohort study from Korea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(5):836-842. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang S, Kim HS, Choi ES, Han I. Incidence and treatment pattern of extremity soft tissue sarcoma in Korea, 2009-2011: a nationwide study based on the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service Database. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47(4):575-582. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodrigues M. Skin cancer risk (nonmelanoma skin cancers/melanoma) in vitiligo patients. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(2):129-134. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teulings HE, Overkamp M, Ceylan E, et al. . Decreased risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with vitiligo: a survey among 1307 patients and their partners. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(1):162-171. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paradisi A, Tabolli S, Didona B, Sobrino L, Russo N, Abeni D. Markedly reduced incidence of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer in a nonconcurrent cohort of 10,040 patients with vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(6):1110-1116. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.07.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin TL, Wu CY, Chang YT, et al. . Risk of skin cancer in psoriasis patients receiving long-term narrowband ultraviolet phototherapy: results from a Taiwanese population-based cohort study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2019;35(3):164-171. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colantonio S, Bracken MB, Beecker J. The association of indoor tanning and melanoma in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):847-857. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilsen LT, Aalerud TN, Hannevik M, Veierød MB. UVB and UVA irradiances from indoor tanning devices. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2011;10(7):1129-1136. doi: 10.1039/c1pp05029j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Gruijl FR. Photocarcinogenesis: UVA vs UVB. Methods Enzymol. 2000;319:359-366. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(00)19035-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agar NS, Halliday GM, Barnetson RS, Ananthaswamy HN, Wheeler M, Jones AM. The basal layer in human squamous tumors harbors more UVA than UVB fingerprint mutations: a role for UVA in human skin carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(14):4954-4959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401141101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feily A, Pazyar N. Why vitiligo is associated with fewer risk of skin cancer? providing a molecular mechanism. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303(9):623-624. doi: 10.1007/s00403-011-1165-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bae JM, Chung KY, Yun SJ, et al. . Markedly reduced risk of internal malignancies in patients with vitiligo: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(11):903-911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu W, Amos CI, Lee JE, Wei Q, Sarin KY, Han J; 23andMe Research Team . Inverse relationship between vitiligo-related genes and skin cancer risk. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(9):2072-2075. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.03.1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. Progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma revisited: clinical and treatment implications. Cutis. 2011;87(4):201-207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandez Figueras MT. From actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma: pathophysiology revisited. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(suppl 2):5-7. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagarajan P, Asgari MM, Green AC, et al. . Keratinocyte carcinomas: current concepts and future research priorities. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(8):2379-2391. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin Y, Birlea SA, Fain PR, et al. . Variant of TYR and autoimmunity susceptibility loci in generalized vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1686-1697. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]