Key Points

Question

Are functional, cognitive, and psychological measures that are grounded in geriatric assessment associated with 1-year mortality in older adults after major surgery?

Findings

In this cohort study, 17% of participants who underwent major surgery died within 1 year. Functional, cognitive, and psychological measures were significantly associated with mortality.

Meaning

Specific measures, such as preoperative function, cognition, and psychological well-being, may need to be incorporated into the preoperative assessment to enhance surgical decision-making and patient counseling.

Abstract

Importance

More older adults are undergoing major surgery despite the greater risk of postoperative mortality. Although measures, such as functional, cognitive, and psychological status, are known to be crucial components of health in older persons, they are not often used in assessing the risk of adverse postoperative outcomes in older adults.

Objective

To determine the association between measures of physical, cognitive, and psychological function and 1-year mortality in older adults after major surgery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective analysis of a prospective cohort study of participants 66 years or older who were enrolled in the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study and underwent 1 of 3 types of major surgery.

Exposures

Major surgery, including abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, coronary artery bypass graft, and colectomy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Our outcome was mortality within 1 year of major surgery. Our primary associated factors included functional, cognitive, and psychological factors: dependence in activities of daily living (ADL), dependence in instrumental ADL, inability to walk several blocks, cognitive status, and presence of depression. We adjusted for other demographic and clinical predictors.

Results

Of 1341 participants, the mean (SD) participant age was 76 (6) years, 737 (55%) were women, 99 (7%) underwent abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, 686 (51%) coronary artery bypass graft, and 556 (42%) colectomy; 223 (17%) died within 1 year of their operation. After adjusting for age, comorbidity burden, surgical type, sex, race/ethnicity, wealth, income, and education, the following measures were significantly associated with 1-year mortality: more than 1 ADL dependence (29% vs 13%; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 2.76; P = .001), more than 1 instrumental ADL dependence (21% vs 14%; aHR, 1.32; P = .05), the inability to walk several blocks (17% vs 11%; aHR, 1.64; P = .01), dementia (21% vs 12%; aHR, 1.91; P = .03), and depression (19% vs 12%; aHR, 1.72; P = .01). The risk of 1-year mortality increased within the increasing risk factors present (0 factors: 10.0%; 1 factor: 16.2%; 2 factors: 27.8%).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this older adult cohort, 223 participants (17%) who underwent major surgery died within 1 year and poor function, cognition, and psychological well-being were significantly associated with mortality. Measures in function, cognition, and psychological well-being need to be incorporated into the preoperative assessment to enhance surgical decision-making and patient counseling.

This cohort study examines the association of functional, cognitive, and pyschological measure with 1-year mortality for patients enrolled in the Health and Retirement Study who underwent major surgery.

Introduction

In the United States, more than 4 million operations are performed annually for patients 65 years and older.1 Older adults are more medically complex and are at higher risk of morbidity and mortality than younger adults.2 Currently, routine risk assessments emphasize medical conditions. However, health and well-being in older persons may be as much dictated by physical, cognitive, and psychological function as by medical conditions. These domains of function are not often part of routine risk assessment in surgical patients. Yet, a focus on medical conditions may not be adequate for the more medically complex and frail population. Conceptual models specific to geriatric care suggest that it is a combination of multiple domains of risk factors, such as physical, cognitive, and psychological function, that affects outcomes.

Despite high rates of older adults undergoing surgery, to our knowledge, the risk factors that may be especially relevant to outcomes in older adults who undergo a major surgery are not well studied.3,4,5,6,7,8 Specifically, a relevant outcome of long-term mortality beyond the traditional 30-day mortality better informs the patient’s surgical decision-making. For example, an asymptomatic frail, older adult may forgo a procedure, such as an abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (AAAR), if they have a high 1-year mortality risk. Improving our understanding of functional, cognitive, and psychological risk factors in this population, particularly their ability to predict risk beyond typical medical factors, is essential to providing patient-centered care.9,10,11,12,13,14 This understanding helps inform targets for preoperative risk assessment and optimization that may lead to improved patient outcomes. Additionally, incorporating these factors in risk adjustment will aid in appropriately comparing outcomes across clinicians who care for medically complex and frail patients.

The objective of this study was to understand functional, cognitive, and psychological risk factors that are associated with long-term mortality outcomes in older adults after major surgery. The goal is to inform the preoperative evaluation of the medically complex and frail population. This hypothesis was tested by using the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative cohort of older community-dwelling adults.

Methods

Data Sources and Patients

The HRS is a longitudinal study supported by the National Institute on Aging that measures changes in the health and economic circumstances of Americans as they age and is nationally representative of persons older than 50 years. Initiated in 1992, new participants have periodically been recruited to remain representative of the US population. From 1992 to 2014, HRS has recruited 12 waves of 18 000 to 23 000 participants each and continues to recruit. The HRS sample is based on a multistage area probability design involving geographical stratification and the clustering and oversampling of certain demographic groups.15 HRS interviews are conducted by phone or face to face (overall response rate, >80%) every 2 years. If an individual is unable to complete an interview because of physical or cognitive impairment, the interview is conducted with a proxy respondent, generally a family member.

We identified HRS participants 66 years and older who underwent a major surgery case by linking the HRS survey to Medicare claims. We used a prior classification that defined major surgery as either an AAAR, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), or colectomy. This combination of operations has been used in prior studies of high-risk surgery because they are common, high risk and reliably coded in claims data and together represent a diverse range of operations.16,17 High risk was defined as having a 30-day mortality rate of at least 1%.1 These procedures were identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes (AAAR: 3834, 3844, 3925, and 3864; CABG: 3610, 3611, 3612, 3613, 3614, 3615, 3616, 3617, 3619, 362, 363, 3631, 3632, 3633, 3634, and 3639; colectomy: 4571, 4572, 4573, 4574, 4575, 4576, 4579, 4581, 4582, 4583, 1731, 1732, 1733, 1734, 1735, 1736, 1739, 4503, 4526, 4541, and 4549). Of 28 013 HRS participants 66 years or older between 1992 and 2014, 24 647 (88%) agreed to have their HRS surveys linked to the Medicare claims. We identified 2291 participants who underwent a major surgery. Because we used Medicare claims to identify comorbidities before the major surgical event, we excluded participants who were not enrolled in Medicare fee for service 1 year before the surgery. Of the remaining 1829 participants, 488 (27%) who had no HRS interview within 2.5 years before the major surgery were excluded. The resulting cohort included 1341 HRS participants who underwent a major surgery. The institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco, reviewed and approved this study. Participants or a proxy provided written informed consent for the HRS.

Data Collection and Measurement

The HRS interview data were used to characterize the sample in terms of self-reported age, sex, race or ethnicity (eg, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other), education, wealth, net worth, income, marital status, nursing home residence, and presence of a geriatric syndrome (eg, hearing or vision difficulty, incontinence). We determined a history of dementia and a Charlson comorbidity score for each participant using Medicare claims.

Outcome Variable

The primary outcome was postoperative mortality at 1 year following surgery. We did additional analyses that examined 6-month and 2-year mortality. Mortality was determined using National Death Index–linked data.

Variables

Variables were chosen with the recognition that geriatric surgical outcomes may be because of the complex interplay of patients’ medical, functional, and psychological risk. Variables were derived from the HRS participant interview preceding the surgery. Three functional measures were included. Activities of daily living (ADL) included difficulty and a need for help with bathing, dressing, eating, using the toilet, getting in and out of bed, and walking across the room. Instrumental ADL (IADL) included difficulty and a need for help with preparing meals, financing, using a phone, shopping, and taking medication. For ADL and IADL, participants were first asked if they had difficulty doing the activity. If they had difficulty, they were then asked if they were able to complete the activity without help. For ADL and IADL function, participants were classified into 1 of the following hierarchal categories: able to complete all the activities with or without difficulty in 1 or more activities (independent); a need for help in 1 activity (dependent in 1 ADL); or a need for help in more than 1 activity (dependent in 2 or more ADLs). Finally, we considered whether participants reported having difficulty walking several blocks. We included a psychological measure to assess the presence of depression. Depression was measured based on the 8-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression (CES-D) interview. Depression was defined by a CES-D score of 3 or more.18 This (CES-D) interview was not incorporated into the HRS questionnaire until 1993; therefore, participants who underwent surgery before this time were not included in the depression analysis.

Cognitive function was measured using the validated HRS cognitive scale, which was derived from Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and telephone interview of cognitive status. When the participant was not able to be interviewed, a validated algorithm using surrogate observations of cognitive capacity was used. Based on the cognitive scale or surrogate observations, participants were classified as cognitively normal, cognitively impaired, or with dementia using the Langa-Weir Cognitive algorithm developed by Langa et al19 and validated with HRS participants.20 If the Langa-Weir cognitive score was missing, the Medicare ICD-9 code for dementia (290.XX) was used.

Statistical Analysis

Our analytic approach sought to determine whether measures of physical, cognitive, and psychological function are associated with mortality after accounting for comorbidity burden, demographic characteristic (age, race/ethnicity, sex, net worth, and years of education), and surgery type. We used Cox regression models to determine associations between geriatric factors and mortality through 2 years of follow-up and to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

We adjusted for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, wealth, Charlson comorbidity score, and surgery type. Because surgical techniques may have changed over the years, we performed a sensitivity analysis adjusting for the year the surgery was performed. The findings were not significant and are therefore not presented in this article. To illustrate the clinical effect of each of these risk factors, we used these models to find the association between 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year mortality for patients with and without each risk factor after adjustment for the other variables in the model. To estimate the association of accumulating geriatric risk factors, we then categorized the patients by the number of geriatric risk factors they had and determined the percentage who died at 1 year as a function of the number of risk factors.

All analyses were weighted to account for the differential probability of participant selection and the complex survey design of the HRS. Statistical analyses were performed SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute) and statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The characteristics of the 1341 older adults in the HRS who underwent major surgery are presented in Table 11,19 (mean [SD] age, 76 [6] years; 737 female [55%]; 1134 white [85%]). Most were community-dwelling older adults (1316 [98%]), with 847 (63%) married or partnered and 805 (60%) who had social support other than their spouse. Eight hundred eighty-four (66%) had more than 2 comorbidities. Most were independent or had difficulty but did not need help in ADLs and IADLs (1238 [92%] and 1170 [90%], respectively). Seventy-five (6%) had dementia and 271 (23%) had cognitive impairment without dementia. Three hundred six (25%) had depression prior to surgery.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants.

| Characteristics | Cohort, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| No. | 1341 |

| Age, median (SD), y | 76.4 (6.3) |

| 65-74 | 541 (40.3) |

| 75-84 | 557 (41.5) |

| ≥85 | 243 (18.1) |

| Female | 737 (55.0) |

| Race | |

| White | 1134 (84.6) |

| Black | 114 (8.5) |

| Hispanic | 77 (5.7) |

| Other | 16 (1.2) |

| Education less than high school | 411 (30.7) |

| Income, median (IQR), US $ | 27 600 (15 372-46 800) |

| Net worth, median (IQR), US $ | 158 000 (50 500-400 000) |

| Social demographics | |

| Married or partnered | 847 (63.2) |

| Proxy interview | 89 (6.6) |

| Lives in community | 1316 (98.1) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |

| ≤2 | 457 (34.1) |

| >2 | 884 (65.9) |

| Depressiona | 306 (24.5) |

| Cognitionb | |

| Cognitively normal | 843 (70.9) |

| Cognitive impairment | 271 (22.8) |

| Dementia | 75 (6.3) |

| ADL Function | |

| Independent | 1238 (92.4) |

| Dependent in 1 ADL | 56 (4.2) |

| Dependent in ≥2 ADL | 46 (3.4) |

| IADL Function | |

| Independent | 1170 (90.5) |

| Dependent in 1 IADL | 79 (6.1) |

| Dependent in ≥2 IADL | 44 (3.4) |

| Specific physical functions | |

| Difficulty walking several blocks | 561 (43.3) |

| Difficulty climbing 1 flight of stairs | 259 (20.3) |

| Difficulty lifting or carrying 10 lb | 331 (25.8) |

| Difficulty pushing or pulling large objects | 365 (29.9) |

| Geriatric syndromes | |

| Incontinence | 266 (20.4) |

| Vision impairment | 339 (26.0) |

| Hearing impairment | 389 (29.8) |

| Surgery type | |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | 99 (7.4) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 686 (51.2) |

| Colectomy | 556 (41.5) |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; IQR, interquartile range.

Depression was defined by a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score of 3 or more.1

Cognition was measured by Langa-Weir score19 and using Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data to identify dementia diagnosis.

Mortality After Major Surgery

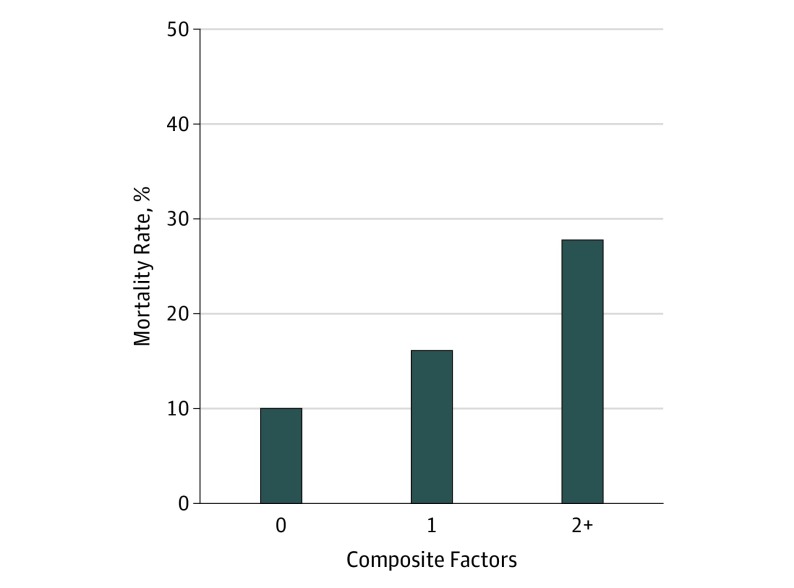

Of the 1341 participants who underwent high-risk surgery, 225 (17%) died within a year of surgery. The hazard ratios of the probability of death and the calculated 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year rates of death are presented in Table 2.1,19 A graph of the mortality rates in each group can be found in the eFigure in the Supplement. After adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, wealth, and surgery type, the following factors were associated with 1-year mortality: multimorbidity, dependence in 2 or more ADL or IADLs, not being able to walk several blocks, cognitive function, and depression. The Figure shows the 1-year mortality rate increases markedly as the number of geriatric risk factors increase, increasing from 10% in those with no risk factors to 28% in those with 2 or more risk factors.

Table 2. Multivariate Analysis of Mortality After Major Surgerya in 1341 Participants.

| Characteristic | (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | Mortality, % | |||

| 6-mo (n = 170) | 1-y (n = 225) | 2-y (n = 303) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||||

| 0-1 | 1 [Reference] | 8 (6-10) | 10 (7-13) | 15 (11-18) |

| ≥2 | 1.16 (0.81-1.66) | 12 (10-14) | 16 (13-18) | 22 (19-25) |

| Depressionb | ||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 9 (7-11) | 12 (10-15) | 17 (14-20) |

| Yes | 1.72 (1.16-2.54) | 14 (10-18) | 19 (14-23) | 26 (20-32) |

| Baseline cognitionc | ||||

| Cognitively normal | 1 [Reference] | 10 (7-12) | 12 (10-15) | 18 (15-21) |

| Cognitive impairment | 1.10 (0.73-1.66) | 13 (10-15) | 16 (13-19) | 23 (19-27) |

| Dementia | 1.91 (1.08-3.39) | 16 (10-22) | 21 (14-28) | 30 (19-39) |

| Baseline ADL functiond | ||||

| Independent | 1 [Reference] | 10 (8-12) | 13 (11-15) | 19 (16-21) |

| Dependent in 1 ADL | 0.97 (0.42-2.24) | 15 (11-19) | 20 (15-24) | 28 (21-33) |

| Dependent in ≥2 ADLs | 2.76 (1.53-4.98) | 23 (12-33) | 29 (16-40) | 40 (23-53) |

| Baseline IADL functione | ||||

| Independent | 1 [Reference] | 10 (8-12) | 14 (11-16) | 19 (17-22) |

| Dependent in 1 IADL | 2.23 (1.29-3.86) | 13 (9-16) | 17 (13-21) | 24 (18-29) |

| Dependent in ≥2 IADLs | 1.32 (0.58-2.98) | 16 (8-23) | 21 (11-30) | 29 (16-41) |

| Able to walk several blocks | ||||

| Yes | 1 [Reference] | 8 (7-10) | 11 (9-13) | 16 (13-18) |

| No | 1.64 (1.13-2.38) | 13 (10-16) | 17 (13-20) | 24 (19-28) |

| Surgical type | ||||

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | 1 [Reference] | 8 (5-11) | 10 (7-14) | 15 (10-19) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 0.47 (0.27-0.82) | 10 (8-12) | 13 (11-15) | 18 (16-21) |

| Colectomy | 0.86 (0.52-1.42) | 13 (10-15) | 16 (13-19) | 23 (19-27) |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, income, wealth, and surgery type.

Depression was defined by a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score of 3 or more.1

Cognition is defined using Langa-Weir score19 and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data.

ADL includes bathing, dressing, eating, using the toilet, getting in and out of bed, and walking across the room.

IADL includes preparing meals, financing, using the phone, shopping, and taking medication.

Figure. One-Year Mortality Rate of Older Adults Who Underwent a Major Surgery Based on the Composite Number of Functional, Cognitive, and Psychological Risk Factors.

Composite factors included (1) dependency in 2 or more activities of daily living, (2) dependency in 1 or more instrumental activities of daily living, (3) an inability to walk several blocks, (4) the presence of dementia, and (5) the presence of depression. The mortality rate for composite factors was 10.04% for dependency in 0, 16.16% for dependency in 1, and 27.81% for dependency in 2 or more.

Discussion

In this nationally representative study of older persons who underwent 1 of 3 major surgical operations, 17% died within a year of the operation. Measures that are crucial to the well-being of older persons, including ADL impairment, IADL impairment, mobility impairment, dementia, and depression, were strongly associated with 1-year mortality even after adjusting for multimorbidity and demographic factors. The accumulation of geriatric risk factors was associated with higher mortality rates. Our findings support the notion that preoperative assessment in older persons needs to consider not just the disease burden of the patient but also these domains of physical and cognitive functioning and psychological well-being.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the association between multiple risk factors grounded in the geriatric assessment with long-term postoperative outcomes using a nationally representative longitudinal cohort of older adults who have undergone major surgery. In our previous work in the nursing home population, we showed that functional and cognitive impairment were strongly associated with 1-year mortality and functional decline in women undergoing surgery for breast cancer.21 Other studies, generally single-centered, have found that preoperative physical and cognitive function are associated with short-term mortality (ie, 30-day, 6-month).22,23,24 One national study found that preoperative cognition and function was associated with 30-day mortality in older surgical adults.25 This increasing body of literature supports the importance of functional and cognitive assessments in the preoperative setting, specifically for older adults undergoing major surgery.

While psychological risk factors are important to older adults and are their own domain in the comprehensive geriatric assessment, few have assessed the association of psychological factors with mortality in older adults undergoing major surgery. We identified that 25% had depression before their surgery and depression was significantly associated with 1-year mortality. In a study of CABG surgery, 30% to 40% of patients were affected by depression and the risk associated with mortality after CABG surgery increased independently of medical factors.26

Strengths and Limitations

The key strength of our study was our ability to examine multiple nontraditionally evaluated risk factors in a nationally representative cohort of older persons undergoing major surgery. Because of the variable timing of HRS interviews, a limitation of our study is that measures were assessed at variable points before surgery depending on the timing of the HRS interview. However, increased time between measuring the geriatric risk factors and surgery would blunt the association between these risk factors and surgical mortality, assuming that the measures are worse the more proximal to the surgery. Thus, our study likely understates the importance of these risk factors. There may be several limitations to using the HRS and the development of our cohort. While the HRS cohort is developed to be nationally representative of older adults in the United States, it may not be representative of the elderly US population undergoing surgery. Analyses using a subsample of the HRS are likely to be somewhat less representative than the overall sample. Also, as is common in analyses uses Medicare claims, HRS participants who underwent surgery while enrolled in a Medicare Advantage program were excluded. Therefore, the representativeness of our surgical sample may be less than that of the surgical population in the United States. In regard to the development of the surgical cohort, we selectively chose 3 major operations, AAAR, CABG, and colectomy, but did not include other types of operations, such as the total hip replacement, which is a very common operation yet relatively low-risk operation. Because of this, for example, the population we described may not be representative of those that undergo the total hip replacement. Lastly, because our data lacked the reason of death, we are unable to determine the main cause of the mortality and are therefore unable to discuss the potential association of the main cause of death with the measures of interest. However, 242 of the HRS participants who underwent a colectomy had colorectal cancer (43.5%) and this may help explain the higher mortality in this cohort.

Increasingly, the literature supports that factors, such as cognition and function, are associated with surgical outcomes. Our research findings highlight the need to include the assessment of cognition, function, and psychological factors in the preoperative setting for older adults undergoing major surgery. These findings matter for several reasons: they highlight the importance of evaluating nonmedical factors in conjunction with the traditional factors and support the need for a paradigm shift in preoperative medical care to a more holistic approach in which cognition, function, and psychological factors are considered. Risk factors found to be significant likely increase the baseline risk of mortality in those with and without surgery; however, identifying these risk factors in the preoperative setting will likely help identify those who have less ability to withstand the stress of surgery. This information will help inform those who may have a limited life expectancy following surgery to consider whether the stress and potentially lengthy recovery period may outweigh any benefits when surgery may be elective. These findings justify including nontraditional risk factors in risk models and risk assessments and may be used to identify potential modifiable risk factors with the goal of improving postoperative outcomes.

Caring for the medically complex and frail older patients needs to incorporate the evaluation of functional, cognitive, and psychological factors in the evaluation of outcomes and risk assessments. A study of patients in an orthopedic spine clinic revealed that 70% of their cohort had preoperative cognitive impairment and those with cognitive impairment had worse postoperative delirium and postoperative complications and discharge institutionalization.27 This highlights that cognitive impairment is prevalent and associated with poor outcomes, yet it is not usually assessed in the preoperative setting in surgery clinics. Future research should examine how to incorporate geriatric factors in the preoperative setting using the increasing literature we have to frame decision-making within the surgical setting and how to use this information of poor postoperative outcomes in older adults with geriatric risk factors in anticipatory guidance. Additionally, studying whether these geriatric factors are modifiable and potential targets for intervention in the preoperative setting will be essential to changing care and improving outcomes.

Conclusions

Functional, cognitive, and psychological risk factors are associated with postoperative mortality. These risk factors, grounded in the geriatric assessment, add to surgical decision-making and anticipatory guidance and may inform future potential interventions. Incorporating these factors into the preoperative assessment is the first next step to improving care for older adults undergoing major surgery.

eFigure. Survival curves for each procedure type up to 2 years after surgery

References

- 1.Schwarze ML, Barnato AE, Rathouz PJ, et al. Development of a list of high-risk operations for patients 65 years and older. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(4):325-331. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamel MB, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Daley J. Surgical outcomes for patients aged 80 and older: morbidity and mortality from major noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):424-429. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pecoraro F, Gloekler S, Mader CE, et al. Mortality rates and risk factors for emergent open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the endovascular era. Updates Surg. 2018;70(1):129-136. doi: 10.1007/s13304-017-0488-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu C, Camacho FT, Wechsler AS, et al. Risk score for predicting long-term mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. 2012;125(20):2423-2430. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahian DM, O’Brien SM, Sheng S, et al. Predictors of long-term survival after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: results from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database (the ASCERT study). Circulation. 2012;125(12):1491-1500. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.066902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becquemin J-P, Pillet J-C, Lescalie F, et al. ; ACE trialists . A randomized controlled trial of endovascular aneurysm repair versus open surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysms in low- to moderate-risk patients. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(5):1167-1173.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.10.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McIsaac DI, Bryson GL, van Walraven C. Association of frailty and 1-year postoperative mortality following major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(6):538-545. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mullen MG, Michaels AD, Mehaffey JH, et al. Risk associated with complications and mortality after urgent surgery vs elective and emergency surgery: implications for defining “quality” and reporting outcomes for urgent surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):768-774. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endicott KM, Emerson D, Amdur R, Macsata R. Functional status as a predictor of outcomes in open and endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65(1):40-45. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.05.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hshieh TT, Saczynski J, Gou RY, et al. ; SAGES Study Group . Trajectory of functional recovery after postoperative delirium in elective surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):647-653. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mejía-Lancheros C, Estruch R, Martínez-González M-A, et al. ; PREDIMED Study Investigators . Impact of psychosocial factors on cardiovascular morbimortality: a prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rawtaer I, Gao Q, Nyunt MSZ, et al. Psychosocial risk and protective factors and incident mild cognitive impairment and dementia in community dwelling elderly: findings from the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(2):603-611. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberger PH, Jokl P, Ickovics J. Psychosocial factors and surgical outcomes: an evidence-based literature review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(7):397-405. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200607000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McIsaac DI, Jen T, Mookerji N, Patel A, Lalu MM. Interventions to improve the outcomes of frail people having surgery: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0190071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weir DR. Cohort profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):576-585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Gawande AA, Jha AK. Variation in surgical-readmission rates and quality of hospital care. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1134-1142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1303118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regenbogen SE, Cain-Nielsen AH, Norton EC, Chen LM, Birkmeyer JD, Skinner JS. Costs and consequences of early hospital discharge after major inpatient surgery in older adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(5):e170123. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(15):1701-1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langa KM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, et al. National estimates of the quantity and cost of informal caregiving for the elderly with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):770-778. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10123.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langa KM, Weir DR, Kabeto M, Sonnega A Langa-Weir classification of cognitive function. https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/news/langa-weir-classification-cognitive-function. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 21.Tang V, Zhao S, Boscardin J, et al. Functional status and survival after breast cancer surgery in nursing home residents. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(12):1090-1096. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gajdos C, Kile D, Hawn MT, Finlayson E, Henderson WG, Robinson TN. The significance of preoperative impaired sensorium on surgical outcomes in nonemergent general surgical operations. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):30-36. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerude MF, Dias FL, de Farias TP, Albuquerque Sousa B, Thuler LCS. Predictors of postoperative complications, prolonged length of hospital stay, and short-term mortality in elderly patients with malignant head and neck neoplasm. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2014;76(3):153-164. doi: 10.1159/000363189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Betomvuko P, Michaux I, Gabriel L, Bihin B, Gourdin M, De Saint Hubert M. P-429: gait speed as predictor of outcomes of elective cardiac surgery in older patients. Eur Geriatr Med. 2015;6:S147. doi: 10.1016/S1878-7649(15)30526-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berian JR, Zhou L, Hornor MA, et al. Optimizing surgical quality datasets to care for older adults: lessons from the American College of Surgeons NSQIP geriatric surgery pilot. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225(6):702-712.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumenthal JA, Lett HS, Babyak MA, et al. ; NORG Investigators . Depression as a risk factor for mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. Lancet. 2003;362(9384):604-609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14190-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adogwa O, Elsamadicy AA, Lydon E, et al. The prevalence of undiagnosed pre-surgical cognitive impairment and its post-surgical clinical impact in elderly patients undergoing surgery for adult spinal deformity. J Spine Surg. 2017;3(3):358-363. doi: 10.21037/jss.2017.07.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Survival curves for each procedure type up to 2 years after surgery