Abstract

Background

Approximately 25% of adults regularly experience heartburn, a symptom of gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). Most patients are treated empirically (without specific diagnostic evaluation e.g. endoscopy. Among patients who have an upper endoscopy, findings range from a normal appearance, mild erythema to severe oesophagitis with stricture formation. Patients without visible damage to the oesophagus have endoscopy negative reflux disease (ENRD). The pathogenesis of ENRD, and its response to treatment may differ from GORD with oesophagitis.

Objectives

Summarise, quantify and compare the efficacy of short‐term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI), H2‐receptor antagonists (H2RA) and prokinetics in adults with GORD, treated empirically and in those with endoscopy negative reflux disease (ENRD).

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE (January 1966 to November 2011), EMBASE (January 1988 to November 2011), and EBMR in November 2011.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials reporting symptomatic outcome after short‐term treatment for GORD using proton pump inhibitors, H2‐receptor antagonists or prokinetic agents. Participants had to be either from an empirical treatment group (no endoscopy used in treatment allocation) or from an endoscopy negative reflux disease group (no signs of erosive oesophagitis).

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data.

Main results

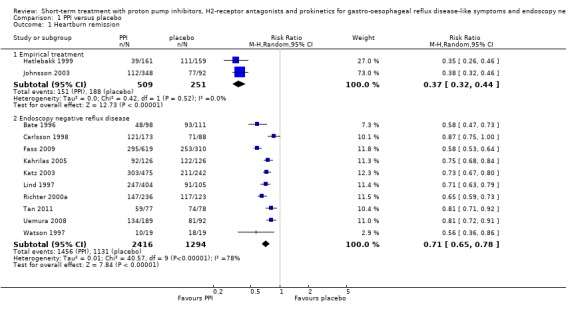

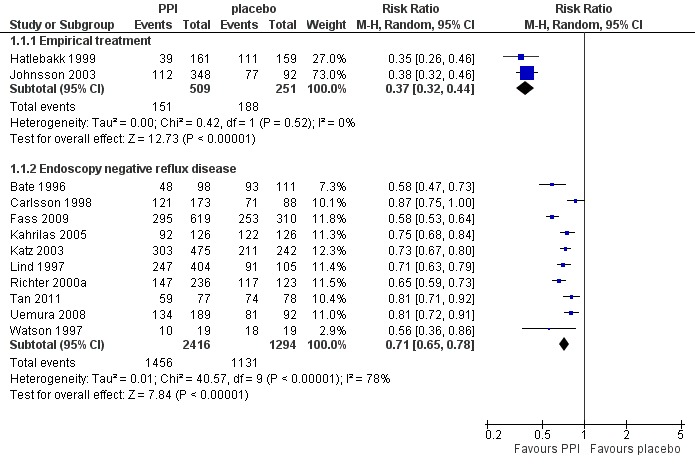

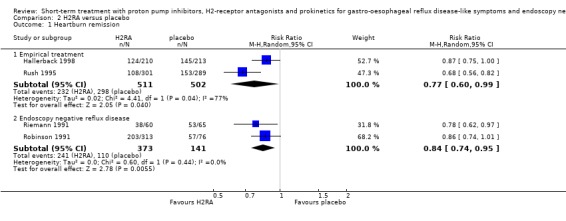

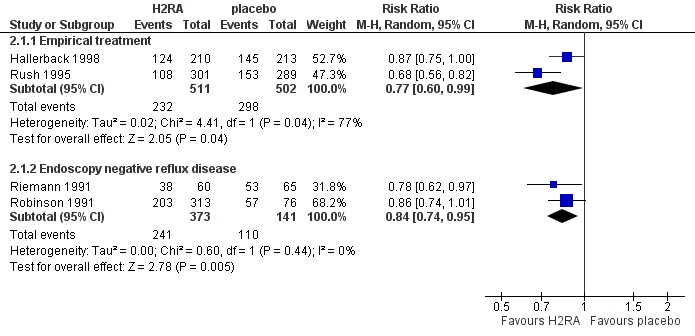

Thirty‐four trials (1314 participants) were included: fifteen in the empirical treatment group, fifteen in the ENRD group and four in both. In empirical treatment of GORD the risk ratio (RR) for heartburn remission (the primary efficacy variable) in placebo‐controlled trials for PPI was 0.37 (two trials, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.32 to 0.44), for H2RAs 0.77 (two trials, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.99) and for prokinetics 0.86 (one trial, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.01). In a direct comparison PPIs were more effective than H2RAs (seven trials, RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.73) and prokinetics (two trials, RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.87).

In treatment of ENRD, the RR for heartburn remission for PPI versus placebo was 0.71 (ten trials, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.78) and for H2RA versus placebo was 0.84 (two trials, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.95). The RR for PPI versus H2RA was 0.78 (three trials, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.97) and for PPI versus prokinetic 0.72 (one trial, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.92).

Authors' conclusions

PPIs are more effective than H2RAs in relieving heartburn in patients with GORD who are treated empirically and in those with ENRD, although the magnitude of benefit is greater for those treated empirically.

Plain language summary

Short‐term treatment with medications for heartburn symptoms

Patients with only mild or intermittent heartburn may have adequate relief with lifestyle modifications and with antacids, although other options are available. The two most commonly used drugs for treatment of heartburn are H2‐receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). These drugs act by suppressing the release of acid from the stomach. This review found that in the short term PPIs relieve heartburn better than H2RAs in patients who are treated without specific diagnostic testing. Although the difference is smaller, this is also true for patients with gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), who have a normal upper endoscopy . In summary, proton pump inhibitor drugs appear to be more effective than H2‐receptor antagonists for relieving heartburn.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Approximately one in four adults in Western society experience heartburn at least monthly, while 5% suffer from it daily (Corder 1996; Isolauri 1995; Locke 1997; Nebel 1976; Thompson 1982). Heartburn is associated with reduced quality of life (Dimenas 1996), with billions of dollars spent annually on healthcare costs associated with its evaluation and treatment. Heartburn, especially if accompanied by acid regurgitation, is the typical clinical manifestation of gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), a term referring to both symptoms and oesophageal mucosal damage resulting from reflux of gastric acid into the oesophagus. A consensus of experts defined GORD as a condition that develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications. Novel aspects of the new definition include a patient‐centred approach that is independent of endoscopic findings (Vakil 2006). The disease was sub‐classified into oesophageal and extra‐oesophageal syndromes. The accuracy of symptoms in diagnosis of GORD depends on the nature and severity of symptoms and the reference standard used. One study (Klauser 1990) found that clearly dominant heartburn had a positive predictive value of 81% in diagnosing GORD (when defined by oesophageal pH (acidity) monitoring). Accuracy was reduced when the presence of heartburn alone was considered. Monitoring of oesophageal pH has been proposed as a reference standard for GORD, but is inconvenient and the result is negative in more than one third of patients with chronic heartburn. Furthermore, many patients with a normal pH do respond to antacids and have symptoms reproducible by acid infusion, while some even have oesophageal mucosa damage (Rodriguez 1999; Shi 1995). The main importance of the use of endoscopy lies in diagnosing oesophagitis with possible complications such as bleeding, stricture formation, Barrett's metaplasia and adeno‐carcinoma. However, between half and two‐thirds of patients presenting with typical GORD symptoms have no endoscopic abnormalities (Joelsson 1989; Johansson 1986b; Johnsson 1987; Robinson 1998; Tefera 1997). Their condition is referred to as endoscopy negative reflux disease (ENRD). The severity and chronicity of symptoms in patients with ENRD is similar to that of patients with oesophagitis (Dent 1998; Johansson 1986b).

Description of the intervention

Several drugs are available for treatment of GORD. The most commonly used are H2‐receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Prokinetic agents are used much less commonly.

How the intervention might work

H2‐receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors improve symptoms by reducing gastric acid secretion and hence oesophageal acid exposure. By contrast, prokinetic agents work principally by increasing lower oesophageal sphincter tone, thereby reducing reflux.

Why it is important to do this review

There is considerable variability in the choice of initial therapy and the use of endoscopy across healthcare settings. The variability is in part related to an incomplete understanding of response to treatment in clinically relevant subgroups of patients. This concern is particularly relevant for patients with ENRD, since most studies of GORD therapy have focused on patients with oesophagitis (Chiba 1997). Similarly, the degree to which one option or another is better in patients who do not undergo investigation (i.e. are treated empirically) is incompletely understood.

Objectives

Summarise, quantify and compare the efficacy of the short‐term use of proton pump inhibitors, H2‐receptor antagonists and prokinetics in adults with suspected gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease who are treated empirically and in those with endoscopy negative reflux disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials with a single‐ or double‐blinded design, in which one of the intervention types was contrasted with placebo or another intervention type.

Types of participants

Adults

Either gender

Predominant heartburn (a retrosternal burning sensation), diagnosed as GORD or reflux‐like dyspepsia

-

Classifiable in one of the following two groups:

empirical treatment group: no endoscopy performed or endoscopy results not used in allocating treatment;

endoscopy negative reflux disease group: on endoscopy either a normal oesophageal mucosa or diffuse erythema (i.e. no erosive oesophagitis).

Types of interventions

Short‐term treatment (one to twelve weeks) with proton pump inhibitors (esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole and dexlansoprazole), H2‐receptor antagonists (cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine and ranitidine) or prokinetics (cisapride, domperidone and metoclopramide).

Types of outcome measures

We studied the following comparisons for both the empirical treatment group and the ENRD group:

PPI versus placebo;

H2RA versus placebo;

prokinetic versus placebo;

PPI versus H2RA;

PPI versus prokinetic;

H2RA versus prokinetic.

Primary outcomes

Heartburn remission (defined as no more than one day per week with mild heartburn).

Secondary outcomes

(Partial) symptom relief; quality of life.

Studies using other types of symptomatic outcome measures were not included in our formal analysis.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We constructed the original search strategy in Appendix 1 by using a combination of MeSH subject headings and text words relating to the symptoms of gastro oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and the associated pharmacological interventions. We applied the standard Cochrane search strategy filter for identifying randomised controlled trials to this search strategy.

For the updated review, the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE, sensitivity maximising version; Ovid format (Cochrane Handbook), was combined with the search terms in the Appendices to identify randomised controlled trials in MEDLINE. The MEDLINE search strategy was adapted for use in the other databases searched.

We identified new reports of trials for the updated review by searching MEDLINE January 1966 to November 2011 (Appendix 2), EMBASE January 1988 to November 2011 (Appendix 3), and evidence‐based medicine reviews (including Cochrane DSR, ACP Journal Club, DARE, CCTR, CMR, HTA, and NHSEED to November 2011; Appendix 4). We did not confine our search to English language publications. Searches in all databases were first conducted in December 2005, updated in November 2008 and in November 2011.

Searching other resources

We handsearched reference lists from trials selected by electronic searching to identify further relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We screened the titles and abstracts of trials identified using the search strategy first. Two review authors independently assessed the full articles of selected trials to confirm eligibility, assess quality and extract data using a data extraction form.

Data extraction and management

We recorded the following features:

Setting;

Country of origin;

Method of randomisation;

Adequacy of allocation concealment;

Details of blinding of participants and outcome assessors;

Inclusion and exclusion criteria used;

Baseline comparability between treatment groups;

Treatments compared and number of participants in each arm;

Outcome data in two‐by‐two tables or change in group means and standard deviations, when appropriate;

Drop‐outs reported and their reasons.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the full articles of selected trials to assess the risk of bias using the method described in the Cochrane Handbook.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed the impact of interventions as risk ratios together with 95% confidence intervals. We attempted meta‐analysis only if there were sufficient trials of similar comparisons reporting the same outcomes. risk ratio were combined for binary outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not encounter any unit of analysis issues.

Dealing with missing data

So far we made no attempt to retrieve missing data; where applicable it is mentioned in the relevant sections.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We originally evaluated statistical heterogeneity between studies by using the Chi² test comparing numbers of participants symptom‐free and considering significant for P values less than 0.10. For this update, we have classified studies secondarily with the I² statistic. The I² statistic describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2003). This method does not inherently depend on the number of studies in the meta‐analysis. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values show increasing heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If a study protocol described an unpublished or unavailable trial, we assessed whether the prespecified primary and secondary outcomes of interest to this review were predicted in the results in the outcomes section. We did not search for unpublished studies. In one of our comparisons (PPI versus placebo in ENRD) this 2013 update counted 10 studies for the first time. Following Cochrane guidelines this would implicate testing for “small study effects” However, this is a comparison tested to potentially host only substantial heterogeneity until now. All studies are still comparable in size. We considered testing on "small study effects" not adding substantial information.

Data synthesis

We compared the efficacy of PPI, H2RA and prokinetics with placebo and with each other. For each study, we calculated risk ratios and their 95% confidence intervals from the extracted data, and considered the finding statistically significant when the confidence interval did not include one. We calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome by taking the inverse of the absolute risk difference. We conducted all analyses on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis, i.e. including all participants randomised. For the purposes of our formal meta‐analysis, we calculated a pooled estimate of the risk ratios for heartburn relief if appropriate, using a random‐effects model, which provides a more conservative estimate of the overall treatment response by incorporating between‐study heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where we detected significant heterogeneity, we investigated possible explanations and summarised the data using a random‐effects model. We stratified data on an ITT basis, and where possible we performed subgroup analysis of double‐ versus single‐blind conditions, dose, drug class and duration of therapy. We compared change in quality of life in individual studies using group means.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed additional pooling using a fixed‐effect model to test whether point estimates were similar. If we found no difference, we have reported only the random‐effects values, as these are more conservative.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search strategy defined above generated over 3000 references (Figure 1). After screening titles, abstracts and, if necessary, the full paper, we included 34 trials in our analysis. From 19 trials we extracted data on outcome of empirical treatment for gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), and from 19 trials data on outcome of treatment for endoscopy negative reflux disease (ENRD); four trials presented data on both groups (Armstrong 2001; Bate 1997; Galmiche 1997; Venables 1997). Thirty‐one other studies did not present dichotomous outcome measures, or did not match our inclusion criteria, and were subsequently excluded. They are listed in the table Characteristics of excluded studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Design

All included studies used a double‐blinded and parallel group design. In three of them (Behar 1978; Bright‐Asare 1980; McCallum 1977) the term 'randomisation' was not stated explicitly, although some form of allocation concealment was suggested. The other studies were all described as randomised. In three studies a cross‐over design was used. From two of them (Johansson 1986b; McCallum 1977) we extracted only data from the first treatment period, while the third study (Watson 1997) did not provide these data, so we used data from the full cross‐over study (a carry‐over effect was not anticipated).

Setting

The 34 trials were conducted in North America, Europe, Australia, South Africa, China and Japan. All but five (Bright‐Asare 1980; Johansson 1986b; McCallum 1977; Tan 2011; Watson 1997) were multicentre trials. In six (Armstrong 2005; Carlsson 1998; Hatlebakk 1999; Rush 1995; Talley 2002; Venables 1997), participants were exclusively recruited by primary care physicians. Recruitment in another (Bardhan 1999) was from both primary and secondary care centres. One trial studied patients referred to a regional ambulatory pH monitoring service (Watson 1997), and one included only patients referred for possible anti‐reflux surgery (Johansson 1986b). The other studies provided no details on participant recruitment.

Participants

Empirical Treatment Group

We extracted data from a total of 6734 participants in nineteen trials. The mean number randomised per trial in this group was 354 (range 34 to 994). The mean age of all participants was 51 years (range 18 to 87), with 54% male. One trial included participants with symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation (McCallum 1977), one with two of the following: heartburn, epigastric pain and regurgitation (Hallerback 1998), one with long‐standing symptoms of GORD (Johansson 1986b) and another with symptoms of heartburn, acid eructation or pain on swallowing/dysphagia (Van Zyl 2004).

In all other trials, the primary inclusion criterion was heartburn meeting various criteria concerning severity, frequency and duration. Positive Bernstein testing was additionally required for all participants in two studies (Behar 1978; Bright‐Asare 1980), and only for participants with no signs of oesophagitis in two other studies (Sabesin 1991; Sontag 1987). In one trial reflux had to be demonstrable on x‐ray or oesophagoscopy (McCallum 1977). In seven trials endoscopy was either not performed (Armstrong 2005; Castell 1998; Rush 1995; Talley 2002; Van Zyl 2004) or its findings were not described (Bright‐Asare 1980; McCallum 1977). Participants with circumferential oesophagitis or oesophageal ulcer were excluded from seven trials (Armstrong 2001; Bardhan 1999; Bate 1997; Galmiche 1997; Hallerback 1998; Johnsson 2003; Venables 1997). One trial excluded participants with continuous (but non‐circumferential) mucosal breaks (Hatlebakk 1999). Other common reasons for exclusion were: Barrett's oesophagus, oesophageal stricture, peptic ulcer disease and the recent use of antisecretory drugs.

Endoscopy Negative Group

We extracted data from 6406 participants in nineteen trials. The mean number of participants randomised per trial was 337 (range 19 to 947). The mean age of the participants was 48 years (range 18 to 80), with 41% male. One trial included participants with both heartburn and regurgitation (Riemann 1991), three with either heartburn or regurgitation (Fujiwara 2005; Tan 2011; Watson 1997) and one with heartburn, regurgitation or dysphagia (Schenk 1997). In all other trials, heartburn was the primary inclusion criterion. Additional positive Bernstein testing was required in one study (Robinson 1991), a normal 24‐hour pH study in another (Watson 1997). Participants with any degree of erosive oesophagitis were excluded from all studies in this group. Other common exclusion criteria were: Barrett's oesophagus, oesophageal stricture, peptic ulcer disease and the recent use of antisecretory drugs.

Intervention

Empirical Treatment Group

Ten trials studied a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). This included fourteen treatment arms studying esomeprazole (20 mg twice and 40 mg once daily), omeprazole (10, 20 and 40 mg once daily) and pantoprazole (20 and 40 mg once daily) versus placebo (two studies; two and eight weeks), versus H2‐receptor antagonists (H2RAs) (seven studies; two and four weeks), or versus prokinetics (one study; four weeks).

Fourteen trials studied an H2RA, including fifteen treatment arms: cimetidine (300 and 400 mg four times daily), famotidine (20 mg twice and 40 mg once daily), nizatidine (150 mg twice daily) and ranitidine (150 mg twice and 300 mg once daily) versus placebo (six studies; two, six, eight and twelve weeks), versus PPIs (seven studies; two and four weeks), or versus prokinetics (one study; eight weeks). Five trials studied a prokinetic agent (five treatment arms): metoclopramide (10 mg four times daily) and cisapride (10 mg four times and 20 mg twice daily) versus placebo (four studies; four and eight weeks), versus PPI (two studies; four and eight weeks), or versus H2RA (one study; eight weeks).

Endoscopy Negative Group

Seventeen trials studied PPIs (28 treatment arms): esomeprazole (20 and 40 mg once daily), omeprazole (10, 20 and 40 mg once daily), lansoprazole (15 and 30 mg once daily), pantoprazole (40 mg once daily), rabeprazole (20 mg once daily) and dexlansoprazole (30 and 60mg once daily) versus placebo (ten trials; two, four and eight weeks), versus H2RAs (five studies; four and eight weeks), or versus prokinetics (one study; four weeks).

Seven trials studied H2RAs (eight treatment arms): cimetidine (200 or 400 mg four times daily), famotidine (20 mg twice or 40 mg once daily), nizatidine (150 mg twice daily) and ranitidine (150 mg twice daily) versus placebo (two studies; two and six weeks), or versus PPIs (five studies; four and eight weeks).

Prokinetics were studied in one trial (one treatment arm), where cisapride (10 mg four times daily) was compared with a PPI (four weeks).

Outcome

Symptomatic outcome measures were used in all trials, since this was one of the inclusion criteria for this review. Data on heartburn outcome were provided in most detail, often expressed in terms of severity and frequency, using measures such as visual analogue scales (VAS), four‐grade Likert or own‐symptom scores. In some studies a distinction was made between outcome for daytime and night time heartburn. Many studies provided limited data on regurgitation, dysphagia and other symptoms. The primary efficacy variable of this review was remission of heartburn, defined as no more than one day with mild heartburn per week. Eleven trials used a quality of life instrument in assessing therapeutic response. The Gastro‐intestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) was used in seven (Armstrong 2001; Armstrong 2005; Carlsson 1998; Fujiwara 2005; Galmiche 1997; Lind 1997; Talley 2002), the Psychological General Well‐Being index (PGWB index) in two (Galmiche 1997; Lind 1997), the Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐36) in four (Armstrong 2001; Fujiwara 2005; Rush 1995; Tan 2011) and the heartburn‐specific questionnaire in one (Rush 1995).

Excluded studies

We excluded 31 potentially eligible trials. See the Characteristics of excluded studies table for details.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias assessments are shown in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Six of the more recent trials (Armstrong 2005; Fass 2009; Katz 2003; Lind 1997; Talley 2002; Tan 2011) were classified as having a low risk of selection bias, indicating adequate allocation concealment. In all the other trials, little or no information was provided on allocation concealment. In those cases we classified the risk of bias as unclear.

Blinding

Performance bias and detection bias were evaluated for the 2013 update. In 17 studies (Armstrong 2001; Armstrong 2005; Bardhan 1999; Bate 1996; Castell 1998; Fass 2009; Galmiche 1997; Hatlebakk 1999; Johnsson 2003: Kahrilas 2005; Katz 2003; Richter 2000b; Rush 1995; Talley 2002; Tan 2011; Van Zyl 2004; Venables 1997) blinding was assessed as being adequate. In one trial (Fujiwara 2005) no blinding was described, so we classified it as having a high risk of bias. None of the other trials provided enough information to classify the risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

The quality of data reporting by most trials was poor; ITT analysis was reported in only a few studies, although in most cases data could be re‐analysed on an ITT basis from the data presented. Data could be analysed only per protocol from four studies (Bardhan 1999; McCallum 1977; Riemann 1991; Schenk 1997).

Selective reporting

There was insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk of reporting bias in any trials. All are assessed as being at unclear risk. Fass 2009 measured quality of life as a secondary outcome, but did not report the results.

Other potential sources of bias

Galmiche 1997, testing PPI versus prokinetics, used an inadequate dose of omeprazole (10mg) in one treatment arm, which could have decreased the relative efficacy of the PPI. Castell 1998 selected participants by means of a placebo run‐in period, which could have increased the relative efficacy of the cisapride. Johansson 1986a used a cross‐over design.

We found no obvious potential source of bias in the remaining trials, apart from the fact that the use of antacids as rescue medication was allowed in most of the included trials. Since a higher use of rescue medication can be expected, and was observed, in the study group randomised to receive the less effective drug or placebo, the clinical outcome in this group may improve, thereby decreasing the relative efficacy of the more effective drug. This effect may also account for the high healing rate observed in placebo groups from oesophagitis trials (Chiba 1997).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. PPIs, H2RAs or prokinetics for heartburn remission in gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease‐like symptoms.

| PPIs, H2RAs or prokinetics for heartburn remission in gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease‐like symptoms | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with heartburn remission in gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease‐like symptoms Settings: Intervention: PPIs, H2RAs or prokinetics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | PPIs, H2RAs or prokinetics | |||||

| PPI versus placebo Symptomatic outcome measures | 75 per 100 | 28 per 100 (24 to 33) | RR 0.37 (0.32 to 0.44) | 760 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high1 | |

| H2RA versus placebo | 59 per 100 | 46 per 100 (36 to 59) | RR 0.77 (0.6 to 0.99) | 1013 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Prokinetic versus placebo | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 322 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

| PPI versus H2RA | 68 per 100 | 45 per 100 (41 to 49) | RR 0.66 (0.60 to 0.73) | 3147 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| PPI versus prokinetic | 59 per 100 | 32 per 100 (19 to 52) | RR 0.53 (0.32 to 0.87) | 747 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Allocation of concealment unclear in both studies. No high risk of bias in either study. 2 Allocation of concealment unclear in both studies. High risk of attrition bias in both studies. 3 Heterogenity was caused by one study which could not be explained. 4 Allocation of concealment unclear in both studies. High risk of other bias in one study. 5 Risk Ratio 0.53 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.87)

Summary of findings 2. PPIs, H2RAs or prokinetics for heartburn remission in endoscopy negative reflux disease.

| PPIs, H2RAs or prokinetics for for heartburn remission in endoscopy negative reflux disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with heartburn remission in endoscopy negative reflux disease Settings: Intervention: PPIs, H2RAs or prokinetics for | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | PPIs, H2RAs or prokinetics for | |||||

| PPI versus placebo | 87 per 100 | 62 per 100 (57 to 68) | RR 0.71 (0.65 to 0.78) | 3710 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| H2RA versus placebo | 78 per 100 | 66 per 100 (58 to 74) | RR 0.84 (0.74 to 0.95) | 514 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| PPI versus H2RA | 57 per 100 | 45 per 100 (36 to 56) | RR 0.78 (0.62 to 0.97) | 960 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | |

| PPI versus prokinetic | 54 per 100 | 39 per 100 (30 to 50) | RR 0.72 (0.56 to 0.92) | 302 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Heterogenity was caused by two trials and could not be explained. 2 Allocation concealment unclear in both studies. High risk of attrition bias in both studies. 3 Allocation concealment unclear in all four studies. 4 Heterogenity was caused by one trial and could not be explained. 5 Allocation unclear in the study.

Empirical treatment for gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)

Heartburn remission

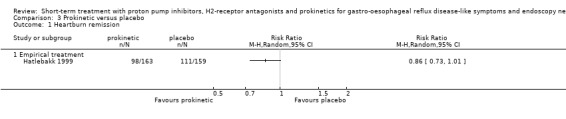

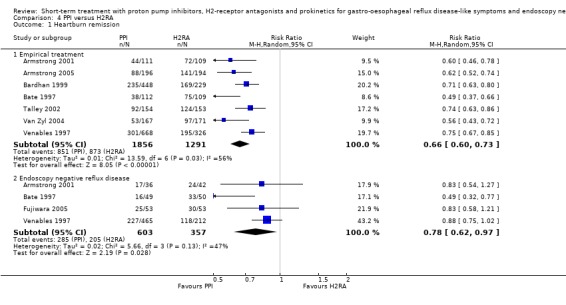

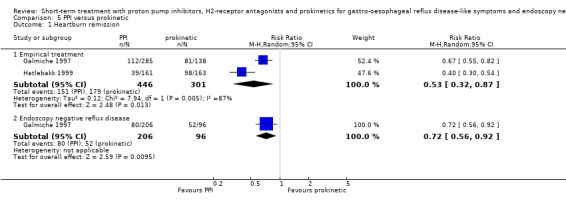

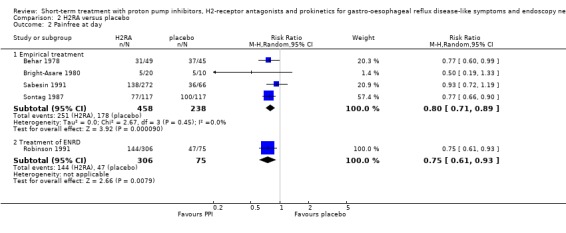

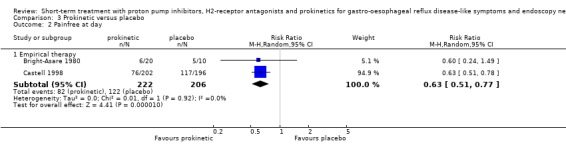

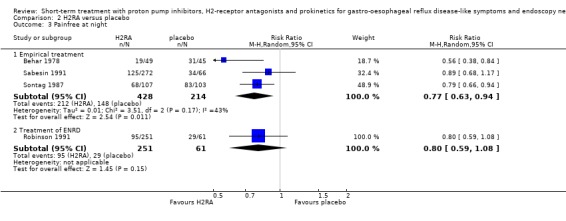

The risk ratio (RR) in the two placebo‐controlled proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trials was in favour of the PPI: 0.37 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.44; Analysis 1.1, Figure 3). For H2RA versus placebo (two trials) RR was 0.77 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.99; Analysis 2.1, Figure 4) and for prokinetic versus placebo (one trial) 0.86 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.01; Analysis 3.1). Seven trials compared a PPI with an H2RA. PPIs were significantly (P < 0.05) more effective (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.73; Analysis 4.1, Figure 5). The RR for PPI versus prokinetic (two trials) was 0.53 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.87; Analysis 5.1). None of the trials comparing H2RAs with prokinetics reported outcome in terms of complete heartburn relief.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PPI versus placebo, Outcome 1 Heartburn remission.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 PPI versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Heartburn remission.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 H2RA versus placebo, Outcome 1 Heartburn remission.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 H2RA versus placebo, outcome: 2.1 Heartburn remission.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Prokinetic versus placebo, Outcome 1 Heartburn remission.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 PPI versus H2RA, Outcome 1 Heartburn remission.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 PPI versus H2RA, outcome: 4.1 Heartburn remission.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 PPI versus prokinetic, Outcome 1 Heartburn remission.

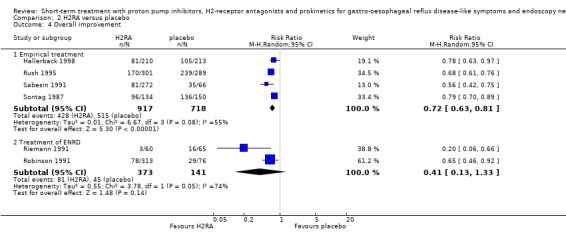

Overall symptom improvement

For H2RA (four trials) and prokinetic (two trials) the RR in placebo‐controlled trials was 0.72 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.81; Analysis 2.4) respectively 0.71 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.91; Analysis 3.4). The RR in the one trial directly comparing a PPI with an H2RA in this category was 0.29 (95% CI 0.17 to 0.51; Analysis 4.2).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 H2RA versus placebo, Outcome 4 Overall improvement.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Prokinetic versus placebo, Outcome 4 Overall improvement.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 PPI versus H2RA, Outcome 2 Overall improvement.

Daytime heartburn relief

The RR for H2RA versus placebo (four trials) was 0.80 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.89; Analysis 2.2) and for prokinetic versus placebo (two trials) 0.63 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.77; Analysis 3.2). When H2RA and prokinetic were directly compared (Bright‐Asare 1980), no significant difference in efficacy was demonstrated (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0,30 to 2,29; Analysis 6.1). No PPI trials were included.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 H2RA versus placebo, Outcome 2 Painfree at day.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Prokinetic versus placebo, Outcome 2 Painfree at day.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 H2RA versus prokinetic, Outcome 1 Painfree at day.

Night time heartburn relief

The RR for H2RA versus placebo (three trials) was 0.77 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.94; Analysis 2.3) and for prokinetic versus placebo (one trial) 0.51 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.64; Analysis 3.3). No PPI trials were included.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 H2RA versus placebo, Outcome 3 Painfree at night.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Prokinetic versus placebo, Outcome 3 Painfree at night.

Treatment for endoscopy negative reflux disease (ENRD)

Heartburn remission

Ten placebo‐controlled PPI trials in this group used this outcome measure. The RR for PPI was 0.71 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.78; Analysis 1.1, Figure 3). For H2RA versus placebo (two trials) the RR was 0.84 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.95; Analysis 2.1, Figure 4). In four trials PPIs were directly compared with H2RAs; the RR was 0.78 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.97; Analysis 4.1, Figure 5). In the only trial comparing a PPI with prokinetic treatment the outcome was in favour of the former (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.92; Analysis 5.1).

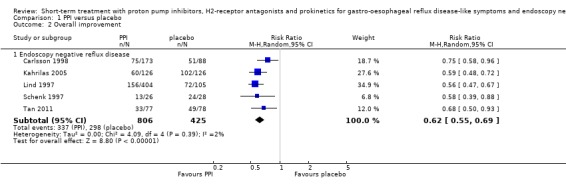

Overall symptom improvement

When PPIs were compared with placebo (six trials) the RR was 0.62 (95% CI 0.55 to 0.69; Analysis 1.2). For H2RA versus placebo (two trials) the RR was 0.41 (95% CI 0.13 to 1.33; Analysis 2.4). In the two trials directly comparing the two groups, PPIs were superior to H2RAs (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.93; Analysis 4.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PPI versus placebo, Outcome 2 Overall improvement.

Daytime heartburn relief

The only trial included here compared H2RA with placebo (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.93; Analysis 2.2).

Night time heartburn relief

The RR for H2RA versus placebo (one trial) was 0.80 (95% CI 0.59 to 1.08; Analysis 2.3).

Quality of life

For empirical treatment of GORD no significant difference between omeprazole 20 mg once, omeprazole 10 mg once and cisapride 10 mg four times daily was found with respect to the change in global psychological general well being (PGWB) and gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS). However, improvement in the reflux dimension of the GSRS was significantly greater (P < 0.05) with a PPI than with an H2RA (three trials) and greater with omeprazole 20 mg once daily than with cisapride 10 mg four times daily. In one trial (Armstrong 2005) total GSRS in four weeks improved significantly more (P < 0.001) with omeprazole 20 mg once than with ranitidine 150 mg twice daily. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were found between the effect of ranitidine 150 mg twice daily and placebo on all scales of the heartburn‐specific quality of life questionnaire, but only on three (physical functioning, bodily pain and vitality) of the acute form of the SF‐36.

In ENRD, therapy with PPIs compared with placebo significantly improved the PGWB index and the GSRS reflux dimension (P < 0.05) , but not the global GSRS score and the SF‐36. No difference in improvement in the reflux dimension of the GSRS (two trials) or in SF‐36 (one trial) could be demonstrated in this category between PPIs and H2RAs.

Other findings

Whether use of antacids as rescue medication was permitted was unclear in six trials, while it was permitted explicitly in all others. In general antacid use was significantly higher in the placebo group or in the group randomised to receive the least effective drug.

Two studies presented data on outcome in subgroups with normal pH study (Schenk 1997; Watson 1997). In both trials omeprazole (40 mg once or 20 mg twice daily) was significantly superior to placebo in providing heartburn control. Lind 1997 stratified participants according to percentage of time with pH below four. They found that sufficient heartburn control with omeprazole was achieved in all participants, with efficacy increasing with increasing baseline levels of acid reflux.

Bate 1997 stratified participants according to heartburn severity at entry. They found that the treatment effect of omeprazole was higher in participants with baseline mild heartburn compared with those with moderate or severe heartburn. In two studies (Bate 1997; Galmiche 1997) a direct comparison was made between subgroups of participants with and without oesophagitis. Omeprazole was superior to both cimetidine and cisapride regardless of the presence or absence of oesophagitis. However, the relative efficacy of omeprazole was higher in the presence of oesophagitis. Johnsson 2003 found that esomeprazole was more effective in achieving heartburn relief in participants with erosive oesophagitis than in participants without, and more effective in participants with a positive pH‐study than in participants without.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found evidence in the international literature that when patients are selected primarily based on symptoms (i.e. heartburn meeting certain criteria) and the diagnostic probability of gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is high, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are superior to both H2‐receptor antagonists (H2RAs) (seven trials) and prokinetics in achieving heartburn remission. H2RAs are also effective in promoting symptom relief, while the evidence for efficacy of prokinetics is less clear. We identified only two placebo‐controlled PPI trials on short‐term empirical treatment for GORD.

Furthermore we found evidence that in patients with endoscopy negative reflux disease (ENRD), a short course of antisecretory drugs is effective in controlling symptoms. In this group PPIs were also superior to H2RAs (four trials), although the difference was smaller compared to studies of patients treated empirically. In the only trial comparing an antisecretory (omeprazole) with a prokinetic agent (cisapride) outcome was in favour of the PPI. We did not find any placebo‐controlled trials on the efficacy of prokinetics for ENRD.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Data on the efficacy of PPIs and H2RAs in empirical treatment of GORD and in treatment of ENRD seem to be sufficient, and can be applied to daily practice. Very few data exist on the efficacy of prokinetics.

Quality of the evidence

In total, we included 34 randomised controlled trials. In general, they provided little or no information on allocation concealment. The quality of the data reporting of most trials was poor.

Potential biases in the review process

Heterogeneity was tested for the primary outcome variable only. We detected statistical heterogeneity in the PPI versus H2RA trials. Both in the empirical treatment group (I² = 56%, moderate heterogeneity) and in the ENRD group (I² = 47%, moderate heterogeneity), this was caused by the results of one trial (Bate 1997), for which we could find no clear explanation. Heterogeneity in the PPI versus prokinetic trials (empirical treatment group, I² = 87%, considerable heterogeneity) was caused by the inclusion of results from the treatment arm using a low dose omeprazole (10 mg), which decreased the relative efficacy of the PPI arm. In trials studying PPI versus placebo for ENRD (I² = 78%, substantial heterogeneity), heterogeneity was caused by two trials (Bate 1996; Carlsson 1998) and could not be explained. Finally, the placebo‐controlled H2RA trials for empirical treatment of GORD (I² = 77%, substantial heterogeneity) were heterogeneous because of differences in treatment duration. Heterogeneity overall had little impact on outcome, with sensitivity analyses revealing no large changes in pooled risk ratios. Furthermore, we detected no differences in the direction of results.

The chronic relapsing nature of GORD often requires long‐term or maintenance treatment. When GORD is treated, clinical response typically is achieved within a couple of weeks (Chiba 1997). Since our main interest was drug efficacy and not long‐term disease management, we focused on short‐term trials. Theoretically differences in treatment duration between drug groups can mask differences in efficacy. However, for the primary outcome measure we found no important differences in duration between placebo‐controlled PPI or H2RA trials.

It can be argued that our 'empirical group' is not truly empirical, since in most of the trials an endoscopy was performed and patients were excluded because of either severe or complicated oesophagitis or peptic ulcer disease (PUD). Most studies did not provide details on the number of participants excluded for this reason. We believe these numbers were not high enough to have had a significant impact on the clinical outcomes, since the incidence of PUD and severe or complicated oesophagitis amongst participants presenting with predominant heartburn is low. In one study (Hallerback 1998) only 14 participants out of 441 (3%) were excluded on the basis of these endoscopic findings. The empirical group evaluated in the review in our opinion represents a good reflection of the adult population presenting with uncomplicated GORD.

We excluded trials presenting only symptom scores as the outcome variable, because their results are difficult to pool and do not translate easily to daily practice. Symptom relief was defined in different ways in the studies we included. To present a robust conclusion, we focused attention on complete or near complete symptom relief in our formal meta‐analysis.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The efficacy of antisecretory and prokinetic agents in controlling symptoms and promoting endoscopic healing in patients with oesophagitis has previously been established (Chiba 1997; Galmiche 1990; Janisch 1988; Maleev 1990). PPIs have been proven to be superior to H2RAs, and the efficacy of prokinetics is similar to that of H2RAs. Prokinetics are no longer used widely since the availability of cisapride has been severely restricted.

Guidelines for medical treatment of GORD have been developed in different countries (Devault 2005; Kroes 1999). Most patients with suspected GORD are treated empirically. However, broad consensus has not been achieved on the optimal initial approach based upon patient characteristics. As a result there is substantial variability in the choice of initial therapy across varied healthcare settings. Much of the literature supporting the use of specific drug therapy has been based upon treatment trials that focused on patients with oesophagitis. There is far less detailed information on patients with ENRD, even though such patients represent a substantial subgroup of GORD.

GORD is a long‐term disease. Whether the short‐term results reported in this review are applicable to long‐term management strategies is unclear. In particular, the effectiveness of H2RA deteriorates with time, and thus PPIs may have a benefit in ENRD with long‐term use (Lewin 2001). On the other hand the pharmacokinetics of H2RAs are superior to PPIs for rapid relief of symptoms. Thus the smaller difference between PPIs and H2RAs in the short‐term studies in patients with ENRD is clinically relevant; such patients may achieve adequate symptom relief with long‐term use of an H2RA as needed. By contrast, patients who require regular therapy may achieve more effective long‐term symptom relief with a PPI (Ip 2005).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are more effective than H2‐receptor antagonists (H2RAs) for treatment of heartburn in patients treated empirically and in patients with endoscopy negative reflux disease (ENRD), although H2RAs are also effective. PPIs are more effective than H2RAs in studies with longer follow‐up, but which focused mainly on participants with oesophagitis (Ip 2005).

Both a PPI and an H2RA are therefore reasonable options for achieving short‐term symptom relief in patients with ENRD. However, this review did not address the relative efficacy of these drugs in the long‐term management of ENRD.

While prokinetics are considered to be as effective as H2RAs, evidence is weak for their use in empirical treatment of gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), and even weaker for ENRD. Furthermore, the availability of the only prokinetic studied in this review, cisapride, has been severely restricted since 2001 because of a risk of cardiac arrhythmias. Thus the clinical importance of our findings regarding cisapride is mainly relevant as a background for future prokinetic drugs.

Implications for research.

Further studies are needed to clarify whether subgroups of people can be identified who would benefit most from initial therapy with a PPI or in whom (in contrast) an H2RA would be sufficient, especially form a long‐term management perspective.

The efficacy of H2RAs decreases with regular dosing over time, potentially making them less effective than PPIs for long‐term use. However, the pharmacokinetics of H2RAs are superior to PPIs for achieving rapid relief of symptoms, an important objective in patients with troubling intermittent symptoms. People with ENRD who have only intermittent symptoms may therefore be better off with a strategy involving intermittent use of an H2RA as needed. Our review did not evaluate a number of alternative strategies used in clinical practice, including combination drugs (H2RA plus an antacid), lifestyle modifications combined with drugs, and short‐term (two weeks) use of a PPI as needed. Further studies are needed to evaluate these various strategies directly.

Future trials using heartburn as an end point should define treatment success as complete heartburn relief and use a validated quality of life measure, ideally with the same measure used across studies to facilitate comparisons. Such studies should also consider explicitly the use of rescue medications, such as antacids, since they may be important confounders of the main end points. Standardised criteria for defining GORD based upon symptoms alone should also be developed for use in clinical trials.

Feedback

Problem reading analyses, 5 July 2009

Summary

Dr Wen‐Yi Shau 03‐Jun‐2009 Feedback: I like to ask questions about analysis of "Short‐term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2‐receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease‐like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease." I have problem reading the number (n/N) in analysis correctly. The result in favour of PPI but all the (n/N) for PPI looks no better then comparators (including placebo). For example: analysis 1.1, the outcome 1 was heartburn remission, the first row showed study result of Hatlebakk 1999, the number for PPI (n/N) was 39/161, and placebo was 111/159, they turn out to be 24% vs. 70%, there were higher remission in placebo group. Same situation happened to all the analysis. This could be a typo: the "Analysis 2.2" should be for H2RA but there are "PPI" on top of table.

Reply

Dear Dr Shau, Thank you very much for your feedback. Reading the number (n/N) indeed is confusing. Actually you should read 'n' as the number of participants NOT reaching a certain outcome or endpoint ‐ so in your example (study Hatlebakk 1999): 161 ‐ 39 = 122 patients on PPI reached heartburn remission, vs. 159 ‐ 111 = 48 patients on placebo. One should focus on the note just below the graph indicating what the results indicate; clearly the results were in favour of PPI. Unfortunately at that time the software (Review Manager) forced me to register my data in this way. Our review is being updated at the moment and I will see if it is possible to adjust the way the data are presented, because I agree with you it is confusing at this moment. We will also correct the 'PPI on top of the H2RA‐table', which is clearly a mistake. Once again: thank you very much for your comments. Kind regards, Bart van Pinxteren

*Note on update, November 2009: All issues raised in this feedback have now been addressed.*

Contributors

Bart van Pinxteren Mattjis Numans

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 June 2012 | New search has been performed | Searches rerun and two new studies identified and included. |

| 1 June 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Two new studies identified and included. Conclusions not changed. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1999 Review first published: Issue 2, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 September 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Review is being republished to reflect change in authorship with 2009 update. |

| 5 October 2009 | New search has been performed | Updated, 1 study added (Uemura 2008) |

| 30 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 18 May 2006 | New search has been performed | Minor update |

| 12 March 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Conclusions changed |

| 11 March 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

| 1 January 2006 | New search has been performed | New studies found and included or excluded |

Acknowledgements

This research originated from the GORD guidelines project that was initiated by the European Society for Primary Care Gastroenterology (ESPCG).

Appendices

Appendix 1. 2008 search strategy

exp gastroesophageal reflux/ gastro?esophageal reflux.tw. gastro‐esophageal reflux.tw. gastro‐oesophageal reflux.tw. exp esophagitis/ esophagitis.tw. oesophagitis.tw. reflux esophagitis.tw. reflux oesophagitis.tw. belch.tw. burp$.tw. eructation.tw. GORD.tw. GERD.tw. Bile Reflux/ (acid adj5 reflux).tw. exp dyspepsia/ dyspep$.tw. or/30‐47 exp anti‐ulcer agents/ exp omeprazole/ omeprazole.tw. lansoprazole.tw. pantoprazole.tw. rabeprazole.tw. esomeprazole.tw. exp histamine H2 antagonists/ cimetidine/ cimetidine.tw. exp ranitidine/ ranitidine.tw. exp famotidine/ famotidine.tw. exp nizatidine/ nizatidine.tw. exp domperidone/ domperidone.tw. exp metoclopramide/ metoclopramide.tw. exp cisapride/ cisapride.tw. prokinetic$.tw.

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

Summary of 2011 revisions

Step 1 to 11: filter changed to new version of Cochrane RCT filter for Medline, sensitivity – maximising strategy as per Cochrane Handbook V5. (Old RCT filter Step 1‐12 deleted)

Step 22 (duodenogastric adj2 reflux).tw. added

Step 24 (bile adj2 reflux added).tw.

Step 30 eructation.tw. added

Step 38: new subject heading proton pump inhibitors added (2008) and exploded

Step 42: ‘lansoprazole.tw’ amended to ‘(lansoprazole or lanzoprazole).tw.

Step 47: (histamine adj3 h2 adj3 antagonist$) added

Added date limit of 2006‐2008

MEDLINE Search Strategy (19 November 2008)

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1996 to November Week 1 2008>

1 randomized controlled trial.pt. (162955) 2 controlled clinical trial.pt. (32199) 3 randomized.ab. (126026) 4 placebo.ab. (64782) 5 drug therapy.fs. (619533) 6 randomly.ab. (86062) 7 trial.ab. (121278) 8 groups.ab. (517149) 9 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 (1246833) 10 humans.sh. (4721216) 11 9 and 10 (1027119) 12 exp esophagus/ (10673) 13 esophag$.tw. (32782) 14 oesophag$.tw. (9880) 15 exp gastroesophageal reflux/ (9931) 16 (gastroesophageal adj3 reflux).tw. (6381) 17 (gastro adj3 oesophageal adj3 reflux).tw. (1854) 18 (gastro adj3 esophageal adj3 reflux).tw. (429) 19 gord.tw. (406) 20 gerd.tw. (2890) 21 exp duodenogastric reflux/ (462) 22 (duodenogastric adj3 reflux).tw. (210) 23 exp bile reflux/ (193) 24 (bile adj3 reflux).tw. (327) 25 (acid adj3 reflux).tw. (1100) 26 exp dyspepsia/ (3259) 27 dyspep$.tw. (4938) 28 (belch$ or burp$).tw. (378) 29 exp eructation/ (88) 30 eructation.tw. (57) 31 exp heartburn/ (709) 32 (heartburn or indigestion).tw. (2166) 33 exp esophagitis/ (2923) 34 esophagitis.tw. (3463) 35 oesophagitis.tw. (1093) 36 exp proton pumps/ (18082) 37 (proton adj3 pump adj3 inhibitor$).tw. (4287) 38 exp proton pump inhibitors/ (330) 39 ppi.tw. (3069) 40 exp omeprazole/ (5073) 41 omeprazole.tw. (3417) 42 (lansoprazole or lanzoprazole).tw. (1196) 43 pantoprazole.tw. (647) 44 rabeprazole.tw. (504) 45 esomeprazole.tw. (436) 46 exp histamine h2 antagonists/ (4281) 47 (histamine adj3 h2 adj3 antagonist$).tw. (430) 48 cimetidine.tw. (1679) 49 exp cimetidine/ (1179) 50 famotidine.tw. (635) 51 exp famotidine/ (539) 52 nizatidine.tw. (133) 53 exp nizatidine/ (105) 54 ranitidine.tw. (1791) 55 exp ranitidine/ (1543) 56 (prokinetic adj3 agent$).tw. (369) 57 exp domperidone/ (332) 58 domperidone.tw. (426) 59 exp metoclopramide/ (916) 60 metoclopramide.tw. (1180) 61 exp cisapride/ (836) 62 cisapride.tw. (944) 63 or/12‐35 (53964) 64 or/36‐62 (32754) 65 63 and 64 (4758) 66 11 and 65 (3592) 67 pylori.ti. (15068) 68 66 not 67 (2921) 69 limit 68 to yr="2006‐2008" (694) 70 from 69 keep 1‐694 (694)

MEDLINE Search Strategy (November 2011)

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1948 to November Week 3 2011

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab.

trial.ab.

groups.ab.

or/1‐8

exp animals/ not humans.sh.

9 not 10

exp esophagus/

esophag$.tw.

oesophag$.tw.

exp gastroesophageal reflux/

(gastroesophageal adj3 reflux).tw.

(gastro adj3 oesophageal adj3 reflux).tw.

(gastro adj3 esophageal adj3 reflux).tw.

gord.tw.

gerd.tw.

exp duodenogastric reflux/

(duodenogastric adj2 reflux).tw.

exp bile reflux/

(bile adj2 reflux).tw.

(acid adj3 reflux).tw.

exp dyspepsia/

dyspep$.tw.

(belch$ or burp$).tw.

exp eructation/

eructation.tw.

exp heartburn/

(heartburn or indigestion).tw.

exp esophagitis/

esophagitis.tw.

oesophagitis.tw.

exp proton pumps/

(proton adj3 pump adj3 inhibitor$).tw.

exp proton pump inhibitors/

ppi.tw.

exp omeprazole/

omeprazole.tw.

(lansoprazole or lanzoprazole).tw.

pantoprazole.tw.

rabeprazole.tw.

esomeprazole.tw.

exp histamine h2 antagonists/

(histamine adj3 h2 adj3 antagonist$).tw.

cimetidine.tw.

exp cimetidine/

famotidine.tw.

exp famotidine/

nizatidine.tw.

exp nizatidine/

ranitidine.tw.

exp ranitidine/

(prokinetic adj3 agent$).tw.

exp domperidone/

domperidone.tw.

exp metoclopramide/

metoclopramide.tw.

exp cisapride/

cisapride.tw.

or/12‐35

or/36‐62

63 and 64

11 and 65

pylori.ti.

66 not 67

limit 68 to ed=20080101‐20111119

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

Summary of 2011 revisions

Filter subject headings updated in 2011 as follows:

exp single blind method changed to exp single blind procedure

exp double blind method changed to exp double blind procedure

exp evaluation studies changed to exp evaluation

exp prospective studies changed to exp prospective study

Step 40: (duodenogastric adj3 reflux).tw. added

Step 42: (bile adj3 reflux added).tw.

Step 48: eructation.tw. added

Step 54: exp omeprazole deleted as covered in new subject heading proton pump inhibitors exploded

Step 55 new subject heading proton pump inhibitors added (2008) and exploded

Step 56: ‘lansoprazole.tw’ amended to ‘(lansoprazole or lanzoprazole).tw. (now step 58)

Step 60 subject heading exp histamine h2 antagonists changed to exp h2 receptor antagonist added (now Step 63)

Step 64: (h2 adj3 receptor adj3 antagonist$).tw. added

Step 62: exp Cimetidine deleted as associate term to and contained within exp Histamine H2 Receptor Antagonist

Step 64: exp Famotidine deleted as associate term to and contained within exp Histamine H2 Receptor Antagonist

Step 66: exp Nizatidine deleted as associate term to and contained within exp Histamine H2 Receptor Antagonist

Step 68: exp Ranitidine deleted as associate term to and contained within exp Histamine H2 Receptor Antagonist

Added date limit of 2006 ‐2008 (as search last ran on 21/12/05)

EMBASE search strategy (19 November 2008)

Database: EMBASE <1996 to 2008 Week 46>

1 exp randomized controlled trial/ (133000) 2 randomized controlled trial$.tw. (20954) 3 exp randomization/ (24312) 4 exp single blind procedure/ (6841) 5 exp double blind procedure/ (51296) 6 or/1‐5 (170858) 7 animal.hw. (1047847) 8 human.hw. (3907249) 9 7 not (7 and 8) (901617) 10 6 not 9 (166132) 11 exp clinical trial/ (429570) 12 (clin$ adj3 (stud$ or trial$)).ti,ab,tw. (156240) 13 (clin$ adj3 trial$).ti,ab,tw. (92041) 14 ((singl$ or doubl$ or treb$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab,tw. (52701) 15 exp placebo/ (81167) 16 placebo$.ti,ab,tw. (67305) 17 random.ti,ab,tw. (56879) 18 (crossover$ or cross‐over$).ti,ab,tw. (22268) 19 or/11‐18 (599557) 20 19 not 9 (582247) 21 20 not 10 (427515) 22 exp comparative study/ (211066) 23 exp evaluation/ (53469) 24 exp prospective study/ (70096) 25 exp controlled study/ (2208077) 26 (control$ or prospective$ or volunteer$).ti,ab,tw. (1117898) 27 or/22‐26 (2740729) 28 27 not 9 (2022865) 29 10 or 21 or 28 (2256151) 30 exp esophagus/ (8629) 31 esophag$.tw. (31532) 32 oesophag$.tw. (9917) 33 exp gastroesophageal reflux/ (14014) 34 (gastroesophageal adj3 reflux).tw. (6296) 35 (gastro adj3 oesophageal adj3 reflux).tw. (1930) 36 (gastro adj3 esophageal adj3 reflux).tw. (433) 37 gord.tw. (421) 38 gerd.tw. (2956) 39 exp duodenogastric reflux/ (675) 40 (duodenogastric adj3 reflux).tw. (170) 41 exp bile reflux/ (363) 42 (bile adj3 reflux).tw. (324) 43 (acid adj3 reflux).tw. (1116) 44 exp dyspepsia/ (10754) 45 dyspep$.tw. (5038) 46 (belch$ or burp$).tw. (367) 47 exp eructation/ (191) 48 eructation.tw. (59) 49 exp heartburn/ (3729) 50 (heartburn or indigestion).tw. (2130) 51 exp esophagitis/ (7912) 52 esophagitis.tw. (3478) 53 oesophagitis.tw. (1149) 54 (proton adj3 pump adj3 inhibitor$).tw. (4749) 55 exp proton pump inhibitor/ (22842) 56 ppi.tw. (3215) 57 omeprazole.tw. (3756) 58 (lansoprazole or lanzoprozole).tw. (1333) 59 pantoprazole.tw. (800) 60 rabeprazole.tw. (537) 61 esomeprazole.tw. (536) 62 exp h2 receptor antagonist/ (21143) 63 (h2 adj receptor adj3 antagonist$).tw. (1479) 64 cimetidine.tw. (1787) 65 famotidine.tw. (747) 66 nizatidine.tw. (150) 67 ranitidine.tw. (2021) 68 exp prokinetic agent/ (1998) 69 (prokinetic adj3 agent$).tw. (415) 70 exp domperidone/ (2506) 71 domperidone.tw. (495) 72 exp metoclopramide/ (7531) 73 metoclopramide.tw. (1338) 74 exp cisapride/ (4418) 75 cisapride.tw. (1065) 76 or/30‐53 (63171) 77 or/54‐75 (48970) 78 76 and 77 (10430) 79 29 and 78 (5662) 80 pylori.ti. (14545) 81 79 not 80 (4762) 82 limit 81 to yr="2006‐2008" (1500) 83 from 82 keep 1‐1500 (1500) 84 from 83 keep 1‐1500 (1500)

EMBASE search strategy (November 2011)

Database: Embase <1980 to 2011 Week 50>

exp esophagus/

esophag$.tw.

oesophag$.tw.

exp gastroesophageal reflux/

(gastroesophageal adj3 reflux).tw.

(gastro adj3 oesophageal adj3 reflux).tw.

(gastro adj3 esophageal adj3 reflux).tw.

gord.tw.

gerd.tw.

exp duodenogastric reflux/

(duodenogastric adj3 reflux).tw.

exp bile reflux/

(bile adj3 reflux).tw.

(acid adj3 reflux).tw.

exp dyspepsia/

dyspep$.tw.

(belch$ or burp$).tw.

exp eructation/

eructation.tw.

exp heartburn/

(heartburn or indigestion).tw.

exp esophagitis/

esophagitis.tw.

oesophagitis.tw.

(proton adj3 pump adj3 inhibitor$).tw.

exp proton pump inhibitor/

ppi.tw.

omeprazole.tw.

(lansoprazole or lanzoprazole).tw.

pantoprazole.tw.

rabeprazole.tw.

esomeprazole.tw.

exp histamine H2 receptor antagonist/

(h2 adj receptor adj3 antagonist$).tw.

cimetidine.tw.

famotidine.tw.

nizatidine.tw.

ranitidine.tw.

exp prokinetic agent/

(prokinetic adj3 agent$).tw.

exp domperidone/

domperidone.tw.

exp metoclopramide/

metoclopramide.tw.

exp cisapride/

cisapride.tw.

or/1‐24

or/25‐46

47 and 48

random:.tw. or placebo:.mp. or double‐blind:.tw.

50 and 49

pylori.ti.

51 not 52

animal.hw.

human.hw.

54 not (54 and 55)

53 not 56

limit 57 to em=200846‐201150

Appendix 4. EMBR search strategy

Summary of 2011 revisions

RCT filter removed

Limited to 2006‐ 2008

Selected only Cochrane Central Trials from display menu

EBMR Search Strategy (19 November 2008)

Database: All EBM Reviews ‐ Cochrane DSR, ACP Journal Club, DARE, CCTR, CMR, HTA, and NHSEED 1 exp esophagus/ (881) 2 esophag$.tw. (3800) 3 oesophag$.tw. (2315) 4 exp gastroesophageal reflux/ (1106) 5 (gastroesophageal adj3 reflux).tw. (948) 6 (gastro adj3 oesophageal adj3 reflux).tw. (585) 7 (gastro adj3 esophageal adj3 reflux).tw. (73) 8 gord.tw. (124) 9 gerd.tw. (383) 10 exp duodenogastric reflux/ (46) 11 (duodenogastric adj3 reflux).tw. (39) 12 exp bile reflux/ (18) 13 (bile adj3 reflux).tw. (70) 14 (acid adj3 reflux).tw. (262) 15 exp dyspepsia/ (742) 16 dyspep$.tw. (1860) 17 (belch$ or burp$).tw. (114) 18 exp eructation/ (17) 19 eructation.tw. (35) 20 exp heartburn/ (216) 21 (heartburn or indigestion).tw. (823) 22 exp esophagitis/ (518) 23 esophagitis.tw. (684) 24 oesophagitis.tw. (542) 25 exp proton pumps/ (606) 26 exp proton pump inhibitors/ (0) 27 (proton adj3 pump adj3 inhibitor$).tw. (1079) 28 ppi.tw. (474) 29 exp omeprazole/ (1990) 30 omeprazole.tw. (2296) 31 (lansoprazole or lanzoprazole).tw. (773) 32 pantoprazole.tw. (416) 33 rabeprazole.tw. (271) 34 esomeprazole.tw. (234) 35 exp histamine h2 antagonists/ (3018) 36 (histamine adj3 h2 adj3 antagonist$).tw. (335) 37 cimetidine.tw. (2420) 38 exp cimetidine/ (1313) 39 famotidine.tw. (652) 40 exp famotidine/ (347) 41 nizatidine.tw. (221) 42 exp nizatidine/ (112) 43 ranitidine.tw. (2591) 44 exp ranitidine/ (1483) 45 (prokinetic adj3 agent$).tw. (140) 46 exp domperidone/ (148) 47 domperidone.tw. (344) 48 exp metoclopramide/ (879) 49 metoclopramide.tw. (1533) 50 exp cisapride/ (316) 51 cisapride.tw. (620) 52 or/1‐24 (8543) 53 or/25‐51 (10496) 54 52 and 53 (2293) 55 pylori.ti. (2362) 56 54 not 55 (1895) 57 limit 56 to yr="2006‐2008" [Limit not valid in DARE; records were retained] (342) 58 from 57 keep 1‐342 (342) 59 from 57 keep 72‐212 (141)

EBMR Search Strategy (November 2011)

EBM Reviews ‐ Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials 4th Quarter 2011

exp esophagus/

esophag$.tw.

oesophag$.tw.

exp gastroesophageal reflux/

(gastroesophageal adj3 reflux).tw.

(gastro adj3 oesophageal adj3 reflux).tw.

(gastro adj3 esophageal adj3 reflux).tw.

gord.tw.

gerd.tw.

exp duodenogastric reflux/

(duodenogastric adj3 reflux).tw.

exp bile reflux/

(bile adj3 reflux).tw.

(acid adj3 reflux).tw.

exp dyspepsia/

dyspep$.tw.

(belch$ or burp$).tw.

exp eructation/

eructation.tw.

exp heartburn/

(heartburn or indigestion).tw.

exp esophagitis/

esophagitis.tw.

oesophagitis.tw.

exp proton pumps/

exp proton pump inhibitors/

(proton adj3 pump adj3 inhibitor$).tw.

ppi.tw.

exp omeprazole/

omeprazole.tw.

(lansoprazole or lanzoprazole).tw.

pantoprazole.tw.

rabeprazole.tw.

esomeprazole.tw.

exp histamine h2 antagonists/

(histamine adj3 h2 adj3 antagonist$).tw.

cimetidine.tw.

exp cimetidine/

famotidine.tw.

exp famotidine/

nizatidine.tw.

exp nizatidine/

ranitidine.tw.

exp ranitidine/

(prokinetic adj3 agent$).tw.

exp domperidone/

domperidone.tw.

exp metoclopramide/

metoclopramide.tw.

exp cisapride/

cisapride.tw.

or/1‐24

or/25‐51

52 and 53

pylori.ti.

54 not 55

limit 56 to yr="2008 ‐Current"

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. PPI versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Heartburn remission | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Empirical treatment | 2 | 760 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.32, 0.44] |

| 1.2 Endoscopy negative reflux disease | 10 | 3710 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.65, 0.78] |

| 2 Overall improvement | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Endoscopy negative reflux disease | 5 | 1231 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.55, 0.69] |

Comparison 2. H2RA versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Heartburn remission | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Empirical treatment | 2 | 1013 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.60, 0.99] |

| 1.2 Endoscopy negative reflux disease | 2 | 514 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.74, 0.95] |

| 2 Painfree at day | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Empirical treatment | 4 | 696 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.71, 0.89] |

| 2.2 Treatment of ENRD | 1 | 381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.61, 0.93] |

| 3 Painfree at night | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Empirical treatment | 3 | 642 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.63, 0.94] |

| 3.2 Treatment of ENRD | 1 | 312 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.59, 1.08] |

| 4 Overall improvement | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Empirical treatment | 4 | 1635 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.63, 0.81] |

| 4.2 Treatment of ENRD | 2 | 514 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.13, 1.33] |

Comparison 3. Prokinetic versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Heartburn remission | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Empirical treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Painfree at day | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Empirical therapy | 2 | 428 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.51, 0.77] |

| 3 Painfree at night | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Empirical treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Overall improvement | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Empirical treatment | 2 | 429 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.56, 0.91] |

Comparison 4. PPI versus H2RA.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Heartburn remission | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Empirical treatment | 7 | 3147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.60, 0.73] |

| 1.2 Endoscopy negative reflux disease | 4 | 960 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.62, 0.97] |

| 2 Overall improvement | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Empirical treatment | 1 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.17, 0.51] |

| 2.2 Endoscopy negative reflux disease | 2 | 937 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.73, 0.93] |

Comparison 5. PPI versus prokinetic.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Heartburn remission | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Empirical treatment | 2 | 747 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.32, 0.87] |

| 1.2 Endoscopy negative reflux disease | 1 | 302 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.56, 0.92] |

Comparison 6. H2RA versus prokinetic.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Painfree at day | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Empirical treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Armstrong 2001.

| Methods | Randomised Double‐blinded ITT | |

| Participants | n = 220 Heartburn No grade 4 oesophagitis | |

| Interventions | Four weeks PAN 40 mg NIZ 150 mg bid | |

| Outcomes | Complete heartburn relief Adequate heartburn control Quality of life | |

| Notes | GORD/ENRD | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Patients were allocated to one of two treatment groups on the basis of a block design randomization list." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Stated: double‐blinded. Patients received blinded plastic bottles with placebo and identical study medication. Blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Data analysis for the primary efficacy endpoint was conducted according to the intent‐to‐treat (ITT) principle." Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups: "Seven patients randomized to nizatidine and five randomized to pantoprazole did not have symptom relief data at 28 days." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Armstrong 2005.

| Methods | Randomised Double‐blinded ITT | |

| Participants | n = 390 Heartburn | |

| Interventions | Four weeks OME 20 mg RAN 150 mg bid | |

| Outcomes | Max 1 day per week mild heartburn No heartburn GSRS | |

| Notes | GORD | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomization, using a computer‐generated table of random numbers, was concealed from patients, investigators and study personnel." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Randomization, using a computer‐generated table of random numbers, was concealed from patients, investigators and study personnel.' |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "This was a prospective, randomized, controlled, double‐blind, double‐dummy active treatment trial." Blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken: "Double‐blind dosing was maintained with an appropriate combination of active and identical‐looking placebo tablets." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups. ITT analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Bardhan 1999.

| Methods | Randomised Double‐blinded Per Protocol | |

| Participants | n = 677 Heartburn No circumferential oesophagitis | |

| Interventions | 2 weeks OME 20 mg OME 10 mg RAN 300 mg | |

| Outcomes | Asymptomatic | |

| Notes | GORD | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "The patients were allocated to treatment according to a computer generated randomisation list. At each centre patients were allocated to the next available treatment number." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blind, double‐dummy treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | No ITT data extractable. Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups: 161 (24%) continued in the study on maintenance treatment, and 197 (29%) discontinued the study at some stage mainly because of unwillingness to continue (21), adverse events (51), and loss to follow‐up (58). There were no differences with respect to these outcomes between the three initially randomised groups. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Bate 1996.

| Methods | Randomised Double‐blinded ITT | |

| Participants | n = 209 Heartburn No oesophagitis | |

| Interventions | Four weeks OME 20 mg Placebo | |

| Outcomes | Heartburn free Asymptomatic | |

| Notes | ENRD | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of concealment is not described. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Patients were randomized to receive double‐blind either omeprazole 20 mg or matched placebo capsules once daily (o.m.)." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups. "Analyses are presented on an all‐patients‐treated basis." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Bate 1997.

| Methods | Randomised Double‐blinded ITT | |

| Participants | n = 221 Heartburn No oesophageal ulcer | |

| Interventions | Four weeks OME 20 mg CIM 400 mg qid | |

| Outcomes | Heartburn‐free Max 1day per week mild heartburn | |

| Notes | GORD/ENRD | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sequence generation process not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of allocation concealment not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information other than "double‐blind" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Analyses were performed on an intention‐to‐treat basis, or using all data available from the intention‐to‐treat population" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Behar 1978.

| Methods | Randomised Double‐blinded ITT | |

| Participants | n = 94 Heartburn Bernstein positive | |

| Interventions | 8 weeks CIM 300 mg qid Placebo | |

| Outcomes | Pain‐free at day Pain‐free at night | |

| Notes | GORD | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sequence generation process not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of concealment allocation not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information other than "a double blind format was used" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | An as‐treated analysis has been performed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Bright‐Asare 1980.

| Methods | Randomised Double‐blinded ITT | |

| Participants | n = 50 Heartburn Bernstein positive | |

| Interventions | 8 weeks CIM 300 mg qid MET 10 mg qid Placebo | |

| Outcomes | Painfree at day Painfree at night | |

| Notes | GORD | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sequence generation process not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of concealment allocation not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information other than "a double blind format was used" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | An as‐treated analysis has been performed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Carlsson 1998.

| Methods | Randomised Double‐blinded ITT | |

| Participants | n = 261 Heartburn No oesophagitis | |