Abstract

Interventions aiming at reducing prehospital delay (PHD) in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) have yielded inconsistent findings. Therefore, we aimed to systematically review studies which investigated the impact of educational interventions on reducing PHD in patients with ACS. We searched four electronic databases (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane) from inception throughout December 2016 for studies that reported the impact of either mass-media or personalised intervention on PHD. Reporting quality was assessed with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist for interventional trials. Two reviewers screened 12 184 abstracts and performed full-text screening on 86 articles, leading to 34 articles which met our inclusion criteria. We found 18 educational interventions with a total of 180 914 participants (range: n=100–125 161) and a median of 1342 participants. Among these educational interventions, 13 campaigns employed a mass-media approach and five a personalised approach. Ten studies yielded no significant effects on the primary outcome while the remaining interventions reported a significant reduction with a decrease between 17 and 324 min (median reduction: 40 min, n=5). The success was partly driven by an increase in emergency medical services use. Two studies reported an increase in acute myocardial infarction knowledge. We observed no superiority of the personalised over the mass-media approach. Although methodological shortcomings and the heterogeneity of included interventions still do not allow definite recommendations for future campaigns, it becomes evident that either mass media or personalised interventions can be successful in reducing PHD, especially those who address behavioural consequences and psychological barriers (eg, denial) and provide practical action plan considerations as part of their campaign messages. CRD42017055684 (PROSPERO registration number).

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, education, public health

BACKGROUND

Therapeutic interventions for the acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are highly effective,1 but largely time-dependent2 3 resulting in 1-year mortality increase by 7.5% for every additional 30 min of prehospital delay (PHD).4 The term PHD refers to the time between acute symptom-onset and arrival at the hospital door.5 PHD can be further divided into transportation and patient-related delay,5 the latter accounting for 75% of the total PHD time.6 Symptom-related and psychology-related barriers to threat appraisal are increasingly acknowledged to hinder treatment-seeking behaviour.7 Therefore, atypical symptom-onset,8 symptom-mismatch9 and denial mechanisms10 specifically for calling emergency medical services (EMS)11 are increasingly considered when designing interventions aimed at reducing PHD.

Earlier systematic reviews have been cautious in calling past educational interventions effective in altering patient behaviour.12 13 Up to 2010, only a small number of interventions14 15 significantly decreased PHD.13 Furthermore, heterogeneity concerning study design, intervention content as well as various methodological shortcomings did not allow concise conclusions.13 A recently published review has suggested the importance of behaviour change techniques (eg, action planning) as part of educational interventions.16 However, no systematic review to date has evaluated the change of outcomes in context of the interventional approach (mass media/personalised) used. Primary outcome was PHD and the defined secondary outcomes were EMS use and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) knowledge. Given the clinical importance of reducing PHD in patients with ACS and the inconclusive findings of the previously conduced systematic reviews,12 13 16 we aimed to re-evaluate the effectiveness of educational interventions in the context of its interventional approach.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of studies investigating the effect of interventions aiming to reduce PHD in patients with ACS. We reported this investigation per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance. We presented a descriptive summary of each study in tables grouped by study design. A meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity in studies’ methods and outcomes.

Search strategies

We searched the electronic databases MEDLINE (from inception through December 2016), Cochrane library (from inception through December 2016), EMBASE (from inception through December 2016) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (from inception through December 2016) for published studies. We used a combination of free text words and keywords (eg, medical subject headings) to describe the population (such as ‘acute coronary syndrome’), the intervention (such as ‘public campaign’) and the outcome (such as ‘prehospital delay’). There were no language or study design limitations.

Eligibility criteria

We included studies that met the following criteria: (i) design: randomised controlled trials (RCTs), clinical controlled trials, prepost intervention studies and outcome studies; (ii) population: patients with ACS; (iii) intervention/exposure: public (eg, mass-media) or personalised (eg, patient-focused) interventions aimed at reducing PHDs in patients with ACS; (iv) outcome: delay time (eg, PHD time, decision time), change of behavioural response to AMI (eg, use of emergency services) and change in knowledge of AMI symptoms.

Selection of studies

Two authors (SH and LA) in duplicate screened the titles and abstracts retrieved from the searches and independently reviewed articles that potentially met the eligibility criteria. Any disagreements over which studies to include were consented by discussion, or if disagreement could not be resolved, a third author (K-HL) was consulted.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Two review authors (SH and LA) independently extracted data, using a predefined standardised data extraction tool on the following information: (i) citation details (eg, publication year); (ii) study characteristics (eg, study duration, design, setting, baseline characteristics); (iii) intervention (eg, type, timing, dose) and (iv) outcome (eg, outcome definitions, length of follow-up). Next, the risk of bias of included studies was estimated by using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (RoB 2.0) for RCTs.17 We assessed the adequacy of each item: ‘low’, ‘unclear’ or ‘high’ risk of bias. The reported quality of all included interventions was assessed with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist.18

Results

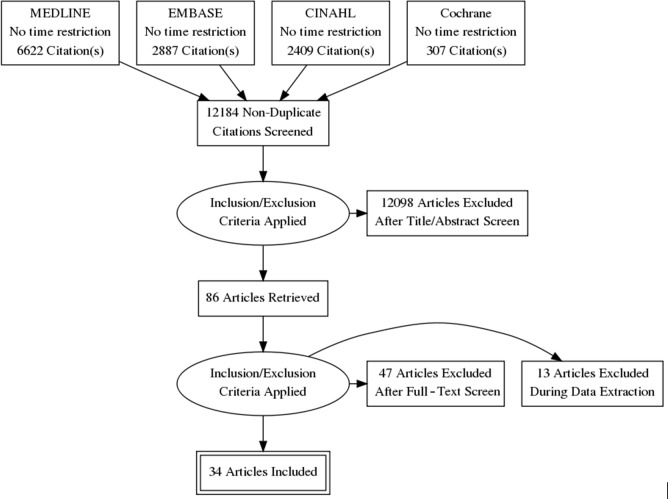

The systematic review of 12 184 articles resulted in 86 possible eligible full-text publications, of which 34 articles were finally included covering findings from a total of 18 educational interventions11 14 15 19–33 with a total of 180 914 participants (range: n=100–125 161) and a median of 1342 participants. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow chart of the study selection process, consisting of 5 RCTs,11 24 29–31 11 prepost studies14 15 21–23 25–28 32 33 and 2 outcome studies.19 20 The campaigns were carried out across eight countries in North-America (the USA,11 24–28 31 Canada33), Europe (Ireland,30 Portugal,22 Switzerland,14 23 Sweden15 21) and Australia.19 20 32 One campaign covered sites in the USA, Australia and New Zealand.29 Overall, 13 educational interventions used a mass-media approach11 14 15 19–23 26–28 32 33 and 524 25 29–31 used a personalised approach (table 1).

Figure 1.

The selection process from four databases as Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart.

Table 1.

Study and campaign characteristics of all mass-media and personalised interventions

| Key reference, total number of references, country | Study, size (no. of sites) | Inclusion diagnosis | Data collection material (time period) | Primary outcome source | Follow-up period | Method of exposure | Intervention duration | Target |

| Study details | Intervention | |||||||

| Bray et al,19 1, Australia | Outcome n=199 (1) |

ACS | I, MR (07-Nov/2013, 02-Apr/2014) | Patient | 8 m | Mass media; small media; community; internet | 5/2013 - 8/2013, 4 m | General public |

| Tummala and Farshid,20 1, Australia | Outcome n=100 (1) |

AMI | S, MR (Nov/2011- Jul/2012) | Medical record | none | Mass media; small media; internet | 2008–2012 4 y | General public |

| Thuresson et al,21 1 Sweden | Prestudy/poststudy b: n=116 a: n=122 (1) |

ACS | Q, MR, R (2002–2005, 2006–2009), | n/r | 3 y | Mass media; small media; community | 2005 1 y | General public |

| Mooney et al,30 3, Ireland | RCT*, control: n=972/137 intervention, n=972/177 (5) | ACS | Q (Oct/2007- Nov/2010) | Patient | 2 y | Motivational interview | 40 min | Patients admitted to ED with suspected ACS |

| Pereira et al,22 1, Portugal | Prestudy/poststudy b: n=201 d: n=196 (15) |

STEMI | S (05-Jun/2011, 2012) | n/r | 1 y | Mass media; small media; community; internet | 2011–2012 1 y | General public |

| Naegeli et al,23 2, Switzerland | Prestudy/poststudy b: n=5006 a: n=3900 (60; one registry) |

ACS | Q, R (2005–2006, 2007–2008) | n/r | 2 y | Mass media (only tv); small media; community; internet | 1/2007–3/2007 9/2007- 01-11-2007 4 m | General public |

| Diercks et al,26 1, USA | Prestudy/poststudy n=125 161 (>800; two registries) |

NSTEMI | MR (2002–2003, 2004–2005, 2006–2007) | Medical record | 1 y | Mass media; small media; community; internet | 2002-ongoing | Women aged 40–60 years |

| Dracup et al,29 7, USA, Australia, New Zealand | RCT*, control, n=1745/260 intervention, n=1777/305 (n/r, >6) |

IHD | Q, MR (Mar/2010- Mar/2011) | Medical record | 2 y | Motivational interview | 40 min | Patients admitted to CCU, cardiac rehabilitation, to physician practices |

| Blank and Smithline,24 2, USA | RCT* control, n=253/52 intervention, n=247/45 (1) |

Chest pain | Q (12 m) | Hospital staff | 1 y | Educational video | 5 min | Patients admitted to ED with chest pain |

| Luepker et al,11 9, USA | RCT* control, n=2175/9801 intervention, n=2876/10 563 (44) |

CHD | S, MR (Sep/1995- Mar/1996, Apr/1996-Aug/1997) | Patient | None | Mass media; small media; community | 4/1995- 9/1997, 18 m | General public, patients at risk, health professionals |

| Meischke et al,31 1, USA | RCT control, n=1343/790, intervention, n=4101/2469 (16; in one registry) |

Suspect AMI | MR (registries) (Dec/1991-Dec/1993) | Medical record | 1 y | Mass media direct mail; emotional, informative, social and control | 10/1991-01-11-1991 2 m 1991–1992 12 m | General public households with members >50 years |

| Gaspoz et al, 14 (1), Switzerland | Prestudy/poststudy b: n=1100 d: n=1295 (1) |

AMI/unstable angina | I, several MR (12 m prior/12 m during) | n/r | None | Mass media, small media, community | 1992–1993, 1 y | General public (+leaflets for senior citizens) |

| Blohm et al,15 6, Sweden | Prestudy/poststudy b: n=779 d: n=525 a: n=1256 (1) |

AMI | S, MR (Feb/1986-Oct/1987, Nov/1987-Dec/1988, Jan/1989-Dec/1991) | Patient | 3 y | Mass media (only radio and newspaper), small media, community | 1992–1993, 1 y | General public |

| Bett et al32 1, Australia | Prestudy/poststudy b: n=556 a: n=253 (22) |

Chest pain | S (1988, 1989p 1989a) | Patient | 4 w | Mass media, small media, community | 1989 1 w | General public |

| Moses et al27 1, USA27 | Prestudy/poststudy b: n=500 a1: n=668 a2: n=625 (1) |

AMI, angina chest pain | MR (during the campaign, 24 m) | Medical record | None | Mass media, small media, community | 2 y | General public |

| Ho et al,28 1, USA | Prestudy/poststudy b: n=401 a: n=489 (9) |

AMI | I (telephone), MR (Oct/1986-Feb/1987, Apr/1987-Aug/1987) | Medical record | 4.5 m | Mass media | 2/1987- 4/1987, 2 m | General public >35 years |

| Mitic and Perkins33, 1, Canada | Prestudy/poststudy b: n=101 d: n=329 a: n=41 (1) |

AMI | MR (4 w prior, 4 w during and 1 w after) | Hospital staff | 3 m | Mass media, small media, | 2 m | General public |

| Black and Brown, 1, USA25 | Prestudy/poststudy b: n=95 a: n=75 (1) |

AMI | S (Apr/1967-Aug/1970, Sep/1970-Aug/1971) | Hospital staff | 1 y | Community (public ‘heart speaker') | 1970 12 m | General public |

*Sample size calculation performed.

a, after; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; b, before; CHD, cardiac heart disease; d, during; ED, emergency department; I, interview; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; m, month; MR, medical records or hospital/patient charts; n/r, not reported; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; Q, questionnaire; R, registry; RCT, randomised controlled trial; S, survey; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; w, week; y, year.

Quality assessment of included studies

As shown in online supplementary appendix 1, the assessment of the TIDieR checklist18 on 12 quality outcomes revealed that all 18 studies adequately described the intervention (‘name’) and the rationale behind it (‘why’).11 14 15 19–33 All studies but one26 adequately reported on the intervention material (‘what’), the procedures (‘what’) and the mode of delivery (‘how’).11 14 15 19–25 27–33 Study location (‘where’) was reported in all but two studies.24 26 The time period (‘when’) was outlined in the majority of 15 (83.3%) interventions taking place.11 14 15 19–23 25 26 28–32 Only eight (61.5%) mass-media11 14 22 23 27 28 32 33 and four (80%) personalised interventions24 29–31 reported exact exposure dosages. Insufficient information on the reporting category ‘who’ (details regarding the expertise of intervention providers) was given in three (16.7%) studies.21 27 31 One study26 only provided information in the categories ‘why’, ‘when’ and ‘who’ so that we relied on the campaign website (www.hearttruth.gov) and on additional references34 for extracting further intervention details. Only three studies (16.7%) reported on ‘planned’ and enacted (‘actual’) intervention fidelity.11 29 30 A total of four (22.2%) studies applied a tailored approach11 14 29 30 as they emphasised the patient’s previous medical experiences29 30 or specifically addressed patients at risk and those receiving medical care (eg, at doctor offices).11 14 A total of six mass-media campaigns (33.3%) reported that they modified the intensity of exposure during the course of intervention14 21 23 27 or made structural changes.22 28

openhrt-2019-001175supp001.pdf (72.6KB, pdf)

Interventions using a mass-media approach

Campaign and study characteristics

Among all 18 interventions, 13 (72.2%) inquiries applied a mass-media approach11 14 15 19–23 26–28 32 33 and reached high participation rates typically including >1000 subjects11 14 15 23 26 27 (table 1). The campaign duration ranged from 1 week32 up to 4 years.20 The majority of studies was designed for the general public, however, one study targeted women aged between 40 and 60 years26 and two campaigns made additional efforts to reach high-risk patients.11 14 Information was extracted through interviews, surveys, questionnaires and from medical records. Nine (69.2%) interventions stated that the source of the primary outcome PHD were derived from patient statements,11 15 19 32 recordings by medical staff33 or through extraction from medical records.20 26–28

Intervention details for mass-media campaigns

As can be seen in table 1, all but one15 mass-media campaigns used television as a mean to convey their message.14 15 19–23 26–28 32 33 All except for one23 trial additionally used radio transmission and print media. The community was approached in public events and/or addressed via posters on public places in 10 (76.9%) interventions.11 14 15 19 21–23 26 27 32 Small media (eg, leaflets, other printed material) was used by all but one campaign.28 More recent interventions (36.5%) were accompanied by a website providing additional information.19 20 22 23 26

All 13 mass-media campaigns (displayed in table 2) emphasised symptoms of ACS.11 14 15 19–23 26–28 32 33 The importance of EMS use was highlighted in 10 (76.9%) campaigns.11 14 15 19–23 28 33 The need for fast action or/and information about timely therapy was given by all but one campaign.11 14 15 19–23 27 28 32 33 Four (30.8%) campaigns targeted people at risk, distributing leaflets to senior citizens,14 offering cardiovascular disease screenings at public places,22 provided hospital patient education for patients with cardiac heart disease11 or specifically targeted women.26 Several interventions (additionally) addressed potentially vulnerable populations by distributing written material in hospitals,14 15 19 21 26 27 doctors’ offices32 and pharmacies.14 21 Four campaigns (30.8%) gave specific action recommendations such as calling EMS after a certain time of symptom persistence11 15 or provided an action plan in form of a flow chart.19 20 Two campaigns called for specific actions (lay resuscitation,23 ‘bystander response’ to myocardial infarction symptoms11).

Table 2.

Campaign content and outcomes in the mass-media and personalised campaigns

| Study | The campaign message… | ||||||||||

| …emphasises signs and symptoms of ACS | …emphasises the importance of EMS use | …emphasises the need for fast action/therapy | …is tailored to the individual | …directly targets people at risk | …involves an action plan | …encourages the involvement of bystanders | …significantly changes… | ||||

| PHD | EMS | K | ED | ||||||||

| Mode of delivery: mass media | |||||||||||

| Bray et al19 | √ (3, 4, 5) |

√ (3, 4, 5) |

√ (3, 4, 5) |

n/r | n/r | √ (4, 5) |

n/r | √ | x | x | |

| Thuresson et al21 | √ (2, 3, 4) |

√ (2, 3, 4) |

√ (2, 3, 4) |

n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | x | √ | √ | |

| Tummala and Farshid20 | √ (3, 4, 5) |

√ (3, 4, 5) |

√ (3, 4, 5) |

n/r | n/r | √ (4, 5) |

n/r | x | x | ||

| Pereira et al22 | √ (2, 3, 4) |

√ (2, 3, 4) |

√ (2, 3, 4) |

n/r | √ (2) |

n/r | n/r | √ | √ | ||

| Naegeli et al23 | √ (2, 3, 4, 5) |

√ (2, 3, 4, 5) |

√ (2, 3, 4, 5) |

n/r | n/r | n/r | √ (2,4,5) |

√ | |||

| Diercks et al26 | √ (2, 3, 4, 5) |

n/r | n/r | n/r | √ (2, 3, 4, 5) |

n/r | n/r | x | |||

| Luepker et al11 | √ (2, 3, 4) |

√ (2, 3, 4) |

√ (2, 3, 4) |

n/r | √ (1, 2, 4) |

√ (3) |

√ (3) |

x | √ | x | |

| Gaspoz et al14 | √ (3, 4) |

√ (3, 4) |

√ (3, 4) |

n/r | √ (4) |

n/r | n/r | √ | x | √ | |

| Blohm et al15 | √ (3, 4) |

√ (3, 4) |

√ (3, 4) |

n/r | n/r | √ (3 |

n/r | √ | x | ||

| Bett et al32 | √ (3, 4) |

n/r | √ (3, 4) |

n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | x | |||

| Moses et al27 | √ (2, 3, 4,) |

n/r | √ (2, 3, 4) |

n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | x | √ | ||

| Ho et al28 | √ (3) |

√ (3) |

√ (3) |

n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | x | √ | ||

| Mitic and Perkins33 | √ (3) |

√ (3) |

√ (3) |

n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | √ | √ | ||

| Mode of delivery: personalised | |||||||||||

| Mooney et al30 | √ (1) |

√ (1) |

√ (1) |

√ (1) |

√ (1) |

√ (1, 4) |

√ (1) |

√ | x | ||

| Dracup et al29 | √ (1, 4) |

√ (1, 4) |

√ (1, 4) |

√ (1, 4) |

√ (1) |

√ (1, 4) |

√ (1) |

x | x | √ | x |

| Blank and Smithline24 | √ (1,4) |

√ (1,4) |

n/r | n/r | √ (1) |

√ (1) |

√ (1) |

x | √ | ||

| Meischke et al31 | √ (3/4) |

√ (3/4) |

√ (3/4) |

n/r | √ (4) |

n/r | √ (4) |

x | x | ||

| Black and Brown25 | √ (2) |

n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | √ (2) |

√ | x | √ | |

1=one-to-one session, 2=groups/events/CVDscreening, 3=mass media, 4=written material, 5=internet.

ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical service; K, ACS-related knowledge; n/r, not reported; PHD, prehospital delay.

Interventions using a personalised approach

Intervention characteristics

Five studies used a personalised approach24 25 29–31 by targeting patients admitted to emergency departments (ED)/chest pain units (CCU),24 29 30 during cardiac rehabilitation29 or at community events.25 Patient samples ranged between 170 and 5444 participants.25 31 The duration of the campaign periods spanned between 1 and 2 years, with the interventions themselves ranging between 5 and 40 min.24 29 30Online supplementary table A2 reports the risk of bias assessment of all five RCTs, among which four were personalised24 29–31 and one a mass-media intervention.11 In three RCTs, randomisation and concealment were described in sufficient detail.24 29 30 Detection bias was high in all five RCTs.11 24 29–31 In all five RCTs (100%), reporting and attrition biases were low.11 24 29–31

Intervention details for personalised campaigns

As shown in table 1, personalised interventions reached a selected target audience via motivational interviewing,29 30 in form of an educational video,24 educational speaker25 or were carried out through direct mail.31 As can be seen in table 2, all five interventions emphasised symptoms of ACS and four (80.0%) called out the importance of EMS use.24 29–31 The need for fast action about timely therapy was given by three (60.0%) campaigns.29–31 Two campaigns (40.0%) individualised their campaign message by addressing the patient’s specific needs and through adjusting the intervention based on the participant’s previous experiences with the medical system.29 30 Four campaigns (80.0%) primarily targeted people at risk (older age31; admitted with ACS30/chest pain24 and ischaemic heart disease29). Three (60.0%) campaigns24 29 30 suggested a stepwise action plan after AMI symptom onset, with one intervention enacting this plan with the patient via role play.30 All five interventions suggested the involvement of lay people at symptom-onset such as family members, friends or co-workers.24 25 29–31 Two interventions encouraged patients to appoint a confidant beforehand.29 30 The key messages were (additionally) displayed in written form.24 29–31

Effect on primary and secondary intervention outcomes

PHD in mass-media interventions

Among all 13 studies, a total of 6 (46.2%) interventions achieved a statistically significant PHD reduction14 15 19 22 23 33 (table 3). Four prepost studies found that a mass-media intervention was associated with a reduction of PHD by 40 min (p<0.00214; p<0.00115), by 24 min (p=0.00822) and by 17 min (p<0.00123). Awareness of the campaign message was associated with a favourable OR of 3.10 (95% CI 1.36 to 7.08, p=0.007) for an PHD ≤2 hours19 or increased number of patients seeking help within 2 hours.33

Table 3.

Reported outcomes in mass-media and personalised interventions

| Study | Prehospital delay | EMS use | Symptom knowledge | |||

| Measurement | Change | Measurement | Change | Measurement | Change | |

| Mass-media interventions | ||||||

| Bray et al19 | PHD ≤2 hours (AOR) |

+3.10 p=0.007 |

EMS use (%) |

+5 p=0.05 |

Increased ACS knowledge (%) | +1 p=0.80 |

| Thuresson et al(21 | n/r | n/r p>0.05 |

EMS use (%) |

+7.4 p=0.017 |

||

| Tummala and Farshid20 | Median (min) |

−4 p=0.81 |

EMS use (%) |

+1 p=0.87 |

||

| Pereira et al22 | Median (min) |

−24 p=0.008 |

EMS use (%) |

+24 p<0.001 |

||

| Naegeli et al23 | Median (min) |

−17 p<0.001 |

||||

| Diercks et al26 | Median (hours) |

−0.1 p=0.59 |

||||

| Luepker et al11 | Mean per year (%) |

−4.7 vs −6.8 p=0.54 |

EMS use (%) |

+20 p<0.005 |

||

| Gaspoz et al14 | Median (min) *only AMI |

−285 /−40* p<0.002 | EMS use (%) |

+2 p=NS |

||

| Blohm et al15 | Median (min) |

−40 p<0.001 |

EMS use (%) |

+3; −1 p=NS |

||

| Bett et al32 | Median (min) |

n/r p=NS |

||||

| Moses et al27 | Median (min) |

−3, +9 p=NS |

||||

| Ho et al28 | Median PD (min) |

−0.3 p=NS |

EMS use (%) |

+2 p=NS |

Increased AMI knowledge (%) | +16.5% p=0.002 |

| Mitic and Perkins33 | PHD <2 hours (%) |

+15.5 p<0.05 |

||||

| Personalised interventions | ||||||

| Mooney et al30 | Median (hours) |

−5.4 hours p≤0.001 | EMS use (%) |

−0.4 p=0.51 |

||

| Dracup et al29 | Median (min) |

−0.05 p=0.40 |

EMS use (%) |

−3 p=0.89 |

ACS Response Index Score |

Increase (n/r) p<0.0005 |

| Blank and Smithline24 | Median (min) |

−20 p=NS |

EMS use (%) |

+12 p=0.03 |

||

| Meischke et al31 | Median (min) |

+14, +4, –6 p>0.9 |

Calls to EMS (%) |

+2.9, +3, 8, +1, 1, p=NS | ||

| Black and Brown25 | PHD <1/ <2/<6 hours (%) | +111, +64, +40 p=sig. |

Symptom awareness (%) | +15–20 p=NA |

||

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; EMS, emergency medical services; n/r, not reported; NS, not significant; PD, patient delay; PHD, prehospital delay.

PHD in personalised interventions

Two (40.0%) personalised interventions achieved decreased PHD25 30 (table 3). An Irish trial reached an extraordinary reduction of PHD of 5.4 hours in the intervention group (p≤0.001)30 and a US study in the 1970s a significant increase of patients arriving within 1, 2 and 6 hours (p significant but not reported) on symptom onset.25

EMS use in mass-media and personalised interventions

Eight out of 13 studies (61.5%) examined the change in use of emergency services among mass-media campaigns.11 14 15 19–22 28 Increase in EMS use was demonstrated in three (37.5%) campaigns by 24% (p<0.00122), by 7.4% (p=0.01721) and by 20% (p<0.00511), respectively. An increase of EMS use was an outcome criterion in three out of five personalised campaigns.24 29 30 Here, only one study (33.3%) reported a significant increase in the utilisation of EMS by 12% (p=0.0324).

AMI knowledge in mass-media and personalised interventions

Knowledge of AMI interventions19 28 grew in one mass-media intervention by 16.5% (p=0.00228). Among two personalised interventions25 29 which aimed at increasing AMI knowledge, one29 significantly improved ACS-related knowledge assessed by a standardised instrument.29

Discussion

In this systematic review, we identified 18 educational interventions with 13 interventions using a mass-media and 5 a personalised approach. A total of eight studies revealed a successful reduction of PHD time,14 15 19 22 23 25 30 33 ranging between 17 and 324 min (median reduction: 40 min, n=5).14 15 22 23 25 30 Among eight successful campaigns, six had applied a mass-media approach (46.1% of all mass-media campaigns) and two a personalised approach (40.0% of all personalised campaigns). The majority of 10 (55.6%) interventions failed to reduce PHD, although, among these, three interventions significantly increased EMS use between 7.4% and 20%.11 21 24 Two campaigns significantly improved AMI knowledge.28 29 Surprisingly, among four campaigns which significantly increased EMS use, only one reduced PHD.22

Strengths of ‘successful’ interventions

Addressing less known ‘barriers’ to seeking help

More recently, campaign content changed from educating patients about chest pain14 15 to addressing more unspecific symptoms (eg, dyspnoea, sweating).19 22 23 Campaign content also incorporated the individual’s past experiences as part of a personalised approach.30 Furthermore, psychological barriers such as denial of the cardiac origin of symptoms were addressed.19 30

Targeting high-risk patients

While personalised campaigns mostly targeted patients with a history of ACS, white males remained the predominant examples in mass-media campaign clips to portray the campaign message.14 19 23 Yet, some successful mass-media campaigns moreover actively included a wider spectrum of high-risk-patients by providing CVD screening at public places to identify and educate those at risk22 and by disseminating leaflets to senior citizens via paychecks in public places.14

Involving a ‘confidant’

Most campaigns encouraged patients to act on ACS symptoms by immediately calling EMS services. Two successful personalised approach interventions25 30 emphasised the involvement of a third party by encouraging patients to inform bystanders or a ‘confidant’ of their symptoms. The negative effect of denial among bystanders of heart attack victims was also taken into consideration when discussing the delegation of a ‘confidant’.30

Educating a ‘third party’

Specific efforts were undertaken to educate ‘third party’ subjects in three successful campaigns23 25 30 by addressing ‘families, friends and co-workers’ of future heart attack victims25 through training the public in lay resuscitation23 or by encouraging the ‘confidant’ to take part of the intervention in the first place.30

Developing a stepwise action plan

Additionally to advising target audiences to call an ambulance on symptom-onset, some successful campaigns also developed a stepwise action plan anticipating the emergency situation.19 30 In one intervention, this plan was developed via role play between study nurse and participant.30

Shortcomings among all interventions

Methodological shortcomings

Only four intervention studies11 24 29 30 performed a power analysis beforehand. Some large-scale studies relied on PHD extraction by reviewing solely medical records26–29 31 (table 1)—a procedure questioned by guidelines on reporting PHD time.5 Additionally, some studies did not control for significant differences regarding baseline patient characteristics in statistical analyses.14 23

Interventional shortcomings

Taking into consideration the efforts/cost of educational interventions, the longevity of altered patient behaviour is of central interest. As reported in table 1, studies measured PHD during,11 14 20 27 between 1 and 8 months,19 28 32 33 after 122 24–26 31 and 2 years23 29 30 and two studies after a 3-year follow-up.15 21

A matter of concern is the possibility of creating false-positive cases. Some studies measured outcomes that could imply a negative campaign effect, such as the increase of ED visits in general,21 27 29 and distinguishing between an increase for cardiac versus non-cardiac origin11 14 25 27 33 during/after the campaign (table 2). Two mass-media campaigns interpreted the increase of ED visits for cardiac and non-cardiac reasons as an increase of the awareness of chest pain in the general population.25 33 One mass-media campaign showed a transient increase of ED visits for chest pain of non-cardiac origin, while the increase of ED visits due to chest pain of cardiac origin remained significant in the follow-up period,14 implying that the campaign showed the desired impact on patients at risk. Although reporting quality was adequate for most mass-media interventions, exact figures of mass-media exposure are needed for anyone who wishes to replicate the intervention and were only described in some studies.11 14 22 23 27 28 32 33

Limitations of this review

We refrained from pooling the data for a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of study designs as well as of the reported primary outcomes. It must be assumed that some unpublished studies were missed in this review. To prevent reporting bias, this review’s outcomes were defined and a review protocol registered online preceding data extraction.

Conclusion

This systematic review of 13 mass-media and 5 personalised educational interventions confirms that both approaches are able to achieve a measurable reduction in PHD. Ideally, both intervention types should harmonise their main messages for patients at risk both through mass media (including digital and social media) as well as individually as part of any physician or healthcare visit. Role play in mass media with ‘high-risk’ patient actors confronting the target audience with a spectrum of barriers (atypical symptom onset, denial of the cardiac origin of symptoms, anxiety of causing a false alarm) and demonstrating appropriate behaviour might help to internalise the campaign messages. Beyond transferring knowledge of specific heart-related symptoms, interventions should broaden their scope to address perceptional and psychological barriers of timely treatment. Family members of high-risk patients and potential witnesses should be involved in a stepwise action plan that allows to dissolve a ‘wait and see behaviour’ to call EMS.

Nevertheless, the observed heterogeneity among the included interventions highlights the necessity for standard operational procedures. From a scientific perspective, any future endeavour to design an educational intervention should be met with careful planning regarding the sample size and the method of data collection (and in particular of the primary outcome). Intervention outcomes should be evaluated in the light of potential false-positive effects and potential confounders of outcomes analysis should be controlled for.

Footnotes

Contributors: SH made manual investigations to identify existing literature on the topic. SH and LA designed the review and outlined a search protocol, which was registered on PROSPERO. LA conducted the search for literature. LA and SH screened all titles and abstracts using RAYYAN. Full-text versions were screened for eligibility by SH and LA and data were extracted in an excel sheet. K-HL was included in all decisions regarding eligibility. LA, SH and K-HL drafted the manuscript. SH finalised the manuscript. SH, LA and K-HL take responsibility for all aspects of reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

Funding: This research was partly funded (8810002296) by the German Heart Foundation (Deutsche Herzstiftung) to Professor K-HL.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, TIMI Study Group . Selecting the best reperfusion strategy in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: it's all a matter of time. Circulation 2003;108:2828–30. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000106684.71725.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver WD. Time to thrombolytic treatment: factors affecting delay and their influence on outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;25:S3–9. 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00108-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Indications for fibrinolytic therapy in suspected acute myocardial infarction: collaborative overview of early mortality and major morbidity results from all randomised trials of more than 1000 patients. Fibrinolytic therapy Trialists' (FTT) Collaborative group. Lancet 1994;343:311–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91161-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP, et al. Time delay to treatment and mortality in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: every minute of delay counts. Circulation 2004;109:1223–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121424.76486.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackay MH, Ratner PA, Nguyen M, et al. Inconsistent measurement of acute coronary syndrome patients' pre-hospital delay in research: a review of the literature. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2014;13:483–93. 10.1177/1474515114524866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen C-H, Munck A, Kragstrup J, et al. Patient delay from onset of chest pain suggesting acute coronary syndrome to hospital admission. Scand Cardiovasc J 2003;37:183–6. 10.1080/14017430310014920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladwig K-H, Gärtner C, Walz LM, et al. [The inner barrier: how health psychology concepts contribute to the explanation of prehospital delays in acute myocardial infarction: a systematic analysis of the current state of knowledge]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2009;59:440–5. 10.1055/s-2008-1067576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Donnell S, McKee G, Mooney M, et al. Slow-onset and fast-onset symptom presentations in acute coronary syndrome (ACS): new perspectives on prehospital delay in patients with ACS. J Emerg Med 2014;46:507–15. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirchberger I, Heier M, Golüke H, et al. Mismatch of presenting symptoms at first and recurrent acute myocardial infarction. from the MONICA/KORA myocardial infarction registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:377–84. 10.1177/2047487315588071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang XY, Albarqouni L, von Eisenhart Rothe AF, et al. Is denial a maladaptive coping mechanism which prolongs pre-hospital delay in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction? J Psychosom Res 2016;91:68–74. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luepker RV, Raczynski JM, Osganian S, et al. Effect of a community intervention on patient delay and emergency medical service use in acute coronary heart disease: the rapid early action for coronary treatment (react) trial. JAMA 2000;284:60–7. 10.1001/jama.284.1.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kainth A, Hewitt A, Sowden A, et al. Systematic review of interventions to reduce delay in patients with suspected heart attack. Emerg Med J 2004;21:506–8. 10.1136/emj.2003.013276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mooney M, McKee G, Fealy G, et al. A review of interventions aimed at reducing pre-hospital delay time in acute coronary syndrome: what has worked and why? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2012;11:445–53. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaspoz JM, Unger PF, Urban P, et al. Impact of a public campaign on pre-hospital delay in patients reporting chest pain. Heart 1996;76:150–5. 10.1136/hrt.76.2.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blohm M, Hartford M, Karlson BW, et al. A media campaign aiming at reducing delay times and increasing the use of ambulance in AMI. Am J Emerg Med 1994;12:315–8. 10.1016/0735-6757(94)90147-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farquharson B, Abhyankar P, Smith K, et al. Reducing delay in patients with acute coronary syndrome and other time-critical conditions: a systematic review to identify the behaviour change techniques associated with effective interventions. Open Heart 2019;6:e000975 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Sterne JA, Savović J, et al. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;10:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bray JE, Stub D, Ngu P, et al. Mass media campaigns' influence on prehospital behavior for acute coronary syndromes: an evaluation of the Australian heart Foundation's warning signs campaign. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:e001927 10.1161/JAHA.115.001927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tummala SR, Farshid A. Patients' understanding of their heart attack and the impact of exposure to a media campaign on pre-hospital time. Heart Lung Circ 2015;24:4–10. 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.07.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thuresson M, Haglund P, Ryttberg B, et al. Impact of an information campaign on delays and ambulance use in acute coronary syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:297–8. 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereira H, Pinto FJ, Calé R, et al. Stent for life in Portugal: this initiative is here to stay. Rev Port Cardiol 2014;33:363–70. 10.1016/j.repc.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naegeli B, Radovanovic D, Rickli H, et al. Impact of a nationwide public campaign on delays and outcome in Swiss patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2011;18:297–304. 10.1177/1741826710389386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blank FSJ, Smithline HA. Evaluation of an educational video for cardiac patients. Clin Nurs Res 2002;11:403–16. 10.1177/105477302237453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black LA, Brown DD. Public information and heart attack. Report of an educational program. Ohio State Med J 1973;69:369–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diercks DB, Owen KP, Kontos MC, et al. Gender differences in time to presentation for myocardial infarction before and after a national women's cardiovascular awareness campaign: a temporal analysis from the can rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients suppress adverse outcomes with early implementation (crusade) and the National cardiovascular data registry acute coronary treatment and intervention outcomes Network-Get with the guidelines (NCDR action Registry-GWTG). Am Heart J 2010;160:80–7. 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moses HW, Engelking N, Taylor GJ, et al. Effect of a two-year public education campaign on reducing response time of patients with symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1991;68:249–51. 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90753-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho MT, Eisenberg MS, Litwin PE, et al. Delay between onset of chest pain and seeking medical care: the effect of public education. Ann Emerg Med 1989;18:727–31. 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80004-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dracup K, McKinley S, Riegel B, et al. A randomized clinical trial to reduce patient prehospital delay to treatment in acute coronary syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009;2:524–32. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.852608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mooney M, McKee G, Fealy G, et al. A randomized controlled trial to reduce prehospital delay time in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). J Emerg Med 2014;46:495–506. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meischke H, Dulberg EM, Schaeffer SS, et al. 'Call fast, call 911': a direct mail campaign to reduce patient delay in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Public Health 1997;87:1705–9. 10.2105/AJPH.87.10.1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bett N, Aroney G, Thompson P. Impact of a national educational campaign to reduce patient delay in possible heart attack. Aust N Z J Med 1993;23:157–61. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1993.tb01810.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitic WR, Perkins J. The effect of a media campaign on heart attack delay and decision times. Can J Public Health 1984;75:414–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long T, Taubenheim A, Wayman J, et al. "The Heart Truth:" Using the Power of Branding and Social Marketing to Increase Awareness of Heart Disease in Women. Soc Mar Q 2008;14:3–29. 10.1080/15245000802279334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2019-001175supp001.pdf (72.6KB, pdf)