Abstract

Background

Polypharmacy is an important issue in the care of older patients with cancer, as it increases the risk of unfavorable outcomes. We estimated the prevalence of polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use, and drug–drug interactions (DDIs) in older patients with cancer in Korea and their associations with clinical outcomes.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

This was a secondary analysis of a prospective observational study of geriatric patients with cancer undergoing first‐line palliative chemotherapy. Eligible patients were older adults (≥70 years) with histologically diagnosed solid cancer who were candidates for first‐line palliative chemotherapy. All patients enrolled in this study received a geriatric assessment (GA) at baseline. We reviewed the daily medications taken by patients at the time of GA before starting chemotherapy. PIMs were assessed according to the 2015 Beers criteria, and DDIs were assessed by a clinical pharmacist using Lexi‐comp Drug Interactions. We evaluated the association between polypharmacy and clinical outcomes including treatment‐related toxicity, and hospitalization using logistic regression and Cox regression analyses.

Results

In total, 301 patients (median age 75 years; range, 70–93) were enrolled; the most common cancer types were colorectal cancer (28.9%) and lung cancer (24.6%). Mean number of daily medications was 4.7 (±3.1; range, 0–14). The prevalence of polypharmacy (≥5 medications) was 45.2% and that of excessive polypharmacy (≥10 medications) was 8.6%. PIM use was detected in 137 (45.5%) patients. Clinically significant DDIs were detected in 92 (30.6%) patients. Polypharmacy was significantly associated with hospitalization or emergency room (ER) visits (odds ratio: 1.73 [1.18–2.55], p < .01). Neither polypharmacy nor PIM use showed association with treatment‐related toxicity.

Conclusion

Polypharmacy, PIM use, and potential major DDIs were prevalent in Korean geriatric patients with cancer. Polypharmacy was associated with a higher risk of hospitalization or ER visits during the chemotherapy period.

Implications for Practice

This study, which included 301 older Korean patients with cancer, highlights the increased prevalence of polypharmacy in this population planning to receive palliative chemotherapy. The prevalence of polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy was 45.2% and 8.6%, respectively. The prescription of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) was detected in 45.5% and clinically significant drug–drug interaction in 30.6% of patients. Given the association of polypharmacy with increased hospitalization or emergency room visits, this study points to the need for increased awareness and intervention to minimize polypharmacy in the geriatric cancer population undergoing chemotherapy. Moreover, specific criteria for establishing PIMs should be adopted for the treatment of older adults with cancer.

Keywords: Polypharmacy, Potentially inappropriate medication, Drug–drug interactions, Aged, Cancer, Chemotherapy

Short abstract

There is limited information on polypharmacy in Asian older adults with metastatic cancer, especially for those undergoing palliative chemotherapy. This article reports on the prevalence of polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medication use, and potential drug‐drug interactions in older patients with cancer in Korea.

Introduction

Polypharmacy is defined as the concurrent use of five or more medications and has emerged as a significant public health issue, especially given the increasingly aging population 1. Moreover, trends in the U.S. and U.K. suggest a gradual increase in drug use in older age groups 2, 3. Polypharmacy could be even more important in older adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy, who tend to be more vulnerable to adverse effects of medications than older adults without cancer 4, 5, 6. This is because such patients are already taking several medications for managing comorbidities and may need additional medications for primary cancer care and supportive care. The prevalence of polypharmacy has been reported to range widely from 29.3% to 80% 7, 8, which is related to the increased use of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) 9, drug–drug interactions (DDIs) 10, 11, 12, 13, adverse drug events 14, hospitalizations 15, treatment toxicity 16, 17, 18, and mortality 5, 19 in geriatric patients with cancer.

There are several screening tools to evaluate the “appropriateness” of medication use such as the Beers criteria, Medication Appropriateness Index, START/STOPP criteria (Screening Tool of Older Person's Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment), HEDIS DAE (Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set Drugs to Avoid in the Elderly), and Zhan criteria 4. Among them, the Beers criteria is the most recently updated and widely used tool for older adults and has been endorsed by the American Geriatrics Society 20. The updated Beers criteria of 2015 include five categories: PIMs in older adults, PIMs due to drug‐related disease or syndrome, PIMs to be used with caution, DDIs, and PIMs based on kidney function 20. According to these criteria, PIM use in geriatric patients with cancer was reported to range from 24.8% to 48.1% 15, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25.

Moreover, drug interactions may be highly prevalent for the geriatric oncology population, and this situation warrants further attention with respect to polypharmacy, especially for patients undergoing chemotherapy. Indeed, patients with newly diagnosed cancer are likely to receive additional medications and chemotherapeutic agents within a narrow therapeutic window, and the major DDIs in these populations have been reported to range from 33% to 69% 10, 11, 12, 13.

Although the older population is increasing worldwide, there is a particularly rapid increase occurring in Korea. As of 2017, people older than 65 years accounted for 13.8% of the total Korean population, and this proportion is expected to increase to 41% by 2060 26. Several studies on polypharmacy have been conducted for the general Korean population. Kim et al. 27 reported that 86.4% of older adults were receiving polypharmacy, and Park et al. 1 reported that an average of 6.4 drugs were prescribed per month to Korean individuals aged 65 years or older. These statistics indicate that the rate of polypharmacy is also high in older Korean people. There are two studies related to PIM use in older Korean people without cancer and the results are conflicting: one study demonstrated that 81% of the subjects were prescribed at least one PIM 28, whereas the other showed that 27.6% of older outpatients were taking at least one PIM 29. The main reason for this difference could be attributed to the difference in population. The former was based on the nationwide claim data including all drugs prescribed in multiple hospitals visited during the study period, and the latter was based on the outpatient data from one tertiary hospital. To date, only Park et al. demonstrated an effect of polypharmacy and PIM use on treatment‐related toxicity in older patients in Korea, in patients with nonmetastatic head and neck cancer (HNC). They found that neither polypharmacy nor PIM were significantly associated with treatment‐related toxicity, but these were associated with modest increases in prolonged hospitalization and noncancer health events 15.

Overall, there is limited information on polypharmacy and other related measures in Asian older adults with metastatic cancer, especially for those undergoing palliative chemotherapy. Therefore, to fill this important knowledge gap, the aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of polypharmacy, PIM use, and potential DDIs in older patients with cancer starting chemotherapy. We also investigated the association between these measures and clinical outcomes such as chemotherapy related toxicities, hospitalization, and survival.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

Study Design and Participants

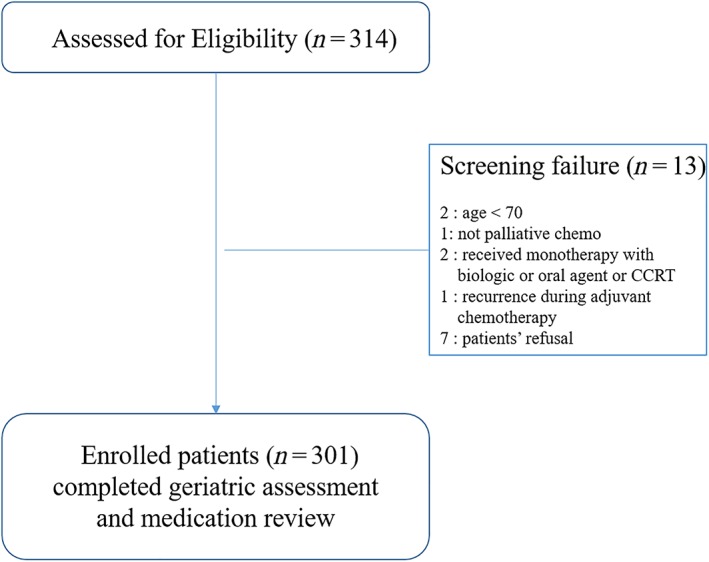

This is a secondary analysis of a prospective observational study for geriatric patients with cancer aged ≥70 years (Korean Cancer Study Group PC13‐09, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform number: KCT0001071) undergoing first‐line palliative chemotherapy, which was designed to identify predictive factors of grade 3–5 toxicities of chemotherapy 30. The patients were recruited for the study from 17 hospitals across Korea between February 2014 and December 2015, resulting in the enrollment of 301 patients. Eligible patients included older adults (≥70 years) with solid cancer who were candidates for first‐line palliative chemotherapy. The exclusion criteria included hematologic malignancy, patients who had a treatment plan to receive monotherapy with a biological or oral agent or concurrent chemoradiotherapy, and recurrent cases within 6 months from curative surgery 30. All patients received a geriatric assessment (GA) after providing informed consent and before beginning first‐line palliative chemotherapy; information on medication use was collected during this assessment (Fig. 1). As in our previous studies, GA was defined as evaluating medical problems, mobility, social support and functional, and cognitive, nutritional, and emotional status 30, 31. Impaired GA was defined as deficits in at least two out of six domains (activities of daily living [ADL], Korean‐instrument ADL, Mini‐Mental Status Examination in the Korean version of the Consortium, Short‐Form Geriatric Depression Scale, the Mini Nutritional Assessment, and Timed Get Up and Go test). Geriatric interventions according to assessment results were left to the investigator's discretion, and there was no intervention guideline. Enrolled patients provided a list of all prescribed medications being taken at the time of GA. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each institution, and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of enrolled patients of Korean Cancer Study Group PC 13‐09 cohort.Abbreviation: CCRT, concurrent chemo‐radiotherapy.

Outcome Measurements

Polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy were defined as taking 5 or more and 10 or more medications, respectively 24, 25. We included only scheduled prescribed medications and excluded herbal or over‐the‐counter (OTC) drugs. Medication review was assessed based on the number of drugs taken, but dosage and frequency were not included in the original assessment. Information on the use of daily medications was reviewed as a part of GA, and PIM use was assessed based on the 2015 Beers criteria 20. Although the updated Beers criteria include medication classes for specific disease conditions, we only considered medication classes that should be generally avoided for most older adults, irrespective of the underlying disease. Although they are otherwise classified as inappropriate by the Beers criteria, medications typically used to alleviate chemotherapy‐induced nausea such as metoclopramide were excluded from this analysis. In addition to PIMs, high‐risk medication classes for adverse drug events were assessed based on the following six categories previously identified to increase hospitalization risk in the older population: anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, opioids, and antiarrhythmic drugs 32, 33.

Finally, we assessed potential DDIs during the period of chemotherapy. DDIs were screened using the well‐validated clinical software system Lexi‐comp Drug Interactions (Lexi‐Comp, Inc., Hudson, OH) 10, 34, 35 and reviewed by a clinical pharmacist. This system categorizes DDIs into five subgroups and provides clinical recommendations. Among them, major clinical DDIs are considered in category D and X, interpreted as “consider therapy modification” and “avoid combination,” respectively. While assessing drug interactions, we additionally included chemotherapeutic agents and antiemetic drugs because reliable assessment of DDIs is important for chemotherapy monitoring and management.

Clinical Outcome Variables

Chemotherapy‐related toxicity was assessed from starting date of first‐line chemotherapy until 28 days after the last chemotherapy date by the National Cancer Institute's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0. Grade (G) 3–5 chemotherapy‐related toxicity was dichotomized (yes or no). We also collected information on hospitalization or emergency room (ER) visits during the treatment. We defined index event as the first hospitalization or ER visit after chemotherapy before subsequent cycle of chemotherapy regardless of number of hospitalization or ER visits. The time to event outcome was defined from the date of first chemotherapy to the date of index event of the first hospitalization or ER visit. Hospitalization or ER visit event within 30 days after starting chemotherapy was assessed, as was cumulative incidence of hospitalization or ER visit during first‐line chemotherapy period. Overall survival was calculated from the date of enrollment to the date of death or last follow‐up.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed to examine the patients’ baseline characteristics and prevalence of polypharmacy, PIM use, high‐risk medication uses, and potential DDIs. Drug measures such as polypharmacy, PIM use, high‐risk medication, and DDIs were dichotomized or categorized.

Associations with polypharmacy and other baseline factors were evaluated by the chi‐square test, and the odds ratio was calculated by logistic regression. The multivariable model included variables that showed significance in univariate analysis with p < .05 (comorbidity, Instrumental Activity of Daily Living [IADL], PIM use, high‐risk medication, and DDIs) and variables clinically considered as potential confounders: age, sex, and performance status (PS). In intercorrelation analysis, the Spearman correlation coefficient was used for evaluating relationships of polypharmacy and other measures, and the Cramer's V coefficient was used to assess relationships among PIM use, high‐risk medications, and DDIs.

A logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between drug measures and treatment‐related toxicity. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyze factors related to time to event of ER visit or hospitalization. The regression model included variables such as age, sex, PS, comorbidity, and polypharmacy. In addition, we estimated the cumulative incidence using the Fine and Gray competing risk regression model and compared events according to polypharmacy. Survival analysis was estimated using the Kaplan‐Meier method and compared using the log‐rank test.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

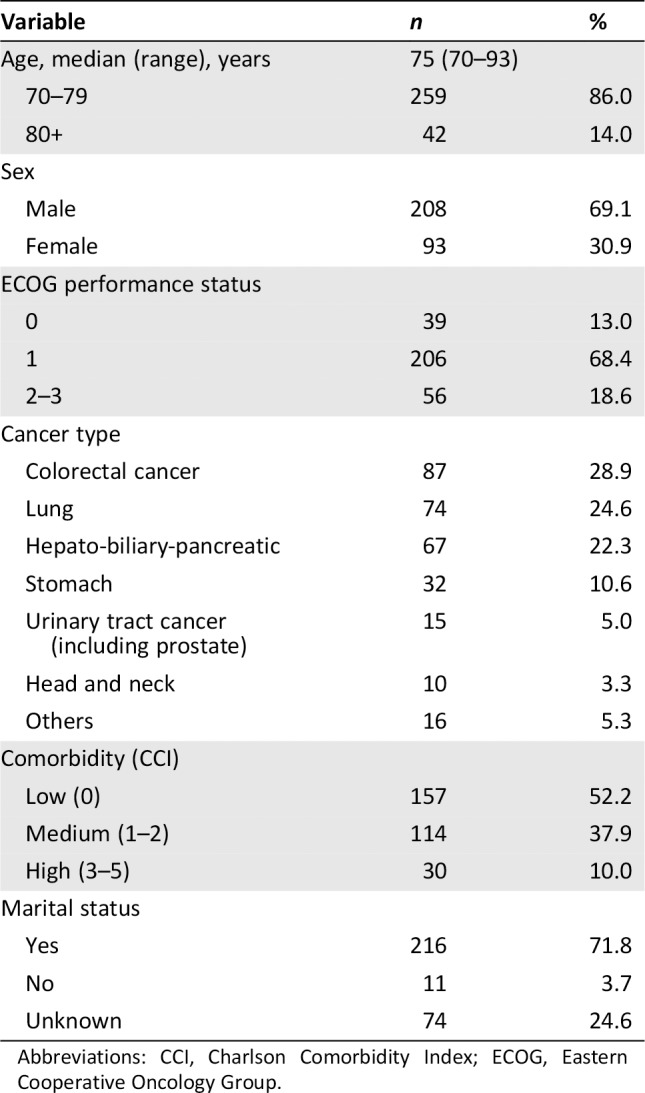

A total of 301 patients with cancer who were older than 70 years of age were enrolled in this study. The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 75 years (range, 70–93), with 14% of the patients older than 80 years. More than two thirds of the patients were male. The majority of patients (81.4%) showed good performance status with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) ≤1, and 97% of the patients had a stage IV cancer. The most common cancer types were colorectal cancer (28.9%), lung cancer (24.6%), and hepato‐biliary‐pancreatic cancer (22.3%). Baseline GA showed that 26.2% of the cases were not impaired and 73.8% of patients had impaired GA. Other information on patients is summarized in detail in the original study on this population 30.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics included in the geriatric assessment (n = 301)

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), years | 75 (70–93) | |

| 70–79 | 259 | 86.0 |

| 80+ | 42 | 14.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 208 | 69.1 |

| Female | 93 | 30.9 |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 39 | 13.0 |

| 1 | 206 | 68.4 |

| 2–3 | 56 | 18.6 |

| Cancer type | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 87 | 28.9 |

| Lung | 74 | 24.6 |

| Hepato‐biliary‐pancreatic | 67 | 22.3 |

| Stomach | 32 | 10.6 |

| Urinary tract cancer (including prostate) | 15 | 5.0 |

| Head and neck | 10 | 3.3 |

| Others | 16 | 5.3 |

| Comorbidity (CCI) | ||

| Low (0) | 157 | 52.2 |

| Medium (1–2) | 114 | 37.9 |

| High (3–5) | 30 | 10.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Yes | 216 | 71.8 |

| No | 11 | 3.7 |

| Unknown | 74 | 24.6 |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

All patients received palliative chemotherapy according to cancer types. The median number of chemotherapy treatments received was four cycles (range, 25%–75%, 2–7 cycles). Five patients were lost to follow‐up after chemotherapy, so adverse events could not be collected. A total of 274 (91.0%) patients received combination chemotherapy, and 24 (8.0%) patients received single intravenous cytotoxic chemo agent. Toxicity of G3 or above was observed in 53.8% of the patients; hematologic and nonhematologic adverse events occurred in 37.2% and 37.9% of the patients, respectively. Hospitalization or ER visits due to toxicity were reported in 123 patients (40.9%) during the first‐line chemotherapy.

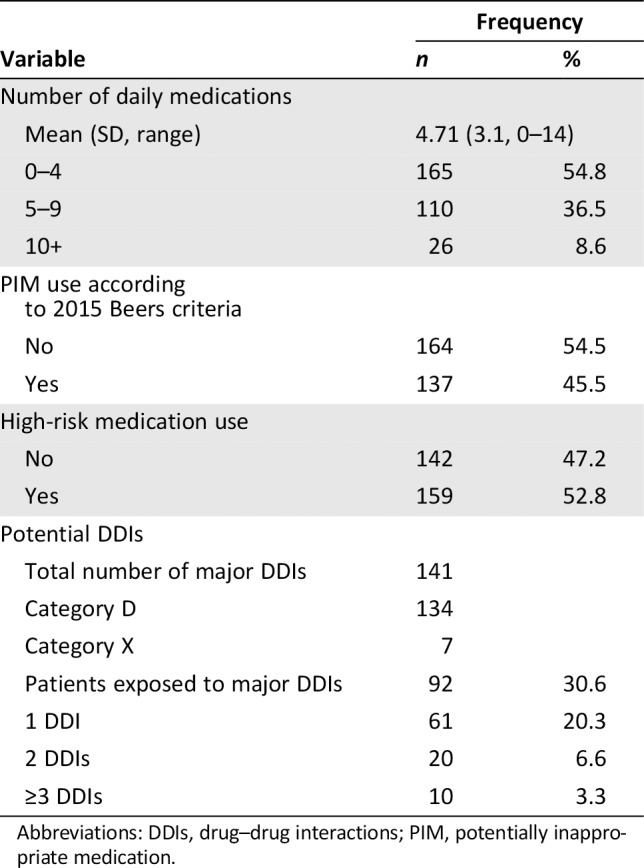

Number of Daily Medications

Overall, the patients were taking a total of 1,417 medications before starting chemotherapy (Table 2). The prevalence of polypharmacy was 45.2% (n = 136). Excessive polypharmacy (i.e., 10 or more medications) was detected in 8.6% of the patients. The four most commonly used medications were drugs acting on the gastrointestinal system (53.5%), cardiovascular system (52.8%), and endocrine system (42.5%) and analgesic drugs (32.9%).

Table 2.

Prevalence of polypharmacy, inappropriate medication use, and DDIs

| Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % |

| Number of daily medications | ||

| Mean (SD, range) | 4.71 (3.1, 0–14) | |

| 0–4 | 165 | 54.8 |

| 5–9 | 110 | 36.5 |

| 10+ | 26 | 8.6 |

| PIM use according to 2015 Beers criteria | ||

| No | 164 | 54.5 |

| Yes | 137 | 45.5 |

| High‐risk medication use | ||

| No | 142 | 47.2 |

| Yes | 159 | 52.8 |

| Potential DDIs | ||

| Total number of major DDIs | 141 | |

| Category D | 134 | |

| Category X | 7 | |

| Patients exposed to major DDIs | 92 | 30.6 |

| 1 DDI | 61 | 20.3 |

| 2 DDIs | 20 | 6.6 |

| ≥3 DDIs | 10 | 3.3 |

Abbreviations: DDIs, drug–drug interactions; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication.

Inappropriate Medication Use

According to the 2015 Beers criteria, 175 PIM uses were detected. A total of 137 (45.5%) patients used at least one PIM as defined by the Beers criteria, 24.8% of whom were taking more than two PIMs. The most frequently prescribed PIMs were megestrol acetate, proton pump inhibitors, sulfonylurea, and benzodiazepines (supplemental online Table 1). A total of 238 medications were included in the list of the six high‐risk medications taken by 159 (52.8%) patients. The two most commonly used medications in this category were opioids and antiplatelet agents (supplemental online Table 2).

Potential DDIs

The pharmacist identified 141 major potential DDIs out of the 1,417 total medications, the majority of which were classified as category D (supplemental online Table 2). Thirty subjects (10.0%) were prescribed drugs with two or more potential DDIs. The most frequently identified category D DDIs were opioids–opioids or opioids–central nervous system drugs. There were 30 major DDIs identified involving chemotherapeutic agents (27 of category D and 3 of category X). In terms of category X, two patients were taking two alpha‐1 blockers simultaneously, which might cause hypotension or syncope. Three patients receiving irinotecan chemotherapy involved drug interaction with CYP3A4 metabolism. Two other patients taking levosulpiride had drug interactions with hydrochlorothiazide and clidinium‐chlorodiazepoxide (supplemental online Table 3).

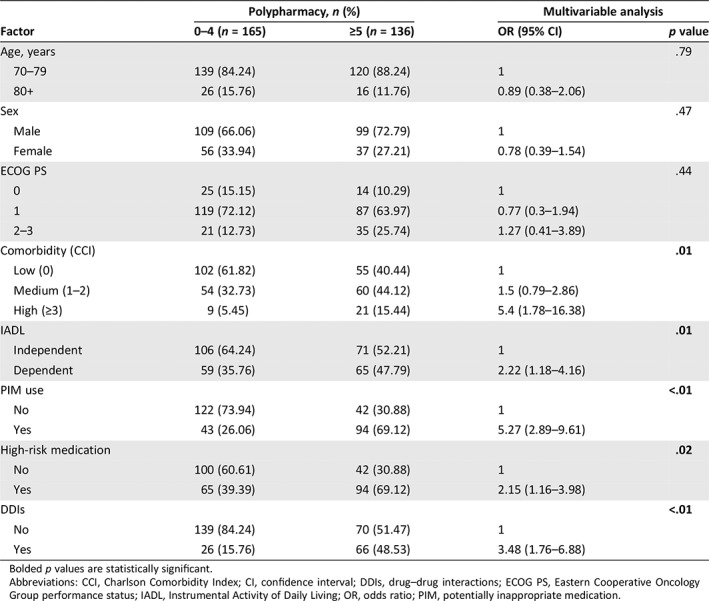

Factors Associated with Polypharmacy, PIMs, and DDIs

Polypharmacy and PIM use were significantly intercorrelated (Spearman's rho 0.43, supplemental online Table 4). In the multivariable analysis, polypharmacy was independently associated with high comorbidity compared with having a low Charlson Comorbidity Index, dependent IADL index compared with being independent, PIM use, high‐risk medications, and DDIs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with polypharmacy

| Factor | Polypharmacy, n (%) | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 (n = 165) | ≥5 (n = 136) | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age, years | .79 | |||

| 70–79 | 139 (84.24) | 120 (88.24) | 1 | |

| 80+ | 26 (15.76) | 16 (11.76) | 0.89 (0.38–2.06) | |

| Sex | .47 | |||

| Male | 109 (66.06) | 99 (72.79) | 1 | |

| Female | 56 (33.94) | 37 (27.21) | 0.78 (0.39–1.54) | |

| ECOG PS | .44 | |||

| 0 | 25 (15.15) | 14 (10.29) | 1 | |

| 1 | 119 (72.12) | 87 (63.97) | 0.77 (0.3–1.94) | |

| 2–3 | 21 (12.73) | 35 (25.74) | 1.27 (0.41–3.89) | |

| Comorbidity (CCI) | .01 | |||

| Low (0) | 102 (61.82) | 55 (40.44) | 1 | |

| Medium (1–2) | 54 (32.73) | 60 (44.12) | 1.5 (0.79–2.86) | |

| High (≥3) | 9 (5.45) | 21 (15.44) | 5.4 (1.78–16.38) | |

| IADL | .01 | |||

| Independent | 106 (64.24) | 71 (52.21) | 1 | |

| Dependent | 59 (35.76) | 65 (47.79) | 2.22 (1.18–4.16) | |

| PIM use | <.01 | |||

| No | 122 (73.94) | 42 (30.88) | 1 | |

| Yes | 43 (26.06) | 94 (69.12) | 5.27 (2.89–9.61) | |

| High‐risk medication | .02 | |||

| No | 100 (60.61) | 42 (30.88) | 1 | |

| Yes | 65 (39.39) | 94 (69.12) | 2.15 (1.16–3.98) | |

| DDIs | <.01 | |||

| No | 139 (84.24) | 70 (51.47) | 1 | |

| Yes | 26 (15.76) | 66 (48.53) | 3.48 (1.76–6.88) | |

Bolded p values are statistically significant.

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI, confidence interval; DDIs, drug–drug interactions; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; IADL, Instrumental Activity of Daily Living; OR, odds ratio; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication.

Factors Associated with Clinical Outcomes

There was no significant association between the evaluated drug measures, including polypharmacy, PIM use, and DDIs, and G3 or G4 chemotherapy‐related toxicity. As a reference group using 0–4 daily medications, patients with 5–9 medications showed odds ratio (OR) = 1.13 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.7–1.83), and patients with ≥10 medications showed OR = 1.78 (95% CI: 0.75–4.22) for G3 or G4 toxicity, but the effect was not statistically significant (p = .42).

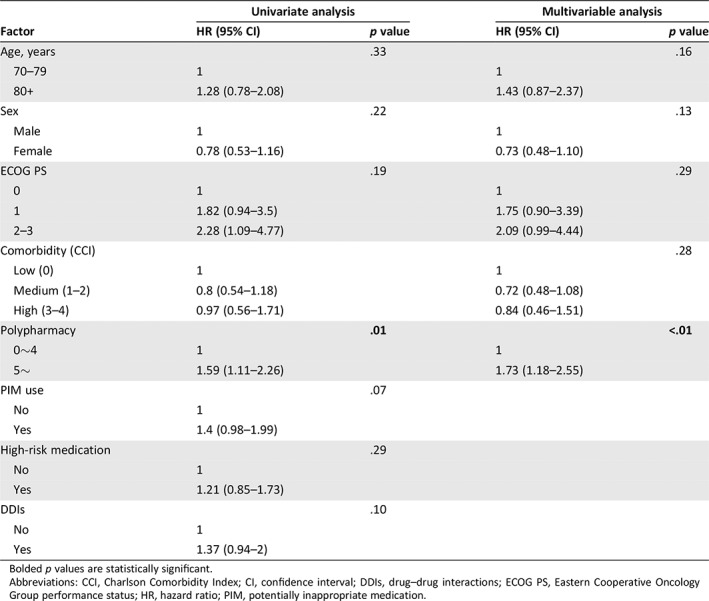

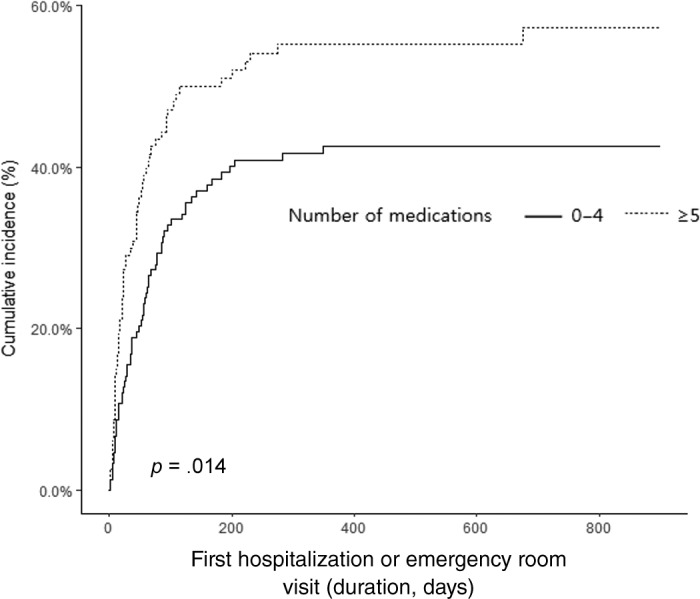

Only polypharmacy emerged as a statistically significant factor predicting time to first hospitalization or ER visits in multivariable analysis (Table 4). Cox regression model showed that polypharmacy was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization or ER visit (hazard ratio = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.18–2.55, p < .01; Table 4). In terms of hospitalization or ER visit within 30 days of starting chemotherapy, 13.5% of the nonpolypharmacy group and 24.2% of the polypharmacy group had events within 30 days (p = .03). However, for the events after 30 days of starting chemotherapy, there was no significant difference between the two groups (p = .87). Patients in the polypharmacy group had higher cumulative incidence of hospitalization or ER visit than those in the nonpolypharmacy group (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Multivariable models analyzing factors associated time to event (hospitalization or emergency room visit)

| Factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age, years | .33 | .16 | ||

| 70–79 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 80+ | 1.28 (0.78–2.08) | 1.43 (0.87–2.37) | ||

| Sex | .22 | .13 | ||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.78 (0.53–1.16) | 0.73 (0.48–1.10) | ||

| ECOG PS | .19 | .29 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1.82 (0.94–3.5) | 1.75 (0.90–3.39) | ||

| 2–3 | 2.28 (1.09–4.77) | 2.09 (0.99–4.44) | ||

| Comorbidity (CCI) | .28 | |||

| Low (0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Medium (1–2) | 0.8 (0.54–1.18) | 0.72 (0.48–1.08) | ||

| High (3–4) | 0.97 (0.56–1.71) | 0.84 (0.46–1.51) | ||

| Polypharmacy | .01 | <.01 | ||

| 0∼4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 5∼ | 1.59 (1.11–2.26) | 1.73 (1.18–2.55) | ||

| PIM use | .07 | |||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.4 (0.98–1.99) | |||

| High‐risk medication | .29 | |||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.21 (0.85–1.73) | |||

| DDIs | .10 | |||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.37 (0.94–2) | |||

Bolded p values are statistically significant.

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI, confidence interval; DDIs, drug–drug interactions; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication.

Figure 2.

Comparison of cumulative incidence curves of event according to polypharmacy.

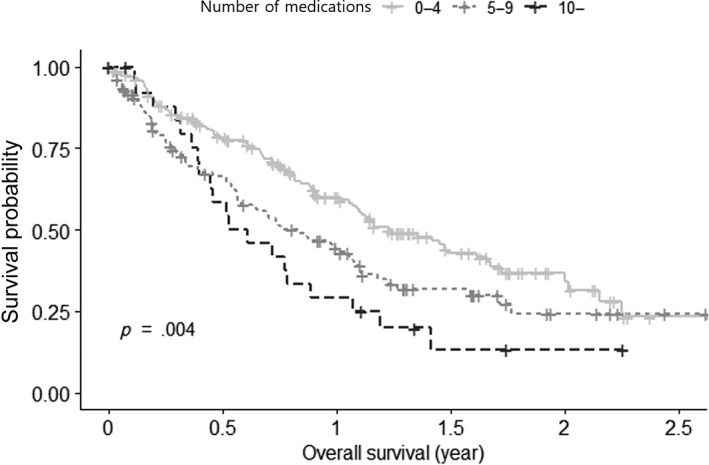

Unadjusted survival analysis indicated that the number of medications was associated with a significant survival difference (p = .004). As a reference group using 0–4 daily medications, the polypharmacy group (5–9 medications) had a hazard ratio of 1.51 (95% CI: 1.09–2.08), and the excessive polypharmacy group (≥10 medications) had a hazard ratio of 2.04 (95% CI: 1.25–3.32) for mortality (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Association between polypharmacy and overall survival (Kaplan‐Meier analysis).

Discussion

This is the first study to comprehensively assess and confirm the high prevalence of polypharmacy, PIM use, and potential major DDIs in older patients with cancer undergoing palliative first‐line chemotherapy in eastern Asia. We demonstrated a high prevalence of polypharmacy (45.2%), PIM use (45.5%), high‐risk medication use (53.2%), and major potential DDIs (30.6%).

Polypharmacy was significantly correlated with increased PIM use, high‐risk medication use, and drug interactions. Several previous studies simultaneously assessed polypharmacy, PIM use, and DDIs in older adults with cancer. Alkan et al. 35 reported frequencies of 30.8% polypharmacy, 35.1% severe drug interactions, and 26.6% PIM use in 445 older patients with cancer (286 outpatients and 159 inpatients). Only 38.1% of the participants had metastatic cancer in this study, and approximately 30% of the patients did not receive chemotherapy. Leger et al. 36 evaluated three drug measures in 122 patients with hematologic malignancy, showing high prevalence of polypharmacy (75.4%), PIM use (34.4%), and DDIs (71.3%). Mostafa et al. 37 reported high prevalence of polypharmacy (88%), PIM (55%), and potential drug interaction (55%) and no association with dose intensity of chemotherapy in older adults with advanced cancer.

Polypharmacy is an essential component of GA and must be evaluated before starting chemotherapy 38; however, there are insufficient polypharmacy data in geriatric patients with cancer, especially in Asia, with the highest rate of aging in the world along with an increased risk of drug interaction owing to the popular use of herbal medications 39, 40. Our patients took a mean of 4.7 daily medications, which is lower than that observed in previous studies 5, 24, 41. This difference is probably related to different operational definitions of polypharmacy between studies and the fact that all the patients in our study were in a relatively good condition as they were candidates for chemotherapy (ECOG PS of 0 or 1 in 81.4% of patients). We excluded the use of herbal medication or OTC drugs, which may add to the cause of a lower number of medications taken than that reported in other studies. Nevertheless, the rate of excessive polypharmacy was 8.6%, which is similar to that reported in other studies 24, 42. The previously reported prevalence of polypharmacy ranged from 30% to 80% in older patients with solid cancer 7.

In line with previous studies, we found that polypharmacy was significantly associated with the IADL index and comorbidities 5, 25, 41, 43. In addition, drug measures, including polypharmacy, PIM use, high‐risk medications, and DDIs, were significantly related to each other. This is a reasonable finding and can explain the increased risk of drug interactions with greater numbers of medications, especially in older adults receiving chemotherapy, which has a narrow therapeutic window. Moreover, older people have age‐related physiological and pharmacokinetic changes and are relatively more vulnerable to concurrent medications 44.

PIM use was more prevalent in our study than reported previously, ranging from 20% to 48% 21, 23, 24. These differences might be related to the evaluation tools among studies. We used the updated 2015 Beers criteria, which could detect more PIM use than the prior version of Beers criteria 42. Similar to our study, Reis et al. 22 reported a prevalence of PIM use of 48.1% based on the 2015 Beers criteria in older patients with cancer with parenteral chemotherapy. In their study, the most commonly used PIMs were proton pump inhibitors (33.3%), metoclopramide (10.5%), benzodiazepines (10.5%), and antidepressants (7.6%). In our study, the second most common PIM was proton pump inhibitors (27.7%). The long‐term use of proton pump inhibitors was added as an inappropriate medication in the updated 2015 Beers criteria because of the risk of Clostridium difficile infection, bone loss, and fractures 20. The most common PIM was megestrol acetate (37.2%), which was newly added to the Beers criteria from the 2012 update 45 but was not reported as a frequently prescribed PIM in Western data. Jang et al. 46 investigated the PIMs in 652,192 older Korean adults using the 2012 Beers criteria and found that megestrol ranked fourth (9.8%) among all PIMs in the study population. However, they also found that megestrol was the most commonly used PIM (64.1%) among the 13,117 patients with cancer. This highlights that older Korean adults with cancer are taking megestrol more frequently than other populations, in which benzodiazepines and anticholinergics are reported as the top‐ranking PIMs. It is likely that megestrol is more widely used in Korean patients with cancer even before starting chemotherapy because it helps to relieve the anorexia‐cachexia syndrome of cancer and is also covered by the national insurance plan for patients with metastatic cancer. However, as mentioned in the Beers criteria, this drug should be cautiously prescribed to older patients because of an increased risk of thrombotic events and a minimal effect of weight gain 20. We further evaluated six high‐risk medication classes known to be associated with an increased risk of hospitalization in older adults (anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, opioids, and antiarrhythmic drugs), but we could not find any association between use of those six high‐risk medications and treatment toxicity or hospitalization/ER visits. However, many of our patients were taking opioids, which were the main causative drugs of serious potential DDIs.

Overall, 30.6% of all enrolled patients had a risk of major potential DDIs, including chemotherapeutic agents. We regarded major DDIs as those in category D and X out of the five classifications of Lexi‐comp Drug Interactions. The prevalence of DDIs in this population also varied compared with the ranges reported previously 10. Such variation is likely due to differences in the definition of major DDIs, software used for detection, cancer types of the patients, and treatment patterns.

The effects of polypharmacy or PIM use on cancer treatment outcomes remain controversial, with various results put forward. Maggiore et al. 24 reported no impact of polypharmacy and PIM use on chemotherapy‐related toxicity or hospitalization in a geriatric oncology population. Similarly, neither polypharmacy nor PIM use was significantly associated with treatment‐related toxicity in older Korean patients with HNC receiving definitive treatment 15, and no association between PIM use and adverse outcomes (ER visits, hospitalization, and death) was observed in older adults with breast and colorectal cancers receiving adjuvant chemotherapy 21. However, some studies showed associations between polypharmacy and G3–4 chemotherapy‐related toxicities in ovarian cancer and breast cancer, respectively 16, 17. We did not find any association between drug measures and treatment G3–4 toxicities (both hematologic and nonhematologic toxicity), although patients with polypharmacy had a 1.73 times higher risk of hospitalization or ER visits.

The reason why polypharmacy was associated with increased hospitalization or ER visit, despite no association with chemotherapy toxicity, is not clear in our study. The causes of ER visit or hospitalization may be more complex and can be due to toxicity of chemotherapy, symptoms from cancer itself, worsening of comorbid conditions, or all of the above. There is a possibility that polypharmacy or PIM use was associated with patients potentially having a poorer health status; thus, these patients were intrinsically more likely to be hospitalized and have worse survival outcomes. Polypharmacy was independently associated with high comorbidity and dependent IADL in our study, which are reported to be important risk factors of functional decline after chemotherapy and poor outcome after chemotherapy 47, 48, 49. However, PIM uses were not associated with any clinical outcomes in this study. Polypharmacy may have acted as a surrogate marker of comorbidity and functional dependence that resulted in increased number of hospitalization or ER visits, rather than polypharmacy itself causing drug‐induced complication or chemotherapy toxicity. The fact that there was no association between PIM use or high‐risk medication and ER visit also supports this hypothesis. Despite lack of clear explanation for the causes, our results could aid health professionals to raise the level of caution for those patients with polypharmacy and leverage systematic measures to reduce polypharmacy, PIM use, and DDIs. Measures to decrease polypharmacy could include deprescribing or intervention by pharmacist or coordinating physician. The randomized clinical trial by Kutner et al. 50 showed that discontinuation of statin was possible and safe, and it might have positive effects on improving quality of life and reducing medication costs. In order to achieve deprescription, health professionals should overcome some barriers such as doctor's attitude 51 in balancing the benefit and harms of drugs and patient's fear of cessation of drugs 52.

In terms of survival, the polypharmacy group showed poorer overall survival in our study. Although there are several studies that assessed the relationship between polypharmacy and survival, the results are inconsistent. In older patients with ovarian cancer, there was no association of polypharmacy with overall survival 16, and polypharmacy did not influence overall survival in patients receiving palliative radiotherapy 41. However, in national health insurance senior cohort data, polypharmacy was associated with elevated mortality risk in older adults in Korea 53. Although our data is an interesting finding, caution should be adopted because our survival analysis was based on univariate analysis only and further studies are needed to determine whether polypharmacy is an independent risk factor of poorer survival.

This study has several limitations. First, because it is a secondary analysis of a GA observational study, we were not able to obtain comprehensive information on drug use, including nonprescription medications such as alternative, complementary, or other herbal medications, which may have led to an underestimation of polypharmacy. Second, we only investigated baseline medications at the beginning of chemotherapy and could not collect data related to drug compliance, dosage, and frequency of medications. Third, there may have been some limitations in adopting the Beers criteria for geriatric patients with cancer, because several supportive agents for managing patients with cancer are frequently considered PIMs. Therefore, a modified version of the Beers criteria for geriatric patients with cancer might be needed. Fourth, we enrolled 301 patients in total, but there was a lack of information about how many older patients were approached in each hospital, thus limiting an understanding of enrollment rates for this study. Therefore, the generalization of the results may be limited because the characteristics of the patients agreeing to participate and those of the rejecting patient may be different. Lastly, although this was a prospectively designed cohort study, the patients were treated and prescribed at the discretion of their physicians; thus, inappropriate medications could not be prevented, even after GA. This highlights the importance of intervention involving a geriatric oncology multidisciplinary team. For example, some recent pilot studies showed that pharmacist‐led assessment and intervention was a feasible and effective option for reducing medication‐related problems 54, 55, 56. In addition, educating the patients and training the oncologists are other options for intervention. For example, the EMPOWER trial showed that educational intervention effectively decreased the use of benzodiazepines 57. These interventions would also help reduce polypharmacy and consequent costs.

Despite these limitations, our study confirmed a high prevalence of polypharmacy, PIM use, and DDIs in older adults with cancer in a relatively homogenous first‐line palliative setting in Korea. Polypharmacy was a significant risk factor for increased hospitalization or ER visit during first‐line chemotherapy, which can aid health professionals to increase the level of caution and use prophylactic and proactive measure to prevent hospitalization when giving palliative chemotherapy. Further studies would be needed not only to identify inappropriate medications but also to make an intervention strategy to reduce futile medications in older patients with cancer.

Conclusion

Polypharmacy and PIM use were found to be very prevalent in the Korean geriatric cancer population. Nearly half and one third of older adults with cancer were exposed to PIMs and major DDIs in our study, respectively. These drug measures were not associated with chemotherapy‐related toxicity, although polypharmacy significantly increased the risk of hospitalization or ER visits during chemotherapy and was associated with poorer overall survival in older patients with cancer. Overall, these findings indicate the need for further efforts toward encouraging intervention for reducing prescriptions in older adults with cancer.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Jee Hyun Kim

Provision of study material or patients: Soojung Hong, Kwang‐Il Kim, Jin Won Kim, Se Hyun Kim, Yun‐Gyoo Lee, In Gyu Hwang, Jin Young Kim, Su‐Jin Koh, Yoon Ho Ko, Seong Hoon Shin, In Sook Woo, Tae‐Yong Kim, Ji Yeon Baek, Hyun Jung Kim, Hyo Jung Kim, Myung Ah Lee, Jung Hye Kwon, Yong Sang Hong, Hun‐Mo Ryoo, Jee Hyun Kim

Collection and/or assembly of data: Soojung Hong, Ju Hyun Lee, Eun Kyeong Chun, Jee Hyun Kim

Data analysis and interpretation: Soojung Hong, Ju Hyun Lee, Jee Hyun Kim

Manuscript writing: Soojung Hong, Jee Hyun Kim

Final approval of manuscript: Soojung Hong, Ju Hyun Lee, Eun Kyeong Chun, Kwang‐Il Kim, Jin Won Kim, Se Hyun Kim, Yun‐Gyoo Lee, In Gyu Hwang, Jin Young Kim, Su‐Jin Koh, Yoon Ho Ko, Seong Hoon Shin, In Sook Woo, Tae‐Yong Kim, Ji Yeon Baek, Hyun Jung Kim, Hyo Jung Kim, Myung Ah Lee, Jung Hye Kwon, Yong Sang Hong, Hun‐Mo Ryoo, Jee Hyun Kim

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Tables

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry for Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (1720150).

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Park HY, Ryu HN, Shim MK et al. Prescribed drugs and polypharmacy in healthcare service users in South Korea: An analysis based on National Health Insurance Claims data. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016;54:369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS et al. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999‐2012. JAMA 2015;314:1818–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez‐Santiago V et al. The rising tide of polypharmacy and drug‐drug interactions: Population database analysis 1995‐2010. BMC Med 2015;13:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whitman AM, DeGregory KA, Morris AL et al. A comprehensive look at polypharmacy and medication screening tools for the older cancer patient. The Oncologist 2016;21:723–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Turner JP, Shakib S, Singhal N et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in older people with cancer. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:1727–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Turner JP, Jamsen KM, Shakib S et al. Polypharmacy cut‐points in older people with cancer: How many medications are too many? Support Care Cancer 2016;24:1831–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nightingale G, Skonecki E, Boparai MK. The impact of polypharmacy on patient outcomes in older adults with cancer. Cancer J 2017;23:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. LeBlanc TW, McNeil MJ, Kamal AH et al. Polypharmacy in patients with advanced cancer and the role of medication discontinuation. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:e333–e341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sharma M, Loh KP, Nightingale G et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in geriatric oncology. J Geriatr Oncol 2016;7:346–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nightingale G, Pizzi LT, Barlow A et al. The prevalence of major drug‐drug interactions in older adults with cancer and the role of clinical decision support software. J Geriatr Oncol 2018;9:526–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Popa MA, Wallace KJ, Brunello A et al. Potential drug interactions and chemotoxicity in older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Geriatr Oncol 2014;5:307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Leeuwen RW, Swart EL, Boven E et al. Potential drug interactions in cancer therapy: A prevalence study using an advanced screening method. Ann Oncol 2011;22:2334–2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Girre V, Arkoub H, Puts MT et al. Potential drug interactions in elderly cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2011;78:220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fede A, Miranda M, Antonangelo D et al. Use of unnecessary medications by patients with advanced cancer: Cross‐sectional survey. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1313–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park JW, Roh JL, Lee SW et al. Effect of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications on treatment and posttreatment courses in elderly patients with head and neck cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2016;142:1031–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Woopen H, Richter R, Ismaeel F et al. The influence of polypharmacy on grade III/IV toxicity, prior discontinuation of chemotherapy and overall survival in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2016;140:554–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamaker ME, Seynaeve C, Wymenga AN et al. Baseline comprehensive geriatric assessment is associated with toxicity and survival in elderly metastatic breast cancer patients receiving single‐agent chemotherapy: Results from the OMEGA study of the Dutch breast cancer trialists' group. Breast 2014;23:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sasaki T, Fujita K, Sunakawa Y et al. Concomitant polypharmacy is associated with irinotecan‐related adverse drug reactions in patients with cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2013;18:735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Freyer G, Geay JF, Touzet S et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment predicts tolerance to chemotherapy and survival in elderly patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: A GINECO study. Ann Oncol 2005;16:1795–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel . American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2227–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karuturi MS, Holmes HM, Lei X et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in older patients with breast and colorectal cancer. Cancer 2018;124:3000–3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reis CM, Dos Santos AG, de Jesus Souza P et al. Factors associated with the use of potentially inappropriate medications by older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 2017;8:303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saarelainen LK, Turner JP, Shakib S et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in older people with cancer: Prevalence and correlates. J Geriatr Oncol 2014;5:439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maggiore RJ, Dale W, Gross CP et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults with cancer undergoing chemotherapy: Effect on chemotherapy‐related toxicity and hospitalization during treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1505–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prithviraj GK, Koroukian S, Margevicius S et al. Patient characteristics associated with polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing of medications among older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 2012;3:228–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Korea S and KDi Seoul. Statistics of the aged for 2017. Available at http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/3/index.board?. Accessed November 11, 2019.

- 27. Kim HA, Shin JY, Kim MH et al. Prevalence and predictors of polypharmacy among Korean elderly. PLoS One 2014;9:e98043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nam YS, Han JS, Kim JY et al. Prescription of potentially inappropriate medication in Korean older adults based on 2012 Beers Criteria: A cross‐sectional population based study. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lim YJ, Kim HY, Choi J et al. Potentially inappropriate medications by Beers Criteria in older outpatients: Prevalence and risk factors. Korean J Fam Med 2016;37:329–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim JW, Lee YG, Hwang IG et al. Predicting cumulative incidence of adverse events in older patients with cancer undergoing first‐line palliative chemotherapy: Korean Cancer Study Group (KCSG) multicentre prospective study. Br J Cancer 2018;118:1169–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim YJ, Kim JH, Park MS et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in Korean elderly cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2011;137:839–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marcum ZA, Amuan ME, Hanlon JT et al. Prevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N et al. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2002–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lopez‐Martin C, Garrido Siles M, Alcaide‐Garcia J et al. Role of clinical pharmacists to prevent drug interactions in cancer outpatients: A single‐centre experience. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36:1251–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alkan A, Yasar A, Karci E et al. Severe drug interactions and potentially inappropriate medication usage in elderly cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leger DY, Moreau S, Signol N et al. Polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medications and drug‐drug interactions in geriatric patients with hematologic malignancy: Observational single‐center study of 122 patients. J Geriatr Oncol 2018;9:60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mohamed MR, Mohile SG, Xu H et al. Associations of medication measures and geriatric impairments with chemotherapy dose intensity in older adults with advanced cancer: A University of Rochester NCI Community Oncology Research Program study. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(suppl 15):e22034a. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maggiore RJ, Gross CP, Hurria A. Polypharmacy in older adults with cancer. The Oncologist 2010;15:507–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Su D, Li L. Trends in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: 2002‐2007. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2011;22:296–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang Y, Wang H, Wan Y et al. Using Chinese herbal medicine among cancer survivors: Data from a community hospital in China. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(suppl 3):e284a. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nieder C, Mannsaker B, Pawinski A et al. Polypharmacy in older patients ≥70 years receiving palliative radiotherapy. Anticancer Res 2017;37:795–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang X, Zhou S, Pan K et al. Potentially inappropriate medications in hospitalized older patients: A cross‐sectional study using the Beers 2015 criteria versus the 2012 criteria. Clin Interv Aging 2017;12:1697–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pamoukdjian F, Aparicio T, Zelek L et al. Impaired mobility, depressed mood, cognitive impairment and polypharmacy are independently associated with disability in older cancer outpatients: The prospective Physical Frailty in Elderly Cancer Patients (PF‐EC) cohort study. J Geriatr Oncol 2017;8:190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Klotz U. Pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism in the elderly. Drug Metab Rev 2009;41:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel . American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:616–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jang IY, Lee YS, Jeon MK et al. Potentially inappropriate medications in elderly outpatients by the 2012 version of Beers Criteria: A single tertiary medical center experience in South Korea. J Korean Geriatr Soc 2013;17:126–133. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen H, Cantor A, Meyer J et al. Can older cancer patients tolerate chemotherapy? A prospective pilot study. Cancer 2003;97:1107–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kenis C, Decoster L, Bastin J et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: A multicenter prospective study. J Geriatr Oncol 2017;8:196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hoppe S, Rainfray M, Fonck M et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving first‐line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3877–3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH Jr et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life‐limiting illness: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C et al. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I et al. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: A systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013;30:793–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cheong SJ, Yoon JL, Choi SH et al. The effect of polypharmacy on mortality in the elderly. Korean J Fam Pract 2016;6:643–650. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Whitman A, DeGregory K, Morris A et al. Pharmacist‐led medication assessment and deprescribing intervention for older adults with cancer and polypharmacy: A pilot study. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:4105–4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nipp RD, Ruddy M, Fuh CX et al. Pilot randomized trial of a pharmacy intervention for older adults with cancer. The Oncologist 2019;24:211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nightingale G, Hajjar E, Pizzi LT et al. Implementing a pharmacist‐led, individualized medication assessment and planning (iMAP) intervention to reduce medication related problems among older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 2017;8:296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R et al. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: The EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:890–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Tables