Abstract

Background

Platinum resistance is an important cause of clinical recurrence and death for ovarian cancer. This study tries to systematically explore the molecular mechanisms for platinum resistance in ovarian cancer and identify regulatory genes and pathways via text mining and other methods.

Methods

Genes in abstracts of associated literatures were identified. Gene ontology and protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis were performed. Then co-occurrence between genes and ovarian cancer subtypes were carried out followed by cluster analysis.

Results

Genes with highest frequencies are mostly involved in DNA repair, apoptosis, metal transport and drug detoxification, which are closely related to platinum resistance. Gene ontology analysis confirms this result. Some proteins such as TP53, HSP90, ESR1, AKT1, BRCA1, EGFR and CTNNB1 work as hub nodes in PPI network. According to cluster analysis, specific genes were highlighted in each subtype of ovarian cancer, indicating that various subtypes may have different resistance mechanisms respectively.

Conclusions

Platinum resistance in ovarian cancer involves complicated signaling pathways and different subtypes may have specific mechanisms. Text mining, combined with other bio-information methods, is an effective way for systematic analysis.

Keywords: Platinum resistance, Ovarian cancer, Text mining

Background

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal cause of all gynecological malignancies [1]. Due to lack of specific symptoms, the majority of patients (60%) are diagnosed at advanced stages and the five-year survival rate is about 30% [2, 3]. Nowadays cytoreducitve surgery combined with chemotherapy has been accepted as a standard treatment of this disease, where platinum-based agents such as cisplatin and carboplatin are considered to be the essential components of most chemotherapy regimens [4–6]. Initial response rate to such first-line chemotherapy is as high as 65–80%. However, about half of these patients eventually develop platinum resistance, leading to an unfavorable prognosis [2]. Presently, platinum-resistance is a major obstacle in the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Although a plenty of genes and pathways have been investigated for platinum resistance in ovarian cancer, mechanisms of drug resistance are still not fully understood. Most researchers examined only a small part of genes, meanwhile the majority of them focused on specific subtypes of ovarian cancer. As platinum resistance seems to be regulated by sophisticate molecular networks, we try to systematically assess reported genes with text mining and other bioinformatics methods, quantitatively describe their relationships and make prediction of potential regulatory molecules and pathways in this study.

Methods

The methods for data preparation and gene identification have been described previously [7]. Briefly, Ovarian cancer AND (cisplatin OR carboplatin) were used as retrieval statement on Pubmed and 6160 literatures were listed (up to July 24th, 2017). All abstracts were collected from PubMed retrieval system. Genes and proteins were identified with ABNER (V1.5) [8, 9] and were verified based on Entrez Gene Database. To cover the description of cisplatin and carboplatin, words and shorthands such as “platinum”, “platin”, “cisplatin”, “DDP”, “carboplatin” and “CBP” were selected. Similarly, both “resistance” and “resistant” were identified. Only the genes that co-appeared with these two groups of words in the same sentence will be treated. If a gene appeared several times in one sentence, it would be counted once. Word frequency analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel 2010. Gene ontology analysis was carried with FunRich (V3.0) software [10] and p-value were corrected with Bonferroni method.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis was performed using Cytoscape (V3.4.0). Plugins such as BisoGenet [11] and CytoNCA [12] were used to generate network, while interaction information from MINT [13], BIND [14, 15], BioGrid [16], DIP [17], IntAct [18] and HPRD [19] were used for analysis. All interactions were based on experiments. Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed between genes and cancer subtypes (“serous”, “mucinous”, “endometrioid”, “clear cell cancer” or “OCCC”) using HemI (V1.0) [20] with maximum distance similarity metric. Data were normalized for each subtype in advance.

Results

Platinum-resistance related genes in ovarian cancer

According to the criterion of frequency analysis, 473 genes were identified within 6160 abstracts and top genes among them (count≥15) were listed in Table 1. TP53 were mentioned more than 100 times, while ABCB1, AKT1, ERCC1 and other genes were also widely studied in the past years.

Table 1.

The top platinum-resistance related genes based on text mining

| Gene | Description | Count |

|---|---|---|

| TP53 | tumor protein p53 | 108 |

| ABCB1 | ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1 | 64 |

| AKT1 | AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 | 59 |

| ERCC1 | ERCC excision repair 1, endonuclease non-catalytic subunit | 40 |

| BCL2 | BCL2, apoptosis regulator | 28 |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor | 27 |

| BRCA1 | BRCA1, DNA repair associated | 26 |

| PIK3CA | phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha | 25 |

| MAPK1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | 24 |

| ABCC1 | ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 1 | 22 |

| IL6 | interleukin 6 | 20 |

| NFKB1 | nuclear factor kappa B subunit 1 | 20 |

| STAT3 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 | 19 |

| MTOR | mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase | 18 |

| PARP1 | poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 | 17 |

| TNFSF10 | TNF superfamily member 10 | 17 |

| BRCA2 | BRCA2, DNA repair associated | 15 |

| HDAC1 | histone deacetylase 1 | 15 |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor | 15 |

Only the genes that co-appeared with drug name (such as “cisplatin”) and phenomenons (such as “resistance”) in the same sentence will & be treated

Gene ontology analysis

To explore the functions of these genes, gene ontology (GO) analysis was carried out. Significant biological processes that may involve (corrected p < 0.05) in platinum resistance were shown in Table 2. Apoptosis were highlighted as the most significant process, while signal transduction, cell communication, cell cycle, anti-apoptosis, and nucleobase & nucleic acid metabolism were also included.

Table 2.

Significant biological process (GO analysis) for platinum resistance in ovarian cancer

| Biological Process | Number of Genes | Corrected P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | 31 | 6.64 × 10− 13 |

| Signal transduction | 154 | 5.19 × 10−08 |

| Cell communication | 143 | 9.82 × 10−07 |

| Regulation of cell cycle | 8 | 0.012 |

| Anti-apoptosis | 6 | 0.020 |

| Regulation of nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism | 99 | 0.024 |

All 473 identified genes were treated as input. P values were corrected with Bonferroni method

PPI network analysis

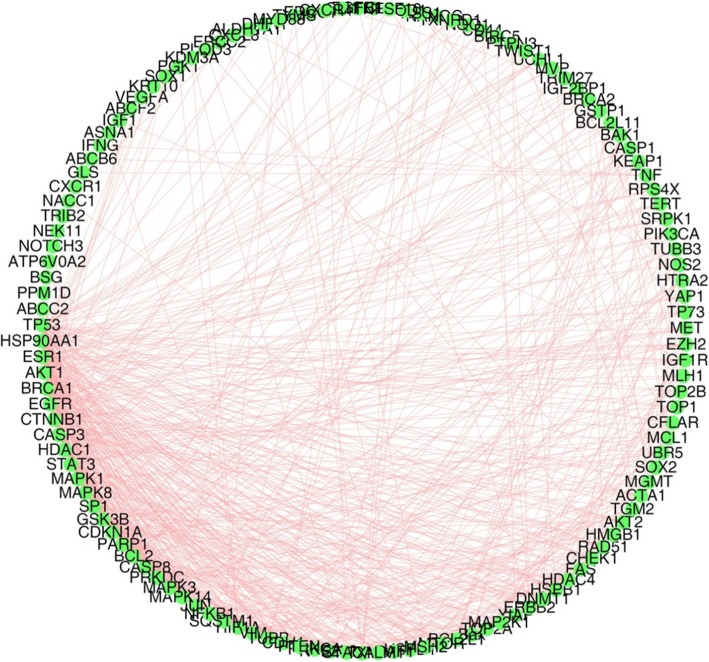

To find out important molecules in platinum resistance mechanism, PPI network was generated with Cytoscape (V3.4.0) software and its plugins. The interactions were illustrated in Fig. 1 and the most popular nodes with their degrees (the number of interactions) were listed in Table 3. TP53 has the highest degree than other proteins, which implies the critical function of it in platinum resistance regulation. In addition, HSP90AA1 (degree = 41), ESR1 (degree = 40), AKT1 (degree = 39), BRCA1 (degree = 35) and other proteins were also predicted as remarkable hubs among the signaling network.

Fig. 1.

The PPI network of platinum-resistance related genes. Self-loops and isolated nodes were deleted. All interactions were based on experiments. Network was generated just among input nodes rather than their neighbours. Molecules with count less than 3 were excluded before PPI analysis

Table 3.

The top nodes (degree> 20) in platinum-resistance related PPI network

| Node | Description | Degree |

|---|---|---|

| TP53 | tumor protein p53 | 56 |

| HSP90AA1 | heat shock protein 90 alpha family class A member 1 | 41 |

| ESR1 | estrogen receptor 1 | 40 |

| AKT1 | AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 | 39 |

| BRCA1 | BRCA1, DNA repair associated | 35 |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor | 34 |

| CTNNB1 | catenin beta 1 | 31 |

| CASP3 | caspase 3 | 30 |

| HDAC1 | histone deacetylase 1 | 28 |

| MAPK1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | 26 |

| STAT3 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 | 26 |

| MAPK8 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 | 25 |

| SP1 | Sp1 transcription factor | 24 |

| GSK3B | glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta | 23 |

| CDKN1A | cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A | 23 |

| PARP1 | poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 | 22 |

| BCL2 | BCL2, apoptosis regulator | 21 |

| CASP8 | caspase 8 | 21 |

All edges are treated as undirected. The degree of each node is calculated with CytoNCA, a plugin for Cytoscape

Cluster analysis for subtypes

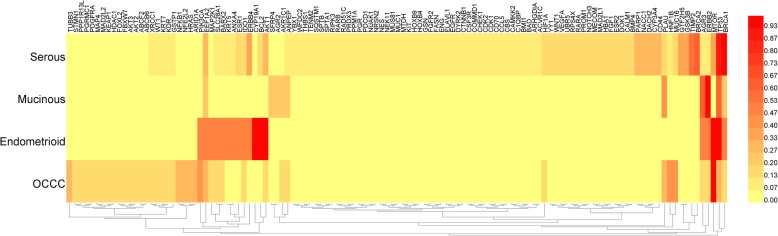

Based on histopathology, ovarian cancer can be mainly classified into four subtypes: serous, mucinous, endometrioid and ovarian cancer of clear cell (OCCC) [21]. Each major histological type has characteristic morphological features and biological behaviors [22], and the incidence of platinum resistance differs from the others. For example, mucinous ovarian cancer has been reported to have a much lower sensitivity and higher resistance rate compared with serous ovarian cancer [23, 24].

To investigate the specific regulatory molecules for each subtype, genes co-appearing with “serous”, “mucinous”, “endometrioid” and “clear cell” (or OCCC) were collected respectively, then cluster analysis were performed. As shown in Fig. 2, each subtype has its distinctive combination for platinum-resistance molecules. Some genes such as TP53 are commonly focused in most subtypes. By comparison, BCL2 and AKT1 were frequently mentioned in endometrioid cancer while ERBB2 and AGR3 were repeatedly mentioned in mucinous cancer. Such genes may be regarded as specific regulators or markers for each subtype.

Fig. 2.

Hierarchical cluster analysis for genes among subtypes of ovarian cancer. Cluster analysis was performed based on maximum-linkage, using similarity metric of maximum distance. Each subtype was normalized respectively before cluster analysis

Discussion

Cisplatin and carboplatin exert antitumor effects by binding to DNA and forming cross-links, thus disrupts DNA structure and finally results in cell apoptosis [25]. Dysregulation in that process may cause platinum resistance. Among all possible regulatory mechanisms, the most important ones include the followings [26]: (1) Suppressed uptake or enhanced efflux can reduce cytosol accumulation of platinum. (2) Drug detoxification mechanism can protect cells from bioactive platinum aquo-complexes. (3) DNA repair can be activated and enhanced to restore DNA damages. (4) Changes in signaling pathways make cells evade fate of apoptosis. These mechanisms and pathways interact with each other, making platinum-resistance regulation very complex. It should be noted that cisplatin and carboplatin share similar molecular structures and are cross-resistant in most cases. In contrast, oxaliplatin are not cross-resistant with them, which may be explained by the lipophilic cyclohexane residue [27]. So oxaliplatin resistance is not discussed in this study.

According to Table 1, most of the top genes can be classified into the four categories mentioned above, and apoptosis is the most significant process in Table 2. The tumor-supressor P53 is a central hub for the activation of intrinsic apoptotic pathway [28]. It can trigger cell death via the expression of apoptotic genes and by inhibiting the expression of anti-apoptotic genes [29]. BCL2 can inhibit cell death induced by cytotoxic factors such as chemotherapeutic drugs and enhance cell resistance [30, 31].

For platinum accumulation, both ABCB1 (MDR1) and ABCC1 (MRP1) belong to ATP binding cassette (ABC) transport protein family, which works as ATP-dependent drug efflux pump and is responsible for decreased platinum accumulation [32, 33]. Among all the identified molecules, ABCG2 (count = 13) and ABCC2 (count = 10) have similar functions though not listed in Table 1. Another example for transporter protein is SLC31A1 [34] (also known as CTR1), a member of copper transporter family, which plays a significant role in platinum uptake [35].

For DNA damage/repair, ERCC1 (ERCC excision repair 1) is a critical member of nucleotide excision repair induced by platinum [36]. Meanwhile, BRCA1 [37] and BRCA2 [38] exert their functions in double-stranded breaks repair of DNA. PARP1 can recognize DNA lesions and modifies various nuclear proteins which are involved in the regulation of DNA repair [39].

Both GSTA1 (count = 12) and GSTP1 (count = 9) belong to the top 10% of all identified genes though not listed in Table 1. The expression products of them are members of cellular detoxification system, which can add glutathione to platinum, block the formation of Pt-DNA and reduce cytotoxicity of platinum [40, 41].

Besides, some popular genes such as AKT1, EGFR, PIK3CA, MAPK1, NFKB1 and MTOR, are difficult to be classified. All of them have multiple functions in physiological and pathological processes and are regarded as key nodes in platinum-resistance signaling network (as shown in Table 3). Their effects toward platinum resistance have been extensively explored, together with their various targets or regulators [42–45].

There are specific genomic alterations and gene-expression patterns for different subtypes of ovarian cancer. According to previous reports, K-RAS mutation is very common in mucinous ovarian carcinomas (75%), but the rate is generally low in clear cell carcinomas [46, 47]. Meanwhile, genes involved in nucleotide excision repair (such as XPB and ERCC1), were found to be preferentially expressed in ovarian clear cell carcinomas [48, 49]. That suggests each subtype may have specific mechanism and molecular character for platinum resistance, but there are few reports for this topic. In our study, genes were enriched according to their co-occurring subtypes and then subjected to cluster analysis. This method helps us understand the differences in regulatory mechanisms among subtypes of ovarian cancer. It is also meaningful for clinical accurate diagnosis and individualized treatment of ovarian cancer.

A potential limitation in this study is the performance of text mining. It can recognize names of genes and proteins, calculate their frequencies and judge the functions of them via co-occurrence analysis, but it cannot really “understand” literatures. However, it is still an effective method to quantitatively assess gene functions and their relationships, especially for comprehensive analysis with large input data.

Authors’ contributions

HL: data collection, manuscript drafting, and funding acquisition. JL and WG: data analysis and manuscript revision. CZ: study conception, data collection and analysis, manuscript drafting and revision. LF: study conception, data analysis, and manuscript revision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7184206).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Haixia Li, Email: lihx_hx@163.com.

Jinghua Li, Email: ljh_fck@sohu.com.

Wanli Gao, Email: gwl_fck@sina.com.

Cheng Zhen, Email: zhencheng302@126.com.

Limin Feng, Email: lucyfeng66@163.com.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannistra SA. Cancer of the ovary. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(24):2519–2529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozols RF, Bookman MA, Connolly DC, Daly MB, Godwin AK, Schilder RJ, et al. Focus on epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossof AH, Talley RW, Stephens R, Thigpen T, Samson MK, Groppe C., Jr el. Phase II evaluation of cis-dichlorodiammineplatinum (II) in advanced malignancies of the genitourinary and gynecologic organs: a southwest oncology group study. Cancer Treat Rep. 1979;63(9–10):1557–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thigpen T, Shingleton H, Homesley H, LaGasse L, Blessing J. cis-Dichlorodiammineplatinum (II) in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies: phase II trials by the gynecologic oncology group. Cancer Treat Rep. 1979;63(9–10):1549–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alberts DS, Green S, Hannigan EV, O'Toole R, Stock-Novack D, Anderson P, et al. Improved therapeutic index of carboplatin plus cyclophosphamide versus cisplatin plus cyclophosphamide: final report by the southwest oncology group of a phase III randomized trial in stages III and IV ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(9):1505. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.9.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhen C, Zhu C, Chen H, Xiong Y, Tan J, Chen D, et al. Systematic analysis of molecular mechanisms for HCC metastasis via text mining approach. Oncotarget. 2017;8(8):13909–13916. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Settles B. ABNER: an open source tool for automatically tagging genes, proteins and other entity names in text. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(14):3191–3192. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Settles B. Proceedings of the international joint workshop on Natural Language Processing in Biomedicine and its Applications (NLPBA) 2004. Biomedical named entity recognition using conditional random fields and rich feature sets; pp. 104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pathan M, Keerthikumar S, Ang CS, Gangoda L, Quek CY, Williamson NA, et al. FunRich: an open access standalone functional enrichment and interaction network analysis tool. Proteomics. 2015;15(15):2597–2601. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin A, Ochagavia ME, Rabasa LC, Miranda J, Fernandez-de-Cossio J, Bringas R. BisoGenet: a new tool for gene network building, visualization and analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang Y, Li M, Wang J, Pan Y, Wu FX. CytoNCA: a cytoscape plugin for centrality analysis and evaluation of protein interaction networks. Biosystems. 2015;127:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Licata L, Briganti L, Peluso D, Perfetto L, Iannuccelli M, Galeota E, et al. MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):857–861. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bader GD, Betel D, Hogue CW. BIND: the biomolecular interaction network database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(1):248–250. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willis RC, Hogue CW. Searching, viewing, and visualizing data in the Biomolecular Interaction Network Database (BIND) Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2006;Chapter 8:Unit 8.9. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0809s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stark C, Breitkreutz BJ, Chatr-Aryamontri A, Boucher L, Oughtred R, Livstone MS, et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):698–704. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xenarios I, Salwinski L, Duan XJ, Higney P, Kim SM, Eisenberg D. DIP, the database of interacting proteins: a research tool for studying cellular networks of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):303–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aranda B, Achuthan P, Alam-Faruque Y, Armean I, Bridge A, Derow C, et al. The IntAct molecular interaction database in 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):525–531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goel R, Muthusamy B, Pandey A, Prasad TS. Human protein reference database and human proteinpedia as discovery resources for molecular biotechnology. Mol Biotechnol. 2011;48(1):87–95. doi: 10.1007/s12033-010-9336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng W, Wang Y, Liu Z, Cheng H, Xue Y. HemI: a toolkit for illustrating heatmaps. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurman RJ, Ellenson LH, Ronnett BM. Blaustein’s pathology of the female genital tract. Pathology. 2003;35:457. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho KR, Shih IM. Ovarian cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:287–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimada M, Kigawa J, Ohishi Y, Yasuda M, Suzuki M, Hiura M, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113(3):331–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pectasides D, Fountzilas G, Aravantinos G, Kalofonos HP, Efstathiou E, Salamalekis E, et al. Advanced stage mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer: the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97(2):436–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabik CA, Dolan ME. Molecular mechanisms of resistance and toxicity associated with platinating agents. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(1):9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang D, Lippard SJ. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(4):307–320. doi: 10.1038/nrd1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eckstein N. Platinum resistance in breast and ovarian cancer cell lines. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:91. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-30-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vousden KH, Lu X. Live or let die: the cell’s response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(8):594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amaral JD, Xavier JM, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. The role of p53 in apoptosis. Discov Med. 2010;9(45):145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddiqui WA, Ahad A, Ahsan H. The mystery of BCL2 family: BCL-2 proteins and apoptosis: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2015;89(3):289–317. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chon HS, Marchion DC, Xiong Y, Chen N, Bicaku E, Stickles XB, et al. The BCL2 antagonist of cell death pathway influences endometrial cancer cell sensitivity to cisplatin. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(1):119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang AK, Zhou ZW, Wei MQ, Liu JP, Zhou SF. Modulators of multidrug resistance associated proteins in the management of anticancer and antimicrobial drug resistance and the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10(17):1732–1756. doi: 10.2174/156802610792928040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu P, Cheng X, Du Y, Yang L, Huang L. Significance of MDR-related proteins in the postoperative individualized chemotherapy of gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11(1):46–50. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.150345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wurz GT, DeGregorio MW. Activating adaptive cellular mechanisms of resistance following sublethal cytotoxic chemotherapy: implications for diagnostic microdosing. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(7):1485–1493. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishida S, Lee J, Thiele DJ, Herskowitz I. Uptake of the anticancer drug cisplatin mediated by the copper transporter Ctr1 in yeast and mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(22):14298–14302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162491399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang S, Ju W, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, Kim SC, et al. Association between excision repair cross-complementation group 1 polymorphism and clinical outcome of platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2006;38(3):320–324. doi: 10.1038/emm.2006.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huen MS, Sy SM, Chen J. BRCA1 and its toolbox for the maintenance of genome integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(2):138–148. doi: 10.1038/nrm2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tagliaferri P, Ventura M, Baudi F, Cucinotto I, Arbitrio M, Di Martino MT, et al. BRCA1/2 genetic background-based therapeutic tailoring of human ovarian cancer: hope or reality? J Ovarian Res. 2009;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouchard VJ, Rouleau M, Poirier GG. PARP-1, a determinant of cell survival in response to DNA damage. Exp Hematol. 2003;31(6):446–454. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(03)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peklak-Scott C, Smitherman PK, Townsend AJ, Morrow CS. Role of glutathione S-transferase P1-1 in the cellular detoxification of cisplatin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(10):3247–3255. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pompella A, De Tata V, Paolicchi A, Zunino F. Expression of gamma-glutamyltransferase in cancer cells and its significance in drug resistance. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71(3):231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cassinelli G, Zuco V, Gatti L, Lanzi C, Zaffaroni N, Colombo D, et al. Targeting the Akt kinase to modulate survival, invasiveness and drug resistance of cancer cells. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20(15):1923–1945. doi: 10.2174/09298673113209990106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burris HA., 3rd Overcoming acquired resistance to anticancer therapy: focus on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71(4):829–842. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meng X, Zhang S. MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2013;51:245–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu K, Bonavida B. The activated NF-kappaB-Snail-RKIP circuitry in cancer regulates both the metastatic cascade and resistance to apoptosis by cytotoxic drugs. Crit Rev Immunol. 2009;29(3):241–254. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v29.i3.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ichikawa Y, Nishida M, Suzuki H, Yoshida S, Tsunoda H, Kubo T, et al. Mutation of K-ras protooncogene is associated with histological subtypes in human mucinous ovarian tumors. Cancer Res. 1994;54(1):33–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayr D, Hirschmann A, Lohrs U, Diebold J. KRAS and BRAF mutations in ovarian tumors: a comprehensive study of invasive carcinomas, borderline tumors and extraovarian implants. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103(3):883–887. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz DR, Kardia SL, Shedden KA, Kuick R, Michailidis G, Taylor JM, et al. Gene expression in ovarian cancer reflects both morphology and biological behavior, distinguishing clear cell from other poor-prognosis ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2002;62(16):4722–4729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hough CD, Sherman-Baust CA, Pizer ES, Montz FJ, Im DD, Rosenshein NB, et al. Large-scale serial analysis of gene expression reveals genes differentially expressed in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60(22):6281–6287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this article.