I became an obstetrician and gynecologist in Marietta, Georgia, decades ago because I believed it would be a happy specialty. Helping to bring 5200 babies into the world certainly affirmed that belief. I also had the good fortune to practice for many years when maternal deaths steadily dropped. That trend began to reverse itself about 25 years ago and the United States, in my view, now faces a crisis. It is one that the US Congress and all participants in our health care system must address with urgency.

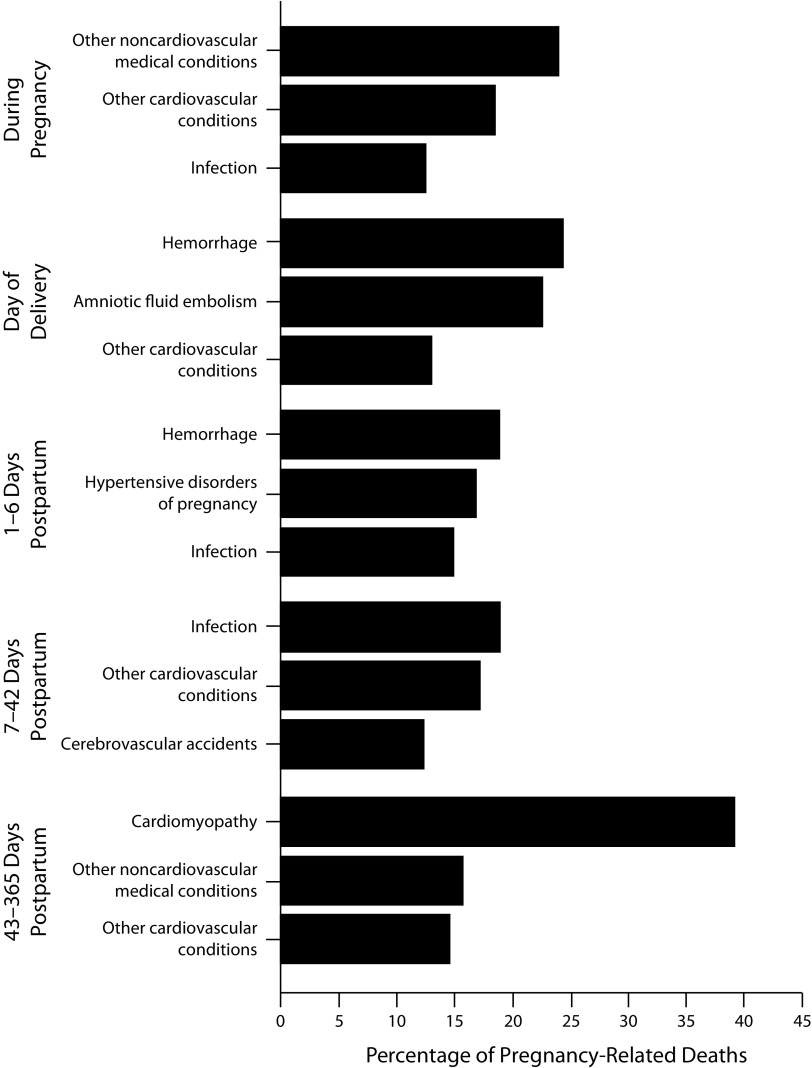

FIGURE 1—

Three Most Frequent Causes of Pregnancy-Related Deaths, by Time Relative to the End of Pregnancy: Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, United States, 2011–2015

Source. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6818e1.htm?s_cid=mm6818e1_w.

In 1986, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began tracking maternal deaths, seven women for every 100 000 live births died during pregnancy, during childbirth, or in the weeks and months following. By 2016, the annual rate had jumped to 17 women for every 100 000 live births.1 In 2014, according to the CDC’s latest statistics, 50 000 women faced dangerous complications from pregnancy and childbirth. Think about all the medical advances that have occurred in recent times, and yet the risks associated with pregnancy have not declined. These figures say to me we are failing women during what should be a most wondrous time of their lives. No developed nation has a more shameful record. It particularly saddens me that among the 50 states, my home state of Georgia sits near the bottom.2

IDENTIFYING THE CAUSES

The CDC recently examined the factors behind this spike in maternal deaths. Heart disease, hemorrhage, and infections appear most frequently on death certificates. The upstream issues include lack of access to care, unstable housing, limited access to transportation, poor understanding of danger signs, and not following medical advice. The CDC also cited health systems ill equipped to deal with maternal emergencies, missed or delayed diagnoses, and poor case coordination.3

Racial and socioeconomic factors are impossible to overlook. African American, Alaska Native, and American Indian women die at a rate almost three times as high as White women. Although women of all backgrounds may be at risk, poverty is linked to the higher rates of maternal deaths.4 Most heartbreaking is the CDC’s conclusion that six of every 10 maternal deaths that occur can be prevented. Bluntly stated, with better and more accessible health care for all, many would be alive today.

There is no single solution to the problem. It requires multiple interventions at all levels to achieve better outcomes. My former constituents in Georgia’s 11th district, as well as colleagues in the state senate and in the US Congress, may find the views of this conservative Republican somewhat surprising. I have turned to our Constitution previously when advocating better health outcomes and the argument is relevant here. The preamble sets as a goal to promote “the general welfare” of the American people. The welfare of pregnant and postpartum women certainly must be a part of that goal.

PURSUING THE SOLUTIONS

As I write this, one of the most promising proposals in the US Congress would extend Medicaid coverage to women one year postpartum. Nearly half of all women who give birth are covered by Medicaid, but many lose that coverage a mere 60 days after delivery. This makes no sense given that an estimated 70% of women develop at least one complication up to a year after giving birth.5

I am fully aware that the notion of expanding Medicaid is a difficult political issue, but the figures do not lie. It is a grave shortcoming to deny women coverage when the need is so obvious. Worrisome is the current administration’s support for budget cutbacks at the CDC and the National Institutes of Health. I would argue that these public health agencies need additional funding to conduct more research and data collection. This would help us better understand the problem and inform the development of a national standard of best practices.

States, professional societies, and health care systems are engaged to varying degrees. These are some of note:

-

•

The Joint Commission, a US-based nonprofit tax-exempt 501 organization that accredits more than 21 000 US health care organizations and programs, recently issued guidelines for the treatment and care of women who are hemorrhaging.6 Collections of best practices for a number of other complications already inform hospital staff.

-

•

California’s maternal death rate has dropped in recent years by 55% because of a cross-sector collaboration focused on developing quality improvement toolkits for recognizing and treating pregnancy complications.7

-

•

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists developed guidance for postpartum or “fourth trimester” treatment (https://bit.ly/362nqLk) and for treating heart disease during pregnancy (https://bit.ly/30GGptT).

-

•

Georgia’s alarming statistics led to a partnership comprising the state Department of Public Health, the CDC, and the Georgia Obstetrical and Gynecological Society to identify the greatest needs to improve maternal health. As a result, money was appropriated to support a range of medical and mental health services principally in rural and underserved communities. About half of the counties in Georgia have no OB/GYN, so several medical schools in the state receive funding for additional residency slots (https://bit.ly/2tuDoQT).

-

•

Among hospital systems attempting to implement innovative programs, I would point out Ochsner Health System in Louisiana. TeleStork, launched in 2016, created an additional layer of fetal and maternal monitoring by establishing an operations center where real-time data are downloaded from labor and delivery rooms and analyzed by highly trained nurses. A year later it rolled out Connected MOM (Maternity Online Monitoring). Low-risk pregnant women are provided with toolkits to use at home so they can digitally send health professionals their blood pressure, weight and urine dip stick information. Both programs can help identify and treat problems early. And, in the case of Connected MOM, there are a reduced number of in-person doctor visits, which provides a convenience particularly for working women and moms with additional children. Given the program’s success, as a next step Ochsner is moving to expand Connected MOM to women with high-risk pregnancies.

SOLVING THE PROBLEM

So, is attention being paid to this crisis? Yes, but I believe more must be done; more coordination, more dedication and more dollars. This call to action comes not only from my background as a doctor and lawmaker. It is personal, too. About a century ago my dad’s mother died in childbirth, casting a shadow over his long life and the lives of his siblings. The devastation caused by the unnecessary death of a mother and partner should not be any family’s experience. A woman should not lose her life by bringing life into the world. With a firm agenda in mind and the funding to back it, we can move toward a day when almost no one in the United States knows that kind of loss and heartbreak.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Ochsner Health System is a client of the District Policy Group.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm. Accessed January 29, 2020.

- 2.World Population Review. Maternal mortality rate by state 2020. Available at: http://worldpopulationreview.com/states/maternal-mortality-rate-by-state. Accessed January 29, 2020.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: pregnancy-related deaths, United States, 2011–2015, and strategies for prevention, 13 states, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 68(18);423–429. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6818e1.htm?s_cid=mm6818e1_w. Accessed January 29, 2020.

- 4.Maternal Health Task Force, Harvard Chan School. Center of Excellence in Maternal and Child Health. Maternal health in the United States. Available at: https://www.mhtf.org/topics/maternal-health-in-the-united-states. Accessed January 29, 2020.

- 5.Kelly R. US House subcommittee takes major congressional action on America’s maternal mortality crisis. Available at: https://robinkelly.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/us-house-subcommittee-takes-major-congressional-action-on-america-s. Accessed January 29, 2020.

- 6.Joint Commission. New standards for perinatal safety. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/New_Perinatal_Standards_Prepub_Report.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2020.

- 7.California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. Available at: https://www.cmqcc.org. Accessed January 29, 2020.