This review summarizes recent findings on the relationship between autophagy and hormone signaling and metabolism in response to abiotic and biotic stresses.

Keywords: Abiotic stress, autophagy, biotic stress, energy metabolism, hormones, nutrient deficiency

Abstract

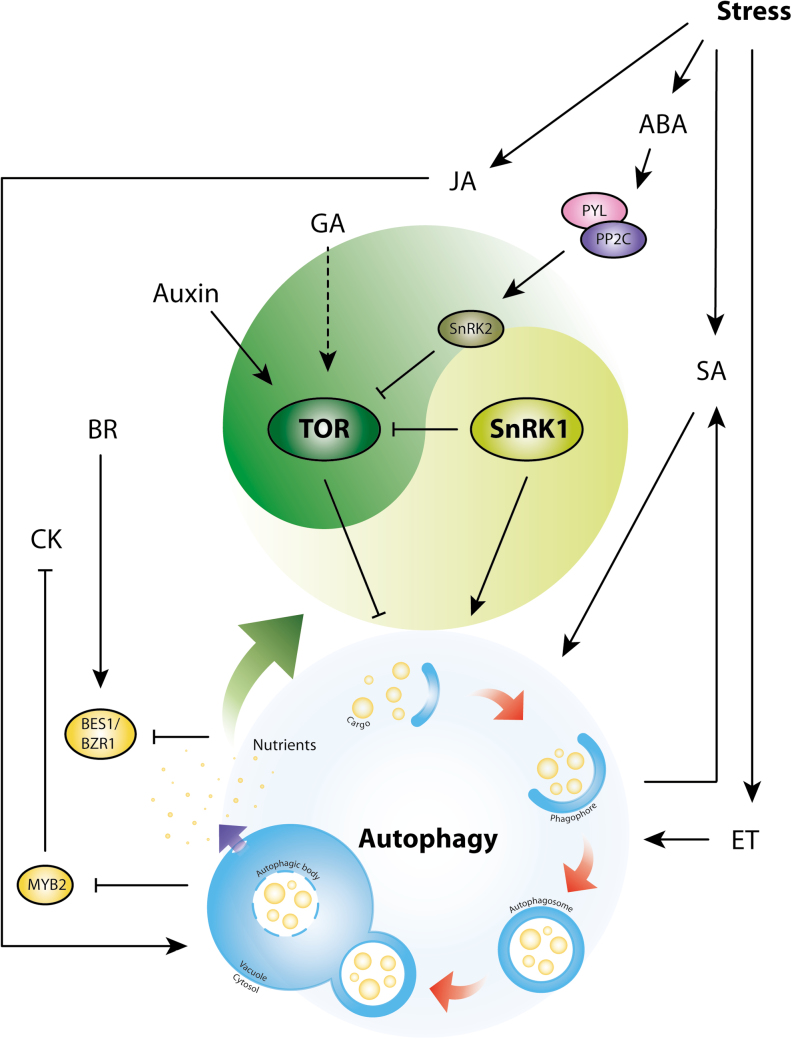

Autophagy is a conserved recycling process in which cellular components are delivered to and degraded in the vacuole/lysosome for reuse. In plants, it assists in responding to dynamic environmental conditions and maintaining metabolite homeostasis under normal or stress conditions. Under stress, autophagy is activated to remove damaged components and to recycle nutrients for survival, and the energy sensor kinases target of rapamycin (TOR) and SNF-related kinase 1 (SnRK1) are key to this activation. Here, we discuss accumulating evidence that hormone signaling plays critical roles in regulating autophagy and plant stress responses, although the molecular mechanisms by which this occurs are often not clear. Several hormones have been shown to regulate TOR activity during stress, in turn controlling autophagy. Hormone signaling can also regulate autophagy gene expression, while, reciprocally, autophagy can regulate hormone synthesis and signaling pathways. We highlight how the interplay between major energy sensors, plant hormones, and autophagy under abiotic and biotic stress conditions can assist in plant stress tolerance.

Introduction

Autophagy is a ‘self-eating’ degradation pathway that recycles cellular components during development or under stress conditions, and is highly conserved in eukaryotes. It functions at a basal level to maintain homeostasis under normal growth conditions, but its activity is enhanced by stress. Initially identified in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (Tsukada and Ohsumi, 1993; Thumm et al., 1994; Harding et al., 1995), autophagy-related (ATG) genes are highly conserved, and a subset of ATG genes encoding the core machinery for autophagosome formation are present in plants (Marshall and Vierstra, 2018). When autophagy is activated, the cargoes (e.g. organelles, proteins, and other macromolecules) to be degraded are engulfed by a double-membrane structure termed a phagophore. The phagophore expands and is sealed, forming a double-membrane vesicle called an autophagosome, which fuses with the vacuole (yeast and plants) or lysosome (animals). The cargoes and the inner membrane of the autophagosome are degraded by the hydrolases inside the vacuole/lysosome and the breakdown products are transported to the cytoplasm and reused by the cell (Fig. 1) (Marshall and Vierstra, 2018; Zhao and Zhang, 2018). The ATG proteins participate in this pathway at different stages. ATG1, ATG13, and ATG101 induce phagophore formation and initiate autophagy (Kamada et al., 2000). The activated ATG1 kinase promotes ATG9-mediated lipid transport (Pankiv et al., 2007; Rao et al., 2016) for membrane expansion. The VPS34 (VACUOLAR PROTEIN SORTING 34) lipid kinase complex generates PI3P (phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate) (Kihara et al., 2001) and recruits PI3P-binding factors such as ATG18 to enable autophagosome expansion (Dove et al., 2004). The ATG5/ATG12/ATG16 E3 ligase complex functions in conjugation of ATG8 with phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), which is important for tethering ATG8 to the phagophore (Ichimura et al., 2000; Romanov et al., 2012). The lipidated ATG8 associates with autophagic receptors with affinity for cargo (Pankiv et al., 2007; Kirkin et al., 2009). Finally, ATG8, along with other factors, helps to close the phagophore (Zhuang et al., 2013) and complete the autophagosome (Marshall and Vierstra, 2018). These ATG proteins have conserved functions in plants.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between hormones and autophagy in Arabidopsis. TOR and SnRK1 are central regulators which act antagonistically in the balance between growth and stress responses. These two protein kinase complexes also integrate various signaling pathways, including hormone signaling. Upon biotic or abiotic stress, TOR is repressed and SnRK1 is activated to induce stress responses, including autophagy. TOR and SnRK1 activity can be regulated by hormones; auxin and GA activate TOR to inhibit autophagy, whereas ABA inhibits TOR activity through PYL–SnRK2 to induce autophagy during stress. It is not clear if autophagy induced by stress via JA, SA, and ET signaling pathways is independent of TOR and SnRK1. Autophagy also affects hormone metabolism and signaling. Induction of autophagy leads to accumulation of SA and CK, and also regulates BR signaling. Solid lines, activation or repression for which there is direct evidence; dashed lines, activation or repression without direct evidence.

Autophagy was initially thought to be a non-selective degradation system, digesting cytoplasmic material in bulk. However, recent studies reveal that most autophagy may be selective to a certain extent (Farre and Subramani, 2016). Selective autophagy is mediated by specific receptors or adaptor proteins containing ATG8-interacting motifs (AIMs) that both bind the cargo and interact with ATG8 for recruitment of cargo into autophagosomes (Birgisdottir et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2016). ATG8 therefore plays a critical role in this process by interacting with the receptors to sequester different cargoes, including organelles or protein aggregates. A recent potato ATG8 interactome revealed that the N-terminal β-strand underpins interaction specificity with the substrates by shaping the hydrophobic pocket that holds the AIM, suggesting that ATG8 isoforms are involved in regulating the selectivity of plant autophagy (Zess et al., 2019). In many cases, information on the receptor and mechanism is limited. Recently, the ubiquitin-binding proteasome subunit RPN10 was identified as a receptor for proteaphagy, simultaneously binding ubiquitylated proteasomes through a ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM) and ATG8 via a new type of UIM-related sequence instead of a canonical AIM (Marshall et al., 2015, 2019). Determining UIM-containing receptors that bind ATG8 via this new mode may lead to rapid progress in identification of additional receptors for selective autophagy substrates.

In plants, several types of selective autophagy have been characterized. For example, protein misfolding is increased by stresses such as heat, and misfolding leads to aggregation. To degrade these protein aggregates, aggrephagy functions via binding of the NEIGHBOR OF BRCA 1 (NBR1) receptor to hyperubiquitylated protein aggregates (Toyooka et al., 2006; Svenning et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2013, 2014). Under endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, reticulophagy drives the degradation of ER fragments, in a pathway dependent on the unfolded protein response factor INOSITOL-REQUIRING ENZYME 1b (IRE1b) (Liu et al., 2012; Howell, 2013). Whole organelles such as mitochondria, peroxisomes, and chloroplasts can also be eliminated by selective autophagy. During stress, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are overproduced and damage organelles and biomolecules. As these three organelles all generate ROS, quality control is critical to protect the cell from ROS damage (Signorelli et al., 2019). Mitochondria are a major source of ROS, which lead to oxidative damage during stress; degradation of mitochondria by autophagy, termed mitophagy, therefore plays a crucial role in protecting cells (Kanki et al., 2009; Yamano et al., 2016). Data from yeast suggest that ATG11 plays a critical role in scaffolding the ATG1/13 complex at the phagophore assembly site and interacts with various receptors for selective autophagy, including mitophagy and also pexophagy, the selective degradation of peroxisomes (Yorimitsu and Klionsky, 2005; Reggiori and Klionsky, 2013). In Arabidopsis, a defect in mitophagy has been observed in atg11 mutants (Li et al., 2014) but, other than this, our understanding of plant mitophagy is very limited. ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation triggers autophagic degradation of peroxisomes during stress, maintaining cell viability (Farmer and Mueller, 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Shibata et al., 2013; Yoshimoto et al., 2014). The peroxisome proteins PEX6 and PEX10 interact with ATG8 via an AIM in planta, suggesting that these proteins may function in pexophagy-mediated peroxisome quality control (Xie et al., 2016). Chlorophagy is a plant-specific type of autophagy and it contributes to the quality control of chloroplasts or specific chloroplast components. Chlorophagy can degrade either entire chloroplasts (Spitzer et al., 2015; Izumi et al., 2017) or chloroplast components (e.g. Rubisco-containing bodies) (Ishida et al., 2008; Izumi et al., 2010; Dong and Chen, 2013) under normal, senescence, or stress conditions. Autophagic degradation of entire chloroplasts also helps to protect cells from photodamage (Izumi et al., 2017), in a process requiring the endosomal protein CHARGED MULTIVESICULAR BODY PROTEIN1 (CHMP1) (Spitzer et al., 2015).

Autophagy plays multiple roles during plant development and stress responses. It helps in removing cellular debris, in nutrient reallocation, and in organelle quality control. In this review, we summarize recent advances in our understanding of how autophagy is regulated under different stress conditions, focusing on the relationship to phytohormones. Since plant stress responses are closely linked to hormone signaling, we will discuss how hormones participate in regulating autophagy for reallocation of nutrients and energy to balance growth and stress tolerance. We will also discuss how selective autophagy contributes to stress responses or hormone signaling.

Autophagic degradation and energy signaling in plants

A large-scale transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of Arabidopsis young rosettes suggested that autophagy is essential for cell homeostasis, and the expression of genes involved in various metabolic pathways is altered in atg5 and atg9 mutants (Masclaux-Daubresse et al., 2014; Avin-Wittenberg et al., 2015). Recent maize multiomics analysis also revealed that autophagy has roles in proteome remodeling and lipid turnover in both nutrient-rich and nutrient-deficient conditions (McLoughlin et al., 2018). Notably, the profile of genes with altered expression in atg5 and atg9 mutants shows similarities with that of mutants affected in cytokinin (CK) signaling, oxidative stress, and plant immunity, suggesting possible co-regulation between autophagy and these pathways. To manage such complex regulation, major regulators that play pivotal roles in metabolism have been identified that integrate these stress and hormone signals (Margalha et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2019). During stress, plant metabolism changes in response to the environment and, in order to reallocate limited nutrients, autophagy is activated above the basal level. Activation of autophagy in response to stresses may rely heavily on the SNF-related kinase 1 (SnRK1) and target of rapamycin (TOR) protein kinase complexes. These known essential energy sensors are evolutionarily conserved among eukaryotes, and emerging data reveal that SnRK1 and TOR kinases coordinate many signaling pathways in response to energy deficiency and various stress conditions, including those that activate autophagy (Fig. 1) (Margalha et al., 2019).

SnRK1 kinase is a heterotrimeric complex that acts as a major regulator of responses to nutrient and energy deficiency (Crozet et al., 2014). The animal and yeast homologs of SnRK1, AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) and Suc non-fermenting 1 (Snf1), activate autophagy under low energy conditions (Carroll and Dunlop, 2017). In Arabidopsis, a double mutant in KIN10 and KIN11, the two SnRK1 catalytic subunits, is lethal, indicating that SnRK1 plays a critical role in plant development (Baena-Gonzalez et al., 2007). Characterization of KIN10-overexpressing lines and knockout mutants indicates that SnRK1 activates autophagy through two mechanisms: (i) direct phosphorylation of ATG1 and (ii) repression of TOR activity (Fig. 1) (Chen et al., 2017; Soto-Burgos and Bassham, 2017). These findings suggest that SnRK1 plays a positive role in autophagy regulation.

TOR is known as a sensor of nutrient concentrations and acts as a negative regulator of autophagy in plants (Deprost et al., 2007; Liu and Bassham, 2010; Wu et al., 2019). The Arabidopsis TOR complex consists of the TOR kinase catalytic subunit, Regulatory-Associated Protein of TOR (RAPTOR), which functions in substrate recruitment (Hara et al., 2002; Anderson and Hanson, 2005; Mahfouz et al., 2006; Tzatsos and Kandror, 2006), and Lethal with Sec Thirteen 8 (LST8), which stabilizes the complex (Moreau et al., 2012). Genes involved in autophagy are differentially expressed in Arabidopsis seedlings treated with or without the TOR inhibitor AZD-8055 (Dong et al., 2015), indicating that the regulation of autophagy depends on (or partially depends on) TOR activity. In yeast, ATG13 is a TOR substrate that controls autophagy in response to nutrient conditions (Kamada et al., 2000) and, in Arabidopsis, the ATG13 phosphoprotein levels decrease during nutrient starvation, possibly due to degradation during autophagy, and increase again upon nutrient re-addition (Suttangkakul et al., 2011). Recent data reveal that Arabidopsis ATG13 interacts with RAPTOR through a plant TOR signaling (TOS) motif to mediate TOR signaling to autophagy components, and mutation of this motif enhances autophagy activity (Son et al., 2018), indicating that ATG13 is a key target of TOR for autophagy regulation in plants. The TOR phosphorylation sites on Arabidopsis ATG13 have now been identified via large-scale phosphoproteomics (Van Leene et al., 2019). These emerging data suggest more potential hypotheses (e.g. signals that activate SnRK1 lead to autophagy activation via ATG1 phosphorylation; signals that inhibit TOR lead to autophagy activation via ATG13 dephosphorylation) in which these energy sensors serve as a hub to coordinate various signaling pathways to regulate autophagy, therefore controlling the trade-off between growth and stress responses.

Autophagy and hormone signaling pathways

Plant hormones play important roles in integrating plant growth, development, and abiotic and biotic stress responses, and interplay between stress signaling and hormone signaling pathways is very common. The stress-related hormones abscisic acid (ABA) (Raghavendra et al., 2010), ethylene (ET) (Dubois et al., 2018), jasmonic acid (JA) (Ahmad et al., 2016), and salicylic acid (SA) (Maruri-Lopez et al., 2019) have been connected tightly to plant stress responses. While ABA is typically involved in signaling in response to abiotic stresses, ET, JA, and SA are more commonly known to mediate defense responses against pathogens and pests. The hormones auxin, CK, gibberellin (GA), and brassinosteroid (BR) are also involved in stress-triggered signaling pathways, suggesting that various signals are integrated to activate appropriate stress responses, in turn leading to broad physiological effects (Colebrook et al., 2014; Bielach et al., 2017; Nolan et al., 2017a; Korver et al., 2018). During stress, protein degradation is critical in removing damaged proteins to reduce potential toxicity, and in cellular remodeling to remove proteins that are no longer needed. This occurs both by autophagy and by the ubiquitin–26S proteasome system (UPS), another evolutionarily conserved protein degradation mechanism. Unlike autophagy, the 26S proteasome itself is an ATP-dependent protease complex and degrades cargo via its own protease activity (Marshall and Vierstra, 2019). Studies have shown that the UPS can be regulated by hormones; for example, ABA inhibits the UPS during germination at high temperature (Chiu et al., 2016). Although both the UPS and autophagy are major protein degradation pathways functioning during stress, compared with the 26S proteasome relatively little is known about the regulation of autophagy by hormones. Here, we discuss recent advances in our understanding of general mechanisms of regulation of plant autophagy by hormone signaling at the transcriptional and post-translational levels.

Transcriptional regulation of autophagy by hormones

The mechanisms by which hormones participate in autophagy regulation are still being elucidated. Evidence from global transcriptome analyses indicates that autophagy genes can be regulated transcriptionally by hormones. In petunia (Petunia hybrida), the levels of PhATG8 transcripts in senescing petals increase during pollination or exogenous ET treatment, while inhibition of ET synthesis decreases this induction (Shibuya et al., 2013), indicating that autophagy is involved in pollination-induced petal senescence via ET. ET-mediated autophagy may be regulated transcriptionally, as several ET-responsive transcription factor-binding elements such as for AP2-EREBP (APETALA2/ethylene-responsive element-binding proteins) are found in the promoters of ATG genes, although direct evidence is yet to be provided (Yue et al., 2018; P. Wang et al., 2019). In tomato, autophagy can be promoted by BR in leaves through increased expression of ATG2 and ATG6 (Fig. 2) (Y. Wang et al., 2019). Auxin also influences a broad range of physiological processes, and several auxin-responsive elements such as IAA or ARF elements are found in ATG promoters. This suggests transcriptional regulation of autophagy mediated by auxin during stress (Yue et al., 2018; P. Wang et al., 2019), although the factors involved are unknown.

Fig. 2.

Model for integration of stress and hormone signaling in regulation of autophagy. Autophagy genes can be transcriptionally activated by ABA, ET, BR, SA, and JA signaling during nutrient starvation, abiotic stress, and biotic stress. During nitrogen (–N) or carbon starvation (–C), BR- and/or ET-mediated signaling activates ATG gene expression to enhance autophagy. PUB9 and ARK2 activate autophagy during phosphate starvation (–P). ABA signaling is involved in autophagy induction during sulfur starvation (–S). ABA regulates ATG8 activity to induce autophagy during salt and drought stress, while hormonal regulation of ATG8CL by Phytophthora infestans during infection is unclear. During drought, ET regulates ERF5 to transcriptionally activate autophagy genes, while it is unclear whether hormone signaling regulates HsfA1a to activate ATG gene expression. WRKY transcription factors are involved in heat and fungal pathogen infection through JA, ABA, or SA signaling, although whether hormones regulate WRKY20 during bacterial pathogen infection is unknown. Solid lines, regulation for which there is some evidence; dashed lines, hypothesized regulation.

Post-translational regulation of autophagy by hormones

Phosphorylation regulates protein activity by chemical modification of proteins with phosphate groups, and it is the most common post-translational modification in eukaryotes. TOR kinase integrates various pathways including hormone and stress signaling through phosphorylation. Since TOR inhibits autophagy (Liu and Bassham, 2010), a recent finding suggests a putative connection between autophagy and ABA signaling via TOR. TOR regulates ABA-mediated stress responses through phosphorylation of the PYL ABA receptors (Wang et al., 2018). The phosphorylation of the PYLs disrupts ABA signaling and leads to inactivation of SnRK2 kinases under non-stress conditions. Under environmental stresses such as drought, ABA- and stress-activated SnRK2 phosphorylates RAPTOR, thus inhibiting TOR activity (Wang et al., 2018), which potentially could lead to activation of autophagy (Fig. 1). In contrast, the hormone auxin activates TOR (Schepetilnikov et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017), leading to inhibition of autophagosome formation (Pu et al., 2017). There are very few studies connecting autophagy and GA. Since GA regulates many developmental processes and biotic or abiotic stress responses antagonistically with ABA, it is logical to consider GA–ABA antagonistic action in potential regulation of autophagy. In rice, Lin et al. (2015) reported that ABA activates SnRK2, which inhibits GA signaling by phosphorylating the activator of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Since autophagy is induced upon stress, when SnRK2s are activated, this finding may indicate a phosphorylation-dependent regulatory mechanism to link autophagy and GA–ABA antagonism via SnRK2 kinases. Overall, these findings suggest that protein phosphorylation is one of the keys in seeking connections between autophagy and hormone signaling pathways. However, whether critical kinases and phosphatases involved in each hormone signaling pathway also regulate autophagy, either directly or indirectly, remains largely unknown.

Autophagy regulates hormone metabolism and signaling

In addition to being regulated by hormones, autophagy can also affect hormone biosynthesis. For example, ET is overproduced in young rosette leaves of Arabidopsis atg mutants (Masclaux-Daubresse et al., 2014). In another example, overexpression of apple MdATG18a enhances drought tolerance by activating autophagy and improves resistance to pathogen infection by enhancing SA levels, indicating that autophagy may play a positive role in regulating SA accumulation (Sun et al., 2018a, b). High concentrations of SA lead to autophagy-mediated senescence and programmed cell death (PCD) in apple. Transcriptomic analyses revealed that SA biosynthesis genes are up-regulated in Arabidopsis atg mutants (Masclaux-Daubresse et al., 2014; Avin-Wittenberg et al., 2015), leading to accumulation of SA, with effects on senescence and pathogen defense (Yoshimoto et al., 2009; Lenz et al., 2011). Arabidopsis autophagy mutants are resistant to the effects of high glucose concentrations on root growth and meristem activity, probably due to increased root auxin levels (Huang et al., 2019). In rice, an atg7 mutant is male sterile, and the endogenous CK concentration is reduced in the anthers of the atg7 mutant (Kurusu et al., 2017).

Several studies also revealed regulation of BR signaling by autophagy. The transcription factor BRI1-EMS SUPPRESSOR 1 (BES1) is a critical regulator of BR responses and is degraded during stress via selective autophagy (Fig. 1) (Zhang et al., 2016; Nolan et al., 2017b). The ubiquitin receptor DOMINANT SUPPRESSOR OF KAR 2 (DSK2) interacts with ATG8 and targets BES1 for selective autophagic degradation; by regulating the BES1 level, DSK2 can switch between growth and stress modes in response to starvation or drought (Nolan et al., 2017b). This process is modulated by both phosphorylation and ubiquitination. DSK2 is regulated by phosphorylation by BIN2 (BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE 2) kinase, thus linking BR signaling with DSK2 activity. In addition, DSK2 binds to ubiquitin, another common post-translational modification of proteins; ubiquitin is a 76 amino acid polypeptide which is covalently attached to the ε-amino group of a lysine residue of a substrate protein (Miricescu et al., 2018). BES1 is ubiquitinated by SINAT2, a RING E3 ubiquitin ligase which interacts with BES1, allowing targeting for selective autophagy by DSK2 during starvation (Nolan et al., 2017b). An in-depth catalog of ubiquitination targets reveals substrates that are involved in auxin, ABA, ET, and BR signaling, as well as in disease resistance (Aguilar-Hernandez et al., 2017). This provides a resource for identifying novel UIM-directed autophagy receptors (Marshall et al., 2019) which recognize ubiquitinated proteins and participate in hormone signaling.

Regulation of autophagy by hormones during stress

During environmental stress, autophagy plays a role in breaking down damaged organelles and proteins, and recycling the breakdown products for use by the cell; this process aids in stress tolerance. Hormone signaling cooperates with autophagy to regulate growth, development, senescence, and stress responses. A recent genome-wide analysis in bread wheat revealed that TaATG promoter regions contain both hormone-related and abiotic stress-related transcription elements, suggesting that hormone and stress signaling may coordinately regulate autophagy gene expression (Yue et al., 2018). Here, we discuss how hormones can regulate autophagy in response to specific stresses.

Nutrient starvation

During nutrient starvation, autophagy acts as a mechanism for nutrient recycling and resource allocation. Several hormones are connected directly or indirectly to autophagy activation when nutrients are limiting. For example, ATG and ET-related genes were induced in soybean under sugar or nitrogen starvation (Okuda et al., 2011). This finding suggested that ET signaling and autophagy may work together in nutrient mobilization and reallocation. In another example, the amount of SA increased in Arabidopsis atg mutants under carbon and nitrogen starvation, indicating that autophagy also regulates hormone biosynthesis in response to nutrient deprivation (Fig. 1) (Masclaux-Daubresse et al., 2014; Avin-Wittenberg et al., 2015). Starch can be broken down into sugars, which participate in many physiological activities as metabolites and as signaling molecules. Autophagy functions in starch remobilization (Wang et al., 2013), and sugar signaling also regulates autophagy during carbon starvation, and this interplay has been discussed recently (Janse van Rensburg et al., 2019). In low sugar supply, ‘sugar starvation autophagy’ is induced to digest starch into sugars. Excessive import of sugars or exogenous sugar supply may also cause stress and induce ‘sugar excess autophagy’. Autophagy caused by either sugar starvation or excess may be regulated by the SnRK1–TOR pathway or ABA signaling via SnRK2–TOR. The sugar starvation/excess responses can also be induced by different environmental stresses (e.g. dark-induced or acute heat-induced sugar starvation responses; drought-, salt-, or cold-induced sugar excess responses) (Krasensky and Jonak, 2012; Tarkowski and Van den Ende, 2015; Barros et al., 2017; Janse van Rensburg et al., 2019). This raises the possibility that the interplay between sugar signaling and autophagy may play key roles in response to specific environmental changes.

Autophagy also plays an important role in nitrogen recycling, and transcription factors that regulate the expression of autophagy genes upon nitrogen deprivation have been identified. During nitrogen starvation, the tomato BR-regulated transcription factor BRASSINAZOLE RESISTANT1 (BZR1) increases ATG2/6 expression, enhancing degradation of denatured and unfolded proteins by autophagy. Moreover, exogenous application of BR inhibited accumulation of insoluble proteins by increasing autophagosome formation, leading to enhanced tolerance of nitrogen starvation (Fig. 2) (Y. Wang et al., 2019). These findings provide direct evidence that BR signaling transcriptionally controls autophagy. In addition, the expression of MYB DOMAIN PROTEIN2 (MYB2) transcription factor, which regulates senescence by inhibiting CK-mediated branching in Arabidopsis (Guo and Gan, 2011), increases significantly in both atg5 and atg9 mutants grown under low nitrate for 30 d after sowing (Fig. 1) (Masclaux-Daubresse et al., 2014). Although not directly related to nitrogen starvation, this implies a link between autophagy and CK signal perception in low nitrate conditions.

There are relatively few studies on hormone regulation of autophagy during phosphate starvation, sulfur starvation, or other nutrient-deficient conditions. Lateral root (LR) development during phosphate starvation is mediated by S-domain Arabidopsis Receptor Kinase 2 (ARK2) and plant U-box/armadillo repeat protein 9 (PUB9) E3 ligase (Deb et al., 2014). Inhibition of autophagy in the root leads to reduced LR development and auxin accumulation under phosphate starvation, indicating that autophagy is involved in LR regulation (Deb et al., 2014). Sankaranarayanan and Samuel (2015) proposed a model in which auxin-dependent LR development in Arabidopsis is regulated by selective autophagy in response to phosphate starvation (Fig. 2). Although direct evidence for the ARK2/PUB9 model is still needed, this provides a hypothesis explaining how auxin controls specific organ growth via autophagy-mediated degradation of auxin-related repressors under nutrient deprivation. Upon sulfur starvation, the sulfate supply for cysteine synthesis is limited, which induces autophagy by decreasing TOR activity (Dong et al., 2017), thus remobilizing internal nutrient sources. ABA and cysteine content are significantly reduced in sultr3, a quintuple mutant of five members of sulfate transporter (SULTR) subfamily 3, and sultr3 seed germination is hypersensitive to exogenous ABA and salt stress (Chen et al., 2019). These findings indicate a positive correlation between sulfate, cysteine, and ABA biosynthesis, implying that ABA may be involved in cellular sulfur homeostasis via autophagy under sulfur starvation or other stresses (Fig. 2). The mechanisms by which hormones participate in TOR signaling to regulate autophagy, and how the fluxes of carbon, nitrogen, phosphate, and sulfur are coordinated under various nutrient supply conditions, are still to be discovered.

Abiotic stresses

Emerging evidence indicates that autophagy is involved in the response to various abiotic environmental stresses, such as high temperature, drought, and salt stress (Avin-Wittenberg, 2019; Signorelli et al., 2019). Some of these studies also link the autophagy-mediated stress response to hormone signaling pathways. However, the molecular mechanisms by which these signaling pathways are integrated remain largely unknown. Plant tryptophan-rich sensory protein (TSPO)-related proteins are multistress regulators whose expression is induced by ABA treatment, osmotic stress, and salt stress. AtTSPO is expressed in dry seeds and can be induced in vegetative tissues by stress or ABA treatment (Guillaumot et al., 2009). AtTSPO binds directly to ATG8 via its AIM to regulate cellular heme levels (Vanhee et al., 2011). TSPO also binds PIP2;7, a plasma membrane aquaporin, to reduce intercellular water transport upon water deficit via autophagic degradation of both proteins (Hachez et al., 2014). ABA treatment induces TSPO and triggers the degradation of PIP2;7, suggesting that ABA may play a key role in selective autophagy in response to water-related stress (Fig. 2) (Hachez et al., 2014). Two additional plant-specific proteins, ATI1 and ATI2, bind to ATG8 proteins (Avin-Wittenberg et al., 2012; Honig et al., 2012) and are incorporated into punctate structures upon salt stress. These structures are transported to the vacuole in a process requiring autophagy, and ATI1/2-deficient plants are hypersensitive to salt stress (Fig. 2) (Michaeli et al., 2014), indicating a role for ATI1/2 in salt tolerance. ATI1/2 play a role in seed germination in response to exogenous ABA (Honig et al., 2012), indicating a link between autophagy, salt tolerance, and ABA. These plant-specific ATG8-interacting proteins reveal that selective turnover of specific proteins, for example possible germination-inhibiting ABA-associated proteins, may be critical to stimulate or inhibit seed germination and salt tolerance, perhaps through coordination with ABA responses.

During abiotic stress, a complex network of stress-responsive transcription factors regulates the expression of stress-responsive genes, including genes related to autophagy. Ethylene response factor 5 (ERF5) is a critical transcription factor which is induced by 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC; the precursor of ET) and is involved in abiotic stress tolerance (Zhu et al., 2018). ERF5 directly binds to the promoters of ATG8d and ATG18h to promote autophagy by activating gene expression in tomato (Fig. 2) (Zhu et al., 2018). Activation of autophagy genes thus leads to ET-mediated drought tolerance. Heat stress transcription factors such as HsfA1a also function in drought tolerance (Guo et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2019). In tomato, HsfA1a activates ATG genes and induces autophagy to enhance drought tolerance, revealing a direct link between autophagy and drought tolerance (Wang et al., 2015). Unexpectedly, ABA-dependent pathways do not play major roles in HsfA1a-mediated drought tolerance (Wang et al., 2015), and whether other hormones are involved in regulating autophagy in drought tolerance still needs to be elucidated (Fig. 2). The WRKY family includes a large number of transcription factors that modulate many physiological processes and responses to various stresses. WRKY33 induces the expression of ATG genes during stress and regulates heat-induced autophagy in plants (Zhou et al., 2014). A number of studies show that WRKYs can be induced by ABA, SA, and JA, and are involved in abiotic stress tolerance and hormone responses (Fig. 2) (Bai et al., 2018). However, how hormones participate in the interaction between autophagy and WRKY-mediated abiotic stress responses remains unclear. These studies show that autophagy can be positively regulated by hormone-related transcription factors via increased expression of ATG genes.

Biotic stresses

Accumulating evidence links autophagy to plant–pathogen interactions, plant immunity against pathogens, and cell death regulation (Leary et al., 2018). Autophagy contributes to plant immunity in many ways, for example by regulating defense hormone levels and PCD, although the molecular mechanisms are poorly understood (Liu et al., 2005; Yoshimoto et al., 2009; Coll et al., 2014). In some cases, the regulatory mechanism seems similar to that of responses to abiotic stress. For example, the WRKY family participates in responses to both abiotic and biotic stresses. WRKY33 interacts with ATG18a to regulate autophagy, which also cooperates with the JA-mediated signaling pathway in plant resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens (Fig. 2) (Lai et al., 2011). In addition, WRKY20 activates transcription of ATG8a and enhances bacterial blight resistance in cassava (Yan et al., 2017), although it is not clear if hormones are involved (Fig. 2). A study in banana implied that autophagy may be controlled by hormones and contributes to immune responses to pathogen infection. Inhibition of autophagy by application of the PI3K inhibitor 3-methyladenine decreased resistance of banana to Fusarium wilt, and this effect was rescued by exogenous ET, SA, and JA (Wei et al., 2017), indicating a relationship between hormone signaling and autophagy in pathogen defense. Selective autophagy also helps in defense against plant viruses (Hafrén et al., 2017, 2018; Haxim et al., 2017); these studies suggest that autophagy has a positive role in plant defense.

Recent discoveries reveal that pathogen-produced proteins can control the activation of autophagy or interfere with plant autophagy-related defenses (Dagdas et al., 2016, 2018; Ustun et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018). The selective autophagy cargo receptor NBR aids defense against the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans (Dagdas et al., 2016). PexRD54, an effector from P. infestans, can bind to the autophagy-related protein ATG8CL from its potato host and trigger the formation of autophagosomes (Fig. 2) (Dagdas et al., 2016). By depleting Joka2 from ATG8CL complexes, PexRD54 makes the plant more susceptible to pathogen infection (Dagdas et al., 2016, 2018). During Barley stripe mosaic virus infection, the viral γb protein interacts with ATG7, preventing its interaction with ATG8 and thereby blocking defense pathways (Yang et al., 2018). An interesting example of the fight between plant and pathogen control of autophagy is described in Ustun et al. (2018), in which a bacterial effector activates autophagy, leading to degradation of proteasomes, thus increasing infection, whereas selective autophagy activated by the host plant and involving the receptor NBR1 acts in opposition to infection. Selective autophagy therefore determines the outcome of the infection by acting in both pro- and anti-bacterial pathways. Although signaling by hormones such as SA is connected to pathogen defense, whether it is involved in autophagy regulation in this case remains to be elucidated.

In host organisms other than plants, some viruses and bacteria hijack the host autophagy machinery and enhance autophagy to acquire host nutrients for their own use (Heaton and Randall, 2010; Niu et al., 2012). Although this is still only a hypothesis in plant host–pathogen autophagy interactions, and it is not clear whether hormone regulation is also involved, studying how autophagy is regulated by the host and pathogens during the evolutionary plant–pathogen arms race will expand our understanding of the roles that autophagy plays in various conditions.

Perspectives and future directions

Plants use various strategies to respond to changing environmental conditions. Autophagy is a conserved mechanism in eukaryotes and is involved in numerous biological processes. Here, we discussed signaling pathways that respond to multiple stressors to regulate autophagy. However, many questions remain about the mechanisms of autophagy regulation by various signaling pathways. What is the basis of the variation in stress tolerance between plants? Control of stress responses by hormone signaling has been demonstrated in many studies, but autophagy is rarely included for discussion. Is the activation of autophagy dependent on either activation of SnRK1 kinase or inhibition of TOR kinase as a general regulatory mechanism? If so, is autophagy induced by hormones via activation of SnRK1 or inhibition of TOR? The integrated regulatory mechanisms connecting autophagy, plant hormones, and stresses in plants remain poorly understood, but central regulators of metabolism such as SnRK1 and TOR could be pivotal in linking these pathways. Future directions in plant autophagy research such as identification of novel cargo receptors and upstream/downstream transcription factors will contribute to our understanding of how this multifunctional mechanism acts in the balance between plant growth and stress responses.

Plants are exposed to multiple stressors in the field, and their growth and development are adjusted during stress conditions. Although a number of stress-triggered signaling pathways have been revealed in recent decades, many of them remain unclear. Since the signaling networks are rarely simple, future research must address the role of autophagy in stress responses by global analyses. For example, analysis of the overlap between the transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome in different atg mutants, stress-treated plants, and hormone-treated plants and/or biosynthesis-/signaling-deficient mutants may aid in identifying new stress signaling components. Together with reductive approaches, these analyses can contribute to determining the roles that autophagy plays in different conditions.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant no.1R01GM120316-01A1 from the United States National Institutes of Health to DCB.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ABA

abscisic acid

- AIM

ATG8-interacting motif

- BR

brassinosteroid

- CK

cytokinin

- ET

ethylene

- GA

gibberellin

- JA

jasmonic acid

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SA

salicylic acid

- SnRK

SNF-related kinase

- TOR

target of rapamycin

- UIM

ubiquitin-interacting motif

- UPS

ubiquitin–26S proteasome system.

References

- Aguilar-Hernández V, Kim DY, Stankey RJ, Scalf M, Smith LM, Vierstra RD. 2017. Mass spectrometric analyses reveal a central role for ubiquitylation in remodeling the arabidopsis proteome during photomorphogenesis. Molecular Plant 10, 846–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad P, Rasool S, Gul A, Sheikh SA, Akram NA, Ashraf M, Kazi AM, Gucel S. 2016. Jasmonates: multifunctional roles in stress tolerance. Frontiers in Plant Science 7, 813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GH, Hanson MR. 2005. The Arabidopsis Mei2 homologue AML1 binds AtRaptor1B, the plant homologue of a major regulator of eukaryotic cell growth. BMC Plant Biology 5, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avin-Wittenberg T. 2019. Autophagy and its role in plant abiotic stress management. Plant, Cell & Environment 42, 1045–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avin-Wittenberg T, Bajdzienko K, Wittenberg G, Alseekh S, Tohge T, Bock R, Giavalisco P, Fernie AR. 2015. Global analysis of the role of autophagy in cellular metabolism and energy homeostasis in Arabidopsis seedlings under carbon starvation. The Plant Cell 27, 306–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avin-Wittenberg T, Michaeli S, Honig A, Galili G. 2012. ATI1, a newly identified atg8-interacting protein, binds two different Atg8 homologs. Plant Signaling & Behavior 7, 685–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-González E, Rolland F, Thevelein JM, Sheen J. 2007. A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature 448, 938–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Sunarti S, Kissoudis C, Visser RGF, van der Linden CG. 2018. The role of tomato WRKY genes in plant responses to combined abiotic and biotic stresses. Frontiers in Plant Science 9, 801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros JAS, Cavalcanti JHF, Medeiros DB, Nunes-Nesi A, Avin-Wittenberg T, Fernie AR, Araújo WL. 2017. Autophagy deficiency compromises alternative pathways of respiration following energy deprivation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiology 175, 62–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielach A, Hrtyan M, Tognetti VB. 2017. Plants under stress: involvement of auxin and cytokinin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, E1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgisdottir ÅB, Lamark T, Johansen T. 2013. The LIR motif—crucial for selective autophagy. Journal of Cell Science 126, 3237–3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll B, Dunlop EA. 2017. The lysosome: a crucial hub for AMPK and mTORC1 signalling. Biochemical Journal 474, 1453–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Su ZZ, Huang L, Xia FN, Qi H, Xie LJ, Xiao S, Chen QF. 2017. The AMP-activated protein kinase KIN10 is involved in the regulation of autophagy in arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science 8, 1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Zhao PX, Miao ZQ, et al. 2019. SULTR3s function in chloroplast sulfate uptake and affect ABA biosynthesis and the stress response. Plant Physiology 180, 593–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu RS, Pan S, Zhao R, Gazzarrini S. 2016. ABA-dependent inhibition of the ubiquitin proteasome system during germination at high temperature in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 88, 749–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colebrook EH, Thomas SG, Phillips AL, Hedden P. 2014. The role of gibberellin signalling in plant responses to abiotic stress. Journal of Experimental Biology 217, 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll NS, Smidler A, Puigvert M, Popa C, Valls M, Dangl JL. 2014. The plant metacaspase AtMC1 in pathogen-triggered programmed cell death and aging: functional linkage with autophagy. Cell Death and Differentiation 21, 1399–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozet P, Margalha L, Confraria A, Rodrigues A, Martinho C, Adamo M, Elias CA, Baena-González E. 2014. Mechanisms of regulation of SNF1/AMPK/SnRK1 protein kinases. Frontiers in Plant Science 5, 190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagdas YF, Belhaj K, Maqbool A, et al. 2016. An effector of the Irish potato famine pathogen antagonizes a host autophagy cargo receptor. eLife 5, e10856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagdas YF, Pandey P, Tumtas Y, et al. 2018. Host autophagy machinery is diverted to the pathogen interface to mediate focal defense responses against the Irish potato famine pathogen. eLife 7, e37476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb S, Sankaranarayanan S, Wewala G, Widdup E, Samuel MA. 2014. The S-Domain Receptor Kinase Arabidopsis Receptor Kinase2 and the U Box/Armadillo Repeat-Containing E3 Ubiquitin Ligase9 module mediates lateral root development under phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 165, 1647–1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprost D, Yao L, Sormani R, Moreau M, Leterreux G, Nicolaï M, Bedu M, Robaglia C, Meyer C. 2007. The Arabidopsis TOR kinase links plant growth, yield, stress resistance and mRNA translation. EMBO Reports 8, 864–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Chen W. 2013. The role of autophagy in chloroplast degradation and chlorophagy in immune defenses during Pst DC3000 (AvrRps4) infection. PLoS One 8, e73091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong P, Xiong F, Que Y, Wang K, Yu L, Li Z, Ren M. 2015. Expression profiling and functional analysis reveals that TOR is a key player in regulating photosynthesis and phytohormone signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science 6, 677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Silbermann M, Speiser A, et al. 2017. Sulfur availability regulates plant growth via glucose–TOR signaling. Nature Communications 8, 1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Dove SK, Piper RC, McEwen RK, et al. 2004. Svp1p defines a family of phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate effectors. The EMBO Journal 23, 1922–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Van den Broeck L, Inzé D. 2018. The pivotal role of ethylene in plant growth. Trends in Plant Science 23, 311–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EE, Mueller MJ. 2013. ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation and RES-activated signaling. Annual Review of Plant Biology 64, 429–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré JC, Subramani S. 2016. Mechanistic insights into selective autophagy pathways: lessons from yeast. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 17, 537–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumot D, Guillon S, Morsomme P, Batoko H. 2009. ABA, porphyrins and plant TSPO-related protein. Plant Signaling & Behavior 4, 1087–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Liu JH, Ma X, Luo DX, Gong ZH, Lu MH. 2016. The plant heat stress transcription factors (HSFs): structure, regulation, and function in response to abiotic stresses. Frontiers in Plant Science 7, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Gan S. 2011. AtMYB2 regulates whole plant senescence by inhibiting cytokinin-mediated branching at late stages of development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 156, 1612–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachez C, Veljanovski V, Reinhardt H, Guillaumot D, Vanhee C, Chaumont F, Batoko H. 2014. The Arabidopsis abiotic stress-induced TSPO-related protein reduces cell-surface expression of the aquaporin PIP2;7 through protein–protein interactions and autophagic degradation. The Plant Cell 26, 4974–4990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafrén A, Macia JL, Love AJ, Milner JJ, Drucker M, Hofius D. 2017. Selective autophagy limits cauliflower mosaic virus infection by NBR1-mediated targeting of viral capsid protein and particles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 114, E2026–E2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafrén A, Üstün S, Hochmuth A, Svenning S, Johansen T, Hofius D. 2018. Turnip mosaic virus counteracts selective autophagy of the viral silencing suppressor HCpro. Plant Physiology 176, 649–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, Yoshino K, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Avruch J, Yonezawa K. 2002. Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell 110, 177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding TM, Morano KA, Scott SV, Klionsky DJ. 1995. Isolation and characterization of yeast mutants in the cytoplasm to vacuole protein targeting pathway. Journal of Cell Biology 131, 591–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxim Y, Ismayil A, Jia Q, et al. 2017. Autophagy functions as an antiviral mechanism against geminiviruses in plants. eLife 6, e23897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton NS, Randall G. 2010. Dengue virus-induced autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Cell Host & Microbe 8, 422–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honig A, Avin-Wittenberg T, Ufaz S, Galili G. 2012. A new type of compartment, defined by plant-specific Atg8-interacting proteins, is induced upon exposure of Arabidopsis plants to carbon starvation. The Plant Cell 24, 288–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SH. 2013. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 64, 477–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Yu LJ, Zhang X, Fan B, Wang FZ, Dai YS, Qi H, Zhou Y, Xie LJ, Xiao S. 2019. Autophagy regulates glucose-mediated root meristem activity by modulating ROS production in Arabidopsis. Autophagy 15, 407–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura Y, Kirisako T, Takao T, et al. 2000. A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation. Nature 408, 488–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H, Yoshimoto K, Izumi M, Reisen D, Yano Y, Makino A, Ohsumi Y, Hanson MR, Mae T. 2008. Mobilization of rubisco and stroma-localized fluorescent proteins of chloroplasts to the vacuole by an ATG gene-dependent autophagic process. Plant Physiology 148, 142–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi M, Ishida H, Nakamura S, Hidema J. 2017. Entire photodamaged chloroplasts are transported to the central vacuole by autophagy. The Plant Cell 29, 377–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi M, Wada S, Makino A, Ishida H. 2010. The autophagic degradation of chloroplasts via Rubisco-containing bodies is specifically linked to leaf carbon status but not nitrogen status in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 154, 1196–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janse van Rensburg HC, Van den Ende W, Signorelli S. 2019. Autophagy in plants: both a puppet and a puppet master of sugars. Frontiers in Plant Science 10, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada Y, Funakoshi T, Shintani T, Nagano K, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. 2000. Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. Journal of Cell Biology 150, 1507–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki T, Wang K, Cao Y, Baba M, Klionsky DJ. 2009. Atg32 is a mitochondrial protein that confers selectivity during mitophagy. Developmental Cell 17, 98–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A, Noda T, Ishihara N, Ohsumi Y. 2001. Two distinct Vps34 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes function in autophagy and carboxypeptidase Y sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of Cell Biology 152, 519–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lee H, Lee HN, Kim SH, Shin KD, Chung T. 2013. Autophagy-related proteins are required for degradation of peroxisomes in Arabidopsis hypocotyls during seedling growth. The Plant Cell 25, 4956–4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkin V, Lamark T, Sou YS, et al. 2009. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Molecular Cell 33, 505–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korver RA, Koevoets IT, Testerink C. 2018. Out of shape during stress: a key role for auxin. Trends in Plant Science 23, 783–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasensky J, Jonak C. 2012. Drought, salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 1593–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurusu T, Koyano T, Kitahata N, Kojima M, Hanamata S, Sakakibara H, Kuchitsu K. 2017. Autophagy-mediated regulation of phytohormone metabolism during rice anther development. Plant Signaling & Behavior 12, e1365211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Z, Wang F, Zheng Z, Fan B, Chen Z. 2011. A critical role of autophagy in plant resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. The Plant Journal 66, 953–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary AY, Sanguankiattichai N, Duggan C, Tumtas Y, Pandey P, Segretin ME, Salguero Linares J, Savage ZD, Yow RJ, Bozkurt TO. 2018. Modulation of plant autophagy during pathogen attack. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 1325–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz HD, Haller E, Melzer E, et al. 2011. Autophagy differentially controls plant basal immunity to biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. The Plant Journal 66, 818–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Chung T, Vierstra RD. 2014. AUTOPHAGY-RELATED11 plays a critical role in general autophagy- and senescence-induced mitophagy in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 26, 788–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Cai W, Liu Y, Li H, Fu L, Liu Z, Xu L, Liu H, Xu T, Xiong Y. 2017. Differential TOR activation and cell proliferation in Arabidopsis root and shoot apexes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 114, 2765–2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Wu F, Sheng P, et al. 2015. The SnRK2–APC/C(TE) regulatory module mediates the antagonistic action of gibberellic acid and abscisic acid pathways. Nature Communications 6, 7981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Bassham DC. 2010. TOR is a negative regulator of autophagy in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One 5, e11883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Burgos JS, Deng Y, Srivastava R, Howell SH, Bassham DC. 2012. Degradation of the endoplasmic reticulum by autophagy during endoplasmic reticulum stress in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 24, 4635–4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Schiff M, Czymmek K, Tallóczy Z, Levine B, Dinesh-Kumar SP. 2005. Autophagy regulates programmed cell death during the plant innate immune response. Cell 121, 567–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahfouz MM, Kim S, Delauney AJ, Verma DP. 2006. Arabidopsis TARGET OF RAPAMYCIN interacts with RAPTOR, which regulates the activity of S6 kinase in response to osmotic stress signals. The Plant Cell 18, 477–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margalha L, Confraria A, Baena-González E. 2019. SnRK1 and TOR: modulating growth–defense trade-offs in plant stress responses. Journal of Experimental Botany 70, 2261–2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RS, Hua Z, Mali S, McLoughlin F, Vierstra RD. 2019. ATG8-binding UIM proteins define a new class of autophagy adaptors and receptors. Cell 177, 766–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RS, Li F, Gemperline DC, Book AJ, Vierstra RD. 2015. Autophagic degradation of the 26S proteasome is mediated by the dual ATG8/ubiquitin receptor RPN10 in Arabidopsis. Molecular Cell 58, 1053–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RS, Vierstra RD. 2018. Autophagy: the master of bulk and selective recycling. Annual Review of Plant Biology 69, 173–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RS, Vierstra RD. 2019. Dynamic regulation of the 26S proteasome: from synthesis to degradation. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 6, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruri-López I, Aviles-Baltazar NY, Buchala A, Serrano M. 2019. Intra and extracellular journey of the phytohormone salicylic acid. Frontiers in Plant Science 10, 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masclaux-Daubresse C, Clément G, Anne P, Routaboul JM, Guiboileau A, Soulay F, Shirasu K, Yoshimoto K. 2014. Stitching together the multiple dimensions of autophagy using metabolomics and transcriptomics reveals impacts on metabolism, development, and plant responses to the environment in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 26, 1857–1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin F, Augustine RC, Marshall RS, Li F, Kirkpatrick LD, Otegui MS, Vierstra RD. 2018. Maize multi-omics reveal roles for autophagic recycling in proteome remodelling and lipid turnover. Nature Plants 4, 1056–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaeli S, Honig A, Levanony H, Peled-Zehavi H, Galili G. 2014. Arabidopsis ATG8-INTERACTING PROTEIN1 is involved in autophagy-dependent vesicular trafficking of plastid proteins to the vacuole. The Plant Cell 26, 4084–4101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miricescu A, Goslin K, Graciet E. 2018. Ubiquitylation in plants: signaling hub for the integration of environmental signals. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 4511–4527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau M, Azzopardi M, Clément G, et al. 2012. Mutations in the Arabidopsis homolog of LST8/GβL, a partner of the target of rapamycin kinase, impair plant growth, flowering, and metabolic adaptation to long days. The Plant Cell 24, 463–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H, Xiong Q, Yamamoto A, Hayashi-Nishino M, Rikihisa Y. 2012. Autophagosomes induced by a bacterial Beclin 1 binding protein facilitate obligatory intracellular infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 109, 20800–20807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan T, Chen J, Yin Y. 2017a Cross-talk of brassinosteroid signaling in controlling growth and stress responses. Biochemical Journal 474, 2641–2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan TM, Brennan B, Yang M, Chen J, Zhang M, Li Z, Wang X, Bassham DC, Walley J, Yin Y. 2017b Selective autophagy of BES1 mediated by DSK2 balances plant growth and survival. Developmental Cell 41, 33–46.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda M, Nang MP, Oshima K, Ishibashi Y, Zheng SH, Yuasa T, Iwaya-Inoue M. 2011. The ethylene signal mediates induction of GmATG8i in soybean plants under starvation stress. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 75, 1408–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, Øvervatn A, Bjørkøy G, Johansen T. 2007. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. Journal of Biological Chemistry 282, 24131–24145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu Y, Luo X, Bassham DC. 2017. TOR-dependent and -independent pathways regulate autophagy in Arabidopsis thaliana. Frontiers in Plant Science 8, 1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra AS, Gonugunta VK, Christmann A, Grill E. 2010. ABA perception and signalling. Trends in Plant Science 15, 395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao Y, Perna MG, Hofmann B, Beier V, Wollert T. 2016. The Atg1-kinase complex tethers Atg9-vesicles to initiate autophagy. Nature Communications 7, 10338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F, Klionsky DJ. 2013. Autophagic processes in yeast: mechanism, machinery and regulation. Genetics 194, 341–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov J, Walczak M, Ibiricu I, Schüchner S, Ogris E, Kraft C, Martens S. 2012. Mechanism and functions of membrane binding by the Atg5–Atg12/Atg16 complex during autophagosome formation. The EMBO Journal 31, 4304–4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan S, Samuel MA. 2015. A proposed role for selective autophagy in regulating auxin-dependent lateral root development under phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. Plant Signaling & Behavior 10, e989749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepetilnikov M, Dimitrova M, Mancera-Martínez E, Geldreich A, Keller M, Ryabova LA. 2013. TOR and S6K1 promote translation reinitiation of uORF-containing mRNAs via phosphorylation of eIF3h. The EMBO Journal 32, 1087–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Oikawa K, Yoshimoto K, Kondo M, Mano S, Yamada K, Hayashi M, Sakamoto W, Ohsumi Y, Nishimura M. 2013. Highly oxidized peroxisomes are selectively degraded via autophagy in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 25, 4967–4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya K, Niki T, Ichimura K. 2013. Pollination induces autophagy in petunia petals via ethylene. Journal of Experimental Botany 64, 1111–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signorelli S, Tarkowski ŁP, Van den Ende W, Bassham DC. 2019. Linking autophagy to abiotic and biotic stress responses. Trends in Plant Science 24, 413–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son O, Kim S, Kim D, Hur YS, Kim J, Cheon CI. 2018. Involvement of TOR signaling motif in the regulation of plant autophagy. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 501, 643–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Burgos J, Bassham DC. 2017. SnRK1 activates autophagy via the TOR signaling pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One 12, e0182591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer C, Li F, Buono R, Roschzttardtz H, Chung T, Zhang M, Osteryoung KW, Vierstra RD, Otegui MS. 2015. The endosomal protein CHARGED MULTIVESICULAR BODY PROTEIN1 regulates the autophagic turnover of plastids in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 27, 391–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Huo L, Jia X, Che R, Gong X, Wang P, Ma F. 2018a Overexpression of MdATG18a in apple improves resistance to Diplocarpon mali infection by enhancing antioxidant activity and salicylic acid levels. Horticulture Research 5, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Wang P, Jia X, Huo L, Che R, Ma F. 2018b Improvement of drought tolerance by overexpressing MdATG18a is mediated by modified antioxidant system and activated autophagy in transgenic apple. Plant Biotechnology Journal 16, 545–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttangkakul A, Li F, Chung T, Vierstra RD. 2011. The ATG1/ATG13 protein kinase complex is both a regulator and a target of autophagic recycling in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 23, 3761–3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenning S, Lamark T, Krause K, Johansen T. 2011. Plant NBR1 is a selective autophagy substrate and a functional hybrid of the mammalian autophagic adapters NBR1 and p62/SQSTM1. Autophagy 7, 993–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkowski ŁP, Van den Ende W. 2015. Cold tolerance triggered by soluble sugars: a multifaceted countermeasure. Frontiers in Plant Science 6, 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumm M, Egner R, Koch B, Schlumpberger M, Straub M, Veenhuis M, Wolf DH. 1994. Isolation of autophagocytosis mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Letters 349, 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyooka K, Moriyasu Y, Goto Y, Takeuchi M, Fukuda H, Matsuoka K. 2006. Protein aggregates are transported to vacuoles by a macroautophagic mechanism in nutrient-starved plant cells. Autophagy 2, 96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada M, Ohsumi Y. 1993. Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Letters 333, 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzatsos A, Kandror KV. 2006. Nutrients suppress phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling via raptor-dependent mTOR-mediated insulin receptor substrate 1 phosphorylation. Molecular and Cellular Biology 26, 63–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün S, Hafrén A, Liu Q, Marshall RS, Minina EA, Bozhkov PV, Vierstra RD, Hofius D. 2018. Bacteria exploit autophagy for proteasome degradation and enhanced virulence in plants. The Plant Cell 30, 668–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhee C, Zapotoczny G, Masquelier D, Ghislain M, Batoko H. 2011. The Arabidopsis multistress regulator TSPO is a heme binding membrane protein and a potential scavenger of porphyrins via an autophagy-dependent degradation mechanism. The Plant Cell 23, 785–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leene J, Han C, Gadeyne A, et al. 2019. Capturing the phosphorylation and protein interaction landscape of the plant TOR kinase. Nature Plants 5, 316–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Nolan TM, Yin YH, Bassham DC. 2019. Identification of transcription factors that regulate ATG8 expression and autophagy in Arabidopsis. Autophagy doi: 10.1080/15548627.2019.1598753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Zhao Y, Li Z, et al. 2018. Reciprocal regulation of the TOR kinase and ABA receptor balances plant growth and stress response. Molecular Cell 69, 100–112.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cai S, Yin L, Shi K, Xia X, Zhou Y, Yu J, Zhou J. 2015. Tomato HsfA1a plays a critical role in plant drought tolerance by activating ATG genes and inducing autophagy. Autophagy 11, 2033–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cao JJ, Wang KX, Xia XJ, Shi K, Zhou YH, Yu JQ, Zhou J. 2019. BZR1 mediates brassinosteroid-induced autophagy and nitrogen starvation in tomato. Plant Physiology 179, 671–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Yu B, Zhao J, et al. 2013. Autophagy contributes to leaf starch degradation. The Plant Cell 25, 1383–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Liu W, Hu W, Liu G, Wu C, Liu W, Zeng H, He C, Shi H. 2017. Genome-wide analysis of autophagy-related genes in banana highlights MaATG8s in cell death and autophagy in immune response to Fusarium wilt. Plant Cell Reports 36, 1237–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Shi L, Li L, Fu L, Liu Y, Xiong Y, Sheen J. 2019. Integration of nutrient, energy, light, and hormone signalling via TOR in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 70, 2227–2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q, Tzfadia O, Levy M, Weithorn E, Peled-Zehavi H, Van Parys T, Van de Peer Y, Galili G. 2016. hfAIM: a reliable bioinformatics approach for in silico genome-wide identification of autophagy-associated Atg8-interacting motifs in various organisms. Autophagy 12, 876–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano K, Matsuda N, Tanaka K. 2016. The ubiquitin signal and autophagy: an orchestrated dance leading to mitochondrial degradation. EMBO Reports 17, 300–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Wang P, He C, Shi H. 2017. MeWRKY20 and its interacting and activating autophagy-related protein 8 (MeATG8) regulate plant disease resistance in cassava. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 494, 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Bu F, Huang W, Chen L. 2019. Multiple regulatory levels shape autophagy activity in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 10, 532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Zhang Y, Xie X, Yue N, Li J, Wang XB, Han C, Yu J, Liu Y, Li D. 2018. Barley stripe mosaic virus γb protein subverts autophagy to promote viral infection by disrupting the ATG7–ATG8 interaction. The Plant Cell 30, 1582–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. 2005. Atg11 links cargo to the vesicle-forming machinery in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. Molecular Biology of the Cell 16, 1593–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto K, Jikumaru Y, Kamiya Y, Kusano M, Consonni C, Panstruga R, Ohsumi Y, Shirasu K. 2009. Autophagy negatively regulates cell death by controlling NPR1-dependent salicylic acid signaling during senescence and the innate immune response in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 21, 2914–2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto K, Shibata M, Kondo M, Oikawa K, Sato M, Toyooka K, Shirasu K, Nishimura M, Ohsumi Y. 2014. Organ-specific quality control of plant peroxisomes is mediated by autophagy. Journal of Cell Science 127, 1161–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue W, Nie X, Cui L, Zhi Y, Zhang T, Du X, Song W. 2018. Genome-wide sequence and expressional analysis of autophagy gene family in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Journal of Plant Physiology 229, 7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zess EK, Jensen C, Cruz-Mireles N, et al. 2019. N-terminal β-strand underpins biochemical specialization of an ATG8 isoform. PLoS Biology 17, e3000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zhu JY, Roh J, Marchive C, Kim SK, Meyer C, Sun Y, Wang W, Wang ZY. 2016. TOR signaling promotes accumulation of BZR1 to balance growth with carbon availability in arabidopsis. Current Biology 26, 1854–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YG, Zhang H. 2018. Formation and maturation of autophagosomes in higher eukaryotes: a social network. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 53, 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Wang J, Cheng Y, Chi YJ, Fan B, Yu JQ, Chen Z. 2013. NBR1-mediated selective autophagy targets insoluble ubiquitinated protein aggregates in plant stress responses. PLoS Genetics 9, e1003196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Wang J, Yu JQ, Chen Z. 2014. Role and regulation of autophagy in heat stress responses of tomato plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 5, 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T, Zou L, Li Y, Yao X, Xu F, Deng X, Zhang D, Lin H. 2018. Mitochondrial alternative oxidase-dependent autophagy involved in ethylene-mediated drought tolerance in Solanum lycopersicum. Plant Biotechnology Journal 16, 2063–2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang X, Wang H, Lam SK, Gao C, Wang X, Cai Y, Jiang L. 2013. A BAR-domain protein SH3P2, which binds to phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and ATG8, regulates autophagosome formation in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 25, 4596–4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]