Abstract

Objective

To classify NICU interventions for parental distress and quantify their effectiveness.

Study Design

We systematically reviewed controlled studies published before 2017 measuring NICU parental distress, defined broad intervention categories, and used random-effects meta-analysis to quantify treatment effectiveness.

Results

Among 1643 unique records, 58 eligible trials predominantly studied mothers of preterm infants. Interventions tested in 22 randomized trials decreased parental distress (p<0.001) and demonstrated improvement beyond 6 months (p<0.005). In subgroup analyses, complementary/alternative medicine and family-centered instruction interventions each decreased distress symptoms (p<0.01), with fathers and mothers improving to similar extents. Most psychotherapy studies decreased distress individually but did not qualify for meta-analysis as a group.

Conclusion

NICU interventions modestly reduced parental distress. We identified family-centered instruction as a target for implementation and complementary/alternative medicine as a target for further study. Investigators must develop psychosocial interventions that serve NICU parents at large, including fathers and parents of full-term infants.

INTRODUCTION

The hospitalization of one’s newborn in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) represents a potentially traumatic event for parents.1, 2 Individual parents exhibit profoundly heterogeneous psychological responses to the NICU hospitalization of their newborn infant as determined by multiple known and unknown infant, parent, and social factors.3

In the NICU environment, parents may feel their parenting role diminished as a result of professionals and policies governing interactions between parents and their infants.4 Parents may perceive the threat of their child’s disability or death when they see their newborn attached to medical devices and experiencing suffering or physiologic instability.5 As a consequence of these experiences, NICU parents can suffer from aspects of stress- and trauma-related distress such as anxiety, stress, or post-traumatic stress.6, 7 Prolonged postnatal distress harms parents’ mental health, disrupts the parent-infant relationship, and impairs children’s functioning and social-emotional development in the future.8–10

The general population faces a tangible risk of NICU-related parental distress. In the United States, about one in ten newborns receives care in a NICU.11 Many NICU parents experience some postnatal symptoms of post-traumatic stress.12 A meta-analysis of mothers of high-risk newborns reports that 18.5% meet diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after birth, compared with 4% of post-partum mothers in the community.13 The prevalence of postnatal distress among NICU fathers, as reported in single-site studies, ranges from 8 – 47%, compared to a baseline postnatal paternal rate of 6 – 8.7%.14–18

Even though experts and families recognize the burden of NICU-related distress and agree on the need for psychosocial support, standard practices for screening or supporting NICU parents are not in place universally.12, 19 Furthermore, it remains challenging for clinicians and investigators to choose the most promising approaches from among the eclectic collection of treatments that have been studied.

No prior review has comprehensively synthesized studies of interventions to reduce distress in NICU parents at large. Previous systematic reviews selected narrow scopes that limited their applicability across varied patient populations, treatment modalities, and psychological outcomes.20–24 First, few reviews examined the effect of interventions on fathers’ distress symptoms, even though NICU fathers experience birth-related psychological distress.25 Second, prior reviews predominantly assessed distress in parents of premature or very low birth weight infants, even though parents of critically ill full-term newborns are similarly susceptible to psychological distress.26 Third, no review has quantitatively synthesized the effect of diverse NICU interventions on parental PTSD using meta-analysis.

We undertook this systematic review and meta-analysis of NICU interventions for stress- and trauma-related parental distress to achieve the following aims: (1) to characterize the populations, interventions and outcomes reported in controlled studies; (2) to classify interventions targeting NICU-parental distress; (3) to estimate the overall effectiveness of interventions during NICU hospitalization and long-term; and (4) to compare treatment effectiveness among intervention classes, between mothers and fathers, and between short- and long-term outcomes. Through this analysis, we sought to identify the most promising treatment approaches for implementation by health systems and further study by investigators.

METHODS

We adhered to a predetermined protocol that specified study search strategy, eligibility criteria, methods of analysis, outcome variables, and effect direction.27 We describe the full methods in the supplemental materials.

Study Search & Selection

We searched PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and SCOPUS for studies published before 2017 using terms for the following concepts: hospitalized infants, parents, stress, anxiety, PTSD, and intervention. (Complete search terms are listed in supplemental materials.)

Three reviewers eliminated duplicate records and reviewed full-text reports to identify studies eligible for inclusion.

Study Eligibility Criteria

In the systematic review, we included English-language experimental studies (1) enrolling parents of infants admitted to a NICU, (2) testing interventions during or pertaining to the hospitalization, (3) reporting post-intervention parental anxiety, stress, or post-traumatic stress, and (4) comparing outcomes between NICU parents exposed to an intervention versus NICU parents exposed to a placebo treatment or usual care.

In order to synthesize study effects homogeneously, we excluded from review observational studies and studies with an exclusively pre-post design lacking a distinct control group. To decrease heterogeneity, we excluded from the meta-analysis studies that failed to report outcomes as unadjusted scores.

Data Collection

From each report included in the systematic review, we extracted information pertaining to the study, subjects, intervention, and outcomes. We separately collected and analyzed data for mothers and fathers when they were reported distinctly within a single study. We classified interventions into broad categories. Local experts in serious pediatric illness and parental adjustment corroborated the face validity of our intervention typology.

To account for the highly variable trajectories of distress symptoms individuals experience when faced with potentially traumatic events, we chose two time points for quantitative synthesis, (1) the latest in-hospital measurement, and (2) the most distal measurement reported.2 Despite wide variability in individual distress patterns, on average, parental distress symptoms are highest during the hospitalization and decline over time.28 To assess long-term treatment effects, we collected distress measurements most distal in time to intervention as our primary outcome. Therefore, when analyzing the primary outcome, for trials publishing serial reports from a single sample, we only included the report presenting the furthest time point; and for studies reporting outcomes at multiple time points, we only synthesized data from the furthest time point. To assess treatment effects during NICU hospitalization, a secondary outcome was the latest in-hospital distress measurement prior to NICU discharge, which we collected separately for studies reporting results at multiple time points.

Summary Measures

From studies eligible for meta-analysis, we collected anxiety and stress- or trauma-related distress scores. We included anxiety symptoms because, prior to the fifth and current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, stress- and trauma-related disorders were sub-classified as anxiety disorders.29

The primary measure of treatment effect for meta-analysis was the standardized mean difference (SMD) in distress symptoms between the intervention and control groups (i.e., control subtracted from intervention). We classified negative SMD values as favoring intervention. We reversed signs when necessary to yield consistent inter-group SMDs.

We aggregated measures of stress, trauma, and anxiety for meta-analysis. To harmonize numerous psychometric instruments for distress symptoms, we calculated the Z-score ([study mean – group mean] ÷ group standard deviation) and the standardized standard deviation (study standard deviation ÷ group standard deviation) for each reported instrument. For studies reporting the results of multiple instruments from the same subjects, we calculated weighted averages of Z-scores to provide composite measurements of distress for each study group.

Meta-analysis

We predicted a lack of common treatment effect among studies testing heterogeneous interventions. Therefore, to quantify the overall effectiveness of interventions, we employed the random effects meta-analysis method of DerSimonian and Laird.30 We assessed heterogeneity among study effect estimates using both Higgins’ I2 and Cochran’s Q statistics. We used funnel plots and Egger’s test to detect reporting bias pertaining to the relationship between sample size and effect size. We expected randomized studies to have lower risk of bias than non-randomized experimental studies, therefore they were analyzed separately.

We carried out meta-analysis procedures in Stata/SE version 14 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) using the following programs: metan to conduct random-effects meta-analysis, metafunnel to generate funnel plots, and metabias to carry out Egger’s test.31

Additional Analyses

We conducted pre-determined subgroup analyses of randomized studies eligible for meta-analysis to assess the comparative effectiveness of interventions (1) among intervention classes, (2) between mothers and fathers, and (3) on short-term and long-term outcomes. We conducted one post-hoc sensitivity analysis to determine the overall and subgroup effect sizes after excluding studies conducted in Iran that, as a group, were outliers favoring intervention compared to studies conducted elsewhere.

RESULTS

Study Selection

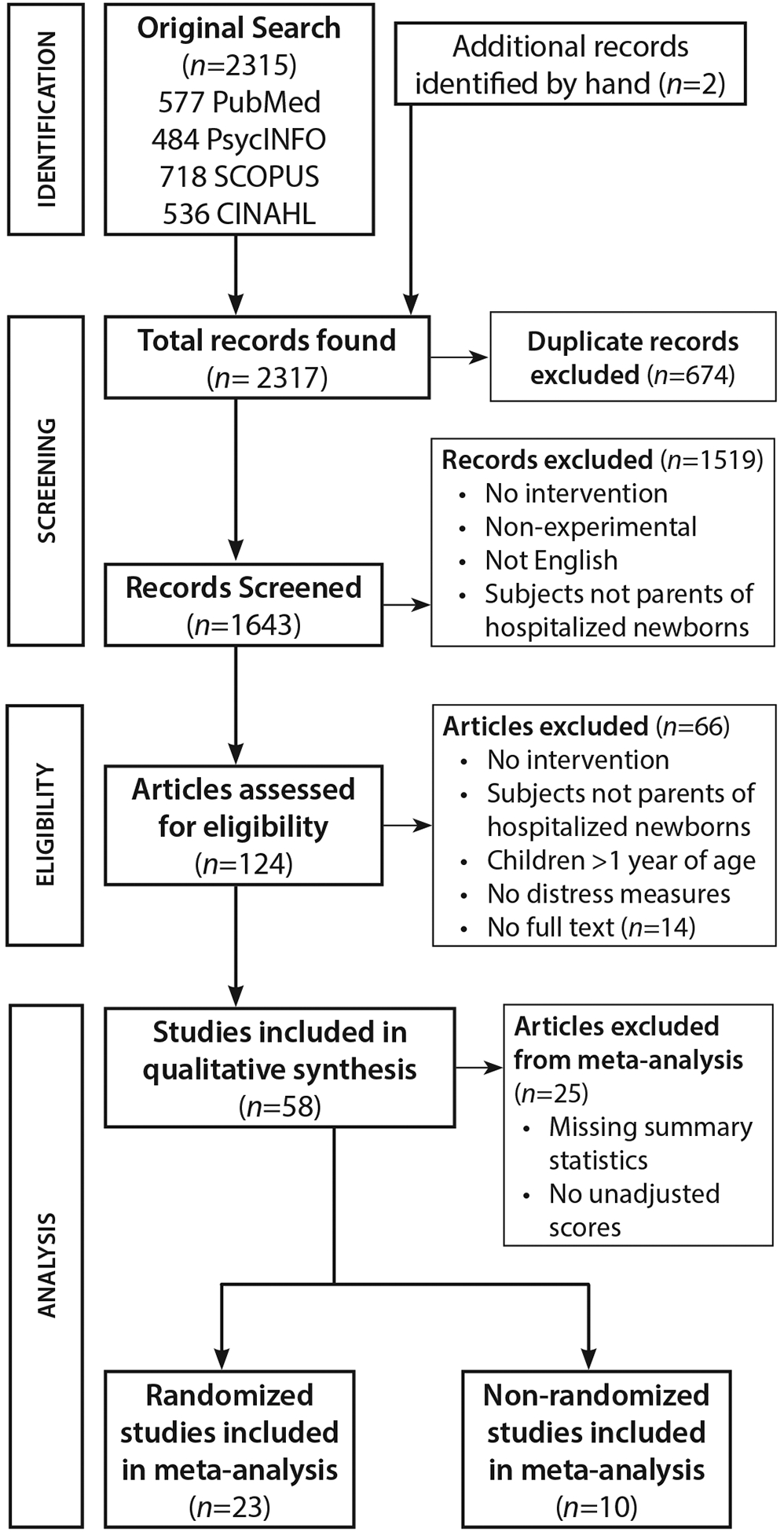

A study selection flow diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the process we undertook to select 58 controlled studies of interventions for NICU parental distress for systematic review (references listed in supplemental materials). Among those, we quantitatively synthesized 23 randomized, and 10 non-randomized, controlled studies.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

Study Characteristics

The 58 studies we reviewed enrolled 5,887 parent subjects (Table 1). The median year of publication for this body of literature was 2013. Twenty studies were conducted in North America, sixteen in Europe, nine in Iran, seven in Asia, three in Australia, and three in Brazil.

Table 1.

Controlled studies of interventions to reduce NICU parental distress.

| First Author | Year | Country | Subjects Enrolled | Parents(†) | Randomized | Intervention | Distress Measures | Instruments | Significant Difference(ǂ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changing NICU medical care | |||||||||

| Meyer* | 1994 | USA | 34 | m | Yes | Individualized interventions like observing newborn behavior assessment or participating in caregiving or discharge preparation for mothers of preterm infants. | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Rieger | 1995 | Australia | 118 | m | No | NEDP focused on discharge and transition for mothers of preterm infants. | Anxiety | STAI | 0 |

| Preyde* | 2003 | Canada | 59 | m | No | Parent-to-parent support groups for mothers of preterm infants | Anxiety | STAI, PSS-NICU | + |

| Singh | 2003 | India | 200 | f | No | Fathers were permitted to visit the bedside and offered clinical updates in a NICU where the standard policies prohibited fathers. | Anxiety | Original survey | + |

| Koh*° | 2007 | Australia | 32 | m | Yes | Parents were given an audiotape of their initial conversations with their infants’ neonatologist. | Anxiety | STAI | 0 |

| Erdeve* | 2009 | Turkey | 49 | m | No | Mothers and preterm infants were hospitalized together. | Stress | PSI | 0 |

| Liu | 2010 | Taiwan | 70 | m+f | No | Support groups provided parents of preterm infants with empowerment strategies. | Stress | Perceived Stress Scale | 0 |

| Pineda* | 2012 | USA | 81 | m | No | Preterm newborns were assigned single-patient NICU rooms vs. open-bay beds. | Anxiety, Stress | STAI, PSS-NICU, PSI | 0 |

| O’Brien* | 2013 | Canada | 56 | m | No | FIC tightly incorporated mothers in their preterm infants’ care. | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Weis* | 2013 | Denmark | 134 | m+f | Yes | GFCC helped parents of preterm infants manage distress and care decisions. | Stress | PSS-NICU | 0 |

| Clarke-Pounder*° | 2015 | USA | 19 | m | Yes | NICU DMT elicited parental values and preferences about medical decisions. | Anxiety | STAI | - |

| Complementary/alternative medicine | |||||||||

| Barry* | 2001 | USA | 38 | m | Yes | Mothers wrote daily about their most emotional NICU experiences. | PTSD | IES, SCL-90-R | + |

| Feijo*° | 2006 | USA | 40 | m | Yes | Infant massage by mothers. | Anxiety | STAI | + |

| Lai | 2006 | Taiwan | 30 | m | Yes | Mother–preterm-infant dyads were exposed to music during kangaroo care. | Anxiety | STAI | + |

| Flacking | 2013 | Sweden | 300 | m | No | Skin-to-skin contact with mothers of preterm infants in co-care facilities. | Stress | PSI | 0 |

| Haddad-Rodrigues*° | 2013 | Brazil | 29 | m | Yes | Weekly acupuncture on ears of mothers of preterm infants. | Anxiety | STAI | 0 |

| Holditch-Davis | 2014 | USA | 240 | m | Yes | Mothers provided kangaroo care or auditory, tactile, visual, vestibular stimulation to their preterm infants. | Anxiety, PTSD | STAI, PPQ | + |

| Kadivar* | 2015 | Iran | 70 | m | No | Mothers performed narrative writing at least three times within 10 days of their preterm infant’s hospitalization. | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Mörelius | 2015 | Sweden | 37 | m+f | Yes | Mother–preterm-infant skin-to-skin contact | Stress | SPSQ | 0 |

| Afand* | 2016 | Iran | 70 | m | No | Preterm infants massage by mothers. | Anxiety | STAI | + |

| Fotiou* | 2016 | Greece | 59 | m+f | Yes | Parents of preterm infants practiced deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery. | Anxiety, Stress | STAI, Perceived Stress Scale | + |

| Sharifinia | 2016 | Iran | 60 | m | Yes | Mothers of premature infants listened to Tavassol prayer daily. | Anxiety, Stress | DASS | 0 |

| Cho | 2016 | South Korea | 40 | m | No | Kangaroo care with preterm infants | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Family-centered Instruction | |||||||||

| Culp | 1989 | USA | 14 | m+f | No | Parents learned assessment of premature infant behavior. | Anxiety | STAI | + |

| Cobiella | 1990 | USA | 30 | m | Yes | Educational videotapes taught mothers to address anxiety and confidently care for their preterm infants. | Anxiety, Stress | STAI, PSS-NICU | + |

| Melnyk*° | 2001 | USA | 42 | m | Yes | COPE taught parents how to integrate into their preterm, low-birth weight infants’ care. | Stress | PSS-NICU | 0 |

| Browne | 2005 | USA | 84 | m | Yes | Mothers were taught to elicit their preterm infants’ normal reflexes. | Stress | PSI | + |

| Kaaresen* | 2006 | Norway | 235 | m+f | Yes | MITP taught parents to observe preterm infant’s state and to use positive stimulation. | Stress | PSI | + |

| Melnyk*° | 2006 | USA | 386 | m+f | Yes | COPE taught parents how to integrate into their preterm infants’ care. | Anxiety, Stress | STAI, PSS-NICU | + |

| Glazebrook | 2007 | UK | 199 | m | Yes | PBIP taught parents to identify preterm infant cues. | Stress | PSI | 0 |

| Van de Pal | 2007 | Netherlands | 283 | m+f | Yes | NIDCAP modified preterm infants’ environment and caregiving. | Stress | PSS-NICU | 0 |

| Turan*° | 2008 | Turkey | 76 | m+f | Yes | 30-minute parent education program about their preterm infant and the NICU. | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Van de Pal* | 2008 | Netherlands | 128 | m+f | Yes | NIDCAP modified preterm infants’ environment and caregiving. | Stress | PSI | 0 |

| Carvalho | 2009 | Brazil | 59 | m | Yes | Mothers of preterm infants received psychological support through audiovisual and print materials. | Anxiety | STAI | 0 |

| Newnham* | 2009 | Australia | 63 | m | Yes | MITP taught parents to observe preterm infant’s state and to use positive stimulation. | Stress | PSI | + |

| Zelkowitz° | 2011 | Canada | 98 | m | Yes | Cues & Care taught mothers to address distress in their VLBW infants and themselves. | Anxiety, PTSD | STAI, PPQ | 0 |

| Franck*° | 2011 | USA | 169 | m+f | Yes | Parents received a pain information booklet and instructions on preterm infant comforting techniques. | Stress | PSS-NICU | 0 |

| Feeley* | 2012 | Canada | 96 | m | Yes | Cues & Care taught mothers to address distress in their VLBW infants and themselves. | Anxiety, PTSD | STAI, PPQ | 0 |

| Ravn* | 2012 | Norway | 100 | f | Yes | MITP taught parents to observe preterm infant’s state and to use positive stimulation. | Stress | PSI | 0 |

| Borimnejad* | 2013 | Iran | 140 | m | No | COPE taught parents how to integrate into their preterm infants’ care. | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Lee* | 2013 | Taiwan | 69 | f | No | Fathers received a booklet about their premature infant’s care and individualized guidance from a nurse. | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Matricardi | 2013 | Italy | 42 | m+f | Yes | A physical therapist taught parents to observe their preterm infant’s behavior and provide positive stimulation during therapy sessions. | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Borghini* | 2014 | Switzerland | 78 | m | Yes | Parents learned about their preterm infant’s behaviors and their own reactions to them with the help of a therapist. | PTSD | PPQ | 0 |

| Landsem* | 2014 | Norway | 234 | m+f | Yes | MITP taught parents to observe preterm infant’s state and to use positive stimulation. | Stress | PSI | + |

| Mianaei* | 2014 | Iran | 90 | m | Yes | COPE taught parents how to integrate into their preterm infants’ care. | Anxiety, Stress | STAI, PSS-NICU | + |

| Abdeyazdan* | 2014 | Iran | 50 | m+f | No | Face-to-face education about the NICU environment and preterm infant’s care. | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Beheshtipour* | 2014 | Iran | 100 | m+f | Yes | Parents received face-to-face information about the NICU, their preterm infant’s condition, resources for spouse support, and problem solving strategies. | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Hoffenkamp | 2015 | Netherlands | 294 | m+f | Yes | VIG provided parents with positive feedback on video recordings with their preterm infants. | Anxiety | STAI | 0 |

| Balbino | 2016 | Brazil | 132 | m+f | No | The Patient and Family-Centered Care Model promoted the inclusion of the family in the NICU and infants’ care. | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

| Barlow | 2016 | UK | 31 | m+f | Yes | VIG provided parents with positive feedback on video recordings with their infants. | PTSD, Stress, Anxiety | PSI, PC-PTSD, HADS | 0 |

| Welch | 2016 | USA | 115 | m | Yes | Family Nurture Intervention provided mothers and preterm infants with calming activities. | Anxiety | STAI | + |

| Goudarzi | 2016 | Iran | 42 | m | Yes | Face-to-face education about intestinal disease and care for mothers of infants with colostomies. | Anxiety, Stress | DASS | 0 |

| Valizadeh | 2016 | Iran | 99 | m | Yes | Mothers of preterm infants oriented to the NICU environment through a film or booklet. | Anxiety | STAI, CAQ | + |

| Psychotherapy | |||||||||

| Jotzo* | 2005 | Germany | 50 | m | No | One-off crisis intervention combined with additional professional psychological aid for mothers of preterm infants | PTSD | IES | + |

| Bernard* | 2011 | USA | 50 | m | Yes | Cognitive-behavioral therapy for mothers of preterm infants | PTSD | DTS, SASQR | 0 |

| Shaw | 2013 | USA | 105 | m | Yes | TF-CBT, cognitive processing therapy, and psychoeducation for mothers of preterm infants | Anxiety, PTSD | DTS, BAI | + |

| Shaw | 2014 | USA | 105 | m | Yes | TF-CBT for mothers of preterm infants | Anxiety, PTSD | DTS, BAI | + |

| Cano Giménez | 2015 | Spain | 134 | m+f | No | Five-step individualized intervention program delivered by a psychologist to parentrs of term infants | Stress | PSS-NICU | + |

Symbols —

Included in meta-analysis of long-term (primary) outcome;

Included in meta-analysis of pre-discharge (secondary) outcome;

Mothers (m), Fathers (f), Both (m+f);

Significant Improvement (+), Significant Worsening (−), No significant difference (0)

Interventions — COPE: Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment; DMT: Decision Making Tool; FIC: Family Integrated Care; GFCC: Guided Family-Centered Care; MITP: Mother infant transaction program; NEDP: Neonatal Early Discharge and Family Support Program; NIDCAP: Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program; PBIP: Parent Baby Interaction Program; TF-CBT: Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy; VIG: Video Interaction Guidance.

Instruments — BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; CAQ: Cattel’s Anxiety Questionnaire; DASS: Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; DTS: Davidson Trauma Scale; IES: Impact of Events Scale; PC-PTSD: Primary Care–Post-traumatic Stress Disorder; PPQ: Perinatal Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire; PSI: Parenting Stress Index; PSS:NICU: Parental Stressor Scale: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; PSS: Parental Stressor Scale; SASRQ: Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire; SCL-90-R: Symptom Check List-90-Revised; SPSQ: Swedish Parenthood Stress Questionnaire; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Studies predominantly enrolled mothers and parents of preterm infants. Thirty-six studies tested interventions exclusively on mothers while three studies enrolled only fathers and 19 studies enrolled both mothers and fathers. Six studies permitted enrollment of full-term infants.

Intervention Classification

We classified 46 distinct interventions into four broad categories: (1) Changing NICU medical care; (2) Complementary/alternative medicine; (3) Family-centered instruction; and (4) Psychotherapy.

We classified as ‘Changing NICU medical care’ eleven studies that altered parents’ exposure to the organization or delivery of medical treatment performed by nurses or physicians as compared to contemporaneous local standards of care. Interventions in this class primarily targeted other outcomes alongside distress. Interventions that changed infant rooming or visiting conditions aimed to enhance parent-infant bonding. Parent-to-parent support groups provided families with social resources during a uniquely challenging experience.32 Interventions that integrated parents directly in their infant’s medical care empowered parents to fulfill their parental role.33 Parent-professional communication interventions aimed to improve comprehension or shared medical decision making.34

We drew on classifications by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health to determine eligibility in the category ‘Complementary/alternative medicine’.35 We included twelve studies that introduced mind-body modalities originating outside the allopathic medical tradition. Interventions in this class typically were designed to decrease stress. Mind-body modalities included maternal acupuncture, journal writing, relaxation techniques, music interventions, infant massage, and parent-infant skin-to-skin contact. Consistent with the recent growth of complementary/alternative medicine use among the general population, these publications were the most recent, with a median publication year of 2015.36

The most frequently studied class of intervention was formed by multi-faceted programs of ‘Family-centered instruction.’ These interventions in 30 studies predominantly focused on the developmental trajectory of premature infants. In their meta-analysis, Benzies et al developed a classification for the components of this intervention category comprised by (1) parent psychosocial support; (2) parent education in the form of either information alone, guided infant observation, or active parent involvement with professional feedback; and (3) infant developmental support.21

Finally, in five ‘Psychotherapy’ studies, licensed mental health professionals administered psychological therapy, frequently an application of cognitive-behavioral therapy explicitly designed to remedy distress symptoms, face-to-face with parents during their child’s NICU hospitalization.

Distress Instruments

Stress was the most frequently assessed aspect of distress, measured in 25 reports using the Parental Stressor Scale:NICU and in 10 reports using the Parenting Stress Index. Seventeen studies measured anxiety using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Post-traumatic stress symptoms were assessed using the Perinatal Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire in four studies and the Davidson Trauma Scale in three studies. All reported instruments for stress, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress are listed in Table 1.

Randomized Studies Meta-analysis

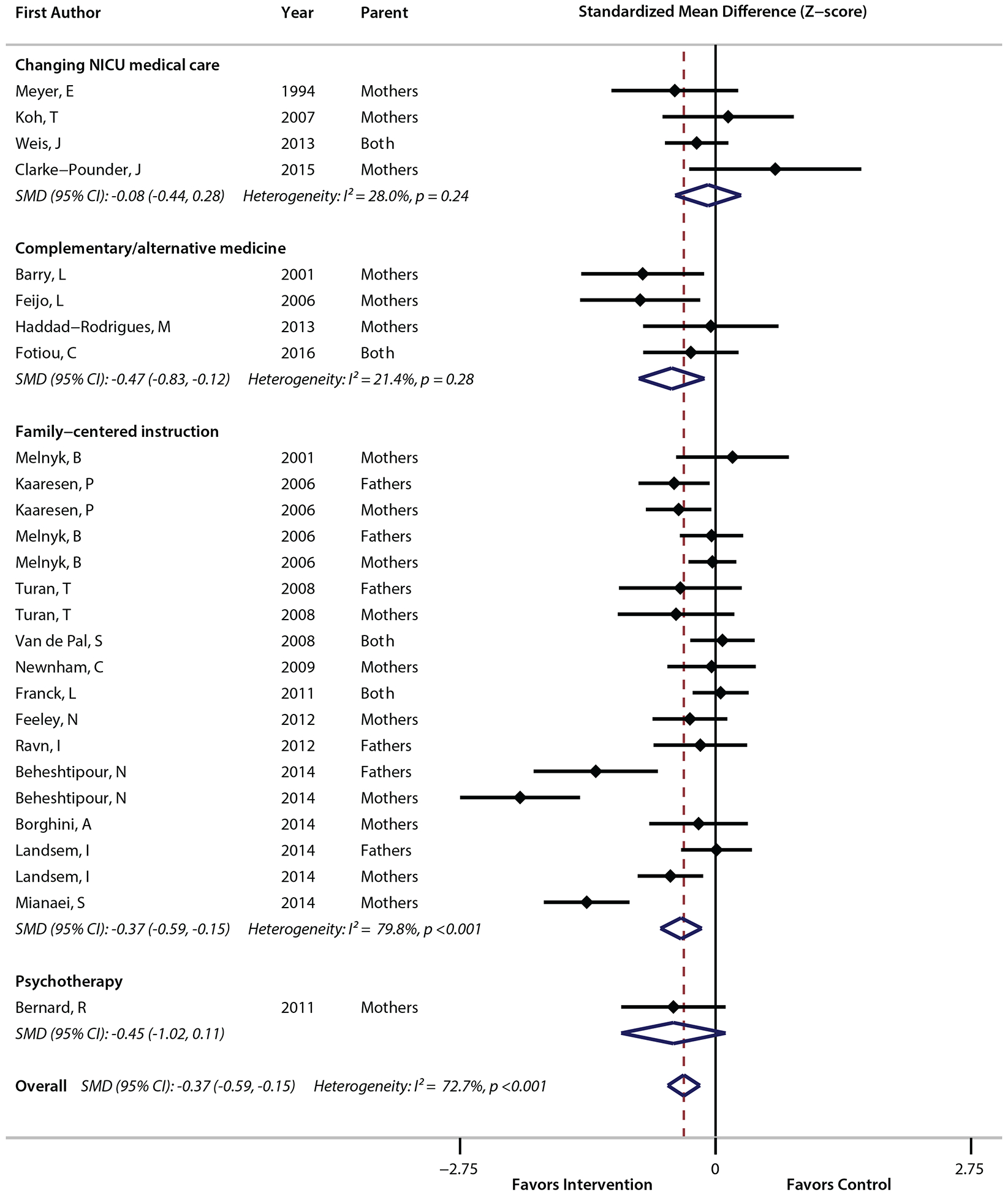

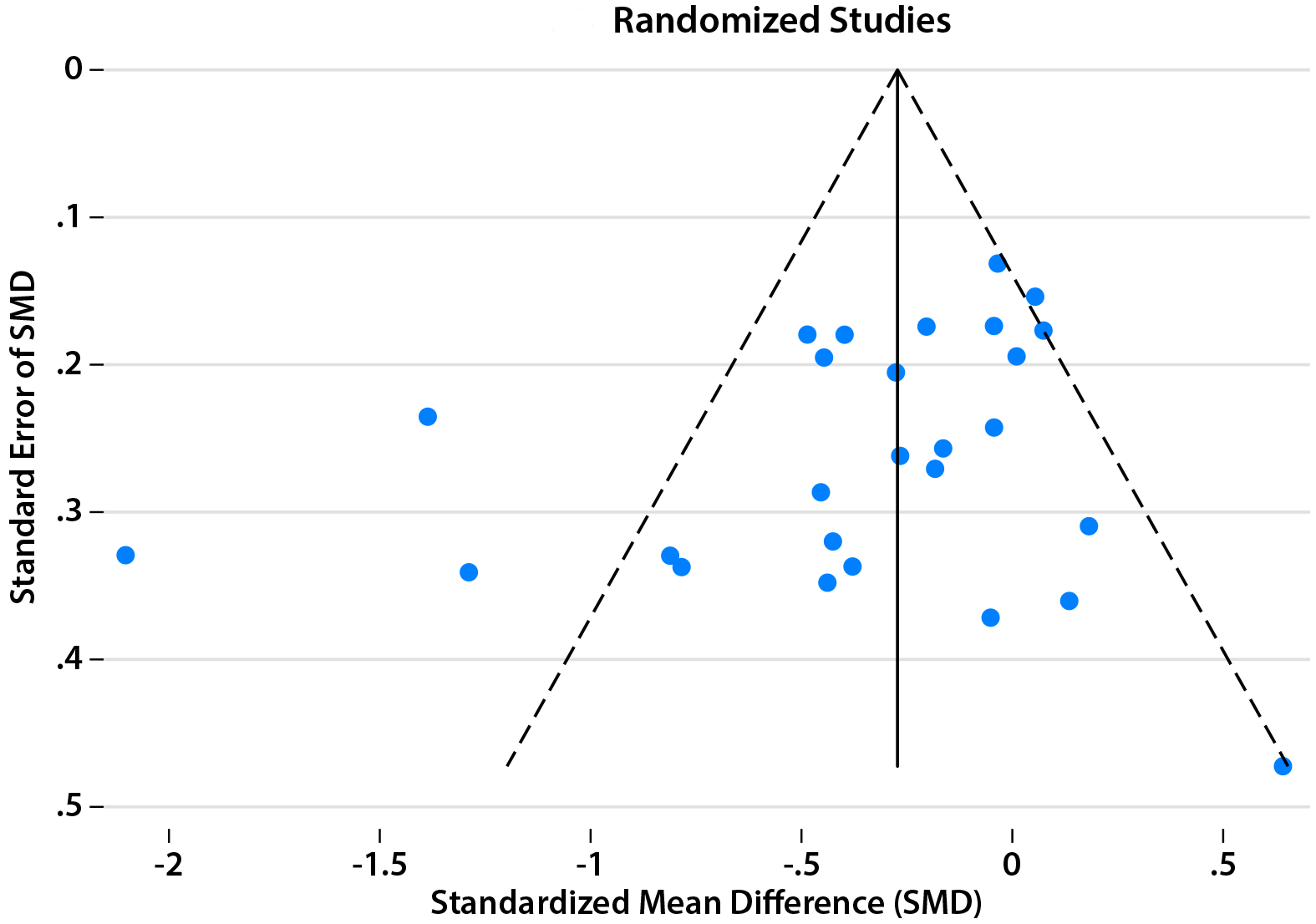

When assessed for our primary outcome, the effect size at the latest-reported time point, NICU-based interventions modestly decreased stress- or trauma-related distress in NICU parents at large. The cumulative effect was a one-third standard deviation reduction in distress symptoms across multiple psychometric measures (N=22; SMD: −0.34, 95% CI (−0.51, −0.17); p<0.001) with a high level of heterogeneity among study effect estimates (I2 = 72.7%, Cochran’s Q p<0.001) (Figure 2). The bulk of analyzed randomized studies did not exhibit evidence of reporting bias, with a negative Egger’s test (p= 0.09) and study effect sizes fairly symmetrically distributed in a funnel plot (Figure 3). The three outliers on the funnel plot represent two studies conducted in Iran that we excluded in a post-hoc sensitivity analysis described below.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of randomized studies. (SMD – standardized mean difference)

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of randomized studies. Three outlier effect sizes represent two studies by Behestipour et al and Mianaei et al that were excluded in post-hoc sensitivity analysis.

In subgroup analyses of randomized studies, interventions categorized as ‘Complementary/alternative medicine’ (N=4; SMD: −0.47 [−0.83, −0.12]; p<0.01) and ‘Family-centered instruction’ (N=13; SMD: −0.37 [−0.59, −0.15]; p=0.001) reduced parental distress symptoms. ‘Changing NICU medical care’ interventions (N=4; SMD: −0.08 [−0.44, 0.28]; p>0.05) did not decrease parental distress overall. Only one randomized ‘Psychotherapy’ study was eligible for quantitative synthesis, thus this category could not be assessed in this analysis.

When assessed for our secondary outcome, randomized studies reporting treatment effects prior to NICU discharge did not decrease distress symptoms, neither overall (N=9; SMD −0.08 [−0.24, 0.09]; p>0.05) nor within any intervention classification subgroup (p>0.05). These studies did not exhibit evidence of reporting bias, with a symmetric funnel plot (not shown) and a negative Egger’s test (p=0.7).

Effects in Mothers and Fathers

Family-centered instruction interventions decreased distress symptoms in mothers and fathers by similar magnitudes (mothers’ SMD: −0.5 [−0.85, −0.14], p<0.01; fathers’ SMD: −0.32 [−0.64, −0.01], p<0.05). Among randomized studies, only studies in this class distinctly reported results for fathers. These studies predominantly enrolled parents of preterm infants.

Long-term Distress Reduction

The furthest time of distress measurement within studies ranged from 1 day to 9 years in the 21 studies that specified timing (median 90 days, interquartile range [10 days, 1 year]). Half of the 16 randomized studies specifying timing measured distress symptoms 6 months or later after intervention. Overall, these interventions decreased long-term parental distress symptoms (SMD: −0.22 [−0.38, −0.07]; p<0.005) with a low level of heterogeneity (I2 = 18%, Cochran’s Q p=0.28).

Post-hoc Sensitivity Analysis

The two eligible randomized studies conducted in Iran produced considerably larger effect sizes favoring intervention than studies conducted elsewhere. A post-hoc sensitivity analysis excluding these studies yielded results consistent with our initial findings. The remaining interventions reduced parental distress (N=20; SMD −0.19 [−0.29, −0.09], p<0.001), and, among them, complementary/alternative medicine and family-centered instruction interventions decreased distress (p<0.01).

Non-Randomized Studies Meta-analysis

Assessed for our primary outcome, the effect size at the latest-reported time point, ten non-randomized studies eligible for meta-analysis reduced parental distress overall (SMD: −0.99, 95% CI [−1.56, −0.41], p=0.001) with a high level of heterogeneity (I2 = 91.4%, Cochran’s Q p<0.001) (Supplemental Figure A). A symmetric funnel plot of non-randomized studies (Supplemental Figure B) as well as a negative Egger’s test (p=0.98) suggest the absence of evident reporting bias. ‘Complementary/alternative medicine’ and ‘Family-centered instruction’ interventions in non-randomized studies decreased distress symptoms (p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

We believe this is the first comprehensive synthesis of the diverse body of literature on NICU-based interventions for parental distress. To produce a synthesis applicable to NICU parents at large, we analyzed controlled studies of the effect of NICU interventions on stress- or trauma-related distress, regardless of treatment modality, parent sex, or newborn gestational age. We classified a diverse array of treatments into broad categories, and we quantified their effectiveness, altogether and within classes.

In light of recommendations to provide psychosocial support to all NICU parents, this review serves clinicians and health systems by highlighting priorities for implementation. By identifying gaps in the literature, this review serves investigators by identifying opportunities for the further study of available modalities as well as the development of novel treatments.

Overall, NICU interventions produce modest reductions in parental distress symptoms in the long term, though not necessarily when measured prior to hospital discharge. This holds true comparably for mothers and fathers, and the benefits persist in studies measuring distress after 6 months. With these findings, this review encourages NICU parents to expect psychosocial support regardless of their sex or their child’s gestational age.

Family-centered instruction interventions, which are multi-faceted programs that provide in-hospital parent education, reduce parental distress symptoms and represent the clearest implementation opportunity for health systems not already providing such a program. However, prior reviewers have commented on the challenges of operationalizing this class of intervention owing to the heterogeneity of treatment components, clinical sites, and families.21, 37 In addition, these programs are designed chiefly to address the developmental needs of preterm infants. Therefore, this category also presents an opportunity for investigators to develop family-centered instruction programs with the flexibility to support parents with infants at any gestational age.

Complementary/alternative medicine approaches represent a promising area for further research because, based on our small and heterogeneous sample, they decrease parental distress. This class of intervention is often relatively inexpensive to implement and enjoys growing acceptance amongst the public. Four randomized complementary/alternative medicine studies eligible for meta-analysis tested a diverse set of mind-body modalities including acupuncture, journaling, relaxation, and kangaroo care, a form of skin-to-skin parent-infant contact commonly used in the care of preterm infants.38 Mind-body modalities might move from the margins of neonatology into the mainstream, for instance, through large-scale, randomized controlled trials of practices such as journaling or meditation.

Interventions that changed NICU medical care had an overall null effect on parental distress symptoms. This finding suggests that investigators testing changes to medical treatments that impact parents should assess for unintended parental distress, as was evident in a communication intervention reported by Clarke-Pounder et al.39 Furthermore, although adult intensive care studies have demonstrated reductions in family distress symptoms following intensive communication interventions, in this study, the few neonatal studies testing communication interventions did not mirror those results.34 The risk of mortality is considerably greater in adult intensive care than in NICUs, and we can speculate that subsets of NICU parents, such as parents of newborns facing a high risk of death, may experience greater distress reductions than NICU parents at large. This review identifies an opportunity for large-scale studies to test the effect of intensive communication interventions on NICU parental distress.

We were unable to quantitatively synthesize psychotherapy studies in this meta-analysis. We note that four of the five psychotherapy studies we reviewed reported parental distress reductions. Among them, the series of randomized studies by Shaw et al demonstrated significant reductions in parental distress after trauma-focused CBT, however, they reported results as adjusted estimates, excluding them from our meta-analysis.40, 41 Future studies could apply meta-regression techniques to appropriately synthesize adjusted results in this body of literature. Current recommendations endorse professional psychotherapy for NICU parents experiencing significant stress- or trauma-related distress during their child’s hospitalization.42

Limitations

This body of literature contains gaps and imbalances with respect to geography, parent sex, infant gestational age, and distress time course, that impose limitations on the generalizability of our findings.

Most studies eligible for systematic review were conducted in North America or Europe, limiting the global generalizability of these findings. We speculate that social resources and norms that vary across regional and cultural contexts will influence treatment effectiveness, a potential explanation for the considerably larger effect sizes found in studies conducted in Iran. Investigators have the opportunity to translate these findings to diverse settings globally.

Fewer than half of reviewed studies enrolled fathers, and many that did failed to report outcomes for fathers distinctly. Fathers have an important role to play in the social-emotional development of high risk infants and in the well-being of their family. Therefore, the omission of fathers from this body of literature has consequences not only for fathers but for their partners and their children, as well.43 In light of our finding that fathers respond to interventions as well as mothers do, investigators must develop and test interventions designed to address the psychosocial needs of both mothers and fathers.

Only one in ten eligible studies enrolled parents of full-term infants, thereby omitting a class of parents no less susceptible to stress- and trauma-related distress.3 While preterm infants are typically hospitalized because of problems related to their developmental immaturity, term infants in a NICU can have medical problems ranging from transient to grave. NICU patients of all gestations can face a wide range of risk for death or disability. Investigators must design interventions that treat NICU parents at large, regardless of their newborn’s gestational age.

Several reviewed studies failed to specify the timing of distress observation. Investigators can demonstrate the impact of interventions over variable patterns of distress symptoms by reporting outcomes at multiple discrete timepoints both during the hospitalization and long after discharge.

Finally, our classifying an eclectic array of interventions into broad categories brought disparate treatments together, losing the specificity of interventions as they were implemented in individual studies. Aggregating diverse interventions across varied patient populations, measured by disparate instruments, allowed us to estimate an overall treatment effect for parental distress. Although our effect estimate reflects this body of literature, the heterogeneity of the underlying treatments limits the prediction of an effect size for a given intervention in the future.

Conclusions

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we found a modest, long-term improvement in parental stress- and trauma-related distress resulting from NICU-based interventions. Based on their effectiveness at reducing distress, we identified opportunities for implementing family-centered instruction programs, and for developing complementary/alternative medicine interventions, each ideally designed to serve NICU parents at large.

By identifying omissions in this body of literature, we highlighted several opportunities for future research. Investigators have the opportunity to develop and test interventions in many regions of the world currently lacking research on NICU parental distress. Future studies ideally will assess the effectiveness of treatments across a lengthy postnatal span. Finally, we found that this field of research has predominantly limited its scope to the mothers of preterm infants, highlighting an imperative to develop and test psychosocial interventions flexible enough to serve NICU parents at large, including fathers and the parents of critically ill full-term infants.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Bethany Myers for library guidance, Sitaram Vangala for statistical guidance, Isabell Purdy for intervention-classification input, and Catherine Mogil for critical feedback. Database services provided by NIH/NCATS grant UL1TR000124. This study was supported by a UCLA Mattel Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute Seed Grant.

FUNDING SOURCE: This study was supported in part by the UCLA Mattel Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. This study was supported exclusively by intramural funding.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have no conflicts of interest and no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Supplementary information is available at JPER’s website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanders MR, Hall SL. Trauma-informed care in the newborn intensive care unit: promoting safety, security and connectedness. J Perinatol 2018, 38(1): 3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonanno GA, Westphal M, Mancini AD. Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2011, 7: 511–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schappin R, Wijnroks L, Uniken Venema MM, Jongmans MJ. Rethinking stress in parents of preterm infants: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013, 8(2): e54992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodward LJ, Bora S, Clark CA, Montgomery-Honger A, Pritchard VE, Spencer C, et al. Very preterm birth: maternal experiences of the neonatal intensive care environment. J Perinatol 2014, 34(7): 555–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulais J, Vente T, Daley M, Ramesh S, McGuirl J, Arzuaga B. Concern for mortality in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU): parent and physician perspectives. J Perinatol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeffcoate JA, Humphrey ME, Lloyd JK. Role perception and response to stress in fathers and mothers following pre-term delivery. Soc Sci Med 1979, 13A(2): 139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parent Treyvaud K. and family outcomes following very preterm or very low birth weight birth: a review. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2014, 19(2): 131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman C, Dunn DM, Njoroge WFM. Impact of postpartum mental illness upon infant development. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017, 19(12): 100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garthus-Niegel S, Ayers S, Martini J, von Soest T, Eberhard-Gran M. The impact of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms on child development: a population-based, 2-year follow-up study. Psychol Med 2017, 47(1): 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huhtala M, Korja R, Lehtonen L, Haataja L, Lapinleimu H, Rautava P, et al. Associations between parental psychological well-being and socio-emotional development in 5-year-old preterm children. Early Hum Dev 2014, 90(3): 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States Department of Health and Human Services / Health Resources and Services Administration / Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Child health USA 2013. Rockville, MD, USA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hynan MT, Mounts KO, Vanderbilt DL. Screening parents of high-risk infants for emotional distress: rationale and recommendations. J Perinatol 2013, 33(10): 748–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yildiz PD, Ayers S, Phillips L. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2017, 208: 634–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefkowitz DS, Baxt C, Evans JR. Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2010, 17(3): 230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cyr-Alves H, Macken L, Hyrkas K. Stress and symptoms of depression in fathers of infants admitted to the NICU. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2018, 47(2): 146–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw RJ, Bernard RS, Deblois T, Ikuta LM, Ginzburg K, Koopman C. The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in the neonatal intensive care unit. Psychosomatics 2009, 50(2): 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aftyka A, Rybojad B, Rosa W, Wrobel A, Karakula-Juchnowicz H. Risk factors for the development of post-traumatic stress disorder and coping strategies in mothers and fathers following infant hospitalisation in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs 2017, 26(23–24): 4436–4445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philpott LF, Leahy-Warren P, FitzGerald S, Savage E. Stress in fathers in the perinatal period: A systematic review. Midwifery 2017, 55: 113–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hynan MT, Hall SL. Psychosocial program standards for NICU parents. J Perinatol 2015, 35 Suppl 1: S1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brecht C, Shaw RJ, Horwitz SM, John NH. Effectiveness of therapeutic behavioral interventions for parents of low birth weight premature infants: A review. Infant Ment Health J 2012, 33(6): 651–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benzies KM, Magill-Evans JE, Hayden KA, Ballantyne M. Key components of early intervention programs for preterm infants and their parents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13 Suppl 1: S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraljevic M, Warnock FF. Early educational and behavioral RCT interventions to reduce maternal symptoms of psychological trauma following preterm birth: a systematic review. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2013, 27(4): 311–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendelson T, Cluxton-Keller F, Vullo GC, Tandon SD, Noazin S. NICU-based interventions to reduce maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017, 139(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Kurtz M, Lee SY, Liu H. Early intervention for preterm infants and their mothers: a systematic review. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sisson H, Jones C, Williams R, Lachanudis L. Metaethnographic synthesis of fathers’ experiences of the neonatal intensive care unit environment during hospitalization of their premature infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2015, 44(4): 471–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeMier RL, Hynan MT, Harris HB, Manniello RL. Perinatal stressors as predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress in mothers of infants at high risk. J Perinatol 1996, 16(4): 276–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009, 6(7): e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holditch-Davis D, Miles MS, Weaver MA, Black B, Beeber L, Thoyre S, et al. Patterns of distress in African-American mothers of preterm infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2009, 30(3): 193–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986, 7(3): 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer TM, Sterne JAC (eds). Meta-analysis in Stata: An Updated Collection from the Stata Journal. Stata Press: College Station, TX, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall SL, Ryan DJ, Beatty J, Grubbs L. Recommendations for peer-to-peer support for NICU parents. J Perinatol 2015, 35 Suppl 1: S9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Brien K, Bracht M, Macdonell K, McBride T, Robson K, O’Leary L, et al. A pilot cohort analytic study of Family Integrated Care in a Canadian neonatal intensive care unit. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13 Suppl 1: S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fawole OA, Dy SM, Wilson RF, Lau BD, Martinez KA, Apostol CC, et al. A systematic review of communication quality improvement interventions for patients with advanced and serious illness. J Gen Intern Med 2013, 28(4): 570–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. 2016 strategic plan: exploring the science of complementary and integrative health. 2016. [cited]Available from: https://nccih.nih.gov/sites/nccam.nih.gov/files/NCCIH_2016_Strategic_Plan.pdf

- 36.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report 2008(12): 1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burke S. Systematic review of developmental care interventions in the neonatal intensive care unit since 2006. J Child Health Care 2018: 1367493517753085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conde-Agudelo A, Diaz-Rossello JL. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016(8): Cd002771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clarke-Pounder JP, Boss RD, Roter DL, Hutton N, Larson S, Donohue PK. Communication intervention in the neonatal intensive care unit: can it backfire? J Palliat Med 2015, 18(2): 157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaw RJ, St John N, Lilo E, Jo B, Benitz W, Stevenson DK, et al. Prevention of traumatic stress in mothers of preterms: 6-month outcomes. Pediatrics 2014, 134(2): e481–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaw RJ, St John N, Lilo EA, Jo B, Benitz W, Stevenson DK, et al. Prevention of traumatic stress in mothers with preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2013, 132(4): e886–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hynan MT, Steinberg Z, Baker L, Cicco R, Geller PA, Lassen S, et al. Recommendations for mental health professionals in the NICU. J Perinatol 2015, 35 Suppl 1: S14–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yogman M, Garfield CF. Fathers’ roles in the care and development of their children: the role of pediatricians. Pediatrics 2016, 138(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.