Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Frontotemporal-dementia disorders (FTDs) are heterogeneous phenotypical behavioral and language disorders usually associated with frontal and/or temporal lobe degeneration. We investigated their incidence in a population-based cohort.

METHODS

Using a records-linkage system, we identified all patients with a diagnostic code for dementia in Olmsted County, MN, 1995–2010, and confirmed the diagnosis of FTD. A behavioral neurologist verified the clinical diagnosis and determined phenotypes.

RESULTS

We identified 35 FTDs cases. Overall, the incidence of FTDs was 4.3/100,000/year (95% CI 2.9, 5.7). Incidence was higher in men (6.3/100,000, 95% CI 3.6, 9.0) than women (2.9/100,000; 95% CI 1.3, 4.5); we observed an increased trend over time (B= 0.83, 95% CI 0.54, 1.11, P<0.001). At autopsy, clinical diagnosis was confirmed in eight (72.7%) cases.

DISCUSSION

We observed an increased incidence and trends of FTDs over time. This may reflect a better recognition by clinicians and improvement of clinical criteria and diagnostic tools.

Keywords: Frontotemporal-dementia disorders (FTDs), population-based cohort, neurodegenerative dementia

Introduction

Frontotemporal degeneration disorders (FTDs) are heterogeneous clinical syndromes characterized by behavioral changes, executive dysfunctions, and decline in language skills and are usually associated with degeneration of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain [1]. The term FTDs is used to refer to a group of clinical subtypes that can be distinguished on the basis of the first-occurring and most predominant features: behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD), characterized by marked personality changes, along with disinhibition and apathy; semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA), characterized by fluent anomic aphasia and impaired comprehension of word meaning; and non-fluent agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia (agPPA), characterized by non-fluent agrammatic and hesitant speech along with language and motor speech impairments [2, 3]. Moreover, FTDs show significant overlap with Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) and Corticobasal Syndrome (CBS), both originally described as movement disorders [4–6]. Motor neuron diseases can co-occur with any of the several FTD variants, more frequently with bvFTD [7].

FTDs are the third most common form of neurodegenerative dementia after Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) in most series [8, 9]. Although FTDs are primarily sporadic, genetic forms account for 10–40% of cases [10–12]. FTDs typically present during the sixth decade, [13–15] with a median survival of 3–4 years after diagnosis [15, 16]. The incidence of FTDs has been reported to be 3.5/100,000 person-years in individuals 45 to 64 years of age in Cambridge, UK [17]. Similarly, a previous study from Rochester, MN, reported an incidence of 3.3/100,000 person-years in the 50–59-year age group [18]. Although FTDs are generally considered to be a cause of early-onset dementia [14], they can also present in older adults. Patients over 65 years old account for 20–25% of the cases[14, 15], and the incidence may increase with age [19]. The aim of this study was to assess the incidence and the trend of FTDs in our population-based cohort study in Olmsted County, MN, from 1995 to 2010 and to examine the clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients.

Methods

Case Ascertainment

We ascertained all new cases of dementia in Olmsted County, MN, from 1995 through 2010 using the medical records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). The REP provides the infrastructure for storing and linking all medical information for the county population [20–22]. We ascertained potential cases of FTD in two phases. First, we used a computerized screening and searched for 24 dementia codes including five Hospital Adaptation of the International Classification of Diseases (H-ICDA) codes, 14 International Classification of Diseases −9th revision (ICD-9) codes, and five ICD-10 (10th revision) codes (Appendix Table A.1.). This list of 24 codes was designed to yield maximum sensitivity and be as inclusive as possible in the first stage of identification of patients. We classified these codes into two groups: priority one and priority two codes (Appendix Table A.1). Priority-1codes were designed to yield the highest specificity for FTDs, whereas Priority-2 codes were designed to have the highest sensitivity in order to capture all forms of dementias not otherwise specified. Among the patients who had at least one Priority-2 diagnostic code, we used natural language processing (NPL) to confirm the presence of diagnoses consistent with FTDs in the medical records by using specific keywords (Appendix Table A. 2). In phase two, a behavioral neurologist (R.S.) reviewed all the clinical records to confirm the clinical diagnosis of FTDs and determine the specific subtype and characteristics according to current diagnostic criteria [2, 3]. In addition, we reviewed all those cases that were not primarily diagnosed by a neurologist (nine by a psychiatrist, one by an internal medicine physician) and confirmed the clinical diagnoses. We excluded all those cases whose diagnoses were not supported by a neuropsychological assessment or neuroimaging confirmation. To capture the incident cases, we extended the search for 5 years after the incidence study period (January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2015) to ensure that persons with a delayed diagnosis could be counted correctly. The behavioral neurology specialist defined the approximate date of diagnosis and the type of FTDs according to the current clinical criteria [2, 3, 23]. Thus, we divided our bvFTD cases into clinically “possible” or “probable” FTD cases (Table 1). Based on the information present in their clinical records, 7/12 patients who originally received a generic diagnosis of FTD met the criteria for bvFTD (either possible or probable). It was not possible to retrieve enough information to further classify the remaining five patients into a specific variant; therefore, they were defined as unspecified FTD cases (Table 1). For the purpose of this manuscript, PSP and CBS were not included in the analysis because of the different pattern of phenotypical characteristics and pathological findings that overlap with some movement disorders. Medical records were also reviewed for autopsy information conducted and interpreted by a board-certified neuropathologist. The Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards approved this study, and participating patients (or their legally authorized representatives) provided informed written consent for use of their medical information.

Table 1 bis.

Clinical characteristics of the three patients clinically diagnosed with PPA based on the speech pathology reports.

| Patient # | Clinical Dx | Agrammatism | Apraxia of speech | Impaired comprehension | Impaired naming | Impaired object knowledge | paraphasia | Speech rate impaired | Impaired repetition | Aphasia | Dyscalculia | Dysgraphia | Autopsy | Source of Dx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | agPPA | + | N/A | + | + | + | N/A | N/A | + | + | + | - | - | Neurologist |

| #2 | PPA NOS | N/A | - | + | - | - | N/A | N/A | + | + | + | + | - | Neurologist |

| #3 | svPPA | N/A | - | N/A | + | + | + | N/A | N/A | + | N/A | N/A | FTLD-U | Neurologist |

PPA, Primary progressive aphasia; agPPA, agrammatic primary progressive aphasia; NOS, Not otherwise specified; svPPA, semantic vatriant primary progressive aphasia; N/A, not available.

Statistical analysis

All individuals who were diagnosed with and met clinical criteria for FTD disorders between 1995 and 2010 were considered as incident cases in the incidence-rate calculation. The person-years-at-risk denominator was estimated from the Rochester Epidemiology Project Census data. Incidence rates were estimated as the number of new cases divided by the person-years at risk. Further, incidence rates were directly standardized by age and sex. We used survey-weighted linear-regression models specifying year as an independent variable to estimate incidence trends. Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted to model survival time. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and RStudio version 3.4.2.

Results

Demographics

We identified 1061 individuals with at least one screening code of interest from 1995 through 2010.

Among these, 148 patients received a Priority-1 diagnostic code; whereas 913 a Priority-2 code (Table A.1). We reviewed the clinical records of the 148 patients who received a Priority-1diagnostic code: 35 (23.6%) cases met updated clinical criteria and were found to have a clinical diagnosis of FTDs. We used NPL to review the records of the 913 patients with a Priority-2 diagnostic code, and found 20 patients with a mention of FTDs in their clinical records. R.S. reviewed these 20 patients to assess the possibility that they were diagnosed with FTDs related disorders. To further increase accuracy, a behavioral neurologist examined a random sample of 100 patients from the list of 913 Priority-2 codes and reviewed their clinical records – none of them received a clinical diagnosis of FTDs nor had features strongly suspicious for the FTDs. In addition, as per our methods of accuracy, we included only those cases that received a neuropsychological assessment and/or a neuroimaging evaluation (MRI, CT, PET, SPECT).

Among the 35 patients who received a clinical diagnosis of FTDs, 22 (62.9%) were male. Median age at diagnosis was 70 years (range: 48–94). Median follow-up time after diagnosis was three years (range: 1 month-12 years). Twenty-six (74.3%) had a clinical diagnosis of bvFTD; one semantic PPA; one agrammatic PPA; and 1 PPA not otherwise specified. We also observed a case of FTD with motor neuron disease (FTD-MND) who died after three months. Although they all received clinical diagnoses of FTD, a specific variant was not possible to be defined for five (14.3%) cases based on the information in their clinical records, and they were classified as unspecified (Table 1).

Roughly one-third (10/35) of cases reported depression within five years preceding the diagnosis of FTDs. One patient underwent microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) screening, which did not identify any pathological mutations, whereas one patient clinically diagnosed with bvFTD tested positive for progranulin (GRN) mutation.

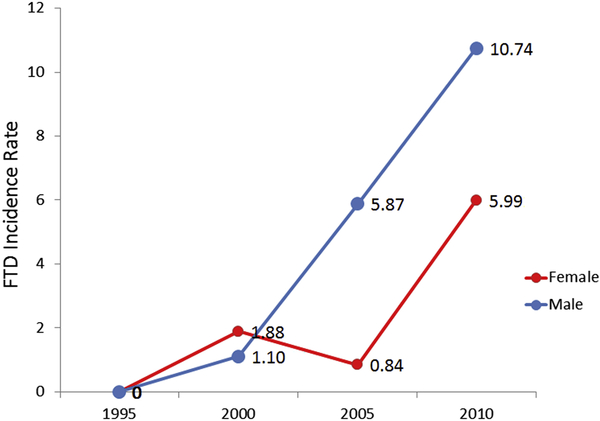

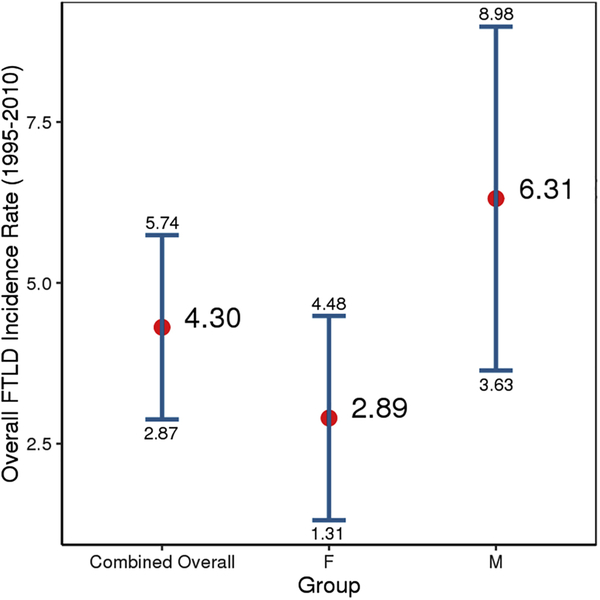

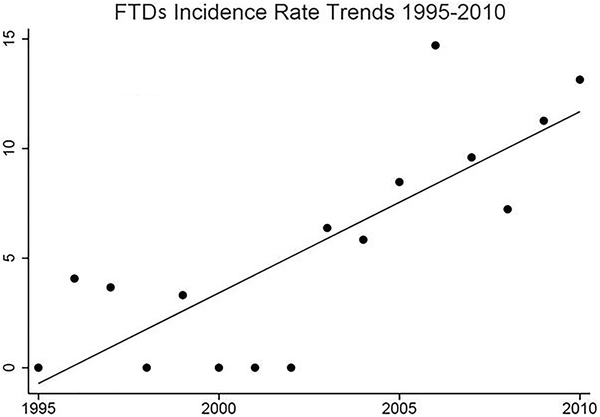

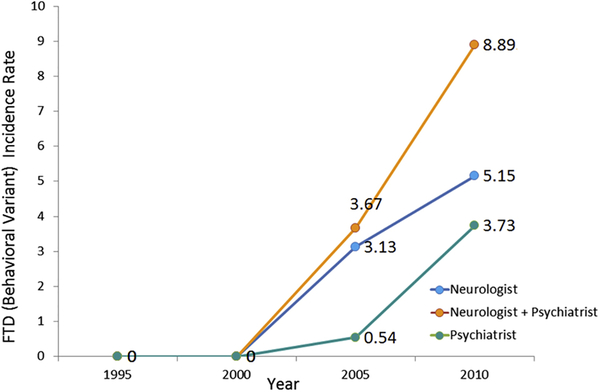

Incidence, trending analysis and survival

Figure 1 shows sex-specific incidence rates for FTDs from 1995 to 2010, then in four consecutive five-year time periods. The overall incidence of FTDs in Olmsted County, MN, was 4.3/100,000 person-years (95% CI 2.9, 5.7); incidence was higher in men (6.3/100,000, 95% CI 3.6, 9.0) than women (2.9/100,000; 95% CI 1.3, 4.5) (FIGURE 2). There was a trend for an increased FTDs incidence between 1995 and 2010 (B= 0.83, 95% CI 0.54, 1.11, P<0.001) (Figure 1). To further characterize our results, we focused on our 26 bvFTD cases and divided them based on the specialist who provided the clinical diagnosis (either a behavioral neurologist or a psychiatrist). In Figure 2, we report the overall incidence of bvFTD, the incidence only for the 17/26 bvFTD cases diagnosed by a neurologist (referred to as “strict” cases), and the incidence only for those 9 bvFTD diagnosed by a psychiatrist (referred to as “lenient” cases). Further we reported the incidence of FTDs based on the specific variants (Figure 3). We also compared the incidence of probable FTD and possible FTD and we did not find a difference between these two diagnostic categories (X2 = 1.19, p = 0.27). In addition to the incidence rates reported above, we have also included a detailed breakdown of these incidence rates by age, year and other subgroups in the accompanying appendix. Also we wish to emphasize to our readers that, in some cases, slight differences in the denominator person years is due to these values having been adjusted by age and sex for different subcategories. Median survival among FTD patients was 3 years from diagnosis (range: 3 months-15 years); bvFTD was associated with a median survival of 7 years from diagnosis (range: 7 months-15 years). As shown in the Kaplan-Meier plot (Figure 4), approximately 50% of all FTDs patients died within 3 years from the diagnosis and 95% after 10 years.

Figure 1.

Sex-specific Incidence rates of FTDs in Olmsted County, MN, from 1995 to 2010.

Figure 2.

Overall sex specific incidence rates of FTDs in Olmsted County, MN, from 1995–2010.

Figure 3.

FTDs trending analysis from 1995 to 2010.

Figure 4.

Incidence rates for bvFTD in Olmsted County, MN, from 1995–2010 based on the specialist who provided the clinical diagnosis.

Neuroimaging and Post-mortem examinations

In 14 patients (40.0%), at least one MRI was performed (range: from 3 days to 6 years before the diagnosis); all of them showed either generalized atrophy or prominent frontal and temporal cortical atrophy. Six patients (17.1%) underwent either FDG-PET or SPECT scans before the clinical diagnosis (range: 1 month to 19 months) – all of them showed cortical hypometabolism or hypoperfusion in the frontal, temporal, and/or parietal lobes consistent with a diagnosis of FTD. Most (30/32, 93.4%) FTD patients had either an MRI or CT scan performed after the clinical diagnosis was made, and a characteristic pattern of atrophy was observed in 26 (86.7%) of them. Twelve cases underwent either FDG-PET or SPECT scans after the clinical diagnosis was made with a classic pattern of hypometabolism/hypoperfusion observed in 11/12 (91.7%). Eleven patients (31.4%) underwent brain autopsy; all were classified according to the CERAD, Braak, and NIA/Reagan criteria. We calculated the incidence rate for pathologically confirmed cases (11 cases: incidence 1.3837; C.I 0.5625 − 2.2049) and for non-pathologically confirmed cases (24 cases: incidence 2.9537; C.I 1.7693 − 4.1381). A Chi-Square based test comparing the difference between these two rates (pathology-confirmed vs not pathology- confirmed) showed marginal significance (X2 = 4.5; p= 0.03), showing marginal significant difference.

Eight (72.7%) showed pathological findings consistent with the clinical diagnosis including one patient with a pathological diagnosis of CBD, one with a diagnosis of argyrophilic grain disease and one with a pathological diagnosis of primary age-related tauopathy. Transactive-response DNA- binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43) inclusions were present in four of these eight patients. Two patients had mixed pathological findings consistent with AD and LBD, including one who also showed TDP-43 positive inclusions, and two had a pathological diagnosis of AD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of all the patients with a clinical diagnosis of FTD.

| Clinical Dx | Behavioral disinhibition | Apathy or inertia | Loss of sympathy or empathy | Perseverative/stereotyped behavior | Hyperorality/dietary changes | Functional decline | MRI/CT performed | Frontal and/or temporal atrophy | PET/SPECT performed | Frontal and/or hypoperfusion | Autopsy | Pathological Dx | Source of diagnosis | Possible bvFTD | Probable bvFTD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bvFTD | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | FTLD-TDP+AD+LBD | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | PART | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | Argyrophilic Grain disease | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | P | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | CBD | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | AD+LBD | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | FTLD-TDP | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | P | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | FTLD-TDP | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | P | + | |

| bvFTD | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | AD | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | FTLD-U | N | + | |

| bvFTD | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | P | + | |

| bvFTD | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | P | + | |

| bvFTD* | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | N | + | |

| bvFTD* | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | P | + | |

| bvFTD* | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | P | + | |

| bvFTD* | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | P | + | |

| bvFTD* | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | N | + | |

| bvFTD* | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | P | + | |

| bvFTD* | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | N | + | |

| FTD-MND | + | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | N | ||

| FTD NOS | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | N | ||

| FTD NOS | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | AD+LBD | P | ||

| FTD NOS | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | IM | ||

| FTD NOS | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | N | ||

| FTD NOS | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | N |

Dx, diagnosis; bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; FTD NOS, frontotemporal dementia not otherwise specified; FTD-MND, frontotemporal dementia with motor neuron disease; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; LBD, Lewy body disease; PART, primary age-related tauopathy; CBD, corticobasal degeneration; FTLD, frontemporal lobar degeneration; N, neurologist; P, Psychiatrist;, IM, Internal Medicin Physician; TDP, Transactive response DNA binding protein 43 kDa; U, Ubiquitin; bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia

patients originally considered as unspecified FTD cases who underwent further classification.

Discussion

We observed an overall incidence of FTDs of 4.3/100,000 person-years, which is consistent with an earlier study from Rochester, MN, reporting an overall incidence of 4.1/100,000 person-years in a population aged 40–69 years [18]. Our incidence rate is higher than a recent UK Study (incidence of 3.5/100,000 person-years) [17]; however, the difference can be attributable to a slightly higher median age at diagnosis. We suspect that FTDs might be underreported, and their impact on the general population might be higher than previously thought. FTDs are usually considered a cause of early-onset dementia, although studies have proven that the incidence of FTDs increases with age [24]. Experienced clinicians and updated diagnostic tools are required to accurately diagnose these disorders; FTDs, in fact, often overlap with other neurodegenerative disorders such as AD [25] or movement disorders [4–6]; the presence of a frontal variant of AD makes it even more challenging to appropriately diagnose FTDs [26], especially in light of the aging of the population. This may impact not only the results of epidemiological studies, which may underreport the incidence and prevalence of FTDs but, most importantly, the management and the outcomes of the patients. Over the last 10 years of our period of interest, specifically after 2002, we observed a sharp increase in the incidence of FTDs for both men and women. We hypothesize this trend is mainly driven by an increased awareness of the syndrome by clinicians and by better definition of clinical criteria [27]. When we focused on the specific FTD variants, we observed an increased incidence for bvFTD over time, whereas the incidence of PPA remained relatively stable. In addition, more advanced neuroimaging tools might also explain our results, rather than a true increase in the incidence of these disorders in the population. Nonetheless, we estimated an increased incidence of FTDs of 0.83/100,000 cases per year.

Overall, our observed FTDs survival time of three years from diagnosis was consistent with other studies showing a median survival of 3–4 years after diagnosis [15, 16]. Patients with FTD-MND have the shortest survival among FTDs [15, 28]. Although our cohort had only one patient diagnosed with FTD-MND, the survival after diagnosis was only three months, further supporting the malignancy of this variant disease. Notably, we calculated the survival time starting from the diagnosis date rather than from the date of symptom onset; indeed, this might be more reliable because FTDs symptoms, especially behavioral changes, can be extremely vague during the first stages of the disease and can be misdiagnosed and confused with other psychiatric conditions [29]. Nonetheless, almost 30% of our patients showed depressive symptoms within 5 years before the clinical diagnosis of FTDs.

Up to 40% of FTD cases are associated with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance. In our cohort, only two patients underwent genetic testing for FTD; one tested negative for a mutation of the MAPT gene, whereas the second one tested positive for a mutation of the GRN gene. Although a mutation of the C9orf72 gene is considered as the single most common mutation in familial FTD cases, the link between C9orf72 gene mutations and FTD was not reported until 2011 [30], one year beyond our timeperiod; thus we could not examine the association.

Neuroimaging studies have been used extensively, both to support physician hypotheses and strengthen their clinical diagnoses. Atrophy and hypometabolism/hypoperfusion predominantly of the frontal and temporal cortex are the clinical hallmark of FTDs [2], with characteristic patterns of atrophy identified in the different variants [31]. Our study showed that brain atrophy on MRI and/or a pathologic hypometabolism/hypoperfusion on PET/SPECT scans is observed up to six years before the clinical diagnosis, further supporting the importance of imaging studies, even in the early phases of the disease. However, these results should be interpreted with caution because some FTDs cases, especially bvFTD patients, may not show any atrophy on MRI or FDG-PET changes despite presenting the classic clinical features (referred to as “bvFTD phenocopy syndromes”) [32–34]. Furthermore, the presence of frontal atrophy can be sometimes also seen in unaffected controls [35]. Unfortunately, we did not have neuroimaging studies available in the entire cohort, and furthermore, based upon the decision of the clinicians, the imaging studies were not repeated systematically and consistently. Thus, our neuroimaging results should be interpreted with caution.

Neuropathological characterization of FTDs is challenging because a variety of possible underlying pathology findings can be observed at autopsy [36]. Eight of the eleven autopsied cases in our cohort showed pathological findings consistent with the clinical diagnosis, and TDP-43 was present in four of these eight patients. All three discordant cases showed pathological findings consistent with frontal variant AD [26, 37]. Mixed AD pathology and Lewy bodies were observed in two of these cases, with clear parkinsonian symptoms present in only one of the two (Table 3). Consistent with our study, up to 30% of patients clinically diagnosed with FTD show AD pathology [1, 38]. The overlap between FTDs and AD is not surprising because AD pathology may also be observed in non-demented elderly patients [39].

Table 3.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the FTDs patients in our cohort.

| Clinical Dx | Pathological Dx | TDP-43 | Braak stage (I-VI) | CERAD score | NIA-Reagan criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bvFTD | FTLD-TDP43+AD+LBD | + | V | C | High likelihood |

| FTD NOS | AD+ LBD(limbic) | - | II | N/A | Low likelihood |

| bvFTD | PART | - | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| bvFTD | Argyrophilic grain disease | - | II | C | Low Likelihood |

| bvFTD | CBD | - | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| bvFTD | AD | N/A | VI | C | High Likelihood |

| bvFTD | FTLD-TDP43 | + | N/A | Possible | N/A |

| bvFTD | FTLD-TDP43 | + | None | A | Not likely |

| bvFTD | AD | - | V | N/A | N/A |

| svPPA | FTLD-U | + | I-II | Normal | Low likelihood |

| bvFTD | FTLD-U | - | N/A | N/A | N/A |

bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; NOS, not-otherwise specified; svPPA, semantic variant primary progressive aphasia; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; LBD, Lewy Body dementia; PART, Primary Age-Related Tauoptahy; CBD, corticobasal degeneration; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration;TDP-43, transactive response DNA binding protein 43 kDa; U, ubiquitin; Dx, diagnosis; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; NIA, National Institute of Aging; N/A; not available.

Our study has several strengths. First, we utilized the medical records-linkage system of the REP that provides the infrastructure for storing and linking all medical information of the population of Olmsted County. Second, all the medical records were reviewed by a behavioral neurologist (R.S.) to confirm the final diagnosis and the presence of FTDs. Third, the standardized codes used to screen the Olmsted County population allowed us to detect all the incident cases of FTDs in the County during the time period of interest.

This study has also limitations. First, the information in the medical records was recorded as part of the routine clinical practice and was not standardized for research. Second, some FTDs cases might have been missed due to their rarity and difficulty to diagnose; therefore, our incidence rates might be an underestimation of the true FTDs occurrence. However, our data collection spanned 15 years; in addition, we collected data for five more years (2010–2015), in order to identify additional cases diagnosed in the study period. Third, since FTDs share symptoms with other psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders, some cases might have been misdiagnosed. Fourth, we did not calculate age-specific incidence rates due to the relatively small sample size of our cohort. Fifth, it was not possible to further define the FTD variant in five patients who received a clinical diagnosis of FTD despite the records that confirmed their diagnoses. Moreover, to further strengthen our results, we analyzed their incidence separately to exclude the possibility that the results were driven by this group of undefined FTDs. Fifth, we had limited information on the pathology confirmation. Only 11 cases underwent autopsy; thus, we could not estimate specificity and sensitivity of our clinicpathology concordance. However, we adopted the most updated criteria to define possible and probable bvFTD. In addition, the relatively small number of pathology-confirmed case prevent us from exploring the frequency of the different proteinopathies involved in FTDs.

In conclusion, FTDs are still a leading cause of dementia. The increased incidence rate we reported might be secondary to major diagnostic advances and awareness in the last decades in the field. The presence of clinical findings shared with other neurodegenerative diseases, along with the broad range of underlying pathological features present in FTDs, emphasizes the importance of the future development of reliable biomarkers that can predict the diagnosis, improve the management, and better the quality of life of patients.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

We conducted a comprehensive literature search among PubMed, Ovid Medline and Google Scholar from database inception. We also searched for systematic reviews to find additional articles on this topic.

INTERPRETATION

Although FTDs are the third most common form of neurodegenerative dementia, few epidemiological studies focused on this topic. The current knowledge on the epidemiology and on the impact of these disorders on the population is limited. The unique infrastructure of the Rochester Epidemiology Project and the geographic characteristics of Olmsted County, MN allow us to conduct epidemiological studies that have a major impact on the medical practice.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The increased incidence rate we reported along with the burden that a diagnosis of FTDs brings with, emphasize the importance of research studies focused on the early stages of disease, aiming to find possible risk factors and reliable biomarkers to better patients’ quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lea Dacy for proof-reading and formatting assistance.

Funding: This study was supported by award R01 AG034676 from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health and by the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of Interest: Dr. Turcano and Messrs. Stang, Martin, and Upadhyaya, none. Dr. Mielke receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, and unrestricted research grants from Biogen and Lundbeck; she has consulted for Lysosomal Therapeutics, Inc, and Eli Lilly. Dr. Josephs receives funding from the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Boeve receives funding from the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Lewy Body Dementia Association, GE Healthcare, Axovant Sciences, Inc., and Biogen. Dr. Knopman served as a consultant to TauRx Pharmaceuticals ending in November 2012. Dr. Petersen reports grants from National Institute on Aging, during the conduct of the study; grants from National Institute on Aging, grants from Department of Defense, grants from Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics, grants from PCORI, grants and other from Alzheimer’s Association, grants from Abbott Laboratories, other from Dana Alliance for Brain Initiatives, other from Northwestern University, Alzheimer’s Disease Center External Advisory Committee, other from Advisory Council on Research Care and Services, National Alzheimer’s Project Act, other from French Foundation on Alzheimer’s Disease, Scientific Steering Committee, French Ministry of Research, other from World Dementia Council, outside the submitted work; and Editorial Board Member of the following journals: Alzheimer’s & Dementia; Alzheimer’s Disease & Associated Disorders: An International Journal; Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. Dr. Savica receives funding from the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Parkinson ‘s Disease Foundation, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Rabinovici GD, Miller BL, Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management, CNS Drugs 2010;24:375–398. 10.2165/11533100-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH, Neuhaus J, et al. , Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, Brain 2011;134:2456–2477. 10.1093/brain/awr179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. , Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants, Neurology 2011;76:1006–1014. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kertesz A, McMonagle P, Jesso S, Extrapyramidal syndromes in frontotemporal degeneration, J Mol Neurosci 2011;45:336–342. 10.1007/s12031-011-9616-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kertesz A, Martinez-Lage P, Davidson W, Munoz DG, The corticobasal degeneration syndrome overlaps progressive aphasia and frontotemporal dementia, Neurology 2000;55:1368–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Boeve BF, Lang AE, Litvan I, Corticobasal degeneration and its relationship to progressive supranuclear palsy and frontotemporal dementia, Ann Neurol 2003;54 Suppl 5:S15–19. 10.1002/ana.10570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lomen-Hoerth C, Characterization of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia, Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004;17:337–341. 10.1159/000077167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vieira RT, Caixeta L, Machado S, Silva AC, Nardi AE, Arias-Carrion O, et al. , Epidemiology of early-onset dementia: a review of the literature, Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2013;9:88–95. 10.2174/1745017901309010088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bang J, Spina S, Miller BL, Frontotemporal dementia, Lancet 2015;386:1672–1682. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00461-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Seelaar H, Kamphorst W, Rosso SM, Azmani A, Masdjedi R, de Koning I, et al. , Distinct genetic forms of frontotemporal dementia, Neurology 2008;71:1220–1226. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319702.37497.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Paulson HL, Igo I, Genetics of dementia, Semin Neurol 2011;31:449–460. 10.1055/s-0031-1299784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Finger EC, Frontotemporal Dementias, Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22:464–489. 10.1212/CON.0000000000000300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Johnson JK, Diehl J, Mendez MF, Neuhaus J, Shapira JS, Forman M, et al. , Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: demographic characteristics of 353 patients, Arch Neurol 2005;62:925–930. 10.1001/archneur.62.6.925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR, The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia, Neurology 2002;58:1615–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hodges JR, Davies R, Xuereb J, Kril J, Halliday G, Survival in frontotemporal dementia, Neurology 2003;61:349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Roberson ED, Hesse JH, Rose KD, Slama H, Johnson JK, Yaffe K, et al. , Frontotemporal dementia progresses to death faster than Alzheimer disease, Neurology 2005;65:719–725. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173837.82820.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mercy L, Hodges JR, Dawson K, Barker RA, Brayne C, Incidence of early-onset dementias in Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom, Neurology 2008;71:1496–1499. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334277.16896.fa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Edland SD, Cha RH, Rocca WA, The incidence of frontotemporal lobar degeneration in Rochester, Minnesota, 1990 through 1994, Neurology 2004;62:506–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Garre-Olmo J, Genis Batlle D, del Mar Fernandez M, Marquez Daniel F, de Eugenio Huelamo R, Casadevall T, et al. , Incidence and subtypes of early-onset dementia in a geographically defined general population, Neurology 2010;75:1249–1255. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f5d4c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3rd, Rocca WA, Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project, Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3rd, Rocca WA, Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester epidemiology project, Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:1059–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd, History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population, Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:1202–1213. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Savica R, Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA, Incidence and pathology of synucleinopathies and tauopathies related to parkinsonism, JAMA Neurol 2013;70:859–866. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nilsson C, Landqvist Waldo M, Nilsson K, Santillo A, Vestberg S, Age-related incidence and family history in frontotemporal dementia: data from the Swedish Dementia Registry, PLoS One 2014;9:e94901 10.1371/journal.pone.0094901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Alladi S, Xuereb J, Bak T, Nestor P, Knibb J, Patterson K, et al. , Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease, Brain 2007;130:2636–2645. 10.1093/brain/awm213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Johnson JK, Head E, Kim R, Starr A, Cotman CW, Clinical and pathological evidence for a frontal variant of Alzheimer disease, Arch Neurol 1999;56:1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, et al. , Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria, Neurology 1998;51:1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Coon EA, Sorenson EJ, Whitwell JL, Knopman DS, Josephs KA, Predicting survival in frontotemporal dementia with motor neuron disease, Neurology 2011;76:1886–1893. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821d767b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Woolley JD, Khan BK, Murthy NK, Miller BL, Rankin KP, The diagnostic challenge of psychiatric symptoms in neurodegenerative disease: rates of and risk factors for prior psychiatric diagnosis in patients with early neurodegenerative disease, J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:126–133. 10.4088/JCP.10m06382oli [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, et al. , Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS, Neuron 2011;72:245–256. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, Recent advances in the imaging of frontotemporal dementia, Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2012;12:715–723. 10.1007/s11910-012-0317-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Davies RR, Kipps CM, Mitchell J, Kril JJ, Halliday GM, Hodges JR, Progression in frontotemporal dementia: identifying a benign behavioral variant by magnetic resonance imaging, Arch Neurol 2006;63:1627–1631. 10.1001/archneur.63.11.1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kipps CM, Davies RR, Mitchell J, Kril JJ, Halliday GM, Hodges JR, Clinical significance of lobar atrophy in frontotemporal dementia: application of an MRI visual rating scale, Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007;23:334–342. 10.1159/000100973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kipps CM, Hodges JR, Fryer TD, Nestor PJ, Combined magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography brain imaging in behavioural variant frontotemporal degeneration: refining the clinical phenotype, Brain 2009;132:2566–2578. 10.1093/brain/awp077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chow TW, Binns MA, Freedman M, Stuss DT, Ramirez J, Scott CJ, et al. , Overlap in frontotemporal atrophy between normal aging and patients with frontotemporal dementias, Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2008;22:327–335. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31818026c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kertesz A, McMonagle P, Blair M, Davidson W, Munoz DG, The evolution and pathology of frontotemporal dementia, Brain 2005;128:1996–2005. 10.1093/brain/awh598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Woodward M, Jacova C, Black SE, Kertesz A, Mackenzie IR, Feldman H, et al. , Differentiating the frontal variant of Alzheimer’s disease, Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010;25:732–738. 10.1002/gps.2415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Forman MS, Farmer J, Johnson JK, Clark CM, Arnold SE, Coslett HB, et al. , Frontotemporal dementia: clinicopathological correlations, Ann Neurol 2006;59:952–962. 10.1002/ana.20873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, Floriach-Robert M, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, et al. , Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly, J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2003;62:1087–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.