Abstract

Immunological memory is defined by the ability of the host to recognise and mount a robust secondary response against a previously encountered pathogen. Classic immune memory is an evolutionary adaptation of the vertebrate immune system that has been attributed to adaptive lymphocytes, including T and B cells. In contrast, the innate immune system was known for its conserved, non-specific roles in rapid host defence, but historically was considered to be unable to generate memory. Recent studies have challenged our understanding of innate immunity and now provide a growing body of evidence for innate immune memory. However, in many species and in various cell types the underlying mechanisms of immune memory formation remain poorly understood. The purpose of this review is to explore and summarize the emerging evidence for immunological “memory” in plants, invertebrates, and vertebrates.

Keywords: innate immune memory

Introduction

Innate immunity is characterised by the rapid and non-specific responses to invading pathogens, including phagocytosis of pathogens and cell debris, as well as the production of immune modulatory factors (e.g. cytokines and chemokines). Innate immunity is carried out by cells thought to be short-lived, including monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, granulocytes and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs; including natural killer (NK) cells). In contrast, immunological “memory” is a feature of the adaptive immune system’s ability to specifically recognise and respond to encountered pathogens. Although “memory” is traditionally ascribed to antigen-specific T and B cells, in recent years members of the innate immune response have been shown to acquire anamnestic qualities. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that immune “memory” is not restricted to mammals. Lower vertebrates, invertebrates, and even plants have been reported to demonstrate features of memory and recall responses following multiple exposures to pathogens.

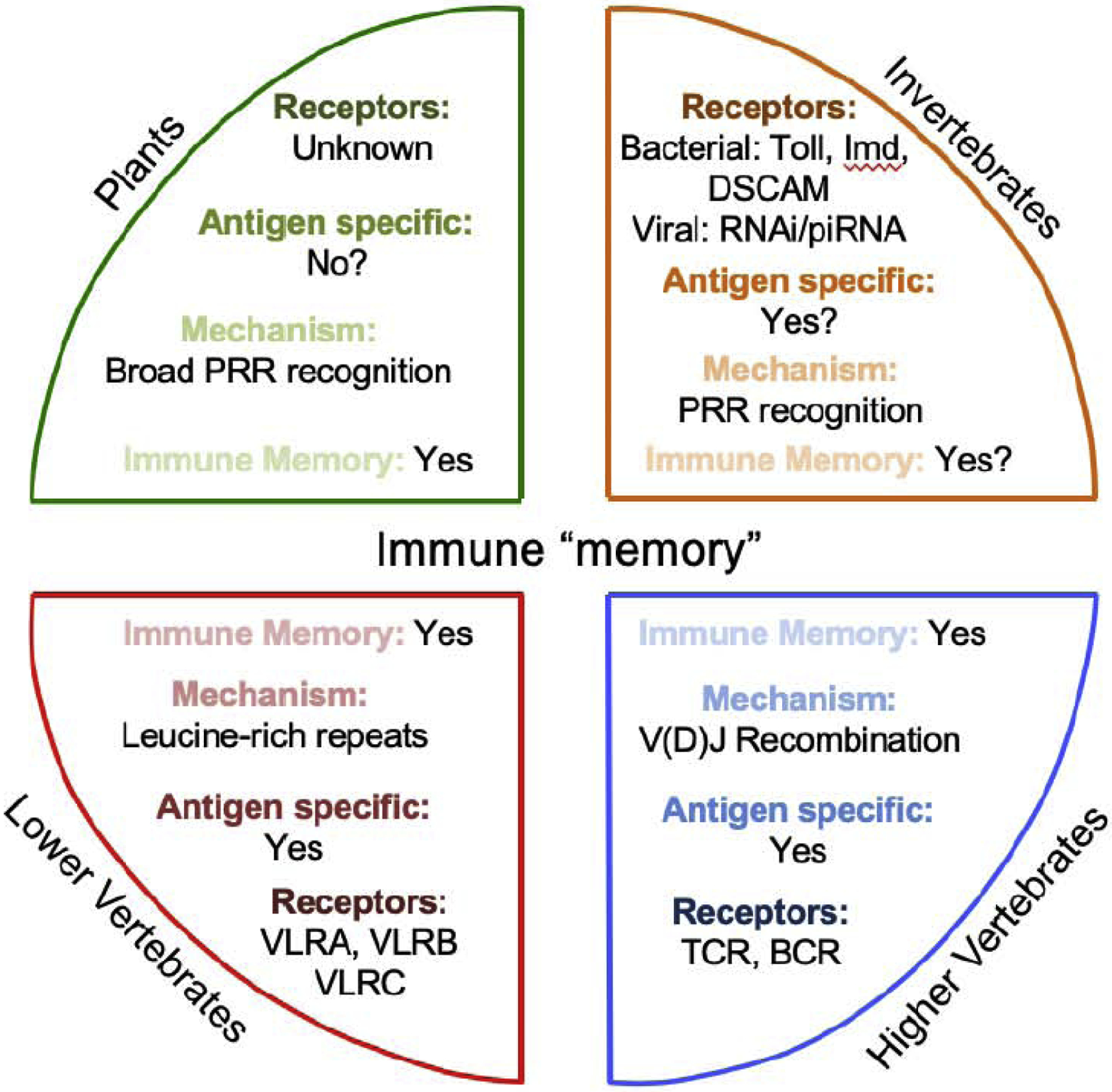

Extensive research over the past decade has broadened our understanding of immunological memory. Recent studies have challenged the ‘textbook’ definition of immune memory, and we have only just begun to uncover the evolutionary depths of these immune functions [1,2]. In this review, we highlight the evolutionary conservation of innate immunological memory functions that have been observed in plants, invertebrates, and vertebrates, and describe common mechanisms governing how organisms protect themselves from repeated exposure to pathogens and efficiently fight off these infections (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Antigen specificity and memory from plants to higher vertebrates.

Evidence suggests plants are able to form immune memory via broad PRR recognition but antigen specific diversity may not be present. Invertebrates, including insects, worms, crustaceans, much like plants rely solely on innate immune responses and antigen specificity may be limited but evidence suggests many species are able to develop some form of immune memory. Lower vertebrates, such as jawless fish (lamprey and hagfish), VLRs and leucine-rich repeats may represent a primitive form of adaptive immunity. In higher vertebrates (from jawed fish to mammals) antigen specificity and immune memory is mediated by immune cells with an ability to rearrange antigen receptors. PRR, pattern recognition receptor; DSCAM, Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule; RNAi, RNA interference; piRNA, Piwi-interacting RNA; VLR, variable lymphocyte region; V(D)J recombination, random combination of variable, diverse and joining gene segments in lymphocytes; TCR; T-cell receptor, BCR; B-cell receptor.

Immune memory in plants

Immunity in plants comprises both local and systemic responses for protection against pathogens. Unlike animals, plants did not evolve motile immune cells or develop an adaptive immune system, yet constitute one of the oldest living organisms on the planet. Plants have been found to mount multilayered immune responses comprised of both constitutive and inducible defence components, and can launch specific, self-tolerant immune responses. Plants rely on physical barriers (plant cell walls), antibiotic compounds (e.g. phytoalexins) and enzymes to perturb pathogens, and they can respond to infection using a dual-branched innate immune system. The first branch recognises and responds to molecules common to many microbes, including those that are non-pathogenic; and the second branch responds to virulence factors of pathogens [3]. Thus, plants have the capacity to establish a form of immune “memory” or “priming” following pathogen exposure.

Defence priming in plants was first described in the early 1930s, where the idea of inducible immunity was proposed [4]. However, it wasn’t until the 1980s that evidence emerged for the process of defence priming in various types of induced plant immunity [5]. In these experiments, plants, including cucumber, watermelon, muskmelon, and tobacco, were immunized with a small dose of either broad-spectrum fungi (Colletotrichum lagenarium), bacteria (Pseudomonas syringae) or virus (tobacco mosaic virus, TMV) and demonstrated protection against numerous diseases, suggesting the memory in plants is not restricted to an individual pathogen. Infections recognised by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in plants have been shown to induce systemic resistance to subsequent challenges with the same or different stimuli, a mechanism referred to as broad-spectrum resistance - a major immune mechanism in plants [reviewed in 6*]. Defence priming in plants has been shown to be consistently activated by treatment with salicylic acid, pipecolic acid (Pip), methyl-jasmonic acid (MeJA), azelaic acid (AzA) and a number of xenobiotics [7]. Field studies have shown that many wild plants display constitutively higher defence priming whereas others can be primed for a heightened response following treatment with natural or synthetic immune stimulants [8,9]. Interestingly, studies showed that the ability to undergo defence priming is dependent on the life cycle of plants and that long-lived perennials show better capacity for immune memory than annual plants [10–12].

Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) is the most well characterised type of plant immunity. It has been demonstrated in many plants and infection settings (reviewed in [13]) and is often described as the prominent form of immunological “memory” in plants. The SAR response to localised foliar infection is associated with increased levels of PRRs, an accumulation of dormant signalling enzymes and modifications within chromatin states [14]. These systemic responses lead to memory formation after an initial infection by priming the leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana (a small flowering plant, related to cabbage and mustard) for enhanced defence and protection against re-infection with Pseudomonas fluoresens [6*]. Studies also showed that A. thaliana defence priming (whether induced locally by inoculation of the leaves with Pseudomonas infection or systemically by spraying with salicylic acid), leads to increased accumulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases 3 and 6 (MPK3/6) mRNA transcript and protein level in all leaves [15]. Furthermore, MPK3/6 are kept inactive in primed cells but can be quickly activated in the case of pathogen re-challenge where more MPK3/6 proteins are activated in primed plants compared to unprimed plants [15].

Interestingly, immune memory of SAR in Arabidopsis can be passed onto the following generation. SAR activation by inoculation with a virulent strain of P. syringae pv tomato leads to heightened resistance to that bacterial species in the F1 generation, as well as resistance to an unrelated infection with the oomycete H. parasitica in the F1 generation [16]. In line with these results, P. syringae pv tomato infection is known to cause hypomethylation in the Arabidopsis thaliana plant [17] and these DNA methylation patterns, which can be transferred from one generation to another, are likely to play a role in the transmission of “memory” associated with SAR [18].

Eukaryotes rely heavily on ATP-dependent remodelling of histones in chromatin to control transcriptional activity. In plants, these events play important roles in organ development and the timing of flowering [19]. In recent years, several groups have shown that histone modifications and chromatin remodelling can influence the transcription of genes involved in immunity and memory [20,21]. Another study demonstrated H3K4me3 was uncoupled from the pathogenesis-related protein 1 (PR1) defence gene transcription in Arabidopsis following dip-inoculation into a bacterial suspension of Pseudomonas syringae and instead associated with permissive states of PR1 transcription suggesting modifications of the chromatin for rapid changes in gene transcription following pathogen encounter [22]. Furthermore, by using O. sativa (the rice plant) during defence priming, it was shown that the promoter of the defence-related transcription factor gene WRKY29 becomes associated with H3K4me3, H3K4me2, H3K9ac, H4K5ac H4K8ac and H4K12ac [23]. However, these histone modifications did not allow for activation of WRKY29 again until the plants were re-challenged with a second infectious pathogen [24]. Together these data suggest chromatin modifications can provide a form of immune memory during defence priming in the systemic plant immune response.

Defence priming and SAR play an important part in the plant immune response against both environmental stresses (e.g. drought and light availability), and pathogenic encounters. In plants, recall responses are associated with modification of histones (and DNA methylation at defence gene promotors), increased amounts of cell signalling enzymes, and an accumulation of PRRs at cell membranes. The ability for the plant immune system to build immunological memory suggests a conservation, or convergence, in the evolution of innate immune memory from plants to animals.

Immune memory in invertebrates

Invertebrates, including insects, worms, and molluscs, are not known to possess an adaptive immune system, and instead rely on innate immunity for protection against pathogens. In contrast to plants, many invertebrates have developed specialised immune cells, such as hemocytes (for phagocytosis and encapsulation), and cells able to produce a humoral response, such as the fat body of Drosophila and other insects. Thus, it was not thought that invertebrates possessed the adaptive immune feature of memory. However, in recent years there has been an accumulation of evidence from studies of infection, natural transplantation immunity, and individual or transgenerational immune priming that suggest invertebrates are also capable of generating immunological memory (or “priming”).

The question of immune memory in invertebrates was initially tested in the small crustacean Copepod (Macrocyclops albidus) following exposure to its natural pathogen, the parasitic tapeworm (Schistpcephalus solidus). After primary exposure to the tapeworm, the Copepods became resistant to subsequent challenges with an antigenically similar tapeworm, providing one of the first pieces of evidence for immune memory in an invertebrate species [25]. In line with this finding in crustaceans, exposing Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes to Plasmodium falciparum leads to enhanced immunity following parasite re-infection, which is recognized by an increase in circulating granulocyte numbers following the primary infection [26]. Furthermore, following an interaction with pathogenic bacteria (e.g. P. aeruginosa or S. marcescens), the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans acquires a conditioning behaviour, whereby the worm is able to avoid the bacteria following a second exposure. This avoidance “memory” generation may be driven in part by altered olfactory sensing and it has been hypothesized that immune signals generated during the first pathogen encounter may have contributed to this olfactory and neurological imprinting [27,28]. Over the years, additional studies have demonstrated the ability for invertebrates to mediate cross-protective immunity towards a secondary unrelated bacterial or fungal infection [29–32]. For example, inoculation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) protected mealworm beetles against certain fungi [30], and such studies suggest that non-specific priming of innate immune responses occurs in invertebrates and can provide substantial immunological protection.

Much of the work on immune responses within invertebrates has been carried out using the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, which relies on innate mechanisms of self versus non-self recognition through the Toll (gram-positive bacteria) and immune deficiency (Imd; gram-negative bacteria) pathways [33]. In Drosophila, priming leads to a strong protective effect against a secondary challenge with an otherwise lethal dose of a pathogen [34]; however, the specificity and duration of protection varies depending on host and microbial agent. Immune priming and “memory” in Drosophila has been shown to result in a stronger and more specific immune response upon secondary infection using Streptococcus pneumoniae and Beauveria bassina, and that the Toll pathway was essential for mediating a protective secondary response [35]. However, this priming response to infection has not been observed for all bacteria as protocols, pathogens, and timing of infections vary depending on the study. Although the Drosophila immune system can also be efficiently primed during exposure to nonpathogenic microbes, immune memory in insects remains unclear.

Insects use two distinctive RNA-based pathways against viral infections: short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs). In Drosophila, siRNA is the dominant method of anti-viral protection and its production occurs in hemocytes (cells that phagocytose invading pathogens or dead cells) following the uptake of viral RNA [36]. While plants and nematodes utilize RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps) to spread and amplify RNAi [37], flies lack RdRps suggesting there is another mechanism for RNAi spreading. Recently, novel mechanisms for RNAi amplification and dissemination were described, where a subset of immune cells in the adult fly are able to amplify siRNAs from non-germline encoded DNA, package them and disperse them to distal sites to help protect naïve cells, reminiscent of an “adaptive” immune response [38*]. Following cellular transfer to naïve animals, anti-viral siRNA conferred passive protection against viral infection [38*], similar to passive transfer of antibodies in mammals.

Additionally, evidence suggests specific traits of innate immune “memory” in insects can be generationally transferred. For example, queen Apis mellifera honeybees injected with heat-killed Paenibacillus larvae give rise to offspring that contain up to three times as many differentiated hemocytes, and survive better against P. larvae infection [39]. Furthermore, infection of the adult red flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum, a pest of stored grain) with heat-killed Bacillus thuringiensis leads to paternal priming, protecting not only the first offspring generation, but also the second [40]. Finally, infection of the crustacean Daphnia magna with pathogenic bacteria Pasteuria romosa can maternally transfer strain-specific immunity to their offspring [41].

The ability for invertebrates to form innate immune “memory” has been supported by a number of studies showing they have the potential to generate a diverse range of antigen receptors and somatic hypermutations similar to those observed in mammalian adaptive “memory” formation. The freshwater snail (Biomphalaria glabrata) demonstrates somatic recombination diversity at the immunoglobulin superfamily domains of hemolymph proteins, proposing parallels (and some conservation) between the generation of diversity and specificity in mammals via enzymes such as recombination-activating genes (RAG) and activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) [42]. A more recent study also described a molecular mechanism where alternative transcript splicing produces pathogen-specific splice variant repertoires of Dscam (Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule), a hypervariable immune effector and PRRs in insects and crustaceans [43].

Thus, this growing body of literature highlights how the invertebrate immune system in an array of species is capable of developing long-lived and specific innate immune “memory” responses similar to those observed in higher taxa. Together these findings demonstrate that invertebrate immune responses are far more robust, versatile, and complex than originally assumed. However, questions remain, do different stresses, for example abiotic (drought/light) or biotic (pathogens), lead to different epigenetic “memory” pathway activations and mechanisms? Invertebrates are extremely heterogeneous; are they all able to form some level of immune “memory” and if so, are the molecular basis of the process similar across all species? And finally, are we able to assess life-long “memory” in the same way for both invertebrates and vertebrates? Invertebrate models are far shorter lived than all the vertebrate species used to study memory, does this alter the way we look at and assess memory formation?

Immune memory in lower vertebrates

During evolution, adaptive immunity was thought to have arisen during the appearance of early jawed vertebrates [44]. Lower vertebrates, including jawed and jawless fish have been shown to possess both innate and adaptive-like immune responses [45*]. During the Early Paleozoic period (450–500 million years ago), jawless vertebrates dominated the sea; however, today they are represented by two remaining orders, the lampreys (Petromyzontiformes) and the hagfishes (Myxiniformes) [46]. Lampreys produce specific circulating agglutinins in response to immunization [47–50], reject second set skin allografts at an accelerated rate [51] and show delayed hypersensitive reactions [47]. These immune responses have been linked to cells that are morphologically similar to lymphocytes in jawed vertebrates[52,53]. These lymphocyte-like subsets and receptors within surviving jawless fish have recently been identified to resemble T and B cells and their antigen receptors in higher vertebrates [54,55], in addition to a thymus-like structure in the tips of lamprey larvae gill filaments [56]. Furthermore, these lymphocyte-like cells express transcription factors that are involved in mammalian lymphocyte differentiation (e.g. PU.1 and Ikaros) [57,58], aggregate and proliferate in response to antigenic stimulation [47], and are more irradiation sensitive than other blood cell types [52,53]. Jawless vertebrates use variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs) that are generated by RAG-independent combinatorial assembly of leucine-rich repeat cassettes for antigen (Ag) recognition (instead of the Ig-based Ag receptors used by jawed vertebrates) [45*,59–61]. Although jawed fishes possess T and B cells expressing a diverse repertoire of T-cell receptors and immunoglobulins, their responses are thought to be slower and differ from what is known in higher vertebrates (such as those measured in mice and humans) due to their inability to produce or maintain body heat [62].

Although immune memory in fish is poorly understood, significant differences between primary and secondary responses following immunization have been demonstrated in a number of fish species [63]. A more rapid secondary response and increased antibody titres were shown following immunization with bovine serum albumin (BSA) and sheep red blood cells (SRBCs) in carp [64,65] and after pathogenic infection in rainbow trout [66]. Treatment of stock fish with immunostimulants such as β-glucans (and other substances with pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)) commonly induce activation of innate immune mechanisms and higher disease resistance, suggesting fish have the ability to develop acquired immune memory [67]. Early work in frogs also identified their ability to develop immunological memory through the hypermutation of Ig genes, which was even observed in tadpoles [68,69]. Furthermore, studies in the nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum, have shown they are able to produce an IgM response following immunization, a highly antigen-specific immunoglobulin new antigen receptor (IgNAR) response, and a memory response consisting of both IgM and IgNAR isotypes [70].

The development of immune memory in lower vertebrates, specifically jawless fish, remains to be elucidated. Although previous studies have provided evidence that some fish species are able to develop immune memory following priming, the underlying molecular mechanisms behind the process are unknown.

Memory in higher vertebrate innate immune and non-immune cells

The vertebrate immune system is classically grouped into innate and adaptive responses, with innate immune cells providing the first line of defence against pathogens. Although it is now appreciated that priming can broadly influence subsequent innate as well as adaptive responses, NK cell responses emerged as one of the first examples of immune cell memory beyond adaptive lymphocytes. NK cells are classified as innate immune cells and have the ability to rapidly respond and kill transformed or virally infected cells without prior sensitisation. However, they can also exhibit characteristics of the adaptive immune response. Similarly to T cells, NK cells acquire self-tolerance during development, undergo clonal expansion during pathogen exposure, and express antigen-specific receptors (reviewed in 71). They can also generate long-lived, self-renewing memory cells able to provide potent effector function against previously encountered pathogens. There is now mounting evidence supporting immunological memory in the NK cell compartment of humans, non-human primates, and mice.

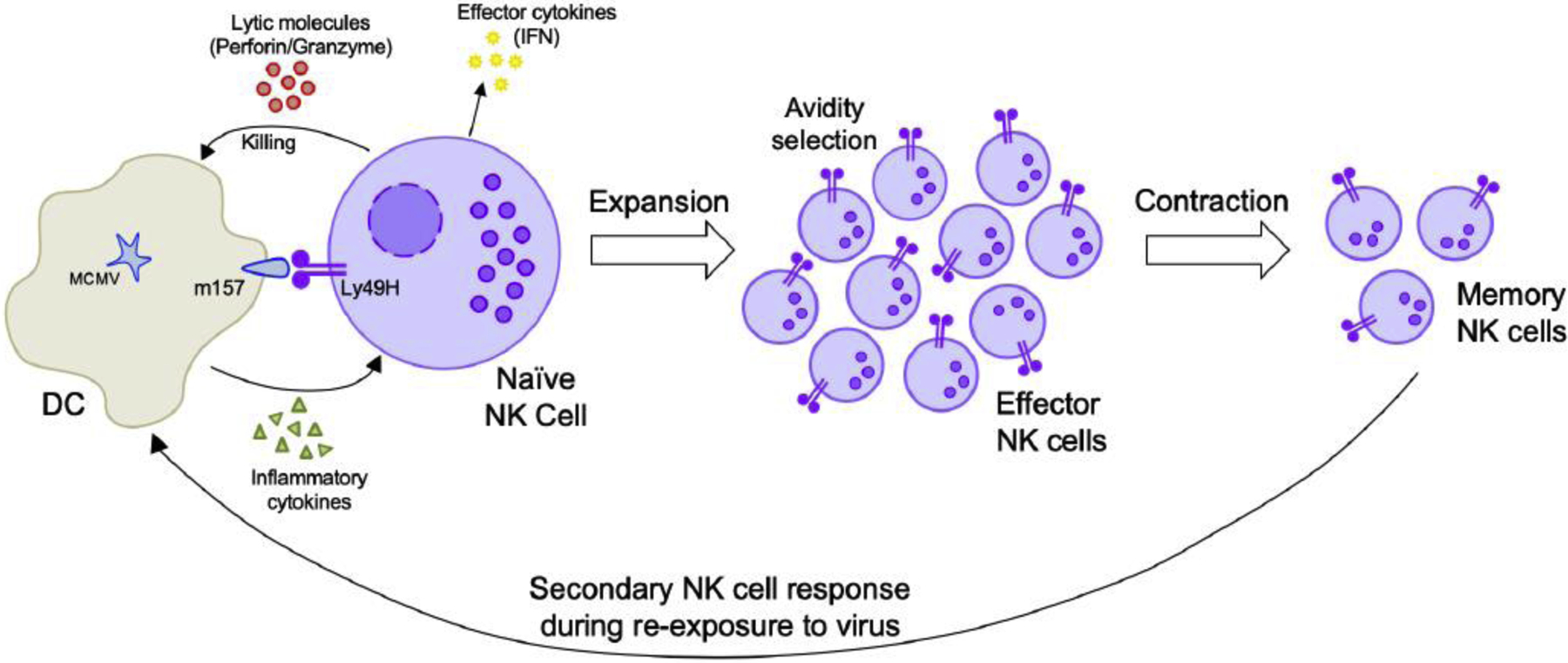

Evidence for NK cell memory against pathogens was first supported by studies using mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection as a model (Figure 2). The control of early MCMV infection is highly dependent on NK cells expressing the germline-encoded activating receptor Ly49H, which recognises the viral glycoprotein m157 on infected cells [72–76]. Memory NK cells arise from a small subset of naïve Ly49H+ NK cells with low killer cell lectin like receptor G1 (KLRG1) expression [76,77]. Recent studies have shown that NK cells with the highest avidity for m157 (Ly49Hhi NK cells) were preferentially selected to expand (giving rise to as many as 10,000 clones from a single NK cell), and preferentially contributed to the pool of memory NK cells in the blood and peripheral tissues following MCMV infection[78*,79*]. Furthermore, NK cells have the ability to form memory-like responses in additional priming strategies (reviewed in 80–82) such as hapten-specific and cytokine-induced memory [82–87]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that MCMV-specific memory NK cells undergo dynamic transcriptional and epigenetic changes throughout the course of infection, and transcriptional and epigenetic programs are shared between memory NK cells and CD8+ T cells [88*].

Figure 2. Natural Killer (NK) cell memory generation during viral infection.

During MCMV infection, NK cells recognize MCMV infected cells through Ly49H (on NK cells) and m157 (on infected cells) interactions and Ly49H+ NK cells are able to undergo clonal-like expansion, which can be partially driven by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 and IL-18. Following expansion, the Ly49H+ NK cells enter a contraction phase and produce a small pool of self-renewing, long-lived NK cells that are able to mount recall responses against subsequent viral infections. MCMV, murine cytomegalovirus; DC, dendritic cell; IFN, interferon.

Although much of the work on NK cell memory has been done in mice, work in non-human primates has also demonstrated that robust, antigen-specific NK cell memory can be induced following both HIV infection and vaccination in macaques [89]. Furthermore, similar to mouse NK cells bearing the Ly49H receptor, a small subset of human NK cells bearing the activating receptor NKG2C has been shown to undergo clonal expansion in human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-seropositive individuals during reactivation in transplant patients [90–92]. The expansion and persistence of NKG2Cbright NK cells is accompanied by global and gene-specific chromatin remodelling that impacts the behavior of the memory NK cells [93–95]. Furthermore, activating human NK cells with IL-12, IL-15 and IL-18 leads to memory-like functionality, and these pre-activated cells produce more IFN-γ following re-stimulation with cytokine or tumour cell lines [96,97].

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are tissue-resident lymphocytes that have been classified based on their regulatory programs and signature cytokine expression during early immune responses [98]. There are five major groups of ILCs, including NK cells, ILC1, ILC2, ILC3, and lymphocyte tissue inducer cells (LTi); however, recent work has suggested transcriptional heterogeneity and plasticity within these ILC subsets [99,100]. With the exception of NK cells, the majority of ILCs are not thought to possess antigen receptors, and instead respond to cytokine and inflammatory cues. Similar to NK cells, innate immunological memory has recently been identified in both ILC1s and ILC2s. ILC1s function to protect hosts from bacterial and viral infection at the initial site of infection and produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ in response to IL-12 following activation [101]. Recent work has shown that mouse ILC1s expand and contract following MCMV infection to form a stable pool of memory cells [102*]. A month after the resolution of MCMV, these ILC1s acquire stable phenotypic, transcriptional and epigenetic alterations, and demonstrated enhanced protective effector responses following a secondary challenge with MCMV[102*]. ILC2s are considered the innate counterpart of Th2 cells based on their expression of GATA3 and production of IL-5 and IL-13 [100]. ILC2 are involved in wound healing and tissue repair, and are critical during the initiation of allergic responses. Intranasal administration of pathogen (e.g. Influenza virus), allergen (e.g. Aspergillus protease or papain), or IL-33 leads to the expansion and activation of mouse lung ILC2s [103–105]. The expansion phase lasts a few days, followed by a contraction phase (where ILC2 numbers decline and they stopped producing cytokines). ILC2 numbers remained higher than naïve mice for up to one year, and following re-challenge with an unrelated pathogen (or IL-33 stimulation), ILC2 showed enhanced airway inflammation, producing higher amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 [106*]. It remains to be determined whether ILC3 and LTi also possess feature of immune memory.

Although the work on innate immune memory in vertebrates has predominantly been shown in the NK cell compartment, monocytes and macrophages can be epigenetically primed to guide enhanced innate functions against a repeat challenge in a process termed “trained immunity” [107,108]. Pre-infection of mice with a low-dose of live Candida albicans leads to protection against re-challenge in a T, B and NK cell-independent manner [109]. Pre-treatment of monocytes with C. albicans or β-glucans enhanced cytokine production in response to LPS for up to two weeks, and was associated with epigenetic alterations [109]. Following Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination (used primarily against Mycobacterium tuberculosis), human monocytes were shown to sustain enhanced pro-inflammatory cytokine levels for up to three months in response to a number of pathogens [110*]. Additionally, monocytes derived from BCG-educated hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) showed enhanced transcriptional upregulation of interferon-genes, which suggested heritable rewiring [111*]. The molecular mechanisms of pattern recognition that drive “trained immunity” remain to be understood.

Long-lived cells including stem cells and non-immune cells, (e.g. fibroblast and epithelial cells), have also been shown to possess features of memory [112,113]. Recent studies have shown that “trained immunity” may occur in long-lived HSCs and provide a mechanism for sustained, epigenetically modified immune protection [111*]. Treatment of mice with β-glucans was shown to increase myelopoiesis, which could be sustained for up to one month in vivo, and repeated β-glucan treatments were able to rescue chemically-induced myelosuppression [114]. Additionally, peripherally applied inflammatory stimulus (e.g. LPS) can induce tolerance in the brain and lead to differential epigenetic reprogramming of brain-resident microglia, that can persist for at least six months [115]. It has also been suggested that epithelial cells are able to develop memory following acute infections, as skin epithelial stem cells (EpSCs) maintained prolonged memory of acute infections and were able to rapidly respond after subsequent tissue damage [116*]. 30 days following abrasion wounding, EpSCs showed greater chromatin accessibility in inflammatory gene regions, interleukin signalling, and proliferation compared to naïve EpSCs suggesting an important role of chromatin remodelling for inflammatory memory in EpSCs [116*]. Future investigation into the stem cell compartments that retain this “memory” is required, as stem cell memory may represent a “mal-adaptation” under certain circumstances.

Vertebrates are able to mount numerous transcriptional responses when challenged with pathogens, with epigenetic programming influencing divergent patterns of gene expression and cell physiology. Moreover, it is apparent that both antigen and inflammation may program innate and adaptive immune cells (and non-immune cells) at the transcriptional and epigenetic level.

Conclusion

The rapidly growing evidence for innate immune memory in a vast array of species from numerous taxa has provided us with a new understanding of the features of the innate immune cells. Immunological memory can take shape in many different forms depending on the host, cell type, and pathogen. Innate immune memory in vertebrates has been best characterised in NK cells, and more recently in ILCs, myeloid cells, and epithelial cells. However, our understanding of innate immune memory mechanisms in lower vertebrates and invertebrates remains poorly defined.

Many questions remain to be addressed. Because stem and non-immune cells such as HSCs and epithelial cells are able to “remember” prior insults, can any cell type have the capacity and ability to form “memory” or “trained immunity”? As immune cell-microbiome interactions play important roles in the development, progression, and severity of a plethora of diseases (including diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and cancer), can factors such as the host microbiome influence how innate immune cells generate “memory”? Lastly, as transgenerational immune memory is prominent in numerous insect species, how well conserved is this process in lower vertebrates or even higher vertebrates?

In conclusion, further unravelling the properties of “innate memory” in vertebrates, plants, and invertebrates, will transform our understanding of host defence and protection. This knowledge may lead to the development of new and more specific classes of vaccines and immunotherapies for the treatment of human diseases.

Highlights.

Although classic immunological memory is a hallmark trait of T and B cells of the adaptive immune response in higher vertebrates, the ability to form immunological memory has been described in many taxa, including plants, invertebrates, and lower vertebrates.

Innate immune and non-immune cells, including NK cells, ILCs, macrophages, and epithelial cells have now been reported to possess features of immunological memory.

Epigenetic modifications play important roles in memory formation in immune and non-immune cells.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Adriana Mujal and Dr. Katrin Kierdorf for the useful discussion and comments on this review. The Sun lab was supported by grants from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the American Cancer Society, and the National Institutes of Health (AI100874, AI130043, and P30CA008748).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none

References

- 1.Netea MG, Schlitzer A, Placek K, Joosten LAB & Schultze JL Innate and Adaptive Immune Memory: an Evolutionary Continuum in the Host’s Response to Pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 25, 13–26 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gourbal B et al. Innate immune memory: An evolutionary perspective. Immunol. Rev 283, 21–40 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones JDG & Dangl JL The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323–329 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chester KS The Problem of Acquired Physiological Immunity in Plants. Q. Rev. Biol 8, 129–154 (1933). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuć J Induced Immunity to Plant Disease. BioScience 32, 854–860 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- *6.Reimer-Michalski E-M & Conrath U Innate immune memory in plants. Semin. Immunol 28, 319–327 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckers GJ & Conrath U Priming for stress resistance: from the lab to the field. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol 10, 425–431 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walters DR, Ratsep J & Havis ND Controlling crop diseases using induced resistance: challenges for the future. J. Exp. Bot 64, 1263–1280 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walters DR & Bingham IJ Influence of nutrition on disease development caused by fungal pathogens: implications for plant disease control. Ann. Appl. Biol 151, 307–324 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heil M Ecological costs of induced resistance. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol 5, 345–350 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heil M & Ploss K Induced resistance enzymes in wild plants-do ‘early birds’ escape from pathogen attack? Naturwissenschaften 93, 455–460 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walters D & Heil M Costs and trade-offs associated with induced resistance. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol 71, 3–17 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sticher L, Mauch-Mani B & Métraux JP Systemic acquired resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol 35, 235–270 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spoel SH & Dong X How do plants achieve immunity? Defence without specialized immune cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol 12, 89–100 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beckers GJM et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinases 3 and 6 are required for full priming of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21, 944–953 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah J & Zeier J Long-distance communication and signal amplification in systemic acquired resistance. Front. Plant Sci 4, 30 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavet V, Quintero C, Cecchini NM, Rosa AL & Alvarez ME Arabidopsis Displays Centromeric DNA Hypomethylation and Cytological Alterations of Heterochromatin Upon Attack by Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact 19, 577–587 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luna E, Bruce TJA, Roberts MR, Flors V & Ton J Next-Generation Systemic Acquired Resistance1[W][OA]. Plant Physiol. 158, 844–853 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarillo JA, Piñeiro M, Cubas P & Martínez-Zapater JM Chromatin remodeling in plant development. Int. J. Dev. Biol 53, 1581–1596 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badeaux AI & Shi Y Emerging roles for chromatin as a signal integration and storage platform. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 14, 211–224 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henikoff S & Shilatifard A Histone modification: cause or cog? Trends Genet. TIG 27, 389–396 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarez-Venegas R, Abdallat AA, Guo M, Alfano JR & Avramova Z Epigenetic control of a transcription factor at the cross section of two antagonistic pathways. Epigenetics 2, 106–113 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laura B, Silvia P, Francesca F, Benedetta S & Carla C Epigenetic control of defense genes following MeJA-induced priming in rice (O. sativa). J. Plant Physiol 228, 166–177 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaskiewicz M, Conrath U & Peterhänsel C Chromatin modification acts as a memory for systemic acquired resistance in the plant stress response. EMBO Rep. 12, 50–55 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurtz J & Franz K Innate defence: evidence for memory in invertebrate immunity. Nature 425, 37–38 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodrigues J, Brayner FA, Alves LC, Dixit R & Barillas-Mury C Hemocyte Differentiation Mediates Innate Immune Memory in Anopheles gambiae Mosquitoes. Science 329, 1353–1355 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Lu H & Bargmann CI Pathogenic bacteria induce aversive olfactory learning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 438, 179–184 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beale E, Li G, Tan M-W & Rumbaugh KP Caenorhabditis elegans Senses Bacterial Autoinducers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 72, 5135–5137 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faulhaber LM & Karp RD A diphasic immune response against bacteria in the American cockroach. Immunology 75, 378–381 (1992). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moret Y & Siva-Jothy MT Adaptive innate immunity? Responsive-mode prophylaxis in the mealworm beetle, Tenebrio molitor. Proc. Biol. Sci 270, 2475–2480 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan I, Prakash A & Agashe D Experimental evolution of insect immune memory versus pathogen resistance. Proc. Biol. Sci 284, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergin D, Murphy L, Keenan J, Clynes M & Kavanagh K Pre-exposure to yeast protects larvae of Galleria mellonella from a subsequent lethal infection by Candida albicans and is mediated by the increased expression of antimicrobial peptides. Microbes Infect. 8, 2105–2112 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lemaitre B & Hoffmann J The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Immunol 25, 697–743 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper D & Eleftherianos I Memory and Specificity in the Insect Immune System: Current Perspectives and Future Challenges. Front. Immunol 8, 539 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pham LN, Dionne MS, Shirasu-Hiza M & Schneider DS A Specific Primed Immune Response in Drosophila Is Dependent on Phagocytes. PLOS Pathog. 3, e26 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swevers L, Liu J & Smagghe G Defense Mechanisms against Viral Infection in Drosophila: RNAi and Non-RNAi. Viruses 10, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding S-W RNA-based antiviral immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol 10, 632–644 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *38.Tassetto M, Kunitomi M & Andino R Circulating Immune Cells Mediate a Systemic RNAi-Based Adaptive Antiviral Response in Drosophila. Cell 169, 314–325.e13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez Lopez J, Schuehly W, Crailsheim K & Riessberger-Galle U Trans-generational immune priming in honeybees. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci 281, 20140454–20140454 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schulz NKE, Sell MP, Ferro K, Kleinhölting N & Kurtz J Transgenerational Developmental Effects of Immune Priming in the Red Flour Beetle Tribolium castaneum. Front. Physiol 10, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Little TJ & Killick SC Evidence for a cost of immunity when the crustacean Daphnia magna is exposed to the bacterial pathogen Pasteuria ramosa. J. Anim. Ecol 76, 1202–1207 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang S-M & Loker ES Representation of an immune responsive gene family encoding fibrinogen-related proteins in the freshwater mollusc Biomphalaria glabrata, an intermediate host for Schistosoma mansoni. Gene 341, 255–266 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong Y, Cirimotich CM, Pike A, Chandra R & Dimopoulos G Anopheles NF-κB -regulated splicing factors direct pathogen-specific repertoires of the hypervariable pattern recognition receptor AgDscam. Cell Host Microbe 12, 521–530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Litman GW, Rast JP & Fugmann SD The origins of vertebrate adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol 10, 543–553 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *45.Boehm T et al. Evolution of Alternative Adaptive Immune Systems in Vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Immunol 36, 19–42 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uinuk-ool T et al. Lamprey lymphocyte-like cells express homologs of genes involved in immunologically relevant activities of mammalian lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 99, 14356–14361 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finstad J & Good RA THE EVOLUTION OF THE IMMUNE RESPONSE. 3. IMMUNOLOGIC RESPONSES IN THE LAMPREY. J. Exp. Med 120, 1151–1168 (1964). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marchalonis JJ & Edelman GM Phylogenetic origins of antibody structure. 3. Antibodies in the primary immune response of the sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus. J. Exp. Med 127, 891–914 (1968). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pollara B, Litman GW, Finstad J, Howell J & Good RA The evolution of the immune response. VII. Antibody to human ‘O’ cells and properties of the immunoglobulin in lamprey. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 105, 738–745 (1970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagen M, Filosa MF & Youson JH The immune response in adult sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus L.): the effect of temperature. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 82, 207–210 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perey DY, Finstad J, Pollara B & Good RA Evolution of the immune response. VI. First and second set skin homograft rejections in primitive fishes. Lab. Investig. J. Tech. Methods Pathol 19, 591–597 (1968). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pancer Z et al. Somatic diversification of variable lymphocyte receptors in the agnathan sea lamprey. Nature 430, 174–180 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alder MN et al. Diversity and function of adaptive immune receptors in a jawless vertebrate. Science 310, 1970–1973 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo P et al. Dual Nature of the Adaptive Immune System in Lampreys. Nature 459, 796–801 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hirano M et al. Evolutionary implications of a third lymphocyte lineage in lampreys. Nature 501, 435–438 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bajoghli B et al. A thymus candidate in lampreys. Nature 470, 90–94 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mayer WE et al. Isolation and characterization of lymphocyte-like cells from a lamprey. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 99, 14350–14355 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson MK, Sun X, Miracle AL, Litman GW & Rothenberg EV Evolution of hematopoiesis: Three members of the PU.1 transcription factor family in a cartilaginous fish, Raja eglanteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 98, 553–558 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han BW, Herrin BR, Cooper MD & Wilson IA Antigen recognition by variable lymphocyte receptors. Science 321, 1834–1837 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alder MN et al. Antibody responses of variable lymphocyte receptors in the lamprey. Nat. Immunol 9, 319–327 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cooper MD & Herrin BR How did our complex immune system evolve? Nat. Rev. Immunol 10, 2–3 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mashoof S & Criscitiello MF Fish Immunoglobulins. Biology 5, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamaguchi T, Quillet E, Boudinot P & Fischer U What could be the mechanisms of immunological memory in fish? Fish Shellfish Immunol. 85, 3–8 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Avtalion RR Temperature effect on antibody production and immunological memory, in carp (Cyprinus carpio) immunized against bovine serum albumin (BSA). Immunology 17, 927–931 (1969). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rijkers GT, Van Oosterom R & Van Muiswinkel WB The immune system of cyprinid fish. Oxytetracycline and the regulation of humoral immunity in carp (Cyprinus carpio). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 2, 281–290 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tatner MF The quantitative relationship between vaccine dilution, length of immersion time and antigen uptake, using a radiolabelled Aeromonas salmonicida bath in direct immersion experiments with rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri. Aquaculture 62, 173–185 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang F et al. Failure to detect ecological and evolutionary effects of harvest on exploited fish populations in a managed fisheries ecosystem. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci 75, 1764–1771 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Steiner LA, Mikoryak CA, Lopes AD & Green C Immunoglobulins in ranid frogs and tadpoles. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 64, 173–183 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hadji-Azimi I Structural studies of the Xenopus 19S immunoglobulin and 7S immunoglobulin and two immunoglobulin-like proteins. Immunology 28, 419–429 (1975). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dooley H & Flajnik MF Shark immunity bites back: affinity maturation and memory response in the nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum. Eur. J. Immunol 35, 936–945 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rapp M, Wiedemann GM & Sun JC Memory responses of innate lymphocytes and parallels with T cells. Semin. Immunopathol 40, 343–355 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith HRC et al. Recognition of a virus-encoded ligand by a natural killer cell activation receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99, 8826–8831 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Daniels KA et al. Murine cytomegalovirus is regulated by a discrete subset of natural killer cells reactive with monoclonal antibody to Ly49H. J. Exp. Med 194, 29–44 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brown MG et al. Vital involvement of a natural killer cell activation receptor in resistance to viral infection. Science 292, 934–937 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Arase H, Mocarski ES, Campbell AE, Hill AB & Lanier LL Direct recognition of cytomegalovirus by activating and inhibitory NK cell receptors. Science 296, 1323–1326 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sun JC, Beilke JN & Lanier LL Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature 457, 557–561 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kamimura Y & Lanier LL Homeostatic control of memory cell progenitors in the natural killer cell lineage. Cell Rep. 10, 280–291 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *78.Adams NM et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection Drives Avidity Selection of Natural Killer Cells. Immunity 50, 1381–1390.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *79.Grassmann S et al. Distinct Surface Expression of Activating Receptor Ly49H Drives Differential Expansion of NK Cell Clones upon Murine Cytomegalovirus Infection. Immunity 50, 1391–1400.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sun JC & Lanier LL Is There Natural Killer Cell Memory and Can It Be Harnessed by Vaccination? Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 10, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA & Colonna M Is There Natural Killer Cell Memory and Can It Be Harnessed by Vaccination? Vaccination Strategies Based on NK Cell and ILC Memory. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol a029512 (2017). doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a029512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Neely HR, Mazo IB, Gerlach C & von Andrian UH Is There Natural Killer Cell Memory and Can It Be Harnessed by Vaccination? Natural Killer Cells in Vaccination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 10, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Paust S et al. Critical role for the chemokine receptor CXCR6 in NK cell-mediated antigen-specific memory of haptens and viruses. Nat. Immunol 11, 1127–1135 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Romee R et al. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells exhibit enhanced responses against myeloid leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med 8, 357ra123–357ra123 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Keppel MP, Yang L & Cooper MA Murine NK Cell Intrinsic Cytokine-Induced Memory-like Responses Are Maintained following Homeostatic Proliferation. J. Immunol 1201742 (2013). doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cooper MA et al. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 1915–1919 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.O’Leary JG, Goodarzi M, Drayton DL & von Andrian UH T cell- and B cell-independent adaptive immunity mediated by natural killer cells. Nat. Immunol 7, 507–516 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *88.Lau CM et al. Epigenetic control of innate and adaptive immune memory. Nat. Immunol 19, 963 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reeves RK et al. Antigen-specific NK cell memory in rhesus macaques. Nat. Immunol 16, 927–932 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lopez-Vergès S et al. Expansion of a unique CD57+NKG2Chi natural killer cell subset during acute human cytomegalovirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108, 14725–14732 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Della Chiesa M et al. Phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of human NK cells developing after umbilical cord blood transplantation: a role for human cytomegalovirus? Blood 119, 399–410 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Foley B et al. Human cytomegalovirus (CMV)-induced memory-like NKG2C(+) NK cells are transplantable and expand in vivo in response to recipient CMV antigen. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 189, 5082–5088 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Luetke-Eversloh M et al. Human Cytomegalovirus Drives Epigenetic Imprinting of the IFNG Locus in NKG2Chi Natural Killer Cells. PLoS Pathog. 10, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee J et al. Epigenetic Modification and Antibody-Dependent Expansion of Memory-like NK Cells in Human Cytomegalovirus-Infected Individuals. Immunity 42, 431–442 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schlums H et al. Cytomegalovirus infection drives adaptive epigenetic diversification of NK cells with altered signaling and effector function. Immunity 42, 443–456 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Romee R et al. Cytokine activation induces human memory-like NK cells. Blood 120, 4751–4760 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ni J, Miller M, Stojanovic A, Garbi N & Cerwenka A Sustained effector function of IL-12/15/18–preactivated NK cells against established tumors. J. Exp. Med 209, 2351–2365 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cella M et al. Subsets of ILC3−ILC1-like cells generate a diversity spectrum of innate lymphoid cells in human mucosal tissues. Nat. Immunol 20, 980–991 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Colonna M Innate Lymphoid Cells: Diversity, Plasticity and Unique Functions in Immunity. Immunity 48, 1104–1117 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vivier E et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells: 10 Years On. Cell 174, 1054–1066 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Weizman O-E et al. ILC1 confer early host protection at initial sites of viral infection. Cell 171, 795–808.e12 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *102.Weizman O-E et al. Mouse cytomegalovirus-experienced ILC1s acquire a memory response dependent on the viral glycoprotein m12. Nat. Immunol 20, 1004–1011 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Monticelli LA et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat. Immunol 12, 1045–1054 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chang Y-J et al. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat. Immunol 12, 631–638 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Moro K et al. Innate production of T 2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit+ H Sca-1+ lymphoid cells. Nature 463, 540–544 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *106.Martinez-Gonzalez I et al. Allergen-Experienced Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Acquire Memory-like Properties and Enhance Allergic Lung Inflammation. Immunity 45, 198–208 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.van der Heijden CDCC et al. Epigenetics and Trained Immunity. Antioxid. Redox Signal 29, 1023–1040 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Netea MG et al. Trained immunity: a program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science 352, aaf1098 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Quintin J et al. Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell Host Microbe 12, 223–232 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *110.Kleinnijenhuis J et al. Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 17537–17542 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *111.Kaufmann E et al. BCG Educates Hematopoietic Stem Cells to Generate Protective Innate Immunity against Tuberculosis. Cell 172, 176–190.e19 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Crowley T, Buckley CD & Clark AR Stroma: the forgotten cells of innate immune memory. Clin. Exp. Immunol 193, 24–36 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hamada A, Torre C, Drancourt M & Ghigo E Trained Immunity Carried by Non-immune Cells. Front. Microbiol 9, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mitroulis I et al. Modulation of Myelopoiesis Progenitors Is an Integral Component of Trained Immunity. Cell 172, 147–161.e12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wendeln A-C et al. Innate immune memory in the brain shapes neurological disease hallmarks. Nature 556, 332–338 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *116.Naik S et al. Inflammatory memory sensitizes skin epithelial stem cells to tissue damage. Nature 550, 475–480 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]