Abstract

Regulatory noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) are a class of RNAs transcribed by regions of the human genome that do not encode for proteins. The three main members of this class, named microRNA, long noncoding RNA, and circular RNA play a key role in the regulation of gene expression, eventually shaping critical cellular processes. Compelling experimental evidence shows that ncRNAs function either as tumor suppressors or oncogenes by participating in the regulation of one or several cancer hallmarks, including evading cell death, and their expression is frequently deregulated during cancer onset, progression, and dissemination. More recently, preclinical and clinical studies indicate that ncRNAs are potential biomarkers for monitoring cancer progression, relapse, and response to cancer therapy. Here, we will discuss the role of noncoding RNAs in regulating cancer cell death, focusing on those ncRNAs with a potential clinical relevance.

Subject terms: Long non-coding RNAs, miRNAs

Facts

Many of the genetic and epigenetics alterations in human cancers are found in noncoding regions of the DNA.

miRNAs and lncRNAs have been largely described in their role in controlling epithelial tissues homeostasis, both in physiological and pathological conditions such as cancer.

The clinical application of ncRNAs is already under evaluation in ongoing clinical trials exploring their role as biomarkers for patient survival, metastasis development prediction, or therapy response.

Open questions

What is the role of regulatory ncRNA in pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and autophagy?

What is the functional interplay between miRNA, lncRNA, and circRNA in cancer biology?

How can we integrate preclinical findings to select the best regulatory ncRNA for clinical studies?

Introduction

Protein-coding genes undoubtfully play an established role in cancer transformation and progression, however, recent compelling evidence is highlighting a role for noncoding RNAs. There is no question that loss or mutation of crucial genes are frequent events in cancer biology: the mutation of the tumor suppressor gene p53 is observed in almost 50% of human cancers1–7, and the amplification of the oncogene MYC8 or the translocation of BCL-2 gene9–12 are crucial drivers in various cancer contexts13–16. However, many of the recurrent genetic and epigenetic alterations are found in genes that do not codify for proteins but that codify for an entire class of molecules called noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), which play a key role in the regulation of many cellular activities.

The non-protein-coding regions of the human genome are transcribed into molecules of RNA classified as regulatory noncoding RNAs17. ncRNAs are mainly transcribed by RNA polymerase II and share several characteristics with messenger RNAs (mRNAs). Indeed, they have a cap structure at the 5′ end, a poly(A) tail at the 3′ end and their expression is controlled by canonical promoter elements and transcription factors. Conventionally, regulatory ncRNAs are classified either as small ncRNAs, if they are shorter than 200 ribonucleotides or as long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), longer than 200 ribonucleotides. Small ncRNAs include microRNAs (miRNAs), which mediates post-transcriptional RNA silencing, piwiRNAs, which regulate chromatin modifications and transposons repression, as well as the more recent circular RNAs (circRNAs)18.

In this review, we shall discuss the role of ncRNAs in regulating cancer cell death (Table 1)19. In particular, we will describe those regulatory ncRNAs that have been largely investigated, on the basis of both in vitro and in vivo evidence as clinical data.

Table 1.

Pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic ncRNAs.

| ncRNA | PRO-apoptotic role | Cellular/animal model | Relevant references (original papers) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Let-7 |

• Inhibition of BCL2L1 • Upregulation of BAK and BAX, and downregulation of BCL-xL |

• Colorectal cancer • Leukemia |

Mizuno et al.46 Huang et al.47 |

| miR-15/16 | • Repression of BCL-2 and BMI1 |

• Chronic lymphatic leukemia • Mantle cell lymphoma |

Cimmino et al.52 Teshima et al.53 |

| miR-34 | • Regulation of proteins involved in cell death: BCL-2, BIRC5 (Survivin), CREB, and YY1 |

• Pancreatic cancer • Myeloid leukemia • Neuroblastoma • Laryngeal squamous cell cancer |

Chang et al.67 Pigazzi et al.68 Chen et al.69 Shen et al.70 |

| miR-29 | • Repression of MCL-1 expression | • Acute myeloid leukemia | Garzon et al.76 |

| GAS5 | • Induction of apoptosis in a mouse model | • Brest cancer (mouse) | Mourtada-Maarabouni et al.103 |

| MEG3 | • Induction of p53 | • Colorectal cancer | Zhou et al.108 |

| NIKLA | • Activation of apoptosis in tumor-specific CTLs | • Breast cancer and lung cancer | Huang et al.113 |

| NEAT1a | • Enhanced apoptosis after DNA damage | • Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Blume et al.116 |

| circFOXO3 | • Increased PUMA expression | • Breast cancer (mouse) | Du et al.147 |

| ncRNA | ANTI-apoptotic role | Cellular/animal model | Relevant references (original papers) |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | • expression of pro-apoptotic genes: APAF11, PDCD4, RHOB, and FASLG | • Non-small cell lung cancer | Hatley et al.84 |

| miR-155 | • Repression of SHIP-1 |

• B lymphocytes • Hematopoietic cells |

Costinean et al.91 O’Connell et al.92 |

| miR-221 | • Increased apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest | • Hepatocellular carcinoma | Park et al.98 |

| CCAT | • Interaction with p63 and SOX2 | • Squamous cell carcinoma | Jiang et al.123 |

| FAL1 | • Interaction with BMI1 | • Pan-cancer database | Hu et al.128 |

| PVT1 | • Downregulation of Caspase-7, Caspase-9, and PARP | • Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | He et al.132 |

aControversial role since NEAT1 has also been correlated to an oncogenic activity in some tumor types.

Epithelial ncRNAs

Recently, miRNAs and lncRNAs have gained significant attention for their role in controlling epithelial tissue homeostasis in normal and pathological conditions, being key regulators of epithelial progenitor stem cells proliferation, somatic lineage specification, and differentiation20,21.

Distinct miRNAs control epidermal development, epidermal differentiation, and adult stem cells maintenance (for reviews see refs. 22,23). These include the miR-20 family, miR-24, the miR-200 family, miR-205, and miR-20324–28. The latter has been described in his mechanistic role in the control of epithelial progenitor cells proliferation and in the inhibition of cellular senescence, having as a target one of the epithelial master genes, the transcription factor TP6324,29. Interestingly, these epithelial-specific miRNAs have also been implicated in controlling key regulators genes of the pathogenesis of many adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas (SCC)30. As an example, the miR-200 family, controlling the expression of ZEB1 and ZEB2, have been described in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in ovarian cancer and SCCs. Moreover, miR-203, targeting ABL1, SOCS3, and ZEB3, controls EMT in epithelial cancers28,31. miRNAs also play a key role in epithelial cells upon different environmental stressors, such us UV radiations and inflammation32–36.

Only a few lncRNAs have been studied so far in the regulation of epithelial development, such as ANCR, an anti-differentiation lncRNA, and TINCR, a terminal differentiation-induced lncRNA; however, the mechanism through which they maintain the cell of the epidermis in a undifferentiated state has not been identified yet37,38. Similarly, LIN00941 has also been implicated in the control of epidermal homeostasis repressing the expression of pro-differentiation genes through a not-yet identified mechanism39. Moreover, the pro-differentiation lncRNA, uc.291, has been shown acting as a pro-differentiation transcript by facilitating the activation/binding of the chromatin remodeling complex SWI/SNF (BAF) in proximity to the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC) genes to allow their expression40.

While several studies investigated the specific contributions of miRNAs in epithelial cancer development, the role of lncRNAs in this context has not been investigated thoroughly yet.

microRNAs with pro-apoptotic functions

let-7

let-7 has been one of the first miRNAs isolated and characterized in the nematode C. elegans. The human genome contains 13 let-7 family member genes, which are distributed in different genomic loci and codify for 9 mature miRNAs41. Let-7 expression is downregulated in many cancers, such as lung, breast, pancreatic cancer, and melanoma and in many cancer-associated clinical conditions like cholestasis42. Moreover, downregulation of let-7 expression correlates with poor survival in lung cancer43, ovarian cancer44, and head and neck SCC patients45. Functionally, let-7 acts as a tumor suppressor partially through the downregulation of several genes involved in cell death, as shown by the ectopic expression of let-7 resulting in the inhibition of BCL2L1 in colorectal cancer46 or by the induction of apoptosis via upregulation of BAK and BAX and downregulation of BCL-XL protein levels47. Although in vivo delivery of let-7 in mouse models of lung cancer demonstrated its therapeutic potential, its tumor suppressor functions might be associated with repression of cell proliferation and elimination of cancer cells mainly through a non-apoptotic mechanism48.

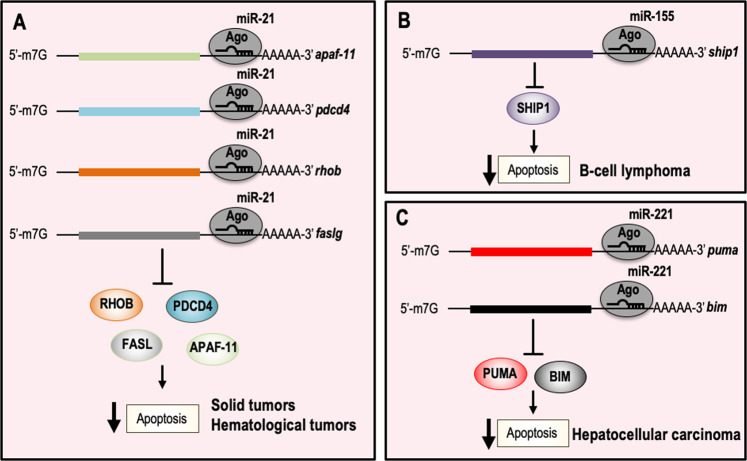

miR-15/16

miR-15 and miR-16 are localized on chromosome 13q14. This chromosomic region is frequently deleted in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL)49. miR-15 and miR-16 are found in a 30-kb region, which is lost in CLL, and both genes are either deleted or downregulated in most of CLL cases (~68%)50. However, several studies suggested that miR-15/16 could be also downregulated by additional mechanisms, such as defective DROSHA processing or epigenetic alterations51. The tumor suppressor action of miR-15/16 is the result of the induction of cell death through the repression of the anti-apoptotic proteins BCL-2 and BMI1 (Fig. 1a)52–57. More recently, the tumor suppressor function of miR-15/16 has also been observed in solid tumors such as mesothelioma58 or chondrosarcomas59, where its expression is suppressed in order to promote tumor neo-angiogenesis. Moreover, the miR-15/16 knockout mouse model supports the in vivo tumor suppressor activity of miR-15/16. Indeed, deletion of miR-15/16 gene results in B cells proliferation and in the development of lymphoid malignancies60,61.

Fig. 1. microRNAs with pro-apoptotic functions and relative inhibited molecular pathways.

a miR-15/16 expression is deregulated in hematological malignancies and induces cell death by inhibiting the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 and BMI1. b miR-34a acts as a tumor suppressor gene by directly repressing the expression of several proteins involved in the regulation of cell survival. c miR-29a regulates the critical anti-apoptotic genes MCL-1. MCL-1 is an anti-apoptotic protein that promotes cancer cell survival and proliferation, and it is frequently overexpressed in AML. It has been also shown that miR-29 can induce cell death by inducing the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins, including BIM and PDCD4. BCL-2 B-cell lymphoma 2 gene, BMI1 polycomb complex protein BMI1, MCL-1 induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein, BIM BCL-2-like protein 11, PDCD4 programmed cell death protein 4, AML acute myeloid leukemia.

miR-34

The miR-34 family consists of three different transcripts miR-34a, miR-34b, and miR-34c with high sequence homology.

In humans, the miR-34a gene is located on the chromosomal region 1p36.22, which is frequently deleted in many human cancers, including neuroblastoma, glioma, breast cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and melanoma62–64. The miR-34b and miR-34c genes are both encoded on chromosome 11q23.1, and rearrangements of this region have been observed in several solid tumors and in hematological malignancies65. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that the miR-34 family genes (in particular miR-34a) act as tumor suppressors: when overexpressed they repress several oncogenes, resulting in an increased cancer cell death and in an inhibition of metastasis development. miR-34a has also been shown to play a role in the regulation of NF-κB in CD8 + T cells, promoting their cytotoxic activity66. In the context of cell death, miR-34 family acts on proteins such as BCL-2, BIRC5 (Survivin), CREB, and YY1, which are involved in apoptosis regulation (Fig. 1b)67–71.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that miR-34-deficient animals are not showing increased susceptibility to either spontaneous or to irradiation-induced nor MYC-initiated tumorigenesis.

Strikingly in 2013, a miR-34 mimic (MRX34) became the first microRNA tested in a phase 1 clinical trial (NCT002862145). In particular, a liposomal miR-34 mimetic was administered intravenously to patients with unresectable liver cancer or metastatic cancer refractory to standard treatment, with or without liver involvement. From these studies, MRX34 treatment was associated with antitumor activity and acceptable safety, but subsequent monitoring showed immune-related toxicities. To date, it is not clear whether further clinical trials will be started72.

miR-29

The miR-29 family is composed of three isoforms. miR-29b-1 and miR-29a form one cluster on chromosome 7q32, while miR-29b-2 and miR-29c form a second cluster on chromosome 1q23. Of note that the first cluster region is frequently deleted in myelodysplastic syndromes and therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (AML)73,74. In addition, several experimental observations showed that miR-29 family is downregulated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, lung cancer, invasive breast cancer, and cholangiocarcinoma. miR-29 functions as a tumor suppressor gene in several cancer types. Indeed, ectopic expression of miR-29b induced apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cell lines and reduced tumorigenicity in a xenograft model of lung cancer, rhabdomyosarcoma, and AML75. Mechanistically, miR-29 induces cell death by directly repressing the expression of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family member, MCL-1 (Fig. 1c)76. In addition, modulation of miR-29 expression results in the upregulation of some pro-apoptotic genes, such as BIM and the tumor suppressor programmed cell death-4 (PDCD4) in AML, and also inhibits the expression of DNMT3B in hepatocarcinoma cell lines77. Interestingly, MCL-1 mRNA inversely correlated with miR-29a or miR-29b expression in 45 primary AML samples78.

microRNAs with anti-apoptotic functions

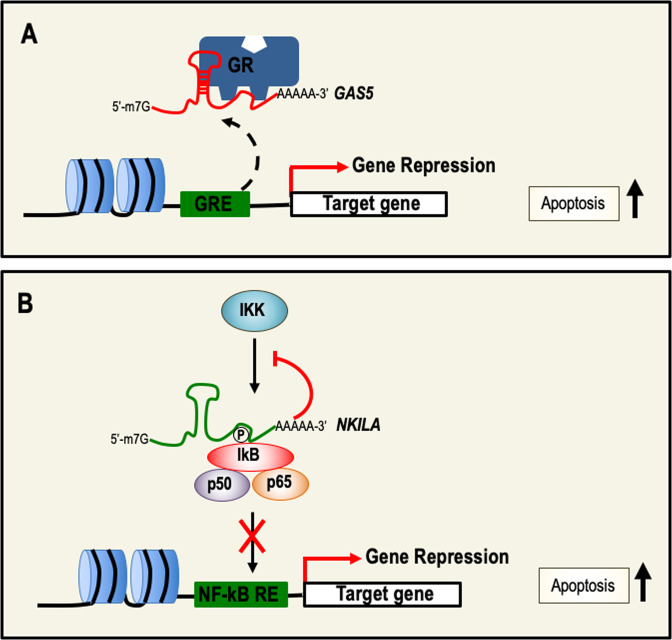

miR-21

The human miR-21 gene is located in the fragile site FRA17B on chromosome 17q23.279. Expression profile studies on tumor samples, including lung, breast, stomach, prostate, colon, pancreatic tumors, and B-cell lymphomas showed that miR-21 is the most commonly upregulated miRNA in solid tumors and hematological malignancies, indicating miR-21 as an “oncomiR”80–82. Indeed, functional studies in several cancer cell lines demonstrated that knockdown of miR-21 activates caspases leading to apoptotic cell death. Moreover, in vitro evidence also suggested a positive regulatory role in pyroptosis through the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome83. At a molecular level, miR-21 suppresses the expression of pro-apoptotic genes, such as APAF11, PDCD4, RHOB, and FASLG (Fig. 2a)84. The oncogenic role of miR-21 was also confirmed in vivo by generating conditionally expressing miR-21 mice84. This mouse model demonstrated that miR-21 is capable of initiation, maintenance, and prolonged survival of tumors in vivo and demonstrated the importance of miR-21 in hematological malignancies85.

Fig. 2. microRNAs with anti-apoptotic functions and relative inhibited molecular pathways.

a miR-21 is the most upregulated oncomiR in solid tumors and hematological malignancies. The oncogenic activity of miR-21 is associated with the direct negative regulation of pro-apoptotic genes, such as APAF11, PDCD4, RHOB, and FASLG. b miR-155 plays a key role in the regulation of the immune response. miR-155 is upregulated in B-cell lymphomas and by targeting SHIP-1 supports cell survival. c In liver cancer, miR-221 exerts oncogenic activity by repressing the expression of the apoptotic proteins PUMA and BIM. APAF11 apoptotic protease activating factor 1, PDCD4 programmed cell death protein 4, RHOB Ras Homolog Family Member B, FASLG Fas ligand, SHIP-1 Src homology 2-SH2 domain containing inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase 1, PUMA p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis, BIM BCL-2-like protein 11.

miR-155

The human gene miR-155 is localized on chromosome 21 within an exon of a noncoding RNA, from the B-cell Integration Cluster (BIC)86. miR-155 is mainly expressed in lymphoid tissues, including thymus and spleen, where it regulates several physiological functions of these organs, such as antibodies and cytokines production87. In addition, several observations have shown that miR-155 is accumulated in non-Hodgkin lymphomas, as in the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, and Burkitt lymphomas and in Hodgkin lymphomas88–90. The oncogenic role of miR-155 was confirmed by the generation of genetically modified mice, developing B-cell lymphoma upon its overexpression. Among the molecular mechanisms underlying its oncogenic properties, the direct repression of SH2-containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP-1) (Fig. 2b)91,92, a positive regulator of apoptosis, seems to play a pivotal role. Apart from hematologic malignancies, miR-155 is also overexpressed in several solid tumors, such as breast, colon, pancreatic, and lung cancer, and has also been described in the regulation of autophagy in an experimental mouse model of pancreatitis93. More recently, the therapeutic efficacy of an anti-miR-155 was tested in vivo by using a novel delivery system targeting the acidic tumor microenvironment: a nucleic acid anti-miR-155 linked to a peptide with a low pH-induced transmembrane structure (pHLIP) effectively inhibited miR-155 expression after intravenous administration, leading to cancer regression in a mouse model of lymphoma94.

miR-221

miR-221/222 is a microRNA with oncogenic properties, highly conserved in vertebrates, located on the X chromosome in humans, mice, and rats. Overexpression of miR-221/222 has been observed in several human malignancies, including hepatocellular carcinoma, breast, prostate, pancreatic cancer, and glioblastoma95,96. The oncogenic activities of miR-221 were also confirmed in vivo as the overexpression of miR-221 in p53−/−; Myc liver progenitors stimulates tumor onset and progression97. The oncogenic activity of miR-221 might be partially explained by the repression of PUMA and BIM proteins (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, in vivo preclinical studies showed that a cholesterol-modified isoform of anti-miR-221 significantly reduced miR-221 levels in livers after injection, reducing tumor cell proliferation, and increasing the expression of apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest markers, eventually prolonging mice survival98. Although miR-221 is classified as an “oncomiR”, it should be noted that his role as tumor suppressor gene has also been observed99.

Long noncoding RNAs

Long noncoding RNAs are classified as endogenous ncRNAs longer than 200 nucleotides. They are transcribed by RNA polymerase II from an independent promoter and processed as coding RNAs. Indeed, they are capped, spliced, and polyadenylated, however, lncRNAs lack a significant open-reading frame. Compared with protein-coding transcripts, lncRNAs are overall expressed at lower levels and they are not highly evolutionarily conserved, with only 5–6% of lncRNAs harboring conserved sequences100.

Several studies have described a range of molecular mechanisms by which lncRNAs may exert their functions. In particular, lncRNAs have been described as molecular scaffolds or architectural RNAs in a variety of cellular processes, among which epigenetics modifications, alternative splicing, mRNA translation, and maintenance, and acting as decoys or “sponges” for miRNAs or transcription factors.

lncRNAs with pro-apoptotic function

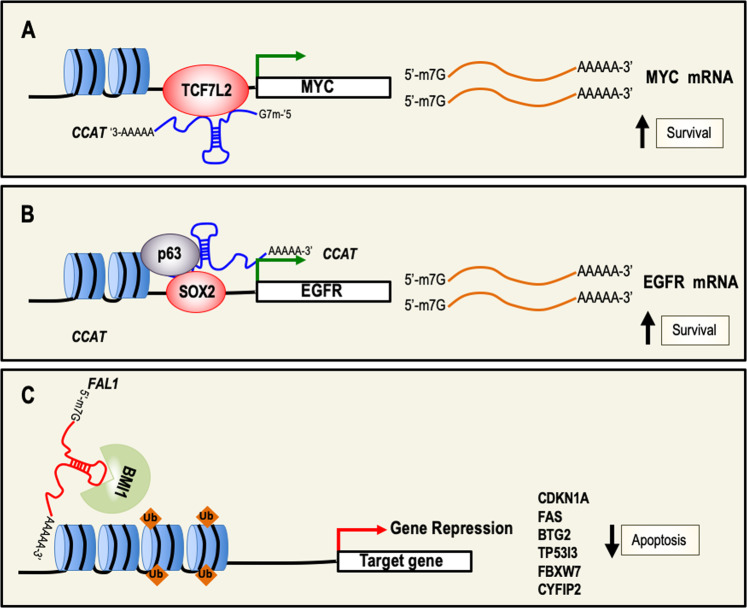

GAS5

The growth arrest-specific transcript 5 (GAS5) is located at 1q25, and the gene transcribed contains 12 exons that do not encode for functional proteins101. GAS5 is a tumor suppressor gene, and is one of the most expressed lncRNAs in all human tissues102. The expression of GAS5 in cancers is significantly reduced. Reduced expression has been observed in breast, prostate, head and neck, gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, and cervical cancer, and more importantly, its expression is negatively correlated with clinical–pathological characteristics, such as tumor size, staging, or metastasis. Moreover, in vivo studies have shown inhibition of breast tumor growth by inducing cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis after the overexpression of GAS5 in breast cancer cell lines and their subsequent injection in nude mice103. Several molecular mechanisms of action for GAS5 have been proposed, including inhibition of translation and decoy or miRNA sponge activity. The decoy function of GAS5 has been shown in HeLa and HepG2 cell lines, and seems to be its major mechanism of action. Indeed, GAS5 interacts with the DNA-responsive elements of glucocorticoids receptor preventing the binding of the receptor to the DNA, thereby blocking the activation of target genes transcription (Fig. 3a)104. Moreover, GAS5 can also interact with other steroid hormone receptors including progesterone and androgen receptors, which play important roles in hormone-dependent cancers102.

Fig. 3. lncRNAs as inducers of cell death and relative molecular mechanisms.

a GAS5 prevents GR-dependent gene activation by binding to the glucocorticoids receptor (GR) functioning as a decoy. b NF-κB is a key transcription factor in the regulation of cell survival. NKILA binds IkB and prevents its phosphorylation resulting in the inhibition of NF-κB activation, thereby repressing NF-κB target genes involved in cell survival. GAS5 growth arrest-specific transcript 5, GR glucocorticoids receptors, NF-κB nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, IkB inhibitor of kappa B.

MEG3

Maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3) located on the human chromosome region 14q32.3 is expressed in many normal tissues105. However, MEG3 expression is lost in several human tumors including osteosarcoma, hepatocellular cancer, gastric cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by promoter or intergenic differentially methylated region hypermethylation, suggesting that loss of MEG3 expression contributes to tumor development in several tissues106,107. Importantly, patients with lower levels of MEG3 expression had a relatively poor prognosis. MEG3 functions as a tumor suppressor gene, and its re-expression inhibits cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in human glioma and NSCLC cell lines. At a molecular level, MEG3 function is mediated, at least partially, by the activation of the tumor suppressor gene p53 by the downregulation of MDM2 expression108–110.

NKILA

The human gene that encodes NKILA, an NF-κB-interacting lncRNA, is located on chromosome 20. NKILA is downregulated in breast cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and melanoma111. In addition, reduced NKILA expression is associated with breast cancer metastasis and poor patient prognosis112. Mechanistically, the transcription factor NF-κB upregulates the expression of NKILA, which in turn binds to NF-κB/IκB, and directly masks the phosphorylation motifs of IκB, resulting in the inhibition of IKK-induced IκB phosphorylation, and NF-κB activation, forming a negative regulatory loop (Fig. 3b). This regulatory mechanism is promoting tumorigenesis by inhibiting apoptosis and increasing invasion. More recently, NKILA has also been shown to regulate T-cells activation by inhibiting NF-κB activity, and ectopic expression of NKILA in tumor-specific CTLs and TH1 cells correlated with apoptosis and shorter patient overall survival113.

NEAT1

The Homo sapiens nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1) sequence is a product of the NEAT1 gene, which is located on chromosome 11. NEAT1 has been identified as a p53 target gene that plays an important role in the formation of paraspeckles, and is indispensable for cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in response to genotoxic stress114. Therefore, it has a key function in suppressing neoplastic transformation and cancer onset. Indeed, in a pancreatic cancer mouse model, NEAT1 deficiency increased transformation and contributed to the development of premalignant pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and cystic lesions through global changes in gene expression115. Moreover, NEAT1 expression is downregulated in several cancers, while increased NEAT1 levels are correlated with better overall survival in colorectal cancer patients. In addition, elevated NEAT1 levels have been associated with enhanced apoptosis after DNA damage by irradiation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells116,117. However, NEAT1 role is controversial since several studies also characterized its oncogenic activity. As matter of fact, during tumorigenesis NEAT1 levels are increased, and high levels of NEAT1 were associated with worse prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma and laryngeal SCC118,119. Accordingly, modulation of NEAT1 expression promotes cell survival and/or proliferation of human cancer cell lines120, and NEAT1 acts as an oncogene in a mouse model of skin carcinogenesis114. At a molecular level, one possible mechanism by which NEAT1 exerts its oncogenic role, at least in ovarian cancer, is the interaction with the tumor suppressor miRNA miR-34a-5p, acting as a sponge and negatively regulating miR-34a expression.

Overall, NEAT1 can elicit a context-specific function in either promoting or suppressing neoplastic transformation.

lncRNAs with anti-apoptotic functions

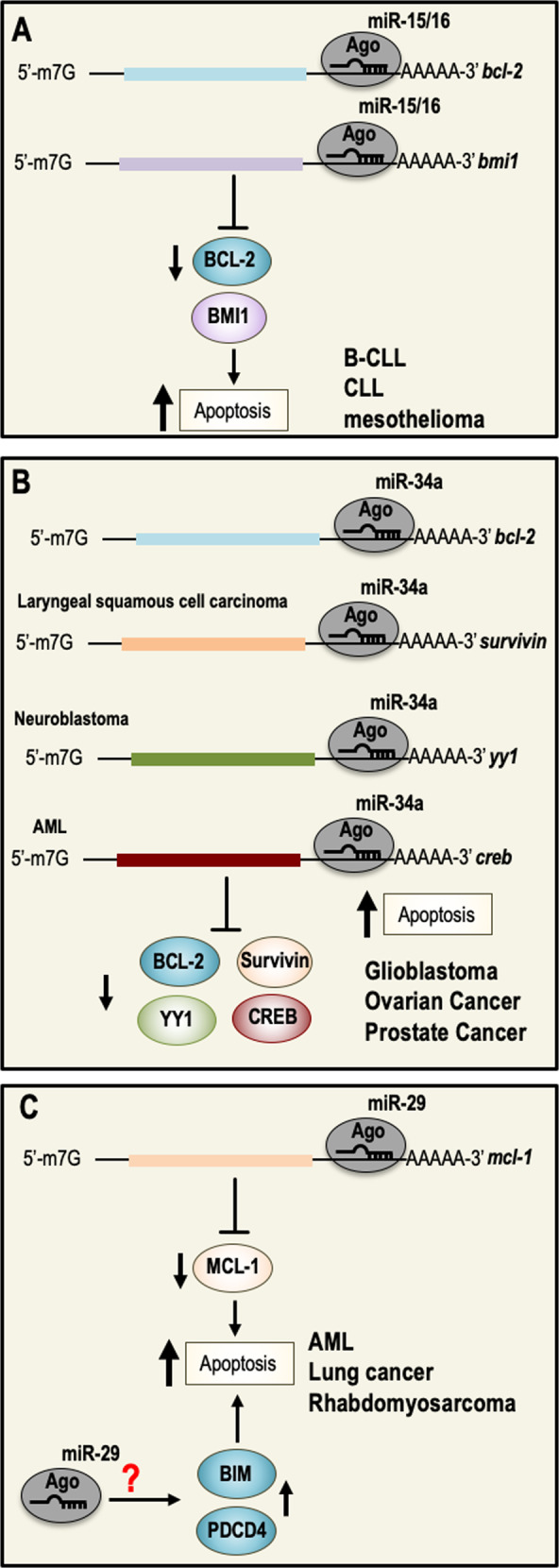

CCAT

Colon cancer-associated transcript (CCAT) is located within the 8q.24.21 genomic region that is frequently amplified in colorectal cancer (CRC)121,122. Expression profile studies highlight that CCAT1 and CCAT2 genes are frequently overexpressed in CRC, and their expression is associated with shorter progression-free and overall survival.

The oncogenic function of CCAT is the result of the activation of genes involved in cell proliferation and in the inhibition of apoptosis. Indeed, CCAT regulates the overexpression of MYC, possibly through its physical interaction with TCF7L2, leading to genomic instability and promoting cell growth (Fig. 4a). In addition, a second possible molecular regulatory mechanism has been observed in SCC; in this context, CCAT regulates transcription of genes involved in cell proliferation and survival by a physical interaction with both transcription factors p63 and SOX2123. (Fig. 4b). Finally, overexpression of CCAT has been observed in other types of cancer, including gastric, breast, and lung cancer124.

Fig. 4. lncRNAs with an anti-apoptotic activity and relative molecular mechanisms.

a CCAT is an oncogene that protects from cell death by up-regulating the expression of MYC. b p63, SOX2, and CCAT form a trimeric complex, which in turn binds the promoter region of EGFR and positively upregulates its expression. This results in sustaining cell survival. c FAL1 associates with the epigenetic repressor BMI1 and regulates its stability in order to modulate the transcription of a number of genes involved in cell death. CCAT colon cancer-associated transcript, MYC Myc proto-oncogene, SOX2 sex determining region box-2, EGFR epithelial growth factor receptor, FAL1 focally amplified LncRNA on chromosome 1, BMI1 polycomb complex protein BMI1.

FAL1

The gene encodes for focally amplified LncRNA on chromosome 1 (FAL1), and is localized at the chromosomal region 1q21.2. FAL1 functions as an oncogene in several cancers, and is upregulated in ovarian, thyroid cancer and NSCLC125,126. In addition, FAL1 expression correlates with some clinical and pathological characteristics of NSCLC and ovarian cancer patients. Both in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that the biological function of FAL1 is to regulate cell cycle, cell death, migration, and invasion127. Mechanistically, FAL1 interacts with the epigenetic repressor BMI1 and modulates the transcription of a number of genes involved in cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis, such as CDKN1A, FAS, BTG2, TP53I3, FBXW7, and CYFIP2128 (Fig. 4c).

PVT1

The human PVT1 gene is located in the human chromosome 8q24 region close to the well-established oncogene MYC129. Interestingly, the amplification of 8q24 is a frequent event in a vast variety of cancers including CRC, where it is also associated with clinical findings of decreased overall survival130,131. PVT1 functions as an oncogene by inhibiting the apoptosis of tumor cells, promoting cell proliferation, and affecting tumor invasion and metastasis generation. However, a detailed molecular mechanism underlying its anti-apoptotic activity is still missing. Recently, a possible mechanism by which PVT1 inhibits cell death has been described in nasopharyngeal carcinomas. In particular, PVT1 downregulates the expression of cleaved caspase-9, caspase-7, and PARP, inhibiting apoptosis and also promoting radiation resistance132,133.

Circular RNAs

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) were identified more than 20 years ago, and for many years have just been considered as secondary products of aberrant splicing processes134. Only recently, with the advent of next-generation sequencing, a large number of circRNAs has been identified, several of them showing high and stable expression. Nearly 10% of genes transcribed in cells can produce circRNAs.

CircRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II (Pol II), and they are generated by alternative splicing of pre-mRNA, in which the 5′ and the 3′ ends are joined together by a covalent bond, forming a single-strand continuous loop structure in a process known as “backsplicing”135. Moreover, several molecular mechanisms of action have been proposed to characterize their role in different biological and pathological processes. In particular, circRNAs are likely to function as miRNA sponges, to enhance the transcription of their parental genes or acting as decoys or scaffolds for proteins136,137.

The research on circRNAs is still in his infancy and their specific functions in several physiological processes and in the pathogenesis of human diseases is still largely unknown. However, recently high-throughput sequencing studies on clinical tumor samples showed a deregulation of circRNAs expression in tumors138,139. In particular, their downregulation has been described in proliferative cells across different tumor types, indicating that some circRNAs may have tumor suppressive roles. Global transcriptome analysis on 144 samples of localized prostate cancer, identifying 76,311 circRNAs, showed a correlation of circRNAs expression with tumor aggressivity, suggesting that 171 circRNAs are essential to prostate cancer cell proliferation140.

Overall, studies on clinical samples together with in vitro experiments showed that circRNAs play a role in several hallmarks of cancer having either tumor suppressive or oncogenic functions141–143. To our knowledge, no circRNAs from the literature have a clear and defined role in cancer biology proven by in vitro or in vivo experiments or by clinical data. However, we have decided to describe one of the more studied circRNAs that has a role in cell death regulation.

circFOXO3

circFOXO3 is a circular transcript of 1435 nucleotides derived from the tumor suppressor gene FOXO3144. Several expression profile studies indicated that circFOXO3 is downregulated in several tumors such as breast and NSCLC, suggesting a possible role as a tumor suppressor gene145,146. Both gain and loss of function experiments showed that circFOXO3 function is associated with the induction of apoptosis and with the inhibition of cell-cycle progression and angiogenesis. At a molecular level, ectopic expression of circFOXO3 decreases the interaction between FOXO3 and MDM2, releasing FOXO3 from MDM2-dependent degradation, therefore increasing FOXO3 activity, promoting PUMA expression, and enhancing cell death147.

Perspectives and conclusions

During the last decades, we have witnessed considerable developments in understanding the role of the regulatory ncRNAs in the regulation of physiological processes as well as in the pathogenesis of several diseases. Deregulation of ncRNAs expression has been largely documented during the initiation, progression, and dissemination of cancer, and preclinical studies have shown that they can be used as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. More importantly, it has been documented that ncRNAs can be released into the extracellular space and detected in body fluids (blood or urine) as circulating ncRNAs, potentially showing their application in liquid biopsies148. The clinical application of ncRNAs is already under evaluation in ongoing clinical trials trying to describe their role as biomarkers for patient survival, metastasis development prediction, or therapy response (Table 2).

Table 2.

Current clinical trials involving ncRNAs.

| ncRNA | Study title | Condition or disease | Interventions | Primary purpose | Clinical trails identifier | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-16 | MesomiR 1: A Phase I Study of TargomiRs as 2nd or 3rd Line Treatment for Patients with Recurrent MPM and NSCLC |

Mesothelioma Non-small cell lung cancer |

Drug: TargomiRs | Treatment | NCT02369198 | Completed |

| miR-34 | Critical Role of MicroRNA-34a and MicroRNA-194 in Acute Myeloid Leukemia With CEBPA Mutations | Leukemia | Genetic: RNA analysis | Not Reported | NCT01057199 | Completed |

| miR-29 | Phase 1: safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetic study of MRG-201 in healthy volunteers | Healthy volunteers | Drug: MRG-201 | Treatment | NCT02603224 | Completed |

| miR-155 | The Potential Role Of microRNA-155 And Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase In Diagnosis Of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer And Their Pathological Correlation | Bladder cancer | Diagnostic test | Diagnostic | NCT03591367 | Completed |

| miR-221 | Clinical Significance of Hepatic and Circulating microRNAs miR-221 and miR-222 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Analysis of microRNA expression | Not Reported | NCT02928627 | Unknown |

| miRNA/lncRNA | Noncoding RNA in the exosome of the epithelial ovarian cancer | Ovarian cancer | Sequencing miRNA/lncRNA | NCT03738319 | Recruiting | |

| miRNA | Circulating miRNAs as biomarkers of hormone sensitivity in breast cancer | Breast cancer | Drugs: tamoxifen, letrozole, anastrozole, exemestane | Treatment | NCT01612871 | Completed |

| miRNA | Circulating microRNA as disease markers in pediatric cancer | Leukemia lymphoma | Not reported | Observational | NCT01541800 | Recruiting |

Source: ClinicalTrials.gov.

As from above, regulatory ncRNAs play a key role in driving or preventing the process of tumorigenesis and preclinical studies indicate that modulation of their expression by mimetic or inhibitory oligonucleotides might be a novel therapeutic approach for cancer therapy. Indeed, a limited number of clinical trials using drugs based on ncRNAs, especially on microRNAs, are evaluating clinical safety, tolerability, and efficacy of this approach (Table 2). Although therapeutic applications are still at an early phase, a new chapter in the pharmacological treatment of human diseases has started. The recent approval of the RNA-targeting oligonucleotides drug Spinraza for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy by FDA149 makes reasonable to believe that more ncRNAs-based drugs will be soon available on the patient’s bedside.

Acknowledgements

We apologize for those whose contributions could not be cited due to space constraints. This work has been supported by the Medical Research Council (to G.M.), UK Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca contro il Cancro (AIRC) to G.M. IG #20473 (2018–2022), to E.C. (AIRC IG #22206; 2019–2023). This work has been also supported by Regione Lazio through LazioInnova Progetto Gruppo di Ricerca n 85–2017–14986 to G.M. and by Fondazione Luigi Maria Monti IDI-IRCCS (R.C. to E.C.), Ministry of Health & MAECI Italy-China Science and Technology Cooperation (#PGR00961).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by I. Amelio

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Massimiliano Agostini, Email: m.agostini@med.uniroma2.it.

Eleonora Candi, Email: candi@uniroma2.it.

Gerry Melino, Email: gm614@mrc-tox.cam.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Kastenhuber ER, Lowe SW. Putting p53 in context. Cell. 2017;170:1062–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubrey BJ, Kelly GL, Janic A, Herold MJ, Strasser A. How does p53 induce apoptosis and how does this relate to p53-mediated tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:104–113. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baugh EH, Ke H, Levine AJ, Bonneau RA, Chan CS. Why are there hotspot mutations in the TP53 gene in human cancers? Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:154–160. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser AM, Attardi LD. Deconstructing networks of p53-mediated tumor suppression in vivo. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:93–103. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim MP, Lozano G. Mutant p53 partners in crime. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:161–168. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parrales A, Thoenen E, Iwakuma T. The interplay between mutant p53 and the mevalonate pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:460–470. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0026-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nemajerova A, et al. Non-oncogenic roles of TAp73: from multiciliogenesis to metabolism. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:144–153. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabay, M., Li, Y. & Felsher, D. W. MYC activation is a hallmark of cancer initiation and maintenance. Cold Spring. Harb. Perspect. Med.4, 10.1101/cshperspect.a014241 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Tsujimoto Y, Finger LR, Yunis J, Nowell PC, Croce CM. Cloning of the chromosome breakpoint of neoplastic B cells with the t(14;18) chromosome translocation. Science. 1984;226:1097–1099. doi: 10.1126/science.6093263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams JM, Cory S. The BCL-2 arbiters of apoptosis and their growing role as cancer targets. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:27–36. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross A, Katz SG. Non-apoptotic functions of BCL-2 family proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1348–1358. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strasser A, Vaux DL. Viewing BCL2 and cell death control from an evolutionary perspective. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:13–20. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charni M, Aloni-Grinstein R, Molchadsky A, Rotter V. p53 on the crossroad between regeneration and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:8–14. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engeland K. Cell cycle arrest through indirect transcriptional repression by p53: I have a DREAM. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:114–132. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furth N, Aylon Y, Oren M. p53 shades of Hippo. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:81–92. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furth N, Aylon Y. The LATS1 and LATS2 tumor suppressors: beyond the Hippo pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1488–1501. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huttenhofer A, Schattner P, Polacek N. Non-coding RNAs: hope or hype? Trends Genet. 2005;21:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen LL. The biogenesis and emerging roles of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:205–211. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galluzzi L, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:486–541. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flynn RA, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs in cell-fate programming and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:752–761. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran VA, Perera RJ, Khalil AM. Emerging functional and mechanistic paradigms of mammalian long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6391–6400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aberdam D, Candi E, Knight RA, Melino G. miRNAs, ‘stemness’ and skin. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008;33:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancini M, et al. MicroRNAs in human skin ageing. Ageing Res. Rev. 2014;17:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi R, Poy MN, Stoffel M, Fuchs E. A skin microRNA promotes differentiation by repressing ‘stemness’. Nature. 2008;452:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature06642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amelio I, et al. miR-24 triggers epidermal differentiation by controlling actin adhesion and cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 2012;199:347–363. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viticchie G, et al. MicroRNA-203 contributes to skin re-epithelialization. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e435. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tucci P, et al. Loss of p63 and its microRNA-205 target results in enhanced cell migration and metastasis in prostate cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:15312–15317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110977109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregory PA, et al. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:593–601. doi: 10.1038/ncb1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lena AM, et al. miR-203 represses ‘stemness’ by repressing DeltaNp63. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1187–1195. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bommer GT, et al. p53-mediated activation of miRNA34 candidate tumor-suppressor genes. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurteau GJ, Carlson JA, Spivack SD, Brock GJ. Overexpression of the microRNA hsa-miR-200c leads to reduced expression of transcription factor 8 and increased expression of E-cadherin. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7972–7976. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Pedro I, Alonso-Lecue P, Sanz-Gomez N, Freije A, Gandarillas A. Sublethal UV irradiation induces squamous differentiation via a p53-independent, DNA damage-mitosis checkpoint. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1094. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1130-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messenger ZJ, et al. C/EBPbeta deletion in oncogenic Ras skin tumors is a synthetic lethal event. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1054. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1103-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh TP, Vieyra-Garcia PA, Wagner K, Penninger J, Wolf P. Cbl-b deficiency provides protection against UVB-induced skin damage by modulating inflammatory gene signature. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:835. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0858-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bigas J, Sevilla LM, Carceller E, Boix J, Perez P. Epidermal glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors act cooperatively to regulate epidermal development and counteract skin inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:588. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0673-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue Z, et al. lincRNA-Cox2 regulates NLRP3 inflammasome and autophagy mediated neuroinflammation. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:130–145. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0105-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kretz M, et al. Suppression of progenitor differentiation requires the long noncoding RNA ANCR. Genes Dev. 2012;26:338–343. doi: 10.1101/gad.182121.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kretz M, et al. Control of somatic tissue differentiation by the long non-coding RNA TINCR. Nature. 2013;493:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature11661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziegler, C. et al. The long non-coding RNA LINC00941 and SPRR5 are novel regulators of human epidermal homeostasis. EMBO Rep. 20, 10.15252/embr.201846612 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Panatta E, et al. Long non-coding RNA uc.291 controls epithelial differentiation by interfering with the ACTL6A/BAF complex. EMBO Rep. 2020;21:e46734. doi: 10.15252/embr.201846734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roush S, Slack FJ. The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang L, Yang Z, Huang W, Wu J. H19 potentiates let-7 family expression through reducing PTBP1 binding to their precursors in cholestasis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:168. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1423-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takamizawa J, et al. Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3753–3756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shell S, et al. Let-7 expression defines two differentiation stages of cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11400–11405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704372104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Childs G, et al. Low-level expression of microRNAs let-7d and miR-205 are prognostic markers of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;174:736–745. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mizuno R, Kawada K, Sakai Y. The molecular basis and therapeutic potential of Let-7 microRNAs against colorectal cancer. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;2018:5769591. doi: 10.1155/2018/5769591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang Y, Hong X, Hu J, Lu Q. Targeted regulation of MiR-98 on E2F1 increases chemosensitivity of leukemia cells K562/A02. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:3233–3239. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S126819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trang P, et al. Regression of murine lung tumors by the let-7 microRNA. Oncogene. 2010;29:1580–1587. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pekarsky Y, Balatti V, Croce CM. BCL2 and miR-15/16: from gene discovery to treatment. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:21–26. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calin GA, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allegra D, et al. Defective DROSHA processing contributes to downregulation of MiR-15/-16 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;28:98–107. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cimmino A, et al. miR-15 and miR-16 induce apoptosis by targeting BCL2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13944–13949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506654102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teshima K, et al. Dysregulation of BMI1 and microRNA-16 collaborate to enhance an anti-apoptotic potential in the side population of refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Oncogene. 2014;33:2191–2203. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kalkavan H, Green DR. MOMP, cell suicide as a BCL-2 family business. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:46–55. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Montero J, Letai A. Why do BCL-2 inhibitors work and where should we use them in the clinic? Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:56–64. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pihan P, Carreras-Sureda A, Hetz C. BCL-2 family: integrating stress responses at the ER to control cell demise. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1478–1487. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Opferman JT, Kothari A. Anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family members in development. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:37–45. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reid G, et al. Restoring expression of miR-16: a novel approach to therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann. Oncol. 2013;24:3128–3135. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen SS, et al. Resistin facilitates VEGF-A-dependent angiogenesis by inhibiting miR-16-5p in human chondrosarcoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:31. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1241-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klein U, et al. The DLEU2/miR-15a/16-1 cluster controls B cell proliferation and its deletion leads to chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raveche ES, et al. Abnormal microRNA-16 locus with synteny to human 13q14 linked to CLL in NZB mice. Blood. 2007;109:5079–5086. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-071225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henrich KO, Schwab M, Westermann F. 1p36 tumor suppression-a matter of dosage? Cancer Res. 2012;72:6079–6088. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Agostini M, Knight R. A. miR-34: from bench to bedside. Oncotarget. 2014;5:872–881. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li F, et al. MALAT1 regulates miR-34a expression in melanoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:389. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1620-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Laake K, et al. Loss of heterozygosity at 11q23.1 in breast carcinomas: indication for involvement of a gene distal and close to ATM. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1997;18:175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hart M, et al. miR-34a: a new player in the regulation of T cell function by modulation of NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:46. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1295-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chang TC, et al. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pigazzi M, Manara E, Baron E, Basso G. miR-34b targets cyclic AMP-responsive element binding protein in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2471–2478. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen QR, et al. Systematic proteome analysis identifies transcription factor YY1 as a direct target of miR-34a. J. Proteome Res. 2011;10:479–487. doi: 10.1021/pr1006697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shen Z, et al. MicroRNA-34a affects the occurrence of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma by targeting the antiapoptotic gene survivin. Med Oncol. 2012;29:2473–2480. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kale J, Osterlund EJ, Andrews DW. BCL-2 family proteins: changing partners in the dance towards death. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:65–80. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Beg MS, et al. Phase I study of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, administered twice weekly in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest. N. Drugs. 2017;35:180–188. doi: 10.1007/s10637-016-0407-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Le Beau MM, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular delineation of a region of chromosome 7 commonly deleted in malignant myeloid diseases. Blood. 1996;88:1930–1935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kwon JJ, Factora TD, Dey S, Kota J. A systematic review of miR-29 in cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2019;12:173–194. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mott JL, Kobayashi S, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. mir-29 regulates Mcl-1 protein expression and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2007;26:6133–6140. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garzon R, et al. MicroRNA 29b functions in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:5331–5341. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu H, et al. miR-29c-3p regulates DNMT3B and LATS1 methylation to inhibit tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:48. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1281-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ngankeu A, et al. Discovery and functional implications of a miR-29b-1/miR-29a cluster polymorphism in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2018;9:4354–4365. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Calin GA, et al. Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2999–3004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307323101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iorio MV, et al. MicroRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7065–7070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seike M, et al. MiR-21 is an EGFR-regulated anti-apoptotic factor in lung cancer in never-smokers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12085–12090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Volinia S, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xue Z, et al. miR-21 promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation to mediate pyroptosis and endotoxic shock. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:461. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1713-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hatley ME, et al. Modulation of K-Ras-dependent lung tumorigenesis by MicroRNA-21. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:282–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Medina PP, Nolde M, Slack FJ. OncomiR addiction in an in vivo model of microRNA-21-induced pre-B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010;467:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature09284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rodriguez A, et al. Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science. 2007;316:608–611. doi: 10.1126/science.1139253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baltimore D, Boldin MP, O’Connell RM, Rao DS, Taganov KD. MicroRNAs: new regulators of immune cell development and function. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:839–845. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eis PS, et al. Accumulation of miR-155 and BIC RNA in human B cell lymphomas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3627–3632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500613102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kluiver J, et al. BIC and miR-155 are highly expressed in Hodgkin, primary mediastinal and diffuse large B cell lymphomas. J. Pathol. 2005;207:243–249. doi: 10.1002/path.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kluiver J, et al. Lack of BIC and microRNA miR-155 expression in primary cases of Burkitt lymphoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:147–153. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Costinean S, et al. Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol-5-phosphatase and CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta are targeted by miR-155 in B cells of Emicro-MiR-155 transgenic mice. Blood. 2009;114:1374–1382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.O’Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Baltimore D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:7113–7118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902636106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wan J, et al. Inhibition of miR-155 reduces impaired autophagy and improves prognosis in an experimental pancreatitis mouse model. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:303. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1545-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cheng CJ, et al. MicroRNA silencing for cancer therapy targeted to the tumour microenvironment. Nature. 2015;518:107–110. doi: 10.1038/nature13905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee EJ, et al. Expression profiling identifies microRNA signature in pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;120:1046–1054. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Braconi C, Patel T. MicroRNA expression profiling: a molecular tool for defining the phenotype of hepatocellular tumors. Hepatology. 2008;47:1807–1809. doi: 10.1002/hep.22326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pineau P, et al. miR-221 overexpression contributes to liver tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:264–269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907904107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Park JK, et al. miR-221 silencing blocks hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes survival. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7608–7616. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu X, et al. MicroRNA-222 regulates cell invasion by targeting matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1) and manganese superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) in tongue squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Genomics Proteom. 2009;6:131–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wilusz JE, Sunwoo H, Spector DL. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1494–1504. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pickard MR, Williams GT. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of action of tumour suppressor GAS5 LncRNA. Genes. 2015;6:484–499. doi: 10.3390/genes6030484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hudson WH, et al. Conserved sequence-specific lincRNA-steroid receptor interactions drive transcriptional repression and direct cell fate. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5395. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Pickard MR, Hedge VL, Farzaneh F, Williams GT. GAS5, a non-protein-coding RNA, controls apoptosis and is downregulated in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:195–208. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kino T, Hurt DE, Ichijo T, Nader N, Chrousos GP. Noncoding RNA gas5 is a growth arrest- and starvation-associated repressor of the glucocorticoid receptor. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:ra8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhou Y, Zhang X, Klibanski A. MEG3 noncoding RNA: a tumor suppressor. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012;48:R45–R53. doi: 10.1530/JME-12-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lu KH, et al. Long non-coding RNA MEG3 inhibits NSCLC cells proliferation and induces apoptosis by affecting p53 expression. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:461. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gailhouste L, et al. MEG3-derived miR-493-5p overcomes the oncogenic feature of IGF2-miR-483 loss of imprinting in hepatic cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:553. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1788-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhou Y, et al. Activation of p53 by MEG3 non-coding RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:24731–24742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wu D, Prives C. Relevance of the p53-MDM2 axis to aging. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:169–179. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sullivan KD, Galbraith MD, Andrysik Z, Espinosa JM. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by p53. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:133–143. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lu Z, et al. Long non-coding RNA NKILA inhibits migration and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer via NF-kappaB/Snail pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;36:54. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0518-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu B, et al. A cytoplasmic NF-kappaB interacting long noncoding RNA blocks IkappaB phosphorylation and suppresses breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:370–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Huang D, et al. NKILA lncRNA promotes tumor immune evasion by sensitizing T cells to activation-induced cell death. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:1112–1125. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0207-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Adriaens C, et al. p53 induces formation of NEAT1 lncRNA-containing paraspeckles that modulate replication stress response and chemosensitivity. Nat. Med. 2016;22:861–868. doi: 10.1038/nm.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mello SS, et al. Neat1 is a p53-inducible lincRNA essential for transformation suppression. Genes Dev. 2017;31:1095–1108. doi: 10.1101/gad.284661.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Blume CJ, et al. p53-dependent non-coding RNA networks in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29:2015–2023. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wu Y, et al. Nuclear-enriched abundant transcript 1 as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2015;14:191. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0455-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ma Y, et al. Enhanced expression of long non-coding RNA NEAT1 is associated with the progression of gastric adenocarcinomas. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2016;14:41. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0799-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang P, et al. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1 promotes laryngeal squamous cell cancer through regulating miR-107/CDK6 pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;35:22. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0297-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shin VY, et al. Long non-coding RNA NEAT1 confers oncogenic role in triple-negative breast cancer through modulating chemoresistance and cancer stemness. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:270. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1513-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ozawa T, et al. CCAT1 and CCAT2 long noncoding RNAs, located within the 8q.24.21 ‘gene desert’, serve as important prognostic biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28:1882–1888. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Alaiyan B, et al. Differential expression of colon cancer associated transcript1 (CCAT1) along the colonic adenoma-carcinoma sequence. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jiang Y, et al. Co-activation of super-enhancer-driven CCAT1 by TP63 and SOX2 promotes squamous cancer progression. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3619. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06081-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.McCleland ML, et al. CCAT1 is an enhancer-templated RNA that predicts BET sensitivity in colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:639–652. doi: 10.1172/JCI83265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhong X, Hu X, Zhang L. Oncogenic long noncoding RNA FAL1 in human cancer. Mol. Cell Oncol. 2015;2:e977154. doi: 10.4161/23723556.2014.977154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jeong S, et al. Relationship of focally amplified long noncoding on chromosome 1 (FAL1) lncRNA with E2F transcription factors in thyroid cancer. Medicine. 2016;95:e2592. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pan C, et al. Long noncoding RNA FAL1 promotes cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition through the PTEN/AKT signaling axis in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017;43:339–352. doi: 10.1159/000480414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hu X, et al. A functional genomic approach identifies FAL1 as an oncogenic long noncoding RNA that associates with BMI1 and represses p21 expression in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:344–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tseng YY, et al. PVT1 dependence in cancer with MYC copy-number increase. Nature. 2014;512:82–86. doi: 10.1038/nature13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Popescu NC, Zimonjic DB. Chromosome-mediated alterations of the MYC gene in human cancer. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2002;6:151–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Guan Y, et al. Amplification of PVT1 contributes to the pathophysiology of ovarian and breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:5745–5755. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.He Y, et al. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 predicts poor prognosis and induces radioresistance by regulating DNA repair and cell apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:235. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0265-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mukherjee A, Williams DW. More alive than dead: non-apoptotic roles for caspases in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1411–1421. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Cocquerelle C, Mascrez B, Hetuin D, Bailleul B. Mis-splicing yields circular RNA molecules. FASEB J. 1993;7:155–160. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.7678559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Barrett SP, Wang PL, Salzman J. Circular RNA biogenesis can proceed through an exon-containing lariat precursor. eLife. 2015;4:e07540. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hansen TB, et al. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Memczak S, et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Vo JN, et al. The landscape of circular RNA in cancer. Cell. 2019;176:869–881 e813. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Xiong DD, et al. High throughput circRNA sequencing analysis reveals novel insights into the mechanism of nitidine chloride against hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:658. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1890-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Chen S, et al. Widespread and functional RNA circularization in localized prostate cancer. Cell. 2019;176:831–843 e822. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kristensen LS, Hansen TB, Veno MT, Kjems J. Circular RNAs in cancer: opportunities and challenges in the field. Oncogene. 2018;37:555–565. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Liu Z, et al. CircRNA-5692 inhibits the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma by sponging miR-328-5p to enhance DAB2IP expression. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:900. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gao L, et al. CircCDR1as upregulates autophagy under hypoxia to promote tumor cell survival via AKT/ERK(1/2)/mTOR signaling pathways in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:745. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1971-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Yang W, Du WW, Li X, Yee AJ, Yang BB. Foxo3 activity promoted by non-coding effects of circular RNA and Foxo3 pseudogene in the inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2016;35:3919–3931. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zhang Y, Zhao H, Zhang L. Identification of the tumorsuppressive function of circular RNA FOXO3 in nonsmall cell lung cancer through sponging miR155. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018;17:7692–7700. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Lu WY. Roles of the circular RNA circ-Foxo3 in breast cancer progression. Cell Cycle. 2017;16:589–590. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1278935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Du WW, et al. Induction of tumor apoptosis through a circular RNA enhancing Foxo3 activity. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:357–370. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Anfossi S, Babayan A, Pantel K, Calin GA. Clinical utility of circulating non-coding RNAs - an update. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:541–563. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Stein CA, Castanotto D. FDA-approved oligonucleotide therapies in 2017. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1069–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]